User login

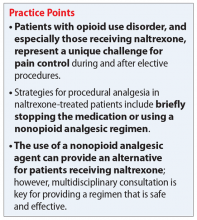

Managing procedural pain in a patient taking naltrexone

Mr. M, age 55, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with hematochezia. Mr. M states that for the past week, he has noticed blood upon wiping after a bowel movement and is worried that he might have cancer.

Mr. M has a 10-year history of opioid use disorder as diagnosed by his psychiatrist. He is presently maintained on long-acting injectable naltrexone, 380 mg IM every 4 weeks, and has not used opioids for the past 1.5 years. Mr. M is also taking simvastatin, 40 mg, for dyslipidemia, lisinopril, 5 mg, for hypertension, and cetirizine, 5 mg as needed, for seasonal allergies.

A standard workup including a physical examination and laboratory tests are performed. Mr. M’s PCP would like for him to undergo a colonoscopy to investigate the etiology of the bleeding. In consultation with both the PCP and psychiatrist, the gastroenterologist determines that the colonoscopy can be performed within 48 hours with no changes to Mr. M’s medication regimen. The gastroenterologist utilizes a nonopioid, ketorolac, 30 mg IV, for pain management during the procedure. Diverticula were identified in the lower gastrointestinal tract and are treated endoscopically. Mr. M is successfully withdrawn from sedation with no adverse events or pain and continues to be in opioid remission.

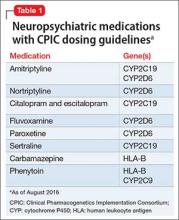

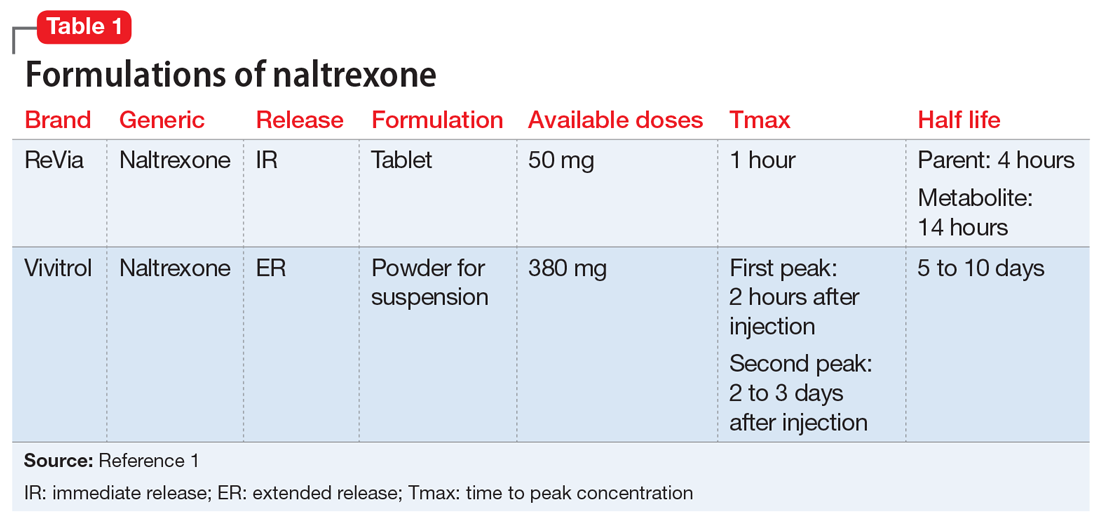

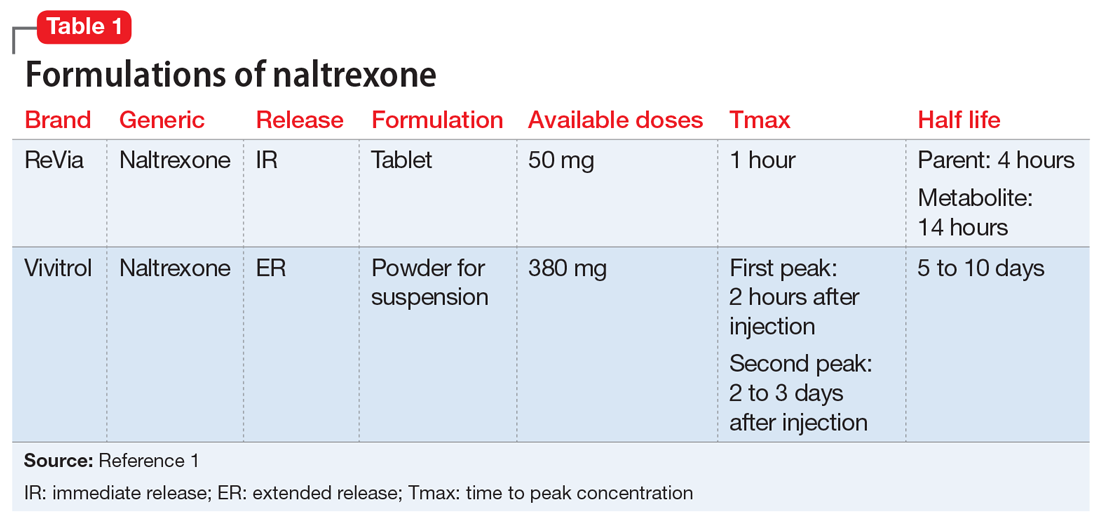

Naltrexone competitively antagonizes opioid receptors with the highest affinity for the µ-opioid receptor. It is approved for treatment of alcohol and opioid dependence following opioid detoxification.1 Its competitive inhibition at the µ-opioid receptor results in the inhibition of exogenous opioid effects. The medication is available as an orally administered tablet as well as a long-acting injection administered intramuscularly (Table 11). The long-acting injection can be useful in patients who have difficulty with adherence, because good adherence to naltrexone is required to maximize efficacy.

Due to its ability to block opioid analgesic effects, naltrexone presents a unique challenge for patients taking it who need to undergo procedures that require pain control. Pharmacologic regimens used during procedures often contain a sedative agent, such as propofol, and an opioid for analgesia. Alternative strategies are needed for patients taking naltrexone who require an opioid analgesic agent for procedures such as colonoscopies.

One strategy could be to withhold naltrexone before the procedure to ensure that the medication will not compete with the opioid agent to relieve pain. This strategy depends on the urgency of the procedure, the formulation of naltrexone being used, and patient-specific factors that may increase the risk for adverse events. For a non-urgent, elective procedure, it may be acceptable to hold oral naltrexone approximately 72 hours before the procedure. However, this is likely not a favorable approach for patients who may be at high risk for relapse or for patients who are receiving the long-acting formulation. Additionally, the use of an opioid agent intra- or post-operatively for pain may increase the risk of relapse. The use of opioids for such procedures may also be more difficult in a patient with a history of opioid abuse or dependence because he or she may have developed tolerance to opioids. Conversely, if a patient has been treated with naltrexone for an extended period, a lack of tolerance may increase the risk of respiratory depression with opioid administration due to upregulation of the opioid receptor.2

