User login

Managing TIA: Early action and essential risk-reduction steps

As many as 240,000 people per year in the United States experience a transient ischemic attack (TIA),1,2 which is now defined by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association as a “transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia, without acute infarction.”3 An older definition of TIA was based on the duration of the event (ie, resolution of symptoms at 24 hours); in the updated (2009) definition, the diagnostic criterion is the extent of focal tissue damage.3 Using the 2009 definition might mean a decrease in the number of patients who have a diagnosis of a TIA and an increase in the number who are determined to have had a stroke because an infarction is found on initial imaging.

Guided by the 2009 revised definition of a TIA, we review here the work-up and treatment of TIA, emphasizing immediacy of management to (1) prevent further tissue damage and (2) decrease the risk of a second event.

CASE

Martin L, 69 years old, retired, a nonsmoker, and with a history of peripheral arterial disease and hypercholesterolemia, presents to the emergency department (ED) of a rural hospital complaining of slurred speech and left-side facial numbness. He had an episode of facial numbness that lasted 30 minutes, then resolved, each of the 2 previous evenings; he did not seek care at those times. Now, in the ED, Mr. L is normotensive.

The patient’s medication history includes a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and melatonin to improve sleep. He reports having discontinued a statin because he could not tolerate its adverse effects.

What immediate steps are recommended for Mr. L’s care?

Common event callsfor quick action

A TIA is the strongest predictor of subsequent stroke and stroke-related death; the highest period of risk of these devastating outcomes is immediately following a TIA.1,2,4,5 It is essential, therefore, for the physician who sees a patient with a current complaint or recent history of suspected focal neurologic deficits to direct that patient to an ED for an accurate diagnosis and, as appropriate, early treatment for the best possible outcome.

Imaging—preferably, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI), the gold standard for diagnosing stroke (see “Diagnosis includes ruling out mimics”)2,3—should be performed as soon as the patient with a suspected TIA arrives in the ED. Imaging should not be held while waiting for a stroke to declare itself—ie, by allowing symptoms to persist for longer than 24 hours. 6

Continue to: Late presentation

Late presentation. Some patients present ≥ 48 hours after onset of early symptoms of a TIA; for them, the work-up is the same as for prompt presentation but can be completed in the outpatient clinic—as long as the patient is stable clinically and imaging is accessible there. DW-MRI should be completed within 48 hours after late presentation. In such cases, the patient should be cautioned regarding risks and any recurrence of symptoms.7,8

Diagnosis includes ruling out mimics

All patients in whom a stroke is suspected should be evaluated on an emergency basis with brain imaging upon arrival at the hospital, before any therapy is initiated. As noted, DW-MRI is the preferred modality; noncontrast computed tomography (CT) or CT angiography can be used if MRI is unavailable.2,3

Mimics. Stroke has many mimics; quickly eliminating them from the differential diagnosis is important so that appropriate therapy can be initiated. Mimics usually have a prolonged presentation of symptoms, whereas the presentation of a TIA is usually abrupt. The 3 more common diagnoses that mimic a TIA are migraine with aura, seizure, and syncope.9,10 Symptoms that generally are not associated with a TIA are chest pain, generalized weakness, and confusion.11 A complete history and physical exam provide the path to the imaging, laboratory, and cardiac testing that is needed to differentiate these diagnoses from a TIA.

A thorough history is best obtained from the patient and a witness, if available, and should include identification of any focal neurologic deficits and the duration and time to resolution of symptoms. Obtain a history of risk factors for ischemia—tobacco use, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, previous TIA or stroke, atrial fibrillation, and any coagulopathy. Ask questions about a family history of TIA, stroke, and coagulopathy.11

A comprehensive physical exam, including vital signs, cardiac exam, a check for carotid bruits, and complete neurologic exam, should be performed. Most patients present with concerns for unilateral weakness and changes in speech, which are usually associated with infarction on DW-MRI.12 The most common findings on physical exam include cranial nerve abnormalities, such as diplopia, hemianopia, monocular blindness, disconjugate gaze, facial drooping, lateral tongue movement, dysphagia, and vestibular dysfunction. Cerebellar abnormalities are also often noted, including past pointing, dystaxia, ataxia, nystagmus, and motor abnormalities (eg, spasticity, clonus, or unilateral weakness in the face or extremities).11

Electrocardiography at the bedside can confirm atrial fibrillation or another arrhythmia quickly.

Essential laboratory testing includes measurement of blood glucose and serum electrolytes to determine if these particular imbalances are the cause of symptoms. The presence of a hypercoaguable state is determined by a complete blood count and coagulation studies.3,13 Urine toxicology should also be obtained to rule out other causes of symptoms. A lipid profile is beneficial for making long-term treatment decisions.

