User login

Beauty sleep: Sleep deprivation and the skin

There are many, many, short-term and long-term consequences of sleep deprivation. The most clinically apparent ones – swollen, sunken eyes; dark circles; and pale, dehydrated skin – are obvious. However the subclinical consequences are not so obvious. Sleep deprivation affects wound healing, collagen growth, skin hydration, and skin texture. Inflammation is also higher in sleep-deprived patients, causing outbreaks of acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin allergies.

The reduction of sleep time affects the composition and integrity of the skin. Sleep deprivation increases glucocorticoid production. The elevation of cortisol inhibits fibroblast function and increases matrix metalloproteinases (collagenase, gelatinase). Matrix metalloproteinases accelerate collagen and elastin breakdown, which is essential to skin integrity, and hastens the aging process by increasing wrinkles, decreasing skin thickness, inhibiting growth factors, and decreasing skin elasticity.

Are there treatments to reverse these signs? Yes. Treatments to help increase skin collagen production include microneedling, radiofrequency devices, fractionated lasers, and topical agents such as retinoids. However, we cannot readily reverse the impact inflammatory processes, skin barrier dysfunction, or the disruption of the skin biome has on our skin. Beauty sleep is both necessary and irreplaceable.

References

1. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):R1148-54.

2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):R905-16.

3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Feb;288(2):R374-83.

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):R504-9.

5. Med Hypotheses. 2010 Dec;75(6):535-7.

6. Sleep. 2013 Sep 1;36(9):1355-60.

7. BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6614.

8. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 Nov;23(8):1089-95.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

There are many, many, short-term and long-term consequences of sleep deprivation. The most clinically apparent ones – swollen, sunken eyes; dark circles; and pale, dehydrated skin – are obvious. However the subclinical consequences are not so obvious. Sleep deprivation affects wound healing, collagen growth, skin hydration, and skin texture. Inflammation is also higher in sleep-deprived patients, causing outbreaks of acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin allergies.

The reduction of sleep time affects the composition and integrity of the skin. Sleep deprivation increases glucocorticoid production. The elevation of cortisol inhibits fibroblast function and increases matrix metalloproteinases (collagenase, gelatinase). Matrix metalloproteinases accelerate collagen and elastin breakdown, which is essential to skin integrity, and hastens the aging process by increasing wrinkles, decreasing skin thickness, inhibiting growth factors, and decreasing skin elasticity.

Are there treatments to reverse these signs? Yes. Treatments to help increase skin collagen production include microneedling, radiofrequency devices, fractionated lasers, and topical agents such as retinoids. However, we cannot readily reverse the impact inflammatory processes, skin barrier dysfunction, or the disruption of the skin biome has on our skin. Beauty sleep is both necessary and irreplaceable.

References

1. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):R1148-54.

2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):R905-16.

3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Feb;288(2):R374-83.

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):R504-9.

5. Med Hypotheses. 2010 Dec;75(6):535-7.

6. Sleep. 2013 Sep 1;36(9):1355-60.

7. BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6614.

8. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 Nov;23(8):1089-95.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

There are many, many, short-term and long-term consequences of sleep deprivation. The most clinically apparent ones – swollen, sunken eyes; dark circles; and pale, dehydrated skin – are obvious. However the subclinical consequences are not so obvious. Sleep deprivation affects wound healing, collagen growth, skin hydration, and skin texture. Inflammation is also higher in sleep-deprived patients, causing outbreaks of acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin allergies.

The reduction of sleep time affects the composition and integrity of the skin. Sleep deprivation increases glucocorticoid production. The elevation of cortisol inhibits fibroblast function and increases matrix metalloproteinases (collagenase, gelatinase). Matrix metalloproteinases accelerate collagen and elastin breakdown, which is essential to skin integrity, and hastens the aging process by increasing wrinkles, decreasing skin thickness, inhibiting growth factors, and decreasing skin elasticity.

Are there treatments to reverse these signs? Yes. Treatments to help increase skin collagen production include microneedling, radiofrequency devices, fractionated lasers, and topical agents such as retinoids. However, we cannot readily reverse the impact inflammatory processes, skin barrier dysfunction, or the disruption of the skin biome has on our skin. Beauty sleep is both necessary and irreplaceable.

References

1. Am J Physiol. 1993 Nov;265(5 Pt 2):R1148-54.

2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000 Apr;278(4):R905-16.

3. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005 Feb;288(2):R374-83.

4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007 Jul;293(1):R504-9.

5. Med Hypotheses. 2010 Dec;75(6):535-7.

6. Sleep. 2013 Sep 1;36(9):1355-60.

7. BMJ. 2010 Dec 14;341:c6614.

8. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 Nov;23(8):1089-95.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

Cannulas versus needles for soft tissue filler injection

With loss of deep fat pad compartments and bony resorption with normal aging, soft tissue fillers have become a mainstay in minimally invasive aesthetic treatments. Preference of injecting with a needle versus a cannula is often user and training dependent. Blunt-tipped cannulas may provide a lower risk of bruising, as well as potentially devastating complications such as intravascular occlusion that can lead to skin necrosis and blindness. Even for advanced injectors, however, cannula use may portend a learning curve if the clinicians are used to injecting with needles.

A recently published observational study using cadaver heads looked at precision in supraperiosteal placement with a sharp needle compared with a blunt tipped cannula.1 The investigators injected dye material with soft-tissue fillers at different aesthetic facial sites on the supraperiosteum, then observed the placement of dye and filler after dissection. In this study, the placement of product was more precise with the cannulas. The filler was injected on the periosteum with a needle. Some of the filler then migrated along the trajectory of the needle path back toward the epidermis, ending up in multiple tissue layers. So there was more extrusion of the filler in the superficial layers with a needle without a retrograde injection technique. Even with the needle tip on the periosteum and no movement of the needle, the needle technique showed a higher risk of intra-arterial injections. This study is limited by the fact that in vivo circumstances could potentially alter the outcome, as could user injection technique.

Cannulas should be highly considered in any deep tissue compartment, but especially in more advanced injection technique areas, such as the nasal dorsum. Another cadaver study from Thailand showed that the anatomy of the dorsal nasal artery is not consistent.2 It is injection into this artery that can lead to blindness via flow to the ophthalmic artery. The study showed that both the diameter of the artery and the presence of a single or bilateral dorsal nasal artery varied. The dorsal nasal artery travels in the subcutaneous tissue layer of the nasal dorsum on the transverse nasalis muscle and its midline nasal aponeurosis, which connects the muscles on both sides. Bilateral dorsal nasal arteries were present in 34% of the specimens. A single and large dorsal nasal artery was present in 28%.

Needles are still useful in some places where precise small aliquot touch-up of filler placement is needed or where it may be difficult to reach with the cannula without making an additional portal of entry. More viscous fillers such as calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L-lactic acid can be difficult to inject through a cannula and require a needle for injection. More superficially, small 30- or 32-gauge needles are also required for the injection of certain hyaluronic acid fillers in the superficial dermis for more etched lines.

The risk of arterial wall perforation and emboli with cannulas is lower, but these complications can still occur. The risk increases with a perpendicular angle between the artery and the cannula, thus slow small aliquot injection technique along with knowledge of anatomy is essential.3 While both needles and cannulas are useful in practice and achieve excellent cosmetic results, cannula use in the deeper compartments among practitioners is encouraged to minimize complications.

References

1. Aesthet Surg J. 2016 Dec 16. pii: sjw220.

2. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 28. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0756-0.

3. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 23. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0725-7.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

With loss of deep fat pad compartments and bony resorption with normal aging, soft tissue fillers have become a mainstay in minimally invasive aesthetic treatments. Preference of injecting with a needle versus a cannula is often user and training dependent. Blunt-tipped cannulas may provide a lower risk of bruising, as well as potentially devastating complications such as intravascular occlusion that can lead to skin necrosis and blindness. Even for advanced injectors, however, cannula use may portend a learning curve if the clinicians are used to injecting with needles.

A recently published observational study using cadaver heads looked at precision in supraperiosteal placement with a sharp needle compared with a blunt tipped cannula.1 The investigators injected dye material with soft-tissue fillers at different aesthetic facial sites on the supraperiosteum, then observed the placement of dye and filler after dissection. In this study, the placement of product was more precise with the cannulas. The filler was injected on the periosteum with a needle. Some of the filler then migrated along the trajectory of the needle path back toward the epidermis, ending up in multiple tissue layers. So there was more extrusion of the filler in the superficial layers with a needle without a retrograde injection technique. Even with the needle tip on the periosteum and no movement of the needle, the needle technique showed a higher risk of intra-arterial injections. This study is limited by the fact that in vivo circumstances could potentially alter the outcome, as could user injection technique.

Cannulas should be highly considered in any deep tissue compartment, but especially in more advanced injection technique areas, such as the nasal dorsum. Another cadaver study from Thailand showed that the anatomy of the dorsal nasal artery is not consistent.2 It is injection into this artery that can lead to blindness via flow to the ophthalmic artery. The study showed that both the diameter of the artery and the presence of a single or bilateral dorsal nasal artery varied. The dorsal nasal artery travels in the subcutaneous tissue layer of the nasal dorsum on the transverse nasalis muscle and its midline nasal aponeurosis, which connects the muscles on both sides. Bilateral dorsal nasal arteries were present in 34% of the specimens. A single and large dorsal nasal artery was present in 28%.

Needles are still useful in some places where precise small aliquot touch-up of filler placement is needed or where it may be difficult to reach with the cannula without making an additional portal of entry. More viscous fillers such as calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L-lactic acid can be difficult to inject through a cannula and require a needle for injection. More superficially, small 30- or 32-gauge needles are also required for the injection of certain hyaluronic acid fillers in the superficial dermis for more etched lines.

The risk of arterial wall perforation and emboli with cannulas is lower, but these complications can still occur. The risk increases with a perpendicular angle between the artery and the cannula, thus slow small aliquot injection technique along with knowledge of anatomy is essential.3 While both needles and cannulas are useful in practice and achieve excellent cosmetic results, cannula use in the deeper compartments among practitioners is encouraged to minimize complications.

References

1. Aesthet Surg J. 2016 Dec 16. pii: sjw220.

2. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 28. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0756-0.

3. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 23. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0725-7.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

With loss of deep fat pad compartments and bony resorption with normal aging, soft tissue fillers have become a mainstay in minimally invasive aesthetic treatments. Preference of injecting with a needle versus a cannula is often user and training dependent. Blunt-tipped cannulas may provide a lower risk of bruising, as well as potentially devastating complications such as intravascular occlusion that can lead to skin necrosis and blindness. Even for advanced injectors, however, cannula use may portend a learning curve if the clinicians are used to injecting with needles.

A recently published observational study using cadaver heads looked at precision in supraperiosteal placement with a sharp needle compared with a blunt tipped cannula.1 The investigators injected dye material with soft-tissue fillers at different aesthetic facial sites on the supraperiosteum, then observed the placement of dye and filler after dissection. In this study, the placement of product was more precise with the cannulas. The filler was injected on the periosteum with a needle. Some of the filler then migrated along the trajectory of the needle path back toward the epidermis, ending up in multiple tissue layers. So there was more extrusion of the filler in the superficial layers with a needle without a retrograde injection technique. Even with the needle tip on the periosteum and no movement of the needle, the needle technique showed a higher risk of intra-arterial injections. This study is limited by the fact that in vivo circumstances could potentially alter the outcome, as could user injection technique.

Cannulas should be highly considered in any deep tissue compartment, but especially in more advanced injection technique areas, such as the nasal dorsum. Another cadaver study from Thailand showed that the anatomy of the dorsal nasal artery is not consistent.2 It is injection into this artery that can lead to blindness via flow to the ophthalmic artery. The study showed that both the diameter of the artery and the presence of a single or bilateral dorsal nasal artery varied. The dorsal nasal artery travels in the subcutaneous tissue layer of the nasal dorsum on the transverse nasalis muscle and its midline nasal aponeurosis, which connects the muscles on both sides. Bilateral dorsal nasal arteries were present in 34% of the specimens. A single and large dorsal nasal artery was present in 28%.

Needles are still useful in some places where precise small aliquot touch-up of filler placement is needed or where it may be difficult to reach with the cannula without making an additional portal of entry. More viscous fillers such as calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L-lactic acid can be difficult to inject through a cannula and require a needle for injection. More superficially, small 30- or 32-gauge needles are also required for the injection of certain hyaluronic acid fillers in the superficial dermis for more etched lines.

The risk of arterial wall perforation and emboli with cannulas is lower, but these complications can still occur. The risk increases with a perpendicular angle between the artery and the cannula, thus slow small aliquot injection technique along with knowledge of anatomy is essential.3 While both needles and cannulas are useful in practice and achieve excellent cosmetic results, cannula use in the deeper compartments among practitioners is encouraged to minimize complications.

References

1. Aesthet Surg J. 2016 Dec 16. pii: sjw220.

2. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 28. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0756-0.

3. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 23. doi: 10.1007/s00266-016-0725-7.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

The hidden vascular component to melasma

So lets revisit this topic. We hate melasma. It is recalcitrant, resistant, and often recurs. But how many of us dermatologists look at melasma with a dermatoscope? A minority? And probably even fewer of us biopsy melasma. Are we missing the many, many cases of vascular or erythematotelangiectatic melasma and just treating melasma as a pigment problem instead of treating it as a vascular problem?

We know that melasma develops because of increased melanin production, not an increased number of melanocytes, but the underlying cause of increased melanogenesis is not fully understood. Several recent studies suggest that the increased vascularity in melasma skin is the underlying etiology. Understanding the way endogeneous and exogeneous stimuli such as sex hormones, oral contraceptives, ultraviolet irradiation, and visible light stimulate inflammation in the dermis, leading to the release of various mediators that stimulate angiogenesis and the activation of melanocytes, will help us improve the treatment of this relentless disease.

Similarly, elevated estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy or with oral contraceptive use is known to stimulate melasma. Melanocytes express estrogen receptors and estradiol increases the level of TRP-2, which stimulates melanocytes to produce melanin. Recent literature has shown that the number of blood vessels, vessel size, and vessel density also are greater in lesional melasma skin than in perilesional skin. In addition, immunohistochemical staining has shown an increased level of factor VIIIa-related antigen in blood vessels in melasma skin, compared with perilesional normal skin.

Unfortunately, the treatment of vascular melasma is very difficult. Lasers such as the pulsed dye laser that help skin vascularity can trigger worsening melanogenesis through dermal inflammation. The melanin cap overlying the melanocyte nucleus also can mask the underlying vascularity and make laser treatments more difficult. The isolated treatment of epidermal pigment also may be ineffective and transient.

By targeting the vessels in addition to the pigment, we will get improved clinical results and fewer relapses. We suggest that melasma be treated conservatively, not aggressively. It should be treated as an inflammatory process. Patients with melasma also have a slightly abnormal skin barrier, so we should be hesitant in using deep lasers, radio frequency, and aggressive chemical peels. Topical preparations – particularly triple-combination bleaching agents, retinoids, and nonhydroquinone skin lighteners – should be used sparingly and always in combination with treatments targeting skin vascularity.

