User login

Revisiting our approach to behavioral health referrals

Approximately 1 in 4 people ages 18 years and older and 1 in 3 people ages 18 to 25 years had a mental illness in the past year, according to the 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.1 The survey also found that adults ages 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of serious mental illness but the lowest treatment rate compared to other adult age groups.1 Unfortunately, more than 60% of patients receiving mental health treatment fail to benefit to a clinically meaningful degree.2

However, there is growing evidence that referring patients to behavioral health practitioners (BHPs) with outcome-measured skills that meet the patient’s specific needs can have a dramatic and positive impact. There are 2 main steps to pairing patients with an appropriate BHP: (1) use of measurement-based care data that can be analyzed at the patient and therapist level, and (2) data-driven referrals that pair patients with BHPs based on such routine outcome monitoring data (paired-on outcome data).

Psychotherapy’s slow road toward measurement-based care

Routine outcome monitoring is the systematic measurement of symptoms and functioning during treatment. It serves multiple functions, including program evaluation and benchmarking of patient improvement rates. Moreover, routine outcome monitoring–derived feedback (based on repeated patient outcome measurements) can inform personalized and responsive care decisions throughout treatment.

For all intents and purposes,

- routinely administered symptom/functioning measure, ideally before each clinical encounter,

- practitioner review of these patient-level data,

- patient review of these data with their practitioner, and

- collaborative reevaluation of the person-specific treatment plan informed by these data.

CASE SCENARIO

Violeta W is a 33-year-old woman who presented to her family physician for her annual wellness exam. Prior to the exam, the medical assistant administered a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depressive symptoms. Ms. W’s score was 20 out of 27, suggestive of depression. To further assess the severity of depressive symptoms and their effect on daily function, the physician reviewed responses to the questionnaire with her and discussed treatment options. Ms. W was most interested in trying a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

At her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the medical assistant re-administered the PHQ-9. The physician then reviewed Ms. W’s responses with her and, based on Ms. W’s subjective report and objective symptoms (still a score of 20 out of 27 on the PHQ-9), increased her SSRI dose. At each subsequent visit, Ms. W completed a PHQ-9 and reviewed responses and depressive symptoms with her physician.

The value of measurement-based care in mental health care

A narrative review by Lewis et al3 of 21 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) across a range of age groups (eg, adolescents, young adults, adults), disorders (eg, anxiety, mood), and settings (eg, outpatient, inpatient) found that in at least 9 review articles, measurement-based care was associated with significantly improved outcomes vs usual care (ie, treatment without routine outcome monitoring plus feedback). The average increase in treatment effect size was about 30% when treatment was accompanied by measurement-based care.3

Continue to: Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis...

Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 shows that measurement-based care yields a small but significant increase in therapeutic outcomes (d = .15). Use of measurement-based care also is associated with improved communication between the patient and therapist.5 In pharmacotherapy practice, measurement-based care has been shown to predict rapid dose increases and changes in medication, when necessary; faster recovery rates; higher response rates to treatment3; and fewer dropouts.4

Perhaps one of the best-studied benefits of measurement-based mental health care is the ability to predict deterioration in care (ie, patients who are off-track in a way that practitioners often miss without the help of routine outcome monitoring data).6,7 Studies show that without a data-informed approach to care, some forms of psychotherapy or therapy with BHPs who are not sufficiently skilled in treating a given diagnosis increase symptoms or create significant harmful and iatrogenic effects.8-10 Conversely, the meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 found a lower percentage of deterioration in patients receiving measurement-based care. The difference in deterioration was significant: An average of 5.4% of patients in control conditions deteriorated compared to an average of 4.6% in feedback (measurement-based care) groups. There were even larger effect sizes when therapists received training in the feedback system.4

Routine outcome monitoring without a dialogue between patient and practitioner about the assessments (eg, ignoring complete measurement-based care requirements) may be inadequate. A recent review by Muir et al6 found no differences in patient outcomes when data were used solely for aggregate quality improvement activities, suggesting the need for practitioners to review results of routine outcome monitoring assessments with patients and use data to alter care when necessary.

Measurement-based care is believed to deliver benefits and reduce harm by enhancing and encouraging active patient involvement, improving patient understanding of symptoms, promoting better communication, and facilitating better care coordination.3 The benefits of measurement-based care can be enhanced with a comprehensive core routine outcome monitoring tool and the level of monitoring-generated information delivered for multiple stakeholders (eg, patient, therapist, clinic).11

A look at multidimensional assessment

The features of routine outcome monitoring tools vary significantly.12 Some measures assess single-symptom or problem domains (eg, PHQ-9 for depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] scale for anxiety) or multiple dimensions (multidimensional routine outcome monitoring). Multidimensional routine outcome monitoring may have benefits over single-domain measures. Single-domain measures and the subscales or factors of more comprehensive multidimensional routine outcome monitoring assessments should possess adequate specificity and sensitivity.

Continue to: Some recent research findings...

Some recent research findings question the construct validity of brief single-domain measures of common presenting problems, such as depression and anxiety. For example, results from a factor analysis of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scale in patients with traumatic brain injury suggest these tools measure 1 psychological construct that includes depression and the cognitive components of anxiety (eg, worry)13—a finding consistent with those of other tools.14 Similarly, a larger study of 7763 BH patients found that a single factor accounted for most of the variance of the 2 combined measures, with no set of factors meeting the exacting standards used to develop multidimensional routine outcome monitoring.15 These findings suggest that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 largely overlap and are not measuring different aspects of health as most practitioners believe (eg, depression and anxiety).

In commonly used assessments, multiple-factor analytic studies with high standards have supported the construct validity of domain-specific subscales, indicating that the various questions tap into different constructs of psychological health.14,16,17

Beyond multiple domain–specific indicators, multidimensional routine outcome measurements provide a global total score that minimizes Type I (false-positive conclusion) and Type II (false-negative conclusion) errors in tracking patient improvement or deterioration.18 As one would expect, multidimensional routine outcome monitoring generally includes more items than single-domain measures; however, this comes with a trade-off. If there are specificity and sensitivity concerns with an ultra-brief single-domain measure, an alternative to a core multidimensional routine outcome measurement is to aggregate a series of single-domain measures into a battery of patient self-reports. However, this approach may take longer for patients to complete since they would have to shift among the varying response sets and wording across the unique single-domain measures.

In addition, the standardization/normalization of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring likely makes interpretation easier than referring to norms and clinical severity cutoffs for many distinct measures. Furthermore, increased specificity enhances predictive power and allows BHPs to screen and track other conditions besides depression and anxiety. (It is worth noting that there are no known studies that have looked at the difference in time to administer or ease of interpretation of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools vs multiple single-domain measures.)

Two multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools that cover a comprehensive series of discrete symptom and functional domains are the Treatment Outcome Package12 and Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms.16 These tools, which include subscales beyond general depression and anxiety (eg, sleep, substance misuse, social conflict), take 7 to 10 minutes to complete and provide outcome results across 12 symptom and 8 functional dimensions. As an example, the Treatment Outcome Package has good psychometric qualities (eg, reliability, construct and concurrent validity) for adults,12 children,14,19 and adolescents,19 and can be administered through a secure online data collection portal. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms has demonstrated high construct validity and good convergent validity.16 These assessments can be administered in paper or digital (eg, electronic medical record portal, smartphone) format.20

