User login

Respiratory artifact: A second vital sign on the electrocardiogram

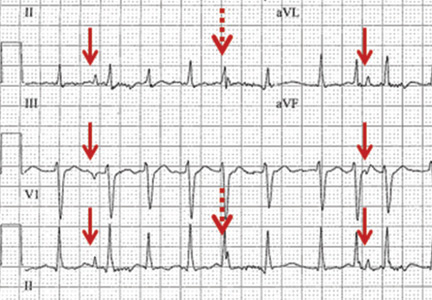

A 57-year-old man hospitalized for treatment of multilobar pneumonia was noted to have a rapid, irregular heart rate on telemetry. He was hypoxemic and appeared to be in respiratory distress. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, as well as what looked like distinct and regular P waves dissociated from the QRS complexes at a rate of about 44/min (Figure 1). What is the explanation and clinical significance of this curious finding?

What appear to be dissociated P waves actually represent respiratory artifact.1–3 The sharp deflections mimicking P waves signify the tonic initiation of inspiratory effort; the subsequent brief periods of low-amplitude, high-frequency micro-oscillations represent surface electrical activity associated with the increased force of the accessory muscles of respiration.1–3

Surface electromyography noninvasively measures muscle activity using electrodes placed on the skin overlying the muscle.4 Using simultaneously recorded mechanical respiratory waveform tracings, we have previously demonstrated that the repetitive pseudo-P waves followed by micro-oscillations have a close temporal relationship with the inspiratory phase of respiration.3 The presence of respiratory artifact indicates a high-risk state frequently necessitating ventilation support.

In addition, when present, respiratory artifact can be viewed as the “second vital sign” on the ECG, the first vital sign being the heart rate. The respiratory rate can be approximated by counting the number of respiratory artifacts in a 10-second recording and multiplying it by 6. A more accurate rate assessment is achieved by measuring 1 or more respiratory artifact cycles in millimeters and then dividing that number into 1,500 or its multiples.3 Based on these calculations, the respiratory rate in this patient was 44/min.

The presence of two atrial rhythms on the same ECG, one not disturbing the other, is consistent with the diagnosis of atrial dissociation.5 Atrial dissociation is a common finding in cardiac transplant recipients in whom the transplantation was performed using atrio-atrial anastomosis.6 Most other cases of apparent atrial dissociation described in the old cardiology and critical care literature probably represented unrecognized respiratory artifact.7,8

An ECG from a different patient (Figure 2) demonstrates rapid respiratory artifact that raised awareness of severe respiratory failure. The respiratory rate calculated from spacing of the pseudo-P waves is 62/min, confirmed by simultaneous respirography.

A FREQUENT FINDING IN SICK HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

Respiratory artifact is a frequent finding in sick hospitalized patients.3 Most commonly, it manifests as repetitive micro-oscillations.3 Pseudo-P waves, as in this 57-year-old patient, are less often observed; but if their origin is not recognized, the interpretation of the ECG can become puzzling.1–3,7,8

Respiratory artifact is a marker of increased work of breathing and a strong indicator of significant cardiopulmonary compromise. Improvement in the patient’s cardiac or respiratory condition is typically associated with a decrease in the rate or complete elimination of respiratory artifact.3

Recognition of rapid respiratory artifact is less important in critical care units, where patients’ vital signs and cardiorespiratory status are carefully observed. However, in hospital settings where respiratory rate and oxygen saturation are not continuously monitored, recognizing rapid respiratory artifact can help raise awareness of the possibility of severe respiratory distress.

- Higgins TG, Phillips JH Jr, Sumner RG. Atrial dissociation: an electrocardiographic artifact produced by the accessory muscles of respiration. Am J Cardiol 1966; 18:132–139.

- Cheriex EC, Brugada P, Wellens HJ. Pseudo-atrial dissociation: a respiratory artifact. Eur Heart J 1986; 7:357–359.

- Littmann L, Rennyson SL, Wall BP, Parker JM. Significance of respiratory artifact in the electrocardiogram. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102:1090–1096.

