User login

Alzheimer's Pathology May Appear 20 Years Before Symptoms

BARCELONA – The pathologic changes of Alzheimer’s disease may begin as early as 20 years before the expected onset of disease, at least in people whose families carry a high-risk gene, preliminary data from a 6-year longitudinal study suggested.

These first findings from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) study, a 6-year, cross-sectional, longitudinal study indicate that the use of PET and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of beta-amyloid and tau protein may allow researchers to select enriched pools of subjects for the testing of potential drug treatments, and, someday, allow clinicians to target patients with incipient disease for preventive treatment, Dr. John Morris said at the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases.

"I have not yet had sufficient sample size or follow-up to predict this completely," said Dr. Morris, DIAN’s principal investigator. "However, I think there are data both from Europe and the U.S. showing that low beta-amyloid 42 [Abeta 42] and high tau in the cerebrospinal fluid together will reach a hazard ratio of 5.2 for becoming demented within 3-4 years. We are just beginning to get these same data for amyloid imaging and the hazard ratio is about the same."

Dr. Morris, professor of neurology at Washington University, St. Louis, said the DIAN study hopes to recruit 400 subjects who are the children of a parent with a known autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s gene. Currently, three of those genes are known: amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1, and presenilin 2. He expects that about half the group will carry one of the mutations, while the other half will be unaffected siblings, who will serve as controls. The study involves 10 research institutions in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.

Each participant will undergo genetic analysis and the same periodic assessments, including cognitive and clinical testing; brain imaging with Pittsburgh imaging compound B, which binds to Abeta 42 plaques; 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; MRI; and lumbar punctures to test levels of Abeta 42 and tau. If subjects die during the study, their brains will be autopsied.

"The goals are to try and determine when the pathologic process begins in asymptomatic mutation carriers," Dr. Morris said. "We know, based on the parent’s age of onset, approximately when these carriers will become symptomatic. We want to see the changes, the rates of these changes, and determine to what extent the changes resemble those seen in sporadic Alzheimer’s."

As of last fall, DIAN had collected 106 volunteers, Dr. Morris said. About 70% of those are asymptomatic carriers, with an average age of 37 years, although that varies from 19 to 56 years. The average age of parental onset of dementia symptoms is 47 years, "so we have these folks an average of 10 years before their expected age of onset."

The presenilin 1 mutation is the most common in the group, occurring in 75%; presenilin 2 is present in 10%, and the APP mutation, in 15%.

Comparing the carriers with the noncarriers, the study’s "very preliminary" data indicate that cognitive decline begins as early as 10 years before the expected onset of symptoms, while neuropathologic changes start up to 20 years before.

But scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) for noncarrier siblings of these volunteers "have remained very clearly at 30," which is a normal score, Dr. Morrison said. The noncarriers also had normal scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (pdf) sum of boxes (CDR-SOB), another test used to identify Alzheimer’s-related cognitive changes.

This was not the case "for carriers, in whom we begin to see declines in the MMSE and the CDR about 10 years before the expected age of onset," Dr. Morris said.

The cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers followed a similar pattern. A decrease in spinal fluid Abeta 42 suggests that the protein is aggregating somewhere else in the body – probably in the characteristic brain plaques. These changes could be seen in carriers 20 years before the expected age of onset. Tau protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of carriers begin to rise around 20 years before the onset of symptoms, "with a clear acceleration at the time they are changing from asymptomatic to symptomatic," he said.

However, noncarriers have stable levels of both proteins in the CSF at the same ages.

Imaging in the precuneus and caudate with Pittsburgh imaging compound B shows no Abeta 42 accumulation in noncarriers, but in carriers, the protein begins to appear in those regions about the same time that the CSF biomarkers start to change – 20 years before the expected appearance of symptomatic disease.

If these findings can be confirmed, they prove the existence of a long prodromal stage in subjects who are genetically destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease. This has several important applications in both drug research and potential treatment, Dr. Morris noted.

First, the neuropsychological testing scores currently in use, which define normal cognitive function, may be incorrect, because they could be based on cohorts that included individuals who had already experienced cognitive decline, but still fell within the "normal" range.

To illustrate this problem, Dr. Morris referred to the cognitive testing of two subjects. One began with cognitive functioning at the mean of normal, while the other began at 2 standard deviations above the mean. Over a period of years, the first person remained stable at the mean, while the second declined to the mean – showing that this subject was experiencing significant cognitive decline on an individual basis, while still being considered cognitively normal. The patient quickly developed mild cognitive impairment and then Alzheimer’s disease.

