User login

Update in Hospital Palliative Care

Seriously ill patients frequently receive care in hospitals,[1, 2, 3] and palliative care is a core competency for hospitalists.[4, 5] The goal of this update was to summarize and critique recently published research that has the highest potential to impact the clinical practice of palliative care in the hospital. We reviewed articles published between January 2012 and May 2013. To identify articles, we hand‐searched 22 leading journals (see Appendix) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and performed a PubMed keyword search using the terms hospice and palliative care. We evaluated identified articles based on scientific rigor and relevance to hospital practice. In this review, we summarize 9 articles that were collectively selected as having the highest impact on the clinical practice of hospital palliative care. We summarize each article and its findings and note cautions and implications for practice.

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

Indwelling Pleural Catheters and Talc Pleurodesis Provide Similar Dyspnea Relief in Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusions

Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion. JAMA. 2012;307:23832389.

Background

Expert guidelines recommend chest‐tube insertion and talc pleurodesis as a first‐line therapy for symptomatic malignant pleural effusions, but indwelling pleural catheters are gaining in popularity.[6] The optimal management is unknown.

Findings

A total of 106 patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic malignant pleural effusion were randomized to undergo talc pleurodesis or placement of an indwelling pleural catheter. Most patients had metastatic breast or lung cancer. Overall, there were no differences in relief of dyspnea at 42 days between patients who received indwelling catheters and pleurodesis; importantly, more than 75% of patients in both groups reported improved shortness of breath. The initial hospitalization was much shorter in the indwelling catheter group (0 days vs 4 days). There was no difference in quality of life, but in surviving patients, dyspnea at 6 months was better with the indwelling catheter. In the talc group, 22% of patients required further pleural procedures compared with 6% in the indwelling catheter group. Patients in the talc group had a higher frequency of adverse events than in the catheter group (40% vs 13%). In the catheter group, the most common adverse events were pleural infection, cellulitis, and catheter obstruction.

Cautions

The study was small and unblinded, and the primary outcome was subjective dyspnea. The study occurred at 7 hospitals, and the impact of institutional or provider experience was not taken into account. Last, overall costs of care, which could impact the choice of intervention, were not calculated.

Implications

This was a small but well‐done study showing that indwelling catheters and talc pleurodesis provide similar relief of dyspnea 42 days postintervention. Given these results, both interventions seem to be acceptable options. Clinicians and patients could select the best option based on local procedural expertise and patient factors such as preference, ability to manage a catheter, and life expectancy.

Most Dying Patients Do Not Experience Increased Respiratory Distress When Oxygen is Withdrawn

Campbell ML, Yarandi H, Dove‐Medows E. Oxygen is nonbeneficial for most patients who are near death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):517523.

Background

Oxygen is frequently administered to patients at the end of life, yet there is limited evidence evaluating whether oxygen reduces respiratory distress in dying patients.

Findings

In this double‐blind, repeated‐measure study, patients served as their own controls as the investigators evaluated respiratory distress with and without oxygen therapy. The study included 32 patients who were enrolled in hospice or seen in palliative care consultation and had a diagnosis such as lung cancer or heart failure that might cause dyspnea. Medical air (nasal cannula with air flow), supplemental oxygen, and no flow were randomly alternated every 10 minutes for 1 hour. Blinded research assistants used a validated observation scale to compare respiratory distress under each condition. At baseline, 27 of 32 (84%) patients were on oxygen. Three patients, all of whom were conscious and on oxygen at baseline, experienced increased respiratory distress without oxygen; reapplication of supplemental oxygen relieved their distress. The other 29 patients had no change in respiratory distress under the oxygen, medical air, and no flow conditions.

Cautions

All patients in this study were near death as measured by the Palliative Performance Scale, which assesses prognosis based on functional status and level of consciousness. Patients were excluded if they were receiving high‐flow oxygen by face mask or were experiencing respiratory distress at the time of initial evaluation. Some patients experienced increased discomfort after withdrawal of oxygen. Close observation is needed to determine which patients will experience distress.

Implications

The majority of patients who were receiving oxygen at baseline experienced no change in respiratory comfort when oxygen was withdrawn, supporting previous evidence that oxygen provides little benefit in nonhypoxemic patients. Oxygen may be an unnecessary intervention near death and has the potential to add to discomfort through nasal dryness and decreased mobility.

Sennosides Performed Similarly to Docusate Plus Sennosides in Managing Opioid‐Induced Constipation in Seriously Ill Patients

Tarumi Y, Wilson MP, Szafran O, Spooner GR. Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:213.

Background

Seriously ill patients frequently suffer from constipation, often as a result of opioid analgesics. Hospital clinicians should seek to optimize bowel regimens to prevent opioid‐induced constipation. A combination of the stimulant laxative sennoside and the stool softener docusate is often recommended to treat and prevent constipation. Docusate may not have additional benefit to sennoside, and may have significant burdens, including disturbing the absorption of other medications, adding to patients' pill burden and increasing nurse workload.[7]

Findings

In this double‐blinded trial, 74 patients in 3 inpatient hospices in Canada were randomized to receive sennoside plus either docusate 100 mg, or placebo tablets twice daily, or sennoside plus placebo for 10 days. Most patients had cancer as a life‐limiting diagnosis and received opioids during the study period. All were able to tolerate pills and food or sips of fluid. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in stool frequency, volume, consistency, or patients' perceptions of difficulty with defecation. The percentage of patients who had a bowel movement at least every 3 days was 71% in the docusate plus sennoside group and 81% in the sennoside only group (P=0.45). There was also no significant difference between the groups in sennoside dose (which ranged between 13, 8.6 mg tablets daily), mean morphine equivalent daily dosage, or other bowel interventions.

Cautions

The trial was small, though it was adequately powered to detect a clinically meaningful difference between the 2 groups of 0.5 in the average number of bowel movements per day. The consent rate was low (26%); the authors do not detail reasons patients were not randomized. Patients who did not participate might have had different responses.

Implications

Consistent with previous work,[7] these results indicate that docusate is probably not needed for routine management of opioid‐induced constipation in seriously ill patients.

Sublingual Atropine Performed Similarly to Placebo in Reducing Noise Associated With Respiratory Rattle Near Death

Heisler M, Hamilton G, Abbott A, et al. Randomized double‐blind trial of sublingual atropine vs. placebo for the management of death rattle. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;45(1):1422.

Background

Increased respiratory tract secretions in patients near death can cause noisy breathing, often referred to as a death rattle. Antimuscarinic medications, such as atropine, are frequently used to decrease audible respirations and family distress, though little evidence exists to support this practice.

Findings

In this double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group trial at 3 inpatient hospices, 177 terminally ill patients with audible respiratory secretions were randomized to 2 drops of sublingual atropine 1% solution or placebo drops. Bedside nurses rated patients' respiratory secretions at enrollment, and 2 and 4 hours after receiving atropine or placebo. There were no differences in noise score between subjects treated with atropine and placebo at 2 hours (37.8% vs. 41.3%, P=0.24) or at 4 hours (39.7% and 51.7%, P=0.21). There were no differences in the safety end point of change in heart rate (P=0.47).

Cautions

Previous studies comparing different anticholinergic medications and routes of administration to manage audible respiratory secretions had variable response rates but suggested a benefit to antimuscarinic medications. However, these trials had significant methodological limitations including lack of randomization and blinding. The improvement in death rattle over time in other studies may suggest a favorable natural course for respiratory secretions rather than a treatment effect.

Implications

Although generalizability to other antimuscarinic medications and routes of administration is limited, in a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, sublingual atropine did not reduce the noise from respiratory secretions when compared to placebo.

PATIENT AND FAMILY OUTCOMES AFTER CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION

Over Half of Older Adult Survivors of In‐Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Were Alive At 1 Year

Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA, et al. Long‐term outcomes in elderly survivors of in‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:10191026.

Background

Studies of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes have focused on survival to hospital discharge. Little is known about long‐term outcomes following in‐hospital cardiac arrest in older adults.

Findings

The authors analyzed data from the Get With the GuidelinesResuscitation registry from 2000 to 2008 and Medicare inpatient files from 2000 to 2010. The cohort included 6972 patients at 401 hospitals who were discharged after surviving in‐hospital arrest. Outcomes were survival and freedom from hospital readmission at 1 year after discharge. At discharge, 48% of patients had either no or mild neurologic disability at discharge; the remainder had moderate to severe neurologic disability. Overall, 58% of patients who were discharged were still alive at 1 year. Survival rates were lowest for patients who were discharged in coma or vegetative state (8% at 1 year), and highest for those discharged with mild or no disability (73% at 1 year). Older patients had lower survival rates than younger patients, as did men compared with women and blacks compared with whites. At 1 year, 34.4% of the patients had not been readmitted. Predictors of readmission were similar to those for lower survival rates.

