User login

Hidden Basal Cell Carcinoma in the Intergluteal Crease

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

Cutaneous Manifestations of COVID-19

The pathogenesis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is not yet completely understood. Thus far, it is known to affect multiple organ systems, including gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular, with typical clinical symptoms of COVID-19 including fever, cough, myalgia, headache, anosmia, and diarrhea.1 This multiorgan attack may be secondary to an exaggerated inflammatory reaction with vasculopathy and possibly a hypercoagulable state. Skin manifestations also are prevalent in COVID-19, and they often result in polymorphous presentations.2 This article aims to summarize cutaneous clinical signs of COVID-19 so that dermatologists can promptly identify and manage COVID-19 and prevent its spread.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted on June 30, 2020. The literature included observational studies, case reports, and literature reviews from January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020. Search terms included COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, and coronavirus used in combination with cutaneous, skin, and dermatology. All of the resulting articles were then reviewed for relevance to the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. Only confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection were included in this review; suspected unconfirmed cases were excluded. Further exclusion criteria included articles that discussed dermatology in the time of COVID-19 that did not explicitly address its cutaneous manifestations. The remaining literature was evaluated to provide dermatologists and patients with a concise resource for the cutaneous signs and symptoms of COVID-19. Data extracted from the literature included geographic region, number of patients with skin findings, status of COVID-19 infection and timeline, and cutaneous signs. If a cutaneous sign was not given a clear diagnosis in the literature, the senior authors (A.L. and J.J.) assigned it to its most similar classification to aid in ease of understanding and clarity for the readers.

