User login

Top DEI Topics to Incorporate Into Dermatology Residency Training: An Electronic Delphi Consensus Study

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

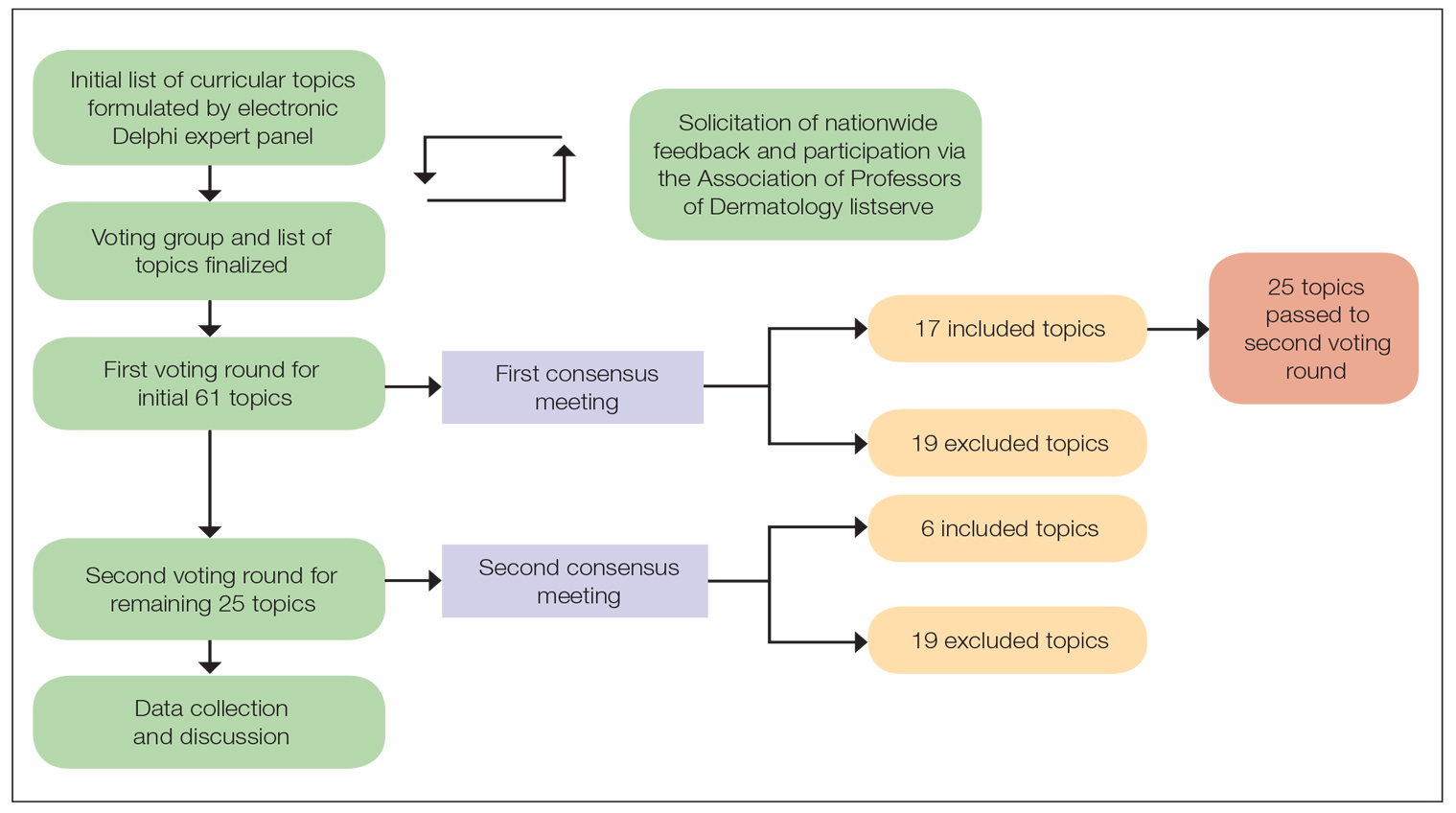

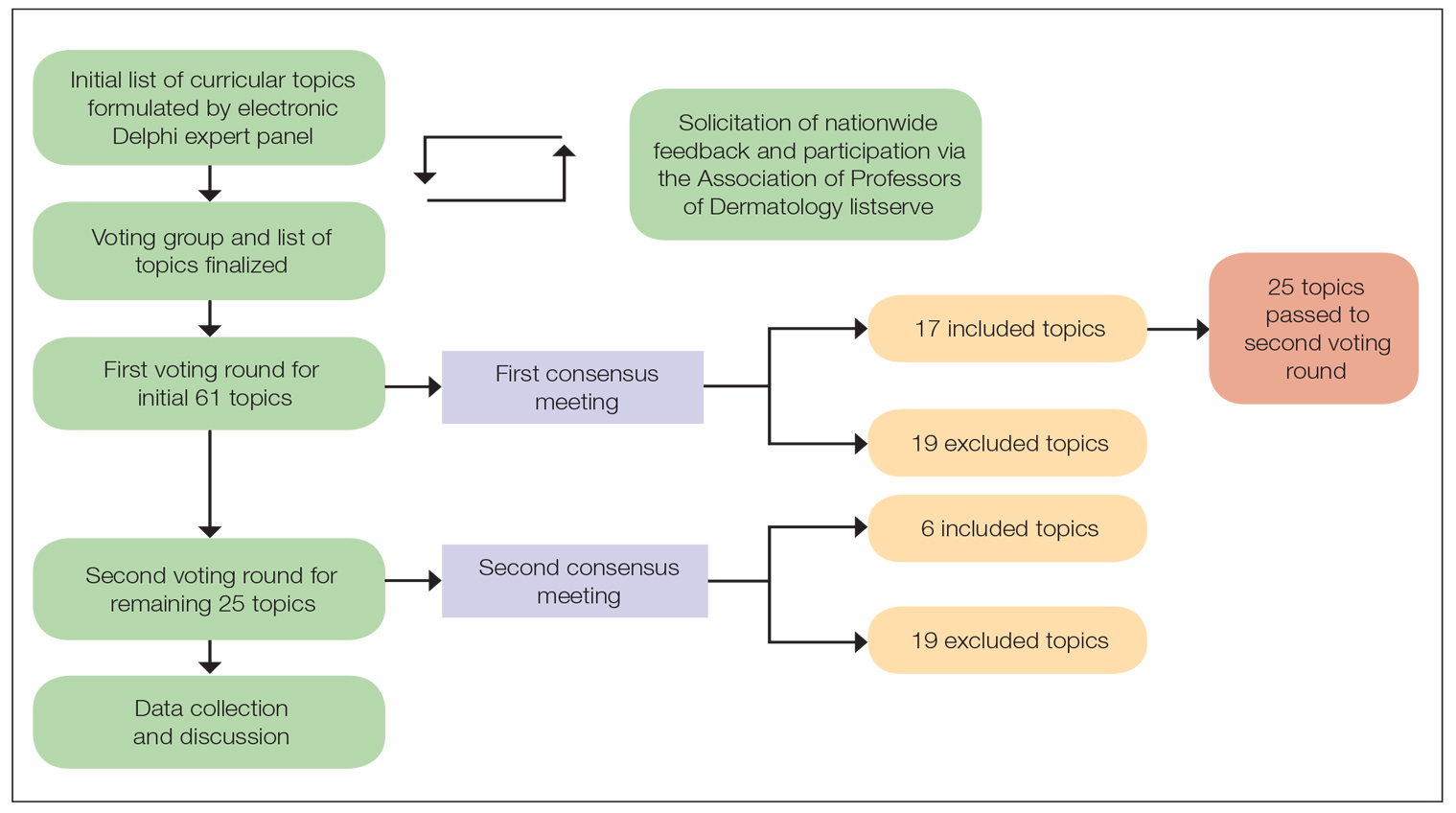

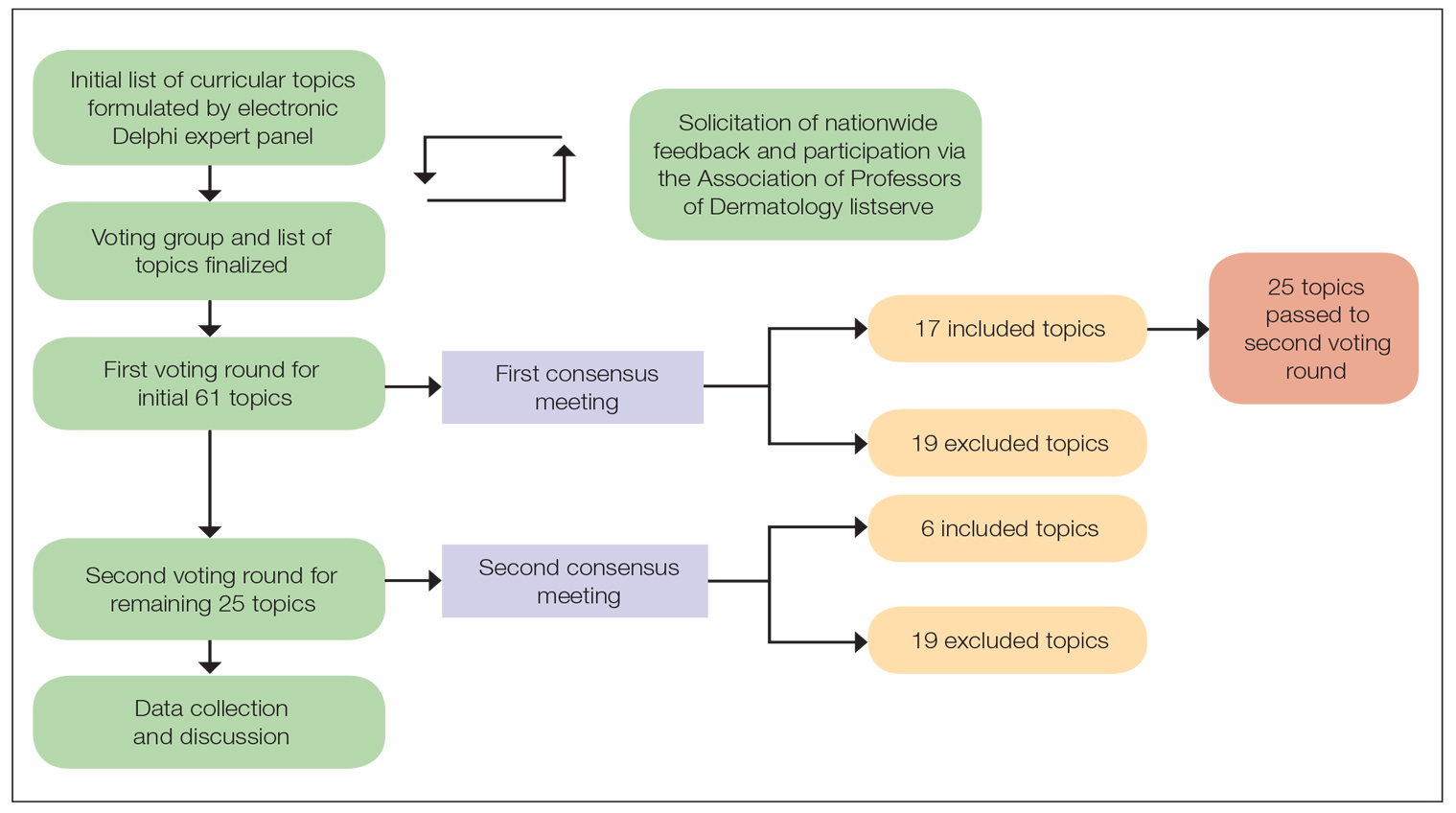

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs seek to improve dermatologic education and clinical care for an increasingly diverse patient population as well as to recruit and sustain a physician workforce that reflects the diversity of the patients they serve.1,2 In dermatology, only 4.2% and 3.0% of practicing dermatologists self-identify as being of Hispanic and African American ethnicity, respectively, compared with 18.5% and 13.4% of the general population, respectively.3 Creating an educational system that works to meet the goals of DEI is essential to improve health outcomes and address disparities. The lack of robust DEI-related curricula during residency training may limit the ability of practicing dermatologists to provide comprehensive and culturally sensitive care. It has been shown that racial concordance between patients and physicians has a positive impact on patient satisfaction by fostering a trusting patient-physician relationship.4

