User login

Supporting Primary Care Patient-Centered Medical Homes with Community Care Teams: Findings from a Pilot Study

From the Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA.

Abstract

- Objective: With the growing recognition that team-based care might help meet the country’s primary care needs, this study’s objective was to evaluate the preliminary effectiveness of multidisciplinary community care teams (CCTs) deployed to primary care practices transforming into patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs).

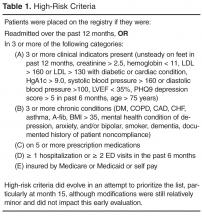

- Methods: A nonrandomized longitudinal study design was used contrasting the CCT practices/patients with non-CCT comparison groups. Outcomes included utilization (ED/hospital use), quality indicators (QIs), practice joy, and patient satisfaction. Two CCTs (consisting of nurse care manager, behavioral health specialist, social worker, and pharmacist) were deployed to 6 primary care practices and provided services to 406 patients. Practice level analyses compared patients from the 6 CCT practices not receiving team services (29,881 patients) to 3 non-CCT practices (22,350 patients) that were also transforming toward PCMH. The comparison group for the patient level analyses (patients who received CCT services) was patients from the same CCT practice who did not receive CCT services.

- Results: At the practice level, there were significant improvements in QIs for practices both with and without CCTs. However, reductions in the probability of an admission and readmission occurred only for high-risk patients in CCT practices. At the patient level, the probability of an unplanned admission was reduced for CCT and non-CCT patients, but the probability of a readmission was only reduced in CCT patients receiving hospital discharge reconciliation calls from CCT staff.

- Conclusion: Preliminary results suggest possible added benefit of CCTs over PCMHs alone for reducing hospitalization.

As health care organizations move from a fee-for-service model to a value-based model in an accountable care environment, the transformation of primary care to patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) is one of the fundamental strategies for achieving higher quality care at lower cost [1–3]. The core tenets of the PCMH are a commitment to high quality and safe care that is accessible, comprehensive, and coordinated across the health continuum, as well as patient-centered [4,5]. Newer to the PCMH model has been shifting the paradigm of care from individual encounters to using elements of population health management to proactively manage a panel of patients [1,3,6]. Given the array of patients seen in a primary care setting and the complexity of care required by many patients in a panel, particularly those with chronic conditions, a team approach to care capitalizes on multidisciplinary skills to collectively take responsibility for the ongoing care of the patients to improve health outcomes [7].

Multidisciplinary team-based care is considered a crucial strategy for meeting our society’s health care needs [8], especially in light of the expected shortage of primary care physicians coupled with the anticipated growth of the patient population due to the Affordable Care Act. Several different types of team-based care have been pursued. In 2003, for example, the State of Vermont pioneered health care reform through Vermont’s Blueprint for Health using principles of the PCMH that included team-based care [9]. The goal of the program was to deliver comprehensive and coordinated care to improve health outcomes for state residents. Vermont community health teams worked with primary care providers to manage short-term care for high-needs patients with an emphasis on better self-management, care coordination, chronic care management, and social and behavioral support services. An analysis of the first pilot program found significant decreases in hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) visits, and a per-person per-month reduction in costs [9].

The Lehigh Valley Health Network adapted the Vermont health improvement model to meet the unique needs of its practices that were transforming into PCMHs. When asked by leadership what would be most helpful in this transformational process, the practices cited additional staff resources to manage their high-risk patients. In response, the network enhanced support to the practices by implementing multidisciplinary teams called community care teams (CCTs), which were deployed to the practices to help manage their high-risk patients. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of CCTs within the PCMH model by examining key utilization, quality, and process measures. The CCTs were expected to increase the overall practice effectiveness and efficiency (practice level outcomes) by offsetting some of the workload regarding the management of high-risk patients and improving the outcomes of patients directly managed by the CCT (patient level outcomes).

Methods

Setting

Serving 5 counties, the Lehigh Valley Health Network is a large health care delivery system in southeastern PA that currently operates in a fee-for-service environment but is moving towards becoming an accountable care organization. The concept of using CCTs to support practices’ PCMH development originated with network leadership. Leadership approached 7 primary care practices with the most extensive PCMH involvement to pilot the CCT initiative (1 practice declined participation). More specifically, the practices were selected based upon their prior 3-year experience with practice transformation as a result of participating in the South Central PA Chronic Care Initiative [10] and having achieved National Committee for Quality Assurance level 3 PCMH recognition. Practice selection was also based on the results of a network-wide comprehensive practice assessment which included TransforMed’s MHIQ survey [11] of PCMH capabilities and in-house surveys to capture practice characteristics and readiness for change.

Program Design

The CCTs were designed to support 3 to 4 primary care practices in the short-term management of high-risk patients with chronic disease. Much like the Vermont community health team model, each team consisted of a RN care manager who functioned as the team lead, a behavioral health specialist, and a social worker. A clinical pharmacist was added to the CCT program shortly after implementing the project and was shared between 2 teams. The team engaged in population health management for patients identified as high-risk for poor outcomes by supporting the further development of disease self-management and goal setting skills, addressing behavioral health, social, and economic problems, and connecting the patient to other Network and community resources as needed. Furthermore, given the growing evidence demonstrating the positive impact of coordinated and continuity of care post hospital discharge on patient outcomes [12,13], the CCT also played a vital role in supporting the PCMH transition care program for high-risk patients, which involved contacting patients via the telephone within 48 business hours of discharge from the hospital to reconcile medications, assess and identify issues for follow-up, answer patient questions and coordinate appropriate appointments.

As a pilot program, 2 CCTs were deployed to 6 primary care practices (3 family medicine, 2 internal medicine, and 1 pediatric) in July 2012. Prior to engaging the practice and patients, each team member participated in an extensive orientation, which presented essential evidence-based knowledge on the CCT and PCMH models and provided application training and support in information systems, network resources, and care management.

Initially the CCT care managers forwarded the high-risk registry to each provider to review and identify the top patients for proactive care management outreach. CCT care managers then called the identified patients and/or coordinated outreach with patients through office appointments scheduled in the near future. At the same time as the registry outreach began, on-site clinician referrals to the CCT and hospital discharge reconciliation calls to patients by the CCT care manager commenced. Clinician referrals did not have to meet any formal criteria in order for that patient to receive CCT services. Ideally, the program was designed to service high-risk patients on the registry; however, the majority of patient contacts for care management emerged through day-to-day clinician referrals (not necessarily high-risk) and discharge reconciliation calls to high-risk patients for months 2 through 8 of the pilot phase. Patients' care was managed with continued, ongoing services until either patient goals were met or the patient was transferred to another practice or nursing home, expired, or declined further care management assistance. The CCT behavioral health specialist addressed short-term issues or bridged the gap or need until long-term services could be coordinated, sometimes requiring 6 to 8 meetings with a patient. CCT social worker services were assigned on a case-by-case basis and occasionally provided longer-term or intermittent need management, such as medication assistance.

Study Design and Sample

A naturalistic longitudinal study design was used to evaluate the CCT’s preliminary effectiveness. The CCTs were evaluated at 2 levels. First, based on the assumption that the CCT would off-set some of the practice workload and allow the practices to proactively manage more of their patient population, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the practice level, ie, patients who did not receive CCT services but belonged to practices with CCTs. Second, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the patient level, ie, patients receiving CCT services. At both levels, the CCT groups were contrasted with “non-CCT” comparison groups of convenience.

