User login

Victorious endurance: To pass the breaking point and not break

I’ve been thinking a lot about endurance recently.

COVID-19 is surging in the United States. Health care workers exhausted from the first and second waves are quickly reaching the verge of collapse. I’m seeing more and more heartbreaking articles about the bone-deep fatigue, fear, and frustration health care workers are facing, and I weep. As horrible as it is to be fighting this terrifying, little-understood, invisible virus, health care workers are also fighting an equally distressing war against misinformation, recklessness, apathy, and outright denial.

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also dealing with racial and social unrest not seen in decades. The most significant cultural divisions and political animosity perhaps since the Civil War. A contested election. The fraying of our democratic institutions and our standing in the global community. The weakest economy since the Great Depression. Record unemployment. Many individuals and families facing or already experiencing eviction and food insecurity. Record-setting fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters that are only projected to intensify due to climate change.

That’s a lot to endure. And we don’t have much choice other than to live through it. Some of us will break under the strain; others will disengage by giving up clinical work or even leaving health care altogether. Some of us will pack it in and retire, walk away from relationships with family members or longtime friends, or even emigrate to another country (New Zealand, anyone?). Some of us will passively hunker down, letting the challenges of this time overwhelm us and just hoping we can hang on long enough to emerge, albeit beaten and scarred, on the other side.

But some of us will experience victorious endurance – the kind that doesn’t just accept suffering but finds a way to triumph over it. I came across the concept of victorious endurance in the Bible, but its origin is earlier, from classical Greece. It comes from the ancient Greek word hupomone, which literally means “abiding under” – as in disciplining oneself to bear up under a trial when one would more naturally rebel, or just give up. The ancient Greeks were big on virtues like self-control, long-suffering, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties; Odysseus was a poster child for hupomone. I believe the concept of victorious endurance can be applicable for people across many belief systems, philosophies, and ways of life.

The late William Barclay, former professor of divinity and biblical criticism at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said of hupomone:

It is untranslatable. It does not describe the frame of mind which can sit down with folded hands and bowed head and let a torrent of troubles sweep over it in passive resignation. It describes the ability to bear things in such a triumphant way that it transfigures them. Chrysostom has a great panegyric on this hupomone. He calls it “the root of all goods, the mother of piety, the fruit that never withers, a fortress that is never taken, a harbour that knows no storms” and “the queen of virtues, the foundation of right actions, peace in war, calm in tempest, security in plots.” It is the courageous and triumphant ability to pass the breaking-point and not to break and always to greet the unseen with a cheer. It is the alchemy which transmutes tribulation into strength and glory.

Barclay further noted that “Cicero defines patientia, its Latin equivalent, as: ‘The voluntary and daily suffering of hard and difficult things, for the sake of honour and usefulness.”

In the midst of the most challenging public health emergency of our lifetimes, I am seeing hospitalists – and nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other health care workers – doing exactly this, every day. I’m so incredibly proud of you all, and thankful beyond words.

I doubt that victorious endurance comes naturally to any of us; it’s something we work at, pursue and nurture. What’s the secret to cultivating victorious endurance in the midst of unimaginable stress? I’m pretty sure there’s no specific formula. I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna or to make light of the tumult and turmoil of these times, but here are a few things that, based on my own experiences, may help cultivate this valuable virtue.

Be part of a support network. In the midst of great stress, and especially during this time of social distancing, it’s especially tempting to just hunker down, close in on ourselves, and shut others out – sometimes even our closest friends and loved ones. Maintaining relationships is just too exhausting. But you need people who can come alongside you and offer words of encouragement when you are at your lowest. And there’s nothing that will bring out the best in you like being there to encourage and support someone else. We all need to both receive and to give emotional support at a time like this.

Take the long view. When we’re in the middle of a serious crisis, it seems like the problems we’re facing will last forever. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel, no port in the storm. But even this pandemic won’t last forever. If we can keep in mind the fact that things will eventually get better and that the current situation isn’t permanent, it can help us maintain our perspective and have more patience with the current dysfunction.

Focus on who you want to be in this moment. This is the hardest time most of us have ever lived through, both professionally and personally. But let me throw you a challenge. When you look back on this time from the perspective of five years from now, or maybe ten, how will you want to remember yourself? Who will you want to have been during this time? Looking back, what will make you proud of how you handled this challenge? Be that person.

Look for things to be thankful for. In the midst of the chaos that is our lives and our work right now, I believe we can still occasionally see moments of grace if we keep our eyes open for them. If we aren’t looking for them, we may miss them entirely. And those small moments of love, touches of compassion, displays of selflessness, and even flashes of victorious endurance in yourself or others are gifts to be treasured and held on to – to give thanks for.

Embrace a cause greater than yourself. May I suggest that one thing that might help our efforts to cultivate the virtue of victorious endurance during difficult times might be to embrace a cause that is bigger than yourself; that is, one that lures you to focus beyond your immediate circumstances? What are you passionate about, outside of your life’s normal routine?

If you don’t have a passion, consider what you might become passionate about, with a little effort. For some of us, like me, this will be our faith in God. For others it may be advocating for an end to racism or for broader social justice issues. Maybe it’s working to overcome our cultural and political divisions or to strengthen the institutions of our democracy. Perhaps it’s getting involved with efforts to mitigate climate change. Maybe it’s reaching out to the homeless or hungry in your own community or mentoring a child who is being left behind by the demands of remote learning.

Or perhaps what you embrace is even closer to home: maybe it’s working to eliminate health disparities in your institution or health system, or figuring out how to use technology and resources differently to improve how care is being delivered during or after this pandemic. Maybe it’s as simple as re-committing yourself to personally care for every patient you see today with the very best you have to offer, and with patience, compassion, and grace.

Find something that sets your heart on fire. Something that makes you want to take this difficult time and “transmute tribulation into strength and glory.” Something that, when you look back on these days, will make you thankful that you didn’t just hunker down and subsist through them. Instead, you accomplished great things; you learned; you contributed; and you grew stronger and better.

That’s victorious endurance.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey. This essay was published initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I’ve been thinking a lot about endurance recently.

COVID-19 is surging in the United States. Health care workers exhausted from the first and second waves are quickly reaching the verge of collapse. I’m seeing more and more heartbreaking articles about the bone-deep fatigue, fear, and frustration health care workers are facing, and I weep. As horrible as it is to be fighting this terrifying, little-understood, invisible virus, health care workers are also fighting an equally distressing war against misinformation, recklessness, apathy, and outright denial.

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also dealing with racial and social unrest not seen in decades. The most significant cultural divisions and political animosity perhaps since the Civil War. A contested election. The fraying of our democratic institutions and our standing in the global community. The weakest economy since the Great Depression. Record unemployment. Many individuals and families facing or already experiencing eviction and food insecurity. Record-setting fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters that are only projected to intensify due to climate change.

That’s a lot to endure. And we don’t have much choice other than to live through it. Some of us will break under the strain; others will disengage by giving up clinical work or even leaving health care altogether. Some of us will pack it in and retire, walk away from relationships with family members or longtime friends, or even emigrate to another country (New Zealand, anyone?). Some of us will passively hunker down, letting the challenges of this time overwhelm us and just hoping we can hang on long enough to emerge, albeit beaten and scarred, on the other side.

But some of us will experience victorious endurance – the kind that doesn’t just accept suffering but finds a way to triumph over it. I came across the concept of victorious endurance in the Bible, but its origin is earlier, from classical Greece. It comes from the ancient Greek word hupomone, which literally means “abiding under” – as in disciplining oneself to bear up under a trial when one would more naturally rebel, or just give up. The ancient Greeks were big on virtues like self-control, long-suffering, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties; Odysseus was a poster child for hupomone. I believe the concept of victorious endurance can be applicable for people across many belief systems, philosophies, and ways of life.