"This interferes with the ability to detect very early stages of symptomatic Alzheimer’s based on neuropsychological testing, because the test norms are contaminated by the inclusion of subjects who may have preclinical disease," Dr. Morris said.

Comparative testing or the report of a close companion could detect change in a high-functioning individual, but the majority of people never undergo neuropsychological testing unless a problem is suspected.

Biomarkers, on the other hand, appear to predict decline very objectively. "People [with altered biomarkers] should be considered the real treatment target so we are not focusing all of our efforts on curing people who already have the symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia, but rather on trying to prevent those symptoms from appearing," Dr. Morris said.

"I would hope I’m wrong about this, but I would say it’s possible that amyloid monotherapies used after the symptomatic stage has begun will not be effective," he said. "At the point when we can make the diagnosis, when symptoms begin, up to 60% of the neurons in layer 2 of the entorhinal cortex are already lost; we are treating a damaged brain. Ideally, we need to treat when the lesions are just beginning, when an intervention might be effective."

DIAN is funded by a multiple-year research grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Morris declared that he had received research grant funding from multiple drug companies.

BARCELONA – The pathologic changes of Alzheimer’s disease may begin as early as 20 years before the expected onset of disease, at least in people whose families carry a high-risk gene, preliminary data from a 6-year longitudinal study suggested.

These first findings from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) study, a 6-year, cross-sectional, longitudinal study indicate that the use of PET and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of beta-amyloid and tau protein may allow researchers to select enriched pools of subjects for the testing of potential drug treatments, and, someday, allow clinicians to target patients with incipient disease for preventive treatment, Dr. John Morris said at the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases.

"I have not yet had sufficient sample size or follow-up to predict this completely," said Dr. Morris, DIAN’s principal investigator. "However, I think there are data both from Europe and the U.S. showing that low beta-amyloid 42 [Abeta 42] and high tau in the cerebrospinal fluid together will reach a hazard ratio of 5.2 for becoming demented within 3-4 years. We are just beginning to get these same data for amyloid imaging and the hazard ratio is about the same."

Dr. Morris, professor of neurology at Washington University, St. Louis, said the DIAN study hopes to recruit 400 subjects who are the children of a parent with a known autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s gene. Currently, three of those genes are known: amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1, and presenilin 2. He expects that about half the group will carry one of the mutations, while the other half will be unaffected siblings, who will serve as controls. The study involves 10 research institutions in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.

Each participant will undergo genetic analysis and the same periodic assessments, including cognitive and clinical testing; brain imaging with Pittsburgh imaging compound B, which binds to Abeta 42 plaques; 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; MRI; and lumbar punctures to test levels of Abeta 42 and tau. If subjects die during the study, their brains will be autopsied.

"The goals are to try and determine when the pathologic process begins in asymptomatic mutation carriers," Dr. Morris said. "We know, based on the parent’s age of onset, approximately when these carriers will become symptomatic. We want to see the changes, the rates of these changes, and determine to what extent the changes resemble those seen in sporadic Alzheimer’s."

As of last fall, DIAN had collected 106 volunteers, Dr. Morris said. About 70% of those are asymptomatic carriers, with an average age of 37 years, although that varies from 19 to 56 years. The average age of parental onset of dementia symptoms is 47 years, "so we have these folks an average of 10 years before their expected age of onset."

The presenilin 1 mutation is the most common in the group, occurring in 75%; presenilin 2 is present in 10%, and the APP mutation, in 15%.

Comparing the carriers with the noncarriers, the study’s "very preliminary" data indicate that cognitive decline begins as early as 10 years before the expected onset of symptoms, while neuropathologic changes start up to 20 years before.

But scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) for noncarrier siblings of these volunteers "have remained very clearly at 30," which is a normal score, Dr. Morrison said. The noncarriers also had normal scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (pdf) sum of boxes (CDR-SOB), another test used to identify Alzheimer’s-related cognitive changes.

This was not the case "for carriers, in whom we begin to see declines in the MMSE and the CDR about 10 years before the expected age of onset," Dr. Morris said.

The cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers followed a similar pattern. A decrease in spinal fluid Abeta 42 suggests that the protein is aggregating somewhere else in the body – probably in the characteristic brain plaques. These changes could be seen in carriers 20 years before the expected age of onset. Tau protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of carriers begin to rise around 20 years before the onset of symptoms, "with a clear acceleration at the time they are changing from asymptomatic to symptomatic," he said.

