User login

Building a New Framework for Equity: Pediatric Hospital Medicine Must Lead the Way

Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) only recently became a recognized pediatric subspecialty with the first certification exam taking place in 2019. As a new field composed largely of women, it has a unique opportunity to set the example of how to operationalize gender equity in leadership by tracking metrics, creating intentional processes for hiring and promotion, and implementing policies in a transparent way.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Allan et al1 report that women, who comprise 70% of the field, appear proportionally represented in associate/assistant but not senior leadership roles when compared to the PHM field at large. Eighty-one percent of associate division directors but only 55% of division directors were women, and 82% of assistant fellowship directors but only 66% of fellowship directors were women. These downward trends in the proportion of women in leadership roles as the roles become more senior is not an unfamiliar pattern. This echoes academic pediatric positions more broadly: women’s representation slides from 63% of active physicians to approximately 57% active faculty and then to 26% as department chairs.2 The same story holds true for deans’ offices in US medical schools, where 34% of associate deans are women and yet only 18% of deans are women. The number of women deans has only increased by about one each year, on average, since 2009.3 C-suite leadership roles in healthcare mimic this same downward trajectory.4 Burden et al found that while there was equal gender representation of hospitalists and general internists who worked in university hospitals, women led only a minority of (adult) hospital medicine (16%) or general internal medicine (35%) sections or divisions at university hospitals.5 Women with intersectionality, such as Black women and other women of color, are even more grossly underrepresented in leadership roles.

How can we change this pattern to ensure that leadership in PHM, and in medicine in general, represents diverse voices and reflects the community it serves? Allan et al have established an important baseline for tracking gender equity in PHM. Institutions, organizations, and societies must now prioritize, value and promote a culture of diversity, inclusivity, sponsorship, and allyship. For example, institutions can create and enforce policies in which compensation and promotion are tied to a leader’s achievement of transparent gender equity and diversity targets to ensure accountability. Institutions should commit dedicated and substantive funding to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and provide a regular diversity report that tracks gender distribution, hiring and attrition, and representation in leadership. Institutions should implement “best search practices” for all leadership positions. Additionally, all faculty should receive regular and ongoing professional development planning to enhance academic productivity and professional satisfaction and improve retention.

Women in medicine disproportionately experience many issues, including harassment, bias, and childcare and household responsibilities, that adversely affect their career trajectory. PHM is in a unique position to trailblaze a new framework for ensuring gender equity in its field. Let’s not lose this opportunity to set a new course that other specialties can follow.

1. Allan JM, Kim JL, Ralston SL, et al. Gender distribution in pediatric hospital medicine leadership. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:31-33. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3555

2. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144 (5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

3. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020.

4. Berlin G, Darino L, Groh R, Kumar P. Women in Healthcare: Moving From the Front Lines to the Top Rung. McKinsey & Company; August 15, 2020.

5. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities for academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) only recently became a recognized pediatric subspecialty with the first certification exam taking place in 2019. As a new field composed largely of women, it has a unique opportunity to set the example of how to operationalize gender equity in leadership by tracking metrics, creating intentional processes for hiring and promotion, and implementing policies in a transparent way.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Allan et al1 report that women, who comprise 70% of the field, appear proportionally represented in associate/assistant but not senior leadership roles when compared to the PHM field at large. Eighty-one percent of associate division directors but only 55% of division directors were women, and 82% of assistant fellowship directors but only 66% of fellowship directors were women. These downward trends in the proportion of women in leadership roles as the roles become more senior is not an unfamiliar pattern. This echoes academic pediatric positions more broadly: women’s representation slides from 63% of active physicians to approximately 57% active faculty and then to 26% as department chairs.2 The same story holds true for deans’ offices in US medical schools, where 34% of associate deans are women and yet only 18% of deans are women. The number of women deans has only increased by about one each year, on average, since 2009.3 C-suite leadership roles in healthcare mimic this same downward trajectory.4 Burden et al found that while there was equal gender representation of hospitalists and general internists who worked in university hospitals, women led only a minority of (adult) hospital medicine (16%) or general internal medicine (35%) sections or divisions at university hospitals.5 Women with intersectionality, such as Black women and other women of color, are even more grossly underrepresented in leadership roles.

How can we change this pattern to ensure that leadership in PHM, and in medicine in general, represents diverse voices and reflects the community it serves? Allan et al have established an important baseline for tracking gender equity in PHM. Institutions, organizations, and societies must now prioritize, value and promote a culture of diversity, inclusivity, sponsorship, and allyship. For example, institutions can create and enforce policies in which compensation and promotion are tied to a leader’s achievement of transparent gender equity and diversity targets to ensure accountability. Institutions should commit dedicated and substantive funding to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and provide a regular diversity report that tracks gender distribution, hiring and attrition, and representation in leadership. Institutions should implement “best search practices” for all leadership positions. Additionally, all faculty should receive regular and ongoing professional development planning to enhance academic productivity and professional satisfaction and improve retention.

Women in medicine disproportionately experience many issues, including harassment, bias, and childcare and household responsibilities, that adversely affect their career trajectory. PHM is in a unique position to trailblaze a new framework for ensuring gender equity in its field. Let’s not lose this opportunity to set a new course that other specialties can follow.

Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) only recently became a recognized pediatric subspecialty with the first certification exam taking place in 2019. As a new field composed largely of women, it has a unique opportunity to set the example of how to operationalize gender equity in leadership by tracking metrics, creating intentional processes for hiring and promotion, and implementing policies in a transparent way.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Allan et al1 report that women, who comprise 70% of the field, appear proportionally represented in associate/assistant but not senior leadership roles when compared to the PHM field at large. Eighty-one percent of associate division directors but only 55% of division directors were women, and 82% of assistant fellowship directors but only 66% of fellowship directors were women. These downward trends in the proportion of women in leadership roles as the roles become more senior is not an unfamiliar pattern. This echoes academic pediatric positions more broadly: women’s representation slides from 63% of active physicians to approximately 57% active faculty and then to 26% as department chairs.2 The same story holds true for deans’ offices in US medical schools, where 34% of associate deans are women and yet only 18% of deans are women. The number of women deans has only increased by about one each year, on average, since 2009.3 C-suite leadership roles in healthcare mimic this same downward trajectory.4 Burden et al found that while there was equal gender representation of hospitalists and general internists who worked in university hospitals, women led only a minority of (adult) hospital medicine (16%) or general internal medicine (35%) sections or divisions at university hospitals.5 Women with intersectionality, such as Black women and other women of color, are even more grossly underrepresented in leadership roles.