Continue to: Nonopioid analgesic agents

Nonopioid analgesic agents

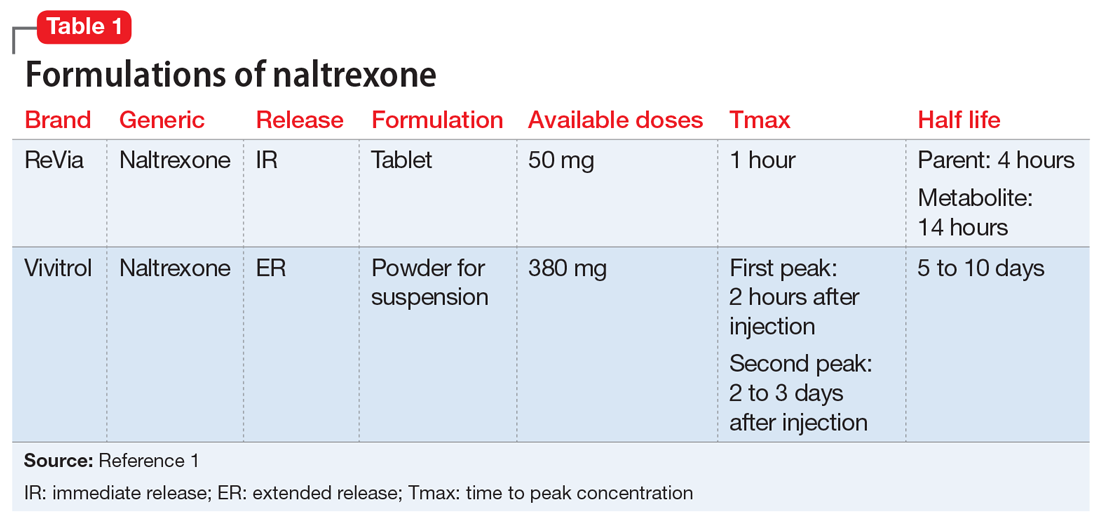

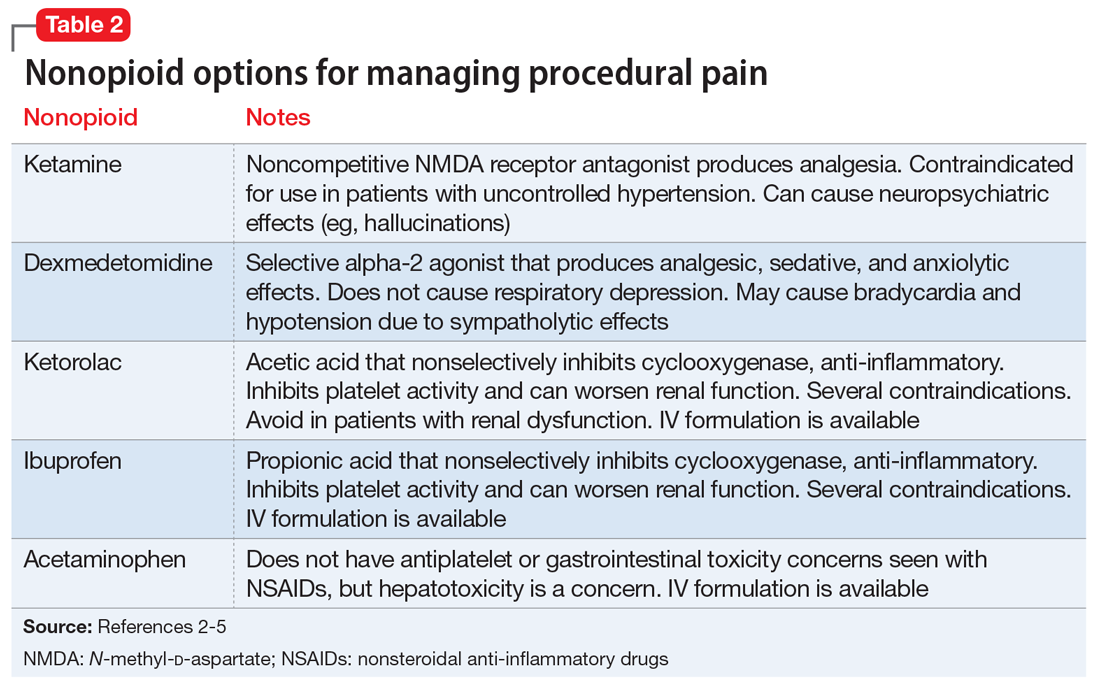

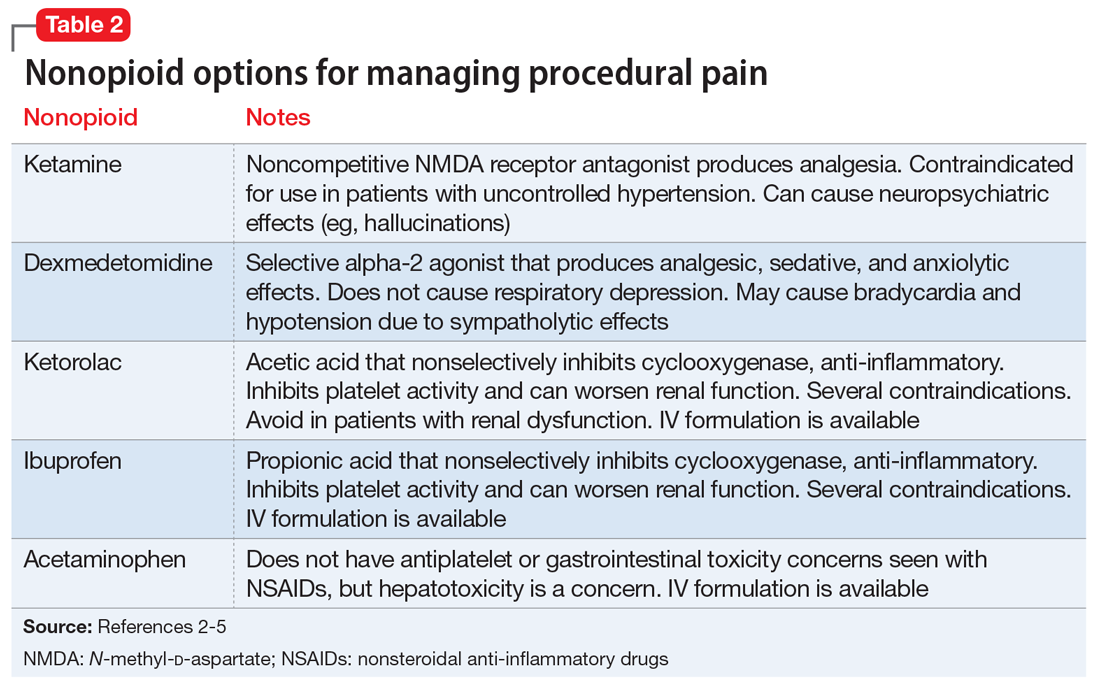

For a patient receiving naltrexone who needs to undergo a procedure, a multidisciplinary consultation between the patient’s psychiatrist and other clinicians is key for providing a regimen that is safe and effective. A nonopioid analgesic agent may be considered to avoid the problematic interactions possible in these patients (Table 23-5). Nonopioid regimens can be utilized alone or in combination, and may include the following3-5:

Ketamine is a non-competitive antagonist at the N-methyl-

Dexmedetomidine is an alpha-2 agonist that can provide sedative and analgesic effects. It can cause procedural hypotension and bradycardia, so caution is advised in patients with cardiac disease and hepatic and/or renal insufficiencies.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or ketorolac, inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes and can be considered in analgesic regimens. However, for most surgical procedures, the increased risk of bleeding due to platelet inhibition is a concern.

Continue to: Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen. Although its full mechanism of action has not been discovered, acetaminophen may also act on the cyclooxygenase pathway to produce analgesia. Compared with the oral formulation, IV acetaminophen is more expensive but may offer certain advantages, including faster plasma peak levels and lower production of acetaminophen’s toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine. Nonetheless, hepatotoxicity and overdose remain a concern.

The use of nonopioid analgesics during elective procedures that require pain control will allow continued use of an opioid antagonist such as naltrexone, while minimizing the risk for withdrawal or relapse. Their use must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to ensure maximum safety and efficacy for each patient from both a medical and psychiatric standpoint. Overall, with the proper expertise and consultation, nonopioid pain regimens represent a reasonable alternative to opiates for patients who take naltrexone.

Related Resources

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Standards guidelines and related resources. https://www.asahq.org/quality-and-practice-management/standards-guidelines-and-related-resources-search.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Clinical resources. https://www.asam.org/resources/guidelines-and-consensus-documents.

Drug Brand Names

Acetaminophen • Tylenol

Cetirizine • Zyrtec

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Ibuprofen • Caldolor (IV), Motrin (oral)

Ketamine • Ketalar

Ketorolac • Toradol

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Propofol • Diprivan

Simvastatin • Juvisync, Simcor

1. Vivitrol [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; 2015.

2. Yoburn BC, Duttaroy A, Shah S, et al. Opioid antagonist-induced receptor upregulation: effects of concurrent agonist administration. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33(2):237-240.

3. Vadivelu N, Chang D, Lumermann L, et al. Management of patients on abuse-deterrent opioids in the ambulatory surgery setting. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21(2):10.

4. Koh W, Nguyen KP, Jahr JS. Intravenous non-opioid analgesia for peri- and postoperative pain management: a scientific review of intravenous acetaminophen and ibuprofen. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015;68(1):3-12.

