User login

Identifying and Supporting the Needs of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Residents Interested in Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowship

The American Board of Medical Specialties approved subspecialty designation for the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) in 2016.1 For those who started independent practice prior to July 2019, there were two options for board eligibility: the “practice pathway” or completion of a PHM fellowship. The practice pathway allows for pediatric and combined internal medicine–pediatric (med-peds) providers who graduated by July 2019 to sit for the PHM board-certification examination if they meet specific criteria in their pediatric practice.2 For pediatric and med-peds residents who graduated after July 2019, PHM board eligibility is available only through completion of a PHM fellowship.

PHM subspecialty designation with fellowship training requirements may pose unique challenges to med-peds residents interested in practicing both pediatric and adult hospital medicine (HM).3,4 Each year, an estimated 25% of med-peds residency graduates go on to practice HM.5 The majority (62%-83%) of currently practicing med-peds–trained hospitalists care for both adults and children.5,6 Further, med-peds–trained hospitalists comprise at least 10% of the PHM workforce5 and play an important role in caring for adult survivors of childhood diseases.3

Limited existing data suggest that the future practice patterns of med-peds residents may be affected by PHM fellowship requirements. One previous survey study indicated that, although med-peds residents see value in additional training opportunities offered by fellowship, the majority are less likely to pursue PHM as a result of the new requirements.4 Prominent factors dissuading residents from pursuing PHM fellowship included forfeited earnings during fellowship, student loan obligations, family obligations, and the perception that training received during residency was sufficient. Although these data provide important insights into potential changes in practice patterns, they do not explore qualities of PHM fellowship that may make additional training more appealing to med-peds residents and promote retention of med-peds–trained providers in the PHM workforce.

Further, there is no existing literature exploring if and how PHM fellowship programs are equipped to support the needs of med-peds–trained fellows. Other subspecialties have supported med-peds trainees in combined fellowship training programs, including rheumatology, neurology, pediatric emergency medicine, allergy/immunology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and psychiatry.7,8 However, the extent to which PHM fellowships follow a similar model to accommodate the career goals of med-peds participants is unclear.

Given the large numbers of med-peds residents who go on to practice combined PHM and adult HM, it is crucial to understand the training needs of this group within the context of PHM fellowship and board certification. The primary objectives of this study were to understand (1) the perceived PHM fellowship needs of med-peds residents interested in HM, and (2) how the current PHM fellowship training environment can meet those needs. Understanding that additional training requirements to practice PHM may affect the career trajectory of residents interested in HM, secondary objectives included describing perceptions of med-peds residents on PHM specialty designation and whether designation affected their career plans.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study took place over a 3-month period from May to July 2019 and included two surveys of different populations to develop a comprehensive understanding of stakeholder perceptions of PHM fellowship. The first survey (resident survey) invited med-peds residents who were members of the National Med-Peds Residents’ Association (NMPRA)9 in 2019 and who were interested in HM. The second survey (fellowship director [FD] survey) included PHM FDs. The study was determined to be exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Study Population and Recruitment

Resident Survey

Two attempts were made to elicit participation via the NMPRA electronic mailing list. The NMPRA membership includes med-peds residents and chief residents from US med-peds residency programs. As of May 2019, 77 med-peds residency programs and their residents were members of NMPRA, which encompassed all med-peds programs in the United States and its territories. NMPRA maintains a listserv for all members, and all existing US/territory programs were members at the time of the survey. Med-peds interns, residents, and chief residents interested in HM were invited to participate in this study.

FD Survey

Forty-eight FDs, representing member institutions of the PHM Fellowship Directors’ Council, were surveyed via the PHM Fellowship Directors listserv.

Survey Instruments

We constructed two de novo surveys consisting of multiple-choice and short-answer questions (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). To enhance the validity of survey responses, questions were designed and tested using an iterative consensus process among authors and additional participants, including current med-peds PHM fellows, PHM fellowship program directors, med-peds residency program directors, and current med-peds residents. These revisions were repeated for a total of four cycles. Items were created to increase knowledge on the following key areas: resident-perceived needs in fellowship training, impact of PHM subspecialty designation on career choices related to HM, health system structure of fellowship programs, and ability to accommodate med-peds clinical training within a PHM fellowship. A combined med-peds fellowship, as defined in the survey and referenced in this study, is a “combined internal medicine–pediatrics hospital medicine fellowship whereby you would remain eligible for PHM board certification.” To ensure a broad and inclusive view of potential needs of med-peds trainees considering fellowship, all respondents were asked to complete questions pertaining to anticipated fellowship needs regardless of their indicated interest in fellowship.

Data Collection

Survey completion was voluntary. Email identifiers were not linked to completed surveys. Study data were collected and managed by using Qualtrics XM. Only completed survey entries were included in analysis.

Statistical Methods and Data Analysis

R software version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for statistical analysis. Demographic data were summarized using frequency distributions. The intent of the free-text questions for both surveys was qualitative explanatory thematic analysis. Authors EB, HL, and AJ used a deductive approach to identify common themes that elucidated med-peds resident–anticipated needs in fellowship and PHM program strategies and barriers to accommodate these needs. Preliminary themes and action items were reviewed and discussed among the full authorship team until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

Resident Survey

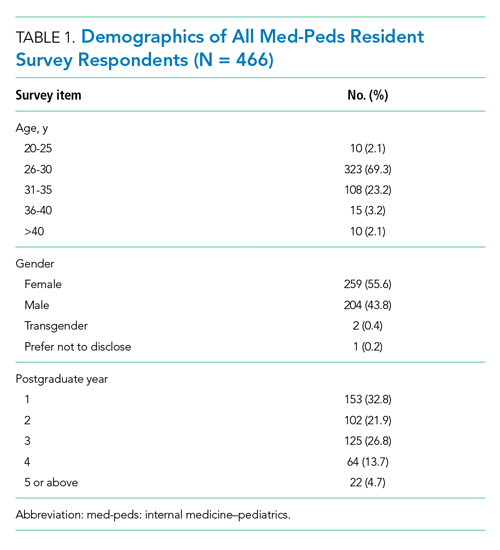

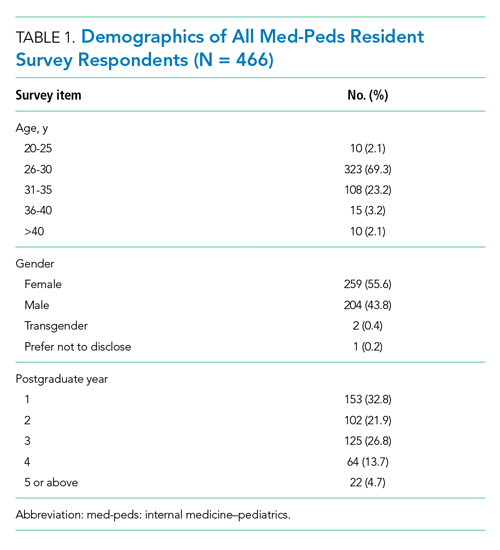

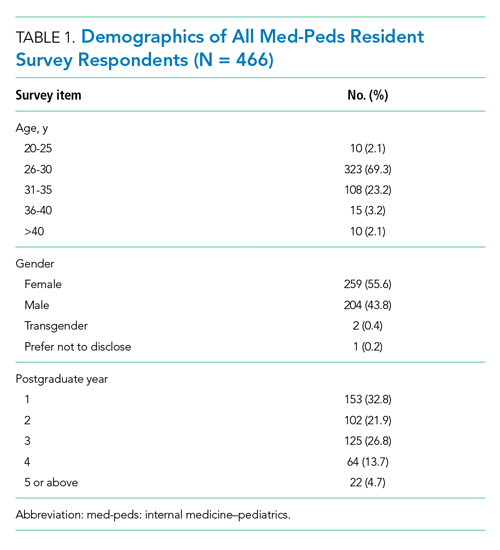

A total of 466 med-peds residents completed the resident survey. There are approximately 1300 med-peds residents annually, creating an estimated response rate of 35.8% of all US med-peds residents. The majority (n = 380, 81.5%) of respondents were med-peds postgraduate years 1 through 3 and thus only eligible for PHM board certification via the PHM fellowship pathway (Table 1). Most (n = 446, 95.7%) respondents had considered a career in adult, pediatric, or combined HM at some point. Of those med-peds residents who considered a career in HM (Appendix Table 1), 92.8% (n = 414) would prefer to practice combined adult HM and PHM.