It is the responsibility of all dermatologists to create an environment where patients from any background can feel comfortable, which can be cultivated by establishing patient-centered communication and cultural humility.5 These skills can be strengthened via the implementation of DEI-related curricula during residency training. Augmenting exposure of these topics during training can optimize the delivery of dermatologic care by providing residents with the tools and confidence needed to care for patients of culturally diverse backgrounds. Enhancing DEI education is crucial to not only improve the recognition and treatment of dermatologic conditions in all skin and hair types but also to minimize misconceptions, stigma, health disparities, and discrimination faced by historically marginalized communities. Creating a culture of inclusion is of paramount importance to build successful relationships with patients and colleagues of culturally diverse backgrounds.6

There are multiple efforts underway to increase DEI education across the field of dermatology, including the development of DEI task forces in professional organizations and societies that serve to expand DEI-related research, mentorship, and education. The American Academy of Dermatology has been leading efforts to create a curriculum focused on skin of color, particularly addressing inadequate educational training on how dermatologic conditions manifest in this population.7 The Skin of Color Society has similar efforts underway and is developing a speakers bureau to give leading experts a platform to lecture dermatology trainees as well as patient and community audiences on various topics in skin of color.8 These are just 2 of many professional dermatology organizations that are advocating for expanded education on DEI; however, consistently integrating DEI-related topics into dermatology residency training curricula remains a gap in pedagogy. To identify the DEI-related topics of greatest relevance to the dermatology resident curricula, we implemented a modified electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) consensus process to provide standardized recommendations.

Methods

A 2-round modified e-Delphi method was utilized (Figure). An initial list of potential curricular topics was formulated by an expert panel consisting of 5 dermatologists from the Association of Professors of Dermatology DEI subcommittee and the American Academy of Dermatology Diversity Task Force (A.M.A., S.B., R.V., S.D.W., J.I.S.). Initial topics were selected via several meetings among the panel members to discuss existing DEI concerns and issues that were deemed relevant due to education gaps in residency training. The list of topics was further expanded with recommendations obtained via an email sent to dermatology program directors on the Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve, which solicited voluntary participation of academic dermatologists, including program directors and dermatology residents.

