User login

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

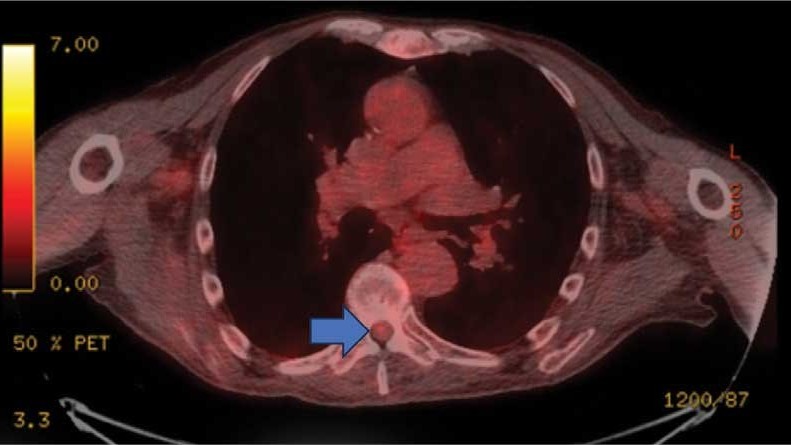

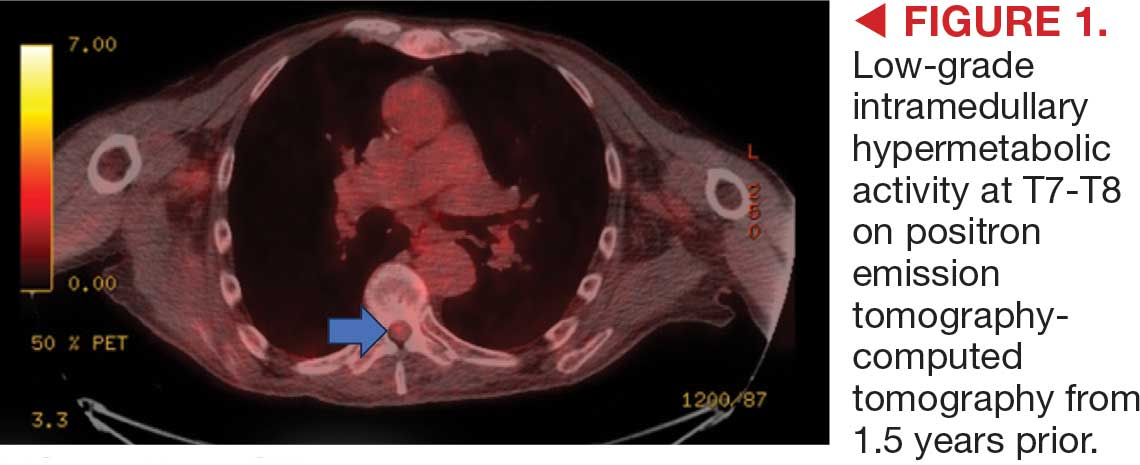

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

Discussion

A diagnosis of dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF) was made. Lesions involving the spinal cord are traditionally classified by location as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Intramedullary spinal cord abnormalities pose considerable diagnostic and management challenges because of the risks of biopsy in this location and the added potential for morbidity and mortality from improperly treated lesions. Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality, PET/CT and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may also help narrow the differential diagnosis and potentially avoid complications from an invasive biopsy.1 This patient’s intramedullary lesion, which represented a dAVF, posed a diagnostic challenge; after diagnosis, it was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy.

Intradural tumors account for 2% to 4% of all primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors.2 Ependymomas account for 50% to 60% of intramedullary tumors in adults, while astrocytomas account for about 60% of all lesions in children and adolescents.3,4 The differential diagnosis for intramedullary tumors also includes hemangioblastoma, metastases, primary CNS lymphoma, germ cell tumors, and gangliogliomas.5,6

Intramedullary metastases remain rare, although the incidence is rising with improvements in oncologic and supportive treatments. Autopsy studies conducted decades ago demonstrated that about 0.9% to 2.1% of patients with systemic cancer have intramedullary metastases at death.7,8 In patients with an established history of malignancy, a metastatic intramedullary tumor should be placed higher on the differential diagnosis. Intramedullary metastases most often occur in the setting of widespread metastatic disease. A systematic review of the literature on patients with lung cancer (small cell and non-small cell lung carcinomas) and ≥ 1 intramedullary spinal cord metastasis demonstrated that 55.8% of patients had concurrent brain metastases, 20.0% had leptomeningeal carcinomatosis, and 19.5% had vertebral metastases.9 While about half of all intramedullary metastases are associated with lung cancer, other common malignancies that metastasize to this area include colorectal, breast, and renal cell carcinoma, as well as lymphoma and melanoma primaries.10,11

On imaging, intramedullary metastases often appear as several short, studded segments with surrounding edema, typically out of proportion to the size of the lesion.1 By contrast, astrocytomas and ependymomas often span multiple segments, and enhancement patterns can vary depending on the subtype and grade. Glioblastoma multiforme, or grade 4 IDH wild-type astrocytomas, demonstrate an irregular, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement. Hemangioblastomas vary in size and are classically hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted sequences, isointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, and demonstrate avid enhancement on T1- postcontrast images. In large hemangioblastomas, flow voids due to prominent vasculature may be visualized.

Numerous nonneoplastic tumor mimics can obscure the differential diagnosis. Vascular malformations, including cavernomas and dAVFs, can also present with enhancement and edema. dAVFs are the most common type of spinal vascular malformation, accounting for about 70% of cases.12 They are supplied by the radiculomeningeal arteries, whereas pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are supplied by the radiculomedullary and radiculopial arteries. On MRI, dAVFs usually have venous congestion with intramedullary edema, which appears as an ill-defined centromedullary hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging over multiple segments. The spinal cord may appear swollen with atrophic changes in chronic cases. Spinal cord AVMs are rarer and have an intramedullary nidus. They usually demonstrate mixed heterogeneous signal on T1- and T2-weighted imaging due to blood products, while the nidus demonstrates a variable degree of enhancement. Serpiginous flow voids are seen both within the nidus and at the cord surface.

Demyelinating lesions of the spine may be seen in neuroinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, acute transverse myelitis, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. In multiple sclerosis, lesions typically extend ≤ 2 vertebral segments in length, cover less than half of the vertebral cross-sectional area, and have a dorsolateral predilection.13 Active lesions may demonstrate enhancement along the rim or in a patchy pattern. In the presence of demyelinating lesions, there may occasionally appear to be an expansile mass with a syrinx.14

Infections such as tuberculosis and neurosarcoidosis should also remain on the differential diagnosis. On MRI, tuberculosis usually involves the thoracic cord and is typically rim-enhancing.15 If there are caseating granulomas, T2-weighted images may also demonstrate rim enhancement.16 Spinal sarcoidosis is unusual without intracranial involvement, and its appearance may include leptomeningeal enhancement, cord expansion, and hyperintense signal on T2- weighted imaging.17

Finally, iatrogenic causes are also possible, including radiation myelopathy and mechanical spinal cord injury. For radiation myelopathy, it is important to ascertain whether a patient has undergone prior radiotherapy in the region and to obtain the pertinent dosimetry. Spinal cord injury may cause a focal signal abnormality within the cord, with T2 hyperintensity; these foci may or may not present with enhancement, edema, or hematoma and therefore may resemble tumors.13

This patient presented with progressive right-sided lower extremity weakness and hypoesthesia and a history of a low-grade right renal/pelvic ureteral tumor. The immediate impression was that the thoracic intramedullary lesion represented a metastatic lesion. However, in the absence of any systemic or intracranial metastases, this progression was much less likely. An extensive interdisciplinary workup was conducted that included medical oncology, neurology, neuroradiology, neuro-oncology, neurosurgery, nuclear medicine, and radiation oncology. Neuroradiology and nuclear medicine identified a slightly hypermetabolic focus on the PET/CT from 1.5 years prior that correlated exactly with the same location as the lesion on the recent spinal MRI. This finding, along with the MRA, confirmed the diagnosis of a dAVF, which was successfully managed conservatively with dexamethasone and physical therapy, rather than through oncologic treatments such as radiotherapy

There remains debate regarding the utility of steroids in treating patients with dAVF. Although there are some case reports documenting that the edema associated with the dAVF responds to steroids, other case series have found that steroids may worsen outcomes in patients with dAVF, possibly due to increased venous hydrostatic pressure.

This case demonstrates the importance of an interdisciplinary workup when evaluating an intramedullary lesion, as well as maintaining a wide differential diagnosis, particularly in the absence of a history of polymetastatic cancer. All the clues (such as the slightly hypermetabolic focus on a PET/CT from 1.5 years prior) need to be obtained to comfortably reach a diagnosis in the absence of pathologic confirmation. These cases can be especially challenging due to the lack of pathologic confirmation, but by understanding the main differentiating features among the various etiologies and obtaining all available information, a correct diagnosis can be made without unnecessary interventions.

