User login

Ichthyosiform Sarcoidosis and Systemic Involvement

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan, systemic, granulomatous disease that most commonly affects the cutaneous, pulmonary, ocular, and cardiac organ systems. Cutaneous involvement occurs in approximately 20% to 35% of patients, with approximately 25% of patients demonstrating only dermatologic findings.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a highly variable presentation. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis (IS) is a rare form of this disease that has been described as presenting as polygonal adherent scales.2 It often is associated with internal organ involvement. We present a case of IS without any organ system involvement at the time of diagnosis. A review of the English-language literature was performed to ascertain the internal organ associations most commonly reported with IS.

Case Report

A 66-year-old black woman presented to dermatology with dark scaly patches noted by her primary care physician to be present on both of the lower extremities. The patient believed they were present for at least 4 years. She described dark spots confined to the lower legs that had gradually increased in size. Review of systems was negative for fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, vision changes, cough, dyspnea, and joint pains, and there was no history of either personal or familial cutaneous diseases.

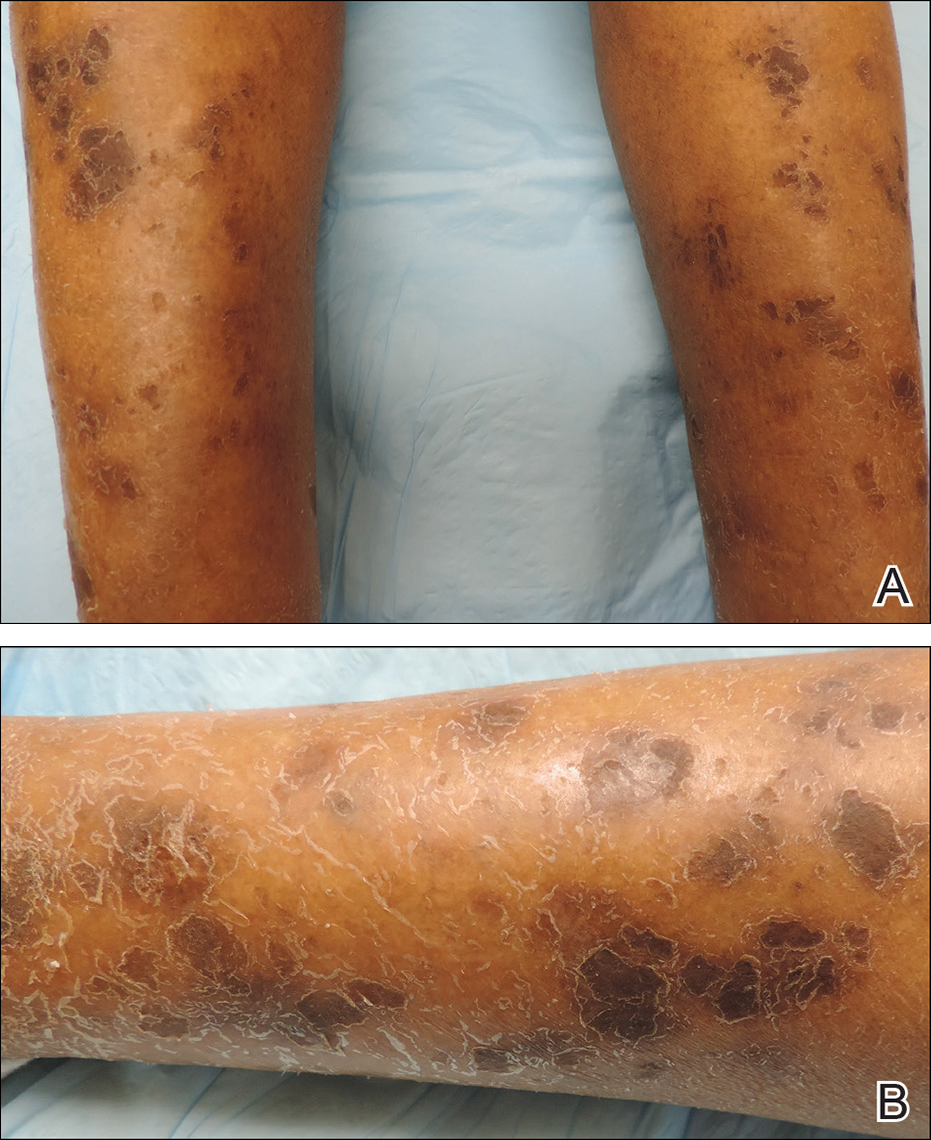

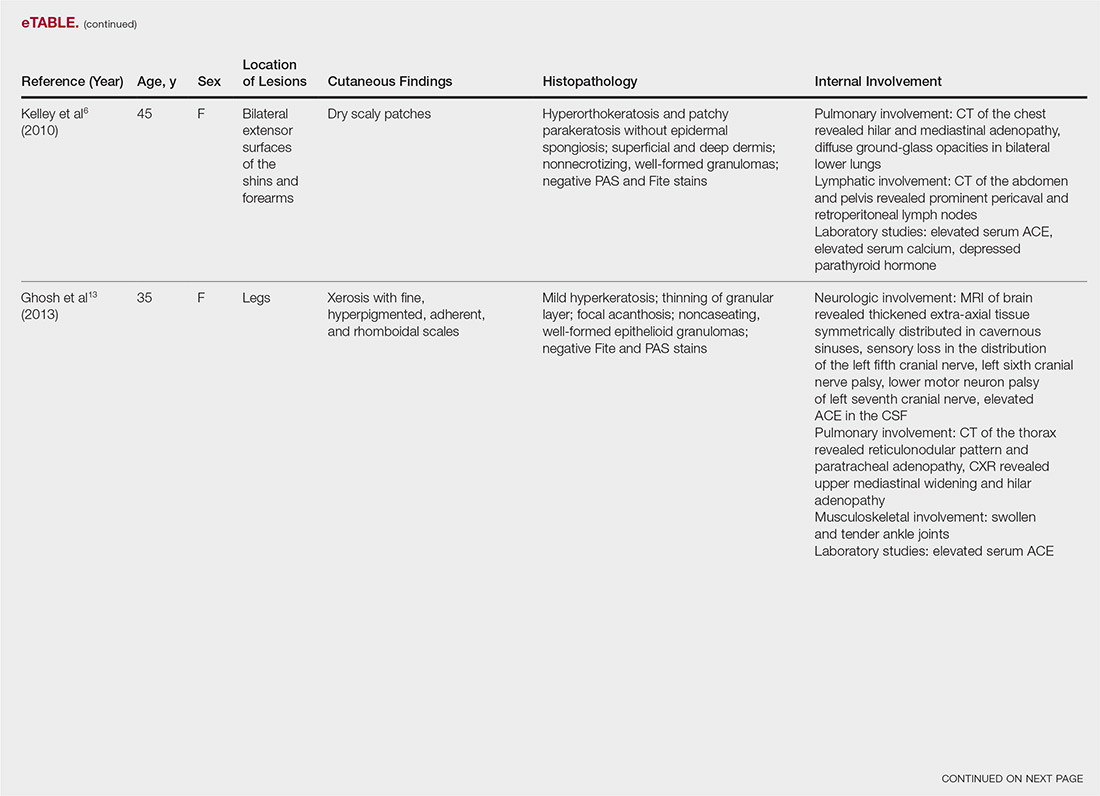

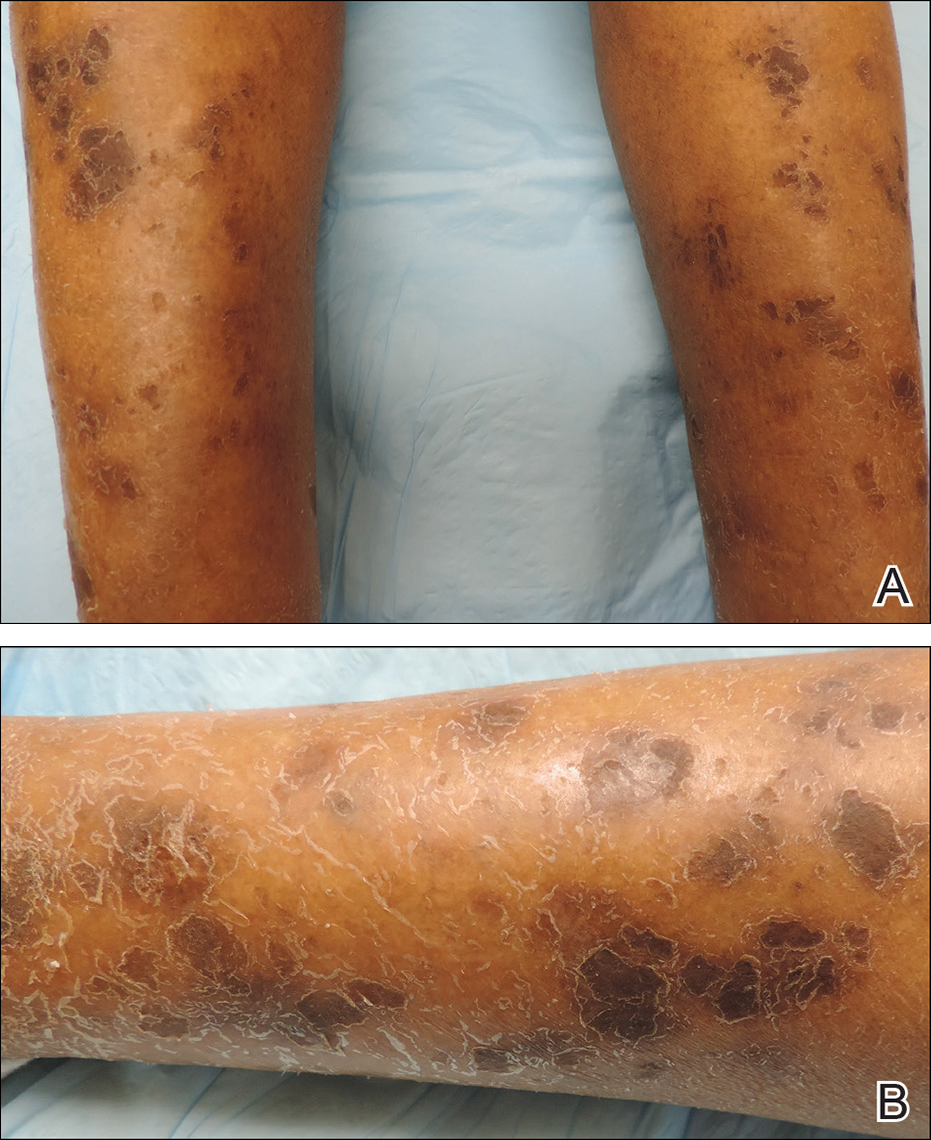

Physical examination revealed cutaneous patches of thin white scale with a sharp edge in arciform patterns on the lower extremities. Several of these patches were hyperpigmented and xerotic in appearance (Figure 1). The patches were limited to the lower legs, with no other lesions noted.

