User login

Netherton Syndrome: An Atypical Presentation

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive ichthyosiform disease.1 The incidence is estimated to be 1 in 200,000 individuals.2 Netherton syndrome presents with generalized erythroderma and scaling, characteristic hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system. Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination. We report a case of NS in a man with congenital erythroderma, pili torti, and elevated IgE levels.

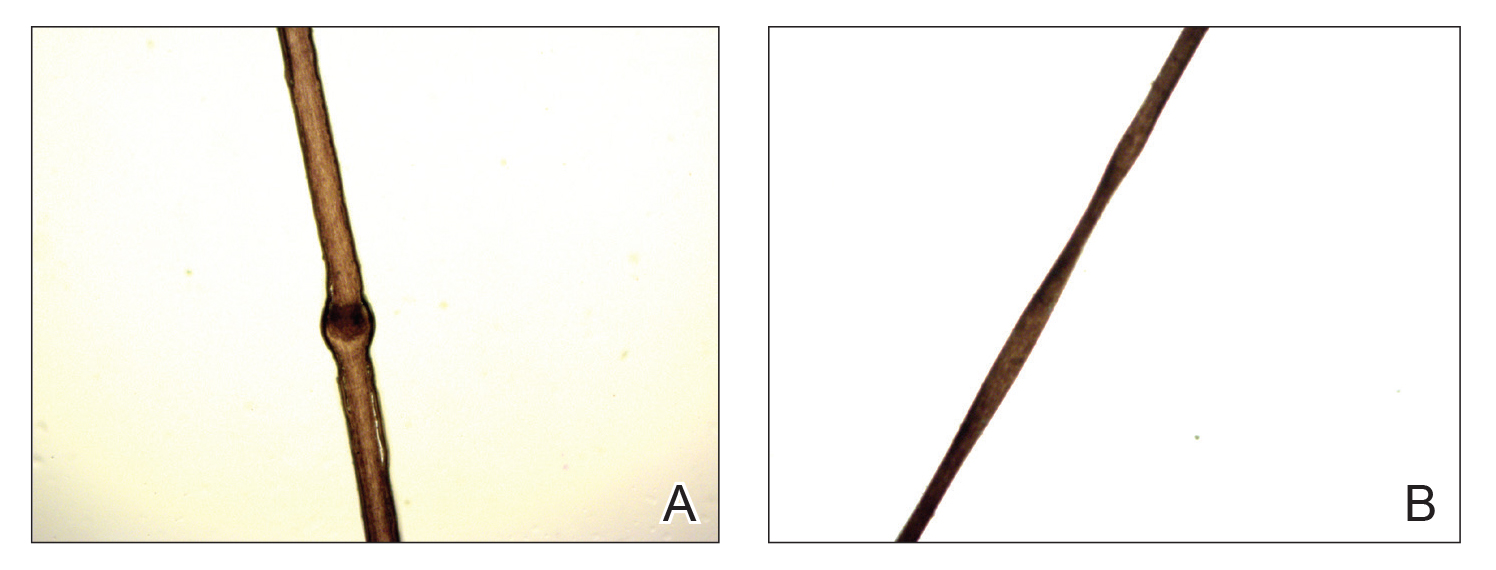

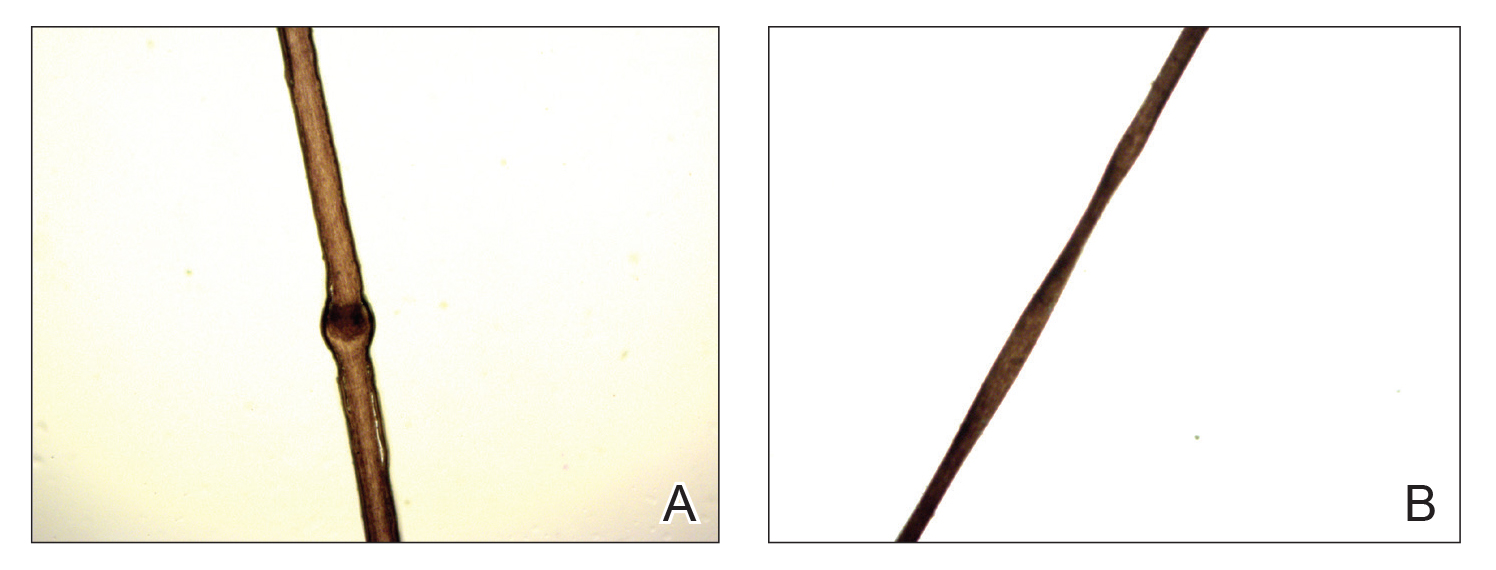

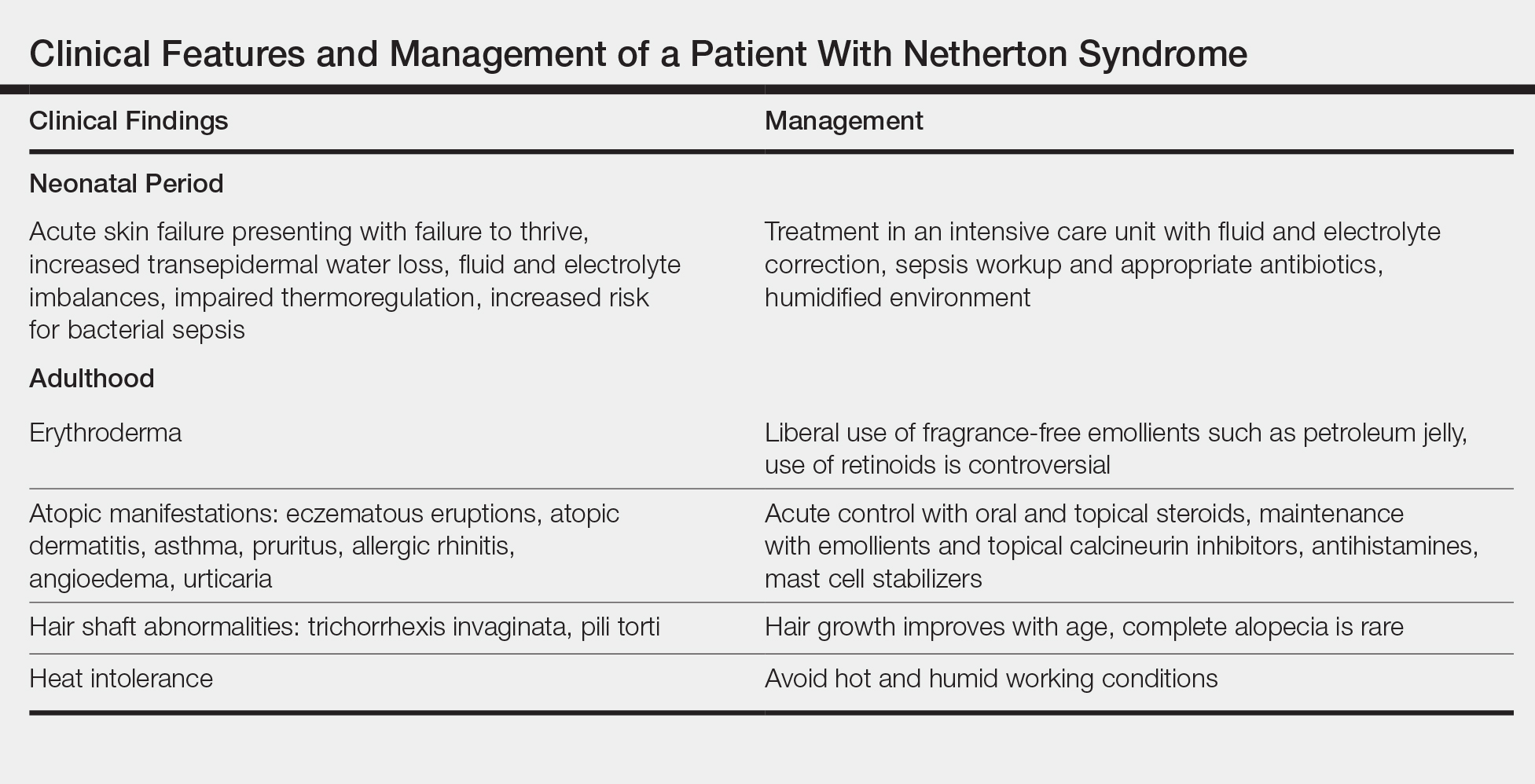

A 23-year-old man presented with generalized scaly skin that was present since birth. He was the first child born of nonconsanguineous parents. His medical history was suggestive of atopic diatheses such as allergic rhinitis and recurrent urticaria. The patient was of thin build and had widespread erythematous, annular, and polycyclic scaly lesions (Figure 1A), some with characteristic double-edged scale (Figure 1B). The skin was dry due to anhidrosis that was present since birth. Flexural lichenification was present at the cubital fossa of both arms. Scalp hairs were easily pluckable and had generalized thinning of hair density. Hair mount examination showed characteristic features of both trichorrhexis invaginata (Figure 2A) and pili torti (Figure 2B).

hair shaft known as bamboo hair or trichorrhexis invaginata. B, Features of pili torti; the hair

shaft twisted at irregular intervals.