However, noncarriers have stable levels of both proteins in the CSF at the same ages.

Imaging in the precuneus and caudate with Pittsburgh imaging compound B shows no Abeta 42 accumulation in noncarriers, but in carriers, the protein begins to appear in those regions about the same time that the CSF biomarkers start to change – 20 years before the expected appearance of symptomatic disease.

If these findings can be confirmed, they prove the existence of a long prodromal stage in subjects who are genetically destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease. This has several important applications in both drug research and potential treatment, Dr. Morris noted.

First, the neuropsychological testing scores currently in use, which define normal cognitive function, may be incorrect, because they could be based on cohorts that included individuals who had already experienced cognitive decline, but still fell within the "normal" range.

To illustrate this problem, Dr. Morris referred to the cognitive testing of two subjects. One began with cognitive functioning at the mean of normal, while the other began at 2 standard deviations above the mean. Over a period of years, the first person remained stable at the mean, while the second declined to the mean – showing that this subject was experiencing significant cognitive decline on an individual basis, while still being considered cognitively normal. The patient quickly developed mild cognitive impairment and then Alzheimer’s disease.

"This interferes with the ability to detect very early stages of symptomatic Alzheimer’s based on neuropsychological testing, because the test norms are contaminated by the inclusion of subjects who may have preclinical disease," Dr. Morris said.

Comparative testing or the report of a close companion could detect change in a high-functioning individual, but the majority of people never undergo neuropsychological testing unless a problem is suspected.

Biomarkers, on the other hand, appear to predict decline very objectively. "People [with altered biomarkers] should be considered the real treatment target so we are not focusing all of our efforts on curing people who already have the symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia, but rather on trying to prevent those symptoms from appearing," Dr. Morris said.

"I would hope I’m wrong about this, but I would say it’s possible that amyloid monotherapies used after the symptomatic stage has begun will not be effective," he said. "At the point when we can make the diagnosis, when symptoms begin, up to 60% of the neurons in layer 2 of the entorhinal cortex are already lost; we are treating a damaged brain. Ideally, we need to treat when the lesions are just beginning, when an intervention might be effective."

DIAN is funded by a multiple-year research grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Morris declared that he had received research grant funding from multiple drug companies.

BARCELONA – The pathologic changes of Alzheimer’s disease may begin as early as 20 years before the expected onset of disease, at least in people whose families carry a high-risk gene, preliminary data from a 6-year longitudinal study suggested.

These first findings from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) study, a 6-year, cross-sectional, longitudinal study indicate that the use of PET and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of beta-amyloid and tau protein may allow researchers to select enriched pools of subjects for the testing of potential drug treatments, and, someday, allow clinicians to target patients with incipient disease for preventive treatment, Dr. John Morris said at the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases.

"I have not yet had sufficient sample size or follow-up to predict this completely," said Dr. Morris, DIAN’s principal investigator. "However, I think there are data both from Europe and the U.S. showing that low beta-amyloid 42 [Abeta 42] and high tau in the cerebrospinal fluid together will reach a hazard ratio of 5.2 for becoming demented within 3-4 years. We are just beginning to get these same data for amyloid imaging and the hazard ratio is about the same."

Dr. Morris, professor of neurology at Washington University, St. Louis, said the DIAN study hopes to recruit 400 subjects who are the children of a parent with a known autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s gene. Currently, three of those genes are known: amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1, and presenilin 2. He expects that about half the group will carry one of the mutations, while the other half will be unaffected siblings, who will serve as controls. The study involves 10 research institutions in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.

Each participant will undergo genetic analysis and the same periodic assessments, including cognitive and clinical testing; brain imaging with Pittsburgh imaging compound B, which binds to Abeta 42 plaques; 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; MRI; and lumbar punctures to test levels of Abeta 42 and tau. If subjects die during the study, their brains will be autopsied.

"The goals are to try and determine when the pathologic process begins in asymptomatic mutation carriers," Dr. Morris said. "We know, based on the parent’s age of onset, approximately when these carriers will become symptomatic. We want to see the changes, the rates of these changes, and determine to what extent the changes resemble those seen in sporadic Alzheimer’s."

As of last fall, DIAN had collected 106 volunteers, Dr. Morris said. About 70% of those are asymptomatic carriers, with an average age of 37 years, although that varies from 19 to 56 years. The average age of parental onset of dementia symptoms is 47 years, "so we have these folks an average of 10 years before their expected age of onset."