Measures

Primary outcome measures were utilization: ED visits, all-cause unplanned admissions, and 30-day readmissions. Secondary outcome measures included 2 types of quality indicators(QIs, see Appendix for scoring): (a) gaps in care measures that captured whether providers were following standards of care for diabetes, ischemic vascular disease, and prevention; and (b) patient composites which reflected patient illness severity for diabetes and cardiac disease. Higher scores indicated more gaps in care or greater disease severity. Both types of QI measures required at least a 12-month window and thus could not be computed for patients engaged with the CCT who had only a 6-month follow-up period (as their scores could reflect their pre-CCT status). In addition, comprehensive care was denoted by the provision of depression screening on the PHQ-2 [14], and whether HgA1c was greater or equal to 9.0 in diabetics served as an additional patient outcome measure. Other secondary outcome measures included practice joy via the Well-Being in the Workplace Questionnaire (WWQ) [15] and patient satisfaction from CAHPS-CG 12-month survey with PCMH items [16].

Data Collection

Utilization and quality data were extracted from the network’s hospital and outpatient electronic medical records (EMR). Practice staff were emailed every 6 months and asked to anonymously complete the WWQ via Survey Monkey [17]. At baseline, patient satisfaction surveys were distributed in the practice, and patients had the option of anonymously completing them during their visit or returning them in a prepaid envelop. While not recommended for CAHPS, this procedure had been internally used with success previously. At 12 months, the same survey was mailed to a random sample of patients with a prepaid return envelope.

At the practice level, utilization and QI data were only available for patients from 4 of the 6 practices: data were not available for 1 non-EMR practice and there was negligible variation in utilization from the pediatric practice. For the patient level analyses, utilization was available for patients in all 6 practices.

Statistical Analyses

To test whether outcomes were improved relative to a comparison group following the introduction of CCTs into the practices (practice level analyses) or CCT engagement (patient level analyses), mixed models analyses of variance with repeated measures on Time (pre- vs. post-CCT) were conducted with SAS [18] PROC MIXED and PROC GENMOD for continuous and dichotomous outcomes, respectively. To determine whether there was greater improvement in the CCT groups, all models included the interaction between Time and Group (CCT versus no CCT) in addition to their main effects. At the practice level, high-risk and non-high-risk patients were analyzed separately. And, at the patient level, CCT-MNGT and CCT-DCREC patients were analyzed separately with results adjusted for patient’s age. Some variables were not normally distributed. The quality variables were able to be normalized with natural log transformations, but utilization variables had to be dichotomized into “any” versus “none” due to severe skewness, inflated 0s and larger-valued counts. Practice joy and patient satisfaction can only be reported at the practice level (responses were aggregated within each practice because anonymous responses do not permit linking specific respondents over time and different patients were sampled across measurement occasions) and non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon signed ranked tests and tests of dependent proportions) were used to test for change over time given the small sample size (n = 6).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Practice samples had slightly more women than men (55.2%), were largely white (95.0%) and 50 years of age on average (mean = 49.53, SD = 20.18). The prevalence of diabetes (10.2%) and cardiac disease (10.4%) was relatively low. The percentage of women (56.3%) and whites (96.4%) for the patient level analytic samples was similar to the practice samples, whereas the prevalence of diabetes (33.6% ) and cardiac disease (44.6%) was notable higher and patients were more than 10 years older on average (mean = 61.62, SD = 23.96).

Practice Level Outcomes

Given these group baseline differences and only one instance where the Time by Group interaction was significant where group baseline differences were absent (see below), simple pre-post analyses were conducted for each group separately (Table 4). The results for non-high-risk patients indicated that, in both CCT and non-CCT practices, there was no improvement in utilization, but there were significant reductions in gaps in diabetic and preventative care and cardiac illness severity and significant increases in depression screening, although effect sizes for the latter 2 outcomes were small to negligible.

Practice joy fell in the medium range [19] at all time-points, with no notable change over time (see Appendix in the online version of this article). There was also no change in patient satisfaction (see Appendix, online), although after 12 months the “always” response for following up on lab tests was no longer higher than the national comparison and helpfulness of staff rated “never/sometimes” was below the national comparison.

Patient Level Outcomes

Discussion

The empirical literature indicates that PCMH practice transformation is a long, effortful process, the effects of which are not quick to manifest [20–22]. In this context, the results of the preliminary evaluation of the CCT pilot were encouraging: team-based care in the form of CCTs can be effectively used to support population health management. Overall, the results at the practice level suggest that PCMH transformation alone may be effective in creating improvements in patient care and cardiac disease (there were improvements in 3 out of 4 care gap measures and 1 disease measure for both CCT and non-CCT practices), but the presence of CCT appears necessary to reduce unplanned admissions and readmissions, at least among high-risk patients. Of course, this reduced utilization at the practice level could also be due to selection bias (practices with the longest PCMH involvement were selected for the CCT pilot) and it awaits to be seen if this finding holds as CCTs are deployed to more practices. Still, similar evidence for the CCT was found at the patient level. The probability of an unplanned admission was reduced for all groups of patients from CCT practices; however, this effect was notably large only for patients who received hospital discharge reconciliation calls from the CCT. Moreover, the only group that had a significant reduction in the probability of a 30-day readmission was also patients who received hospital discharge reconciliation calls from the CCT. Both results suggest an added benefit of CCT engagement. Although there was no change in the probability of an ED visit for any group, the CCT staff indicated that there was a substantial minority of CCT-engaged patients who were not accessing the ED when they should have been and it might be that increased appropriate use by this minority due to CCT coaching therefore cancelled out expected reductions in ED use among other CCT patients.

The intent of the current endeavor was to perform a formative evaluation [23,24] of the CCTs effectiveness. We recognized there would be analytic challenges and limits to such early-stage analyses. Nonetheless, we believed it was vital, especially given the cost of the CCTs and the growing financial pressure on health care networks more globally, to determine the preliminary effectiveness of the CCTs’, care management interventions and, if possible, suggest improvements to the intervention. As intended in formative evaluations, the evaluation is ongoing. Future analyses will bring more rigor to the evaluation and solve the data and analytic obstacles that affected the results of this first round of analyses.

A major learning of the early-stage analyses was the difficulty in developing comparison groups that are equivalent to the intervention groups at baseline. A number of matching schemes were attempted at the patient level in addition to the one presented here, but they were equally problematic. Avenues for creating more valid comparison groups in the future include the use of propensity score matching as well as drawing comparison groups from data from other networks. In addition, as time passes and more than 1 follow-up point is available for analysis, multilevel modeling can be employed which can specify different intercepts (baseline values) for groups. Still, it’s worth noting that constructing appropriate comparison groups is challenging even with those approaches: most health networks do not collect data on the most relevant matching variables (eg, health literacy, social economic status, social isolation/support) due to their cost and burden to both practices and patients.