The late William Barclay, former professor of divinity and biblical criticism at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said of hupomone:

It is untranslatable. It does not describe the frame of mind which can sit down with folded hands and bowed head and let a torrent of troubles sweep over it in passive resignation. It describes the ability to bear things in such a triumphant way that it transfigures them. Chrysostom has a great panegyric on this hupomone. He calls it “the root of all goods, the mother of piety, the fruit that never withers, a fortress that is never taken, a harbour that knows no storms” and “the queen of virtues, the foundation of right actions, peace in war, calm in tempest, security in plots.” It is the courageous and triumphant ability to pass the breaking-point and not to break and always to greet the unseen with a cheer. It is the alchemy which transmutes tribulation into strength and glory.

Barclay further noted that “Cicero defines patientia, its Latin equivalent, as: ‘The voluntary and daily suffering of hard and difficult things, for the sake of honour and usefulness.”

In the midst of the most challenging public health emergency of our lifetimes, I am seeing hospitalists – and nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other health care workers – doing exactly this, every day. I’m so incredibly proud of you all, and thankful beyond words.

I doubt that victorious endurance comes naturally to any of us; it’s something we work at, pursue and nurture. What’s the secret to cultivating victorious endurance in the midst of unimaginable stress? I’m pretty sure there’s no specific formula. I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna or to make light of the tumult and turmoil of these times, but here are a few things that, based on my own experiences, may help cultivate this valuable virtue.

Be part of a support network. In the midst of great stress, and especially during this time of social distancing, it’s especially tempting to just hunker down, close in on ourselves, and shut others out – sometimes even our closest friends and loved ones. Maintaining relationships is just too exhausting. But you need people who can come alongside you and offer words of encouragement when you are at your lowest. And there’s nothing that will bring out the best in you like being there to encourage and support someone else. We all need to both receive and to give emotional support at a time like this.

Take the long view. When we’re in the middle of a serious crisis, it seems like the problems we’re facing will last forever. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel, no port in the storm. But even this pandemic won’t last forever. If we can keep in mind the fact that things will eventually get better and that the current situation isn’t permanent, it can help us maintain our perspective and have more patience with the current dysfunction.

Focus on who you want to be in this moment. This is the hardest time most of us have ever lived through, both professionally and personally. But let me throw you a challenge. When you look back on this time from the perspective of five years from now, or maybe ten, how will you want to remember yourself? Who will you want to have been during this time? Looking back, what will make you proud of how you handled this challenge? Be that person.

Look for things to be thankful for. In the midst of the chaos that is our lives and our work right now, I believe we can still occasionally see moments of grace if we keep our eyes open for them. If we aren’t looking for them, we may miss them entirely. And those small moments of love, touches of compassion, displays of selflessness, and even flashes of victorious endurance in yourself or others are gifts to be treasured and held on to – to give thanks for.

Embrace a cause greater than yourself. May I suggest that one thing that might help our efforts to cultivate the virtue of victorious endurance during difficult times might be to embrace a cause that is bigger than yourself; that is, one that lures you to focus beyond your immediate circumstances? What are you passionate about, outside of your life’s normal routine?

If you don’t have a passion, consider what you might become passionate about, with a little effort. For some of us, like me, this will be our faith in God. For others it may be advocating for an end to racism or for broader social justice issues. Maybe it’s working to overcome our cultural and political divisions or to strengthen the institutions of our democracy. Perhaps it’s getting involved with efforts to mitigate climate change. Maybe it’s reaching out to the homeless or hungry in your own community or mentoring a child who is being left behind by the demands of remote learning.

Or perhaps what you embrace is even closer to home: maybe it’s working to eliminate health disparities in your institution or health system, or figuring out how to use technology and resources differently to improve how care is being delivered during or after this pandemic. Maybe it’s as simple as re-committing yourself to personally care for every patient you see today with the very best you have to offer, and with patience, compassion, and grace.

Find something that sets your heart on fire. Something that makes you want to take this difficult time and “transmute tribulation into strength and glory.” Something that, when you look back on these days, will make you thankful that you didn’t just hunker down and subsist through them. Instead, you accomplished great things; you learned; you contributed; and you grew stronger and better.

That’s victorious endurance.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey. This essay was published initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I’ve been thinking a lot about endurance recently.

COVID-19 is surging in the United States. Health care workers exhausted from the first and second waves are quickly reaching the verge of collapse. I’m seeing more and more heartbreaking articles about the bone-deep fatigue, fear, and frustration health care workers are facing, and I weep. As horrible as it is to be fighting this terrifying, little-understood, invisible virus, health care workers are also fighting an equally distressing war against misinformation, recklessness, apathy, and outright denial.

As if that wasn’t enough, we are also dealing with racial and social unrest not seen in decades. The most significant cultural divisions and political animosity perhaps since the Civil War. A contested election. The fraying of our democratic institutions and our standing in the global community. The weakest economy since the Great Depression. Record unemployment. Many individuals and families facing or already experiencing eviction and food insecurity. Record-setting fires, hurricanes, and other natural disasters that are only projected to intensify due to climate change.

That’s a lot to endure. And we don’t have much choice other than to live through it. Some of us will break under the strain; others will disengage by giving up clinical work or even leaving health care altogether. Some of us will pack it in and retire, walk away from relationships with family members or longtime friends, or even emigrate to another country (New Zealand, anyone?). Some of us will passively hunker down, letting the challenges of this time overwhelm us and just hoping we can hang on long enough to emerge, albeit beaten and scarred, on the other side.

But some of us will experience victorious endurance – the kind that doesn’t just accept suffering but finds a way to triumph over it. I came across the concept of victorious endurance in the Bible, but its origin is earlier, from classical Greece. It comes from the ancient Greek word hupomone, which literally means “abiding under” – as in disciplining oneself to bear up under a trial when one would more naturally rebel, or just give up. The ancient Greeks were big on virtues like self-control, long-suffering, and perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable difficulties; Odysseus was a poster child for hupomone. I believe the concept of victorious endurance can be applicable for people across many belief systems, philosophies, and ways of life.

The late William Barclay, former professor of divinity and biblical criticism at the University of Glasgow, Scotland, said of hupomone:

It is untranslatable. It does not describe the frame of mind which can sit down with folded hands and bowed head and let a torrent of troubles sweep over it in passive resignation. It describes the ability to bear things in such a triumphant way that it transfigures them. Chrysostom has a great panegyric on this hupomone. He calls it “the root of all goods, the mother of piety, the fruit that never withers, a fortress that is never taken, a harbour that knows no storms” and “the queen of virtues, the foundation of right actions, peace in war, calm in tempest, security in plots.” It is the courageous and triumphant ability to pass the breaking-point and not to break and always to greet the unseen with a cheer. It is the alchemy which transmutes tribulation into strength and glory.

Barclay further noted that “Cicero defines patientia, its Latin equivalent, as: ‘The voluntary and daily suffering of hard and difficult things, for the sake of honour and usefulness.”

In the midst of the most challenging public health emergency of our lifetimes, I am seeing hospitalists – and nurses, respiratory therapists, and countless other health care workers – doing exactly this, every day. I’m so incredibly proud of you all, and thankful beyond words.

I doubt that victorious endurance comes naturally to any of us; it’s something we work at, pursue and nurture. What’s the secret to cultivating victorious endurance in the midst of unimaginable stress? I’m pretty sure there’s no specific formula. I don’t mean to sound like a Pollyanna or to make light of the tumult and turmoil of these times, but here are a few things that, based on my own experiences, may help cultivate this valuable virtue.

Be part of a support network. In the midst of great stress, and especially during this time of social distancing, it’s especially tempting to just hunker down, close in on ourselves, and shut others out – sometimes even our closest friends and loved ones. Maintaining relationships is just too exhausting. But you need people who can come alongside you and offer words of encouragement when you are at your lowest. And there’s nothing that will bring out the best in you like being there to encourage and support someone else. We all need to both receive and to give emotional support at a time like this.

