User login

Diabetes’ social determinants: What they mean in our practices

More than many other pregnancy complications, diabetes exemplifies the impact of social determinants of health.

The medical management of diabetes during pregnancy involves major lifestyle changes. Diabetes care is largely a patient-driven social experience involving complex and demanding self-care behaviors and tasks.

The pregnant woman with diabetes is placed on a diet that is often novel to her and may be in conflict with the eating patterns of her family. She is advised to exercise, read nutrition labels, and purchase and cook healthy food. She often has to pick up prescriptions, check finger sticks and log results, accurately draw up insulin, and manage strict schedules.

Management requires a tremendous amount of daily engagement during a period of time that, in and of itself, is cognitively demanding.

Outcomes, in turn, are impacted by social context and social factors – by the patient’s economic stability and the safety and characteristics of her neighborhood, for instance, as well as her work schedule, her social support, and her level of health literacy. Each of these factors can influence behaviors and decision making, and ultimately glycemic control and perinatal outcomes.

The social determinants of diabetes-related health are so individualized and impactful that they must be realized and addressed throughout our care, from the way in which we communicate at the initial prenatal checkup to the support we offer for self-management.

Barriers to diabetes self-care

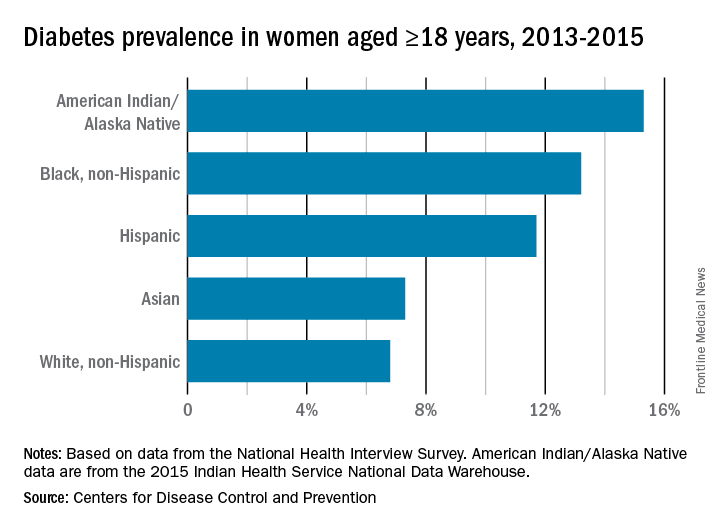

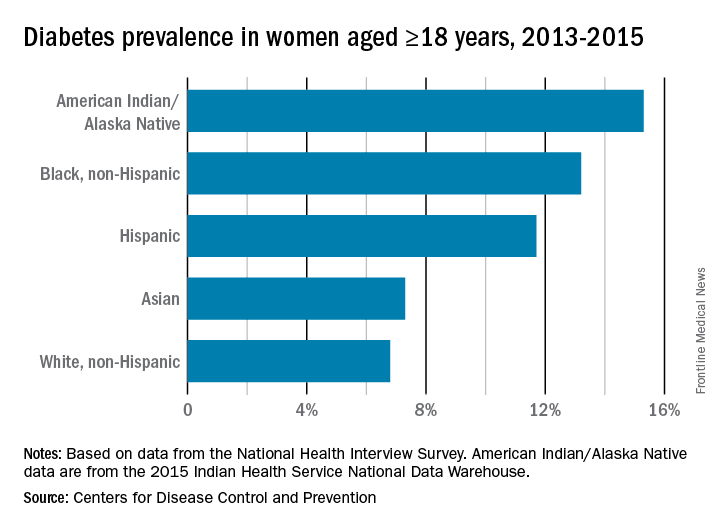

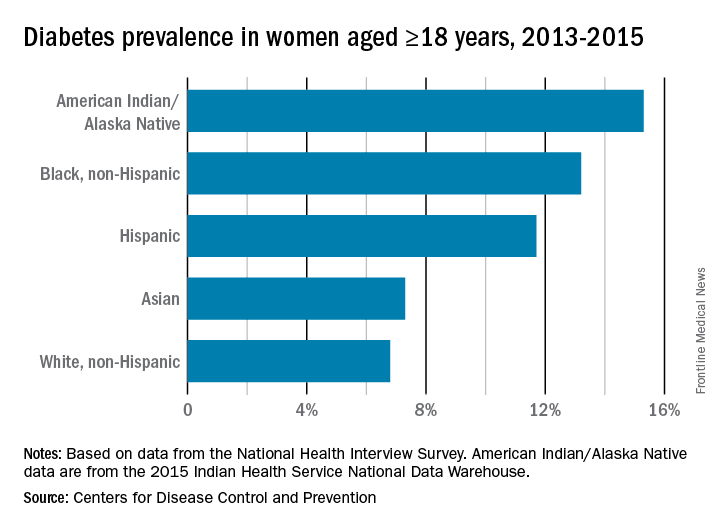

While the incidence of type 2 diabetes is increasing among all social, ethnic, and racial groups, its prevalence among nonpregnant U.S. adults is greatest among racial/ethnic minorities, as well as in individuals with a low-income status. Women who enter pregnancy with preexisting diabetes are more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities.

In pregnancy, minority women (especially Hispanic, but also Asian and non-Hispanic black women), and women with low-income status are similarly predisposed to developing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Social determinants of health are interwoven with inequities stemming from race/ethnicity, income, and other factors that affect outcomes. For example, not only do non-Hispanic black women experience a greater incidence of GDM than non-Hispanic white women, but when they have GDM, they also appear to experience worse pregnancy outcomes compared with white women who also have GDM. In addition, they have a greater likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes after a pregnancy with GDM.

I care for a population that consists largely of minority, low-income women with either gestational or pregestational diabetes. Despite their best intentions and efforts – and despite seemingly high motivation levels – these women struggle to achieve the levels of glycemic control necessary for preventing maternal and fetal complications.