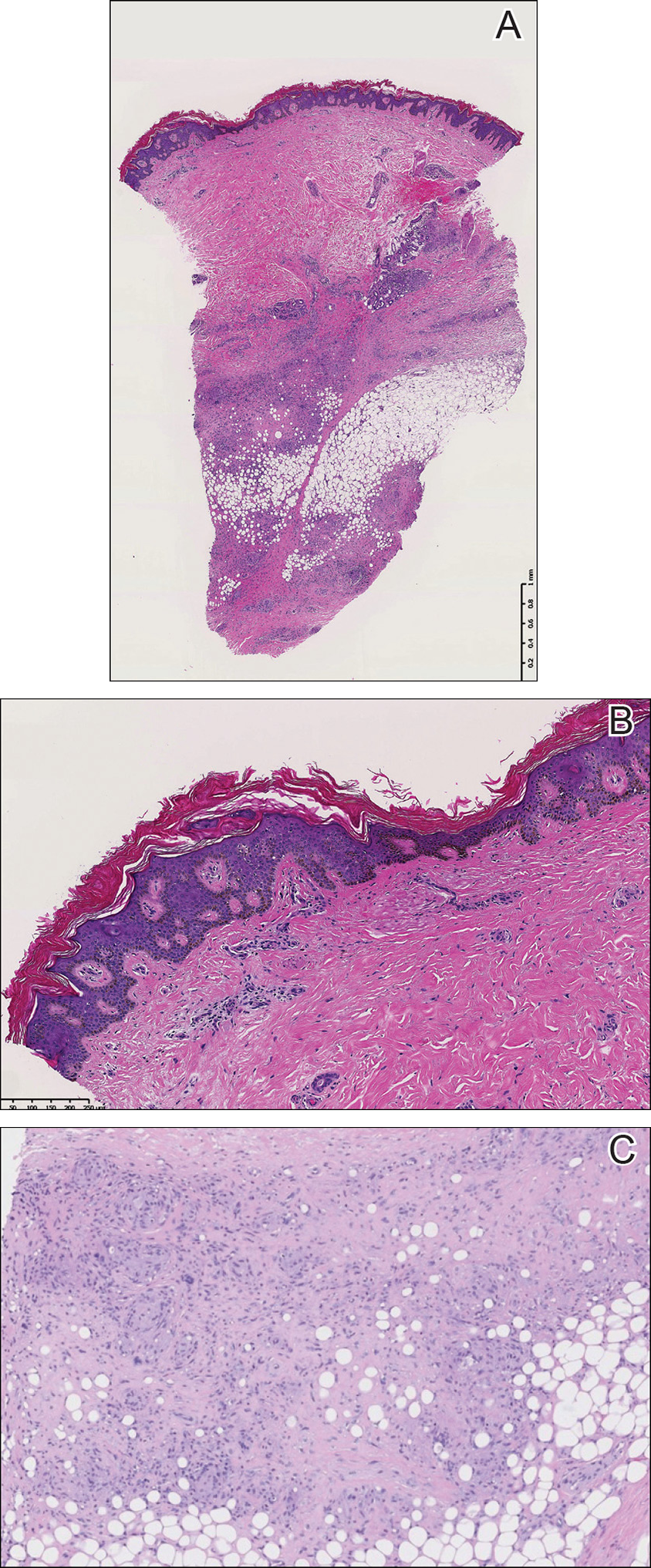

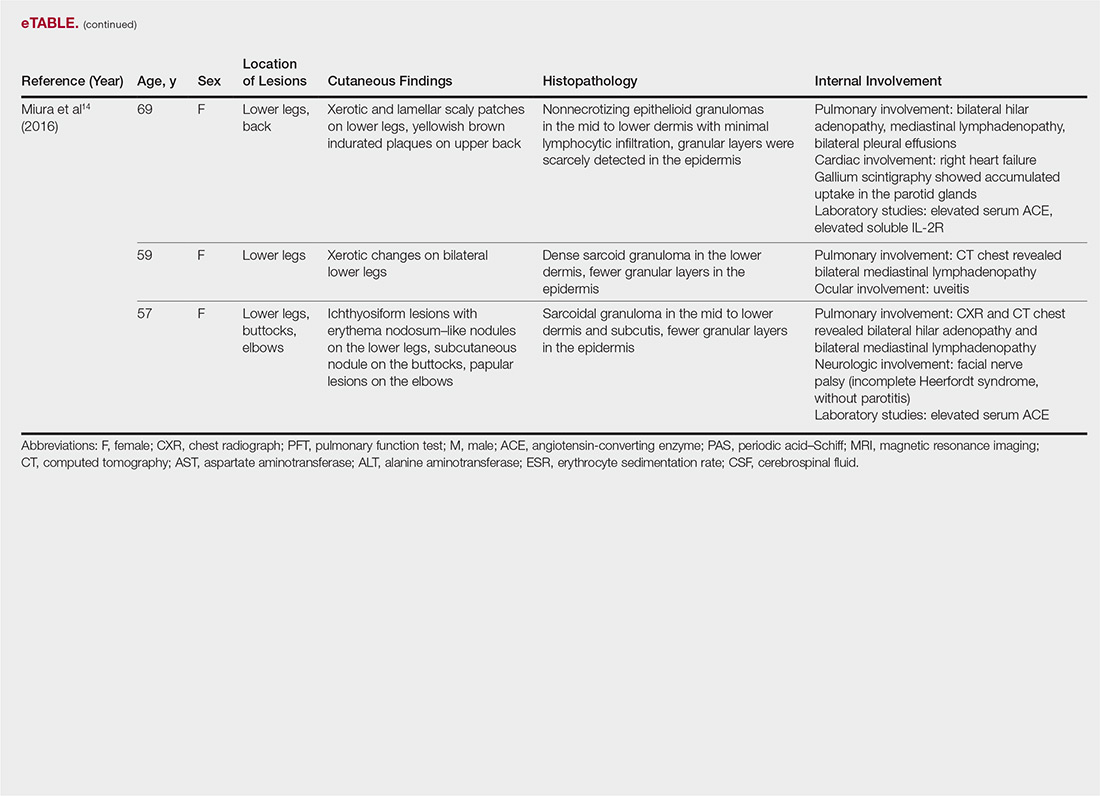

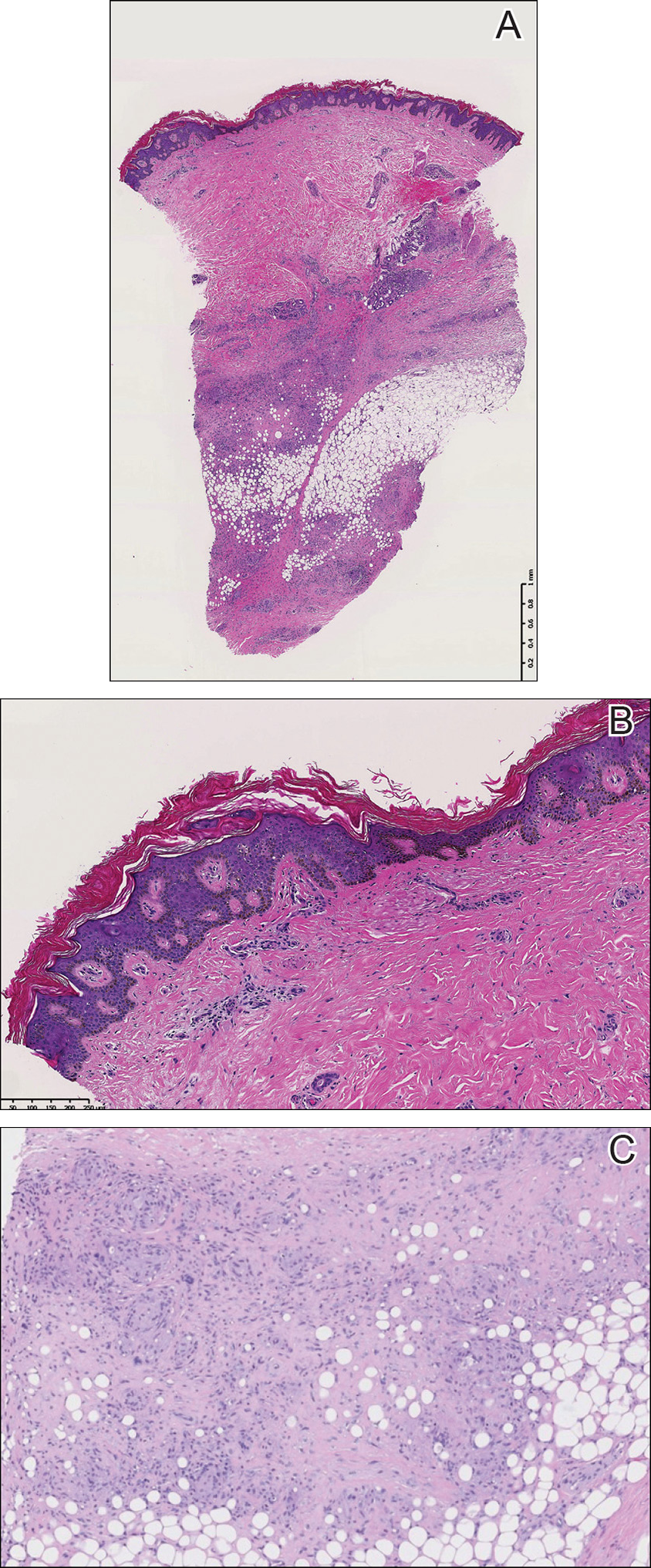

A punch biopsy of the skin on the right lower leg was performed. Histopathologic analysis showed epidermal compact hyperkeratosis with deep granulomatous infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue (Figures 2A and 2B). At high power, these granulomas were noted to be noncaseating naked granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes surrounded by sparse lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2C). Special stains including acid-fast bacilli, Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff were negative. The diagnosis of IS was made based on clinical presentation and primarily by histopathologic analysis.

The patient’s cutaneous lesions were treated with fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily. Although she did not notice a dramatic improvement in the plaques, they stabilized in size. Her primary care physician was notified and advised to begin a workup for involvement of other organ systems by sarcoidosis. Her initial evaluation, which included a chest radiograph and electrocardiogram, were unremarkable. Despite multiple attempts to persuade the patient to return for further follow-up, neither dermatology nor her primary care physician were able to complete a full workup.

Comment

Etiology

Although there are several theories regarding the etiology of sarcoidosis, the exact cause remains unknown. The body’s immune response, infectious agents, genetics, and the environment have all been thought to play a role. It has been well established that helper T cell (TH1) production of interferon and increased levels of tumor necrosis factor propagate the inflammatory response seen in sarcoidosis.3 More recently, TH17 cells have been found in cutaneous lesions, bronchoalveolar lavage samples, and the blood of patients with sarcoidosis, especially in those with active disease progression.3 Infectious agents such as mycobacteria and propionibacteria DNA or RNA also have been found in sarcoid samples.4 Several HLA-DRB1 variants have been associated with an increased incidence of sarcoidosis.5

Presentation

Characteristic dermatologic findings of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, nodules, and plaques located on the face, especially the nose, cheeks, and ears, and on the shins or ankles, as well as similar lesions around tattoos or scars. Sarcoid lesions also have been described as angiolupoid, lichenoid, annular, verrucous, ulcerative, and psoriasiform. Here we present an example of the uncommon type, ichthyosiform. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis is a rare variant described primarily in dark-skinned individuals, a finding supported by both our case and prior reports. Most reported cases have described IS lesions as having a pasted-on appearance, with adherent centers on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, head, and/or neck.6 Our case follows this descriptive pattern previously reported with adherent patches limited to the lower extremities.

Histopathology

The key histopathologic finding is the presence of noncaseating granulomas on biopsy. Sarcoid “specific” lesions rest on the identification of the noncaseating granulomas, while “nonspecific” lesions such as erythema nodosum fail to demonstrate this finding.1

Systemic Involvement

The IS type is believed to be an excellent marker for systemic disease, with approximately 95% of reported cases having some form of systemic illness.6 Acquired ichthyosis should warrant further investigation for systemic disease. Early recognition could be beneficial for the patient because the ichthyosiform type is believed to precede the diagnosis of systemic disease in most cases by a median of 3 months.6

