User login

Should you treat asymptomatic bacteriuria in an older adult with altered mental status?

THE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and osteopenia was brought to the emergency department (ED) by her daughter. The woman had fallen 2 days earlier and had been experiencing a change in mental status (confusion) for the previous 4 days. Prior to her change in mental status, the patient had been independent in all activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Her daughter could not recall any symptoms of illness; new or recently changed medications; complaints of pain, constipation, diarrhea, urinary frequency, or hematuria; or changes in continence prior to the onset of her mother’s confusion.

The patient’s medications included amlodipine, atorvastatin, calcium/vitamin D, and acetaminophen (as needed). In the ED, her vital signs were normal, and her cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams were unremarkable. A limited neurologic exam showed that the patient was oriented only to person and could not answer questions about her symptoms or follow commands. She could move all of her extremities equally and could ambulate; she had no facial asymmetry or slurred speech. Her exam was negative for orthostatic hypotension.

Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and troponin levels were normal. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no abnormalities. X-rays of her right hip and elbow were negative for fracture. Computed tomography of her head was negative for acute findings, and a chest x-ray was normal.

Her urinalysis showed many bacteria and large leukocyte esterase, and a urine culture was sent out. She was hemodynamically stable and there were no known urinary symptoms, so no empiric antibiotics were started. She was admitted for further evaluation of her altered mental status (AMS).

On our service, she was given intravenous fluids, and oral intake was encouraged. She had normal levels of B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. She was negative for HIV and syphilis. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiograms and troponin levels. Her telemetry showed a normal sinus rhythm.

After 2 days, her vital signs and labs remained stable and no other abnormalities were found; however, she had not returned to her baseline mental status. Then the urine culture returned with > 105 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli, prompting a resident to curbside me (AP) and ask: “I shouldn’t treat this patient based on her urine culture—she’s just colonized, right? Or should I treat her because she’s altered?”

Continue to: THE CHALLENGE

THE CHALLENGE

Identifying and managing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults often presents a challenge, further complicated if patients have AMS or cognitive impairment and are unable to confirm or deny urinary symptoms.

Consider, for instance, the definition of symptomatic UTI: significant bacteriuria (≥ 105 CFU/mL) and pyuria (> 10 WBC/hpf) with UTI-specific symptoms (fever, acute dysuria, new or worsening urgency or frequency, new urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, and suprapubic or costovertebral angle pain or tenderness).1 In older adults, these parameters require a more careful look.

For instance, while we use the cutoff of ≥ 105 CFU/mL to define “significant” bacteriuria, the truth is that we don’t know the colony count threshold that can help identify patients who are at risk of serious illness and might benefit from antibiotic treatment.2

After reviewing the culture results, clinicians then face 2 specific challenges: differentiating between acute vs chronic symptoms and related vs unrelated symptoms in the older adult population.

Challenge 1: There is a high prevalence of chronic genitourinary symptoms in older adults that can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between an acute UTI and the acute recognition of a chronic, non-UTI problem.1

Continue to: Challenge 2

Challenge 2: There is a high prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults. For instance, diuretics for heart failure can cause UTI-specific symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and even incontinence. Cognitive impairment can make it difficult to obtain the key components of the history needed to make a UTI diagnosis.1

Lastly, there are aspects of normal aging physiology that complicate the detection of infections, such as the fact that older adults may not mount a “true” fever to meet criteria for a symptomatic UTI. Therefore, fever in institutionalized or frail community-dwelling older adults has been redefined as an oral temperature ≥ 100 °F, 2 repeated oral temperatures > 99 °F, or an increase in temperature ≥ 2 °F from baseline.3

So how to proceed with our case patient? The following questions helped guide the approach to her care.

Is this patient asymptomatic?

Yes. The patient presented with nonspecific symptoms (falls and delirium) with bacteriuria suggesting asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). These symptoms are referred to as geriatric syndromes that, by definition, are “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effects of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges.”4

As geriatric syndromes, falls and delirium are unlikely to be caused by one process, such as a UTI, but rather from multiple morbid processes. It is also important to note that there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

Continue to: So, while we could...

So, while we could have diagnosed a UTI in this older adult with bacteriuria and delirium, it would have been premature closure and an incomplete assessment. We would have risked potentially missing other significant causes of her delirium and unnecessarily exposing the patient to antibiotics.

Are antibiotics generally useful in older adults who you believe to be asymptomatic with a urine culture showing bacteriuria?

No. The goal of antibiotic treatment for a symptomatic UTI is to ameliorate symptoms; therefore, there is no indication for antibiotics in ASB and no evidence of survival benefit.2 And, as noted earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

The use of antibiotics in the asymptomatic setting will eradicate any bacteriuria but also increase the risk of reinfection, resistant organisms, antibiotic adverse reactions, and medication interactions.1

What is the recommendation for management of nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium and falls, in a geriatric patient such as this one with bacteriuria?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)’s 2019 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria recommends a thorough assessment (for other causes) and careful observation, rather than immediate antimicrobial treatment and cessation of evaluation for other causes.5 (IDSA made this recommendation based on low-quality evidence.) The group found a high certainty of harm and low certainty of benefit in treating older adults with antibiotics for ASB.

This recommendation highlights the key geriatric principle of “geriatric syndromes” and the multifactorial nature of findings such as delirium and falls. It encourages clinicians to continue their thorough assessment for other causes in addition to bacteriuria.5 Even in the event that antibiotics are immediately initiated, we would recommend avoiding premature closure and continuing to evaluate for other causes.

Continue to: It is reasonable to...

It is reasonable to obtain a dipstick if, after the observation period (1-7 days, with earlier follow-up for frail patients), the patient continues to have the nonspecific symptoms.1 If the dipstick is negative, there is no need for further evaluation of UTI. If it’s positive, then it’s appropriate to send for urinalysis and urine culture.1

If the urine culture is negative, continue looking for other etiologies. If it’s positive, but there is resolution of symptoms, there is no need to treat. If it’s positive and symptoms persist, consider antibiotic treatment.1

CASE RESOLUTION

The team closely monitored the patient and delayed empiric antibiotics while continuing the AMS work-up. After 2 days in the hospital, her delirium persisted, but she had no UTI-specific symptoms and she remained hemodynamically stable.

I (AP) recommended antibiotic treatment guided by the urine culture sensitivity report: initially 1 g of ceftriaxone IV q24h with transition (after symptom improvement and prior to discharge) to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg q12h, for a total of 10 days of treatment. I emphasized that we were treating bacteriuria with persisting delirium without any other etiology identified. The patient returned to her baseline mental status after a few days of treatment and was discharged home.

THE TAKEAWAY

Avoid premature closure by stopping at the diagnosis of a “UTI” in an older adult with nonspecific symptoms and bacteriuria to avoid the risk of overlooking other important and potentially life-threatening causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

L. Amanda Perry, MD, 1919 West Taylor Street, Mail Code 663, Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected]

1. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303

2. Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”- requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650-1655. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14907

3. Ashraf MS, Gaur S, Bushen OY, et al; Infection Advisory SubCommittee for AMDA—The Society of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections in post-acute and long-term care settings: a consensus statement from AMDA’s Infection Advisory Subcommittee. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:12-24 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.004

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti, ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121

THE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and osteopenia was brought to the emergency department (ED) by her daughter. The woman had fallen 2 days earlier and had been experiencing a change in mental status (confusion) for the previous 4 days. Prior to her change in mental status, the patient had been independent in all activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Her daughter could not recall any symptoms of illness; new or recently changed medications; complaints of pain, constipation, diarrhea, urinary frequency, or hematuria; or changes in continence prior to the onset of her mother’s confusion.

The patient’s medications included amlodipine, atorvastatin, calcium/vitamin D, and acetaminophen (as needed). In the ED, her vital signs were normal, and her cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams were unremarkable. A limited neurologic exam showed that the patient was oriented only to person and could not answer questions about her symptoms or follow commands. She could move all of her extremities equally and could ambulate; she had no facial asymmetry or slurred speech. Her exam was negative for orthostatic hypotension.

Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and troponin levels were normal. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no abnormalities. X-rays of her right hip and elbow were negative for fracture. Computed tomography of her head was negative for acute findings, and a chest x-ray was normal.

Her urinalysis showed many bacteria and large leukocyte esterase, and a urine culture was sent out. She was hemodynamically stable and there were no known urinary symptoms, so no empiric antibiotics were started. She was admitted for further evaluation of her altered mental status (AMS).

On our service, she was given intravenous fluids, and oral intake was encouraged. She had normal levels of B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. She was negative for HIV and syphilis. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiograms and troponin levels. Her telemetry showed a normal sinus rhythm.

After 2 days, her vital signs and labs remained stable and no other abnormalities were found; however, she had not returned to her baseline mental status. Then the urine culture returned with > 105 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli, prompting a resident to curbside me (AP) and ask: “I shouldn’t treat this patient based on her urine culture—she’s just colonized, right? Or should I treat her because she’s altered?”

Continue to: THE CHALLENGE

THE CHALLENGE

Identifying and managing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults often presents a challenge, further complicated if patients have AMS or cognitive impairment and are unable to confirm or deny urinary symptoms.

Consider, for instance, the definition of symptomatic UTI: significant bacteriuria (≥ 105 CFU/mL) and pyuria (> 10 WBC/hpf) with UTI-specific symptoms (fever, acute dysuria, new or worsening urgency or frequency, new urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, and suprapubic or costovertebral angle pain or tenderness).1 In older adults, these parameters require a more careful look.

For instance, while we use the cutoff of ≥ 105 CFU/mL to define “significant” bacteriuria, the truth is that we don’t know the colony count threshold that can help identify patients who are at risk of serious illness and might benefit from antibiotic treatment.2

After reviewing the culture results, clinicians then face 2 specific challenges: differentiating between acute vs chronic symptoms and related vs unrelated symptoms in the older adult population.

Challenge 1: There is a high prevalence of chronic genitourinary symptoms in older adults that can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between an acute UTI and the acute recognition of a chronic, non-UTI problem.1

Continue to: Challenge 2

Challenge 2: There is a high prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults. For instance, diuretics for heart failure can cause UTI-specific symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and even incontinence. Cognitive impairment can make it difficult to obtain the key components of the history needed to make a UTI diagnosis.1

Lastly, there are aspects of normal aging physiology that complicate the detection of infections, such as the fact that older adults may not mount a “true” fever to meet criteria for a symptomatic UTI. Therefore, fever in institutionalized or frail community-dwelling older adults has been redefined as an oral temperature ≥ 100 °F, 2 repeated oral temperatures > 99 °F, or an increase in temperature ≥ 2 °F from baseline.3

So how to proceed with our case patient? The following questions helped guide the approach to her care.