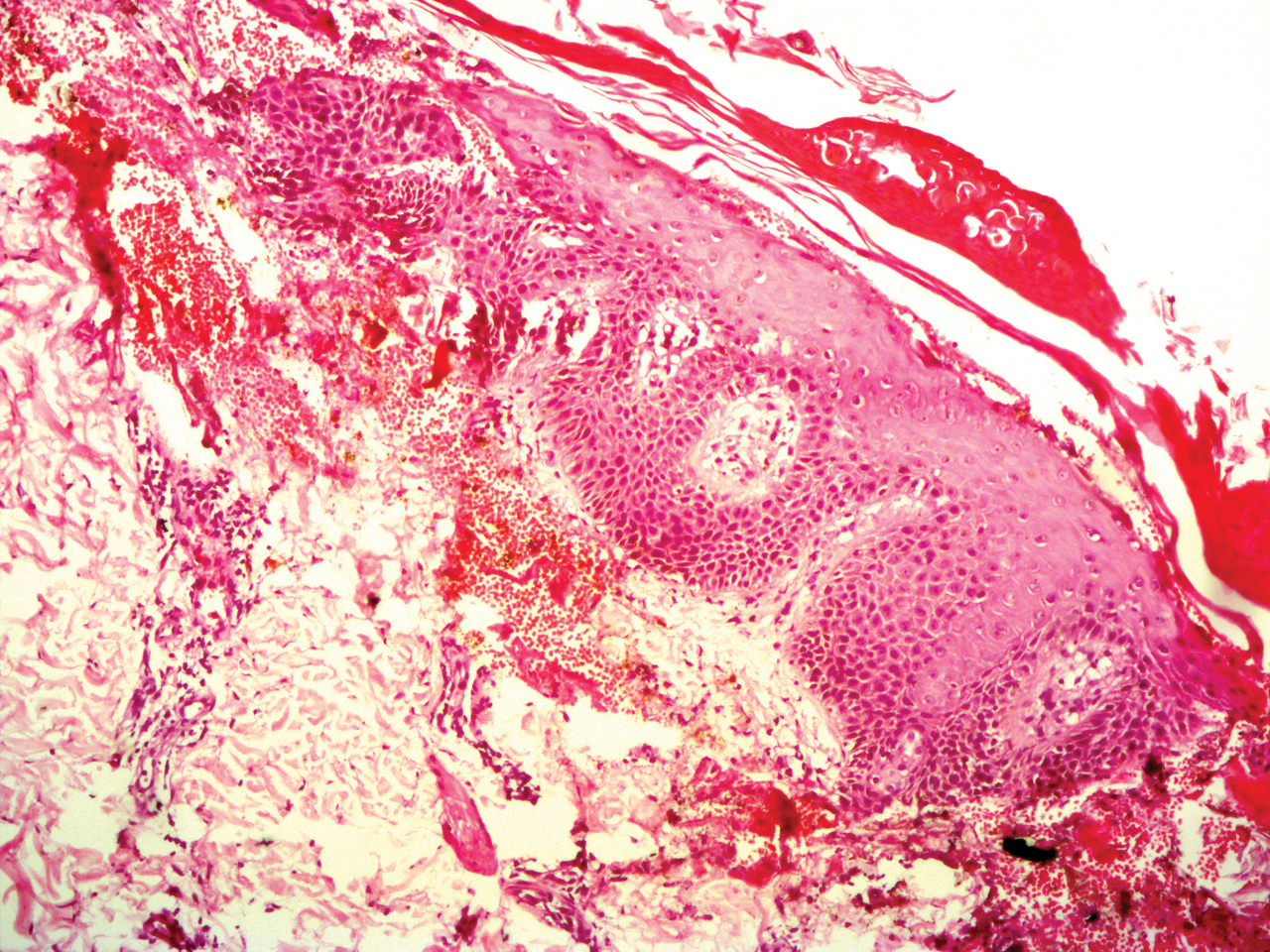

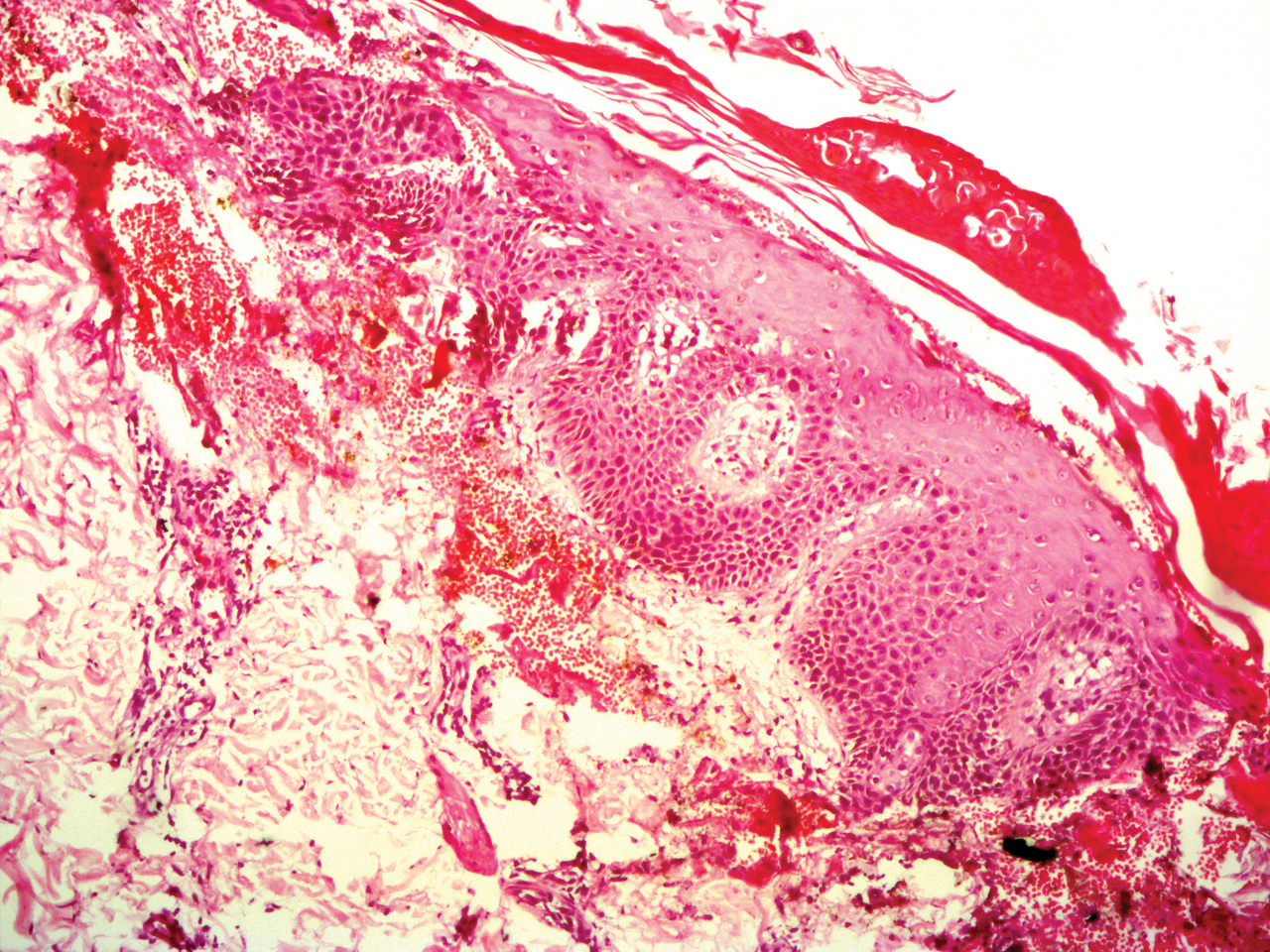

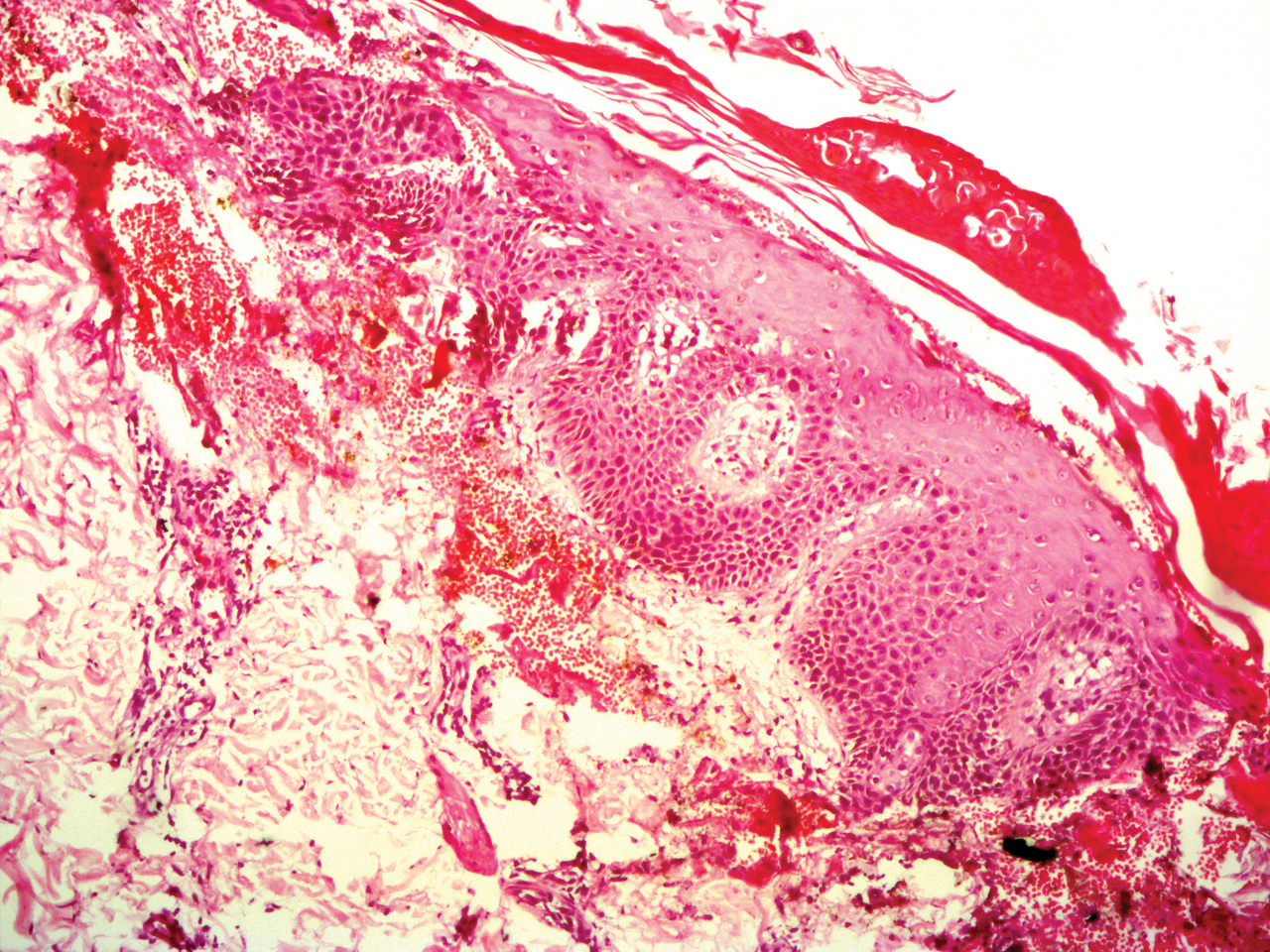

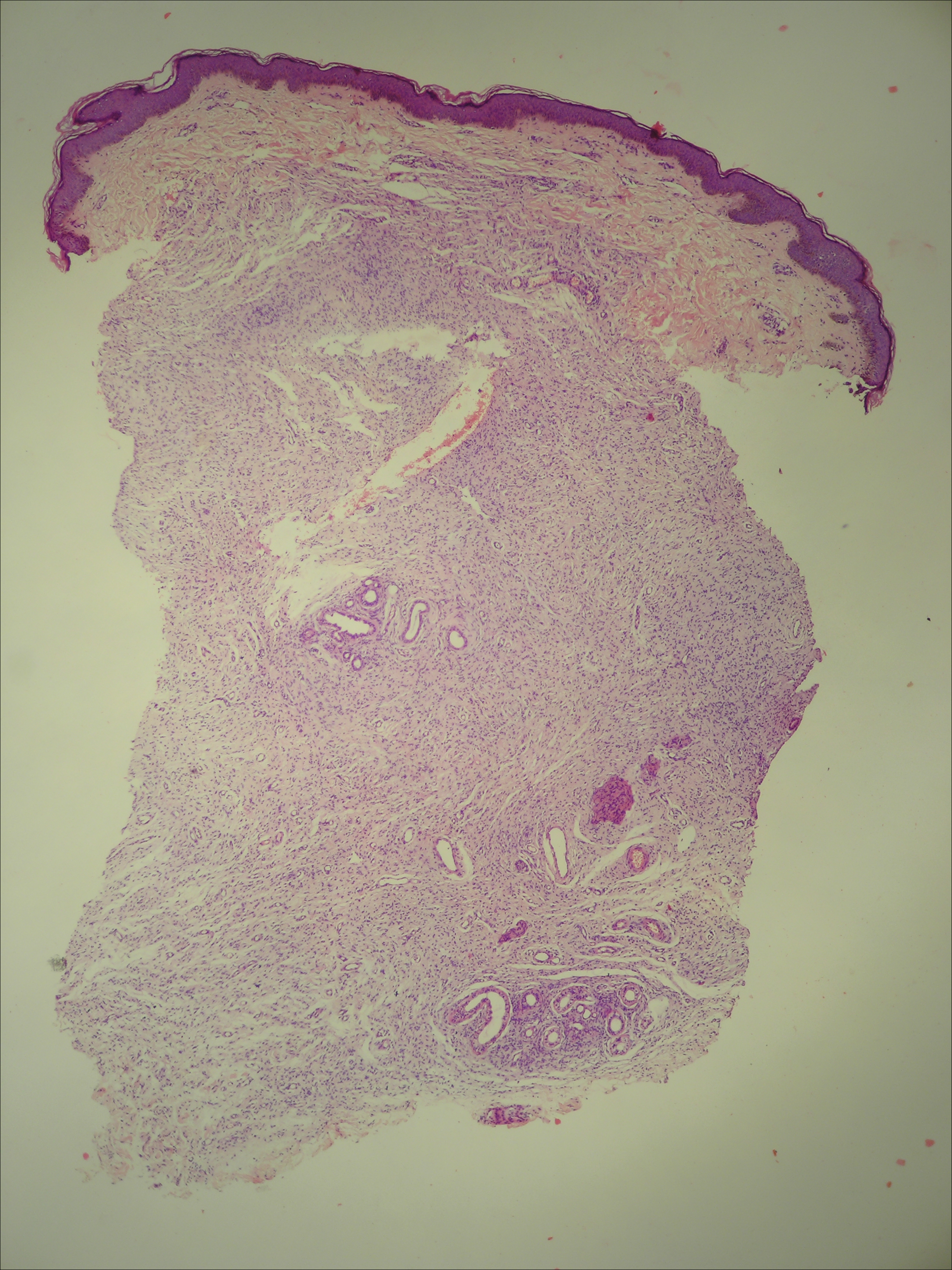

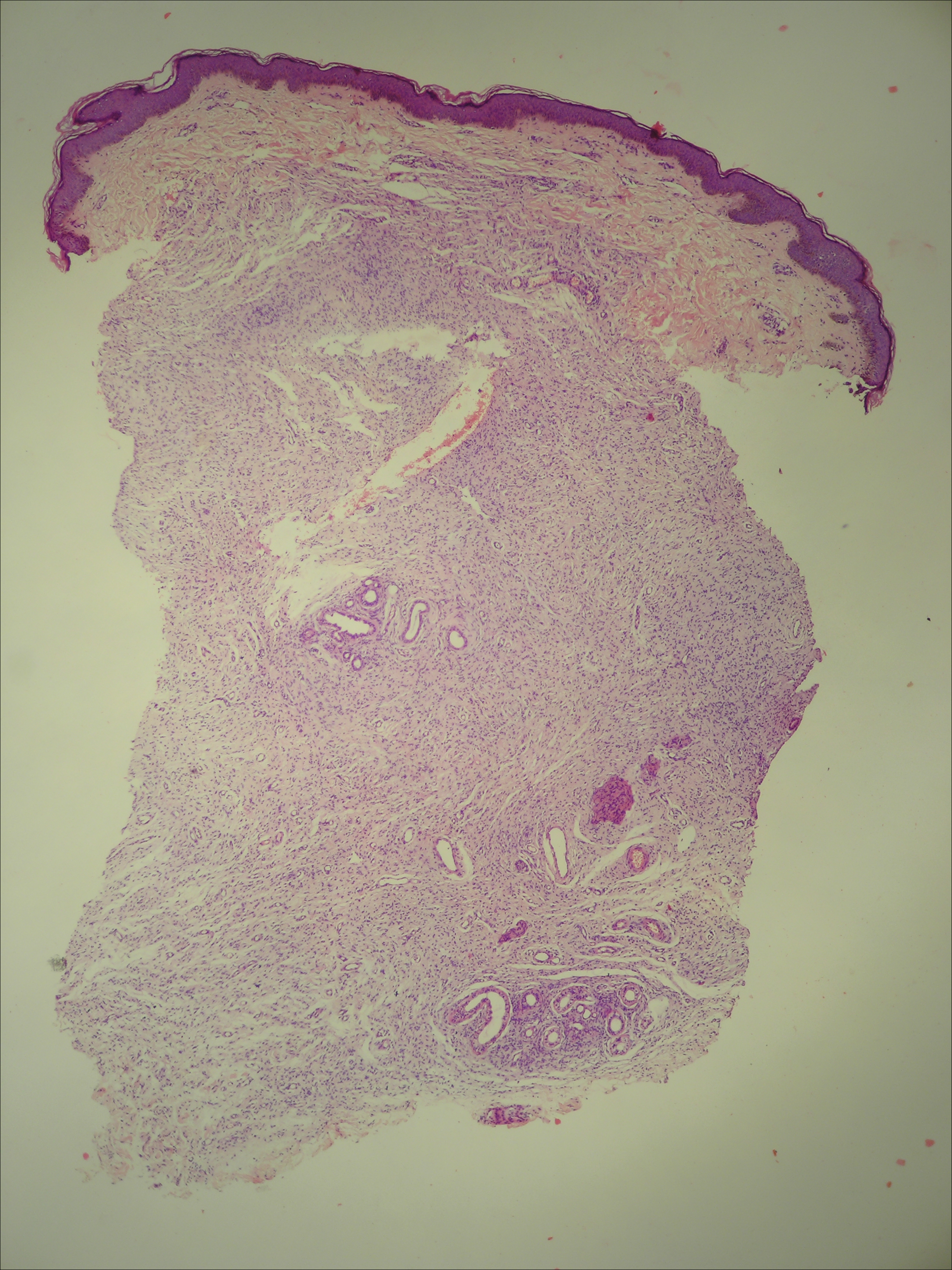

Potassium hydroxide mount from a lesion was negative for fungal elements. Complete hematologic workup showed moderate anemia at 8.0 g/dL (reference range, 8.0–10.9 g/dL) and peripheral eosinophilia at 12% (reference range, 0%–6%). His IgE level was markedly elevated at6331 IU/mL (reference range, 150–1000 IU/mL) when tested with fully automated bidirectionally interfaced chemiluminescent immunoassay. Histopathologic examination of a lesion biopsy showed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acanthosis, consistent with ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (ILC)(Figure 3). Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of ILC, trichorrhexis invaginata/pili torti, and atopic diathesis, which is a constellation of disorders related to NS.

We prescribed oral acitretin 25 mg once daily and instructed the patient to apply petroleum jelly; however, the patient returned after 2 weeks due to aggravation of the skin condition with increased scaling and redness. Because the patient showed signs of acute skin failure and erythroderma, we stopped acitretin treatment and managed his condition conservatively with the application of petroleum jelly.