Results

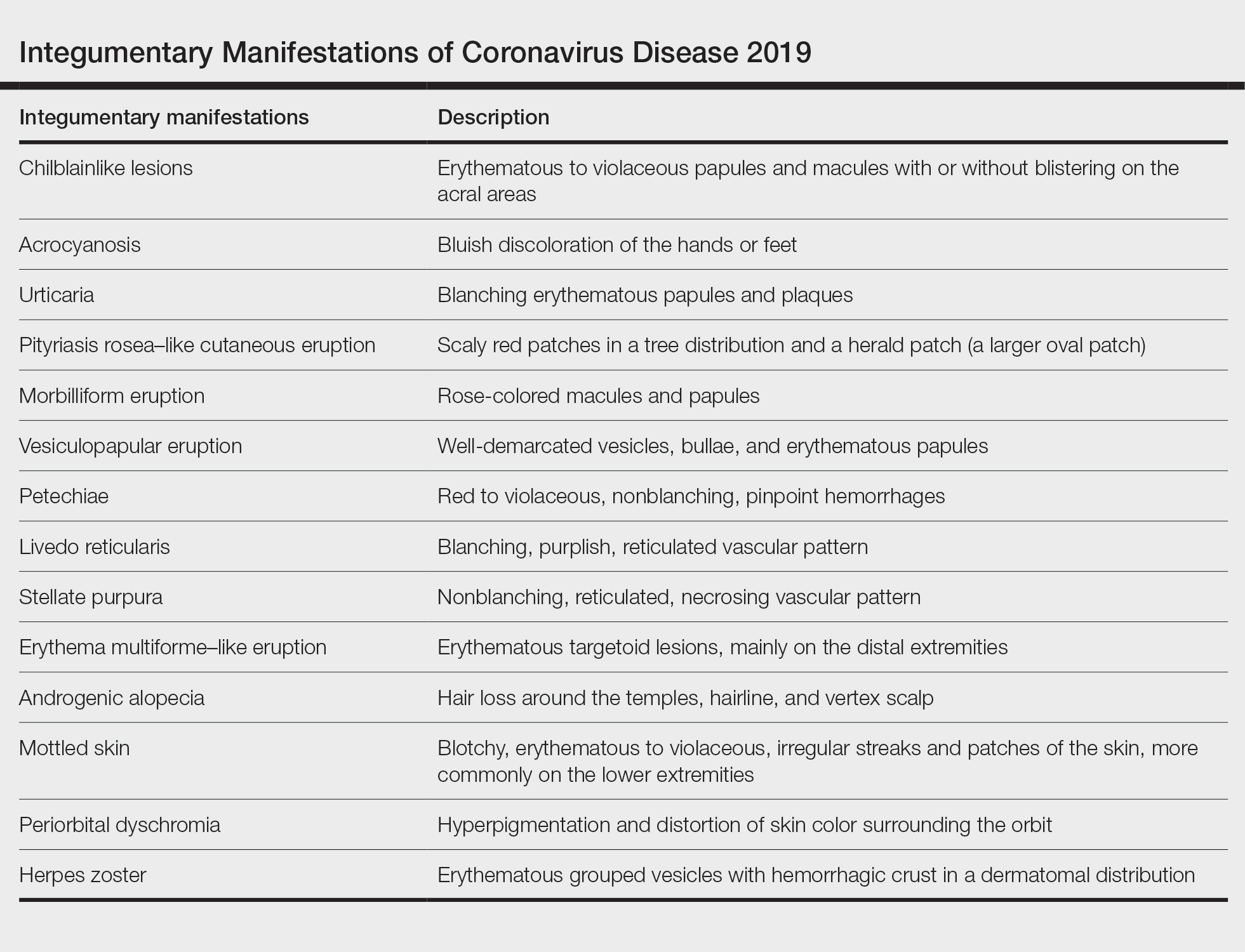

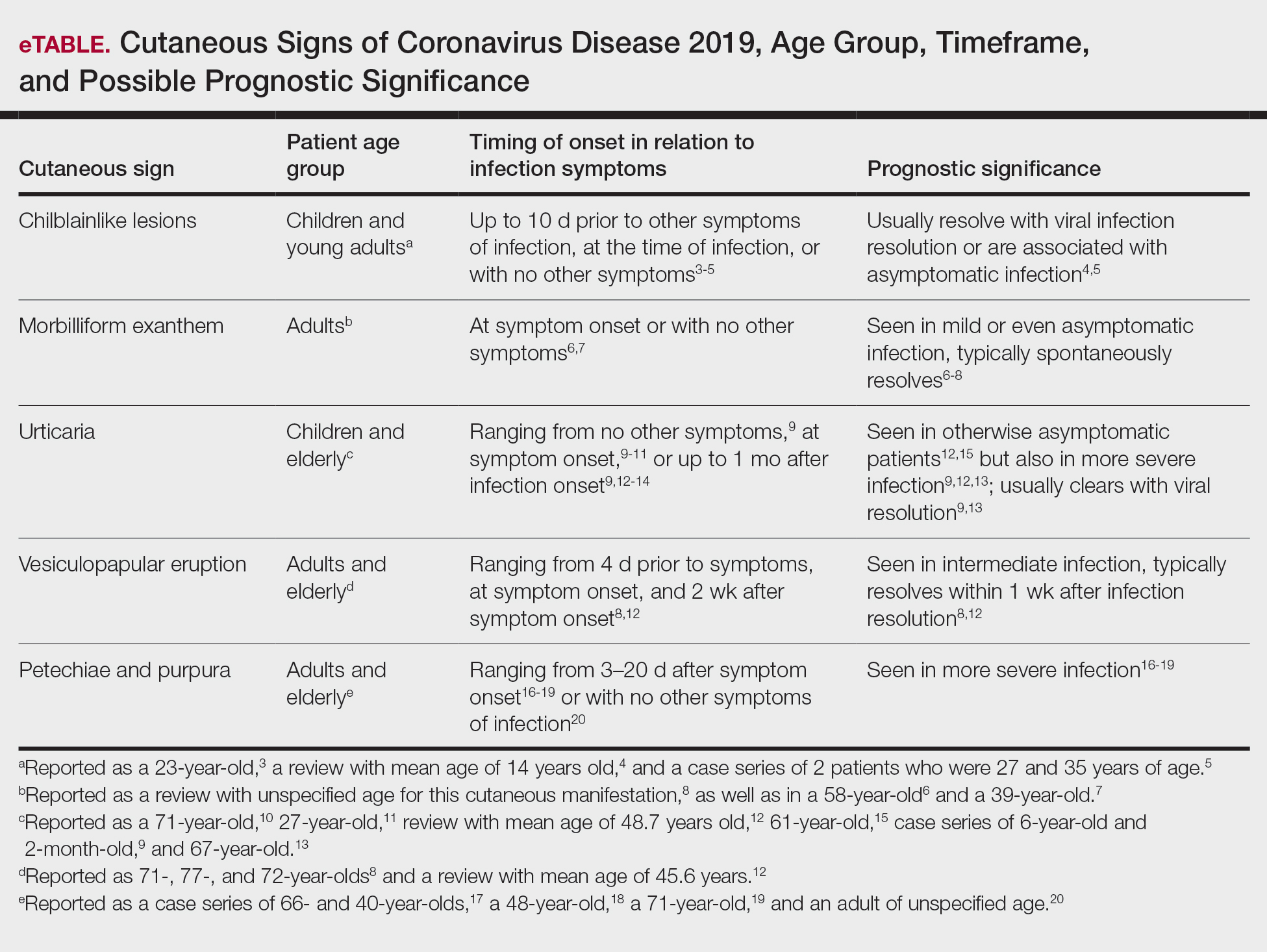

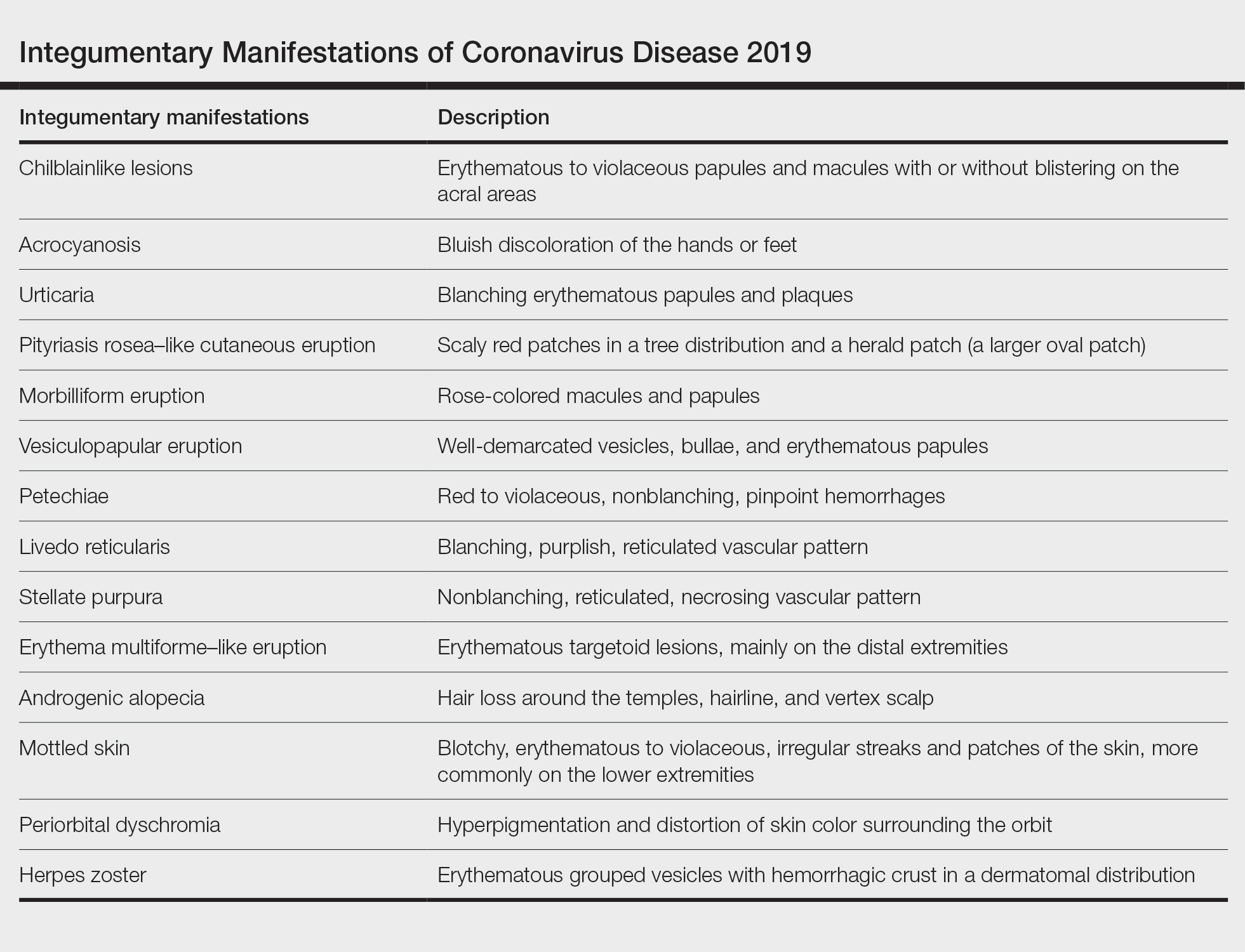

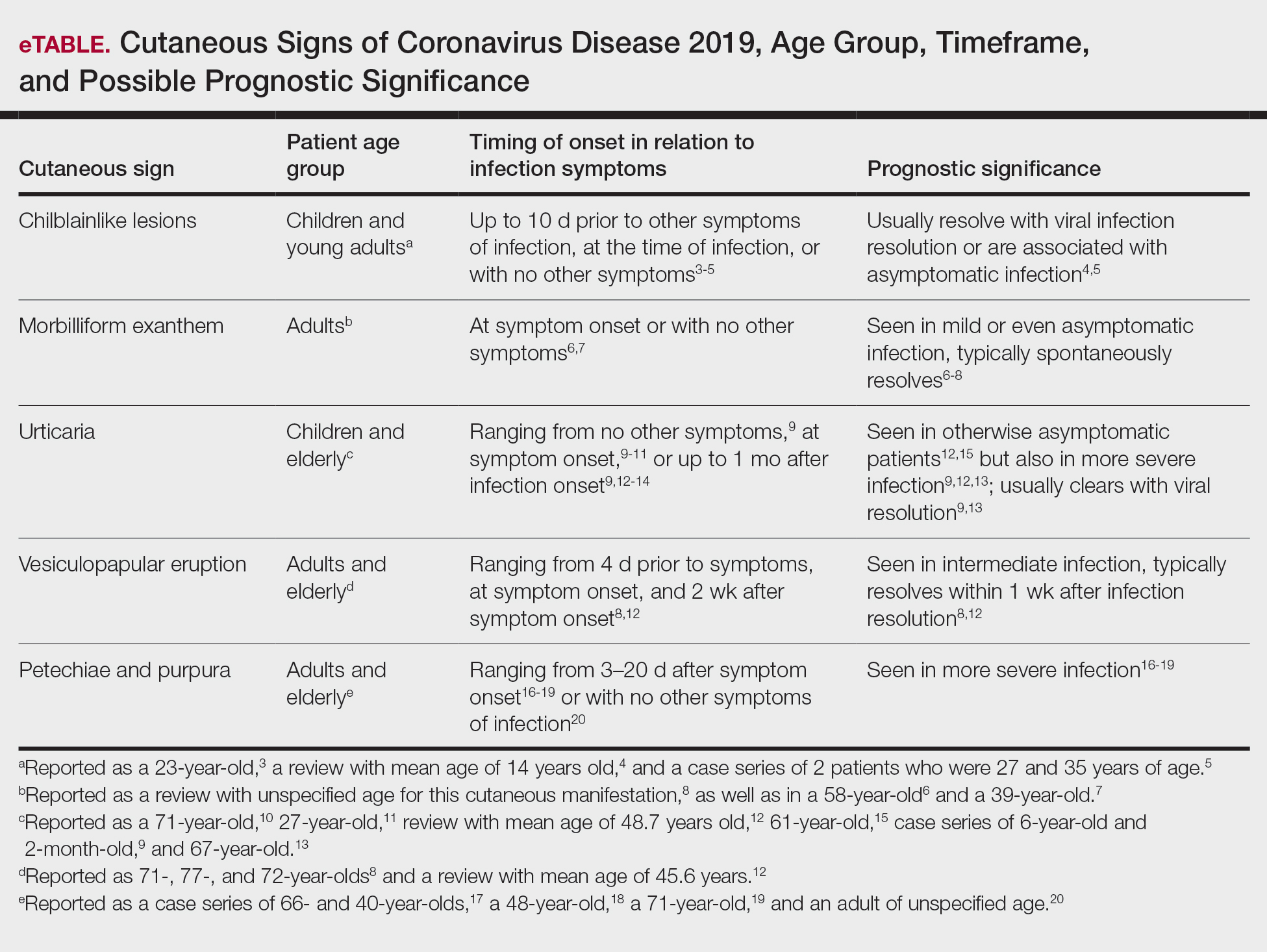

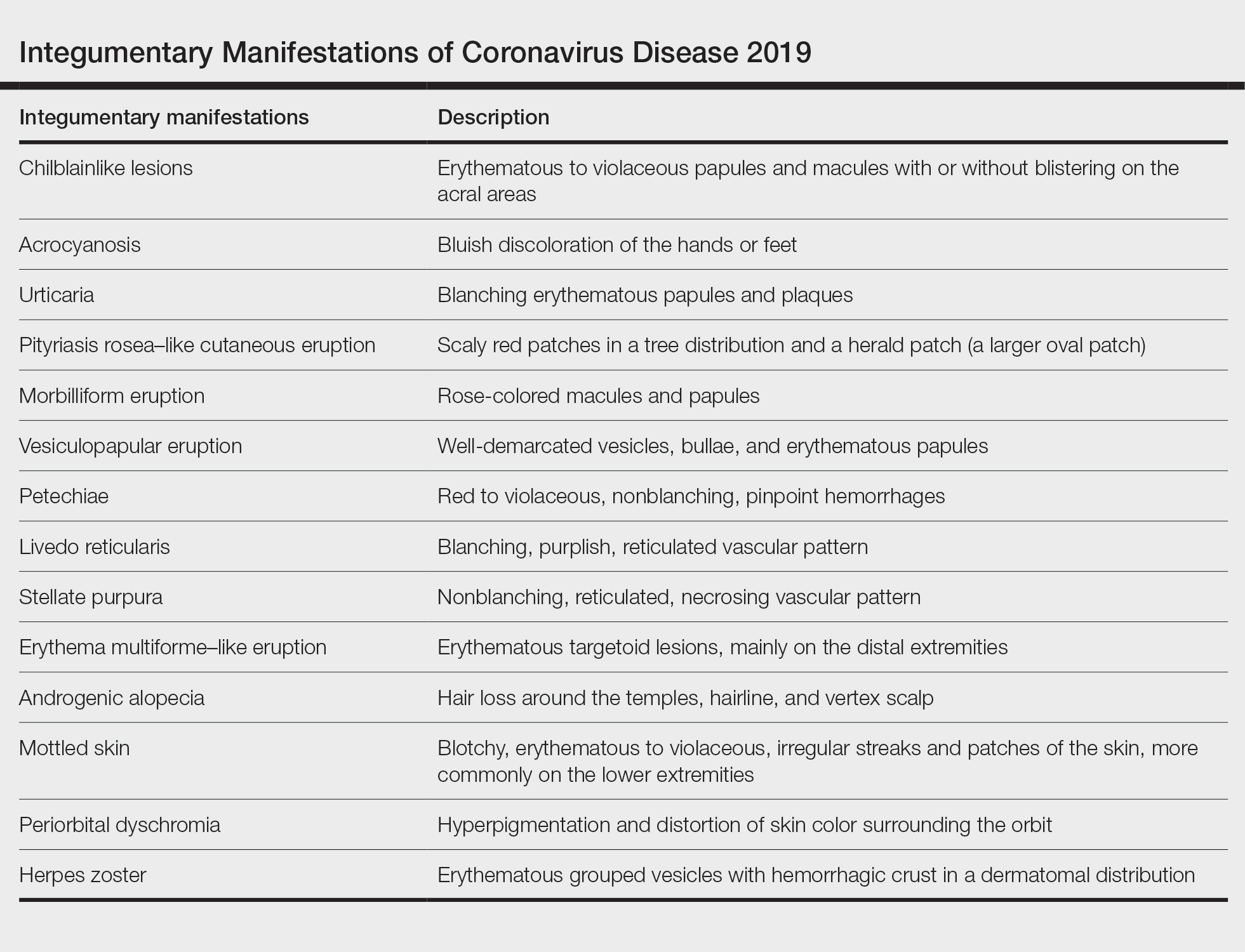

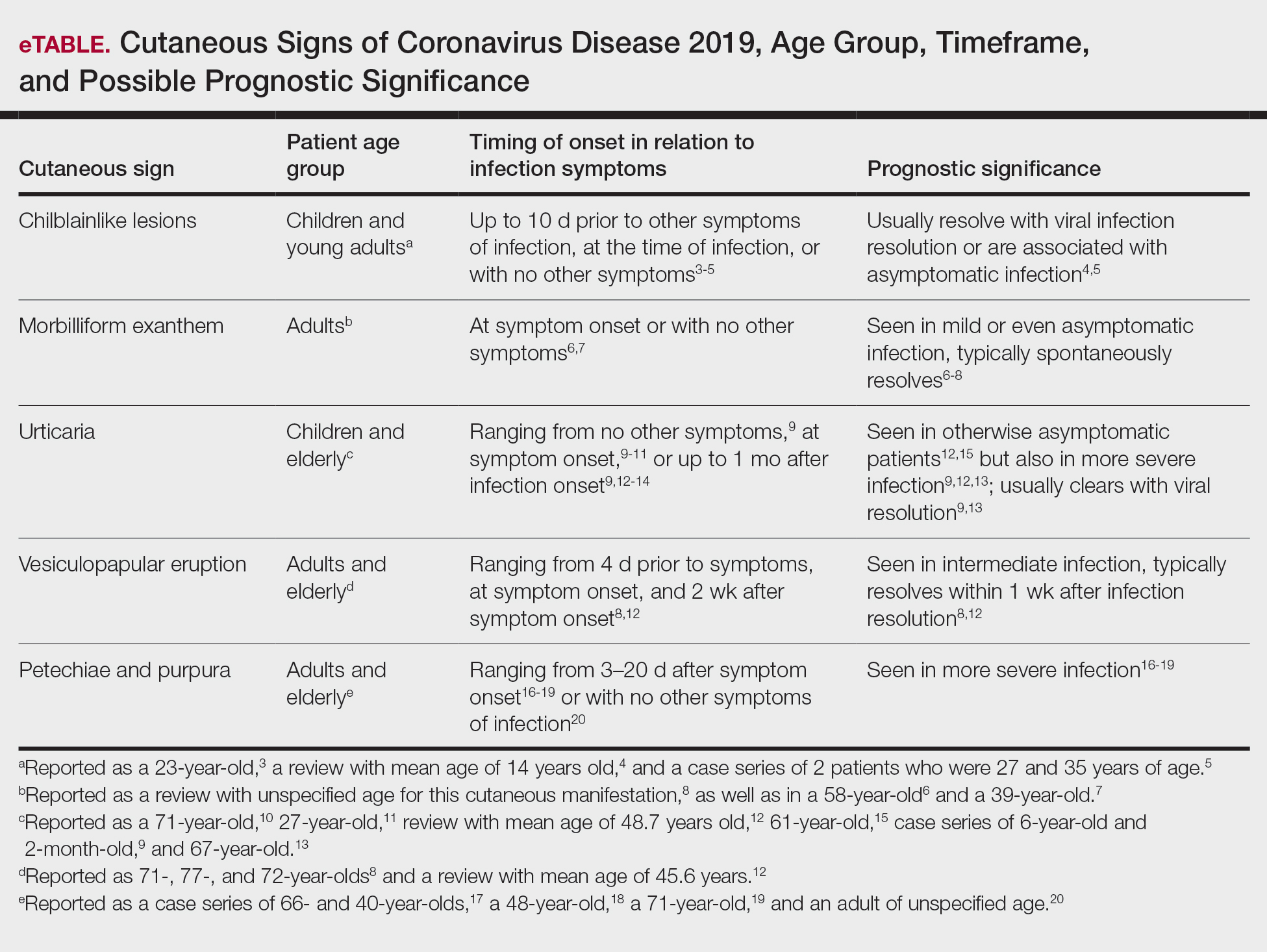

A search of the key terms resulted in 75 articles published in the specified date range. After excluding overtly irrelevant articles and dermatologic conditions in the time of COVID-19 without confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, 25 articles ultimately met inclusion criteria. Relevant references from the articles also were explored for cutaneous dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19. Cutaneous manifestations that were repeatedly reported included chilblainlike lesions; acrocyanosis; urticaria; pityriasis rosea–like cutaneous eruption; erythema multiforme–like, vesiculopapular, and morbilliform eruptions; petechiae; livedo reticularis; and purpuric livedo reticularis (dermatologists may label this stellate purpura). Fewer but nonetheless notable cases of androgenic alopecia, periorbital dyschromia, and herpes zoster exacerbations also were documented. The Table summarizes the reported integumentary findings. The eTable groups the common findings and describes patient age, time to onset of cutaneous sign, and any prognostic significance as seen in the literature.

Chilblainlike Lesions and Acrocyanosis

Chilblainlike lesions are edematous eruptions of the fingers and toes. They usually do not scar and are described as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules with possible bullae on the digits. Skin biopsies demonstrate a histopathologic pattern of vacuolar interface dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes and a thickened basement membrane. Lymphocytic infiltrate presents in a perieccrine distribution, occasionally with plasma cells. The dermatopathologic findings mimic those of chilblain lupus but lack dermal edema.3