References

J Dermatol Sci. 2007 May;46(2):111-6.

Exp Dermatol. 2005 Aug;14(8):625-33.

Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(3):305-8.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Nov;23(11):1254-62.

Ann Dermatol. 2010 Nov;22(4):373-8.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Jan;27 Suppl 1:5-6.

Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013 Oct;14(5):359-76.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb;70(2):369-73.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

So lets revisit this topic. We hate melasma. It is recalcitrant, resistant, and often recurs. But how many of us dermatologists look at melasma with a dermatoscope? A minority? And probably even fewer of us biopsy melasma. Are we missing the many, many cases of vascular or erythematotelangiectatic melasma and just treating melasma as a pigment problem instead of treating it as a vascular problem?

We know that melasma develops because of increased melanin production, not an increased number of melanocytes, but the underlying cause of increased melanogenesis is not fully understood. Several recent studies suggest that the increased vascularity in melasma skin is the underlying etiology. Understanding the way endogeneous and exogeneous stimuli such as sex hormones, oral contraceptives, ultraviolet irradiation, and visible light stimulate inflammation in the dermis, leading to the release of various mediators that stimulate angiogenesis and the activation of melanocytes, will help us improve the treatment of this relentless disease.

Similarly, elevated estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy or with oral contraceptive use is known to stimulate melasma. Melanocytes express estrogen receptors and estradiol increases the level of TRP-2, which stimulates melanocytes to produce melanin. Recent literature has shown that the number of blood vessels, vessel size, and vessel density also are greater in lesional melasma skin than in perilesional skin. In addition, immunohistochemical staining has shown an increased level of factor VIIIa-related antigen in blood vessels in melasma skin, compared with perilesional normal skin.

Unfortunately, the treatment of vascular melasma is very difficult. Lasers such as the pulsed dye laser that help skin vascularity can trigger worsening melanogenesis through dermal inflammation. The melanin cap overlying the melanocyte nucleus also can mask the underlying vascularity and make laser treatments more difficult. The isolated treatment of epidermal pigment also may be ineffective and transient.

By targeting the vessels in addition to the pigment, we will get improved clinical results and fewer relapses. We suggest that melasma be treated conservatively, not aggressively. It should be treated as an inflammatory process. Patients with melasma also have a slightly abnormal skin barrier, so we should be hesitant in using deep lasers, radio frequency, and aggressive chemical peels. Topical preparations – particularly triple-combination bleaching agents, retinoids, and nonhydroquinone skin lighteners – should be used sparingly and always in combination with treatments targeting skin vascularity.

References

J Dermatol Sci. 2007 May;46(2):111-6.

Exp Dermatol. 2005 Aug;14(8):625-33.

Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(3):305-8.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Nov;23(11):1254-62.

Ann Dermatol. 2010 Nov;22(4):373-8.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Jan;27 Suppl 1:5-6.

Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013 Oct;14(5):359-76.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb;70(2):369-73.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

So lets revisit this topic. We hate melasma. It is recalcitrant, resistant, and often recurs. But how many of us dermatologists look at melasma with a dermatoscope? A minority? And probably even fewer of us biopsy melasma. Are we missing the many, many cases of vascular or erythematotelangiectatic melasma and just treating melasma as a pigment problem instead of treating it as a vascular problem?

We know that melasma develops because of increased melanin production, not an increased number of melanocytes, but the underlying cause of increased melanogenesis is not fully understood. Several recent studies suggest that the increased vascularity in melasma skin is the underlying etiology. Understanding the way endogeneous and exogeneous stimuli such as sex hormones, oral contraceptives, ultraviolet irradiation, and visible light stimulate inflammation in the dermis, leading to the release of various mediators that stimulate angiogenesis and the activation of melanocytes, will help us improve the treatment of this relentless disease.

Similarly, elevated estrogen and progesterone in pregnancy or with oral contraceptive use is known to stimulate melasma. Melanocytes express estrogen receptors and estradiol increases the level of TRP-2, which stimulates melanocytes to produce melanin. Recent literature has shown that the number of blood vessels, vessel size, and vessel density also are greater in lesional melasma skin than in perilesional skin. In addition, immunohistochemical staining has shown an increased level of factor VIIIa-related antigen in blood vessels in melasma skin, compared with perilesional normal skin.

Unfortunately, the treatment of vascular melasma is very difficult. Lasers such as the pulsed dye laser that help skin vascularity can trigger worsening melanogenesis through dermal inflammation. The melanin cap overlying the melanocyte nucleus also can mask the underlying vascularity and make laser treatments more difficult. The isolated treatment of epidermal pigment also may be ineffective and transient.

By targeting the vessels in addition to the pigment, we will get improved clinical results and fewer relapses. We suggest that melasma be treated conservatively, not aggressively. It should be treated as an inflammatory process. Patients with melasma also have a slightly abnormal skin barrier, so we should be hesitant in using deep lasers, radio frequency, and aggressive chemical peels. Topical preparations – particularly triple-combination bleaching agents, retinoids, and nonhydroquinone skin lighteners – should be used sparingly and always in combination with treatments targeting skin vascularity.

References

J Dermatol Sci. 2007 May;46(2):111-6.

Exp Dermatol. 2005 Aug;14(8):625-33.

Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(3):305-8.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009 Nov;23(11):1254-62.

Ann Dermatol. 2010 Nov;22(4):373-8.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Jan;27 Suppl 1:5-6.

Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013 Oct;14(5):359-76.

J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Feb;70(2):369-73.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley and are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

Highlights from the ASDS Annual Conference 2016

At this year’s American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS) annual meeting, many of the hot topics pertained to tightening and smoothness of the skin. More naturally derived skin care products were discussed, as well as skin-tightening devices, techniques for improving fat, microneedling, devices for improving cellulite, and some of the newer injectable fillers on the market.

Of all of these, the use of microneedling with and without radiofrequency energy to improve acne scars, rhytids, and pore size was the most prominent emerging trend. Microneedling devices with radiofrequency also are being used for skin tightening, in addition to improving skin texture.

There were also presentations on improvements in acne scars with a number of techniques, including fractional ablative and nonablative lasers, subcision, microneedling, and fillers.

Controversies addressed at the meeting included whether or not dermatologists should use the same lasers with different Food and Drug Administration–approved hand pieces for vaginal rejuvenation. In addition, controversies over whether Mohs surgeons should undergo board examination were discussed.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected].

At this year’s American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS) annual meeting, many of the hot topics pertained to tightening and smoothness of the skin. More naturally derived skin care products were discussed, as well as skin-tightening devices, techniques for improving fat, microneedling, devices for improving cellulite, and some of the newer injectable fillers on the market.

Of all of these, the use of microneedling with and without radiofrequency energy to improve acne scars, rhytids, and pore size was the most prominent emerging trend. Microneedling devices with radiofrequency also are being used for skin tightening, in addition to improving skin texture.

There were also presentations on improvements in acne scars with a number of techniques, including fractional ablative and nonablative lasers, subcision, microneedling, and fillers.

Controversies addressed at the meeting included whether or not dermatologists should use the same lasers with different Food and Drug Administration–approved hand pieces for vaginal rejuvenation. In addition, controversies over whether Mohs surgeons should undergo board examination were discussed.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected].

At this year’s American Society for Dermatologic Surgery (ASDS) annual meeting, many of the hot topics pertained to tightening and smoothness of the skin. More naturally derived skin care products were discussed, as well as skin-tightening devices, techniques for improving fat, microneedling, devices for improving cellulite, and some of the newer injectable fillers on the market.

