User login

Can extended anticoagulation prophylaxis after discharge prevent thromboembolism?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 67-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and chronic congestive heart failure (ejection fraction = 30%) was admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute hypoxic respiratory failure. He was discharged after 10 days of inpatient treatment that included daily VTE prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Should he go home on VTE prophylaxis?

Patients hospitalized with nonsurgical conditions such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, or active cancers are at increased risk for VTE due to inflammation and immobility. In a US study of 158,325 hospitalized nonsurgical patients, including those with cancer, infections, congestive heart failure, or respiratory failure, 4% of patients developed

However, use of DOACs for short-term VTE prophylaxis as an alternative to LMWH in hospitalized patients is supported by a meta-analysis showing equivalent efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness.1 The current study examined DOACs for extended postdischarge use.1

STUDY SUMMARY

Significant benefit of DOACs demonstrated across 4 large trials

This meta-analysis of 4 large randomized controlled trials examined the safety and efficacy of 6 weeks of postdischarge DOAC thromboprophylaxis compared with placebo in 26,408 high-risk nonsurgical hospitalized patients.1 Patients at least 40 years old were admitted with diagnoses that included New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV congestive heart failure, active cancer, acute ischemic stroke, acute respiratory failure, or infectious or inflammatory disease. Study patients also had risk factors for VTE, including age 75 and older, obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, history of VTE, history of NYHA class III or IV congestive heart failure, history of cancer, thrombophilia, hormone replacement therapy, or major surgery within the 6 to 12 weeks before current medical hospitalization.

Patients were excluded if DOACs were contraindicated or if they had active or recent bleeding, renal failure, abnormal liver values, an upcoming need for surgery, or an indication for ongoing anticoagulation. Patients in 3 studies received 6 to 10 days of enoxaparin as prophylaxis during their inpatient stay. (The fourth study did not specify length of inpatient prophylaxis or drug used.) After discharge, patients were assigned to placebo or a regimen of rivaroxaban 10 mg daily, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, or betrixaban 80 mg daily for a range of 30 to 45 days. The primary outcome was the composite of total VTE and VTE-related death. A secondary outcome was the occurrence of nonfatal symptomatic VTE, and the primary safety outcome was the incidence of major bleeding.

The primary outcome occurred in 2.9% of the patients in the DOAC group compared with 3.6% of patients in the placebo group (odds ratio [OR] = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91; number needed to treat [NNT] = 143). The secondary outcome occurred in 0.48% of patients in the DOAC group compared with 0.77% of patients in the placebo group (OR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.83; NNT = 345). Major bleeding resulting in a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of more than 2 g/L, requiring transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells, reintervention at a previous surgical site, or bleeding in a critical organ or that was fatal, occurred in 0.58% of patients in the DOAC group compared with 0.3% of patients in the placebo group (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7; number needed to harm [NNH] = 357). Nonmajor bleeding was increased in the DOAC group compared with placebo (2.2% vs 1.2%; OR = 1.8; 95% CI, 1.5-2.1; NNH = 110).

The NNT to prevent a fatal VTE was 899 patients

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Mortality and morbidity benefit with small bleeding risk

Based on this study, for every 300 high-risk patients hospitalized with nonsurgical diagnoses who are given 6 weeks of DOAC prophylaxis, there will be 2 fewer cases of VTE and VTE-related death. In this same group of patients, there will be approximately 1 major bleeding event and 3 less serious bleeds.

Patients with preexisting medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, cancer, and sepsis and those admitted to an intensive care unit are at increased risk for DVT after discharge.5 Extending DOAC prophylaxis in nonsurgical patients with serious medical conditions for 6 weeks after discharge reduces the risk of VTE or VTE-related death by 0.7% compared with placebo. Treatment in this population does incur a small increased risk of major bleeding by 0.3% in the DOAC group compared with placebo.

CAVEATS

Results cannot be generalized to all patient populations

Many high-risk patients have chronic kidney disease, and because DOACs (including apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran) are renally cleared, there are limited data to establish their safety in patients with creatinine clearance ≤ 30 mL/min. Benefits seen with DOACs cannot be extrapolated to other anticoagulation agents, including warfarin or LMWH.

In accordance with new guidelines, some of the patients in this study would now receive antiplatelet therapy, eg, poststroke patients, cancer patients, and—with the ease of DOAC use—patients with atrial fibrillation. If these patients were excluded, it is not known whether the benefit would remain. Patients included in these trials were at particularly high risk for VTE, and the benefits seen in this study cannot be generalized to a patient population with fewer VTE risk factors.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

High cost and lack of updated guidelines may limit DOAC thromboprophylaxis

Cost is a concern. All the new DOACs are expensive; for example, rivaroxaban costs a little less than $500 per month.6 Obtaining insurance coverage for a novel indication may be challenging. The American Society of Hematology and others have not yet endorsed extended posthospital thromboprophylaxis in nonsurgical patients, although the use of DOACs has expanded since the last guideline revisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Bhalla V, Lamping OF, Abdel-Latif A, et al. Contemporary meta-analysis of extended direct-acting oral anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis to prevent venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2020;133:1074-1081.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.037