Continue to: ABCD2 score

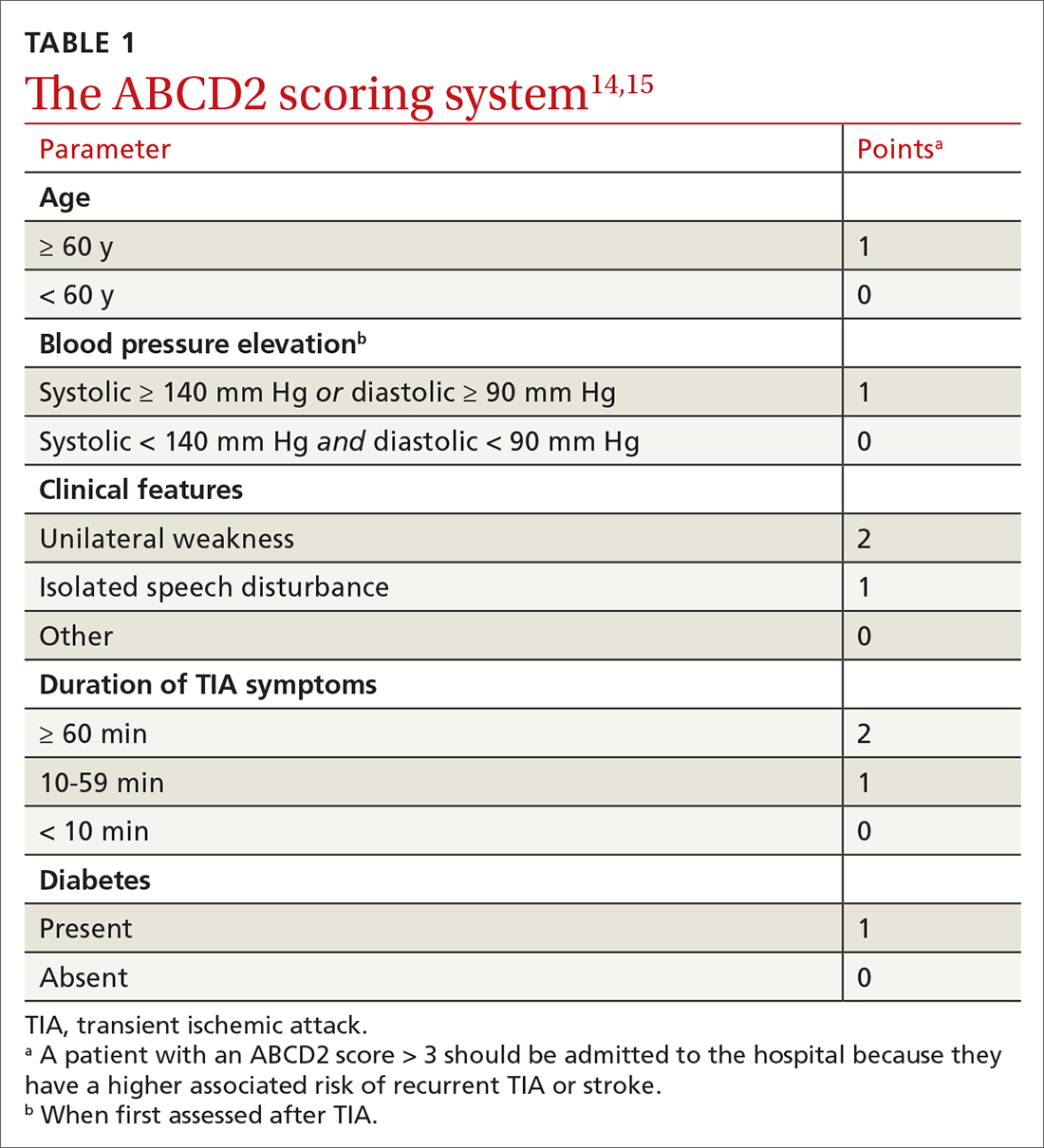

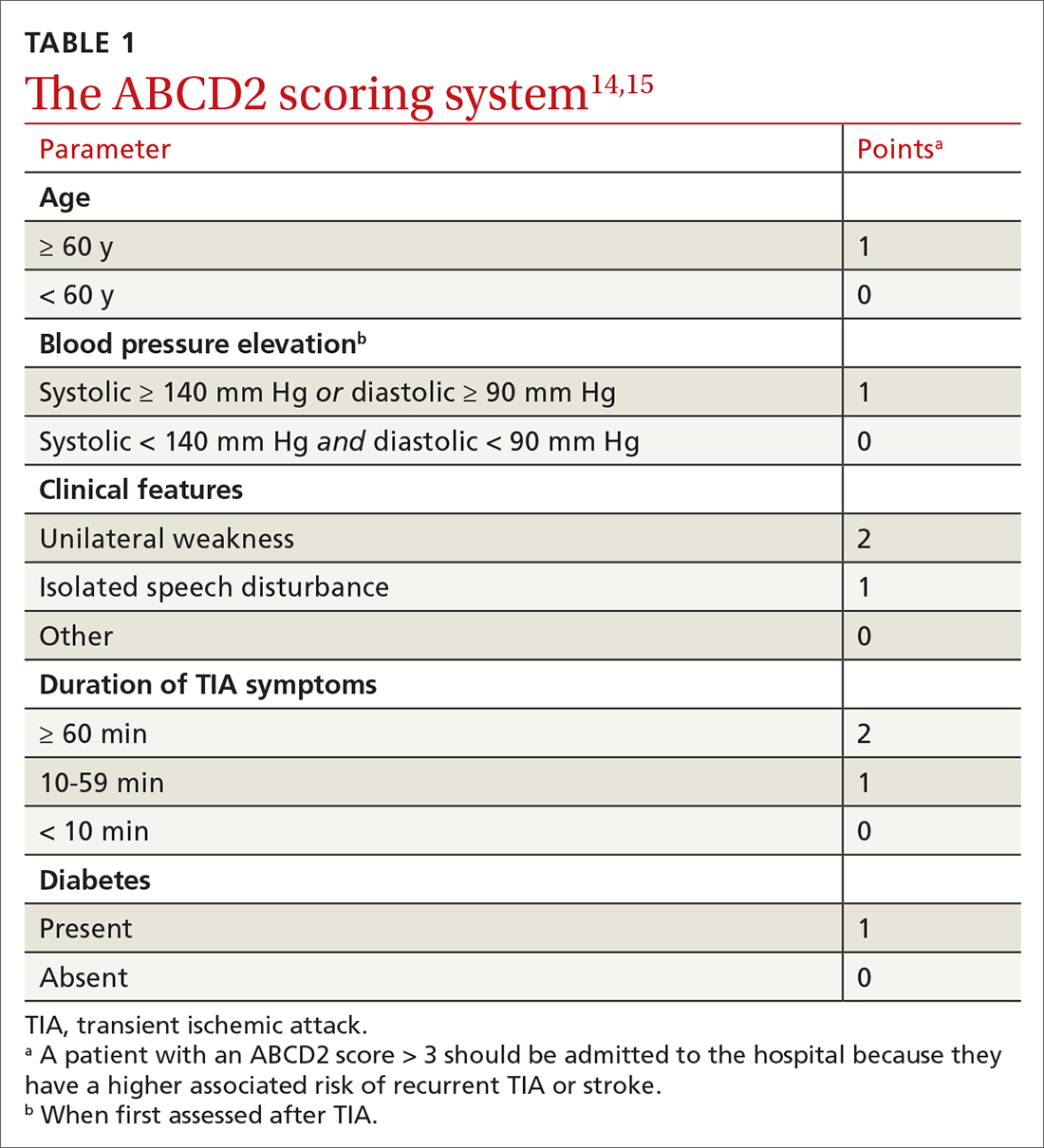

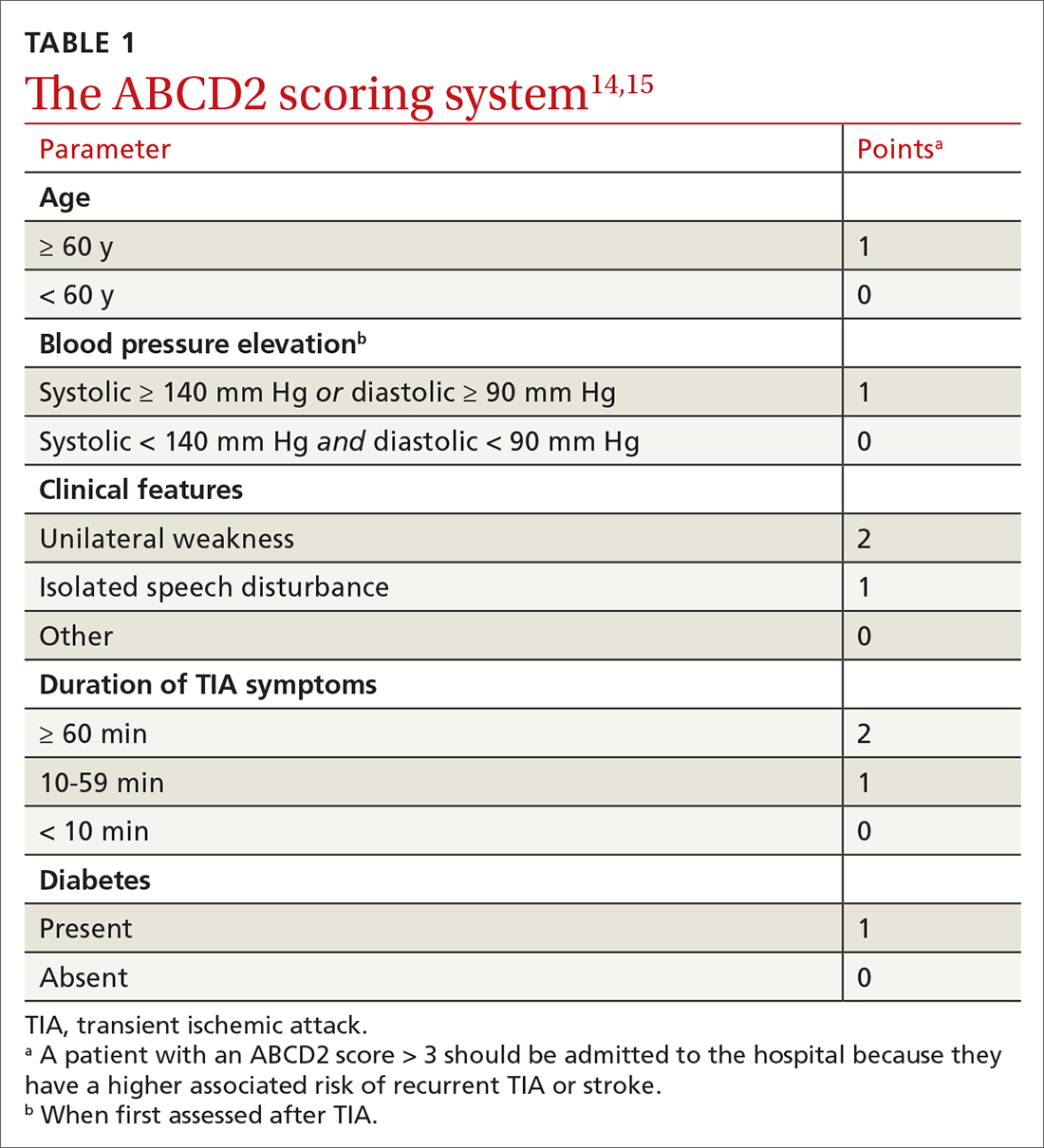

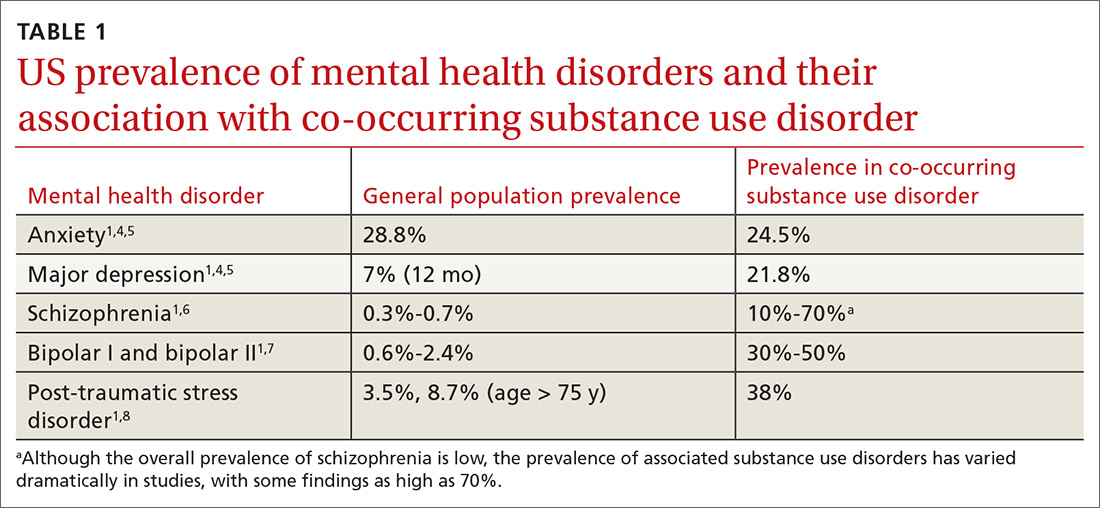

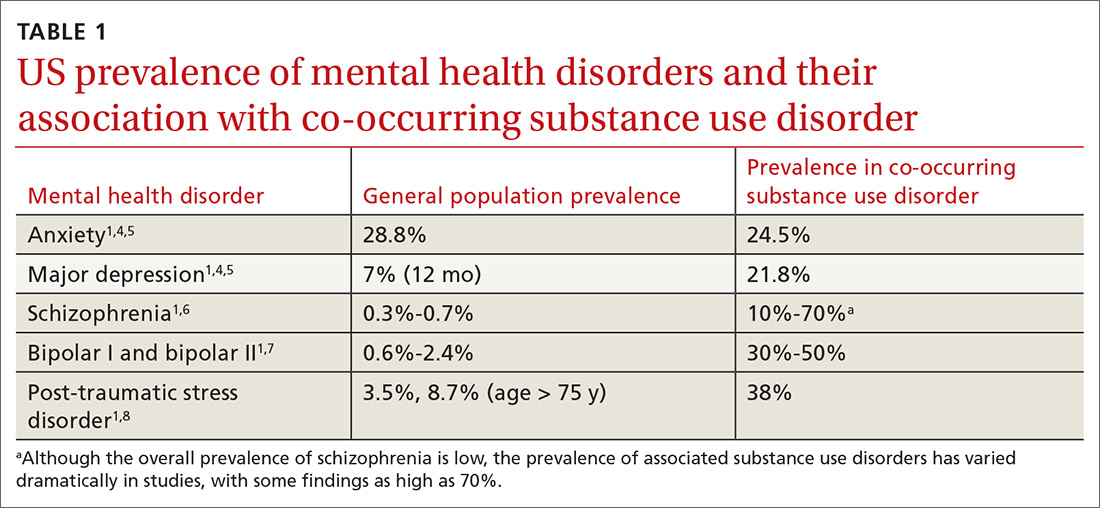

ABCD2 score. Patients who have had a TIA and present within 72 hours after symptoms have resolved should be hospitalized if they have an ABCD2 (Age, Blood pressure [BP], Clinical presentation, Diabetes mellitus [type 1 or 2], Duration of symptoms) prediction system score > 3.14 ABCD2 criteria can be used to help identify patients who are at higher risk of stroke or need further therapy (TABLE 1).14,15

The ABCD2 score is also used to determine whether a patient needs dual antiplatelet therapy. Patients who score at the higher end of the ABCD2 system usually have an increased risk of stroke, longer hospitalization, and greater disability.

CASE

In the ED, Mr. L is immediately assessed and airlifted to a larger regional medical center, where MRI confirms a stroke.

Management

Initial management of a TIA is aimed at reducing the risk of recurrent TIA or stroke. Early medical and possibly surgical treatment are key for preventing stroke and improving outcomes. The first 48 hours after a TIA are the most critical because the incidence of recurrent TIA or stroke is highest during this period.16-18

What is the accepted strategy for early treatment?