There were 2 voting rounds, with each round consisting of questions scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1=not essential, 2=probably not essential, 3=neutral, 4=probably essential, 5=definitely essential). The inclusion criteria to classify a topic as necessary for integration into the dermatology residency curriculum included 95% (18/19) or more of respondents rating the topic as probably essential or definitely essential; if more than 90% (17/19) of respondents rated the topic as probably essential or definitely essential and less than 10% (2/19) rated it as not essential or probably not essential, the topic was still included as part of the suggested curriculum. Topics that received ratings of probably essential or definitely essential by less than 80% (15/19) of respondents were removed from consideration. The topics that did not meet inclusion or exclusion criteria during the first round of voting were refined by the e-Delphi steering committee (V.S.E-C. and F-A.R.) based on open-ended feedback from the voting group provided at the end of the survey and subsequently passed to the second round of voting.

Results

Participants—A total of 19 respondents participated in both voting rounds, the majority (80% [15/19]) of whom were program directors or dermatologists affiliated with academia or development of DEI education; the remaining 20% [4/19]) were dermatology residents.

Open-Ended Feedback—Voting group members were able to provide open-ended feedback for each of the sets of topics after the survey, which the steering committee utilized to modify the topics as needed for the final voting round. For example, “structural racism/discrimination” was originally mentioned as a topic, but several participants suggested including specific types of racism; therefore, the wording was changed to “racism: types, definitions” to encompass broader definitions and types of racism.

Survey Results—Two genres of topics were surveyed in each voting round: clinical and nonclinical. Participants voted on a total of 61 topics, with 23 ultimately selected in the final list of consensus curricular topics. Of those, 9 were clinical and 14 nonclinical. All topics deemed necessary for inclusion in residency curricula are presented in eTables 1 and 2.

During the first round of voting, the e-Delphi panel reached a consensus to include the following 17 topics as essential to dermatology residency training (along with the percentage of voters who classified them as probably essential or definitely essential): how to mitigate bias in clinical and workplace settings (100% [40/40]); social determinants of health-related disparities in dermatology (100% [40/40]); hairstyling practices across different hair textures (100% [40/40]); definitions and examples of microaggressions (97.50% [39/40]); definition, background, and types of bias (97.50% [39/40]); manifestations of bias in the clinical setting (97.44% [38/39]); racial and ethnic disparities in dermatology (97.44% [38/39]); keloids (97.37% [37/38]); differences in dermoscopic presentations in skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); skin cancer in patients with skin of color (97.30% [36/37]); disparities due to bias (95.00% [38/40]); how to apply cultural humility and safety to patients of different cultural backgrounds (94.87% [37/40]); best practices in providing care to patients with limited English proficiency (94.87% [37/40]); hair loss in patients with textured hair (94.74% [36/38]); pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae (94.60% [35/37]); disparities regarding people experiencing homelessness (92.31% [36/39]); and definitions and types of racism and other forms of discrimination (92.31% [36/39]). eTable 1 provides a list of suggested resources to incorporate these topics into the educational components of residency curricula. The resources provided were not part of the voting process, and they were not considered in the consensus analysis; they are included here as suggested educational catalysts.

During the second round of voting, 25 topics were evaluated. Of those, the following 6 topics were proposed to be included as essential in residency training: differences in prevalence and presentation of common inflammatory disorders (100% [29/29]); manifestations of bias in the learning environment (96.55%); antiracist action and how to decrease the effects of structural racism in clinical and educational settings (96.55% [28/29]); diversity of images in dermatology education (96.55% [28/29]); pigmentary disorders and their psychological effects (96.55% [28/29]); and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) dermatologic health care (96.55% [28/29]). eTable 2 includes these topics as well as suggested resources to help incorporate them into training.

Comment

This study utilized a modified e-Delphi technique to identify relevant clinical and nonclinical DEI topics that should be incorporated into dermatology residency curricula. The panel members reached a consensus for 9 clinical DEI-related topics. The respondents agreed that the topics related to skin and hair conditions in patients with skin of color as well as textured hair were crucial to residency education. Skin cancer, hair loss, pseudofolliculitis barbae, acne keloidalis nuchae, keloids, pigmentary disorders, and their varying presentations in patients with skin of color were among the recommended topics. The panel also recommended educating residents on the variable visual presentations of inflammatory conditions in skin of color. Addressing the needs of diverse patients—for example, those belonging to the LGBTQ community—also was deemed important for inclusion.

The remaining 14 chosen topics were nonclinical items addressing concepts such as bias and health care disparities as well as cultural humility and safety.9 Cultural humility and safety focus on developing cultural awareness by creating a safe setting for patients rather than encouraging power relationships between them and their physicians. Various topics related to racism also were recommended to be included in residency curricula, including education on implementation of antiracist action in the workplace.

Many of the nonclinical topics are intertwined; for instance, learning about health care disparities in patients with limited English proficiency allows for improved best practices in delivering care to patients from this population. The first step in overcoming bias and subsequent disparities is acknowledging how the perpetuation of bias leads to disparities after being taught tools to recognize it.