2. Spyropoulos AC, Hussein M, Lin J, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism occurrence in medical patients among the insured population. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:951-957. doi: 10.1160/TH09-02-0073

3. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl):e195S-226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296

4. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3198-3225. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

5. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(suppl):I-4-I-8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

6. Rivaroxaban . GoodRx. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.goodrx.com/rivaroxaban

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 67-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and chronic congestive heart failure (ejection fraction = 30%) was admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute hypoxic respiratory failure. He was discharged after 10 days of inpatient treatment that included daily VTE prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Should he go home on VTE prophylaxis?

Patients hospitalized with nonsurgical conditions such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, or active cancers are at increased risk for VTE due to inflammation and immobility. In a US study of 158,325 hospitalized nonsurgical patients, including those with cancer, infections, congestive heart failure, or respiratory failure, 4% of patients developed

However, use of DOACs for short-term VTE prophylaxis as an alternative to LMWH in hospitalized patients is supported by a meta-analysis showing equivalent efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness.1 The current study examined DOACs for extended postdischarge use.1

STUDY SUMMARY

Significant benefit of DOACs demonstrated across 4 large trials

This meta-analysis of 4 large randomized controlled trials examined the safety and efficacy of 6 weeks of postdischarge DOAC thromboprophylaxis compared with placebo in 26,408 high-risk nonsurgical hospitalized patients.1 Patients at least 40 years old were admitted with diagnoses that included New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV congestive heart failure, active cancer, acute ischemic stroke, acute respiratory failure, or infectious or inflammatory disease. Study patients also had risk factors for VTE, including age 75 and older, obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, history of VTE, history of NYHA class III or IV congestive heart failure, history of cancer, thrombophilia, hormone replacement therapy, or major surgery within the 6 to 12 weeks before current medical hospitalization.

Patients were excluded if DOACs were contraindicated or if they had active or recent bleeding, renal failure, abnormal liver values, an upcoming need for surgery, or an indication for ongoing anticoagulation. Patients in 3 studies received 6 to 10 days of enoxaparin as prophylaxis during their inpatient stay. (The fourth study did not specify length of inpatient prophylaxis or drug used.) After discharge, patients were assigned to placebo or a regimen of rivaroxaban 10 mg daily, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, or betrixaban 80 mg daily for a range of 30 to 45 days. The primary outcome was the composite of total VTE and VTE-related death. A secondary outcome was the occurrence of nonfatal symptomatic VTE, and the primary safety outcome was the incidence of major bleeding.

The primary outcome occurred in 2.9% of the patients in the DOAC group compared with 3.6% of patients in the placebo group (odds ratio [OR] = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91; number needed to treat [NNT] = 143). The secondary outcome occurred in 0.48% of patients in the DOAC group compared with 0.77% of patients in the placebo group (OR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.83; NNT = 345). Major bleeding resulting in a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of more than 2 g/L, requiring transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells, reintervention at a previous surgical site, or bleeding in a critical organ or that was fatal, occurred in 0.58% of patients in the DOAC group compared with 0.3% of patients in the placebo group (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7; number needed to harm [NNH] = 357). Nonmajor bleeding was increased in the DOAC group compared with placebo (2.2% vs 1.2%; OR = 1.8; 95% CI, 1.5-2.1; NNH = 110).

The NNT to prevent a fatal VTE was 899 patients

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Mortality and morbidity benefit with small bleeding risk

Based on this study, for every 300 high-risk patients hospitalized with nonsurgical diagnoses who are given 6 weeks of DOAC prophylaxis, there will be 2 fewer cases of VTE and VTE-related death. In this same group of patients, there will be approximately 1 major bleeding event and 3 less serious bleeds.

Patients with preexisting medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, cancer, and sepsis and those admitted to an intensive care unit are at increased risk for DVT after discharge.5 Extending DOAC prophylaxis in nonsurgical patients with serious medical conditions for 6 weeks after discharge reduces the risk of VTE or VTE-related death by 0.7% compared with placebo. Treatment in this population does incur a small increased risk of major bleeding by 0.3% in the DOAC group compared with placebo.

CAVEATS

Results cannot be generalized to all patient populations

Many high-risk patients have chronic kidney disease, and because DOACs (including apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran) are renally cleared, there are limited data to establish their safety in patients with creatinine clearance ≤ 30 mL/min. Benefits seen with DOACs cannot be extrapolated to other anticoagulation agents, including warfarin or LMWH.

