User login

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

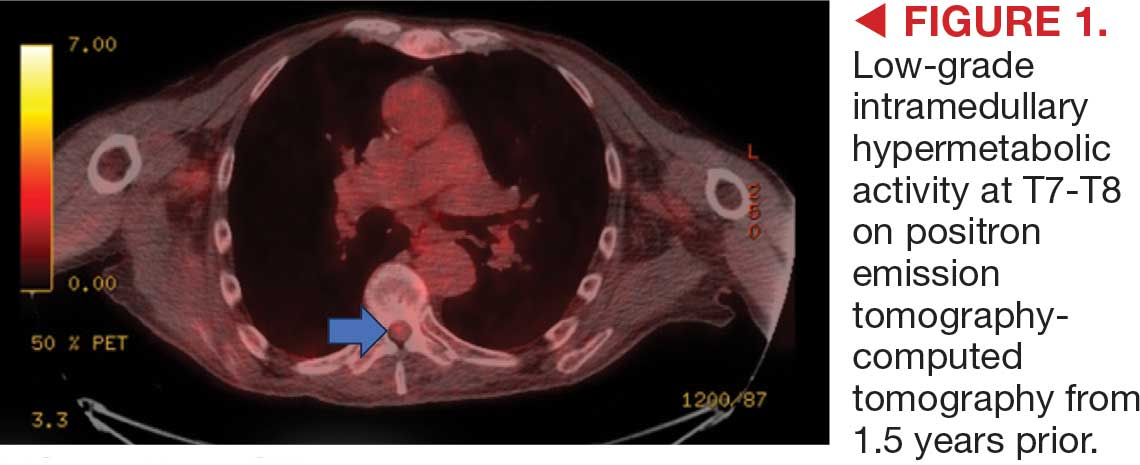

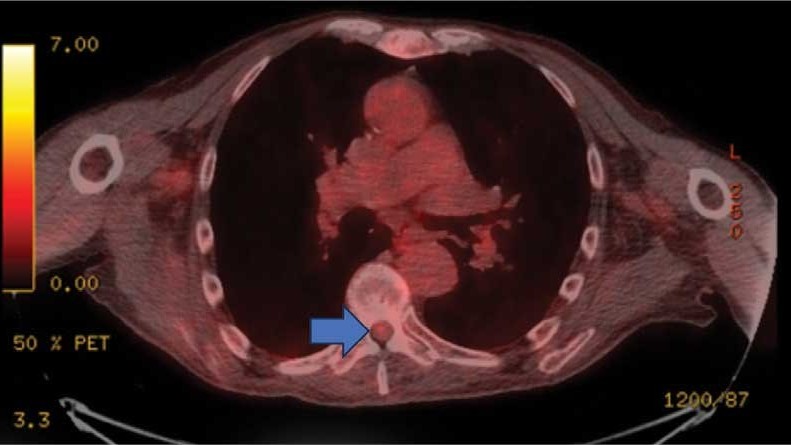

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

An 87-year-old man presented to the emergency department reporting a 1-month history of right lower extremity weakness, progressing to an inability to ambulate. The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low-grade right urothelial carcinoma status postbiopsy 2 years earlier, and atrial fibrillation following cardioversion 6 years earlier without anticoagulation therapy. He also reported severe right groin pain and increasing urinary obstruction.

On admission, neurology evaluated the patient’s lower extremity strength as 5/5 on his left, 1/5 on his right hip, and 2/5 on his right knee, with hypoesthesia of his right lower extremity. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated moderate to severe right-sided hydronephrosis, possibly due to a proximal right ureteric mass; no evidence of systemic metastases was found. He underwent a gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, which showed a mass at T7-T8, a mass effect in the central cord, and abnormal spinal cord enhancement from T7 through the conus medullaris. A review of fluorodeoxyglucose- 18 (FDG-18) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging from 1.5 years prior showed a low-grade focus (Figures 1-3). A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI did not demonstrate any intracranial metastatic disease, acute infarct, hemorrhage, mass effect, or extra-axial fluid collections.