User login

Etiquette‐Based Medicine Among Interns

Patient‐centered communication may impact several aspects of the patientdoctor relationship including patient disclosure of illness‐related information, patient satisfaction, anxiety, and compliance with medical recommendations.[1, 2, 3, 4] Etiquette‐based medicine, a term coined by Kahn, involves simple patient‐centered communication strategies that convey professionalism and respect to patients.[5] Studies have confirmed that patients prefer physicians who practice etiquette‐based medicine behaviors, including sitting down and introducing one's self.[6, 7, 8, 9] Performance of etiquette‐based medicine is associated with higher Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores. However, these easy‐to‐practice behaviors may not be modeled commonly in the inpatient setting.[10] We sought to understand whether etiquette‐based communication behaviors are practiced by trainees on inpatient medicine rotations.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective study incorporating direct observation of intern interactions with patients during January 2012 at 2 internal medicine residency programs in Baltimore Maryland, Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC). We then surveyed participants from JHH in June 2012 to assess perceptions of their practice of etiquette‐based communication.

Participants and Setting

We observed a convenience sample of 29 internal medicine interns from the 2 institutions. We sought to observe interns over an equal number of hours at both sites and to sample shifts in proportion to the amount of time interns spend on each of these shifts. All interns who were asked to participate in the study agreed and comprised a total of 27% of the 108 interns in the 2 programs. The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine approved the study; the University of Maryland institutional review board deemed it not human subjects research. All observed interns provided informed consent to be observed during 1 to 4 inpatient shifts.

Observers

Twenty‐two undergraduate university students served as the observers for the study and were trained to collect data with the iPod Touch (Apple, Cupertino, CA) without interrupting patient care. We then tested the observers to ensure 85% concordance rate with the researchers in mock observation. Four hours of quality assurance were completed at both institutions during the study. Congruence between observer and research team member was >85% for each hour of observation.

Observation

Observers recorded intern activities on the iPod Touch spreadsheet application. The application allowed for real‐time data entry and direct export of results. The primary dependent variables for this study were 5 behaviors that were assessed each time an intern went into a patient's room. The 5 observed behaviors included (1) introducing one's self, (2) introducing one's role on the medical team, (3) touching the patient, (4) sitting down, and (5) asking the patient at least 1 open‐ended question. These behaviors were chosen for observation because they are central to Kahn's framework of etiquette‐based medicine, applicable to each inpatient encounter, and readily observed by trained nonmedical observers. These behaviors are defined in Table 1. Use of open‐ended questions was observed as a more general form of Kahn's recommendation to ask how the patient is feeling. Interns were not aware of which behaviors were being evaluated.

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Introduced self | Providing a name |

| Introduced role | Uses term doctor, resident, intern, or medical team |

| Sat down | Sitting on the bed, in a chair, or crouching if no chair was available during at least part of the encounter |

| Touched the patient | Any form of physical contact that occurred at least once during the encounter including shaking a patient's hand, touching a patient on the shoulder, or performing any part of the physical exam |

| Asked open‐ended question | Asked the patient any question that required more than a yes/no answer |

Each time an observed intern entered a patient room, the observer recorded whether or not each of the 5 behaviors was performed, coded as a dichotomous variable. Although data collection was anonymous, observers recorded the team, hospital site, gender of the intern, and whether the intern was admitting new patients during the shift.

Survey

Following the observational portion of the study, participants at JHH completed a cross‐sectional, anonymous survey that asked them to estimate how frequently they currently performed each of the behaviors observed in this study. Response options included the following categories: 20%, 20% to 40%, 40% to 60%, 60% to 80%, or 80% to 100%.

Data Analysis

We determined the percent of patient visits during which each behavior was performed. Data were analyzed using Student t and [2] tests evaluating differences by hospital, intern gender, type of shift, and time of day. To account for correlation within subjects and observers, we performed multilevel logistic regression analysis adjusted for clustering at the intern and observer levels. For the survey analysis, the mean of the response category was used as the basis for comparison. All quantitative analyses were performed in Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and Stata/IC version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 732 inpatient encounters were observed during 118 intern shifts. Interns were observed for a mean of 25 patient encounters each (range, 361; standard deviation [SD] 17). Overall, interns introduced themselves 40% of the time and stated their role 37% of the time (Table 2). Interns touched patients on 65% of visits, sat down with patients during 9% of visits, and asked open‐ended questions on 75% of visits. Interns performed all 5 of the behaviors during 4% of the total encounters. The percentage of the 5 behaviors performed by each intern during all observed visits ranged from 24% to 100%, with a mean of 51% (SD 17%) per intern.

| Total Encounters, N (%) | Introduced Self (%) | Introduced Role (%) | Touched Patient (%) | Sat Down (%) | Open‐Ended Question (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Overall | 732 | 40 | 37 | 65 | 9 | 75 |

| JHH | 373 (51) | 35ab | 29ab | 62a | 10 | 70a |

| UMMC | 359 (49) | 45 | 44 | 69 | 8 | 81 |

| Male | 284 (39) | 39 | 35 | 64 | 9 | 74 |

| Female | 448 (61) | 41 | 38 | 67 | 10 | 76 |

| Day shift | 551 (75) | 37a | 34a | 65 | 9 | 77 |

| Night shift | 181 (25) | 48 | 45 | 67 | 12 | 71 |

| Admitting shift | 377 (52) | 46a | 42a | 63 | 10 | 75 |

| Nonadmitting shift | 355 (48) | 34 | 30 | 69 | 9 | 76 |

During night shifts as compared to day shifts, interns were more likely to introduce themselves (48% vs 37%, P=0.01) and their role (45% vs 34%, P0.01). During shifts in which they admitted patients as compared to coverage shifts, interns were more likely to introduce themselves (46% vs 34%, P0.01) and their role (42% vs 30%, P0.01). Interns at UMMC as compared to JHH interns were more likely to introduce themselves (45% vs 35%, P0.01) and describe their role to patients (44% vs 29%, P0.01). Interns at UMMC were also more likely to ask open‐ended questions (81% vs 70%, P0.01) and to touch patients (69% vs 62%, P=0.04). Performance of these behaviors did not vary significantly by gender, time of day, or shift. After adjustment for clustering at the observer and intern levels, differences by institution persisted in the rate of introducing oneself and one's role.