In accordance with new guidelines, some of the patients in this study would now receive antiplatelet therapy, eg, poststroke patients, cancer patients, and—with the ease of DOAC use—patients with atrial fibrillation. If these patients were excluded, it is not known whether the benefit would remain. Patients included in these trials were at particularly high risk for VTE, and the benefits seen in this study cannot be generalized to a patient population with fewer VTE risk factors.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

High cost and lack of updated guidelines may limit DOAC thromboprophylaxis

Cost is a concern. All the new DOACs are expensive; for example, rivaroxaban costs a little less than $500 per month.6 Obtaining insurance coverage for a novel indication may be challenging. The American Society of Hematology and others have not yet endorsed extended posthospital thromboprophylaxis in nonsurgical patients, although the use of DOACs has expanded since the last guideline revisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 67-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and chronic congestive heart failure (ejection fraction = 30%) was admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute hypoxic respiratory failure. He was discharged after 10 days of inpatient treatment that included daily VTE prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). Should he go home on VTE prophylaxis?

Patients hospitalized with nonsurgical conditions such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, or active cancers are at increased risk for VTE due to inflammation and immobility. In a US study of 158,325 hospitalized nonsurgical patients, including those with cancer, infections, congestive heart failure, or respiratory failure, 4% of patients developed

However, use of DOACs for short-term VTE prophylaxis as an alternative to LMWH in hospitalized patients is supported by a meta-analysis showing equivalent efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness.1 The current study examined DOACs for extended postdischarge use.1

STUDY SUMMARY

Significant benefit of DOACs demonstrated across 4 large trials

This meta-analysis of 4 large randomized controlled trials examined the safety and efficacy of 6 weeks of postdischarge DOAC thromboprophylaxis compared with placebo in 26,408 high-risk nonsurgical hospitalized patients.1 Patients at least 40 years old were admitted with diagnoses that included New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV congestive heart failure, active cancer, acute ischemic stroke, acute respiratory failure, or infectious or inflammatory disease. Study patients also had risk factors for VTE, including age 75 and older, obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, history of VTE, history of NYHA class III or IV congestive heart failure, history of cancer, thrombophilia, hormone replacement therapy, or major surgery within the 6 to 12 weeks before current medical hospitalization.

Patients were excluded if DOACs were contraindicated or if they had active or recent bleeding, renal failure, abnormal liver values, an upcoming need for surgery, or an indication for ongoing anticoagulation. Patients in 3 studies received 6 to 10 days of enoxaparin as prophylaxis during their inpatient stay. (The fourth study did not specify length of inpatient prophylaxis or drug used.) After discharge, patients were assigned to placebo or a regimen of rivaroxaban 10 mg daily, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily, or betrixaban 80 mg daily for a range of 30 to 45 days. The primary outcome was the composite of total VTE and VTE-related death. A secondary outcome was the occurrence of nonfatal symptomatic VTE, and the primary safety outcome was the incidence of major bleeding.

The primary outcome occurred in 2.9% of the patients in the DOAC group compared with 3.6% of patients in the placebo group (odds ratio [OR] = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91; number needed to treat [NNT] = 143). The secondary outcome occurred in 0.48% of patients in the DOAC group compared with 0.77% of patients in the placebo group (OR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.83; NNT = 345). Major bleeding resulting in a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of more than 2 g/L, requiring transfusion of at least 2 units of packed red blood cells, reintervention at a previous surgical site, or bleeding in a critical organ or that was fatal, occurred in 0.58% of patients in the DOAC group compared with 0.3% of patients in the placebo group (OR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4-2.7; number needed to harm [NNH] = 357). Nonmajor bleeding was increased in the DOAC group compared with placebo (2.2% vs 1.2%; OR = 1.8; 95% CI, 1.5-2.1; NNH = 110).

The NNT to prevent a fatal VTE was 899 patients

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Mortality and morbidity benefit with small bleeding risk

Based on this study, for every 300 high-risk patients hospitalized with nonsurgical diagnoses who are given 6 weeks of DOAC prophylaxis, there will be 2 fewer cases of VTE and VTE-related death. In this same group of patients, there will be approximately 1 major bleeding event and 3 less serious bleeds.

Patients with preexisting medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, cancer, and sepsis and those admitted to an intensive care unit are at increased risk for DVT after discharge.5 Extending DOAC prophylaxis in nonsurgical patients with serious medical conditions for 6 weeks after discharge reduces the risk of VTE or VTE-related death by 0.7% compared with placebo. Treatment in this population does incur a small increased risk of major bleeding by 0.3% in the DOAC group compared with placebo.

CAVEATS

Results cannot be generalized to all patient populations

Many high-risk patients have chronic kidney disease, and because DOACs (including apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran) are renally cleared, there are limited data to establish their safety in patients with creatinine clearance ≤ 30 mL/min. Benefits seen with DOACs cannot be extrapolated to other anticoagulation agents, including warfarin or LMWH.

