User login

Wound Healing on the Dorsal Hands: An Intrapatient Comparison of Primary Closure, Purse-String Closure, and Secondary Intention

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

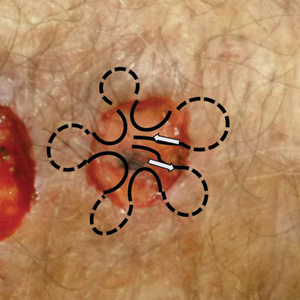

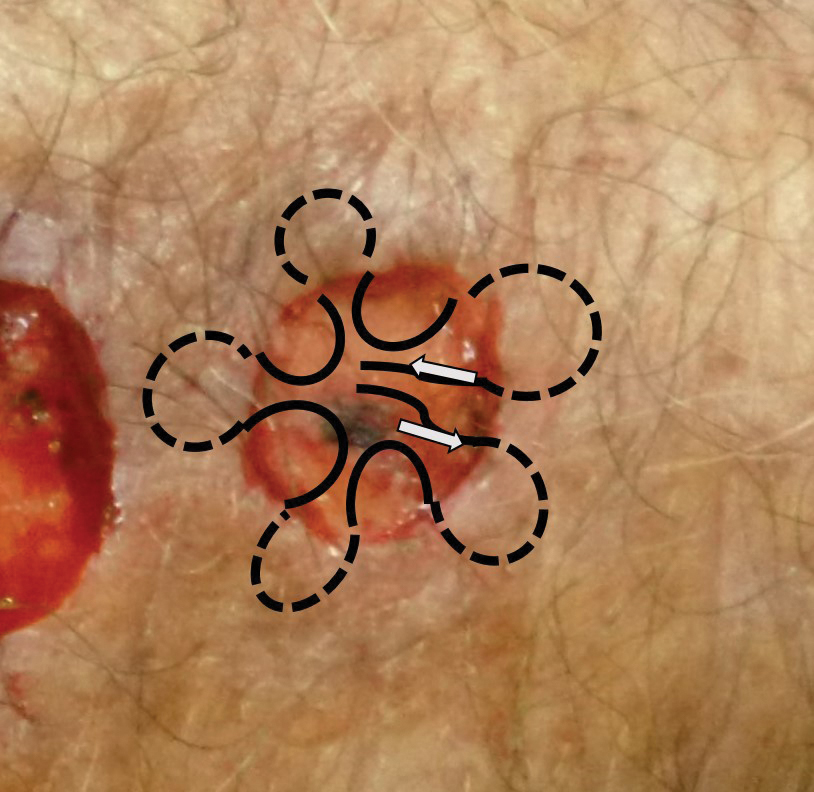

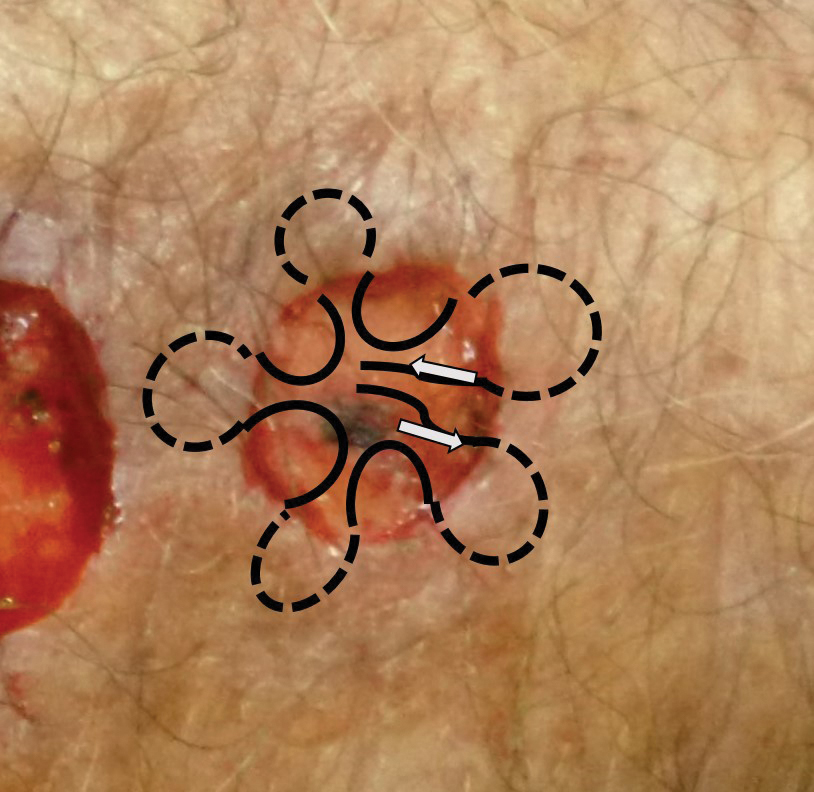

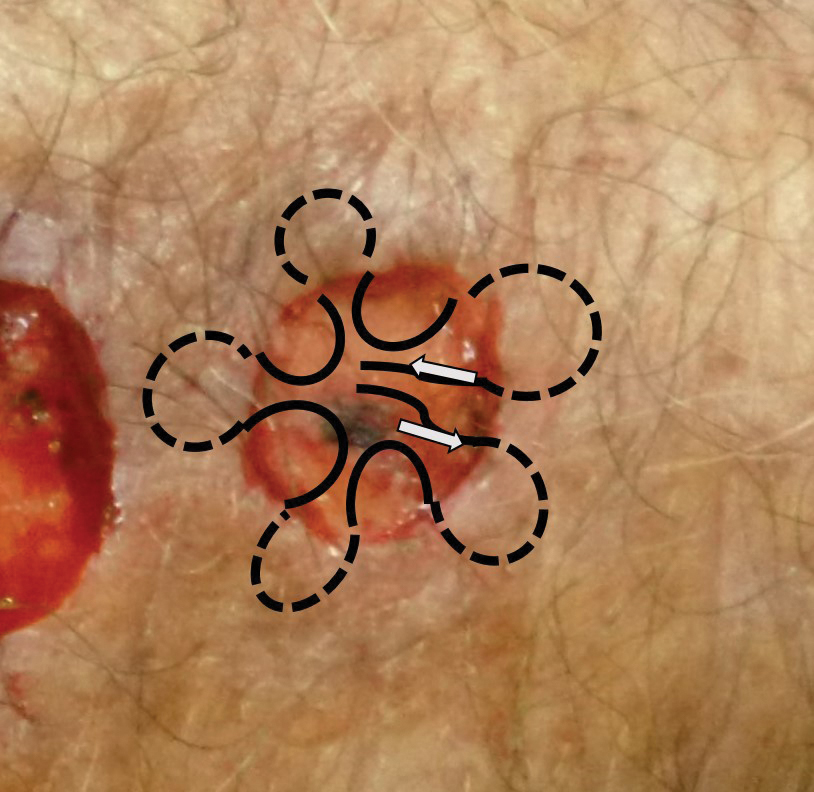

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

What Is Your Diagnosis? Verruciform Xanthoma

An 82-year-old man presented for evaluation of a solitary asymptomatic, pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum that had been present for approximately 1 month. His medical history was notable for Parkinson disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. His current medications included carbidopa-levodopa, lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, and simvastatin.

The Diagnosis: Verruciform Xanthoma

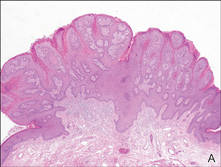

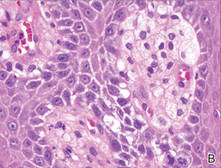

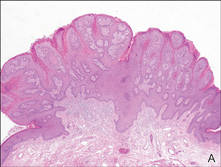

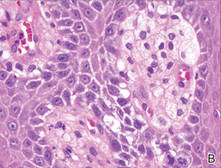

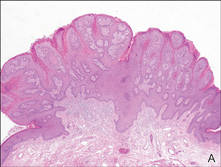

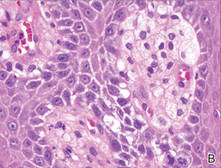

Our patient presented with a solitary asymptomatic, pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum that had been present for approximately 1 month (Figure 1). Biopsy of the specimen showed a lesion with a verrucalike configuration. There was hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and verrucous acanthosis without atypia. The papillary dermis was filled with large histiocytes with foamy cytoplasm (xanthoma cells). A few lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells also were present (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. A solitary pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum. |