FD Survey

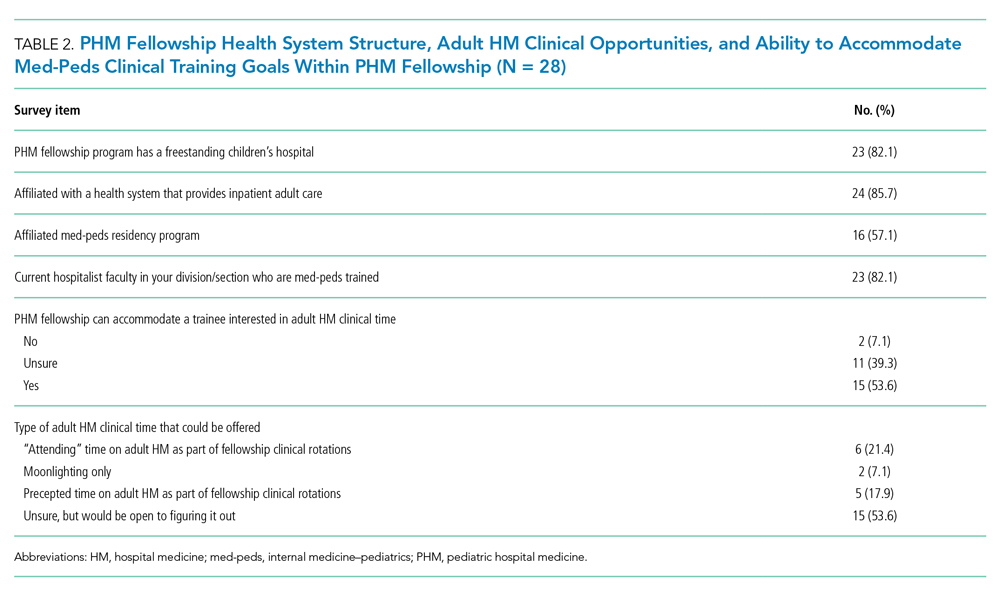

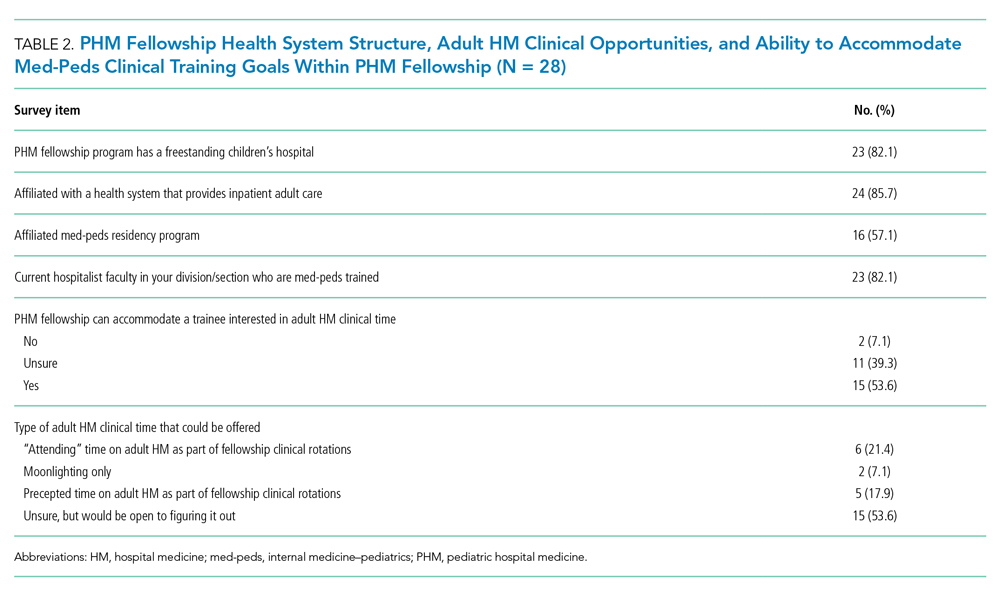

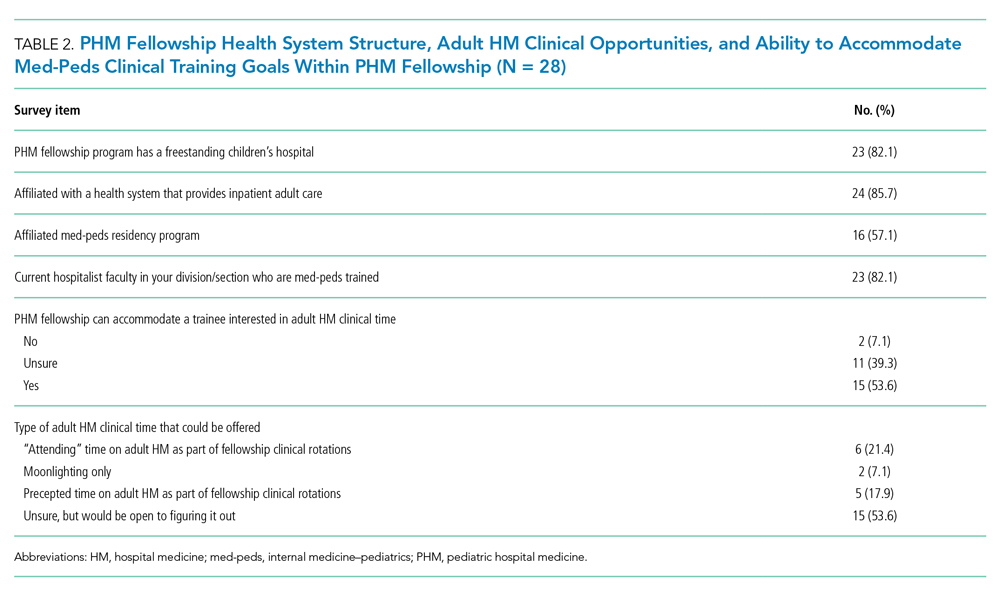

Twenty-eight FDs completed the FD survey, representing 58.3% of 2019 PHM fellowship programs. Of the responding programs, 23 (82.1%) were associated with a freestanding children’s hospital, and 24 (85.7%) were integrated or affiliated with a health system that provides adult inpatient care (Table 2). Sixteen (57.1%) programs had a med-peds residency program at their institution.

Med-Peds Resident Perceptions of PHM Fellowship

In considering the importance of PHM board certification for physicians practicing PHM, 59.0% (n= 275) of respondents rated board certification as “not at all important” (Appendix Table 2). Most (n = 420, 90.1%) med-peds trainees responded that PHM subspecialty designation “decreased” or “significantly decreased” their desire to pursue a career that includes PHM. Of the respondents who reported no interest in hospital medicine, eight (40%) reported that PHM subspecialty status dissuaded them from a career in HM at least a moderate amount (Appendix Table 3). Roughly one third (n=158, 33.9%) of respondents reported that PHM subspecialty designation increased or significantly increased their desire to pursue a career that includes adult HM (Appenidx Table 2). Finally, although the majority (n = 275, 59%) of respondents said they had no interest in a HM fellowship, 114 (24.5%) indicated interest in a combined med-peds HM fellowship (Appendix Table 1). Short-answer questions revealed that commitment to additional training on top of a 4-year residency program was a possible deterring factor, particularly in light of student loan debt and family obligations. Respondents reported adequate clinical training during residency as another deterring factor.