Is this patient asymptomatic?

Yes. The patient presented with nonspecific symptoms (falls and delirium) with bacteriuria suggesting asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). These symptoms are referred to as geriatric syndromes that, by definition, are “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effects of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges.”4

As geriatric syndromes, falls and delirium are unlikely to be caused by one process, such as a UTI, but rather from multiple morbid processes. It is also important to note that there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

Continue to: So, while we could...

So, while we could have diagnosed a UTI in this older adult with bacteriuria and delirium, it would have been premature closure and an incomplete assessment. We would have risked potentially missing other significant causes of her delirium and unnecessarily exposing the patient to antibiotics.

Are antibiotics generally useful in older adults who you believe to be asymptomatic with a urine culture showing bacteriuria?

No. The goal of antibiotic treatment for a symptomatic UTI is to ameliorate symptoms; therefore, there is no indication for antibiotics in ASB and no evidence of survival benefit.2 And, as noted earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

The use of antibiotics in the asymptomatic setting will eradicate any bacteriuria but also increase the risk of reinfection, resistant organisms, antibiotic adverse reactions, and medication interactions.1

What is the recommendation for management of nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium and falls, in a geriatric patient such as this one with bacteriuria?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)’s 2019 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria recommends a thorough assessment (for other causes) and careful observation, rather than immediate antimicrobial treatment and cessation of evaluation for other causes.5 (IDSA made this recommendation based on low-quality evidence.) The group found a high certainty of harm and low certainty of benefit in treating older adults with antibiotics for ASB.

This recommendation highlights the key geriatric principle of “geriatric syndromes” and the multifactorial nature of findings such as delirium and falls. It encourages clinicians to continue their thorough assessment for other causes in addition to bacteriuria.5 Even in the event that antibiotics are immediately initiated, we would recommend avoiding premature closure and continuing to evaluate for other causes.

Continue to: It is reasonable to...

It is reasonable to obtain a dipstick if, after the observation period (1-7 days, with earlier follow-up for frail patients), the patient continues to have the nonspecific symptoms.1 If the dipstick is negative, there is no need for further evaluation of UTI. If it’s positive, then it’s appropriate to send for urinalysis and urine culture.1

If the urine culture is negative, continue looking for other etiologies. If it’s positive, but there is resolution of symptoms, there is no need to treat. If it’s positive and symptoms persist, consider antibiotic treatment.1

CASE RESOLUTION

The team closely monitored the patient and delayed empiric antibiotics while continuing the AMS work-up. After 2 days in the hospital, her delirium persisted, but she had no UTI-specific symptoms and she remained hemodynamically stable.

I (AP) recommended antibiotic treatment guided by the urine culture sensitivity report: initially 1 g of ceftriaxone IV q24h with transition (after symptom improvement and prior to discharge) to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg q12h, for a total of 10 days of treatment. I emphasized that we were treating bacteriuria with persisting delirium without any other etiology identified. The patient returned to her baseline mental status after a few days of treatment and was discharged home.

THE TAKEAWAY

Avoid premature closure by stopping at the diagnosis of a “UTI” in an older adult with nonspecific symptoms and bacteriuria to avoid the risk of overlooking other important and potentially life-threatening causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

L. Amanda Perry, MD, 1919 West Taylor Street, Mail Code 663, Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 78-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis, and osteopenia was brought to the emergency department (ED) by her daughter. The woman had fallen 2 days earlier and had been experiencing a change in mental status (confusion) for the previous 4 days. Prior to her change in mental status, the patient had been independent in all activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Her daughter could not recall any symptoms of illness; new or recently changed medications; complaints of pain, constipation, diarrhea, urinary frequency, or hematuria; or changes in continence prior to the onset of her mother’s confusion.

The patient’s medications included amlodipine, atorvastatin, calcium/vitamin D, and acetaminophen (as needed). In the ED, her vital signs were normal, and her cardiopulmonary and abdominal exams were unremarkable. A limited neurologic exam showed that the patient was oriented only to person and could not answer questions about her symptoms or follow commands. She could move all of her extremities equally and could ambulate; she had no facial asymmetry or slurred speech. Her exam was negative for orthostatic hypotension.

Her complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and troponin levels were normal. Her electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm with no abnormalities. X-rays of her right hip and elbow were negative for fracture. Computed tomography of her head was negative for acute findings, and a chest x-ray was normal.

Her urinalysis showed many bacteria and large leukocyte esterase, and a urine culture was sent out. She was hemodynamically stable and there were no known urinary symptoms, so no empiric antibiotics were started. She was admitted for further evaluation of her altered mental status (AMS).

On our service, she was given intravenous fluids, and oral intake was encouraged. She had normal levels of B12, folic acid, and thyroid-stimulating hormone. She was negative for HIV and syphilis. Acute coronary syndrome was ruled out with normal electrocardiograms and troponin levels. Her telemetry showed a normal sinus rhythm.

After 2 days, her vital signs and labs remained stable and no other abnormalities were found; however, she had not returned to her baseline mental status. Then the urine culture returned with > 105 CFU/mL of Escherichia coli, prompting a resident to curbside me (AP) and ask: “I shouldn’t treat this patient based on her urine culture—she’s just colonized, right? Or should I treat her because she’s altered?”

Continue to: THE CHALLENGE

THE CHALLENGE

Identifying and managing urinary tract infections (UTIs) in older adults often presents a challenge, further complicated if patients have AMS or cognitive impairment and are unable to confirm or deny urinary symptoms.

Consider, for instance, the definition of symptomatic UTI: significant bacteriuria (≥ 105 CFU/mL) and pyuria (> 10 WBC/hpf) with UTI-specific symptoms (fever, acute dysuria, new or worsening urgency or frequency, new urinary incontinence, gross hematuria, and suprapubic or costovertebral angle pain or tenderness).1 In older adults, these parameters require a more careful look.

For instance, while we use the cutoff of ≥ 105 CFU/mL to define “significant” bacteriuria, the truth is that we don’t know the colony count threshold that can help identify patients who are at risk of serious illness and might benefit from antibiotic treatment.2

After reviewing the culture results, clinicians then face 2 specific challenges: differentiating between acute vs chronic symptoms and related vs unrelated symptoms in the older adult population.

Challenge 1: There is a high prevalence of chronic genitourinary symptoms in older adults that can sometimes make it hard to distinguish between an acute UTI and the acute recognition of a chronic, non-UTI problem.1

Continue to: Challenge 2

Challenge 2: There is a high prevalence of multimorbidity in older adults. For instance, diuretics for heart failure can cause UTI-specific symptoms such as urinary urgency, frequency, and even incontinence. Cognitive impairment can make it difficult to obtain the key components of the history needed to make a UTI diagnosis.1

Lastly, there are aspects of normal aging physiology that complicate the detection of infections, such as the fact that older adults may not mount a “true” fever to meet criteria for a symptomatic UTI. Therefore, fever in institutionalized or frail community-dwelling older adults has been redefined as an oral temperature ≥ 100 °F, 2 repeated oral temperatures > 99 °F, or an increase in temperature ≥ 2 °F from baseline.3

So how to proceed with our case patient? The following questions helped guide the approach to her care.

Is this patient asymptomatic?

Yes. The patient presented with nonspecific symptoms (falls and delirium) with bacteriuria suggesting asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB). These symptoms are referred to as geriatric syndromes that, by definition, are “multifactorial health conditions that occur when the accumulated effects of impairments in multiple systems render an older person vulnerable to situational challenges.”4

As geriatric syndromes, falls and delirium are unlikely to be caused by one process, such as a UTI, but rather from multiple morbid processes. It is also important to note that there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

Continue to: So, while we could...

So, while we could have diagnosed a UTI in this older adult with bacteriuria and delirium, it would have been premature closure and an incomplete assessment. We would have risked potentially missing other significant causes of her delirium and unnecessarily exposing the patient to antibiotics.

Are antibiotics generally useful in older adults who you believe to be asymptomatic with a urine culture showing bacteriuria?

No. The goal of antibiotic treatment for a symptomatic UTI is to ameliorate symptoms; therefore, there is no indication for antibiotics in ASB and no evidence of survival benefit.2 And, as noted earlier, there is no evidence to support a causal relationship between bacteriuria and delirium or that antibiotic treatment of bacteriuria improves delirium.2,5

The use of antibiotics in the asymptomatic setting will eradicate any bacteriuria but also increase the risk of reinfection, resistant organisms, antibiotic adverse reactions, and medication interactions.1

What is the recommendation for management of nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium and falls, in a geriatric patient such as this one with bacteriuria?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)’s 2019 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria recommends a thorough assessment (for other causes) and careful observation, rather than immediate antimicrobial treatment and cessation of evaluation for other causes.5 (IDSA made this recommendation based on low-quality evidence.) The group found a high certainty of harm and low certainty of benefit in treating older adults with antibiotics for ASB.

This recommendation highlights the key geriatric principle of “geriatric syndromes” and the multifactorial nature of findings such as delirium and falls. It encourages clinicians to continue their thorough assessment for other causes in addition to bacteriuria.5 Even in the event that antibiotics are immediately initiated, we would recommend avoiding premature closure and continuing to evaluate for other causes.

Continue to: It is reasonable to...

It is reasonable to obtain a dipstick if, after the observation period (1-7 days, with earlier follow-up for frail patients), the patient continues to have the nonspecific symptoms.1 If the dipstick is negative, there is no need for further evaluation of UTI. If it’s positive, then it’s appropriate to send for urinalysis and urine culture.1

If the urine culture is negative, continue looking for other etiologies. If it’s positive, but there is resolution of symptoms, there is no need to treat. If it’s positive and symptoms persist, consider antibiotic treatment.1

CASE RESOLUTION

The team closely monitored the patient and delayed empiric antibiotics while continuing the AMS work-up. After 2 days in the hospital, her delirium persisted, but she had no UTI-specific symptoms and she remained hemodynamically stable.

I (AP) recommended antibiotic treatment guided by the urine culture sensitivity report: initially 1 g of ceftriaxone IV q24h with transition (after symptom improvement and prior to discharge) to oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg q12h, for a total of 10 days of treatment. I emphasized that we were treating bacteriuria with persisting delirium without any other etiology identified. The patient returned to her baseline mental status after a few days of treatment and was discharged home.