Initial treatment must include antiplatelet therapy, BP management, anticoagulation, statin therapy, and carotid endarterectomy as indicated.2,19,20 Control of hypertension and anticoagulation decrease the risk of recurrent stroke by the largest margin20; both are “A”-level Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy interventions.2,3

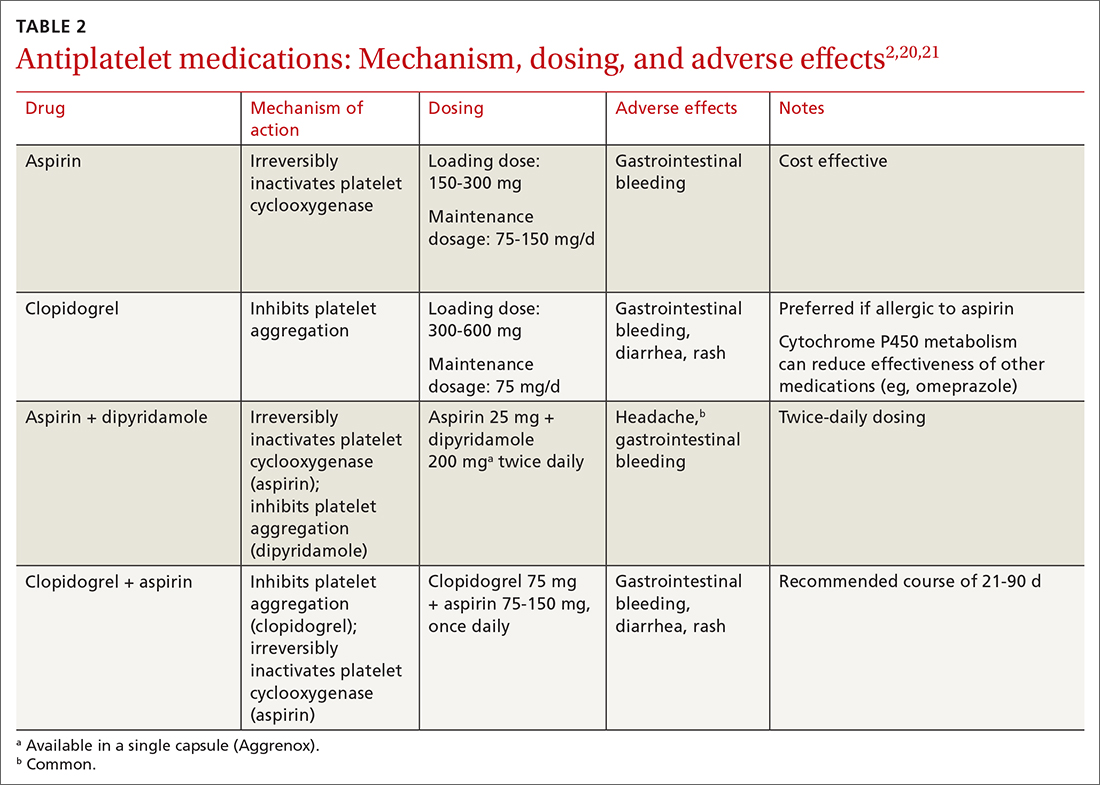

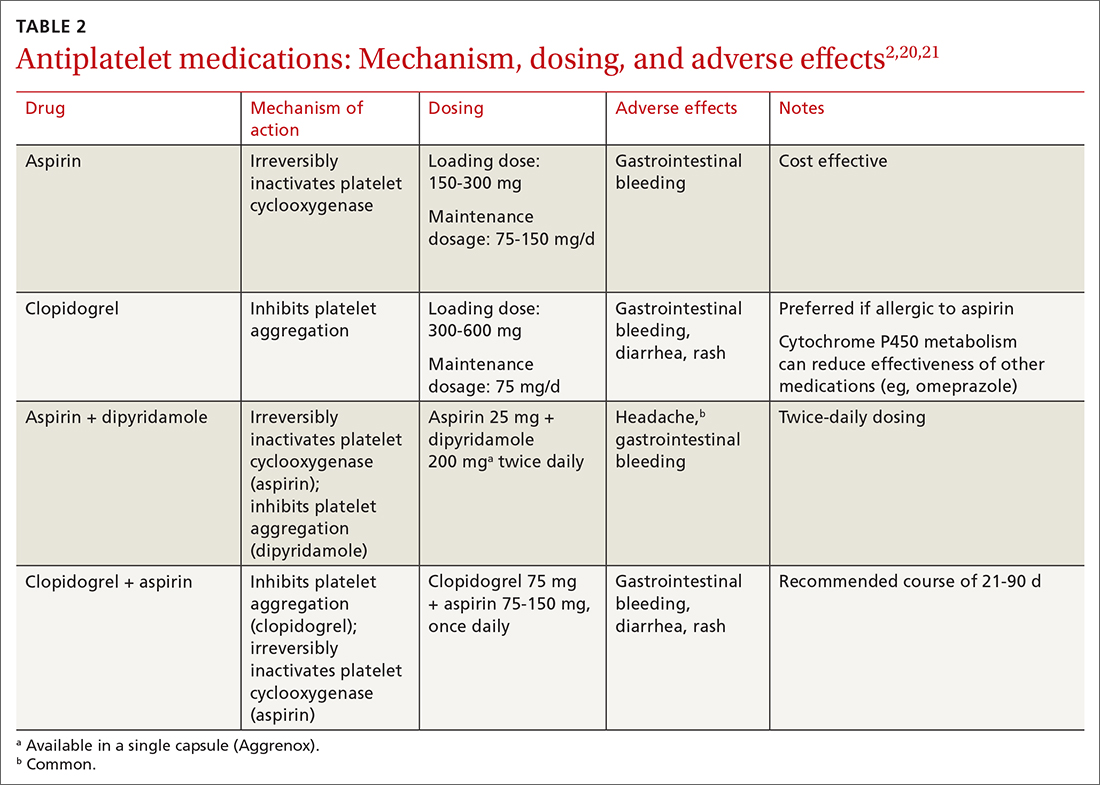

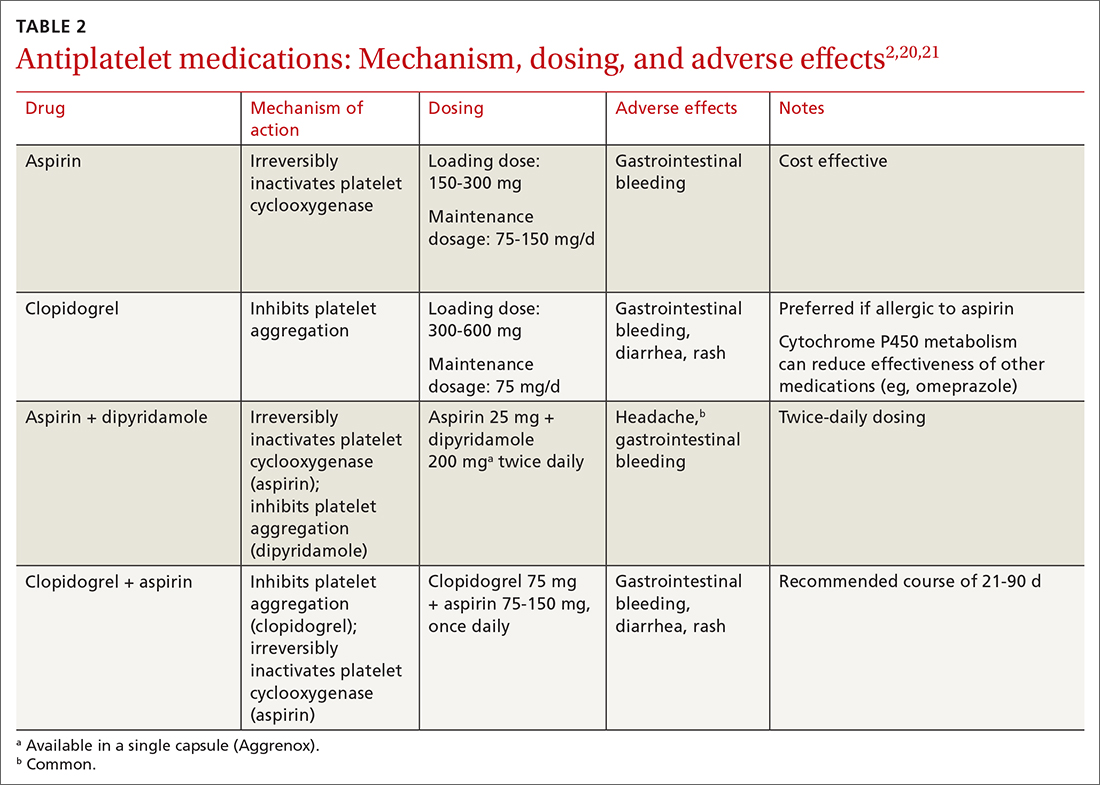

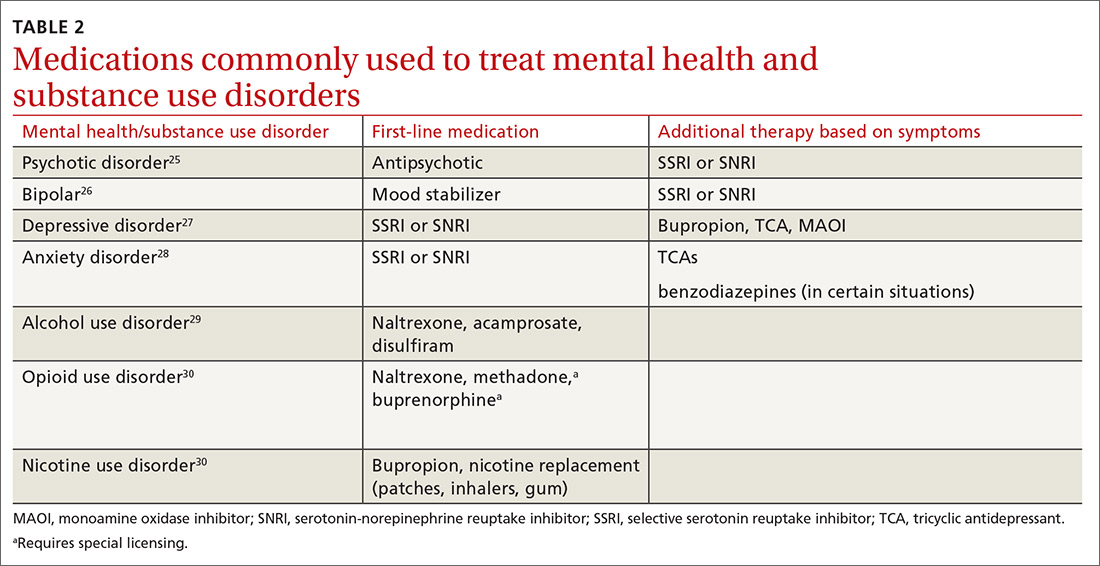

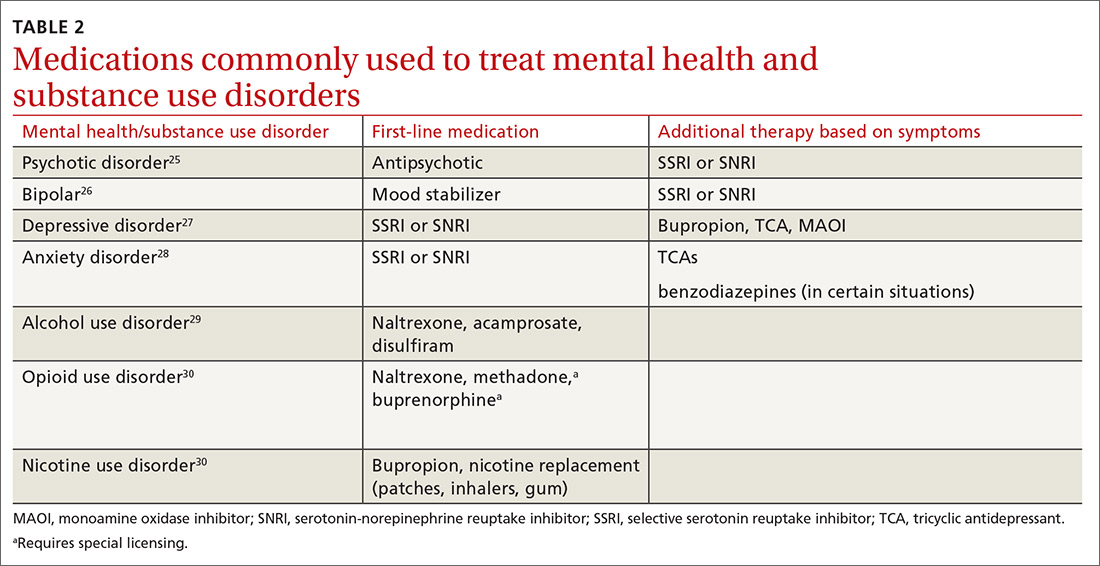

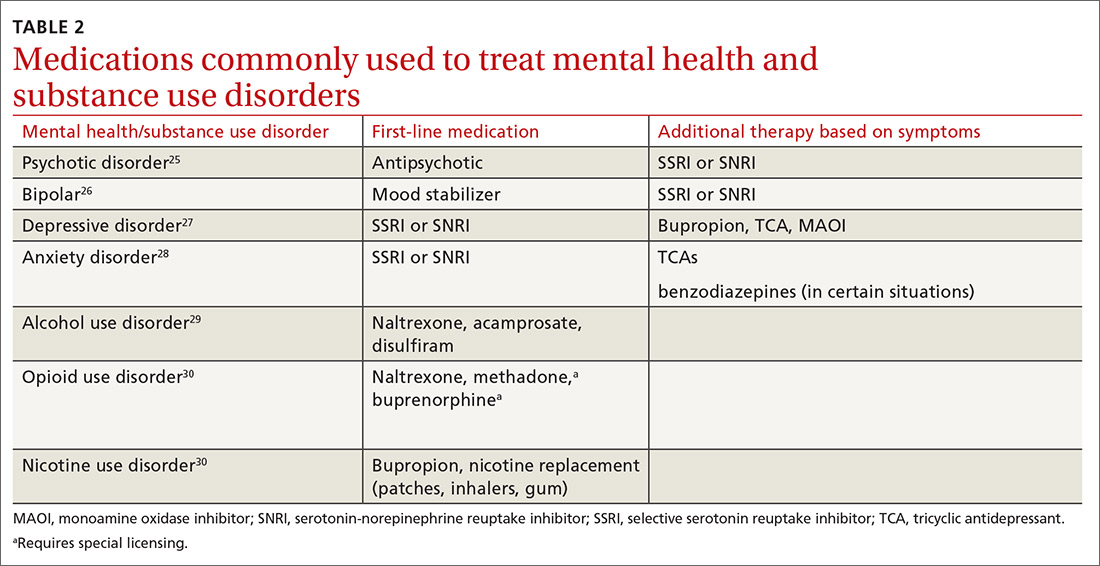

Step 1: Antiplatelet therapy. After initial imaging is complete and if there are no contraindications, antiplatelet agents are recommended for patients who have had a noncardioembolic TIA. The American Heart Association and American Stroke Association recommend either aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole + aspirin (available in a single capsule [Aggrenox]), or clopidogrel + aspirin as first-line therapy.2,20 The choice of agent needs to be individualized, based on tolerability and adverse effects (TABLE 22,20,21).

A meta-analysis of antiplatelet therapy reviewed the optimum dosing of each medication.21,22 Reduction of the risk of ischemic stroke with aspirin is 21% to 22% at the optimal dosing of 75 to 150 mg/d, which also reduces the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Continue to: For a patient who has...

For a patient who has an ABCD2 score ≥ 4, has had a prior TIA, or has large-vessel disease, dual antiplatelet therapy is recommended for the first 21 days, with a subsequent return to monotherapy. Dual antiplatelet therapy of clopidogrel + aspirin increases the risk of adverse reactions and has not been shown to have greater long-term benefit23-25 (TABLE 22,20,21).

Step 2: BP management. This is the next immediate step. As many as 80% of patients who present with a TIA have elevated BP upon admission. BP needs to be treated and carefully monitored during this early treatment phase. The recommendation is for a systolic BP < 185 mm Hg and a diastolic BP < 110 mm Hg.24

Step 3: Anticoagulation. Treatment with warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) is recommended for patients who have the potential for forming emboli—eg, in the setting of atrial fibrillation, ventricular thrombus, mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism.

Step 4. High-intensity statin. A statin agent is recommended as part of immediate and long-term medical management, regardless of the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level, to reduce the risk of stroke.2,24

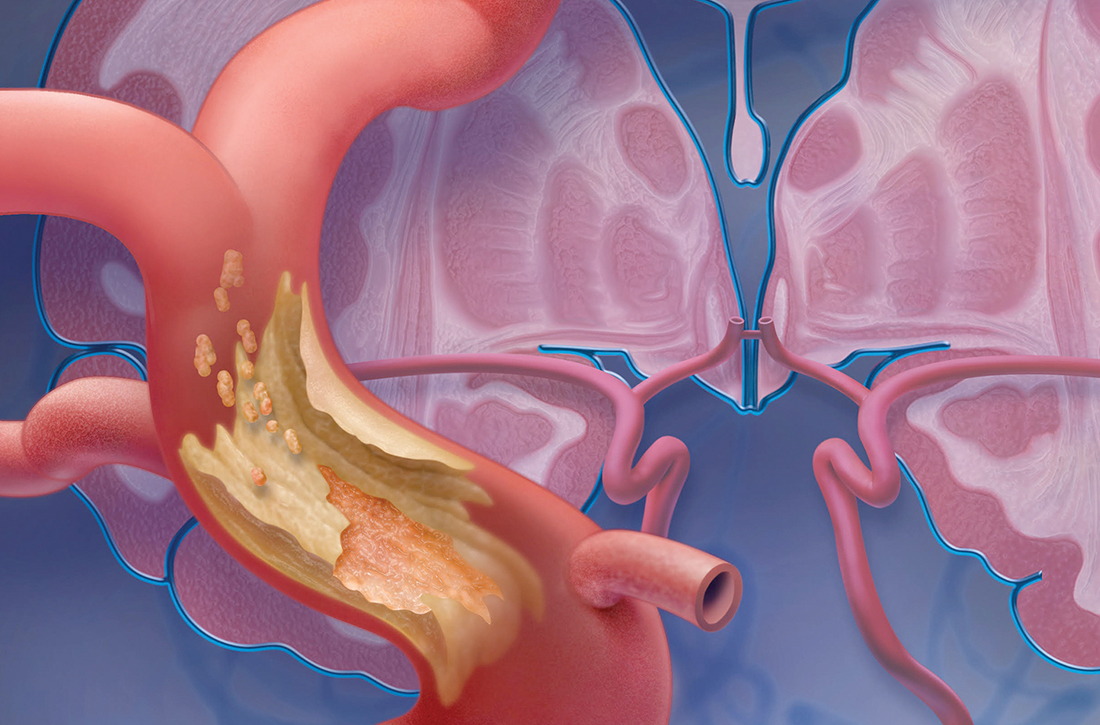

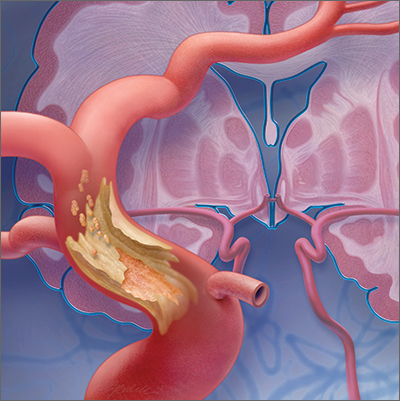

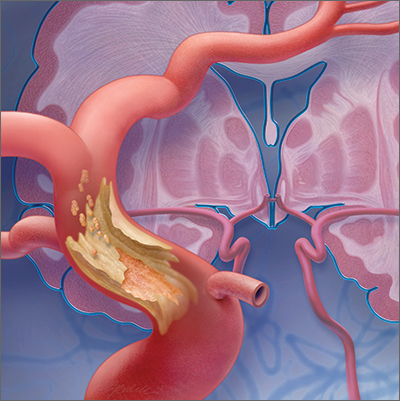

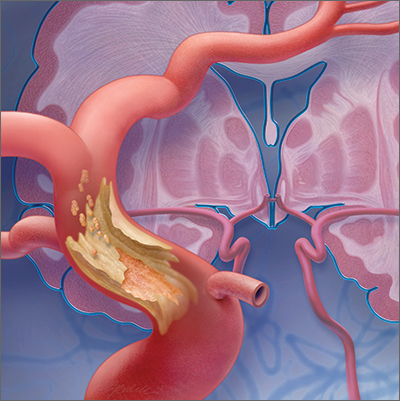

Carotid artery management. Surgical intervention is not always considered a component of immediate medical management. However, guidelines recommend that carotid endarterectomy or stenting be considered in patients who have stenosis > 70%.2

CASE

Mr. L is admitted to the hospital and undergoes neurosurgical intervention. Medical management is instituted.

Long-term management and secondary prevention

The main risk factors for stroke can be divided into modifiable, vascular, and unmodifiable. Addressing both modifiable and vascular risks is important for secondary prevention.

Continue to: Modifiable and vascular risk factors