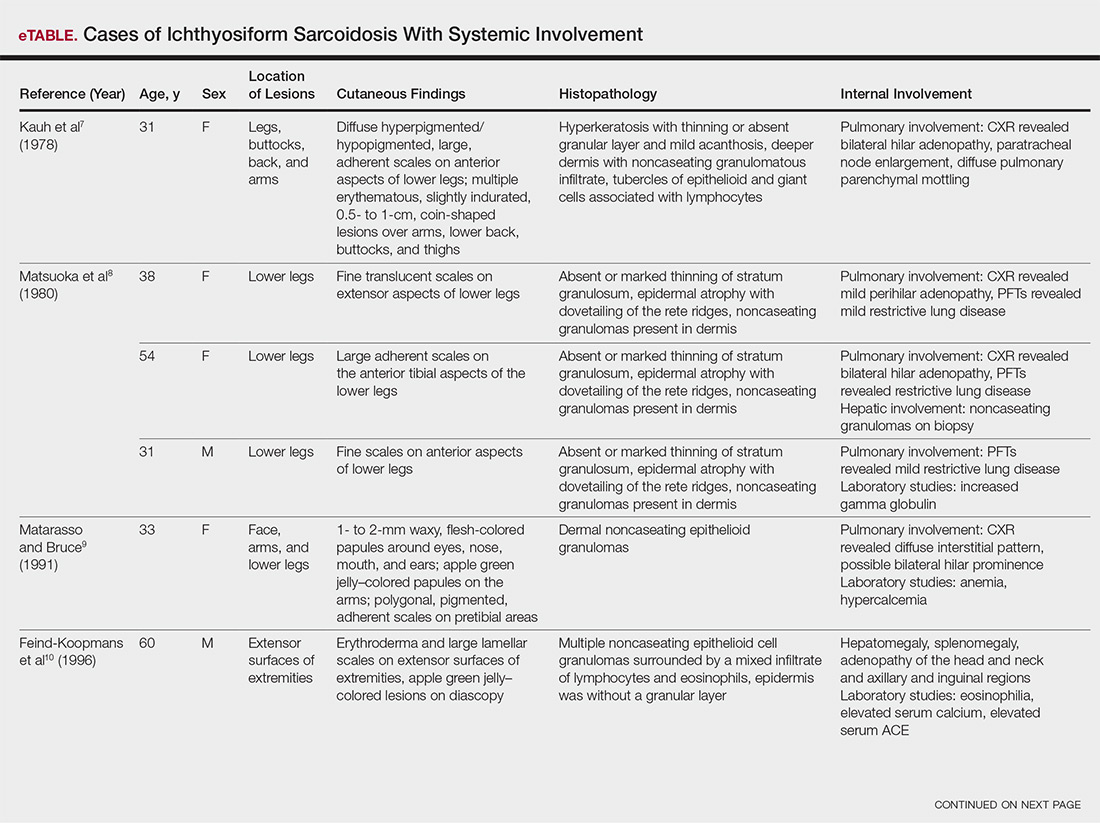

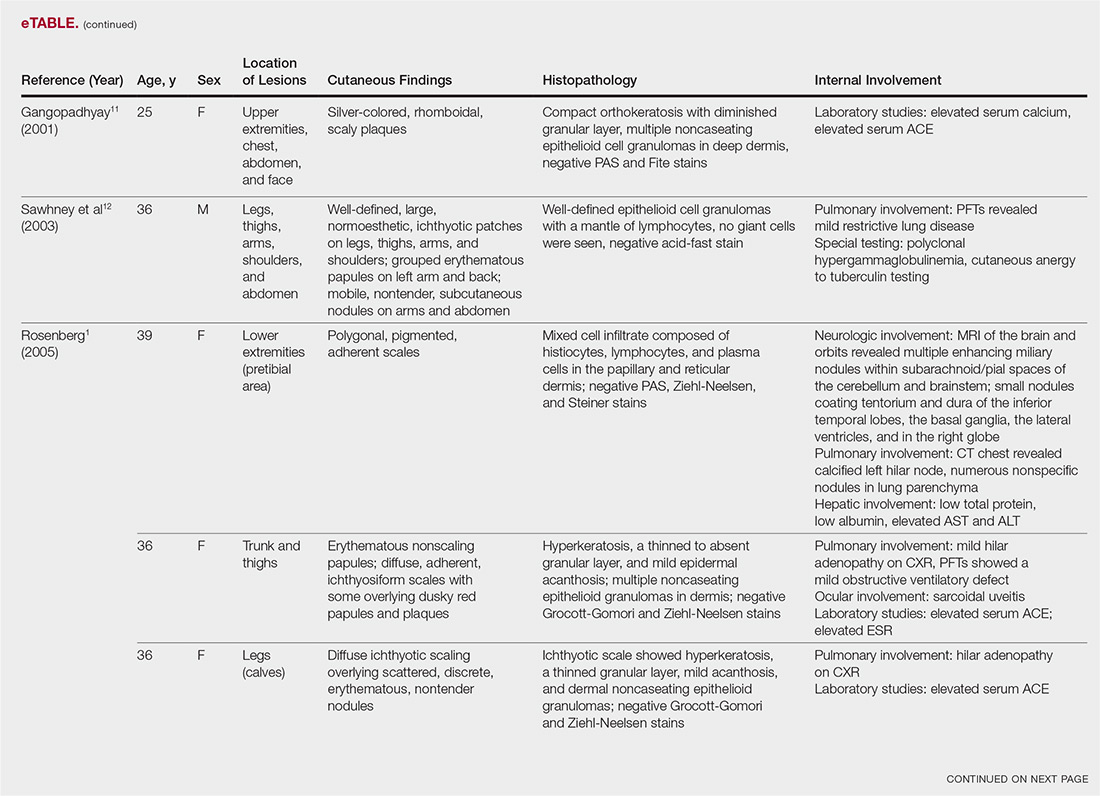

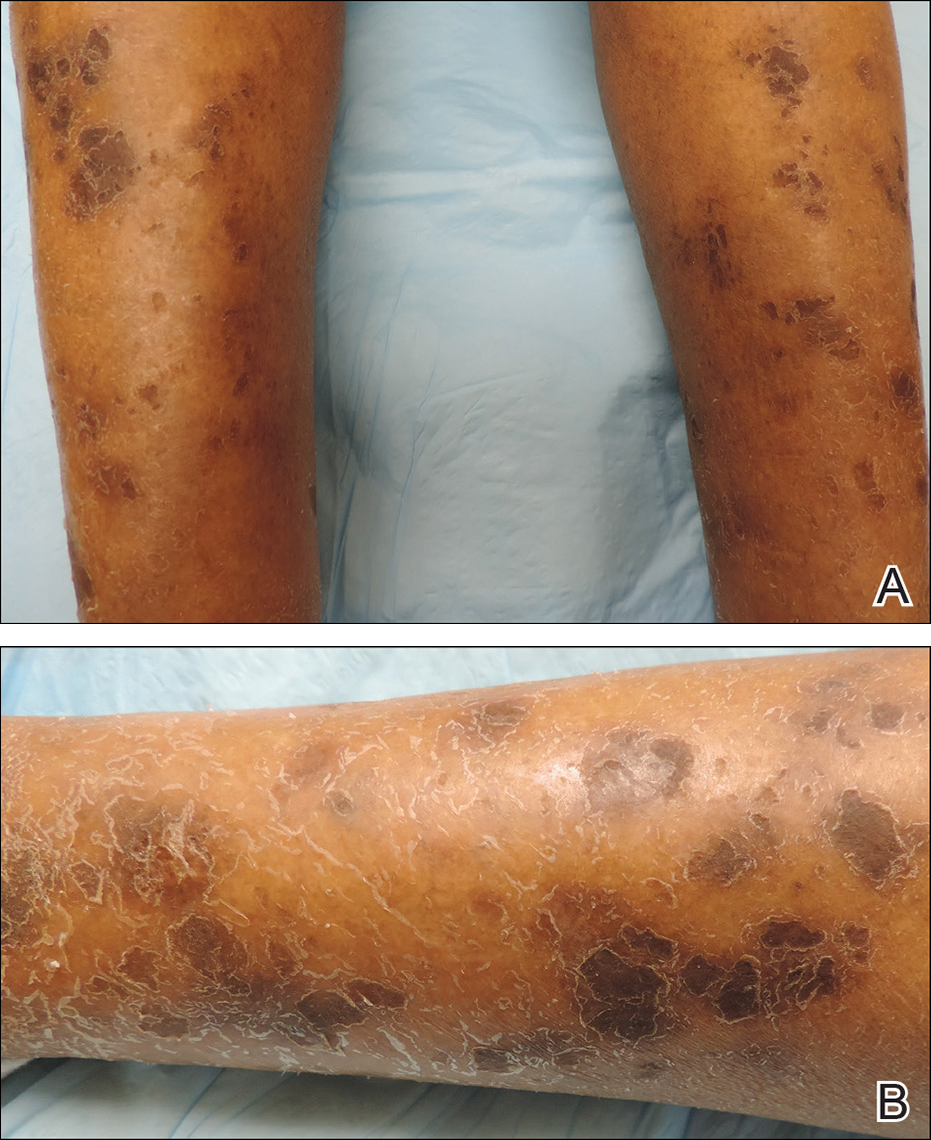

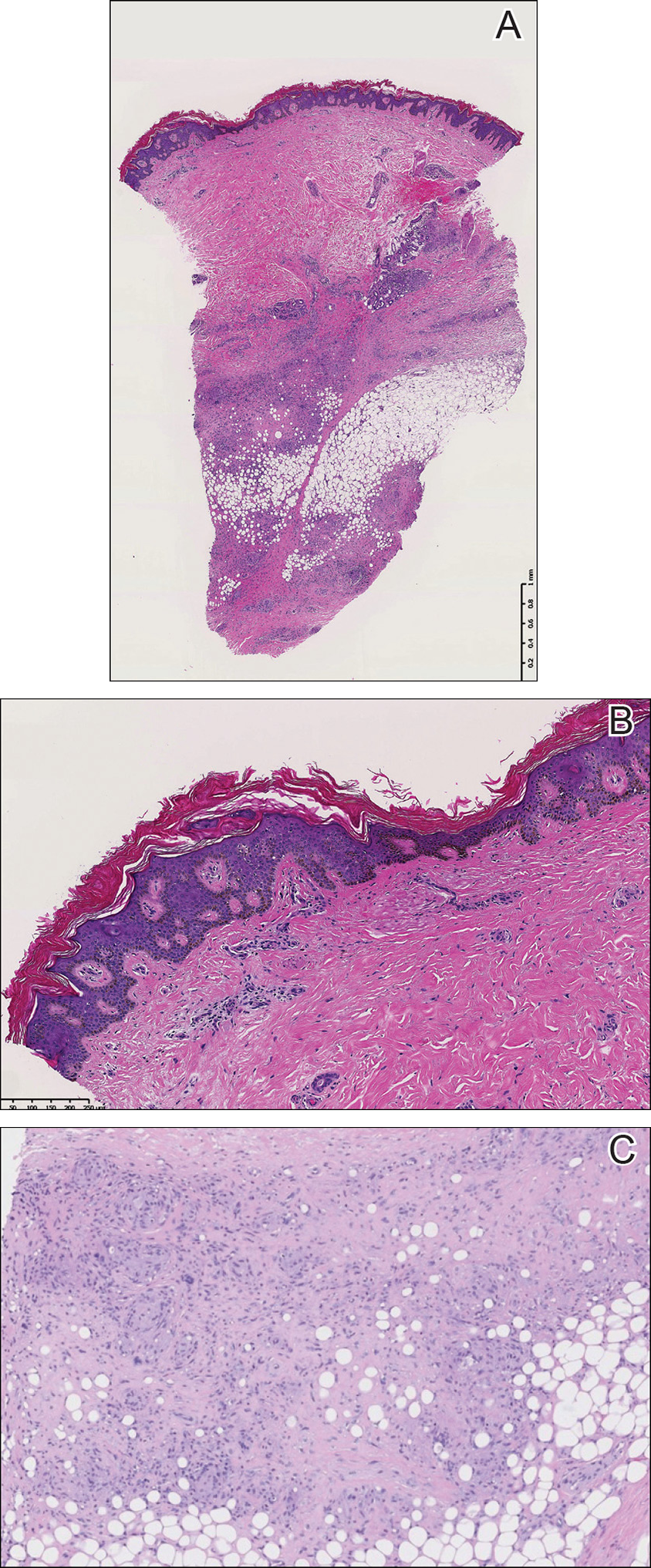

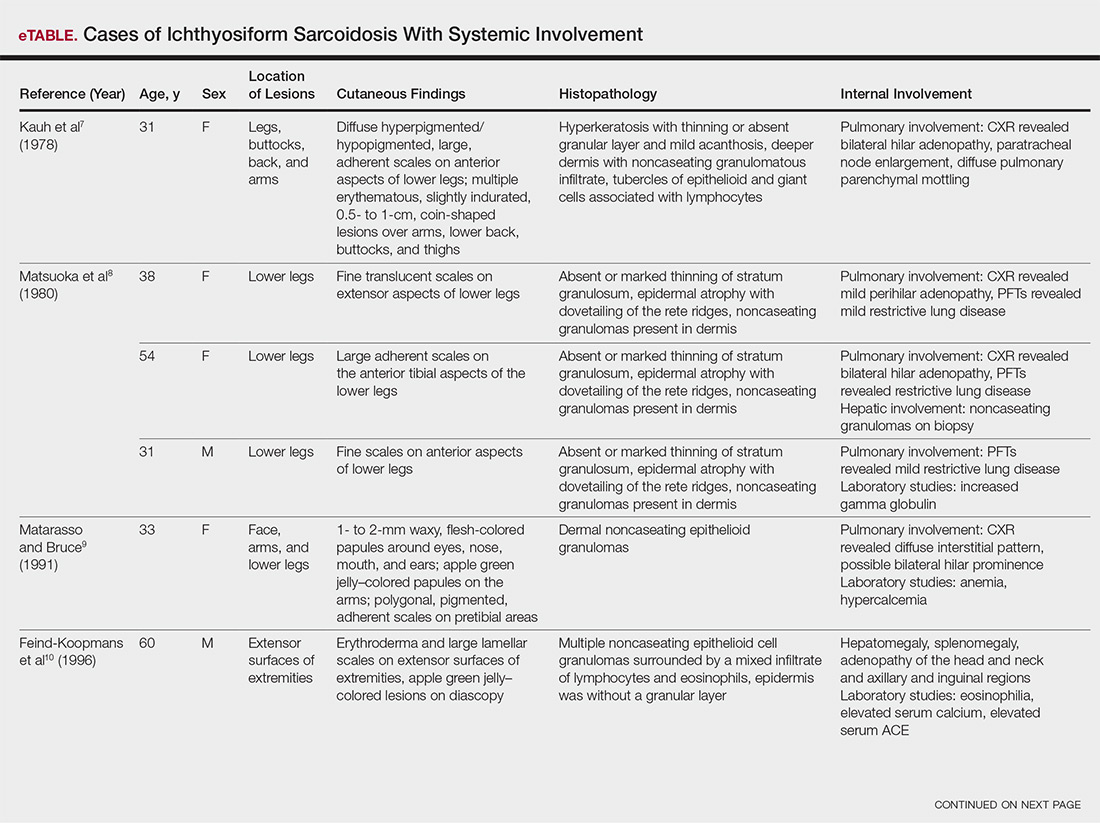

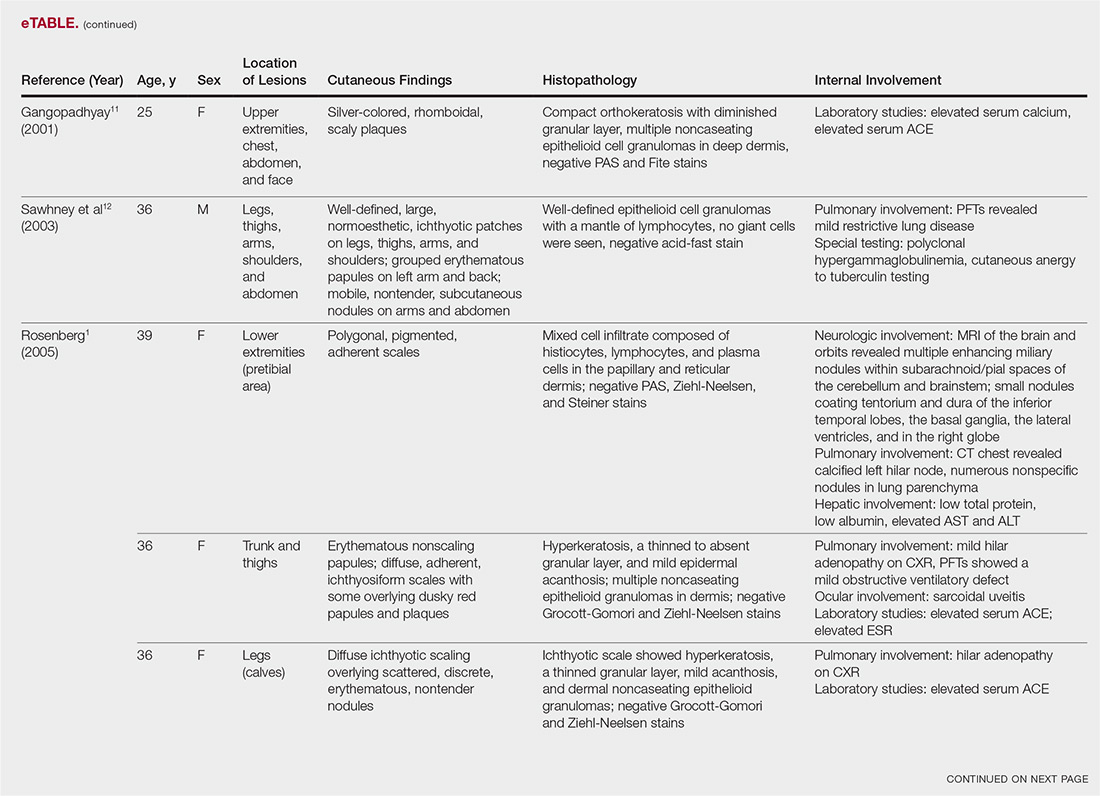

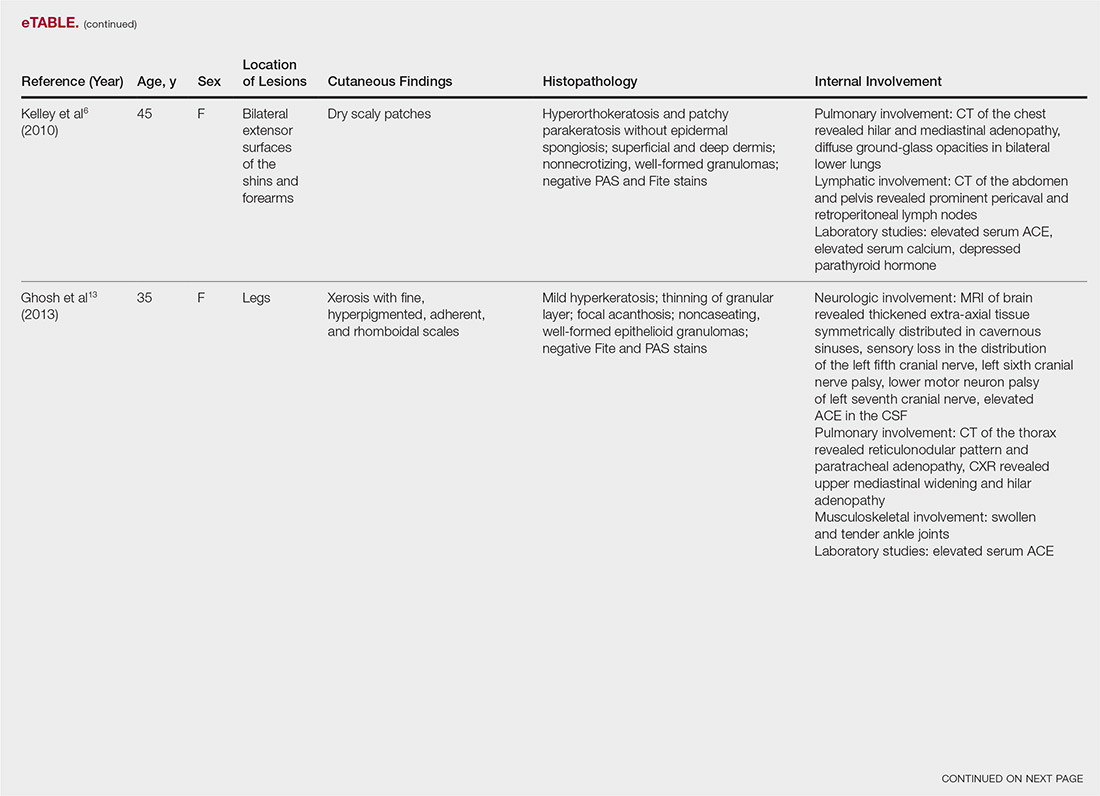

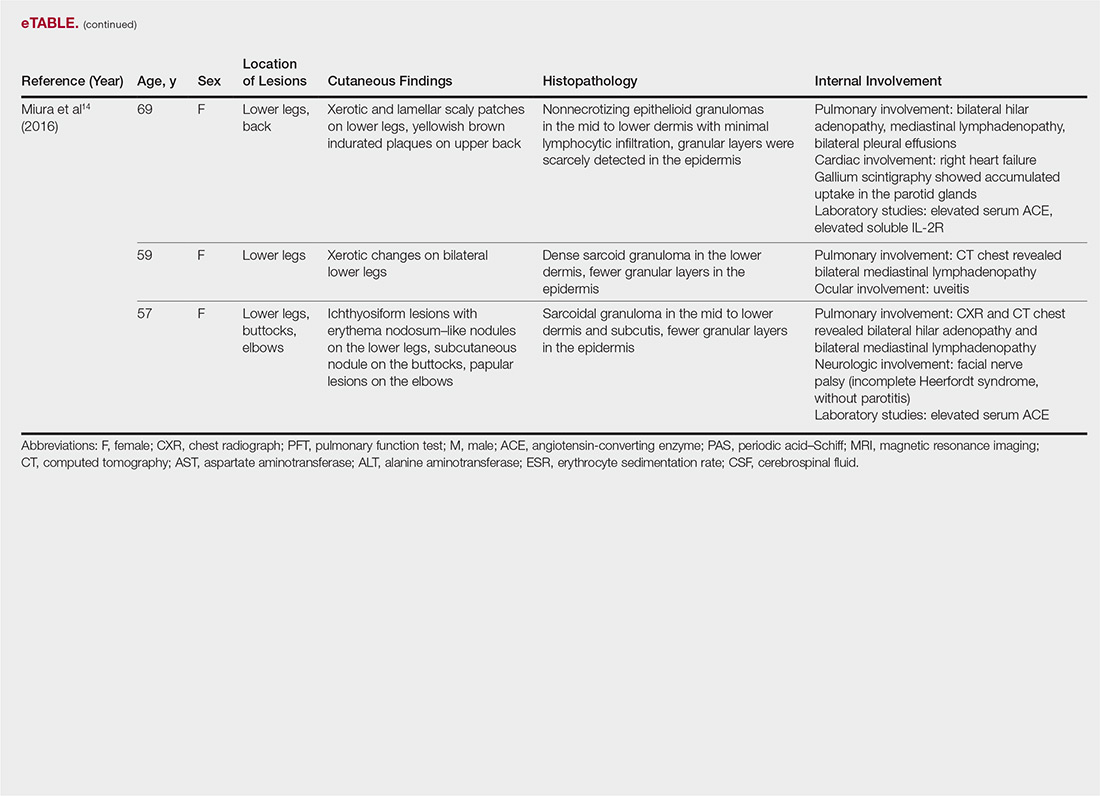

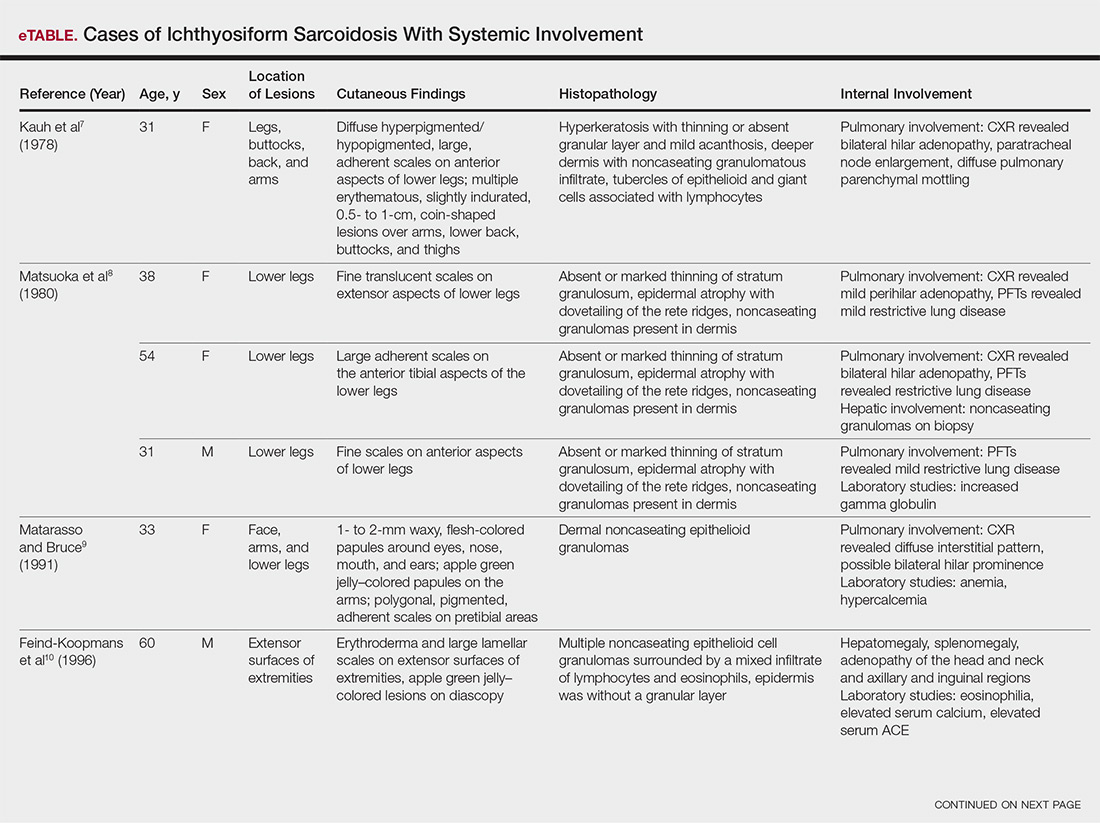

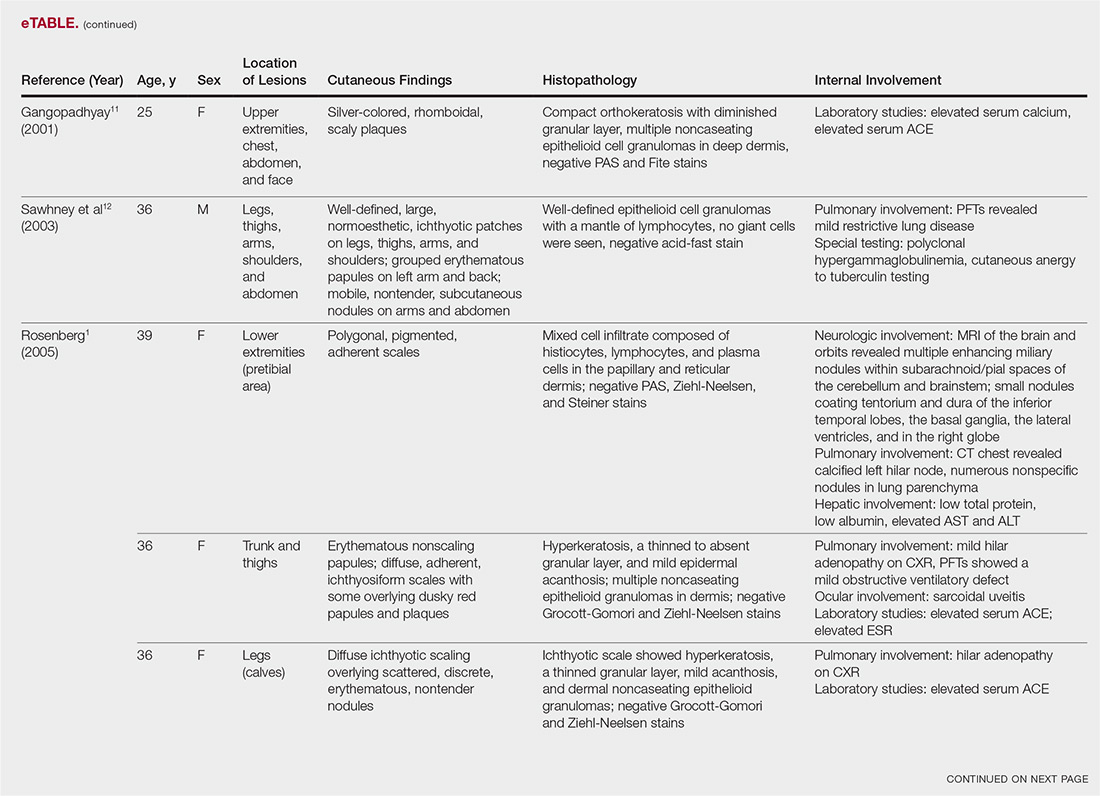

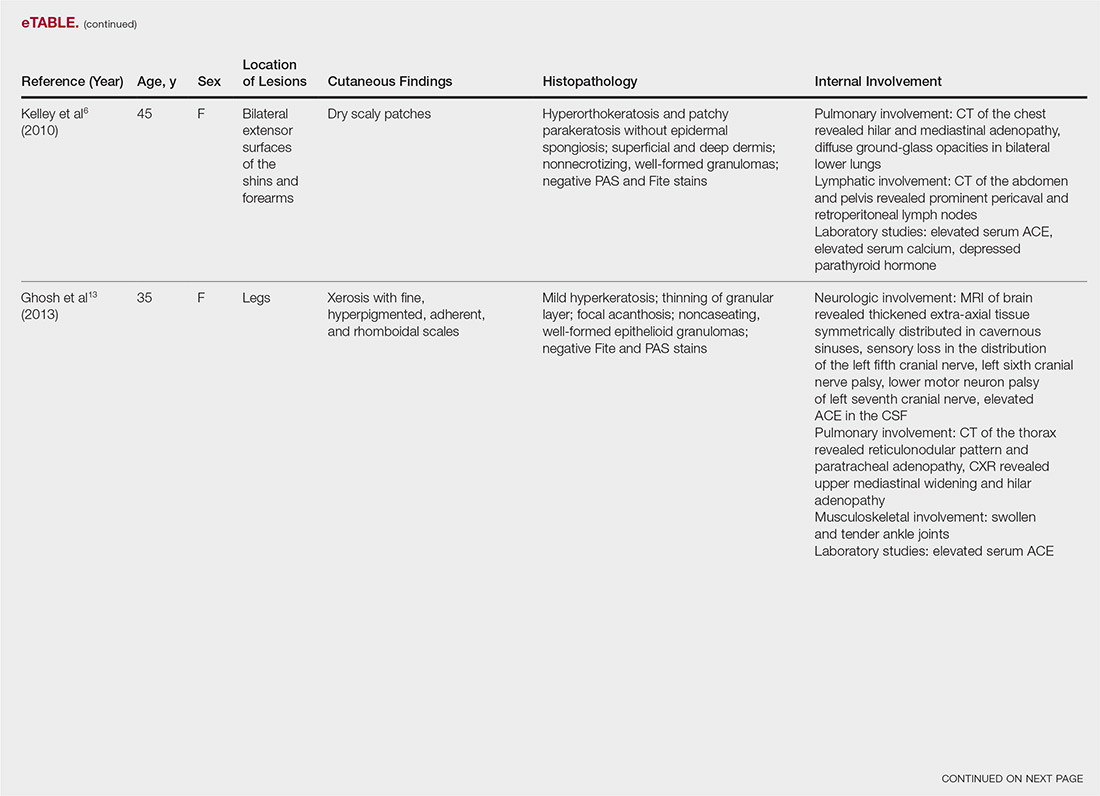

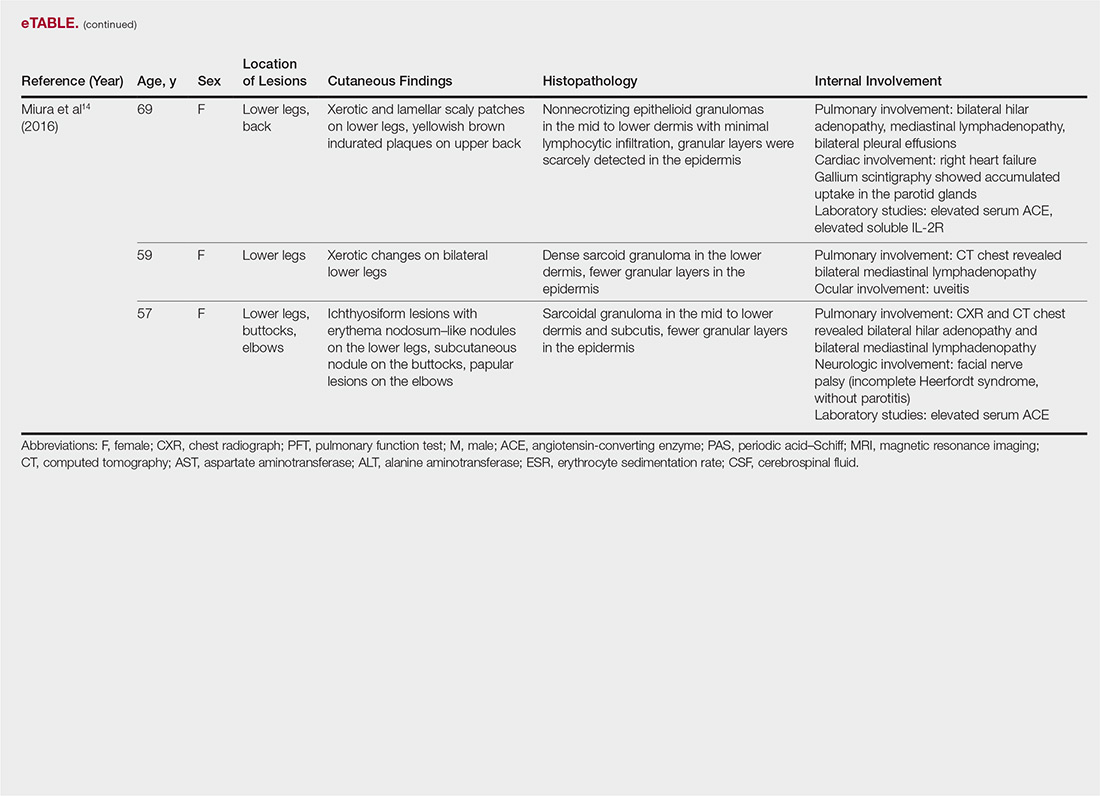

The most common site of internal sarcoid involvement is the lungs, but the lymph nodes, eyes, liver, spleen, heart, and central nervous system also can be involved. Patients can present with nonspecific symptoms such as erythema nodosum in the skin, dyspnea, cough, chest pain, vision changes, enlarged lymph nodes, headaches, joint pain, fever, fatigue, weight loss, and malaise. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ichthyosiform sarcoidosis, 16 cases have been reported in the English-language literature (eTable).1,6-14 Of these 16 cases, 3 involved men and 13 involved women. The median age of a patient diagnosed with IS was 37 years. The respiratory system was found to be the most common organ system involved (14 of 16 patients), with hilar adenopathy and restrictive lung disease being the most common findings. Neurologic findings and hepatic involvement also were seen in 3 and 3 patients, respectively. Eight of 16 cases had an elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level. Details of systemic involvement in other cases of IS are listed in the eTable.

Management

Most patients are given topical corticosteroids for their cutaneous lesions, but patients with systemic involvement will likely need some type of systemic immunosuppressive therapy to control their disease. Systemic therapy often is warranted in IS because of reports of rapid progression. Our case differs from these prior reports in the relative stability of the disease at the last patient encounter. Systemic treatment commonly includes oral corticosteroids such as prednisone. Other options, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, pentoxifylline, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and infliximab, can be considered if other treatments fail.13 Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis patients should continue to have regular follow-up to monitor for disease progression.

Differential