Netherton syndrome is caused by mutation of the SPINK5 gene, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; the corresponding gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5.3 The gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor proprotein LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal type inhibitor).4 The product of the gene is thought to be necessary for epidermal cell growth and differentiation. The classic clinical triad of NS includes ichthyosiform dermatosis with double-edged scale, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopy or elevated IgE levels.5 Generalized (congenital) erythroderma usually becomes evident at birth or shortly thereafter. Half of patients develop lesions of ILC on the trunk and limbs during childhood.6 A typical ILC lesion is characterized by an erythematous scaly patch that may be annular or polycyclic with double-edged scale at the advancing border. The ability to sweat is impaired, which may cause episodes of hyperpyrexia, especially during humid weather. Patients with hyperpyrexia may be incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial infection and treated with antipyretic drugs or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Trichorrhexis invaginata, also referred to as bamboo hair or ball-and-socket defect, is the pathognomonic hair shaft abnormality seen in NS.7 Other hair shaft abnormalities in this syndrome include trichorrhexis nodosa and pili torti.8 Our patient had hair shaft abnormalities of trichorrhexis invaginata and pili torti, which are rare findings. The third component of this syndrome is atopy, which generally manifests as angioedema, urticaria, allergic rhinitis, peripheral eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions, asthma, and elevated IgE levels.9