Of all of these, the use of microneedling with and without radiofrequency energy to improve acne scars, rhytids, and pore size was the most prominent emerging trend. Microneedling devices with radiofrequency also are being used for skin tightening, in addition to improving skin texture.

There were also presentations on improvements in acne scars with a number of techniques, including fractional ablative and nonablative lasers, subcision, microneedling, and fillers.

Controversies addressed at the meeting included whether or not dermatologists should use the same lasers with different Food and Drug Administration–approved hand pieces for vaginal rejuvenation. In addition, controversies over whether Mohs surgeons should undergo board examination were discussed.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected].

Postinflammatory erythema

The troubling, frustrating part of acne: the persistent acne scars that are often a prolonged battle for most of our patients. We have many techniques to deal with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). However, postinflammatory erythema (PIE), the erythematous scars often seen in acne and other inflammatory skin conditions, is not well understood. And despite its pervasive nature, very little data exist that identify its etiology and effective treatment options.

Inflammatory acne scars are not all the same. PIH, often seen with Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI, is related to brown spots, not red spots. Hyperpigmentation is caused by an excess production of melanin. There are treatments for PIH in our armamentarium – such as microdermabrasion, chemical peels, hydroquinone, and vitamin C – that inhibit melanogenesis and blend the skin discoloration.

In contrast, PIE is characterized by pink, red, and sometimes purple-appearing vascular neogenesis seen most often with skin types I-III after an inflammatory skin condition resolves, and is often seen in cystic acne.

The term postinflammatory erythema was initially introduced in the dermatology literature in 2013 by Bae-Harboe et al. to describe erythema often seen after the resolution of inflammatory acne or other inflammatory skin conditions.1 It is not to be confused with the erythema and telangiectasias seen in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, which is a separate entity.

In my practice, microneedling has also been effective in reducing PIE. Although this may seem counterintuitive because of the bleeding associated with the microneedling process, microneedling-induced skin tissue injury and neocollagenesis have been clinically shown to improve the abnormal vascular proliferation that occurs in PIE. Similar techniques can be used with fractional resurfacing lasers. However, no studies have specifically evaluated the erythematous component of acne scars treated with fractionated lasers.

Topical preparations containing brimonidine (Mirvaso), azelaic acid, and green tea, as well as oral nicotinamide, can have a temporary effect on reducing skin erythema.

However, very little data or clinical studies are available on treatments for PIE, and there are no well-studied preparations with long-term efficacy data. Studies are needed to provide better clinical guidelines for treatment methods and alternatives to treatments, including topical and systemic medications.

References

1. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Sep;6(9):46-7.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 May;60(5):801-7.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

The troubling, frustrating part of acne: the persistent acne scars that are often a prolonged battle for most of our patients. We have many techniques to deal with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). However, postinflammatory erythema (PIE), the erythematous scars often seen in acne and other inflammatory skin conditions, is not well understood. And despite its pervasive nature, very little data exist that identify its etiology and effective treatment options.

Inflammatory acne scars are not all the same. PIH, often seen with Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI, is related to brown spots, not red spots. Hyperpigmentation is caused by an excess production of melanin. There are treatments for PIH in our armamentarium – such as microdermabrasion, chemical peels, hydroquinone, and vitamin C – that inhibit melanogenesis and blend the skin discoloration.

In contrast, PIE is characterized by pink, red, and sometimes purple-appearing vascular neogenesis seen most often with skin types I-III after an inflammatory skin condition resolves, and is often seen in cystic acne.

The term postinflammatory erythema was initially introduced in the dermatology literature in 2013 by Bae-Harboe et al. to describe erythema often seen after the resolution of inflammatory acne or other inflammatory skin conditions.1 It is not to be confused with the erythema and telangiectasias seen in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, which is a separate entity.

In my practice, microneedling has also been effective in reducing PIE. Although this may seem counterintuitive because of the bleeding associated with the microneedling process, microneedling-induced skin tissue injury and neocollagenesis have been clinically shown to improve the abnormal vascular proliferation that occurs in PIE. Similar techniques can be used with fractional resurfacing lasers. However, no studies have specifically evaluated the erythematous component of acne scars treated with fractionated lasers.

Topical preparations containing brimonidine (Mirvaso), azelaic acid, and green tea, as well as oral nicotinamide, can have a temporary effect on reducing skin erythema.

However, very little data or clinical studies are available on treatments for PIE, and there are no well-studied preparations with long-term efficacy data. Studies are needed to provide better clinical guidelines for treatment methods and alternatives to treatments, including topical and systemic medications.

References

1. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Sep;6(9):46-7.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 May;60(5):801-7.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

The troubling, frustrating part of acne: the persistent acne scars that are often a prolonged battle for most of our patients. We have many techniques to deal with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). However, postinflammatory erythema (PIE), the erythematous scars often seen in acne and other inflammatory skin conditions, is not well understood. And despite its pervasive nature, very little data exist that identify its etiology and effective treatment options.

Inflammatory acne scars are not all the same. PIH, often seen with Fitzpatrick skin types III-VI, is related to brown spots, not red spots. Hyperpigmentation is caused by an excess production of melanin. There are treatments for PIH in our armamentarium – such as microdermabrasion, chemical peels, hydroquinone, and vitamin C – that inhibit melanogenesis and blend the skin discoloration.

In contrast, PIE is characterized by pink, red, and sometimes purple-appearing vascular neogenesis seen most often with skin types I-III after an inflammatory skin condition resolves, and is often seen in cystic acne.

The term postinflammatory erythema was initially introduced in the dermatology literature in 2013 by Bae-Harboe et al. to describe erythema often seen after the resolution of inflammatory acne or other inflammatory skin conditions.1 It is not to be confused with the erythema and telangiectasias seen in erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, which is a separate entity.

In my practice, microneedling has also been effective in reducing PIE. Although this may seem counterintuitive because of the bleeding associated with the microneedling process, microneedling-induced skin tissue injury and neocollagenesis have been clinically shown to improve the abnormal vascular proliferation that occurs in PIE. Similar techniques can be used with fractional resurfacing lasers. However, no studies have specifically evaluated the erythematous component of acne scars treated with fractionated lasers.

Topical preparations containing brimonidine (Mirvaso), azelaic acid, and green tea, as well as oral nicotinamide, can have a temporary effect on reducing skin erythema.

However, very little data or clinical studies are available on treatments for PIE, and there are no well-studied preparations with long-term efficacy data. Studies are needed to provide better clinical guidelines for treatment methods and alternatives to treatments, including topical and systemic medications.

References

1. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013 Sep;6(9):46-7.

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 May;60(5):801-7.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

Aesthetic dermatology: What do we know so far about Volbella?

On May 31, 2016, the Food and Drug Administration approved Juvéderm Volbella XC for use in the lips for lip augmentation and for correction of perioral rhytids, in adults over the age of 21. In the U.S. pivotal clinical trial of 168 patients, Juvederm Volbella XC was found to increase lip fullness and soften the appearance of perioral rhytids in two-thirds through 1 year.

Like its previously approved predecessor Juvéderm Voluma XC, approved for the mid-face/cheek area, Juvéderm Volbella XC is composed of hyaluronic acid (HA) using Vycross technology. Vycross technology blends different molecular weights of hyaluronic acid together, allowing for longer duration of the product. Unlike Juvéderm Voluma XC (20 mg/mL), Juvéderm Volbella XC is a lower-concentration HA (15 mg/mL) and has a lower G prime and cohesivity, allowing more horizontal spread as opposed to a lift, which makes it more appropriate for injection into the lips and superficial perioral lines.1

Juvéderm Volbella XC will not be available for use in the United States until October 2016. However, the product was first approved in Europe in 2011, and subsequently in Latin America, the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and Canada. What has been the experience of our neighboring colleagues?