These eruptions have been reported in cases of COVID-19 that more frequently affect children and young adults. They usually resolve over the course of viral infection, averaging within 14 days. Chilblainlike eruptions often are associated with pruritus or pain. They commonly are asymmetrical and appear more often on the toes than the fingers.4 In cases of COVID-19 that lack systemic symptoms, chilblainlike lesions have been seen on the dorsal fingers as the first presenting sign of infection.5

Acral erythema and chilblainlike lesions frequently have been associated with milder infection. Another positive prognostic indicator is the manifestation of these signs in younger individuals.3

Morbilliform Exanthem

The morbilliform exanthem associated with COVID-19 also typically presents in patients with milder disease. It often affects the buttocks, lower abdomen, and thighs, but spares the palms, soles, and mucosae.4 This skin sign, which may start out as a generalized morbilliform exanthem, has been seen to morph into macular hemorrhagic purpura on the legs. These cutaneous lesions typically spontaneously resolve.8

In a case report by Najarian,6 a morbilliform exanthem was seen on the legs, arms, and trunk of a patient who was otherwise asymptomatic but tested positive for COVID-19. The morbilliform exanthem then became confluent on the trunk. Notably, the patient reported pain of the hands and feet.6

Another case report described a patient with edematous annular plaques on the palms, neck, and upper extremities who presented solely with fever.7 The biopsy specimen was nonspecific but indicated a viral exanthem. Histopathology showed perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, dermal edema and vacuoles, spongiosis, dyskeratotic basilar keratinocytes, and few neutrophils without eosinophils.7