- Pullman SL, Goodin DS, Marquinez AI, Tabbal S, Rubin M. Clinical utility of surface EMG: report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:171–177.

- Chung EK. A reappraisal of atrial dissociation. Am J Cardiol 1971; 28:111–117.

- Stinson EB, Schroeder JS, Griepp RB, Shumway NE, Dong E Jr. Observations on the behavior of recipient atria after cardiac transplantation in man. Am J Cardiol 1972; 30:615–622.

- Cohen J, Scherf D. Complete interatrial and intra-atrial block (atrial dissociation). Am Heart J 1965; 70:23–34.

- Chung KY, Walsh TJ, Massie E. A review of atrial dissociation, with illustrative cases and critical discussion. Am J Med Sci 1965; 250:72–78.

A 57-year-old man hospitalized for treatment of multilobar pneumonia was noted to have a rapid, irregular heart rate on telemetry. He was hypoxemic and appeared to be in respiratory distress. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, as well as what looked like distinct and regular P waves dissociated from the QRS complexes at a rate of about 44/min (Figure 1). What is the explanation and clinical significance of this curious finding?

What appear to be dissociated P waves actually represent respiratory artifact.1–3 The sharp deflections mimicking P waves signify the tonic initiation of inspiratory effort; the subsequent brief periods of low-amplitude, high-frequency micro-oscillations represent surface electrical activity associated with the increased force of the accessory muscles of respiration.1–3

Surface electromyography noninvasively measures muscle activity using electrodes placed on the skin overlying the muscle.4 Using simultaneously recorded mechanical respiratory waveform tracings, we have previously demonstrated that the repetitive pseudo-P waves followed by micro-oscillations have a close temporal relationship with the inspiratory phase of respiration.3 The presence of respiratory artifact indicates a high-risk state frequently necessitating ventilation support.

In addition, when present, respiratory artifact can be viewed as the “second vital sign” on the ECG, the first vital sign being the heart rate. The respiratory rate can be approximated by counting the number of respiratory artifacts in a 10-second recording and multiplying it by 6. A more accurate rate assessment is achieved by measuring 1 or more respiratory artifact cycles in millimeters and then dividing that number into 1,500 or its multiples.3 Based on these calculations, the respiratory rate in this patient was 44/min.

The presence of two atrial rhythms on the same ECG, one not disturbing the other, is consistent with the diagnosis of atrial dissociation.5 Atrial dissociation is a common finding in cardiac transplant recipients in whom the transplantation was performed using atrio-atrial anastomosis.6 Most other cases of apparent atrial dissociation described in the old cardiology and critical care literature probably represented unrecognized respiratory artifact.7,8

An ECG from a different patient (Figure 2) demonstrates rapid respiratory artifact that raised awareness of severe respiratory failure. The respiratory rate calculated from spacing of the pseudo-P waves is 62/min, confirmed by simultaneous respirography.

A FREQUENT FINDING IN SICK HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

Respiratory artifact is a frequent finding in sick hospitalized patients.3 Most commonly, it manifests as repetitive micro-oscillations.3 Pseudo-P waves, as in this 57-year-old patient, are less often observed; but if their origin is not recognized, the interpretation of the ECG can become puzzling.1–3,7,8

Respiratory artifact is a marker of increased work of breathing and a strong indicator of significant cardiopulmonary compromise. Improvement in the patient’s cardiac or respiratory condition is typically associated with a decrease in the rate or complete elimination of respiratory artifact.3

Recognition of rapid respiratory artifact is less important in critical care units, where patients’ vital signs and cardiorespiratory status are carefully observed. However, in hospital settings where respiratory rate and oxygen saturation are not continuously monitored, recognizing rapid respiratory artifact can help raise awareness of the possibility of severe respiratory distress.

A 57-year-old man hospitalized for treatment of multilobar pneumonia was noted to have a rapid, irregular heart rate on telemetry. He was hypoxemic and appeared to be in respiratory distress. A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, as well as what looked like distinct and regular P waves dissociated from the QRS complexes at a rate of about 44/min (Figure 1). What is the explanation and clinical significance of this curious finding?