Another major gap revealed by the early-stage analyses was the need to improve the strategy used for selecting patients for CCT intervention. In addition to many physician referrals, there was a large number of patients on the high-risk registry who required intervention relative to the small CCT staff. Various strategies to prioritize the list were attempted, including cost-related analyses. As plagued the formation of comparisons groups, it seemed the variables most critical to risk stratification were unavailable in administrative datasets. Appreciating that data collection is costly and patients and busy practices already have survey fatigue, the evaluation team examined the empirical literature for a single useful tool for ranking patients as well as constructing better matched comparison groups. This search indicated that a measure of patient activation [25–27] would be particularly helpful not only for selecting the riskiest and costliest patients for CCT intervention but also for tailoring CCT services to different types of patients. Since the implementation of the CCTs the network has also contracted with a predictive analytics company to provide risk scores for the patients.

The current formative evaluation was an important learning journey, laying important ground work for better evaluating the CCTs’ effectiveness specifically and eventually becoming an accountable care provider more generally. If the network is to provide health care more effectively and efficiently, it will need to bring greater rigor to evaluations of its various interventions and other ACO endeavors. The current formative evaluation was a valuable demonstration to non-scientists of the weakness of single group pre-post designs and how more rigorous evaluations, which include comparison groups and address confounding variables, can enhance the validity of the analytic results. This learning journey also highlighted the limitations of administrative databases and the necessity of both primary data collection and mixed methods. For example, it seems that some practices may require educational interventions to take full advantage of the CCT and qualitative assessments on practice readiness seem a necessary addition to the quantitative practice assessment to identify the specific characteristics that need strengthening. In addition, the evaluation team also recently added a qualitative sub-study on high-risk patients’ experience with the CCT to overcome locally low CAHPS response rates and capture themes broader than patient satisfaction. Upcoming rounds of analyses will also tackle other aspects of formative evaluations including the study of the CCT implementation as more practices receive CCTs and determining if process and fidelity measures of the PCMH pillars are linked to better outcomes. Furthermore, future analytic plans include identifying the active ingredients and optimal doses of the CCT intervention as well as determine the most effective matches between different types of patients and different CCT interventions (eg, behavioral, care management, social, pharmacy). While we appreciate that barriers still remain and require solutions, we hope the current evaluation highlights the utility of performing such formative evaluations.

Corresponding author: Carol Foltz, PhD, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA, [email protected].

Funding/support: The evaluation was funded internally by Lehigh Valley Health Network and a close affiliate, the Lehigh Valley Physician Hospital Organization. The funding organizations had no role in any part of the study.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care—two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2301–3.

2. American Academy of Family Physicians. Primary care for the 21st century: Ensuring a quality, physician-led team for every patient. September 2012. Accessed at www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/about_us/initiatives/AAFP-PCMHWhitePaper.pdf.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The patient-centered medical home: Strategies to put patients at the center of primary care, February 2011. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Strategies%20to%20Put%20Patients%20at%20the%20Center%20of%20Primary%20Care.pdf.

4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

5. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Defining the medical home: A patient-centered philosophy that drives primary care excellence. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

6. Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. Transforming primary care: From past practice to the practice of the future. Health Aff 2010;29:779–84.

7. Robert Graham Center. The patient centered medical home: History, seven core features, evidence and transformational change, 2007. Accessed at www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2007/rgcmo-medical-home.Par.0001.File.tmp/rgcmo-medical-home.pdf.

8. Goldberg A. It matters how we define health care equity. Institute of Medicine. Accessed at www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2013/Commentaries/BPH-It-Matters-How-we-define-Health-Equity.pdf.

9. Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Aff 2011;30:383–6.

10. Bricker PL, Baron RJ, Scheirer JJ. Collaboration in Pennsylvania: rapidly spreading improved chronic care for patients to practices. J Cont Educ Health Prof 2010;30:114–25.

11.TransforMed. What does your medical home look like? A jumble of unconnected pieces or a coherent structure? Accessed at www.transformed.com/mhiq/welcome.cfm .

12. Health policy brief: care transitions. Health Aff 2012. Accessed at http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf.

13. Greenwald J, Denham C, Jack B. The hospital discharge: A review of a high-risk care transition with highlights of a reengineered discharge process. J Patient Saf 2007;3:97–106.

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams W. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–94.

15. Parker GB, Hyett MP. Measurement of well-being in the workplace: The development of the Work Well-Being Questionnaire. Nerv Ment Dis 2011;199:394-97.

16. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinician & group expanded 12-month survey with CAHPS patient-centered medical home (PCMH) items. Accessed at https://cahps.ahrq.gov/surveys-guidance/cg/pcmh/index.html.

17. SurveyMonkey. Accessed at http://www.surveymonkey.com (last visited 06-23-2014). SurveyMonkey: Palo Alto, CA.

18. SAS [computer program]. Version 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2002-2008.

19. Black Dog Institute. Accessed at www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/docs/workplacewellbeingquestionnairepaperversion.pdf.

20. Jaén CR, Ferrer, RL, Miller WL, Palmer RF. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home national demonstration project. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(Suppl 1):s57–s67.

21. Solberg LI, Asche SE, Fontaine P, Flottemesch TJ. Trends in quality during medical home transformation. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:515–21.

22. Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC. Summary of the national demonstration project and recommendations for the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(Suppl 1):s80–s90.

23. Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:S1–8.

24. Geonnotti K, Peikes D, Wang W, Smith J. Formative evaluation: fostering real-time adaptations and refinements to improve the effectiveness of patient-centered medical home models. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2013. AHRQ Publication No. 13-0025-EF.

25. Insignia Health. Accessed at www.insigniahealth.com/solutions/patient-activation-measure.

26. Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores’. Health Aff 2013;32:216–22.

27. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What The evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences fewer data on costs. Health Aff 2013;32:207–14.

From the Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA.

Abstract

- Objective: With the growing recognition that team-based care might help meet the country’s primary care needs, this study’s objective was to evaluate the preliminary effectiveness of multidisciplinary community care teams (CCTs) deployed to primary care practices transforming into patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs).

- Methods: A nonrandomized longitudinal study design was used contrasting the CCT practices/patients with non-CCT comparison groups. Outcomes included utilization (ED/hospital use), quality indicators (QIs), practice joy, and patient satisfaction. Two CCTs (consisting of nurse care manager, behavioral health specialist, social worker, and pharmacist) were deployed to 6 primary care practices and provided services to 406 patients. Practice level analyses compared patients from the 6 CCT practices not receiving team services (29,881 patients) to 3 non-CCT practices (22,350 patients) that were also transforming toward PCMH. The comparison group for the patient level analyses (patients who received CCT services) was patients from the same CCT practice who did not receive CCT services.

- Results: At the practice level, there were significant improvements in QIs for practices both with and without CCTs. However, reductions in the probability of an admission and readmission occurred only for high-risk patients in CCT practices. At the patient level, the probability of an unplanned admission was reduced for CCT and non-CCT patients, but the probability of a readmission was only reduced in CCT patients receiving hospital discharge reconciliation calls from CCT staff.

- Conclusion: Preliminary results suggest possible added benefit of CCTs over PCMHs alone for reducing hospitalization.

As health care organizations move from a fee-for-service model to a value-based model in an accountable care environment, the transformation of primary care to patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) is one of the fundamental strategies for achieving higher quality care at lower cost [1–3]. The core tenets of the PCMH are a commitment to high quality and safe care that is accessible, comprehensive, and coordinated across the health continuum, as well as patient-centered [4,5]. Newer to the PCMH model has been shifting the paradigm of care from individual encounters to using elements of population health management to proactively manage a panel of patients [1,3,6]. Given the array of patients seen in a primary care setting and the complexity of care required by many patients in a panel, particularly those with chronic conditions, a team approach to care capitalizes on multidisciplinary skills to collectively take responsibility for the ongoing care of the patients to improve health outcomes [7].