In a randomized, prospective, 12-month controlled European study of 280 patients comparing Volbella to a nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA), Volbella was found to be noninferior to NASHA at 3 months.2 Improvements in lip fullness, perioral lines, and oral commissures for Volbella were statistically significant at 6 and 12 months. Acute swelling was also noted to be less.

In a German 62-patient study with primary endpoints of satisfaction with improvement and look and feel of the lips, a high degree of subject satisfaction with aesthetic improvement in the lips, as well as with their natural look and feel, was noted among 83.6% and 75%-93%, respectively.3

In a retrospective chart review of 400 patients in Israel, where Volbella was injected into tear troughs (disclaimer: not approved for tear troughs in the United States) and/or lips, 17 patients (4.25%) developed prolonged inflammatory cutaneous reactions, lasting up to 11 months, which recurred (with an average number of 3.17 episodes) and occurred late (with an average onset of 8.41 weeks after the injection).4 The reactions were treated with antibiotics and hyaluronidase injections. The finding in this published report is higher than the 0.02% of delayed-onset inflammatory reaction previously reported with HA fillers.

With a full armamentarium of HA and non-HA fillers on the market, we are lucky to have many options to select from to treat aesthetic concerns of patients. For lip and perioral enhancement in the United States, Restylane, Juvéderm, Belotero, and now Volbella are all excellent options. As the dermal filler portfolio available internationally is larger than that in the United States, much can be learned from the experience of our international colleagues.

References

1. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):139S-48S.

2. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Dec;14(12):1444-52.

3. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Jun;13(2):125-34.

4. Dermatol Surg. 2016 Jan;42(1):31-7.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Wesley has no disclosures with regard to Volbella; she participated in clinical trials for Juvéderm Voluma. Dr. Talakoub is a national trainer for Juvéderm manufacturer Allergan for all its injectables.

On May 31, 2016, the Food and Drug Administration approved Juvéderm Volbella XC for use in the lips for lip augmentation and for correction of perioral rhytids, in adults over the age of 21. In the U.S. pivotal clinical trial of 168 patients, Juvederm Volbella XC was found to increase lip fullness and soften the appearance of perioral rhytids in two-thirds through 1 year.

Like its previously approved predecessor Juvéderm Voluma XC, approved for the mid-face/cheek area, Juvéderm Volbella XC is composed of hyaluronic acid (HA) using Vycross technology. Vycross technology blends different molecular weights of hyaluronic acid together, allowing for longer duration of the product. Unlike Juvéderm Voluma XC (20 mg/mL), Juvéderm Volbella XC is a lower-concentration HA (15 mg/mL) and has a lower G prime and cohesivity, allowing more horizontal spread as opposed to a lift, which makes it more appropriate for injection into the lips and superficial perioral lines.1

Juvéderm Volbella XC will not be available for use in the United States until October 2016. However, the product was first approved in Europe in 2011, and subsequently in Latin America, the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and Canada. What has been the experience of our neighboring colleagues?

In a randomized, prospective, 12-month controlled European study of 280 patients comparing Volbella to a nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA), Volbella was found to be noninferior to NASHA at 3 months.2 Improvements in lip fullness, perioral lines, and oral commissures for Volbella were statistically significant at 6 and 12 months. Acute swelling was also noted to be less.

In a German 62-patient study with primary endpoints of satisfaction with improvement and look and feel of the lips, a high degree of subject satisfaction with aesthetic improvement in the lips, as well as with their natural look and feel, was noted among 83.6% and 75%-93%, respectively.3

In a retrospective chart review of 400 patients in Israel, where Volbella was injected into tear troughs (disclaimer: not approved for tear troughs in the United States) and/or lips, 17 patients (4.25%) developed prolonged inflammatory cutaneous reactions, lasting up to 11 months, which recurred (with an average number of 3.17 episodes) and occurred late (with an average onset of 8.41 weeks after the injection).4 The reactions were treated with antibiotics and hyaluronidase injections. The finding in this published report is higher than the 0.02% of delayed-onset inflammatory reaction previously reported with HA fillers.

With a full armamentarium of HA and non-HA fillers on the market, we are lucky to have many options to select from to treat aesthetic concerns of patients. For lip and perioral enhancement in the United States, Restylane, Juvéderm, Belotero, and now Volbella are all excellent options. As the dermal filler portfolio available internationally is larger than that in the United States, much can be learned from the experience of our international colleagues.

References

1. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):139S-48S.

2. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Dec;14(12):1444-52.

3. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Jun;13(2):125-34.

4. Dermatol Surg. 2016 Jan;42(1):31-7.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Wesley has no disclosures with regard to Volbella; she participated in clinical trials for Juvéderm Voluma. Dr. Talakoub is a national trainer for Juvéderm manufacturer Allergan for all its injectables.

On May 31, 2016, the Food and Drug Administration approved Juvéderm Volbella XC for use in the lips for lip augmentation and for correction of perioral rhytids, in adults over the age of 21. In the U.S. pivotal clinical trial of 168 patients, Juvederm Volbella XC was found to increase lip fullness and soften the appearance of perioral rhytids in two-thirds through 1 year.

Like its previously approved predecessor Juvéderm Voluma XC, approved for the mid-face/cheek area, Juvéderm Volbella XC is composed of hyaluronic acid (HA) using Vycross technology. Vycross technology blends different molecular weights of hyaluronic acid together, allowing for longer duration of the product. Unlike Juvéderm Voluma XC (20 mg/mL), Juvéderm Volbella XC is a lower-concentration HA (15 mg/mL) and has a lower G prime and cohesivity, allowing more horizontal spread as opposed to a lift, which makes it more appropriate for injection into the lips and superficial perioral lines.1

Juvéderm Volbella XC will not be available for use in the United States until October 2016. However, the product was first approved in Europe in 2011, and subsequently in Latin America, the Middle East, Asia Pacific, and Canada. What has been the experience of our neighboring colleagues?

In a randomized, prospective, 12-month controlled European study of 280 patients comparing Volbella to a nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA), Volbella was found to be noninferior to NASHA at 3 months.2 Improvements in lip fullness, perioral lines, and oral commissures for Volbella were statistically significant at 6 and 12 months. Acute swelling was also noted to be less.

In a German 62-patient study with primary endpoints of satisfaction with improvement and look and feel of the lips, a high degree of subject satisfaction with aesthetic improvement in the lips, as well as with their natural look and feel, was noted among 83.6% and 75%-93%, respectively.3

In a retrospective chart review of 400 patients in Israel, where Volbella was injected into tear troughs (disclaimer: not approved for tear troughs in the United States) and/or lips, 17 patients (4.25%) developed prolonged inflammatory cutaneous reactions, lasting up to 11 months, which recurred (with an average number of 3.17 episodes) and occurred late (with an average onset of 8.41 weeks after the injection).4 The reactions were treated with antibiotics and hyaluronidase injections. The finding in this published report is higher than the 0.02% of delayed-onset inflammatory reaction previously reported with HA fillers.

With a full armamentarium of HA and non-HA fillers on the market, we are lucky to have many options to select from to treat aesthetic concerns of patients. For lip and perioral enhancement in the United States, Restylane, Juvéderm, Belotero, and now Volbella are all excellent options. As the dermal filler portfolio available internationally is larger than that in the United States, much can be learned from the experience of our international colleagues.

References

1. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):139S-48S.

2. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015 Dec;14(12):1444-52.

3. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Jun;13(2):125-34.

4. Dermatol Surg. 2016 Jan;42(1):31-7.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Wesley has no disclosures with regard to Volbella; she participated in clinical trials for Juvéderm Voluma. Dr. Talakoub is a national trainer for Juvéderm manufacturer Allergan for all its injectables.

Color correcting – for skin blemishes

One of the most frustrating problems we encounter is helping patients with skin issues that we cannot immediately fix or cure. Teaching them the art of concealing skin blemishes gives patients a sense of relief. Color correction is an art and requires an understanding of basic color theory and Fitzpatrick skin type.

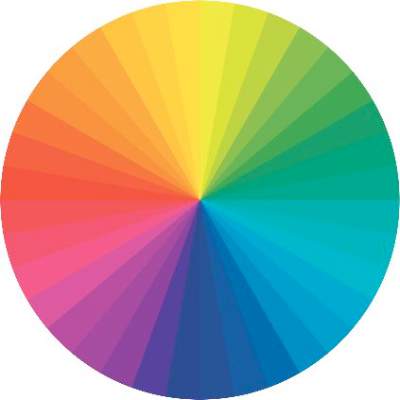

On the color wheel, each color sits directly across from another color, making them complementary colors.

If we look at red, the color opposing it is green. When red and green are combined, they neutralize each other. One of the greatest dermatologists of all time and my mentor, Timothy Berger, MD, taught me that in dermatology color “hue” is a clue to understanding morphology. Everything that is red cannot just be called “erythematous.” There is orange/red (pityriasis rosea, tinea versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis), deep red (cellulitis, Sweet’s syndrome, acne scars, rosacea, psoriasis), purple/red (vasculitis, lichen planus (LP), veins, under-eye circles), brown/red (pigmented purpura, pigmented acne scars, sarcoid).

The combination of the underlying pathology, morphology, and Fitzpatrick type is both a clue to diagnosis and a pallet for skin concealers. We can use the following techniques to help patients color correct skin imperfections:

Red: rosacea, acne scars, acne

Green-based concealers and primers are the best option to significantly reduce the redness. While green primers and correctors tend to be great for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, a yellow-based concealer/corrector can help to cover redness on those with skin types IV-VI.

Blue: periorbital veins

If you are dealing with blue-toned skin lesions, such as periorbital veins, the ideal corrector is one with a peach or orange undertones. For skin types I-III, a peach/salmon corrector works best, whereas skin types IV-VI requires an orange-toned corrector.

Purple: under-eye circles, LP, postprocedure bruising

If under-eye circles tend to have a more purple hue to them, a yellow-based corrector works best for skin types I-III. For skin types IV-VI skin types, you will need a corrector with a red undertone.

Yellow: bruising

Purple/lavender correctors are best suited for eliminating yellow tones from the face. Purple also combats sallow undertones of the skin.

Brown: lentigines, melasma, seborrheic keratosis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, nevi, café au lait spots

Brown is actually the hardest of all colors to correct. The deeper the pigment (ashy dermatitis, melasma) the more gray the areas appear with skin concealers. The more superficial the pigment (ephelides, lentigines), the easier it is to correct. Generally speaking, peach toned concealers work best, not beige or brown. The corrector, however, should be lighter than the skin tone or the lesion itself will appear darker.

Helping patients conceal imperfections with these simple guidelines is a great way to help relieve some anxiety and help our patients fell more confident in their skin.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

One of the most frustrating problems we encounter is helping patients with skin issues that we cannot immediately fix or cure. Teaching them the art of concealing skin blemishes gives patients a sense of relief. Color correction is an art and requires an understanding of basic color theory and Fitzpatrick skin type.

On the color wheel, each color sits directly across from another color, making them complementary colors.

If we look at red, the color opposing it is green. When red and green are combined, they neutralize each other. One of the greatest dermatologists of all time and my mentor, Timothy Berger, MD, taught me that in dermatology color “hue” is a clue to understanding morphology. Everything that is red cannot just be called “erythematous.” There is orange/red (pityriasis rosea, tinea versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis), deep red (cellulitis, Sweet’s syndrome, acne scars, rosacea, psoriasis), purple/red (vasculitis, lichen planus (LP), veins, under-eye circles), brown/red (pigmented purpura, pigmented acne scars, sarcoid).

The combination of the underlying pathology, morphology, and Fitzpatrick type is both a clue to diagnosis and a pallet for skin concealers. We can use the following techniques to help patients color correct skin imperfections:

Red: rosacea, acne scars, acne

Green-based concealers and primers are the best option to significantly reduce the redness. While green primers and correctors tend to be great for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, a yellow-based concealer/corrector can help to cover redness on those with skin types IV-VI.

Blue: periorbital veins

If you are dealing with blue-toned skin lesions, such as periorbital veins, the ideal corrector is one with a peach or orange undertones. For skin types I-III, a peach/salmon corrector works best, whereas skin types IV-VI requires an orange-toned corrector.

Purple: under-eye circles, LP, postprocedure bruising

If under-eye circles tend to have a more purple hue to them, a yellow-based corrector works best for skin types I-III. For skin types IV-VI skin types, you will need a corrector with a red undertone.

Yellow: bruising

Purple/lavender correctors are best suited for eliminating yellow tones from the face. Purple also combats sallow undertones of the skin.

Brown: lentigines, melasma, seborrheic keratosis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, nevi, café au lait spots

Brown is actually the hardest of all colors to correct. The deeper the pigment (ashy dermatitis, melasma) the more gray the areas appear with skin concealers. The more superficial the pigment (ephelides, lentigines), the easier it is to correct. Generally speaking, peach toned concealers work best, not beige or brown. The corrector, however, should be lighter than the skin tone or the lesion itself will appear darker.

Helping patients conceal imperfections with these simple guidelines is a great way to help relieve some anxiety and help our patients fell more confident in their skin.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

One of the most frustrating problems we encounter is helping patients with skin issues that we cannot immediately fix or cure. Teaching them the art of concealing skin blemishes gives patients a sense of relief. Color correction is an art and requires an understanding of basic color theory and Fitzpatrick skin type.

On the color wheel, each color sits directly across from another color, making them complementary colors.

If we look at red, the color opposing it is green. When red and green are combined, they neutralize each other. One of the greatest dermatologists of all time and my mentor, Timothy Berger, MD, taught me that in dermatology color “hue” is a clue to understanding morphology. Everything that is red cannot just be called “erythematous.” There is orange/red (pityriasis rosea, tinea versicolor, seborrheic dermatitis), deep red (cellulitis, Sweet’s syndrome, acne scars, rosacea, psoriasis), purple/red (vasculitis, lichen planus (LP), veins, under-eye circles), brown/red (pigmented purpura, pigmented acne scars, sarcoid).

The combination of the underlying pathology, morphology, and Fitzpatrick type is both a clue to diagnosis and a pallet for skin concealers. We can use the following techniques to help patients color correct skin imperfections:

Red: rosacea, acne scars, acne

Green-based concealers and primers are the best option to significantly reduce the redness. While green primers and correctors tend to be great for Fitzpatrick skin types I-III, a yellow-based concealer/corrector can help to cover redness on those with skin types IV-VI.

Blue: periorbital veins

If you are dealing with blue-toned skin lesions, such as periorbital veins, the ideal corrector is one with a peach or orange undertones. For skin types I-III, a peach/salmon corrector works best, whereas skin types IV-VI requires an orange-toned corrector.

Purple: under-eye circles, LP, postprocedure bruising

If under-eye circles tend to have a more purple hue to them, a yellow-based corrector works best for skin types I-III. For skin types IV-VI skin types, you will need a corrector with a red undertone.