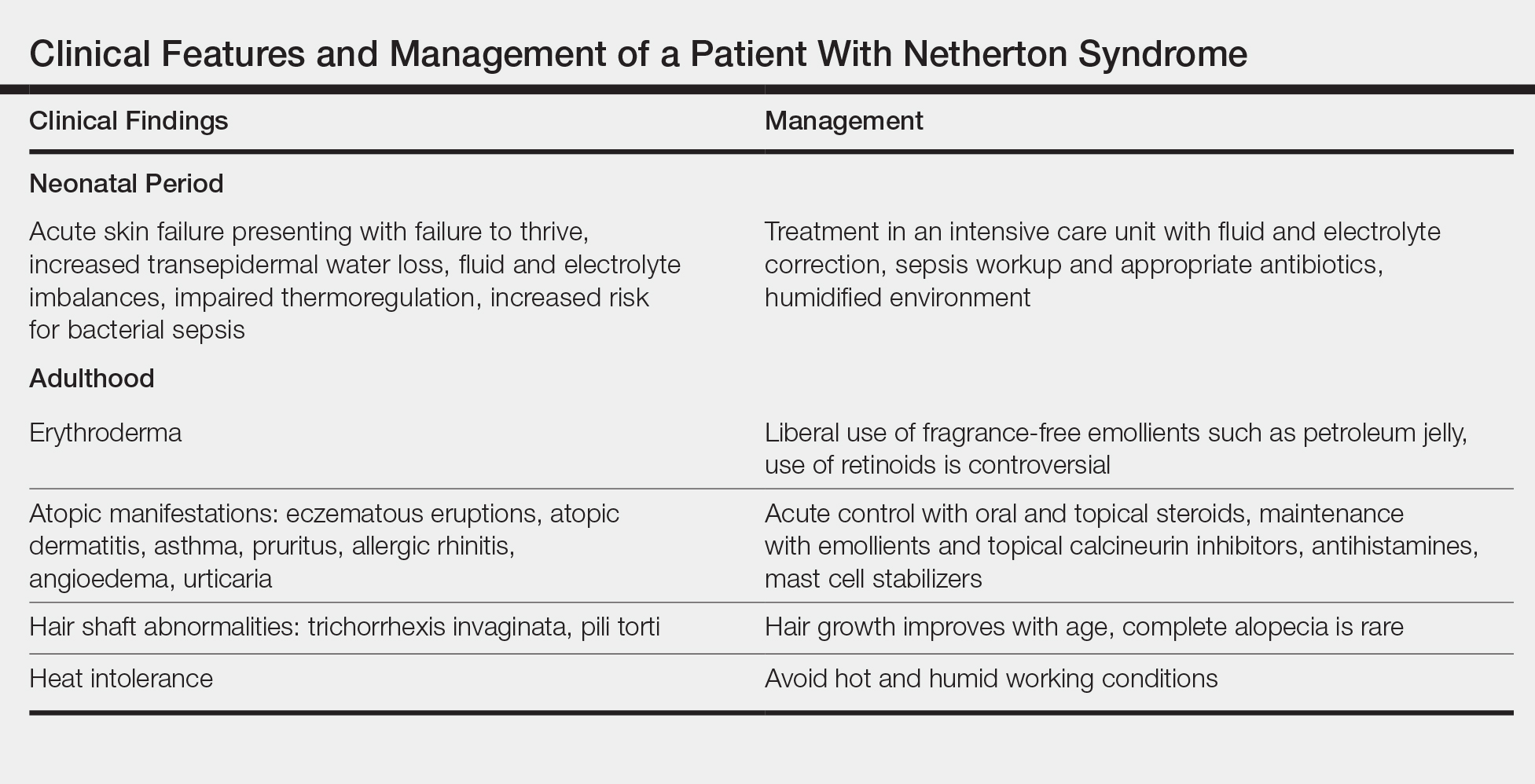

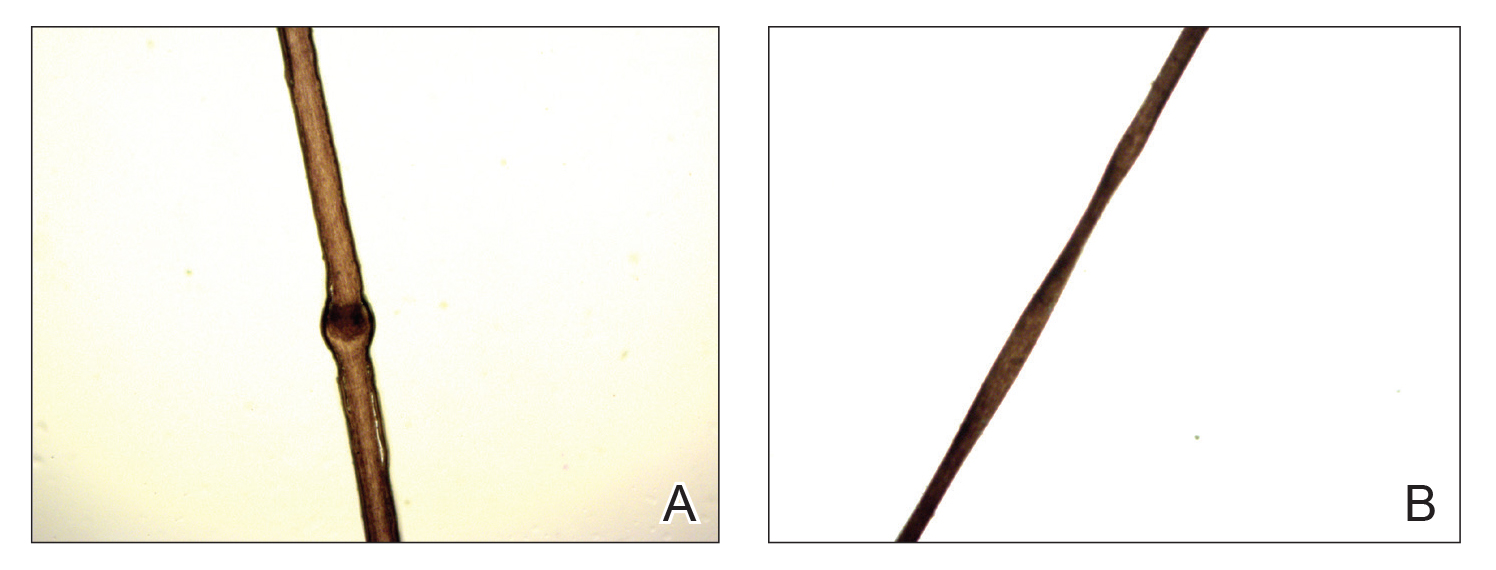

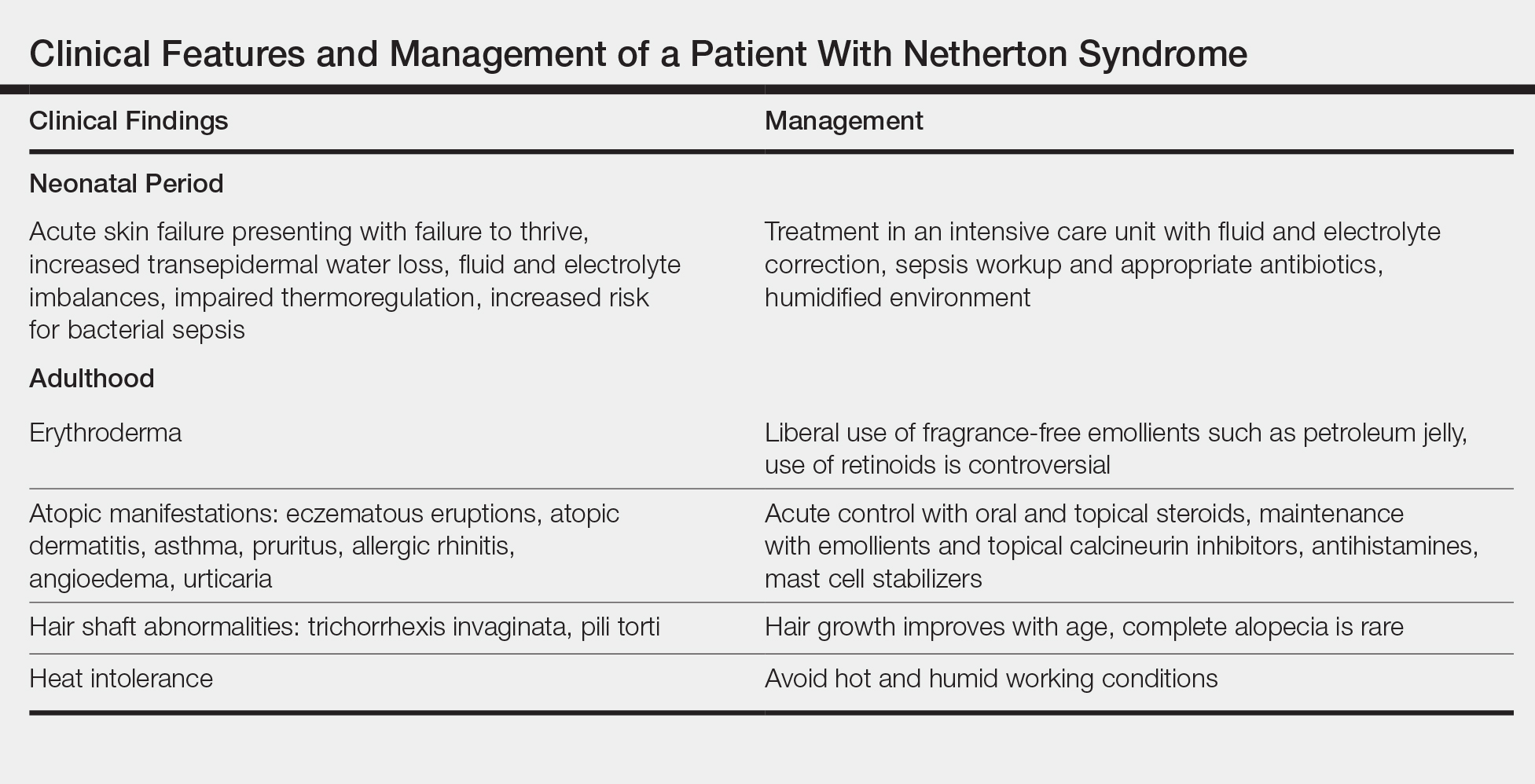

Treatment with emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, and psoralen plus UVA does not elicit a satisfactory response. The Table highlights the clinical features and management of NS.