5. Kaye AD, Cornett EM, Helander E, et al. An update on nonopioids: intravenous or oral analgesics for perioperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(2):e55-e71.

Mr. M, age 55, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with hematochezia. Mr. M states that for the past week, he has noticed blood upon wiping after a bowel movement and is worried that he might have cancer.

Mr. M has a 10-year history of opioid use disorder as diagnosed by his psychiatrist. He is presently maintained on long-acting injectable naltrexone, 380 mg IM every 4 weeks, and has not used opioids for the past 1.5 years. Mr. M is also taking simvastatin, 40 mg, for dyslipidemia, lisinopril, 5 mg, for hypertension, and cetirizine, 5 mg as needed, for seasonal allergies.

A standard workup including a physical examination and laboratory tests are performed. Mr. M’s PCP would like for him to undergo a colonoscopy to investigate the etiology of the bleeding. In consultation with both the PCP and psychiatrist, the gastroenterologist determines that the colonoscopy can be performed within 48 hours with no changes to Mr. M’s medication regimen. The gastroenterologist utilizes a nonopioid, ketorolac, 30 mg IV, for pain management during the procedure. Diverticula were identified in the lower gastrointestinal tract and are treated endoscopically. Mr. M is successfully withdrawn from sedation with no adverse events or pain and continues to be in opioid remission.

Naltrexone competitively antagonizes opioid receptors with the highest affinity for the µ-opioid receptor. It is approved for treatment of alcohol and opioid dependence following opioid detoxification.1 Its competitive inhibition at the µ-opioid receptor results in the inhibition of exogenous opioid effects. The medication is available as an orally administered tablet as well as a long-acting injection administered intramuscularly (Table 11). The long-acting injection can be useful in patients who have difficulty with adherence, because good adherence to naltrexone is required to maximize efficacy.

Due to its ability to block opioid analgesic effects, naltrexone presents a unique challenge for patients taking it who need to undergo procedures that require pain control. Pharmacologic regimens used during procedures often contain a sedative agent, such as propofol, and an opioid for analgesia. Alternative strategies are needed for patients taking naltrexone who require an opioid analgesic agent for procedures such as colonoscopies.

One strategy could be to withhold naltrexone before the procedure to ensure that the medication will not compete with the opioid agent to relieve pain. This strategy depends on the urgency of the procedure, the formulation of naltrexone being used, and patient-specific factors that may increase the risk for adverse events. For a non-urgent, elective procedure, it may be acceptable to hold oral naltrexone approximately 72 hours before the procedure. However, this is likely not a favorable approach for patients who may be at high risk for relapse or for patients who are receiving the long-acting formulation. Additionally, the use of an opioid agent intra- or post-operatively for pain may increase the risk of relapse. The use of opioids for such procedures may also be more difficult in a patient with a history of opioid abuse or dependence because he or she may have developed tolerance to opioids. Conversely, if a patient has been treated with naltrexone for an extended period, a lack of tolerance may increase the risk of respiratory depression with opioid administration due to upregulation of the opioid receptor.2

Continue to: Nonopioid analgesic agents

Nonopioid analgesic agents

For a patient receiving naltrexone who needs to undergo a procedure, a multidisciplinary consultation between the patient’s psychiatrist and other clinicians is key for providing a regimen that is safe and effective. A nonopioid analgesic agent may be considered to avoid the problematic interactions possible in these patients (Table 23-5). Nonopioid regimens can be utilized alone or in combination, and may include the following3-5:

Ketamine is a non-competitive antagonist at the N-methyl-

Dexmedetomidine is an alpha-2 agonist that can provide sedative and analgesic effects. It can cause procedural hypotension and bradycardia, so caution is advised in patients with cardiac disease and hepatic and/or renal insufficiencies.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or ketorolac, inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes and can be considered in analgesic regimens. However, for most surgical procedures, the increased risk of bleeding due to platelet inhibition is a concern.

Continue to: Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen. Although its full mechanism of action has not been discovered, acetaminophen may also act on the cyclooxygenase pathway to produce analgesia. Compared with the oral formulation, IV acetaminophen is more expensive but may offer certain advantages, including faster plasma peak levels and lower production of acetaminophen’s toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine. Nonetheless, hepatotoxicity and overdose remain a concern.

The use of nonopioid analgesics during elective procedures that require pain control will allow continued use of an opioid antagonist such as naltrexone, while minimizing the risk for withdrawal or relapse. Their use must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to ensure maximum safety and efficacy for each patient from both a medical and psychiatric standpoint. Overall, with the proper expertise and consultation, nonopioid pain regimens represent a reasonable alternative to opiates for patients who take naltrexone.

Related Resources

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Standards guidelines and related resources. https://www.asahq.org/quality-and-practice-management/standards-guidelines-and-related-resources-search.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Clinical resources. https://www.asam.org/resources/guidelines-and-consensus-documents.

Drug Brand Names

Acetaminophen • Tylenol

Cetirizine • Zyrtec

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Ibuprofen • Caldolor (IV), Motrin (oral)

Ketamine • Ketalar

Ketorolac • Toradol

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Propofol • Diprivan

Simvastatin • Juvisync, Simcor

Mr. M, age 55, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with hematochezia. Mr. M states that for the past week, he has noticed blood upon wiping after a bowel movement and is worried that he might have cancer.

Mr. M has a 10-year history of opioid use disorder as diagnosed by his psychiatrist. He is presently maintained on long-acting injectable naltrexone, 380 mg IM every 4 weeks, and has not used opioids for the past 1.5 years. Mr. M is also taking simvastatin, 40 mg, for dyslipidemia, lisinopril, 5 mg, for hypertension, and cetirizine, 5 mg as needed, for seasonal allergies.

A standard workup including a physical examination and laboratory tests are performed. Mr. M’s PCP would like for him to undergo a colonoscopy to investigate the etiology of the bleeding. In consultation with both the PCP and psychiatrist, the gastroenterologist determines that the colonoscopy can be performed within 48 hours with no changes to Mr. M’s medication regimen. The gastroenterologist utilizes a nonopioid, ketorolac, 30 mg IV, for pain management during the procedure. Diverticula were identified in the lower gastrointestinal tract and are treated endoscopically. Mr. M is successfully withdrawn from sedation with no adverse events or pain and continues to be in opioid remission.

Naltrexone competitively antagonizes opioid receptors with the highest affinity for the µ-opioid receptor. It is approved for treatment of alcohol and opioid dependence following opioid detoxification.1 Its competitive inhibition at the µ-opioid receptor results in the inhibition of exogenous opioid effects. The medication is available as an orally administered tablet as well as a long-acting injection administered intramuscularly (Table 11). The long-acting injection can be useful in patients who have difficulty with adherence, because good adherence to naltrexone is required to maximize efficacy.

Due to its ability to block opioid analgesic effects, naltrexone presents a unique challenge for patients taking it who need to undergo procedures that require pain control. Pharmacologic regimens used during procedures often contain a sedative agent, such as propofol, and an opioid for analgesia. Alternative strategies are needed for patients taking naltrexone who require an opioid analgesic agent for procedures such as colonoscopies.

One strategy could be to withhold naltrexone before the procedure to ensure that the medication will not compete with the opioid agent to relieve pain. This strategy depends on the urgency of the procedure, the formulation of naltrexone being used, and patient-specific factors that may increase the risk for adverse events. For a non-urgent, elective procedure, it may be acceptable to hold oral naltrexone approximately 72 hours before the procedure. However, this is likely not a favorable approach for patients who may be at high risk for relapse or for patients who are receiving the long-acting formulation. Additionally, the use of an opioid agent intra- or post-operatively for pain may increase the risk of relapse. The use of opioids for such procedures may also be more difficult in a patient with a history of opioid abuse or dependence because he or she may have developed tolerance to opioids. Conversely, if a patient has been treated with naltrexone for an extended period, a lack of tolerance may increase the risk of respiratory depression with opioid administration due to upregulation of the opioid receptor.2

Continue to: Nonopioid analgesic agents

Nonopioid analgesic agents

For a patient receiving naltrexone who needs to undergo a procedure, a multidisciplinary consultation between the patient’s psychiatrist and other clinicians is key for providing a regimen that is safe and effective. A nonopioid analgesic agent may be considered to avoid the problematic interactions possible in these patients (Table 23-5). Nonopioid regimens can be utilized alone or in combination, and may include the following3-5:

Ketamine is a non-competitive antagonist at the N-methyl-

Dexmedetomidine is an alpha-2 agonist that can provide sedative and analgesic effects. It can cause procedural hypotension and bradycardia, so caution is advised in patients with cardiac disease and hepatic and/or renal insufficiencies.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or ketorolac, inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes and can be considered in analgesic regimens. However, for most surgical procedures, the increased risk of bleeding due to platelet inhibition is a concern.