Take the long view. When we’re in the middle of a serious crisis, it seems like the problems we’re facing will last forever. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel, no port in the storm. But even this pandemic won’t last forever. If we can keep in mind the fact that things will eventually get better and that the current situation isn’t permanent, it can help us maintain our perspective and have more patience with the current dysfunction.

Focus on who you want to be in this moment. This is the hardest time most of us have ever lived through, both professionally and personally. But let me throw you a challenge. When you look back on this time from the perspective of five years from now, or maybe ten, how will you want to remember yourself? Who will you want to have been during this time? Looking back, what will make you proud of how you handled this challenge? Be that person.

Look for things to be thankful for. In the midst of the chaos that is our lives and our work right now, I believe we can still occasionally see moments of grace if we keep our eyes open for them. If we aren’t looking for them, we may miss them entirely. And those small moments of love, touches of compassion, displays of selflessness, and even flashes of victorious endurance in yourself or others are gifts to be treasured and held on to – to give thanks for.

Embrace a cause greater than yourself. May I suggest that one thing that might help our efforts to cultivate the virtue of victorious endurance during difficult times might be to embrace a cause that is bigger than yourself; that is, one that lures you to focus beyond your immediate circumstances? What are you passionate about, outside of your life’s normal routine?

If you don’t have a passion, consider what you might become passionate about, with a little effort. For some of us, like me, this will be our faith in God. For others it may be advocating for an end to racism or for broader social justice issues. Maybe it’s working to overcome our cultural and political divisions or to strengthen the institutions of our democracy. Perhaps it’s getting involved with efforts to mitigate climate change. Maybe it’s reaching out to the homeless or hungry in your own community or mentoring a child who is being left behind by the demands of remote learning.

Or perhaps what you embrace is even closer to home: maybe it’s working to eliminate health disparities in your institution or health system, or figuring out how to use technology and resources differently to improve how care is being delivered during or after this pandemic. Maybe it’s as simple as re-committing yourself to personally care for every patient you see today with the very best you have to offer, and with patience, compassion, and grace.

Find something that sets your heart on fire. Something that makes you want to take this difficult time and “transmute tribulation into strength and glory.” Something that, when you look back on these days, will make you thankful that you didn’t just hunker down and subsist through them. Instead, you accomplished great things; you learned; you contributed; and you grew stronger and better.

That’s victorious endurance.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey. This essay was published initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Increasing racial diversity in hospital medicine’s leadership ranks

Have you ever done something where you’re not quite sure why you did it at the time, but later on you realize it was part of some larger cosmic purpose, and you go, “Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why!”? Call it a fortuitous coincidence. Or a subconscious act of anticipation. Maybe a little push from God.

Last summer, as SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee was planning the State of Hospital Medicine survey for 2020, we received a request from SHM’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Special Interest Group (SIG) to include a series of questions related to hospitalist gender, race and ethnic distribution in the new survey. We’ve generally resisted doing things like this because the SoHM is designed to capture data at the group level, not the individual level – and honestly, it’s as much as a lot of groups can do to tell us reliably how many FTEs they have, much less provide details about individual providers. In addition, the survey is already really long, and we are always looking for ways to make it shorter and easier for participants while still collecting the information report users care most about.

But we wanted to take the asks from the DEI SIG seriously, and as we considered their request, we realized that though it wasn’t practical to collect this information for individual hospital medicine group (HMG) members, we could collect it for group leaders. Little did we know last summer that issues of gender and racial diversity and equity would be so front-and-center right now, as we prepare to release the 2020 SoHM Report in early September. Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why – with the prompting of the DEI SIG – we so fortuitously chose to include those questions this year!