What appear to be dissociated P waves actually represent respiratory artifact.1–3 The sharp deflections mimicking P waves signify the tonic initiation of inspiratory effort; the subsequent brief periods of low-amplitude, high-frequency micro-oscillations represent surface electrical activity associated with the increased force of the accessory muscles of respiration.1–3

Surface electromyography noninvasively measures muscle activity using electrodes placed on the skin overlying the muscle.4 Using simultaneously recorded mechanical respiratory waveform tracings, we have previously demonstrated that the repetitive pseudo-P waves followed by micro-oscillations have a close temporal relationship with the inspiratory phase of respiration.3 The presence of respiratory artifact indicates a high-risk state frequently necessitating ventilation support.

In addition, when present, respiratory artifact can be viewed as the “second vital sign” on the ECG, the first vital sign being the heart rate. The respiratory rate can be approximated by counting the number of respiratory artifacts in a 10-second recording and multiplying it by 6. A more accurate rate assessment is achieved by measuring 1 or more respiratory artifact cycles in millimeters and then dividing that number into 1,500 or its multiples.3 Based on these calculations, the respiratory rate in this patient was 44/min.

The presence of two atrial rhythms on the same ECG, one not disturbing the other, is consistent with the diagnosis of atrial dissociation.5 Atrial dissociation is a common finding in cardiac transplant recipients in whom the transplantation was performed using atrio-atrial anastomosis.6 Most other cases of apparent atrial dissociation described in the old cardiology and critical care literature probably represented unrecognized respiratory artifact.7,8

An ECG from a different patient (Figure 2) demonstrates rapid respiratory artifact that raised awareness of severe respiratory failure. The respiratory rate calculated from spacing of the pseudo-P waves is 62/min, confirmed by simultaneous respirography.

A FREQUENT FINDING IN SICK HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

Respiratory artifact is a frequent finding in sick hospitalized patients.3 Most commonly, it manifests as repetitive micro-oscillations.3 Pseudo-P waves, as in this 57-year-old patient, are less often observed; but if their origin is not recognized, the interpretation of the ECG can become puzzling.1–3,7,8

Respiratory artifact is a marker of increased work of breathing and a strong indicator of significant cardiopulmonary compromise. Improvement in the patient’s cardiac or respiratory condition is typically associated with a decrease in the rate or complete elimination of respiratory artifact.3

Recognition of rapid respiratory artifact is less important in critical care units, where patients’ vital signs and cardiorespiratory status are carefully observed. However, in hospital settings where respiratory rate and oxygen saturation are not continuously monitored, recognizing rapid respiratory artifact can help raise awareness of the possibility of severe respiratory distress.

- Higgins TG, Phillips JH Jr, Sumner RG. Atrial dissociation: an electrocardiographic artifact produced by the accessory muscles of respiration. Am J Cardiol 1966; 18:132–139.

- Cheriex EC, Brugada P, Wellens HJ. Pseudo-atrial dissociation: a respiratory artifact. Eur Heart J 1986; 7:357–359.

- Littmann L, Rennyson SL, Wall BP, Parker JM. Significance of respiratory artifact in the electrocardiogram. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102:1090–1096.

- Pullman SL, Goodin DS, Marquinez AI, Tabbal S, Rubin M. Clinical utility of surface EMG: report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:171–177.

- Chung EK. A reappraisal of atrial dissociation. Am J Cardiol 1971; 28:111–117.

- Stinson EB, Schroeder JS, Griepp RB, Shumway NE, Dong E Jr. Observations on the behavior of recipient atria after cardiac transplantation in man. Am J Cardiol 1972; 30:615–622.

- Cohen J, Scherf D. Complete interatrial and intra-atrial block (atrial dissociation). Am Heart J 1965; 70:23–34.

- Chung KY, Walsh TJ, Massie E. A review of atrial dissociation, with illustrative cases and critical discussion. Am J Med Sci 1965; 250:72–78.