Eczematous Eruption

A confluent eczematous eruption in the flexural areas, the antecubital fossae, and axillary folds has been found in COVID-19 patients.21,22 An elderly patient with severe COVID-19 developed a squamous erythematous periumbilical patch 1 day after hospital admission. The cutaneous eruption rapidly progressed to digitate scaly plaques on the trunk, thighs, and flank. A biopsy specimen showed epidermal spongiosis, vesicles containing lymphocytes, and Langerhans cells. The upper dermis demonstrated a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.23

Pityriasis Rosea–Like Eruption

In Iran, a COVID-19–infected patient developed an erythematous papulosquamous eruption with a herald patch and trailing scales 3 days after viral symptoms, resembling that of pityriasis rosea.24 Nests of Langerhans cells within the epidermis are seen in many viral exanthems, including cases of COVID-19 and pityriasis rosea.25

Urticaria

According to a number of case reports, urticarial lesions have been the first presenting sign of COVID-19 infection, most resolving with antihistamines.10,11 Some patients with more severe symptoms have had widespread urticaria. An urticarial exanthem appearing on the bilateral thighs and buttocks may be the initial sign of infection.12,15 Pruritic erythematous plaques over the face and acral areas is another initial sign. Interestingly, pediatric patients have reported nonpruritic urticaria.9

Urticaria also has been seen as a late dermatologic sign of viral infection. After battling relentless viral infection for 1 month, a pruritic, confluent, ill-defined eruption appeared along a patient’s trunk, back, and proximal extremities. Histopathologic examination concluded a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dilated vessels in the dermis. The urticaria resolved a week later, and the patient’s nasopharyngeal swab finally came back negative.13

Vesiculopapular Eruption

Vesicles mimicking those of chickenpox have been reported. A study of 375 confirmed cases of COVID-19 by Galván Casas et al12 showed a 9% incidence of this vesicular eruption. A study by Sachdeva et al8 revealed vesicular eruptions in 25 of 72 patients. Pruritic papules and vesicles may resemble Grover disease. This cutaneous sign may be seen in the submammary folds, on the hips, or diffusely over the body.

Erythema Multiforme–Like Eruption

Targetoid lesions similar to those of erythema multiforme erupted in 2 of 27 patients with mild COVID-19 infection in a review by Wollina et al.4 In a study of 4 patients with erythema multiforme–like eruptions after COVID-19 symptoms resolved, 3 had palatal petechiae. Two of 4 patients had pseudovesicles in the center of the erythematous targetoid patches.26 Targetoid lesions on the extremities have been reported in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infections. These patients often present without any typical viral symptoms but rather just a febrile exanthem or exanthem alone. Thus, to minimize spread of the virus, it is vital to recognize COVID-19 infection early in patients with a viral exanthem during the time of high COVID-19 incidence.4

Livedo Reticularis

In the United States, a case series reported 2 patients with transient livedo reticularis throughout the course of COVID-19 infection. The cutaneous eruption resembled erythema ab igne, but there was no history of exposure to heat.16

Stellate Purpura

In severe COVID-19 infection, a reticulated nonblanching purpura on the buttocks has been reported to demonstrate pauci-inflammatory vascular thrombosis, complement membrane attack complex deposition, and endothelial injury on dermatopathology. Stellate purpura on palmoplantar surfaces also has shown arterial thrombosis in the deep dermis due to complement deposition.17

Petechiae and Purpura

A morbilliform exanthem may develop into significant petechiae in the popliteal fossae, buttocks, and thighs. A punch biopsy specimen demonstrates a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with erythrocyte extravasation and papillary dermal edema with dyskeratotic cells.18 Purpura of the lower extremities may develop, with histopathology showing fibrinoid necrosis of small vessel walls, neutrophilic infiltrate with karyorrhexis, and granular complement deposition.19

In Thailand, a patient was misdiagnosed with dengue after presenting with petechiae and low platelet count.20 Further progression of the viral illness resulted in respiratory symptoms. Subsequently, the patient tested positive for COVID-19. This case demonstrates that cutaneous signs of many sorts may be the first presenting signs of COVID-19, even prior to febrile symptoms.20

Androgenic Alopecia

Studies have shown that androgens are related in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Coronavirus disease 2019 uses a cellular co-receptor, TMPRSS2, which is androgen regulated.27 In a study of 41 males with COVID-19, 29 had androgenic alopecia. However, this is only a correlation, and causation cannot be concluded here. It cannot be determined from this study whether androgenic alopecia is a risk factor, result of COVID-19, or confounder.28

Exaggerated Herpes Zoster

Shors29 reported a herpes zoster eruption in a patient who had symptoms of COVID-19 for 1 week. Further testing confirmed COVID-19 infection, and despite prompt treatment with valacyclovir, the eruption was slow to resolve. The patient then experienced severe postherpetic neuralgia for more than 4 weeks, even with treatment with gabapentin and lidocaine. It is hypothesized that because of the major inflammatory response caused by COVID-19, an exaggerated inflammation occurred in the dorsal root ganglion, resulting in relentless herpes zoster infection.29

Mottled Skin

Born at term, a 15-day-old neonate presented with sepsis and mottling of the skin. The patient did not have any typical COVID-19 symptoms, such as diarrhea or cough, but tested positive for COVID-19.30

Periorbital Dyschromia

Kalner and Vergilis31 reported 2 cases of periorbital dyschromia prior to any other COVID-19 infection symptoms. The discoloration improved with resolution of ensuing viral symptoms.31

Comment

Many dermatologic signs of COVID-19 have been identified. Their individual frequency and association with viral severity will become more apparent as more cases are reported. So far during this pandemic, common dermatologic manifestations have been polymorphic in clinical presentation.

Onset of Skin Manifestations

The timeline of skin signs and COVID-19 symptoms varies from the first reported sign to weeks after symptom resolution. In the Region of Murcia, Spain, Pérez-Suárez et al14 collected data on cutaneous signs of patients with COVID-19. Of the patients studied, 9 had tests confirming COVID-19 infection. Truncal urticaria, sacral ulcers, acrocyanosis, and erythema multiforme were all reported in patients more than 2 weeks after symptom onset. One case of tinea infection also was reported 4 days after fever and respiratory symptoms began.14

Presentation

Coronavirus disease 2019 has affected the skin of both the central thorax and peripheral locations. In a study of 72 patients with cutaneous signs of COVID-19 by Sachdeva et al,8 a truncal distribution was most common, but 14 patients reported acral site involvement. Sachdeva et al8 reported urticarial reactions in 7 of 72 patients with cutaneous signs. A painful acral cyanosis was seen in 11 of 72 patients. Livedo reticularis presented in 2 patients, and only 1 patient had petechiae. Cutaneous signs were the first indicators of viral infection in 9 of 72 patients; 52 patients presented with respiratory symptoms first. All of the reported cutaneous signs spontaneously resolved within 10 days.8

Recalcati32 reviewed 88 patients with COVID-19, and 18 had cutaneous signs at initial onset of viral infection or during hospitalization. The most common integumentary sign reported in this study was erythema, followed by diffuse urticaria, and then a vesicular eruption resembling varicella infection.32

Some less common phenomena have been identified in patients with COVID-19, including androgenic alopecia, exaggerated herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia, mottled skin, and periorbital dyschromia. Being aware of these complications may help in early treatment, diagnosis, and even prevention of viral spread.

Pathogenesis of Skin Manifestations

Few breakthroughs have been made in understanding the pathogenesis of skin manifestations of SARS-CoV-2. Acral ischemia may be a manifestation of COVID-19’s association with hypercoagulation. Increasing fibrinogen and prothrombin times lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation and microthrombi. These tiny blood clots then lodge in blood vessels and cause acral cyanosis and subsequent gangrene.2 The proposed mechanism behind this clinical manifestation in younger populations is the hypercoagulable state that COVID-19 creates. Conversely, acral erythema and chilblainlike lesions in older patients are thought to be from acral ischemia as a response to insufficient type 1 interferons. This pathophysiologic mechanism is indicative of a worse prognosis due to the large role that type 1 interferons play in antiviral responses. Coronavirus disease 2019 similarly triggers type 1 interferons; thus, their efficacy positively correlates with good disease prognosis.3

Similarly, the pathogenesis for livedo reticularis in patients with COVID-19 can only be hypothesized. Infected patients are in a hypercoagulable state, and in these cases, it was uncertain whether this was due to a disseminated intravascular coagulation, cold agglutinins, cryofibrinogens, or lupus anticoagulant.16

Nonetheless, it can be difficult to separate the primary event between vasculopathy or vasculitis in larger vessel pathology specimens. Some of the studies’ pathology reports discuss a granulocytic infiltrate and red blood cell extravasation, which represent small vessel vasculitis. However, the gangrene and necrosing livedo represent vasculopathy events. A final conclusion about the pathogenesis cannot be made without further clinical and histopathologic evaluation.