Cautions

This study only analyzed survival data from patients who survived to hospital discharge after receiving in‐hospital CPR, not all patients who had a cardiac arrest. Thus, the survival rates reported here do not include patients who died during the original arrest, or who survived the arrest but died during their hospitalization. The 1‐year survival rate for people aged 65 years and above following a cardiac arrest is not reported but is likely to be about 10%, based on data from this registry.[8] Data were not available for health status, neurologic status, or quality of life of the survivors at 1 year.

Implications

Older patients who receive in‐hospital CPR and have a good neurologic status at hospital discharge have good long‐term outcomes. In counseling patients about CPR, it is important to note that most patients who receive CPR do not survive to hospital discharge.

Families Who Were Present During CPR Had Decreased Post‐traumatic Stress Symptoms

Jabre P, Belpomme V, Azoulay E, et al. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:10081018.

Background

Family members who watch their loved ones undergo (CPR) might have increased emotional distress. Alternatively, observing CPR may allow for appreciation of the efforts taken for their loved one and provide comfort at a challenging time. The right balance of benefit and harm is unclear.

Findings

Between 2009 and 2011, 15 prehospital emergency medical service units in France were randomized to offer adult family members the opportunity to observe CPR or follow their usual practice. A total of 570 relatives were enrolled. In the intervention group, 79% of relatives observed CPR, compared to 43% in the control group. There was no difference in the effectiveness of CPR between the 2 groups. At 90 days, post‐traumatic stress symptoms were more common in the control group (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2‐2.5). At 90 days, those who were present for the resuscitation also had fewer symptoms of anxiety and fewer symptoms of depression (P0.009 for both). Stress of the medical teams involved in the CPR was not different between the 2 groups. No malpractice claims were filed in either group.

Cautions

The study was conducted only in France, so the results may not be generalizable outside of France. In addition, the observed resuscitation was for patients who suffered a cardiac arrest in the home; it is unclear if the same results would be found in the emergency department or hospital.

Implications

This is the highest quality study to date in this area that argues for actively inviting family members to be present for resuscitation efforts in the home. Further studies are needed to determine if hospitals should implement standard protocols. In the meantime, providers who perform CPR should consider inviting families to observe, as it may result in less emotional distress for family members.

COMMUNICATION AND DECISION MAKING

Surrogate Decision Makers Interpreted Prognostic Information Optimistically

Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, et al. Surrogate decision makers' interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed‐methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:360366.

Background

Surrogates of critically ill patients often have beliefs about prognosis that are discordant from what is told to them by providers. Little is known about why this is the case.

Findings

Eighty surrogates of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) were given questionnaires with hypothetical prognostic statements and asked to identify a survival probability associated with each statement on a 0% to 100% scale. Interviewers examined the questionnaires to identify responses that were not concordant with the given prognostic statements. They then interviewed participants to determine why the answers were discordant. The researchers found that surrogates were more likely to offer an overoptimistic interpretation of statements communicating a high risk of death, compared to statements communicating a low risk of death. The qualitative interviews revealed that surrogates felt they needed to express ongoing optimism and that patient factors not known to the medical team would lead to better outcomes.

Cautions

The participants were surrogates who were present in the ICU at the time when study investigators were there, and thus the results may not be generalizable to all surrogates. Only a subset of participants completed qualitative interviews. Prognostic statements were hypothetical. Written prognostic statements may be interpreted differently than spoken statements.

Implications

Surrogate decision makers may interpret prognostic statements optimistically, especially when a high risk of death is estimated. Inaccurate interpretation may be related to personal beliefs about the patients' strengths and a need to hold onto hope for a positive outcome. When communicating with surrogates of critically ill patients, providers should be aware that, beyond the actual information shared, many other factors influence surrogates' beliefs about prognosis.

A Majority of Patients With Metastatic Cancer Felt That Chemotherapy Might Cure Their Disease

Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Chronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:16161625.

Background

Chemotherapy for advanced cancer is not curative, and many cancer patients overestimate their prognosis. Little is known about patients' understanding of the goals of chemotherapy when cancer is advanced.

Findings

Participants were part of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance study. Patients with stage IV lung or colon cancer who opted to receive chemotherapy (n=1193) were asked how likely they thought it was that the chemotherapy would cure their cancer. A majority (69% of lung cancer patients and 81% of colon cancer patients) felt that chemotherapy might cure their disease. Those who rated their physicians very favorably in satisfaction surveys were more likely to feel that that chemotherapy might be curative, compared to those who rated their physician less favorably (OR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.33‐2.72).

Cautions

The study did not include patients who died soon after diagnosis and thus does not provide information about those who opted for chemotherapy but did not survive to the interview. It is possible that responses were influenced by participants' need to express optimism (social desirability bias). It is not clear how or whether prognostic disclosure by physicians caused the lower satisfaction ratings.

Implications

Despite the fact that stage IV lung and colon cancer are not curable with chemotherapy, a majority of patients reported believing that chemotherapy might cure their disease. Hospital clinicians should be aware that many patients who they view as terminally ill believe their illness may be cured.

Older Patients Who Viewed a Goals‐of‐Care Video at Admission to a Skilled Nursing Facility Were More Likely to Prefer Comfort Care

Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals‐of‐care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:805811.

Background

Seriously ill older patients are frequently discharged from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). It is important to clarify and document patients' goals for care at the time of admission to SNFs, to ensure that care provided there is consistent with patients' preferences. Previous work has shown promise using videos to assist patients in advance‐care planning, providing realistic and standardized portrayals of different treatment options.[9, 10]

Findings

English‐speaking patients at least 65 years of age who did not have altered mental status were randomized to hear a verbal description (n=51) or view a 6‐minute video (n=50) that presented the same information accompanied by pictures of patients of 3 possible goals of medical care: life‐prolonging care, limited medical care, and comfort care. After the video or narrative, patients were asked what their care preference would be if they became more ill while at the SNF. Patients who viewed the video were more likely to report a preference for comfort care, compared to patients who received the narrative, 80% vs 57%, P=0.02. In a review of medical records, only 31% of patients who reported a preference for comfort care had a do not resuscitate order at the SNF.

Cautions

The study was conducted at 2 nursing homes located in the Boston, Massachusetts area, which may limit generalizability. Assessors were not blinded to whether the patient saw the video or received the narrative, which may have introduced bias. The authors note that the video aimed to present the different care options without valuing one over the other, though it may have inadvertently presented one option in a more favorable light.

Implications

Videos may be powerful tools for helping nursing home patients to clarify goals of care, and might be applied in the hospital setting prior to transferring patients to nursing homes. There is a significant opportunity to improve concordance of care with preferences through better documentation and implementation of code status orders when transferring patients to SNFs.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Drs. Anderson and Johnson and Mr. Horton received an honorarium and support for travel to present findings resulting from the literature review at the Annual Assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association on March 16, 2013 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Dr. Anderson was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF‐CTSI grant number KL2TR000143. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Journals That Were Hand Searched to Identify Articles, By Topic Area

General:

- British Medical Journal

- Journal of the American Medical Association

- Lancet

- New England Journal of Medicine

Internal medicine:

- Annals Internal Medicine

- Archives Internal Medicine

- Journal of General Internal Medicine

- Journal of Hospital Medicine

Palliative care and symptom management:

- Journal Pain and Symptom Management

- Journal of Palliative Care

- Journal of Palliative Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Pain

Oncology:

- Journal of Clinical Oncology

- Supportive Care in Cancer

Critical care:

- American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

- Critical Care Medicine

Pediatrics:

- Pediatrics

Geriatrics:

- Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

Education:

- Academic Medicine

Nursing:

- Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing

- Oncology Nursing Forum

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Percent of Medicare decedents hospitalized at least once during the last six months of life 2007. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=133. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- , , , et al. Change in end‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309(5):470–477.

- , , , et al. End‐of‐life care for lung cancer patients in the United States and Ontario. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(11):853–862.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(suppl 1):48–56.

- Society of Hospital Medicine; 2008.The core competencies in hospital medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- , , , , . Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline. Thorax. 2010;65:ii32–ii40.