How can we change this pattern to ensure that leadership in PHM, and in medicine in general, represents diverse voices and reflects the community it serves? Allan et al have established an important baseline for tracking gender equity in PHM. Institutions, organizations, and societies must now prioritize, value and promote a culture of diversity, inclusivity, sponsorship, and allyship. For example, institutions can create and enforce policies in which compensation and promotion are tied to a leader’s achievement of transparent gender equity and diversity targets to ensure accountability. Institutions should commit dedicated and substantive funding to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and provide a regular diversity report that tracks gender distribution, hiring and attrition, and representation in leadership. Institutions should implement “best search practices” for all leadership positions. Additionally, all faculty should receive regular and ongoing professional development planning to enhance academic productivity and professional satisfaction and improve retention.

Women in medicine disproportionately experience many issues, including harassment, bias, and childcare and household responsibilities, that adversely affect their career trajectory. PHM is in a unique position to trailblaze a new framework for ensuring gender equity in its field. Let’s not lose this opportunity to set a new course that other specialties can follow.

1. Allan JM, Kim JL, Ralston SL, et al. Gender distribution in pediatric hospital medicine leadership. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:31-33. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3555

2. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144 (5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

3. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020.

4. Berlin G, Darino L, Groh R, Kumar P. Women in Healthcare: Moving From the Front Lines to the Top Rung. McKinsey & Company; August 15, 2020.

5. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities for academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

1. Allan JM, Kim JL, Ralston SL, et al. Gender distribution in pediatric hospital medicine leadership. J Hosp Med. 2021;16:31-33. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3555

2. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144 (5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

3. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. The State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2020.

4. Berlin G, Darino L, Groh R, Kumar P. Women in Healthcare: Moving From the Front Lines to the Top Rung. McKinsey & Company; August 15, 2020.

5. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities for academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: [email protected]; Telephone: 215-991-8240; Twitter: @ELAMProgram; @NancyDSpector.

Promoting Gender Equity at the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

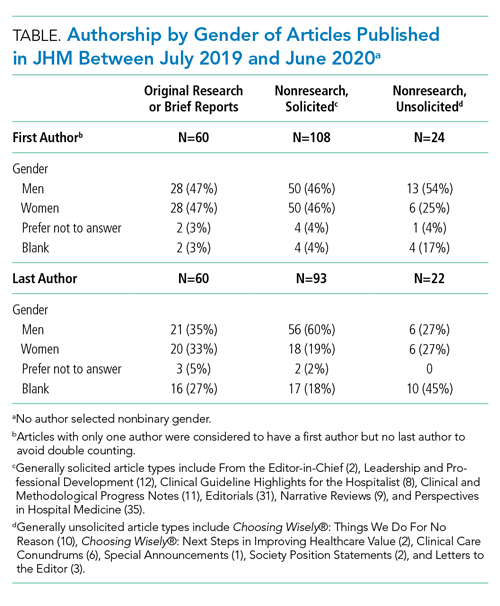

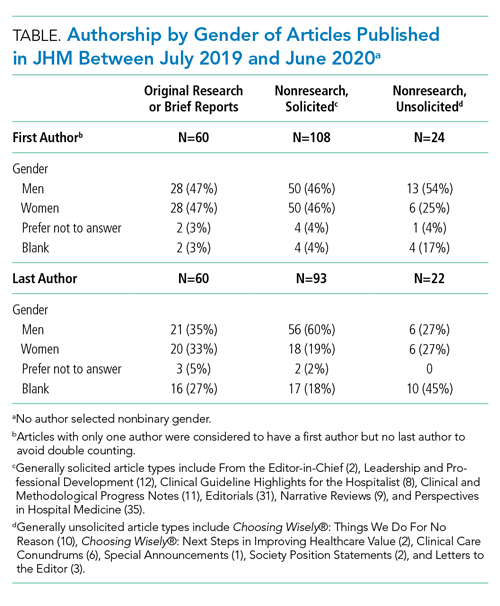

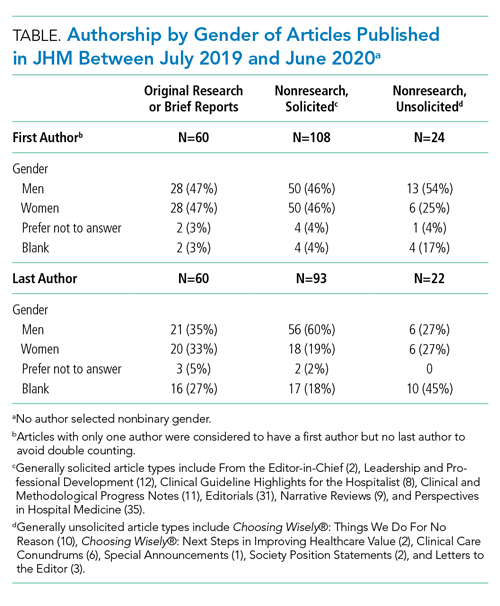

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

Last year we pledged to lead by example and improve representation within the Journal of Hospital Medicine community.1 By emphasizing diversity, we expand the pool of faculty to whom leadership opportunities are available. A diverse team will put forth a broader range of ideas for consideration, spur greater innovation, and promote diversity in both published content and authorship, ensuring that the spectrum of content we publish reflects and benefits all patients to whom we provide care.

We write to share our progress, first reporting on gender equity. Currently, 45% of the journal leadership team are women, increased from 30% in 2018. In the past year, we also developed processes to collect peer reviewer and author demographic information through our manuscript management system. These processes helped us understand our baseline state.

Prior to developing these processes, we discussed our goals and potential approaches with Society of Hospital Medicine leaders; medical school deans of diversity, equity, and inclusion; department chairs in pediatrics and internal medicine; women, underrepresented minorities, and LGBTQ+ faculty; and trainees. We achieved consensus as a journal leadership team and implemented a new data collection system in July 2019. We focused on first and last authors given the importance of these positions for promotion and tenure. We requested that peer reviewers and authors provide demographic data, including gender (with nonbinary as an option), race, and ethnicity; “prefer not to answer” was a response option for each question. These data were not available during the manuscript decision process. Authors who did not submit information received up to three reminder emails from the Editor-in-Chief encouraging them to provide demographic information and stating the rationale for the request. We did not use gender identifying algorithms (eg, assignment of gender probability based on name) or visit professional websites; our intent was author self-identification.