Histopathology

Biopsy specimens of reported morbilliform eruptions have demonstrated thrombosed vessels with evidence of necrosis and granulocytic infiltrate.25 Another biopsy specimen of a widespread erythematous exanthem demonstrated extravasated red blood cells and vessel wall damage similar to thrombophilic arteritis. Other reports of histopathology showed necrotic keratinocytes and lymphocytic satellitosis at the dermoepidermal junction, resembling Grover disease. These cases demonstrating necrosis suggest a strong cytokine reaction from the virus.25 A concern with these biopsy findings is that morbilliform eruptions generally show dilated vessels with lymphocytes, and these biopsy findings are consistent with a cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Additionally, histopathologic evaluation of purpuric eruptions has shown erythrocyte extravasation and granulocytic infiltrate indicative of a cutaneous small vessel vasculitis.

Although most reported cases of cutaneous signs of COVID-19 do not have histopathologic reports, Yao et al33 conducted a dermatopathologic study that investigated the tissue in deceased patients who had COVID-19. This pathology showed hyaline thrombi within the small vessels of the skin, likely leading to the painful acral ischemia. Similarly, Yao et al33 reported autopsies finding hyaline thrombi within the small vessels of the lungs. More research should be done to explore this pathogenesis as part of prognostic factors and virulence.

Conclusion

Cutaneous signs may be the first reported symptom of COVID-19 infection, and dermatologists should be prepared to identify them. This review may be used as a guide for physicians to quickly identify potential infection as well as further understand the pathogenesis related to COVID-19. Future research is necessary to determine the dermatologic pathogenesis, infectivity, and prevalence of cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. It also will be important to explore if vasculopathic lesions predict more severe multisystem disease.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506.

- Criado PR, Abdalla BMZ, de Assis IC, et al. Are the cutaneous manifestations during or due to SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 frequent or not? revision of possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:745-756.

- Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection–induced chilblains: a case report with histopathological findings. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:489-492.

- Wollina U, Karadag˘ AS, Rowland-Payne C, et al. Cutaneous signs in COVID-19 patients: a review [published online May 10, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13549.

- Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. Two cases of COVID-19 presenting with a clinical picture resembling chilblains: first report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:746-748.

- Najarian DJ. Morbilliform exanthem associated with COVID‐19. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:493-494.

- Amatore F, Macagno N, Mailhe M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection presenting as a febrile rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E304-E306.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81.

- Morey-Olivé M, Espiau M, Mercadal-Hally M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in the current pandemic of coronavirus infection disease (COVID 2019). An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2020;92:374-375.

- van Damme C, Berlingin E, Saussez S, et al. Acute urticaria with pyrexia as the first manifestations of a COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E300-E301.

- Henry D, Ackerman M, Sancelme E, et al. Urticarial eruption in COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E244-E245.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77.

- Zengarini C, Orioni G, Cascavilla A, et al. Histological pattern in Covid-19-induced viral rash [published online May 2, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16569.

- Pérez-Suárez B, Martínez-Menchón T, Cutillas-Marco E. Skin findings in the COVID-19 pandemic in the Region of Murcia [published online June 12, 2020]. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;155:41-42.

- Quintana-Castanedo L, Feito-Rodríguez M, Valero-López I, et al. Urticarial exanthem as early diagnostic clue for COVID-19 infection [published online April 29, 2020]. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:498-499.

- Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, et al. Reply to: “reply: a dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: transient livedo reticularis” [published online May 7, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E157.

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13.

- Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:820-822.

- Dominguez-Santas M, Diaz-Guimaraens B, Garcia Abellas P, et al. Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis associated with novel 2019 coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) [published online July 2, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E536-E537.

- Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID-19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue [published online March 22, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E177.

- Avellana Moreno R, Estella Villa LM, Avellana Moreno V, et al. Cutaneous manifestation of COVID‐19 in images: a case report [published online May 19, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E307-E309.

- Mahé A, Birckel E, Krieger S, et al. A distinctive skin rash associated with coronavirus disease 2019 [published online June 8, 2020]? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E246-E247.

- Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S, et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:819-820.

- Ehsani AH, Nasimi M, Bigdelo Z. Pityriasis rosea as a cutaneous manifestation of COVID‐19 infection [published online May 2, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16579.

- Gianotti R, Veraldi S, Recalcati S, et al. Cutaneous clinico-pathological findings in three COVID-19-positive patients observed in the metropolitan area of Milan, Italy. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00124.

- Jimenez-Cauhe J, Ortega-Quijano D, Carretero-Barrio I, et al. Erythema multiforme-like eruption in patients with COVID-19 infection: clinical and histological findings [published online May 9, 2020]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.14281

- Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor [published online March 5, 2020]. Cell. 2020;181:271‐280.e8.

- Goren A, Vaño‐Galván S, Wambier CG, et al. A preliminary observation: male pattern hair loss among hospitalized COVID‐19 patients in Spain—a potential clue to the role of androgens in COVID‐19 severity [published online April 23, 2020]. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:1545-1547.

- Shors AR. Herpes zoster and severe acute herpetic neuralgia as a complication of COVID-19 infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:656-657.

- Kamali Aghdam M, Jafari N, Eftekhari K. Novel coronavirus in a 15‐day‐old neonate with clinical signs of sepsis, a case report. Infect Dis (London). 2020;52:427‐429.

- Kalner S, Vergilis IJ. Periorbital erythema as a presenting sign of covid-19 [published online May 11, 2020]. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:996-998.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E212-E213.

- Yao XH, Li TY, He ZC, et al. A pathological report of three COVID‐19 cases by minimally invasive autopsies [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:411-417.

The pathogenesis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is not yet completely understood. Thus far, it is known to affect multiple organ systems, including gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular, with typical clinical symptoms of COVID-19 including fever, cough, myalgia, headache, anosmia, and diarrhea.1 This multiorgan attack may be secondary to an exaggerated inflammatory reaction with vasculopathy and possibly a hypercoagulable state. Skin manifestations also are prevalent in COVID-19, and they often result in polymorphous presentations.2 This article aims to summarize cutaneous clinical signs of COVID-19 so that dermatologists can promptly identify and manage COVID-19 and prevent its spread.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted on June 30, 2020. The literature included observational studies, case reports, and literature reviews from January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020. Search terms included COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, and coronavirus used in combination with cutaneous, skin, and dermatology. All of the resulting articles were then reviewed for relevance to the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. Only confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection were included in this review; suspected unconfirmed cases were excluded. Further exclusion criteria included articles that discussed dermatology in the time of COVID-19 that did not explicitly address its cutaneous manifestations. The remaining literature was evaluated to provide dermatologists and patients with a concise resource for the cutaneous signs and symptoms of COVID-19. Data extracted from the literature included geographic region, number of patients with skin findings, status of COVID-19 infection and timeline, and cutaneous signs. If a cutaneous sign was not given a clear diagnosis in the literature, the senior authors (A.L. and J.J.) assigned it to its most similar classification to aid in ease of understanding and clarity for the readers.

Results

A search of the key terms resulted in 75 articles published in the specified date range. After excluding overtly irrelevant articles and dermatologic conditions in the time of COVID-19 without confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, 25 articles ultimately met inclusion criteria. Relevant references from the articles also were explored for cutaneous dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19. Cutaneous manifestations that were repeatedly reported included chilblainlike lesions; acrocyanosis; urticaria; pityriasis rosea–like cutaneous eruption; erythema multiforme–like, vesiculopapular, and morbilliform eruptions; petechiae; livedo reticularis; and purpuric livedo reticularis (dermatologists may label this stellate purpura). Fewer but nonetheless notable cases of androgenic alopecia, periorbital dyschromia, and herpes zoster exacerbations also were documented. The Table summarizes the reported integumentary findings. The eTable groups the common findings and describes patient age, time to onset of cutaneous sign, and any prognostic significance as seen in the literature.

Chilblainlike Lesions and Acrocyanosis

Chilblainlike lesions are edematous eruptions of the fingers and toes. They usually do not scar and are described as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules with possible bullae on the digits. Skin biopsies demonstrate a histopathologic pattern of vacuolar interface dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes and a thickened basement membrane. Lymphocytic infiltrate presents in a perieccrine distribution, occasionally with plasma cells. The dermatopathologic findings mimic those of chilblain lupus but lack dermal edema.3

These eruptions have been reported in cases of COVID-19 that more frequently affect children and young adults. They usually resolve over the course of viral infection, averaging within 14 days. Chilblainlike eruptions often are associated with pruritus or pain. They commonly are asymmetrical and appear more often on the toes than the fingers.4 In cases of COVID-19 that lack systemic symptoms, chilblainlike lesions have been seen on the dorsal fingers as the first presenting sign of infection.5

Acral erythema and chilblainlike lesions frequently have been associated with milder infection. Another positive prognostic indicator is the manifestation of these signs in younger individuals.3

Morbilliform Exanthem

The morbilliform exanthem associated with COVID-19 also typically presents in patients with milder disease. It often affects the buttocks, lower abdomen, and thighs, but spares the palms, soles, and mucosae.4 This skin sign, which may start out as a generalized morbilliform exanthem, has been seen to morph into macular hemorrhagic purpura on the legs. These cutaneous lesions typically spontaneously resolve.8

In a case report by Najarian,6 a morbilliform exanthem was seen on the legs, arms, and trunk of a patient who was otherwise asymptomatic but tested positive for COVID-19. The morbilliform exanthem then became confluent on the trunk. Notably, the patient reported pain of the hands and feet.6