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

- Moghaddam SM, Bhatt AA. Location, length, and enhancement: systematic approach to differentiating intramedullary spinal cord lesions. Insights Imaging. 2018;9:511-526. doi:10.1007/s13244-018-0608-3

- Grimm S, Chamberlain MC. Adult primary spinal cord tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:1487-1495. doi:10.1586/ern.09.101

- Miller DJ, McCutcheon IE. Hemangioblastomas and other uncommon intramedullary tumors. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:253- 270. doi:10.1023/a:1006403500801

- Mottl H, Koutecky J. Treatment of spinal cord tumors in children. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:293-295.

- Kandemirli SG, Reddy A, Hitchon P, et al. Intramedullary tumours and tumour mimics. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:876.e17-876. e32. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2020.05.010

- Tobin MK, Geraghty JR, Engelhard HH, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a review of current and future treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E14. doi:10.3171/2015.5.FOCUS15158

- Chason JL, Walker FB, Landers JW. Metastatic carcinoma in the central nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. A prospective autopsy study. Cancer. 1963;16:781-787.

- Costigan DA, Winkelman MD. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. A clinicopathological study of 13 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:227-233.

- Wu L, Wang L, Yang J, et al. Clinical features, treatments, and prognosis of intramedullary spinal cord metastases from lung cancer: a case series and systematic review. Neurospine. 2022;19:65-76. doi:10.14245/ns.2142910.455

- Lv J, Liu B, Quan X, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis in malignancies: an institutional analysis and review. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:4741-4753. doi:10.2147/OTT.S193235

- Goyal A, Yolcu Y, Kerezoudis P, et al. Intramedullary spinal cord metastases: an institutional review of survival and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2019;142:347-354. doi:10.1007/s11060-019-03105-2

- Krings T. Vascular malformations of the spine and spinal cord: anatomy, classification, treatment. Clin Neuroradiol. 2010;20:5-24. doi:10.1007/s00062-010-9036-6

- Maj E, Wojtowicz K, Aleksandra PP, et al. Intramedullary spinal tumor-like lesions. Acta Radiol. 2019;60:994-1010. doi:10.1177/0284185118809540

- Waziri A, Vonsattel JP, Kaiser MG, et al. Expansile, enhancing cervical cord lesion with an associated syrinx secondary to demyelination. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:52-56. doi:10.3171/spi.2007.6.1.52

- Nussbaum ES, Rockswold GL, Bergman TA, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: a diagnostic and management challenge. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:243-247. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0243

- Lu M. Imaging diagnosis of spinal intramedullary tuberculoma: case reports and literature review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2010;33:159-162. doi:10.1080/10790268.2010.11689691

- Do-Dai DD, Brooks MK, Goldkamp A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of intramedullary spinal cord lesions: a pictorial review. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2010;39:160-185. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2009.05.004

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

Thoracic Intramedullary Mass Causing Neurologic Weakness

An 87-year-old man presented to the emergency department reporting a 1-month history of right lower extremity weakness, progressing to an inability to ambulate. The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, low-grade right urothelial carcinoma status postbiopsy 2 years earlier, and atrial fibrillation following cardioversion 6 years earlier without anticoagulation therapy. He also reported severe right groin pain and increasing urinary obstruction.

On admission, neurology evaluated the patient’s lower extremity strength as 5/5 on his left, 1/5 on his right hip, and 2/5 on his right knee, with hypoesthesia of his right lower extremity. Computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated moderate to severe right-sided hydronephrosis, possibly due to a proximal right ureteric mass; no evidence of systemic metastases was found. He underwent a gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine, which showed a mass at T7-T8, a mass effect in the central cord, and abnormal spinal cord enhancement from T7 through the conus medullaris. A review of fluorodeoxyglucose- 18 (FDG-18) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging from 1.5 years prior showed a low-grade focus (Figures 1-3). A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI did not demonstrate any intracranial metastatic disease, acute infarct, hemorrhage, mass effect, or extra-axial fluid collections.

Radiation and Medical Oncology Perspectives on Oligometastatic Disease Treatment

Radiation and Medical Oncology Perspectives on Oligometastatic Disease Treatment

The treatment of metastatic solid tumors has been based historically on systemic therapies, with the goal of delaying progression and extend life as long as possible, with tolerable treatment-related adverse events. Some exceptions were made for local treatment with surgery or radiotherapy (RT), often for patients with a single metastasis. A 1939 report describes a patient with renal adenocarcinoma and a solitary lung metastasis who underwent RT to the lung lesion after nephrectomy and subsequently partial lobectomy after the metastatic lesion progressed. The authors argued that if a metastasis appears solitary and accessible, it is plausible to remove it in addition to the primary growth.1

In 1995 Hellman and Weichselbaum proposed oligometastatic disease (OMD). They reasoned that malignancy exists along a spectrum from localized disease to widely disseminated disease, with OMD existing in between with a still-restricted tumor metastatic capacity. Appropriately selected patients with OMD may be candidates for prolonged disease-free survival or cure with the addition of local therapy to systemic therapy.2

The EORTC 4004 phase 2 randomized control trial (RCT) analyzed radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for colorectal liver metastases with systemic therapy vs systemic therapy alone for patients with ≤ 9 liver lesions.3 Systemic therapyconsisted of 5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin, with bevacizumab added to the regimen 3.5 years into the study, per updated standard- of-care. This trial was the first to demonstrate the benefit of aggressive local treatment vs system treatment alone for OMD with a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit (16.8 vs 9.9 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P = .03) and overall survival (OS) benefit (45.3 vs 40.5 months; HR, 0.74; P = .02) with the addition of local treatment with RFA.

Since the presentations of the SABR-COMET phase 2 RCT and another study by Gomez et al at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) 2018 annual meeting, the paradigm for offering local RT for OMD has rapidly evolved. Both studies found PFS and OS benefits of RT for patients with OMD.4,5 Additional RCTs have since demonstrated that for properly selected patients with OMD, aggressive local RT improved PFS and OS.6-9 These small studies have led to larger RCTs to better understand who benefits from local consolidative treatment, particularly RT.10,11

There is a large degree of heterogeneity in how oncologists define and approach OMD treatment. The 2020 European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) and ASTRO consensus guidelines defined the OMD state as 1 to 5 metastatic lesions for which all metastatic sites are safely treatable.12 The purpose of this study was to evaluate perceptions and practice patterns among radiation oncologists and medical oncologists regarding the use of local RT for OMD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Methods

A 12-question survey was developed by the VHA Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force using the ESTRO-ASTRO consensus guidelines to define OMD. The survey was emailed to the VHA radiation oncology and medical oncology listservs on August 1, 2023. These listservs consist of physicians in these specialties either directly employed by the VHA or serve in its facilities as contractors. The original response closure date was August 11, 2023, but it was extended to August 18, 2023, to increase responses. No incentives were offered to respondents. Two email reminders were sent to the medical oncology listserv and 3 to the radiation oncology listserv. Descriptive statistics and X2 tests were used for data analysis. The impact of specialty and presence of an on-site department of radiation oncology were reviewed. This project was approved by the VHA National Oncology Program and National Radiation Oncology Program.