We categorized Journal of Hospital Medicine article types as research, generally solicited, and generally unsolicited (Table). Among research articles, the proportion of women and men were similar with women accounting for 47% of first authors (vs 47% men) and 33% of last authors (vs 35% men) (Table). However, 27% of last authors left this field blank. Among solicited article types, there was an equal proportion of women and men for first but not for last authors. Among unsolicited article types, a smaller proportion of women accounted for first authors. While the proportion of women and men was equal among last authors, 45% left this field blank.

Collecting author demographics and reporting our data on gender represent an important first step for the journal. In the upcoming year, we will develop strategies to obtain more complete data and report our performance on race, ethnicity, and intersectionality, and continue deliberate efforts to improve equity within all areas of the journal, including reviewer, author, and editorial roles. We are committed to continue sharing our progress.

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

1. Shah SS, Shaughnessy EE, Spector ND. Leading by example: how medical journals can improve representation in academic medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019;14:393. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3247

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Leadership & Professional Development: Dis-Missed: Cultural and Gender Barriers to Graceful Self-Promotion

“The world accommodates you for fitting in, but only rewards you for standing out.”

—Matshona Dhliwayo

Graceful self-promotion—a way of speaking diplomatically and strategically about yourself and your accomplishments—is a key behavior to achieve professional success in medicine. However, some of us are uncomfortable with promoting ourselves in the workplace because of concerns about receiving negative backlash for bragging. These concerns may have roots in our cultural and gender backgrounds, norms that strongly influence our social behaviors. Cultures that emphasize collectivism (eg, East Asia, Scandinavia, Latin America), which is associated with modesty and a focus on “we,” may not approve of self-promotion in contrast to cultures that emphasize individualism (eg, United States, Canada, and parts of Western Europe).1 Additionally, societal gender roles across different cultures focus on women conforming to a “modesty norm,” by which they are socialized to “be nice” and “not too demanding.” Female physicians practicing self-promotion for career advancement may experience a backlash with social penalties and career repercussions.2

One’s avoiding self-promotion may lead others to prematurely dismiss a physician’s capability, competence, ambition, and qualifications for leadership and other opportunities. These oversights may be a contributing factor in the existing inequities in physician compensation, faculty promotions, leadership roles, speaking engagements, journal editorial boards, and more. Women make up over 50% of all US medical students, yet only 18% are hospital CEOs, 16% are deans and department chairs, and 7% are editors-in-chief of high-impact medical journals.3

So how do you get started overcoming cultural and gender barriers and embrace graceful self-promotion? Start small!

First, write a reference or nominating letter for a colleague. The exercise of synthesizing someone else’s accomplishments, skills, and experiences for a specific audience and purpose will give you a template to apply to yourself.

Second, identify an accomplishment with an outcome that educates others about you, your ideas, and your impact. Practice with a trusted peer to frame your accomplishment and its context as a story; for example: “Dr. X, I am pleased to share that I will present a key workshop on Y at the upcoming national Z meeting, based largely on the outcomes from a QI initiative that I developed and oversaw with support from my hospitalist team. We overcame initial staff resistance by recruiting project champions among the interdisciplinary team and successfully reduced readmissions for Y from A% to B% over a 12-month period.”

Third, consider when and how to strategically promote the accomplishment with your medical director, clinical leadership, department leadership, etc. Start out gracefully self-promoting in person or via email with a leader with whom you already have a relationship. If you want to share your accomplishment with a leader who does not yet know you (but may be important to your career), nudge a mentor or sponsor for an introductory conversation.

Finally, ask yourself the next time you are doing a performance review or attending a hospital committee meeting: Am I contributing to a culture in which everyone is encouraged to share their accomplishments? Which qualified candidates who don’t speak out about themselves can I nominate, sponsor, mentor, or encourage for an upcoming opportunity to increase cultural and gender representation? After all, paying it forward helps foster the success of others.

Graceful self-promotion is an important tool for personal and professional development in healthcare. Cultural and gender-based barriers to self-promotion can be surmounted through self-awareness, practice with trusted peers, and recognition of the importance of storytelling gracefully. A medical workplace culture that encourages sharing achievements and celebrates individual and team accomplishments can go a long way toward helping people change their perception of self-promotion and overcome their hesitations.

1. Lalwani AK, Shavitt S. The “me” I claim to be: cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):88-102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014100

2. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, Nora LM, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. 2019. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201905a

3. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership. Harvard Business Review. 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership

“The world accommodates you for fitting in, but only rewards you for standing out.”

—Matshona Dhliwayo

Graceful self-promotion—a way of speaking diplomatically and strategically about yourself and your accomplishments—is a key behavior to achieve professional success in medicine. However, some of us are uncomfortable with promoting ourselves in the workplace because of concerns about receiving negative backlash for bragging. These concerns may have roots in our cultural and gender backgrounds, norms that strongly influence our social behaviors. Cultures that emphasize collectivism (eg, East Asia, Scandinavia, Latin America), which is associated with modesty and a focus on “we,” may not approve of self-promotion in contrast to cultures that emphasize individualism (eg, United States, Canada, and parts of Western Europe).1 Additionally, societal gender roles across different cultures focus on women conforming to a “modesty norm,” by which they are socialized to “be nice” and “not too demanding.” Female physicians practicing self-promotion for career advancement may experience a backlash with social penalties and career repercussions.2

One’s avoiding self-promotion may lead others to prematurely dismiss a physician’s capability, competence, ambition, and qualifications for leadership and other opportunities. These oversights may be a contributing factor in the existing inequities in physician compensation, faculty promotions, leadership roles, speaking engagements, journal editorial boards, and more. Women make up over 50% of all US medical students, yet only 18% are hospital CEOs, 16% are deans and department chairs, and 7% are editors-in-chief of high-impact medical journals.3

So how do you get started overcoming cultural and gender barriers and embrace graceful self-promotion? Start small!

First, write a reference or nominating letter for a colleague. The exercise of synthesizing someone else’s accomplishments, skills, and experiences for a specific audience and purpose will give you a template to apply to yourself.

Second, identify an accomplishment with an outcome that educates others about you, your ideas, and your impact. Practice with a trusted peer to frame your accomplishment and its context as a story; for example: “Dr. X, I am pleased to share that I will present a key workshop on Y at the upcoming national Z meeting, based largely on the outcomes from a QI initiative that I developed and oversaw with support from my hospitalist team. We overcame initial staff resistance by recruiting project champions among the interdisciplinary team and successfully reduced readmissions for Y from A% to B% over a 12-month period.”