The presenilin 1 mutation is the most common in the group, occurring in 75%; presenilin 2 is present in 10%, and the APP mutation, in 15%.

Comparing the carriers with the noncarriers, the study’s "very preliminary" data indicate that cognitive decline begins as early as 10 years before the expected onset of symptoms, while neuropathologic changes start up to 20 years before.

But scores on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) for noncarrier siblings of these volunteers "have remained very clearly at 30," which is a normal score, Dr. Morrison said. The noncarriers also had normal scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (pdf) sum of boxes (CDR-SOB), another test used to identify Alzheimer’s-related cognitive changes.

This was not the case "for carriers, in whom we begin to see declines in the MMSE and the CDR about 10 years before the expected age of onset," Dr. Morris said.

The cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers followed a similar pattern. A decrease in spinal fluid Abeta 42 suggests that the protein is aggregating somewhere else in the body – probably in the characteristic brain plaques. These changes could be seen in carriers 20 years before the expected age of onset. Tau protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of carriers begin to rise around 20 years before the onset of symptoms, "with a clear acceleration at the time they are changing from asymptomatic to symptomatic," he said.

However, noncarriers have stable levels of both proteins in the CSF at the same ages.

Imaging in the precuneus and caudate with Pittsburgh imaging compound B shows no Abeta 42 accumulation in noncarriers, but in carriers, the protein begins to appear in those regions about the same time that the CSF biomarkers start to change – 20 years before the expected appearance of symptomatic disease.

If these findings can be confirmed, they prove the existence of a long prodromal stage in subjects who are genetically destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease. This has several important applications in both drug research and potential treatment, Dr. Morris noted.

First, the neuropsychological testing scores currently in use, which define normal cognitive function, may be incorrect, because they could be based on cohorts that included individuals who had already experienced cognitive decline, but still fell within the "normal" range.

To illustrate this problem, Dr. Morris referred to the cognitive testing of two subjects. One began with cognitive functioning at the mean of normal, while the other began at 2 standard deviations above the mean. Over a period of years, the first person remained stable at the mean, while the second declined to the mean – showing that this subject was experiencing significant cognitive decline on an individual basis, while still being considered cognitively normal. The patient quickly developed mild cognitive impairment and then Alzheimer’s disease.

"This interferes with the ability to detect very early stages of symptomatic Alzheimer’s based on neuropsychological testing, because the test norms are contaminated by the inclusion of subjects who may have preclinical disease," Dr. Morris said.

Comparative testing or the report of a close companion could detect change in a high-functioning individual, but the majority of people never undergo neuropsychological testing unless a problem is suspected.

Biomarkers, on the other hand, appear to predict decline very objectively. "People [with altered biomarkers] should be considered the real treatment target so we are not focusing all of our efforts on curing people who already have the symptoms of Alzheimer’s dementia, but rather on trying to prevent those symptoms from appearing," Dr. Morris said.

"I would hope I’m wrong about this, but I would say it’s possible that amyloid monotherapies used after the symptomatic stage has begun will not be effective," he said. "At the point when we can make the diagnosis, when symptoms begin, up to 60% of the neurons in layer 2 of the entorhinal cortex are already lost; we are treating a damaged brain. Ideally, we need to treat when the lesions are just beginning, when an intervention might be effective."

DIAN is funded by a multiple-year research grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Morris declared that he had received research grant funding from multiple drug companies.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ALZHEIMER'S AND PARKINSON'S DISEASES

Major Finding: Carriers of autosomal-dominant mutations for Alzheimer’s disease show signs of cognitive decline 10 years before the expected age of onset and changes in levels of beta-amyloid and tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid 20 years before.

Data Source: Preliminary data from 106 children of a parent with a proven autosomal-dominant gene for Alzheimer’s disease in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN).

Disclosures: DIAN is funded by a multiple-year research grant from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Morris declared that he had received research grant funding from multiple drug companies.

Stroke Survivors Likely to Develop Medical Comorbidities

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

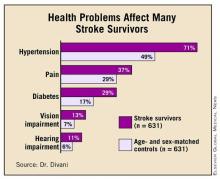

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Stroke survivors had significantly greater odds for developing memory deficit (OR, 2.4), urinary incontinence (OR, 1.64), and motor impairment (OR, 1.45) than did age- and sex-matched controls.

Data Source: Case-control study of participants in the national Health and Retirement Study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

Stroke Survivors Likely to Develop Medical Comorbidities

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Stroke survivors had significantly greater odds for developing memory deficit (OR, 2.4), urinary incontinence (OR, 1.64), and motor impairment (OR, 1.45) than did age- and sex-matched controls.