Our group’s guidance on DEI topics should help dermatology residency program leaders as they design and refine program curricula. There are multiple avenues for incorporating education on these topics, including lectures, interactive workshops, role-playing sessions, book or journal clubs, and discussion circles. Many of these topics/programs may already be included in programs’ didactic curricula, which would minimize the burden of finding space to educate on these topics. Institutional cultural change is key to ensuring truly diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces. Educating tomorrow’s dermatologists on these topics is a first step toward achieving that cultural change.

Limitations—A limitation of this e-Delphi survey is that only a selection of experts in this field was included. Additionally, we were concerned that the Likert scale format and the bar we set for inclusion and exclusion may have failed to adequately capture participants’ nuanced opinions. As such, participants were able to provide open-ended feedback, and suggestions for alternate wording or other changes were considered by the steering committee. Finally, inclusion recommendations identified in this survey were developed specifically for US dermatology residents.

Conclusion

In this e-Delphi consensus assessment of DEI-related topics, we recommend the inclusion of 23 topics into dermatology residency program curricula to improve medical training and the patient-physician relationship as well as to create better health outcomes. We also provide specific sample resource recommendations in eTables 1 and 2 to facilitate inclusion of these topics into residency curricula across the country.

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

- US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. News release. US Census Bureau. December 12, 2012. Accessed August 14, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12243.html#:~:text=12%2C%202012,U.S.%20Census%20Bureau%20Projections%20Show%20a%20Slower%20Growing%2C%20Older%2C%20More,by%20the%20U.S.%20Census%20Bureau

- Lopez S, Lourido JO, Lim HW, et al. The call to action to increase racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a retrospective, cross-sectional study to monitor progress. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;86:E121-E123. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.011

- El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in dermatology: a reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15:27-29.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Street RL Jr, O’Malley KJ, Cooper LA, et al. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:198-205. doi:10.1370/afm.821

- Dadrass F, Bowers S, Shinkai K, et al. Diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology residency. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:257-263. doi:10.1016/j.det.2022.10.006

- Diversity and the Academy. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/member/career/diversity

- SOCS speaks. Skin of Color Society website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/news-media/socs-speaks

- Solchanyk D, Ekeh O, Saffran L, et al. Integrating cultural humility into the medical education curriculum: strategies for educators. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33:554-560. doi:10.1080/10401334.2021.1877711

PRACTICE POINTS

- Advancing curricula related to diversity, equity, and inclusion in dermatology training can improve health outcomes, address health care workforce disparities, and enhance clinical care for diverse patient populations.

- Education on patient-centered communication, cultural humility, and the impact of social determinants of health results in dermatology residents who are better equipped with the necessary tools to effectively care for patients from diverse backgrounds.

Comment on “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type”

To the Editor:

It is with great interest that I read the article by Ware et al,1 “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type.” Within my own department, the issue of the appropriateness of using Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) as a surrogate to describe skin color has been raised with mixed responses.

As in many dermatology residency programs across the country, first-year dermatology residents are asked to describe the morphology of a lesion/eruption seen on a patient during Grand Rounds. Preceding the morphologic description, many providers describe the appearance of the patient including their skin color, as constitutive skin color can impact understanding of the morphologic descriptions, favor different diagnoses based on disease epidemiology, and guide subsequent treatment recommendations.2,3 During one of my first Grand Rounds as an early dermatology resident, a patient was described as a “well-appearing brown boy,” which led to a lively discussion regarding the terms that should be used to describe skin color, with some in the audience preferring FST, others including myself preferring degree of pigmentation (eg, light, moderate, dark), and lastly others preferring an inferred ethnicity based on the patient’s appearance. One audience member commented, “I am brown, therefore I think it is fine to say ‘brown boy,’” which adds to findings from Ware et al1 that there may be differences in what providers prefer to utilize to describe a patient’s skin color based on their own constitutive skin color.

I inquired with 2 other first-year dermatology residents with skin of color at other programs. When asked what terminology they use to describe a patient for Grand Rounds or in clinic, one resident replied, “It’s stylistic but if it’s your one liner [for assessment and plan] use their ethnicity [whereas] if it’s [for] a physical exam use their Fitzpatrick skin type.” The other resident replied, “I use Fitzpatrick skin type even though it’s technically subjective and therefore not appropriate for use within objective data, such as the physical exam, however it’s a language that most colleagues understand as a substitute for skin color.” I also raised the same question to an attending dermatologist at a primarily skin-of-color community hospital. She replied, “I think when unsure about ethnicity, Fitzpatrick type is an appropriate way to describe someone. It’s not really correct to say [a patient’s ethnicity] when you don’t know for sure.”