Med-Peds Resident–Perceived Needs in PHM Fellowship

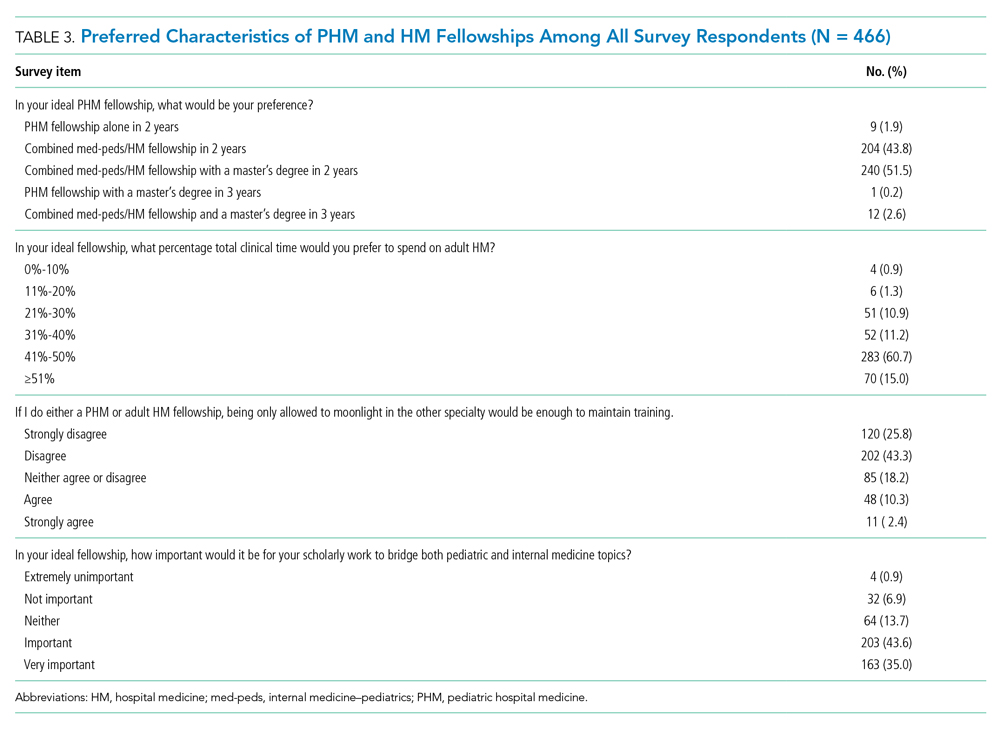

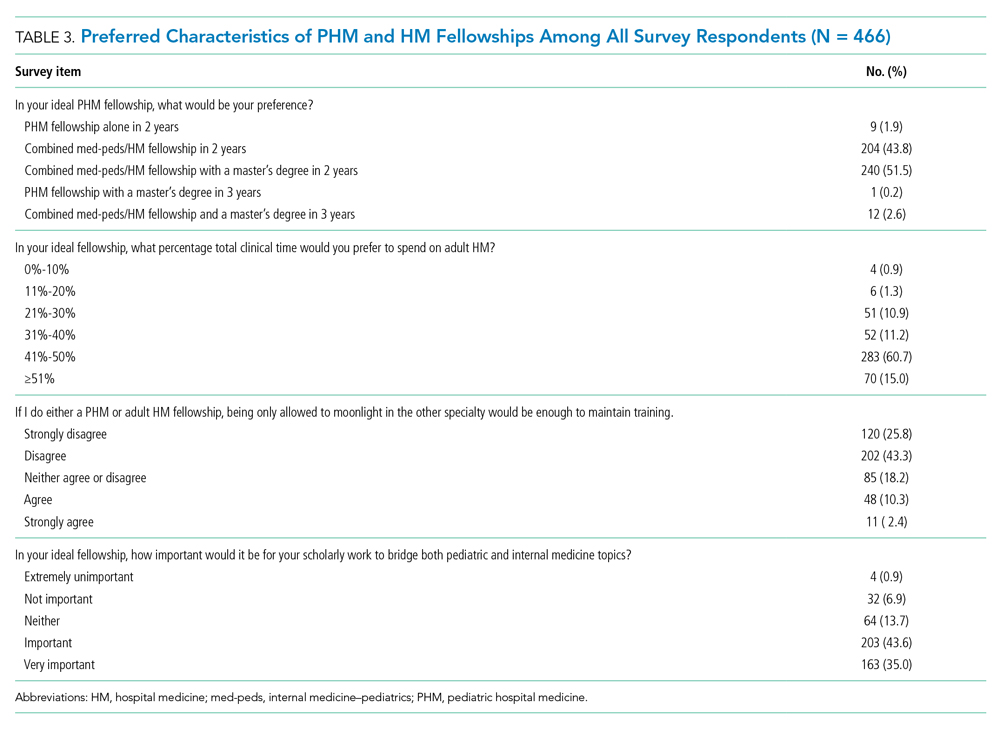

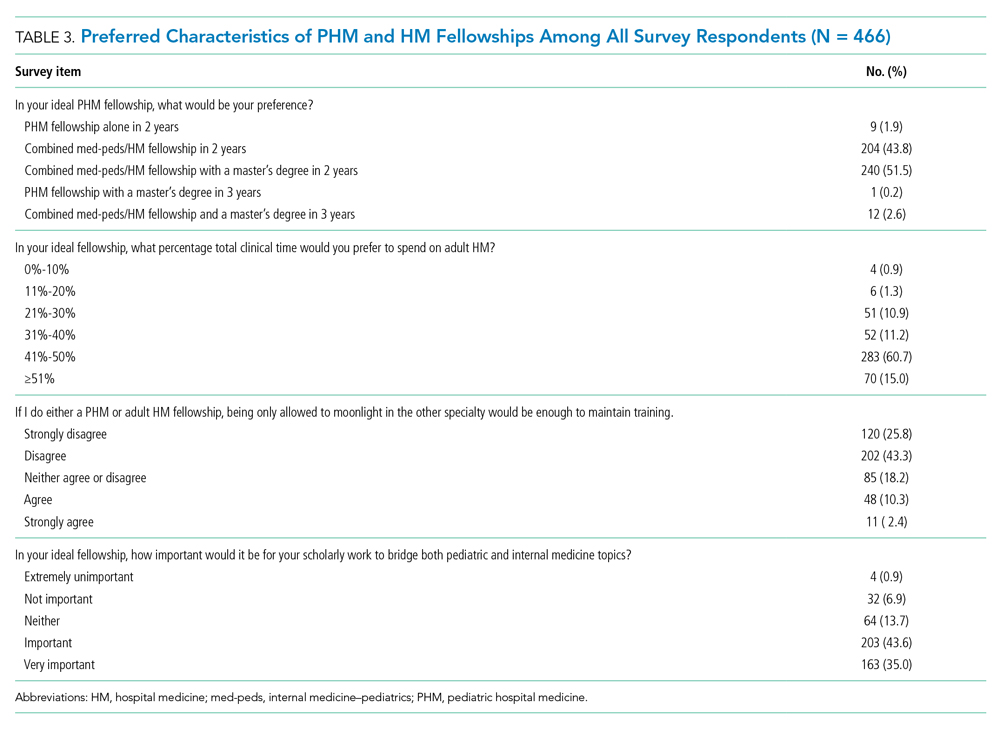

Regardless of interest in completing a PHM fellowship, all resident survey respondents were asked how their ideal PHM fellowship should be structured. Almost all (n = 456, 97.9%) respondents indicated that they would prefer to complete a combined med-peds HM fellowship (Table 3), and most preferred to complete a fellowship in 2 years. Only 10 (2.1%) respondents preferred to complete a PHM fellowship alone in 2 or 3 years. More than half (n=253, 54.3%) of respondents indicated that it would be ideal to obtain a master’s degree as part of fellowship.

Three quarters (n = 355, 75.8%) of med-peds residents reported that they would want 41% or more of clinical time in an ideal fellowship dedicated to adult HM. Importantly, most (n = 322, 69.1%) of the med-peds residents did not consider moonlighting alone in either PHM or adult HM to be enough to maintain training. In addition, many (n = 366, 78.5%) respondents felt that it was important or very important for scholarly work during fellowship to bridge pediatrics and internal medicine.

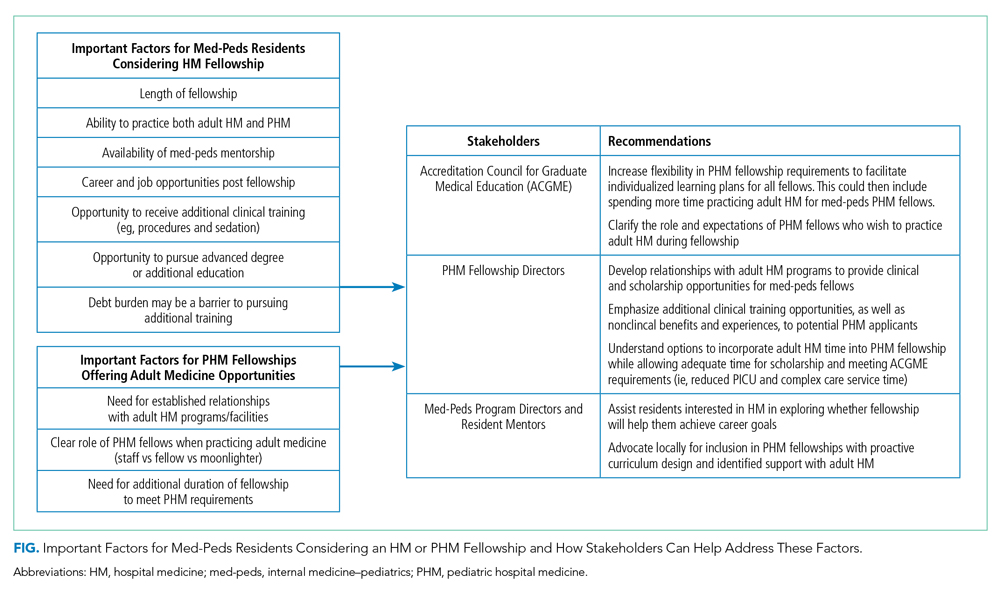

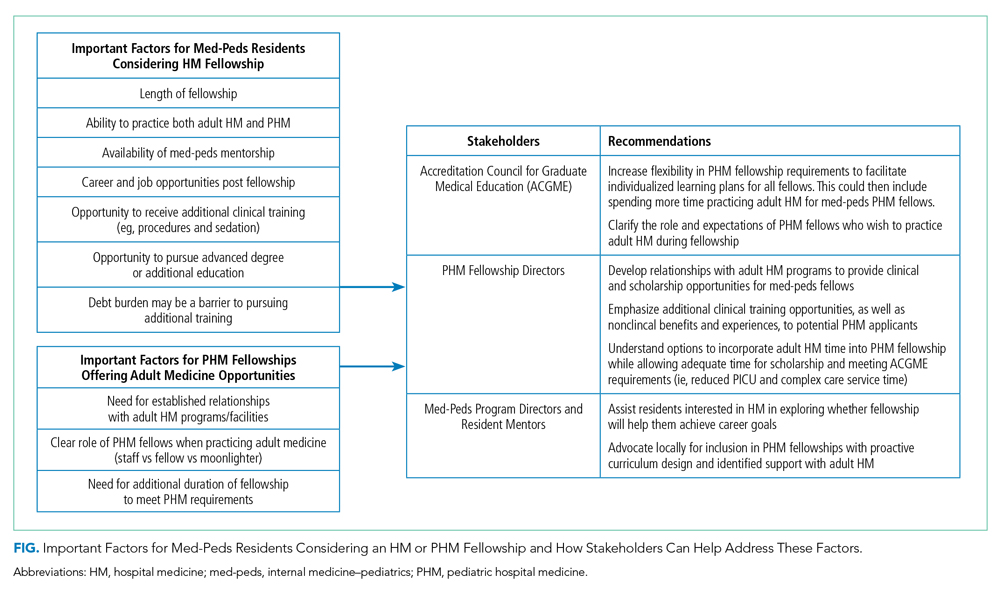

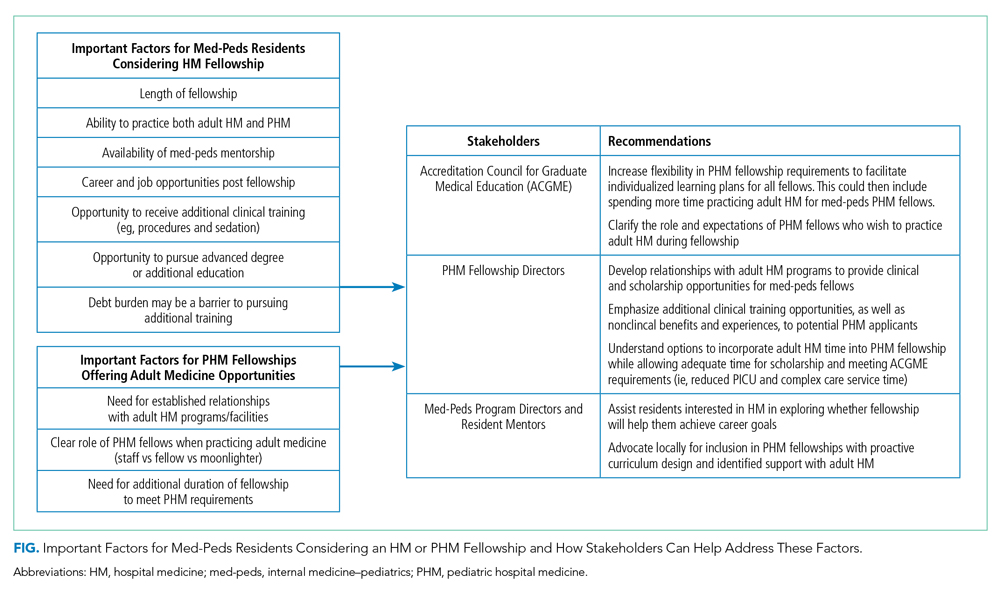

Short-answer questions indicated that the ability to practice both internal medicine and pediatrics during fellowship emerged as an important deciding factor, with emphasis on adequate opportunities to maintain internal medicine knowledge base (Figure). Similarly, access to med-peds mentorship was an important component of the decision. Compensation both during fellowship and potential future earnings was also a prominent consideration.