Continue to: Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen. Although its full mechanism of action has not been discovered, acetaminophen may also act on the cyclooxygenase pathway to produce analgesia. Compared with the oral formulation, IV acetaminophen is more expensive but may offer certain advantages, including faster plasma peak levels and lower production of acetaminophen’s toxic metabolite, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine. Nonetheless, hepatotoxicity and overdose remain a concern.

The use of nonopioid analgesics during elective procedures that require pain control will allow continued use of an opioid antagonist such as naltrexone, while minimizing the risk for withdrawal or relapse. Their use must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis to ensure maximum safety and efficacy for each patient from both a medical and psychiatric standpoint. Overall, with the proper expertise and consultation, nonopioid pain regimens represent a reasonable alternative to opiates for patients who take naltrexone.

Related Resources

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Standards guidelines and related resources. https://www.asahq.org/quality-and-practice-management/standards-guidelines-and-related-resources-search.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. Clinical resources. https://www.asam.org/resources/guidelines-and-consensus-documents.

Drug Brand Names

Acetaminophen • Tylenol

Cetirizine • Zyrtec

Dexmedetomidine • Precedex

Ibuprofen • Caldolor (IV), Motrin (oral)

Ketamine • Ketalar

Ketorolac • Toradol

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Propofol • Diprivan

Simvastatin • Juvisync, Simcor

1. Vivitrol [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; 2015.

2. Yoburn BC, Duttaroy A, Shah S, et al. Opioid antagonist-induced receptor upregulation: effects of concurrent agonist administration. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33(2):237-240.

3. Vadivelu N, Chang D, Lumermann L, et al. Management of patients on abuse-deterrent opioids in the ambulatory surgery setting. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21(2):10.

4. Koh W, Nguyen KP, Jahr JS. Intravenous non-opioid analgesia for peri- and postoperative pain management: a scientific review of intravenous acetaminophen and ibuprofen. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015;68(1):3-12.

5. Kaye AD, Cornett EM, Helander E, et al. An update on nonopioids: intravenous or oral analgesics for perioperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(2):e55-e71.

1. Vivitrol [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; 2015.

2. Yoburn BC, Duttaroy A, Shah S, et al. Opioid antagonist-induced receptor upregulation: effects of concurrent agonist administration. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33(2):237-240.

3. Vadivelu N, Chang D, Lumermann L, et al. Management of patients on abuse-deterrent opioids in the ambulatory surgery setting. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21(2):10.

4. Koh W, Nguyen KP, Jahr JS. Intravenous non-opioid analgesia for peri- and postoperative pain management: a scientific review of intravenous acetaminophen and ibuprofen. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015;68(1):3-12.

5. Kaye AD, Cornett EM, Helander E, et al. An update on nonopioids: intravenous or oral analgesics for perioperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35(2):e55-e71.

Where to find guidance on using pharmacogenomics in psychiatric practice

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

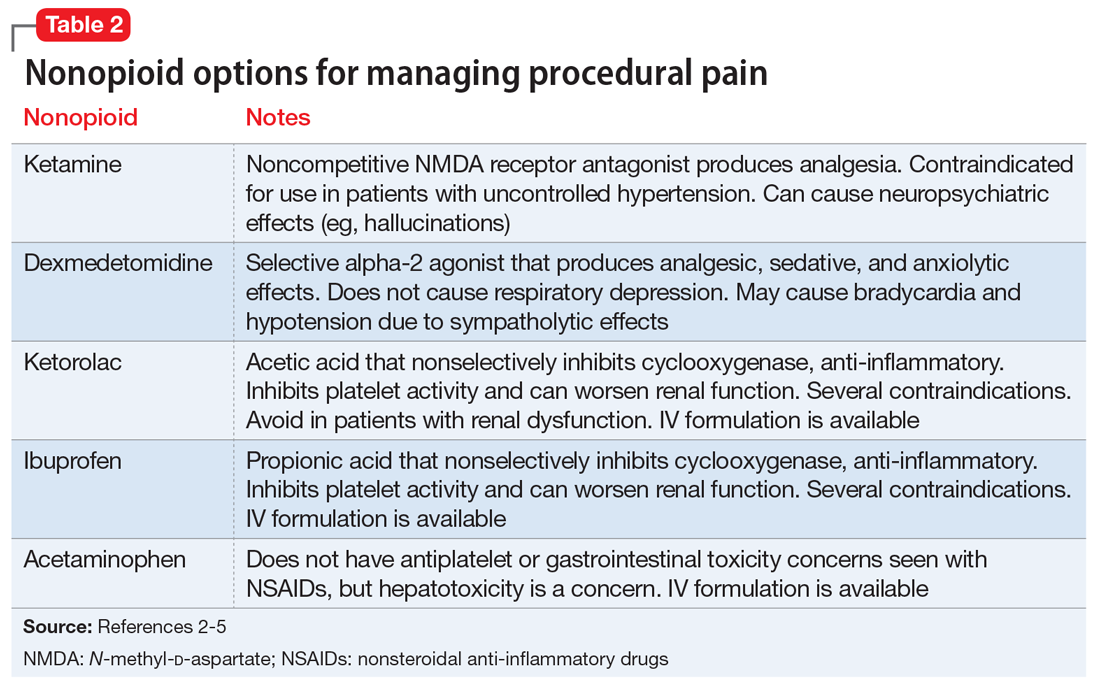

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

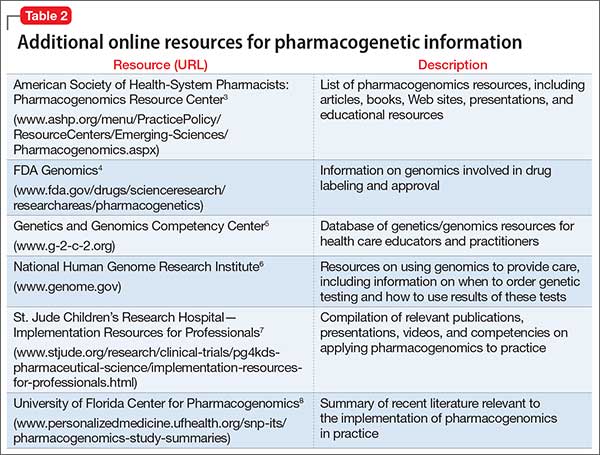

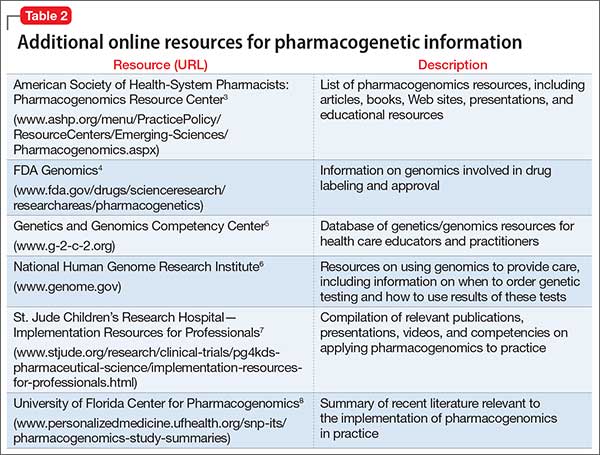

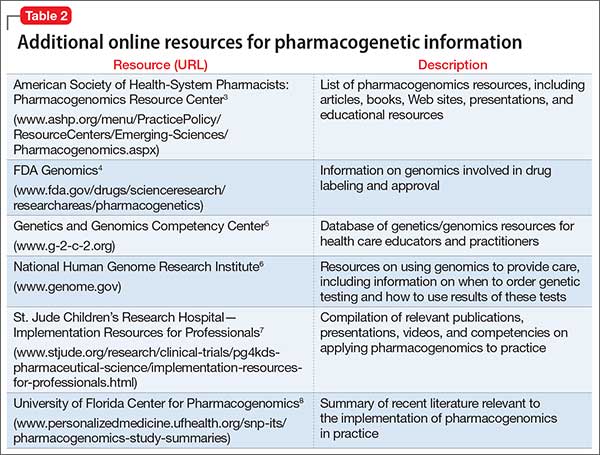

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

Sildenafil for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in women

- Sexual dysfunction can arise from environmental, social, medical, or drug effects and requires a multifaceted approach to treatment.