Modifiable and vascular risk factors

Modifiable risk factors for stroke include hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and physical activity; the most important of these, for preventing subsequent stroke after an initial TIA, is hypertension.26

The 2 more significant vascular risk factors for stroke are carotid artery stenosis and atrial fibrillation.

Hypertension. Improving control of hypertension can improve secondary risk reduction for recurrent stroke. Control of both systolic and diastolic BP is important in this regard, with larger systolic BP reductions having a greater impact on decreasing the risk of recurrent stroke.24 Evidence supports lowering BP to improve secondary risk reduction in people with and without diagnosed hypertension: The goal is to lower systolic BP by ≥ 10 mm Hg and diastolic BP by 5 mm Hg.24 No particular class of antihypertensive is recommended in the first line, although preliminary evidence shows that a diuretic, with or without an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, might be more beneficial than other options.24

Diabetes. The risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke, is higher in people with diabetes. Evidence shows that various (but not all) agents in 2 pharmaceutical classes—glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the sodium glucose-2 cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitors—reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and improve secondary prevention of recurrent stroke:

- EMPA-REG OUTCOME (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01131676) was the first trial to show cardiovascular benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor (empagliflozin); subsequent studies confirmed the cardiovascular benefits found in EMPA-REG OUTCOME.27,28

- The ELIXA trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01147250) was the first to show cardiovascular benefit from a GLP-1 receptor agonist (lixisenatide); subsequent studies supported this finding.29,30

Appropriate agents in these 2 classes should be considered as first-line or adjunctive in patients with both diabetes and known cardiovascular disease, as long as there are no contraindications.27,28

Pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione-class antidiabetic agent, was once considered a potential option to improve secondary prevention of stroke. However, the thiazolidinediones are generally no longer considered; instead, the SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are favored.31

Evidence demonstrates the effect of hyperglycemia on cardiovascular events; however, it is important to note that hypoglycemia can result in symptoms and focal changes that mimic a stroke. In addition, some evidence suggests that hypoglycemia can increase cardiovascular risk—thereby supporting the importance of strict control of diabetes and maintenance of euglycemia in reducing overall cardiovascular risk.32

Continue to: Lipids

Lipids. The SPARCL trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00147602) was the first study to demonstrate the benefit of high-intensity statin therapy—specifically, atorvastatin 80 mg/d—for secondary prevention for recurrent stroke.33 The recommendation is to use high-intensity statin therapy to decrease the risk of recurrent stroke by reducing the level of LDL-C—by ≥ 50% or to < 70 mg/dL, for maximum risk reduction.24,34