Capacity of PHM Programs to Support Med-Peds Fellows

Fifteen (53.6%) FDs reported that their programs were able to accommodate both PHM and adult HM clinical time during fellowship, 11 (39.3%) were unsure, and 2 (7.1%) were unable to accommodate both (Table 2).

The options for adult HM clinical time varied by institution and included precepted time on adult HM, full attending privileges on adult HM, and adult HM time through moonlighting only. Short-answer responses from FDs with experience training med-peds fellows cited using PHM elective time for adult HM and offering moonlighting in adult HM as ways to address career goals of med-peds trainees. Scholarship time for fellows was preserved by decreasing required time on pediatric intensive care unit and complex care services.

Accessibility of Med-Peds Mentorship

As noted above, med-peds residents identified mentorship as an important factor in consideration of PHM fellowship. A total of 23 (82.1%) FDs reported their programs had med-peds faculty members within their PHM team (Table 2). The majority (n = 21, 91.3%) of those med-peds faculty had both PHM and adult HM clinical time.

DISCUSSION

This study characterized the ideal PHM fellowship structure from the perspective of med-peds residents and described the current ability of PHM fellowships to support med-peds residents. The majority of residents stated that they had no interest in an HM fellowship. However, for med-peds residents who considered a career in HM, 88.8% preferred to complete a combined internal medicine and pediatrics HM fellowship with close to half of clinical time dedicated to adult HM. Just over half (53.6%) of programs reported that they could currently accommodate both PHM and adult clinical time during fellowship, and all but two programs reported that they could accommodate both PHM and HM time in the future.

PHM subspecialty designation with associated fellowship training requirements decreased desire to practice HM among med-peds residents who responded to our survey. This reflects findings from a recently published study that evaluated whether PHM fellowship requirements for board certification influenced pediatric and med-peds residents’ decision to pursue PHM in 2018.4 Additionally, Chandrasekar et al4 found that 87% of respondents indicated that sufficient residency training was an important factor in discouraging them from pursuing PHM fellowship. We noted similar findings in our open-ended survey responses, which indicate that med-peds respondents perceived that the intended purpose of PHM fellowship was to provide additional clinical training, and that served as a deterrent for fellowship. However, the survey by Chandrasekar et al4 assessed only four factors for understanding what was important in encouraging pursuit of a PHM fellowship: opportunity to gain new skills, potential increase in salary, opportunity for a master’s degree, and increased prestige. Our survey expands on med-peds residents’ needs, indicating that med-peds residents want a combined med-peds/HM fellowship that allows them to meet PHM board-eligibility requirements while also continuing to develop their adult HM clinical practice and other nonclinical training objectives in a way that combines both adult HM and PHM. Both surveys demonstrate the role that residency program directors and other resident mentors can have in counseling trainees on the nonclinical training objectives of PHM fellowship, including research, quality improvement, medical education, and leadership and clinical operations. Additional emphasis can be placed on opportunities for an individualized curriculum to address the specific career aims of each resident.

In this study, med-peds trainees viewed distribution of clinical time during fellowship as an important factor in pursuing PHM fellowship. The perceived importance of balancing clinical time is not surprising considering that most survey respondents interested in HM ultimately intend to practice both PHM and adult HM. This finding corresponds with current practice patterns of med-peds hospitalists, the majority of whom care for both children and adults.4,5 Moonlighting in adult medicine was not considered sufficient, suggesting desire for mentorship and training integration on the internal medicine side. Opportunities for trainees to maintain and expand their internal medicine knowledge base and clinical decision-making outside of moonlighting will be key to meeting the needs of med-peds residents in PHM fellowship.

Fortunately, more than half of responding programs reported that they could allow for adult HM practice during PHM fellowship. Twelve programs were unsure if they could accommodate adult HM clinical time, and only two programs reported they could not. We suspect that the ability to support this training with clinical time in both adult HM and PHM is more likely available at programs with established internal medicine relationships, often in the form of med-peds residency programs and med-peds faculty. Further, these established relationships may be more common at pediatric health systems that are integrated or affiliated with an adult health system. Most PHM fellowships surveyed indicated that their pediatric institution had an affiliation with an adult facility, and most had med-peds HM faculty.

Precedent for supporting med-peds fellows is somewhat limited given that only five of the responding PHM fellowship programs reported having fellows with med-peds residency training. However, discrepancies between the expressed needs of med-peds residents and the current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited PHM fellowship structure highlight opportunities to tailor fellowship training to support the career goals of med-peds residents. The current PHM fellowship structure consists of 26 educational units, with each unit representing 4 calendar weeks. A minimum of eight units are spent on each of the following: core clinical rotations, systems and scholarship, and individualized curriculum.10,11 The Society of Hospital Medicine has published core competencies for both PHM and adult HM, which highlight significant overlap in each field’s skill competency, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, legal issues and risk management, and handoffs and transitions of care.12,13 We contend that competencies addressed within PHM fellowship core clinical rotations may overlap with adult HM. Training in adult HM could be completed as part of the individualized curriculum with the ACGME, allowing adult HM practice to count toward this requirement. This would offer med-peds fellows the option to maintain their adult HM knowledge base without eliminating all elective time. Ultimately, it will be important to be creative in how training is accomplished and skills are acquired during both core clinical and individualized training blocks for med-peds trainees completing PHM fellowship.

In order to meet the expressed needs of med-peds residents interested in incorporating both adult HM and PHM into their future careers through PHM fellowship, we offer key recommendations for consideration by the ACGME, PHM FDs, and med-peds program directors (Figure). We encourage current PHM fellowship programs to establish relationships with adult HM programs to develop structured clinical opportunities that will allow fellows to gain the additional clinical training desired.

There were important limitations in this study. First, our estimated response rate for the resident survey was 35.8% of all med-peds residents in 2019, which may be interpreted as low. However, it is important to note that the survey was targeted to residents interested in HM. More than 25% of med-peds residents pursue a career in HM,5 suggesting our response rate may be attributed to residents who did not complete the survey because they were interested in other fields. The program director survey response rate was higher at 58.3%, though it is possible that response bias resulted in a higher response rate from programs with the ability to support med-peds trainees. Regardless, data from programs with the ability to support med-peds trainees are highly valuable in describing how PHM fellowship can be inclusive of med-peds–trained physicians interested in pursuing HM.

Both surveys were completed in 2019, prior to the ACGME accreditation of PHM fellowship, which likely presents new, unique challenges to fellowship programs trying to support the needs of med-peds fellows. However, insights noted above from programs with experience training med-peds fellows are still applicable within the constraints of ACGME requirements.

CONCLUSION

Many med-peds residents express strong interest in practicing HM and including PHM as part of their future hospitalist practice. With the introduction of PHM subspecialty board certification through the American Board of Pediatrics, med-peds residents face new considerations when choosing a career path after residency. The majority of resident respondents express the desire to spend a substantial portion of their clinical practice and/or fellowship practicing adult HM. A majority of PHM fellowships can or are willing to explore how to provide both pediatric and adult hospitalist training to med-peds residency–trained fellows. Understanding the facilitators and barriers to recruiting med-peds trainees for PHM fellowship ultimately has significant implications for the future of the PHM workforce. Incorporating the recommendations noted in this study may increase retention of med-peds providers in PHM by enabling fellowship training and ultimately board certification. Collaboration among the ACGME, PHM program directors, and med-peds residency program directors could help to develop PHM fellowship training programs that will meet the needs of med-peds residents interested in practicing PHM while still meeting ACGME requirements for PHM board eligibility.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Anoop Agrawal of National Med-Peds Residents’ Association (NMPRA).

1. Blankenburg B, Bode R, Carlson D, et al. National Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leaders Conference. Published April 4, 2013. https://medpeds.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PediatricHospitalMedicineCertificationMeeting_Update.pdf

2. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. Revised December 18, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification

3. Feldman LS, Monash B, Eniasivam A, Chang W. Why required pediatric hospital medicine fellowships are unnecessary. Hospitalist. 2016;10. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/121461/pediatrics/why-required-pediatric-hospital-medicine-fellowships-are

4. Chandrasekar H, White YN, Ribeiro C, Landrigan CP, Marcus CH. A changing landscape: exploring resident perspectives on pursuing pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(2):109-115. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0034

5. O’Toole JK, Friedland AR, Gonzaga AMR, et al. The practice patterns of recently graduated internal medicine-pediatric hospitalists. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(6):309-314. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0135

6. Donnelly MJ, Lubrano L, Radabaugh CL, Lukela MP, Friedland AR, Ruch-Ross HS. The med-peds hospitalist workforce: results from the American Academy of Pediatrics Workforce Survey. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):574-579. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0031

7. Patwardhan A, Henrickson M, Laskosz L, Duyenhong S, Spencer CH. Current pediatric rheumatology fellowship training in the United States: what fellows actually do. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-8

8. Howell E, Kravet S, Kisuule F, Wright SM. An innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):314-318. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.327

9. The National Med-Peds Residents’ Association. About. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://medpeds.org/about-nmpra/

10. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698

11. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Pediatr Hosp Med. Published online July 1, 2020:55.

12. Maniscalco J, Gage S, Teferi S, Fisher ES. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies: 2020 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389-394. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3391

13. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine--2017 Revision: Introduction and Methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):283-287. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2715

The American Board of Medical Specialties approved subspecialty designation for the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) in 2016.1 For those who started independent practice prior to July 2019, there were two options for board eligibility: the “practice pathway” or completion of a PHM fellowship. The practice pathway allows for pediatric and combined internal medicine–pediatric (med-peds) providers who graduated by July 2019 to sit for the PHM board-certification examination if they meet specific criteria in their pediatric practice.2 For pediatric and med-peds residents who graduated after July 2019, PHM board eligibility is available only through completion of a PHM fellowship.