- Higgins TG, Phillips JH Jr, Sumner RG. Atrial dissociation: an electrocardiographic artifact produced by the accessory muscles of respiration. Am J Cardiol 1966; 18:132–139.

- Cheriex EC, Brugada P, Wellens HJ. Pseudo-atrial dissociation: a respiratory artifact. Eur Heart J 1986; 7:357–359.

- Littmann L, Rennyson SL, Wall BP, Parker JM. Significance of respiratory artifact in the electrocardiogram. Am J Cardiol 2008; 102:1090–1096.

- Pullman SL, Goodin DS, Marquinez AI, Tabbal S, Rubin M. Clinical utility of surface EMG: report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:171–177.

- Chung EK. A reappraisal of atrial dissociation. Am J Cardiol 1971; 28:111–117.

- Stinson EB, Schroeder JS, Griepp RB, Shumway NE, Dong E Jr. Observations on the behavior of recipient atria after cardiac transplantation in man. Am J Cardiol 1972; 30:615–622.

- Cohen J, Scherf D. Complete interatrial and intra-atrial block (atrial dissociation). Am Heart J 1965; 70:23–34.

- Chung KY, Walsh TJ, Massie E. A review of atrial dissociation, with illustrative cases and critical discussion. Am J Med Sci 1965; 250:72–78.