We performed a sensitivity analysis examining the first patient encounters of the day, and found that interns were somewhat more likely to introduce themselves (50% vs 40%, P=0.03) but were not significantly more likely to introduce their role, sit down, ask open‐ended questions, or touch the patient.

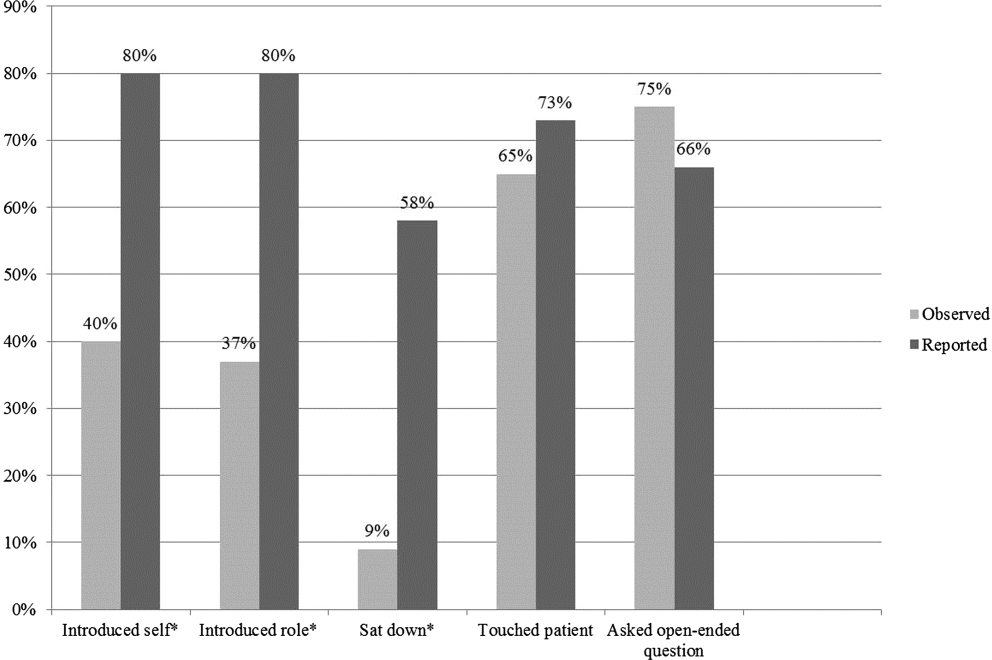

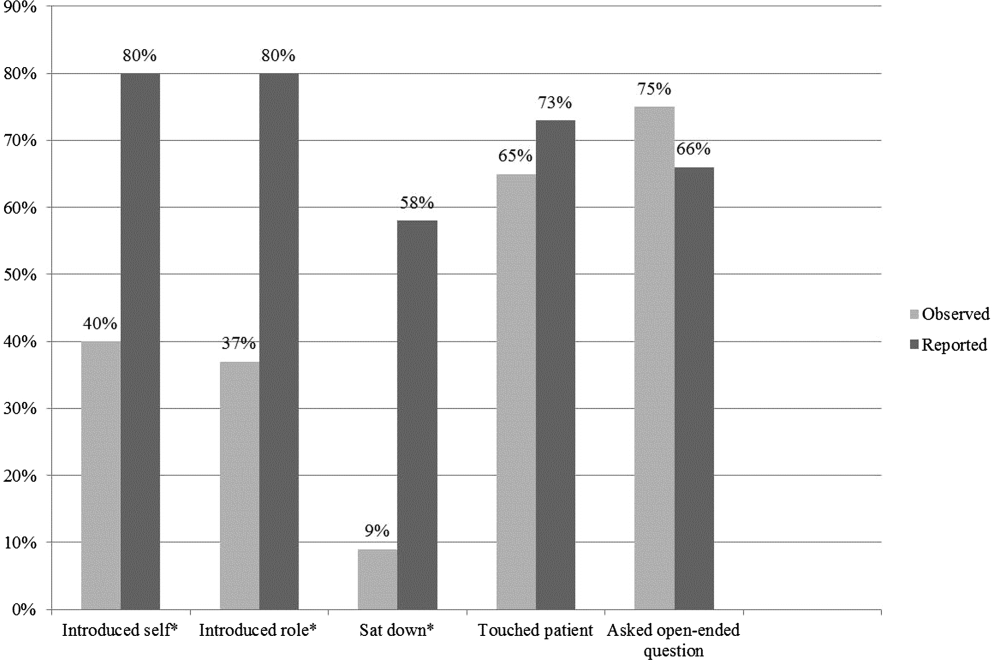

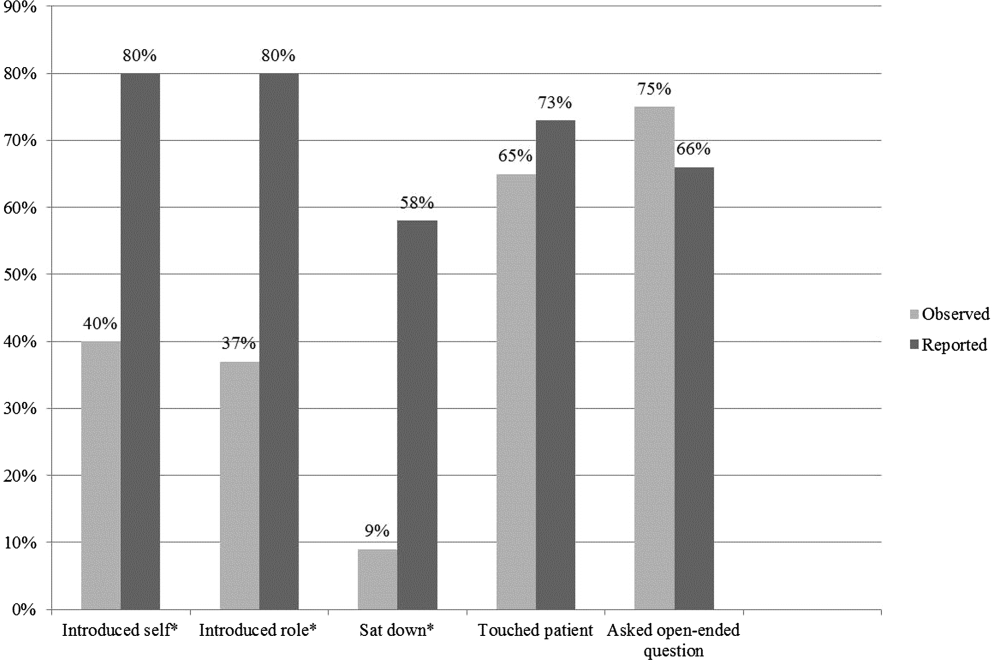

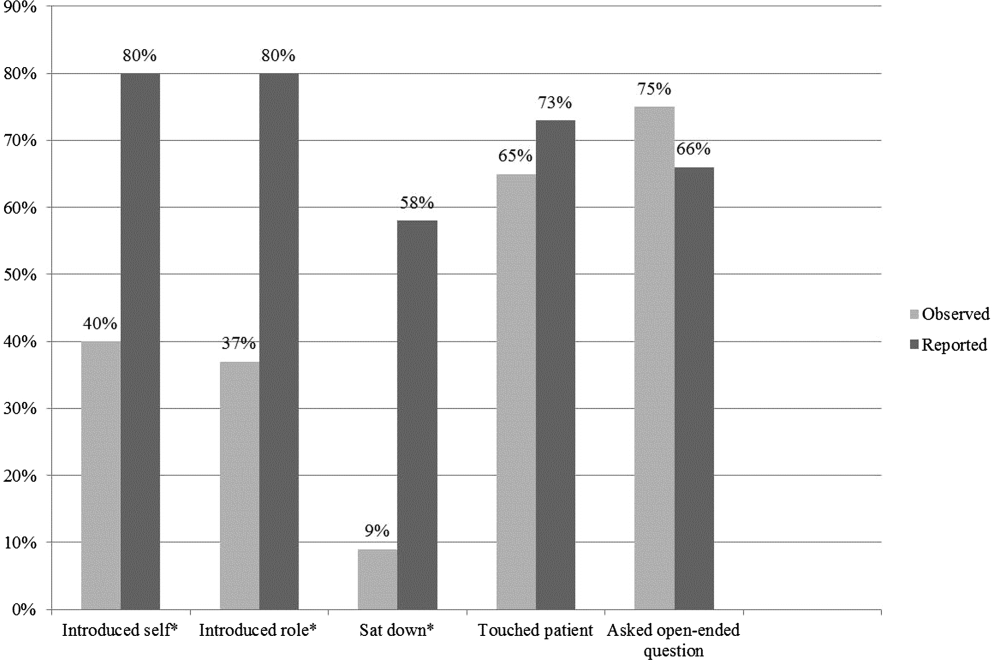

Nine of the 10 interns at JHH who participated in the study completed the survey (response rate=90%). Interns estimated introducing themselves and their role and sitting with patients significantly more frequently than was observed (80% vs 40%, P0.01; 80% vs 37%, P0.01; and 58% vs 9%, P0.01, respectively) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The interns we observed in 2 urban academic internal medicine residency programs did not routinely practice etiquette‐based communication. Interns surveyed tended to overestimate their performance of these behaviors. These behaviors are simple to perform and are each associated with improved patient experiences of hospital care. Tackett et al. recently demonstrated that interns are not alone. Hospitalist physicians do not universally practice etiquette‐based medicine, even though these behaviors correlate with patient satisfaction scores.[10]

Introducing oneself to patients may improve patient satisfaction and acceptance of trainee involvement in care.[6] However, only 10% of hospitalized patients in 1 study correctly identified a physician on their inpatient team, demonstrating the need for introductions during each and every inpatient encounter.[11] The interns we observed introduced themselves to patients in only 40% of encounters. During admitting shifts, when the first encounter with a patient likely took place, interns introduced themselves during 46% of encounters.

A comforting touch has been shown to reduce anxiety levels among patients and improve compliance with treatment regimens, but the interns did not touch patients in one‐third of visits, including during admitting shifts. Sixty‐six percent of patients consider a physician's touch comforting, and 58% believe it to be healing.[8]

A randomized trial found that most patients preferred a sitting physician, and believed that practitioners who sat were more compassionate and spent more time with them.[9] Unfortunately, interns sat down with patients in fewer than 10% of encounters.

We do not know why interns do not engage in these simple behaviors, but it is not surprising given that their role models, including hospitalist physicians, do not practice them universally.[10] Personality differences, medical school experiences, and hospital factors such as patient volume and complexity may explain variability in performance.