THE TAKEAWAY

Avoid premature closure by stopping at the diagnosis of a “UTI” in an older adult with nonspecific symptoms and bacteriuria to avoid the risk of overlooking other important and potentially life-threatening causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

L. Amanda Perry, MD, 1919 West Taylor Street, Mail Code 663, Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected]

1. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303

2. Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”- requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650-1655. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14907

3. Ashraf MS, Gaur S, Bushen OY, et al; Infection Advisory SubCommittee for AMDA—The Society of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections in post-acute and long-term care settings: a consensus statement from AMDA’s Infection Advisory Subcommittee. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:12-24 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.004

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti, ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121

1. Mody L, Juthani-Mehta M. Urinary tract infections in older women: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:844-854. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.303

2. Finucane TE. “Urinary tract infection”- requiem for a heavyweight. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1650-1655. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14907

3. Ashraf MS, Gaur S, Bushen OY, et al; Infection Advisory SubCommittee for AMDA—The Society of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of urinary tract infections in post-acute and long-term care settings: a consensus statement from AMDA’s Infection Advisory Subcommittee. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:12-24 e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.11.004

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti, ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780-791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83-e110. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy1121

Transgender Patients: Providing Sensitive Care

Civil rights for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population have advanced markedly in the past decade, and the medical community has gradually begun to address more of their health concerns. More recently, media attention to transgender individuals has encouraged many more to openly seek care.1,2

It is estimated that anywhere from 0.3% to 5% of the US population identifies as transgender.1-3 While awareness of this population has slowly increased, there is a paucity of research on the hormone treatment that is often essential to patients’ well-being. Studies of surgical options for transgender patients have been minimal, as well.