- , . A comparison of sennosides‐based bowel protocols with and without docusate in hospitalized patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(4):575–581.

- , , , , , . Trends in survival after In‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1912–1920.

- , , , et al. Use of video to facilitate end‐of‐life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305–310.

- , , , et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention‐postintervention study. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4331–4338.

Seriously ill patients frequently receive care in hospitals,[1, 2, 3] and palliative care is a core competency for hospitalists.[4, 5] The goal of this update was to summarize and critique recently published research that has the highest potential to impact the clinical practice of palliative care in the hospital. We reviewed articles published between January 2012 and May 2013. To identify articles, we hand‐searched 22 leading journals (see Appendix) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and performed a PubMed keyword search using the terms hospice and palliative care. We evaluated identified articles based on scientific rigor and relevance to hospital practice. In this review, we summarize 9 articles that were collectively selected as having the highest impact on the clinical practice of hospital palliative care. We summarize each article and its findings and note cautions and implications for practice.

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

Indwelling Pleural Catheters and Talc Pleurodesis Provide Similar Dyspnea Relief in Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusions

Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion. JAMA. 2012;307:23832389.

Background

Expert guidelines recommend chest‐tube insertion and talc pleurodesis as a first‐line therapy for symptomatic malignant pleural effusions, but indwelling pleural catheters are gaining in popularity.[6] The optimal management is unknown.

Findings

A total of 106 patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic malignant pleural effusion were randomized to undergo talc pleurodesis or placement of an indwelling pleural catheter. Most patients had metastatic breast or lung cancer. Overall, there were no differences in relief of dyspnea at 42 days between patients who received indwelling catheters and pleurodesis; importantly, more than 75% of patients in both groups reported improved shortness of breath. The initial hospitalization was much shorter in the indwelling catheter group (0 days vs 4 days). There was no difference in quality of life, but in surviving patients, dyspnea at 6 months was better with the indwelling catheter. In the talc group, 22% of patients required further pleural procedures compared with 6% in the indwelling catheter group. Patients in the talc group had a higher frequency of adverse events than in the catheter group (40% vs 13%). In the catheter group, the most common adverse events were pleural infection, cellulitis, and catheter obstruction.

Cautions

The study was small and unblinded, and the primary outcome was subjective dyspnea. The study occurred at 7 hospitals, and the impact of institutional or provider experience was not taken into account. Last, overall costs of care, which could impact the choice of intervention, were not calculated.

Implications

This was a small but well‐done study showing that indwelling catheters and talc pleurodesis provide similar relief of dyspnea 42 days postintervention. Given these results, both interventions seem to be acceptable options. Clinicians and patients could select the best option based on local procedural expertise and patient factors such as preference, ability to manage a catheter, and life expectancy.

Most Dying Patients Do Not Experience Increased Respiratory Distress When Oxygen is Withdrawn

Campbell ML, Yarandi H, Dove‐Medows E. Oxygen is nonbeneficial for most patients who are near death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):517523.

Background

Oxygen is frequently administered to patients at the end of life, yet there is limited evidence evaluating whether oxygen reduces respiratory distress in dying patients.

Findings

In this double‐blind, repeated‐measure study, patients served as their own controls as the investigators evaluated respiratory distress with and without oxygen therapy. The study included 32 patients who were enrolled in hospice or seen in palliative care consultation and had a diagnosis such as lung cancer or heart failure that might cause dyspnea. Medical air (nasal cannula with air flow), supplemental oxygen, and no flow were randomly alternated every 10 minutes for 1 hour. Blinded research assistants used a validated observation scale to compare respiratory distress under each condition. At baseline, 27 of 32 (84%) patients were on oxygen. Three patients, all of whom were conscious and on oxygen at baseline, experienced increased respiratory distress without oxygen; reapplication of supplemental oxygen relieved their distress. The other 29 patients had no change in respiratory distress under the oxygen, medical air, and no flow conditions.

Cautions

All patients in this study were near death as measured by the Palliative Performance Scale, which assesses prognosis based on functional status and level of consciousness. Patients were excluded if they were receiving high‐flow oxygen by face mask or were experiencing respiratory distress at the time of initial evaluation. Some patients experienced increased discomfort after withdrawal of oxygen. Close observation is needed to determine which patients will experience distress.

Implications

The majority of patients who were receiving oxygen at baseline experienced no change in respiratory comfort when oxygen was withdrawn, supporting previous evidence that oxygen provides little benefit in nonhypoxemic patients. Oxygen may be an unnecessary intervention near death and has the potential to add to discomfort through nasal dryness and decreased mobility.

Sennosides Performed Similarly to Docusate Plus Sennosides in Managing Opioid‐Induced Constipation in Seriously Ill Patients

Tarumi Y, Wilson MP, Szafran O, Spooner GR. Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:213.

Background

Seriously ill patients frequently suffer from constipation, often as a result of opioid analgesics. Hospital clinicians should seek to optimize bowel regimens to prevent opioid‐induced constipation. A combination of the stimulant laxative sennoside and the stool softener docusate is often recommended to treat and prevent constipation. Docusate may not have additional benefit to sennoside, and may have significant burdens, including disturbing the absorption of other medications, adding to patients' pill burden and increasing nurse workload.[7]

Findings

In this double‐blinded trial, 74 patients in 3 inpatient hospices in Canada were randomized to receive sennoside plus either docusate 100 mg, or placebo tablets twice daily, or sennoside plus placebo for 10 days. Most patients had cancer as a life‐limiting diagnosis and received opioids during the study period. All were able to tolerate pills and food or sips of fluid. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in stool frequency, volume, consistency, or patients' perceptions of difficulty with defecation. The percentage of patients who had a bowel movement at least every 3 days was 71% in the docusate plus sennoside group and 81% in the sennoside only group (P=0.45). There was also no significant difference between the groups in sennoside dose (which ranged between 13, 8.6 mg tablets daily), mean morphine equivalent daily dosage, or other bowel interventions.

Cautions

The trial was small, though it was adequately powered to detect a clinically meaningful difference between the 2 groups of 0.5 in the average number of bowel movements per day. The consent rate was low (26%); the authors do not detail reasons patients were not randomized. Patients who did not participate might have had different responses.

Implications

Consistent with previous work,[7] these results indicate that docusate is probably not needed for routine management of opioid‐induced constipation in seriously ill patients.

Sublingual Atropine Performed Similarly to Placebo in Reducing Noise Associated With Respiratory Rattle Near Death

Heisler M, Hamilton G, Abbott A, et al. Randomized double‐blind trial of sublingual atropine vs. placebo for the management of death rattle. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;45(1):1422.

Background

Increased respiratory tract secretions in patients near death can cause noisy breathing, often referred to as a death rattle. Antimuscarinic medications, such as atropine, are frequently used to decrease audible respirations and family distress, though little evidence exists to support this practice.

Findings

In this double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group trial at 3 inpatient hospices, 177 terminally ill patients with audible respiratory secretions were randomized to 2 drops of sublingual atropine 1% solution or placebo drops. Bedside nurses rated patients' respiratory secretions at enrollment, and 2 and 4 hours after receiving atropine or placebo. There were no differences in noise score between subjects treated with atropine and placebo at 2 hours (37.8% vs. 41.3%, P=0.24) or at 4 hours (39.7% and 51.7%, P=0.21). There were no differences in the safety end point of change in heart rate (P=0.47).

Cautions

Previous studies comparing different anticholinergic medications and routes of administration to manage audible respiratory secretions had variable response rates but suggested a benefit to antimuscarinic medications. However, these trials had significant methodological limitations including lack of randomization and blinding. The improvement in death rattle over time in other studies may suggest a favorable natural course for respiratory secretions rather than a treatment effect.

Implications

Although generalizability to other antimuscarinic medications and routes of administration is limited, in a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, sublingual atropine did not reduce the noise from respiratory secretions when compared to placebo.

PATIENT AND FAMILY OUTCOMES AFTER CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION

Over Half of Older Adult Survivors of In‐Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Were Alive At 1 Year

Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA, et al. Long‐term outcomes in elderly survivors of in‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:10191026.

Background

Studies of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes have focused on survival to hospital discharge. Little is known about long‐term outcomes following in‐hospital cardiac arrest in older adults.