In accordance with new guidelines, some of the patients in this study would now receive antiplatelet therapy, eg, poststroke patients, cancer patients, and—with the ease of DOAC use—patients with atrial fibrillation. If these patients were excluded, it is not known whether the benefit would remain. Patients included in these trials were at particularly high risk for VTE, and the benefits seen in this study cannot be generalized to a patient population with fewer VTE risk factors.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

High cost and lack of updated guidelines may limit DOAC thromboprophylaxis

Cost is a concern. All the new DOACs are expensive; for example, rivaroxaban costs a little less than $500 per month.6 Obtaining insurance coverage for a novel indication may be challenging. The American Society of Hematology and others have not yet endorsed extended posthospital thromboprophylaxis in nonsurgical patients, although the use of DOACs has expanded since the last guideline revisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Bhalla V, Lamping OF, Abdel-Latif A, et al. Contemporary meta-analysis of extended direct-acting oral anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis to prevent venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2020;133:1074-1081.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.037

2. Spyropoulos AC, Hussein M, Lin J, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism occurrence in medical patients among the insured population. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:951-957. doi: 10.1160/TH09-02-0073

3. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl):e195S-226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296

4. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3198-3225. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

5. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(suppl):I-4-I-8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

6. Rivaroxaban . GoodRx. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.goodrx.com/rivaroxaban

1. Bhalla V, Lamping OF, Abdel-Latif A, et al. Contemporary meta-analysis of extended direct-acting oral anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis to prevent venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2020;133:1074-1081.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.037

2. Spyropoulos AC, Hussein M, Lin J, et al. Rates of venous thromboembolism occurrence in medical patients among the insured population. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:951-957. doi: 10.1160/TH09-02-0073

3. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl):e195S-226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296

4. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3198-3225. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

5. White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(suppl):I-4-I-8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66

6. Rivaroxaban . GoodRx. Accessed August 10, 2021. www.goodrx.com/rivaroxaban

PRACTICE CHANGER

Treat seriously ill patients with a

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials1

Bhalla V, Lamping OF, Abdel-Latif A, et al. Contemporary meta-analysis of extended direct-acting oral anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis to prevent venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2020;133:1074-1081.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.01.037

Validated scoring system identifies low-risk syncope patients

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 30-year-old woman presented to the ED after she “passed out” while standing at a concert. She lost consciousness for 10 seconds. After she revived, her friends drove her to the ED. She is healthy, with no chronic medical conditions, no medication use, and no drug or alcohol use. Should she be admitted to the hospital for observation?

Syncope, a transient loss of consciousness followed by spontaneous complete recovery, accounts for 1% of ED visits.2 Approximately 10% of patients presenting to the ED will have a serious underlying condition identified and among 3% to 5% of these patients with syncope, the serious condition will be identified only after they leave the ED.1 Most patients have a benign course, but more than half of all patients presenting to the ED with syncope will be hospitalized, costing $2.4 billion annually.2

Because of the high hospitalization rate of patients with syncope, a practical and accurate tool to risk-stratify patients is vital. Other tools, such as the San Francisco Syncope Rule, Short-Term Prognosis of Syncope, and Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department, lack validation or are excessively complex, with extensive lab work or testing.3