Yellow: bruising

Purple/lavender correctors are best suited for eliminating yellow tones from the face. Purple also combats sallow undertones of the skin.

Brown: lentigines, melasma, seborrheic keratosis, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, nevi, café au lait spots

Brown is actually the hardest of all colors to correct. The deeper the pigment (ashy dermatitis, melasma) the more gray the areas appear with skin concealers. The more superficial the pigment (ephelides, lentigines), the easier it is to correct. Generally speaking, peach toned concealers work best, not beige or brown. The corrector, however, should be lighter than the skin tone or the lesion itself will appear darker.

Helping patients conceal imperfections with these simple guidelines is a great way to help relieve some anxiety and help our patients fell more confident in their skin.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected].

Laser and electrocautery plume

A recent publication by Chuang et al. carefully characterizes the content of smoke (or plume) created from laser hair removal.1 At the University of California, Los Angeles, discarded terminal hairs from the trunk and extremities were collected from two adult volunteers. The hair samples were sealed in glass gas chromatography chambers and treated with either an 810-nm diode laser (Lightsheer, Lumenis) or 755-nm alexandrite laser (Gentlelase, Candela). During laser hair removal (LHR) treatment, two 6-L negative-pressure canisters were used to capture 30 seconds of laser plume, and a portable condensation particle counter was used to measure ultrafine particulates (less than 1 mcm). Ultrafine particle concentrations were measured within the treatment room, within the waiting room, and outside the building. The laser plume was then analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) at the Boston University department of chemistry.

Analysis with GC-MS identified 377 chemical compounds. Sixty-two of the compounds exhibited strong absorption peaks, of which 13 are known or suspected carcinogens (including benzene, ethylbenzene, benzeneacetonitrile, acetonitrile, quinoline, isoquinoline, sterene, diethyl phthalate, 2-methylpyridine, naphthalene carbonitrile, and propene) and more than 20 are known environmental toxins causing acute toxic effects on exposure (including carbon monoxide, p-xylene, phenol, toluene, benzaldehyde, benzenedicarboxylic acid [phthalic acid], and long-chain and cyclic hydrocarbons).

During LHR, the portable condensation particle counters documented an eightfold increase, compared with the ambient room baseline level of ultrafine particle concentrations (ambient room baseline, 15,300 particles per cubic centimeter [ppc]; LHR with smoke evacuator, 129,376 ppc), even when a smoke evacuator was in close proximity (5.0 cm) to the procedure site. When the smoke evacuator was turned off for 30 seconds, there was a more than 26-fold increase in particulate count, compared with ambient baseline levels (ambient baseline, 15,300 ppc; LHR without smoke evacuator for 30 seconds, 435,888 ppc).

It has long been known that smoke created from electrocautery also may impose a risk on the health care worker. In 2011, Lewin et al. published a comprehensive review of the risk that surgical smoke and laser imposes on the dermatologist.2 At this time, most of the laser data was for the plume created by ablative CO2 lasers. In their review, it was stated that surgical smoke is composed of 95% water and 5% particulate matter (made up of chemicals, blood and tissue particles, viruses, and bacteria). The size of the particulate matter is dictated by the device used, with electrosurgical units creating particles of roughly 0.07 mcm and lasers liberating particles of 0.31 mcm. The size of liberated particles is important as those smaller than 100 mcm in diameter remain airborne, and particles less than 2 mcm are deposited in the bronchioles and alveoli.

Electrocautery plume is composed mostly of hydrocarbons, phenols, nitriles, and fatty acids, but most notably carbon monoxide, acrylonitrile, hydrogen cyanide, and benzene, which may have carcinogenic potential. On the mucosa of the canine tongue, the mutagenic effect of the smoke from 1 g of cauterized tissue with laser and electrocautery was equivalent to those from three or six cigarettes, respectively. Pulmonary changes also may occur. Blood vessel hypertrophy, alveolar congestion, and emphysematous changes were seen in rats after plume created from both electrocautery and Nd:Yag ablation of porcine skin. In that study, pulmonary changes were less severe in rats exposed to surgical smoke collected with single- and double-filtered smoke evacuators than unfiltered smoke.

Infection also poses a risk, with bovine papillomavirus and HPV detected in CO2 laser plume as early as 1988. In 1995, Gloster and Roenigk at the Mayo Clinic conducted a comparative study using questionnaires sent to members of the American Society for Laser Surgeons and the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery.3 The comparison groups were CO2 laser surgeons and two large groups of patients in the community with a diagnosis of warts. Analysis revealed that CO2 laser surgeons had a statistically significant greater risk of acquiring nasopharyngeal warts but were less likely to acquire plantar, genital, and perianal warts than the Mayo Clinic patient group did, demonstrating that laser plume is a likely means by which HPV can be transmitted to the upper airway, suggesting that those using lasers to treat HPV lesions are at greater risk. Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Neisseria also have been detected during laser resurfacing.

Traditional surgical masks are able to capture particles greater than 5 mcm but offer no protection against particulate matter produced by electrosurgical and laser devices liberating byproducts less than 1 mcm. Laser masks or high-filtration masks provide greater protection than do standard surgical masks and are able to filter particles to 1.1 mcm; however, it has been shown that approximately 77% of particulate matter in surgical smoke is 1.1 mcm and smaller. Smoke evacuators consist of a suction unit (vacuum pump), filter, hose, and inlet nozzle. The smoke evacuator should have a capture velocity of approximately 30-45 m/min at the inlet nozzle. As the effectiveness of the smoke evacuator decreases with farther distance away from the procedure site, the current study of laser plume from LHR recommends that the smoke evacuator be placed within 5 cm of plume generation.4 In a study of warts treated with CO2 laser or electrocoagulation, smoke evacuators are 98.6% effective when placed 1 cm from the treatment site, with efficacy decreasing to 50% when moved to 2 cm from the treatment site.

As our specialty likely conducts the highest proportion of laser and electrosurgical procedures of any specialty, current recommendations for electrocautery, laser resurfacing, and LHR should include adequate air filtration and the use of high-filtration masks and smoke evacuators by the health care practitioner.

References

1. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jul 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2097. [Epub ahead of print]

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Sep;65(3):636-41.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Mar;32(3):436-41.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989 Jul;21(1):41-9.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected].

A recent publication by Chuang et al. carefully characterizes the content of smoke (or plume) created from laser hair removal.1 At the University of California, Los Angeles, discarded terminal hairs from the trunk and extremities were collected from two adult volunteers. The hair samples were sealed in glass gas chromatography chambers and treated with either an 810-nm diode laser (Lightsheer, Lumenis) or 755-nm alexandrite laser (Gentlelase, Candela). During laser hair removal (LHR) treatment, two 6-L negative-pressure canisters were used to capture 30 seconds of laser plume, and a portable condensation particle counter was used to measure ultrafine particulates (less than 1 mcm). Ultrafine particle concentrations were measured within the treatment room, within the waiting room, and outside the building. The laser plume was then analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) at the Boston University department of chemistry.

Analysis with GC-MS identified 377 chemical compounds. Sixty-two of the compounds exhibited strong absorption peaks, of which 13 are known or suspected carcinogens (including benzene, ethylbenzene, benzeneacetonitrile, acetonitrile, quinoline, isoquinoline, sterene, diethyl phthalate, 2-methylpyridine, naphthalene carbonitrile, and propene) and more than 20 are known environmental toxins causing acute toxic effects on exposure (including carbon monoxide, p-xylene, phenol, toluene, benzaldehyde, benzenedicarboxylic acid [phthalic acid], and long-chain and cyclic hydrocarbons).