Another case report described a patient with edematous annular plaques on the palms, neck, and upper extremities who presented solely with fever.7 The biopsy specimen was nonspecific but indicated a viral exanthem. Histopathology showed perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, dermal edema and vacuoles, spongiosis, dyskeratotic basilar keratinocytes, and few neutrophils without eosinophils.7

Eczematous Eruption

A confluent eczematous eruption in the flexural areas, the antecubital fossae, and axillary folds has been found in COVID-19 patients.21,22 An elderly patient with severe COVID-19 developed a squamous erythematous periumbilical patch 1 day after hospital admission. The cutaneous eruption rapidly progressed to digitate scaly plaques on the trunk, thighs, and flank. A biopsy specimen showed epidermal spongiosis, vesicles containing lymphocytes, and Langerhans cells. The upper dermis demonstrated a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.23

Pityriasis Rosea–Like Eruption

In Iran, a COVID-19–infected patient developed an erythematous papulosquamous eruption with a herald patch and trailing scales 3 days after viral symptoms, resembling that of pityriasis rosea.24 Nests of Langerhans cells within the epidermis are seen in many viral exanthems, including cases of COVID-19 and pityriasis rosea.25

Urticaria

According to a number of case reports, urticarial lesions have been the first presenting sign of COVID-19 infection, most resolving with antihistamines.10,11 Some patients with more severe symptoms have had widespread urticaria. An urticarial exanthem appearing on the bilateral thighs and buttocks may be the initial sign of infection.12,15 Pruritic erythematous plaques over the face and acral areas is another initial sign. Interestingly, pediatric patients have reported nonpruritic urticaria.9

Urticaria also has been seen as a late dermatologic sign of viral infection. After battling relentless viral infection for 1 month, a pruritic, confluent, ill-defined eruption appeared along a patient’s trunk, back, and proximal extremities. Histopathologic examination concluded a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dilated vessels in the dermis. The urticaria resolved a week later, and the patient’s nasopharyngeal swab finally came back negative.13

Vesiculopapular Eruption

Vesicles mimicking those of chickenpox have been reported. A study of 375 confirmed cases of COVID-19 by Galván Casas et al12 showed a 9% incidence of this vesicular eruption. A study by Sachdeva et al8 revealed vesicular eruptions in 25 of 72 patients. Pruritic papules and vesicles may resemble Grover disease. This cutaneous sign may be seen in the submammary folds, on the hips, or diffusely over the body.

Erythema Multiforme–Like Eruption

Targetoid lesions similar to those of erythema multiforme erupted in 2 of 27 patients with mild COVID-19 infection in a review by Wollina et al.4 In a study of 4 patients with erythema multiforme–like eruptions after COVID-19 symptoms resolved, 3 had palatal petechiae. Two of 4 patients had pseudovesicles in the center of the erythematous targetoid patches.26 Targetoid lesions on the extremities have been reported in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infections. These patients often present without any typical viral symptoms but rather just a febrile exanthem or exanthem alone. Thus, to minimize spread of the virus, it is vital to recognize COVID-19 infection early in patients with a viral exanthem during the time of high COVID-19 incidence.4

Livedo Reticularis

In the United States, a case series reported 2 patients with transient livedo reticularis throughout the course of COVID-19 infection. The cutaneous eruption resembled erythema ab igne, but there was no history of exposure to heat.16

Stellate Purpura

In severe COVID-19 infection, a reticulated nonblanching purpura on the buttocks has been reported to demonstrate pauci-inflammatory vascular thrombosis, complement membrane attack complex deposition, and endothelial injury on dermatopathology. Stellate purpura on palmoplantar surfaces also has shown arterial thrombosis in the deep dermis due to complement deposition.17

Petechiae and Purpura

A morbilliform exanthem may develop into significant petechiae in the popliteal fossae, buttocks, and thighs. A punch biopsy specimen demonstrates a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with erythrocyte extravasation and papillary dermal edema with dyskeratotic cells.18 Purpura of the lower extremities may develop, with histopathology showing fibrinoid necrosis of small vessel walls, neutrophilic infiltrate with karyorrhexis, and granular complement deposition.19

In Thailand, a patient was misdiagnosed with dengue after presenting with petechiae and low platelet count.20 Further progression of the viral illness resulted in respiratory symptoms. Subsequently, the patient tested positive for COVID-19. This case demonstrates that cutaneous signs of many sorts may be the first presenting signs of COVID-19, even prior to febrile symptoms.20

Androgenic Alopecia

Studies have shown that androgens are related in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Coronavirus disease 2019 uses a cellular co-receptor, TMPRSS2, which is androgen regulated.27 In a study of 41 males with COVID-19, 29 had androgenic alopecia. However, this is only a correlation, and causation cannot be concluded here. It cannot be determined from this study whether androgenic alopecia is a risk factor, result of COVID-19, or confounder.28

Exaggerated Herpes Zoster

Shors29 reported a herpes zoster eruption in a patient who had symptoms of COVID-19 for 1 week. Further testing confirmed COVID-19 infection, and despite prompt treatment with valacyclovir, the eruption was slow to resolve. The patient then experienced severe postherpetic neuralgia for more than 4 weeks, even with treatment with gabapentin and lidocaine. It is hypothesized that because of the major inflammatory response caused by COVID-19, an exaggerated inflammation occurred in the dorsal root ganglion, resulting in relentless herpes zoster infection.29

Mottled Skin

Born at term, a 15-day-old neonate presented with sepsis and mottling of the skin. The patient did not have any typical COVID-19 symptoms, such as diarrhea or cough, but tested positive for COVID-19.30

Periorbital Dyschromia

Kalner and Vergilis31 reported 2 cases of periorbital dyschromia prior to any other COVID-19 infection symptoms. The discoloration improved with resolution of ensuing viral symptoms.31

Comment

Many dermatologic signs of COVID-19 have been identified. Their individual frequency and association with viral severity will become more apparent as more cases are reported. So far during this pandemic, common dermatologic manifestations have been polymorphic in clinical presentation.

Onset of Skin Manifestations

The timeline of skin signs and COVID-19 symptoms varies from the first reported sign to weeks after symptom resolution. In the Region of Murcia, Spain, Pérez-Suárez et al14 collected data on cutaneous signs of patients with COVID-19. Of the patients studied, 9 had tests confirming COVID-19 infection. Truncal urticaria, sacral ulcers, acrocyanosis, and erythema multiforme were all reported in patients more than 2 weeks after symptom onset. One case of tinea infection also was reported 4 days after fever and respiratory symptoms began.14

Presentation

Coronavirus disease 2019 has affected the skin of both the central thorax and peripheral locations. In a study of 72 patients with cutaneous signs of COVID-19 by Sachdeva et al,8 a truncal distribution was most common, but 14 patients reported acral site involvement. Sachdeva et al8 reported urticarial reactions in 7 of 72 patients with cutaneous signs. A painful acral cyanosis was seen in 11 of 72 patients. Livedo reticularis presented in 2 patients, and only 1 patient had petechiae. Cutaneous signs were the first indicators of viral infection in 9 of 72 patients; 52 patients presented with respiratory symptoms first. All of the reported cutaneous signs spontaneously resolved within 10 days.8

Recalcati32 reviewed 88 patients with COVID-19, and 18 had cutaneous signs at initial onset of viral infection or during hospitalization. The most common integumentary sign reported in this study was erythema, followed by diffuse urticaria, and then a vesicular eruption resembling varicella infection.32

Some less common phenomena have been identified in patients with COVID-19, including androgenic alopecia, exaggerated herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia, mottled skin, and periorbital dyschromia. Being aware of these complications may help in early treatment, diagnosis, and even prevention of viral spread.

Pathogenesis of Skin Manifestations

Few breakthroughs have been made in understanding the pathogenesis of skin manifestations of SARS-CoV-2. Acral ischemia may be a manifestation of COVID-19’s association with hypercoagulation. Increasing fibrinogen and prothrombin times lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation and microthrombi. These tiny blood clots then lodge in blood vessels and cause acral cyanosis and subsequent gangrene.2 The proposed mechanism behind this clinical manifestation in younger populations is the hypercoagulable state that COVID-19 creates. Conversely, acral erythema and chilblainlike lesions in older patients are thought to be from acral ischemia as a response to insufficient type 1 interferons. This pathophysiologic mechanism is indicative of a worse prognosis due to the large role that type 1 interferons play in antiviral responses. Coronavirus disease 2019 similarly triggers type 1 interferons; thus, their efficacy positively correlates with good disease prognosis.3

Similarly, the pathogenesis for livedo reticularis in patients with COVID-19 can only be hypothesized. Infected patients are in a hypercoagulable state, and in these cases, it was uncertain whether this was due to a disseminated intravascular coagulation, cold agglutinins, cryofibrinogens, or lupus anticoagulant.16

Nonetheless, it can be difficult to separate the primary event between vasculopathy or vasculitis in larger vessel pathology specimens. Some of the studies’ pathology reports discuss a granulocytic infiltrate and red blood cell extravasation, which represent small vessel vasculitis. However, the gangrene and necrosing livedo represent vasculopathy events. A final conclusion about the pathogenesis cannot be made without further clinical and histopathologic evaluation.

