User login

Mycobacterium marinum Remains an Unrecognized Cause of Indolent Skin Infections

An environmental pathogen, Mycobacterium marinum can cause cutaneous infection when traumatized skin is exposed to fresh, brackish, or salt water. Fishing, aquarium cleaning, and aquatic recreational activities are risk factors for infection.1,2 Diagnosis often is delayed and is made several weeks or even months after initial symptoms appear.3 Due to the protracted clinical course, patients may not recall the initial exposure, contributing to the delay in diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. It is not uncommon for patients with M marinum infection to be initially treated with antibiotics or antifungal drugs.

We present a review of 5 patients who were diagnosed with M marinum infection at our institution between January 2003 and March 2013.

Methods

This study was conducted at Henry Ford Hospital, a 900-bed tertiary care center in Detroit, Michigan. Patients who had cultures positive for M marinum between January 2003 and March 2013 were identified using the institution’s laboratory database. Medical records were reviewed, and relevant demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical data, including initial clinical presentation, alternative diagnoses, time between initial presentation and definitive diagnosis, and specific treatment, were recorded.

Results

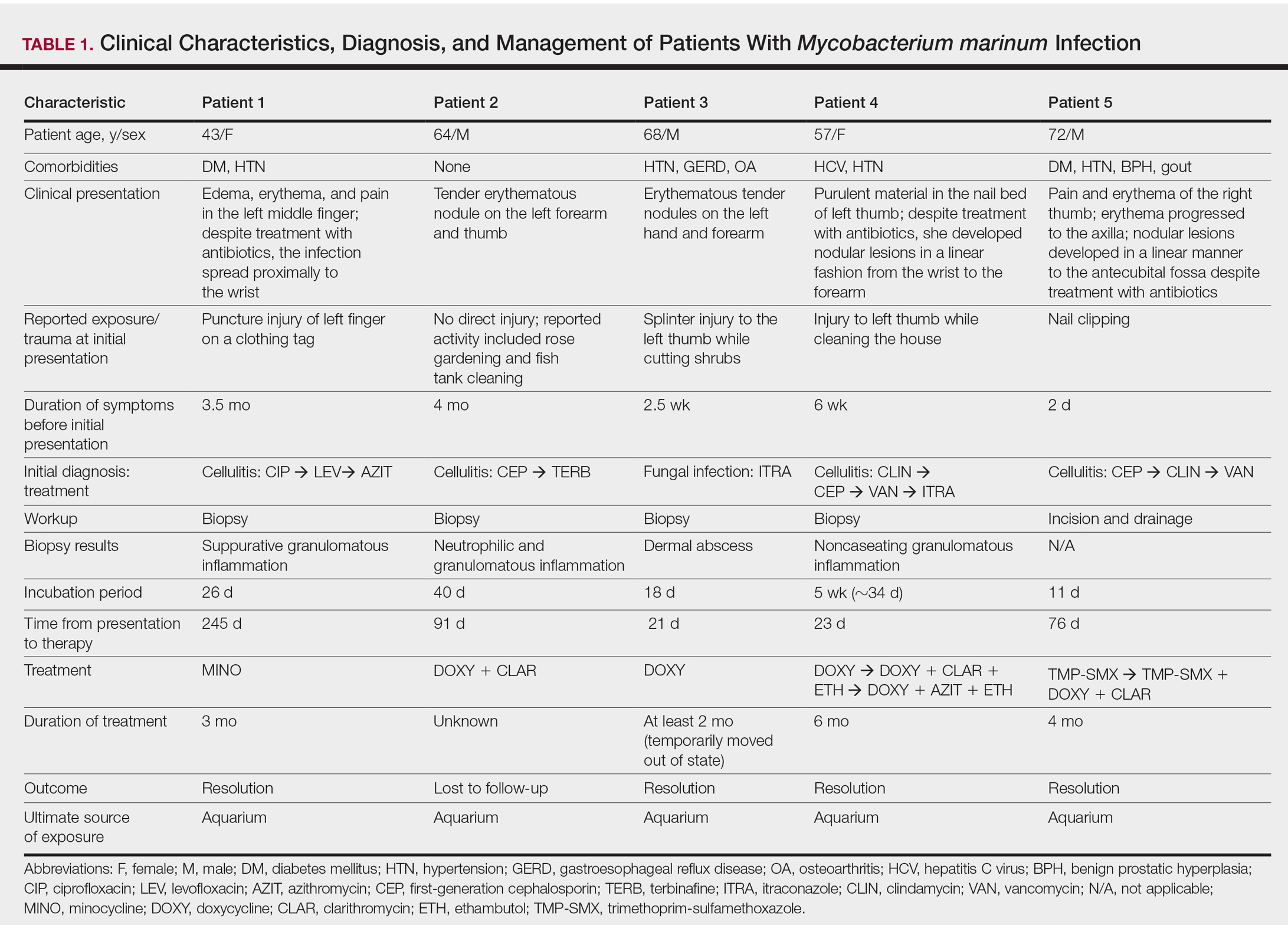

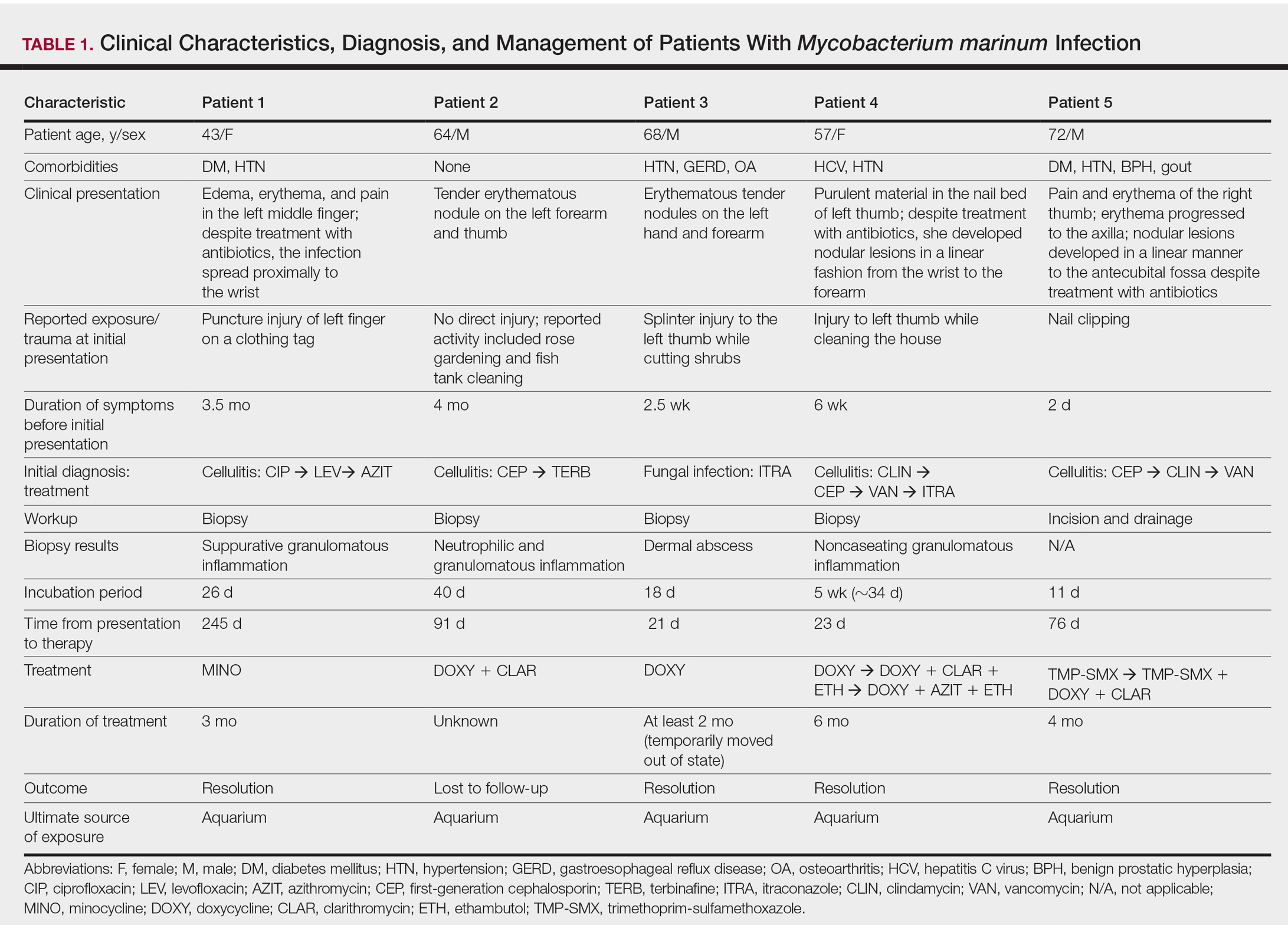

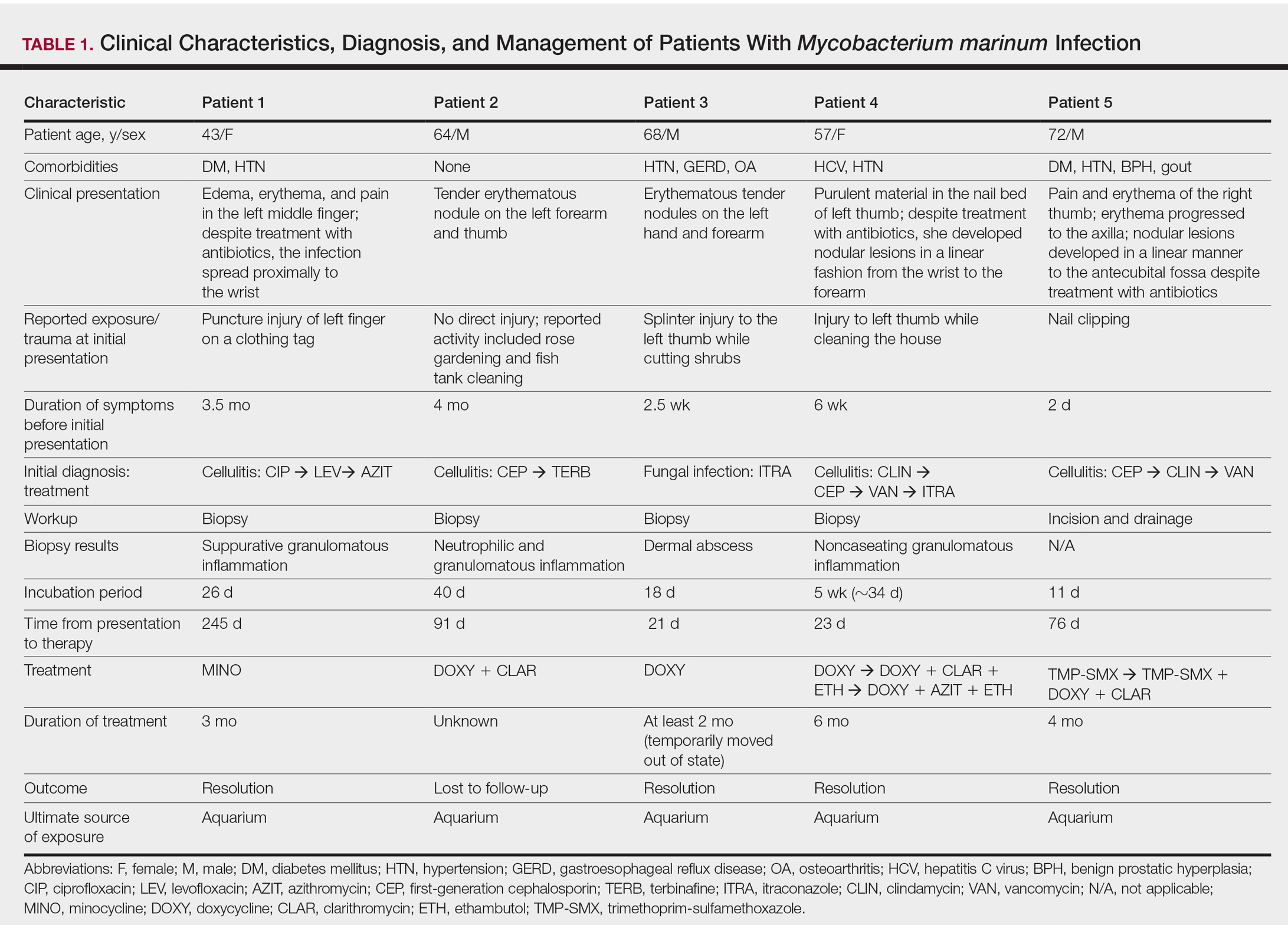

We identified 5 patients who were diagnosed with culture-confirmed M marinum skin infections during the study period: 3 men and 2 women aged 43 to 72 years (Table 1). Two patients had diabetes mellitus and 1 had hepatitis C virus. None had classic immunosuppression. On repeated questioning after the diagnosis was established, all 5 patients reported that they kept a home aquarium, and all recalled mild trauma to the hand prior to the onset of symptoms; however, none of the patients initially linked the minor skin injury to the subsequent infection.