Several years ago, I sought to better understand the barriers to diabetes self-care and behavioral change these women face. Through a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 10 English-speaking women (half with pregestational diabetes) over the course of their pregnancies, we found that the barriers to self-care related to the following: disease novelty, social and economic instability, nutrition challenges, psychological stressors, a failure of outcome expectations, and the burden of disease management (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015 Aug;26[3]:926-40; J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016 Mar;48[3]:170-80.e1).

Some of these barriers, such as the lack of any prior experience with diabetes (through a family member, for instance) or the inability to believe that behavior change and other treatment could impact her diabetes and her fetus’ health, echoed other limited published data. However, women in our study also appeared to be affected by barriers driven by social instability (e.g., a lack of partner or family support, family conflict, or neighborhood violence), inadequate access to healthy food, and the psychological impact of diabetes.

They often felt isolated and overwhelmed by their diabetes; the condition amplified stresses they were already experiencing and contributed to worsening mental health in those who already had depression or anxiety. In the other direction, women also described how preexisting mental health challenges affected their ability to sustain recommended behavior changes.

However, we also identified factors that empowered women in this community to succeed with their diabetes during pregnancy – these included having prior familiarity and diabetes self-efficacy, being motivated by the health of the fetus or older children, having a supportive social and physical environment, and having the ability to self-regulate or set and achieve goals (J Perinatol. 2016 Jan;36[1]:13-8).

To address these barriers, my group has undertaken a series of projects aimed at improving care for pregnant women with diabetes. We developed a diabetes-specific text message support system, for instance, and are now transitioning this support to an advanced mobile health tool that can help patients beyond our site.

What we can do

Much of what we can do in our practices to identify and address social determinants and alleviate barriers to effective diabetes management is about finding the “sweet spot” – about being able to convey the right information in the right amount, with the right timing and the right delivery.

While we can’t improve a woman’s neighborhood or resolve food instability, I believe that we can still work to improve outcomes for women who experience these problems. Here are some key strategies for optimal support of our patients:

Inquire about social factors

Identify hurdles by asking questions such as: Where do you live? Is it safe to walk in your neighborhood? If not, where’s your closest mall? What kind of job do you have, and does your employer allow breaks to take care of your health? How are things going at home? Who is at home to help you? Are you having any trouble affording food? How can we help you learn to adapt your personal or cultural food preferences to healthier options?