Importantly, we know that habits learned in residency tend to be retained when physicians enter independent practice.[12] If we want attending physicians to practice etiquette‐based communication, then it must be role modeled, taught, and evaluated during residency by clinical educators and hospitalist physicians. The gap between intern perceptions and actual practice of these behaviors provides a window of opportunity for education and feedback in bedside communication. Attending physicians rate communication skills as 1 of the top values they seek to pass on to house officers.[13] Curricula on communication skills improve physician attitudes and beliefs about the importance of good communication as well as long‐term performance of communication skills.[14]

Our study had several limitations. First, all 732 patient encounters were assessed, regardless of whether the intern had seen the patient previously. This differed slightly from Kahn's assertion that these behaviors be performed at least on the first encounter with the patient. We believe that the need for common courtesy does not diminish after the first visit, and although certain behaviors may not be indicated on 100% of visits, our sensitivity analysis indicated performance of these behaviors was not likely even on the first visit of the day.

Second, our observations were limited to medicine interns at 2 programs in Baltimore during a single month, limiting generalizability. A convenience sample of interns was chosen for recruitment based on rotation on a general medicine rotation during the study month. We observed interns over the course of several shifts and throughout various positions in the call cycle.

Third, in any observational study, the Hawthorne effect is a potential limitation. We attempted to limit this bias by collecting information anonymously and not indicating to the interns which aspects of the patient encounter were being recorded.

Fourth, we defined the behaviors broadly in an attempt to measure the outcomes conservatively and maximize inter‐rater reliability. For instance, we did not differentiate in data collection between comforting touch and physical examination. Because chairs may not be readily available in all patient rooms, we included sitting on the patient's bed or crouching next to the bed as sitting with the patient. Use of open‐ended questions was observed as a more general form of Kahn's recommendation to ask how the patient is feeling.

Fifth, our poststudy survey was conducted 6 months after the observations were performed, used an ordinal rather than continuous response scale, and was limited to only 1 of the 2 programs and 9 of the 29 participants. Given this small sample size, generalizability of the results is limited. Additionally, intern practice of etiquette‐based communication may have improved between the observations and survey that took place 6 months later.

As hospital admissions are a time of vulnerability for patients, physicians can take a basic etiquette‐based communication approach to comfort patients and help them feel more secure. We found that even though interns believed they were practicing Kahn's recommended etiquette‐based communication, only a minority actually were. Curricula on communication styles or environmental changes, such as providing chairs in patient rooms or photographs identifying members of the medical team, may encourage performance of these behaviors.[15]

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, and Dr. Mary Catherine Beach, MD, MPH, who provided tremendous help in editing. The authors also thank Kevin Wang, whose assistance with observer hiring, training, and management was essential.

Disclosures: The Osler Center for Clinical Excellence at Johns Hopkins and the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund provided stipends for our observers as well as transportation and logistical costs of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Physician‐patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:25–38.

- , . Physicians' nonverbal rapport building and patients' talk about the subjective component of illness. Hum Commun Res. 2001;27:299–311.

- , , , , . Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–379.

- , , , . House staff nonverbal communication skills and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:170–174.

- . Etiquette‐based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1988–1989.

- , , . Patient satisfaction associated with correct identification of physician's photographs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:604–608.

- . Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–1433.

- , , , . Patients' attitudes to comforting touch in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2411–2416.

- , , , et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients' preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:489–497.

- , , , , . Appraising the practice of etiquette‐based medicine in the inpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):908–913.

- , , , , , . Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in‐hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:199–201.

- , , . The content of internal medicine residency training and its relevance to the practice of medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:304–308.

- , . Which values to attending physicians try to pass on to house officers? Med Educ. 2001;35:941–945.

- , , , , , . Relationship of resident characteristics, attitudes, prior training, and clinical knowledge to communication skills performance. Med Educ. 2006;40:18–25.

- , , , . PHACES (Photographs of academic clinicians and their educational status): a tool to improve delivery of family‐centered care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:138–145.

Patient‐centered communication may impact several aspects of the patientdoctor relationship including patient disclosure of illness‐related information, patient satisfaction, anxiety, and compliance with medical recommendations.[1, 2, 3, 4] Etiquette‐based medicine, a term coined by Kahn, involves simple patient‐centered communication strategies that convey professionalism and respect to patients.[5] Studies have confirmed that patients prefer physicians who practice etiquette‐based medicine behaviors, including sitting down and introducing one's self.[6, 7, 8, 9] Performance of etiquette‐based medicine is associated with higher Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores. However, these easy‐to‐practice behaviors may not be modeled commonly in the inpatient setting.[10] We sought to understand whether etiquette‐based communication behaviors are practiced by trainees on inpatient medicine rotations.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective study incorporating direct observation of intern interactions with patients during January 2012 at 2 internal medicine residency programs in Baltimore Maryland, Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC). We then surveyed participants from JHH in June 2012 to assess perceptions of their practice of etiquette‐based communication.

Participants and Setting

We observed a convenience sample of 29 internal medicine interns from the 2 institutions. We sought to observe interns over an equal number of hours at both sites and to sample shifts in proportion to the amount of time interns spend on each of these shifts. All interns who were asked to participate in the study agreed and comprised a total of 27% of the 108 interns in the 2 programs. The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine approved the study; the University of Maryland institutional review board deemed it not human subjects research. All observed interns provided informed consent to be observed during 1 to 4 inpatient shifts.

Observers

Twenty‐two undergraduate university students served as the observers for the study and were trained to collect data with the iPod Touch (Apple, Cupertino, CA) without interrupting patient care. We then tested the observers to ensure 85% concordance rate with the researchers in mock observation. Four hours of quality assurance were completed at both institutions during the study. Congruence between observer and research team member was >85% for each hour of observation.