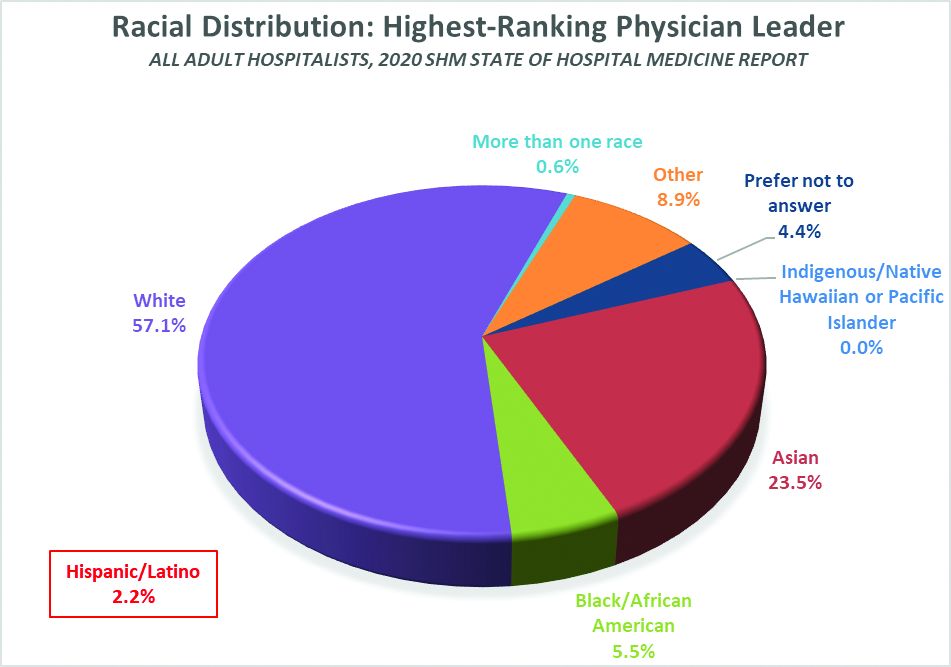

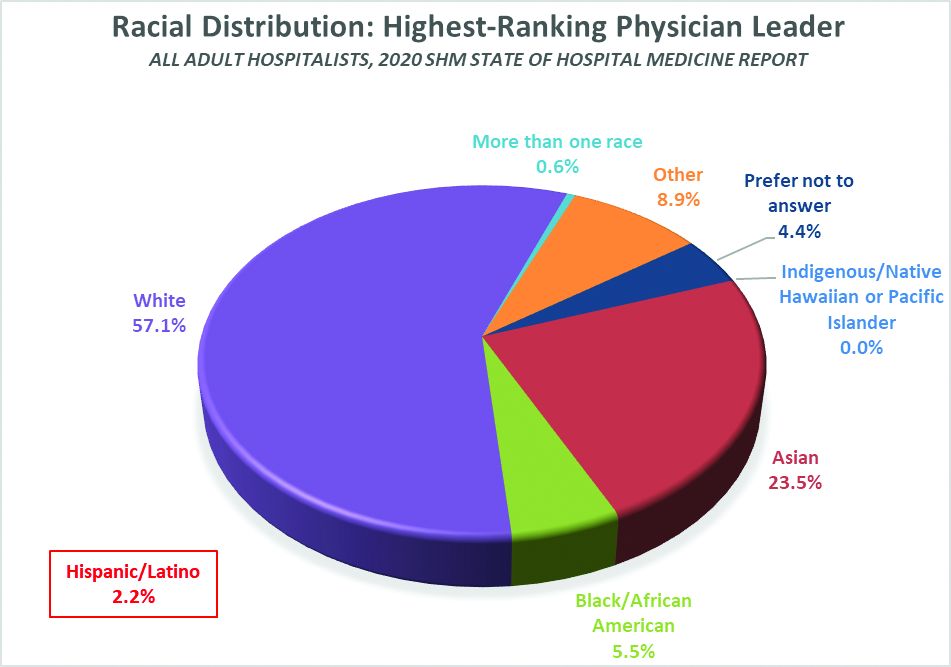

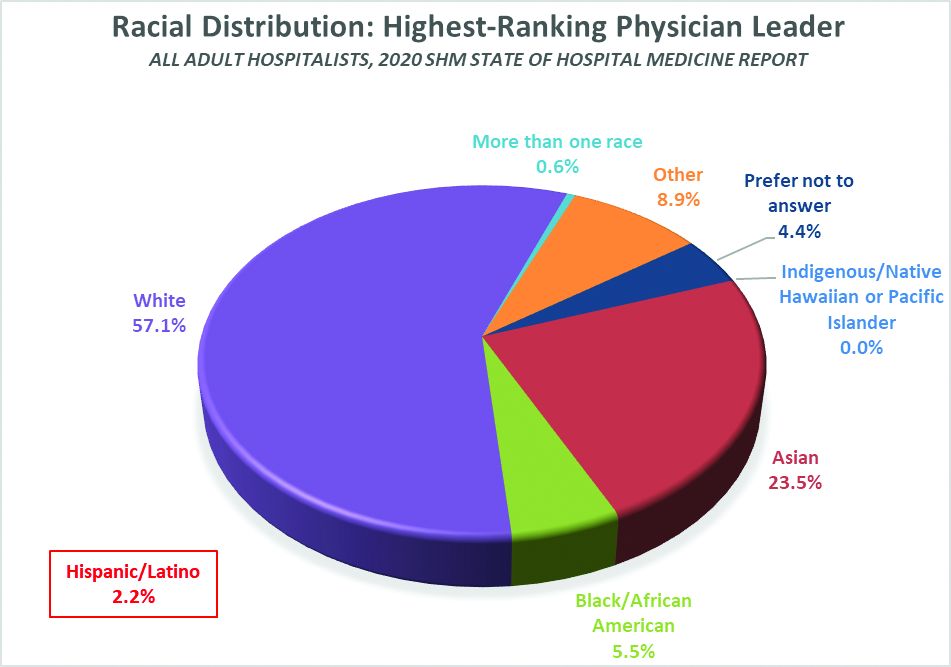

Here’s a sneak preview of what we learned. Among SoHM respondents, 57.1% reported that the highest-ranking leader in their HMG is White, and 23.5% of highest-ranking leaders are Asian. Only 5.5% of HMG leaders were Black/African American. Ethnicity was a separate question, and only 2.2% of HMG leaders were reported as Hispanic/Latino.

I have been profoundly moved by the wretched deaths of George Floyd and other people of color at the hands of police in recent months, and by the subsequent protests and our growing national reckoning over issues of racial equity and justice. In my efforts to understand more about race in America, I have been challenged by my friend Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and others to go beyond just learning about these issues. I want to use my voice to advocate for change, and my actions to participate in effecting change, within the context of my sphere of influence.

So, what does that have to do with the SoHM data on HMG leader demographics? Well, it’s clear that Black and brown people are woefully underrepresented in the ranks of hospital medicine leadership.

Unfortunately, we don’t have good information on racial diversity for hospitalists as a specialty, though I understand that SHM is working on plans to update membership profiles to begin collecting this information. In searching the Internet, I found a 2018 paper from the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that studied racial and ethnic distribution of U.S. primary care physicians (doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036). It reported that, in 2012, 7.8% of general internists were Black, along with 5.8% of family medicine/general practice physicians and 6.8% of pediatricians. A separate data set issued by the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, in 2019, 6.4% of all actively practicing general internal medicine doctors were Black (5.5% of male IM physicians and 7.9% of female IM physicians). While this doesn’t mean hospitalists have the same racial and ethnic distribution, this is probably the best proxy we can come up with.

At first glance, having 5.5% of HMG leaders who are Black doesn’t seem terribly out of line with the reported range of 6.4 to 7.8% in the general population of internal medicine physicians (apologies to the family medicine and pediatric hospitalists reading this, but I’ll confine my discussion to internists for ease and brevity, since they represent the vast majority of the nation’s hospitalists). But do the math. It means Black hospitalists are likely underrepresented in HMG leadership ranks by something like 14% to 29% compared to their likely presence among hospitalists in general.

The real problem, of course, is that according the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black. So even if the racial distribution of HMG leaders catches up to the general hospitalist population, hospital medicine is still woefully underrepresenting the racial and ethnic distribution of our patient population.

The disconnect between the ethnic distribution of HMG leaders vs. hospitalists (based on general internal medicine distribution) is even more pronounced for Latinos. The JHCPU paper reported that, in 2012, 5.6% of general internists were Hispanic. The AAMC data set reported 5.8% of IM doctors were Hispanic/Latino. But only 2.2% of SoHM respondent HMGs reported a Hispanic/Latino leader, which means Latinos are underrepresented by somewhere around 61% or so relative to the likely hospitalist population, and by a whole lot more considering the fact that Latinos make up about 18.5% of the U.S. population.

I’m not saying that a White or Asian doctor can’t provide skilled, compassionate care to a Black or Latino patient, or vice-versa. It happens every day. I guess what I am saying is that we as a country and in the medical profession need to do a better job of creating pathways and promoting careers in medicine for people of color. A JAMA paper from 2019 reported that while the numbers and proportions of minority medical school matriculants has slowly been increasing from 2002 to 2017, the rate of increase was “slower than their age-matched counterparts in the U.S. population, resulting in increased underrepresentation” (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490). This means we’re falling behind, not catching up.

We need to make sure that people like Dr. Ryan Brown aren’t discouraged from pursuing medicine by teachers or school counselors because of their skin color or accent, or their gender or sexual orientation. And among those who become doctors, we need to promote hospital medicine as a desirable specialty for people of color and actively invite them in.

In my view, much of this starts with creating more and better paths to leadership within hospital medicine for people of color. Hospital medicine group leaders wield enormous – and increasing – influence, not only within their HMGs and within SHM, but within their institutions and health care systems. We need their voices and their influence to promote diversity within their groups, their institutions, within hospital medicine, and within medicine and the U.S. health care system more broadly.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is already taking steps to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. These include issuing a formal Diversity and Inclusion Statement, creating the DEI SIG, and the recent formation of a Board-designated DEI task force charged with making recommendations to promote DEI within SHM and in hospital medicine more broadly. But I want to challenge SHM to do more, particularly with regard to promoting diversity in leadership. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Create and sponsor a mentoring program in which hospitalists volunteer to mentor minority junior high and high school students and help them prepare to pursue a career in medicine.

- Develop a formal, structured advocacy or collaboration effort with organizations like AAMC and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designed to promote meaningful increases in the proportion of medical school students and residents who are people of color, and in the proportion who choose primary care – and ultimately, hospital medicine.

- Work hard to collect reliable racial, ethnic and gender information about SHM members and consider collaborating with MGMA to incorporate demographic questions into its survey tool for individual hospitalist compensation and productivity data. Challenge us on the Practice Analysis Committee who are responsible for the SoHM survey to continue surveying leadership demographics, and to consider how we can expand our collection of DEI information in 2022.

- Undertake a public relations campaign to highlight to health systems and other employers the under-representation of Black and Latino hospitalists in leadership positions, and to promote conscious efforts to increase those ranks.

- Create scholarships for hospitalists from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to attend SHM-sponsored leadership development programs such as Leadership Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and Quality and Safety Educators Academy, with the goal of increasing their ranks in positions of influence throughout healthcare. A scholarship program might even include raising funds to help minority hospitalists pursue Master’s-level programs such as an MBA, MHA, or MMM.

- Develop an educational track, mentoring program, or other support initiative for early-career hospitalist leaders and those interested in developing leadership skills, and ensure it gives specific attention to strategies for increasing the proportion of hospitalists of color in leadership positions.