Wide QRS complex rhythm with pulseless electrical activity

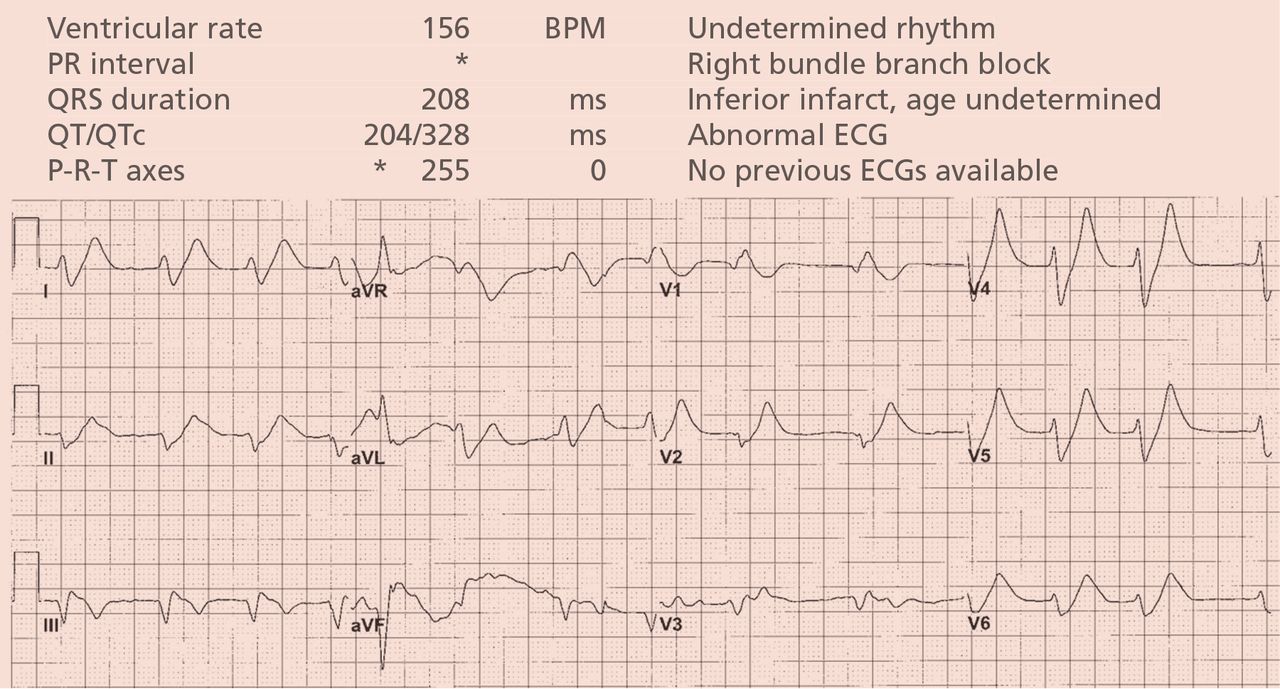

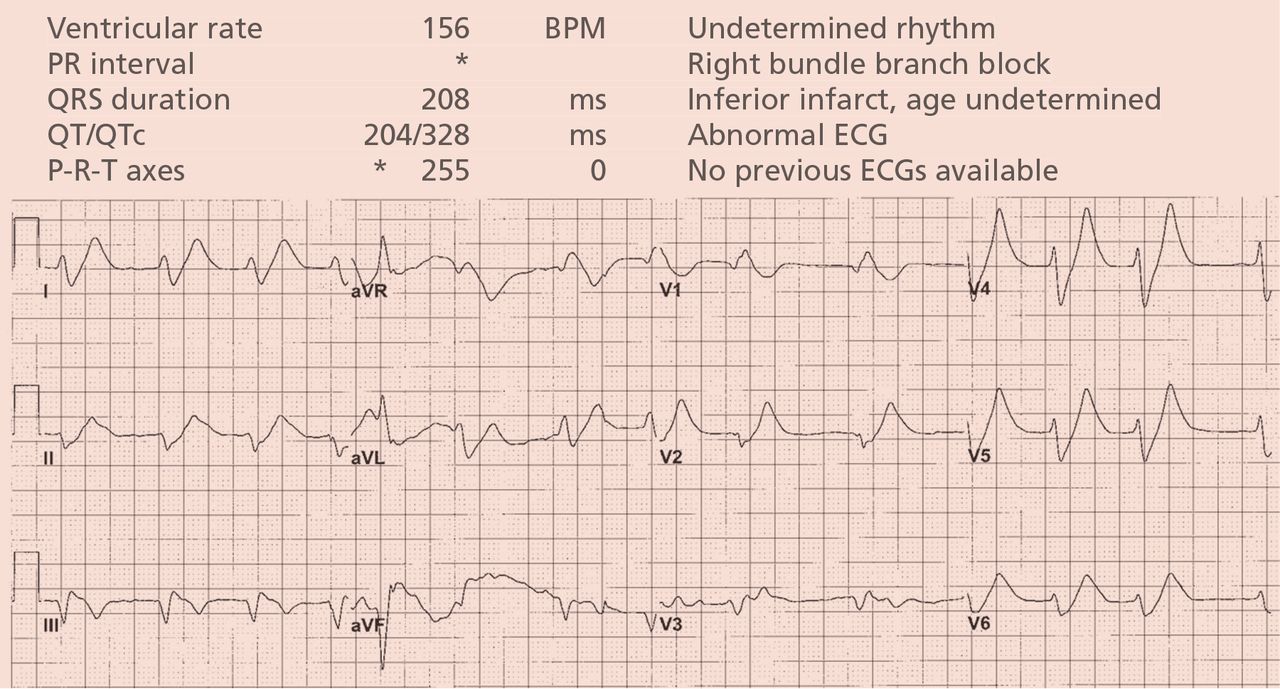

A 64-year-old man with chronic kidney disease and recent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage suffered pulseless electrical activity and cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started, with three attempted but failed electrical cardioversions. Return of spontaneous circulation required prolonged resuscitation efforts, including multiple rounds of epinephrine, calcium, and sodium bicarbonate. The standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1) showed an irregular wide-QRS-complex rhythm, with right bundle branch block and right-superior-axis deviation.

What was the cause of the pulseless electrical activity and the features on the electrocardiogram?