Results

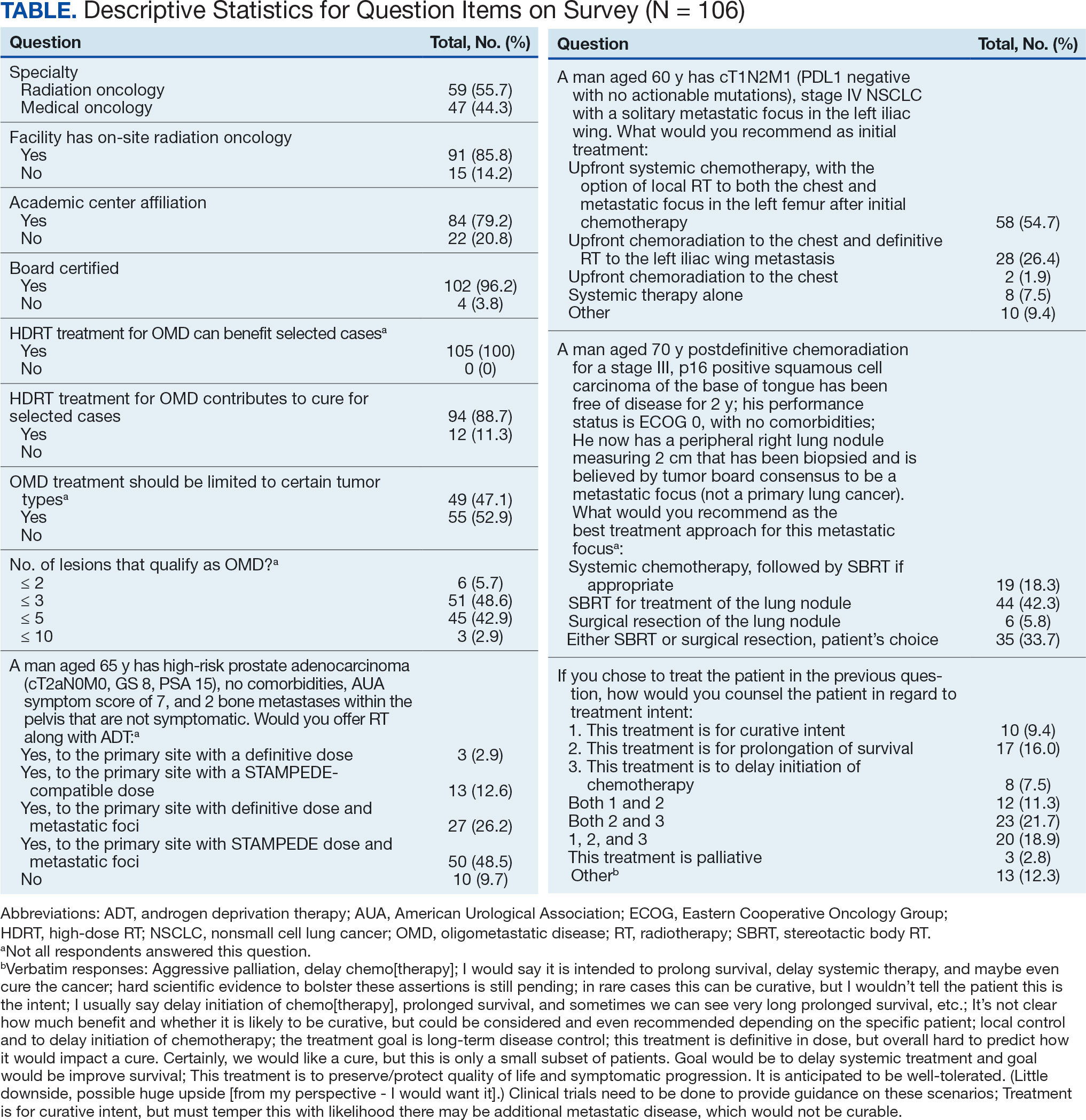

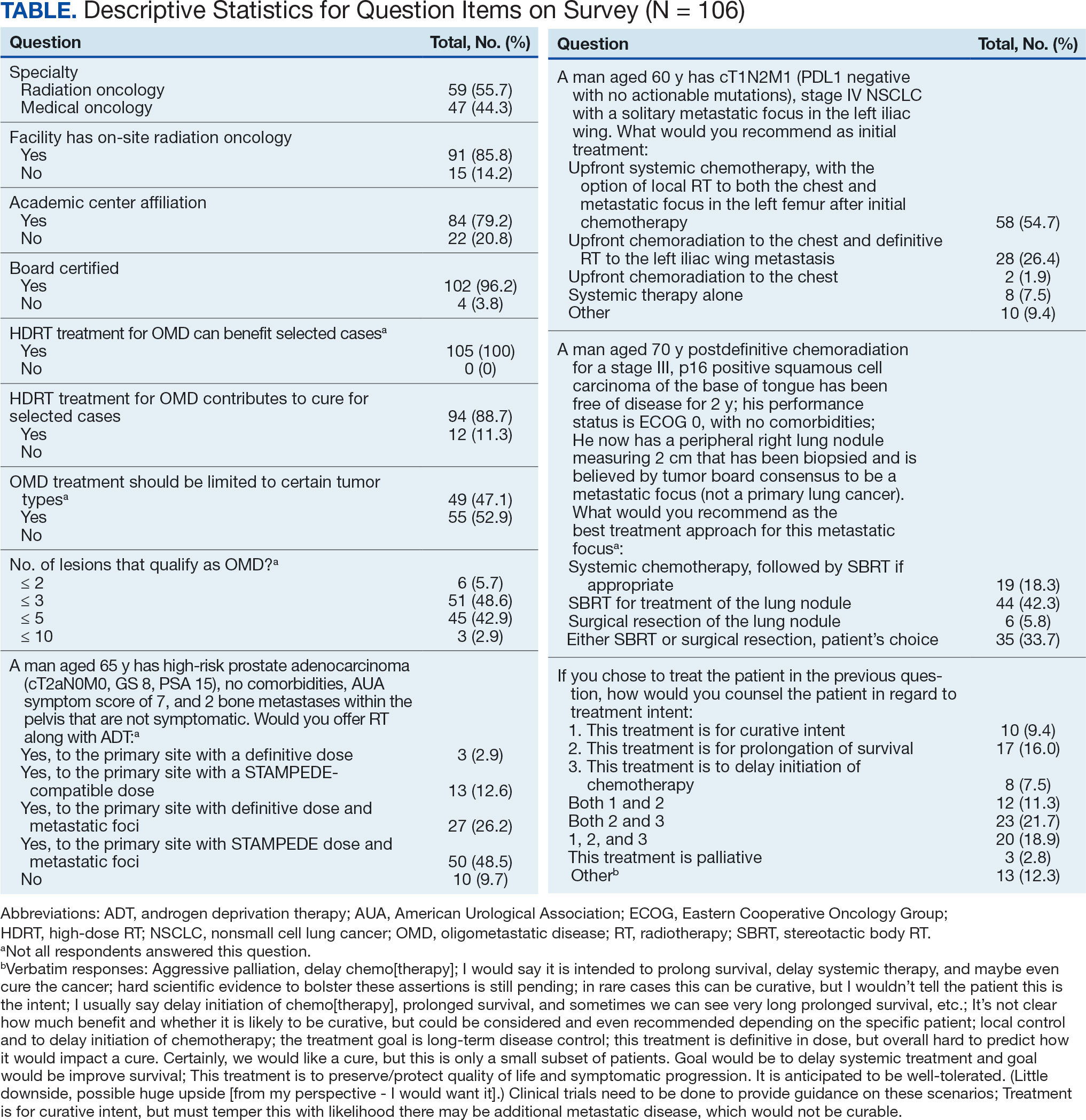

The survey was sent to 125 radiation oncologists and 515 medical oncologists and 106 were completed for a 16.6% response rate. There were 59 (55.7%) radiation oncologist responses and 47 (44.3%) medical oncologist responses. Most (96.2%) respondents were board-certified, and 84 (79.2%) were affiliated with an academic center. Not every respondent answered every question (Table).

All respondents (n = 105) indicated there is a potential benefit of high-dose RT for appropriately selected cases. Ninety-four oncologists (88.7%) believed that RT for OMD contributes to cure (88.1% of radiation oncologists, 89.4% of medical oncologists; P = .84) for appropriately selected cases. Some respondents who did not believe RT for OMD contributes to cure added comments about other perceived benefits, such as local disease control for palliation, delaying systemic therapy with its associated toxicities, and prolongation of disease-free survival or OS. A higher percentage of respondents with academic affiliations believed high-dose RT contributes to cure, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1).

Fifty-five respondents (51.9%; 55.2% radiation oncologists vs 50.0% medical oncologists; P = .60) responded that local RT for OMD treatment should not be limited by primary tumor type. Of respondents who responded that OMD treatment should be limited based on the type of primary tumor, many provided comments that argued there was a benefit for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate adenocarcinoma (PCa), and colorectal cancer.