- Review and revise existing SHM documents such as The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group, the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, and various white papers and position statements to ensure they address diversity, equity and inclusion – both with regard to the hospital medicine workforce and leadership, and with regard to patient care and eliminating health disparities.

I’m sure there are plenty of other similar actions we can take that I haven’t thought of. But we need to start the conversation about concrete steps our Society, and the medical specialty we represent, can take to foster real change. And then, we need to follow our words up with actions.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Have you ever done something where you’re not quite sure why you did it at the time, but later on you realize it was part of some larger cosmic purpose, and you go, “Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why!”? Call it a fortuitous coincidence. Or a subconscious act of anticipation. Maybe a little push from God.

Last summer, as SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee was planning the State of Hospital Medicine survey for 2020, we received a request from SHM’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Special Interest Group (SIG) to include a series of questions related to hospitalist gender, race and ethnic distribution in the new survey. We’ve generally resisted doing things like this because the SoHM is designed to capture data at the group level, not the individual level – and honestly, it’s as much as a lot of groups can do to tell us reliably how many FTEs they have, much less provide details about individual providers. In addition, the survey is already really long, and we are always looking for ways to make it shorter and easier for participants while still collecting the information report users care most about.

But we wanted to take the asks from the DEI SIG seriously, and as we considered their request, we realized that though it wasn’t practical to collect this information for individual hospital medicine group (HMG) members, we could collect it for group leaders. Little did we know last summer that issues of gender and racial diversity and equity would be so front-and-center right now, as we prepare to release the 2020 SoHM Report in early September. Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why – with the prompting of the DEI SIG – we so fortuitously chose to include those questions this year!

Here’s a sneak preview of what we learned. Among SoHM respondents, 57.1% reported that the highest-ranking leader in their HMG is White, and 23.5% of highest-ranking leaders are Asian. Only 5.5% of HMG leaders were Black/African American. Ethnicity was a separate question, and only 2.2% of HMG leaders were reported as Hispanic/Latino.

I have been profoundly moved by the wretched deaths of George Floyd and other people of color at the hands of police in recent months, and by the subsequent protests and our growing national reckoning over issues of racial equity and justice. In my efforts to understand more about race in America, I have been challenged by my friend Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and others to go beyond just learning about these issues. I want to use my voice to advocate for change, and my actions to participate in effecting change, within the context of my sphere of influence.

So, what does that have to do with the SoHM data on HMG leader demographics? Well, it’s clear that Black and brown people are woefully underrepresented in the ranks of hospital medicine leadership.

Unfortunately, we don’t have good information on racial diversity for hospitalists as a specialty, though I understand that SHM is working on plans to update membership profiles to begin collecting this information. In searching the Internet, I found a 2018 paper from the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that studied racial and ethnic distribution of U.S. primary care physicians (doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036). It reported that, in 2012, 7.8% of general internists were Black, along with 5.8% of family medicine/general practice physicians and 6.8% of pediatricians. A separate data set issued by the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, in 2019, 6.4% of all actively practicing general internal medicine doctors were Black (5.5% of male IM physicians and 7.9% of female IM physicians). While this doesn’t mean hospitalists have the same racial and ethnic distribution, this is probably the best proxy we can come up with.

At first glance, having 5.5% of HMG leaders who are Black doesn’t seem terribly out of line with the reported range of 6.4 to 7.8% in the general population of internal medicine physicians (apologies to the family medicine and pediatric hospitalists reading this, but I’ll confine my discussion to internists for ease and brevity, since they represent the vast majority of the nation’s hospitalists). But do the math. It means Black hospitalists are likely underrepresented in HMG leadership ranks by something like 14% to 29% compared to their likely presence among hospitalists in general.

The real problem, of course, is that according the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black. So even if the racial distribution of HMG leaders catches up to the general hospitalist population, hospital medicine is still woefully underrepresenting the racial and ethnic distribution of our patient population.

The disconnect between the ethnic distribution of HMG leaders vs. hospitalists (based on general internal medicine distribution) is even more pronounced for Latinos. The JHCPU paper reported that, in 2012, 5.6% of general internists were Hispanic. The AAMC data set reported 5.8% of IM doctors were Hispanic/Latino. But only 2.2% of SoHM respondent HMGs reported a Hispanic/Latino leader, which means Latinos are underrepresented by somewhere around 61% or so relative to the likely hospitalist population, and by a whole lot more considering the fact that Latinos make up about 18.5% of the U.S. population.

I’m not saying that a White or Asian doctor can’t provide skilled, compassionate care to a Black or Latino patient, or vice-versa. It happens every day. I guess what I am saying is that we as a country and in the medical profession need to do a better job of creating pathways and promoting careers in medicine for people of color. A JAMA paper from 2019 reported that while the numbers and proportions of minority medical school matriculants has slowly been increasing from 2002 to 2017, the rate of increase was “slower than their age-matched counterparts in the U.S. population, resulting in increased underrepresentation” (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490). This means we’re falling behind, not catching up.

We need to make sure that people like Dr. Ryan Brown aren’t discouraged from pursuing medicine by teachers or school counselors because of their skin color or accent, or their gender or sexual orientation. And among those who become doctors, we need to promote hospital medicine as a desirable specialty for people of color and actively invite them in.

In my view, much of this starts with creating more and better paths to leadership within hospital medicine for people of color. Hospital medicine group leaders wield enormous – and increasing – influence, not only within their HMGs and within SHM, but within their institutions and health care systems. We need their voices and their influence to promote diversity within their groups, their institutions, within hospital medicine, and within medicine and the U.S. health care system more broadly.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is already taking steps to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. These include issuing a formal Diversity and Inclusion Statement, creating the DEI SIG, and the recent formation of a Board-designated DEI task force charged with making recommendations to promote DEI within SHM and in hospital medicine more broadly. But I want to challenge SHM to do more, particularly with regard to promoting diversity in leadership. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Create and sponsor a mentoring program in which hospitalists volunteer to mentor minority junior high and high school students and help them prepare to pursue a career in medicine.

- Develop a formal, structured advocacy or collaboration effort with organizations like AAMC and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designed to promote meaningful increases in the proportion of medical school students and residents who are people of color, and in the proportion who choose primary care – and ultimately, hospital medicine.

- Work hard to collect reliable racial, ethnic and gender information about SHM members and consider collaborating with MGMA to incorporate demographic questions into its survey tool for individual hospitalist compensation and productivity data. Challenge us on the Practice Analysis Committee who are responsible for the SoHM survey to continue surveying leadership demographics, and to consider how we can expand our collection of DEI information in 2022.

- Undertake a public relations campaign to highlight to health systems and other employers the under-representation of Black and Latino hospitalists in leadership positions, and to promote conscious efforts to increase those ranks.

- Create scholarships for hospitalists from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to attend SHM-sponsored leadership development programs such as Leadership Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and Quality and Safety Educators Academy, with the goal of increasing their ranks in positions of influence throughout healthcare. A scholarship program might even include raising funds to help minority hospitalists pursue Master’s-level programs such as an MBA, MHA, or MMM.

- Develop an educational track, mentoring program, or other support initiative for early-career hospitalist leaders and those interested in developing leadership skills, and ensure it gives specific attention to strategies for increasing the proportion of hospitalists of color in leadership positions.

- Review and revise existing SHM documents such as The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group, the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, and various white papers and position statements to ensure they address diversity, equity and inclusion – both with regard to the hospital medicine workforce and leadership, and with regard to patient care and eliminating health disparities.

I’m sure there are plenty of other similar actions we can take that I haven’t thought of. But we need to start the conversation about concrete steps our Society, and the medical specialty we represent, can take to foster real change. And then, we need to follow our words up with actions.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Have you ever done something where you’re not quite sure why you did it at the time, but later on you realize it was part of some larger cosmic purpose, and you go, “Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why!”? Call it a fortuitous coincidence. Or a subconscious act of anticipation. Maybe a little push from God.