The IMPROVE-IT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00202878) demonstrated the benefit of adding ezetimibe, 10 mg/d, to a moderate-to-high-intensity statin (simvastatin, 40-80 mg/d) to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.35

Results of recent studies support the use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for regulating levels of LDL-C, as an additional option to consider—if needed to further reduce the LDL-C level or if statins are contraindicated in a particular patient.34

Smoking cessation. Cigarette smoking is known to increase the risk of ischemic stroke; newer evidence shows that second-hand exposure to smoke also increases the risk of ischemic stroke.36,37 Although these studies focused on primary prevention of ischemic stroke, the data can reasonably be applied to secondary prevention.38 The recommendation for secondary prevention is to quit smoking and avoid secondhand smoke.24

Alcohol. Evidence demonstrates that heavy alcohol consumption and alcoholism increase the risk of stroke; similar to what is known about smoking, most available data relate to primary prevention.38 The recommendation for providing secondary stroke prevention is to stop or decrease alcohol intake.24

Weight reduction. Obesity (body mass index > 30) increases the risk of ischemic stroke. However, there is, as yet, no evidence that weight loss diminishes the risk of subsequent stroke for secondary prevention.24

Physical activity. Aerobic exercise and strength-training programs after a stroke improve cardiovascular health and mobility. There is no evidence that exercise leads to a reduction in the risk of subsequent stroke.24

Continue to: Nutrition

Nutrition. No current randomized controlled trials are focused on the relationship between diet and recurrent stroke for purposes of prevention; however, evidence for both BP and lipid control incorporate dietary guidance. Recommendations include reducing intake of saturated fats and of sodium (the latter, to < 2.3 g/d) and increasing intake of fruits and vegetables, both of which are beneficial for controlling BP and lipid levels and promoting overall cardiovascular health.38

Carotid artery stenosis. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated benefit from treating carotid stenosis (> 70% stenosis but not < 50%) with carotid endarterectomy to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA.2 The ideal timing of carotid endarterectomy is still being studied; however, available evidence supports intervention within 2 to 6 weeks after TIA or stroke.25 Studies are ongoing that compare carotid angioplasty and stenting against carotid endarterectomy. Medical therapy, with antiplatelet agents and statins, is recommended after carotid endarterectomy.25

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of recurrent stroke after a TIA, and is the most important indication for secondary stroke prevention with anticoagulation therapy:

- Warfarin. Several studies have shown that warfarin provides a 68% relative risk reduction and a 1.4% absolute risk reduction in the annual stroke rate.24 To achieve this reduction in risk, the optimal international normalized ratio is 2.5 (range, 2-3).24

- Aspirin provides a 13% relative risk reduction for recurrent stroke, although there is evidence that long-term anticoagulation provides more benefit than aspirin after a TIA.39-41 Optimal dosing of aspirin ranges from 75-100 mg/d; greatest benefit is likely in the 12 weeks after stroke, when the risk of recurrent stroke is highest.31,41,42

- DOACs have similar efficacy to warfarin but more rapid onset, lower risk of bleeding, fewer drug interactions, and no requirement for monitoring—often making them a more tolerable long-term choice. Options are rivaroxaban 20 mg/d, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban 5 mg twice daily, and edoxaban 60 mg/d.39

When to start anticoagulation and the choice of agent should be weighed against a risk of bleeding, which is highest after the initial stroke. Cost is also a consideration: DOACs are more expensive than warfarin.

CASE

Mr. L is discharged 3 days after carotid endarterectomy and free of residual deficits. He is started on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin + clopidogrel) for 21 days, to be followed by a return to monotherapy. He is restarted on a high-intensity statin. He is instructed to resume taking the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and melatonin for sleep, as needed. Last, he is told to schedule follow-up with his primary care physician in 7 to 10 days to begin post-stroke care.

Final thoughts

Primary care physicians are often the first point of contact for patients with current or remote TIA symptoms. Based on that provider–patient relationship, evidence supports several recommendations for diagnosing and treating a TIA and for reducing the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA. Addressing each of these areas, in this order, is imperative to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke and improve overall cardiovascular outcomes:

- Obtain an accurate diagnosis of a TIA, using DW-MRI or comparable brain imaging, to allow for prompt intervention.

- Initiate BP management promptly in the acute setting and establish optimal BP control over the long term.

- Begin appropriate antiplatelet therapy.

- When indicated (eg, atrial fibrillation), begin anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC or warfarin.

- Begin high-intensity statin therapy.

- Consider treating patients with diabetes using an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist.

- Encourage smoking cessation, prescribe quit-smoking medications, or refer a smoker for behavioral support.

Education. Last, it is important to educate patients—especially those who have risk factors for a TIA or stroke—about the presentation of events, so that they know to seek immediate medical attention.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristen Rundell, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine, 655 North Alvernon Way, Suite 228, Tucson, AZ 85711; [email protected]

1. Kleindorfer D, Panagos P, Pancioli A, et al. Incidence and short-term prognosis of transient ischemic attack in a population-based study. Stroke. 2005;36:720-723. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158917.59233.b7

2. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52:e364-e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375

3. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40:2276-2293. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218

4. Thacker EL, Wiggins KL, Rice KM, et al. Short-term and long-term risk of incident ischemic stroke after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2010;41:239-243. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569707

5. Hill MD, Yiannakoulias N, Jeerakathil T, et al. The high risk of stroke immediately after transient ischemic attack: a population-based study. Neurology. 2004;62:2015-2020. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129482.70315.2f

6. Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77:1222-1228. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182309f91

7. Cucchiara BL, Kasner SE. All patients should be admitted to the hospital after a transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43:1446-1447. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636746

8. Amarenco P. Not all patients should be admitted to the hospital for observation after a transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43:1448-1449. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636753

9. Amort M, Fluri F, Schäfer J, et al. Transient ischemic attack versus transient ischemic attack mimics: frequency, clinical characteristics and outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:57-64. doi: 10.1159/000327034

10. Hand PJ, Kwan J, Lindley RI, et al. Distinguishing between stroke and mimic at the bedside: The Brain Attack Study. Stroke. 2006;37:769-775. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204041.13466.4c

11. Shah KH, Edlow JA. Transient ischemic attack: review for the emergency physician. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:592-604. doi: 10.1016/S0196064404000058

12. Crisostomo RA, Garcia MM, Tong DC. Detection of diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities in patients with transient ischemic attack: correlation with clinical characteristics. Stroke. 2003;34:932-937. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000061496.00669.5E

13. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al; ; ; ; ; . Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486

14. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369:283-292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0

15. Cucchiara BL, Messe SR, Taylor RA, et al. Is the ABCD score useful for risk stratification of patients with acute transient ischemic attack? Stroke. 2006;37:1710-1714. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000227195.46336.93

16. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al; . One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412981

17. Wu CM, McLaughlin K, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2417-2422. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2417

18. Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: time window for prevention is very short. Neurology. 2005;64:817-820. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152985.32732.EE

19. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160-2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024

20. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432-1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2

21. Hackam DG, Spence JD. Antiplatelet therapy in ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: an overview of major trials and meta-analyses. Stroke. 2019;50:773-778. doi: c10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023954

22. Bhatia K, Jain V, Aggarwal D, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2021;52:e217-e223. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.033033

23. Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhao X, et al; CHANCE Investigators. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHANCE) trial: one-year outcomes. Circulation. 2015;132:40-46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014791

24. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al; . Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043

25. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158

26. O’Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, et al; INTERSTROKE Investigators. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;388:761-775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30506-2

27. Kristensen SL, Rørth R, Jhund PS, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:776-785. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30249-9

28. Bertoccini L, Baroni MG. GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: new insights and opportunities for cardiovascular protection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1307:193-212. doi:10.1007/5584_2020_494

29. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al; ELIXA Investigators. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2247-2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225

30. Sheahan KH, Wahlberg EA, Gilbert MP. An overview of GLP-1 agonists and recent cardiovascular outcomes trials. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96:156-161. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-137186

31. Kim AS. Medical management for secondary stroke prevention. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2020;26:435-456. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000849

32. Smith L, Chakraborty D, Bhattacharya P, et al. Exposure to hypoglycemia and risk of stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1431:25-34. doi:10.1111/nyas.13872

33. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A 3rd, et al; . High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061894

34. Castilla-Guerra, L, Fernandez-Moreno M, Leon-Jimenez D, et al. Statins in ischemic stroke prevention: what have we learned in the post-SPARCL (The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels) decade? Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21:22. doi: 10.1007/s11940-019-0563-4

35. Bohula EA, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, et al. Prevention of stroke with the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome in IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial). Circulation. 2017;136:2440-2450. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029095

36. Moritsugu KP. The 2006 report of the Surgeon General: the health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 20067;32:542-543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.026

37. Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Kannel WB, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. JAMA. 1988;259:1025-1029.

38. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke. 2006;37:1583-1633. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000223048.70103.F1

39. Klijn CJ, Paciaroni M, Berge E, et al. Antithrombotic treatment for secondary prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic events in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack and non-valvular atrial fibrillation: A European Stroke Organisation guideline. Eur Stroke J. 2019;4:198-223. doi:10.1177/2396987319841187

40. Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849-1860. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1

41. Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 suppl):546S–592S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0678

42. Rothwell PM, Algra A, Chen Z, et al. Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;388:365-375. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30468-8

As many as 240,000 people per year in the United States experience a transient ischemic attack (TIA),1,2 which is now defined by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association as a “transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia, without acute infarction.”3 An older definition of TIA was based on the duration of the event (ie, resolution of symptoms at 24 hours); in the updated (2009) definition, the diagnostic criterion is the extent of focal tissue damage.3 Using the 2009 definition might mean a decrease in the number of patients who have a diagnosis of a TIA and an increase in the number who are determined to have had a stroke because an infarction is found on initial imaging.

Guided by the 2009 revised definition of a TIA, we review here the work-up and treatment of TIA, emphasizing immediacy of management to (1) prevent further tissue damage and (2) decrease the risk of a second event.

CASE

Martin L, 69 years old, retired, a nonsmoker, and with a history of peripheral arterial disease and hypercholesterolemia, presents to the emergency department (ED) of a rural hospital complaining of slurred speech and left-side facial numbness. He had an episode of facial numbness that lasted 30 minutes, then resolved, each of the 2 previous evenings; he did not seek care at those times. Now, in the ED, Mr. L is normotensive.

The patient’s medication history includes a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and melatonin to improve sleep. He reports having discontinued a statin because he could not tolerate its adverse effects.

What immediate steps are recommended for Mr. L’s care?

Common event callsfor quick action

A TIA is the strongest predictor of subsequent stroke and stroke-related death; the highest period of risk of these devastating outcomes is immediately following a TIA.1,2,4,5 It is essential, therefore, for the physician who sees a patient with a current complaint or recent history of suspected focal neurologic deficits to direct that patient to an ED for an accurate diagnosis and, as appropriate, early treatment for the best possible outcome.