Unfortunately, as Ware and colleagues1 indicated, there is no consensus by which to objectively classify nonwhite skin color. Within the dermatology literature, it has been proposed that race should not be used to express skin color, and this article proposes that FST is an inappropriate surrogate for race/ethnicity.4 Although I agree that appropriate use of FST should be emphasized in training, is there a vocabulary that Ware et al1 recommend we use instead? Does the Skin of Color Society have suggestions on preferred language among its members? Finally, what efforts are being made to develop “culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color,” as the authors stated, within our own Skin of Color Society, or to whom does this responsibility ultimately fall?

References

1. Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

2. Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

3. Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

4. Bigby M, Thaler D. Describing patients’ “race” in clinical presentations should be abandoned. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1074-1076.

Author’s Response

My colleagues and I thank Dr. Pimentel for his insights regarding the article, “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type.”1 The conundrum on how to appropriately categorize skin color for descriptive and epidemiologic purposes continues to remain unsolved today. However, attempts have been made in the past. For example, in September 2006, Dr. Susan C. Taylor (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), formed and chaired a workshop session titled “A New Classification System for All Skin Types.” Dermatology leaders with skin of color expertise were invited from around the world for a weekend in New York, New York, to brainstorm a new skin color classification system. This endeavor did not produce any successful alternatives, but it has remained a pertinent topic of discussion in academic dermatology, including the Skin of Color Society, since then.

When unsure about ethnicity, my colleagues and I continue to advocate that the Fitzpatrick scale is not an appropriate substitute to describe skin color. This usage of Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) perpetuates the idea that the Fitzpatrick scale is a suitable proxy to describe ethnicity or race, which it is not. It is important to remember that race is a social classification construct, not a biological one.2 The topic of race in contemporary culture undoubtedly invokes strong emotional connotations. The language around race is constantly evolving. I would argue that fear and discomfort of using incorrect racial language promotes the inappropriate use of FST, as the FST may be perceived as a more scientific and pseudoapplicable form of classification. To gain knowledge about a patient’s ethnicity/race to assess epidemiologic ethnic trends, we recommend asking the patient in an intake form or during consultation to self-identify his/her ethnicity or race,3 which takes the guesswork out for providers. However, caution must be exercised to avoid using race and ethnicity to later describe skin color.

Until a more culturally and medically relevant method of skin color classification is created, my colleagues and I recommend using basic color adjectives such as brown, black, pink, tan, or white supplemented with light, medium, or dark predescriptors. For example, “A 35-year-old self-identified African American woman with a dark brown skin hue presents with a 2-week flare of itchy, dark purple plaques with white scale on the scalp and extensor surfaces of the knees and elbows.” These basic descriptions for constitutive skin color conjure ample visual information for the listener/reader to understand morphologic descriptions, presentation of erythema, changes in pigmentation, and more. For a more specific skin color classification, we recommend developing a user-friendly Pantone-like color system to classify constitutive skin color.4

Jessica E. Dawson, MD

From the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Jessica E. Dawson, MD, University of Washington School of Medicine, 1959 NE Pacific St, Seattle, WA 98195 ([email protected]).

References

1. Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

2. Ifekwunigwe JO, Wagner JK, Yu JH, et al. A qualitative analysis of how anthropologists interpret the race construct. Am Anthropol. 2017;119:422-434.

3. Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Obtaining data on patient race, ethnicity, and primary language in health care organizations: current challenges and proposed solutions. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1501-1518.

4. What is the Pantone color system? Pantone website. https://www.pantone.com/color-systems/pantone-color-systems-explained. Accesed May 13, 2020.

To the Editor:

It is with great interest that I read the article by Ware et al,1 “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type.” Within my own department, the issue of the appropriateness of using Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) as a surrogate to describe skin color has been raised with mixed responses.

As in many dermatology residency programs across the country, first-year dermatology residents are asked to describe the morphology of a lesion/eruption seen on a patient during Grand Rounds. Preceding the morphologic description, many providers describe the appearance of the patient including their skin color, as constitutive skin color can impact understanding of the morphologic descriptions, favor different diagnoses based on disease epidemiology, and guide subsequent treatment recommendations.2,3 During one of my first Grand Rounds as an early dermatology resident, a patient was described as a “well-appearing brown boy,” which led to a lively discussion regarding the terms that should be used to describe skin color, with some in the audience preferring FST, others including myself preferring degree of pigmentation (eg, light, moderate, dark), and lastly others preferring an inferred ethnicity based on the patient’s appearance. One audience member commented, “I am brown, therefore I think it is fine to say ‘brown boy,’” which adds to findings from Ware et al1 that there may be differences in what providers prefer to utilize to describe a patient’s skin color based on their own constitutive skin color.