Last summer, as SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee was planning the State of Hospital Medicine survey for 2020, we received a request from SHM’s Diversity, Equity & Inclusion (DEI) Special Interest Group (SIG) to include a series of questions related to hospitalist gender, race and ethnic distribution in the new survey. We’ve generally resisted doing things like this because the SoHM is designed to capture data at the group level, not the individual level – and honestly, it’s as much as a lot of groups can do to tell us reliably how many FTEs they have, much less provide details about individual providers. In addition, the survey is already really long, and we are always looking for ways to make it shorter and easier for participants while still collecting the information report users care most about.

But we wanted to take the asks from the DEI SIG seriously, and as we considered their request, we realized that though it wasn’t practical to collect this information for individual hospital medicine group (HMG) members, we could collect it for group leaders. Little did we know last summer that issues of gender and racial diversity and equity would be so front-and-center right now, as we prepare to release the 2020 SoHM Report in early September. Ahhh, now I understand…that’s why – with the prompting of the DEI SIG – we so fortuitously chose to include those questions this year!

Here’s a sneak preview of what we learned. Among SoHM respondents, 57.1% reported that the highest-ranking leader in their HMG is White, and 23.5% of highest-ranking leaders are Asian. Only 5.5% of HMG leaders were Black/African American. Ethnicity was a separate question, and only 2.2% of HMG leaders were reported as Hispanic/Latino.

I have been profoundly moved by the wretched deaths of George Floyd and other people of color at the hands of police in recent months, and by the subsequent protests and our growing national reckoning over issues of racial equity and justice. In my efforts to understand more about race in America, I have been challenged by my friend Ryan Brown, MD, specialty medical director for hospital medicine with Atrium Health in Charlotte, N.C., and others to go beyond just learning about these issues. I want to use my voice to advocate for change, and my actions to participate in effecting change, within the context of my sphere of influence.

So, what does that have to do with the SoHM data on HMG leader demographics? Well, it’s clear that Black and brown people are woefully underrepresented in the ranks of hospital medicine leadership.

Unfortunately, we don’t have good information on racial diversity for hospitalists as a specialty, though I understand that SHM is working on plans to update membership profiles to begin collecting this information. In searching the Internet, I found a 2018 paper from the Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved that studied racial and ethnic distribution of U.S. primary care physicians (doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036). It reported that, in 2012, 7.8% of general internists were Black, along with 5.8% of family medicine/general practice physicians and 6.8% of pediatricians. A separate data set issued by the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, in 2019, 6.4% of all actively practicing general internal medicine doctors were Black (5.5% of male IM physicians and 7.9% of female IM physicians). While this doesn’t mean hospitalists have the same racial and ethnic distribution, this is probably the best proxy we can come up with.

At first glance, having 5.5% of HMG leaders who are Black doesn’t seem terribly out of line with the reported range of 6.4 to 7.8% in the general population of internal medicine physicians (apologies to the family medicine and pediatric hospitalists reading this, but I’ll confine my discussion to internists for ease and brevity, since they represent the vast majority of the nation’s hospitalists). But do the math. It means Black hospitalists are likely underrepresented in HMG leadership ranks by something like 14% to 29% compared to their likely presence among hospitalists in general.

The real problem, of course, is that according the U.S. Census Bureau, 13.4% of the U.S. population is Black. So even if the racial distribution of HMG leaders catches up to the general hospitalist population, hospital medicine is still woefully underrepresenting the racial and ethnic distribution of our patient population.

The disconnect between the ethnic distribution of HMG leaders vs. hospitalists (based on general internal medicine distribution) is even more pronounced for Latinos. The JHCPU paper reported that, in 2012, 5.6% of general internists were Hispanic. The AAMC data set reported 5.8% of IM doctors were Hispanic/Latino. But only 2.2% of SoHM respondent HMGs reported a Hispanic/Latino leader, which means Latinos are underrepresented by somewhere around 61% or so relative to the likely hospitalist population, and by a whole lot more considering the fact that Latinos make up about 18.5% of the U.S. population.

I’m not saying that a White or Asian doctor can’t provide skilled, compassionate care to a Black or Latino patient, or vice-versa. It happens every day. I guess what I am saying is that we as a country and in the medical profession need to do a better job of creating pathways and promoting careers in medicine for people of color. A JAMA paper from 2019 reported that while the numbers and proportions of minority medical school matriculants has slowly been increasing from 2002 to 2017, the rate of increase was “slower than their age-matched counterparts in the U.S. population, resulting in increased underrepresentation” (doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10490). This means we’re falling behind, not catching up.

We need to make sure that people like Dr. Ryan Brown aren’t discouraged from pursuing medicine by teachers or school counselors because of their skin color or accent, or their gender or sexual orientation. And among those who become doctors, we need to promote hospital medicine as a desirable specialty for people of color and actively invite them in.

In my view, much of this starts with creating more and better paths to leadership within hospital medicine for people of color. Hospital medicine group leaders wield enormous – and increasing – influence, not only within their HMGs and within SHM, but within their institutions and health care systems. We need their voices and their influence to promote diversity within their groups, their institutions, within hospital medicine, and within medicine and the U.S. health care system more broadly.

The Society of Hospital Medicine is already taking steps to promote diversity, equity and inclusion. These include issuing a formal Diversity and Inclusion Statement, creating the DEI SIG, and the recent formation of a Board-designated DEI task force charged with making recommendations to promote DEI within SHM and in hospital medicine more broadly. But I want to challenge SHM to do more, particularly with regard to promoting diversity in leadership. Here are a few ideas to consider:

- Create and sponsor a mentoring program in which hospitalists volunteer to mentor minority junior high and high school students and help them prepare to pursue a career in medicine.

- Develop a formal, structured advocacy or collaboration effort with organizations like AAMC and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designed to promote meaningful increases in the proportion of medical school students and residents who are people of color, and in the proportion who choose primary care – and ultimately, hospital medicine.

- Work hard to collect reliable racial, ethnic and gender information about SHM members and consider collaborating with MGMA to incorporate demographic questions into its survey tool for individual hospitalist compensation and productivity data. Challenge us on the Practice Analysis Committee who are responsible for the SoHM survey to continue surveying leadership demographics, and to consider how we can expand our collection of DEI information in 2022.

- Undertake a public relations campaign to highlight to health systems and other employers the under-representation of Black and Latino hospitalists in leadership positions, and to promote conscious efforts to increase those ranks.

- Create scholarships for hospitalists from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups to attend SHM-sponsored leadership development programs such as Leadership Academy, Academic Hospitalist Academy, and Quality and Safety Educators Academy, with the goal of increasing their ranks in positions of influence throughout healthcare. A scholarship program might even include raising funds to help minority hospitalists pursue Master’s-level programs such as an MBA, MHA, or MMM.

- Develop an educational track, mentoring program, or other support initiative for early-career hospitalist leaders and those interested in developing leadership skills, and ensure it gives specific attention to strategies for increasing the proportion of hospitalists of color in leadership positions.

- Review and revise existing SHM documents such as The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group, the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, and various white papers and position statements to ensure they address diversity, equity and inclusion – both with regard to the hospital medicine workforce and leadership, and with regard to patient care and eliminating health disparities.

I’m sure there are plenty of other similar actions we can take that I haven’t thought of. But we need to start the conversation about concrete steps our Society, and the medical specialty we represent, can take to foster real change. And then, we need to follow our words up with actions.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

Coming soon: The 2020 SoHM Report!

On behalf of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, I am excited to announce the scheduled September 2020 release of the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM)!