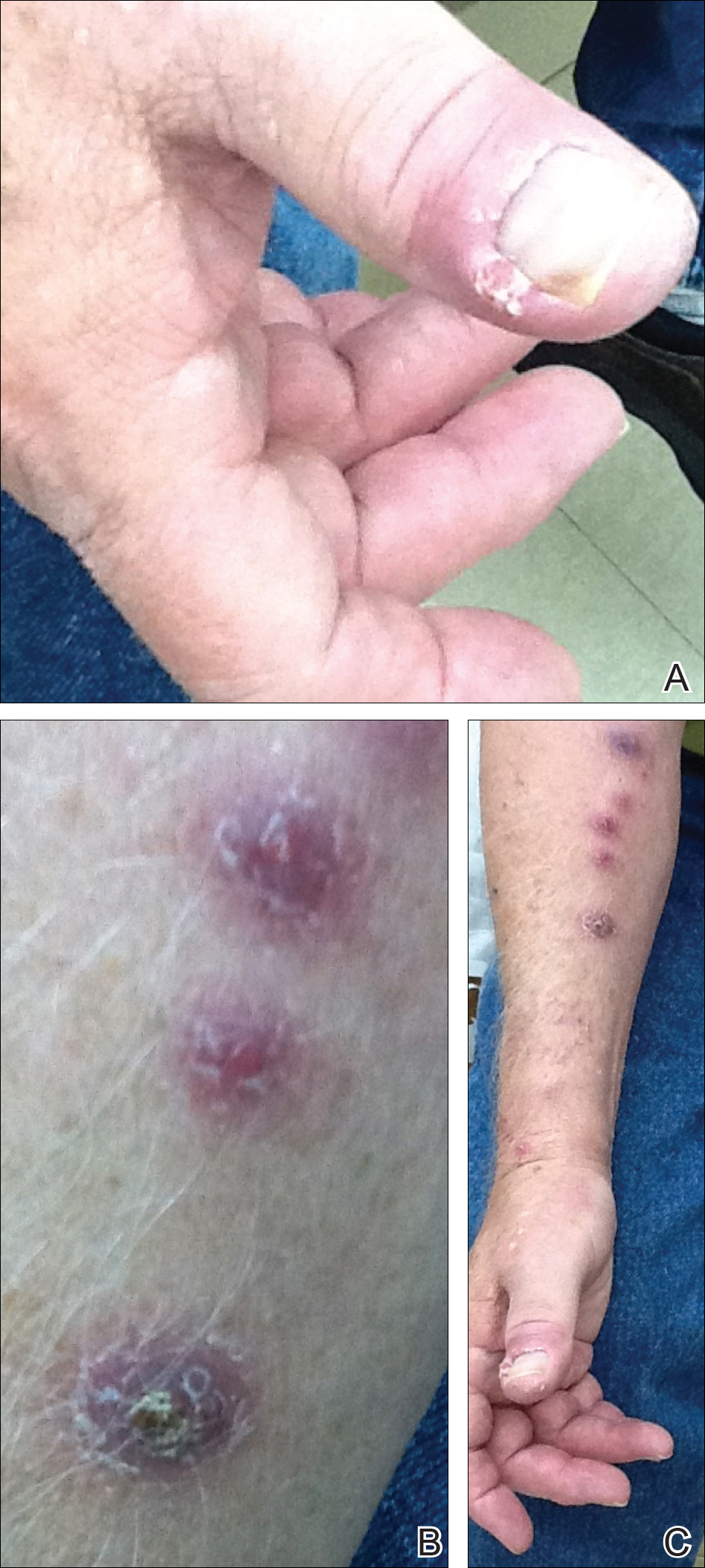

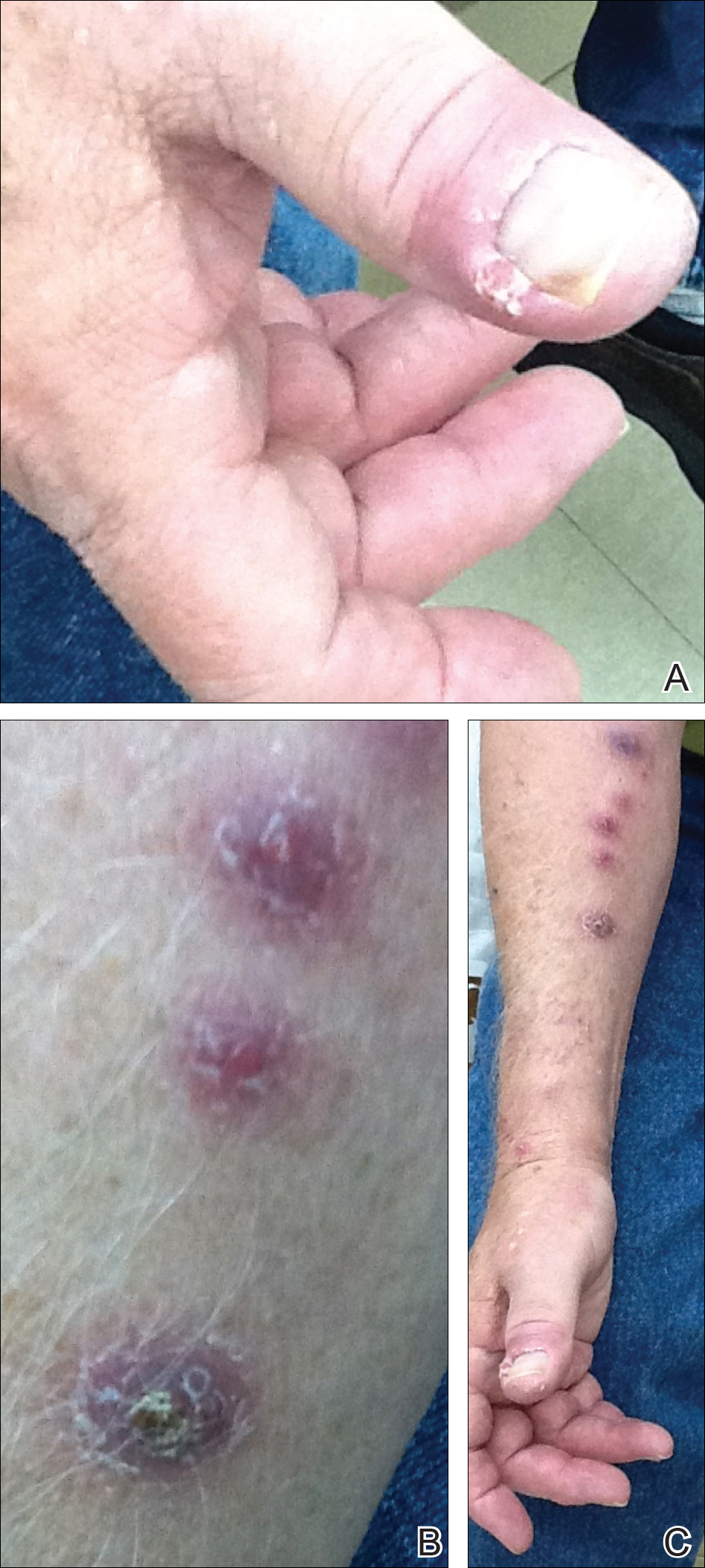

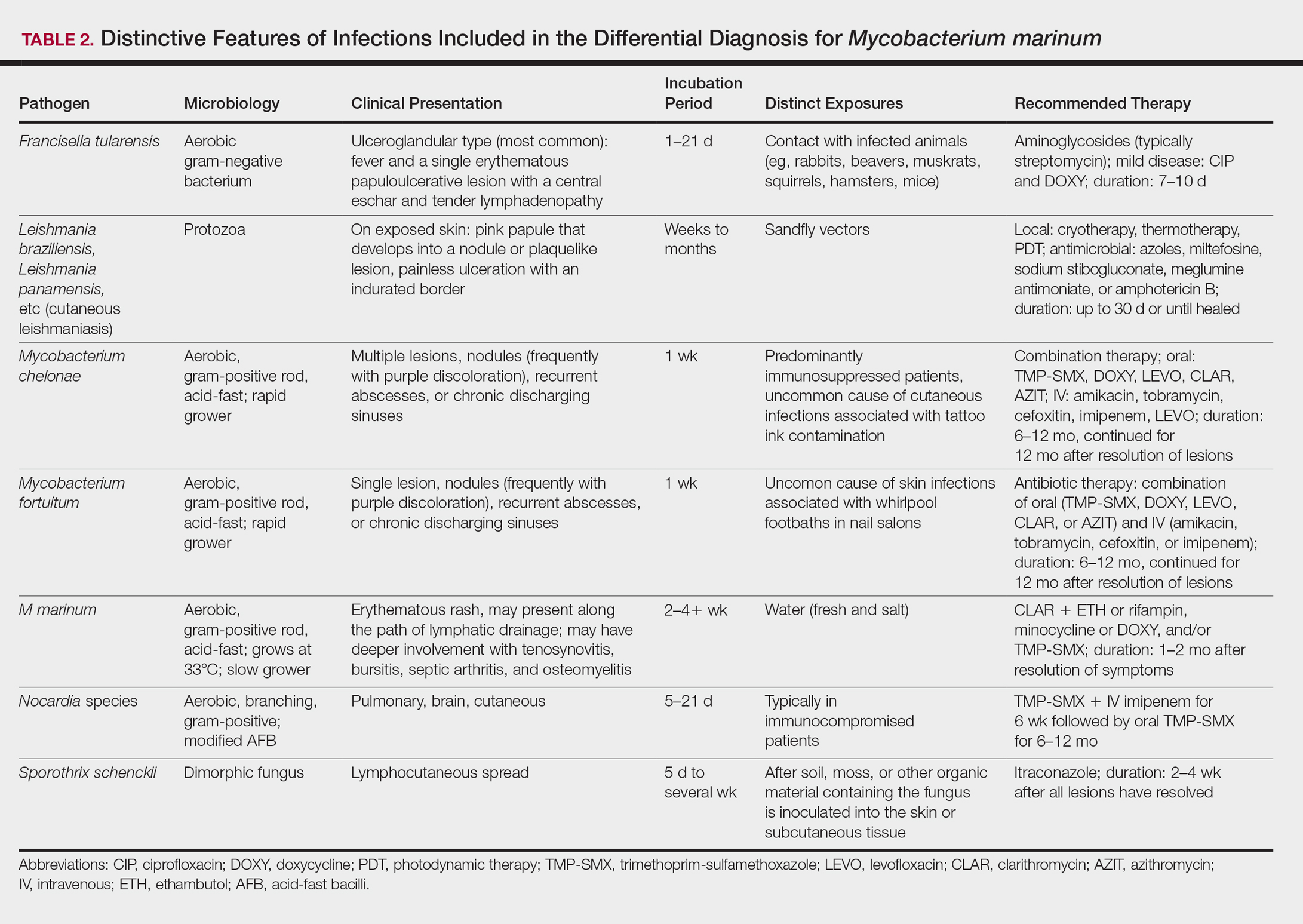

All 5 patients initially presented with erythema and swelling at the site of the injury, which evolved into inflammatory nodules that progressed proximally up to the arm despite empiric treatment with antibiotics active against streptococci and staphylococci (Figures 1 and 2). Three patients also received empiric antifungal therapy due to suspicion of sporotrichosis.