Continue to: CASE SCENARIO

CASE SCENARIO

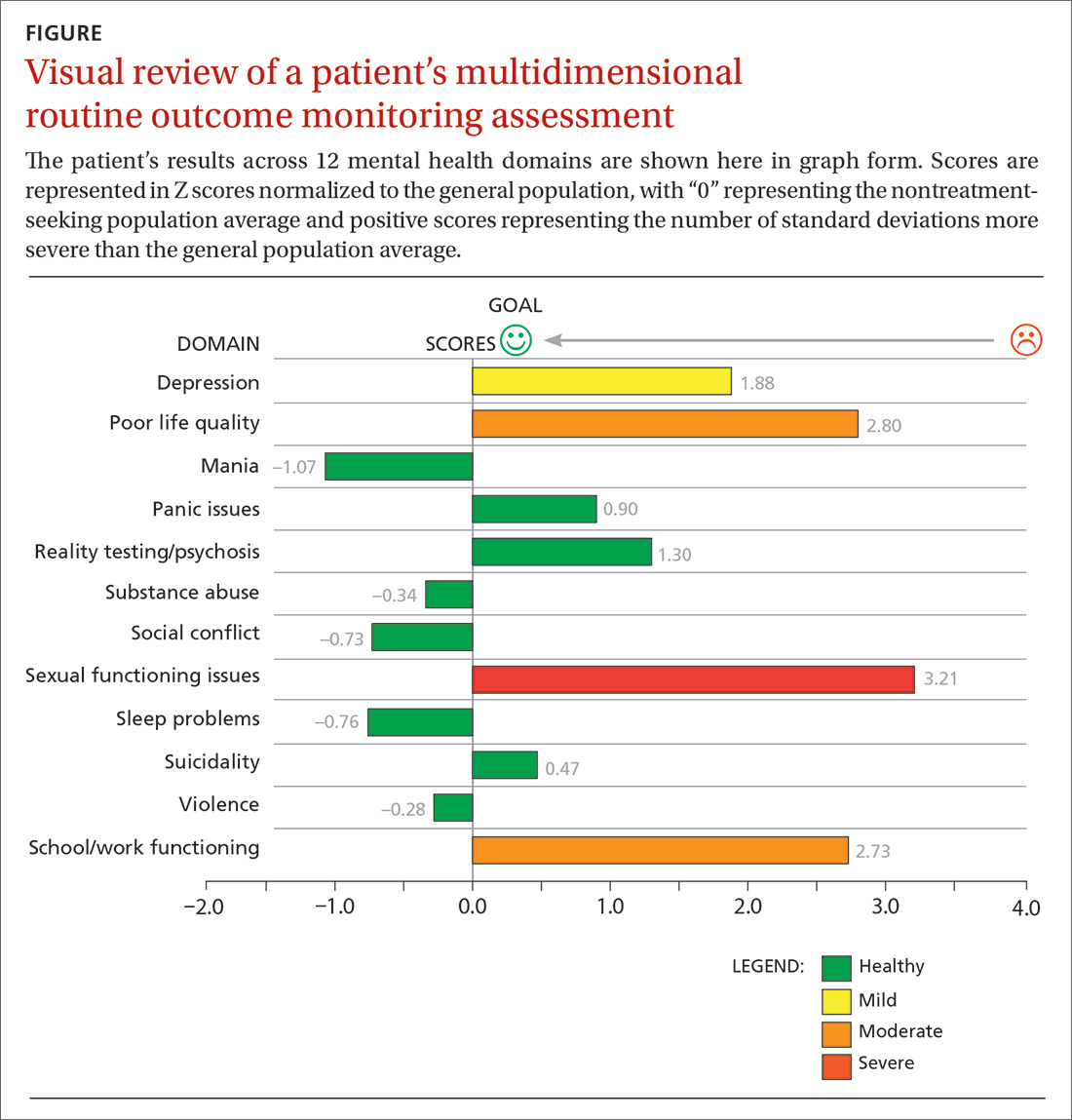

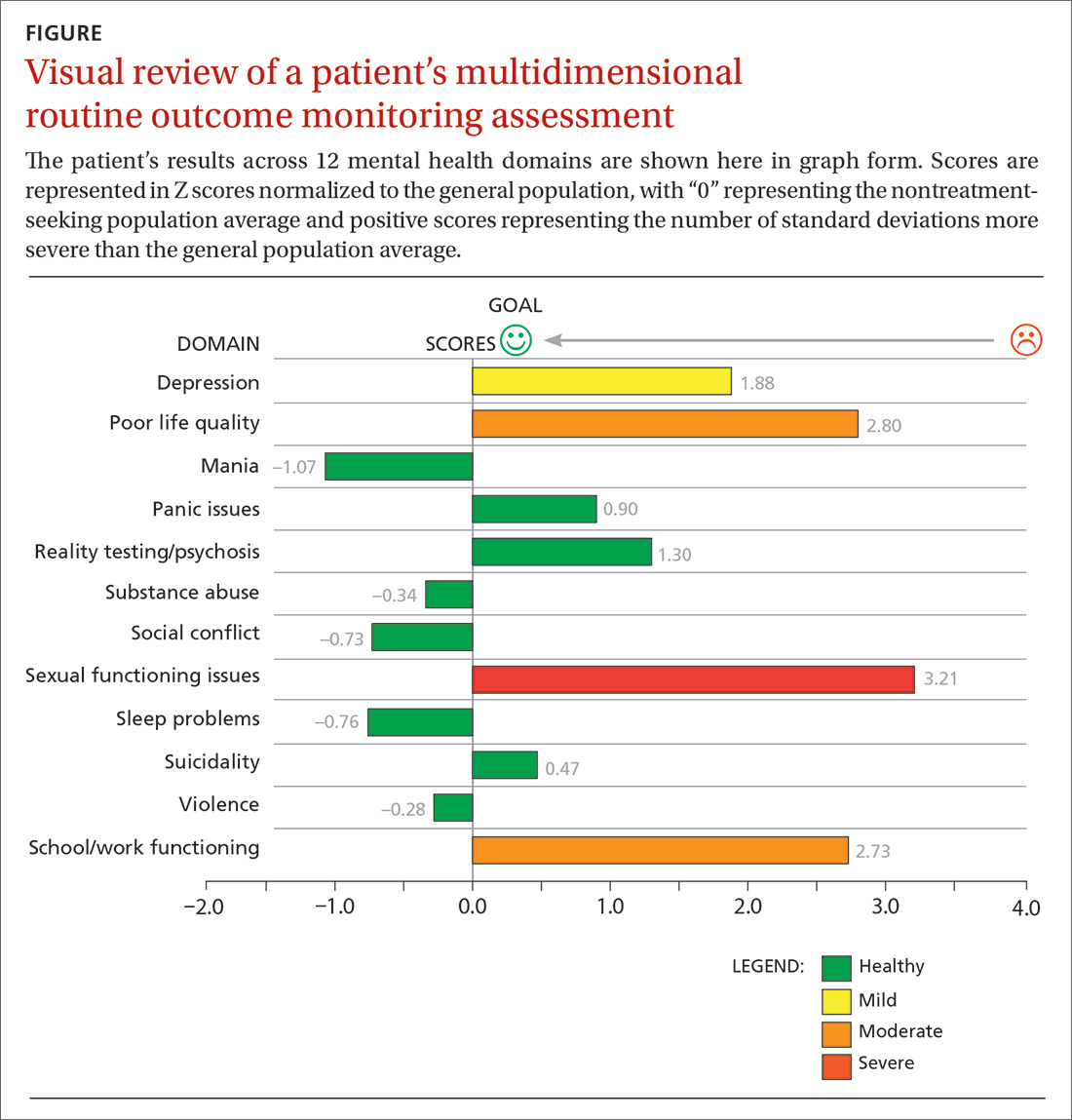

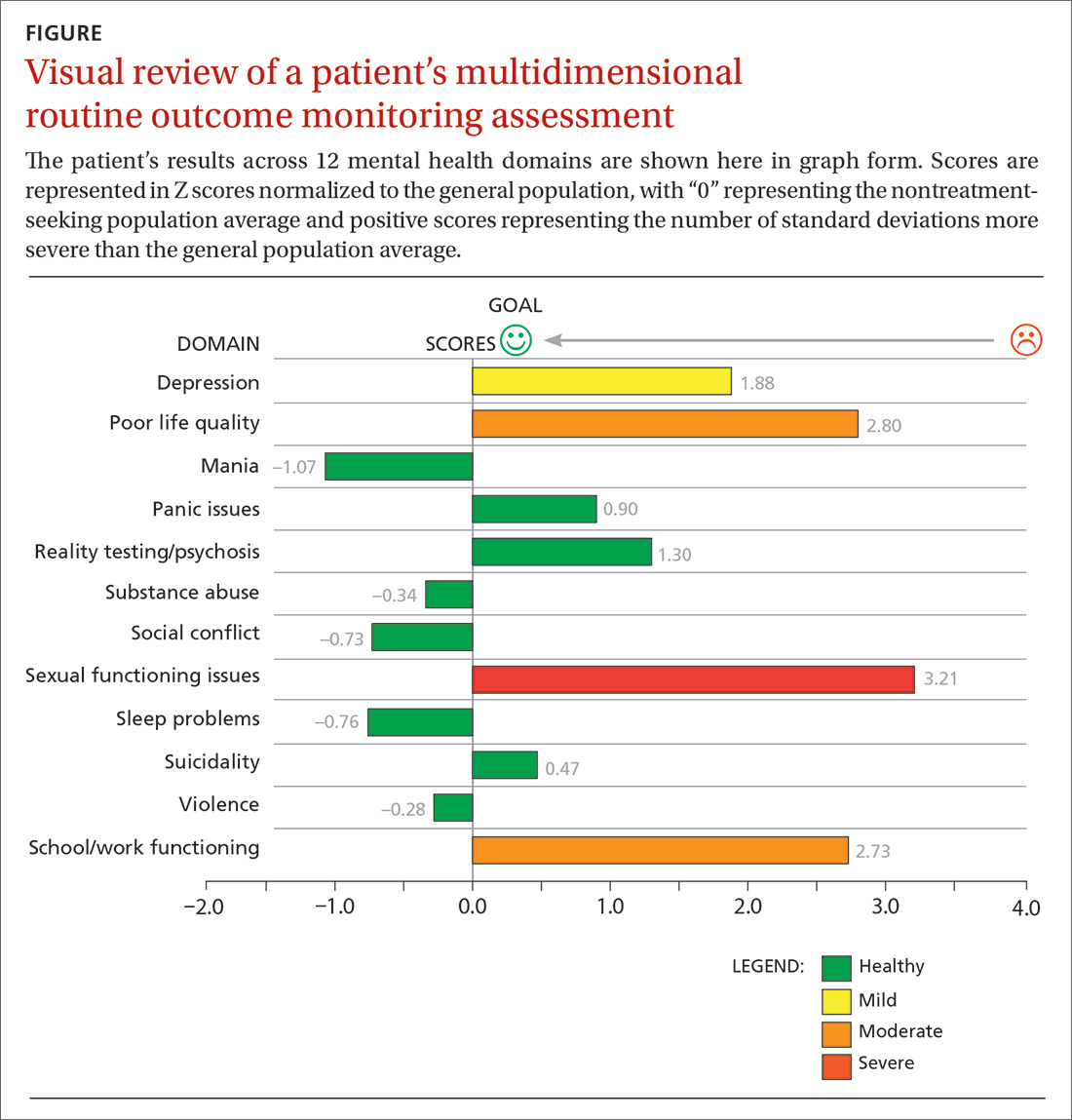

Ms. W’s physician asked her to go online using her phone and answer the questions in the Treatment Outcome Package. Her results, which she viewed with her physician, were displayed in graph form (FIGURE). Her scores were represented in Z scores normalized to the general population, with “0” representing the general, nontreatment-seeking population average and positive scores representing the number of standard deviations (SDs) more severe than the general population average.

Although this assessment scored Ms. W’s clinically elevated depression as mild, it revealed abnormalities in 3 other domains. Sexual functioning issues represented the most abnormal domain at greater than 3 SDs (more severe than the general population), followed by poor life quality and school/work functioning.

After reviewing Ms. W’s report, her physician decided that pharmacologic management alone (for depression) was not the most appropriate treatment course. Therefore, her physician recommended psychotherapy in addition to the SSRI she was taking. Ms. W agreed to a customized referral for psychotherapy.

Data-driven referrals

When psychotherapy is chosen as a treatment, the individual BHP is an active component of that treatment. Consequently, it is essential to customize referrals to match a patient’s most elevated mental health concerns with a therapist who will most effectively treat those domains. It is rare for a BHP to be skilled in treating every mental health domain.9 Multiple studies have shown that BHPs have identifiable treatment skills in specific domains, which physicians should consider when making referrals.9,21,22 These studies demonstrate the utility of aggregating patient-level routine outcome monitoring data to better understand therapist-level (and ultimately clinic- and system-level) outcomes.

Additionally, recent research has tested this idea prospectively. An RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute and published in JAMA Psychiatry showed a significant and positive effect on patient outcomes (ie, reductions in general impairment, impairment involving a patient’s most elevated domain, and global distress) using paired-on outcome data matching vs as-usual matching protocols (eg, therapist self-defined areas of specialty).22 In the RCT, the most effective matching protocol was a combination of eliminating harm and matching the patient on their 3 most problematic domains (the highest match level). These patients ended care as healthy as the general population after 16 weeks of treatment. A random 1-year follow-up assessment from the original RCT showed that most patients who had been matched had maintained their improvement.23

Continue to: Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome...

Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool can be used to identify a BHP’s relative strengths and weaknesses across multiple outcome domains. Within a system of care, a sample of BHPs will possess varying outcome-domain profiles. When a new patient is seeking a referral to a BHP, these profiles (or domain-specific outcome track records) can be used to support paired-on outcome data matching. Specifically, a new patient completes the multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool at pretreatment, and the results reveal the outcome domains on which the patient is most clinically severe. This pattern of domain-specific severity then can be used to pair the new patient with a BHP who has demonstrated success in addressing the same outcome domain(s). This approach matches a new patient to a BHP with established expertise based on routine outcome monitoring.

Retrospective and prospective studies have found that most BHPs have stable performance in their strengths and weaknesses.11,21 One study found that assessing BHP performance with their most recent 30 patients can reliably predict future performance with their next 30 patients.24 This predictability in a practitioner’s outcomes suggests report cards that are updated frequently can be utilized to make case assignments within BH or referrals to a specific BHP from primary care.