Look for small actions to take. I often write letters to my patients’ employers requesting that they be given short, frequent breaks to accommodate their care regimens. I also work to ensure that diet recommendations and medication/insulin regimens are customized for patients with irregular meal and sleep schedules, such as those working night shifts.

Employ a social worker if possible, especially if your practice cares for large numbers of underserved women.

Serve as a resource center, and engage your team in doing so. Be prepared to refer women for social services support, food banks, intimate partner violence support services, and other local resources.

Take a low-health-literacy approach

Health literacy is the ability to obtain and utilize health information. It has been widely investigated outside of pregnancy (and to some extent during pregnancy), and has been found to be at the root of many disparities in health care and health outcomes. Numeracy, a type of health literacy, is the ability to understand numbers, perform basic calculations, and use simple math skills in a way that helps one’s health.

The barriers created by inadequate health literacy are distinct from language barriers. I’ve had patients who can read the labels on their insulin vials but cannot distinguish the short-acting from the long-acting formulation, or who can read the words on a nutrition label but don’t know how to interpret the amount of carbohydrates and determine if a food fits the diet plan.

Moreover, while health literacy is correlated with cognitive ability, it still is a distinct skill set. Studies have shown that patients educated in a traditional sense – college-educated professionals, for instance – will not necessarily understand health-related words and instructions.

Research similarly suggests that a low-health-literacy approach that uses focused, simple, and straightforward messages benefits everyone. This type of approach involves the following:

Simple language

Teach-back techniques (“tell me you what your understanding is of what I just told you”)

Diagrams, handouts, and brochures written at a sixth-grade level.

Teaching that is limited to five to eight key messages per session, and reinforcement of these messages over time.

Promote self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the confidence in one’s ability to perform certain health behaviors. It involves motivation as well as knowledge of the disease, the rationale for treatment, and the specific behaviors that are required for effective self-care.

Help patients understand “why it matters” – that diabetes raises the risk of macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, hypertension, long-term diabetes, and other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Explain basic physiologic concepts and provide background information. This builds self-efficacy.

Do not issue recommendations for exercising and eating well without asking: How can I help you do this? What do you need to be able to eat healthy? Do you need an appointment with a nutritionist? Do you need to see a social worker?

Inquire about and help patients identify supportive family members or other “champions.” Look for ways to incorporate these support people into the patient’s care. At a minimum, encourage the patient to ask her support person to eat healthy with her and/or to understand her daily tasks so that this individual can offer reminders and be a source of support when she feels exhausted or overwhelmed.

If possible, facilitate some type of “diabetes buddy” program to offer peer support and help patients stay engaged in their care, or use group education sessions.

Piggyback on your patients’ own motivating factors. Research has shown that women are extraordinarily motivated to stop smoking during pregnancy because of the health of the fetus. This should extend as well to the difficult lifestyle changes required for diabetes self-care.

View pregnancy as a “golden opportunity” to promote healthy life changes that endure because of the often-extraordinary levels of motivation that women feel or can be encouraged to feel.

Facilitate access

The ability to attend frequent appointments and to juggle the logistics of transportation, child care, and time off work (all part of the burden of disease management) is a social determinant of health. It’s something we should ask about, and it is often something we can positively impact by modifying our practice hours and/or using telehealth or mobile health techniques.

Coordinating newborn and pediatric care with the mother’s subsequent primary care is optimal. Women often prioritize their babies’ health over their own health and they rarely miss pediatric appointments. Coordinating care through medical homes or other mechanisms may help women remain engaged and may lessen the gaps between obstetrical and subsequent primary care.

For me, facilitating doctor-to-doctor transitions sometimes entails picking up the phone or sending communication to a primary care doctor to say, for instance, “I’m worried about my patient’s lifetime risk of type 2 diabetes, and I’d like to hand off her care to you.” This is one of many small but meaningful steps we can take.

Dr. Yee is an assistant professor in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

More than many other pregnancy complications, diabetes exemplifies the impact of social determinants of health.

The medical management of diabetes during pregnancy involves major lifestyle changes. Diabetes care is largely a patient-driven social experience involving complex and demanding self-care behaviors and tasks.