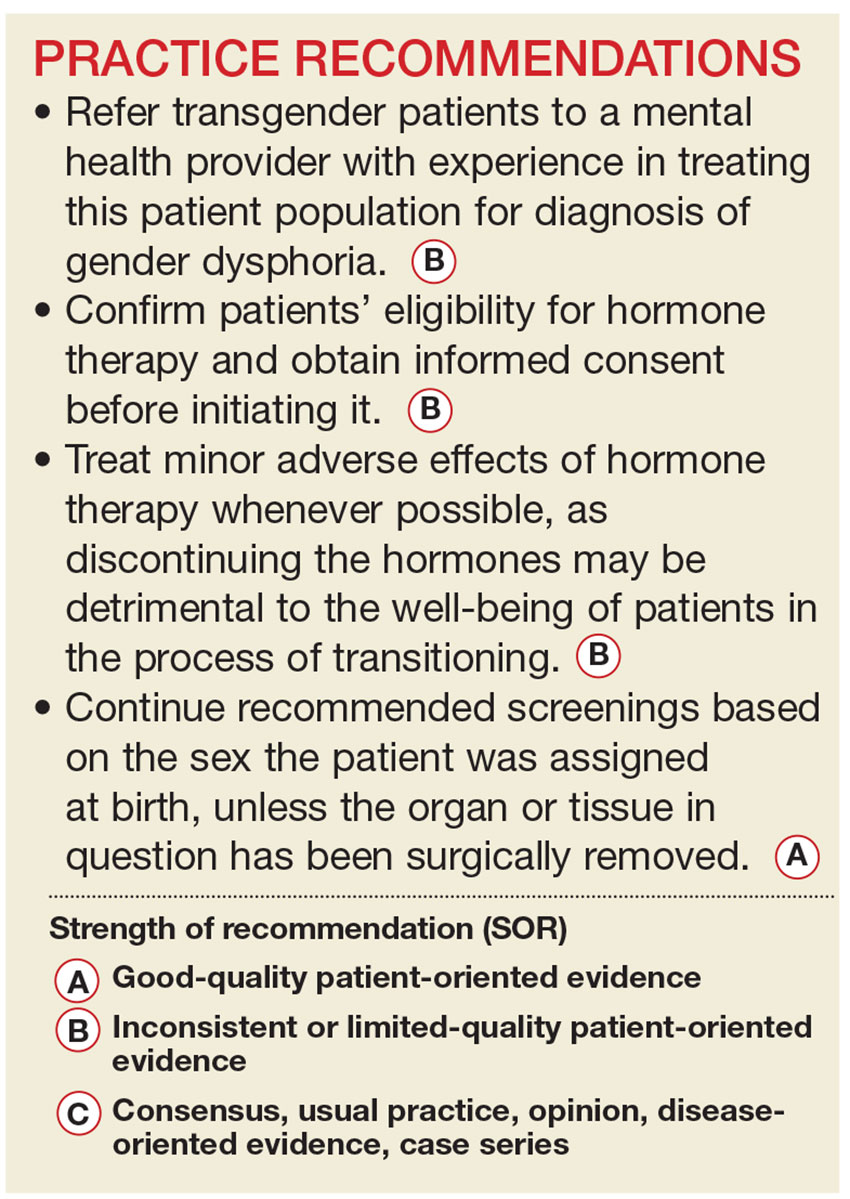

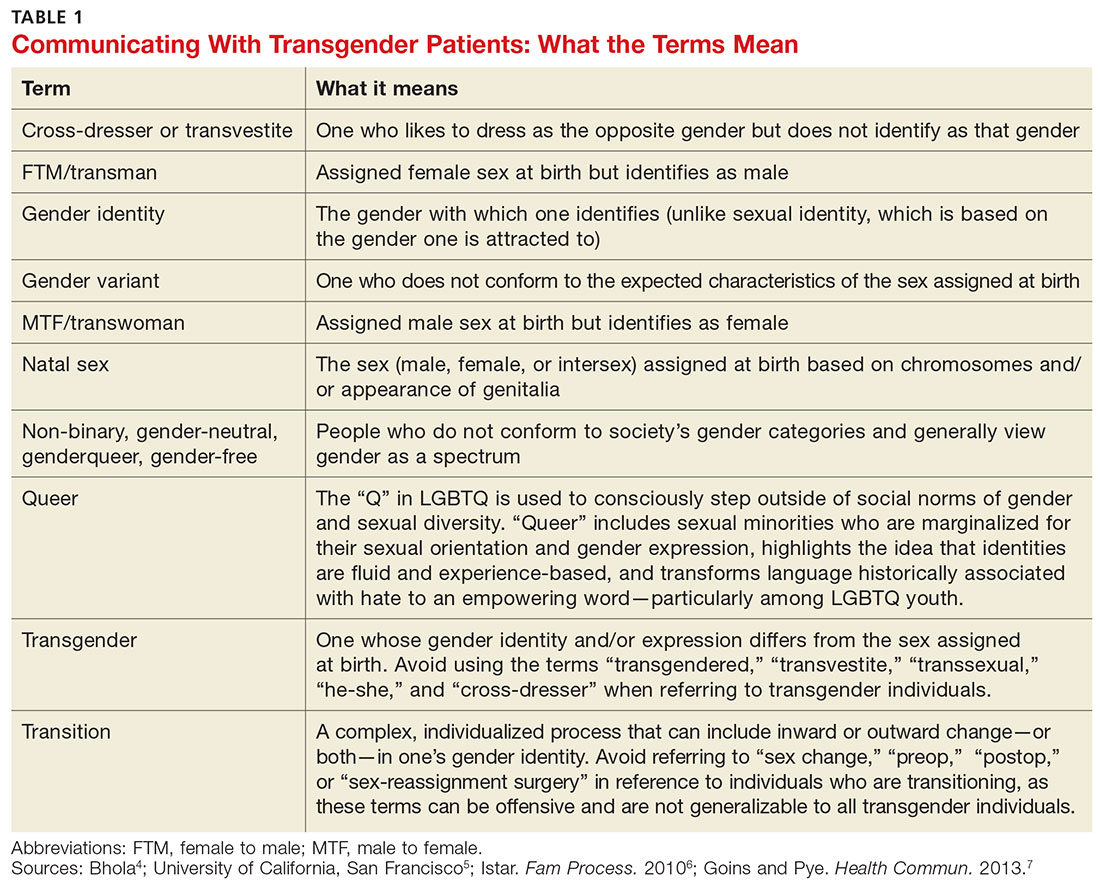

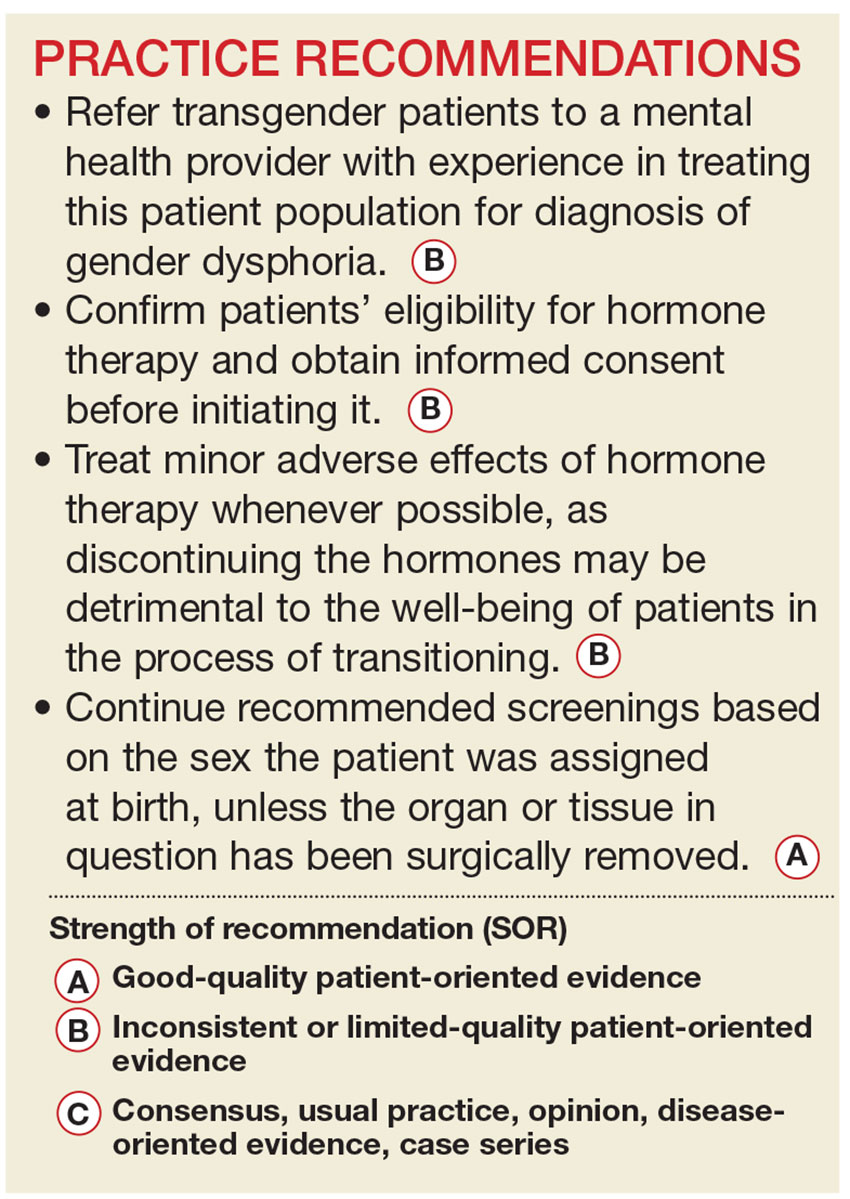

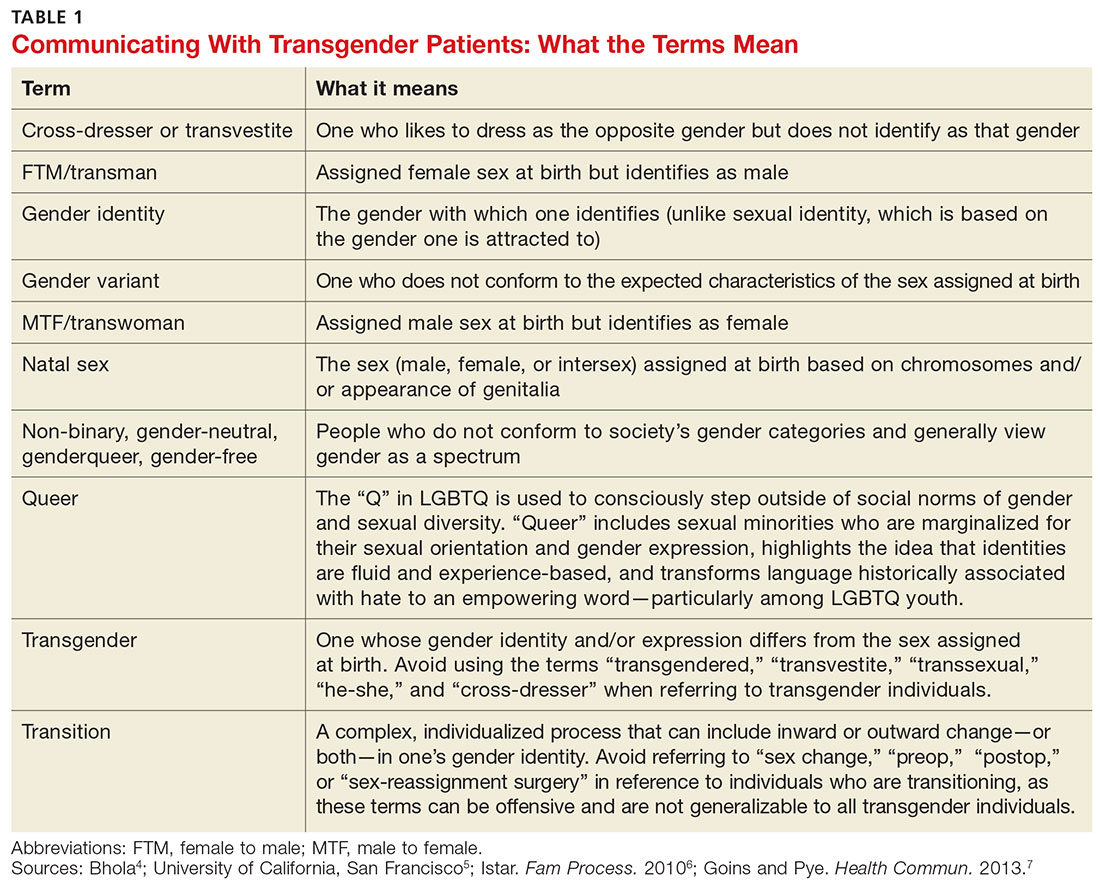

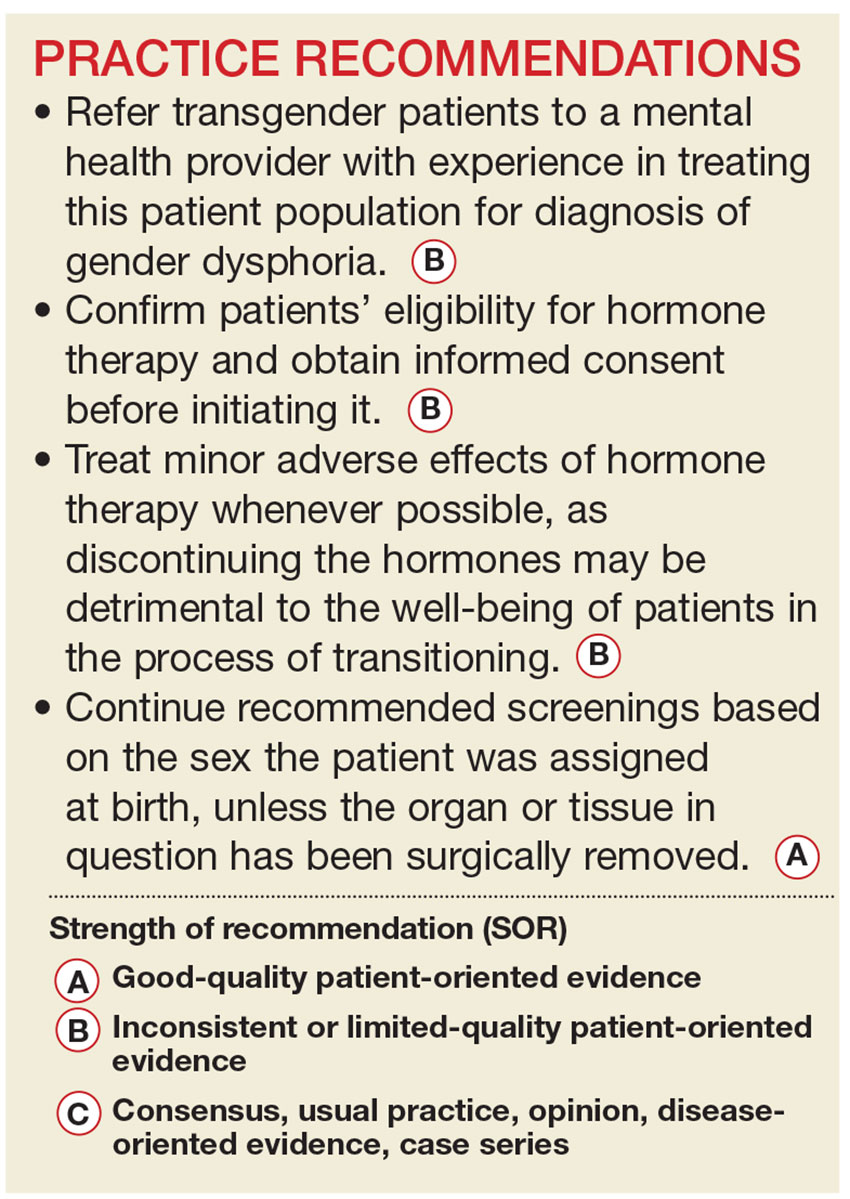

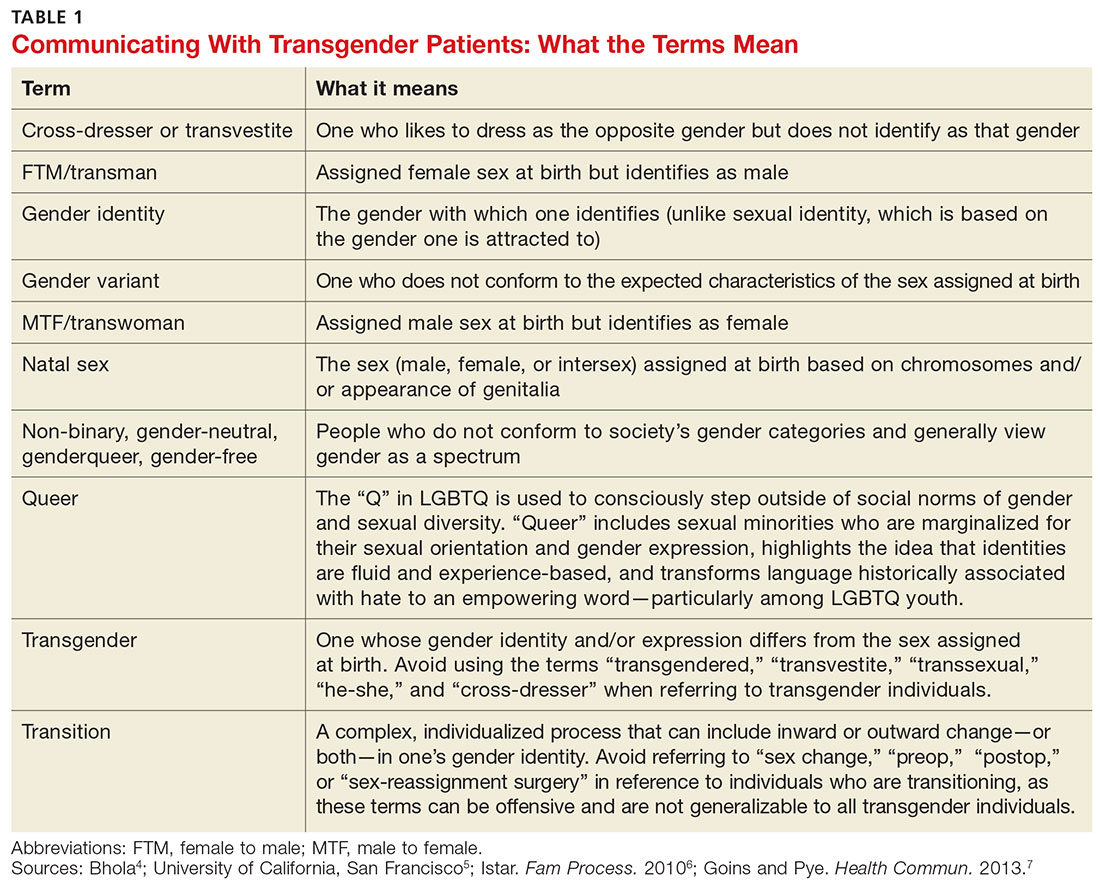

Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to coordinate medical services and ensure continuity of care for transgender patients as they strive to become their authentic selves. Our goal in writing this article is to equip you with the tools to provide this patient population with sensitive, high-quality care (see Table 1).4-7 Our focus is on the diagnosis of gender dysphoria (GD) and its medical and hormonal management—the realm of primary care providers. We briefly discuss surgical management of GD, as well.