When evaluating an acquired ichthyosis, dermatologists can consider other associations such as Hodgkin disease, hypothyroidism, multiple myeloma, carcinomatosis, and chronic malnutrition.1 Skin biopsy demonstrating granuloma formation also is not specific for sarcoidosis. Other etiologies, such as autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency disorders, infections, foreign body granulomas, neoplasms, and drug reactions, should be considered.15 All patients with acquired ichthyosis should undergo a thorough evaluation for internal involvement.

Conclusion

We presented a case of IS, a rare type of sarcoidosis commonly associated with further internal involvement of the respiratory, nervous, or hepatic organ systems. Recognition of an acquired form of ichthyosis and its potential disease associations, including sarcoidosis, is important to improve early detection of any internal disease, allowing prompt initiation of treatment.

- Rosenberg B. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Banse-Kupin L, Pelachyk JM. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:616-620.

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416.

- Celada LJ, Hawkins C, Drake WP. The etiologic role of infectious antigens in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:561-568.

- Fingerlin TE, Hamzeh N, Maier LA. Genetics of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:569-584.

- Kelley BP, George DE, LeLeux TM, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Kauh YC, Goody HE, Luscombe HA. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:100-101.

- Matsuoka LY, LeVine M, Glasser S, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoid. Cutis. 1980;25:188-189.

- Matarasso SL, Bruce S. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of a case. Cutis. 1991;47:405-408.

- Feind-Koopmans AG, Lucker GP, van de Kerkhof PC. Acquired ichthyosiform erythroderma and sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:826-828.

- Gangopadhyay AK. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:91-92.

- Sawhney M, Sharma YK, Gera V, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis following chemotherapy of Hodgkin’s disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:220-222.

- Ghosh UC, Ghosh SK, Hazra K, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis revisited. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:795-798.