Data Source: Case-control study of participants in the national Health and Retirement Study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

Stroke Survivors Likely to Develop Medical Comorbidities

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Stroke survivors are at a significantly increased risk of developing health problems that can impact their daily life even if they have experienced only a single stroke and are still living in the community, according to an analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.

Stroke survivors are significantly more likely to fall and to have memory and motor impairment, urinary incontinence, and some sleep disturbance after having a stroke, compared with age-matched controls, Afshin Divani, Ph.D., reported at the International Stroke Conference.

"Physicians, caregivers, and rehabilitation providers need to pay particular attention to these comorbid conditions," particularly in light of the aging population and increased number of stroke survivors, said Dr. Divani, director of stroke research at the University of Minnesota Medical Center in Fairview.

The Health and Retirement Study, launched in 1992, is a national representative sample of community-living adults aged 50 years and older. It examines economic circumstances, health, and marital and family status using a questionnaire delivered every other year. Beginning in 1998, the survey was expanded to include questions directed at specific subgroups, including stroke survivors. Questions about stroke are administered only to participants who are at least 65 years old.

Dr. Divani and his colleagues used the database to conduct a longitudinal study of health problems in stroke survivors. "We collected information on 631 stroke subjects who were noninstitutionalized. We excluded anyone who was institutionalized in the next interview wave, as well as those who had experienced multiple strokes."

The team collected demographic information, as well as data on living arrangements, physician-diagnosed disorders (diabetes, cancer, lung disease, psychiatric disorders, and neurologic/sensory disorders); general health; and health problems (pain, incontinence, sleep, falls, and fall-related injury).

They compared data from stroke survivors with data from an age- and sex-matched control cohort of 631 survey participants.

The subjects’ mean age was 75 years; 53% were female. Self-reported general health was significantly lower in stroke survivors, with 22% reporting poor health, compared with 7% of controls. Similarly, 34% of survivors reported fair health, compared with 21% of controls. But only 2% of stroke survivors reported excellent health, compared with 9% of controls. Health was rated as very good by 12% of stroke survivors and 28% of controls.

Diabetes, pain, hypertension, and vision and hearing impairment were all significantly more common among stroke survivors. (See box.) Significantly more survivors (15% vs. 6%) also needed a proxy respondent to complete the interview. "This suggests that stroke survivors were unable to answer questions, hold the phone, or participate in a face-to-face interview," Dr. Divani said.

For the longitudinal study, the investigators tried to pinpoint when the health problem occurred – a difficult task, because only the stroke questions involved a time stamp. "We looked at subsequent interview waves and went back to see if the respondents already had those problems before the stroke, and if they did, we excluded them from the study," Dr. Divani said.

In the longitudinal analysis, motor impairment was significantly more common among stroke survivors (33% vs. 24%), as was urinary incontinence (19% vs. 11%).

Among the four dimensions of sleep quality that the investigators assessed (trouble falling asleep, waking up at night, waking early, and not feeling rested), only one – not feeling rested – was significantly more common among survivors (33% vs. 22%). Falling and fall-related injuries were also significantly more common.

There also was a significant association between stroke and memory deficit, occurring in 9% of survivors and 3% of nonstroke subjects.

The investigators then conducted a multivariate analysis to determine which problems were significantly more likely to develop after a stroke. The strongest risk was for memory deficit (odds ratio, 2.4). Survivors also had 64% greater odds of having urinary incontinence and 45% greater odds of having motor impairment than did controls. In the area of sleep quality, survivors had 59% greater odds of not feeling rested, although there were no significant risks associated with the other aspects of sleep.

All aspects of falls and fall-related injuries became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis, Dr. Divani noted. "This may be because fear of falling makes them more careful, and having a motor deficit prevents them from doing a complex task like climbing stairs," so if a fall occurs, it’s more likely to be while walking on a flat surface, and not from an elevated location. "A stair fall has a much higher risk of injury than someone falling while walking."

Although the data paint a good initial picture of poststroke health issues, Dr. Divani cautioned that it probably underestimates the true impact. "I need to emphasize that we selected noninstitutionalized subjects who had only one stroke," he said. "We selected the most healthy stroke survivors, which means we are probably underestimating the true problems among stroke patients."

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Stroke survivors had significantly greater odds for developing memory deficit (OR, 2.4), urinary incontinence (OR, 1.64), and motor impairment (OR, 1.45) than did age- and sex-matched controls.