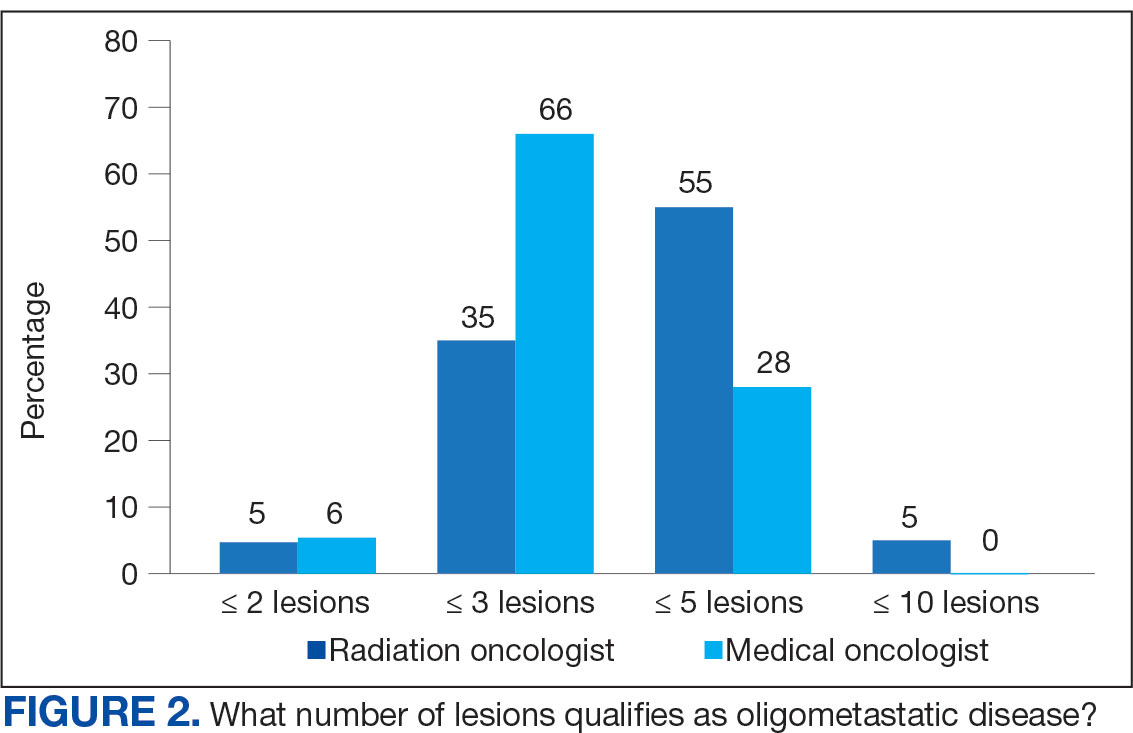

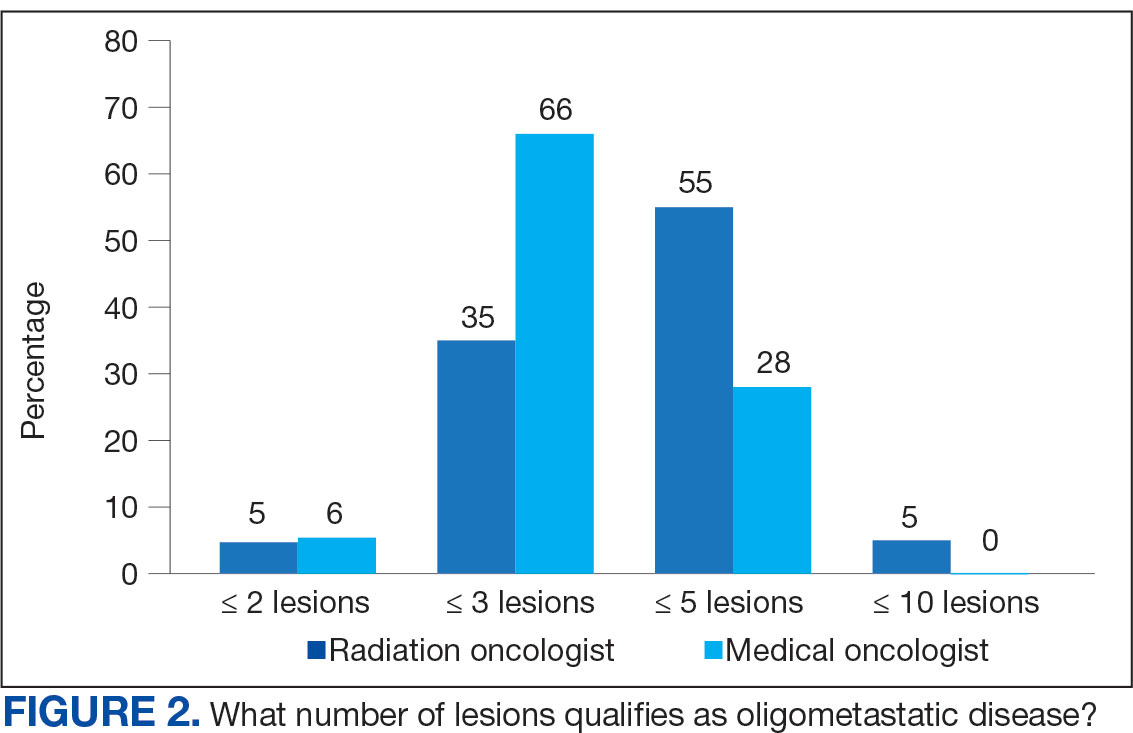

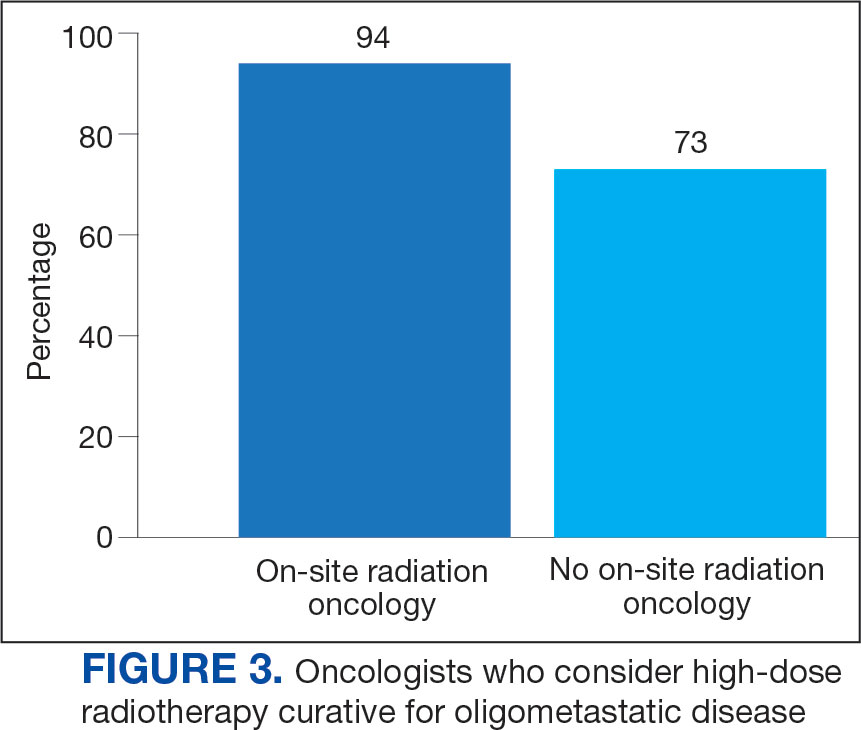

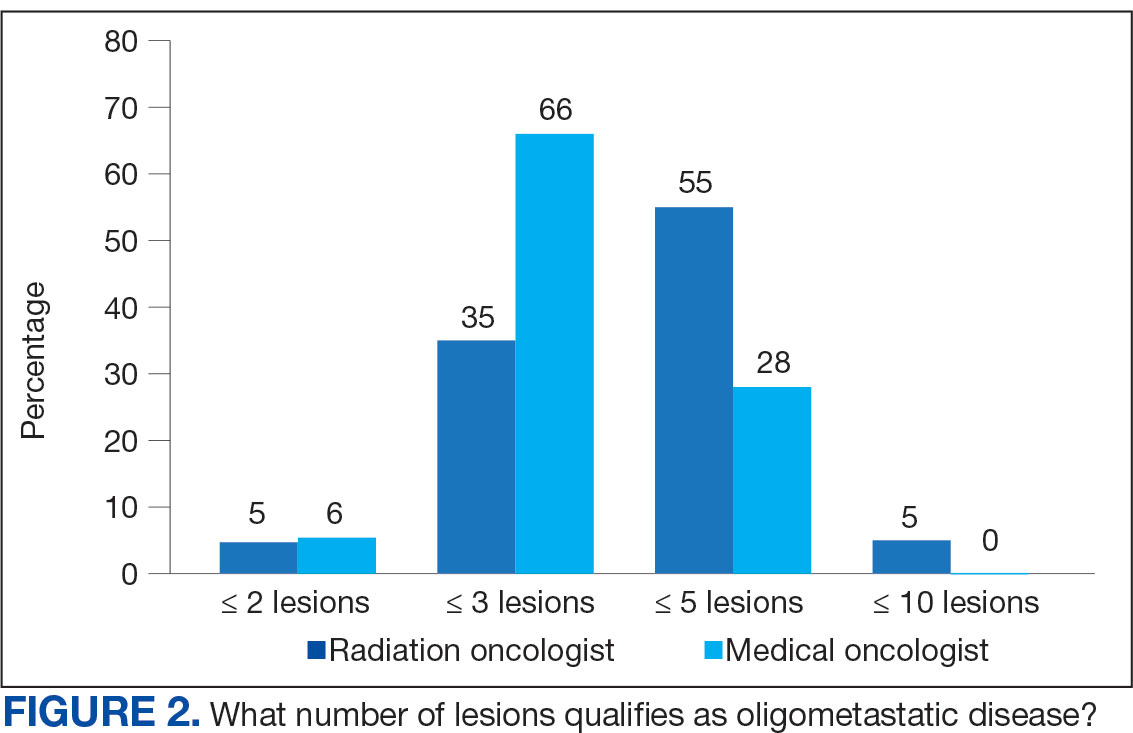

The definition of how many metastatic lesions qualify as OMD varied. A total of 48.6% of respondents defined OMD as ≤ 3 lesions and 42.9% answered ≤ 5 lesions. A majority of radiation oncologists (55.2%) classified ≤ 5 lesions as OMD, whereas a majority of medical oncologists (66.0%) considered ≤ 3 lesions as OMD (P = .006) (Figure 2).