Skin biopsies were performed on 4 patients, and incision and drainage of purulent material was performed on the fifth patient. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation in 3 patients. Stains for acid-fast bacilli were positive in all 5 patients. Definitive diagnosis of the organism was confirmed by growth of M marinum within 11 to 40 days from the tissue in 4 patients and purulent material in the fifth patient. Susceptibility testing was performed on only 1 of the 5 isolates and showed that the organism was susceptible to amikacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, ethambutol, rifampin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The mean time from initial presentation to initiation of appropriate therapy for M marinum infection was 91 days (range, 21–245 days). Several different treatment regimens were used. All patients received either doxycycline or minocycline with or without a macrolide. Two also received other agents (TMP-SMX or ethambutol). Treatment duration varied from 2 to 6 months in 4 patients, and all 4 had complete resolution of the lesions; 1 patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

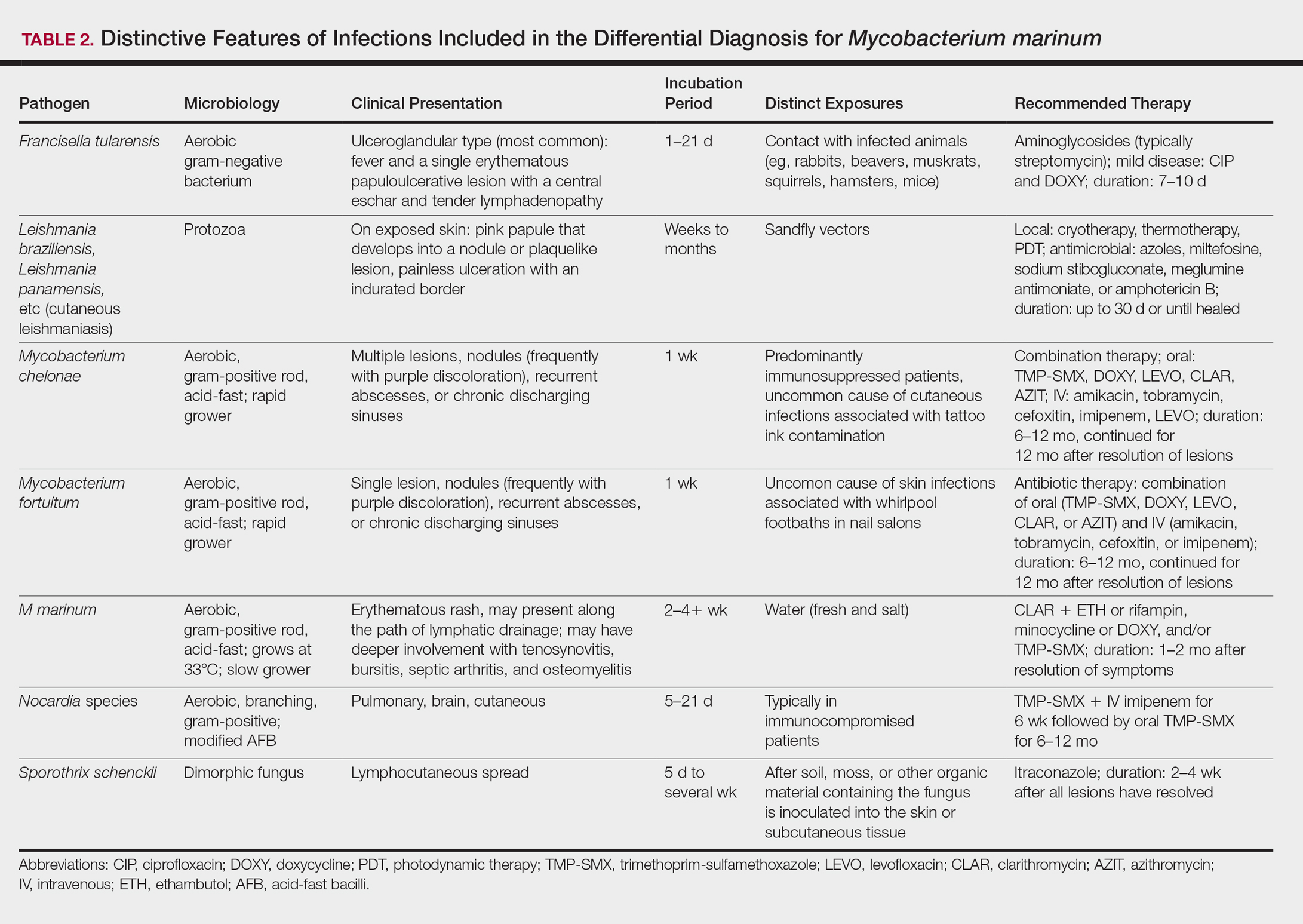

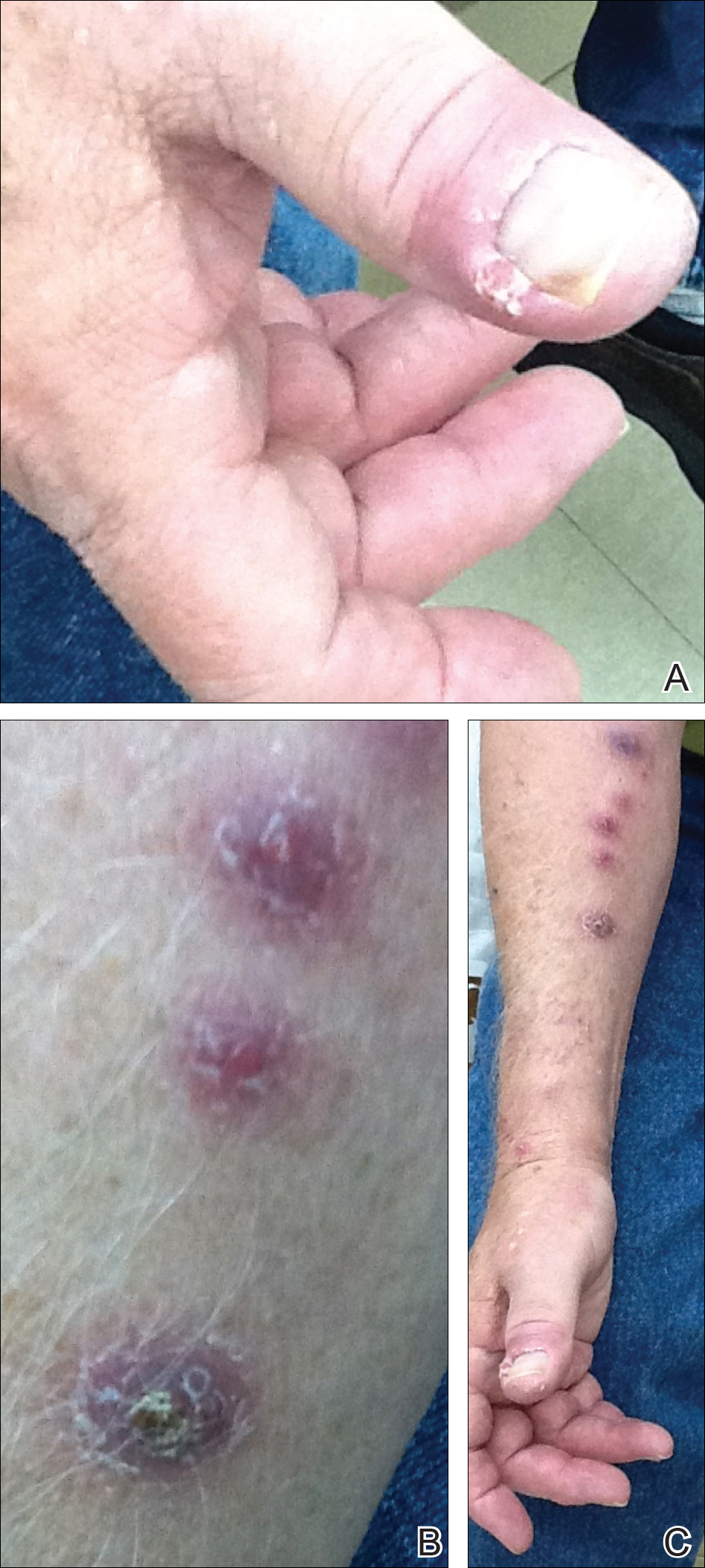

Diagnosing the Infection

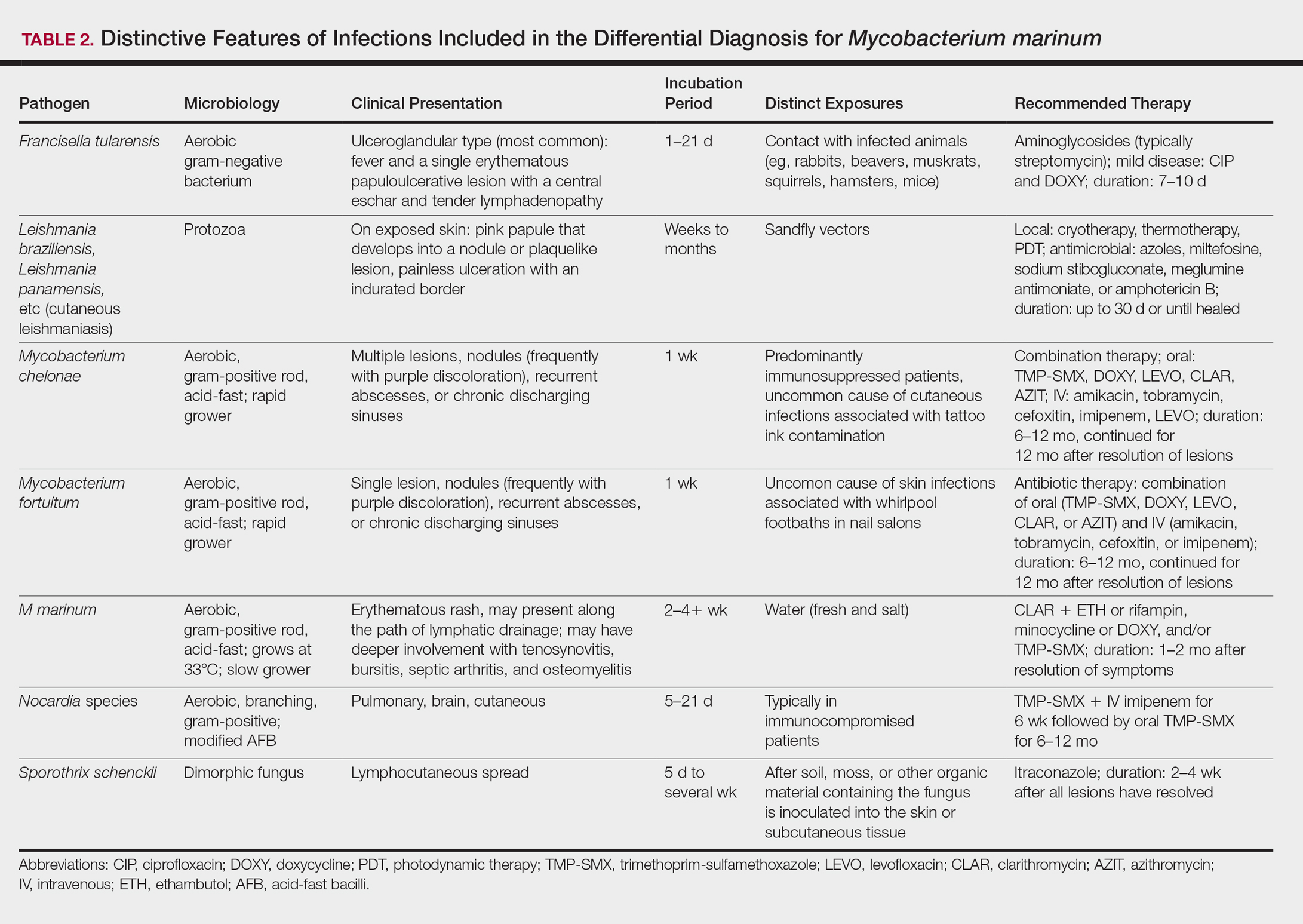

Diagnosis of M marinum infection remains problematic. In the 5 patients included in this study, the time between initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis of M marinum infection was delayed, as has been noted in other reports.4-7 Delays as long as 2 years before the diagnosis is made have been described.7 The clinical presentation of cutaneous infection with M marinum varies, which may delay diagnosis. Nodular lymphangitis is classic, but papules, pustules, ulcers, inflammatory plaques, and single nodules also can occur.1,2 Lymphadenopathy may or may not be present.4,8,9 The differential diagnosis is broad and includes infection by other nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium chelonae; Mycobacterium fortuitum; Nocardia species, especially Nocardia brasiliensis; Francisella tularensis; Sporothrix schenckii; and Leishmania species. It is not surprising that 4 patients in our study were initially treated for a gram-positive bacterial infection and 3 were treated for a fungal infection before the diagnosis of M marinum was made. Distinctive features that may help to differentiate these infections are summarized in Table 2.

We found that the main cause of delayed diagnosis was the failure of physicians to obtain a thorough history regarding patients’ recreational activities and animal exposure. Patients often do not associate a remote aquatic exposure with their symptoms and will not volunteer this information unless directly asked.2,10 It was only after repeated questioning in all of these patients that they recounted prior trauma to the involved hand related to the aquarium.

Biopsy and Culture

Histopathologic examination of material from a biopsied lesion can give an early clue that a mycobacterial infection might be involved. Biopsy can reveal either noncaseating or necrotizing granulomas that have larger numbers of neutrophils in addition to lymphocytes and macrophages. Giant cells often are noted.5,9,11 Organisms can be seen with the use of a tissue acid-fast stain, but species cannot be differentiated by acid-fast staining.12 However, the sensitivity of acid-fast stains on biopsy material is low.3,13,14

Culture of the involved tissue is crucial for establishing the diagnosis of this infection. However, the rate of growth of M marinum is slow. Temperature requirements for incubation and delay in transporting specimens to the laboratory can lead to bacterial overgrowth, resulting in the inability to recover M marinum from the culture.13Mycobacterium marinum grows preferentially between 28°C and 32°C, and growth is limited at temperatures above 33°C.13,15,16 As illustrated in the cases presented, recovery of the organism may not be accomplished from the first culture performed, and additional biopsy material for culture may be needed. Liquid media generally is more sensitive and produces more rapid results than solid media (eg, Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar). However, solid media carry the advantage of allowing observation of morphology and estimation of the number of organisms.12,17

Rapid Detection