The pregnant woman with diabetes is placed on a diet that is often novel to her and may be in conflict with the eating patterns of her family. She is advised to exercise, read nutrition labels, and purchase and cook healthy food. She often has to pick up prescriptions, check finger sticks and log results, accurately draw up insulin, and manage strict schedules.

Management requires a tremendous amount of daily engagement during a period of time that, in and of itself, is cognitively demanding.

Outcomes, in turn, are impacted by social context and social factors – by the patient’s economic stability and the safety and characteristics of her neighborhood, for instance, as well as her work schedule, her social support, and her level of health literacy. Each of these factors can influence behaviors and decision making, and ultimately glycemic control and perinatal outcomes.

The social determinants of diabetes-related health are so individualized and impactful that they must be realized and addressed throughout our care, from the way in which we communicate at the initial prenatal checkup to the support we offer for self-management.

Barriers to diabetes self-care

While the incidence of type 2 diabetes is increasing among all social, ethnic, and racial groups, its prevalence among nonpregnant U.S. adults is greatest among racial/ethnic minorities, as well as in individuals with a low-income status. Women who enter pregnancy with preexisting diabetes are more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities.

In pregnancy, minority women (especially Hispanic, but also Asian and non-Hispanic black women), and women with low-income status are similarly predisposed to developing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Social determinants of health are interwoven with inequities stemming from race/ethnicity, income, and other factors that affect outcomes. For example, not only do non-Hispanic black women experience a greater incidence of GDM than non-Hispanic white women, but when they have GDM, they also appear to experience worse pregnancy outcomes compared with white women who also have GDM. In addition, they have a greater likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes after a pregnancy with GDM.

I care for a population that consists largely of minority, low-income women with either gestational or pregestational diabetes. Despite their best intentions and efforts – and despite seemingly high motivation levels – these women struggle to achieve the levels of glycemic control necessary for preventing maternal and fetal complications.

Several years ago, I sought to better understand the barriers to diabetes self-care and behavioral change these women face. Through a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 10 English-speaking women (half with pregestational diabetes) over the course of their pregnancies, we found that the barriers to self-care related to the following: disease novelty, social and economic instability, nutrition challenges, psychological stressors, a failure of outcome expectations, and the burden of disease management (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015 Aug;26[3]:926-40; J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016 Mar;48[3]:170-80.e1).

Some of these barriers, such as the lack of any prior experience with diabetes (through a family member, for instance) or the inability to believe that behavior change and other treatment could impact her diabetes and her fetus’ health, echoed other limited published data. However, women in our study also appeared to be affected by barriers driven by social instability (e.g., a lack of partner or family support, family conflict, or neighborhood violence), inadequate access to healthy food, and the psychological impact of diabetes.

They often felt isolated and overwhelmed by their diabetes; the condition amplified stresses they were already experiencing and contributed to worsening mental health in those who already had depression or anxiety. In the other direction, women also described how preexisting mental health challenges affected their ability to sustain recommended behavior changes.

However, we also identified factors that empowered women in this community to succeed with their diabetes during pregnancy – these included having prior familiarity and diabetes self-efficacy, being motivated by the health of the fetus or older children, having a supportive social and physical environment, and having the ability to self-regulate or set and achieve goals (J Perinatol. 2016 Jan;36[1]:13-8).

To address these barriers, my group has undertaken a series of projects aimed at improving care for pregnant women with diabetes. We developed a diabetes-specific text message support system, for instance, and are now transitioning this support to an advanced mobile health tool that can help patients beyond our site.

What we can do

Much of what we can do in our practices to identify and address social determinants and alleviate barriers to effective diabetes management is about finding the “sweet spot” – about being able to convey the right information in the right amount, with the right timing and the right delivery.

While we can’t improve a woman’s neighborhood or resolve food instability, I believe that we can still work to improve outcomes for women who experience these problems. Here are some key strategies for optimal support of our patients:

Inquire about social factors

Identify hurdles by asking questions such as: Where do you live? Is it safe to walk in your neighborhood? If not, where’s your closest mall? What kind of job do you have, and does your employer allow breaks to take care of your health? How are things going at home? Who is at home to help you? Are you having any trouble affording food? How can we help you learn to adapt your personal or cultural food preferences to healthier options?