Multidisciplinary team-based care is considered a crucial strategy for meeting our society’s health care needs [8], especially in light of the expected shortage of primary care physicians coupled with the anticipated growth of the patient population due to the Affordable Care Act. Several different types of team-based care have been pursued. In 2003, for example, the State of Vermont pioneered health care reform through Vermont’s Blueprint for Health using principles of the PCMH that included team-based care [9]. The goal of the program was to deliver comprehensive and coordinated care to improve health outcomes for state residents. Vermont community health teams worked with primary care providers to manage short-term care for high-needs patients with an emphasis on better self-management, care coordination, chronic care management, and social and behavioral support services. An analysis of the first pilot program found significant decreases in hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) visits, and a per-person per-month reduction in costs [9].

The Lehigh Valley Health Network adapted the Vermont health improvement model to meet the unique needs of its practices that were transforming into PCMHs. When asked by leadership what would be most helpful in this transformational process, the practices cited additional staff resources to manage their high-risk patients. In response, the network enhanced support to the practices by implementing multidisciplinary teams called community care teams (CCTs), which were deployed to the practices to help manage their high-risk patients. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of CCTs within the PCMH model by examining key utilization, quality, and process measures. The CCTs were expected to increase the overall practice effectiveness and efficiency (practice level outcomes) by offsetting some of the workload regarding the management of high-risk patients and improving the outcomes of patients directly managed by the CCT (patient level outcomes).

Methods

Setting

Serving 5 counties, the Lehigh Valley Health Network is a large health care delivery system in southeastern PA that currently operates in a fee-for-service environment but is moving towards becoming an accountable care organization. The concept of using CCTs to support practices’ PCMH development originated with network leadership. Leadership approached 7 primary care practices with the most extensive PCMH involvement to pilot the CCT initiative (1 practice declined participation). More specifically, the practices were selected based upon their prior 3-year experience with practice transformation as a result of participating in the South Central PA Chronic Care Initiative [10] and having achieved National Committee for Quality Assurance level 3 PCMH recognition. Practice selection was also based on the results of a network-wide comprehensive practice assessment which included TransforMed’s MHIQ survey [11] of PCMH capabilities and in-house surveys to capture practice characteristics and readiness for change.

Program Design

The CCTs were designed to support 3 to 4 primary care practices in the short-term management of high-risk patients with chronic disease. Much like the Vermont community health team model, each team consisted of a RN care manager who functioned as the team lead, a behavioral health specialist, and a social worker. A clinical pharmacist was added to the CCT program shortly after implementing the project and was shared between 2 teams. The team engaged in population health management for patients identified as high-risk for poor outcomes by supporting the further development of disease self-management and goal setting skills, addressing behavioral health, social, and economic problems, and connecting the patient to other Network and community resources as needed. Furthermore, given the growing evidence demonstrating the positive impact of coordinated and continuity of care post hospital discharge on patient outcomes [12,13], the CCT also played a vital role in supporting the PCMH transition care program for high-risk patients, which involved contacting patients via the telephone within 48 business hours of discharge from the hospital to reconcile medications, assess and identify issues for follow-up, answer patient questions and coordinate appropriate appointments.

As a pilot program, 2 CCTs were deployed to 6 primary care practices (3 family medicine, 2 internal medicine, and 1 pediatric) in July 2012. Prior to engaging the practice and patients, each team member participated in an extensive orientation, which presented essential evidence-based knowledge on the CCT and PCMH models and provided application training and support in information systems, network resources, and care management.

Initially the CCT care managers forwarded the high-risk registry to each provider to review and identify the top patients for proactive care management outreach. CCT care managers then called the identified patients and/or coordinated outreach with patients through office appointments scheduled in the near future. At the same time as the registry outreach began, on-site clinician referrals to the CCT and hospital discharge reconciliation calls to patients by the CCT care manager commenced. Clinician referrals did not have to meet any formal criteria in order for that patient to receive CCT services. Ideally, the program was designed to service high-risk patients on the registry; however, the majority of patient contacts for care management emerged through day-to-day clinician referrals (not necessarily high-risk) and discharge reconciliation calls to high-risk patients for months 2 through 8 of the pilot phase. Patients' care was managed with continued, ongoing services until either patient goals were met or the patient was transferred to another practice or nursing home, expired, or declined further care management assistance. The CCT behavioral health specialist addressed short-term issues or bridged the gap or need until long-term services could be coordinated, sometimes requiring 6 to 8 meetings with a patient. CCT social worker services were assigned on a case-by-case basis and occasionally provided longer-term or intermittent need management, such as medication assistance.

Study Design and Sample

A naturalistic longitudinal study design was used to evaluate the CCT’s preliminary effectiveness. The CCTs were evaluated at 2 levels. First, based on the assumption that the CCT would off-set some of the practice workload and allow the practices to proactively manage more of their patient population, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the practice level, ie, patients who did not receive CCT services but belonged to practices with CCTs. Second, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the patient level, ie, patients receiving CCT services. At both levels, the CCT groups were contrasted with “non-CCT” comparison groups of convenience.

Measures

Primary outcome measures were utilization: ED visits, all-cause unplanned admissions, and 30-day readmissions. Secondary outcome measures included 2 types of quality indicators(QIs, see Appendix for scoring): (a) gaps in care measures that captured whether providers were following standards of care for diabetes, ischemic vascular disease, and prevention; and (b) patient composites which reflected patient illness severity for diabetes and cardiac disease. Higher scores indicated more gaps in care or greater disease severity. Both types of QI measures required at least a 12-month window and thus could not be computed for patients engaged with the CCT who had only a 6-month follow-up period (as their scores could reflect their pre-CCT status). In addition, comprehensive care was denoted by the provision of depression screening on the PHQ-2 [14], and whether HgA1c was greater or equal to 9.0 in diabetics served as an additional patient outcome measure. Other secondary outcome measures included practice joy via the Well-Being in the Workplace Questionnaire (WWQ) [15] and patient satisfaction from CAHPS-CG 12-month survey with PCMH items [16].

Data Collection

Utilization and quality data were extracted from the network’s hospital and outpatient electronic medical records (EMR). Practice staff were emailed every 6 months and asked to anonymously complete the WWQ via Survey Monkey [17]. At baseline, patient satisfaction surveys were distributed in the practice, and patients had the option of anonymously completing them during their visit or returning them in a prepaid envelop. While not recommended for CAHPS, this procedure had been internally used with success previously. At 12 months, the same survey was mailed to a random sample of patients with a prepaid return envelope.

At the practice level, utilization and QI data were only available for patients from 4 of the 6 practices: data were not available for 1 non-EMR practice and there was negligible variation in utilization from the pediatric practice. For the patient level analyses, utilization was available for patients in all 6 practices.