- When possible, take a baseline sexual dysfunction measurement to assess if selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use is correlated with onset or worsening of sexual dysfunction.

- Nonpharmacologic options should be considered before and during pharmacotherapy.

- Sildenafil may be useful for treating anorgasmia in women taking serotonergic antidepressants.

- Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are not FDA-approved for sexual dysfunction in women.

Mrs. L, age 27, has a history of major depressive disorder with symptoms of anxiety. She was managed successfully for 2 years with bupropion XL, 300 mg/d, but was switched to venlafaxine, titrated to 225 mg/d, after she developed seizures secondary to a head injury sustained in a car accident. After the switch, Mrs. L’s mood deteriorated and she was hospitalized. Since then, she’s received several medication trials, including paroxetine, 30 mg/d, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) nortriptyline, 75 mg/d, but she could not tolerate these medications because of severe xerostomia.

After taking sertraline, 150 mg/d, for 8 weeks, Mrs. L improves and has a Patient Health Questionnaire score of 6, indicating mild depression. Her initial complaints of diarrhea and nausea have resolved, but Mrs. L now reports that she and her husband are having marital difficulties because she cannot achieve orgasm during sexual intercourse. She did not have this problem when she was taking bupropion. Her husband occasionally takes the phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor sildenafil before intercourse, and Mrs. L asks you if this medication will help her achieve orgasm.

DSM-IV-TR defines sexual dysfunction as disturbances in sexual desire and/or in the sexual response cycle (excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution) that result in marked distress and interpersonal difficulty.1 Sexual dysfunction can occur with the use of any antidepressant with serotonergic activity; it affects an estimated 50% to 70% of patients who take SSRIs.2 Sexual dysfunction can occur with all SSRIs; however, higher rates of sexual dysfunction are found with citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline.3 Studies have suggested there may be a dose-side effect relationship with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.4

Several factors can increase a patient’s risk of sexual dysfunction and should be considered before prescribing an antidepressant or when a patient presents with new or worsening sexual dysfunction (Table 1).5 In general, nonserotonergic agents such as bupropion, mirtazapine, and nefazodone are associated with lower rates of sexual dysfunction. The pharmacology of these agents explains their decreased propensity to cause sexual dysfunction. These agents increase levels of dopamine in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system either by blocking reuptake (bupropion) or antagonizing the serotonin subtype-2 receptor and facilitating disinhibition of decreased dopamine downstream (nefazodone and mirtazapine).

Table 1

Risk factors for sexual dysfunction

| Sex | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Women | History of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, physical inactivity |

| Men | Severe hyperprolactinemia, smoking |

| Both sexes | Poor to fair health, genitourinary disease, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, increasing age, psychiatric disorders, relationship difficulties |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

One option for treating antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction in women is PDE5 inhibitors, which are used to treat erectile dysfunction (ED). These medications ameliorate ED by inhibiting degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate by PDE5, which increases blood flow to the penis during sexual stimulation. Although these medications are not FDA-approved for treating sexual dysfunction in women, adjunctive PDE5 inhibitor treatment may be beneficial for sexual dysfunction in females because similar mediators, such as nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate, involved in the nonadrenergic-noncholinergic signaling that controls sexual stimulation in men also are found in female genital tissue.6

When treating a woman with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, consider nonpharmacologic treatments both before and during pharmacotherapy (Table 2).7,8 See Table 3 for a comparison of pharmacokinetics, side effects, and drug interactions of the 4 FDA-approved PDE5 inhibitors—avanafil, sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil.

Table 2

Management strategies for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction

| Intervention | Comments |

|---|---|

| Nonpharmacologic | |

| Lifestyle modifications | Encourage healthy eating, weight loss, smoking cessation, substance abuse treatment, or minimizing alcohol intake to improve patient self-image and overall health |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy | Patients can identify coping strategies for reducing symptom severity and preventing worsening sexual dysfunction |

| Sex therapy | May benefit patients with relationship difficulties |

| ‘Watch and wait’ | Spontaneous resolving (or ‘adaptation’) of sexual dysfunction with antidepressants can take ≥6 months. Studies have found adaptation rates generally are low (~10%) |

| Pharmacologic | |

| Drug holiday | May be an option for patients taking antidepressants with shorter half-lives and patients taking lower doses. Be cautious of empowering patients to stop their own medications as needed |

| Dosage reduction | Serotonergic antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction may be related to dose. Little research has been conducted on this method and the patient’s clinical status must be considered |

| Dose timing | Instructing a patient to take the antidepressant after his or her usual time of sexual activity (eg, patients who engage in sexual activity at night should take the antidepressant before falling asleep). This may allow the drug level to be lowest during sexual activity |

| Switching medications | Case reports, retrospective studies, and RCTs suggest switching to a different antidepressant with less serotonergic activity may be appropriate, particularly if the patient has not responded to the current antidepressant |

| Adjunctive therapy | RCTs support adjunctive bupropion (≥300 mg/d) or olanzapine (5 mg/d) as treatment for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in women Studies have found no improvement in sexual functioning with adjunctive buspirone, granisetron, amantadine, mirtazapine, yohimbine, ephedrine, or ginkgo biloba in women |

| RCTs: randomized controlled trials; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor Source: Reference 7,8 | |

Table 3

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors: A comparison

| Medication | Dose rangea | Pharmacokinetics | Side effects | Significant drug interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avanafil | 50 to 200 mg, 30 minutes before sexual activity | Bioavailability: N/A (high-fat meal delays Tmax by 60 minutes and reduces Cmax by 24% to 39%; clinically insignificant) Half life: 5 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, nasal congestion, nasopharyngitis, backache | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased avanafil levels) Contraindicated within 12 hours of nitrate use (eg, nitroglycerin) |

| Sildenafil | 25 to 100 mg, 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity | Bioavailability: 41% (food/high-fat meal delays Tmax by 60 minutes and reduces Cmax by 29%) Half life: 4 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, erythema, indigestion, insomnia, visual disturbances (blue vision) | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased sildenafil levels) Contraindicated within 24 hours of nitrate use |

| Tadalafil | 10 to 20 mg, 30 minutes before sexual activity | Bioavailability: N/A (not affected by food) Half life: 17.5 hours (duration of action up to 36 hours) Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, indigestion, nasal congestion, dizziness, myalgia, and back pain | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased tadalafil levels) Contraindicated within 48 hours of nitrate use |

| Vardenafil | 5 to 20 mg, 30 minutes to 2 hours before sexual activity | Bioavailability: 15% for film-coated tablet (high-fat meal reduces Cmax by 18% to 50%) Half life: 4 to 5 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, indigestion, nasal congestion, dizziness, visual disturbances (blue vision) | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased vardenafil levels) Contraindicated within 24 hours of nitrate use |

| aTypical dose range for treatment of erectile dysfunction Cmax: maximum concentration; CYP: cytochrome P450; Tmax: time to maximum concentration Source: Micromedex® Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Healthcare. Accessed October 10, 2012 | ||||

Limited evidence for sildenafil

Case reports, a few small open-label trials, and 1 prospective, randomized controlled trial (RCT) have evaluated sildenafil as an adjunctive treatment for serotonergic antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in women.6,9 Nurnberg et al6 examined the efficacy of adjunctive sildenafil in women with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. This 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, RCT used a flexible dose (50 or 100 mg), intention-to-treat design to assess the effect of sildenafil on 98 premenopausal women whose depression was in remission. Ten patients were taking the serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitor venlafaxine, 1 was taking the TCA clomipramine, and 87 were receiving an SSRI. Patients were instructed to take sildenafil or placebo 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity. The primary outcome was mean change from baseline on the Clinical Global Impression-Sexual Function (CGI-SF) scale.