During LHR, the portable condensation particle counters documented an eightfold increase, compared with the ambient room baseline level of ultrafine particle concentrations (ambient room baseline, 15,300 particles per cubic centimeter [ppc]; LHR with smoke evacuator, 129,376 ppc), even when a smoke evacuator was in close proximity (5.0 cm) to the procedure site. When the smoke evacuator was turned off for 30 seconds, there was a more than 26-fold increase in particulate count, compared with ambient baseline levels (ambient baseline, 15,300 ppc; LHR without smoke evacuator for 30 seconds, 435,888 ppc).

It has long been known that smoke created from electrocautery also may impose a risk on the health care worker. In 2011, Lewin et al. published a comprehensive review of the risk that surgical smoke and laser imposes on the dermatologist.2 At this time, most of the laser data was for the plume created by ablative CO2 lasers. In their review, it was stated that surgical smoke is composed of 95% water and 5% particulate matter (made up of chemicals, blood and tissue particles, viruses, and bacteria). The size of the particulate matter is dictated by the device used, with electrosurgical units creating particles of roughly 0.07 mcm and lasers liberating particles of 0.31 mcm. The size of liberated particles is important as those smaller than 100 mcm in diameter remain airborne, and particles less than 2 mcm are deposited in the bronchioles and alveoli.

Electrocautery plume is composed mostly of hydrocarbons, phenols, nitriles, and fatty acids, but most notably carbon monoxide, acrylonitrile, hydrogen cyanide, and benzene, which may have carcinogenic potential. On the mucosa of the canine tongue, the mutagenic effect of the smoke from 1 g of cauterized tissue with laser and electrocautery was equivalent to those from three or six cigarettes, respectively. Pulmonary changes also may occur. Blood vessel hypertrophy, alveolar congestion, and emphysematous changes were seen in rats after plume created from both electrocautery and Nd:Yag ablation of porcine skin. In that study, pulmonary changes were less severe in rats exposed to surgical smoke collected with single- and double-filtered smoke evacuators than unfiltered smoke.

Infection also poses a risk, with bovine papillomavirus and HPV detected in CO2 laser plume as early as 1988. In 1995, Gloster and Roenigk at the Mayo Clinic conducted a comparative study using questionnaires sent to members of the American Society for Laser Surgeons and the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery.3 The comparison groups were CO2 laser surgeons and two large groups of patients in the community with a diagnosis of warts. Analysis revealed that CO2 laser surgeons had a statistically significant greater risk of acquiring nasopharyngeal warts but were less likely to acquire plantar, genital, and perianal warts than the Mayo Clinic patient group did, demonstrating that laser plume is a likely means by which HPV can be transmitted to the upper airway, suggesting that those using lasers to treat HPV lesions are at greater risk. Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Neisseria also have been detected during laser resurfacing.

Traditional surgical masks are able to capture particles greater than 5 mcm but offer no protection against particulate matter produced by electrosurgical and laser devices liberating byproducts less than 1 mcm. Laser masks or high-filtration masks provide greater protection than do standard surgical masks and are able to filter particles to 1.1 mcm; however, it has been shown that approximately 77% of particulate matter in surgical smoke is 1.1 mcm and smaller. Smoke evacuators consist of a suction unit (vacuum pump), filter, hose, and inlet nozzle. The smoke evacuator should have a capture velocity of approximately 30-45 m/min at the inlet nozzle. As the effectiveness of the smoke evacuator decreases with farther distance away from the procedure site, the current study of laser plume from LHR recommends that the smoke evacuator be placed within 5 cm of plume generation.4 In a study of warts treated with CO2 laser or electrocoagulation, smoke evacuators are 98.6% effective when placed 1 cm from the treatment site, with efficacy decreasing to 50% when moved to 2 cm from the treatment site.

As our specialty likely conducts the highest proportion of laser and electrosurgical procedures of any specialty, current recommendations for electrocautery, laser resurfacing, and LHR should include adequate air filtration and the use of high-filtration masks and smoke evacuators by the health care practitioner.

References

1. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jul 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2097. [Epub ahead of print]

2. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Sep;65(3):636-41.

3. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Mar;32(3):436-41.

4. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989 Jul;21(1):41-9.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Talakoub are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at [email protected].

A recent publication by Chuang et al. carefully characterizes the content of smoke (or plume) created from laser hair removal.1 At the University of California, Los Angeles, discarded terminal hairs from the trunk and extremities were collected from two adult volunteers. The hair samples were sealed in glass gas chromatography chambers and treated with either an 810-nm diode laser (Lightsheer, Lumenis) or 755-nm alexandrite laser (Gentlelase, Candela). During laser hair removal (LHR) treatment, two 6-L negative-pressure canisters were used to capture 30 seconds of laser plume, and a portable condensation particle counter was used to measure ultrafine particulates (less than 1 mcm). Ultrafine particle concentrations were measured within the treatment room, within the waiting room, and outside the building. The laser plume was then analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) at the Boston University department of chemistry.

Analysis with GC-MS identified 377 chemical compounds. Sixty-two of the compounds exhibited strong absorption peaks, of which 13 are known or suspected carcinogens (including benzene, ethylbenzene, benzeneacetonitrile, acetonitrile, quinoline, isoquinoline, sterene, diethyl phthalate, 2-methylpyridine, naphthalene carbonitrile, and propene) and more than 20 are known environmental toxins causing acute toxic effects on exposure (including carbon monoxide, p-xylene, phenol, toluene, benzaldehyde, benzenedicarboxylic acid [phthalic acid], and long-chain and cyclic hydrocarbons).

During LHR, the portable condensation particle counters documented an eightfold increase, compared with the ambient room baseline level of ultrafine particle concentrations (ambient room baseline, 15,300 particles per cubic centimeter [ppc]; LHR with smoke evacuator, 129,376 ppc), even when a smoke evacuator was in close proximity (5.0 cm) to the procedure site. When the smoke evacuator was turned off for 30 seconds, there was a more than 26-fold increase in particulate count, compared with ambient baseline levels (ambient baseline, 15,300 ppc; LHR without smoke evacuator for 30 seconds, 435,888 ppc).

It has long been known that smoke created from electrocautery also may impose a risk on the health care worker. In 2011, Lewin et al. published a comprehensive review of the risk that surgical smoke and laser imposes on the dermatologist.2 At this time, most of the laser data was for the plume created by ablative CO2 lasers. In their review, it was stated that surgical smoke is composed of 95% water and 5% particulate matter (made up of chemicals, blood and tissue particles, viruses, and bacteria). The size of the particulate matter is dictated by the device used, with electrosurgical units creating particles of roughly 0.07 mcm and lasers liberating particles of 0.31 mcm. The size of liberated particles is important as those smaller than 100 mcm in diameter remain airborne, and particles less than 2 mcm are deposited in the bronchioles and alveoli.

Electrocautery plume is composed mostly of hydrocarbons, phenols, nitriles, and fatty acids, but most notably carbon monoxide, acrylonitrile, hydrogen cyanide, and benzene, which may have carcinogenic potential. On the mucosa of the canine tongue, the mutagenic effect of the smoke from 1 g of cauterized tissue with laser and electrocautery was equivalent to those from three or six cigarettes, respectively. Pulmonary changes also may occur. Blood vessel hypertrophy, alveolar congestion, and emphysematous changes were seen in rats after plume created from both electrocautery and Nd:Yag ablation of porcine skin. In that study, pulmonary changes were less severe in rats exposed to surgical smoke collected with single- and double-filtered smoke evacuators than unfiltered smoke.