I inquired with 2 other first-year dermatology residents with skin of color at other programs. When asked what terminology they use to describe a patient for Grand Rounds or in clinic, one resident replied, “It’s stylistic but if it’s your one liner [for assessment and plan] use their ethnicity [whereas] if it’s [for] a physical exam use their Fitzpatrick skin type.” The other resident replied, “I use Fitzpatrick skin type even though it’s technically subjective and therefore not appropriate for use within objective data, such as the physical exam, however it’s a language that most colleagues understand as a substitute for skin color.” I also raised the same question to an attending dermatologist at a primarily skin-of-color community hospital. She replied, “I think when unsure about ethnicity, Fitzpatrick type is an appropriate way to describe someone. It’s not really correct to say [a patient’s ethnicity] when you don’t know for sure.”

Unfortunately, as Ware and colleagues1 indicated, there is no consensus by which to objectively classify nonwhite skin color. Within the dermatology literature, it has been proposed that race should not be used to express skin color, and this article proposes that FST is an inappropriate surrogate for race/ethnicity.4 Although I agree that appropriate use of FST should be emphasized in training, is there a vocabulary that Ware et al1 recommend we use instead? Does the Skin of Color Society have suggestions on preferred language among its members? Finally, what efforts are being made to develop “culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color,” as the authors stated, within our own Skin of Color Society, or to whom does this responsibility ultimately fall?

References

1. Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

2. Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

3. Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

4. Bigby M, Thaler D. Describing patients’ “race” in clinical presentations should be abandoned. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1074-1076.

Author’s Response

My colleagues and I thank Dr. Pimentel for his insights regarding the article, “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type.”1 The conundrum on how to appropriately categorize skin color for descriptive and epidemiologic purposes continues to remain unsolved today. However, attempts have been made in the past. For example, in September 2006, Dr. Susan C. Taylor (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), formed and chaired a workshop session titled “A New Classification System for All Skin Types.” Dermatology leaders with skin of color expertise were invited from around the world for a weekend in New York, New York, to brainstorm a new skin color classification system. This endeavor did not produce any successful alternatives, but it has remained a pertinent topic of discussion in academic dermatology, including the Skin of Color Society, since then.

When unsure about ethnicity, my colleagues and I continue to advocate that the Fitzpatrick scale is not an appropriate substitute to describe skin color. This usage of Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) perpetuates the idea that the Fitzpatrick scale is a suitable proxy to describe ethnicity or race, which it is not. It is important to remember that race is a social classification construct, not a biological one.2 The topic of race in contemporary culture undoubtedly invokes strong emotional connotations. The language around race is constantly evolving. I would argue that fear and discomfort of using incorrect racial language promotes the inappropriate use of FST, as the FST may be perceived as a more scientific and pseudoapplicable form of classification. To gain knowledge about a patient’s ethnicity/race to assess epidemiologic ethnic trends, we recommend asking the patient in an intake form or during consultation to self-identify his/her ethnicity or race,3 which takes the guesswork out for providers. However, caution must be exercised to avoid using race and ethnicity to later describe skin color.

Until a more culturally and medically relevant method of skin color classification is created, my colleagues and I recommend using basic color adjectives such as brown, black, pink, tan, or white supplemented with light, medium, or dark predescriptors. For example, “A 35-year-old self-identified African American woman with a dark brown skin hue presents with a 2-week flare of itchy, dark purple plaques with white scale on the scalp and extensor surfaces of the knees and elbows.” These basic descriptions for constitutive skin color conjure ample visual information for the listener/reader to understand morphologic descriptions, presentation of erythema, changes in pigmentation, and more. For a more specific skin color classification, we recommend developing a user-friendly Pantone-like color system to classify constitutive skin color.4

Jessica E. Dawson, MD

From the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Jessica E. Dawson, MD, University of Washington School of Medicine, 1959 NE Pacific St, Seattle, WA 98195 ([email protected]).

References

1. Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

2. Ifekwunigwe JO, Wagner JK, Yu JH, et al. A qualitative analysis of how anthropologists interpret the race construct. Am Anthropol. 2017;119:422-434.

3. Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Obtaining data on patient race, ethnicity, and primary language in health care organizations: current challenges and proposed solutions. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1501-1518.

4. What is the Pantone color system? Pantone website. https://www.pantone.com/color-systems/pantone-color-systems-explained. Accesed May 13, 2020.

To the Editor:

It is with great interest that I read the article by Ware et al,1 “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type.” Within my own department, the issue of the appropriateness of using Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) as a surrogate to describe skin color has been raised with mixed responses.

As in many dermatology residency programs across the country, first-year dermatology residents are asked to describe the morphology of a lesion/eruption seen on a patient during Grand Rounds. Preceding the morphologic description, many providers describe the appearance of the patient including their skin color, as constitutive skin color can impact understanding of the morphologic descriptions, favor different diagnoses based on disease epidemiology, and guide subsequent treatment recommendations.2,3 During one of my first Grand Rounds as an early dermatology resident, a patient was described as a “well-appearing brown boy,” which led to a lively discussion regarding the terms that should be used to describe skin color, with some in the audience preferring FST, others including myself preferring degree of pigmentation (eg, light, moderate, dark), and lastly others preferring an inferred ethnicity based on the patient’s appearance. One audience member commented, “I am brown, therefore I think it is fine to say ‘brown boy,’” which adds to findings from Ware et al1 that there may be differences in what providers prefer to utilize to describe a patient’s skin color based on their own constitutive skin color.