Advancements in molecular methods have allowed for more definitive and rapid identification of M marinum, substantially reducing the delay in diagnosis. Commercial molecular assays utilize in-solution hybridization or solid-format reverse-hybridization assays to allow mycobacterial detection as soon as growth appears.18 Use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry can substantially shorten the time to species identification.19,20 Nonculture-based tests that have been developed for the rapid detection of M marinum infection include polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism and polymerase chain reaction amplification of the 16S RNA gene.21 It should be noted, however, that M marinum and Mycobacterium ulcerans have a very homologous 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence, differing by only 1 nucleotide; thus, distinguishing between M marinum and M ulcerans using this method may be challenging.22,23

Management

Treatment depends on the extent of the disease. Generally, localized cutaneous disease can be treated with monotherapy with agents such as doxycycline, clarithromycin, or TMP-SMX. Extensive disease typically requires a combination of 2 antimycobacterial agents, typically clarithromycin-rifampin, clarithromycin-ethambutol, or rifampin-ethambutol.12 Amikacin has been used in combination with other agents such as rifampin and clarithromycin in refractory cases.22,24 The use of ciprofloxacin is not encouraged because some isolates are resistant; however, other fluoroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin, may be options for combination therapy. Isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin are not effective to treat M marinum.

Susceptibility testing of M marinum usually is performed to guide antimicrobial therapy in cases of poor clinical response or intolerance to first-line antimicrobials such as macrolides.25 The likelihood of M marinum developing resistance to the agents used for treatment appears to be low. Unfortunately, in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility tests do not correlate well with treatment efficiency.10

The duration of therapy is not standardized but usually is 5 to 6 months,7,10,26 with therapy often continuing 1 to 2 months after lesions appear to have resolved.12 However, in some cases (usually those who have more extensive disease), therapy has been extended to as long as 1 to 2 years.10 The ideal length of therapy in immunocompromised individuals has not been established27; however, a treatment duration of 6 to 9 months was reported in one study.28 Surgical debridement may be necessary in some patients who have involvement of deep structures of the hand or knee, those with persistent pain, or those who fail to respond to a prolonged period of medical therapy.29 Successful use of less conventional therapeutic approaches, including cryotherapy, radiation therapy, electrodesiccation, photodynamic therapy, curettage, and local hyperthermic therapy has been reported.30-32

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of M marinum infection is difficult. Patients presenting with indolent nodular skin infections affecting the upper extremities should be asked about aquatic exposure. Tissue biopsy for histopathologic examination and culture is essential to establish an early diagnosis and promptly initiate appropriate therapy.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Carol A. Kauffman, MD (Ann Arbor, Michigan), for her thoughtful comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

- Lewis FM, Marsh BJ, von Reyn CF. Fish tank exposure and cutaneous infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: tuberculin skin testing, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:390-397.

- Jernigan JA, Farr BM. Incubation period and sources of exposure for cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:439-443.

- Edelstein H. Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. report of 31 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1359-1364.

- Janik JP, Bang RH, Palmer CH. Case reports: successful treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection with minocycline after complication of disease by delayed diagnosis and systemic steroids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:621-624.

- Jolly HW Jr, Seabury JH. Infections with Myocbacterium marinum. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:32-36.

- Sette CS, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection: a case report. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:7.

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662.

- Eberst E, Dereure O, Guillot B, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic pattern of Mycobacterium marinum infection: a retrospective series of 35 cases from southern France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E15-E16.

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma. a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162.

- Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, et al. Sixty-three cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: clinical features, treatment, and antibiotic susceptibility of causative isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1746-1752.

- Feng Y, Xu H, Wang H, et al. Outbreak of a cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection in Jiangsu Haian, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:267-272.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:343-347.

- Wu TS, Chiu CH, Yang CH, et al. Fish tank granuloma caused by Mycobacterium marinum. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41296.

- Ho WL, Chuang WY, Kuo AJ, et al. Nasal fish tank granuloma: an uncommon cause for epistaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:195-196.

- Dobos KM, Quinn FD, Ashford DA, et al. Emergence of a unique group of necrotizing mycobacterial diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:367-378.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109.

- Piersimoni C, Scarparo C. Extrapulmonary infections associated with non-tuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1351-1358; quiz 1544.

- Saleeb PG, Drake SK, Murray PR, et al. Identification of mycobacteria in solid-culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1790-1794.

- Adams LL, Salee P, Dionne K, et al. A novel protein extraction method for identification of mycobacteria using MALDI-ToF MS. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;119:1-3.

- Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Garcovich A, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-reverse cross-blot hybridization assay in the diagnosis of sporotrichoid Mycobacterium marinum infection. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:872-876.

- Lau SK, Curreem SO, Ngan AH, et al. First report of disseminated Mycobacterium skin infections in two liver transplant recipients and rapid diagnosis by hsp65 gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3733-3738.

- Hofer M, Hirschel B, Kirschner P, et al. Brief report: disseminated osteomyelitis from Mycobacterium ulcerans after a snakebite. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1007-1009.

- Huang Y, Xu X, Liu Y, et al. Successful treatment of refractory cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium marinum with a combined regimen containing amikacin. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:533-538.

- Woods GL. Susceptibility testing for mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1209-1215.

- Balaqué N, Uçkay I, Vostrel P, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the hand. Chir Main. 2015;34:18-23.

- Pandian TK, Deziel PJ, Otley CC, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections in transplant recipients: case report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:358-363.

- Jacobs S, George A, Papanicolaou GA, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium marinum infection in a hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:410-414.

- Chow SP, Ip FK, Lau JH, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection of the hand and wrist. results of conservative treatment in twenty-four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1161-1168.

- Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978.

- Nenoff P, Klapper BM, Mayser P, et al. Infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: a review. Hautarzt. 2011;62:266-271.

- Prevost E, Walker EM Jr, Kreutner A Jr, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections: diagnosis and treatment. South Med J. 1982;75:1349-1352.

An environmental pathogen, Mycobacterium marinum can cause cutaneous infection when traumatized skin is exposed to fresh, brackish, or salt water. Fishing, aquarium cleaning, and aquatic recreational activities are risk factors for infection.1,2 Diagnosis often is delayed and is made several weeks or even months after initial symptoms appear.3 Due to the protracted clinical course, patients may not recall the initial exposure, contributing to the delay in diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. It is not uncommon for patients with M marinum infection to be initially treated with antibiotics or antifungal drugs.

We present a review of 5 patients who were diagnosed with M marinum infection at our institution between January 2003 and March 2013.

Methods

This study was conducted at Henry Ford Hospital, a 900-bed tertiary care center in Detroit, Michigan. Patients who had cultures positive for M marinum between January 2003 and March 2013 were identified using the institution’s laboratory database. Medical records were reviewed, and relevant demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical data, including initial clinical presentation, alternative diagnoses, time between initial presentation and definitive diagnosis, and specific treatment, were recorded.

Results

We identified 5 patients who were diagnosed with culture-confirmed M marinum skin infections during the study period: 3 men and 2 women aged 43 to 72 years (Table 1). Two patients had diabetes mellitus and 1 had hepatitis C virus. None had classic immunosuppression. On repeated questioning after the diagnosis was established, all 5 patients reported that they kept a home aquarium, and all recalled mild trauma to the hand prior to the onset of symptoms; however, none of the patients initially linked the minor skin injury to the subsequent infection.

All 5 patients initially presented with erythema and swelling at the site of the injury, which evolved into inflammatory nodules that progressed proximally up to the arm despite empiric treatment with antibiotics active against streptococci and staphylococci (Figures 1 and 2). Three patients also received empiric antifungal therapy due to suspicion of sporotrichosis.

Skin biopsies were performed on 4 patients, and incision and drainage of purulent material was performed on the fifth patient. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation in 3 patients. Stains for acid-fast bacilli were positive in all 5 patients. Definitive diagnosis of the organism was confirmed by growth of M marinum within 11 to 40 days from the tissue in 4 patients and purulent material in the fifth patient. Susceptibility testing was performed on only 1 of the 5 isolates and showed that the organism was susceptible to amikacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, ethambutol, rifampin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The mean time from initial presentation to initiation of appropriate therapy for M marinum infection was 91 days (range, 21–245 days). Several different treatment regimens were used. All patients received either doxycycline or minocycline with or without a macrolide. Two also received other agents (TMP-SMX or ethambutol). Treatment duration varied from 2 to 6 months in 4 patients, and all 4 had complete resolution of the lesions; 1 patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Diagnosing the Infection

Diagnosis of M marinum infection remains problematic. In the 5 patients included in this study, the time between initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis of M marinum infection was delayed, as has been noted in other reports.4-7 Delays as long as 2 years before the diagnosis is made have been described.7 The clinical presentation of cutaneous infection with M marinum varies, which may delay diagnosis. Nodular lymphangitis is classic, but papules, pustules, ulcers, inflammatory plaques, and single nodules also can occur.1,2 Lymphadenopathy may or may not be present.4,8,9 The differential diagnosis is broad and includes infection by other nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium chelonae; Mycobacterium fortuitum; Nocardia species, especially Nocardia brasiliensis; Francisella tularensis; Sporothrix schenckii; and Leishmania species. It is not surprising that 4 patients in our study were initially treated for a gram-positive bacterial infection and 3 were treated for a fungal infection before the diagnosis of M marinum was made. Distinctive features that may help to differentiate these infections are summarized in Table 2.

We found that the main cause of delayed diagnosis was the failure of physicians to obtain a thorough history regarding patients’ recreational activities and animal exposure. Patients often do not associate a remote aquatic exposure with their symptoms and will not volunteer this information unless directly asked.2,10 It was only after repeated questioning in all of these patients that they recounted prior trauma to the involved hand related to the aquarium.

Biopsy and Culture

Histopathologic examination of material from a biopsied lesion can give an early clue that a mycobacterial infection might be involved. Biopsy can reveal either noncaseating or necrotizing granulomas that have larger numbers of neutrophils in addition to lymphocytes and macrophages. Giant cells often are noted.5,9,11 Organisms can be seen with the use of a tissue acid-fast stain, but species cannot be differentiated by acid-fast staining.12 However, the sensitivity of acid-fast stains on biopsy material is low.3,13,14

Culture of the involved tissue is crucial for establishing the diagnosis of this infection. However, the rate of growth of M marinum is slow. Temperature requirements for incubation and delay in transporting specimens to the laboratory can lead to bacterial overgrowth, resulting in the inability to recover M marinum from the culture.13Mycobacterium marinum grows preferentially between 28°C and 32°C, and growth is limited at temperatures above 33°C.13,15,16 As illustrated in the cases presented, recovery of the organism may not be accomplished from the first culture performed, and additional biopsy material for culture may be needed. Liquid media generally is more sensitive and produces more rapid results than solid media (eg, Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar). However, solid media carry the advantage of allowing observation of morphology and estimation of the number of organisms.12,17

Rapid Detection

Advancements in molecular methods have allowed for more definitive and rapid identification of M marinum, substantially reducing the delay in diagnosis. Commercial molecular assays utilize in-solution hybridization or solid-format reverse-hybridization assays to allow mycobacterial detection as soon as growth appears.18 Use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry can substantially shorten the time to species identification.19,20 Nonculture-based tests that have been developed for the rapid detection of M marinum infection include polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism and polymerase chain reaction amplification of the 16S RNA gene.21 It should be noted, however, that M marinum and Mycobacterium ulcerans have a very homologous 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence, differing by only 1 nucleotide; thus, distinguishing between M marinum and M ulcerans using this method may be challenging.22,23

Management

Treatment depends on the extent of the disease. Generally, localized cutaneous disease can be treated with monotherapy with agents such as doxycycline, clarithromycin, or TMP-SMX. Extensive disease typically requires a combination of 2 antimycobacterial agents, typically clarithromycin-rifampin, clarithromycin-ethambutol, or rifampin-ethambutol.12 Amikacin has been used in combination with other agents such as rifampin and clarithromycin in refractory cases.22,24 The use of ciprofloxacin is not encouraged because some isolates are resistant; however, other fluoroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin, may be options for combination therapy. Isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin are not effective to treat M marinum.