PHM subspecialty designation with fellowship training requirements may pose unique challenges to med-peds residents interested in practicing both pediatric and adult hospital medicine (HM).3,4 Each year, an estimated 25% of med-peds residency graduates go on to practice HM.5 The majority (62%-83%) of currently practicing med-peds–trained hospitalists care for both adults and children.5,6 Further, med-peds–trained hospitalists comprise at least 10% of the PHM workforce5 and play an important role in caring for adult survivors of childhood diseases.3

Limited existing data suggest that the future practice patterns of med-peds residents may be affected by PHM fellowship requirements. One previous survey study indicated that, although med-peds residents see value in additional training opportunities offered by fellowship, the majority are less likely to pursue PHM as a result of the new requirements.4 Prominent factors dissuading residents from pursuing PHM fellowship included forfeited earnings during fellowship, student loan obligations, family obligations, and the perception that training received during residency was sufficient. Although these data provide important insights into potential changes in practice patterns, they do not explore qualities of PHM fellowship that may make additional training more appealing to med-peds residents and promote retention of med-peds–trained providers in the PHM workforce.

Further, there is no existing literature exploring if and how PHM fellowship programs are equipped to support the needs of med-peds–trained fellows. Other subspecialties have supported med-peds trainees in combined fellowship training programs, including rheumatology, neurology, pediatric emergency medicine, allergy/immunology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and psychiatry.7,8 However, the extent to which PHM fellowships follow a similar model to accommodate the career goals of med-peds participants is unclear.

Given the large numbers of med-peds residents who go on to practice combined PHM and adult HM, it is crucial to understand the training needs of this group within the context of PHM fellowship and board certification. The primary objectives of this study were to understand (1) the perceived PHM fellowship needs of med-peds residents interested in HM, and (2) how the current PHM fellowship training environment can meet those needs. Understanding that additional training requirements to practice PHM may affect the career trajectory of residents interested in HM, secondary objectives included describing perceptions of med-peds residents on PHM specialty designation and whether designation affected their career plans.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study took place over a 3-month period from May to July 2019 and included two surveys of different populations to develop a comprehensive understanding of stakeholder perceptions of PHM fellowship. The first survey (resident survey) invited med-peds residents who were members of the National Med-Peds Residents’ Association (NMPRA)9 in 2019 and who were interested in HM. The second survey (fellowship director [FD] survey) included PHM FDs. The study was determined to be exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Study Population and Recruitment

Resident Survey

Two attempts were made to elicit participation via the NMPRA electronic mailing list. The NMPRA membership includes med-peds residents and chief residents from US med-peds residency programs. As of May 2019, 77 med-peds residency programs and their residents were members of NMPRA, which encompassed all med-peds programs in the United States and its territories. NMPRA maintains a listserv for all members, and all existing US/territory programs were members at the time of the survey. Med-peds interns, residents, and chief residents interested in HM were invited to participate in this study.

FD Survey

Forty-eight FDs, representing member institutions of the PHM Fellowship Directors’ Council, were surveyed via the PHM Fellowship Directors listserv.

Survey Instruments

We constructed two de novo surveys consisting of multiple-choice and short-answer questions (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). To enhance the validity of survey responses, questions were designed and tested using an iterative consensus process among authors and additional participants, including current med-peds PHM fellows, PHM fellowship program directors, med-peds residency program directors, and current med-peds residents. These revisions were repeated for a total of four cycles. Items were created to increase knowledge on the following key areas: resident-perceived needs in fellowship training, impact of PHM subspecialty designation on career choices related to HM, health system structure of fellowship programs, and ability to accommodate med-peds clinical training within a PHM fellowship. A combined med-peds fellowship, as defined in the survey and referenced in this study, is a “combined internal medicine–pediatrics hospital medicine fellowship whereby you would remain eligible for PHM board certification.” To ensure a broad and inclusive view of potential needs of med-peds trainees considering fellowship, all respondents were asked to complete questions pertaining to anticipated fellowship needs regardless of their indicated interest in fellowship.

Data Collection

Survey completion was voluntary. Email identifiers were not linked to completed surveys. Study data were collected and managed by using Qualtrics XM. Only completed survey entries were included in analysis.

Statistical Methods and Data Analysis

R software version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for statistical analysis. Demographic data were summarized using frequency distributions. The intent of the free-text questions for both surveys was qualitative explanatory thematic analysis. Authors EB, HL, and AJ used a deductive approach to identify common themes that elucidated med-peds resident–anticipated needs in fellowship and PHM program strategies and barriers to accommodate these needs. Preliminary themes and action items were reviewed and discussed among the full authorship team until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

Resident Survey

A total of 466 med-peds residents completed the resident survey. There are approximately 1300 med-peds residents annually, creating an estimated response rate of 35.8% of all US med-peds residents. The majority (n = 380, 81.5%) of respondents were med-peds postgraduate years 1 through 3 and thus only eligible for PHM board certification via the PHM fellowship pathway (Table 1). Most (n = 446, 95.7%) respondents had considered a career in adult, pediatric, or combined HM at some point. Of those med-peds residents who considered a career in HM (Appendix Table 1), 92.8% (n = 414) would prefer to practice combined adult HM and PHM.

FD Survey

Twenty-eight FDs completed the FD survey, representing 58.3% of 2019 PHM fellowship programs. Of the responding programs, 23 (82.1%) were associated with a freestanding children’s hospital, and 24 (85.7%) were integrated or affiliated with a health system that provides adult inpatient care (Table 2). Sixteen (57.1%) programs had a med-peds residency program at their institution.

Med-Peds Resident Perceptions of PHM Fellowship

In considering the importance of PHM board certification for physicians practicing PHM, 59.0% (n= 275) of respondents rated board certification as “not at all important” (Appendix Table 2). Most (n = 420, 90.1%) med-peds trainees responded that PHM subspecialty designation “decreased” or “significantly decreased” their desire to pursue a career that includes PHM. Of the respondents who reported no interest in hospital medicine, eight (40%) reported that PHM subspecialty status dissuaded them from a career in HM at least a moderate amount (Appendix Table 3). Roughly one third (n=158, 33.9%) of respondents reported that PHM subspecialty designation increased or significantly increased their desire to pursue a career that includes adult HM (Appenidx Table 2). Finally, although the majority (n = 275, 59%) of respondents said they had no interest in a HM fellowship, 114 (24.5%) indicated interest in a combined med-peds HM fellowship (Appendix Table 1). Short-answer questions revealed that commitment to additional training on top of a 4-year residency program was a possible deterring factor, particularly in light of student loan debt and family obligations. Respondents reported adequate clinical training during residency as another deterring factor.

Med-Peds Resident–Perceived Needs in PHM Fellowship

Regardless of interest in completing a PHM fellowship, all resident survey respondents were asked how their ideal PHM fellowship should be structured. Almost all (n = 456, 97.9%) respondents indicated that they would prefer to complete a combined med-peds HM fellowship (Table 3), and most preferred to complete a fellowship in 2 years. Only 10 (2.1%) respondents preferred to complete a PHM fellowship alone in 2 or 3 years. More than half (n=253, 54.3%) of respondents indicated that it would be ideal to obtain a master’s degree as part of fellowship.

Three quarters (n = 355, 75.8%) of med-peds residents reported that they would want 41% or more of clinical time in an ideal fellowship dedicated to adult HM. Importantly, most (n = 322, 69.1%) of the med-peds residents did not consider moonlighting alone in either PHM or adult HM to be enough to maintain training. In addition, many (n = 366, 78.5%) respondents felt that it was important or very important for scholarly work during fellowship to bridge pediatrics and internal medicine.

Short-answer questions indicated that the ability to practice both internal medicine and pediatrics during fellowship emerged as an important deciding factor, with emphasis on adequate opportunities to maintain internal medicine knowledge base (Figure). Similarly, access to med-peds mentorship was an important component of the decision. Compensation both during fellowship and potential future earnings was also a prominent consideration.

Capacity of PHM Programs to Support Med-Peds Fellows

Fifteen (53.6%) FDs reported that their programs were able to accommodate both PHM and adult HM clinical time during fellowship, 11 (39.3%) were unsure, and 2 (7.1%) were unable to accommodate both (Table 2).

The options for adult HM clinical time varied by institution and included precepted time on adult HM, full attending privileges on adult HM, and adult HM time through moonlighting only. Short-answer responses from FDs with experience training med-peds fellows cited using PHM elective time for adult HM and offering moonlighting in adult HM as ways to address career goals of med-peds trainees. Scholarship time for fellows was preserved by decreasing required time on pediatric intensive care unit and complex care services.

Accessibility of Med-Peds Mentorship

As noted above, med-peds residents identified mentorship as an important factor in consideration of PHM fellowship. A total of 23 (82.1%) FDs reported their programs had med-peds faculty members within their PHM team (Table 2). The majority (n = 21, 91.3%) of those med-peds faculty had both PHM and adult HM clinical time.

DISCUSSION

This study characterized the ideal PHM fellowship structure from the perspective of med-peds residents and described the current ability of PHM fellowships to support med-peds residents. The majority of residents stated that they had no interest in an HM fellowship. However, for med-peds residents who considered a career in HM, 88.8% preferred to complete a combined internal medicine and pediatrics HM fellowship with close to half of clinical time dedicated to adult HM. Just over half (53.6%) of programs reported that they could currently accommodate both PHM and adult clinical time during fellowship, and all but two programs reported that they could accommodate both PHM and HM time in the future.