Observation

Observers recorded intern activities on the iPod Touch spreadsheet application. The application allowed for real‐time data entry and direct export of results. The primary dependent variables for this study were 5 behaviors that were assessed each time an intern went into a patient's room. The 5 observed behaviors included (1) introducing one's self, (2) introducing one's role on the medical team, (3) touching the patient, (4) sitting down, and (5) asking the patient at least 1 open‐ended question. These behaviors were chosen for observation because they are central to Kahn's framework of etiquette‐based medicine, applicable to each inpatient encounter, and readily observed by trained nonmedical observers. These behaviors are defined in Table 1. Use of open‐ended questions was observed as a more general form of Kahn's recommendation to ask how the patient is feeling. Interns were not aware of which behaviors were being evaluated.

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Introduced self | Providing a name |

| Introduced role | Uses term doctor, resident, intern, or medical team |

| Sat down | Sitting on the bed, in a chair, or crouching if no chair was available during at least part of the encounter |

| Touched the patient | Any form of physical contact that occurred at least once during the encounter including shaking a patient's hand, touching a patient on the shoulder, or performing any part of the physical exam |

| Asked open‐ended question | Asked the patient any question that required more than a yes/no answer |

Each time an observed intern entered a patient room, the observer recorded whether or not each of the 5 behaviors was performed, coded as a dichotomous variable. Although data collection was anonymous, observers recorded the team, hospital site, gender of the intern, and whether the intern was admitting new patients during the shift.

Survey

Following the observational portion of the study, participants at JHH completed a cross‐sectional, anonymous survey that asked them to estimate how frequently they currently performed each of the behaviors observed in this study. Response options included the following categories: 20%, 20% to 40%, 40% to 60%, 60% to 80%, or 80% to 100%.

Data Analysis

We determined the percent of patient visits during which each behavior was performed. Data were analyzed using Student t and [2] tests evaluating differences by hospital, intern gender, type of shift, and time of day. To account for correlation within subjects and observers, we performed multilevel logistic regression analysis adjusted for clustering at the intern and observer levels. For the survey analysis, the mean of the response category was used as the basis for comparison. All quantitative analyses were performed in Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and Stata/IC version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 732 inpatient encounters were observed during 118 intern shifts. Interns were observed for a mean of 25 patient encounters each (range, 361; standard deviation [SD] 17). Overall, interns introduced themselves 40% of the time and stated their role 37% of the time (Table 2). Interns touched patients on 65% of visits, sat down with patients during 9% of visits, and asked open‐ended questions on 75% of visits. Interns performed all 5 of the behaviors during 4% of the total encounters. The percentage of the 5 behaviors performed by each intern during all observed visits ranged from 24% to 100%, with a mean of 51% (SD 17%) per intern.

| Total Encounters, N (%) | Introduced Self (%) | Introduced Role (%) | Touched Patient (%) | Sat Down (%) | Open‐Ended Question (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Overall | 732 | 40 | 37 | 65 | 9 | 75 |

| JHH | 373 (51) | 35ab | 29ab | 62a | 10 | 70a |

| UMMC | 359 (49) | 45 | 44 | 69 | 8 | 81 |

| Male | 284 (39) | 39 | 35 | 64 | 9 | 74 |

| Female | 448 (61) | 41 | 38 | 67 | 10 | 76 |

| Day shift | 551 (75) | 37a | 34a | 65 | 9 | 77 |

| Night shift | 181 (25) | 48 | 45 | 67 | 12 | 71 |

| Admitting shift | 377 (52) | 46a | 42a | 63 | 10 | 75 |

| Nonadmitting shift | 355 (48) | 34 | 30 | 69 | 9 | 76 |

During night shifts as compared to day shifts, interns were more likely to introduce themselves (48% vs 37%, P=0.01) and their role (45% vs 34%, P0.01). During shifts in which they admitted patients as compared to coverage shifts, interns were more likely to introduce themselves (46% vs 34%, P0.01) and their role (42% vs 30%, P0.01). Interns at UMMC as compared to JHH interns were more likely to introduce themselves (45% vs 35%, P0.01) and describe their role to patients (44% vs 29%, P0.01). Interns at UMMC were also more likely to ask open‐ended questions (81% vs 70%, P0.01) and to touch patients (69% vs 62%, P=0.04). Performance of these behaviors did not vary significantly by gender, time of day, or shift. After adjustment for clustering at the observer and intern levels, differences by institution persisted in the rate of introducing oneself and one's role.

We performed a sensitivity analysis examining the first patient encounters of the day, and found that interns were somewhat more likely to introduce themselves (50% vs 40%, P=0.03) but were not significantly more likely to introduce their role, sit down, ask open‐ended questions, or touch the patient.

Nine of the 10 interns at JHH who participated in the study completed the survey (response rate=90%). Interns estimated introducing themselves and their role and sitting with patients significantly more frequently than was observed (80% vs 40%, P0.01; 80% vs 37%, P0.01; and 58% vs 9%, P0.01, respectively) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The interns we observed in 2 urban academic internal medicine residency programs did not routinely practice etiquette‐based communication. Interns surveyed tended to overestimate their performance of these behaviors. These behaviors are simple to perform and are each associated with improved patient experiences of hospital care. Tackett et al. recently demonstrated that interns are not alone. Hospitalist physicians do not universally practice etiquette‐based medicine, even though these behaviors correlate with patient satisfaction scores.[10]

Introducing oneself to patients may improve patient satisfaction and acceptance of trainee involvement in care.[6] However, only 10% of hospitalized patients in 1 study correctly identified a physician on their inpatient team, demonstrating the need for introductions during each and every inpatient encounter.[11] The interns we observed introduced themselves to patients in only 40% of encounters. During admitting shifts, when the first encounter with a patient likely took place, interns introduced themselves during 46% of encounters.