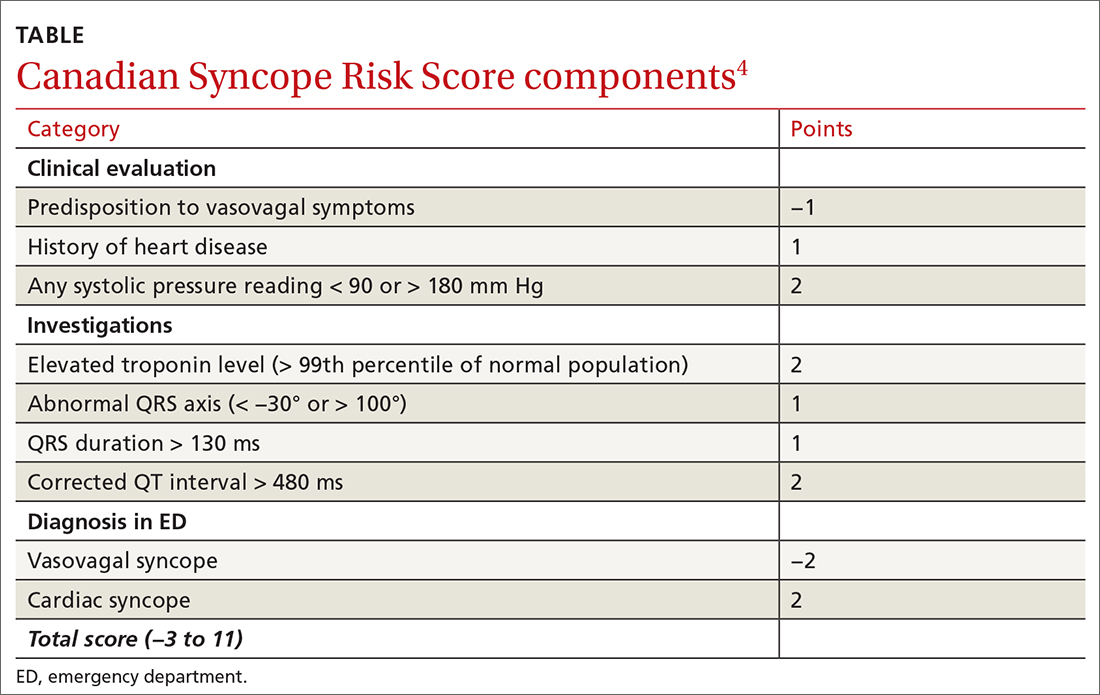

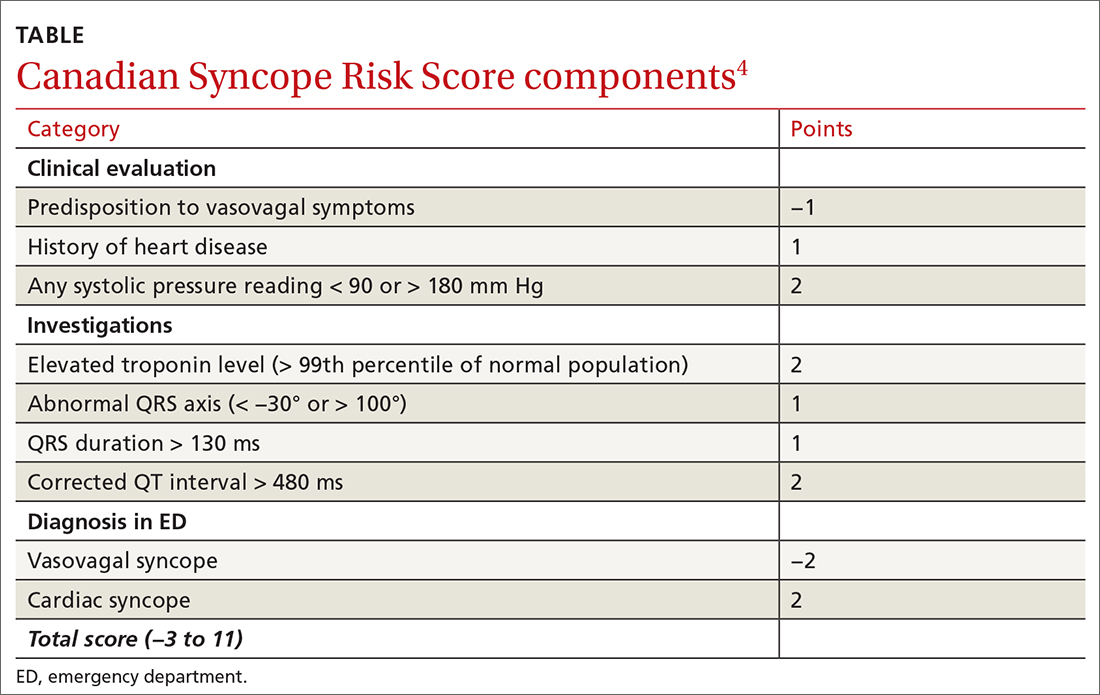

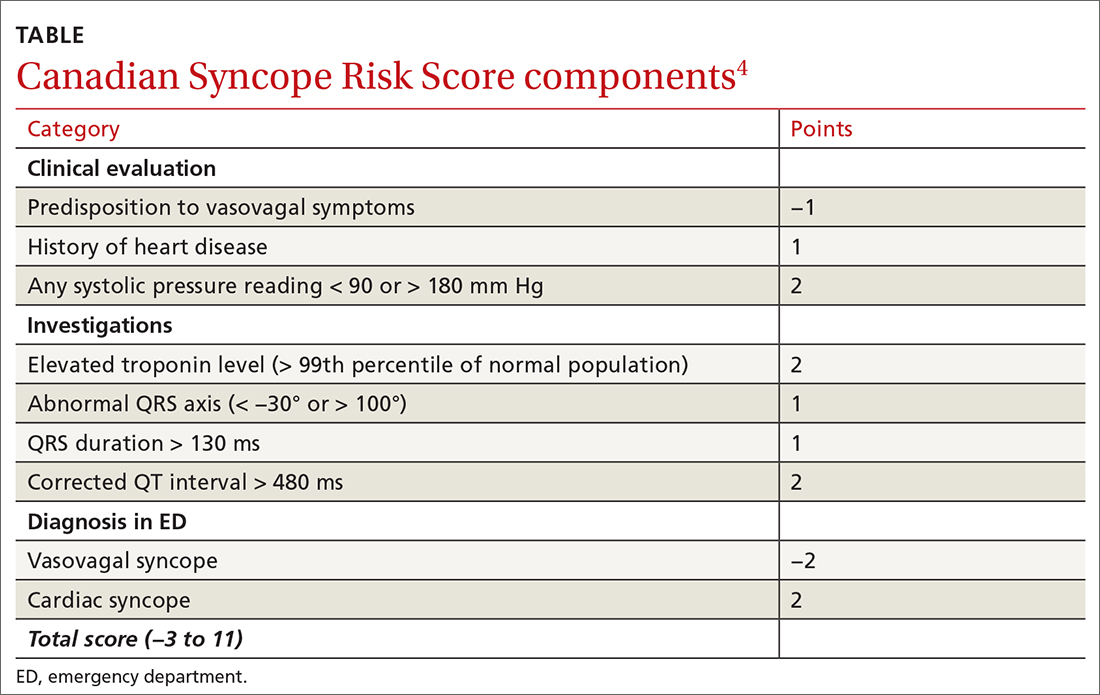

The CSRS was previously derived from a large, multisite consecutive cohort, and was internally validated and reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis guideline statement.4 Patients are assigned points based on clinical findings, test results, and the diagnosis given in the ED (TABLE4). The scoring system is used to stratify patients as very low (−3, −2), low (−1, 0), medium (1, 2, 3), high (4, 5), or very high (≥6) risk.4

STUDY SUMMARY

Less than 1% of very low– and low-risk patients had serious 30-day outcomes

This multisite Canadian prospective validation cohort study enrolled patients age ≥ 16 years who presented to the ED within 24 hours of syncope. Both discharged and hospitalized patients were included.1

Patients were excluded if they had loss of consciousness for > 5 minutes, mental status changes at presentation, history of current or previous seizure, or head trauma

ED physicians confirmed patient eligibility, obtained verbal consent, and completed the data collection form. In addition, research assistants sought to identify eligible patients who were not previously enrolled by reviewing all ED visits during the study period.

Continue to: To examine 30-day outcomes...

To examine 30-day outcomes, researchers reviewed all available patient medical record

A total of 4131 patients made up the validation cohort. A serious condition was identified during the initial ED visit in 160 patients (3.9%), who were excluded from the study, and 152 patients (3.7%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 3819 patients included in the final analysis, troponin was not measured in 1566 patients (41%), and an electrocardiogram was not obtained in 114 patients (3%). A serious outcome within 30 days was experienced by 139 patients (3.6%; 95% CI, 3.1%-4.3%). There was good correlation to the model-predicted serious outcome probability of 3.2% (95% CI, 2.7%-3.8%).1

Three of 1631 (0.2%) patients classified as very low risk and 9 of 1254 (0.7%) low-risk patients experienced a serious outcome, and no patients died. In the group classified as medium risk, 55 of 687 (8%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there was 1 death. In the high-risk group, 32 of 167 (19.2%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there were 5 deaths. In the group classified as very high risk, 40 of 78 (51.3%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there were 7 deaths. The CSRS was able to identify very low– or low-risk patients (score of −1 or better) with a sensitivity of 97.8% (95% CI, 93.8%-99.6%) and a specificity of 44.3% (95% CI, 42.7%-45.9%).1

WHAT’S NEW

This scoring system offers a validated method to risk-stratify ED patients