|

|

| Figure 2. Biopsy showed a lesion with a verrucalike configuration (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). The papillary dermis was filled with xanthoma cells (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this lesion includes verruciform xanthoma (VX), verruca vulgaris, condyloma, verrucous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma; however, the histologic finding of xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis helped to confirm the diagnosis of VX. Specimens must be evaluated closely to rule out associated or concurrent disease processes.

Verruciform xanthoma is a rare lesion first described by Shafer1 in 1971. It usually appears as a solitary lesion most commonly presenting on the oral mucosa. In 2003, a worldwide survey of the literature profiled a total of 282 oral and 46 extraoral VX lesions.2 Extraoral cutaneous lesions are less common and usually present in the anogenital region, including the penis, scrotum, vulva, and anus. Isolated cases have been reported on the extremities and other sites.3,4 The lesions often are described as pale yellow to pink verrucous papules or plaques. Typical histologic features include hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis without atypia, and xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis that usually do not extend beyond the rete ridges.3,5 A mild inflammatory infiltrate is common with some lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils.3

Several reports have noted that VX does not occur in the presence of any lipid abnormalities or detectable human papillomavirus.3,6-9 Cases may occur sporadically without any apparent associated disease but also have been seen in the setting of atypia, malignancy, and inflammatory processes. There are at least 2 reports of VX lesions occurring with squamous cell carcinoma.5,10 Verruciform xanthoma also has presented in the setting of epidermal nevi, actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, pemphigus, discoid lupus erythematosus, lymphedema, CHILD (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects) syndrome, and recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.6,7 The association of VX with these other diseases has led many authors to believe that it is a reactive phenomenon to chronic inflammation or cutaneous trauma in which degenerating keratinocytes are phagocytosed by dermal macrophages that then become lipid-laden foam cells. Rapid epidermal growth may be a result of cytokines released during this process.4

A Japanese report of several cases of VX with lesions on the scrotum suggested that this rare finding may be caused by chronic pressure associated with the Japanese tradition of sitting on the floor.11 One case occurred with lesions on the penis and perineum 4 years after an incidence of necrotizing fasciitis and skin grafting in the same area. The authors suggested that the severe cutaneous trauma predisposed the patient to forming VX lesions.4 There also have been at least 6 cases of VX reported in immunocompromised patients, specifically in the setting of bone marrow transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus infection, common variable immunodeficiency, and renal transplantation.8 The proportion of immunocompromised cases is greater than expected considering the relatively low prevalence of cutaneous

VX lesions. A possible explanation that is consistent with the proposed reactive mechanism for VX formation is that immunocompromised patients may have a lower number of epidermal Langerhans cells, which results in decreased removal of degenerated keratinocytes and increased dermal macrophage phagocytosis.8

Management of VX lesions usually consists of simple excision. Intraoral excisions have been well documented as curative with rare recurrence2,9; however, there are limited reports in the literature documenting successful excision of cutaneous lesions. Despite the availability of several treatment modalities (eg, wire loop electrosection, pulsed dye laser, radiation therapy, chloroxylenol scrub, wide surgical resection), lesions may reoccur.9 Because VX lesions have occurred in the setting of other cutaneous conditions, patients should be assessed for other concurrent diseases. Biopsy specimens should be carefully analyzed, as a few VX lesions have been associated with epidermal atypia and invasive squamous cell carcinoma.5,10

1. Shafer WG. Verruciform xanthoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;31:784-789.

2. Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Takata T, et al. Verruciform xanthoma—biological profile of 282 oral lesions based on a literature survey with nine new cases from Japan. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:325-336.

3. Sopena J, Gamo R, Iglesias L, et al. Disseminated verruciform xanthoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:717-719.