Findings

The authors analyzed data from the Get With the GuidelinesResuscitation registry from 2000 to 2008 and Medicare inpatient files from 2000 to 2010. The cohort included 6972 patients at 401 hospitals who were discharged after surviving in‐hospital arrest. Outcomes were survival and freedom from hospital readmission at 1 year after discharge. At discharge, 48% of patients had either no or mild neurologic disability at discharge; the remainder had moderate to severe neurologic disability. Overall, 58% of patients who were discharged were still alive at 1 year. Survival rates were lowest for patients who were discharged in coma or vegetative state (8% at 1 year), and highest for those discharged with mild or no disability (73% at 1 year). Older patients had lower survival rates than younger patients, as did men compared with women and blacks compared with whites. At 1 year, 34.4% of the patients had not been readmitted. Predictors of readmission were similar to those for lower survival rates.

Cautions

This study only analyzed survival data from patients who survived to hospital discharge after receiving in‐hospital CPR, not all patients who had a cardiac arrest. Thus, the survival rates reported here do not include patients who died during the original arrest, or who survived the arrest but died during their hospitalization. The 1‐year survival rate for people aged 65 years and above following a cardiac arrest is not reported but is likely to be about 10%, based on data from this registry.[8] Data were not available for health status, neurologic status, or quality of life of the survivors at 1 year.

Implications

Older patients who receive in‐hospital CPR and have a good neurologic status at hospital discharge have good long‐term outcomes. In counseling patients about CPR, it is important to note that most patients who receive CPR do not survive to hospital discharge.

Families Who Were Present During CPR Had Decreased Post‐traumatic Stress Symptoms

Jabre P, Belpomme V, Azoulay E, et al. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:10081018.

Background

Family members who watch their loved ones undergo (CPR) might have increased emotional distress. Alternatively, observing CPR may allow for appreciation of the efforts taken for their loved one and provide comfort at a challenging time. The right balance of benefit and harm is unclear.

Findings

Between 2009 and 2011, 15 prehospital emergency medical service units in France were randomized to offer adult family members the opportunity to observe CPR or follow their usual practice. A total of 570 relatives were enrolled. In the intervention group, 79% of relatives observed CPR, compared to 43% in the control group. There was no difference in the effectiveness of CPR between the 2 groups. At 90 days, post‐traumatic stress symptoms were more common in the control group (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2‐2.5). At 90 days, those who were present for the resuscitation also had fewer symptoms of anxiety and fewer symptoms of depression (P0.009 for both). Stress of the medical teams involved in the CPR was not different between the 2 groups. No malpractice claims were filed in either group.

Cautions

The study was conducted only in France, so the results may not be generalizable outside of France. In addition, the observed resuscitation was for patients who suffered a cardiac arrest in the home; it is unclear if the same results would be found in the emergency department or hospital.

Implications

This is the highest quality study to date in this area that argues for actively inviting family members to be present for resuscitation efforts in the home. Further studies are needed to determine if hospitals should implement standard protocols. In the meantime, providers who perform CPR should consider inviting families to observe, as it may result in less emotional distress for family members.

COMMUNICATION AND DECISION MAKING

Surrogate Decision Makers Interpreted Prognostic Information Optimistically

Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, et al. Surrogate decision makers' interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed‐methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:360366.

Background

Surrogates of critically ill patients often have beliefs about prognosis that are discordant from what is told to them by providers. Little is known about why this is the case.

Findings

Eighty surrogates of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) were given questionnaires with hypothetical prognostic statements and asked to identify a survival probability associated with each statement on a 0% to 100% scale. Interviewers examined the questionnaires to identify responses that were not concordant with the given prognostic statements. They then interviewed participants to determine why the answers were discordant. The researchers found that surrogates were more likely to offer an overoptimistic interpretation of statements communicating a high risk of death, compared to statements communicating a low risk of death. The qualitative interviews revealed that surrogates felt they needed to express ongoing optimism and that patient factors not known to the medical team would lead to better outcomes.

Cautions

The participants were surrogates who were present in the ICU at the time when study investigators were there, and thus the results may not be generalizable to all surrogates. Only a subset of participants completed qualitative interviews. Prognostic statements were hypothetical. Written prognostic statements may be interpreted differently than spoken statements.

Implications

Surrogate decision makers may interpret prognostic statements optimistically, especially when a high risk of death is estimated. Inaccurate interpretation may be related to personal beliefs about the patients' strengths and a need to hold onto hope for a positive outcome. When communicating with surrogates of critically ill patients, providers should be aware that, beyond the actual information shared, many other factors influence surrogates' beliefs about prognosis.

A Majority of Patients With Metastatic Cancer Felt That Chemotherapy Might Cure Their Disease

Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Chronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:16161625.

Background

Chemotherapy for advanced cancer is not curative, and many cancer patients overestimate their prognosis. Little is known about patients' understanding of the goals of chemotherapy when cancer is advanced.

Findings

Participants were part of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance study. Patients with stage IV lung or colon cancer who opted to receive chemotherapy (n=1193) were asked how likely they thought it was that the chemotherapy would cure their cancer. A majority (69% of lung cancer patients and 81% of colon cancer patients) felt that chemotherapy might cure their disease. Those who rated their physicians very favorably in satisfaction surveys were more likely to feel that that chemotherapy might be curative, compared to those who rated their physician less favorably (OR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.33‐2.72).

Cautions

The study did not include patients who died soon after diagnosis and thus does not provide information about those who opted for chemotherapy but did not survive to the interview. It is possible that responses were influenced by participants' need to express optimism (social desirability bias). It is not clear how or whether prognostic disclosure by physicians caused the lower satisfaction ratings.

Implications

Despite the fact that stage IV lung and colon cancer are not curable with chemotherapy, a majority of patients reported believing that chemotherapy might cure their disease. Hospital clinicians should be aware that many patients who they view as terminally ill believe their illness may be cured.

Older Patients Who Viewed a Goals‐of‐Care Video at Admission to a Skilled Nursing Facility Were More Likely to Prefer Comfort Care

Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals‐of‐care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:805811.

Background

Seriously ill older patients are frequently discharged from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). It is important to clarify and document patients' goals for care at the time of admission to SNFs, to ensure that care provided there is consistent with patients' preferences. Previous work has shown promise using videos to assist patients in advance‐care planning, providing realistic and standardized portrayals of different treatment options.[9, 10]

Findings

English‐speaking patients at least 65 years of age who did not have altered mental status were randomized to hear a verbal description (n=51) or view a 6‐minute video (n=50) that presented the same information accompanied by pictures of patients of 3 possible goals of medical care: life‐prolonging care, limited medical care, and comfort care. After the video or narrative, patients were asked what their care preference would be if they became more ill while at the SNF. Patients who viewed the video were more likely to report a preference for comfort care, compared to patients who received the narrative, 80% vs 57%, P=0.02. In a review of medical records, only 31% of patients who reported a preference for comfort care had a do not resuscitate order at the SNF.

Cautions

The study was conducted at 2 nursing homes located in the Boston, Massachusetts area, which may limit generalizability. Assessors were not blinded to whether the patient saw the video or received the narrative, which may have introduced bias. The authors note that the video aimed to present the different care options without valuing one over the other, though it may have inadvertently presented one option in a more favorable light.

Implications

Videos may be powerful tools for helping nursing home patients to clarify goals of care, and might be applied in the hospital setting prior to transferring patients to nursing homes. There is a significant opportunity to improve concordance of care with preferences through better documentation and implementation of code status orders when transferring patients to SNFs.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Drs. Anderson and Johnson and Mr. Horton received an honorarium and support for travel to present findings resulting from the literature review at the Annual Assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association on March 16, 2013 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Dr. Anderson was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF‐CTSI grant number KL2TR000143. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Journals That Were Hand Searched to Identify Articles, By Topic Area

General:

- British Medical Journal

- Journal of the American Medical Association

- Lancet

- New England Journal of Medicine

Internal medicine:

- Annals Internal Medicine

- Archives Internal Medicine

- Journal of General Internal Medicine

- Journal of Hospital Medicine

Palliative care and symptom management:

- Journal Pain and Symptom Management

- Journal of Palliative Care

- Journal of Palliative Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Pain

Oncology:

- Journal of Clinical Oncology

- Supportive Care in Cancer

Critical care:

- American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

- Critical Care Medicine

Pediatrics:

- Pediatrics

Geriatrics:

- Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

Education:

- Academic Medicine

Nursing:

- Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing

- Oncology Nursing Forum

Seriously ill patients frequently receive care in hospitals,[1, 2, 3] and palliative care is a core competency for hospitalists.[4, 5] The goal of this update was to summarize and critique recently published research that has the highest potential to impact the clinical practice of palliative care in the hospital. We reviewed articles published between January 2012 and May 2013. To identify articles, we hand‐searched 22 leading journals (see Appendix) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and performed a PubMed keyword search using the terms hospice and palliative care. We evaluated identified articles based on scientific rigor and relevance to hospital practice. In this review, we summarize 9 articles that were collectively selected as having the highest impact on the clinical practice of hospital palliative care. We summarize each article and its findings and note cautions and implications for practice.

SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

Indwelling Pleural Catheters and Talc Pleurodesis Provide Similar Dyspnea Relief in Patients With Malignant Pleural Effusions

Davies HE, Mishra EK, Kahan BC, et al. Effect of an indwelling pleural catheter vs chest tube and talc pleurodesis for relieving dyspnea in patients with malignant pleural effusion. JAMA. 2012;307:23832389.

Background

Expert guidelines recommend chest‐tube insertion and talc pleurodesis as a first‐line therapy for symptomatic malignant pleural effusions, but indwelling pleural catheters are gaining in popularity.[6] The optimal management is unknown.

Findings

A total of 106 patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic malignant pleural effusion were randomized to undergo talc pleurodesis or placement of an indwelling pleural catheter. Most patients had metastatic breast or lung cancer. Overall, there were no differences in relief of dyspnea at 42 days between patients who received indwelling catheters and pleurodesis; importantly, more than 75% of patients in both groups reported improved shortness of breath. The initial hospitalization was much shorter in the indwelling catheter group (0 days vs 4 days). There was no difference in quality of life, but in surviving patients, dyspnea at 6 months was better with the indwelling catheter. In the talc group, 22% of patients required further pleural procedures compared with 6% in the indwelling catheter group. Patients in the talc group had a higher frequency of adverse events than in the catheter group (40% vs 13%). In the catheter group, the most common adverse events were pleural infection, cellulitis, and catheter obstruction.

Cautions

The study was small and unblinded, and the primary outcome was subjective dyspnea. The study occurred at 7 hospitals, and the impact of institutional or provider experience was not taken into account. Last, overall costs of care, which could impact the choice of intervention, were not calculated.

Implications

This was a small but well‐done study showing that indwelling catheters and talc pleurodesis provide similar relief of dyspnea 42 days postintervention. Given these results, both interventions seem to be acceptable options. Clinicians and patients could select the best option based on local procedural expertise and patient factors such as preference, ability to manage a catheter, and life expectancy.

Most Dying Patients Do Not Experience Increased Respiratory Distress When Oxygen is Withdrawn

Campbell ML, Yarandi H, Dove‐Medows E. Oxygen is nonbeneficial for most patients who are near death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):517523.

Background

Oxygen is frequently administered to patients at the end of life, yet there is limited evidence evaluating whether oxygen reduces respiratory distress in dying patients.

Findings

In this double‐blind, repeated‐measure study, patients served as their own controls as the investigators evaluated respiratory distress with and without oxygen therapy. The study included 32 patients who were enrolled in hospice or seen in palliative care consultation and had a diagnosis such as lung cancer or heart failure that might cause dyspnea. Medical air (nasal cannula with air flow), supplemental oxygen, and no flow were randomly alternated every 10 minutes for 1 hour. Blinded research assistants used a validated observation scale to compare respiratory distress under each condition. At baseline, 27 of 32 (84%) patients were on oxygen. Three patients, all of whom were conscious and on oxygen at baseline, experienced increased respiratory distress without oxygen; reapplication of supplemental oxygen relieved their distress. The other 29 patients had no change in respiratory distress under the oxygen, medical air, and no flow conditions.

Cautions

All patients in this study were near death as measured by the Palliative Performance Scale, which assesses prognosis based on functional status and level of consciousness. Patients were excluded if they were receiving high‐flow oxygen by face mask or were experiencing respiratory distress at the time of initial evaluation. Some patients experienced increased discomfort after withdrawal of oxygen. Close observation is needed to determine which patients will experience distress.

Implications

The majority of patients who were receiving oxygen at baseline experienced no change in respiratory comfort when oxygen was withdrawn, supporting previous evidence that oxygen provides little benefit in nonhypoxemic patients. Oxygen may be an unnecessary intervention near death and has the potential to add to discomfort through nasal dryness and decreased mobility.

Sennosides Performed Similarly to Docusate Plus Sennosides in Managing Opioid‐Induced Constipation in Seriously Ill Patients

Tarumi Y, Wilson MP, Szafran O, Spooner GR. Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:213.

Background

Seriously ill patients frequently suffer from constipation, often as a result of opioid analgesics. Hospital clinicians should seek to optimize bowel regimens to prevent opioid‐induced constipation. A combination of the stimulant laxative sennoside and the stool softener docusate is often recommended to treat and prevent constipation. Docusate may not have additional benefit to sennoside, and may have significant burdens, including disturbing the absorption of other medications, adding to patients' pill burden and increasing nurse workload.[7]

Findings

In this double‐blinded trial, 74 patients in 3 inpatient hospices in Canada were randomized to receive sennoside plus either docusate 100 mg, or placebo tablets twice daily, or sennoside plus placebo for 10 days. Most patients had cancer as a life‐limiting diagnosis and received opioids during the study period. All were able to tolerate pills and food or sips of fluid. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in stool frequency, volume, consistency, or patients' perceptions of difficulty with defecation. The percentage of patients who had a bowel movement at least every 3 days was 71% in the docusate plus sennoside group and 81% in the sennoside only group (P=0.45). There was also no significant difference between the groups in sennoside dose (which ranged between 13, 8.6 mg tablets daily), mean morphine equivalent daily dosage, or other bowel interventions.

Cautions

The trial was small, though it was adequately powered to detect a clinically meaningful difference between the 2 groups of 0.5 in the average number of bowel movements per day. The consent rate was low (26%); the authors do not detail reasons patients were not randomized. Patients who did not participate might have had different responses.

Implications

Consistent with previous work,[7] these results indicate that docusate is probably not needed for routine management of opioid‐induced constipation in seriously ill patients.

Sublingual Atropine Performed Similarly to Placebo in Reducing Noise Associated With Respiratory Rattle Near Death

Heisler M, Hamilton G, Abbott A, et al. Randomized double‐blind trial of sublingual atropine vs. placebo for the management of death rattle. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;45(1):1422.

Background

Increased respiratory tract secretions in patients near death can cause noisy breathing, often referred to as a death rattle. Antimuscarinic medications, such as atropine, are frequently used to decrease audible respirations and family distress, though little evidence exists to support this practice.

Findings

In this double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel group trial at 3 inpatient hospices, 177 terminally ill patients with audible respiratory secretions were randomized to 2 drops of sublingual atropine 1% solution or placebo drops. Bedside nurses rated patients' respiratory secretions at enrollment, and 2 and 4 hours after receiving atropine or placebo. There were no differences in noise score between subjects treated with atropine and placebo at 2 hours (37.8% vs. 41.3%, P=0.24) or at 4 hours (39.7% and 51.7%, P=0.21). There were no differences in the safety end point of change in heart rate (P=0.47).

Cautions

Previous studies comparing different anticholinergic medications and routes of administration to manage audible respiratory secretions had variable response rates but suggested a benefit to antimuscarinic medications. However, these trials had significant methodological limitations including lack of randomization and blinding. The improvement in death rattle over time in other studies may suggest a favorable natural course for respiratory secretions rather than a treatment effect.

Implications

Although generalizability to other antimuscarinic medications and routes of administration is limited, in a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, sublingual atropine did not reduce the noise from respiratory secretions when compared to placebo.

PATIENT AND FAMILY OUTCOMES AFTER CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION

Over Half of Older Adult Survivors of In‐Hospital Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Were Alive At 1 Year

Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA, et al. Long‐term outcomes in elderly survivors of in‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:10191026.

Background

Studies of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes have focused on survival to hospital discharge. Little is known about long‐term outcomes following in‐hospital cardiac arrest in older adults.

Findings

The authors analyzed data from the Get With the GuidelinesResuscitation registry from 2000 to 2008 and Medicare inpatient files from 2000 to 2010. The cohort included 6972 patients at 401 hospitals who were discharged after surviving in‐hospital arrest. Outcomes were survival and freedom from hospital readmission at 1 year after discharge. At discharge, 48% of patients had either no or mild neurologic disability at discharge; the remainder had moderate to severe neurologic disability. Overall, 58% of patients who were discharged were still alive at 1 year. Survival rates were lowest for patients who were discharged in coma or vegetative state (8% at 1 year), and highest for those discharged with mild or no disability (73% at 1 year). Older patients had lower survival rates than younger patients, as did men compared with women and blacks compared with whites. At 1 year, 34.4% of the patients had not been readmitted. Predictors of readmission were similar to those for lower survival rates.