Previous recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Associationsuggested determining disposition of ED patients by using clinical judgment based on a list of risk factors such as age, chronic conditions, and medications. However, there was no scoring system.3 This new scoring system allows physicians to send home very low– and low-risk patients with reassurance that the likelihood of a serious outcome is less than 1%. High-risk and very high–risk patients should be admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Most moderate-risk patients (8% risk of serious outcome but 0.1% risk of death) can also be discharged after providers have a risk/benefit discussion, including precautions for signs of arrhythmia or need for urgent return to the hospital.

CAVEATS

The study does not translate to all clinical settings

Because this study was done in EDs, the scoring system cannot necessarily be applied to urgent care or outpatient settings. However, 41% of the patients in the study did not have troponin testing performed. Therefore, physicians could consider using the scoring system in settings where this lab test is not immediately available.

Continue to: This scoring system was also only...

This scoring system was also only validated with adult patients presenting within 24 hours of their syncopal episode. It is unknown how it may predict the outcomes of patients who present > 24 hours after syncope.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Clinicians may not be awareof the CSRS scoring system

The main challenge to implementation is practitioner awareness of the CSRS scoring system and how to use it appropriately, as there are several different syncopal scoring systems that may already be in use. Additionally, depending on the electronic health record used, the CSRS scoring system may not be embedded. Using and documenting scores may also be a challenge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, et al. Multicenter emergency department validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:737-744. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0288

2. Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Gbedemah M, et al. National trends in resource utilization associated with ED visits for syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:998-1001. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.030

3. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:620-663. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.002

4. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Kwong K, Wells GA, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ. 2016;188:E289-E298. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151469

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 30-year-old woman presented to the ED after she “passed out” while standing at a concert. She lost consciousness for 10 seconds. After she revived, her friends drove her to the ED. She is healthy, with no chronic medical conditions, no medication use, and no drug or alcohol use. Should she be admitted to the hospital for observation?