- Miura T, Kato Y, Yamamoto T. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of three cases from Japan and literature review. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;33:392-397.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan, systemic, granulomatous disease that most commonly affects the cutaneous, pulmonary, ocular, and cardiac organ systems. Cutaneous involvement occurs in approximately 20% to 35% of patients, with approximately 25% of patients demonstrating only dermatologic findings.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a highly variable presentation. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis (IS) is a rare form of this disease that has been described as presenting as polygonal adherent scales.2 It often is associated with internal organ involvement. We present a case of IS without any organ system involvement at the time of diagnosis. A review of the English-language literature was performed to ascertain the internal organ associations most commonly reported with IS.

Case Report

A 66-year-old black woman presented to dermatology with dark scaly patches noted by her primary care physician to be present on both of the lower extremities. The patient believed they were present for at least 4 years. She described dark spots confined to the lower legs that had gradually increased in size. Review of systems was negative for fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, vision changes, cough, dyspnea, and joint pains, and there was no history of either personal or familial cutaneous diseases.

Physical examination revealed cutaneous patches of thin white scale with a sharp edge in arciform patterns on the lower extremities. Several of these patches were hyperpigmented and xerotic in appearance (Figure 1). The patches were limited to the lower legs, with no other lesions noted.

A punch biopsy of the skin on the right lower leg was performed. Histopathologic analysis showed epidermal compact hyperkeratosis with deep granulomatous infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue (Figures 2A and 2B). At high power, these granulomas were noted to be noncaseating naked granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes surrounded by sparse lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2C). Special stains including acid-fast bacilli, Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff were negative. The diagnosis of IS was made based on clinical presentation and primarily by histopathologic analysis.