Statistical Analyses

To test whether outcomes were improved relative to a comparison group following the introduction of CCTs into the practices (practice level analyses) or CCT engagement (patient level analyses), mixed models analyses of variance with repeated measures on Time (pre- vs. post-CCT) were conducted with SAS [18] PROC MIXED and PROC GENMOD for continuous and dichotomous outcomes, respectively. To determine whether there was greater improvement in the CCT groups, all models included the interaction between Time and Group (CCT versus no CCT) in addition to their main effects. At the practice level, high-risk and non-high-risk patients were analyzed separately. And, at the patient level, CCT-MNGT and CCT-DCREC patients were analyzed separately with results adjusted for patient’s age. Some variables were not normally distributed. The quality variables were able to be normalized with natural log transformations, but utilization variables had to be dichotomized into “any” versus “none” due to severe skewness, inflated 0s and larger-valued counts. Practice joy and patient satisfaction can only be reported at the practice level (responses were aggregated within each practice because anonymous responses do not permit linking specific respondents over time and different patients were sampled across measurement occasions) and non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon signed ranked tests and tests of dependent proportions) were used to test for change over time given the small sample size (n = 6).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Practice samples had slightly more women than men (55.2%), were largely white (95.0%) and 50 years of age on average (mean = 49.53, SD = 20.18). The prevalence of diabetes (10.2%) and cardiac disease (10.4%) was relatively low. The percentage of women (56.3%) and whites (96.4%) for the patient level analytic samples was similar to the practice samples, whereas the prevalence of diabetes (33.6% ) and cardiac disease (44.6%) was notable higher and patients were more than 10 years older on average (mean = 61.62, SD = 23.96).

Practice Level Outcomes

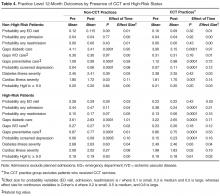

Given these group baseline differences and only one instance where the Time by Group interaction was significant where group baseline differences were absent (see below), simple pre-post analyses were conducted for each group separately (Table 4). The results for non-high-risk patients indicated that, in both CCT and non-CCT practices, there was no improvement in utilization, but there were significant reductions in gaps in diabetic and preventative care and cardiac illness severity and significant increases in depression screening, although effect sizes for the latter 2 outcomes were small to negligible.

Practice joy fell in the medium range [19] at all time-points, with no notable change over time (see Appendix in the online version of this article). There was also no change in patient satisfaction (see Appendix, online), although after 12 months the “always” response for following up on lab tests was no longer higher than the national comparison and helpfulness of staff rated “never/sometimes” was below the national comparison.

Patient Level Outcomes

Discussion

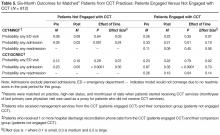

The empirical literature indicates that PCMH practice transformation is a long, effortful process, the effects of which are not quick to manifest [20–22]. In this context, the results of the preliminary evaluation of the CCT pilot were encouraging: team-based care in the form of CCTs can be effectively used to support population health management. Overall, the results at the practice level suggest that PCMH transformation alone may be effective in creating improvements in patient care and cardiac disease (there were improvements in 3 out of 4 care gap measures and 1 disease measure for both CCT and non-CCT practices), but the presence of CCT appears necessary to reduce unplanned admissions and readmissions, at least among high-risk patients. Of course, this reduced utilization at the practice level could also be due to selection bias (practices with the longest PCMH involvement were selected for the CCT pilot) and it awaits to be seen if this finding holds as CCTs are deployed to more practices. Still, similar evidence for the CCT was found at the patient level. The probability of an unplanned admission was reduced for all groups of patients from CCT practices; however, this effect was notably large only for patients who received hospital discharge reconciliation calls from the CCT. Moreover, the only group that had a significant reduction in the probability of a 30-day readmission was also patients who received hospital discharge reconciliation calls from the CCT. Both results suggest an added benefit of CCT engagement. Although there was no change in the probability of an ED visit for any group, the CCT staff indicated that there was a substantial minority of CCT-engaged patients who were not accessing the ED when they should have been and it might be that increased appropriate use by this minority due to CCT coaching therefore cancelled out expected reductions in ED use among other CCT patients.

The intent of the current endeavor was to perform a formative evaluation [23,24] of the CCTs effectiveness. We recognized there would be analytic challenges and limits to such early-stage analyses. Nonetheless, we believed it was vital, especially given the cost of the CCTs and the growing financial pressure on health care networks more globally, to determine the preliminary effectiveness of the CCTs’, care management interventions and, if possible, suggest improvements to the intervention. As intended in formative evaluations, the evaluation is ongoing. Future analyses will bring more rigor to the evaluation and solve the data and analytic obstacles that affected the results of this first round of analyses.

A major learning of the early-stage analyses was the difficulty in developing comparison groups that are equivalent to the intervention groups at baseline. A number of matching schemes were attempted at the patient level in addition to the one presented here, but they were equally problematic. Avenues for creating more valid comparison groups in the future include the use of propensity score matching as well as drawing comparison groups from data from other networks. In addition, as time passes and more than 1 follow-up point is available for analysis, multilevel modeling can be employed which can specify different intercepts (baseline values) for groups. Still, it’s worth noting that constructing appropriate comparison groups is challenging even with those approaches: most health networks do not collect data on the most relevant matching variables (eg, health literacy, social economic status, social isolation/support) due to their cost and burden to both practices and patients.

Another major gap revealed by the early-stage analyses was the need to improve the strategy used for selecting patients for CCT intervention. In addition to many physician referrals, there was a large number of patients on the high-risk registry who required intervention relative to the small CCT staff. Various strategies to prioritize the list were attempted, including cost-related analyses. As plagued the formation of comparisons groups, it seemed the variables most critical to risk stratification were unavailable in administrative datasets. Appreciating that data collection is costly and patients and busy practices already have survey fatigue, the evaluation team examined the empirical literature for a single useful tool for ranking patients as well as constructing better matched comparison groups. This search indicated that a measure of patient activation [25–27] would be particularly helpful not only for selecting the riskiest and costliest patients for CCT intervention but also for tailoring CCT services to different types of patients. Since the implementation of the CCTs the network has also contracted with a predictive analytics company to provide risk scores for the patients.

The current formative evaluation was an important learning journey, laying important ground work for better evaluating the CCTs’ effectiveness specifically and eventually becoming an accountable care provider more generally. If the network is to provide health care more effectively and efficiently, it will need to bring greater rigor to evaluations of its various interventions and other ACO endeavors. The current formative evaluation was a valuable demonstration to non-scientists of the weakness of single group pre-post designs and how more rigorous evaluations, which include comparison groups and address confounding variables, can enhance the validity of the analytic results. This learning journey also highlighted the limitations of administrative databases and the necessity of both primary data collection and mixed methods. For example, it seems that some practices may require educational interventions to take full advantage of the CCT and qualitative assessments on practice readiness seem a necessary addition to the quantitative practice assessment to identify the specific characteristics that need strengthening. In addition, the evaluation team also recently added a qualitative sub-study on high-risk patients’ experience with the CCT to overcome locally low CAHPS response rates and capture themes broader than patient satisfaction. Upcoming rounds of analyses will also tackle other aspects of formative evaluations including the study of the CCT implementation as more practices receive CCTs and determining if process and fidelity measures of the PCMH pillars are linked to better outcomes. Furthermore, future analytic plans include identifying the active ingredients and optimal doses of the CCT intervention as well as determine the most effective matches between different types of patients and different CCT interventions (eg, behavioral, care management, social, pharmacy). While we appreciate that barriers still remain and require solutions, we hope the current evaluation highlights the utility of performing such formative evaluations.