Imaging—preferably, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI), the gold standard for diagnosing stroke (see “Diagnosis includes ruling out mimics”)2,3—should be performed as soon as the patient with a suspected TIA arrives in the ED. Imaging should not be held while waiting for a stroke to declare itself—ie, by allowing symptoms to persist for longer than 24 hours. 6

Continue to: Late presentation

Late presentation. Some patients present ≥ 48 hours after onset of early symptoms of a TIA; for them, the work-up is the same as for prompt presentation but can be completed in the outpatient clinic—as long as the patient is stable clinically and imaging is accessible there. DW-MRI should be completed within 48 hours after late presentation. In such cases, the patient should be cautioned regarding risks and any recurrence of symptoms.7,8

Diagnosis includes ruling out mimics

All patients in whom a stroke is suspected should be evaluated on an emergency basis with brain imaging upon arrival at the hospital, before any therapy is initiated. As noted, DW-MRI is the preferred modality; noncontrast computed tomography (CT) or CT angiography can be used if MRI is unavailable.2,3

Mimics. Stroke has many mimics; quickly eliminating them from the differential diagnosis is important so that appropriate therapy can be initiated. Mimics usually have a prolonged presentation of symptoms, whereas the presentation of a TIA is usually abrupt. The 3 more common diagnoses that mimic a TIA are migraine with aura, seizure, and syncope.9,10 Symptoms that generally are not associated with a TIA are chest pain, generalized weakness, and confusion.11 A complete history and physical exam provide the path to the imaging, laboratory, and cardiac testing that is needed to differentiate these diagnoses from a TIA.

A thorough history is best obtained from the patient and a witness, if available, and should include identification of any focal neurologic deficits and the duration and time to resolution of symptoms. Obtain a history of risk factors for ischemia—tobacco use, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, previous TIA or stroke, atrial fibrillation, and any coagulopathy. Ask questions about a family history of TIA, stroke, and coagulopathy.11

A comprehensive physical exam, including vital signs, cardiac exam, a check for carotid bruits, and complete neurologic exam, should be performed. Most patients present with concerns for unilateral weakness and changes in speech, which are usually associated with infarction on DW-MRI.12 The most common findings on physical exam include cranial nerve abnormalities, such as diplopia, hemianopia, monocular blindness, disconjugate gaze, facial drooping, lateral tongue movement, dysphagia, and vestibular dysfunction. Cerebellar abnormalities are also often noted, including past pointing, dystaxia, ataxia, nystagmus, and motor abnormalities (eg, spasticity, clonus, or unilateral weakness in the face or extremities).11

Electrocardiography at the bedside can confirm atrial fibrillation or another arrhythmia quickly.

Essential laboratory testing includes measurement of blood glucose and serum electrolytes to determine if these particular imbalances are the cause of symptoms. The presence of a hypercoaguable state is determined by a complete blood count and coagulation studies.3,13 Urine toxicology should also be obtained to rule out other causes of symptoms. A lipid profile is beneficial for making long-term treatment decisions.

Continue to: ABCD2 score

ABCD2 score. Patients who have had a TIA and present within 72 hours after symptoms have resolved should be hospitalized if they have an ABCD2 (Age, Blood pressure [BP], Clinical presentation, Diabetes mellitus [type 1 or 2], Duration of symptoms) prediction system score > 3.14 ABCD2 criteria can be used to help identify patients who are at higher risk of stroke or need further therapy (TABLE 1).14,15

The ABCD2 score is also used to determine whether a patient needs dual antiplatelet therapy. Patients who score at the higher end of the ABCD2 system usually have an increased risk of stroke, longer hospitalization, and greater disability.

CASE

In the ED, Mr. L is immediately assessed and airlifted to a larger regional medical center, where MRI confirms a stroke.

Management

Initial management of a TIA is aimed at reducing the risk of recurrent TIA or stroke. Early medical and possibly surgical treatment are key for preventing stroke and improving outcomes. The first 48 hours after a TIA are the most critical because the incidence of recurrent TIA or stroke is highest during this period.16-18

What is the accepted strategy for early treatment?

Initial treatment must include antiplatelet therapy, BP management, anticoagulation, statin therapy, and carotid endarterectomy as indicated.2,19,20 Control of hypertension and anticoagulation decrease the risk of recurrent stroke by the largest margin20; both are “A”-level Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy interventions.2,3

Step 1: Antiplatelet therapy. After initial imaging is complete and if there are no contraindications, antiplatelet agents are recommended for patients who have had a noncardioembolic TIA. The American Heart Association and American Stroke Association recommend either aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole + aspirin (available in a single capsule [Aggrenox]), or clopidogrel + aspirin as first-line therapy.2,20 The choice of agent needs to be individualized, based on tolerability and adverse effects (TABLE 22,20,21).

A meta-analysis of antiplatelet therapy reviewed the optimum dosing of each medication.21,22 Reduction of the risk of ischemic stroke with aspirin is 21% to 22% at the optimal dosing of 75 to 150 mg/d, which also reduces the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Continue to: For a patient who has...

For a patient who has an ABCD2 score ≥ 4, has had a prior TIA, or has large-vessel disease, dual antiplatelet therapy is recommended for the first 21 days, with a subsequent return to monotherapy. Dual antiplatelet therapy of clopidogrel + aspirin increases the risk of adverse reactions and has not been shown to have greater long-term benefit23-25 (TABLE 22,20,21).

Step 2: BP management. This is the next immediate step. As many as 80% of patients who present with a TIA have elevated BP upon admission. BP needs to be treated and carefully monitored during this early treatment phase. The recommendation is for a systolic BP < 185 mm Hg and a diastolic BP < 110 mm Hg.24

Step 3: Anticoagulation. Treatment with warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) is recommended for patients who have the potential for forming emboli—eg, in the setting of atrial fibrillation, ventricular thrombus, mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism.

Step 4. High-intensity statin. A statin agent is recommended as part of immediate and long-term medical management, regardless of the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level, to reduce the risk of stroke.2,24

Carotid artery management. Surgical intervention is not always considered a component of immediate medical management. However, guidelines recommend that carotid endarterectomy or stenting be considered in patients who have stenosis > 70%.2

CASE

Mr. L is admitted to the hospital and undergoes neurosurgical intervention. Medical management is instituted.

Long-term management and secondary prevention

The main risk factors for stroke can be divided into modifiable, vascular, and unmodifiable. Addressing both modifiable and vascular risks is important for secondary prevention.

Continue to: Modifiable and vascular risk factors

Modifiable and vascular risk factors

Modifiable risk factors for stroke include hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and physical activity; the most important of these, for preventing subsequent stroke after an initial TIA, is hypertension.26

The 2 more significant vascular risk factors for stroke are carotid artery stenosis and atrial fibrillation.

Hypertension. Improving control of hypertension can improve secondary risk reduction for recurrent stroke. Control of both systolic and diastolic BP is important in this regard, with larger systolic BP reductions having a greater impact on decreasing the risk of recurrent stroke.24 Evidence supports lowering BP to improve secondary risk reduction in people with and without diagnosed hypertension: The goal is to lower systolic BP by ≥ 10 mm Hg and diastolic BP by 5 mm Hg.24 No particular class of antihypertensive is recommended in the first line, although preliminary evidence shows that a diuretic, with or without an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, might be more beneficial than other options.24

Diabetes. The risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke, is higher in people with diabetes. Evidence shows that various (but not all) agents in 2 pharmaceutical classes—glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the sodium glucose-2 cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitors—reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and improve secondary prevention of recurrent stroke:

- EMPA-REG OUTCOME (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01131676) was the first trial to show cardiovascular benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor (empagliflozin); subsequent studies confirmed the cardiovascular benefits found in EMPA-REG OUTCOME.27,28

- The ELIXA trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01147250) was the first to show cardiovascular benefit from a GLP-1 receptor agonist (lixisenatide); subsequent studies supported this finding.29,30

Appropriate agents in these 2 classes should be considered as first-line or adjunctive in patients with both diabetes and known cardiovascular disease, as long as there are no contraindications.27,28

Pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione-class antidiabetic agent, was once considered a potential option to improve secondary prevention of stroke. However, the thiazolidinediones are generally no longer considered; instead, the SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are favored.31

Evidence demonstrates the effect of hyperglycemia on cardiovascular events; however, it is important to note that hypoglycemia can result in symptoms and focal changes that mimic a stroke. In addition, some evidence suggests that hypoglycemia can increase cardiovascular risk—thereby supporting the importance of strict control of diabetes and maintenance of euglycemia in reducing overall cardiovascular risk.32

Continue to: Lipids

Lipids. The SPARCL trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00147602) was the first study to demonstrate the benefit of high-intensity statin therapy—specifically, atorvastatin 80 mg/d—for secondary prevention for recurrent stroke.33 The recommendation is to use high-intensity statin therapy to decrease the risk of recurrent stroke by reducing the level of LDL-C—by ≥ 50% or to < 70 mg/dL, for maximum risk reduction.24,34

The IMPROVE-IT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00202878) demonstrated the benefit of adding ezetimibe, 10 mg/d, to a moderate-to-high-intensity statin (simvastatin, 40-80 mg/d) to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.35

Results of recent studies support the use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for regulating levels of LDL-C, as an additional option to consider—if needed to further reduce the LDL-C level or if statins are contraindicated in a particular patient.34

Smoking cessation. Cigarette smoking is known to increase the risk of ischemic stroke; newer evidence shows that second-hand exposure to smoke also increases the risk of ischemic stroke.36,37 Although these studies focused on primary prevention of ischemic stroke, the data can reasonably be applied to secondary prevention.38 The recommendation for secondary prevention is to quit smoking and avoid secondhand smoke.24

Alcohol. Evidence demonstrates that heavy alcohol consumption and alcoholism increase the risk of stroke; similar to what is known about smoking, most available data relate to primary prevention.38 The recommendation for providing secondary stroke prevention is to stop or decrease alcohol intake.24

Weight reduction. Obesity (body mass index > 30) increases the risk of ischemic stroke. However, there is, as yet, no evidence that weight loss diminishes the risk of subsequent stroke for secondary prevention.24

Physical activity. Aerobic exercise and strength-training programs after a stroke improve cardiovascular health and mobility. There is no evidence that exercise leads to a reduction in the risk of subsequent stroke.24

Continue to: Nutrition

Nutrition. No current randomized controlled trials are focused on the relationship between diet and recurrent stroke for purposes of prevention; however, evidence for both BP and lipid control incorporate dietary guidance. Recommendations include reducing intake of saturated fats and of sodium (the latter, to < 2.3 g/d) and increasing intake of fruits and vegetables, both of which are beneficial for controlling BP and lipid levels and promoting overall cardiovascular health.38

Carotid artery stenosis. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated benefit from treating carotid stenosis (> 70% stenosis but not < 50%) with carotid endarterectomy to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA.2 The ideal timing of carotid endarterectomy is still being studied; however, available evidence supports intervention within 2 to 6 weeks after TIA or stroke.25 Studies are ongoing that compare carotid angioplasty and stenting against carotid endarterectomy. Medical therapy, with antiplatelet agents and statins, is recommended after carotid endarterectomy.25

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of recurrent stroke after a TIA, and is the most important indication for secondary stroke prevention with anticoagulation therapy:

- Warfarin. Several studies have shown that warfarin provides a 68% relative risk reduction and a 1.4% absolute risk reduction in the annual stroke rate.24 To achieve this reduction in risk, the optimal international normalized ratio is 2.5 (range, 2-3).24

- Aspirin provides a 13% relative risk reduction for recurrent stroke, although there is evidence that long-term anticoagulation provides more benefit than aspirin after a TIA.39-41 Optimal dosing of aspirin ranges from 75-100 mg/d; greatest benefit is likely in the 12 weeks after stroke, when the risk of recurrent stroke is highest.31,41,42

- DOACs have similar efficacy to warfarin but more rapid onset, lower risk of bleeding, fewer drug interactions, and no requirement for monitoring—often making them a more tolerable long-term choice. Options are rivaroxaban 20 mg/d, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban 5 mg twice daily, and edoxaban 60 mg/d.39

When to start anticoagulation and the choice of agent should be weighed against a risk of bleeding, which is highest after the initial stroke. Cost is also a consideration: DOACs are more expensive than warfarin.