Syncope, a transient loss of consciousness followed by spontaneous complete recovery, accounts for 1% of ED visits.2 Approximately 10% of patients presenting to the ED will have a serious underlying condition identified and among 3% to 5% of these patients with syncope, the serious condition will be identified only after they leave the ED.1 Most patients have a benign course, but more than half of all patients presenting to the ED with syncope will be hospitalized, costing $2.4 billion annually.2

Because of the high hospitalization rate of patients with syncope, a practical and accurate tool to risk-stratify patients is vital. Other tools, such as the San Francisco Syncope Rule, Short-Term Prognosis of Syncope, and Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department, lack validation or are excessively complex, with extensive lab work or testing.3

The CSRS was previously derived from a large, multisite consecutive cohort, and was internally validated and reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis guideline statement.4 Patients are assigned points based on clinical findings, test results, and the diagnosis given in the ED (TABLE4). The scoring system is used to stratify patients as very low (−3, −2), low (−1, 0), medium (1, 2, 3), high (4, 5), or very high (≥6) risk.4

STUDY SUMMARY

Less than 1% of very low– and low-risk patients had serious 30-day outcomes

This multisite Canadian prospective validation cohort study enrolled patients age ≥ 16 years who presented to the ED within 24 hours of syncope. Both discharged and hospitalized patients were included.1

Patients were excluded if they had loss of consciousness for > 5 minutes, mental status changes at presentation, history of current or previous seizure, or head trauma

ED physicians confirmed patient eligibility, obtained verbal consent, and completed the data collection form. In addition, research assistants sought to identify eligible patients who were not previously enrolled by reviewing all ED visits during the study period.

Continue to: To examine 30-day outcomes...

To examine 30-day outcomes, researchers reviewed all available patient medical record

A total of 4131 patients made up the validation cohort. A serious condition was identified during the initial ED visit in 160 patients (3.9%), who were excluded from the study, and 152 patients (3.7%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 3819 patients included in the final analysis, troponin was not measured in 1566 patients (41%), and an electrocardiogram was not obtained in 114 patients (3%). A serious outcome within 30 days was experienced by 139 patients (3.6%; 95% CI, 3.1%-4.3%). There was good correlation to the model-predicted serious outcome probability of 3.2% (95% CI, 2.7%-3.8%).1

Three of 1631 (0.2%) patients classified as very low risk and 9 of 1254 (0.7%) low-risk patients experienced a serious outcome, and no patients died. In the group classified as medium risk, 55 of 687 (8%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there was 1 death. In the high-risk group, 32 of 167 (19.2%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there were 5 deaths. In the group classified as very high risk, 40 of 78 (51.3%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there were 7 deaths. The CSRS was able to identify very low– or low-risk patients (score of −1 or better) with a sensitivity of 97.8% (95% CI, 93.8%-99.6%) and a specificity of 44.3% (95% CI, 42.7%-45.9%).1

WHAT’S NEW

This scoring system offers a validated method to risk-stratify ED patients

Previous recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Associationsuggested determining disposition of ED patients by using clinical judgment based on a list of risk factors such as age, chronic conditions, and medications. However, there was no scoring system.3 This new scoring system allows physicians to send home very low– and low-risk patients with reassurance that the likelihood of a serious outcome is less than 1%. High-risk and very high–risk patients should be admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Most moderate-risk patients (8% risk of serious outcome but 0.1% risk of death) can also be discharged after providers have a risk/benefit discussion, including precautions for signs of arrhythmia or need for urgent return to the hospital.

CAVEATS

The study does not translate to all clinical settings

Because this study was done in EDs, the scoring system cannot necessarily be applied to urgent care or outpatient settings. However, 41% of the patients in the study did not have troponin testing performed. Therefore, physicians could consider using the scoring system in settings where this lab test is not immediately available.

Continue to: This scoring system was also only...

This scoring system was also only validated with adult patients presenting within 24 hours of their syncopal episode. It is unknown how it may predict the outcomes of patients who present > 24 hours after syncope.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Clinicians may not be awareof the CSRS scoring system

The main challenge to implementation is practitioner awareness of the CSRS scoring system and how to use it appropriately, as there are several different syncopal scoring systems that may already be in use. Additionally, depending on the electronic health record used, the CSRS scoring system may not be embedded. Using and documenting scores may also be a challenge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 30-year-old woman presented to the ED after she “passed out” while standing at a concert. She lost consciousness for 10 seconds. After she revived, her friends drove her to the ED. She is healthy, with no chronic medical conditions, no medication use, and no drug or alcohol use. Should she be admitted to the hospital for observation?