PHM subspecialty designation with associated fellowship training requirements decreased desire to practice HM among med-peds residents who responded to our survey. This reflects findings from a recently published study that evaluated whether PHM fellowship requirements for board certification influenced pediatric and med-peds residents’ decision to pursue PHM in 2018.4 Additionally, Chandrasekar et al4 found that 87% of respondents indicated that sufficient residency training was an important factor in discouraging them from pursuing PHM fellowship. We noted similar findings in our open-ended survey responses, which indicate that med-peds respondents perceived that the intended purpose of PHM fellowship was to provide additional clinical training, and that served as a deterrent for fellowship. However, the survey by Chandrasekar et al4 assessed only four factors for understanding what was important in encouraging pursuit of a PHM fellowship: opportunity to gain new skills, potential increase in salary, opportunity for a master’s degree, and increased prestige. Our survey expands on med-peds residents’ needs, indicating that med-peds residents want a combined med-peds/HM fellowship that allows them to meet PHM board-eligibility requirements while also continuing to develop their adult HM clinical practice and other nonclinical training objectives in a way that combines both adult HM and PHM. Both surveys demonstrate the role that residency program directors and other resident mentors can have in counseling trainees on the nonclinical training objectives of PHM fellowship, including research, quality improvement, medical education, and leadership and clinical operations. Additional emphasis can be placed on opportunities for an individualized curriculum to address the specific career aims of each resident.

In this study, med-peds trainees viewed distribution of clinical time during fellowship as an important factor in pursuing PHM fellowship. The perceived importance of balancing clinical time is not surprising considering that most survey respondents interested in HM ultimately intend to practice both PHM and adult HM. This finding corresponds with current practice patterns of med-peds hospitalists, the majority of whom care for both children and adults.4,5 Moonlighting in adult medicine was not considered sufficient, suggesting desire for mentorship and training integration on the internal medicine side. Opportunities for trainees to maintain and expand their internal medicine knowledge base and clinical decision-making outside of moonlighting will be key to meeting the needs of med-peds residents in PHM fellowship.

Fortunately, more than half of responding programs reported that they could allow for adult HM practice during PHM fellowship. Twelve programs were unsure if they could accommodate adult HM clinical time, and only two programs reported they could not. We suspect that the ability to support this training with clinical time in both adult HM and PHM is more likely available at programs with established internal medicine relationships, often in the form of med-peds residency programs and med-peds faculty. Further, these established relationships may be more common at pediatric health systems that are integrated or affiliated with an adult health system. Most PHM fellowships surveyed indicated that their pediatric institution had an affiliation with an adult facility, and most had med-peds HM faculty.

Precedent for supporting med-peds fellows is somewhat limited given that only five of the responding PHM fellowship programs reported having fellows with med-peds residency training. However, discrepancies between the expressed needs of med-peds residents and the current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited PHM fellowship structure highlight opportunities to tailor fellowship training to support the career goals of med-peds residents. The current PHM fellowship structure consists of 26 educational units, with each unit representing 4 calendar weeks. A minimum of eight units are spent on each of the following: core clinical rotations, systems and scholarship, and individualized curriculum.10,11 The Society of Hospital Medicine has published core competencies for both PHM and adult HM, which highlight significant overlap in each field’s skill competency, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, legal issues and risk management, and handoffs and transitions of care.12,13 We contend that competencies addressed within PHM fellowship core clinical rotations may overlap with adult HM. Training in adult HM could be completed as part of the individualized curriculum with the ACGME, allowing adult HM practice to count toward this requirement. This would offer med-peds fellows the option to maintain their adult HM knowledge base without eliminating all elective time. Ultimately, it will be important to be creative in how training is accomplished and skills are acquired during both core clinical and individualized training blocks for med-peds trainees completing PHM fellowship.

In order to meet the expressed needs of med-peds residents interested in incorporating both adult HM and PHM into their future careers through PHM fellowship, we offer key recommendations for consideration by the ACGME, PHM FDs, and med-peds program directors (Figure). We encourage current PHM fellowship programs to establish relationships with adult HM programs to develop structured clinical opportunities that will allow fellows to gain the additional clinical training desired.

There were important limitations in this study. First, our estimated response rate for the resident survey was 35.8% of all med-peds residents in 2019, which may be interpreted as low. However, it is important to note that the survey was targeted to residents interested in HM. More than 25% of med-peds residents pursue a career in HM,5 suggesting our response rate may be attributed to residents who did not complete the survey because they were interested in other fields. The program director survey response rate was higher at 58.3%, though it is possible that response bias resulted in a higher response rate from programs with the ability to support med-peds trainees. Regardless, data from programs with the ability to support med-peds trainees are highly valuable in describing how PHM fellowship can be inclusive of med-peds–trained physicians interested in pursuing HM.

Both surveys were completed in 2019, prior to the ACGME accreditation of PHM fellowship, which likely presents new, unique challenges to fellowship programs trying to support the needs of med-peds fellows. However, insights noted above from programs with experience training med-peds fellows are still applicable within the constraints of ACGME requirements.

CONCLUSION

Many med-peds residents express strong interest in practicing HM and including PHM as part of their future hospitalist practice. With the introduction of PHM subspecialty board certification through the American Board of Pediatrics, med-peds residents face new considerations when choosing a career path after residency. The majority of resident respondents express the desire to spend a substantial portion of their clinical practice and/or fellowship practicing adult HM. A majority of PHM fellowships can or are willing to explore how to provide both pediatric and adult hospitalist training to med-peds residency–trained fellows. Understanding the facilitators and barriers to recruiting med-peds trainees for PHM fellowship ultimately has significant implications for the future of the PHM workforce. Incorporating the recommendations noted in this study may increase retention of med-peds providers in PHM by enabling fellowship training and ultimately board certification. Collaboration among the ACGME, PHM program directors, and med-peds residency program directors could help to develop PHM fellowship training programs that will meet the needs of med-peds residents interested in practicing PHM while still meeting ACGME requirements for PHM board eligibility.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Anoop Agrawal of National Med-Peds Residents’ Association (NMPRA).

The American Board of Medical Specialties approved subspecialty designation for the field of pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) in 2016.1 For those who started independent practice prior to July 2019, there were two options for board eligibility: the “practice pathway” or completion of a PHM fellowship. The practice pathway allows for pediatric and combined internal medicine–pediatric (med-peds) providers who graduated by July 2019 to sit for the PHM board-certification examination if they meet specific criteria in their pediatric practice.2 For pediatric and med-peds residents who graduated after July 2019, PHM board eligibility is available only through completion of a PHM fellowship.

PHM subspecialty designation with fellowship training requirements may pose unique challenges to med-peds residents interested in practicing both pediatric and adult hospital medicine (HM).3,4 Each year, an estimated 25% of med-peds residency graduates go on to practice HM.5 The majority (62%-83%) of currently practicing med-peds–trained hospitalists care for both adults and children.5,6 Further, med-peds–trained hospitalists comprise at least 10% of the PHM workforce5 and play an important role in caring for adult survivors of childhood diseases.3

Limited existing data suggest that the future practice patterns of med-peds residents may be affected by PHM fellowship requirements. One previous survey study indicated that, although med-peds residents see value in additional training opportunities offered by fellowship, the majority are less likely to pursue PHM as a result of the new requirements.4 Prominent factors dissuading residents from pursuing PHM fellowship included forfeited earnings during fellowship, student loan obligations, family obligations, and the perception that training received during residency was sufficient. Although these data provide important insights into potential changes in practice patterns, they do not explore qualities of PHM fellowship that may make additional training more appealing to med-peds residents and promote retention of med-peds–trained providers in the PHM workforce.

Further, there is no existing literature exploring if and how PHM fellowship programs are equipped to support the needs of med-peds–trained fellows. Other subspecialties have supported med-peds trainees in combined fellowship training programs, including rheumatology, neurology, pediatric emergency medicine, allergy/immunology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and psychiatry.7,8 However, the extent to which PHM fellowships follow a similar model to accommodate the career goals of med-peds participants is unclear.

Given the large numbers of med-peds residents who go on to practice combined PHM and adult HM, it is crucial to understand the training needs of this group within the context of PHM fellowship and board certification. The primary objectives of this study were to understand (1) the perceived PHM fellowship needs of med-peds residents interested in HM, and (2) how the current PHM fellowship training environment can meet those needs. Understanding that additional training requirements to practice PHM may affect the career trajectory of residents interested in HM, secondary objectives included describing perceptions of med-peds residents on PHM specialty designation and whether designation affected their career plans.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study took place over a 3-month period from May to July 2019 and included two surveys of different populations to develop a comprehensive understanding of stakeholder perceptions of PHM fellowship. The first survey (resident survey) invited med-peds residents who were members of the National Med-Peds Residents’ Association (NMPRA)9 in 2019 and who were interested in HM. The second survey (fellowship director [FD] survey) included PHM FDs. The study was determined to be exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Study Population and Recruitment

Resident Survey

Two attempts were made to elicit participation via the NMPRA electronic mailing list. The NMPRA membership includes med-peds residents and chief residents from US med-peds residency programs. As of May 2019, 77 med-peds residency programs and their residents were members of NMPRA, which encompassed all med-peds programs in the United States and its territories. NMPRA maintains a listserv for all members, and all existing US/territory programs were members at the time of the survey. Med-peds interns, residents, and chief residents interested in HM were invited to participate in this study.

FD Survey

Forty-eight FDs, representing member institutions of the PHM Fellowship Directors’ Council, were surveyed via the PHM Fellowship Directors listserv.

Survey Instruments

We constructed two de novo surveys consisting of multiple-choice and short-answer questions (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). To enhance the validity of survey responses, questions were designed and tested using an iterative consensus process among authors and additional participants, including current med-peds PHM fellows, PHM fellowship program directors, med-peds residency program directors, and current med-peds residents. These revisions were repeated for a total of four cycles. Items were created to increase knowledge on the following key areas: resident-perceived needs in fellowship training, impact of PHM subspecialty designation on career choices related to HM, health system structure of fellowship programs, and ability to accommodate med-peds clinical training within a PHM fellowship. A combined med-peds fellowship, as defined in the survey and referenced in this study, is a “combined internal medicine–pediatrics hospital medicine fellowship whereby you would remain eligible for PHM board certification.” To ensure a broad and inclusive view of potential needs of med-peds trainees considering fellowship, all respondents were asked to complete questions pertaining to anticipated fellowship needs regardless of their indicated interest in fellowship.

Data Collection

Survey completion was voluntary. Email identifiers were not linked to completed surveys. Study data were collected and managed by using Qualtrics XM. Only completed survey entries were included in analysis.