UNDERSTANDING AND DIAGNOSING GENDER DYSPHORIA

Two classification systems are used for diagnoses related to GD: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Ed (DSM-5)8 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Rev (ICD-10).9

ICD-10 criteria use the term gender identity disorder; DSM-5 refers to gender dysphoria instead. It is important to emphasize that these classification systems represent an attempt to categorize a group of signs and symptoms that lead to distress for the patient and are not meant to suggest that being transgender is pathological. In fact, in DSM-5—released in 2013—the American Psychiatric Association revised the terminology to emphasize that such individuals are not “disordered” by the nature of their identity, but rather by the distress that being transgender causes.8

For a diagnosis of GD in children, DSM-5 criteria include characteristics perceived to be incongruent between the child’s sex at birth and the self-identified gender based on preferred activities or dislike of his or her own sexual anatomy. The child must meet six or more of the following for at least six months

- A repeatedly stated desire to be, or insistence that he or she is, of the other gender

- In boys, a preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; in girls, insistence on wearing only stereotypical masculine clothing

- Strong and persistent preferences for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy

- A strong rejection of toys/games typically associated with the child’s sex

- Intense desire to participate in stereotypical games and pastimes of the other gender

- Strong preference for playmates of the other gender

- A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

- A strong desire for the primary (eg, penis or vagina) or secondary (eg, menstruation) sex characteristics of the other gender.8

Adolescents and adults must meet two or more of the following for at least six months

- A noticeable incongruence between the gender that the patient sees themselves as and their sex characteristics

- An intense need to do away with (or prevent) his or her primary or secondary sex features

- An intense desire to have the primary and/or secondary sex features of the other gender

- A deep desire to transform into another gender

- A profound need for society to treat them as someone of the other gender

- A powerful assurance of having the characteristic feelings and responses of the other gender.8

For children as well as adolescents and adults, the condition should cause the patient significant distress or significantly affect him or her socially, at work or school, and in other important areas of life.8

Is the patient a candidate for hormone therapy?

Two primary sources—Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7, issued by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)10 and Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons11 by the Endocrine Society—offer clinical practice guidance based on evidence and expert opinion.

WPATH recommends that a mental health professional (MHP) experienced in transgender care diagnose GD to ensure that it is not mistaken for a psychiatric condition manifesting as altered gender identity. However, if no one with such experience is available or accessible in the region, it is reasonable for a primary care provider to make the diagnosis and consider initiating hormone therapy without a mental health referral,12 as the expected benefits outweigh the risks of nontreatment.13

Whether or not an MHP confirms a diagnosis of GD, it is still up to the treating provider to confirm the patient’s eligibility and readiness for hormone therapy: He or she should meet DSM-5 or ICD-10 criteria for GD, have no psychiatric comorbidity (eg, schizophrenia, body dysmorphic disorder, or uncontrolled bipolar disorder) likely to interfere with treatment, understand the expected outcomes and the social benefits and risks, and have indicated a willingness to take the hormones responsibly.

Historically, patients were required to have a documented real-life experience, defined as having fully adopted the new gender role in everyday life for at least three months.10,11 This model has fallen out of favor, however, as it is unsupported by evidence and may place transgender individuals at physical and emotional risk. Instead, readiness is confirmed by obtaining informed consent.12

Puberty may be suppressed with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist in adolescents who have a GD diagnosis and are at Tanner stage 2 to 3 of puberty until age 16. At that point, hormone therapy consistent with their gender identification may be initiated (see “How to Help Transgender Teens”).11

Beginning the transition

The transitioning process is a complex and individualized journey that can include inward or outward change, or both.

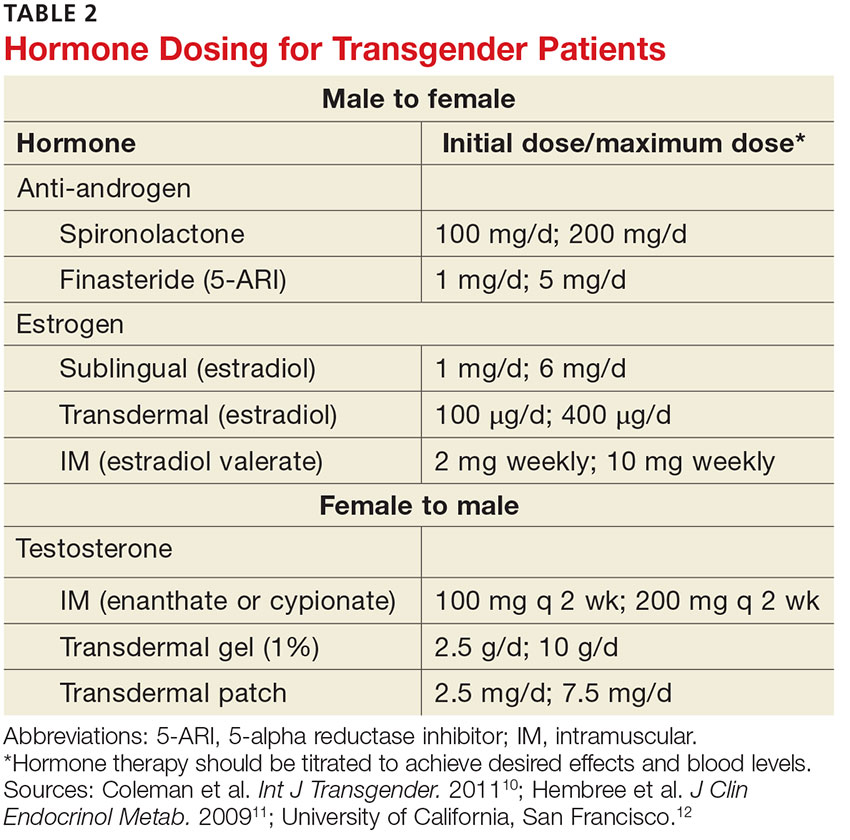

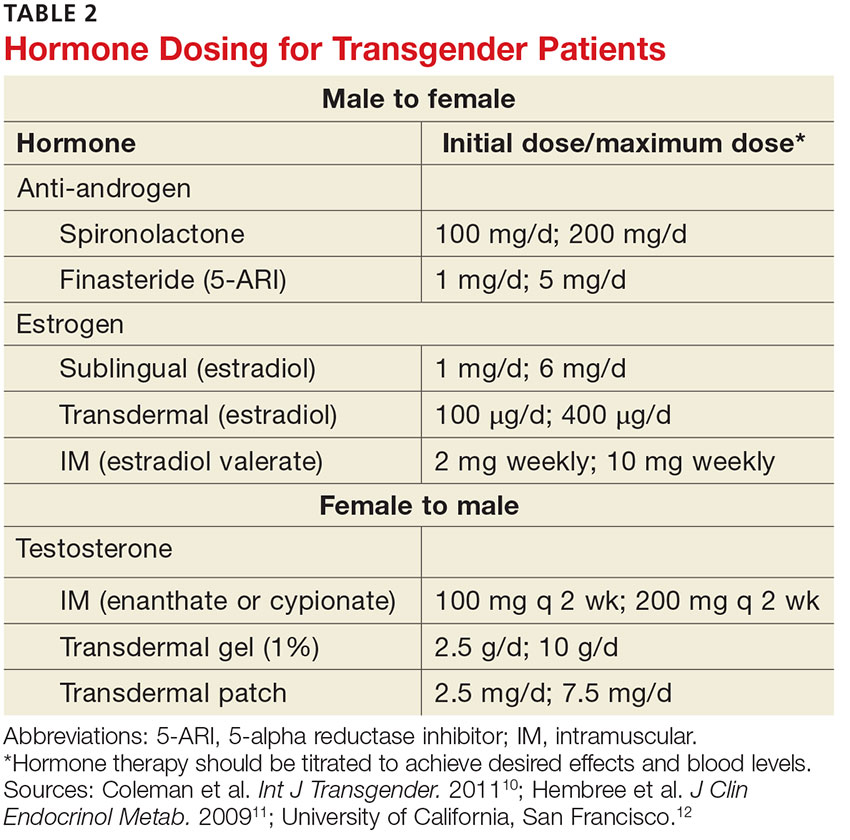

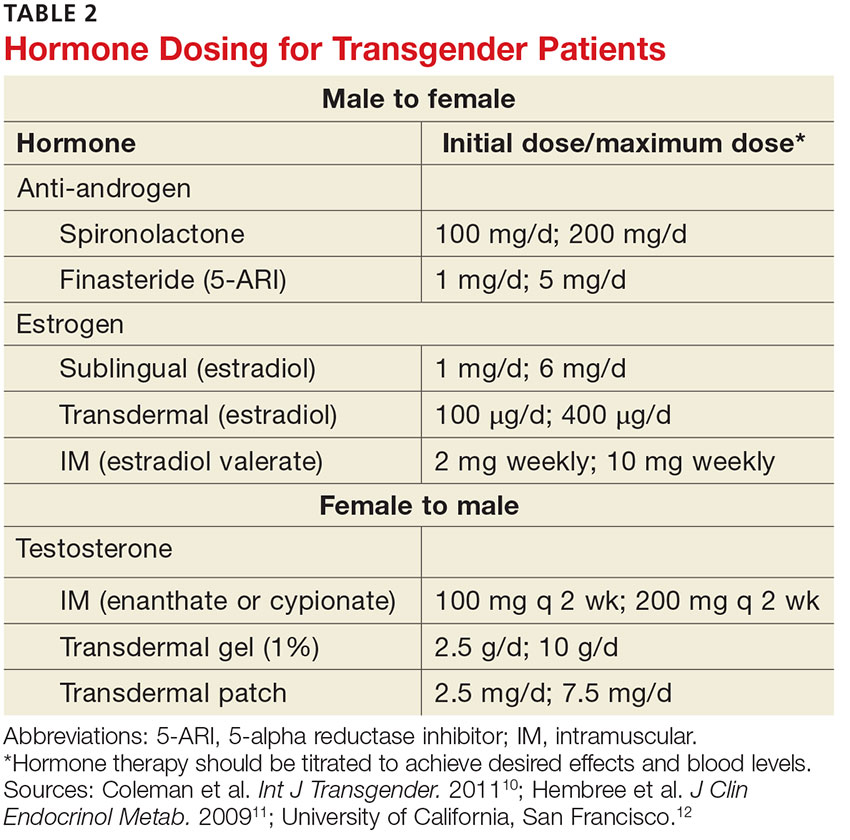

For patients interested in medical interventions, possible therapies include cross-sex hormone administration and gender-affirming surgery. Both are aimed at making the physical and the psychologic more congruent. Hormone treatment (see Table 2) is often essential to reduce the distress of individuals with GD and to help them feel comfortable in their own body.10,11,21 Psychologic conditions, such as depression, tend to improve as the transitioning process gets underway.22

FEMALE-TO-MALE TRANSITION

CASE 1 Jennie R, a 55-year-old postmenopausal patient, comes to your office for an annual exam. Although you’ve been her primary care provider for several years, she confides for the first time that she has never been comfortable as a woman. “I’ve always felt that my body didn’t belong to me,” the patient admits, and goes on to say that for the past several years she has been living as a man. Jennie R says she is ready to start hormone therapy to assist with the gender transition and asks about the process, the benefits and risks, and how quickly she can expect to achieve the desired results.