The presentation of cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity usually has a grave prognosis, and in the acute setting, the cause may be difficult to establish. However, several conditions that cause this presentation have treatments that, applied immediately, can lead to quick and sustained recovery.1

Electrocardiography can be a powerful tool in the urgent evaluation of pulseless electrical activity.2,3 Narrow-QRS-complex pulseless electrical activity is often caused by mechanical factors such as cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, and major hemorrhage.3 Pulseless electrical activity associated with a wide QRS complex and marked axis deviation, as in this patient, is usually the result of a metabolic abnormality, most often hyperkalemia3; additional indicators of severe hyperkalemia include ST-segment elevation in the anterior chest leads (including the Brugada pattern4) and, as in this patient, “double counting” of the heart rate by the interpretation software (Figure 1).5,6

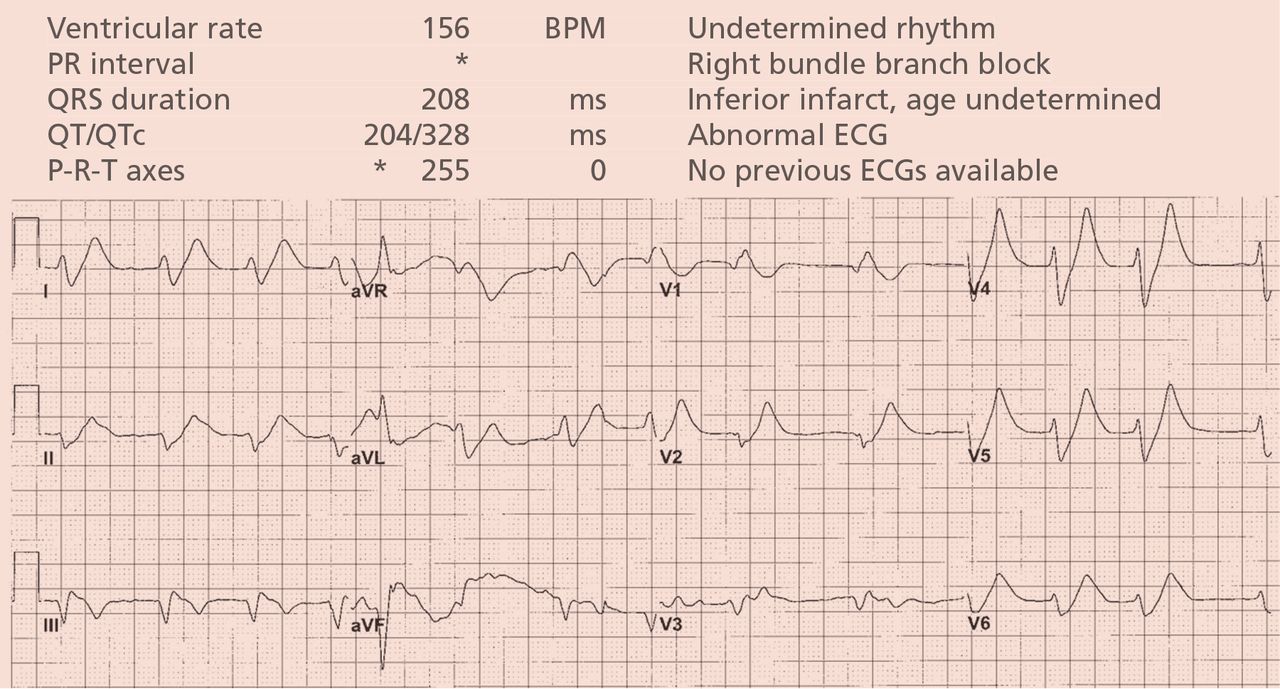

Based on the suspicion of a metabolic cause, the serum potassium was tested and was 8.9 mmol/L (reference range 3.5–5.0). The patient was given intravenous calcium, sodium bicarbonate, glucose, and insulin, and 2 hours later the serum potassium had decreased to 7.1 mmol/L. At that time, the electrocardiogram (Figure 2) showed a regular rhythm with ectopic P waves, probably an ectopic atrial tachycardia. There were now narrow QRS complexes with J-point depression, upsloping ST segments, and tall, hyperacute T waves in the chest leads—a pattern recently described in proximal left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion.7 The electrocardiographic similarities in hyperkalemia and acute myocardial infarction are probably the result of potassium accumulation in the ischemic myocardium associated with acute coronary occlusion.7

The patient had a full recovery, both clinically and on electrocardiography.