A comforting touch has been shown to reduce anxiety levels among patients and improve compliance with treatment regimens, but the interns did not touch patients in one‐third of visits, including during admitting shifts. Sixty‐six percent of patients consider a physician's touch comforting, and 58% believe it to be healing.[8]

A randomized trial found that most patients preferred a sitting physician, and believed that practitioners who sat were more compassionate and spent more time with them.[9] Unfortunately, interns sat down with patients in fewer than 10% of encounters.

We do not know why interns do not engage in these simple behaviors, but it is not surprising given that their role models, including hospitalist physicians, do not practice them universally.[10] Personality differences, medical school experiences, and hospital factors such as patient volume and complexity may explain variability in performance.

Importantly, we know that habits learned in residency tend to be retained when physicians enter independent practice.[12] If we want attending physicians to practice etiquette‐based communication, then it must be role modeled, taught, and evaluated during residency by clinical educators and hospitalist physicians. The gap between intern perceptions and actual practice of these behaviors provides a window of opportunity for education and feedback in bedside communication. Attending physicians rate communication skills as 1 of the top values they seek to pass on to house officers.[13] Curricula on communication skills improve physician attitudes and beliefs about the importance of good communication as well as long‐term performance of communication skills.[14]

Our study had several limitations. First, all 732 patient encounters were assessed, regardless of whether the intern had seen the patient previously. This differed slightly from Kahn's assertion that these behaviors be performed at least on the first encounter with the patient. We believe that the need for common courtesy does not diminish after the first visit, and although certain behaviors may not be indicated on 100% of visits, our sensitivity analysis indicated performance of these behaviors was not likely even on the first visit of the day.

Second, our observations were limited to medicine interns at 2 programs in Baltimore during a single month, limiting generalizability. A convenience sample of interns was chosen for recruitment based on rotation on a general medicine rotation during the study month. We observed interns over the course of several shifts and throughout various positions in the call cycle.

Third, in any observational study, the Hawthorne effect is a potential limitation. We attempted to limit this bias by collecting information anonymously and not indicating to the interns which aspects of the patient encounter were being recorded.

Fourth, we defined the behaviors broadly in an attempt to measure the outcomes conservatively and maximize inter‐rater reliability. For instance, we did not differentiate in data collection between comforting touch and physical examination. Because chairs may not be readily available in all patient rooms, we included sitting on the patient's bed or crouching next to the bed as sitting with the patient. Use of open‐ended questions was observed as a more general form of Kahn's recommendation to ask how the patient is feeling.

Fifth, our poststudy survey was conducted 6 months after the observations were performed, used an ordinal rather than continuous response scale, and was limited to only 1 of the 2 programs and 9 of the 29 participants. Given this small sample size, generalizability of the results is limited. Additionally, intern practice of etiquette‐based communication may have improved between the observations and survey that took place 6 months later.

As hospital admissions are a time of vulnerability for patients, physicians can take a basic etiquette‐based communication approach to comfort patients and help them feel more secure. We found that even though interns believed they were practicing Kahn's recommended etiquette‐based communication, only a minority actually were. Curricula on communication styles or environmental changes, such as providing chairs in patient rooms or photographs identifying members of the medical team, may encourage performance of these behaviors.[15]

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, and Dr. Mary Catherine Beach, MD, MPH, who provided tremendous help in editing. The authors also thank Kevin Wang, whose assistance with observer hiring, training, and management was essential.

Disclosures: The Osler Center for Clinical Excellence at Johns Hopkins and the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund provided stipends for our observers as well as transportation and logistical costs of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Patient‐centered communication may impact several aspects of the patientdoctor relationship including patient disclosure of illness‐related information, patient satisfaction, anxiety, and compliance with medical recommendations.[1, 2, 3, 4] Etiquette‐based medicine, a term coined by Kahn, involves simple patient‐centered communication strategies that convey professionalism and respect to patients.[5] Studies have confirmed that patients prefer physicians who practice etiquette‐based medicine behaviors, including sitting down and introducing one's self.[6, 7, 8, 9] Performance of etiquette‐based medicine is associated with higher Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores. However, these easy‐to‐practice behaviors may not be modeled commonly in the inpatient setting.[10] We sought to understand whether etiquette‐based communication behaviors are practiced by trainees on inpatient medicine rotations.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective study incorporating direct observation of intern interactions with patients during January 2012 at 2 internal medicine residency programs in Baltimore Maryland, Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) and the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC). We then surveyed participants from JHH in June 2012 to assess perceptions of their practice of etiquette‐based communication.

Participants and Setting

We observed a convenience sample of 29 internal medicine interns from the 2 institutions. We sought to observe interns over an equal number of hours at both sites and to sample shifts in proportion to the amount of time interns spend on each of these shifts. All interns who were asked to participate in the study agreed and comprised a total of 27% of the 108 interns in the 2 programs. The institutional review board at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine approved the study; the University of Maryland institutional review board deemed it not human subjects research. All observed interns provided informed consent to be observed during 1 to 4 inpatient shifts.

Observers

Twenty‐two undergraduate university students served as the observers for the study and were trained to collect data with the iPod Touch (Apple, Cupertino, CA) without interrupting patient care. We then tested the observers to ensure 85% concordance rate with the researchers in mock observation. Four hours of quality assurance were completed at both institutions during the study. Congruence between observer and research team member was >85% for each hour of observation.