The patient’s cutaneous lesions were treated with fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily. Although she did not notice a dramatic improvement in the plaques, they stabilized in size. Her primary care physician was notified and advised to begin a workup for involvement of other organ systems by sarcoidosis. Her initial evaluation, which included a chest radiograph and electrocardiogram, were unremarkable. Despite multiple attempts to persuade the patient to return for further follow-up, neither dermatology nor her primary care physician were able to complete a full workup.

Comment

Etiology

Although there are several theories regarding the etiology of sarcoidosis, the exact cause remains unknown. The body’s immune response, infectious agents, genetics, and the environment have all been thought to play a role. It has been well established that helper T cell (TH1) production of interferon and increased levels of tumor necrosis factor propagate the inflammatory response seen in sarcoidosis.3 More recently, TH17 cells have been found in cutaneous lesions, bronchoalveolar lavage samples, and the blood of patients with sarcoidosis, especially in those with active disease progression.3 Infectious agents such as mycobacteria and propionibacteria DNA or RNA also have been found in sarcoid samples.4 Several HLA-DRB1 variants have been associated with an increased incidence of sarcoidosis.5

Presentation

Characteristic dermatologic findings of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, nodules, and plaques located on the face, especially the nose, cheeks, and ears, and on the shins or ankles, as well as similar lesions around tattoos or scars. Sarcoid lesions also have been described as angiolupoid, lichenoid, annular, verrucous, ulcerative, and psoriasiform. Here we present an example of the uncommon type, ichthyosiform. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis is a rare variant described primarily in dark-skinned individuals, a finding supported by both our case and prior reports. Most reported cases have described IS lesions as having a pasted-on appearance, with adherent centers on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, head, and/or neck.6 Our case follows this descriptive pattern previously reported with adherent patches limited to the lower extremities.

Histopathology

The key histopathologic finding is the presence of noncaseating granulomas on biopsy. Sarcoid “specific” lesions rest on the identification of the noncaseating granulomas, while “nonspecific” lesions such as erythema nodosum fail to demonstrate this finding.1