4. Cumberland L, Dana A, Resh B, et al. Verruciform xanthoma in the setting of cutaneous trauma and chronic inflammation: report of a patient and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:895-900.

5. Mannes KD, Dekle CL, Requena L, et al. Verruciform xanthoma associated with squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:66-69.

6. Orpin SD, Scott IC, Rajaratnam R, et al. A rare case of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa and verruciform xanthoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:49-51.

7. Wu Y, Hsiao P, Lin Y. Verruciform xanthoma-like phenomenon in seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:373-377.

8. Kanitakis J, Euvrard S, Butnaru AC, et al. Verruciform xanthoma of the scrotum in a renal transplant patient. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:161-163.

9. Connolly SB, Lewis EJ, Lindholm JS, et al. Management of cutaneous verruciform xanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:343-347.

10. Takiwaki H, Yokota M, Ahsan K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with verruciform xanthoma of the penis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:551-554.

11. Nakamura S, Kanamori S, Nakayama K, et al. Verruciform xanthoma on the scrotum. J Dermatol. 1989;16:397-401.

An 82-year-old man presented for evaluation of a solitary asymptomatic, pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum that had been present for approximately 1 month. His medical history was notable for Parkinson disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. His current medications included carbidopa-levodopa, lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, and simvastatin.

The Diagnosis: Verruciform Xanthoma

Our patient presented with a solitary asymptomatic, pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum that had been present for approximately 1 month (Figure 1). Biopsy of the specimen showed a lesion with a verrucalike configuration. There was hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and verrucous acanthosis without atypia. The papillary dermis was filled with large histiocytes with foamy cytoplasm (xanthoma cells). A few lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells also were present (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. A solitary pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum. |

|

|

| Figure 2. Biopsy showed a lesion with a verrucalike configuration (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). The papillary dermis was filled with xanthoma cells (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this lesion includes verruciform xanthoma (VX), verruca vulgaris, condyloma, verrucous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma; however, the histologic finding of xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis helped to confirm the diagnosis of VX. Specimens must be evaluated closely to rule out associated or concurrent disease processes.

Verruciform xanthoma is a rare lesion first described by Shafer1 in 1971. It usually appears as a solitary lesion most commonly presenting on the oral mucosa. In 2003, a worldwide survey of the literature profiled a total of 282 oral and 46 extraoral VX lesions.2 Extraoral cutaneous lesions are less common and usually present in the anogenital region, including the penis, scrotum, vulva, and anus. Isolated cases have been reported on the extremities and other sites.3,4 The lesions often are described as pale yellow to pink verrucous papules or plaques. Typical histologic features include hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis without atypia, and xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis that usually do not extend beyond the rete ridges.3,5 A mild inflammatory infiltrate is common with some lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils.3

Several reports have noted that VX does not occur in the presence of any lipid abnormalities or detectable human papillomavirus.3,6-9 Cases may occur sporadically without any apparent associated disease but also have been seen in the setting of atypia, malignancy, and inflammatory processes. There are at least 2 reports of VX lesions occurring with squamous cell carcinoma.5,10 Verruciform xanthoma also has presented in the setting of epidermal nevi, actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, pemphigus, discoid lupus erythematosus, lymphedema, CHILD (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects) syndrome, and recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.6,7 The association of VX with these other diseases has led many authors to believe that it is a reactive phenomenon to chronic inflammation or cutaneous trauma in which degenerating keratinocytes are phagocytosed by dermal macrophages that then become lipid-laden foam cells. Rapid epidermal growth may be a result of cytokines released during this process.4

A Japanese report of several cases of VX with lesions on the scrotum suggested that this rare finding may be caused by chronic pressure associated with the Japanese tradition of sitting on the floor.11 One case occurred with lesions on the penis and perineum 4 years after an incidence of necrotizing fasciitis and skin grafting in the same area. The authors suggested that the severe cutaneous trauma predisposed the patient to forming VX lesions.4 There also have been at least 6 cases of VX reported in immunocompromised patients, specifically in the setting of bone marrow transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus infection, common variable immunodeficiency, and renal transplantation.8 The proportion of immunocompromised cases is greater than expected considering the relatively low prevalence of cutaneous