Susceptibility testing of M marinum usually is performed to guide antimicrobial therapy in cases of poor clinical response or intolerance to first-line antimicrobials such as macrolides.25 The likelihood of M marinum developing resistance to the agents used for treatment appears to be low. Unfortunately, in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility tests do not correlate well with treatment efficiency.10

The duration of therapy is not standardized but usually is 5 to 6 months,7,10,26 with therapy often continuing 1 to 2 months after lesions appear to have resolved.12 However, in some cases (usually those who have more extensive disease), therapy has been extended to as long as 1 to 2 years.10 The ideal length of therapy in immunocompromised individuals has not been established27; however, a treatment duration of 6 to 9 months was reported in one study.28 Surgical debridement may be necessary in some patients who have involvement of deep structures of the hand or knee, those with persistent pain, or those who fail to respond to a prolonged period of medical therapy.29 Successful use of less conventional therapeutic approaches, including cryotherapy, radiation therapy, electrodesiccation, photodynamic therapy, curettage, and local hyperthermic therapy has been reported.30-32

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of M marinum infection is difficult. Patients presenting with indolent nodular skin infections affecting the upper extremities should be asked about aquatic exposure. Tissue biopsy for histopathologic examination and culture is essential to establish an early diagnosis and promptly initiate appropriate therapy.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Carol A. Kauffman, MD (Ann Arbor, Michigan), for her thoughtful comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

An environmental pathogen, Mycobacterium marinum can cause cutaneous infection when traumatized skin is exposed to fresh, brackish, or salt water. Fishing, aquarium cleaning, and aquatic recreational activities are risk factors for infection.1,2 Diagnosis often is delayed and is made several weeks or even months after initial symptoms appear.3 Due to the protracted clinical course, patients may not recall the initial exposure, contributing to the delay in diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. It is not uncommon for patients with M marinum infection to be initially treated with antibiotics or antifungal drugs.

We present a review of 5 patients who were diagnosed with M marinum infection at our institution between January 2003 and March 2013.

Methods

This study was conducted at Henry Ford Hospital, a 900-bed tertiary care center in Detroit, Michigan. Patients who had cultures positive for M marinum between January 2003 and March 2013 were identified using the institution’s laboratory database. Medical records were reviewed, and relevant demographic, epidemiologic, and clinical data, including initial clinical presentation, alternative diagnoses, time between initial presentation and definitive diagnosis, and specific treatment, were recorded.

Results

We identified 5 patients who were diagnosed with culture-confirmed M marinum skin infections during the study period: 3 men and 2 women aged 43 to 72 years (Table 1). Two patients had diabetes mellitus and 1 had hepatitis C virus. None had classic immunosuppression. On repeated questioning after the diagnosis was established, all 5 patients reported that they kept a home aquarium, and all recalled mild trauma to the hand prior to the onset of symptoms; however, none of the patients initially linked the minor skin injury to the subsequent infection.

All 5 patients initially presented with erythema and swelling at the site of the injury, which evolved into inflammatory nodules that progressed proximally up to the arm despite empiric treatment with antibiotics active against streptococci and staphylococci (Figures 1 and 2). Three patients also received empiric antifungal therapy due to suspicion of sporotrichosis.

Skin biopsies were performed on 4 patients, and incision and drainage of purulent material was performed on the fifth patient. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation in 3 patients. Stains for acid-fast bacilli were positive in all 5 patients. Definitive diagnosis of the organism was confirmed by growth of M marinum within 11 to 40 days from the tissue in 4 patients and purulent material in the fifth patient. Susceptibility testing was performed on only 1 of the 5 isolates and showed that the organism was susceptible to amikacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, ethambutol, rifampin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX).

The mean time from initial presentation to initiation of appropriate therapy for M marinum infection was 91 days (range, 21–245 days). Several different treatment regimens were used. All patients received either doxycycline or minocycline with or without a macrolide. Two also received other agents (TMP-SMX or ethambutol). Treatment duration varied from 2 to 6 months in 4 patients, and all 4 had complete resolution of the lesions; 1 patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Diagnosing the Infection

Diagnosis of M marinum infection remains problematic. In the 5 patients included in this study, the time between initial onset of symptoms and diagnosis of M marinum infection was delayed, as has been noted in other reports.4-7 Delays as long as 2 years before the diagnosis is made have been described.7 The clinical presentation of cutaneous infection with M marinum varies, which may delay diagnosis. Nodular lymphangitis is classic, but papules, pustules, ulcers, inflammatory plaques, and single nodules also can occur.1,2 Lymphadenopathy may or may not be present.4,8,9 The differential diagnosis is broad and includes infection by other nontuberculous mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium chelonae; Mycobacterium fortuitum; Nocardia species, especially Nocardia brasiliensis; Francisella tularensis; Sporothrix schenckii; and Leishmania species. It is not surprising that 4 patients in our study were initially treated for a gram-positive bacterial infection and 3 were treated for a fungal infection before the diagnosis of M marinum was made. Distinctive features that may help to differentiate these infections are summarized in Table 2.

We found that the main cause of delayed diagnosis was the failure of physicians to obtain a thorough history regarding patients’ recreational activities and animal exposure. Patients often do not associate a remote aquatic exposure with their symptoms and will not volunteer this information unless directly asked.2,10 It was only after repeated questioning in all of these patients that they recounted prior trauma to the involved hand related to the aquarium.

Biopsy and Culture

Histopathologic examination of material from a biopsied lesion can give an early clue that a mycobacterial infection might be involved. Biopsy can reveal either noncaseating or necrotizing granulomas that have larger numbers of neutrophils in addition to lymphocytes and macrophages. Giant cells often are noted.5,9,11 Organisms can be seen with the use of a tissue acid-fast stain, but species cannot be differentiated by acid-fast staining.12 However, the sensitivity of acid-fast stains on biopsy material is low.3,13,14

Culture of the involved tissue is crucial for establishing the diagnosis of this infection. However, the rate of growth of M marinum is slow. Temperature requirements for incubation and delay in transporting specimens to the laboratory can lead to bacterial overgrowth, resulting in the inability to recover M marinum from the culture.13Mycobacterium marinum grows preferentially between 28°C and 32°C, and growth is limited at temperatures above 33°C.13,15,16 As illustrated in the cases presented, recovery of the organism may not be accomplished from the first culture performed, and additional biopsy material for culture may be needed. Liquid media generally is more sensitive and produces more rapid results than solid media (eg, Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar). However, solid media carry the advantage of allowing observation of morphology and estimation of the number of organisms.12,17

Rapid Detection

Advancements in molecular methods have allowed for more definitive and rapid identification of M marinum, substantially reducing the delay in diagnosis. Commercial molecular assays utilize in-solution hybridization or solid-format reverse-hybridization assays to allow mycobacterial detection as soon as growth appears.18 Use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry can substantially shorten the time to species identification.19,20 Nonculture-based tests that have been developed for the rapid detection of M marinum infection include polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism and polymerase chain reaction amplification of the 16S RNA gene.21 It should be noted, however, that M marinum and Mycobacterium ulcerans have a very homologous 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence, differing by only 1 nucleotide; thus, distinguishing between M marinum and M ulcerans using this method may be challenging.22,23

Management

Treatment depends on the extent of the disease. Generally, localized cutaneous disease can be treated with monotherapy with agents such as doxycycline, clarithromycin, or TMP-SMX. Extensive disease typically requires a combination of 2 antimycobacterial agents, typically clarithromycin-rifampin, clarithromycin-ethambutol, or rifampin-ethambutol.12 Amikacin has been used in combination with other agents such as rifampin and clarithromycin in refractory cases.22,24 The use of ciprofloxacin is not encouraged because some isolates are resistant; however, other fluoroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin, may be options for combination therapy. Isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin are not effective to treat M marinum.