Women taking sildenafil showed significant improvement compared with those taking placebo, with a treatment difference between groups of 0.8 (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.0; =.001). Additionally, 23% of sildenafil-treated patients reported no improvement with the intervention, compared with 73% of patients receiving placebo. Secondary outcomes using 3 validated scales that evaluated specific phases of sexual function found that patients’ orgasmic function significantly benefited from sildenafil treatment, while desire, arousal, and overall satisfaction were not significantly different.

Although these findings seem to support sildenafil for treating serotonergic antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in women, the study had a relatively small treatment effect in a well-defined patient population; therefore, replication in future trials and different patient populations is warranted. Overall, sildenafil was well tolerated, despite patient reports of headaches, flushing, visual disturbances, dyspepsia, nasal congestion, and palpitations. Finally, cost vs benefit should be considered; PDE5 inhibitors may not be covered by insurance or may require prior authorization.

CASE CONTINUED: Symptoms resolve

Bupropion is not an appropriate choice for Mrs. L because of her seizure risk. Mirtazapine is ruled out because in the past she experienced excessive somnolence that impaired her ability to function. You are not comfortable prescribing nefazodone because of its risk of hepatotoxicity or suggesting that Mrs. L take a “drug holiday” (stop taking any antidepressants for a short period) because of the risk of depressive relapse. You suggest that Mrs. L continue to take sertraline because sometimes antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction resolves after ≥6 months of treatment with the same agent, but she is adamant that her relationship with her husband will deteriorate if she waits that long. She also declines cognitive-behavioral therapy because her job doesn’t allow the time or flexibility to commit to the sessions.

You prescribe sildenafil, 50 mg, and instruct Mrs. L to take 1 tablet 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity. This treatment improves her ability to achieve orgasm. She tolerates the drug well and after 8 weeks of treatment her CGI-SF score improves from 6 at baseline, indicating extreme dysfunction, to 2, indicating normal function. Ten months into her sertraline treatment, Mrs. L discovers she no longer requires sildenafil to achieve orgasm.

Related Resources

- Nurnberg HG. An evidence-based review updating the various treatment and management approaches to serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated sexual dysfunction. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008;44(2):147-168.

- NIH Medline Plus. Sexual problems in women. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/sexualproblemsinwomen.html.

- Sturpe DA, Mertens MK, Scoville C. What are the treatment options for SSRI-related sexual dysfunction? J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8):681.

Drug Brand Names

- Amantadine • Symadine, Symmetrel

- Avanafil • Stendra

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Granisetron • Kytril

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nitroglycerin • Nitrostat

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Tadalafil • Cialis

- Vardenafil • Levitra

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Burghardt receives grant or research support from the University of Michigan Depression Center.

Ms. Gardner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, et al. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 3):10-21.

3. Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):259-266.

4. Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):357-366.

5. Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, et al. Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):35-39.

6. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(4):395-404.

7. Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Hawton K. Strategies for managing antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2005;88(3):241-254.

8. Balon R. SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1504-1509.

9. Brown DA, Kyle JA, Ferrill MJ. Assessing the clinical efficacy of sildenafil for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(7):1275-1285.

- Sexual dysfunction can arise from environmental, social, medical, or drug effects and requires a multifaceted approach to treatment.

- When possible, take a baseline sexual dysfunction measurement to assess if selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use is correlated with onset or worsening of sexual dysfunction.

- Nonpharmacologic options should be considered before and during pharmacotherapy.

- Sildenafil may be useful for treating anorgasmia in women taking serotonergic antidepressants.

- Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are not FDA-approved for sexual dysfunction in women.

Mrs. L, age 27, has a history of major depressive disorder with symptoms of anxiety. She was managed successfully for 2 years with bupropion XL, 300 mg/d, but was switched to venlafaxine, titrated to 225 mg/d, after she developed seizures secondary to a head injury sustained in a car accident. After the switch, Mrs. L’s mood deteriorated and she was hospitalized. Since then, she’s received several medication trials, including paroxetine, 30 mg/d, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) nortriptyline, 75 mg/d, but she could not tolerate these medications because of severe xerostomia.

After taking sertraline, 150 mg/d, for 8 weeks, Mrs. L improves and has a Patient Health Questionnaire score of 6, indicating mild depression. Her initial complaints of diarrhea and nausea have resolved, but Mrs. L now reports that she and her husband are having marital difficulties because she cannot achieve orgasm during sexual intercourse. She did not have this problem when she was taking bupropion. Her husband occasionally takes the phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor sildenafil before intercourse, and Mrs. L asks you if this medication will help her achieve orgasm.

DSM-IV-TR defines sexual dysfunction as disturbances in sexual desire and/or in the sexual response cycle (excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution) that result in marked distress and interpersonal difficulty.1 Sexual dysfunction can occur with the use of any antidepressant with serotonergic activity; it affects an estimated 50% to 70% of patients who take SSRIs.2 Sexual dysfunction can occur with all SSRIs; however, higher rates of sexual dysfunction are found with citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline.3 Studies have suggested there may be a dose-side effect relationship with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.4

Several factors can increase a patient’s risk of sexual dysfunction and should be considered before prescribing an antidepressant or when a patient presents with new or worsening sexual dysfunction (Table 1).5 In general, nonserotonergic agents such as bupropion, mirtazapine, and nefazodone are associated with lower rates of sexual dysfunction. The pharmacology of these agents explains their decreased propensity to cause sexual dysfunction. These agents increase levels of dopamine in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system either by blocking reuptake (bupropion) or antagonizing the serotonin subtype-2 receptor and facilitating disinhibition of decreased dopamine downstream (nefazodone and mirtazapine).

Table 1

Risk factors for sexual dysfunction

| Sex | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Women | History of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, physical inactivity |

| Men | Severe hyperprolactinemia, smoking |

| Both sexes | Poor to fair health, genitourinary disease, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, increasing age, psychiatric disorders, relationship difficulties |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

One option for treating antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction in women is PDE5 inhibitors, which are used to treat erectile dysfunction (ED). These medications ameliorate ED by inhibiting degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate by PDE5, which increases blood flow to the penis during sexual stimulation. Although these medications are not FDA-approved for treating sexual dysfunction in women, adjunctive PDE5 inhibitor treatment may be beneficial for sexual dysfunction in females because similar mediators, such as nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate, involved in the nonadrenergic-noncholinergic signaling that controls sexual stimulation in men also are found in female genital tissue.6

When treating a woman with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, consider nonpharmacologic treatments both before and during pharmacotherapy (Table 2).7,8 See Table 3 for a comparison of pharmacokinetics, side effects, and drug interactions of the 4 FDA-approved PDE5 inhibitors—avanafil, sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil.

Table 2

Management strategies for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction

| Intervention | Comments |

|---|---|

| Nonpharmacologic | |

| Lifestyle modifications | Encourage healthy eating, weight loss, smoking cessation, substance abuse treatment, or minimizing alcohol intake to improve patient self-image and overall health |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy | Patients can identify coping strategies for reducing symptom severity and preventing worsening sexual dysfunction |

| Sex therapy | May benefit patients with relationship difficulties |

| ‘Watch and wait’ | Spontaneous resolving (or ‘adaptation’) of sexual dysfunction with antidepressants can take ≥6 months. Studies have found adaptation rates generally are low (~10%) |

| Pharmacologic | |

| Drug holiday | May be an option for patients taking antidepressants with shorter half-lives and patients taking lower doses. Be cautious of empowering patients to stop their own medications as needed |

| Dosage reduction | Serotonergic antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction may be related to dose. Little research has been conducted on this method and the patient’s clinical status must be considered |

| Dose timing | Instructing a patient to take the antidepressant after his or her usual time of sexual activity (eg, patients who engage in sexual activity at night should take the antidepressant before falling asleep). This may allow the drug level to be lowest during sexual activity |

| Switching medications | Case reports, retrospective studies, and RCTs suggest switching to a different antidepressant with less serotonergic activity may be appropriate, particularly if the patient has not responded to the current antidepressant |

| Adjunctive therapy | RCTs support adjunctive bupropion (≥300 mg/d) or olanzapine (5 mg/d) as treatment for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in women Studies have found no improvement in sexual functioning with adjunctive buspirone, granisetron, amantadine, mirtazapine, yohimbine, ephedrine, or ginkgo biloba in women |

| RCTs: randomized controlled trials; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor Source: Reference 7,8 | |