VX lesions. A possible explanation that is consistent with the proposed reactive mechanism for VX formation is that immunocompromised patients may have a lower number of epidermal Langerhans cells, which results in decreased removal of degenerated keratinocytes and increased dermal macrophage phagocytosis.8

Management of VX lesions usually consists of simple excision. Intraoral excisions have been well documented as curative with rare recurrence2,9; however, there are limited reports in the literature documenting successful excision of cutaneous lesions. Despite the availability of several treatment modalities (eg, wire loop electrosection, pulsed dye laser, radiation therapy, chloroxylenol scrub, wide surgical resection), lesions may reoccur.9 Because VX lesions have occurred in the setting of other cutaneous conditions, patients should be assessed for other concurrent diseases. Biopsy specimens should be carefully analyzed, as a few VX lesions have been associated with epidermal atypia and invasive squamous cell carcinoma.5,10

An 82-year-old man presented for evaluation of a solitary asymptomatic, pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum that had been present for approximately 1 month. His medical history was notable for Parkinson disease, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. His current medications included carbidopa-levodopa, lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide, amlodipine, and simvastatin.

The Diagnosis: Verruciform Xanthoma

Our patient presented with a solitary asymptomatic, pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum that had been present for approximately 1 month (Figure 1). Biopsy of the specimen showed a lesion with a verrucalike configuration. There was hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, and verrucous acanthosis without atypia. The papillary dermis was filled with large histiocytes with foamy cytoplasm (xanthoma cells). A few lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and plasma cells also were present (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. A solitary pink, velvety, exophytic nodule on the scrotum. |

|

|

| Figure 2. Biopsy showed a lesion with a verrucalike configuration (A)(H&E, original magnification ×20). The papillary dermis was filled with xanthoma cells (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this lesion includes verruciform xanthoma (VX), verruca vulgaris, condyloma, verrucous carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma; however, the histologic finding of xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis helped to confirm the diagnosis of VX. Specimens must be evaluated closely to rule out associated or concurrent disease processes.

Verruciform xanthoma is a rare lesion first described by Shafer1 in 1971. It usually appears as a solitary lesion most commonly presenting on the oral mucosa. In 2003, a worldwide survey of the literature profiled a total of 282 oral and 46 extraoral VX lesions.2 Extraoral cutaneous lesions are less common and usually present in the anogenital region, including the penis, scrotum, vulva, and anus. Isolated cases have been reported on the extremities and other sites.3,4 The lesions often are described as pale yellow to pink verrucous papules or plaques. Typical histologic features include hyperkeratosis, focal parakeratosis, acanthosis without atypia, and xanthoma cells in the papillary dermis that usually do not extend beyond the rete ridges.3,5 A mild inflammatory infiltrate is common with some lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils.3

Several reports have noted that VX does not occur in the presence of any lipid abnormalities or detectable human papillomavirus.3,6-9 Cases may occur sporadically without any apparent associated disease but also have been seen in the setting of atypia, malignancy, and inflammatory processes. There are at least 2 reports of VX lesions occurring with squamous cell carcinoma.5,10 Verruciform xanthoma also has presented in the setting of epidermal nevi, actinic keratosis, seborrheic keratosis, lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, pemphigus, discoid lupus erythematosus, lymphedema, CHILD (congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects) syndrome, and recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.6,7 The association of VX with these other diseases has led many authors to believe that it is a reactive phenomenon to chronic inflammation or cutaneous trauma in which degenerating keratinocytes are phagocytosed by dermal macrophages that then become lipid-laden foam cells. Rapid epidermal growth may be a result of cytokines released during this process.4