Making a paired-on outcome data–matched referral

Making customized BH referrals requires access to information about a practitioner’s previous routine outcome monitoring data per clinical domain (eg, suicidality, violence, quality of life) from their most recent patients. Previous research suggests that follow-up data from a minimum of 15 patients is necessary to make a reliable evaluation of a practitioner’s strengths and weaknesses (ie, effectiveness “report card”) per clinical domain.24

Few, if any, physicians have access to this level of updated outcome data from their referral network. To facilitate widespread use of paired-on outcome data matching, a new Web system (MatchedTherapists.com) will allow the general public and PCPs to access these grades. As a public service option, this site currently allows for a self-assessment using the Treatment Outcome Package. Pending versions will generate paired-on outcome data grades, and users will receive a list of local therapists available for in-person appointments as well as therapists available for virtual appointments. The paired-on outcome data grades are delivered in school-based letter grades. An “A+,” for example, represents the best matching grade. Users also will be able to sort and filter results for other criteria such as telemedicine, insurance, age, gender, and appointment availability. Currently, there are more than 77,000 therapists listed on the site nationwide. A basic listing is free.

CASE SCENARIO

After Ms. W took the multidimensional routine outcome assessment online, she received a list of therapists rank-ordered by paired-on outcome data grade, with the “A+” matches listed first. Three of the best-matched referrals accepted her insurance and were willing to see her through telemedicine. Therapists with available in-person appointments had a “B” grade. After discussing the options with her physician, Ms. W opted for telehealth counseling with the therapist whose profile she liked best. The therapist and PCP tracked her progress through routine outcome monitoring reporting until all her symptoms became subclinical.

Continue to: The future of a "referral bridge"

The future of a “referral bridge”

In this article, we present a solution to a common issue faced by mental health care patients: failure to benefit meaningfully from mental health treatment. Matching patients to specific BHPs based on effectiveness data regarding the therapist’s strengths and skills can improve patient outcomes and reduce harm. In addition, patients appear to value this approach. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–funded study demonstrated that patients value seeing practitioners who have a track record of successfully treating previous patients with similar issues.25,26 In many cases, patients indicated they would prioritize this matching process over other factors such as practitioners with a higher number of years of experience or the same demographic characteristics as the patient.25,26

These findings may represent a new area in the science of health care. Over the past century, major advances in diagnosis and treatment—the 2 primary pillars of health care—have turned the art of medicine into a science. However, the art of making referrals has not advanced commensurately, as there has been little attention focused on the “referral bridge” between these 2 pillars. As the studies reviewed in this paper demonstrate, a referral bridge deserves exploration in all fields of medicine.

CORRESPONDENCE

David R. Kraus, PhD, 1 Speen Street, Framingham, MA 01701; [email protected]

1. HHS. 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Accessed March 29, 2023. www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2021-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

2. Barkham M, Lambert, MJ. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, eds. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: 50th Anniversary Edition. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021:135-189.

3. Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:324-335. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

4. de Jong K, Conijn JM, Gallagher RAV, et al. Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: a multilevel meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

5. Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, et al. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

6. Muir HJ, Coyne AE, Morrison NR, et al. Ethical implications of routine outcomes monitoring for patients, psychotherapists, and mental health care systems. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56:459-469. doi: 10.1037/pst0000246

7. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155-163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108

8. Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, et al. Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. Am Psychol. 2010;65:34-49. doi: 10.1037/a0017330

9. Kraus DR, Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, et al. Therapist effectiveness: implications for accountability and patient care. Psychother Res. 2011;21:267-276. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.563249

10. Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x

11. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Kraus DR, et al. The expanding relevance of routinely collected outcome data for mental health care decision making. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:482-491. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0649-6

12. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, et al. Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: results from a comprehensive review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:441-466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

13. Teymoori A, Gorbunova A, Haghish FE, et al. Factorial structure and validity of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scales after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med. 2020;9:873. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030873

14. Kraus DR, Seligman DA, Jordan JR. Validation of a behavioral health treatment outcome and assessment tool designed for naturalistic settings: the Treatment Outcome Package. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:285‐314. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20084

15. Boothroyd L, Dagnan D, Muncer S. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire using Mokken scaling and confirmatory factor analysis. Health Prim Care. 2018;2:1-4. doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000145

16. Locke BD, Buzolitz JS, Lei PW, et al. Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97-109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282

17. Kraus DR, Boswell JF, Wright AGC, et al. Factor structure of the treatment outcome package for children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:627-640. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20675

18. McAleavey AA, Nordberg SS, Kraus D, et al. Errors in treatment outcome monitoring: implications for real-world psychotherapy. Can Psychol. 2010;53:105-114. doi: 10.1037/a0027833

19. Baxter EE, Alexander PC, Kraus DR, et al. Concurrent validation of the Treatment Outcome Package (TOP) for children and adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:2415-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0419-4

20. Gual-Montolio P, Martínez-Borba V, Bretón-López JM, et al. How are information and communication technologies supporting routine outcome monitoring and measurement-based care in psychotherapy? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093170

21. Kraus DR, Bentley JH, Alexander PC, et al. Predicting therapist effectiveness from their own practice-based evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:473‐483. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000083

22. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Coyne AE, et al. Effect of matching therapists to patients vs assignment as usual on adult psychotherapy outcomes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:960-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1221

23. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Kraus DR, et al. Matching patients with therapists to improve mental health care. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/matching-patients-therapists-improve-mental-health-care

24. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. National Academies Press; 2006. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11470/chapter/1

25. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. A multimethod study of mental health care patients’ attitudes toward clinician-level performance information. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:452-456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000366

26. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. Mental health care consumers’ relative valuing of clinician performance information. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:301‐308. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000264

Approximately 1 in 4 people ages 18 years and older and 1 in 3 people ages 18 to 25 years had a mental illness in the past year, according to the 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.1 The survey also found that adults ages 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of serious mental illness but the lowest treatment rate compared to other adult age groups.1 Unfortunately, more than 60% of patients receiving mental health treatment fail to benefit to a clinically meaningful degree.2

However, there is growing evidence that referring patients to behavioral health practitioners (BHPs) with outcome-measured skills that meet the patient’s specific needs can have a dramatic and positive impact. There are 2 main steps to pairing patients with an appropriate BHP: (1) use of measurement-based care data that can be analyzed at the patient and therapist level, and (2) data-driven referrals that pair patients with BHPs based on such routine outcome monitoring data (paired-on outcome data).

Psychotherapy’s slow road toward measurement-based care

Routine outcome monitoring is the systematic measurement of symptoms and functioning during treatment. It serves multiple functions, including program evaluation and benchmarking of patient improvement rates. Moreover, routine outcome monitoring–derived feedback (based on repeated patient outcome measurements) can inform personalized and responsive care decisions throughout treatment.

For all intents and purposes,

- routinely administered symptom/functioning measure, ideally before each clinical encounter,

- practitioner review of these patient-level data,

- patient review of these data with their practitioner, and

- collaborative reevaluation of the person-specific treatment plan informed by these data.

CASE SCENARIO

Violeta W is a 33-year-old woman who presented to her family physician for her annual wellness exam. Prior to the exam, the medical assistant administered a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depressive symptoms. Ms. W’s score was 20 out of 27, suggestive of depression. To further assess the severity of depressive symptoms and their effect on daily function, the physician reviewed responses to the questionnaire with her and discussed treatment options. Ms. W was most interested in trying a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

At her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the medical assistant re-administered the PHQ-9. The physician then reviewed Ms. W’s responses with her and, based on Ms. W’s subjective report and objective symptoms (still a score of 20 out of 27 on the PHQ-9), increased her SSRI dose. At each subsequent visit, Ms. W completed a PHQ-9 and reviewed responses and depressive symptoms with her physician.

The value of measurement-based care in mental health care

A narrative review by Lewis et al3 of 21 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) across a range of age groups (eg, adolescents, young adults, adults), disorders (eg, anxiety, mood), and settings (eg, outpatient, inpatient) found that in at least 9 review articles, measurement-based care was associated with significantly improved outcomes vs usual care (ie, treatment without routine outcome monitoring plus feedback). The average increase in treatment effect size was about 30% when treatment was accompanied by measurement-based care.3

Continue to: Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis...

Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 shows that measurement-based care yields a small but significant increase in therapeutic outcomes (d = .15). Use of measurement-based care also is associated with improved communication between the patient and therapist.5 In pharmacotherapy practice, measurement-based care has been shown to predict rapid dose increases and changes in medication, when necessary; faster recovery rates; higher response rates to treatment3; and fewer dropouts.4

Perhaps one of the best-studied benefits of measurement-based mental health care is the ability to predict deterioration in care (ie, patients who are off-track in a way that practitioners often miss without the help of routine outcome monitoring data).6,7 Studies show that without a data-informed approach to care, some forms of psychotherapy or therapy with BHPs who are not sufficiently skilled in treating a given diagnosis increase symptoms or create significant harmful and iatrogenic effects.8-10 Conversely, the meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 found a lower percentage of deterioration in patients receiving measurement-based care. The difference in deterioration was significant: An average of 5.4% of patients in control conditions deteriorated compared to an average of 4.6% in feedback (measurement-based care) groups. There were even larger effect sizes when therapists received training in the feedback system.4

Routine outcome monitoring without a dialogue between patient and practitioner about the assessments (eg, ignoring complete measurement-based care requirements) may be inadequate. A recent review by Muir et al6 found no differences in patient outcomes when data were used solely for aggregate quality improvement activities, suggesting the need for practitioners to review results of routine outcome monitoring assessments with patients and use data to alter care when necessary.

Measurement-based care is believed to deliver benefits and reduce harm by enhancing and encouraging active patient involvement, improving patient understanding of symptoms, promoting better communication, and facilitating better care coordination.3 The benefits of measurement-based care can be enhanced with a comprehensive core routine outcome monitoring tool and the level of monitoring-generated information delivered for multiple stakeholders (eg, patient, therapist, clinic).11

A look at multidimensional assessment

The features of routine outcome monitoring tools vary significantly.12 Some measures assess single-symptom or problem domains (eg, PHQ-9 for depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] scale for anxiety) or multiple dimensions (multidimensional routine outcome monitoring). Multidimensional routine outcome monitoring may have benefits over single-domain measures. Single-domain measures and the subscales or factors of more comprehensive multidimensional routine outcome monitoring assessments should possess adequate specificity and sensitivity.

Continue to: Some recent research findings...

Some recent research findings question the construct validity of brief single-domain measures of common presenting problems, such as depression and anxiety. For example, results from a factor analysis of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scale in patients with traumatic brain injury suggest these tools measure 1 psychological construct that includes depression and the cognitive components of anxiety (eg, worry)13—a finding consistent with those of other tools.14 Similarly, a larger study of 7763 BH patients found that a single factor accounted for most of the variance of the 2 combined measures, with no set of factors meeting the exacting standards used to develop multidimensional routine outcome monitoring.15 These findings suggest that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 largely overlap and are not measuring different aspects of health as most practitioners believe (eg, depression and anxiety).

In commonly used assessments, multiple-factor analytic studies with high standards have supported the construct validity of domain-specific subscales, indicating that the various questions tap into different constructs of psychological health.14,16,17

Beyond multiple domain–specific indicators, multidimensional routine outcome measurements provide a global total score that minimizes Type I (false-positive conclusion) and Type II (false-negative conclusion) errors in tracking patient improvement or deterioration.18 As one would expect, multidimensional routine outcome monitoring generally includes more items than single-domain measures; however, this comes with a trade-off. If there are specificity and sensitivity concerns with an ultra-brief single-domain measure, an alternative to a core multidimensional routine outcome measurement is to aggregate a series of single-domain measures into a battery of patient self-reports. However, this approach may take longer for patients to complete since they would have to shift among the varying response sets and wording across the unique single-domain measures.