Histopathology

Biopsy specimens of reported morbilliform eruptions have demonstrated thrombosed vessels with evidence of necrosis and granulocytic infiltrate.25 Another biopsy specimen of a widespread erythematous exanthem demonstrated extravasated red blood cells and vessel wall damage similar to thrombophilic arteritis. Other reports of histopathology showed necrotic keratinocytes and lymphocytic satellitosis at the dermoepidermal junction, resembling Grover disease. These cases demonstrating necrosis suggest a strong cytokine reaction from the virus.25 A concern with these biopsy findings is that morbilliform eruptions generally show dilated vessels with lymphocytes, and these biopsy findings are consistent with a cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Additionally, histopathologic evaluation of purpuric eruptions has shown erythrocyte extravasation and granulocytic infiltrate indicative of a cutaneous small vessel vasculitis.

Although most reported cases of cutaneous signs of COVID-19 do not have histopathologic reports, Yao et al33 conducted a dermatopathologic study that investigated the tissue in deceased patients who had COVID-19. This pathology showed hyaline thrombi within the small vessels of the skin, likely leading to the painful acral ischemia. Similarly, Yao et al33 reported autopsies finding hyaline thrombi within the small vessels of the lungs. More research should be done to explore this pathogenesis as part of prognostic factors and virulence.

Conclusion

Cutaneous signs may be the first reported symptom of COVID-19 infection, and dermatologists should be prepared to identify them. This review may be used as a guide for physicians to quickly identify potential infection as well as further understand the pathogenesis related to COVID-19. Future research is necessary to determine the dermatologic pathogenesis, infectivity, and prevalence of cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. It also will be important to explore if vasculopathic lesions predict more severe multisystem disease.

The pathogenesis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is not yet completely understood. Thus far, it is known to affect multiple organ systems, including gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular, with typical clinical symptoms of COVID-19 including fever, cough, myalgia, headache, anosmia, and diarrhea.1 This multiorgan attack may be secondary to an exaggerated inflammatory reaction with vasculopathy and possibly a hypercoagulable state. Skin manifestations also are prevalent in COVID-19, and they often result in polymorphous presentations.2 This article aims to summarize cutaneous clinical signs of COVID-19 so that dermatologists can promptly identify and manage COVID-19 and prevent its spread.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted on June 30, 2020. The literature included observational studies, case reports, and literature reviews from January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020. Search terms included COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, and coronavirus used in combination with cutaneous, skin, and dermatology. All of the resulting articles were then reviewed for relevance to the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. Only confirmed cases of COVID-19 infection were included in this review; suspected unconfirmed cases were excluded. Further exclusion criteria included articles that discussed dermatology in the time of COVID-19 that did not explicitly address its cutaneous manifestations. The remaining literature was evaluated to provide dermatologists and patients with a concise resource for the cutaneous signs and symptoms of COVID-19. Data extracted from the literature included geographic region, number of patients with skin findings, status of COVID-19 infection and timeline, and cutaneous signs. If a cutaneous sign was not given a clear diagnosis in the literature, the senior authors (A.L. and J.J.) assigned it to its most similar classification to aid in ease of understanding and clarity for the readers.

Results

A search of the key terms resulted in 75 articles published in the specified date range. After excluding overtly irrelevant articles and dermatologic conditions in the time of COVID-19 without confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, 25 articles ultimately met inclusion criteria. Relevant references from the articles also were explored for cutaneous dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19. Cutaneous manifestations that were repeatedly reported included chilblainlike lesions; acrocyanosis; urticaria; pityriasis rosea–like cutaneous eruption; erythema multiforme–like, vesiculopapular, and morbilliform eruptions; petechiae; livedo reticularis; and purpuric livedo reticularis (dermatologists may label this stellate purpura). Fewer but nonetheless notable cases of androgenic alopecia, periorbital dyschromia, and herpes zoster exacerbations also were documented. The Table summarizes the reported integumentary findings. The eTable groups the common findings and describes patient age, time to onset of cutaneous sign, and any prognostic significance as seen in the literature.

Chilblainlike Lesions and Acrocyanosis

Chilblainlike lesions are edematous eruptions of the fingers and toes. They usually do not scar and are described as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules with possible bullae on the digits. Skin biopsies demonstrate a histopathologic pattern of vacuolar interface dermatitis with necrotic keratinocytes and a thickened basement membrane. Lymphocytic infiltrate presents in a perieccrine distribution, occasionally with plasma cells. The dermatopathologic findings mimic those of chilblain lupus but lack dermal edema.3

These eruptions have been reported in cases of COVID-19 that more frequently affect children and young adults. They usually resolve over the course of viral infection, averaging within 14 days. Chilblainlike eruptions often are associated with pruritus or pain. They commonly are asymmetrical and appear more often on the toes than the fingers.4 In cases of COVID-19 that lack systemic symptoms, chilblainlike lesions have been seen on the dorsal fingers as the first presenting sign of infection.5

Acral erythema and chilblainlike lesions frequently have been associated with milder infection. Another positive prognostic indicator is the manifestation of these signs in younger individuals.3

Morbilliform Exanthem

The morbilliform exanthem associated with COVID-19 also typically presents in patients with milder disease. It often affects the buttocks, lower abdomen, and thighs, but spares the palms, soles, and mucosae.4 This skin sign, which may start out as a generalized morbilliform exanthem, has been seen to morph into macular hemorrhagic purpura on the legs. These cutaneous lesions typically spontaneously resolve.8

In a case report by Najarian,6 a morbilliform exanthem was seen on the legs, arms, and trunk of a patient who was otherwise asymptomatic but tested positive for COVID-19. The morbilliform exanthem then became confluent on the trunk. Notably, the patient reported pain of the hands and feet.6

Another case report described a patient with edematous annular plaques on the palms, neck, and upper extremities who presented solely with fever.7 The biopsy specimen was nonspecific but indicated a viral exanthem. Histopathology showed perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, dermal edema and vacuoles, spongiosis, dyskeratotic basilar keratinocytes, and few neutrophils without eosinophils.7

Eczematous Eruption

A confluent eczematous eruption in the flexural areas, the antecubital fossae, and axillary folds has been found in COVID-19 patients.21,22 An elderly patient with severe COVID-19 developed a squamous erythematous periumbilical patch 1 day after hospital admission. The cutaneous eruption rapidly progressed to digitate scaly plaques on the trunk, thighs, and flank. A biopsy specimen showed epidermal spongiosis, vesicles containing lymphocytes, and Langerhans cells. The upper dermis demonstrated a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.23

Pityriasis Rosea–Like Eruption

In Iran, a COVID-19–infected patient developed an erythematous papulosquamous eruption with a herald patch and trailing scales 3 days after viral symptoms, resembling that of pityriasis rosea.24 Nests of Langerhans cells within the epidermis are seen in many viral exanthems, including cases of COVID-19 and pityriasis rosea.25

Urticaria

According to a number of case reports, urticarial lesions have been the first presenting sign of COVID-19 infection, most resolving with antihistamines.10,11 Some patients with more severe symptoms have had widespread urticaria. An urticarial exanthem appearing on the bilateral thighs and buttocks may be the initial sign of infection.12,15 Pruritic erythematous plaques over the face and acral areas is another initial sign. Interestingly, pediatric patients have reported nonpruritic urticaria.9

Urticaria also has been seen as a late dermatologic sign of viral infection. After battling relentless viral infection for 1 month, a pruritic, confluent, ill-defined eruption appeared along a patient’s trunk, back, and proximal extremities. Histopathologic examination concluded a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dilated vessels in the dermis. The urticaria resolved a week later, and the patient’s nasopharyngeal swab finally came back negative.13

Vesiculopapular Eruption

Vesicles mimicking those of chickenpox have been reported. A study of 375 confirmed cases of COVID-19 by Galván Casas et al12 showed a 9% incidence of this vesicular eruption. A study by Sachdeva et al8 revealed vesicular eruptions in 25 of 72 patients. Pruritic papules and vesicles may resemble Grover disease. This cutaneous sign may be seen in the submammary folds, on the hips, or diffusely over the body.