- Saarinen S, Nurmi J, Toivio T, Fredman D, Virkkunen I, Castrén M. Does appropriate treatment of the primary underlying cause of PEA during resuscitation improve patients’ survival? Resuscitation 2012; 83:819–822.

- Mehta C, Brady W. Pulseless electrical activity in cardiac arrest: electrocardiographic presentations and management considerations based on the electrocardiogram. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30:236–239.

- Littmann L, Bustin DJ, Haley MW. A simplified and structured teaching tool for the evaluation and management of pulseless electrical activity. Med Princ Pract 2014; 23:1–6.

- Littmann L, Monroe MH, Taylor L, Brearley WD. The hyperkalemic Brugada sign. J Electrocardiol 2007; 40:53–59.

- Littmann L, Brearley WD, Taylor L, Monroe MH. Double counting of heart rate by interpretation software: a new electrocardiographic sign of severe hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25:584–586.

- Tomcsányi J, Wágner V, Bózsik B. Littmann sign in hyperkalemia: double counting of heart rate. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25:1077–1078.

- de Winter RJ, Verouden NJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA; Interventional Cardiology Group of the Academic Medical Center. A new ECG sign of proximal LAD occlusion. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2071–2073.

A 64-year-old man with chronic kidney disease and recent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage suffered pulseless electrical activity and cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started, with three attempted but failed electrical cardioversions. Return of spontaneous circulation required prolonged resuscitation efforts, including multiple rounds of epinephrine, calcium, and sodium bicarbonate. The standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1) showed an irregular wide-QRS-complex rhythm, with right bundle branch block and right-superior-axis deviation.

What was the cause of the pulseless electrical activity and the features on the electrocardiogram?

The presentation of cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity usually has a grave prognosis, and in the acute setting, the cause may be difficult to establish. However, several conditions that cause this presentation have treatments that, applied immediately, can lead to quick and sustained recovery.1

Electrocardiography can be a powerful tool in the urgent evaluation of pulseless electrical activity.2,3 Narrow-QRS-complex pulseless electrical activity is often caused by mechanical factors such as cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, and major hemorrhage.3 Pulseless electrical activity associated with a wide QRS complex and marked axis deviation, as in this patient, is usually the result of a metabolic abnormality, most often hyperkalemia3; additional indicators of severe hyperkalemia include ST-segment elevation in the anterior chest leads (including the Brugada pattern4) and, as in this patient, “double counting” of the heart rate by the interpretation software (Figure 1).5,6

Based on the suspicion of a metabolic cause, the serum potassium was tested and was 8.9 mmol/L (reference range 3.5–5.0). The patient was given intravenous calcium, sodium bicarbonate, glucose, and insulin, and 2 hours later the serum potassium had decreased to 7.1 mmol/L. At that time, the electrocardiogram (Figure 2) showed a regular rhythm with ectopic P waves, probably an ectopic atrial tachycardia. There were now narrow QRS complexes with J-point depression, upsloping ST segments, and tall, hyperacute T waves in the chest leads—a pattern recently described in proximal left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion.7 The electrocardiographic similarities in hyperkalemia and acute myocardial infarction are probably the result of potassium accumulation in the ischemic myocardium associated with acute coronary occlusion.7

The patient had a full recovery, both clinically and on electrocardiography.

A 64-year-old man with chronic kidney disease and recent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage suffered pulseless electrical activity and cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started, with three attempted but failed electrical cardioversions. Return of spontaneous circulation required prolonged resuscitation efforts, including multiple rounds of epinephrine, calcium, and sodium bicarbonate. The standard 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1) showed an irregular wide-QRS-complex rhythm, with right bundle branch block and right-superior-axis deviation.

What was the cause of the pulseless electrical activity and the features on the electrocardiogram?