A Japanese report of several cases of VX with lesions on the scrotum suggested that this rare finding may be caused by chronic pressure associated with the Japanese tradition of sitting on the floor.11 One case occurred with lesions on the penis and perineum 4 years after an incidence of necrotizing fasciitis and skin grafting in the same area. The authors suggested that the severe cutaneous trauma predisposed the patient to forming VX lesions.4 There also have been at least 6 cases of VX reported in immunocompromised patients, specifically in the setting of bone marrow transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus infection, common variable immunodeficiency, and renal transplantation.8 The proportion of immunocompromised cases is greater than expected considering the relatively low prevalence of cutaneous

VX lesions. A possible explanation that is consistent with the proposed reactive mechanism for VX formation is that immunocompromised patients may have a lower number of epidermal Langerhans cells, which results in decreased removal of degenerated keratinocytes and increased dermal macrophage phagocytosis.8

Management of VX lesions usually consists of simple excision. Intraoral excisions have been well documented as curative with rare recurrence2,9; however, there are limited reports in the literature documenting successful excision of cutaneous lesions. Despite the availability of several treatment modalities (eg, wire loop electrosection, pulsed dye laser, radiation therapy, chloroxylenol scrub, wide surgical resection), lesions may reoccur.9 Because VX lesions have occurred in the setting of other cutaneous conditions, patients should be assessed for other concurrent diseases. Biopsy specimens should be carefully analyzed, as a few VX lesions have been associated with epidermal atypia and invasive squamous cell carcinoma.5,10

1. Shafer WG. Verruciform xanthoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;31:784-789.

2. Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Takata T, et al. Verruciform xanthoma—biological profile of 282 oral lesions based on a literature survey with nine new cases from Japan. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:325-336.

3. Sopena J, Gamo R, Iglesias L, et al. Disseminated verruciform xanthoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:717-719.

4. Cumberland L, Dana A, Resh B, et al. Verruciform xanthoma in the setting of cutaneous trauma and chronic inflammation: report of a patient and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:895-900.

5. Mannes KD, Dekle CL, Requena L, et al. Verruciform xanthoma associated with squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:66-69.

6. Orpin SD, Scott IC, Rajaratnam R, et al. A rare case of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa and verruciform xanthoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:49-51.

7. Wu Y, Hsiao P, Lin Y. Verruciform xanthoma-like phenomenon in seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:373-377.

8. Kanitakis J, Euvrard S, Butnaru AC, et al. Verruciform xanthoma of the scrotum in a renal transplant patient. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:161-163.

9. Connolly SB, Lewis EJ, Lindholm JS, et al. Management of cutaneous verruciform xanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:343-347.

10. Takiwaki H, Yokota M, Ahsan K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with verruciform xanthoma of the penis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:551-554.

11. Nakamura S, Kanamori S, Nakayama K, et al. Verruciform xanthoma on the scrotum. J Dermatol. 1989;16:397-401.

1. Shafer WG. Verruciform xanthoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;31:784-789.

2. Philipsen HP, Reichart PA, Takata T, et al. Verruciform xanthoma—biological profile of 282 oral lesions based on a literature survey with nine new cases from Japan. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:325-336.

3. Sopena J, Gamo R, Iglesias L, et al. Disseminated verruciform xanthoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:717-719.

4. Cumberland L, Dana A, Resh B, et al. Verruciform xanthoma in the setting of cutaneous trauma and chronic inflammation: report of a patient and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:895-900.

5. Mannes KD, Dekle CL, Requena L, et al. Verruciform xanthoma associated with squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:66-69.

6. Orpin SD, Scott IC, Rajaratnam R, et al. A rare case of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa and verruciform xanthoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:49-51.

7. Wu Y, Hsiao P, Lin Y. Verruciform xanthoma-like phenomenon in seborrheic keratosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:373-377.

8. Kanitakis J, Euvrard S, Butnaru AC, et al. Verruciform xanthoma of the scrotum in a renal transplant patient. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:161-163.

9. Connolly SB, Lewis EJ, Lindholm JS, et al. Management of cutaneous verruciform xanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:343-347.

10. Takiwaki H, Yokota M, Ahsan K, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with verruciform xanthoma of the penis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:551-554.

11. Nakamura S, Kanamori S, Nakayama K, et al. Verruciform xanthoma on the scrotum. J Dermatol. 1989;16:397-401.