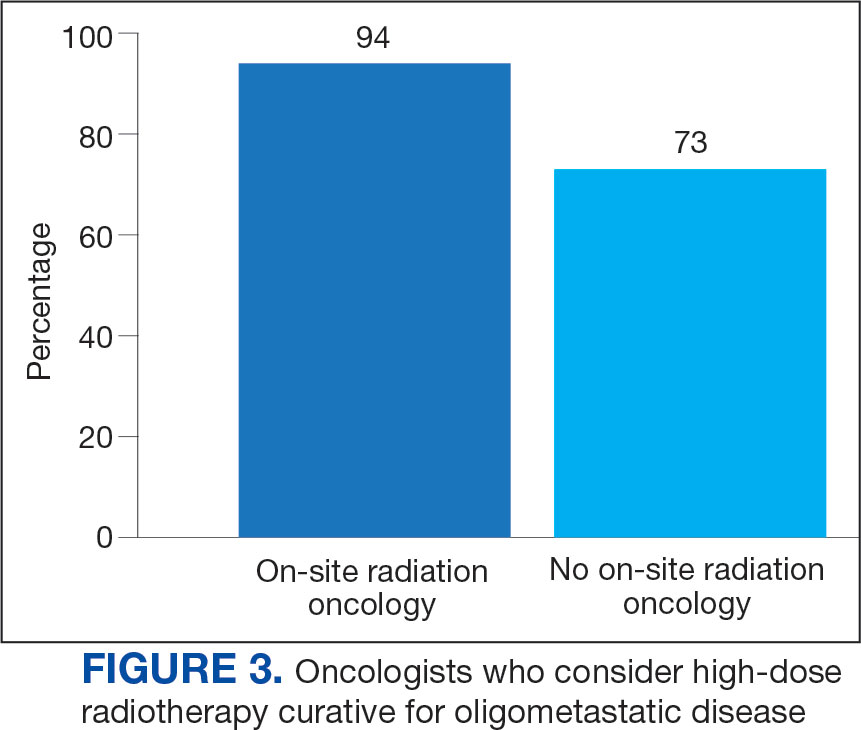

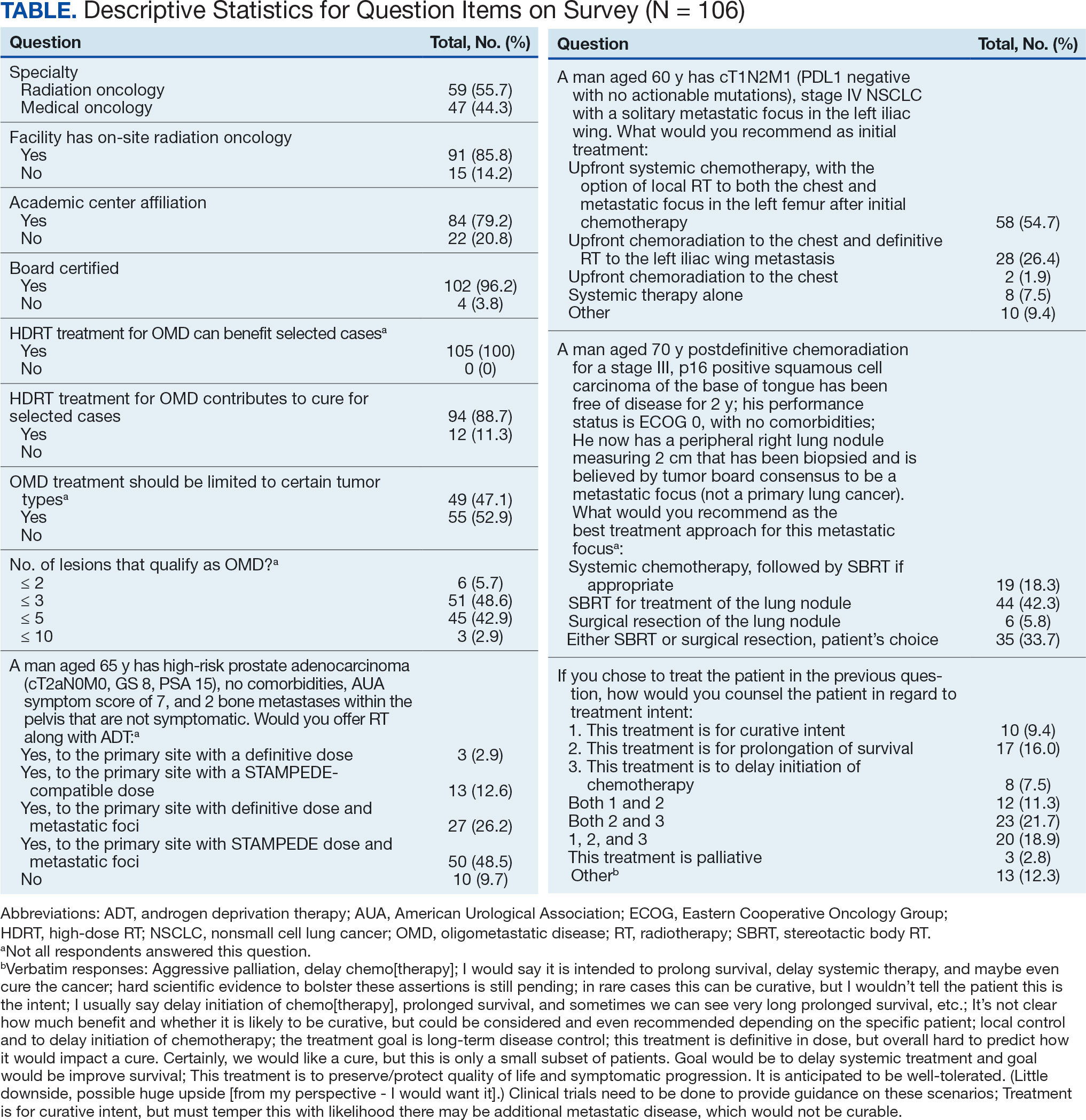

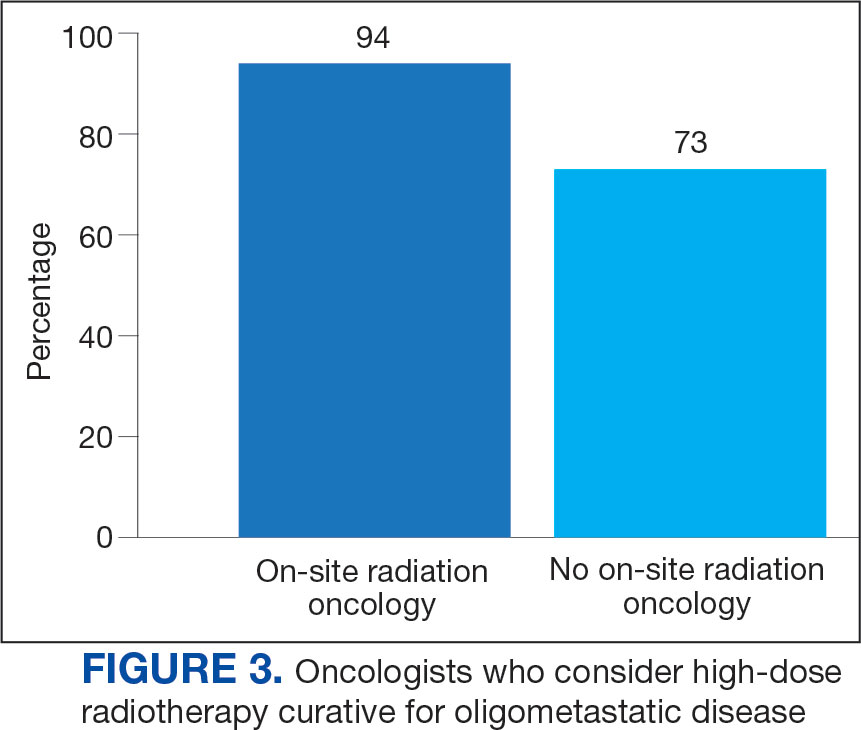

Thirty-six medical oncologists (76.6%) report having an on-site department of radiation oncology (Figure 3). This subgroup was more likely to consider local RT potentially curative compared with their medical oncology peers without on-site radiation oncology (94.4% vs 72.7%; P = .04).

Case Management

The 3 clinical cases demonstrated the heterogeneity of management approaches for OMD. The first described a man aged 65 years with PCa and 2 asymptomatic pelvic bone metastases. Ninety-three respondents (90.3%) recommended RT at the primary site and 74.8% recommended RT to both the primary site and metastatic foci. Sixty-three respondents (67.7%) recommended a STAMPEDE-compatible dose, and 30 (32.3%) recommended a definitive dose.

The second clinical case was a 60-year-old man with a cT1N2M1 NSCLC, with a solitary metastatic focus to the left iliac wing. Fifty-eight respondents (54.7%) recommended upfront systemic chemotherapy and the option of local therapy to the chest and metastatic focus after initial chemotherapy; 28 respondents (26.4%) recommended upfront chemoradiation to the chest and definitive radiation to the left iliac wing metastasis.

The third clinical case described a male aged 70 years with a history of a treated base of tongue squamous cell carcinoma, with a solitary metastatic focus within the right lung. Respondents could pick multiple treatment options and 85 (81.7%) favored upfront definitive local therapy with surgery or stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), rather than upfront chemotherapy, with future consideration for local treatment. About half of respondents (51.8%) recommended SBRT and 41.2% would let the patient decide between surgery or SBRT. Additionally, 39.6% included in their patient counselling that the treatment may be for curative intent.

Discussion

The use of local treatment to increased PFS, OS, or even cure treatment for OMD has become more accepted since the 2018 ASTRO meeting.4,5 Palma et al analyzed a controlled primary malignancy of any histology and ≤ 5 metastatic lesions, with all lesions amenable to SBRT.4 With a median follow-up of 51 months when comparing the standard-of-care (SOC) arm and the SBRT arm, the 5-year PFS was not reached and the 5-year OS rates were 17.7% and 42.3% (P = .006), respectively. In the SBRT arm, about 1 in 5 patients survived > 5 years without a recurrence or disease progression, vs 0 patients in the control arm. There was a 29% rate of grade 2 or higher toxicity in the SBRT arm, including 3 deaths that were likely due to treatment. Subsequent trials, such as the phase 3 SABR-COMET-3 (1-3 metastases), phase 3 SABR-COMET-10 (4-10 metastases), and phase 1 ARREST (> 10 metastases) trials, have been specifically designed to minimize treatment-related toxicities.13-15

Gomez et al analyzed patients at 3 sites with a controlled NSCLC primary tumor and ≤ 3 metastases.5 At a follow-up of 38.8 months, the PFS was 4.4 months in the SOC arm vs 14.2 months in the RT and/or surgery local treatment arm (P = .02). There was also an OS benefit of 17.0 vs 41.2 months (P = .02), respectively.