Syncope, a transient loss of consciousness followed by spontaneous complete recovery, accounts for 1% of ED visits.2 Approximately 10% of patients presenting to the ED will have a serious underlying condition identified and among 3% to 5% of these patients with syncope, the serious condition will be identified only after they leave the ED.1 Most patients have a benign course, but more than half of all patients presenting to the ED with syncope will be hospitalized, costing $2.4 billion annually.2

Because of the high hospitalization rate of patients with syncope, a practical and accurate tool to risk-stratify patients is vital. Other tools, such as the San Francisco Syncope Rule, Short-Term Prognosis of Syncope, and Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department, lack validation or are excessively complex, with extensive lab work or testing.3

The CSRS was previously derived from a large, multisite consecutive cohort, and was internally validated and reported according to the Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis guideline statement.4 Patients are assigned points based on clinical findings, test results, and the diagnosis given in the ED (TABLE4). The scoring system is used to stratify patients as very low (−3, −2), low (−1, 0), medium (1, 2, 3), high (4, 5), or very high (≥6) risk.4

STUDY SUMMARY

Less than 1% of very low– and low-risk patients had serious 30-day outcomes

This multisite Canadian prospective validation cohort study enrolled patients age ≥ 16 years who presented to the ED within 24 hours of syncope. Both discharged and hospitalized patients were included.1

Patients were excluded if they had loss of consciousness for > 5 minutes, mental status changes at presentation, history of current or previous seizure, or head trauma

ED physicians confirmed patient eligibility, obtained verbal consent, and completed the data collection form. In addition, research assistants sought to identify eligible patients who were not previously enrolled by reviewing all ED visits during the study period.

Continue to: To examine 30-day outcomes...

To examine 30-day outcomes, researchers reviewed all available patient medical record

A total of 4131 patients made up the validation cohort. A serious condition was identified during the initial ED visit in 160 patients (3.9%), who were excluded from the study, and 152 patients (3.7%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 3819 patients included in the final analysis, troponin was not measured in 1566 patients (41%), and an electrocardiogram was not obtained in 114 patients (3%). A serious outcome within 30 days was experienced by 139 patients (3.6%; 95% CI, 3.1%-4.3%). There was good correlation to the model-predicted serious outcome probability of 3.2% (95% CI, 2.7%-3.8%).1

Three of 1631 (0.2%) patients classified as very low risk and 9 of 1254 (0.7%) low-risk patients experienced a serious outcome, and no patients died. In the group classified as medium risk, 55 of 687 (8%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there was 1 death. In the high-risk group, 32 of 167 (19.2%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there were 5 deaths. In the group classified as very high risk, 40 of 78 (51.3%) patients experienced a serious outcome, and there were 7 deaths. The CSRS was able to identify very low– or low-risk patients (score of −1 or better) with a sensitivity of 97.8% (95% CI, 93.8%-99.6%) and a specificity of 44.3% (95% CI, 42.7%-45.9%).1

WHAT’S NEW

This scoring system offers a validated method to risk-stratify ED patients

Previous recommendations from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Associationsuggested determining disposition of ED patients by using clinical judgment based on a list of risk factors such as age, chronic conditions, and medications. However, there was no scoring system.3 This new scoring system allows physicians to send home very low– and low-risk patients with reassurance that the likelihood of a serious outcome is less than 1%. High-risk and very high–risk patients should be admitted to the hospital for further evaluation. Most moderate-risk patients (8% risk of serious outcome but 0.1% risk of death) can also be discharged after providers have a risk/benefit discussion, including precautions for signs of arrhythmia or need for urgent return to the hospital.

CAVEATS

The study does not translate to all clinical settings

Because this study was done in EDs, the scoring system cannot necessarily be applied to urgent care or outpatient settings. However, 41% of the patients in the study did not have troponin testing performed. Therefore, physicians could consider using the scoring system in settings where this lab test is not immediately available.

Continue to: This scoring system was also only...

This scoring system was also only validated with adult patients presenting within 24 hours of their syncopal episode. It is unknown how it may predict the outcomes of patients who present > 24 hours after syncope.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Clinicians may not be awareof the CSRS scoring system

The main challenge to implementation is practitioner awareness of the CSRS scoring system and how to use it appropriately, as there are several different syncopal scoring systems that may already be in use. Additionally, depending on the electronic health record used, the CSRS scoring system may not be embedded. Using and documenting scores may also be a challenge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, et al. Multicenter emergency department validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:737-744. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0288

2. Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Gbedemah M, et al. National trends in resource utilization associated with ED visits for syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:998-1001. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.030

3. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:620-663. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.002

4. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Kwong K, Wells GA, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ. 2016;188:E289-E298. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151469

1. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, et al. Multicenter emergency department validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:737-744. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0288

2. Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Gbedemah M, et al. National trends in resource utilization associated with ED visits for syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:998-1001. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.04.030

3. Shen WK, Sheldon RS, Benditt DG, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the evaluation and management of patients with syncope: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:620-663. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.002

4. Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Kwong K, Wells GA, et al. Development of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score to predict serious adverse events after emergency department assessment of syncope. CMAJ. 2016;188:E289-E298. doi:10.1503/cmaj.151469

PRACTICE CHANGER

Physicians should use the Canadian Syncope Risk Score (CSRS) to identify and send home very low– and low-risk patients from the emergency department (ED) after a syncopal episode.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Validated clinical decision rule based on a prospective cohort study1

Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Sivilotti MLA, Le Sage N, et al. Multicenter emergency department validation of the Canadian Syncope Risk Score. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:737-744. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0288