Look for small actions to take. I often write letters to my patients’ employers requesting that they be given short, frequent breaks to accommodate their care regimens. I also work to ensure that diet recommendations and medication/insulin regimens are customized for patients with irregular meal and sleep schedules, such as those working night shifts.

Employ a social worker if possible, especially if your practice cares for large numbers of underserved women.

Serve as a resource center, and engage your team in doing so. Be prepared to refer women for social services support, food banks, intimate partner violence support services, and other local resources.

Take a low-health-literacy approach

Health literacy is the ability to obtain and utilize health information. It has been widely investigated outside of pregnancy (and to some extent during pregnancy), and has been found to be at the root of many disparities in health care and health outcomes. Numeracy, a type of health literacy, is the ability to understand numbers, perform basic calculations, and use simple math skills in a way that helps one’s health.

The barriers created by inadequate health literacy are distinct from language barriers. I’ve had patients who can read the labels on their insulin vials but cannot distinguish the short-acting from the long-acting formulation, or who can read the words on a nutrition label but don’t know how to interpret the amount of carbohydrates and determine if a food fits the diet plan.

Moreover, while health literacy is correlated with cognitive ability, it still is a distinct skill set. Studies have shown that patients educated in a traditional sense – college-educated professionals, for instance – will not necessarily understand health-related words and instructions.

Research similarly suggests that a low-health-literacy approach that uses focused, simple, and straightforward messages benefits everyone. This type of approach involves the following:

Simple language

Teach-back techniques (“tell me you what your understanding is of what I just told you”)

Diagrams, handouts, and brochures written at a sixth-grade level.

Teaching that is limited to five to eight key messages per session, and reinforcement of these messages over time.

Promote self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the confidence in one’s ability to perform certain health behaviors. It involves motivation as well as knowledge of the disease, the rationale for treatment, and the specific behaviors that are required for effective self-care.

Help patients understand “why it matters” – that diabetes raises the risk of macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, hypertension, long-term diabetes, and other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Explain basic physiologic concepts and provide background information. This builds self-efficacy.

Do not issue recommendations for exercising and eating well without asking: How can I help you do this? What do you need to be able to eat healthy? Do you need an appointment with a nutritionist? Do you need to see a social worker?

Inquire about and help patients identify supportive family members or other “champions.” Look for ways to incorporate these support people into the patient’s care. At a minimum, encourage the patient to ask her support person to eat healthy with her and/or to understand her daily tasks so that this individual can offer reminders and be a source of support when she feels exhausted or overwhelmed.

If possible, facilitate some type of “diabetes buddy” program to offer peer support and help patients stay engaged in their care, or use group education sessions.

Piggyback on your patients’ own motivating factors. Research has shown that women are extraordinarily motivated to stop smoking during pregnancy because of the health of the fetus. This should extend as well to the difficult lifestyle changes required for diabetes self-care.

View pregnancy as a “golden opportunity” to promote healthy life changes that endure because of the often-extraordinary levels of motivation that women feel or can be encouraged to feel.

Facilitate access

The ability to attend frequent appointments and to juggle the logistics of transportation, child care, and time off work (all part of the burden of disease management) is a social determinant of health. It’s something we should ask about, and it is often something we can positively impact by modifying our practice hours and/or using telehealth or mobile health techniques.

Coordinating newborn and pediatric care with the mother’s subsequent primary care is optimal. Women often prioritize their babies’ health over their own health and they rarely miss pediatric appointments. Coordinating care through medical homes or other mechanisms may help women remain engaged and may lessen the gaps between obstetrical and subsequent primary care.

For me, facilitating doctor-to-doctor transitions sometimes entails picking up the phone or sending communication to a primary care doctor to say, for instance, “I’m worried about my patient’s lifetime risk of type 2 diabetes, and I’d like to hand off her care to you.” This is one of many small but meaningful steps we can take.

Dr. Yee is an assistant professor in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

More than many other pregnancy complications, diabetes exemplifies the impact of social determinants of health.