Third, consider when and how to strategically promote the accomplishment with your medical director, clinical leadership, department leadership, etc. Start out gracefully self-promoting in person or via email with a leader with whom you already have a relationship. If you want to share your accomplishment with a leader who does not yet know you (but may be important to your career), nudge a mentor or sponsor for an introductory conversation.

Finally, ask yourself the next time you are doing a performance review or attending a hospital committee meeting: Am I contributing to a culture in which everyone is encouraged to share their accomplishments? Which qualified candidates who don’t speak out about themselves can I nominate, sponsor, mentor, or encourage for an upcoming opportunity to increase cultural and gender representation? After all, paying it forward helps foster the success of others.

Graceful self-promotion is an important tool for personal and professional development in healthcare. Cultural and gender-based barriers to self-promotion can be surmounted through self-awareness, practice with trusted peers, and recognition of the importance of storytelling gracefully. A medical workplace culture that encourages sharing achievements and celebrates individual and team accomplishments can go a long way toward helping people change their perception of self-promotion and overcome their hesitations.

“The world accommodates you for fitting in, but only rewards you for standing out.”

—Matshona Dhliwayo

Graceful self-promotion—a way of speaking diplomatically and strategically about yourself and your accomplishments—is a key behavior to achieve professional success in medicine. However, some of us are uncomfortable with promoting ourselves in the workplace because of concerns about receiving negative backlash for bragging. These concerns may have roots in our cultural and gender backgrounds, norms that strongly influence our social behaviors. Cultures that emphasize collectivism (eg, East Asia, Scandinavia, Latin America), which is associated with modesty and a focus on “we,” may not approve of self-promotion in contrast to cultures that emphasize individualism (eg, United States, Canada, and parts of Western Europe).1 Additionally, societal gender roles across different cultures focus on women conforming to a “modesty norm,” by which they are socialized to “be nice” and “not too demanding.” Female physicians practicing self-promotion for career advancement may experience a backlash with social penalties and career repercussions.2

One’s avoiding self-promotion may lead others to prematurely dismiss a physician’s capability, competence, ambition, and qualifications for leadership and other opportunities. These oversights may be a contributing factor in the existing inequities in physician compensation, faculty promotions, leadership roles, speaking engagements, journal editorial boards, and more. Women make up over 50% of all US medical students, yet only 18% are hospital CEOs, 16% are deans and department chairs, and 7% are editors-in-chief of high-impact medical journals.3

So how do you get started overcoming cultural and gender barriers and embrace graceful self-promotion? Start small!

First, write a reference or nominating letter for a colleague. The exercise of synthesizing someone else’s accomplishments, skills, and experiences for a specific audience and purpose will give you a template to apply to yourself.

Second, identify an accomplishment with an outcome that educates others about you, your ideas, and your impact. Practice with a trusted peer to frame your accomplishment and its context as a story; for example: “Dr. X, I am pleased to share that I will present a key workshop on Y at the upcoming national Z meeting, based largely on the outcomes from a QI initiative that I developed and oversaw with support from my hospitalist team. We overcame initial staff resistance by recruiting project champions among the interdisciplinary team and successfully reduced readmissions for Y from A% to B% over a 12-month period.”

Third, consider when and how to strategically promote the accomplishment with your medical director, clinical leadership, department leadership, etc. Start out gracefully self-promoting in person or via email with a leader with whom you already have a relationship. If you want to share your accomplishment with a leader who does not yet know you (but may be important to your career), nudge a mentor or sponsor for an introductory conversation.

Finally, ask yourself the next time you are doing a performance review or attending a hospital committee meeting: Am I contributing to a culture in which everyone is encouraged to share their accomplishments? Which qualified candidates who don’t speak out about themselves can I nominate, sponsor, mentor, or encourage for an upcoming opportunity to increase cultural and gender representation? After all, paying it forward helps foster the success of others.

Graceful self-promotion is an important tool for personal and professional development in healthcare. Cultural and gender-based barriers to self-promotion can be surmounted through self-awareness, practice with trusted peers, and recognition of the importance of storytelling gracefully. A medical workplace culture that encourages sharing achievements and celebrates individual and team accomplishments can go a long way toward helping people change their perception of self-promotion and overcome their hesitations.

1. Lalwani AK, Shavitt S. The “me” I claim to be: cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):88-102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014100

2. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, Nora LM, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. 2019. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201905a

3. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership. Harvard Business Review. 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership

1. Lalwani AK, Shavitt S. The “me” I claim to be: cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):88-102. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014100

2. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, Nora LM, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. 2019. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201905a

3. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership. Harvard Business Review. 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected every facet of our work and personal lives. While many hope we will return to “normal” with the pandemic’s passing, there is reason to believe medicine, and society, will experience irrevocable changes. Although the number of women pursuing and practicing medicine has increased, inequities remain in compensation, academic rank, and leadership positions.1,2 Within the workplace, women are more likely to be in frontline clinical positions, are more likely to be integral in promoting positive interpersonal relationships and collaborative work environments, and often are less represented in the high-level, decision-making roles in leadership or administration.3,4 These well-described issues may be exacerbated during this pandemic crisis. We describe how the current COVID-19 pandemic may intensify workplace inequities for women, and propose solutions for hospitalist groups, leaders, and administrators to ensure female hospitalists continue to prosper and thrive in these tenuous times.

HOW THE PANDEMIC MAY EXACERBATE EXISTING INEQUITIES

Increasing Demands at Home

Female physicians are more likely to have partners who are employed full-time and report spending more time on household activities including cleaning, cooking, and the care of children, compared with their male counterparts.5 With school and daycare closings, as well as stay-at-home orders in many US states, there has been an increase in household responsibilities and care needs for children remaining at home with a marked decrease in options for stable or emergency childcare.6 As compared with primary care and subspecialty colleagues who can provide a large percentage of their care through telemedicine, this is not the case for hospitalists who must be physically present to care for their patients. Therefore, hospitalists are unable to clinically “work from home” in the same way as many of their colleagues in other specialties. Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up.7 In addition, women who are involved with administrative, leadership, or research activities may struggle to execute their responsibilities as a result of increased domestic duties.