Systemic Involvement

The IS type is believed to be an excellent marker for systemic disease, with approximately 95% of reported cases having some form of systemic illness.6 Acquired ichthyosis should warrant further investigation for systemic disease. Early recognition could be beneficial for the patient because the ichthyosiform type is believed to precede the diagnosis of systemic disease in most cases by a median of 3 months.6

The most common site of internal sarcoid involvement is the lungs, but the lymph nodes, eyes, liver, spleen, heart, and central nervous system also can be involved. Patients can present with nonspecific symptoms such as erythema nodosum in the skin, dyspnea, cough, chest pain, vision changes, enlarged lymph nodes, headaches, joint pain, fever, fatigue, weight loss, and malaise. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ichthyosiform sarcoidosis, 16 cases have been reported in the English-language literature (eTable).1,6-14 Of these 16 cases, 3 involved men and 13 involved women. The median age of a patient diagnosed with IS was 37 years. The respiratory system was found to be the most common organ system involved (14 of 16 patients), with hilar adenopathy and restrictive lung disease being the most common findings. Neurologic findings and hepatic involvement also were seen in 3 and 3 patients, respectively. Eight of 16 cases had an elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level. Details of systemic involvement in other cases of IS are listed in the eTable.

Management

Most patients are given topical corticosteroids for their cutaneous lesions, but patients with systemic involvement will likely need some type of systemic immunosuppressive therapy to control their disease. Systemic therapy often is warranted in IS because of reports of rapid progression. Our case differs from these prior reports in the relative stability of the disease at the last patient encounter. Systemic treatment commonly includes oral corticosteroids such as prednisone. Other options, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, pentoxifylline, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and infliximab, can be considered if other treatments fail.13 Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis patients should continue to have regular follow-up to monitor for disease progression.