The medical management of diabetes during pregnancy involves major lifestyle changes. Diabetes care is largely a patient-driven social experience involving complex and demanding self-care behaviors and tasks.

The pregnant woman with diabetes is placed on a diet that is often novel to her and may be in conflict with the eating patterns of her family. She is advised to exercise, read nutrition labels, and purchase and cook healthy food. She often has to pick up prescriptions, check finger sticks and log results, accurately draw up insulin, and manage strict schedules.

Management requires a tremendous amount of daily engagement during a period of time that, in and of itself, is cognitively demanding.

Outcomes, in turn, are impacted by social context and social factors – by the patient’s economic stability and the safety and characteristics of her neighborhood, for instance, as well as her work schedule, her social support, and her level of health literacy. Each of these factors can influence behaviors and decision making, and ultimately glycemic control and perinatal outcomes.

The social determinants of diabetes-related health are so individualized and impactful that they must be realized and addressed throughout our care, from the way in which we communicate at the initial prenatal checkup to the support we offer for self-management.

Barriers to diabetes self-care

While the incidence of type 2 diabetes is increasing among all social, ethnic, and racial groups, its prevalence among nonpregnant U.S. adults is greatest among racial/ethnic minorities, as well as in individuals with a low-income status. Women who enter pregnancy with preexisting diabetes are more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities.

In pregnancy, minority women (especially Hispanic, but also Asian and non-Hispanic black women), and women with low-income status are similarly predisposed to developing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Social determinants of health are interwoven with inequities stemming from race/ethnicity, income, and other factors that affect outcomes. For example, not only do non-Hispanic black women experience a greater incidence of GDM than non-Hispanic white women, but when they have GDM, they also appear to experience worse pregnancy outcomes compared with white women who also have GDM. In addition, they have a greater likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes after a pregnancy with GDM.

I care for a population that consists largely of minority, low-income women with either gestational or pregestational diabetes. Despite their best intentions and efforts – and despite seemingly high motivation levels – these women struggle to achieve the levels of glycemic control necessary for preventing maternal and fetal complications.

Several years ago, I sought to better understand the barriers to diabetes self-care and behavioral change these women face. Through a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 10 English-speaking women (half with pregestational diabetes) over the course of their pregnancies, we found that the barriers to self-care related to the following: disease novelty, social and economic instability, nutrition challenges, psychological stressors, a failure of outcome expectations, and the burden of disease management (J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015 Aug;26[3]:926-40; J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016 Mar;48[3]:170-80.e1).

Some of these barriers, such as the lack of any prior experience with diabetes (through a family member, for instance) or the inability to believe that behavior change and other treatment could impact her diabetes and her fetus’ health, echoed other limited published data. However, women in our study also appeared to be affected by barriers driven by social instability (e.g., a lack of partner or family support, family conflict, or neighborhood violence), inadequate access to healthy food, and the psychological impact of diabetes.

They often felt isolated and overwhelmed by their diabetes; the condition amplified stresses they were already experiencing and contributed to worsening mental health in those who already had depression or anxiety. In the other direction, women also described how preexisting mental health challenges affected their ability to sustain recommended behavior changes.

However, we also identified factors that empowered women in this community to succeed with their diabetes during pregnancy – these included having prior familiarity and diabetes self-efficacy, being motivated by the health of the fetus or older children, having a supportive social and physical environment, and having the ability to self-regulate or set and achieve goals (J Perinatol. 2016 Jan;36[1]:13-8).

To address these barriers, my group has undertaken a series of projects aimed at improving care for pregnant women with diabetes. We developed a diabetes-specific text message support system, for instance, and are now transitioning this support to an advanced mobile health tool that can help patients beyond our site.

What we can do

Much of what we can do in our practices to identify and address social determinants and alleviate barriers to effective diabetes management is about finding the “sweet spot” – about being able to convey the right information in the right amount, with the right timing and the right delivery.

While we can’t improve a woman’s neighborhood or resolve food instability, I believe that we can still work to improve outcomes for women who experience these problems. Here are some key strategies for optimal support of our patients:

Inquire about social factors

Identify hurdles by asking questions such as: Where do you live? Is it safe to walk in your neighborhood? If not, where’s your closest mall? What kind of job do you have, and does your employer allow breaks to take care of your health? How are things going at home? Who is at home to help you? Are you having any trouble affording food? How can we help you learn to adapt your personal or cultural food preferences to healthier options?