Table 3

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors: A comparison

| Medication | Dose rangea | Pharmacokinetics | Side effects | Significant drug interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avanafil | 50 to 200 mg, 30 minutes before sexual activity | Bioavailability: N/A (high-fat meal delays Tmax by 60 minutes and reduces Cmax by 24% to 39%; clinically insignificant) Half life: 5 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, nasal congestion, nasopharyngitis, backache | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased avanafil levels) Contraindicated within 12 hours of nitrate use (eg, nitroglycerin) |

| Sildenafil | 25 to 100 mg, 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity | Bioavailability: 41% (food/high-fat meal delays Tmax by 60 minutes and reduces Cmax by 29%) Half life: 4 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, erythema, indigestion, insomnia, visual disturbances (blue vision) | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased sildenafil levels) Contraindicated within 24 hours of nitrate use |

| Tadalafil | 10 to 20 mg, 30 minutes before sexual activity | Bioavailability: N/A (not affected by food) Half life: 17.5 hours (duration of action up to 36 hours) Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, indigestion, nasal congestion, dizziness, myalgia, and back pain | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased tadalafil levels) Contraindicated within 48 hours of nitrate use |

| Vardenafil | 5 to 20 mg, 30 minutes to 2 hours before sexual activity | Bioavailability: 15% for film-coated tablet (high-fat meal reduces Cmax by 18% to 50%) Half life: 4 to 5 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, indigestion, nasal congestion, dizziness, visual disturbances (blue vision) | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased vardenafil levels) Contraindicated within 24 hours of nitrate use |

| aTypical dose range for treatment of erectile dysfunction Cmax: maximum concentration; CYP: cytochrome P450; Tmax: time to maximum concentration Source: Micromedex® Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Healthcare. Accessed October 10, 2012 | ||||

Limited evidence for sildenafil

Case reports, a few small open-label trials, and 1 prospective, randomized controlled trial (RCT) have evaluated sildenafil as an adjunctive treatment for serotonergic antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in women.6,9 Nurnberg et al6 examined the efficacy of adjunctive sildenafil in women with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. This 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, RCT used a flexible dose (50 or 100 mg), intention-to-treat design to assess the effect of sildenafil on 98 premenopausal women whose depression was in remission. Ten patients were taking the serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitor venlafaxine, 1 was taking the TCA clomipramine, and 87 were receiving an SSRI. Patients were instructed to take sildenafil or placebo 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity. The primary outcome was mean change from baseline on the Clinical Global Impression-Sexual Function (CGI-SF) scale.

Women taking sildenafil showed significant improvement compared with those taking placebo, with a treatment difference between groups of 0.8 (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.0; =.001). Additionally, 23% of sildenafil-treated patients reported no improvement with the intervention, compared with 73% of patients receiving placebo. Secondary outcomes using 3 validated scales that evaluated specific phases of sexual function found that patients’ orgasmic function significantly benefited from sildenafil treatment, while desire, arousal, and overall satisfaction were not significantly different.

Although these findings seem to support sildenafil for treating serotonergic antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in women, the study had a relatively small treatment effect in a well-defined patient population; therefore, replication in future trials and different patient populations is warranted. Overall, sildenafil was well tolerated, despite patient reports of headaches, flushing, visual disturbances, dyspepsia, nasal congestion, and palpitations. Finally, cost vs benefit should be considered; PDE5 inhibitors may not be covered by insurance or may require prior authorization.

CASE CONTINUED: Symptoms resolve

Bupropion is not an appropriate choice for Mrs. L because of her seizure risk. Mirtazapine is ruled out because in the past she experienced excessive somnolence that impaired her ability to function. You are not comfortable prescribing nefazodone because of its risk of hepatotoxicity or suggesting that Mrs. L take a “drug holiday” (stop taking any antidepressants for a short period) because of the risk of depressive relapse. You suggest that Mrs. L continue to take sertraline because sometimes antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction resolves after ≥6 months of treatment with the same agent, but she is adamant that her relationship with her husband will deteriorate if she waits that long. She also declines cognitive-behavioral therapy because her job doesn’t allow the time or flexibility to commit to the sessions.

You prescribe sildenafil, 50 mg, and instruct Mrs. L to take 1 tablet 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity. This treatment improves her ability to achieve orgasm. She tolerates the drug well and after 8 weeks of treatment her CGI-SF score improves from 6 at baseline, indicating extreme dysfunction, to 2, indicating normal function. Ten months into her sertraline treatment, Mrs. L discovers she no longer requires sildenafil to achieve orgasm.

Related Resources

- Nurnberg HG. An evidence-based review updating the various treatment and management approaches to serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated sexual dysfunction. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008;44(2):147-168.

- NIH Medline Plus. Sexual problems in women. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/sexualproblemsinwomen.html.

- Sturpe DA, Mertens MK, Scoville C. What are the treatment options for SSRI-related sexual dysfunction? J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8):681.

Drug Brand Names

- Amantadine • Symadine, Symmetrel

- Avanafil • Stendra

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Granisetron • Kytril

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nitroglycerin • Nitrostat

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Tadalafil • Cialis

- Vardenafil • Levitra

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Burghardt receives grant or research support from the University of Michigan Depression Center.

Ms. Gardner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

- Sexual dysfunction can arise from environmental, social, medical, or drug effects and requires a multifaceted approach to treatment.

- When possible, take a baseline sexual dysfunction measurement to assess if selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use is correlated with onset or worsening of sexual dysfunction.

- Nonpharmacologic options should be considered before and during pharmacotherapy.

- Sildenafil may be useful for treating anorgasmia in women taking serotonergic antidepressants.

- Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are not FDA-approved for sexual dysfunction in women.

Mrs. L, age 27, has a history of major depressive disorder with symptoms of anxiety. She was managed successfully for 2 years with bupropion XL, 300 mg/d, but was switched to venlafaxine, titrated to 225 mg/d, after she developed seizures secondary to a head injury sustained in a car accident. After the switch, Mrs. L’s mood deteriorated and she was hospitalized. Since then, she’s received several medication trials, including paroxetine, 30 mg/d, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) nortriptyline, 75 mg/d, but she could not tolerate these medications because of severe xerostomia.

After taking sertraline, 150 mg/d, for 8 weeks, Mrs. L improves and has a Patient Health Questionnaire score of 6, indicating mild depression. Her initial complaints of diarrhea and nausea have resolved, but Mrs. L now reports that she and her husband are having marital difficulties because she cannot achieve orgasm during sexual intercourse. She did not have this problem when she was taking bupropion. Her husband occasionally takes the phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor sildenafil before intercourse, and Mrs. L asks you if this medication will help her achieve orgasm.

DSM-IV-TR defines sexual dysfunction as disturbances in sexual desire and/or in the sexual response cycle (excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution) that result in marked distress and interpersonal difficulty.1 Sexual dysfunction can occur with the use of any antidepressant with serotonergic activity; it affects an estimated 50% to 70% of patients who take SSRIs.2 Sexual dysfunction can occur with all SSRIs; however, higher rates of sexual dysfunction are found with citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline.3 Studies have suggested there may be a dose-side effect relationship with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.4

Several factors can increase a patient’s risk of sexual dysfunction and should be considered before prescribing an antidepressant or when a patient presents with new or worsening sexual dysfunction (Table 1).5 In general, nonserotonergic agents such as bupropion, mirtazapine, and nefazodone are associated with lower rates of sexual dysfunction. The pharmacology of these agents explains their decreased propensity to cause sexual dysfunction. These agents increase levels of dopamine in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system either by blocking reuptake (bupropion) or antagonizing the serotonin subtype-2 receptor and facilitating disinhibition of decreased dopamine downstream (nefazodone and mirtazapine).

Table 1

Risk factors for sexual dysfunction

| Sex | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Women | History of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, physical inactivity |

| Men | Severe hyperprolactinemia, smoking |

| Both sexes | Poor to fair health, genitourinary disease, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, increasing age, psychiatric disorders, relationship difficulties |

| Source: Reference 5 | |

One option for treating antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction in women is PDE5 inhibitors, which are used to treat erectile dysfunction (ED). These medications ameliorate ED by inhibiting degradation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate by PDE5, which increases blood flow to the penis during sexual stimulation. Although these medications are not FDA-approved for treating sexual dysfunction in women, adjunctive PDE5 inhibitor treatment may be beneficial for sexual dysfunction in females because similar mediators, such as nitric oxide and cyclic guanosine monophosphate, involved in the nonadrenergic-noncholinergic signaling that controls sexual stimulation in men also are found in female genital tissue.6

When treating a woman with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, consider nonpharmacologic treatments both before and during pharmacotherapy (Table 2).7,8 See Table 3 for a comparison of pharmacokinetics, side effects, and drug interactions of the 4 FDA-approved PDE5 inhibitors—avanafil, sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil.