Corresponding author: Carol Foltz, PhD, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA, [email protected].

Funding/support: The evaluation was funded internally by Lehigh Valley Health Network and a close affiliate, the Lehigh Valley Physician Hospital Organization. The funding organizations had no role in any part of the study.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA.

Abstract

- Objective: With the growing recognition that team-based care might help meet the country’s primary care needs, this study’s objective was to evaluate the preliminary effectiveness of multidisciplinary community care teams (CCTs) deployed to primary care practices transforming into patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs).

- Methods: A nonrandomized longitudinal study design was used contrasting the CCT practices/patients with non-CCT comparison groups. Outcomes included utilization (ED/hospital use), quality indicators (QIs), practice joy, and patient satisfaction. Two CCTs (consisting of nurse care manager, behavioral health specialist, social worker, and pharmacist) were deployed to 6 primary care practices and provided services to 406 patients. Practice level analyses compared patients from the 6 CCT practices not receiving team services (29,881 patients) to 3 non-CCT practices (22,350 patients) that were also transforming toward PCMH. The comparison group for the patient level analyses (patients who received CCT services) was patients from the same CCT practice who did not receive CCT services.

- Results: At the practice level, there were significant improvements in QIs for practices both with and without CCTs. However, reductions in the probability of an admission and readmission occurred only for high-risk patients in CCT practices. At the patient level, the probability of an unplanned admission was reduced for CCT and non-CCT patients, but the probability of a readmission was only reduced in CCT patients receiving hospital discharge reconciliation calls from CCT staff.

- Conclusion: Preliminary results suggest possible added benefit of CCTs over PCMHs alone for reducing hospitalization.

As health care organizations move from a fee-for-service model to a value-based model in an accountable care environment, the transformation of primary care to patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) is one of the fundamental strategies for achieving higher quality care at lower cost [1–3]. The core tenets of the PCMH are a commitment to high quality and safe care that is accessible, comprehensive, and coordinated across the health continuum, as well as patient-centered [4,5]. Newer to the PCMH model has been shifting the paradigm of care from individual encounters to using elements of population health management to proactively manage a panel of patients [1,3,6]. Given the array of patients seen in a primary care setting and the complexity of care required by many patients in a panel, particularly those with chronic conditions, a team approach to care capitalizes on multidisciplinary skills to collectively take responsibility for the ongoing care of the patients to improve health outcomes [7].

Multidisciplinary team-based care is considered a crucial strategy for meeting our society’s health care needs [8], especially in light of the expected shortage of primary care physicians coupled with the anticipated growth of the patient population due to the Affordable Care Act. Several different types of team-based care have been pursued. In 2003, for example, the State of Vermont pioneered health care reform through Vermont’s Blueprint for Health using principles of the PCMH that included team-based care [9]. The goal of the program was to deliver comprehensive and coordinated care to improve health outcomes for state residents. Vermont community health teams worked with primary care providers to manage short-term care for high-needs patients with an emphasis on better self-management, care coordination, chronic care management, and social and behavioral support services. An analysis of the first pilot program found significant decreases in hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) visits, and a per-person per-month reduction in costs [9].

The Lehigh Valley Health Network adapted the Vermont health improvement model to meet the unique needs of its practices that were transforming into PCMHs. When asked by leadership what would be most helpful in this transformational process, the practices cited additional staff resources to manage their high-risk patients. In response, the network enhanced support to the practices by implementing multidisciplinary teams called community care teams (CCTs), which were deployed to the practices to help manage their high-risk patients. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of CCTs within the PCMH model by examining key utilization, quality, and process measures. The CCTs were expected to increase the overall practice effectiveness and efficiency (practice level outcomes) by offsetting some of the workload regarding the management of high-risk patients and improving the outcomes of patients directly managed by the CCT (patient level outcomes).

Methods

Setting

Serving 5 counties, the Lehigh Valley Health Network is a large health care delivery system in southeastern PA that currently operates in a fee-for-service environment but is moving towards becoming an accountable care organization. The concept of using CCTs to support practices’ PCMH development originated with network leadership. Leadership approached 7 primary care practices with the most extensive PCMH involvement to pilot the CCT initiative (1 practice declined participation). More specifically, the practices were selected based upon their prior 3-year experience with practice transformation as a result of participating in the South Central PA Chronic Care Initiative [10] and having achieved National Committee for Quality Assurance level 3 PCMH recognition. Practice selection was also based on the results of a network-wide comprehensive practice assessment which included TransforMed’s MHIQ survey [11] of PCMH capabilities and in-house surveys to capture practice characteristics and readiness for change.

Program Design

The CCTs were designed to support 3 to 4 primary care practices in the short-term management of high-risk patients with chronic disease. Much like the Vermont community health team model, each team consisted of a RN care manager who functioned as the team lead, a behavioral health specialist, and a social worker. A clinical pharmacist was added to the CCT program shortly after implementing the project and was shared between 2 teams. The team engaged in population health management for patients identified as high-risk for poor outcomes by supporting the further development of disease self-management and goal setting skills, addressing behavioral health, social, and economic problems, and connecting the patient to other Network and community resources as needed. Furthermore, given the growing evidence demonstrating the positive impact of coordinated and continuity of care post hospital discharge on patient outcomes [12,13], the CCT also played a vital role in supporting the PCMH transition care program for high-risk patients, which involved contacting patients via the telephone within 48 business hours of discharge from the hospital to reconcile medications, assess and identify issues for follow-up, answer patient questions and coordinate appropriate appointments.

As a pilot program, 2 CCTs were deployed to 6 primary care practices (3 family medicine, 2 internal medicine, and 1 pediatric) in July 2012. Prior to engaging the practice and patients, each team member participated in an extensive orientation, which presented essential evidence-based knowledge on the CCT and PCMH models and provided application training and support in information systems, network resources, and care management.

Initially the CCT care managers forwarded the high-risk registry to each provider to review and identify the top patients for proactive care management outreach. CCT care managers then called the identified patients and/or coordinated outreach with patients through office appointments scheduled in the near future. At the same time as the registry outreach began, on-site clinician referrals to the CCT and hospital discharge reconciliation calls to patients by the CCT care manager commenced. Clinician referrals did not have to meet any formal criteria in order for that patient to receive CCT services. Ideally, the program was designed to service high-risk patients on the registry; however, the majority of patient contacts for care management emerged through day-to-day clinician referrals (not necessarily high-risk) and discharge reconciliation calls to high-risk patients for months 2 through 8 of the pilot phase. Patients' care was managed with continued, ongoing services until either patient goals were met or the patient was transferred to another practice or nursing home, expired, or declined further care management assistance. The CCT behavioral health specialist addressed short-term issues or bridged the gap or need until long-term services could be coordinated, sometimes requiring 6 to 8 meetings with a patient. CCT social worker services were assigned on a case-by-case basis and occasionally provided longer-term or intermittent need management, such as medication assistance.