In addition, the standardization/normalization of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring likely makes interpretation easier than referring to norms and clinical severity cutoffs for many distinct measures. Furthermore, increased specificity enhances predictive power and allows BHPs to screen and track other conditions besides depression and anxiety. (It is worth noting that there are no known studies that have looked at the difference in time to administer or ease of interpretation of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools vs multiple single-domain measures.)

Two multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools that cover a comprehensive series of discrete symptom and functional domains are the Treatment Outcome Package12 and Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms.16 These tools, which include subscales beyond general depression and anxiety (eg, sleep, substance misuse, social conflict), take 7 to 10 minutes to complete and provide outcome results across 12 symptom and 8 functional dimensions. As an example, the Treatment Outcome Package has good psychometric qualities (eg, reliability, construct and concurrent validity) for adults,12 children,14,19 and adolescents,19 and can be administered through a secure online data collection portal. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms has demonstrated high construct validity and good convergent validity.16 These assessments can be administered in paper or digital (eg, electronic medical record portal, smartphone) format.20

Continue to: CASE SCENARIO

CASE SCENARIO

Ms. W’s physician asked her to go online using her phone and answer the questions in the Treatment Outcome Package. Her results, which she viewed with her physician, were displayed in graph form (FIGURE). Her scores were represented in Z scores normalized to the general population, with “0” representing the general, nontreatment-seeking population average and positive scores representing the number of standard deviations (SDs) more severe than the general population average.

Although this assessment scored Ms. W’s clinically elevated depression as mild, it revealed abnormalities in 3 other domains. Sexual functioning issues represented the most abnormal domain at greater than 3 SDs (more severe than the general population), followed by poor life quality and school/work functioning.

After reviewing Ms. W’s report, her physician decided that pharmacologic management alone (for depression) was not the most appropriate treatment course. Therefore, her physician recommended psychotherapy in addition to the SSRI she was taking. Ms. W agreed to a customized referral for psychotherapy.

Data-driven referrals

When psychotherapy is chosen as a treatment, the individual BHP is an active component of that treatment. Consequently, it is essential to customize referrals to match a patient’s most elevated mental health concerns with a therapist who will most effectively treat those domains. It is rare for a BHP to be skilled in treating every mental health domain.9 Multiple studies have shown that BHPs have identifiable treatment skills in specific domains, which physicians should consider when making referrals.9,21,22 These studies demonstrate the utility of aggregating patient-level routine outcome monitoring data to better understand therapist-level (and ultimately clinic- and system-level) outcomes.

Additionally, recent research has tested this idea prospectively. An RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute and published in JAMA Psychiatry showed a significant and positive effect on patient outcomes (ie, reductions in general impairment, impairment involving a patient’s most elevated domain, and global distress) using paired-on outcome data matching vs as-usual matching protocols (eg, therapist self-defined areas of specialty).22 In the RCT, the most effective matching protocol was a combination of eliminating harm and matching the patient on their 3 most problematic domains (the highest match level). These patients ended care as healthy as the general population after 16 weeks of treatment. A random 1-year follow-up assessment from the original RCT showed that most patients who had been matched had maintained their improvement.23

Continue to: Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome...

Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool can be used to identify a BHP’s relative strengths and weaknesses across multiple outcome domains. Within a system of care, a sample of BHPs will possess varying outcome-domain profiles. When a new patient is seeking a referral to a BHP, these profiles (or domain-specific outcome track records) can be used to support paired-on outcome data matching. Specifically, a new patient completes the multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool at pretreatment, and the results reveal the outcome domains on which the patient is most clinically severe. This pattern of domain-specific severity then can be used to pair the new patient with a BHP who has demonstrated success in addressing the same outcome domain(s). This approach matches a new patient to a BHP with established expertise based on routine outcome monitoring.

Retrospective and prospective studies have found that most BHPs have stable performance in their strengths and weaknesses.11,21 One study found that assessing BHP performance with their most recent 30 patients can reliably predict future performance with their next 30 patients.24 This predictability in a practitioner’s outcomes suggests report cards that are updated frequently can be utilized to make case assignments within BH or referrals to a specific BHP from primary care.

Making a paired-on outcome data–matched referral

Making customized BH referrals requires access to information about a practitioner’s previous routine outcome monitoring data per clinical domain (eg, suicidality, violence, quality of life) from their most recent patients. Previous research suggests that follow-up data from a minimum of 15 patients is necessary to make a reliable evaluation of a practitioner’s strengths and weaknesses (ie, effectiveness “report card”) per clinical domain.24

Few, if any, physicians have access to this level of updated outcome data from their referral network. To facilitate widespread use of paired-on outcome data matching, a new Web system (MatchedTherapists.com) will allow the general public and PCPs to access these grades. As a public service option, this site currently allows for a self-assessment using the Treatment Outcome Package. Pending versions will generate paired-on outcome data grades, and users will receive a list of local therapists available for in-person appointments as well as therapists available for virtual appointments. The paired-on outcome data grades are delivered in school-based letter grades. An “A+,” for example, represents the best matching grade. Users also will be able to sort and filter results for other criteria such as telemedicine, insurance, age, gender, and appointment availability. Currently, there are more than 77,000 therapists listed on the site nationwide. A basic listing is free.

CASE SCENARIO

After Ms. W took the multidimensional routine outcome assessment online, she received a list of therapists rank-ordered by paired-on outcome data grade, with the “A+” matches listed first. Three of the best-matched referrals accepted her insurance and were willing to see her through telemedicine. Therapists with available in-person appointments had a “B” grade. After discussing the options with her physician, Ms. W opted for telehealth counseling with the therapist whose profile she liked best. The therapist and PCP tracked her progress through routine outcome monitoring reporting until all her symptoms became subclinical.

Continue to: The future of a "referral bridge"

The future of a “referral bridge”

In this article, we present a solution to a common issue faced by mental health care patients: failure to benefit meaningfully from mental health treatment. Matching patients to specific BHPs based on effectiveness data regarding the therapist’s strengths and skills can improve patient outcomes and reduce harm. In addition, patients appear to value this approach. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–funded study demonstrated that patients value seeing practitioners who have a track record of successfully treating previous patients with similar issues.25,26 In many cases, patients indicated they would prioritize this matching process over other factors such as practitioners with a higher number of years of experience or the same demographic characteristics as the patient.25,26

These findings may represent a new area in the science of health care. Over the past century, major advances in diagnosis and treatment—the 2 primary pillars of health care—have turned the art of medicine into a science. However, the art of making referrals has not advanced commensurately, as there has been little attention focused on the “referral bridge” between these 2 pillars. As the studies reviewed in this paper demonstrate, a referral bridge deserves exploration in all fields of medicine.

CORRESPONDENCE

David R. Kraus, PhD, 1 Speen Street, Framingham, MA 01701; [email protected]

Approximately 1 in 4 people ages 18 years and older and 1 in 3 people ages 18 to 25 years had a mental illness in the past year, according to the 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health.1 The survey also found that adults ages 18 to 25 years had the highest rate of serious mental illness but the lowest treatment rate compared to other adult age groups.1 Unfortunately, more than 60% of patients receiving mental health treatment fail to benefit to a clinically meaningful degree.2

However, there is growing evidence that referring patients to behavioral health practitioners (BHPs) with outcome-measured skills that meet the patient’s specific needs can have a dramatic and positive impact. There are 2 main steps to pairing patients with an appropriate BHP: (1) use of measurement-based care data that can be analyzed at the patient and therapist level, and (2) data-driven referrals that pair patients with BHPs based on such routine outcome monitoring data (paired-on outcome data).

Psychotherapy’s slow road toward measurement-based care

Routine outcome monitoring is the systematic measurement of symptoms and functioning during treatment. It serves multiple functions, including program evaluation and benchmarking of patient improvement rates. Moreover, routine outcome monitoring–derived feedback (based on repeated patient outcome measurements) can inform personalized and responsive care decisions throughout treatment.

For all intents and purposes,

- routinely administered symptom/functioning measure, ideally before each clinical encounter,

- practitioner review of these patient-level data,

- patient review of these data with their practitioner, and

- collaborative reevaluation of the person-specific treatment plan informed by these data.