Cautions

This study only analyzed survival data from patients who survived to hospital discharge after receiving in‐hospital CPR, not all patients who had a cardiac arrest. Thus, the survival rates reported here do not include patients who died during the original arrest, or who survived the arrest but died during their hospitalization. The 1‐year survival rate for people aged 65 years and above following a cardiac arrest is not reported but is likely to be about 10%, based on data from this registry.[8] Data were not available for health status, neurologic status, or quality of life of the survivors at 1 year.

Implications

Older patients who receive in‐hospital CPR and have a good neurologic status at hospital discharge have good long‐term outcomes. In counseling patients about CPR, it is important to note that most patients who receive CPR do not survive to hospital discharge.

Families Who Were Present During CPR Had Decreased Post‐traumatic Stress Symptoms

Jabre P, Belpomme V, Azoulay E, et al. Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:10081018.

Background

Family members who watch their loved ones undergo (CPR) might have increased emotional distress. Alternatively, observing CPR may allow for appreciation of the efforts taken for their loved one and provide comfort at a challenging time. The right balance of benefit and harm is unclear.

Findings

Between 2009 and 2011, 15 prehospital emergency medical service units in France were randomized to offer adult family members the opportunity to observe CPR or follow their usual practice. A total of 570 relatives were enrolled. In the intervention group, 79% of relatives observed CPR, compared to 43% in the control group. There was no difference in the effectiveness of CPR between the 2 groups. At 90 days, post‐traumatic stress symptoms were more common in the control group (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2‐2.5). At 90 days, those who were present for the resuscitation also had fewer symptoms of anxiety and fewer symptoms of depression (P0.009 for both). Stress of the medical teams involved in the CPR was not different between the 2 groups. No malpractice claims were filed in either group.

Cautions

The study was conducted only in France, so the results may not be generalizable outside of France. In addition, the observed resuscitation was for patients who suffered a cardiac arrest in the home; it is unclear if the same results would be found in the emergency department or hospital.

Implications

This is the highest quality study to date in this area that argues for actively inviting family members to be present for resuscitation efforts in the home. Further studies are needed to determine if hospitals should implement standard protocols. In the meantime, providers who perform CPR should consider inviting families to observe, as it may result in less emotional distress for family members.

COMMUNICATION AND DECISION MAKING

Surrogate Decision Makers Interpreted Prognostic Information Optimistically

Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, et al. Surrogate decision makers' interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed‐methods study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:360366.

Background

Surrogates of critically ill patients often have beliefs about prognosis that are discordant from what is told to them by providers. Little is known about why this is the case.

Findings

Eighty surrogates of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) were given questionnaires with hypothetical prognostic statements and asked to identify a survival probability associated with each statement on a 0% to 100% scale. Interviewers examined the questionnaires to identify responses that were not concordant with the given prognostic statements. They then interviewed participants to determine why the answers were discordant. The researchers found that surrogates were more likely to offer an overoptimistic interpretation of statements communicating a high risk of death, compared to statements communicating a low risk of death. The qualitative interviews revealed that surrogates felt they needed to express ongoing optimism and that patient factors not known to the medical team would lead to better outcomes.

Cautions

The participants were surrogates who were present in the ICU at the time when study investigators were there, and thus the results may not be generalizable to all surrogates. Only a subset of participants completed qualitative interviews. Prognostic statements were hypothetical. Written prognostic statements may be interpreted differently than spoken statements.

Implications

Surrogate decision makers may interpret prognostic statements optimistically, especially when a high risk of death is estimated. Inaccurate interpretation may be related to personal beliefs about the patients' strengths and a need to hold onto hope for a positive outcome. When communicating with surrogates of critically ill patients, providers should be aware that, beyond the actual information shared, many other factors influence surrogates' beliefs about prognosis.

A Majority of Patients With Metastatic Cancer Felt That Chemotherapy Might Cure Their Disease

Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Chronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:16161625.

Background

Chemotherapy for advanced cancer is not curative, and many cancer patients overestimate their prognosis. Little is known about patients' understanding of the goals of chemotherapy when cancer is advanced.

Findings

Participants were part of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance study. Patients with stage IV lung or colon cancer who opted to receive chemotherapy (n=1193) were asked how likely they thought it was that the chemotherapy would cure their cancer. A majority (69% of lung cancer patients and 81% of colon cancer patients) felt that chemotherapy might cure their disease. Those who rated their physicians very favorably in satisfaction surveys were more likely to feel that that chemotherapy might be curative, compared to those who rated their physician less favorably (OR: 1.90; 95% CI: 1.33‐2.72).

Cautions

The study did not include patients who died soon after diagnosis and thus does not provide information about those who opted for chemotherapy but did not survive to the interview. It is possible that responses were influenced by participants' need to express optimism (social desirability bias). It is not clear how or whether prognostic disclosure by physicians caused the lower satisfaction ratings.

Implications

Despite the fact that stage IV lung and colon cancer are not curable with chemotherapy, a majority of patients reported believing that chemotherapy might cure their disease. Hospital clinicians should be aware that many patients who they view as terminally ill believe their illness may be cured.

Older Patients Who Viewed a Goals‐of‐Care Video at Admission to a Skilled Nursing Facility Were More Likely to Prefer Comfort Care

Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals‐of‐care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:805811.

Background

Seriously ill older patients are frequently discharged from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). It is important to clarify and document patients' goals for care at the time of admission to SNFs, to ensure that care provided there is consistent with patients' preferences. Previous work has shown promise using videos to assist patients in advance‐care planning, providing realistic and standardized portrayals of different treatment options.[9, 10]

Findings

English‐speaking patients at least 65 years of age who did not have altered mental status were randomized to hear a verbal description (n=51) or view a 6‐minute video (n=50) that presented the same information accompanied by pictures of patients of 3 possible goals of medical care: life‐prolonging care, limited medical care, and comfort care. After the video or narrative, patients were asked what their care preference would be if they became more ill while at the SNF. Patients who viewed the video were more likely to report a preference for comfort care, compared to patients who received the narrative, 80% vs 57%, P=0.02. In a review of medical records, only 31% of patients who reported a preference for comfort care had a do not resuscitate order at the SNF.

Cautions

The study was conducted at 2 nursing homes located in the Boston, Massachusetts area, which may limit generalizability. Assessors were not blinded to whether the patient saw the video or received the narrative, which may have introduced bias. The authors note that the video aimed to present the different care options without valuing one over the other, though it may have inadvertently presented one option in a more favorable light.

Implications

Videos may be powerful tools for helping nursing home patients to clarify goals of care, and might be applied in the hospital setting prior to transferring patients to nursing homes. There is a significant opportunity to improve concordance of care with preferences through better documentation and implementation of code status orders when transferring patients to SNFs.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Drs. Anderson and Johnson and Mr. Horton received an honorarium and support for travel to present findings resulting from the literature review at the Annual Assembly of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association on March 16, 2013 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Dr. Anderson was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF‐CTSI grant number KL2TR000143. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX

Journals That Were Hand Searched to Identify Articles, By Topic Area

General:

- British Medical Journal

- Journal of the American Medical Association

- Lancet

- New England Journal of Medicine

Internal medicine:

- Annals Internal Medicine

- Archives Internal Medicine

- Journal of General Internal Medicine

- Journal of Hospital Medicine

Palliative care and symptom management:

- Journal Pain and Symptom Management

- Journal of Palliative Care

- Journal of Palliative Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Pain

Oncology:

- Journal of Clinical Oncology

- Supportive Care in Cancer

Critical care:

- American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

- Critical Care Medicine

Pediatrics:

- Pediatrics

Geriatrics:

- Journal of the American Geriatrics Society

Education:

- Academic Medicine

Nursing:

- Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing

- Oncology Nursing Forum

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Percent of Medicare decedents hospitalized at least once during the last six months of life 2007. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=133. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- , , , et al. Change in end‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309(5):470–477.

- , , , et al. End‐of‐life care for lung cancer patients in the United States and Ontario. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(11):853–862.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(suppl 1):48–56.

- Society of Hospital Medicine; 2008.The core competencies in hospital medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- , , , , . Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline. Thorax. 2010;65:ii32–ii40.