Table 2

Management strategies for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction

| Intervention | Comments |

|---|---|

| Nonpharmacologic | |

| Lifestyle modifications | Encourage healthy eating, weight loss, smoking cessation, substance abuse treatment, or minimizing alcohol intake to improve patient self-image and overall health |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy | Patients can identify coping strategies for reducing symptom severity and preventing worsening sexual dysfunction |

| Sex therapy | May benefit patients with relationship difficulties |

| ‘Watch and wait’ | Spontaneous resolving (or ‘adaptation’) of sexual dysfunction with antidepressants can take ≥6 months. Studies have found adaptation rates generally are low (~10%) |

| Pharmacologic | |

| Drug holiday | May be an option for patients taking antidepressants with shorter half-lives and patients taking lower doses. Be cautious of empowering patients to stop their own medications as needed |

| Dosage reduction | Serotonergic antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction may be related to dose. Little research has been conducted on this method and the patient’s clinical status must be considered |

| Dose timing | Instructing a patient to take the antidepressant after his or her usual time of sexual activity (eg, patients who engage in sexual activity at night should take the antidepressant before falling asleep). This may allow the drug level to be lowest during sexual activity |

| Switching medications | Case reports, retrospective studies, and RCTs suggest switching to a different antidepressant with less serotonergic activity may be appropriate, particularly if the patient has not responded to the current antidepressant |

| Adjunctive therapy | RCTs support adjunctive bupropion (≥300 mg/d) or olanzapine (5 mg/d) as treatment for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction in women Studies have found no improvement in sexual functioning with adjunctive buspirone, granisetron, amantadine, mirtazapine, yohimbine, ephedrine, or ginkgo biloba in women |

| RCTs: randomized controlled trials; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor Source: Reference 7,8 | |

Table 3

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors: A comparison

| Medication | Dose rangea | Pharmacokinetics | Side effects | Significant drug interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avanafil | 50 to 200 mg, 30 minutes before sexual activity | Bioavailability: N/A (high-fat meal delays Tmax by 60 minutes and reduces Cmax by 24% to 39%; clinically insignificant) Half life: 5 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, nasal congestion, nasopharyngitis, backache | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased avanafil levels) Contraindicated within 12 hours of nitrate use (eg, nitroglycerin) |

| Sildenafil | 25 to 100 mg, 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity | Bioavailability: 41% (food/high-fat meal delays Tmax by 60 minutes and reduces Cmax by 29%) Half life: 4 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, erythema, indigestion, insomnia, visual disturbances (blue vision) | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased sildenafil levels) Contraindicated within 24 hours of nitrate use |

| Tadalafil | 10 to 20 mg, 30 minutes before sexual activity | Bioavailability: N/A (not affected by food) Half life: 17.5 hours (duration of action up to 36 hours) Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, indigestion, nasal congestion, dizziness, myalgia, and back pain | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased tadalafil levels) Contraindicated within 48 hours of nitrate use |

| Vardenafil | 5 to 20 mg, 30 minutes to 2 hours before sexual activity | Bioavailability: 15% for film-coated tablet (high-fat meal reduces Cmax by 18% to 50%) Half life: 4 to 5 hours Metabolism: CYP3A4 | Headache, flushing, indigestion, nasal congestion, dizziness, visual disturbances (blue vision) | Strong CYP3A4 inhibitors (increased vardenafil levels) Contraindicated within 24 hours of nitrate use |

| aTypical dose range for treatment of erectile dysfunction Cmax: maximum concentration; CYP: cytochrome P450; Tmax: time to maximum concentration Source: Micromedex® Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Healthcare. Accessed October 10, 2012 | ||||

Limited evidence for sildenafil

Case reports, a few small open-label trials, and 1 prospective, randomized controlled trial (RCT) have evaluated sildenafil as an adjunctive treatment for serotonergic antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in women.6,9 Nurnberg et al6 examined the efficacy of adjunctive sildenafil in women with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. This 8-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind, RCT used a flexible dose (50 or 100 mg), intention-to-treat design to assess the effect of sildenafil on 98 premenopausal women whose depression was in remission. Ten patients were taking the serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitor venlafaxine, 1 was taking the TCA clomipramine, and 87 were receiving an SSRI. Patients were instructed to take sildenafil or placebo 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity. The primary outcome was mean change from baseline on the Clinical Global Impression-Sexual Function (CGI-SF) scale.

Women taking sildenafil showed significant improvement compared with those taking placebo, with a treatment difference between groups of 0.8 (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.0; =.001). Additionally, 23% of sildenafil-treated patients reported no improvement with the intervention, compared with 73% of patients receiving placebo. Secondary outcomes using 3 validated scales that evaluated specific phases of sexual function found that patients’ orgasmic function significantly benefited from sildenafil treatment, while desire, arousal, and overall satisfaction were not significantly different.

Although these findings seem to support sildenafil for treating serotonergic antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in women, the study had a relatively small treatment effect in a well-defined patient population; therefore, replication in future trials and different patient populations is warranted. Overall, sildenafil was well tolerated, despite patient reports of headaches, flushing, visual disturbances, dyspepsia, nasal congestion, and palpitations. Finally, cost vs benefit should be considered; PDE5 inhibitors may not be covered by insurance or may require prior authorization.

CASE CONTINUED: Symptoms resolve

Bupropion is not an appropriate choice for Mrs. L because of her seizure risk. Mirtazapine is ruled out because in the past she experienced excessive somnolence that impaired her ability to function. You are not comfortable prescribing nefazodone because of its risk of hepatotoxicity or suggesting that Mrs. L take a “drug holiday” (stop taking any antidepressants for a short period) because of the risk of depressive relapse. You suggest that Mrs. L continue to take sertraline because sometimes antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction resolves after ≥6 months of treatment with the same agent, but she is adamant that her relationship with her husband will deteriorate if she waits that long. She also declines cognitive-behavioral therapy because her job doesn’t allow the time or flexibility to commit to the sessions.

You prescribe sildenafil, 50 mg, and instruct Mrs. L to take 1 tablet 1 to 2 hours before sexual activity. This treatment improves her ability to achieve orgasm. She tolerates the drug well and after 8 weeks of treatment her CGI-SF score improves from 6 at baseline, indicating extreme dysfunction, to 2, indicating normal function. Ten months into her sertraline treatment, Mrs. L discovers she no longer requires sildenafil to achieve orgasm.

Related Resources

- Nurnberg HG. An evidence-based review updating the various treatment and management approaches to serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated sexual dysfunction. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008;44(2):147-168.

- NIH Medline Plus. Sexual problems in women. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/sexualproblemsinwomen.html.

- Sturpe DA, Mertens MK, Scoville C. What are the treatment options for SSRI-related sexual dysfunction? J Fam Pract. 2002;51(8):681.

Drug Brand Names

- Amantadine • Symadine, Symmetrel

- Avanafil • Stendra

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Granisetron • Kytril

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nefazodone • Serzone

- Nitroglycerin • Nitrostat

- Nortriptyline • Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Sildenafil • Viagra

- Tadalafil • Cialis

- Vardenafil • Levitra

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Burghardt receives grant or research support from the University of Michigan Depression Center.

Ms. Gardner reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, et al. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 3):10-21.

3. Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):259-266.

4. Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among newer antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):357-366.

5. Lewis RW, Fugl-Meyer KS, Bosch R, et al. Epidemiology/risk factors of sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):35-39.

6. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(4):395-404.

7. Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Hawton K. Strategies for managing antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2005;88(3):241-254.

8. Balon R. SSRI-associated sexual dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1504-1509.

9. Brown DA, Kyle JA, Ferrill MJ. Assessing the clinical efficacy of sildenafil for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(7):1275-1285.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, et al. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 3):10-21.