CASE SCENARIO

Violeta W is a 33-year-old woman who presented to her family physician for her annual wellness exam. Prior to the exam, the medical assistant administered a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to screen for depressive symptoms. Ms. W’s score was 20 out of 27, suggestive of depression. To further assess the severity of depressive symptoms and their effect on daily function, the physician reviewed responses to the questionnaire with her and discussed treatment options. Ms. W was most interested in trying a low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI).

At her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the medical assistant re-administered the PHQ-9. The physician then reviewed Ms. W’s responses with her and, based on Ms. W’s subjective report and objective symptoms (still a score of 20 out of 27 on the PHQ-9), increased her SSRI dose. At each subsequent visit, Ms. W completed a PHQ-9 and reviewed responses and depressive symptoms with her physician.

The value of measurement-based care in mental health care

A narrative review by Lewis et al3 of 21 randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) across a range of age groups (eg, adolescents, young adults, adults), disorders (eg, anxiety, mood), and settings (eg, outpatient, inpatient) found that in at least 9 review articles, measurement-based care was associated with significantly improved outcomes vs usual care (ie, treatment without routine outcome monitoring plus feedback). The average increase in treatment effect size was about 30% when treatment was accompanied by measurement-based care.3

Continue to: Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis...

Moreover, a recent within-patient meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 shows that measurement-based care yields a small but significant increase in therapeutic outcomes (d = .15). Use of measurement-based care also is associated with improved communication between the patient and therapist.5 In pharmacotherapy practice, measurement-based care has been shown to predict rapid dose increases and changes in medication, when necessary; faster recovery rates; higher response rates to treatment3; and fewer dropouts.4

Perhaps one of the best-studied benefits of measurement-based mental health care is the ability to predict deterioration in care (ie, patients who are off-track in a way that practitioners often miss without the help of routine outcome monitoring data).6,7 Studies show that without a data-informed approach to care, some forms of psychotherapy or therapy with BHPs who are not sufficiently skilled in treating a given diagnosis increase symptoms or create significant harmful and iatrogenic effects.8-10 Conversely, the meta-analysis by de Jong et al4 found a lower percentage of deterioration in patients receiving measurement-based care. The difference in deterioration was significant: An average of 5.4% of patients in control conditions deteriorated compared to an average of 4.6% in feedback (measurement-based care) groups. There were even larger effect sizes when therapists received training in the feedback system.4

Routine outcome monitoring without a dialogue between patient and practitioner about the assessments (eg, ignoring complete measurement-based care requirements) may be inadequate. A recent review by Muir et al6 found no differences in patient outcomes when data were used solely for aggregate quality improvement activities, suggesting the need for practitioners to review results of routine outcome monitoring assessments with patients and use data to alter care when necessary.

Measurement-based care is believed to deliver benefits and reduce harm by enhancing and encouraging active patient involvement, improving patient understanding of symptoms, promoting better communication, and facilitating better care coordination.3 The benefits of measurement-based care can be enhanced with a comprehensive core routine outcome monitoring tool and the level of monitoring-generated information delivered for multiple stakeholders (eg, patient, therapist, clinic).11

A look at multidimensional assessment

The features of routine outcome monitoring tools vary significantly.12 Some measures assess single-symptom or problem domains (eg, PHQ-9 for depression or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [GAD-7] scale for anxiety) or multiple dimensions (multidimensional routine outcome monitoring). Multidimensional routine outcome monitoring may have benefits over single-domain measures. Single-domain measures and the subscales or factors of more comprehensive multidimensional routine outcome monitoring assessments should possess adequate specificity and sensitivity.

Continue to: Some recent research findings...

Some recent research findings question the construct validity of brief single-domain measures of common presenting problems, such as depression and anxiety. For example, results from a factor analysis of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scale in patients with traumatic brain injury suggest these tools measure 1 psychological construct that includes depression and the cognitive components of anxiety (eg, worry)13—a finding consistent with those of other tools.14 Similarly, a larger study of 7763 BH patients found that a single factor accounted for most of the variance of the 2 combined measures, with no set of factors meeting the exacting standards used to develop multidimensional routine outcome monitoring.15 These findings suggest that the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 largely overlap and are not measuring different aspects of health as most practitioners believe (eg, depression and anxiety).

In commonly used assessments, multiple-factor analytic studies with high standards have supported the construct validity of domain-specific subscales, indicating that the various questions tap into different constructs of psychological health.14,16,17

Beyond multiple domain–specific indicators, multidimensional routine outcome measurements provide a global total score that minimizes Type I (false-positive conclusion) and Type II (false-negative conclusion) errors in tracking patient improvement or deterioration.18 As one would expect, multidimensional routine outcome monitoring generally includes more items than single-domain measures; however, this comes with a trade-off. If there are specificity and sensitivity concerns with an ultra-brief single-domain measure, an alternative to a core multidimensional routine outcome measurement is to aggregate a series of single-domain measures into a battery of patient self-reports. However, this approach may take longer for patients to complete since they would have to shift among the varying response sets and wording across the unique single-domain measures.

In addition, the standardization/normalization of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring likely makes interpretation easier than referring to norms and clinical severity cutoffs for many distinct measures. Furthermore, increased specificity enhances predictive power and allows BHPs to screen and track other conditions besides depression and anxiety. (It is worth noting that there are no known studies that have looked at the difference in time to administer or ease of interpretation of multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools vs multiple single-domain measures.)

Two multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tools that cover a comprehensive series of discrete symptom and functional domains are the Treatment Outcome Package12 and Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms.16 These tools, which include subscales beyond general depression and anxiety (eg, sleep, substance misuse, social conflict), take 7 to 10 minutes to complete and provide outcome results across 12 symptom and 8 functional dimensions. As an example, the Treatment Outcome Package has good psychometric qualities (eg, reliability, construct and concurrent validity) for adults,12 children,14,19 and adolescents,19 and can be administered through a secure online data collection portal. The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms has demonstrated high construct validity and good convergent validity.16 These assessments can be administered in paper or digital (eg, electronic medical record portal, smartphone) format.20

Continue to: CASE SCENARIO

CASE SCENARIO

Ms. W’s physician asked her to go online using her phone and answer the questions in the Treatment Outcome Package. Her results, which she viewed with her physician, were displayed in graph form (FIGURE). Her scores were represented in Z scores normalized to the general population, with “0” representing the general, nontreatment-seeking population average and positive scores representing the number of standard deviations (SDs) more severe than the general population average.

Although this assessment scored Ms. W’s clinically elevated depression as mild, it revealed abnormalities in 3 other domains. Sexual functioning issues represented the most abnormal domain at greater than 3 SDs (more severe than the general population), followed by poor life quality and school/work functioning.

After reviewing Ms. W’s report, her physician decided that pharmacologic management alone (for depression) was not the most appropriate treatment course. Therefore, her physician recommended psychotherapy in addition to the SSRI she was taking. Ms. W agreed to a customized referral for psychotherapy.

Data-driven referrals

When psychotherapy is chosen as a treatment, the individual BHP is an active component of that treatment. Consequently, it is essential to customize referrals to match a patient’s most elevated mental health concerns with a therapist who will most effectively treat those domains. It is rare for a BHP to be skilled in treating every mental health domain.9 Multiple studies have shown that BHPs have identifiable treatment skills in specific domains, which physicians should consider when making referrals.9,21,22 These studies demonstrate the utility of aggregating patient-level routine outcome monitoring data to better understand therapist-level (and ultimately clinic- and system-level) outcomes.

Additionally, recent research has tested this idea prospectively. An RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute and published in JAMA Psychiatry showed a significant and positive effect on patient outcomes (ie, reductions in general impairment, impairment involving a patient’s most elevated domain, and global distress) using paired-on outcome data matching vs as-usual matching protocols (eg, therapist self-defined areas of specialty).22 In the RCT, the most effective matching protocol was a combination of eliminating harm and matching the patient on their 3 most problematic domains (the highest match level). These patients ended care as healthy as the general population after 16 weeks of treatment. A random 1-year follow-up assessment from the original RCT showed that most patients who had been matched had maintained their improvement.23

Continue to: Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome...

Therefore, a multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool can be used to identify a BHP’s relative strengths and weaknesses across multiple outcome domains. Within a system of care, a sample of BHPs will possess varying outcome-domain profiles. When a new patient is seeking a referral to a BHP, these profiles (or domain-specific outcome track records) can be used to support paired-on outcome data matching. Specifically, a new patient completes the multidimensional routine outcome monitoring tool at pretreatment, and the results reveal the outcome domains on which the patient is most clinically severe. This pattern of domain-specific severity then can be used to pair the new patient with a BHP who has demonstrated success in addressing the same outcome domain(s). This approach matches a new patient to a BHP with established expertise based on routine outcome monitoring.