Several RCTs soon followed that demonstrated improved PFS and OS with local radiotherapy for OMD; however, total metastatic ablation of the foci is necessary to attain these PFS and OS benefits.6-9 Still, an oncologic benefit has yet to be proven. The randomized NRGBR002 study phase 2/3 trial for oligometastatic breast cancer included patients with ≤ 4 extracranial metastases and controlled primary disease to metastasis-directed therapy (SBRT and/ or surgical resection) and systemic therapy vs systemic therapy alone.10 The study did not demonstrate improved PFS or OS at 3 years. However, for most breast cancers, especially with the rapid advancements in systemic therapy that have been achieved, longer follow-up may be necessary to detect a significant difference.

The prospective single-arm phase 2 SABR-5 trial retrospectively demonstrated important lessons about the timing of SBRT and systemic therapy.11 This study included patients with ≤ 5 metastases of any histology, and they received SBRT to all lesions. SABR-5 retrospectively compared patients who received upfront systemic therapy followed by SBRT vs another cohort that first received SBRT and did not receive systemic therapy until there was disease progression. Patients with oligo-progression were excluded, as it demonstrated systemic drug resistance. At a median follow-up time of 34 months, delayed systemic treatment was associated with shorter PFS (23 vs 34 months, respectively; P = .001), but not worse 3-year OS (80% vs 85%, respectively; P = .66). In addition, the delayed systemic treatment arm demonstrated a reduced risk of grade 2 or higher SBRT-related toxicity (odds ratio, 0.35; P < .001).

Similarly, the STOMP phase 2 trial analyzed the role of metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) in delaying initiation of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in a randomized phase 2 trial.16 This study included patients with asymptomatic PCa with a biochemical recurrence after primary treatment, 1 to 3 extracranial metastatic lesions, and serum testosterone levels > 50 ng/mL. Sixty-two patients were randomized 1:1 to either MDT (SBRT or surgery) of all lesions or surveillance. The 5-year ADT-free survival was 34% for MDT vs 8% for surveillance (P = .06).

VHA Radiation Oncology

The VHA has 138 departments of medical oncology, but only 41 departments of radiation oncology. Compared with medical oncologists without an on-site radiation oncology department, those with on-site departments were more likely to believe that local RT was potentially curative (94.4% vs 72.7%, respectively; P = .04). This finding suggests that a cancer center that includes both specialties has closer collaboration, which results in greater inclination to embrace local RT for OMD, as it has demonstrated PFS and OS benefits.

The radiation and medical oncologists surveyed had statistically significant differences in response by specialty regarding the maximal number of lesions still believed to constitute OMD. Most radiation oncologists classified ≤ 5 lesions as OMD, whereas most medical oncologists classified ≤ 3 lesions as OMD. This difference is not unexpected. There is no universally agreed-upon definition of OMD, and criteria differ across studies.

While the SABR-COMET trial did include ≤ 5 metastatic lesions, it was a phase 2 RCT, making subgroup analysis difficult. Ongoing phase 3 trials that are more specific in the number of metastases, comparing 1 to 3 vs 4 to 10 metastases (SABR-COMET-3 and SABR-COMET-10, respectively).13,14 There is even an ongoing phase 1 trial (ARREST) studying the potential benefits of treating (“restraining”) > 10 metastases, if dosimetrically feasible.15 Within the VHA, VA STARPORT is investigating MDT for recurrent or de novo hormone-sensitive metastatic PCa.17 The ongoing HALT phase 2/3 trial focuses on patients with actionable mutations to help determine management of oligo-progression in mutation-positive NSCLC.18

There was no significant difference by specialty in who responded that offering local RT for OMD treatment should not be limited by histology (55.2% of radiation oncologists and 50.0% of medical oncologists; P = .60). Oncologists could make the argument that some histologies (eg, pancreatic adenocarcinomas) have such poor prognoses that local RT would not meaningfully affect oncologic outcomes, while potentially adding toxicity, whereas others could point to improved systemic therapy regimens and the low toxicity rates with careful hypofractionation regimens. Of note, the 41-patient phase 2 EXTEND trial for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma suggested an oncologic benefit to MDT, with far better PFS and no grade ≥ 3 toxicities related to MDT.19 About half of respondents for each specialty believed the primary histology should affect the decision. Further clarification may emerge from phase 3 trials.

Of note, a 2023 study of 44 radiation and medical oncologists at 2 Harvard Medical School-affiliated hospitals found that for synchronous OMD, 50.0% of medical oncologists and 5.3% (P < .01) of radiation oncologists recommended systemic treatment, suggesting a greater divergence in approach than found in this study.20

Limitations

The response rate of 17.0% raised a potential for selection bias, but this rate is expected for a nonincentivized medical survey. A study by the American Board of Internal Medicine with 11 surveys and 6 weekly email contacts only generated a 23.7% response rate, while another study among physicians demonstrated a 4.5% response rate for email-based contact and 11.8% for mail-based contact.21,22 We could have asked participants questions regarding demographics and geography to ensure the survey represented a diverse sample of the medical community, although additional questions would likely suppress the response rate. Additional data collection about respondents may elucidate the rationale for differences in their responses, especially between the specialties. In a planned subsequent survey in several years, the question on the number of lesions that qualifies as OMD may be amended to reflect the context and dosimetry for the maximal number of metastases constituting OMD; the joint ESTRO-ASTRO consensus defined OMD as 1 to 5 metastatic lesions, but in which all metastatic sites must be safely treatable.12 Also, fewer example cases could be included to simplify the survey and boost response rates. A future survey may ask about the timing of SBRT and systemic therapy, and whether SBRT can safely delay systemic therapy.

Conclusions

Survey results demonstrated significant confidence among both radiation oncologists and medical oncologists that local RT for OMD improves outcomes, which is encouraging and a reflection of the recent evidence-based paradigm shift in viewing metastatic disease as a spectrum. However, there is a difference between radiation oncologists and medical oncologists in how they define OMD, and preferred treatment of the sample cases presented revealed nuanced differences by specialty. Close collaboration with radiation oncologists influences the belief of medical oncologists in the beneficial role of RT for OMD. As more phase 3 data for OMD local treatments emerge, additional investigation is needed on how beliefs and practice patterns evolve among radiation and medical oncologists.

- Barney JD, Churchill EJ. Adenocarcinoma of the kidney with metastasis to the lung. J Urology. 1939.

- Hellman S, Weichselbaum RR. Oligometastases. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):8-10. doi:10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.8

- Ruers T, Punt C, Van Coevorden F, et al. Radiofrequency ablation combined with systemic treatment versus systemic treatment alone in patients with non-resectable colorectal liver metastases: a randomized EORTC Intergroup phase II study (EORTC 4004). Ann Oncol. 2012;23(10):2619-2626. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds053

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of oligometastatic cancers: long-term results of the SABR-COMET phase II randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(25):2830- 2838. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.00818

- Gomez DR, Tang C, Zhang J, et al. Local consolidative therapy vs. maintenance therapy or observation for patients with oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results of a multi-institutional, phase II, randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(18):1558-1565. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00201

- Iyengar P, Wardak Z, Gerber DE, et al. Consolidative radiotherapy for limited metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(1):e173501. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3501

- Phillips R, Shi WY, Deek M, et al. Outcomes of observation vs stereotactic ablative radiation for oligometastatic prostate cancer: the ORIOLE phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):650-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0147

- Wang XS, Bai YF, Verma V, et al. Randomized trial of first-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor with or without radiotherapy for synchronous oligometastatic EGFR-mutated NSCLC. J Natl Cancer Inst 2023;115(6):742-748. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac015

- Tang C, Sherry AD, Haymaker C, et al. Addition of metastasis- directed therapy to intermittent hormone therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer (EXTEND): a multicenter, randomized phase II trial. Am Soc Radiat Oncol Annu Meet. 2023;9(6):825-834. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.0161

- Chmura SJ, Winter KA, Woodward WA, et al. NRG-BR002: a phase IIR/III trial of standard of care systemic therapy with or without stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) and/or surgical resection (SR) for newly oligometastatic breast cancer (NCT02364557). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1007. doi:10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.1007

- Baker S, Lechner L, Liu M, et al. Upfront versus delayed systemic therapy in patients with oligometastatic cancer treated with SABR in the phase 2 SABR-5 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2024;118(5):1497-1506. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.11.007

- Lievens Y, Guckenberger M, Gomez D, et al. Defining oligometastatic disease from a radiation oncology perspective: an ESTRO-ASTRO consensus document. Radiother Oncol. 2020;148:157-166. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.003

- Olson R, Mathews L, Liu M, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of 1-3 oligometastatic tumors (SABR-COMET-3): study protocol for a randomized phase III trial. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):380. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-06876-4

- Palma DA, Olson R, Harrow S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for the comprehensive treatment of 4-10 oligometastatic tumors (SABR-COMET-10): study protocol for a randomized phase III trial. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):816. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5977-6

- Bauman GS, Corkum MT, Fakir H, et al. Ablative radiation therapy to restrain everything safely treatable (ARREST): study protocol for a phase I trial treating polymetastatic cancer with stereotactic radiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):405. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08136-5

- Ost P, Reynders D, Decaestecker K, et al. Surveillance or metastasis-directed therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer recurrence (STOMP): five-year results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:suppl.