Observation

Observers recorded intern activities on the iPod Touch spreadsheet application. The application allowed for real‐time data entry and direct export of results. The primary dependent variables for this study were 5 behaviors that were assessed each time an intern went into a patient's room. The 5 observed behaviors included (1) introducing one's self, (2) introducing one's role on the medical team, (3) touching the patient, (4) sitting down, and (5) asking the patient at least 1 open‐ended question. These behaviors were chosen for observation because they are central to Kahn's framework of etiquette‐based medicine, applicable to each inpatient encounter, and readily observed by trained nonmedical observers. These behaviors are defined in Table 1. Use of open‐ended questions was observed as a more general form of Kahn's recommendation to ask how the patient is feeling. Interns were not aware of which behaviors were being evaluated.

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Introduced self | Providing a name |

| Introduced role | Uses term doctor, resident, intern, or medical team |

| Sat down | Sitting on the bed, in a chair, or crouching if no chair was available during at least part of the encounter |

| Touched the patient | Any form of physical contact that occurred at least once during the encounter including shaking a patient's hand, touching a patient on the shoulder, or performing any part of the physical exam |

| Asked open‐ended question | Asked the patient any question that required more than a yes/no answer |

Each time an observed intern entered a patient room, the observer recorded whether or not each of the 5 behaviors was performed, coded as a dichotomous variable. Although data collection was anonymous, observers recorded the team, hospital site, gender of the intern, and whether the intern was admitting new patients during the shift.

Survey

Following the observational portion of the study, participants at JHH completed a cross‐sectional, anonymous survey that asked them to estimate how frequently they currently performed each of the behaviors observed in this study. Response options included the following categories: 20%, 20% to 40%, 40% to 60%, 60% to 80%, or 80% to 100%.

Data Analysis

We determined the percent of patient visits during which each behavior was performed. Data were analyzed using Student t and [2] tests evaluating differences by hospital, intern gender, type of shift, and time of day. To account for correlation within subjects and observers, we performed multilevel logistic regression analysis adjusted for clustering at the intern and observer levels. For the survey analysis, the mean of the response category was used as the basis for comparison. All quantitative analyses were performed in Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and Stata/IC version 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 732 inpatient encounters were observed during 118 intern shifts. Interns were observed for a mean of 25 patient encounters each (range, 361; standard deviation [SD] 17). Overall, interns introduced themselves 40% of the time and stated their role 37% of the time (Table 2). Interns touched patients on 65% of visits, sat down with patients during 9% of visits, and asked open‐ended questions on 75% of visits. Interns performed all 5 of the behaviors during 4% of the total encounters. The percentage of the 5 behaviors performed by each intern during all observed visits ranged from 24% to 100%, with a mean of 51% (SD 17%) per intern.

| Total Encounters, N (%) | Introduced Self (%) | Introduced Role (%) | Touched Patient (%) | Sat Down (%) | Open‐Ended Question (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Overall | 732 | 40 | 37 | 65 | 9 | 75 |

| JHH | 373 (51) | 35ab | 29ab | 62a | 10 | 70a |

| UMMC | 359 (49) | 45 | 44 | 69 | 8 | 81 |

| Male | 284 (39) | 39 | 35 | 64 | 9 | 74 |

| Female | 448 (61) | 41 | 38 | 67 | 10 | 76 |

| Day shift | 551 (75) | 37a | 34a | 65 | 9 | 77 |

| Night shift | 181 (25) | 48 | 45 | 67 | 12 | 71 |

| Admitting shift | 377 (52) | 46a | 42a | 63 | 10 | 75 |

| Nonadmitting shift | 355 (48) | 34 | 30 | 69 | 9 | 76 |

During night shifts as compared to day shifts, interns were more likely to introduce themselves (48% vs 37%, P=0.01) and their role (45% vs 34%, P0.01). During shifts in which they admitted patients as compared to coverage shifts, interns were more likely to introduce themselves (46% vs 34%, P0.01) and their role (42% vs 30%, P0.01). Interns at UMMC as compared to JHH interns were more likely to introduce themselves (45% vs 35%, P0.01) and describe their role to patients (44% vs 29%, P0.01). Interns at UMMC were also more likely to ask open‐ended questions (81% vs 70%, P0.01) and to touch patients (69% vs 62%, P=0.04). Performance of these behaviors did not vary significantly by gender, time of day, or shift. After adjustment for clustering at the observer and intern levels, differences by institution persisted in the rate of introducing oneself and one's role.

We performed a sensitivity analysis examining the first patient encounters of the day, and found that interns were somewhat more likely to introduce themselves (50% vs 40%, P=0.03) but were not significantly more likely to introduce their role, sit down, ask open‐ended questions, or touch the patient.

Nine of the 10 interns at JHH who participated in the study completed the survey (response rate=90%). Interns estimated introducing themselves and their role and sitting with patients significantly more frequently than was observed (80% vs 40%, P0.01; 80% vs 37%, P0.01; and 58% vs 9%, P0.01, respectively) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

The interns we observed in 2 urban academic internal medicine residency programs did not routinely practice etiquette‐based communication. Interns surveyed tended to overestimate their performance of these behaviors. These behaviors are simple to perform and are each associated with improved patient experiences of hospital care. Tackett et al. recently demonstrated that interns are not alone. Hospitalist physicians do not universally practice etiquette‐based medicine, even though these behaviors correlate with patient satisfaction scores.[10]

Introducing oneself to patients may improve patient satisfaction and acceptance of trainee involvement in care.[6] However, only 10% of hospitalized patients in 1 study correctly identified a physician on their inpatient team, demonstrating the need for introductions during each and every inpatient encounter.[11] The interns we observed introduced themselves to patients in only 40% of encounters. During admitting shifts, when the first encounter with a patient likely took place, interns introduced themselves during 46% of encounters.