Generally, systemic retinoid therapy is helpful in cases of erythrodermic ichthyosis, but a unique feature of NS is that erythroderma may worsen with systemic retinoid therapy, as retinoids aggravate atopic dermatitis by worsening existing xerosis.4 Our case highlights the rare association of trichorrhexis invaginata with pili torti as well as acitretin treatment worsening our patient’s condition. This paradoxical effect of retinoid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

- Suhaila O, Muzhirah A. Netherton syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pediatr Child Health. 2010;16:26.

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren D, et al. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:819-823.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:141-142.

- Judge MR, Mclean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:19.1-19.122.

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:329-337.

- Khan I-U, Chaudhary R. Netherton’s syndrome, an uncommon genodermatosis. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2006;16.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:611-612.

- Hurwitz S. Hereditary skin disorders: the genodermatoses. In: Hurwitz, ed. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:173.

- Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 2004:34.35.

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive ichthyosiform disease.1 The incidence is estimated to be 1 in 200,000 individuals.2 Netherton syndrome presents with generalized erythroderma and scaling, characteristic hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system. Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination. We report a case of NS in a man with congenital erythroderma, pili torti, and elevated IgE levels.

A 23-year-old man presented with generalized scaly skin that was present since birth. He was the first child born of nonconsanguineous parents. His medical history was suggestive of atopic diatheses such as allergic rhinitis and recurrent urticaria. The patient was of thin build and had widespread erythematous, annular, and polycyclic scaly lesions (Figure 1A), some with characteristic double-edged scale (Figure 1B). The skin was dry due to anhidrosis that was present since birth. Flexural lichenification was present at the cubital fossa of both arms. Scalp hairs were easily pluckable and had generalized thinning of hair density. Hair mount examination showed characteristic features of both trichorrhexis invaginata (Figure 2A) and pili torti (Figure 2B).

hair shaft known as bamboo hair or trichorrhexis invaginata. B, Features of pili torti; the hair

shaft twisted at irregular intervals.

Potassium hydroxide mount from a lesion was negative for fungal elements. Complete hematologic workup showed moderate anemia at 8.0 g/dL (reference range, 8.0–10.9 g/dL) and peripheral eosinophilia at 12% (reference range, 0%–6%). His IgE level was markedly elevated at6331 IU/mL (reference range, 150–1000 IU/mL) when tested with fully automated bidirectionally interfaced chemiluminescent immunoassay. Histopathologic examination of a lesion biopsy showed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acanthosis, consistent with ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (ILC)(Figure 3). Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of ILC, trichorrhexis invaginata/pili torti, and atopic diathesis, which is a constellation of disorders related to NS.

We prescribed oral acitretin 25 mg once daily and instructed the patient to apply petroleum jelly; however, the patient returned after 2 weeks due to aggravation of the skin condition with increased scaling and redness. Because the patient showed signs of acute skin failure and erythroderma, we stopped acitretin treatment and managed his condition conservatively with the application of petroleum jelly.

Netherton syndrome is caused by mutation of the SPINK5 gene, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; the corresponding gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5.3 The gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor proprotein LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal type inhibitor).4 The product of the gene is thought to be necessary for epidermal cell growth and differentiation. The classic clinical triad of NS includes ichthyosiform dermatosis with double-edged scale, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopy or elevated IgE levels.5 Generalized (congenital) erythroderma usually becomes evident at birth or shortly thereafter. Half of patients develop lesions of ILC on the trunk and limbs during childhood.6 A typical ILC lesion is characterized by an erythematous scaly patch that may be annular or polycyclic with double-edged scale at the advancing border. The ability to sweat is impaired, which may cause episodes of hyperpyrexia, especially during humid weather. Patients with hyperpyrexia may be incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial infection and treated with antipyretic drugs or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Trichorrhexis invaginata, also referred to as bamboo hair or ball-and-socket defect, is the pathognomonic hair shaft abnormality seen in NS.7 Other hair shaft abnormalities in this syndrome include trichorrhexis nodosa and pili torti.8 Our patient had hair shaft abnormalities of trichorrhexis invaginata and pili torti, which are rare findings. The third component of this syndrome is atopy, which generally manifests as angioedema, urticaria, allergic rhinitis, peripheral eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions, asthma, and elevated IgE levels.9

Treatment with emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, and psoralen plus UVA does not elicit a satisfactory response. The Table highlights the clinical features and management of NS.

Generally, systemic retinoid therapy is helpful in cases of erythrodermic ichthyosis, but a unique feature of NS is that erythroderma may worsen with systemic retinoid therapy, as retinoids aggravate atopic dermatitis by worsening existing xerosis.4 Our case highlights the rare association of trichorrhexis invaginata with pili torti as well as acitretin treatment worsening our patient’s condition. This paradoxical effect of retinoid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

To the Editor:

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive ichthyosiform disease.1 The incidence is estimated to be 1 in 200,000 individuals.2 Netherton syndrome presents with generalized erythroderma and scaling, characteristic hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system. Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination. We report a case of NS in a man with congenital erythroderma, pili torti, and elevated IgE levels.

A 23-year-old man presented with generalized scaly skin that was present since birth. He was the first child born of nonconsanguineous parents. His medical history was suggestive of atopic diatheses such as allergic rhinitis and recurrent urticaria. The patient was of thin build and had widespread erythematous, annular, and polycyclic scaly lesions (Figure 1A), some with characteristic double-edged scale (Figure 1B). The skin was dry due to anhidrosis that was present since birth. Flexural lichenification was present at the cubital fossa of both arms. Scalp hairs were easily pluckable and had generalized thinning of hair density. Hair mount examination showed characteristic features of both trichorrhexis invaginata (Figure 2A) and pili torti (Figure 2B).

hair shaft known as bamboo hair or trichorrhexis invaginata. B, Features of pili torti; the hair

shaft twisted at irregular intervals.

Potassium hydroxide mount from a lesion was negative for fungal elements. Complete hematologic workup showed moderate anemia at 8.0 g/dL (reference range, 8.0–10.9 g/dL) and peripheral eosinophilia at 12% (reference range, 0%–6%). His IgE level was markedly elevated at6331 IU/mL (reference range, 150–1000 IU/mL) when tested with fully automated bidirectionally interfaced chemiluminescent immunoassay. Histopathologic examination of a lesion biopsy showed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, papillomatosis, and acanthosis, consistent with ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (ILC)(Figure 3). Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of ILC, trichorrhexis invaginata/pili torti, and atopic diathesis, which is a constellation of disorders related to NS.

We prescribed oral acitretin 25 mg once daily and instructed the patient to apply petroleum jelly; however, the patient returned after 2 weeks due to aggravation of the skin condition with increased scaling and redness. Because the patient showed signs of acute skin failure and erythroderma, we stopped acitretin treatment and managed his condition conservatively with the application of petroleum jelly.

Netherton syndrome is caused by mutation of the SPINK5 gene, serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5; the corresponding gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 5.3 The gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor proprotein LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal type inhibitor).4 The product of the gene is thought to be necessary for epidermal cell growth and differentiation. The classic clinical triad of NS includes ichthyosiform dermatosis with double-edged scale, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopy or elevated IgE levels.5 Generalized (congenital) erythroderma usually becomes evident at birth or shortly thereafter. Half of patients develop lesions of ILC on the trunk and limbs during childhood.6 A typical ILC lesion is characterized by an erythematous scaly patch that may be annular or polycyclic with double-edged scale at the advancing border. The ability to sweat is impaired, which may cause episodes of hyperpyrexia, especially during humid weather. Patients with hyperpyrexia may be incorrectly diagnosed with bacterial infection and treated with antipyretic drugs or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Trichorrhexis invaginata, also referred to as bamboo hair or ball-and-socket defect, is the pathognomonic hair shaft abnormality seen in NS.7 Other hair shaft abnormalities in this syndrome include trichorrhexis nodosa and pili torti.8 Our patient had hair shaft abnormalities of trichorrhexis invaginata and pili torti, which are rare findings. The third component of this syndrome is atopy, which generally manifests as angioedema, urticaria, allergic rhinitis, peripheral eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis–like skin lesions, asthma, and elevated IgE levels.9

Treatment with emollients, topical steroids, tacrolimus, and psoralen plus UVA does not elicit a satisfactory response. The Table highlights the clinical features and management of NS.

Generally, systemic retinoid therapy is helpful in cases of erythrodermic ichthyosis, but a unique feature of NS is that erythroderma may worsen with systemic retinoid therapy, as retinoids aggravate atopic dermatitis by worsening existing xerosis.4 Our case highlights the rare association of trichorrhexis invaginata with pili torti as well as acitretin treatment worsening our patient’s condition. This paradoxical effect of retinoid therapy further confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

- Suhaila O, Muzhirah A. Netherton syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pediatr Child Health. 2010;16:26.