Erythema Multiforme–Like Eruption

Targetoid lesions similar to those of erythema multiforme erupted in 2 of 27 patients with mild COVID-19 infection in a review by Wollina et al.4 In a study of 4 patients with erythema multiforme–like eruptions after COVID-19 symptoms resolved, 3 had palatal petechiae. Two of 4 patients had pseudovesicles in the center of the erythematous targetoid patches.26 Targetoid lesions on the extremities have been reported in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infections. These patients often present without any typical viral symptoms but rather just a febrile exanthem or exanthem alone. Thus, to minimize spread of the virus, it is vital to recognize COVID-19 infection early in patients with a viral exanthem during the time of high COVID-19 incidence.4

Livedo Reticularis

In the United States, a case series reported 2 patients with transient livedo reticularis throughout the course of COVID-19 infection. The cutaneous eruption resembled erythema ab igne, but there was no history of exposure to heat.16

Stellate Purpura

In severe COVID-19 infection, a reticulated nonblanching purpura on the buttocks has been reported to demonstrate pauci-inflammatory vascular thrombosis, complement membrane attack complex deposition, and endothelial injury on dermatopathology. Stellate purpura on palmoplantar surfaces also has shown arterial thrombosis in the deep dermis due to complement deposition.17

Petechiae and Purpura

A morbilliform exanthem may develop into significant petechiae in the popliteal fossae, buttocks, and thighs. A punch biopsy specimen demonstrates a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with erythrocyte extravasation and papillary dermal edema with dyskeratotic cells.18 Purpura of the lower extremities may develop, with histopathology showing fibrinoid necrosis of small vessel walls, neutrophilic infiltrate with karyorrhexis, and granular complement deposition.19

In Thailand, a patient was misdiagnosed with dengue after presenting with petechiae and low platelet count.20 Further progression of the viral illness resulted in respiratory symptoms. Subsequently, the patient tested positive for COVID-19. This case demonstrates that cutaneous signs of many sorts may be the first presenting signs of COVID-19, even prior to febrile symptoms.20

Androgenic Alopecia

Studies have shown that androgens are related in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Coronavirus disease 2019 uses a cellular co-receptor, TMPRSS2, which is androgen regulated.27 In a study of 41 males with COVID-19, 29 had androgenic alopecia. However, this is only a correlation, and causation cannot be concluded here. It cannot be determined from this study whether androgenic alopecia is a risk factor, result of COVID-19, or confounder.28

Exaggerated Herpes Zoster

Shors29 reported a herpes zoster eruption in a patient who had symptoms of COVID-19 for 1 week. Further testing confirmed COVID-19 infection, and despite prompt treatment with valacyclovir, the eruption was slow to resolve. The patient then experienced severe postherpetic neuralgia for more than 4 weeks, even with treatment with gabapentin and lidocaine. It is hypothesized that because of the major inflammatory response caused by COVID-19, an exaggerated inflammation occurred in the dorsal root ganglion, resulting in relentless herpes zoster infection.29

Mottled Skin

Born at term, a 15-day-old neonate presented with sepsis and mottling of the skin. The patient did not have any typical COVID-19 symptoms, such as diarrhea or cough, but tested positive for COVID-19.30

Periorbital Dyschromia

Kalner and Vergilis31 reported 2 cases of periorbital dyschromia prior to any other COVID-19 infection symptoms. The discoloration improved with resolution of ensuing viral symptoms.31

Comment

Many dermatologic signs of COVID-19 have been identified. Their individual frequency and association with viral severity will become more apparent as more cases are reported. So far during this pandemic, common dermatologic manifestations have been polymorphic in clinical presentation.

Onset of Skin Manifestations

The timeline of skin signs and COVID-19 symptoms varies from the first reported sign to weeks after symptom resolution. In the Region of Murcia, Spain, Pérez-Suárez et al14 collected data on cutaneous signs of patients with COVID-19. Of the patients studied, 9 had tests confirming COVID-19 infection. Truncal urticaria, sacral ulcers, acrocyanosis, and erythema multiforme were all reported in patients more than 2 weeks after symptom onset. One case of tinea infection also was reported 4 days after fever and respiratory symptoms began.14

Presentation

Coronavirus disease 2019 has affected the skin of both the central thorax and peripheral locations. In a study of 72 patients with cutaneous signs of COVID-19 by Sachdeva et al,8 a truncal distribution was most common, but 14 patients reported acral site involvement. Sachdeva et al8 reported urticarial reactions in 7 of 72 patients with cutaneous signs. A painful acral cyanosis was seen in 11 of 72 patients. Livedo reticularis presented in 2 patients, and only 1 patient had petechiae. Cutaneous signs were the first indicators of viral infection in 9 of 72 patients; 52 patients presented with respiratory symptoms first. All of the reported cutaneous signs spontaneously resolved within 10 days.8

Recalcati32 reviewed 88 patients with COVID-19, and 18 had cutaneous signs at initial onset of viral infection or during hospitalization. The most common integumentary sign reported in this study was erythema, followed by diffuse urticaria, and then a vesicular eruption resembling varicella infection.32

Some less common phenomena have been identified in patients with COVID-19, including androgenic alopecia, exaggerated herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia, mottled skin, and periorbital dyschromia. Being aware of these complications may help in early treatment, diagnosis, and even prevention of viral spread.

Pathogenesis of Skin Manifestations

Few breakthroughs have been made in understanding the pathogenesis of skin manifestations of SARS-CoV-2. Acral ischemia may be a manifestation of COVID-19’s association with hypercoagulation. Increasing fibrinogen and prothrombin times lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation and microthrombi. These tiny blood clots then lodge in blood vessels and cause acral cyanosis and subsequent gangrene.2 The proposed mechanism behind this clinical manifestation in younger populations is the hypercoagulable state that COVID-19 creates. Conversely, acral erythema and chilblainlike lesions in older patients are thought to be from acral ischemia as a response to insufficient type 1 interferons. This pathophysiologic mechanism is indicative of a worse prognosis due to the large role that type 1 interferons play in antiviral responses. Coronavirus disease 2019 similarly triggers type 1 interferons; thus, their efficacy positively correlates with good disease prognosis.3

Similarly, the pathogenesis for livedo reticularis in patients with COVID-19 can only be hypothesized. Infected patients are in a hypercoagulable state, and in these cases, it was uncertain whether this was due to a disseminated intravascular coagulation, cold agglutinins, cryofibrinogens, or lupus anticoagulant.16

Nonetheless, it can be difficult to separate the primary event between vasculopathy or vasculitis in larger vessel pathology specimens. Some of the studies’ pathology reports discuss a granulocytic infiltrate and red blood cell extravasation, which represent small vessel vasculitis. However, the gangrene and necrosing livedo represent vasculopathy events. A final conclusion about the pathogenesis cannot be made without further clinical and histopathologic evaluation.

Histopathology

Biopsy specimens of reported morbilliform eruptions have demonstrated thrombosed vessels with evidence of necrosis and granulocytic infiltrate.25 Another biopsy specimen of a widespread erythematous exanthem demonstrated extravasated red blood cells and vessel wall damage similar to thrombophilic arteritis. Other reports of histopathology showed necrotic keratinocytes and lymphocytic satellitosis at the dermoepidermal junction, resembling Grover disease. These cases demonstrating necrosis suggest a strong cytokine reaction from the virus.25 A concern with these biopsy findings is that morbilliform eruptions generally show dilated vessels with lymphocytes, and these biopsy findings are consistent with a cutaneous small vessel vasculitis. Additionally, histopathologic evaluation of purpuric eruptions has shown erythrocyte extravasation and granulocytic infiltrate indicative of a cutaneous small vessel vasculitis.

Although most reported cases of cutaneous signs of COVID-19 do not have histopathologic reports, Yao et al33 conducted a dermatopathologic study that investigated the tissue in deceased patients who had COVID-19. This pathology showed hyaline thrombi within the small vessels of the skin, likely leading to the painful acral ischemia. Similarly, Yao et al33 reported autopsies finding hyaline thrombi within the small vessels of the lungs. More research should be done to explore this pathogenesis as part of prognostic factors and virulence.

Conclusion

Cutaneous signs may be the first reported symptom of COVID-19 infection, and dermatologists should be prepared to identify them. This review may be used as a guide for physicians to quickly identify potential infection as well as further understand the pathogenesis related to COVID-19. Future research is necessary to determine the dermatologic pathogenesis, infectivity, and prevalence of cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19. It also will be important to explore if vasculopathic lesions predict more severe multisystem disease.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506.

- Criado PR, Abdalla BMZ, de Assis IC, et al. Are the cutaneous manifestations during or due to SARS-CoV-2 infection/COVID-19 frequent or not? revision of possible pathophysiologic mechanisms. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:745-756.

- Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D, et al. Coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection–induced chilblains: a case report with histopathological findings. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:489-492.

- Wollina U, Karadag˘ AS, Rowland-Payne C, et al. Cutaneous signs in COVID-19 patients: a review [published online May 10, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13549.

- Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. Two cases of COVID-19 presenting with a clinical picture resembling chilblains: first report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:746-748.

- Najarian DJ. Morbilliform exanthem associated with COVID‐19. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:493-494.

- Amatore F, Macagno N, Mailhe M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection presenting as a febrile rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E304-E306.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81.

- Morey-Olivé M, Espiau M, Mercadal-Hally M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in the current pandemic of coronavirus infection disease (COVID 2019). An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2020;92:374-375.

- van Damme C, Berlingin E, Saussez S, et al. Acute urticaria with pyrexia as the first manifestations of a COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E300-E301.

- Henry D, Ackerman M, Sancelme E, et al. Urticarial eruption in COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:E244-E245.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:71-77.

- Zengarini C, Orioni G, Cascavilla A, et al. Histological pattern in Covid-19-induced viral rash [published online May 2, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16569.

- Pérez-Suárez B, Martínez-Menchón T, Cutillas-Marco E. Skin findings in the COVID-19 pandemic in the Region of Murcia [published online June 12, 2020]. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;155:41-42.

- Quintana-Castanedo L, Feito-Rodríguez M, Valero-López I, et al. Urticarial exanthem as early diagnostic clue for COVID-19 infection [published online April 29, 2020]. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:498-499.

- Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, et al. Reply to: “reply: a dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: transient livedo reticularis” [published online May 7, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E157.