A comforting touch has been shown to reduce anxiety levels among patients and improve compliance with treatment regimens, but the interns did not touch patients in one‐third of visits, including during admitting shifts. Sixty‐six percent of patients consider a physician's touch comforting, and 58% believe it to be healing.[8]

A randomized trial found that most patients preferred a sitting physician, and believed that practitioners who sat were more compassionate and spent more time with them.[9] Unfortunately, interns sat down with patients in fewer than 10% of encounters.

We do not know why interns do not engage in these simple behaviors, but it is not surprising given that their role models, including hospitalist physicians, do not practice them universally.[10] Personality differences, medical school experiences, and hospital factors such as patient volume and complexity may explain variability in performance.

Importantly, we know that habits learned in residency tend to be retained when physicians enter independent practice.[12] If we want attending physicians to practice etiquette‐based communication, then it must be role modeled, taught, and evaluated during residency by clinical educators and hospitalist physicians. The gap between intern perceptions and actual practice of these behaviors provides a window of opportunity for education and feedback in bedside communication. Attending physicians rate communication skills as 1 of the top values they seek to pass on to house officers.[13] Curricula on communication skills improve physician attitudes and beliefs about the importance of good communication as well as long‐term performance of communication skills.[14]

Our study had several limitations. First, all 732 patient encounters were assessed, regardless of whether the intern had seen the patient previously. This differed slightly from Kahn's assertion that these behaviors be performed at least on the first encounter with the patient. We believe that the need for common courtesy does not diminish after the first visit, and although certain behaviors may not be indicated on 100% of visits, our sensitivity analysis indicated performance of these behaviors was not likely even on the first visit of the day.

Second, our observations were limited to medicine interns at 2 programs in Baltimore during a single month, limiting generalizability. A convenience sample of interns was chosen for recruitment based on rotation on a general medicine rotation during the study month. We observed interns over the course of several shifts and throughout various positions in the call cycle.

Third, in any observational study, the Hawthorne effect is a potential limitation. We attempted to limit this bias by collecting information anonymously and not indicating to the interns which aspects of the patient encounter were being recorded.

Fourth, we defined the behaviors broadly in an attempt to measure the outcomes conservatively and maximize inter‐rater reliability. For instance, we did not differentiate in data collection between comforting touch and physical examination. Because chairs may not be readily available in all patient rooms, we included sitting on the patient's bed or crouching next to the bed as sitting with the patient. Use of open‐ended questions was observed as a more general form of Kahn's recommendation to ask how the patient is feeling.

Fifth, our poststudy survey was conducted 6 months after the observations were performed, used an ordinal rather than continuous response scale, and was limited to only 1 of the 2 programs and 9 of the 29 participants. Given this small sample size, generalizability of the results is limited. Additionally, intern practice of etiquette‐based communication may have improved between the observations and survey that took place 6 months later.

As hospital admissions are a time of vulnerability for patients, physicians can take a basic etiquette‐based communication approach to comfort patients and help them feel more secure. We found that even though interns believed they were practicing Kahn's recommended etiquette‐based communication, only a minority actually were. Curricula on communication styles or environmental changes, such as providing chairs in patient rooms or photographs identifying members of the medical team, may encourage performance of these behaviors.[15]

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH, and Dr. Mary Catherine Beach, MD, MPH, who provided tremendous help in editing. The authors also thank Kevin Wang, whose assistance with observer hiring, training, and management was essential.

Disclosures: The Osler Center for Clinical Excellence at Johns Hopkins and the Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund provided stipends for our observers as well as transportation and logistical costs of the study. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Physician‐patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:25–38.

- , . Physicians' nonverbal rapport building and patients' talk about the subjective component of illness. Hum Commun Res. 2001;27:299–311.

- , , , , . Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–379.

- , , , . House staff nonverbal communication skills and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:170–174.

- . Etiquette‐based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1988–1989.

- , , . Patient satisfaction associated with correct identification of physician's photographs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:604–608.

- . Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–1433.

- , , , . Patients' attitudes to comforting touch in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2411–2416.

- , , , et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients' preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:489–497.

- , , , , . Appraising the practice of etiquette‐based medicine in the inpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):908–913.

- , , , , , . Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in‐hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:199–201.

- , , . The content of internal medicine residency training and its relevance to the practice of medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:304–308.

- , . Which values to attending physicians try to pass on to house officers? Med Educ. 2001;35:941–945.

- , , , , , . Relationship of resident characteristics, attitudes, prior training, and clinical knowledge to communication skills performance. Med Educ. 2006;40:18–25.

- , , , . PHACES (Photographs of academic clinicians and their educational status): a tool to improve delivery of family‐centered care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:138–145.

- , , . Physician‐patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:25–38.

- , . Physicians' nonverbal rapport building and patients' talk about the subjective component of illness. Hum Commun Res. 2001;27:299–311.

- , , , , . Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–379.

- , , , . House staff nonverbal communication skills and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:170–174.

- . Etiquette‐based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1988–1989.

- , , . Patient satisfaction associated with correct identification of physician's photographs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:604–608.

- . Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152:1423–1433.

- , , , . Patients' attitudes to comforting touch in family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2000;46:2411–2416.

- , , , et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients' preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:489–497.

- , , , , . Appraising the practice of etiquette‐based medicine in the inpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):908–913.

- , , , , , . Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in‐hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:199–201.

- , , . The content of internal medicine residency training and its relevance to the practice of medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:304–308.

- , . Which values to attending physicians try to pass on to house officers? Med Educ. 2001;35:941–945.

- , , , , , . Relationship of resident characteristics, attitudes, prior training, and clinical knowledge to communication skills performance. Med Educ. 2006;40:18–25.

- , , , . PHACES (Photographs of academic clinicians and their educational status): a tool to improve delivery of family‐centered care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:138–145.