Statistical Methods and Data Analysis

R software version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for statistical analysis. Demographic data were summarized using frequency distributions. The intent of the free-text questions for both surveys was qualitative explanatory thematic analysis. Authors EB, HL, and AJ used a deductive approach to identify common themes that elucidated med-peds resident–anticipated needs in fellowship and PHM program strategies and barriers to accommodate these needs. Preliminary themes and action items were reviewed and discussed among the full authorship team until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Demographic Data

Resident Survey

A total of 466 med-peds residents completed the resident survey. There are approximately 1300 med-peds residents annually, creating an estimated response rate of 35.8% of all US med-peds residents. The majority (n = 380, 81.5%) of respondents were med-peds postgraduate years 1 through 3 and thus only eligible for PHM board certification via the PHM fellowship pathway (Table 1). Most (n = 446, 95.7%) respondents had considered a career in adult, pediatric, or combined HM at some point. Of those med-peds residents who considered a career in HM (Appendix Table 1), 92.8% (n = 414) would prefer to practice combined adult HM and PHM.

FD Survey

Twenty-eight FDs completed the FD survey, representing 58.3% of 2019 PHM fellowship programs. Of the responding programs, 23 (82.1%) were associated with a freestanding children’s hospital, and 24 (85.7%) were integrated or affiliated with a health system that provides adult inpatient care (Table 2). Sixteen (57.1%) programs had a med-peds residency program at their institution.

Med-Peds Resident Perceptions of PHM Fellowship

In considering the importance of PHM board certification for physicians practicing PHM, 59.0% (n= 275) of respondents rated board certification as “not at all important” (Appendix Table 2). Most (n = 420, 90.1%) med-peds trainees responded that PHM subspecialty designation “decreased” or “significantly decreased” their desire to pursue a career that includes PHM. Of the respondents who reported no interest in hospital medicine, eight (40%) reported that PHM subspecialty status dissuaded them from a career in HM at least a moderate amount (Appendix Table 3). Roughly one third (n=158, 33.9%) of respondents reported that PHM subspecialty designation increased or significantly increased their desire to pursue a career that includes adult HM (Appenidx Table 2). Finally, although the majority (n = 275, 59%) of respondents said they had no interest in a HM fellowship, 114 (24.5%) indicated interest in a combined med-peds HM fellowship (Appendix Table 1). Short-answer questions revealed that commitment to additional training on top of a 4-year residency program was a possible deterring factor, particularly in light of student loan debt and family obligations. Respondents reported adequate clinical training during residency as another deterring factor.

Med-Peds Resident–Perceived Needs in PHM Fellowship

Regardless of interest in completing a PHM fellowship, all resident survey respondents were asked how their ideal PHM fellowship should be structured. Almost all (n = 456, 97.9%) respondents indicated that they would prefer to complete a combined med-peds HM fellowship (Table 3), and most preferred to complete a fellowship in 2 years. Only 10 (2.1%) respondents preferred to complete a PHM fellowship alone in 2 or 3 years. More than half (n=253, 54.3%) of respondents indicated that it would be ideal to obtain a master’s degree as part of fellowship.

Three quarters (n = 355, 75.8%) of med-peds residents reported that they would want 41% or more of clinical time in an ideal fellowship dedicated to adult HM. Importantly, most (n = 322, 69.1%) of the med-peds residents did not consider moonlighting alone in either PHM or adult HM to be enough to maintain training. In addition, many (n = 366, 78.5%) respondents felt that it was important or very important for scholarly work during fellowship to bridge pediatrics and internal medicine.

Short-answer questions indicated that the ability to practice both internal medicine and pediatrics during fellowship emerged as an important deciding factor, with emphasis on adequate opportunities to maintain internal medicine knowledge base (Figure). Similarly, access to med-peds mentorship was an important component of the decision. Compensation both during fellowship and potential future earnings was also a prominent consideration.

Capacity of PHM Programs to Support Med-Peds Fellows

Fifteen (53.6%) FDs reported that their programs were able to accommodate both PHM and adult HM clinical time during fellowship, 11 (39.3%) were unsure, and 2 (7.1%) were unable to accommodate both (Table 2).

The options for adult HM clinical time varied by institution and included precepted time on adult HM, full attending privileges on adult HM, and adult HM time through moonlighting only. Short-answer responses from FDs with experience training med-peds fellows cited using PHM elective time for adult HM and offering moonlighting in adult HM as ways to address career goals of med-peds trainees. Scholarship time for fellows was preserved by decreasing required time on pediatric intensive care unit and complex care services.

Accessibility of Med-Peds Mentorship

As noted above, med-peds residents identified mentorship as an important factor in consideration of PHM fellowship. A total of 23 (82.1%) FDs reported their programs had med-peds faculty members within their PHM team (Table 2). The majority (n = 21, 91.3%) of those med-peds faculty had both PHM and adult HM clinical time.

DISCUSSION

This study characterized the ideal PHM fellowship structure from the perspective of med-peds residents and described the current ability of PHM fellowships to support med-peds residents. The majority of residents stated that they had no interest in an HM fellowship. However, for med-peds residents who considered a career in HM, 88.8% preferred to complete a combined internal medicine and pediatrics HM fellowship with close to half of clinical time dedicated to adult HM. Just over half (53.6%) of programs reported that they could currently accommodate both PHM and adult clinical time during fellowship, and all but two programs reported that they could accommodate both PHM and HM time in the future.

PHM subspecialty designation with associated fellowship training requirements decreased desire to practice HM among med-peds residents who responded to our survey. This reflects findings from a recently published study that evaluated whether PHM fellowship requirements for board certification influenced pediatric and med-peds residents’ decision to pursue PHM in 2018.4 Additionally, Chandrasekar et al4 found that 87% of respondents indicated that sufficient residency training was an important factor in discouraging them from pursuing PHM fellowship. We noted similar findings in our open-ended survey responses, which indicate that med-peds respondents perceived that the intended purpose of PHM fellowship was to provide additional clinical training, and that served as a deterrent for fellowship. However, the survey by Chandrasekar et al4 assessed only four factors for understanding what was important in encouraging pursuit of a PHM fellowship: opportunity to gain new skills, potential increase in salary, opportunity for a master’s degree, and increased prestige. Our survey expands on med-peds residents’ needs, indicating that med-peds residents want a combined med-peds/HM fellowship that allows them to meet PHM board-eligibility requirements while also continuing to develop their adult HM clinical practice and other nonclinical training objectives in a way that combines both adult HM and PHM. Both surveys demonstrate the role that residency program directors and other resident mentors can have in counseling trainees on the nonclinical training objectives of PHM fellowship, including research, quality improvement, medical education, and leadership and clinical operations. Additional emphasis can be placed on opportunities for an individualized curriculum to address the specific career aims of each resident.

In this study, med-peds trainees viewed distribution of clinical time during fellowship as an important factor in pursuing PHM fellowship. The perceived importance of balancing clinical time is not surprising considering that most survey respondents interested in HM ultimately intend to practice both PHM and adult HM. This finding corresponds with current practice patterns of med-peds hospitalists, the majority of whom care for both children and adults.4,5 Moonlighting in adult medicine was not considered sufficient, suggesting desire for mentorship and training integration on the internal medicine side. Opportunities for trainees to maintain and expand their internal medicine knowledge base and clinical decision-making outside of moonlighting will be key to meeting the needs of med-peds residents in PHM fellowship.

Fortunately, more than half of responding programs reported that they could allow for adult HM practice during PHM fellowship. Twelve programs were unsure if they could accommodate adult HM clinical time, and only two programs reported they could not. We suspect that the ability to support this training with clinical time in both adult HM and PHM is more likely available at programs with established internal medicine relationships, often in the form of med-peds residency programs and med-peds faculty. Further, these established relationships may be more common at pediatric health systems that are integrated or affiliated with an adult health system. Most PHM fellowships surveyed indicated that their pediatric institution had an affiliation with an adult facility, and most had med-peds HM faculty.

Precedent for supporting med-peds fellows is somewhat limited given that only five of the responding PHM fellowship programs reported having fellows with med-peds residency training. However, discrepancies between the expressed needs of med-peds residents and the current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited PHM fellowship structure highlight opportunities to tailor fellowship training to support the career goals of med-peds residents. The current PHM fellowship structure consists of 26 educational units, with each unit representing 4 calendar weeks. A minimum of eight units are spent on each of the following: core clinical rotations, systems and scholarship, and individualized curriculum.10,11 The Society of Hospital Medicine has published core competencies for both PHM and adult HM, which highlight significant overlap in each field’s skill competency, particularly in areas such as quality improvement, legal issues and risk management, and handoffs and transitions of care.12,13 We contend that competencies addressed within PHM fellowship core clinical rotations may overlap with adult HM. Training in adult HM could be completed as part of the individualized curriculum with the ACGME, allowing adult HM practice to count toward this requirement. This would offer med-peds fellows the option to maintain their adult HM knowledge base without eliminating all elective time. Ultimately, it will be important to be creative in how training is accomplished and skills are acquired during both core clinical and individualized training blocks for med-peds trainees completing PHM fellowship.

In order to meet the expressed needs of med-peds residents interested in incorporating both adult HM and PHM into their future careers through PHM fellowship, we offer key recommendations for consideration by the ACGME, PHM FDs, and med-peds program directors (Figure). We encourage current PHM fellowship programs to establish relationships with adult HM programs to develop structured clinical opportunities that will allow fellows to gain the additional clinical training desired.

There were important limitations in this study. First, our estimated response rate for the resident survey was 35.8% of all med-peds residents in 2019, which may be interpreted as low. However, it is important to note that the survey was targeted to residents interested in HM. More than 25% of med-peds residents pursue a career in HM,5 suggesting our response rate may be attributed to residents who did not complete the survey because they were interested in other fields. The program director survey response rate was higher at 58.3%, though it is possible that response bias resulted in a higher response rate from programs with the ability to support med-peds trainees. Regardless, data from programs with the ability to support med-peds trainees are highly valuable in describing how PHM fellowship can be inclusive of med-peds–trained physicians interested in pursuing HM.