- , . A comparison of sennosides‐based bowel protocols with and without docusate in hospitalized patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(4):575–581.

- , , , , , . Trends in survival after In‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1912–1920.

- , , , et al. Use of video to facilitate end‐of‐life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305–310.

- , , , et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention‐postintervention study. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4331–4338.

- The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Percent of Medicare decedents hospitalized at least once during the last six months of life 2007. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=133. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- , , , et al. Change in end‐of‐life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309(5):470–477.

- , , , et al. End‐of‐life care for lung cancer patients in the United States and Ontario. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(11):853–862.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(suppl 1):48–56.

- Society of Hospital Medicine; 2008.The core competencies in hospital medicine. http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- , , , , . Management of a malignant pleural effusion: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline. Thorax. 2010;65:ii32–ii40.

- , . A comparison of sennosides‐based bowel protocols with and without docusate in hospitalized patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(4):575–581.

- , , , , , . Trends in survival after In‐hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1912–1920.

- , , , et al. Use of video to facilitate end‐of‐life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305–310.

- , , , et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention‐postintervention study. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4331–4338.

Communicating Discharge Instructions

Discharge from the hospital is a vulnerable time for patients. Nearly 1 in 5 patients experiences an adverse event during this transition, with a third of these being likely preventable.1, 2 Comprehensive discharge instructions are necessary to ensure a smooth transition from hospital to home, as the responsibility for care shifts from providers to the patient and caregivers. Unfortunately, patients often go home without understanding critical information about their hospital stay, such as their discharge diagnosis or medication changes,3, 4 leaving them both dissatisfied with their discharge instructions5 and at risk for hospital readmission.

Efforts to improve discharge education have focused on increasing communication between care provider and patient. The use of designated discharge coordinators,6, 7 implementation of teach‐back techniques to assess and confirm understanding,8 and adoption of patient‐centered educational materials all offer tools to improve communication with patients. However, guidelines for communication between providers and their shared role in patient discharge education, particularly between nurses and physicians, are scarce. Daily interdisciplinary rounds9 and shared electronic health records are potential ways to foster such communication, but the methods and frequency with which providers communicate about discharge instructions with each other is poorly understood. Furthermore, despite a common set of goals for discharge instructions,10, 11 it is unclear where the responsibility to provide these elements lies: with nurses, physicians, neither, or both.

Understanding perceptions and communication practices of providers in their delivery of discharge instructions is an important first step in defining responsibilities and improving accountability for discharge education. In this study, we surveyed nurses and physicians about their discharge education practices to better understand how each group sees their own role in discharge teaching, and how these findings may generate recommendations to improve future practices.

METHODS

Setting and Subjects

University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (UCSFMC) is a 600‐bed tertiary care academic teaching hospital. We surveyed interns, hospitalists on a teaching service, and day‐shift nurses from the inpatient medical service, based on care they provided at UCSFMC from July 2010 to February 2011. The 3 groups are the primary providers at our institution who deliver discharge education. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Committee on Human Research.

Survey Development

We developed a survey tool based on a literature review and expert input from local institutional leaders in nursing, residency training, and hospital medicine. The aims of the survey tool were to: 1) assess perceptions and practice of the nurse and physician role in patient discharge education; 2) describe the current practice of physiciannurse communication at discharge; and 3) assess openness to new communication tools.

Specific elements of discharge education assessed in the survey were established from the existing literature,10, 11 and our local best practices (see Supporting Information, Text Box, in the online version of this article). Prior to survey administration, we conducted informal focus groups of interns, hospitalists, and day‐shift nurses, and piloted the survey to assure clarity in the questions and proposed responses.