Many hospitalists are also concerned about contracting COVID-19 and exposing their families to the illness given the high infection rate among healthcare workers and the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).8,9 Institutions and national organizations, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have partnered with industry to provide discounted or complimentary hotel rooms for members to aid self-isolation while providing clinical care.10 One famous photo in popular and social media showed a pulmonary and critical care physician in a tent in his garage in order to self-isolate from his family.11 However, since women are often the primary caregivers for their children or other family members and may also be responsible for other important household activities, they may be unable or unwilling to remove themselves from their children and families. As a result, female hospitalists may encounter feelings of guilt or inadequacy if they’re unable to isolate in the same manner as male colleagues.8

Exaggerating Leadership Gap

One of the keys to a robust response to this pandemic is strong, thoughtful, and strategic leadership.12 Institutional, regional, and national leaders are at the forefront of designing the solutions to the many problems the COVID-19 pandemic has created. The paucity of women at high-level leadership positions in institutions across the United States, including university-based, community, public, and private institutions, means that there is a lack of female representation when institutional policy is being discussed and decided.4 This lack of representation may lead to policies and procedures that negatively affect female hospitalists or, at best, fail to consider the needs of or support female physicians. For example, leaders of a hospital medicine group may create mandatory “backup” coverage for night and weekend shifts for their group during surge periods of the pandemic without considering implications for childcare. Finding weekday, daytime coverage is challenging for many during this time when daycares and school are closed, and finding coverage during weekend or overnight hours will be even more challenging. With increased risks for older adults with high-risk medical conditions, grandparents or other friends or family members that previously would have assisted with childcare may no longer be an option. If a female hospitalist is not a member of the leadership group that helped design this coverage structure, there could be a lack of recognition of the undue strain this coverage model could create for women in the group. Even if not intentional, such policies may hinder women’s career stability and opportunities for further advancement, as well as their ability to adequately provide care for their families. Having women as a part of the leadership group that creates policies and schedules and makes pivotal decisions is imperative, especially regarding topics of providing access and compensation for “emergency childcare,” hazard pay, shift length, work conditions, job security, sick leave, workers compensation, advancement opportunities, and hiring practices.

Compensation

The gender pay gap in medicine has been consistently demonstrated among many specialties.13,14 The reasons for this inequity are multifactorial, and the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to further widen this gap. With the unequal burden of unpaid care provided by women and their higher prevalence as frontline workers, they are at greater risk of needing to take unpaid leave to care for a sick family member or themselves.6,7 Similarly, without hazard pay, those with direct clinical responsibilities bear the risk of illness for themselves and their families without adequate compensation.

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

The overall well-being of the hospitalist workforce is critical to continue to provide the highest level of care for our patients. With higher workloads at home and at work, female hospitalists are at risk for increased burnout. Burnout has been linked to many negative outcomes including poor performance, depression, suicide, and leaving the profession.15 Burnout is documented to be higher in female physicians with several contributing factors that are aggravated by gender inequities, including having children at home, gender bias, and real or perceived lack of fairness in promotion and compensation.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the stress of having children in the home, as well as concerns around fair compensation as described above. The consequences of this have yet to be fully realized but may be dire.

PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS

We propose the following recommendations to help mitigate the effects of this epidemic and to continue to move our field forward on our path to equity.

1. Closely monitor the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists. While there has been a recent increase in scholarship on the pre–COVID-19 state of gender disparities, there is still much that is unknown. As we experience this upheaval in the way our institutions function, it is even more imperative to track gender deaggregated key indicators of wellness, burnout, and productivity. This includes the use of burnout inventories, salary equity reviews, procedures that track progress toward promotion, and even focus groups of female hospitalists.

2. Inquire about the needs of women in your organization and secure the support they need. This may take the form of including women on key task forces that address personal protective equipment allocation, design new processes, and prepare for surge capacity, as well as providing wellness initiatives, fostering collaborative social networks, or connecting them with emergency childcare resources.

3. Provide a mechanism to account for lack of academic productivity during this time. This period of decreased academic productivity may disproportionately derail progress toward promotion for women. Academic institutions should consider extending deadlines for promotion or tenure, as well as increasing flexibility in metrics used to determine appropriate progress in annual performance reviews.

4. Recognize and reward increased efforts in the areas of clinical or administrative contribution. In this time of crisis, women may be stepping up and leading efforts without titles or positions in ways that are significant and meaningful for their group or organization. Recognizing the ways women are contributing in a tangible and explicit way can provide an avenue for fair compensation, recognition, and career advancement. Female hospitalists should also “manage up” by speaking up and ensuring that leaders are aware of contributions. Amplification is another powerful technique whereby unrecognized contributions can be called out by other women or men.17

5. Support diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts. Keeping equity targets at the top of priority lists for goals moving forward will be imperative. Many institutions struggled to support strong diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts prior to COVID-19; however, the pandemic has highlighted the stark racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist in healthcare.18,19 As healthcare institutions and providers work to mitigate these disparities for patients, there would be no better time to look internally at how they pay, support, and promote their own employees. This would include actively identifying and mitigating any disparities that exist for employees by gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, or disability status.

6. Advocate for fair compensation for providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Frontline clinicians are bearing significant risks and increased workload during this crisis and should be compensated accordingly. Hazard pay, paid sick leave, medical and supplemental life insurance, and strong workers’ compensation protections for hospitalists who become ill at work are important for all clinicians, including women. Other long-term plans should include institutional interventions such as salary corrections and ongoing monitoring.20

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic will have long-term effects that are yet to be realized, including potentially widening gender disparities in medicine. With the current health and economic crises facing our institutions and nations, it can be tempting for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to fall by the wayside. However, it is imperative that hospitalists, leaders, and institutions monitor the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and proactively work to mitigate worsening disparities. Without this focus there is a risk that the recent gains in equity and advancement for women may be lost.

1. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table 13: US medical school faculty by sex, rank, and department, 2017-2018. December 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf

2. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

3. Rouse LP, Nagy-Agren S, Gebhard RE, Bernstein WK. Women physicians: gender and the medical workplace. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(3):297‐309. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7290

4. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

5. Starmer AJ, Frintner MP, Matos K, Somberg C, Freed G, Byrne BJ. Gender discrepancies related to pediatrician work-life balance and household responsibilities. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20182926. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2926

6. Alon TM, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, Tertilt Ml. The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Paper Series. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26947

7. Addati L, Cattaneo U, Esquivel V, Valarino I. Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2018.

8. Maguire P. Should you steer clear of your own family? Hospitalists weigh living in isolation. Today’s Hospitalist. May 2020. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/treating-covid-patients/

9. Burrer SL, de Perio MA, Hughes MM, et al. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 — United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:477-481. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6

10. SHM Teams Up with Hilton and American Express to Provide Hotel Rooms for Members. SHM. April 13, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2020. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/about/press-releases/SHM-One-Million-Beds-Hilton-AMEX/

11. Fichtel C, Kaufman S. Fearing COVID-19 spread to families, health care workers self-isolate at home. NBC News. March 31, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/fearing-covid-19-spread-families-health-care-workers-self-isolate-n1171726

12. Meier KA, Jerardi KE, Statile AM, Shah SS. Pediatric hospital medicine management, staffing, and well-being in the face of COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):308‐310. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3435

13. Frintner MP, Sisk B, Byrne BJ, Freed GL, Starmer AJ, Olson LM. Gender differences in earnings of early- and midcareer pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20183955. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3955

14. Read S, Butkus R, Weissman A, Moyer DV. Compensation disparities by gender in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(9):658-661. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0693

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516‐529. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752

16. Templeton K, Halpern L, Jumper C, Carroll RG. Leading and sustaining curricular change: workshop proceedings from the 2018 Sex and Gender Health Education Summit. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(12):1743-1747. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7387

17. Eilperin J. White House women want to be in the room where it happens. The Washington Post. September 13, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/wp/2016/09/13/white-house-women-are-now-in-the-room-where-it-happens/

18. Choo EK. COVID-19 fault lines. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30812-6

19. Núñez A, Madison M, Schiavo R, Elk R, Prigerson HG. Responding to healthcare disparities and challenges with access to care during COVID-19. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):117-128. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2020.29000.rtl

20. Paturel A. Closing the gender pay gap in medicine. AAMC News. April 16, 2019. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/closing-gender-pay-gap-medicine

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected every facet of our work and personal lives. While many hope we will return to “normal” with the pandemic’s passing, there is reason to believe medicine, and society, will experience irrevocable changes. Although the number of women pursuing and practicing medicine has increased, inequities remain in compensation, academic rank, and leadership positions.1,2 Within the workplace, women are more likely to be in frontline clinical positions, are more likely to be integral in promoting positive interpersonal relationships and collaborative work environments, and often are less represented in the high-level, decision-making roles in leadership or administration.3,4 These well-described issues may be exacerbated during this pandemic crisis. We describe how the current COVID-19 pandemic may intensify workplace inequities for women, and propose solutions for hospitalist groups, leaders, and administrators to ensure female hospitalists continue to prosper and thrive in these tenuous times.

HOW THE PANDEMIC MAY EXACERBATE EXISTING INEQUITIES

Increasing Demands at Home

Female physicians are more likely to have partners who are employed full-time and report spending more time on household activities including cleaning, cooking, and the care of children, compared with their male counterparts.5 With school and daycare closings, as well as stay-at-home orders in many US states, there has been an increase in household responsibilities and care needs for children remaining at home with a marked decrease in options for stable or emergency childcare.6 As compared with primary care and subspecialty colleagues who can provide a large percentage of their care through telemedicine, this is not the case for hospitalists who must be physically present to care for their patients. Therefore, hospitalists are unable to clinically “work from home” in the same way as many of their colleagues in other specialties. Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up.7 In addition, women who are involved with administrative, leadership, or research activities may struggle to execute their responsibilities as a result of increased domestic duties.

Many hospitalists are also concerned about contracting COVID-19 and exposing their families to the illness given the high infection rate among healthcare workers and the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).8,9 Institutions and national organizations, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have partnered with industry to provide discounted or complimentary hotel rooms for members to aid self-isolation while providing clinical care.10 One famous photo in popular and social media showed a pulmonary and critical care physician in a tent in his garage in order to self-isolate from his family.11 However, since women are often the primary caregivers for their children or other family members and may also be responsible for other important household activities, they may be unable or unwilling to remove themselves from their children and families. As a result, female hospitalists may encounter feelings of guilt or inadequacy if they’re unable to isolate in the same manner as male colleagues.8

Exaggerating Leadership Gap

One of the keys to a robust response to this pandemic is strong, thoughtful, and strategic leadership.12 Institutional, regional, and national leaders are at the forefront of designing the solutions to the many problems the COVID-19 pandemic has created. The paucity of women at high-level leadership positions in institutions across the United States, including university-based, community, public, and private institutions, means that there is a lack of female representation when institutional policy is being discussed and decided.4 This lack of representation may lead to policies and procedures that negatively affect female hospitalists or, at best, fail to consider the needs of or support female physicians. For example, leaders of a hospital medicine group may create mandatory “backup” coverage for night and weekend shifts for their group during surge periods of the pandemic without considering implications for childcare. Finding weekday, daytime coverage is challenging for many during this time when daycares and school are closed, and finding coverage during weekend or overnight hours will be even more challenging. With increased risks for older adults with high-risk medical conditions, grandparents or other friends or family members that previously would have assisted with childcare may no longer be an option. If a female hospitalist is not a member of the leadership group that helped design this coverage structure, there could be a lack of recognition of the undue strain this coverage model could create for women in the group. Even if not intentional, such policies may hinder women’s career stability and opportunities for further advancement, as well as their ability to adequately provide care for their families. Having women as a part of the leadership group that creates policies and schedules and makes pivotal decisions is imperative, especially regarding topics of providing access and compensation for “emergency childcare,” hazard pay, shift length, work conditions, job security, sick leave, workers compensation, advancement opportunities, and hiring practices.

Compensation

The gender pay gap in medicine has been consistently demonstrated among many specialties.13,14 The reasons for this inequity are multifactorial, and the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to further widen this gap. With the unequal burden of unpaid care provided by women and their higher prevalence as frontline workers, they are at greater risk of needing to take unpaid leave to care for a sick family member or themselves.6,7 Similarly, without hazard pay, those with direct clinical responsibilities bear the risk of illness for themselves and their families without adequate compensation.

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

The overall well-being of the hospitalist workforce is critical to continue to provide the highest level of care for our patients. With higher workloads at home and at work, female hospitalists are at risk for increased burnout. Burnout has been linked to many negative outcomes including poor performance, depression, suicide, and leaving the profession.15 Burnout is documented to be higher in female physicians with several contributing factors that are aggravated by gender inequities, including having children at home, gender bias, and real or perceived lack of fairness in promotion and compensation.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the stress of having children in the home, as well as concerns around fair compensation as described above. The consequences of this have yet to be fully realized but may be dire.

PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS

We propose the following recommendations to help mitigate the effects of this epidemic and to continue to move our field forward on our path to equity.

1. Closely monitor the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists. While there has been a recent increase in scholarship on the pre–COVID-19 state of gender disparities, there is still much that is unknown. As we experience this upheaval in the way our institutions function, it is even more imperative to track gender deaggregated key indicators of wellness, burnout, and productivity. This includes the use of burnout inventories, salary equity reviews, procedures that track progress toward promotion, and even focus groups of female hospitalists.

2. Inquire about the needs of women in your organization and secure the support they need. This may take the form of including women on key task forces that address personal protective equipment allocation, design new processes, and prepare for surge capacity, as well as providing wellness initiatives, fostering collaborative social networks, or connecting them with emergency childcare resources.

3. Provide a mechanism to account for lack of academic productivity during this time. This period of decreased academic productivity may disproportionately derail progress toward promotion for women. Academic institutions should consider extending deadlines for promotion or tenure, as well as increasing flexibility in metrics used to determine appropriate progress in annual performance reviews.

4. Recognize and reward increased efforts in the areas of clinical or administrative contribution. In this time of crisis, women may be stepping up and leading efforts without titles or positions in ways that are significant and meaningful for their group or organization. Recognizing the ways women are contributing in a tangible and explicit way can provide an avenue for fair compensation, recognition, and career advancement. Female hospitalists should also “manage up” by speaking up and ensuring that leaders are aware of contributions. Amplification is another powerful technique whereby unrecognized contributions can be called out by other women or men.17

5. Support diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts. Keeping equity targets at the top of priority lists for goals moving forward will be imperative. Many institutions struggled to support strong diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts prior to COVID-19; however, the pandemic has highlighted the stark racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist in healthcare.18,19 As healthcare institutions and providers work to mitigate these disparities for patients, there would be no better time to look internally at how they pay, support, and promote their own employees. This would include actively identifying and mitigating any disparities that exist for employees by gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, or disability status.

6. Advocate for fair compensation for providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Frontline clinicians are bearing significant risks and increased workload during this crisis and should be compensated accordingly. Hazard pay, paid sick leave, medical and supplemental life insurance, and strong workers’ compensation protections for hospitalists who become ill at work are important for all clinicians, including women. Other long-term plans should include institutional interventions such as salary corrections and ongoing monitoring.20

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic will have long-term effects that are yet to be realized, including potentially widening gender disparities in medicine. With the current health and economic crises facing our institutions and nations, it can be tempting for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to fall by the wayside. However, it is imperative that hospitalists, leaders, and institutions monitor the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and proactively work to mitigate worsening disparities. Without this focus there is a risk that the recent gains in equity and advancement for women may be lost.

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected every facet of our work and personal lives. While many hope we will return to “normal” with the pandemic’s passing, there is reason to believe medicine, and society, will experience irrevocable changes. Although the number of women pursuing and practicing medicine has increased, inequities remain in compensation, academic rank, and leadership positions.1,2 Within the workplace, women are more likely to be in frontline clinical positions, are more likely to be integral in promoting positive interpersonal relationships and collaborative work environments, and often are less represented in the high-level, decision-making roles in leadership or administration.3,4 These well-described issues may be exacerbated during this pandemic crisis. We describe how the current COVID-19 pandemic may intensify workplace inequities for women, and propose solutions for hospitalist groups, leaders, and administrators to ensure female hospitalists continue to prosper and thrive in these tenuous times.

HOW THE PANDEMIC MAY EXACERBATE EXISTING INEQUITIES

Increasing Demands at Home

Female physicians are more likely to have partners who are employed full-time and report spending more time on household activities including cleaning, cooking, and the care of children, compared with their male counterparts.5 With school and daycare closings, as well as stay-at-home orders in many US states, there has been an increase in household responsibilities and care needs for children remaining at home with a marked decrease in options for stable or emergency childcare.6 As compared with primary care and subspecialty colleagues who can provide a large percentage of their care through telemedicine, this is not the case for hospitalists who must be physically present to care for their patients. Therefore, hospitalists are unable to clinically “work from home” in the same way as many of their colleagues in other specialties. Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up.7 In addition, women who are involved with administrative, leadership, or research activities may struggle to execute their responsibilities as a result of increased domestic duties.

Many hospitalists are also concerned about contracting COVID-19 and exposing their families to the illness given the high infection rate among healthcare workers and the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).8,9 Institutions and national organizations, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have partnered with industry to provide discounted or complimentary hotel rooms for members to aid self-isolation while providing clinical care.10 One famous photo in popular and social media showed a pulmonary and critical care physician in a tent in his garage in order to self-isolate from his family.11 However, since women are often the primary caregivers for their children or other family members and may also be responsible for other important household activities, they may be unable or unwilling to remove themselves from their children and families. As a result, female hospitalists may encounter feelings of guilt or inadequacy if they’re unable to isolate in the same manner as male colleagues.8

Exaggerating Leadership Gap

One of the keys to a robust response to this pandemic is strong, thoughtful, and strategic leadership.12 Institutional, regional, and national leaders are at the forefront of designing the solutions to the many problems the COVID-19 pandemic has created. The paucity of women at high-level leadership positions in institutions across the United States, including university-based, community, public, and private institutions, means that there is a lack of female representation when institutional policy is being discussed and decided.4 This lack of representation may lead to policies and procedures that negatively affect female hospitalists or, at best, fail to consider the needs of or support female physicians. For example, leaders of a hospital medicine group may create mandatory “backup” coverage for night and weekend shifts for their group during surge periods of the pandemic without considering implications for childcare. Finding weekday, daytime coverage is challenging for many during this time when daycares and school are closed, and finding coverage during weekend or overnight hours will be even more challenging. With increased risks for older adults with high-risk medical conditions, grandparents or other friends or family members that previously would have assisted with childcare may no longer be an option. If a female hospitalist is not a member of the leadership group that helped design this coverage structure, there could be a lack of recognition of the undue strain this coverage model could create for women in the group. Even if not intentional, such policies may hinder women’s career stability and opportunities for further advancement, as well as their ability to adequately provide care for their families. Having women as a part of the leadership group that creates policies and schedules and makes pivotal decisions is imperative, especially regarding topics of providing access and compensation for “emergency childcare,” hazard pay, shift length, work conditions, job security, sick leave, workers compensation, advancement opportunities, and hiring practices.