Susceptibility testing of M marinum usually is performed to guide antimicrobial therapy in cases of poor clinical response or intolerance to first-line antimicrobials such as macrolides.25 The likelihood of M marinum developing resistance to the agents used for treatment appears to be low. Unfortunately, in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility tests do not correlate well with treatment efficiency.10

The duration of therapy is not standardized but usually is 5 to 6 months,7,10,26 with therapy often continuing 1 to 2 months after lesions appear to have resolved.12 However, in some cases (usually those who have more extensive disease), therapy has been extended to as long as 1 to 2 years.10 The ideal length of therapy in immunocompromised individuals has not been established27; however, a treatment duration of 6 to 9 months was reported in one study.28 Surgical debridement may be necessary in some patients who have involvement of deep structures of the hand or knee, those with persistent pain, or those who fail to respond to a prolonged period of medical therapy.29 Successful use of less conventional therapeutic approaches, including cryotherapy, radiation therapy, electrodesiccation, photodynamic therapy, curettage, and local hyperthermic therapy has been reported.30-32

Conclusion

Diagnosis and management of M marinum infection is difficult. Patients presenting with indolent nodular skin infections affecting the upper extremities should be asked about aquatic exposure. Tissue biopsy for histopathologic examination and culture is essential to establish an early diagnosis and promptly initiate appropriate therapy.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Carol A. Kauffman, MD (Ann Arbor, Michigan), for her thoughtful comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

- Lewis FM, Marsh BJ, von Reyn CF. Fish tank exposure and cutaneous infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: tuberculin skin testing, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:390-397.

- Jernigan JA, Farr BM. Incubation period and sources of exposure for cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:439-443.

- Edelstein H. Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. report of 31 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1359-1364.

- Janik JP, Bang RH, Palmer CH. Case reports: successful treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection with minocycline after complication of disease by delayed diagnosis and systemic steroids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:621-624.

- Jolly HW Jr, Seabury JH. Infections with Myocbacterium marinum. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:32-36.

- Sette CS, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection: a case report. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:7.

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662.

- Eberst E, Dereure O, Guillot B, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic pattern of Mycobacterium marinum infection: a retrospective series of 35 cases from southern France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E15-E16.

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma. a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162.

- Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, et al. Sixty-three cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: clinical features, treatment, and antibiotic susceptibility of causative isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1746-1752.

- Feng Y, Xu H, Wang H, et al. Outbreak of a cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection in Jiangsu Haian, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:267-272.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:343-347.

- Wu TS, Chiu CH, Yang CH, et al. Fish tank granuloma caused by Mycobacterium marinum. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41296.

- Ho WL, Chuang WY, Kuo AJ, et al. Nasal fish tank granuloma: an uncommon cause for epistaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:195-196.

- Dobos KM, Quinn FD, Ashford DA, et al. Emergence of a unique group of necrotizing mycobacterial diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:367-378.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109.

- Piersimoni C, Scarparo C. Extrapulmonary infections associated with non-tuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1351-1358; quiz 1544.

- Saleeb PG, Drake SK, Murray PR, et al. Identification of mycobacteria in solid-culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1790-1794.

- Adams LL, Salee P, Dionne K, et al. A novel protein extraction method for identification of mycobacteria using MALDI-ToF MS. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;119:1-3.

- Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Garcovich A, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-reverse cross-blot hybridization assay in the diagnosis of sporotrichoid Mycobacterium marinum infection. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:872-876.

- Lau SK, Curreem SO, Ngan AH, et al. First report of disseminated Mycobacterium skin infections in two liver transplant recipients and rapid diagnosis by hsp65 gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3733-3738.

- Hofer M, Hirschel B, Kirschner P, et al. Brief report: disseminated osteomyelitis from Mycobacterium ulcerans after a snakebite. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1007-1009.

- Huang Y, Xu X, Liu Y, et al. Successful treatment of refractory cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium marinum with a combined regimen containing amikacin. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:533-538.

- Woods GL. Susceptibility testing for mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1209-1215.

- Balaqué N, Uçkay I, Vostrel P, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the hand. Chir Main. 2015;34:18-23.

- Pandian TK, Deziel PJ, Otley CC, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections in transplant recipients: case report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:358-363.

- Jacobs S, George A, Papanicolaou GA, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium marinum infection in a hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:410-414.

- Chow SP, Ip FK, Lau JH, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection of the hand and wrist. results of conservative treatment in twenty-four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1161-1168.

- Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978.

- Nenoff P, Klapper BM, Mayser P, et al. Infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: a review. Hautarzt. 2011;62:266-271.

- Prevost E, Walker EM Jr, Kreutner A Jr, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections: diagnosis and treatment. South Med J. 1982;75:1349-1352.

- Lewis FM, Marsh BJ, von Reyn CF. Fish tank exposure and cutaneous infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: tuberculin skin testing, treatment, and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:390-397.

- Jernigan JA, Farr BM. Incubation period and sources of exposure for cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:439-443.

- Edelstein H. Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. report of 31 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1359-1364.

- Janik JP, Bang RH, Palmer CH. Case reports: successful treatment of Mycobacterium marinum infection with minocycline after complication of disease by delayed diagnosis and systemic steroids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:621-624.

- Jolly HW Jr, Seabury JH. Infections with Myocbacterium marinum. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:32-36.

- Sette CS, Wachholz PA, Masuda PY, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection: a case report. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. 2015;21:7.

- Johnson MG, Stout JE. Twenty-eight cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: retrospective case series and literature review. Infection. 2015;43:655-662.

- Eberst E, Dereure O, Guillot B, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and therapeutic pattern of Mycobacterium marinum infection: a retrospective series of 35 cases from southern France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E15-E16.

- Philpott JA Jr, Woodburne AR, Philpott OS, et al. Swimming pool granuloma. a study of 290 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:158-162.

- Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, et al. Sixty-three cases of Mycobacterium marinum infection: clinical features, treatment, and antibiotic susceptibility of causative isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1746-1752.

- Feng Y, Xu H, Wang H, et al. Outbreak of a cutaneous Mycobacterium marinum infection in Jiangsu Haian, China. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;71:267-272.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of non-tuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:343-347.

- Wu TS, Chiu CH, Yang CH, et al. Fish tank granuloma caused by Mycobacterium marinum. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41296.

- Ho WL, Chuang WY, Kuo AJ, et al. Nasal fish tank granuloma: an uncommon cause for epistaxis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:195-196.

- Dobos KM, Quinn FD, Ashford DA, et al. Emergence of a unique group of necrotizing mycobacterial diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:367-378.

- van Ingen J. Diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:103-109.

- Piersimoni C, Scarparo C. Extrapulmonary infections associated with non-tuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1351-1358; quiz 1544.

- Saleeb PG, Drake SK, Murray PR, et al. Identification of mycobacteria in solid-culture media by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1790-1794.

- Adams LL, Salee P, Dionne K, et al. A novel protein extraction method for identification of mycobacteria using MALDI-ToF MS. J Microbiol Methods. 2015;119:1-3.

- Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Garcovich A, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-reverse cross-blot hybridization assay in the diagnosis of sporotrichoid Mycobacterium marinum infection. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:872-876.

- Lau SK, Curreem SO, Ngan AH, et al. First report of disseminated Mycobacterium skin infections in two liver transplant recipients and rapid diagnosis by hsp65 gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3733-3738.

- Hofer M, Hirschel B, Kirschner P, et al. Brief report: disseminated osteomyelitis from Mycobacterium ulcerans after a snakebite. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1007-1009.

- Huang Y, Xu X, Liu Y, et al. Successful treatment of refractory cutaneous infection caused by Mycobacterium marinum with a combined regimen containing amikacin. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:533-538.

- Woods GL. Susceptibility testing for mycobacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1209-1215.

- Balaqué N, Uçkay I, Vostrel P, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections of the hand. Chir Main. 2015;34:18-23.

- Pandian TK, Deziel PJ, Otley CC, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections in transplant recipients: case report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:358-363.

- Jacobs S, George A, Papanicolaou GA, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium marinum infection in a hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:410-414.

- Chow SP, Ip FK, Lau JH, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infection of the hand and wrist. results of conservative treatment in twenty-four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1161-1168.

- Rallis E, Koumantaki-Mathioudaki E. Treatment of Mycobacterium marinum cutaneous infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2965-2978.

- Nenoff P, Klapper BM, Mayser P, et al. Infections due to Mycobacterium marinum: a review. Hautarzt. 2011;62:266-271.

- Prevost E, Walker EM Jr, Kreutner A Jr, et al. Mycobacterium marinum infections: diagnosis and treatment. South Med J. 1982;75:1349-1352.

Practice Points

- Mycobacterium marinum infection should be suspected in patients with skin/soft tissue infections that fail to respond or progress despite treatment with antibiotics active against streptococci and staphylococci.

- Inquiring about environmental exposure prior to the onset of the symptoms is key to elaborate a differential diagnosis list.

- Biopsy for pathology evaluation and acid-fast bacilli smear and culture are key to establish the diagnosis of M marinum infection.