Differential

When evaluating an acquired ichthyosis, dermatologists can consider other associations such as Hodgkin disease, hypothyroidism, multiple myeloma, carcinomatosis, and chronic malnutrition.1 Skin biopsy demonstrating granuloma formation also is not specific for sarcoidosis. Other etiologies, such as autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency disorders, infections, foreign body granulomas, neoplasms, and drug reactions, should be considered.15 All patients with acquired ichthyosis should undergo a thorough evaluation for internal involvement.

Conclusion

We presented a case of IS, a rare type of sarcoidosis commonly associated with further internal involvement of the respiratory, nervous, or hepatic organ systems. Recognition of an acquired form of ichthyosis and its potential disease associations, including sarcoidosis, is important to improve early detection of any internal disease, allowing prompt initiation of treatment.

Sarcoidosis is a multiorgan, systemic, granulomatous disease that most commonly affects the cutaneous, pulmonary, ocular, and cardiac organ systems. Cutaneous involvement occurs in approximately 20% to 35% of patients, with approximately 25% of patients demonstrating only dermatologic findings.1 Cutaneous sarcoidosis can have a highly variable presentation. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis (IS) is a rare form of this disease that has been described as presenting as polygonal adherent scales.2 It often is associated with internal organ involvement. We present a case of IS without any organ system involvement at the time of diagnosis. A review of the English-language literature was performed to ascertain the internal organ associations most commonly reported with IS.

Case Report

A 66-year-old black woman presented to dermatology with dark scaly patches noted by her primary care physician to be present on both of the lower extremities. The patient believed they were present for at least 4 years. She described dark spots confined to the lower legs that had gradually increased in size. Review of systems was negative for fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, vision changes, cough, dyspnea, and joint pains, and there was no history of either personal or familial cutaneous diseases.

Physical examination revealed cutaneous patches of thin white scale with a sharp edge in arciform patterns on the lower extremities. Several of these patches were hyperpigmented and xerotic in appearance (Figure 1). The patches were limited to the lower legs, with no other lesions noted.

A punch biopsy of the skin on the right lower leg was performed. Histopathologic analysis showed epidermal compact hyperkeratosis with deep granulomatous infiltration into the subcutaneous tissue (Figures 2A and 2B). At high power, these granulomas were noted to be noncaseating naked granulomas composed of epithelioid histiocytes surrounded by sparse lymphocytic inflammation (Figure 2C). Special stains including acid-fast bacilli, Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff were negative. The diagnosis of IS was made based on clinical presentation and primarily by histopathologic analysis.

The patient’s cutaneous lesions were treated with fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily. Although she did not notice a dramatic improvement in the plaques, they stabilized in size. Her primary care physician was notified and advised to begin a workup for involvement of other organ systems by sarcoidosis. Her initial evaluation, which included a chest radiograph and electrocardiogram, were unremarkable. Despite multiple attempts to persuade the patient to return for further follow-up, neither dermatology nor her primary care physician were able to complete a full workup.

Comment

Etiology

Although there are several theories regarding the etiology of sarcoidosis, the exact cause remains unknown. The body’s immune response, infectious agents, genetics, and the environment have all been thought to play a role. It has been well established that helper T cell (TH1) production of interferon and increased levels of tumor necrosis factor propagate the inflammatory response seen in sarcoidosis.3 More recently, TH17 cells have been found in cutaneous lesions, bronchoalveolar lavage samples, and the blood of patients with sarcoidosis, especially in those with active disease progression.3 Infectious agents such as mycobacteria and propionibacteria DNA or RNA also have been found in sarcoid samples.4 Several HLA-DRB1 variants have been associated with an increased incidence of sarcoidosis.5

Presentation

Characteristic dermatologic findings of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, nodules, and plaques located on the face, especially the nose, cheeks, and ears, and on the shins or ankles, as well as similar lesions around tattoos or scars. Sarcoid lesions also have been described as angiolupoid, lichenoid, annular, verrucous, ulcerative, and psoriasiform. Here we present an example of the uncommon type, ichthyosiform. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis is a rare variant described primarily in dark-skinned individuals, a finding supported by both our case and prior reports. Most reported cases have described IS lesions as having a pasted-on appearance, with adherent centers on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, head, and/or neck.6 Our case follows this descriptive pattern previously reported with adherent patches limited to the lower extremities.

Histopathology

The key histopathologic finding is the presence of noncaseating granulomas on biopsy. Sarcoid “specific” lesions rest on the identification of the noncaseating granulomas, while “nonspecific” lesions such as erythema nodosum fail to demonstrate this finding.1

Systemic Involvement

The IS type is believed to be an excellent marker for systemic disease, with approximately 95% of reported cases having some form of systemic illness.6 Acquired ichthyosis should warrant further investigation for systemic disease. Early recognition could be beneficial for the patient because the ichthyosiform type is believed to precede the diagnosis of systemic disease in most cases by a median of 3 months.6

The most common site of internal sarcoid involvement is the lungs, but the lymph nodes, eyes, liver, spleen, heart, and central nervous system also can be involved. Patients can present with nonspecific symptoms such as erythema nodosum in the skin, dyspnea, cough, chest pain, vision changes, enlarged lymph nodes, headaches, joint pain, fever, fatigue, weight loss, and malaise. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term ichthyosiform sarcoidosis, 16 cases have been reported in the English-language literature (eTable).1,6-14 Of these 16 cases, 3 involved men and 13 involved women. The median age of a patient diagnosed with IS was 37 years. The respiratory system was found to be the most common organ system involved (14 of 16 patients), with hilar adenopathy and restrictive lung disease being the most common findings. Neurologic findings and hepatic involvement also were seen in 3 and 3 patients, respectively. Eight of 16 cases had an elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level. Details of systemic involvement in other cases of IS are listed in the eTable.

Management

Most patients are given topical corticosteroids for their cutaneous lesions, but patients with systemic involvement will likely need some type of systemic immunosuppressive therapy to control their disease. Systemic therapy often is warranted in IS because of reports of rapid progression. Our case differs from these prior reports in the relative stability of the disease at the last patient encounter. Systemic treatment commonly includes oral corticosteroids such as prednisone. Other options, such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, azathioprine, pentoxifylline, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and infliximab, can be considered if other treatments fail.13 Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis patients should continue to have regular follow-up to monitor for disease progression.

Differential

When evaluating an acquired ichthyosis, dermatologists can consider other associations such as Hodgkin disease, hypothyroidism, multiple myeloma, carcinomatosis, and chronic malnutrition.1 Skin biopsy demonstrating granuloma formation also is not specific for sarcoidosis. Other etiologies, such as autoimmune diseases, immunodeficiency disorders, infections, foreign body granulomas, neoplasms, and drug reactions, should be considered.15 All patients with acquired ichthyosis should undergo a thorough evaluation for internal involvement.

Conclusion

We presented a case of IS, a rare type of sarcoidosis commonly associated with further internal involvement of the respiratory, nervous, or hepatic organ systems. Recognition of an acquired form of ichthyosis and its potential disease associations, including sarcoidosis, is important to improve early detection of any internal disease, allowing prompt initiation of treatment.

- Rosenberg B. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Banse-Kupin L, Pelachyk JM. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:616-620.

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416.

- Celada LJ, Hawkins C, Drake WP. The etiologic role of infectious antigens in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:561-568.

- Fingerlin TE, Hamzeh N, Maier LA. Genetics of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:569-584.

- Kelley BP, George DE, LeLeux TM, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Kauh YC, Goody HE, Luscombe HA. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:100-101.

- Matsuoka LY, LeVine M, Glasser S, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoid. Cutis. 1980;25:188-189.

- Matarasso SL, Bruce S. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of a case. Cutis. 1991;47:405-408.

- Feind-Koopmans AG, Lucker GP, van de Kerkhof PC. Acquired ichthyosiform erythroderma and sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:826-828.

- Gangopadhyay AK. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:91-92.

- Sawhney M, Sharma YK, Gera V, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis following chemotherapy of Hodgkin’s disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:220-222.

- Ghosh UC, Ghosh SK, Hazra K, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis revisited. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:795-798.

- Miura T, Kato Y, Yamamoto T. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of three cases from Japan and literature review. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;33:392-397.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

- Rosenberg B. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Banse-Kupin L, Pelachyk JM. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:616-620.

- Sanchez M, Haimovic A, Prystowsky S. Sarcoidosis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:389-416.

- Celada LJ, Hawkins C, Drake WP. The etiologic role of infectious antigens in sarcoidosis pathogenesis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:561-568.

- Fingerlin TE, Hamzeh N, Maier LA. Genetics of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:569-584.

- Kelley BP, George DE, LeLeux TM, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Kauh YC, Goody HE, Luscombe HA. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:100-101.

- Matsuoka LY, LeVine M, Glasser S, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoid. Cutis. 1980;25:188-189.

- Matarasso SL, Bruce S. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of a case. Cutis. 1991;47:405-408.

- Feind-Koopmans AG, Lucker GP, van de Kerkhof PC. Acquired ichthyosiform erythroderma and sarcoidosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:826-828.

- Gangopadhyay AK. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2001;67:91-92.

- Sawhney M, Sharma YK, Gera V, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis following chemotherapy of Hodgkin’s disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:220-222.

- Ghosh UC, Ghosh SK, Hazra K, et al. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis revisited. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:795-798.

- Miura T, Kato Y, Yamamoto T. Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis: report of three cases from Japan and literature review. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2016;33:392-397.

- Fernandez-Faith E, McDonnell J. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: differential diagnosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:276-287.

Practice Points

- Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis is a rare form of sarcoidosis that presents as polygonal adherent scales.

- Ichthyosiform sarcoidosis is commonly associated with pulmonary, neurologic, and hepatic involvement.

- Acquired ichthyosis should warrant further investigation for systemic disease.