Look for small actions to take. I often write letters to my patients’ employers requesting that they be given short, frequent breaks to accommodate their care regimens. I also work to ensure that diet recommendations and medication/insulin regimens are customized for patients with irregular meal and sleep schedules, such as those working night shifts.

Employ a social worker if possible, especially if your practice cares for large numbers of underserved women.

Serve as a resource center, and engage your team in doing so. Be prepared to refer women for social services support, food banks, intimate partner violence support services, and other local resources.

Take a low-health-literacy approach

Health literacy is the ability to obtain and utilize health information. It has been widely investigated outside of pregnancy (and to some extent during pregnancy), and has been found to be at the root of many disparities in health care and health outcomes. Numeracy, a type of health literacy, is the ability to understand numbers, perform basic calculations, and use simple math skills in a way that helps one’s health.

The barriers created by inadequate health literacy are distinct from language barriers. I’ve had patients who can read the labels on their insulin vials but cannot distinguish the short-acting from the long-acting formulation, or who can read the words on a nutrition label but don’t know how to interpret the amount of carbohydrates and determine if a food fits the diet plan.

Moreover, while health literacy is correlated with cognitive ability, it still is a distinct skill set. Studies have shown that patients educated in a traditional sense – college-educated professionals, for instance – will not necessarily understand health-related words and instructions.

Research similarly suggests that a low-health-literacy approach that uses focused, simple, and straightforward messages benefits everyone. This type of approach involves the following:

Simple language

Teach-back techniques (“tell me you what your understanding is of what I just told you”)

Diagrams, handouts, and brochures written at a sixth-grade level.

Teaching that is limited to five to eight key messages per session, and reinforcement of these messages over time.

Promote self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the confidence in one’s ability to perform certain health behaviors. It involves motivation as well as knowledge of the disease, the rationale for treatment, and the specific behaviors that are required for effective self-care.

Help patients understand “why it matters” – that diabetes raises the risk of macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, hypertension, long-term diabetes, and other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Explain basic physiologic concepts and provide background information. This builds self-efficacy.

Do not issue recommendations for exercising and eating well without asking: How can I help you do this? What do you need to be able to eat healthy? Do you need an appointment with a nutritionist? Do you need to see a social worker?

Inquire about and help patients identify supportive family members or other “champions.” Look for ways to incorporate these support people into the patient’s care. At a minimum, encourage the patient to ask her support person to eat healthy with her and/or to understand her daily tasks so that this individual can offer reminders and be a source of support when she feels exhausted or overwhelmed.

If possible, facilitate some type of “diabetes buddy” program to offer peer support and help patients stay engaged in their care, or use group education sessions.

Piggyback on your patients’ own motivating factors. Research has shown that women are extraordinarily motivated to stop smoking during pregnancy because of the health of the fetus. This should extend as well to the difficult lifestyle changes required for diabetes self-care.

View pregnancy as a “golden opportunity” to promote healthy life changes that endure because of the often-extraordinary levels of motivation that women feel or can be encouraged to feel.

Facilitate access

The ability to attend frequent appointments and to juggle the logistics of transportation, child care, and time off work (all part of the burden of disease management) is a social determinant of health. It’s something we should ask about, and it is often something we can positively impact by modifying our practice hours and/or using telehealth or mobile health techniques.

Coordinating newborn and pediatric care with the mother’s subsequent primary care is optimal. Women often prioritize their babies’ health over their own health and they rarely miss pediatric appointments. Coordinating care through medical homes or other mechanisms may help women remain engaged and may lessen the gaps between obstetrical and subsequent primary care.

For me, facilitating doctor-to-doctor transitions sometimes entails picking up the phone or sending communication to a primary care doctor to say, for instance, “I’m worried about my patient’s lifetime risk of type 2 diabetes, and I’d like to hand off her care to you.” This is one of many small but meaningful steps we can take.

Dr. Yee is an assistant professor in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Northwestern University, Chicago. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.