CASE

Mr. L is discharged 3 days after carotid endarterectomy and free of residual deficits. He is started on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin + clopidogrel) for 21 days, to be followed by a return to monotherapy. He is restarted on a high-intensity statin. He is instructed to resume taking the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and melatonin for sleep, as needed. Last, he is told to schedule follow-up with his primary care physician in 7 to 10 days to begin post-stroke care.

Final thoughts

Primary care physicians are often the first point of contact for patients with current or remote TIA symptoms. Based on that provider–patient relationship, evidence supports several recommendations for diagnosing and treating a TIA and for reducing the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA. Addressing each of these areas, in this order, is imperative to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke and improve overall cardiovascular outcomes:

- Obtain an accurate diagnosis of a TIA, using DW-MRI or comparable brain imaging, to allow for prompt intervention.

- Initiate BP management promptly in the acute setting and establish optimal BP control over the long term.

- Begin appropriate antiplatelet therapy.

- When indicated (eg, atrial fibrillation), begin anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC or warfarin.

- Begin high-intensity statin therapy.

- Consider treating patients with diabetes using an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist.

- Encourage smoking cessation, prescribe quit-smoking medications, or refer a smoker for behavioral support.

Education. Last, it is important to educate patients—especially those who have risk factors for a TIA or stroke—about the presentation of events, so that they know to seek immediate medical attention.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristen Rundell, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine, 655 North Alvernon Way, Suite 228, Tucson, AZ 85711; [email protected]

As many as 240,000 people per year in the United States experience a transient ischemic attack (TIA),1,2 which is now defined by the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association as a “transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord, or retinal ischemia, without acute infarction.”3 An older definition of TIA was based on the duration of the event (ie, resolution of symptoms at 24 hours); in the updated (2009) definition, the diagnostic criterion is the extent of focal tissue damage.3 Using the 2009 definition might mean a decrease in the number of patients who have a diagnosis of a TIA and an increase in the number who are determined to have had a stroke because an infarction is found on initial imaging.

Guided by the 2009 revised definition of a TIA, we review here the work-up and treatment of TIA, emphasizing immediacy of management to (1) prevent further tissue damage and (2) decrease the risk of a second event.

CASE

Martin L, 69 years old, retired, a nonsmoker, and with a history of peripheral arterial disease and hypercholesterolemia, presents to the emergency department (ED) of a rural hospital complaining of slurred speech and left-side facial numbness. He had an episode of facial numbness that lasted 30 minutes, then resolved, each of the 2 previous evenings; he did not seek care at those times. Now, in the ED, Mr. L is normotensive.

The patient’s medication history includes a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and melatonin to improve sleep. He reports having discontinued a statin because he could not tolerate its adverse effects.

What immediate steps are recommended for Mr. L’s care?

Common event callsfor quick action

A TIA is the strongest predictor of subsequent stroke and stroke-related death; the highest period of risk of these devastating outcomes is immediately following a TIA.1,2,4,5 It is essential, therefore, for the physician who sees a patient with a current complaint or recent history of suspected focal neurologic deficits to direct that patient to an ED for an accurate diagnosis and, as appropriate, early treatment for the best possible outcome.

Imaging—preferably, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI), the gold standard for diagnosing stroke (see “Diagnosis includes ruling out mimics”)2,3—should be performed as soon as the patient with a suspected TIA arrives in the ED. Imaging should not be held while waiting for a stroke to declare itself—ie, by allowing symptoms to persist for longer than 24 hours. 6

Continue to: Late presentation

Late presentation. Some patients present ≥ 48 hours after onset of early symptoms of a TIA; for them, the work-up is the same as for prompt presentation but can be completed in the outpatient clinic—as long as the patient is stable clinically and imaging is accessible there. DW-MRI should be completed within 48 hours after late presentation. In such cases, the patient should be cautioned regarding risks and any recurrence of symptoms.7,8

Diagnosis includes ruling out mimics

All patients in whom a stroke is suspected should be evaluated on an emergency basis with brain imaging upon arrival at the hospital, before any therapy is initiated. As noted, DW-MRI is the preferred modality; noncontrast computed tomography (CT) or CT angiography can be used if MRI is unavailable.2,3

Mimics. Stroke has many mimics; quickly eliminating them from the differential diagnosis is important so that appropriate therapy can be initiated. Mimics usually have a prolonged presentation of symptoms, whereas the presentation of a TIA is usually abrupt. The 3 more common diagnoses that mimic a TIA are migraine with aura, seizure, and syncope.9,10 Symptoms that generally are not associated with a TIA are chest pain, generalized weakness, and confusion.11 A complete history and physical exam provide the path to the imaging, laboratory, and cardiac testing that is needed to differentiate these diagnoses from a TIA.

A thorough history is best obtained from the patient and a witness, if available, and should include identification of any focal neurologic deficits and the duration and time to resolution of symptoms. Obtain a history of risk factors for ischemia—tobacco use, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, previous TIA or stroke, atrial fibrillation, and any coagulopathy. Ask questions about a family history of TIA, stroke, and coagulopathy.11

A comprehensive physical exam, including vital signs, cardiac exam, a check for carotid bruits, and complete neurologic exam, should be performed. Most patients present with concerns for unilateral weakness and changes in speech, which are usually associated with infarction on DW-MRI.12 The most common findings on physical exam include cranial nerve abnormalities, such as diplopia, hemianopia, monocular blindness, disconjugate gaze, facial drooping, lateral tongue movement, dysphagia, and vestibular dysfunction. Cerebellar abnormalities are also often noted, including past pointing, dystaxia, ataxia, nystagmus, and motor abnormalities (eg, spasticity, clonus, or unilateral weakness in the face or extremities).11

Electrocardiography at the bedside can confirm atrial fibrillation or another arrhythmia quickly.

Essential laboratory testing includes measurement of blood glucose and serum electrolytes to determine if these particular imbalances are the cause of symptoms. The presence of a hypercoaguable state is determined by a complete blood count and coagulation studies.3,13 Urine toxicology should also be obtained to rule out other causes of symptoms. A lipid profile is beneficial for making long-term treatment decisions.

Continue to: ABCD2 score

ABCD2 score. Patients who have had a TIA and present within 72 hours after symptoms have resolved should be hospitalized if they have an ABCD2 (Age, Blood pressure [BP], Clinical presentation, Diabetes mellitus [type 1 or 2], Duration of symptoms) prediction system score > 3.14 ABCD2 criteria can be used to help identify patients who are at higher risk of stroke or need further therapy (TABLE 1).14,15

The ABCD2 score is also used to determine whether a patient needs dual antiplatelet therapy. Patients who score at the higher end of the ABCD2 system usually have an increased risk of stroke, longer hospitalization, and greater disability.

CASE

In the ED, Mr. L is immediately assessed and airlifted to a larger regional medical center, where MRI confirms a stroke.

Management

Initial management of a TIA is aimed at reducing the risk of recurrent TIA or stroke. Early medical and possibly surgical treatment are key for preventing stroke and improving outcomes. The first 48 hours after a TIA are the most critical because the incidence of recurrent TIA or stroke is highest during this period.16-18

What is the accepted strategy for early treatment?

Initial treatment must include antiplatelet therapy, BP management, anticoagulation, statin therapy, and carotid endarterectomy as indicated.2,19,20 Control of hypertension and anticoagulation decrease the risk of recurrent stroke by the largest margin20; both are “A”-level Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy interventions.2,3

Step 1: Antiplatelet therapy. After initial imaging is complete and if there are no contraindications, antiplatelet agents are recommended for patients who have had a noncardioembolic TIA. The American Heart Association and American Stroke Association recommend either aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole + aspirin (available in a single capsule [Aggrenox]), or clopidogrel + aspirin as first-line therapy.2,20 The choice of agent needs to be individualized, based on tolerability and adverse effects (TABLE 22,20,21).

A meta-analysis of antiplatelet therapy reviewed the optimum dosing of each medication.21,22 Reduction of the risk of ischemic stroke with aspirin is 21% to 22% at the optimal dosing of 75 to 150 mg/d, which also reduces the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Continue to: For a patient who has...

For a patient who has an ABCD2 score ≥ 4, has had a prior TIA, or has large-vessel disease, dual antiplatelet therapy is recommended for the first 21 days, with a subsequent return to monotherapy. Dual antiplatelet therapy of clopidogrel + aspirin increases the risk of adverse reactions and has not been shown to have greater long-term benefit23-25 (TABLE 22,20,21).

Step 2: BP management. This is the next immediate step. As many as 80% of patients who present with a TIA have elevated BP upon admission. BP needs to be treated and carefully monitored during this early treatment phase. The recommendation is for a systolic BP < 185 mm Hg and a diastolic BP < 110 mm Hg.24

Step 3: Anticoagulation. Treatment with warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) is recommended for patients who have the potential for forming emboli—eg, in the setting of atrial fibrillation, ventricular thrombus, mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism.

Step 4. High-intensity statin. A statin agent is recommended as part of immediate and long-term medical management, regardless of the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level, to reduce the risk of stroke.2,24

Carotid artery management. Surgical intervention is not always considered a component of immediate medical management. However, guidelines recommend that carotid endarterectomy or stenting be considered in patients who have stenosis > 70%.2

CASE

Mr. L is admitted to the hospital and undergoes neurosurgical intervention. Medical management is instituted.

Long-term management and secondary prevention

The main risk factors for stroke can be divided into modifiable, vascular, and unmodifiable. Addressing both modifiable and vascular risks is important for secondary prevention.

Continue to: Modifiable and vascular risk factors

Modifiable and vascular risk factors

Modifiable risk factors for stroke include hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking, and physical activity; the most important of these, for preventing subsequent stroke after an initial TIA, is hypertension.26

The 2 more significant vascular risk factors for stroke are carotid artery stenosis and atrial fibrillation.