If Jennie R were your patient, how would you respond?

Masculinizing hormone treatment

As you would explain to a patient like Jennie R, the goal of hormone therapy is to suppress the effects of the sex assigned at birth and replace them with those of the desired gender. In the case of a female transitioning to a male (known as a transman), masculinizing hormones would promote growth of facial and body hair, cessation of menses, increased muscle mass, deepening of the voice, and clitoral enlargement.

Physical changes induced by masculinizing hormone therapy have an expected onset of one to six months and achieve maximum effect in approximately two to five years.10,11 Although there have been no controlled clinical trials evaluating the safety or efficacy of any transitional hormone regimen, WPATH and the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California, San Francisco, suggest initiating intramuscular or transdermal testosterone at increasing doses until normal physiologic male testosterone levels between 350 and 700 ng/dL are achieved, or until cessation of menses.13,25-28 The dose at which either, or both, occur should be continued as long-term maintenance therapy. Medroxyprogesterone can be added, if necessary for menstrual cessation, and a GnRH agonist or endometrial ablation can be used for refractory uterine bleeding.29,30

Testosterone is not a contraceptive. It is important to emphasize to transmen like Jennie that they remain at risk for pregnancy if they are having sex with fertile males. Caution patients not to assume that the possibility of pregnancy ends when menses stop.

Treat minor adverse effects. Adverse effects of masculinizing hormones include vaginal atrophy, fat redistribution and weight gain, polycythemia, acne, scalp hair loss, sleep apnea, elevated liver enzymes, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and bone density loss. Increased risk for cancer of the female organs has not been proven.10,11 It is reasonable to treat minor adverse effects after reviewing the risks/benefits of doing so, as discontinuing hormone therapy could be detrimental to the well-being of transitioning patients.11

There are absolute contraindications to masculinizing hormone therapy, however, including pregnancy, unstable coronary artery disease, and untreated polycythemia with a hematocrit > 55%.10

Monitoring is essential. Patients receiving masculinizing hormone therapy should be monitored every three months during the first year and once or twice a year thereafter, with a focused history (including mood symptoms), physical exam (including weight and blood pressure), and labs (including complete blood count, liver function, renal function, and lipids) at each visit.11,23 Some clinicians also check estradiol levels until they fall below 50 pg/mL,23,27 while others take the cessation of uterine bleeding for > 6 months as an indicator of estrogen suppression.

Preventive health measures continue. Routine screening should continue, based on the patient’s assigned sex at birth. Thus, a transman who has not had a hysterectomy still needs Pap smears, mammograms if the patient has not had a double mastectomy, and bone mineral density (BMD) testing to screen for osteoporosis.31,32 Some experts recommend starting to test BMD at age 50 for patients receiving masculinizing hormones, given the unknown effect of testosterone on bone density.11,31,32

CASE 1 The first question for a transgender patient is about his or her current gender identity, but Jennie R has already reported living as a man. So you start by asking “What name do you prefer to use?” and “Do you prefer to be referred to with male or female pronouns?”

The patient tells you that he sees himself as a man, he wants to be called Jeff, and he prefers male pronouns. You explain that you believe he has gender dysphoria and would benefit from hormone therapy, but it is important to confirm this diagnosis with an MHP. You explain that testosterone can be prescribed for masculinizing effects, and describe the expected effects—more facial and body hair, a deeper voice, and greater muscle mass, among others—and review the likely time frame.

You also discuss the risks of masculinizing hormones (hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and loss of bone density) that will need to be monitored. Before he leaves, you give him the name of an MHP who is experienced in transgender care and tell him to make a follow-up appointment with you after he has seen her. At the conclusion of the visit, you make a note of the patient’s name and gender identity in the chart and inform the staff of the changes.

MALE-TO-FEMALE TRANSITION

CASE 2 Before heading into your office to talk to a new patient named Carl S, you glance at his chart and see that he is a healthy 21-year-old who has come in for a routine physical. When you enter the room, you find Carl wearing a dress, heels, and make-up. After confirming that you have the right patient, you ask, “What is your current gender identity?” “Female,” says Carl, who indicates that she now goes by Carol. The patient has no medical problems, surgical history, or significant family history but reports that she has been taking spironolactone and estrogen for the past three years. Carol also says she has a new female partner and is having unprotected sexual activity.

Feminizing hormone treatment

The desired effects of feminizing hormones include voice change, decreased hair growth, breast growth, body fat redistribution, decreased muscle mass, skin softening, decreased oiliness of skin and hair, and a decrease in spontaneous erections, testicular volume, and sperm production.10,11 The onset of feminizing effects ranges from one month to one year and the expected maximum effect occurs anywhere between three months and five years.10,11 Regimens usually include anti-androgen agents and estrogen.13,26-28

The medications that have been most studied with anti-androgenic effects include spironolactone and 5-α reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) such as finasteride. Spironolactone inhibits testosterone secretion and inhibits androgen binding to androgen receptors; 5-ARIs block the conversion of testosterone to 5-α-dihydrotestosterone, the more active form.

Estrogen can be administered via oral, sublingual, transdermal, or intramuscular route, but parenteral formulations are preferred to avoid first-pass metabolism. The serum estradiol target is similar to the mean daily level of premenopausal women (< 200 pg/mL) and the level of testosterone should be in the normal female range (< 55 ng/dL).13,26-28

The selection of medications should be individualized for each patient. Comorbidities must be considered, as well as the risk for adverse effects, which include venous thromboembolism, elevated liver enzymes, breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hyperprolactinemia, weight gain, gallstones, cerebrovascular disease, and severe migraine headaches.10,11 Estrogen therapy is not reported to induce hypertrophy or premalignant changes in the prostate.33 As is the case for masculinizing hormones, feminizing hormone therapy should be continued indefinitely for long-term effects.

Frequent monitoring is recommended. Patients taking feminizing hormones (transwomen) should be seen every two to three months in the first year and monitored once or twice a year thereafter. Serum testosterone and estradiol levels should initially be monitored every three months; serum electrolytes, specifically potassium, should be monitored every two to three months in the first year until stable.

CASE 2 You recommend that Carol S be screened annually for sexually transmitted diseases, as you would for any 21-year-old patient. You point out, too, that while estrogen and androgen-suppressing therapy decrease sperm production, there is a possibility that the patient could impregnate a female partner and recommend that contraception be used if the couple is not trying to conceive.

You also discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and reasonable expectations of continued treatment. You ask Carol to schedule a follow-up visit in six months, as her hormone regimen is stable. Finally, if the patient remains on hormone therapy, you mention that the only screening unique to men transitioning to women is for breast cancer, which should begin at age 40 to 50 (as it should for all women).

Gender-affirming surgical options

Surgical management of transgender patients is not within the scope of family medicine. But it is essential to know what procedures are available, as you may have occasion to advocate for patients during the surgical referral process and possibly to provide postoperative care.

For transmen, surgical options include chest reconstruction, hysterectomy/oophorectomy, metoidioplasty (using the clitoris to surgically approximate a penis), phalloplasty, scrotoplasty, urethroplasty, and vaginectomy.10,34 The surgeries available for transwomen are orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, penectomy, breast augmentation, thyroid chondroplasty and voice surgery, and facial feminization.10,34 Keep in mind that not all transgender individuals desire surgery as part of the transitioning process.

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Michelle Forcier, MD, MPH, and Karen S. Bernstein, MD, MPH, in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Pew Research Center. A survey of LGBT Americans: attitudes, experiences and values in changing times. www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/a-survey-of-lgbt-americans. Accessed January 13, 2017.

2. Gates GJ. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender? http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2017.

3. van Kesteren PJ, Gooren LJ, Megens JA. An epidemiological and demographic study of transsexuals in The Netherlands. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25:589-600.

4. Bhola S. An ally’s guide to terminology: talking about LGBT people & equality. www.glaad.org/2011/07/28/an-allys-guide-to-terminology-talking-about-lgbt-people-equality. Accessed January 13, 2017.

5. University of California, San Francisco. Transgender terminology. UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/tcoe?page=protocol-terminology. Accessed January 13, 2017.

6. Istar A. How queer! The development of gender identity and sexual orientation in LGBTQ-headed families. Fam Process. 2010;49:268-290.

7. Goins ES, Pye D. Check the box that best describes you: reflexively managing theory and praxis in LGBTQ health communication research. Health Commun. 2013;28:397-407.

8. American Psychiatric Association. Gender dysphoria. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013: 451-459.

9. World Health Organization. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th rev. Classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. 1992; Geneva.

10. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al; World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int J Transgender. 2011; 13:165-232.

11. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endo Metabol. 2009;94:3132-3154.

12. University of California, San Francisco. Assessing readiness for hormones. UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/tcoe?page=protocol-hormone-ready. Accessed January 13, 2017.

13. Gooren L. Hormone treatment of the adult transsexual patient. Horm Res. 2005;64(suppl 2):S31-S36.

14. Hembree WC. Guidelines for pubertal suspension and gender reassignment for transgender adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2011;20:725-732.

15. Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). Harsh realities. The experiences of transgender youth in our nation’s schools. www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/Harsh%20Realities.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2017.

16. Berman M, Balingit M. Eleven states sue Obama administration over bathroom guidance for transgender students. May 25, 2016. Washington Post. www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-nation/wp/2016/05/25/texas-governor-says-state-will-sue-obama-administration-over-bathroom-directive/. Accessed January 13, 2017.

17. de Vries AL, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Delemarre-van de Waal H. Clinical management of gender dysphoria in adolescents. 2006. Vancouver Coastal Health - Transgender Health Program. www.amsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/CaringForTransgenderAdolescents.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2017.

18. TransYouth Family Allies. Empowering transgender youth & families. www.imatyfa.org/. Accessed January 13, 2017.

19. Human Rights Campaign. On our own: a survival guide for independent LGBTQ youth. www.hrc.org/resources/on-our-own-a-survival-guide-for-independent-lgbtq-youth. Accessed January 13, 2017.

20. Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender National Help Center. www.glbthotline.org. Accessed January 13, 2017.

21. University of California, San Francisco. Hormone administration. UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=protocol-hormones. Accessed January 13, 2017.

22. Gorin-Lazard A, Baumstarck K, Boyer L, et al. Hormonal therapy is associated with better self-esteem, mood, and quality of life in transsexuals. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:996-1000.

23. Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995-2010.

24. Boloña ER, Uraga MV, Haddad RM, et al. Testosterone use in men with sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:20-28.

25. Gooren LJ, Giltay EJ. Review of studies of androgen treatment of female-to-male transsexuals: effects and risks of administration of androgens to females. J Sex Med. 2008; 5:765-776.

26. Levy A, Crown A, Reid R. Endocrine intervention for transsexuals. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2003;59:409-418.

27. Moore E, Wisniewski A, Dobs A. Endocrine treatment of transsexual people: a review of treatment regimens, outcomes, and adverse effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3467-3473.

28. Tangpricha V, Ducharme SH, Barber TW, et al. Endocrinologic treatment of gender identity disorders. Endocr Pract. 2003;9:12-21.

29. Dickersin K, Munro MG, Clark M, et al. Hysterectomy compared with endometrial ablation for dysfunctional uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1279-1289.

30. Prasad P, Powell MC. Prospective observational study of Thermablate Endometrial Ablation System as an outpatient procedure. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:476-479.

31. University of California, San Francisco. General prevention and screening. UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=protocol-screening. Accessed January 13, 2017.

32. Ganly I, Taylor EW. Breast cancer in a trans-sexual man receiving hormone replacement therapy. Br J Surg. 1995; 82:341.

33. Meriggiola MC, Gava G. Endocrine care of transpeople part II: a review of cross-sex hormonal treatments, outcomes and adverse effects in transwomen. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83:607-615.

34. University of California, San Francisco. Surgical options. UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=protocol-surgery. Accessed January 13, 2017.

Civil rights for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population have advanced markedly in the past decade, and the medical community has gradually begun to address more of their health concerns. More recently, media attention to transgender individuals has encouraged many more to openly seek care.1,2

It is estimated that anywhere from 0.3% to 5% of the US population identifies as transgender.1-3 While awareness of this population has slowly increased, there is a paucity of research on the hormone treatment that is often essential to patients’ well-being. Studies of surgical options for transgender patients have been minimal, as well.

Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to coordinate medical services and ensure continuity of care for transgender patients as they strive to become their authentic selves. Our goal in writing this article is to equip you with the tools to provide this patient population with sensitive, high-quality care (see Table 1).4-7 Our focus is on the diagnosis of gender dysphoria (GD) and its medical and hormonal management—the realm of primary care providers. We briefly discuss surgical management of GD, as well.

UNDERSTANDING AND DIAGNOSING GENDER DYSPHORIA

Two classification systems are used for diagnoses related to GD: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Ed (DSM-5)8 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Rev (ICD-10).9

ICD-10 criteria use the term gender identity disorder; DSM-5 refers to gender dysphoria instead. It is important to emphasize that these classification systems represent an attempt to categorize a group of signs and symptoms that lead to distress for the patient and are not meant to suggest that being transgender is pathological. In fact, in DSM-5—released in 2013—the American Psychiatric Association revised the terminology to emphasize that such individuals are not “disordered” by the nature of their identity, but rather by the distress that being transgender causes.8

For a diagnosis of GD in children, DSM-5 criteria include characteristics perceived to be incongruent between the child’s sex at birth and the self-identified gender based on preferred activities or dislike of his or her own sexual anatomy. The child must meet six or more of the following for at least six months

- A repeatedly stated desire to be, or insistence that he or she is, of the other gender

- In boys, a preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; in girls, insistence on wearing only stereotypical masculine clothing

- Strong and persistent preferences for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy

- A strong rejection of toys/games typically associated with the child’s sex

- Intense desire to participate in stereotypical games and pastimes of the other gender

- Strong preference for playmates of the other gender

- A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

- A strong desire for the primary (eg, penis or vagina) or secondary (eg, menstruation) sex characteristics of the other gender.8

Adolescents and adults must meet two or more of the following for at least six months

- A noticeable incongruence between the gender that the patient sees themselves as and their sex characteristics

- An intense need to do away with (or prevent) his or her primary or secondary sex features

- An intense desire to have the primary and/or secondary sex features of the other gender

- A deep desire to transform into another gender

- A profound need for society to treat them as someone of the other gender

- A powerful assurance of having the characteristic feelings and responses of the other gender.8

For children as well as adolescents and adults, the condition should cause the patient significant distress or significantly affect him or her socially, at work or school, and in other important areas of life.8

Is the patient a candidate for hormone therapy?

Two primary sources—Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7, issued by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)10 and Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons11 by the Endocrine Society—offer clinical practice guidance based on evidence and expert opinion.

WPATH recommends that a mental health professional (MHP) experienced in transgender care diagnose GD to ensure that it is not mistaken for a psychiatric condition manifesting as altered gender identity. However, if no one with such experience is available or accessible in the region, it is reasonable for a primary care provider to make the diagnosis and consider initiating hormone therapy without a mental health referral,12 as the expected benefits outweigh the risks of nontreatment.13

Whether or not an MHP confirms a diagnosis of GD, it is still up to the treating provider to confirm the patient’s eligibility and readiness for hormone therapy: He or she should meet DSM-5 or ICD-10 criteria for GD, have no psychiatric comorbidity (eg, schizophrenia, body dysmorphic disorder, or uncontrolled bipolar disorder) likely to interfere with treatment, understand the expected outcomes and the social benefits and risks, and have indicated a willingness to take the hormones responsibly.

Historically, patients were required to have a documented real-life experience, defined as having fully adopted the new gender role in everyday life for at least three months.10,11 This model has fallen out of favor, however, as it is unsupported by evidence and may place transgender individuals at physical and emotional risk. Instead, readiness is confirmed by obtaining informed consent.12

Puberty may be suppressed with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist in adolescents who have a GD diagnosis and are at Tanner stage 2 to 3 of puberty until age 16. At that point, hormone therapy consistent with their gender identification may be initiated (see “How to Help Transgender Teens”).11

Beginning the transition

The transitioning process is a complex and individualized journey that can include inward or outward change, or both.

For patients interested in medical interventions, possible therapies include cross-sex hormone administration and gender-affirming surgery. Both are aimed at making the physical and the psychologic more congruent. Hormone treatment (see Table 2) is often essential to reduce the distress of individuals with GD and to help them feel comfortable in their own body.10,11,21 Psychologic conditions, such as depression, tend to improve as the transitioning process gets underway.22

FEMALE-TO-MALE TRANSITION

CASE 1 Jennie R, a 55-year-old postmenopausal patient, comes to your office for an annual exam. Although you’ve been her primary care provider for several years, she confides for the first time that she has never been comfortable as a woman. “I’ve always felt that my body didn’t belong to me,” the patient admits, and goes on to say that for the past several years she has been living as a man. Jennie R says she is ready to start hormone therapy to assist with the gender transition and asks about the process, the benefits and risks, and how quickly she can expect to achieve the desired results.

If Jennie R were your patient, how would you respond?

Masculinizing hormone treatment

As you would explain to a patient like Jennie R, the goal of hormone therapy is to suppress the effects of the sex assigned at birth and replace them with those of the desired gender. In the case of a female transitioning to a male (known as a transman), masculinizing hormones would promote growth of facial and body hair, cessation of menses, increased muscle mass, deepening of the voice, and clitoral enlargement.

Physical changes induced by masculinizing hormone therapy have an expected onset of one to six months and achieve maximum effect in approximately two to five years.10,11 Although there have been no controlled clinical trials evaluating the safety or efficacy of any transitional hormone regimen, WPATH and the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California, San Francisco, suggest initiating intramuscular or transdermal testosterone at increasing doses until normal physiologic male testosterone levels between 350 and 700 ng/dL are achieved, or until cessation of menses.13,25-28 The dose at which either, or both, occur should be continued as long-term maintenance therapy. Medroxyprogesterone can be added, if necessary for menstrual cessation, and a GnRH agonist or endometrial ablation can be used for refractory uterine bleeding.29,30

Testosterone is not a contraceptive. It is important to emphasize to transmen like Jennie that they remain at risk for pregnancy if they are having sex with fertile males. Caution patients not to assume that the possibility of pregnancy ends when menses stop.

Treat minor adverse effects. Adverse effects of masculinizing hormones include vaginal atrophy, fat redistribution and weight gain, polycythemia, acne, scalp hair loss, sleep apnea, elevated liver enzymes, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and bone density loss. Increased risk for cancer of the female organs has not been proven.10,11 It is reasonable to treat minor adverse effects after reviewing the risks/benefits of doing so, as discontinuing hormone therapy could be detrimental to the well-being of transitioning patients.11

There are absolute contraindications to masculinizing hormone therapy, however, including pregnancy, unstable coronary artery disease, and untreated polycythemia with a hematocrit > 55%.10

Monitoring is essential. Patients receiving masculinizing hormone therapy should be monitored every three months during the first year and once or twice a year thereafter, with a focused history (including mood symptoms), physical exam (including weight and blood pressure), and labs (including complete blood count, liver function, renal function, and lipids) at each visit.11,23 Some clinicians also check estradiol levels until they fall below 50 pg/mL,23,27 while others take the cessation of uterine bleeding for > 6 months as an indicator of estrogen suppression.