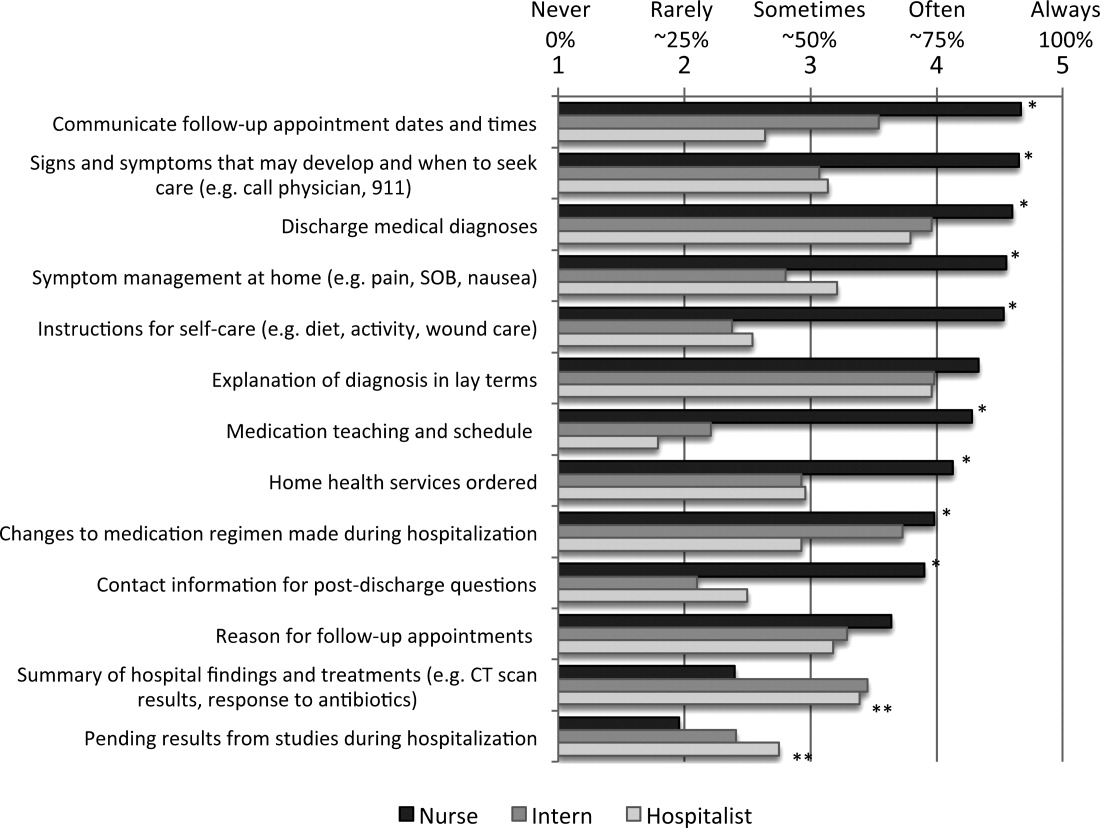

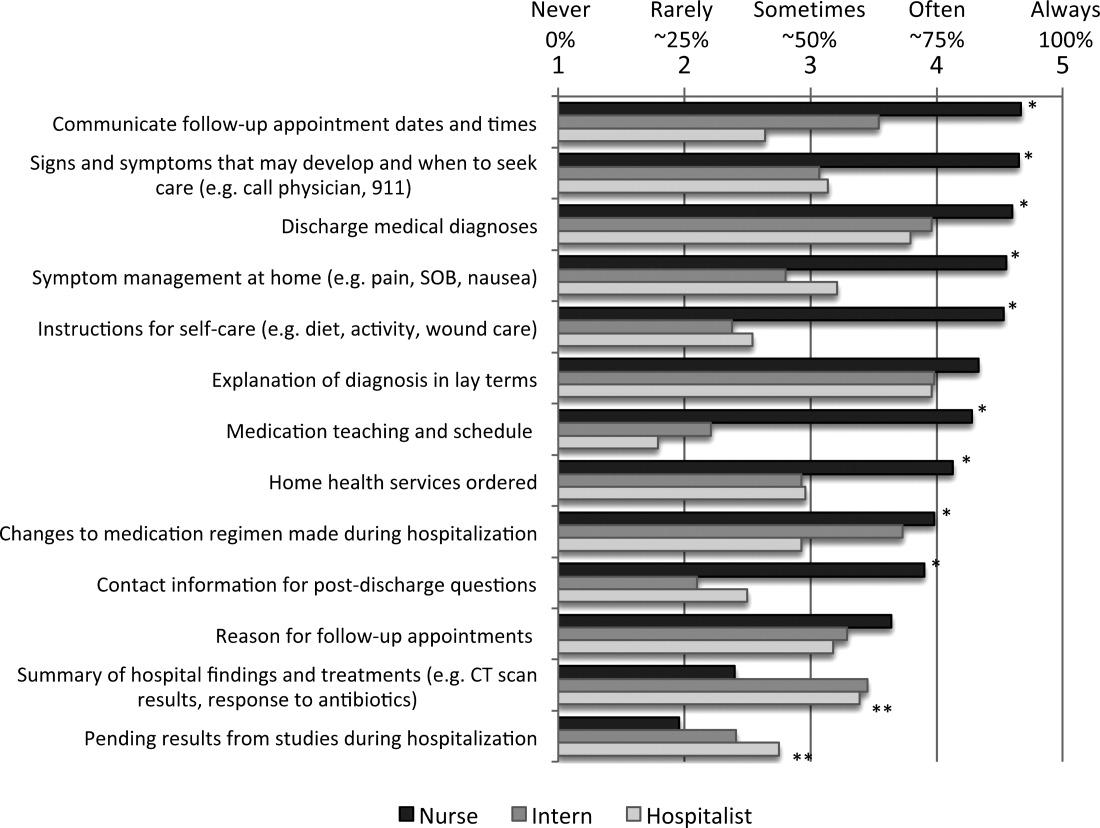

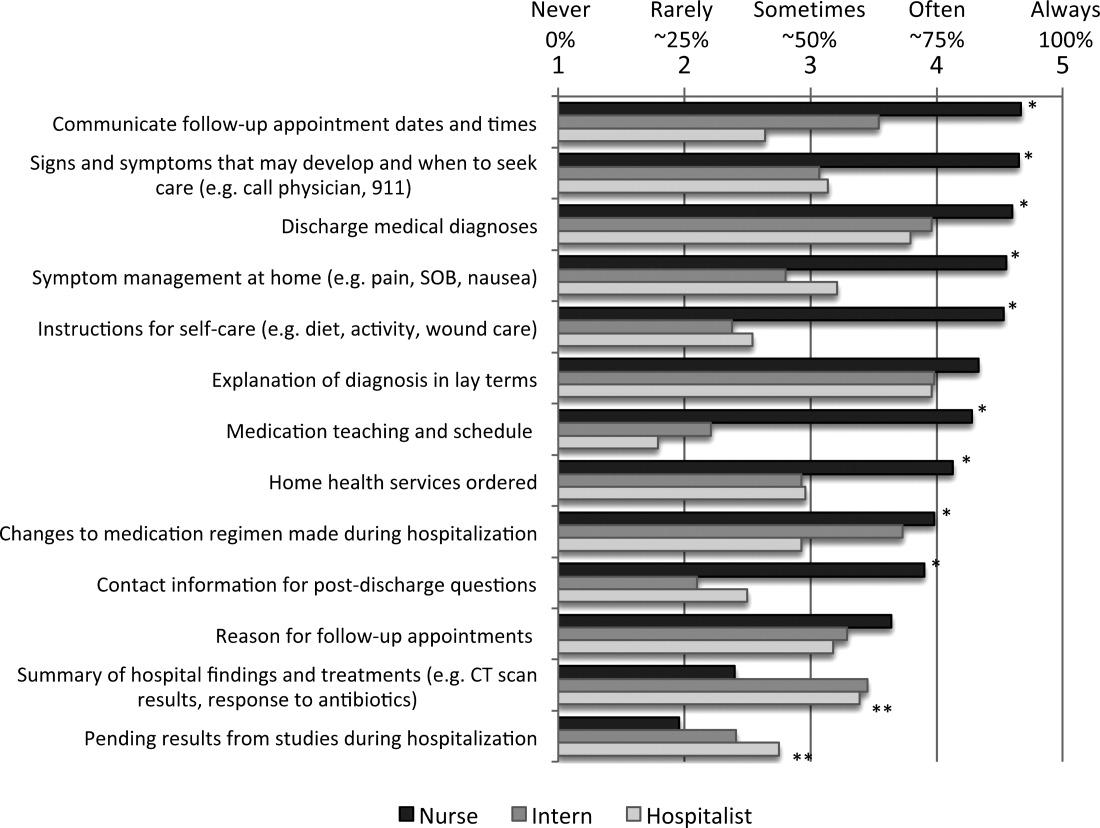

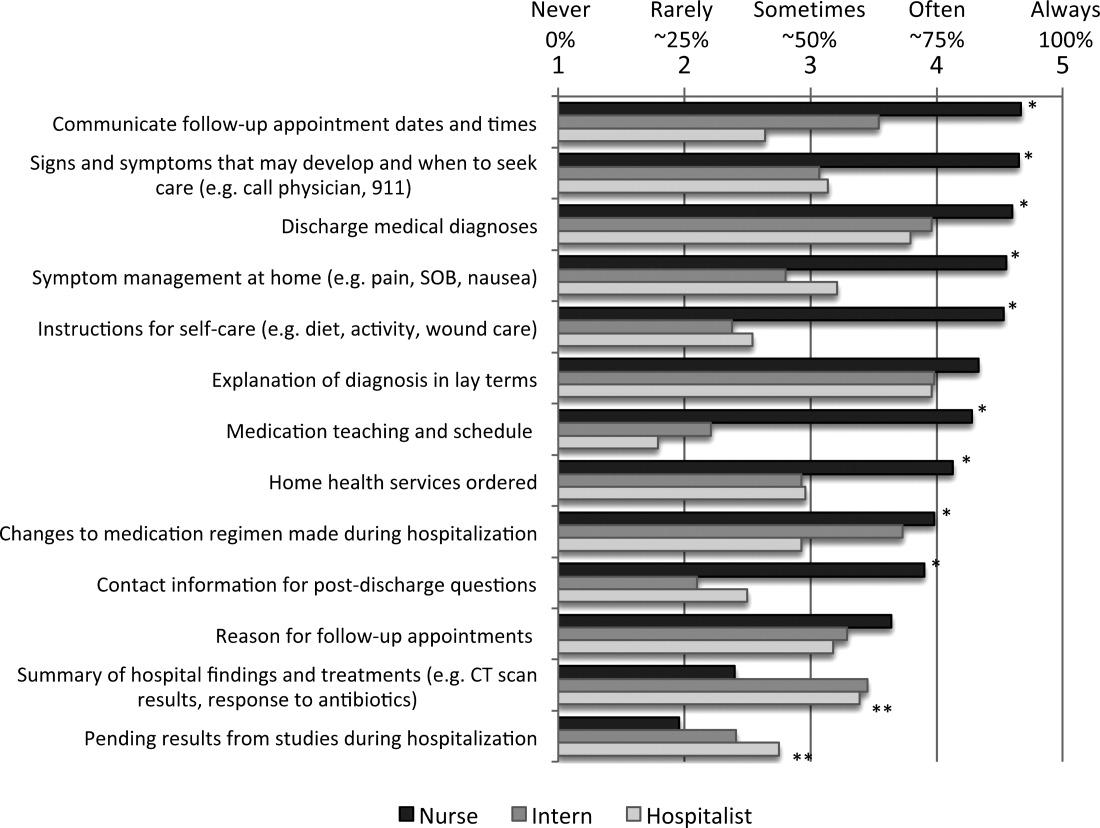

The survey asked respondents to assign responsibility for the discharge education elements to the physician, nurse, both, or neither, and then to describe their current practice in patient education and in physiciannurse communication. The frequency that respondents provide discharge education to patients and the frequency of nursephysician communication around the elements of discharge education were assessed using Likert scales (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). Finally, the survey asked respondents about their interest in tools to improve provider communication at discharge.

Survey Administration

Surveys were administered on paper and electronically, the latter using a commercial online survey tool. Paper surveys were circulated at nurse staff meetings on the 2 units in January and February 2011, with links to an electronic survey sent by e‐mail for those unable to attend. Electronic surveys were distributed via e‐mail to all interns and hospitalists in January 2011. The mid‐year time period was selected to ensure that all interns had provided clinical care at this hospital site. Two reminder e‐mails were sent to non‐respondents.

Data Analysis

Paper‐based surveys were subsequently entered into the online survey tool. Student t tests were used to compare Likert scale means between 2 provider groups, while analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare differences between nurses, interns, and hospitalists. Chi‐squared analysis was used to compare dichotomous variables of agreement and disagreement.

Likert scales of education to patients were dichotomized into frequent education (that provided often or always) versus infrequent education (that provided never, rarely, or sometimes). Likert scales of communication between nurses were similarly dichotomized. Correlation between frequent education to patients (often or always) and the frequency of communication between nurses and physicians (often or always) was assessed using Pearson's r.

RESULTS