Hypertension. Improving control of hypertension can improve secondary risk reduction for recurrent stroke. Control of both systolic and diastolic BP is important in this regard, with larger systolic BP reductions having a greater impact on decreasing the risk of recurrent stroke.24 Evidence supports lowering BP to improve secondary risk reduction in people with and without diagnosed hypertension: The goal is to lower systolic BP by ≥ 10 mm Hg and diastolic BP by 5 mm Hg.24 No particular class of antihypertensive is recommended in the first line, although preliminary evidence shows that a diuretic, with or without an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, might be more beneficial than other options.24

Diabetes. The risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke, is higher in people with diabetes. Evidence shows that various (but not all) agents in 2 pharmaceutical classes—glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the sodium glucose-2 cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitors—reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and improve secondary prevention of recurrent stroke:

- EMPA-REG OUTCOME (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01131676) was the first trial to show cardiovascular benefit from an SGLT2 inhibitor (empagliflozin); subsequent studies confirmed the cardiovascular benefits found in EMPA-REG OUTCOME.27,28

- The ELIXA trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01147250) was the first to show cardiovascular benefit from a GLP-1 receptor agonist (lixisenatide); subsequent studies supported this finding.29,30

Appropriate agents in these 2 classes should be considered as first-line or adjunctive in patients with both diabetes and known cardiovascular disease, as long as there are no contraindications.27,28

Pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione-class antidiabetic agent, was once considered a potential option to improve secondary prevention of stroke. However, the thiazolidinediones are generally no longer considered; instead, the SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists are favored.31

Evidence demonstrates the effect of hyperglycemia on cardiovascular events; however, it is important to note that hypoglycemia can result in symptoms and focal changes that mimic a stroke. In addition, some evidence suggests that hypoglycemia can increase cardiovascular risk—thereby supporting the importance of strict control of diabetes and maintenance of euglycemia in reducing overall cardiovascular risk.32

Continue to: Lipids

Lipids. The SPARCL trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00147602) was the first study to demonstrate the benefit of high-intensity statin therapy—specifically, atorvastatin 80 mg/d—for secondary prevention for recurrent stroke.33 The recommendation is to use high-intensity statin therapy to decrease the risk of recurrent stroke by reducing the level of LDL-C—by ≥ 50% or to < 70 mg/dL, for maximum risk reduction.24,34

The IMPROVE-IT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00202878) demonstrated the benefit of adding ezetimibe, 10 mg/d, to a moderate-to-high-intensity statin (simvastatin, 40-80 mg/d) to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke.35

Results of recent studies support the use of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors for regulating levels of LDL-C, as an additional option to consider—if needed to further reduce the LDL-C level or if statins are contraindicated in a particular patient.34

Smoking cessation. Cigarette smoking is known to increase the risk of ischemic stroke; newer evidence shows that second-hand exposure to smoke also increases the risk of ischemic stroke.36,37 Although these studies focused on primary prevention of ischemic stroke, the data can reasonably be applied to secondary prevention.38 The recommendation for secondary prevention is to quit smoking and avoid secondhand smoke.24

Alcohol. Evidence demonstrates that heavy alcohol consumption and alcoholism increase the risk of stroke; similar to what is known about smoking, most available data relate to primary prevention.38 The recommendation for providing secondary stroke prevention is to stop or decrease alcohol intake.24

Weight reduction. Obesity (body mass index > 30) increases the risk of ischemic stroke. However, there is, as yet, no evidence that weight loss diminishes the risk of subsequent stroke for secondary prevention.24

Physical activity. Aerobic exercise and strength-training programs after a stroke improve cardiovascular health and mobility. There is no evidence that exercise leads to a reduction in the risk of subsequent stroke.24

Continue to: Nutrition

Nutrition. No current randomized controlled trials are focused on the relationship between diet and recurrent stroke for purposes of prevention; however, evidence for both BP and lipid control incorporate dietary guidance. Recommendations include reducing intake of saturated fats and of sodium (the latter, to < 2.3 g/d) and increasing intake of fruits and vegetables, both of which are beneficial for controlling BP and lipid levels and promoting overall cardiovascular health.38

Carotid artery stenosis. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated benefit from treating carotid stenosis (> 70% stenosis but not < 50%) with carotid endarterectomy to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA.2 The ideal timing of carotid endarterectomy is still being studied; however, available evidence supports intervention within 2 to 6 weeks after TIA or stroke.25 Studies are ongoing that compare carotid angioplasty and stenting against carotid endarterectomy. Medical therapy, with antiplatelet agents and statins, is recommended after carotid endarterectomy.25

Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of recurrent stroke after a TIA, and is the most important indication for secondary stroke prevention with anticoagulation therapy:

- Warfarin. Several studies have shown that warfarin provides a 68% relative risk reduction and a 1.4% absolute risk reduction in the annual stroke rate.24 To achieve this reduction in risk, the optimal international normalized ratio is 2.5 (range, 2-3).24

- Aspirin provides a 13% relative risk reduction for recurrent stroke, although there is evidence that long-term anticoagulation provides more benefit than aspirin after a TIA.39-41 Optimal dosing of aspirin ranges from 75-100 mg/d; greatest benefit is likely in the 12 weeks after stroke, when the risk of recurrent stroke is highest.31,41,42

- DOACs have similar efficacy to warfarin but more rapid onset, lower risk of bleeding, fewer drug interactions, and no requirement for monitoring—often making them a more tolerable long-term choice. Options are rivaroxaban 20 mg/d, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily, apixaban 5 mg twice daily, and edoxaban 60 mg/d.39

When to start anticoagulation and the choice of agent should be weighed against a risk of bleeding, which is highest after the initial stroke. Cost is also a consideration: DOACs are more expensive than warfarin.

CASE

Mr. L is discharged 3 days after carotid endarterectomy and free of residual deficits. He is started on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin + clopidogrel) for 21 days, to be followed by a return to monotherapy. He is restarted on a high-intensity statin. He is instructed to resume taking the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and melatonin for sleep, as needed. Last, he is told to schedule follow-up with his primary care physician in 7 to 10 days to begin post-stroke care.

Final thoughts

Primary care physicians are often the first point of contact for patients with current or remote TIA symptoms. Based on that provider–patient relationship, evidence supports several recommendations for diagnosing and treating a TIA and for reducing the risk of recurrent stroke after TIA. Addressing each of these areas, in this order, is imperative to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke and improve overall cardiovascular outcomes:

- Obtain an accurate diagnosis of a TIA, using DW-MRI or comparable brain imaging, to allow for prompt intervention.

- Initiate BP management promptly in the acute setting and establish optimal BP control over the long term.

- Begin appropriate antiplatelet therapy.

- When indicated (eg, atrial fibrillation), begin anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC or warfarin.

- Begin high-intensity statin therapy.

- Consider treating patients with diabetes using an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist.

- Encourage smoking cessation, prescribe quit-smoking medications, or refer a smoker for behavioral support.

Education. Last, it is important to educate patients—especially those who have risk factors for a TIA or stroke—about the presentation of events, so that they know to seek immediate medical attention.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kristen Rundell, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine, 655 North Alvernon Way, Suite 228, Tucson, AZ 85711; [email protected]

1. Kleindorfer D, Panagos P, Pancioli A, et al. Incidence and short-term prognosis of transient ischemic attack in a population-based study. Stroke. 2005;36:720-723. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158917.59233.b7

2. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S, et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021;52:e364-e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375

3. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40:2276-2293. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218

4. Thacker EL, Wiggins KL, Rice KM, et al. Short-term and long-term risk of incident ischemic stroke after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2010;41:239-243. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569707

5. Hill MD, Yiannakoulias N, Jeerakathil T, et al. The high risk of stroke immediately after transient ischemic attack: a population-based study. Neurology. 2004;62:2015-2020. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129482.70315.2f

6. Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Early stroke risk and ABCD2 score performance in tissue- vs time-defined TIA: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2011;77:1222-1228. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182309f91

7. Cucchiara BL, Kasner SE. All patients should be admitted to the hospital after a transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43:1446-1447. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636746

8. Amarenco P. Not all patients should be admitted to the hospital for observation after a transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2012;43:1448-1449. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.636753

9. Amort M, Fluri F, Schäfer J, et al. Transient ischemic attack versus transient ischemic attack mimics: frequency, clinical characteristics and outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:57-64. doi: 10.1159/000327034

10. Hand PJ, Kwan J, Lindley RI, et al. Distinguishing between stroke and mimic at the bedside: The Brain Attack Study. Stroke. 2006;37:769-775. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000204041.13466.4c

11. Shah KH, Edlow JA. Transient ischemic attack: review for the emergency physician. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:592-604. doi: 10.1016/S0196064404000058

12. Crisostomo RA, Garcia MM, Tong DC. Detection of diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities in patients with transient ischemic attack: correlation with clinical characteristics. Stroke. 2003;34:932-937. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000061496.00669.5E

13. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, et al; ; ; ; ; . Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486

14. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369:283-292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0

15. Cucchiara BL, Messe SR, Taylor RA, et al. Is the ABCD score useful for risk stratification of patients with acute transient ischemic attack? Stroke. 2006;37:1710-1714. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000227195.46336.93

16. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al; . One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412981

17. Wu CM, McLaughlin K, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2417-2422. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2417

18. Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: time window for prevention is very short. Neurology. 2005;64:817-820. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152985.32732.EE

19. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160-2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024

20. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432-1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2

21. Hackam DG, Spence JD. Antiplatelet therapy in ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack: an overview of major trials and meta-analyses. Stroke. 2019;50:773-778. doi: c10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023954

22. Bhatia K, Jain V, Aggarwal D, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2021;52:e217-e223. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.033033

23. Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhao X, et al; CHANCE Investigators. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHANCE) trial: one-year outcomes. Circulation. 2015;132:40-46. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014791

24. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al; . Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043

25. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158

26. O’Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, et al; INTERSTROKE Investigators. Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;388:761-775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30506-2

27. Kristensen SL, Rørth R, Jhund PS, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:776-785. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30249-9

28. Bertoccini L, Baroni MG. GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: new insights and opportunities for cardiovascular protection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1307:193-212. doi:10.1007/5584_2020_494

29. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al; ELIXA Investigators. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2247-2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225

30. Sheahan KH, Wahlberg EA, Gilbert MP. An overview of GLP-1 agonists and recent cardiovascular outcomes trials. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96:156-161. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-137186

31. Kim AS. Medical management for secondary stroke prevention. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2020;26:435-456. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000849

32. Smith L, Chakraborty D, Bhattacharya P, et al. Exposure to hypoglycemia and risk of stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1431:25-34. doi:10.1111/nyas.13872

33. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A 3rd, et al; . High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061894

34. Castilla-Guerra, L, Fernandez-Moreno M, Leon-Jimenez D, et al. Statins in ischemic stroke prevention: what have we learned in the post-SPARCL (The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels) decade? Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21:22. doi: 10.1007/s11940-019-0563-4

35. Bohula EA, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, et al. Prevention of stroke with the addition of ezetimibe to statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome in IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial). Circulation. 2017;136:2440-2450. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029095

36. Moritsugu KP. The 2006 report of the Surgeon General: the health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med. 20067;32:542-543. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.026

37. Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Kannel WB, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. JAMA. 1988;259:1025-1029.

38. Goldstein LB, Adams R, Alberts MJ, et al. Primary prevention of ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council: cosponsored by the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease Interdisciplinary Working Group; Cardiovascular Nursing Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Council; and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke. 2006;37:1583-1633. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000223048.70103.F1

39. Klijn CJ, Paciaroni M, Berge E, et al. Antithrombotic treatment for secondary prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic events in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack and non-valvular atrial fibrillation: A European Stroke Organisation guideline. Eur Stroke J. 2019;4:198-223. doi:10.1177/2396987319841187