The presentation of cardiac arrest with pulseless electrical activity usually has a grave prognosis, and in the acute setting, the cause may be difficult to establish. However, several conditions that cause this presentation have treatments that, applied immediately, can lead to quick and sustained recovery.1

Electrocardiography can be a powerful tool in the urgent evaluation of pulseless electrical activity.2,3 Narrow-QRS-complex pulseless electrical activity is often caused by mechanical factors such as cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, and major hemorrhage.3 Pulseless electrical activity associated with a wide QRS complex and marked axis deviation, as in this patient, is usually the result of a metabolic abnormality, most often hyperkalemia3; additional indicators of severe hyperkalemia include ST-segment elevation in the anterior chest leads (including the Brugada pattern4) and, as in this patient, “double counting” of the heart rate by the interpretation software (Figure 1).5,6

Based on the suspicion of a metabolic cause, the serum potassium was tested and was 8.9 mmol/L (reference range 3.5–5.0). The patient was given intravenous calcium, sodium bicarbonate, glucose, and insulin, and 2 hours later the serum potassium had decreased to 7.1 mmol/L. At that time, the electrocardiogram (Figure 2) showed a regular rhythm with ectopic P waves, probably an ectopic atrial tachycardia. There were now narrow QRS complexes with J-point depression, upsloping ST segments, and tall, hyperacute T waves in the chest leads—a pattern recently described in proximal left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion.7 The electrocardiographic similarities in hyperkalemia and acute myocardial infarction are probably the result of potassium accumulation in the ischemic myocardium associated with acute coronary occlusion.7

The patient had a full recovery, both clinically and on electrocardiography.

- Saarinen S, Nurmi J, Toivio T, Fredman D, Virkkunen I, Castrén M. Does appropriate treatment of the primary underlying cause of PEA during resuscitation improve patients’ survival? Resuscitation 2012; 83:819–822.

- Mehta C, Brady W. Pulseless electrical activity in cardiac arrest: electrocardiographic presentations and management considerations based on the electrocardiogram. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30:236–239.

- Littmann L, Bustin DJ, Haley MW. A simplified and structured teaching tool for the evaluation and management of pulseless electrical activity. Med Princ Pract 2014; 23:1–6.

- Littmann L, Monroe MH, Taylor L, Brearley WD. The hyperkalemic Brugada sign. J Electrocardiol 2007; 40:53–59.

- Littmann L, Brearley WD, Taylor L, Monroe MH. Double counting of heart rate by interpretation software: a new electrocardiographic sign of severe hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25:584–586.

- Tomcsányi J, Wágner V, Bózsik B. Littmann sign in hyperkalemia: double counting of heart rate. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25:1077–1078.

- de Winter RJ, Verouden NJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA; Interventional Cardiology Group of the Academic Medical Center. A new ECG sign of proximal LAD occlusion. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2071–2073.

- Saarinen S, Nurmi J, Toivio T, Fredman D, Virkkunen I, Castrén M. Does appropriate treatment of the primary underlying cause of PEA during resuscitation improve patients’ survival? Resuscitation 2012; 83:819–822.

- Mehta C, Brady W. Pulseless electrical activity in cardiac arrest: electrocardiographic presentations and management considerations based on the electrocardiogram. Am J Emerg Med 2012; 30:236–239.

- Littmann L, Bustin DJ, Haley MW. A simplified and structured teaching tool for the evaluation and management of pulseless electrical activity. Med Princ Pract 2014; 23:1–6.

- Littmann L, Monroe MH, Taylor L, Brearley WD. The hyperkalemic Brugada sign. J Electrocardiol 2007; 40:53–59.

- Littmann L, Brearley WD, Taylor L, Monroe MH. Double counting of heart rate by interpretation software: a new electrocardiographic sign of severe hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25:584–586.

- Tomcsányi J, Wágner V, Bózsik B. Littmann sign in hyperkalemia: double counting of heart rate. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25:1077–1078.

- de Winter RJ, Verouden NJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA; Interventional Cardiology Group of the Academic Medical Center. A new ECG sign of proximal LAD occlusion. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2071–2073.