Preventive health measures continue. Routine screening should continue, based on the patient’s assigned sex at birth. Thus, a transman who has not had a hysterectomy still needs Pap smears, mammograms if the patient has not had a double mastectomy, and bone mineral density (BMD) testing to screen for osteoporosis.31,32 Some experts recommend starting to test BMD at age 50 for patients receiving masculinizing hormones, given the unknown effect of testosterone on bone density.11,31,32

CASE 1 The first question for a transgender patient is about his or her current gender identity, but Jennie R has already reported living as a man. So you start by asking “What name do you prefer to use?” and “Do you prefer to be referred to with male or female pronouns?”

The patient tells you that he sees himself as a man, he wants to be called Jeff, and he prefers male pronouns. You explain that you believe he has gender dysphoria and would benefit from hormone therapy, but it is important to confirm this diagnosis with an MHP. You explain that testosterone can be prescribed for masculinizing effects, and describe the expected effects—more facial and body hair, a deeper voice, and greater muscle mass, among others—and review the likely time frame.

You also discuss the risks of masculinizing hormones (hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and loss of bone density) that will need to be monitored. Before he leaves, you give him the name of an MHP who is experienced in transgender care and tell him to make a follow-up appointment with you after he has seen her. At the conclusion of the visit, you make a note of the patient’s name and gender identity in the chart and inform the staff of the changes.

MALE-TO-FEMALE TRANSITION

CASE 2 Before heading into your office to talk to a new patient named Carl S, you glance at his chart and see that he is a healthy 21-year-old who has come in for a routine physical. When you enter the room, you find Carl wearing a dress, heels, and make-up. After confirming that you have the right patient, you ask, “What is your current gender identity?” “Female,” says Carl, who indicates that she now goes by Carol. The patient has no medical problems, surgical history, or significant family history but reports that she has been taking spironolactone and estrogen for the past three years. Carol also says she has a new female partner and is having unprotected sexual activity.

Feminizing hormone treatment

The desired effects of feminizing hormones include voice change, decreased hair growth, breast growth, body fat redistribution, decreased muscle mass, skin softening, decreased oiliness of skin and hair, and a decrease in spontaneous erections, testicular volume, and sperm production.10,11 The onset of feminizing effects ranges from one month to one year and the expected maximum effect occurs anywhere between three months and five years.10,11 Regimens usually include anti-androgen agents and estrogen.13,26-28

The medications that have been most studied with anti-androgenic effects include spironolactone and 5-α reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) such as finasteride. Spironolactone inhibits testosterone secretion and inhibits androgen binding to androgen receptors; 5-ARIs block the conversion of testosterone to 5-α-dihydrotestosterone, the more active form.

Estrogen can be administered via oral, sublingual, transdermal, or intramuscular route, but parenteral formulations are preferred to avoid first-pass metabolism. The serum estradiol target is similar to the mean daily level of premenopausal women (< 200 pg/mL) and the level of testosterone should be in the normal female range (< 55 ng/dL).13,26-28

The selection of medications should be individualized for each patient. Comorbidities must be considered, as well as the risk for adverse effects, which include venous thromboembolism, elevated liver enzymes, breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hyperprolactinemia, weight gain, gallstones, cerebrovascular disease, and severe migraine headaches.10,11 Estrogen therapy is not reported to induce hypertrophy or premalignant changes in the prostate.33 As is the case for masculinizing hormones, feminizing hormone therapy should be continued indefinitely for long-term effects.

Frequent monitoring is recommended. Patients taking feminizing hormones (transwomen) should be seen every two to three months in the first year and monitored once or twice a year thereafter. Serum testosterone and estradiol levels should initially be monitored every three months; serum electrolytes, specifically potassium, should be monitored every two to three months in the first year until stable.

CASE 2 You recommend that Carol S be screened annually for sexually transmitted diseases, as you would for any 21-year-old patient. You point out, too, that while estrogen and androgen-suppressing therapy decrease sperm production, there is a possibility that the patient could impregnate a female partner and recommend that contraception be used if the couple is not trying to conceive.

You also discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and reasonable expectations of continued treatment. You ask Carol to schedule a follow-up visit in six months, as her hormone regimen is stable. Finally, if the patient remains on hormone therapy, you mention that the only screening unique to men transitioning to women is for breast cancer, which should begin at age 40 to 50 (as it should for all women).

Gender-affirming surgical options

Surgical management of transgender patients is not within the scope of family medicine. But it is essential to know what procedures are available, as you may have occasion to advocate for patients during the surgical referral process and possibly to provide postoperative care.

For transmen, surgical options include chest reconstruction, hysterectomy/oophorectomy, metoidioplasty (using the clitoris to surgically approximate a penis), phalloplasty, scrotoplasty, urethroplasty, and vaginectomy.10,34 The surgeries available for transwomen are orchiectomy, vaginoplasty, penectomy, breast augmentation, thyroid chondroplasty and voice surgery, and facial feminization.10,34 Keep in mind that not all transgender individuals desire surgery as part of the transitioning process.

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Michelle Forcier, MD, MPH, and Karen S. Bernstein, MD, MPH, in the preparation of this manuscript.

Civil rights for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population have advanced markedly in the past decade, and the medical community has gradually begun to address more of their health concerns. More recently, media attention to transgender individuals has encouraged many more to openly seek care.1,2

It is estimated that anywhere from 0.3% to 5% of the US population identifies as transgender.1-3 While awareness of this population has slowly increased, there is a paucity of research on the hormone treatment that is often essential to patients’ well-being. Studies of surgical options for transgender patients have been minimal, as well.

Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to coordinate medical services and ensure continuity of care for transgender patients as they strive to become their authentic selves. Our goal in writing this article is to equip you with the tools to provide this patient population with sensitive, high-quality care (see Table 1).4-7 Our focus is on the diagnosis of gender dysphoria (GD) and its medical and hormonal management—the realm of primary care providers. We briefly discuss surgical management of GD, as well.

UNDERSTANDING AND DIAGNOSING GENDER DYSPHORIA

Two classification systems are used for diagnoses related to GD: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Ed (DSM-5)8 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Rev (ICD-10).9

ICD-10 criteria use the term gender identity disorder; DSM-5 refers to gender dysphoria instead. It is important to emphasize that these classification systems represent an attempt to categorize a group of signs and symptoms that lead to distress for the patient and are not meant to suggest that being transgender is pathological. In fact, in DSM-5—released in 2013—the American Psychiatric Association revised the terminology to emphasize that such individuals are not “disordered” by the nature of their identity, but rather by the distress that being transgender causes.8

For a diagnosis of GD in children, DSM-5 criteria include characteristics perceived to be incongruent between the child’s sex at birth and the self-identified gender based on preferred activities or dislike of his or her own sexual anatomy. The child must meet six or more of the following for at least six months

- A repeatedly stated desire to be, or insistence that he or she is, of the other gender

- In boys, a preference for cross-dressing or simulating female attire; in girls, insistence on wearing only stereotypical masculine clothing

- Strong and persistent preferences for cross-gender roles in make-believe play or fantasy

- A strong rejection of toys/games typically associated with the child’s sex

- Intense desire to participate in stereotypical games and pastimes of the other gender

- Strong preference for playmates of the other gender

- A strong dislike of one’s sexual anatomy

- A strong desire for the primary (eg, penis or vagina) or secondary (eg, menstruation) sex characteristics of the other gender.8

Adolescents and adults must meet two or more of the following for at least six months

- A noticeable incongruence between the gender that the patient sees themselves as and their sex characteristics

- An intense need to do away with (or prevent) his or her primary or secondary sex features

- An intense desire to have the primary and/or secondary sex features of the other gender

- A deep desire to transform into another gender

- A profound need for society to treat them as someone of the other gender

- A powerful assurance of having the characteristic feelings and responses of the other gender.8

For children as well as adolescents and adults, the condition should cause the patient significant distress or significantly affect him or her socially, at work or school, and in other important areas of life.8

Is the patient a candidate for hormone therapy?

Two primary sources—Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7, issued by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)10 and Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual Persons11 by the Endocrine Society—offer clinical practice guidance based on evidence and expert opinion.

WPATH recommends that a mental health professional (MHP) experienced in transgender care diagnose GD to ensure that it is not mistaken for a psychiatric condition manifesting as altered gender identity. However, if no one with such experience is available or accessible in the region, it is reasonable for a primary care provider to make the diagnosis and consider initiating hormone therapy without a mental health referral,12 as the expected benefits outweigh the risks of nontreatment.13

Whether or not an MHP confirms a diagnosis of GD, it is still up to the treating provider to confirm the patient’s eligibility and readiness for hormone therapy: He or she should meet DSM-5 or ICD-10 criteria for GD, have no psychiatric comorbidity (eg, schizophrenia, body dysmorphic disorder, or uncontrolled bipolar disorder) likely to interfere with treatment, understand the expected outcomes and the social benefits and risks, and have indicated a willingness to take the hormones responsibly.

Historically, patients were required to have a documented real-life experience, defined as having fully adopted the new gender role in everyday life for at least three months.10,11 This model has fallen out of favor, however, as it is unsupported by evidence and may place transgender individuals at physical and emotional risk. Instead, readiness is confirmed by obtaining informed consent.12

Puberty may be suppressed with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist in adolescents who have a GD diagnosis and are at Tanner stage 2 to 3 of puberty until age 16. At that point, hormone therapy consistent with their gender identification may be initiated (see “How to Help Transgender Teens”).11

Beginning the transition

The transitioning process is a complex and individualized journey that can include inward or outward change, or both.

For patients interested in medical interventions, possible therapies include cross-sex hormone administration and gender-affirming surgery. Both are aimed at making the physical and the psychologic more congruent. Hormone treatment (see Table 2) is often essential to reduce the distress of individuals with GD and to help them feel comfortable in their own body.10,11,21 Psychologic conditions, such as depression, tend to improve as the transitioning process gets underway.22

FEMALE-TO-MALE TRANSITION

CASE 1 Jennie R, a 55-year-old postmenopausal patient, comes to your office for an annual exam. Although you’ve been her primary care provider for several years, she confides for the first time that she has never been comfortable as a woman. “I’ve always felt that my body didn’t belong to me,” the patient admits, and goes on to say that for the past several years she has been living as a man. Jennie R says she is ready to start hormone therapy to assist with the gender transition and asks about the process, the benefits and risks, and how quickly she can expect to achieve the desired results.

If Jennie R were your patient, how would you respond?

Masculinizing hormone treatment