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren D, et al. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:819-823.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:141-142.

- Judge MR, Mclean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:19.1-19.122.

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:329-337.

- Khan I-U, Chaudhary R. Netherton’s syndrome, an uncommon genodermatosis. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2006;16.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:611-612.

- Hurwitz S. Hereditary skin disorders: the genodermatoses. In: Hurwitz, ed. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:173.

- Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 2004:34.35.

- Suhaila O, Muzhirah A. Netherton syndrome: a case report. Malaysian J Pediatr Child Health. 2010;16:26.

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren D, et al. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turk J Med Sci. 2010;40:819-823.

- Chavanas S, Bodemer C, Rochat A, et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;25:141-142.

- Judge MR, Mclean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Singapore: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:19.1-19.122.

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome. report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:329-337.

- Khan I-U, Chaudhary R. Netherton’s syndrome, an uncommon genodermatosis. J Pakistan Assoc Dermatol. 2006;16.

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:611-612.

- Hurwitz S. Hereditary skin disorders: the genodermatoses. In: Hurwitz, ed. Clinical Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1993:173.

- Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. Vol 2. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science; 2004:34.35.

Practice Points

- Netherton syndrome is characterized by generalized erythroderma and scaling, hair shaft abnormalities, and dysregulation of the immune system.

- Treatment is largely symptomatic and includes fragrance-free emollients, keratolytics, tretinoin, and corticosteroids, either alone or in combination.

Phacomatosis Cesioflammea in Association With von Recklinghausen Disease (Neurofibromatosis Type I)