- Solanki AA, Campbell D, Carlson K, et al. Veterans Affairs seamless phase II/III randomized trial of standard systemic therapy with or without PET-directed local therapy for oligometastatic prostate cancer (VA STARPORT). J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:16.

- McDonald F, Guckenberger M, Popat S. EP08.03-005 HALT – Targeted therapy with or without dose-intensified radiotherapy in oligo-progressive disease in oncogene addicted lung tumours. J Thor Oncol. 2022;17:S492.

- Ludmir EB, Sherry AD, Fellman BM, et al. Addition of metastasis- directed therapy to systemic therapy for oligometastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (EXTEND): a multicenter, randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(32):3795-3805. doi:10.1200/JCO.24.00081

- Cho HL, Balboni T, Christ SB, et al. Is oligometastatic cancer curable? A survey of oncologist perspectives, decision making, and communication. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2023;8(5):101221. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2023.101221

- Barnhart BJ, Reddy SG, Arnold GK. Remind me again: physician response to web surveys: the effect of email reminders across 11 opinion survey efforts at the American Board of Internal Medicine from 2017 to 2019. Eval Health Prof. 2021;44(3):245-259. doi:10.1177/01632787211019445

- Murphy CC, Lee SJC, Geiger AM, et al. A randomized trial of mail and email recruitment strategies for a physician survey on clinical trial accrual. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12874-020-01014-x

The treatment of metastatic solid tumors has been based historically on systemic therapies, with the goal of delaying progression and extend life as long as possible, with tolerable treatment-related adverse events. Some exceptions were made for local treatment with surgery or radiotherapy (RT), often for patients with a single metastasis. A 1939 report describes a patient with renal adenocarcinoma and a solitary lung metastasis who underwent RT to the lung lesion after nephrectomy and subsequently partial lobectomy after the metastatic lesion progressed. The authors argued that if a metastasis appears solitary and accessible, it is plausible to remove it in addition to the primary growth.1

In 1995 Hellman and Weichselbaum proposed oligometastatic disease (OMD). They reasoned that malignancy exists along a spectrum from localized disease to widely disseminated disease, with OMD existing in between with a still-restricted tumor metastatic capacity. Appropriately selected patients with OMD may be candidates for prolonged disease-free survival or cure with the addition of local therapy to systemic therapy.2

The EORTC 4004 phase 2 randomized control trial (RCT) analyzed radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for colorectal liver metastases with systemic therapy vs systemic therapy alone for patients with ≤ 9 liver lesions.3 Systemic therapyconsisted of 5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin, with bevacizumab added to the regimen 3.5 years into the study, per updated standard- of-care. This trial was the first to demonstrate the benefit of aggressive local treatment vs system treatment alone for OMD with a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit (16.8 vs 9.9 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P = .03) and overall survival (OS) benefit (45.3 vs 40.5 months; HR, 0.74; P = .02) with the addition of local treatment with RFA.

Since the presentations of the SABR-COMET phase 2 RCT and another study by Gomez et al at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) 2018 annual meeting, the paradigm for offering local RT for OMD has rapidly evolved. Both studies found PFS and OS benefits of RT for patients with OMD.4,5 Additional RCTs have since demonstrated that for properly selected patients with OMD, aggressive local RT improved PFS and OS.6-9 These small studies have led to larger RCTs to better understand who benefits from local consolidative treatment, particularly RT.10,11

There is a large degree of heterogeneity in how oncologists define and approach OMD treatment. The 2020 European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) and ASTRO consensus guidelines defined the OMD state as 1 to 5 metastatic lesions for which all metastatic sites are safely treatable.12 The purpose of this study was to evaluate perceptions and practice patterns among radiation oncologists and medical oncologists regarding the use of local RT for OMD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Methods

A 12-question survey was developed by the VHA Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force using the ESTRO-ASTRO consensus guidelines to define OMD. The survey was emailed to the VHA radiation oncology and medical oncology listservs on August 1, 2023. These listservs consist of physicians in these specialties either directly employed by the VHA or serve in its facilities as contractors. The original response closure date was August 11, 2023, but it was extended to August 18, 2023, to increase responses. No incentives were offered to respondents. Two email reminders were sent to the medical oncology listserv and 3 to the radiation oncology listserv. Descriptive statistics and X2 tests were used for data analysis. The impact of specialty and presence of an on-site department of radiation oncology were reviewed. This project was approved by the VHA National Oncology Program and National Radiation Oncology Program.

Results

The survey was sent to 125 radiation oncologists and 515 medical oncologists and 106 were completed for a 16.6% response rate. There were 59 (55.7%) radiation oncologist responses and 47 (44.3%) medical oncologist responses. Most (96.2%) respondents were board-certified, and 84 (79.2%) were affiliated with an academic center. Not every respondent answered every question (Table).

All respondents (n = 105) indicated there is a potential benefit of high-dose RT for appropriately selected cases. Ninety-four oncologists (88.7%) believed that RT for OMD contributes to cure (88.1% of radiation oncologists, 89.4% of medical oncologists; P = .84) for appropriately selected cases. Some respondents who did not believe RT for OMD contributes to cure added comments about other perceived benefits, such as local disease control for palliation, delaying systemic therapy with its associated toxicities, and prolongation of disease-free survival or OS. A higher percentage of respondents with academic affiliations believed high-dose RT contributes to cure, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1).

Fifty-five respondents (51.9%; 55.2% radiation oncologists vs 50.0% medical oncologists; P = .60) responded that local RT for OMD treatment should not be limited by primary tumor type. Of respondents who responded that OMD treatment should be limited based on the type of primary tumor, many provided comments that argued there was a benefit for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate adenocarcinoma (PCa), and colorectal cancer.

The definition of how many metastatic lesions qualify as OMD varied. A total of 48.6% of respondents defined OMD as ≤ 3 lesions and 42.9% answered ≤ 5 lesions. A majority of radiation oncologists (55.2%) classified ≤ 5 lesions as OMD, whereas a majority of medical oncologists (66.0%) considered ≤ 3 lesions as OMD (P = .006) (Figure 2).

Thirty-six medical oncologists (76.6%) report having an on-site department of radiation oncology (Figure 3). This subgroup was more likely to consider local RT potentially curative compared with their medical oncology peers without on-site radiation oncology (94.4% vs 72.7%; P = .04).

Case Management

The 3 clinical cases demonstrated the heterogeneity of management approaches for OMD. The first described a man aged 65 years with PCa and 2 asymptomatic pelvic bone metastases. Ninety-three respondents (90.3%) recommended RT at the primary site and 74.8% recommended RT to both the primary site and metastatic foci. Sixty-three respondents (67.7%) recommended a STAMPEDE-compatible dose, and 30 (32.3%) recommended a definitive dose.

The second clinical case was a 60-year-old man with a cT1N2M1 NSCLC, with a solitary metastatic focus to the left iliac wing. Fifty-eight respondents (54.7%) recommended upfront systemic chemotherapy and the option of local therapy to the chest and metastatic focus after initial chemotherapy; 28 respondents (26.4%) recommended upfront chemoradiation to the chest and definitive radiation to the left iliac wing metastasis.

The third clinical case described a male aged 70 years with a history of a treated base of tongue squamous cell carcinoma, with a solitary metastatic focus within the right lung. Respondents could pick multiple treatment options and 85 (81.7%) favored upfront definitive local therapy with surgery or stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), rather than upfront chemotherapy, with future consideration for local treatment. About half of respondents (51.8%) recommended SBRT and 41.2% would let the patient decide between surgery or SBRT. Additionally, 39.6% included in their patient counselling that the treatment may be for curative intent.

Discussion

The use of local treatment to increased PFS, OS, or even cure treatment for OMD has become more accepted since the 2018 ASTRO meeting.4,5 Palma et al analyzed a controlled primary malignancy of any histology and ≤ 5 metastatic lesions, with all lesions amenable to SBRT.4 With a median follow-up of 51 months when comparing the standard-of-care (SOC) arm and the SBRT arm, the 5-year PFS was not reached and the 5-year OS rates were 17.7% and 42.3% (P = .006), respectively. In the SBRT arm, about 1 in 5 patients survived > 5 years without a recurrence or disease progression, vs 0 patients in the control arm. There was a 29% rate of grade 2 or higher toxicity in the SBRT arm, including 3 deaths that were likely due to treatment. Subsequent trials, such as the phase 3 SABR-COMET-3 (1-3 metastases), phase 3 SABR-COMET-10 (4-10 metastases), and phase 1 ARREST (> 10 metastases) trials, have been specifically designed to minimize treatment-related toxicities.13-15

Gomez et al analyzed patients at 3 sites with a controlled NSCLC primary tumor and ≤ 3 metastases.5 At a follow-up of 38.8 months, the PFS was 4.4 months in the SOC arm vs 14.2 months in the RT and/or surgery local treatment arm (P = .02). There was also an OS benefit of 17.0 vs 41.2 months (P = .02), respectively.