Retrospective and prospective studies have found that most BHPs have stable performance in their strengths and weaknesses.11,21 One study found that assessing BHP performance with their most recent 30 patients can reliably predict future performance with their next 30 patients.24 This predictability in a practitioner’s outcomes suggests report cards that are updated frequently can be utilized to make case assignments within BH or referrals to a specific BHP from primary care.

Making a paired-on outcome data–matched referral

Making customized BH referrals requires access to information about a practitioner’s previous routine outcome monitoring data per clinical domain (eg, suicidality, violence, quality of life) from their most recent patients. Previous research suggests that follow-up data from a minimum of 15 patients is necessary to make a reliable evaluation of a practitioner’s strengths and weaknesses (ie, effectiveness “report card”) per clinical domain.24

Few, if any, physicians have access to this level of updated outcome data from their referral network. To facilitate widespread use of paired-on outcome data matching, a new Web system (MatchedTherapists.com) will allow the general public and PCPs to access these grades. As a public service option, this site currently allows for a self-assessment using the Treatment Outcome Package. Pending versions will generate paired-on outcome data grades, and users will receive a list of local therapists available for in-person appointments as well as therapists available for virtual appointments. The paired-on outcome data grades are delivered in school-based letter grades. An “A+,” for example, represents the best matching grade. Users also will be able to sort and filter results for other criteria such as telemedicine, insurance, age, gender, and appointment availability. Currently, there are more than 77,000 therapists listed on the site nationwide. A basic listing is free.

CASE SCENARIO

After Ms. W took the multidimensional routine outcome assessment online, she received a list of therapists rank-ordered by paired-on outcome data grade, with the “A+” matches listed first. Three of the best-matched referrals accepted her insurance and were willing to see her through telemedicine. Therapists with available in-person appointments had a “B” grade. After discussing the options with her physician, Ms. W opted for telehealth counseling with the therapist whose profile she liked best. The therapist and PCP tracked her progress through routine outcome monitoring reporting until all her symptoms became subclinical.

Continue to: The future of a "referral bridge"

The future of a “referral bridge”

In this article, we present a solution to a common issue faced by mental health care patients: failure to benefit meaningfully from mental health treatment. Matching patients to specific BHPs based on effectiveness data regarding the therapist’s strengths and skills can improve patient outcomes and reduce harm. In addition, patients appear to value this approach. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation–funded study demonstrated that patients value seeing practitioners who have a track record of successfully treating previous patients with similar issues.25,26 In many cases, patients indicated they would prioritize this matching process over other factors such as practitioners with a higher number of years of experience or the same demographic characteristics as the patient.25,26

These findings may represent a new area in the science of health care. Over the past century, major advances in diagnosis and treatment—the 2 primary pillars of health care—have turned the art of medicine into a science. However, the art of making referrals has not advanced commensurately, as there has been little attention focused on the “referral bridge” between these 2 pillars. As the studies reviewed in this paper demonstrate, a referral bridge deserves exploration in all fields of medicine.

CORRESPONDENCE

David R. Kraus, PhD, 1 Speen Street, Framingham, MA 01701; [email protected]

1. HHS. 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Accessed March 29, 2023. www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2021-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

2. Barkham M, Lambert, MJ. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, eds. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: 50th Anniversary Edition. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021:135-189.

3. Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:324-335. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

4. de Jong K, Conijn JM, Gallagher RAV, et al. Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: a multilevel meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

5. Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, et al. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

6. Muir HJ, Coyne AE, Morrison NR, et al. Ethical implications of routine outcomes monitoring for patients, psychotherapists, and mental health care systems. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56:459-469. doi: 10.1037/pst0000246

7. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155-163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108

8. Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, et al. Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. Am Psychol. 2010;65:34-49. doi: 10.1037/a0017330

9. Kraus DR, Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, et al. Therapist effectiveness: implications for accountability and patient care. Psychother Res. 2011;21:267-276. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.563249

10. Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x

11. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Kraus DR, et al. The expanding relevance of routinely collected outcome data for mental health care decision making. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:482-491. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0649-6

12. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, et al. Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: results from a comprehensive review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:441-466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

13. Teymoori A, Gorbunova A, Haghish FE, et al. Factorial structure and validity of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scales after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med. 2020;9:873. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030873

14. Kraus DR, Seligman DA, Jordan JR. Validation of a behavioral health treatment outcome and assessment tool designed for naturalistic settings: the Treatment Outcome Package. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:285‐314. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20084

15. Boothroyd L, Dagnan D, Muncer S. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire using Mokken scaling and confirmatory factor analysis. Health Prim Care. 2018;2:1-4. doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000145

16. Locke BD, Buzolitz JS, Lei PW, et al. Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97-109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282

17. Kraus DR, Boswell JF, Wright AGC, et al. Factor structure of the treatment outcome package for children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:627-640. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20675

18. McAleavey AA, Nordberg SS, Kraus D, et al. Errors in treatment outcome monitoring: implications for real-world psychotherapy. Can Psychol. 2010;53:105-114. doi: 10.1037/a0027833

19. Baxter EE, Alexander PC, Kraus DR, et al. Concurrent validation of the Treatment Outcome Package (TOP) for children and adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:2415-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0419-4

20. Gual-Montolio P, Martínez-Borba V, Bretón-López JM, et al. How are information and communication technologies supporting routine outcome monitoring and measurement-based care in psychotherapy? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093170

21. Kraus DR, Bentley JH, Alexander PC, et al. Predicting therapist effectiveness from their own practice-based evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:473‐483. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000083

22. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Coyne AE, et al. Effect of matching therapists to patients vs assignment as usual on adult psychotherapy outcomes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:960-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1221

23. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Kraus DR, et al. Matching patients with therapists to improve mental health care. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/matching-patients-therapists-improve-mental-health-care

24. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. National Academies Press; 2006. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11470/chapter/1

25. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. A multimethod study of mental health care patients’ attitudes toward clinician-level performance information. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:452-456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000366

26. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. Mental health care consumers’ relative valuing of clinician performance information. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:301‐308. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000264

1. HHS. 2021 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Releases. Accessed March 29, 2023. www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2021-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases

2. Barkham M, Lambert, MJ. The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies. In: Barkham M, Lutz W, Castonguay LG, eds. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change: 50th Anniversary Edition. 7th ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2021:135-189.

3. Lewis CC, Boyd M, Puspitasari A, et al. Implementing measurement-based care in behavioral health: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:324-335. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3329

4. de Jong K, Conijn JM, Gallagher RAV, et al. Using progress feedback to improve outcomes and reduce drop-out, treatment duration, and deterioration: a multilevel meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;85:102002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102002

5. Carlier IVE, Meuldijk D, Van Vliet IM, et al. Routine outcome monitoring and feedback on physical or mental health status: evidence and theory. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:104-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01543.x

6. Muir HJ, Coyne AE, Morrison NR, et al. Ethical implications of routine outcomes monitoring for patients, psychotherapists, and mental health care systems. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2019;56:459-469. doi: 10.1037/pst0000246

7. Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155-163. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20108

8. Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, et al. Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. Am Psychol. 2010;65:34-49. doi: 10.1037/a0017330

9. Kraus DR, Castonguay LG, Boswell JF, et al. Therapist effectiveness: implications for accountability and patient care. Psychother Res. 2011;21:267-276. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.563249

10. Lilienfeld SO. Psychological treatments that cause harm. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:53-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00029.x

11. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Kraus DR, et al. The expanding relevance of routinely collected outcome data for mental health care decision making. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:482-491. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0649-6

12. Lyon AR, Lewis CC, Boyd MR, et al. Capabilities and characteristics of digital measurement feedback systems: results from a comprehensive review. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2016;43:441-466. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0719-4

13. Teymoori A, Gorbunova A, Haghish FE, et al. Factorial structure and validity of depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) scales after traumatic brain injury. J Clin Med. 2020;9:873. doi: 10.3390/jcm9030873

14. Kraus DR, Seligman DA, Jordan JR. Validation of a behavioral health treatment outcome and assessment tool designed for naturalistic settings: the Treatment Outcome Package. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:285‐314. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20084