Study Design and Sample

A naturalistic longitudinal study design was used to evaluate the CCT’s preliminary effectiveness. The CCTs were evaluated at 2 levels. First, based on the assumption that the CCT would off-set some of the practice workload and allow the practices to proactively manage more of their patient population, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the practice level, ie, patients who did not receive CCT services but belonged to practices with CCTs. Second, the effectiveness of the CCTs was evaluated at the patient level, ie, patients receiving CCT services. At both levels, the CCT groups were contrasted with “non-CCT” comparison groups of convenience.

Measures

Primary outcome measures were utilization: ED visits, all-cause unplanned admissions, and 30-day readmissions. Secondary outcome measures included 2 types of quality indicators(QIs, see Appendix for scoring): (a) gaps in care measures that captured whether providers were following standards of care for diabetes, ischemic vascular disease, and prevention; and (b) patient composites which reflected patient illness severity for diabetes and cardiac disease. Higher scores indicated more gaps in care or greater disease severity. Both types of QI measures required at least a 12-month window and thus could not be computed for patients engaged with the CCT who had only a 6-month follow-up period (as their scores could reflect their pre-CCT status). In addition, comprehensive care was denoted by the provision of depression screening on the PHQ-2 [14], and whether HgA1c was greater or equal to 9.0 in diabetics served as an additional patient outcome measure. Other secondary outcome measures included practice joy via the Well-Being in the Workplace Questionnaire (WWQ) [15] and patient satisfaction from CAHPS-CG 12-month survey with PCMH items [16].

Data Collection

Utilization and quality data were extracted from the network’s hospital and outpatient electronic medical records (EMR). Practice staff were emailed every 6 months and asked to anonymously complete the WWQ via Survey Monkey [17]. At baseline, patient satisfaction surveys were distributed in the practice, and patients had the option of anonymously completing them during their visit or returning them in a prepaid envelop. While not recommended for CAHPS, this procedure had been internally used with success previously. At 12 months, the same survey was mailed to a random sample of patients with a prepaid return envelope.

At the practice level, utilization and QI data were only available for patients from 4 of the 6 practices: data were not available for 1 non-EMR practice and there was negligible variation in utilization from the pediatric practice. For the patient level analyses, utilization was available for patients in all 6 practices.

Statistical Analyses

To test whether outcomes were improved relative to a comparison group following the introduction of CCTs into the practices (practice level analyses) or CCT engagement (patient level analyses), mixed models analyses of variance with repeated measures on Time (pre- vs. post-CCT) were conducted with SAS [18] PROC MIXED and PROC GENMOD for continuous and dichotomous outcomes, respectively. To determine whether there was greater improvement in the CCT groups, all models included the interaction between Time and Group (CCT versus no CCT) in addition to their main effects. At the practice level, high-risk and non-high-risk patients were analyzed separately. And, at the patient level, CCT-MNGT and CCT-DCREC patients were analyzed separately with results adjusted for patient’s age. Some variables were not normally distributed. The quality variables were able to be normalized with natural log transformations, but utilization variables had to be dichotomized into “any” versus “none” due to severe skewness, inflated 0s and larger-valued counts. Practice joy and patient satisfaction can only be reported at the practice level (responses were aggregated within each practice because anonymous responses do not permit linking specific respondents over time and different patients were sampled across measurement occasions) and non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon signed ranked tests and tests of dependent proportions) were used to test for change over time given the small sample size (n = 6).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Practice samples had slightly more women than men (55.2%), were largely white (95.0%) and 50 years of age on average (mean = 49.53, SD = 20.18). The prevalence of diabetes (10.2%) and cardiac disease (10.4%) was relatively low. The percentage of women (56.3%) and whites (96.4%) for the patient level analytic samples was similar to the practice samples, whereas the prevalence of diabetes (33.6% ) and cardiac disease (44.6%) was notable higher and patients were more than 10 years older on average (mean = 61.62, SD = 23.96).

Practice Level Outcomes

Given these group baseline differences and only one instance where the Time by Group interaction was significant where group baseline differences were absent (see below), simple pre-post analyses were conducted for each group separately (Table 4). The results for non-high-risk patients indicated that, in both CCT and non-CCT practices, there was no improvement in utilization, but there were significant reductions in gaps in diabetic and preventative care and cardiac illness severity and significant increases in depression screening, although effect sizes for the latter 2 outcomes were small to negligible.

Practice joy fell in the medium range [19] at all time-points, with no notable change over time (see Appendix in the online version of this article). There was also no change in patient satisfaction (see Appendix, online), although after 12 months the “always” response for following up on lab tests was no longer higher than the national comparison and helpfulness of staff rated “never/sometimes” was below the national comparison.

Patient Level Outcomes

Discussion

The empirical literature indicates that PCMH practice transformation is a long, effortful process, the effects of which are not quick to manifest [20–22]. In this context, the results of the preliminary evaluation of the CCT pilot were encouraging: team-based care in the form of CCTs can be effectively used to support population health management. Overall, the results at the practice level suggest that PCMH transformation alone may be effective in creating improvements in patient care and cardiac disease (there were improvements in 3 out of 4 care gap measures and 1 disease measure for both CCT and non-CCT practices), but the presence of CCT appears necessary to reduce unplanned admissions and readmissions, at least among high-risk patients. Of course, this reduced utilization at the practice level could also be due to selection bias (practices with the longest PCMH involvement were selected for the CCT pilot) and it awaits to be seen if this finding holds as CCTs are deployed to more practices. Still, similar evidence for the CCT was found at the patient level. The probability of an unplanned admission was reduced for all groups of patients from CCT practices; however, this effect was notably large only for patients who received hospital discharge reconciliation calls from the CCT. Moreover, the only group that had a significant reduction in the probability of a 30-day readmission was also patients who received hospital discharge reconciliation calls from the CCT. Both results suggest an added benefit of CCT engagement. Although there was no change in the probability of an ED visit for any group, the CCT staff indicated that there was a substantial minority of CCT-engaged patients who were not accessing the ED when they should have been and it might be that increased appropriate use by this minority due to CCT coaching therefore cancelled out expected reductions in ED use among other CCT patients.

The intent of the current endeavor was to perform a formative evaluation [23,24] of the CCTs effectiveness. We recognized there would be analytic challenges and limits to such early-stage analyses. Nonetheless, we believed it was vital, especially given the cost of the CCTs and the growing financial pressure on health care networks more globally, to determine the preliminary effectiveness of the CCTs’, care management interventions and, if possible, suggest improvements to the intervention. As intended in formative evaluations, the evaluation is ongoing. Future analyses will bring more rigor to the evaluation and solve the data and analytic obstacles that affected the results of this first round of analyses.

A major learning of the early-stage analyses was the difficulty in developing comparison groups that are equivalent to the intervention groups at baseline. A number of matching schemes were attempted at the patient level in addition to the one presented here, but they were equally problematic. Avenues for creating more valid comparison groups in the future include the use of propensity score matching as well as drawing comparison groups from data from other networks. In addition, as time passes and more than 1 follow-up point is available for analysis, multilevel modeling can be employed which can specify different intercepts (baseline values) for groups. Still, it’s worth noting that constructing appropriate comparison groups is challenging even with those approaches: most health networks do not collect data on the most relevant matching variables (eg, health literacy, social economic status, social isolation/support) due to their cost and burden to both practices and patients.