Data Source: Case-control study of participants in the national Health and Retirement Study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Kessler Foundation, and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. Dr. Divani had no financial disclosures.

Report Links Midlife Hypertension to Late-Life Cortical Thinning

BARCELONA – Uncontrolled hypertension at midlife may be related to continuous cortical thinning, a condition which has been shown to be associated with dementia in old age.

"We suggest that midlife hypertension is associated with cortical thinning in areas related to blood pressure regulation, and dementia," Miika Vuorinen and his colleagues wrote in a poster presented March 10 at the International conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease.

"To our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on the effects of midlife hypertension on these multiple brain regions in later life," wrote Mr. Vuorinen, a doctoral student at the University of Finland, Kuopio.

The study yielded some interesting observations that await further clarification in other populations before additional interpretations can be made, said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, who was not involved in the study.

"The general relationship of cerebrovascular risk factors with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] is an area of great interest, but also some controversy, as not all studies agree with each other. In the current case, for example, some factors like hypercholesterolemia and obesity, that others have found to correlate with AD risk did not correlate with cortical thinning," said Dr. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging, and Incidence of Dementia study (CAIDE) comprises 1,449 residents of eastern Finland who were first evaluated at midlife, in 1972, 1977, 1982, or 1987. Now, with up to 30 years of follow-up, researchers are evaluating how midlife blood pressure, body mass index, cholesterol levels, smoking, and physical activity might relate to late-life brain health.

This substudy included all subjects suspected of having mild cognitive impairment at their 2005-2008 visit. All (mean age 78 years) underwent magnetic resonance imaging. Of these, 63 had images sufficient to measure cortical thickness in 10 brain areas related to cognition and blood pressure regulation: the bilateral hemispheric anterior insulae cortices, bilateral orbitofrontal cortices, and bilateral posterior superior medal temporal gyri and the left intraparietal sulcus. Measurements of the right hemisphere involved only the temporal pole, entorhinal cortex, and inferior frontal gyrus.

The researchers compared participants with midlife hypertension (blood pressure of more than 160/95 mmHg) against normotensive subjects. Elevated midlife blood pressure was associated with cortical thinning in all of the brain regions measured. The right hemisphere of the brain showed more thinning overall than did the left, and the insular cortices and orbitofrontal areas were bilaterally affected, the investigators noted.

None of the associations changed in a multivariate analysis that controlled for age, gender, late-life antihypertensive medications, follow-up time, or the type of scanner used in the imaging.

"In a further analysis, systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure showed linear relationships with decreasing cortical thickness in the right insular cortex," the investigators added.

Decreasing blood pressure in late life was also related to decreased cortical thickness, supporting previous findings that patients who develop dementia may also experience decreasing blood pressure, the investigators noted.

Dr. Caselli cautioned that subgroup analyses "get tricky and risk bias," and wondered "why should the insular cortex specifically show such a strong effect?" Even though it is interesting, is it "coincidence or is it meaningful?" he asked.

"Cortical thinning can certainly relate to Alzheimer’s disease, but it may also relate to cerebrovascular disease, so the correlation, while of interest, need not be exclusively related to Alzheimer’s disease."

He added that the investigators did not mention apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype, but "some studies have shown that CV risk factors have a greater impact on [APOE e4 allele] carriers than [do] noncarriers, at least as regards AD-related outcomes."

The same group of investigators recently published another CAIDE substudy, which found significant associations between increased white matter lesions in late life with mid- and late-life vascular risk factors (Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2011;31:119-25).

This substudy comprised 112 CAIDE participants with an average follow-up of 21 years. The subjects underwent MRI scanning and were assessed for white matter lesions. White matter lesions were significantly associated with other CAIDE risk factors, including being overweight at mid-life (relative risk 2.5); obesity (RR 2.9); and hypertension (RR 2.7); the associations remained significant after adjusting for several factors.

This study found a similar late-life blood pressure association: subjects with mid-life, but not late-life, hypertension (RR 3.25). This association remained significant even after controlling for antihypertensive medication at mid-life. The use of lipid-lowering drugs reduced the risk of late-life white matter lesions by 87%, the authors noted.

"These results indicate that early and sustained vascular risk factor control is associated with a lower likelihood of having more severe white matter lesions in late life," they wrote.

The group noted no potential conflicts of interest in either study. The CAIDE study is sponsored by grants from the university and various Swedish and Finnish government grants.