For reasons all too familiar, this year’s SoHM survey process was unlike any in SHM’s history. We were still collecting survey responses from a few stragglers in early March when the entire world shut down almost overnight to flatten the curve of a deadly pandemic. Hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders were suddenly either up to their eyeballs trying to figure out how to safely care for huge influxes of COVID-19 patients that overwhelmed established systems of care or were trying to figure out how to staff in a low-volume environment with few COVID patients, a relative trickle of ED admissions, and virtually no surgical care. And everywhere, hospitals and their HMGs were quickly stressed in ways that would have been unimaginable just a couple of months earlier – financially, operationally, epidemiologically, and culturally.

SHM offices closed, with all staff working from home. And the talented people who would normally have been working diligently on the survey data were suddenly redirected to focus on COVID-related issues, including tracking government announcements that were changing daily and providing needed resources to SHM members. By the time they could raise their heads and begin thinking about survey data, we were months behind schedule.

I need to give a huge shout-out to our survey manager extraordinaire Josh Lapps, SHM’s Director of Policy and Practice Management, and his survey support team including Luke Heisinger and Kim Schonberger. Once they were able to turn their focus back to the SoHM, they worked like demons to catch up. And in addition to the work of preparing the SoHM for publication, they helped issue and analyze a follow-up survey to investigate how HMGs adjusted their staffing and operations in response to COVID! As I write this, we appear to be back on schedule for a September SoHM release date, with the COVID supplemental survey report to follow soon after. Thanks also to PAC committee members who, despite their own stresses, rose to the challenge of participating in calls and planning the supplemental survey.

Despite the pandemic, HMGs found survey participation valuable. When all was said and done, we had a respectable number of respondent groups: 502 this year vs. 569 in 2018. Although the number of respondent groups is down, the average group size has increased, so that an all-time high of 10,122 employed/contracted full-time equivalent (FTE) hospitalists (plus 484 locum tenens FTEs) are represented in the data set. The respondents continue to be very diverse, representing all practice models and every state – and even a couple of other countries. One notable change is a significant increase in pediatric HM group participation, thanks to a recruitment charge led by PAC member Sandra Gage, associate division chief of hospital medicine at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, and supported by the inclusion of several new pediatric HM-specific questions to better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices.

We had more multisite respondents than ever, and the multisite respondents overwhelmingly used the new “retake” feature in the online version of the survey. I’m happy to report that we received consistent positive feedback about our new electronic survey platform, and thanks to its capabilities data analysis has been significantly automated, enhancing both efficiency and data reliability.

The survey content is more wide ranging than ever. In addition to the usual topics such as scope of services, staffing and scheduling, compensation models, evaluation and management code distribution, and HM group finances, the 2020 report will include the afore-referenced information about HM groups serving children, expanded information on nurse practitioner (NPs)/physician assistant (PA) roles, and data on diversity in HM physician leadership. The follow-up COVID survey will be published separately as a supplement, available only to purchasers of the SoHM report.

Multiple options for SoHM report purchase. All survey participants will receive access to the online version of the survey. Others may purchase the hard copy report, online access, or both. The report has a colorful, easy-to-read layout, and many of the tables have been streamlined to make them easier to read. I encourage you to sign up to preorder your copy of the SoHM Report today at www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm; you’ll almost certainly discover a treasure trove of worthwhile information.

Use the report to assess how your practice compares to other practices, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be; they only tell you what currently is the case – or at least, what was during the survey period. New best practices not yet reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and that is probably more true today in the new world affected by this pandemic than ever before. And while the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs, it always helps to know how you compare with others. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your hospital medicine practice and, armed with the best available data, are the best judges of what is right for you.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

On behalf of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, I am excited to announce the scheduled September 2020 release of the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM)!

For reasons all too familiar, this year’s SoHM survey process was unlike any in SHM’s history. We were still collecting survey responses from a few stragglers in early March when the entire world shut down almost overnight to flatten the curve of a deadly pandemic. Hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders were suddenly either up to their eyeballs trying to figure out how to safely care for huge influxes of COVID-19 patients that overwhelmed established systems of care or were trying to figure out how to staff in a low-volume environment with few COVID patients, a relative trickle of ED admissions, and virtually no surgical care. And everywhere, hospitals and their HMGs were quickly stressed in ways that would have been unimaginable just a couple of months earlier – financially, operationally, epidemiologically, and culturally.

SHM offices closed, with all staff working from home. And the talented people who would normally have been working diligently on the survey data were suddenly redirected to focus on COVID-related issues, including tracking government announcements that were changing daily and providing needed resources to SHM members. By the time they could raise their heads and begin thinking about survey data, we were months behind schedule.

I need to give a huge shout-out to our survey manager extraordinaire Josh Lapps, SHM’s Director of Policy and Practice Management, and his survey support team including Luke Heisinger and Kim Schonberger. Once they were able to turn their focus back to the SoHM, they worked like demons to catch up. And in addition to the work of preparing the SoHM for publication, they helped issue and analyze a follow-up survey to investigate how HMGs adjusted their staffing and operations in response to COVID! As I write this, we appear to be back on schedule for a September SoHM release date, with the COVID supplemental survey report to follow soon after. Thanks also to PAC committee members who, despite their own stresses, rose to the challenge of participating in calls and planning the supplemental survey.

Despite the pandemic, HMGs found survey participation valuable. When all was said and done, we had a respectable number of respondent groups: 502 this year vs. 569 in 2018. Although the number of respondent groups is down, the average group size has increased, so that an all-time high of 10,122 employed/contracted full-time equivalent (FTE) hospitalists (plus 484 locum tenens FTEs) are represented in the data set. The respondents continue to be very diverse, representing all practice models and every state – and even a couple of other countries. One notable change is a significant increase in pediatric HM group participation, thanks to a recruitment charge led by PAC member Sandra Gage, associate division chief of hospital medicine at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, and supported by the inclusion of several new pediatric HM-specific questions to better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices.

We had more multisite respondents than ever, and the multisite respondents overwhelmingly used the new “retake” feature in the online version of the survey. I’m happy to report that we received consistent positive feedback about our new electronic survey platform, and thanks to its capabilities data analysis has been significantly automated, enhancing both efficiency and data reliability.

The survey content is more wide ranging than ever. In addition to the usual topics such as scope of services, staffing and scheduling, compensation models, evaluation and management code distribution, and HM group finances, the 2020 report will include the afore-referenced information about HM groups serving children, expanded information on nurse practitioner (NPs)/physician assistant (PA) roles, and data on diversity in HM physician leadership. The follow-up COVID survey will be published separately as a supplement, available only to purchasers of the SoHM report.

Multiple options for SoHM report purchase. All survey participants will receive access to the online version of the survey. Others may purchase the hard copy report, online access, or both. The report has a colorful, easy-to-read layout, and many of the tables have been streamlined to make them easier to read. I encourage you to sign up to preorder your copy of the SoHM Report today at www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm; you’ll almost certainly discover a treasure trove of worthwhile information.

Use the report to assess how your practice compares to other practices, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be; they only tell you what currently is the case – or at least, what was during the survey period. New best practices not yet reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and that is probably more true today in the new world affected by this pandemic than ever before. And while the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs, it always helps to know how you compare with others. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your hospital medicine practice and, armed with the best available data, are the best judges of what is right for you.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

On behalf of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, I am excited to announce the scheduled September 2020 release of the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM)!

For reasons all too familiar, this year’s SoHM survey process was unlike any in SHM’s history. We were still collecting survey responses from a few stragglers in early March when the entire world shut down almost overnight to flatten the curve of a deadly pandemic. Hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders were suddenly either up to their eyeballs trying to figure out how to safely care for huge influxes of COVID-19 patients that overwhelmed established systems of care or were trying to figure out how to staff in a low-volume environment with few COVID patients, a relative trickle of ED admissions, and virtually no surgical care. And everywhere, hospitals and their HMGs were quickly stressed in ways that would have been unimaginable just a couple of months earlier – financially, operationally, epidemiologically, and culturally.