I inquired with 2 other first-year dermatology residents with skin of color at other programs. When asked what terminology they use to describe a patient for Grand Rounds or in clinic, one resident replied, “It’s stylistic but if it’s your one liner [for assessment and plan] use their ethnicity [whereas] if it’s [for] a physical exam use their Fitzpatrick skin type.” The other resident replied, “I use Fitzpatrick skin type even though it’s technically subjective and therefore not appropriate for use within objective data, such as the physical exam, however it’s a language that most colleagues understand as a substitute for skin color.” I also raised the same question to an attending dermatologist at a primarily skin-of-color community hospital. She replied, “I think when unsure about ethnicity, Fitzpatrick type is an appropriate way to describe someone. It’s not really correct to say [a patient’s ethnicity] when you don’t know for sure.”

Unfortunately, as Ware and colleagues1 indicated, there is no consensus by which to objectively classify nonwhite skin color. Within the dermatology literature, it has been proposed that race should not be used to express skin color, and this article proposes that FST is an inappropriate surrogate for race/ethnicity.4 Although I agree that appropriate use of FST should be emphasized in training, is there a vocabulary that Ware et al1 recommend we use instead? Does the Skin of Color Society have suggestions on preferred language among its members? Finally, what efforts are being made to develop “culturally appropriate and clinically relevant methods for describing skin of color,” as the authors stated, within our own Skin of Color Society, or to whom does this responsibility ultimately fall?

References

1. Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

2. Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96.

3. Kelly AP, Taylor SC, Lim HW, et al. Taylor and Kelly’s Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

4. Bigby M, Thaler D. Describing patients’ “race” in clinical presentations should be abandoned. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1074-1076.

Author’s Response

My colleagues and I thank Dr. Pimentel for his insights regarding the article, “Racial Limitations of Fitzpatrick Skin Type.”1 The conundrum on how to appropriately categorize skin color for descriptive and epidemiologic purposes continues to remain unsolved today. However, attempts have been made in the past. For example, in September 2006, Dr. Susan C. Taylor (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), formed and chaired a workshop session titled “A New Classification System for All Skin Types.” Dermatology leaders with skin of color expertise were invited from around the world for a weekend in New York, New York, to brainstorm a new skin color classification system. This endeavor did not produce any successful alternatives, but it has remained a pertinent topic of discussion in academic dermatology, including the Skin of Color Society, since then.

When unsure about ethnicity, my colleagues and I continue to advocate that the Fitzpatrick scale is not an appropriate substitute to describe skin color. This usage of Fitzpatrick skin type (FST) perpetuates the idea that the Fitzpatrick scale is a suitable proxy to describe ethnicity or race, which it is not. It is important to remember that race is a social classification construct, not a biological one.2 The topic of race in contemporary culture undoubtedly invokes strong emotional connotations. The language around race is constantly evolving. I would argue that fear and discomfort of using incorrect racial language promotes the inappropriate use of FST, as the FST may be perceived as a more scientific and pseudoapplicable form of classification. To gain knowledge about a patient’s ethnicity/race to assess epidemiologic ethnic trends, we recommend asking the patient in an intake form or during consultation to self-identify his/her ethnicity or race,3 which takes the guesswork out for providers. However, caution must be exercised to avoid using race and ethnicity to later describe skin color.

Until a more culturally and medically relevant method of skin color classification is created, my colleagues and I recommend using basic color adjectives such as brown, black, pink, tan, or white supplemented with light, medium, or dark predescriptors. For example, “A 35-year-old self-identified African American woman with a dark brown skin hue presents with a 2-week flare of itchy, dark purple plaques with white scale on the scalp and extensor surfaces of the knees and elbows.” These basic descriptions for constitutive skin color conjure ample visual information for the listener/reader to understand morphologic descriptions, presentation of erythema, changes in pigmentation, and more. For a more specific skin color classification, we recommend developing a user-friendly Pantone-like color system to classify constitutive skin color.4

Jessica E. Dawson, MD

From the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

The author reports no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Jessica E. Dawson, MD, University of Washington School of Medicine, 1959 NE Pacific St, Seattle, WA 98195 ([email protected]).

References

1. Ware OR, Dawson JE, Shinohara MM, et al. Racial limitations of Fitzpatrick skin type. Cutis. 2020;105:77-80.

2. Ifekwunigwe JO, Wagner JK, Yu JH, et al. A qualitative analysis of how anthropologists interpret the race construct. Am Anthropol. 2017;119:422-434.

3. Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW. Obtaining data on patient race, ethnicity, and primary language in health care organizations: current challenges and proposed solutions. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1501-1518.

4. What is the Pantone color system? Pantone website. https://www.pantone.com/color-systems/pantone-color-systems-explained. Accesed May 13, 2020.