Both surveys were completed in 2019, prior to the ACGME accreditation of PHM fellowship, which likely presents new, unique challenges to fellowship programs trying to support the needs of med-peds fellows. However, insights noted above from programs with experience training med-peds fellows are still applicable within the constraints of ACGME requirements.

CONCLUSION

Many med-peds residents express strong interest in practicing HM and including PHM as part of their future hospitalist practice. With the introduction of PHM subspecialty board certification through the American Board of Pediatrics, med-peds residents face new considerations when choosing a career path after residency. The majority of resident respondents express the desire to spend a substantial portion of their clinical practice and/or fellowship practicing adult HM. A majority of PHM fellowships can or are willing to explore how to provide both pediatric and adult hospitalist training to med-peds residency–trained fellows. Understanding the facilitators and barriers to recruiting med-peds trainees for PHM fellowship ultimately has significant implications for the future of the PHM workforce. Incorporating the recommendations noted in this study may increase retention of med-peds providers in PHM by enabling fellowship training and ultimately board certification. Collaboration among the ACGME, PHM program directors, and med-peds residency program directors could help to develop PHM fellowship training programs that will meet the needs of med-peds residents interested in practicing PHM while still meeting ACGME requirements for PHM board eligibility.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Anoop Agrawal of National Med-Peds Residents’ Association (NMPRA).

1. Blankenburg B, Bode R, Carlson D, et al. National Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leaders Conference. Published April 4, 2013. https://medpeds.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PediatricHospitalMedicineCertificationMeeting_Update.pdf

2. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. Revised December 18, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification

3. Feldman LS, Monash B, Eniasivam A, Chang W. Why required pediatric hospital medicine fellowships are unnecessary. Hospitalist. 2016;10. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/121461/pediatrics/why-required-pediatric-hospital-medicine-fellowships-are

4. Chandrasekar H, White YN, Ribeiro C, Landrigan CP, Marcus CH. A changing landscape: exploring resident perspectives on pursuing pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(2):109-115. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0034

5. O’Toole JK, Friedland AR, Gonzaga AMR, et al. The practice patterns of recently graduated internal medicine-pediatric hospitalists. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(6):309-314. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0135

6. Donnelly MJ, Lubrano L, Radabaugh CL, Lukela MP, Friedland AR, Ruch-Ross HS. The med-peds hospitalist workforce: results from the American Academy of Pediatrics Workforce Survey. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):574-579. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0031

7. Patwardhan A, Henrickson M, Laskosz L, Duyenhong S, Spencer CH. Current pediatric rheumatology fellowship training in the United States: what fellows actually do. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-8

8. Howell E, Kravet S, Kisuule F, Wright SM. An innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):314-318. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.327

9. The National Med-Peds Residents’ Association. About. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://medpeds.org/about-nmpra/

10. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698

11. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Pediatr Hosp Med. Published online July 1, 2020:55.

12. Maniscalco J, Gage S, Teferi S, Fisher ES. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies: 2020 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389-394. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3391

13. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine--2017 Revision: Introduction and Methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):283-287. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2715

1. Blankenburg B, Bode R, Carlson D, et al. National Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leaders Conference. Published April 4, 2013. https://medpeds.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PediatricHospitalMedicineCertificationMeeting_Update.pdf

2. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. Revised December 18, 2020. Accessed January 26, 2021. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification

3. Feldman LS, Monash B, Eniasivam A, Chang W. Why required pediatric hospital medicine fellowships are unnecessary. Hospitalist. 2016;10. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/121461/pediatrics/why-required-pediatric-hospital-medicine-fellowships-are

4. Chandrasekar H, White YN, Ribeiro C, Landrigan CP, Marcus CH. A changing landscape: exploring resident perspectives on pursuing pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(2):109-115. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0034

5. O’Toole JK, Friedland AR, Gonzaga AMR, et al. The practice patterns of recently graduated internal medicine-pediatric hospitalists. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(6):309-314. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0135

6. Donnelly MJ, Lubrano L, Radabaugh CL, Lukela MP, Friedland AR, Ruch-Ross HS. The med-peds hospitalist workforce: results from the American Academy of Pediatrics Workforce Survey. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):574-579. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0031

7. Patwardhan A, Henrickson M, Laskosz L, Duyenhong S, Spencer CH. Current pediatric rheumatology fellowship training in the United States: what fellows actually do. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014;12(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-8

8. Howell E, Kravet S, Kisuule F, Wright SM. An innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(4):314-318. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.327

9. The National Med-Peds Residents’ Association. About. Accessed May 11, 2021. https://medpeds.org/about-nmpra/

10. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a curricular framework for pediatric hospital medicine fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170698.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0698

11. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Pediatr Hosp Med. Published online July 1, 2020:55.

12. Maniscalco J, Gage S, Teferi S, Fisher ES. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies: 2020 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389-394. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3391

13. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine--2017 Revision: Introduction and Methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):283-287. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2715

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Collateral Damage: How COVID-19 Is Adversely Impacting Women Physicians

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected every facet of our work and personal lives. While many hope we will return to “normal” with the pandemic’s passing, there is reason to believe medicine, and society, will experience irrevocable changes. Although the number of women pursuing and practicing medicine has increased, inequities remain in compensation, academic rank, and leadership positions.1,2 Within the workplace, women are more likely to be in frontline clinical positions, are more likely to be integral in promoting positive interpersonal relationships and collaborative work environments, and often are less represented in the high-level, decision-making roles in leadership or administration.3,4 These well-described issues may be exacerbated during this pandemic crisis. We describe how the current COVID-19 pandemic may intensify workplace inequities for women, and propose solutions for hospitalist groups, leaders, and administrators to ensure female hospitalists continue to prosper and thrive in these tenuous times.

HOW THE PANDEMIC MAY EXACERBATE EXISTING INEQUITIES

Increasing Demands at Home

Female physicians are more likely to have partners who are employed full-time and report spending more time on household activities including cleaning, cooking, and the care of children, compared with their male counterparts.5 With school and daycare closings, as well as stay-at-home orders in many US states, there has been an increase in household responsibilities and care needs for children remaining at home with a marked decrease in options for stable or emergency childcare.6 As compared with primary care and subspecialty colleagues who can provide a large percentage of their care through telemedicine, this is not the case for hospitalists who must be physically present to care for their patients. Therefore, hospitalists are unable to clinically “work from home” in the same way as many of their colleagues in other specialties. Increased childcare and schooling obligations, coupled with disproportionate household responsibilities and an inability to work from home, will likely result in female hospitalists struggling to meet family needs while pandemic-related work responsibilities are ramping up.7 In addition, women who are involved with administrative, leadership, or research activities may struggle to execute their responsibilities as a result of increased domestic duties.

Many hospitalists are also concerned about contracting COVID-19 and exposing their families to the illness given the high infection rate among healthcare workers and the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).8,9 Institutions and national organizations, including the Society of Hospital Medicine, have partnered with industry to provide discounted or complimentary hotel rooms for members to aid self-isolation while providing clinical care.10 One famous photo in popular and social media showed a pulmonary and critical care physician in a tent in his garage in order to self-isolate from his family.11 However, since women are often the primary caregivers for their children or other family members and may also be responsible for other important household activities, they may be unable or unwilling to remove themselves from their children and families. As a result, female hospitalists may encounter feelings of guilt or inadequacy if they’re unable to isolate in the same manner as male colleagues.8

Exaggerating Leadership Gap

One of the keys to a robust response to this pandemic is strong, thoughtful, and strategic leadership.12 Institutional, regional, and national leaders are at the forefront of designing the solutions to the many problems the COVID-19 pandemic has created. The paucity of women at high-level leadership positions in institutions across the United States, including university-based, community, public, and private institutions, means that there is a lack of female representation when institutional policy is being discussed and decided.4 This lack of representation may lead to policies and procedures that negatively affect female hospitalists or, at best, fail to consider the needs of or support female physicians. For example, leaders of a hospital medicine group may create mandatory “backup” coverage for night and weekend shifts for their group during surge periods of the pandemic without considering implications for childcare. Finding weekday, daytime coverage is challenging for many during this time when daycares and school are closed, and finding coverage during weekend or overnight hours will be even more challenging. With increased risks for older adults with high-risk medical conditions, grandparents or other friends or family members that previously would have assisted with childcare may no longer be an option. If a female hospitalist is not a member of the leadership group that helped design this coverage structure, there could be a lack of recognition of the undue strain this coverage model could create for women in the group. Even if not intentional, such policies may hinder women’s career stability and opportunities for further advancement, as well as their ability to adequately provide care for their families. Having women as a part of the leadership group that creates policies and schedules and makes pivotal decisions is imperative, especially regarding topics of providing access and compensation for “emergency childcare,” hazard pay, shift length, work conditions, job security, sick leave, workers compensation, advancement opportunities, and hiring practices.

Compensation

The gender pay gap in medicine has been consistently demonstrated among many specialties.13,14 The reasons for this inequity are multifactorial, and the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to further widen this gap. With the unequal burden of unpaid care provided by women and their higher prevalence as frontline workers, they are at greater risk of needing to take unpaid leave to care for a sick family member or themselves.6,7 Similarly, without hazard pay, those with direct clinical responsibilities bear the risk of illness for themselves and their families without adequate compensation.

Impact on Physical and Mental Health

The overall well-being of the hospitalist workforce is critical to continue to provide the highest level of care for our patients. With higher workloads at home and at work, female hospitalists are at risk for increased burnout. Burnout has been linked to many negative outcomes including poor performance, depression, suicide, and leaving the profession.15 Burnout is documented to be higher in female physicians with several contributing factors that are aggravated by gender inequities, including having children at home, gender bias, and real or perceived lack of fairness in promotion and compensation.16 The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the stress of having children in the home, as well as concerns around fair compensation as described above. The consequences of this have yet to be fully realized but may be dire.

PROPOSED RECOMMENDATIONS

We propose the following recommendations to help mitigate the effects of this epidemic and to continue to move our field forward on our path to equity.