Compensation

The gender pay gap in medicine has been consistently demonstrated among many specialties.13,14 The reasons for this inequity are multifactorial, and the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to further widen this gap. With the unequal burden of unpaid care provided by women and their higher prevalence as frontline workers, they are at greater risk of needing to take unpaid leave to care for a sick family member or themselves.6,7 Similarly, without hazard pay, those with direct clinical responsibilities bear the risk of illness for themselves and their families without adequate compensation.

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

The overall well-being of the hospitalist workforce is critical to continue to provide the highest level of care for our patients. With higher workloads at home and at work, female hospitalists are at risk for increased burnout. Burnout has been linked to many negative outcomes including poor performance, depression, suicide, and leaving the profession.15 Burnout is documented to be higher in female physicians with several contributing factors that are aggravated by gender inequities, including having children at home, gender bias, and real or perceived lack of fairness in promotion and compensation.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the stress of having children in the home, as well as concerns around fair compensation as described above. The consequences of this have yet to be fully realized but may be dire.

PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS

We propose the following recommendations to help mitigate the effects of this epidemic and to continue to move our field forward on our path to equity.

1. Closely monitor the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on female hospitalists. While there has been a recent increase in scholarship on the pre–COVID-19 state of gender disparities, there is still much that is unknown. As we experience this upheaval in the way our institutions function, it is even more imperative to track gender deaggregated key indicators of wellness, burnout, and productivity. This includes the use of burnout inventories, salary equity reviews, procedures that track progress toward promotion, and even focus groups of female hospitalists.

2. Inquire about the needs of women in your organization and secure the support they need. This may take the form of including women on key task forces that address personal protective equipment allocation, design new processes, and prepare for surge capacity, as well as providing wellness initiatives, fostering collaborative social networks, or connecting them with emergency childcare resources.

3. Provide a mechanism to account for lack of academic productivity during this time. This period of decreased academic productivity may disproportionately derail progress toward promotion for women. Academic institutions should consider extending deadlines for promotion or tenure, as well as increasing flexibility in metrics used to determine appropriate progress in annual performance reviews.

4. Recognize and reward increased efforts in the areas of clinical or administrative contribution. In this time of crisis, women may be stepping up and leading efforts without titles or positions in ways that are significant and meaningful for their group or organization. Recognizing the ways women are contributing in a tangible and explicit way can provide an avenue for fair compensation, recognition, and career advancement. Female hospitalists should also “manage up” by speaking up and ensuring that leaders are aware of contributions. Amplification is another powerful technique whereby unrecognized contributions can be called out by other women or men.17

5. Support diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts. Keeping equity targets at the top of priority lists for goals moving forward will be imperative. Many institutions struggled to support strong diversity, inclusion, and equity efforts prior to COVID-19; however, the pandemic has highlighted the stark racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist in healthcare.18,19 As healthcare institutions and providers work to mitigate these disparities for patients, there would be no better time to look internally at how they pay, support, and promote their own employees. This would include actively identifying and mitigating any disparities that exist for employees by gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, or disability status.

6. Advocate for fair compensation for providers caring for COVID-19 patients. Frontline clinicians are bearing significant risks and increased workload during this crisis and should be compensated accordingly. Hazard pay, paid sick leave, medical and supplemental life insurance, and strong workers’ compensation protections for hospitalists who become ill at work are important for all clinicians, including women. Other long-term plans should include institutional interventions such as salary corrections and ongoing monitoring.20

SUMMARY

The COVID-19 pandemic will have long-term effects that are yet to be realized, including potentially widening gender disparities in medicine. With the current health and economic crises facing our institutions and nations, it can be tempting for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to fall by the wayside. However, it is imperative that hospitalists, leaders, and institutions monitor the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and proactively work to mitigate worsening disparities. Without this focus there is a risk that the recent gains in equity and advancement for women may be lost.

1. Association of American Medical Colleges. Table 13: US medical school faculty by sex, rank, and department, 2017-2018. December 31, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf

2. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

3. Rouse LP, Nagy-Agren S, Gebhard RE, Bernstein WK. Women physicians: gender and the medical workplace. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(3):297‐309. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7290

4. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

5. Starmer AJ, Frintner MP, Matos K, Somberg C, Freed G, Byrne BJ. Gender discrepancies related to pediatrician work-life balance and household responsibilities. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20182926. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2926

6. Alon TM, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, Tertilt Ml. The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Paper Series. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26947

7. Addati L, Cattaneo U, Esquivel V, Valarino I. Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2018.

8. Maguire P. Should you steer clear of your own family? Hospitalists weigh living in isolation. Today’s Hospitalist. May 2020. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/treating-covid-patients/

9. Burrer SL, de Perio MA, Hughes MM, et al. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 — United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:477-481. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6

10. SHM Teams Up with Hilton and American Express to Provide Hotel Rooms for Members. SHM. April 13, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2020. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/about/press-releases/SHM-One-Million-Beds-Hilton-AMEX/

11. Fichtel C, Kaufman S. Fearing COVID-19 spread to families, health care workers self-isolate at home. NBC News. March 31, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/fearing-covid-19-spread-families-health-care-workers-self-isolate-n1171726

12. Meier KA, Jerardi KE, Statile AM, Shah SS. Pediatric hospital medicine management, staffing, and well-being in the face of COVID-19. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(5):308‐310. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3435

13. Frintner MP, Sisk B, Byrne BJ, Freed GL, Starmer AJ, Olson LM. Gender differences in earnings of early- and midcareer pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20183955. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3955

14. Read S, Butkus R, Weissman A, Moyer DV. Compensation disparities by gender in internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(9):658-661. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0693

15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516‐529. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752

16. Templeton K, Halpern L, Jumper C, Carroll RG. Leading and sustaining curricular change: workshop proceedings from the 2018 Sex and Gender Health Education Summit. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(12):1743-1747. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7387

17. Eilperin J. White House women want to be in the room where it happens. The Washington Post. September 13, 2016. Accessed April 24, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/wp/2016/09/13/white-house-women-are-now-in-the-room-where-it-happens/

18. Choo EK. COVID-19 fault lines. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30812-6

19. Núñez A, Madison M, Schiavo R, Elk R, Prigerson HG. Responding to healthcare disparities and challenges with access to care during COVID-19. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):117-128. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2020.29000.rtl

20. Paturel A. Closing the gender pay gap in medicine. AAMC News. April 16, 2019. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/closing-gender-pay-gap-medicine