15. Boothroyd L, Dagnan D, Muncer S. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire using Mokken scaling and confirmatory factor analysis. Health Prim Care. 2018;2:1-4. doi: 10.15761/HPC.1000145

16. Locke BD, Buzolitz JS, Lei PW, et al. Development of the Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-62 (CCAPS-62). J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:97-109. doi: 10.1037/a0021282

17. Kraus DR, Boswell JF, Wright AGC, et al. Factor structure of the treatment outcome package for children. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:627-640. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20675

18. McAleavey AA, Nordberg SS, Kraus D, et al. Errors in treatment outcome monitoring: implications for real-world psychotherapy. Can Psychol. 2010;53:105-114. doi: 10.1037/a0027833

19. Baxter EE, Alexander PC, Kraus DR, et al. Concurrent validation of the Treatment Outcome Package (TOP) for children and adolescents. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:2415-2422. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0419-4

20. Gual-Montolio P, Martínez-Borba V, Bretón-López JM, et al. How are information and communication technologies supporting routine outcome monitoring and measurement-based care in psychotherapy? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3170. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093170

21. Kraus DR, Bentley JH, Alexander PC, et al. Predicting therapist effectiveness from their own practice-based evidence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:473‐483. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000083

22. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Coyne AE, et al. Effect of matching therapists to patients vs assignment as usual on adult psychotherapy outcomes. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:960-969. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1221

23. Constantino MJ, Boswell JF, Kraus DR, et al. Matching patients with therapists to improve mental health care. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021. Accessed March 1, 2023. www.pcori.org/research-results/2015/matching-patients-therapists-improve-mental-health-care

24. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. National Academies Press; 2006. Accessed February 21, 2023. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11470/chapter/1

25. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. A multimethod study of mental health care patients’ attitudes toward clinician-level performance information. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:452-456. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000366

26. Boswell JF, Constantino MJ, Oswald JM, et al. Mental health care consumers’ relative valuing of clinician performance information. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86:301‐308. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000264

To prevent depression recurrence, interpersonal psychotherapy is a first-line treatment with long-term benefits

Major depressive disorder (MDD) frequently is recurrent, with new episodes causing substantial social and economic impairment1 and increasing the likelihood of future episodes.2 For this reason, contemporary psychiatric practitioners think of depression treatment as long-term and plan thoughtfully for maintenance therapy.

Recognizing the importance of engaging depressed individuals beyond the initial response,3 American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines conceptualize depression treatment as 3 phases:

• acute treatment, with the aim of remission (symptom removal)

• continuation treatment, with the aim of preventing relapse (symptom return)

• maintenance treatment, with the aim of preventing recurrence (new episodes).4

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) is an evidence-based psychosocial treatment that adheres to this model.5 As a time-limited, manual-driven6,7 approach, IPT focuses on interpersonal distresses as precipitating and perpetuating factors of depression.8

Acute IPT’s efficacy is well-established across >200 empirical studies—making it an evidence-based, first-line treatment for adult depression.4,9,10 Meta-analyses show that acute IPT is superior to placebo and no-treatment controls, and largely comparable to antidepressant medication and other active, first-line psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).11,12

Although this review, as well as the literature, focuses largely on adult outpatients with depression, evidence of IPT’s general efficacy exists for adolescents,13 chronically depressed patients,11 and depressed inpatients.14 This article presents a case study to describe the structure of IPT when used to treat depressed adults. We also present evidence of IPT’s acute and long-term efficacy in preventing depression recurrence and data to guide its use in practice.

CASE REPORT

‘Safe’ but depressed

Timothy, age 18, is a first-year college student who presents for outpatient psychotherapy to address recurrent depression. He reports general unhappiness, loss of interest in things, low energy, sleep problems, poor academic and work functioning, and low self-esteem. He experienced at least 3 similar depressive episodes while in high school.

The therapist’s diagnostic and interpersonal assessment suggests that Timothy’s depression is interpersonally driven. Timothy longs for relational intimacy but fears he will fail or burden people with his needs. He has difficulty gauging appropriate levels of enmeshment with others and either becomes overdependent or stays at a distance. This “safe” approach to relationships contributes to boredom, loneliness, and isolation. His recent transition to college away from home and the failure of a romantic relationship have compounded these experiences.

Interpersonal model of IPT

IPT conceptualizes depression as involving predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating biopsychosocial factors, including:

• underlying biological and social vulnerability, such as insecure attach ment (ie, tenuous and often negative views of self and others)

• current interpersonal life stressors

• inadequate social supports.15,16

For example, poor early attachment to caregivers can give rise to despair, isolation, and low mood. In turn, this can be exacerbated by poor social and communication skills that promote further rejection and withdrawal of social support and thus, intensified despair, isolation, and low mood. As in Timothy’s case, this vicious cycle underscores psychosocial stressors as a causal factor, maintaining factor, and result of depression. Specifically, IPT conceptualizes 4 main biopsychosocial problem domains:

• grief and loss

• interpersonal disputes

• role transitions

• interpersonal/communication deficits (often connected to isolation).

Working within 1 or 2 of the most salient problem domains, IPT centers on strategies for helping patients solve interpersonal problems based on the notion that modified relationships, revised interpersonal expectations, improved communications, and increased social support will lead to symptom reduction.15-17

Many techniques are utilized in IPT (Table 1) to help patients modify their interpersonal relationships as a mechanism for decreasing their distress. IPT is problem-focused, aiming to improve patients’ relationships by drawing on their assets and helping to build skills around shortcomings. Therefore, IPT focuses on observable interpersonal patterns, as opposed to latent personality dynamics.

CASE CONTINUED

Setting goals

When the clinical explains in the non-technical terms the data supporting IPT’s efficacy for depression, including with young adults, Timothy agrees to teeatment with acute IPT. The therapist behins with consciousness-raising techniques to help Timothy adopt the “sick role” by viewing depressing as an illness to be cured. Collaboratively, they establish treatment goals that fit the IPT formulation of depression— ie, revising current relationships and expectations of them, increasing social support, improving communication skills, and solving problems within 1 or 2 of the IPT problem domains.

For Timothy, the most pressing psychosocial problems seem to be interpersonal deficits and role transitions. He appears to be insecurely attached to others, which is a risk factor for poor facilitation of, and boundaries around, good relationships. A transition to a new and intimidating interpersonal context—living on a college campus—compounded his vulnerabilities and increased his depression.

Acute treatment. The acute phase of IPT is time-limited—often, 12 to 16 sessions with gradual tapering toward the end (akin to a continuation phase). The time limit’s purpose is to focus both patient and therapist on the specific goal of removing the acute “illness” of depression. The IPT clinician takes an interpersonal inventory to learn about the patient’s most important relationships and hones in on the IPT domain foci. Working collaboratively, the therapist might help the patient mourn a loss, reconstruct a narrative with a deceased loved one, consider ways to increase social contact, develop assertiveness, label feelings and needs, resolve an impasse with a significant other, and so forth.

The IPT therapist is an advocate for the patient and adopts an active stance laced with empathy and warmth. However, the therapist is more than unconditionally accepting as depression is viewed as a problem to be actively resolved.

CASE CONTINUED

Creating new patterns

The therapist uses various IPT strategies to work collaboratively with Timothy. She attempts to develop a strong working alliance by building interpersonal safety and trust— which take time with an insecurely attached patient. She tries to provide a new model for how close relationships can develop, while also focusing on current relationships. She and Timothy address his romantic desire for a coworker and work on developing realistic expectations and effective methods for conveying his interest.

When Timothy approaches his coworker, she does not reject him—as he expected— but wants to pursue friendship before possibly dating. The therapist then works with Timothy’s emotional reaction and explores ways to effectively convey his emotions to this young woman. Drawing on communication analysis and problem-solving strategies, Timothy is able to sustain this friendship—a shift from his typical retreat when relationships have not gone as hoped or expected.

Timothy develops confidence to take more risks in initiating social encounters and starts to confide in his roommates when he feels upset. After 3 months of treatment, his expanded social network and improved interpersonal skills result in decreased depression. When Timothy suggests termination, he and the therapist agree to end acute IPT but—given his history of depression—to continue maintenance sessions.

Limited data exist on variables that relate to IPT’s acute success or conditions under which it works best. Although process research lags behind acute IPT outcome research, some findings can help guide the IPT practitioner. For example, variables shown to predict outcomes of acute IPT for depression include a positive therapeutic alliance, therapist warmth, and psycho psychotherapist use of exploratory techniques (Table 2).