Another major gap revealed by the early-stage analyses was the need to improve the strategy used for selecting patients for CCT intervention. In addition to many physician referrals, there was a large number of patients on the high-risk registry who required intervention relative to the small CCT staff. Various strategies to prioritize the list were attempted, including cost-related analyses. As plagued the formation of comparisons groups, it seemed the variables most critical to risk stratification were unavailable in administrative datasets. Appreciating that data collection is costly and patients and busy practices already have survey fatigue, the evaluation team examined the empirical literature for a single useful tool for ranking patients as well as constructing better matched comparison groups. This search indicated that a measure of patient activation [25–27] would be particularly helpful not only for selecting the riskiest and costliest patients for CCT intervention but also for tailoring CCT services to different types of patients. Since the implementation of the CCTs the network has also contracted with a predictive analytics company to provide risk scores for the patients.

The current formative evaluation was an important learning journey, laying important ground work for better evaluating the CCTs’ effectiveness specifically and eventually becoming an accountable care provider more generally. If the network is to provide health care more effectively and efficiently, it will need to bring greater rigor to evaluations of its various interventions and other ACO endeavors. The current formative evaluation was a valuable demonstration to non-scientists of the weakness of single group pre-post designs and how more rigorous evaluations, which include comparison groups and address confounding variables, can enhance the validity of the analytic results. This learning journey also highlighted the limitations of administrative databases and the necessity of both primary data collection and mixed methods. For example, it seems that some practices may require educational interventions to take full advantage of the CCT and qualitative assessments on practice readiness seem a necessary addition to the quantitative practice assessment to identify the specific characteristics that need strengthening. In addition, the evaluation team also recently added a qualitative sub-study on high-risk patients’ experience with the CCT to overcome locally low CAHPS response rates and capture themes broader than patient satisfaction. Upcoming rounds of analyses will also tackle other aspects of formative evaluations including the study of the CCT implementation as more practices receive CCTs and determining if process and fidelity measures of the PCMH pillars are linked to better outcomes. Furthermore, future analytic plans include identifying the active ingredients and optimal doses of the CCT intervention as well as determine the most effective matches between different types of patients and different CCT interventions (eg, behavioral, care management, social, pharmacy). While we appreciate that barriers still remain and require solutions, we hope the current evaluation highlights the utility of performing such formative evaluations.

Corresponding author: Carol Foltz, PhD, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA, [email protected].

Funding/support: The evaluation was funded internally by Lehigh Valley Health Network and a close affiliate, the Lehigh Valley Physician Hospital Organization. The funding organizations had no role in any part of the study.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care—two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2301–3.

2. American Academy of Family Physicians. Primary care for the 21st century: Ensuring a quality, physician-led team for every patient. September 2012. Accessed at www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/about_us/initiatives/AAFP-PCMHWhitePaper.pdf.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The patient-centered medical home: Strategies to put patients at the center of primary care, February 2011. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Strategies%20to%20Put%20Patients%20at%20the%20Center%20of%20Primary%20Care.pdf.

4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

5. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Defining the medical home: A patient-centered philosophy that drives primary care excellence. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

6. Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. Transforming primary care: From past practice to the practice of the future. Health Aff 2010;29:779–84.

7. Robert Graham Center. The patient centered medical home: History, seven core features, evidence and transformational change, 2007. Accessed at www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2007/rgcmo-medical-home.Par.0001.File.tmp/rgcmo-medical-home.pdf.

8. Goldberg A. It matters how we define health care equity. Institute of Medicine. Accessed at www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2013/Commentaries/BPH-It-Matters-How-we-define-Health-Equity.pdf.

9. Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Aff 2011;30:383–6.

10. Bricker PL, Baron RJ, Scheirer JJ. Collaboration in Pennsylvania: rapidly spreading improved chronic care for patients to practices. J Cont Educ Health Prof 2010;30:114–25.

11.TransforMed. What does your medical home look like? A jumble of unconnected pieces or a coherent structure? Accessed at www.transformed.com/mhiq/welcome.cfm .

12. Health policy brief: care transitions. Health Aff 2012. Accessed at http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_76.pdf.

13. Greenwald J, Denham C, Jack B. The hospital discharge: A review of a high-risk care transition with highlights of a reengineered discharge process. J Patient Saf 2007;3:97–106.

14. Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams W. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–94.

15. Parker GB, Hyett MP. Measurement of well-being in the workplace: The development of the Work Well-Being Questionnaire. Nerv Ment Dis 2011;199:394-97.

16. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinician & group expanded 12-month survey with CAHPS patient-centered medical home (PCMH) items. Accessed at https://cahps.ahrq.gov/surveys-guidance/cg/pcmh/index.html.

17. SurveyMonkey. Accessed at http://www.surveymonkey.com (last visited 06-23-2014). SurveyMonkey: Palo Alto, CA.

18. SAS [computer program]. Version 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2002-2008.

19. Black Dog Institute. Accessed at www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/docs/workplacewellbeingquestionnairepaperversion.pdf.

20. Jaén CR, Ferrer, RL, Miller WL, Palmer RF. Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home national demonstration project. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(Suppl 1):s57–s67.

21. Solberg LI, Asche SE, Fontaine P, Flottemesch TJ. Trends in quality during medical home transformation. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:515–21.

22. Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stange KC. Summary of the national demonstration project and recommendations for the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(Suppl 1):s80–s90.

23. Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:S1–8.

24. Geonnotti K, Peikes D, Wang W, Smith J. Formative evaluation: fostering real-time adaptations and refinements to improve the effectiveness of patient-centered medical home models. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2013. AHRQ Publication No. 13-0025-EF.

25. Insignia Health. Accessed at www.insigniahealth.com/solutions/patient-activation-measure.

26. Hibbard JH, Greene J, Overton V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs; delivery systems should know their patients’ ‘scores’. Health Aff 2013;32:216–22.

27. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What The evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences fewer data on costs. Health Aff 2013;32:207–14.

1. Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care—two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2301–3.

2. American Academy of Family Physicians. Primary care for the 21st century: Ensuring a quality, physician-led team for every patient. September 2012. Accessed at www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/about_us/initiatives/AAFP-PCMHWhitePaper.pdf.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The patient-centered medical home: Strategies to put patients at the center of primary care, February 2011. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Strategies%20to%20Put%20Patients%20at%20the%20Center%20of%20Primary%20Care.pdf.

4. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Defining the PCMH. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

5. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Defining the medical home: A patient-centered philosophy that drives primary care excellence. Accessed at http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh.

6. Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. Transforming primary care: From past practice to the practice of the future. Health Aff 2010;29:779–84.

7. Robert Graham Center. The patient centered medical home: History, seven core features, evidence and transformational change, 2007. Accessed at www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2007/rgcmo-medical-home.Par.0001.File.tmp/rgcmo-medical-home.pdf.

8. Goldberg A. It matters how we define health care equity. Institute of Medicine. Accessed at www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Perspectives-Files/2013/Commentaries/BPH-It-Matters-How-we-define-Health-Equity.pdf.

9. Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Vermont’s blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Aff 2011;30:383–6.

10. Bricker PL, Baron RJ, Scheirer JJ. Collaboration in Pennsylvania: rapidly spreading improved chronic care for patients to practices. J Cont Educ Health Prof 2010;30:114–25.

11.TransforMed. What does your medical home look like? A jumble of unconnected pieces or a coherent structure? Accessed at www.transformed.com/mhiq/welcome.cfm .