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

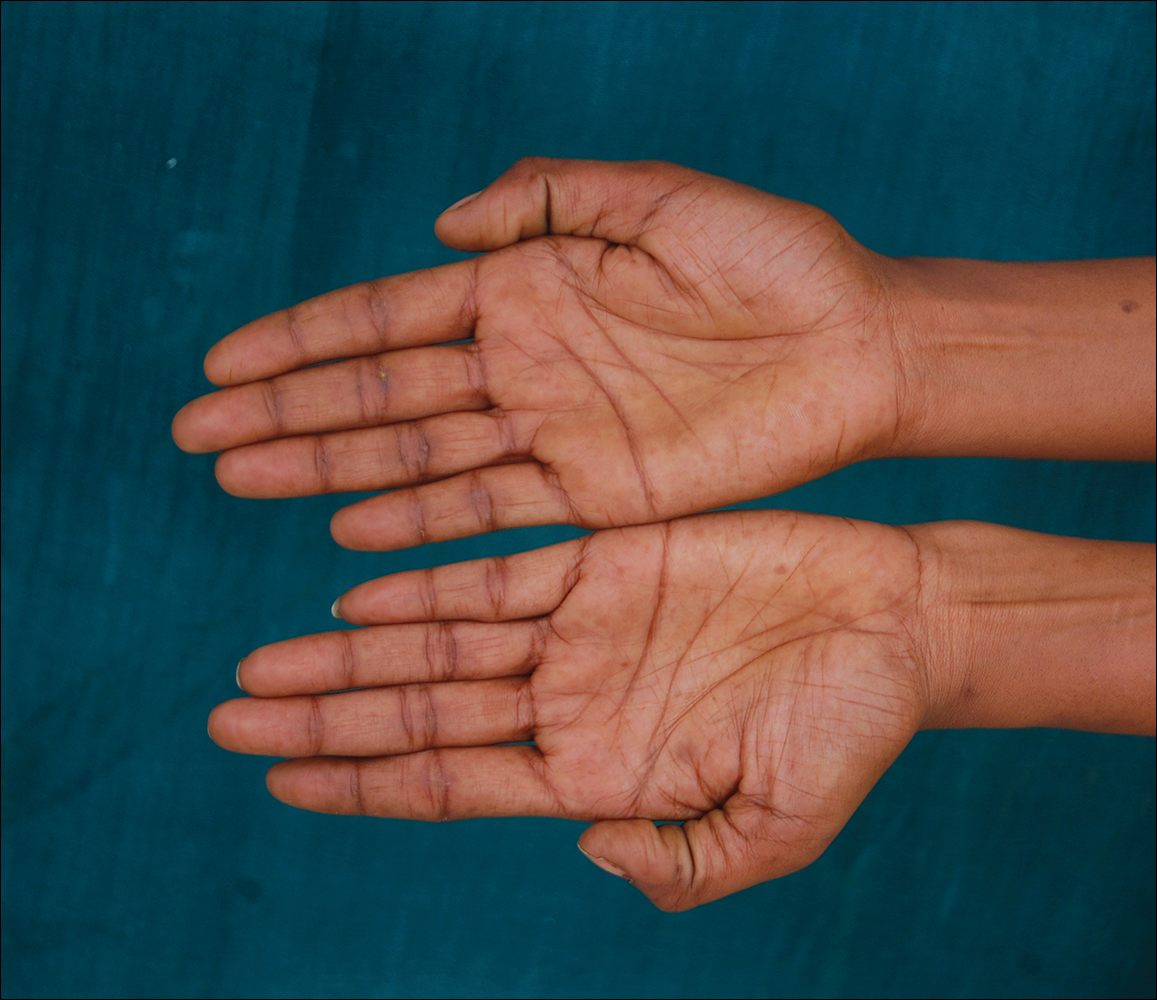

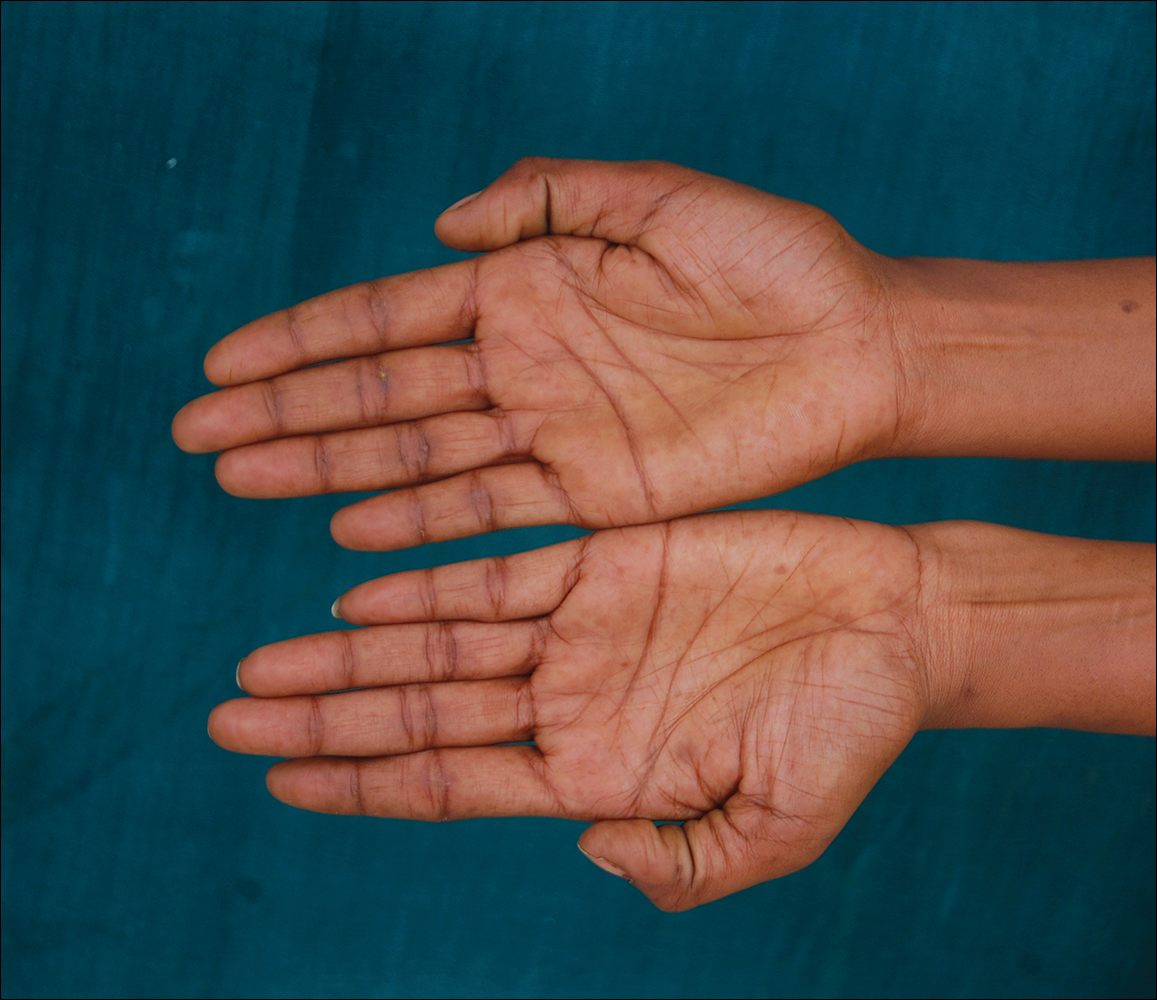

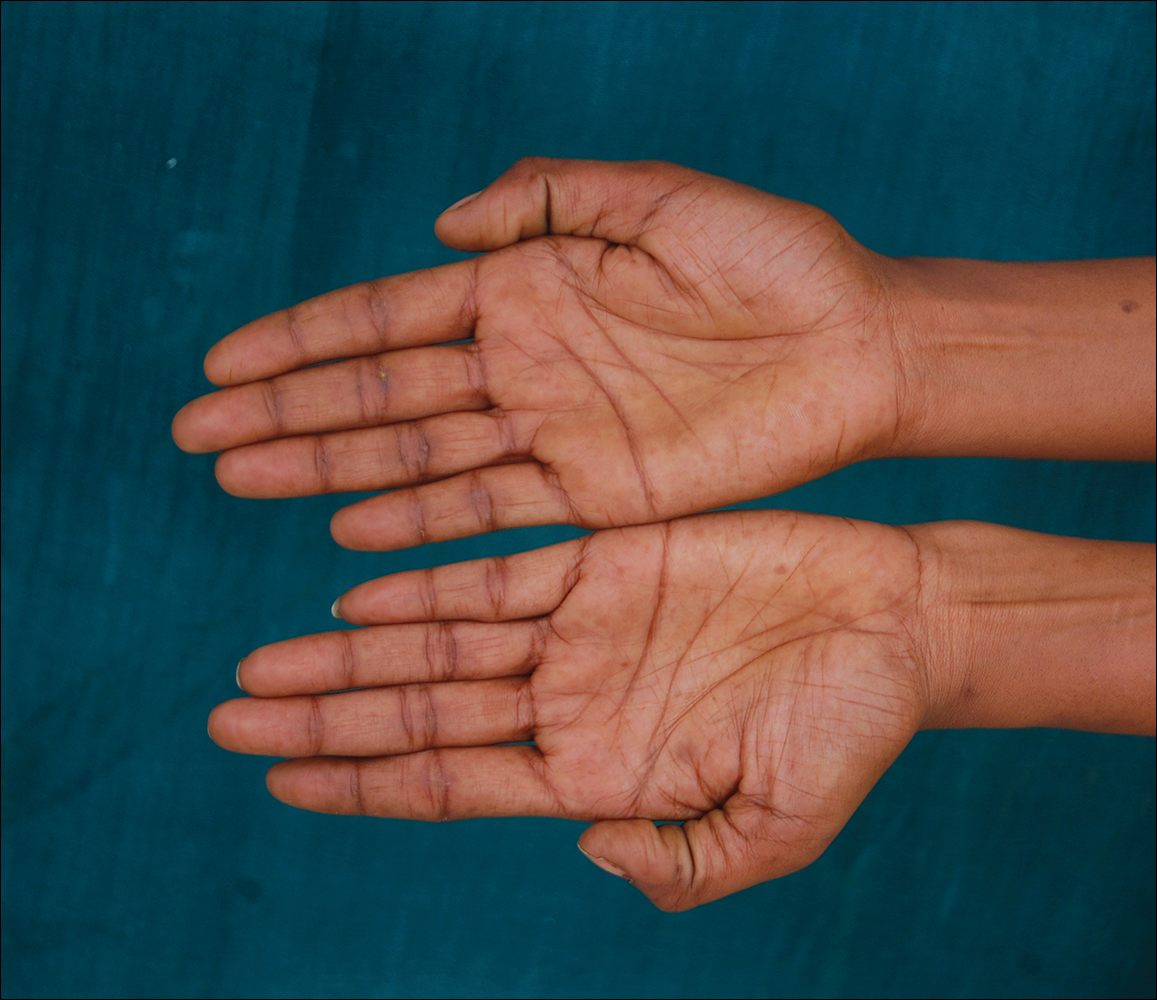

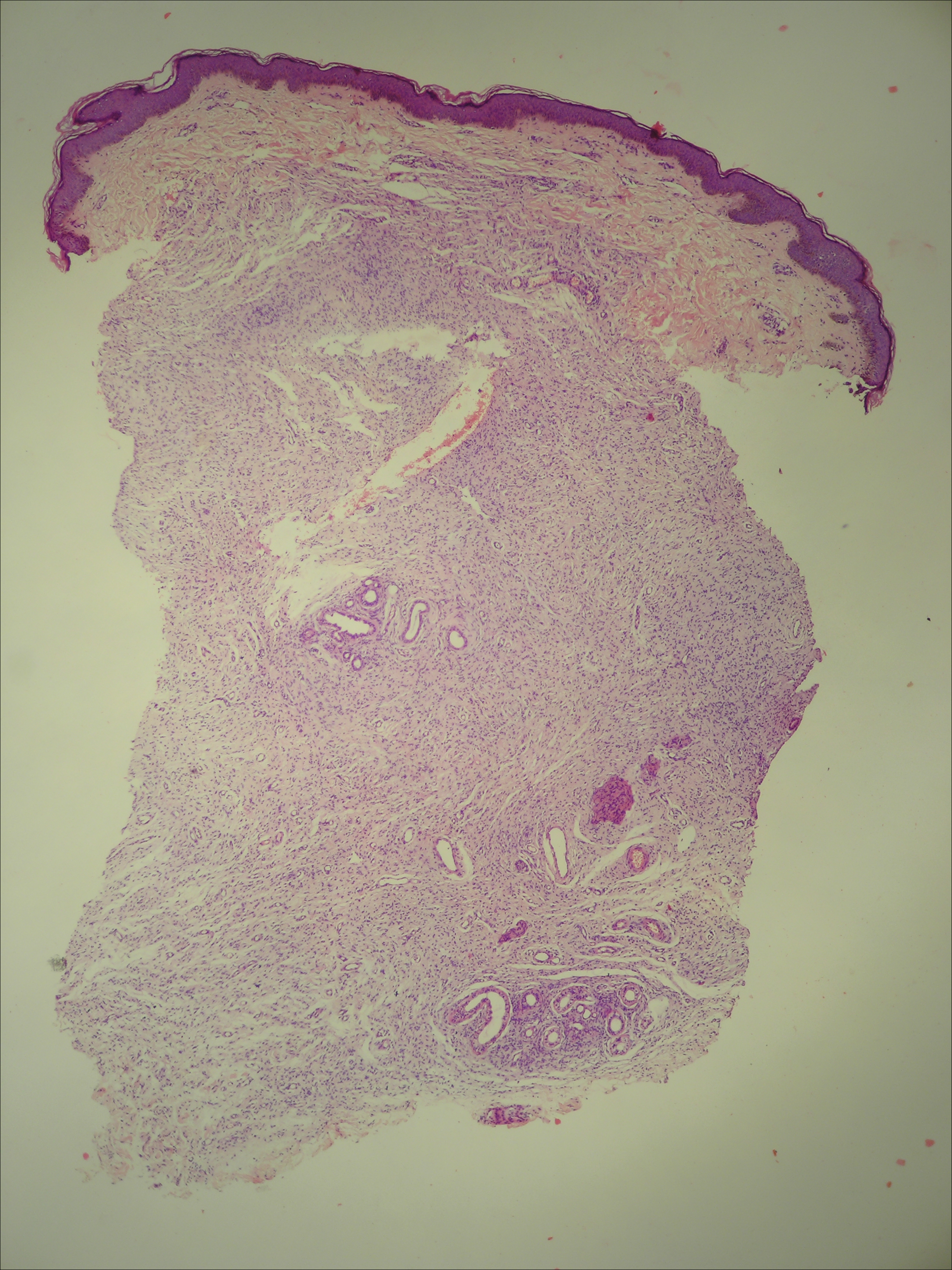

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

Practice Points

- Phacomatosis cesioflammea can be associated with neurofibromatosis type I.

- The port-wine stain component of phacomatosis cesioflammea may develop nodularity in long-standing cases.

- The Nd:YAG laser is beneficial for treating blue spots of phacomatosis cesioflammea.