SHM offices closed, with all staff working from home. And the talented people who would normally have been working diligently on the survey data were suddenly redirected to focus on COVID-related issues, including tracking government announcements that were changing daily and providing needed resources to SHM members. By the time they could raise their heads and begin thinking about survey data, we were months behind schedule.

I need to give a huge shout-out to our survey manager extraordinaire Josh Lapps, SHM’s Director of Policy and Practice Management, and his survey support team including Luke Heisinger and Kim Schonberger. Once they were able to turn their focus back to the SoHM, they worked like demons to catch up. And in addition to the work of preparing the SoHM for publication, they helped issue and analyze a follow-up survey to investigate how HMGs adjusted their staffing and operations in response to COVID! As I write this, we appear to be back on schedule for a September SoHM release date, with the COVID supplemental survey report to follow soon after. Thanks also to PAC committee members who, despite their own stresses, rose to the challenge of participating in calls and planning the supplemental survey.

Despite the pandemic, HMGs found survey participation valuable. When all was said and done, we had a respectable number of respondent groups: 502 this year vs. 569 in 2018. Although the number of respondent groups is down, the average group size has increased, so that an all-time high of 10,122 employed/contracted full-time equivalent (FTE) hospitalists (plus 484 locum tenens FTEs) are represented in the data set. The respondents continue to be very diverse, representing all practice models and every state – and even a couple of other countries. One notable change is a significant increase in pediatric HM group participation, thanks to a recruitment charge led by PAC member Sandra Gage, associate division chief of hospital medicine at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, and supported by the inclusion of several new pediatric HM-specific questions to better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices.

We had more multisite respondents than ever, and the multisite respondents overwhelmingly used the new “retake” feature in the online version of the survey. I’m happy to report that we received consistent positive feedback about our new electronic survey platform, and thanks to its capabilities data analysis has been significantly automated, enhancing both efficiency and data reliability.

The survey content is more wide ranging than ever. In addition to the usual topics such as scope of services, staffing and scheduling, compensation models, evaluation and management code distribution, and HM group finances, the 2020 report will include the afore-referenced information about HM groups serving children, expanded information on nurse practitioner (NPs)/physician assistant (PA) roles, and data on diversity in HM physician leadership. The follow-up COVID survey will be published separately as a supplement, available only to purchasers of the SoHM report.

Multiple options for SoHM report purchase. All survey participants will receive access to the online version of the survey. Others may purchase the hard copy report, online access, or both. The report has a colorful, easy-to-read layout, and many of the tables have been streamlined to make them easier to read. I encourage you to sign up to preorder your copy of the SoHM Report today at www.hospitalmedicine.org/sohm; you’ll almost certainly discover a treasure trove of worthwhile information.

Use the report to assess how your practice compares to other practices, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be; they only tell you what currently is the case – or at least, what was during the survey period. New best practices not yet reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and that is probably more true today in the new world affected by this pandemic than ever before. And while the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs, it always helps to know how you compare with others. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your hospital medicine practice and, armed with the best available data, are the best judges of what is right for you.

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Conference Committees and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

For everything there is a season

2020 SoHM Survey ready to launch

Wow, the last 2 years have just flown by! I can’t believe it’s already time to launch the Society of Hospital Medicine State of Hospital Medicine survey again! Right now is the season for you to roll up your sleeves and get to work helping SHM develop the nation’s definitive resource on the current state of hospital medicine practice.

I’m really excited about this year’s survey. SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee has redesigned it to eliminate some out-of-date or little-used questions and to add a few new, more relevant questions. Even more exciting, we have a new survey platform that should massively improve your experience of submitting data for the survey and also make the back-end data tabulation and analysis much quicker and more accurate. Multisite groups will now have two options for submitting data – a redesigned, more user-friendly Excel tool, or a new pathway to submit data in the reporting platform by replicating responses.

In addition, our new survey platform should help us produce the final report a little more quickly and improve its usability.

New-for-2020 survey topics will include:

- Expanded information on nurse practitioner/physician assistant roles

- Diversity in hospital medicine physician leadership

- Specific questions for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving children that will better capture unique attributes of these hospital medicine practices

Why participate?

I can’t emphasize enough that each and every survey submission matters a lot. The State of Hospital Medicine report claims to be the authoritative resource for information about the specialty of hospital medicine. But the report can’t fulfill this claim if the underlying data is skimpy because people were too busy, couldn’t be bothered to participate, or if participation is not broadly representative of the amazing diversity of hospital medicine practices out there.

Your participation will help ensure that you are contributing to a robust hospital medicine database, and that your own group’s information is represented in the survey results. By doing so you will be helping to ensure hospital medicine’s place as perhaps the crucial specialty for U.S. health care in the coming decade.

In addition, participants will receive free access to the survey results, so there’s a direct benefit to you and your HMG as well.

How can you participate?

Here’s what you need to know:

1. The survey opens on Jan.6, 2020, and closes on Feb. 14, 2020.

2. You can find general information about the survey at this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/, and register to participate by using this link: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/sohm-survey/.

3. To participate, you’ll want to collect the following general types of information for your hospital medicine group:

- Basic group descriptive information (for example, types of patients seen, number of hospitals covered, teaching status, etc.)

- Scope of clinical services

- Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the HMG

- Full-time equivalent (FTE) information

- Information about the physician leader(s)

- Staffing/scheduling arrangements, including backup plans, paid time off, unfilled positions, predominant scheduling pattern, night coverage arrangements, dedicated admitters, unit-based assignments, etc.

- Compensation model (but not specific amounts)

- Value of employee benefits and CME

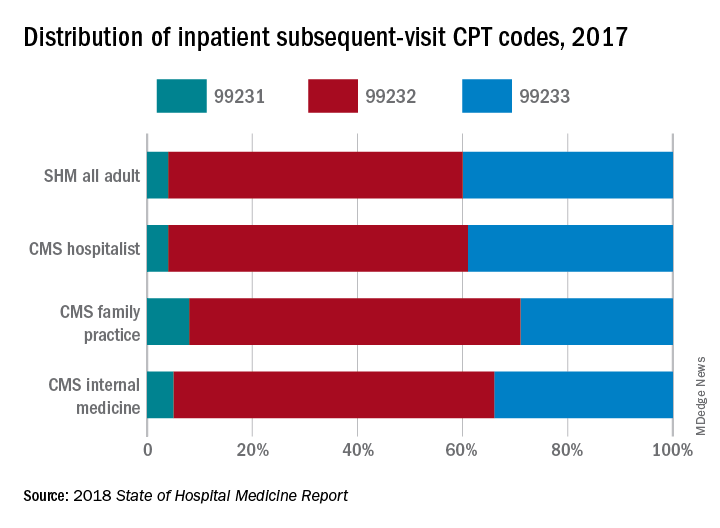

- Total work relative value units generated by the HMG, and number of times the following CPT codes were billed: 99221, 99222, 99223, 99231, 99232, 99233, 99238, 99239

- Information about financial support provided to the HMG

- Specific questions for academic HMGs, including financial support for nonclinical work, and allocation of FTEs

- Specific questions for HMGs serving children, including the hospital settings served, proportion of part-time staff, FTE definition, and information about board certification in pediatric hospital medicine

I’m hoping that all of you will join me in working to make the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine survey and report the best one yet!

Ms. Flores is a partner at Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants in La Quinta, Calif. She serves on SHM’s Practice Analysis and Annual Meeting Committees, and helps to coordinate SHM’s biannual State of Hospital Medicine survey.

2020 SoHM Survey ready to launch

2020 SoHM Survey ready to launch

Wow, the last 2 years have just flown by! I can’t believe it’s already time to launch the Society of Hospital Medicine State of Hospital Medicine survey again! Right now is the season for you to roll up your sleeves and get to work helping SHM develop the nation’s definitive resource on the current state of hospital medicine practice.