Several RCTs soon followed that demonstrated improved PFS and OS with local radiotherapy for OMD; however, total metastatic ablation of the foci is necessary to attain these PFS and OS benefits.6-9 Still, an oncologic benefit has yet to be proven. The randomized NRGBR002 study phase 2/3 trial for oligometastatic breast cancer included patients with ≤ 4 extracranial metastases and controlled primary disease to metastasis-directed therapy (SBRT and/ or surgical resection) and systemic therapy vs systemic therapy alone.10 The study did not demonstrate improved PFS or OS at 3 years. However, for most breast cancers, especially with the rapid advancements in systemic therapy that have been achieved, longer follow-up may be necessary to detect a significant difference.

The prospective single-arm phase 2 SABR-5 trial retrospectively demonstrated important lessons about the timing of SBRT and systemic therapy.11 This study included patients with ≤ 5 metastases of any histology, and they received SBRT to all lesions. SABR-5 retrospectively compared patients who received upfront systemic therapy followed by SBRT vs another cohort that first received SBRT and did not receive systemic therapy until there was disease progression. Patients with oligo-progression were excluded, as it demonstrated systemic drug resistance. At a median follow-up time of 34 months, delayed systemic treatment was associated with shorter PFS (23 vs 34 months, respectively; P = .001), but not worse 3-year OS (80% vs 85%, respectively; P = .66). In addition, the delayed systemic treatment arm demonstrated a reduced risk of grade 2 or higher SBRT-related toxicity (odds ratio, 0.35; P < .001).

Similarly, the STOMP phase 2 trial analyzed the role of metastasis-directed therapy (MDT) in delaying initiation of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in a randomized phase 2 trial.16 This study included patients with asymptomatic PCa with a biochemical recurrence after primary treatment, 1 to 3 extracranial metastatic lesions, and serum testosterone levels > 50 ng/mL. Sixty-two patients were randomized 1:1 to either MDT (SBRT or surgery) of all lesions or surveillance. The 5-year ADT-free survival was 34% for MDT vs 8% for surveillance (P = .06).

VHA Radiation Oncology

The VHA has 138 departments of medical oncology, but only 41 departments of radiation oncology. Compared with medical oncologists without an on-site radiation oncology department, those with on-site departments were more likely to believe that local RT was potentially curative (94.4% vs 72.7%, respectively; P = .04). This finding suggests that a cancer center that includes both specialties has closer collaboration, which results in greater inclination to embrace local RT for OMD, as it has demonstrated PFS and OS benefits.

The radiation and medical oncologists surveyed had statistically significant differences in response by specialty regarding the maximal number of lesions still believed to constitute OMD. Most radiation oncologists classified ≤ 5 lesions as OMD, whereas most medical oncologists classified ≤ 3 lesions as OMD. This difference is not unexpected. There is no universally agreed-upon definition of OMD, and criteria differ across studies.

While the SABR-COMET trial did include ≤ 5 metastatic lesions, it was a phase 2 RCT, making subgroup analysis difficult. Ongoing phase 3 trials that are more specific in the number of metastases, comparing 1 to 3 vs 4 to 10 metastases (SABR-COMET-3 and SABR-COMET-10, respectively).13,14 There is even an ongoing phase 1 trial (ARREST) studying the potential benefits of treating (“restraining”) > 10 metastases, if dosimetrically feasible.15 Within the VHA, VA STARPORT is investigating MDT for recurrent or de novo hormone-sensitive metastatic PCa.17 The ongoing HALT phase 2/3 trial focuses on patients with actionable mutations to help determine management of oligo-progression in mutation-positive NSCLC.18

There was no significant difference by specialty in who responded that offering local RT for OMD treatment should not be limited by histology (55.2% of radiation oncologists and 50.0% of medical oncologists; P = .60). Oncologists could make the argument that some histologies (eg, pancreatic adenocarcinomas) have such poor prognoses that local RT would not meaningfully affect oncologic outcomes, while potentially adding toxicity, whereas others could point to improved systemic therapy regimens and the low toxicity rates with careful hypofractionation regimens. Of note, the 41-patient phase 2 EXTEND trial for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma suggested an oncologic benefit to MDT, with far better PFS and no grade ≥ 3 toxicities related to MDT.19 About half of respondents for each specialty believed the primary histology should affect the decision. Further clarification may emerge from phase 3 trials.

Of note, a 2023 study of 44 radiation and medical oncologists at 2 Harvard Medical School-affiliated hospitals found that for synchronous OMD, 50.0% of medical oncologists and 5.3% (P < .01) of radiation oncologists recommended systemic treatment, suggesting a greater divergence in approach than found in this study.20

Limitations

The response rate of 17.0% raised a potential for selection bias, but this rate is expected for a nonincentivized medical survey. A study by the American Board of Internal Medicine with 11 surveys and 6 weekly email contacts only generated a 23.7% response rate, while another study among physicians demonstrated a 4.5% response rate for email-based contact and 11.8% for mail-based contact.21,22 We could have asked participants questions regarding demographics and geography to ensure the survey represented a diverse sample of the medical community, although additional questions would likely suppress the response rate. Additional data collection about respondents may elucidate the rationale for differences in their responses, especially between the specialties. In a planned subsequent survey in several years, the question on the number of lesions that qualifies as OMD may be amended to reflect the context and dosimetry for the maximal number of metastases constituting OMD; the joint ESTRO-ASTRO consensus defined OMD as 1 to 5 metastatic lesions, but in which all metastatic sites must be safely treatable.12 Also, fewer example cases could be included to simplify the survey and boost response rates. A future survey may ask about the timing of SBRT and systemic therapy, and whether SBRT can safely delay systemic therapy.

Conclusions

Survey results demonstrated significant confidence among both radiation oncologists and medical oncologists that local RT for OMD improves outcomes, which is encouraging and a reflection of the recent evidence-based paradigm shift in viewing metastatic disease as a spectrum. However, there is a difference between radiation oncologists and medical oncologists in how they define OMD, and preferred treatment of the sample cases presented revealed nuanced differences by specialty. Close collaboration with radiation oncologists influences the belief of medical oncologists in the beneficial role of RT for OMD. As more phase 3 data for OMD local treatments emerge, additional investigation is needed on how beliefs and practice patterns evolve among radiation and medical oncologists.

The treatment of metastatic solid tumors has been based historically on systemic therapies, with the goal of delaying progression and extend life as long as possible, with tolerable treatment-related adverse events. Some exceptions were made for local treatment with surgery or radiotherapy (RT), often for patients with a single metastasis. A 1939 report describes a patient with renal adenocarcinoma and a solitary lung metastasis who underwent RT to the lung lesion after nephrectomy and subsequently partial lobectomy after the metastatic lesion progressed. The authors argued that if a metastasis appears solitary and accessible, it is plausible to remove it in addition to the primary growth.1

In 1995 Hellman and Weichselbaum proposed oligometastatic disease (OMD). They reasoned that malignancy exists along a spectrum from localized disease to widely disseminated disease, with OMD existing in between with a still-restricted tumor metastatic capacity. Appropriately selected patients with OMD may be candidates for prolonged disease-free survival or cure with the addition of local therapy to systemic therapy.2

The EORTC 4004 phase 2 randomized control trial (RCT) analyzed radiofrequency ablation (RFA) for colorectal liver metastases with systemic therapy vs systemic therapy alone for patients with ≤ 9 liver lesions.3 Systemic therapyconsisted of 5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin, with bevacizumab added to the regimen 3.5 years into the study, per updated standard- of-care. This trial was the first to demonstrate the benefit of aggressive local treatment vs system treatment alone for OMD with a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit (16.8 vs 9.9 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P = .03) and overall survival (OS) benefit (45.3 vs 40.5 months; HR, 0.74; P = .02) with the addition of local treatment with RFA.

Since the presentations of the SABR-COMET phase 2 RCT and another study by Gomez et al at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) 2018 annual meeting, the paradigm for offering local RT for OMD has rapidly evolved. Both studies found PFS and OS benefits of RT for patients with OMD.4,5 Additional RCTs have since demonstrated that for properly selected patients with OMD, aggressive local RT improved PFS and OS.6-9 These small studies have led to larger RCTs to better understand who benefits from local consolidative treatment, particularly RT.10,11

There is a large degree of heterogeneity in how oncologists define and approach OMD treatment. The 2020 European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) and ASTRO consensus guidelines defined the OMD state as 1 to 5 metastatic lesions for which all metastatic sites are safely treatable.12 The purpose of this study was to evaluate perceptions and practice patterns among radiation oncologists and medical oncologists regarding the use of local RT for OMD across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Methods

A 12-question survey was developed by the VHA Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force using the ESTRO-ASTRO consensus guidelines to define OMD. The survey was emailed to the VHA radiation oncology and medical oncology listservs on August 1, 2023. These listservs consist of physicians in these specialties either directly employed by the VHA or serve in its facilities as contractors. The original response closure date was August 11, 2023, but it was extended to August 18, 2023, to increase responses. No incentives were offered to respondents. Two email reminders were sent to the medical oncology listserv and 3 to the radiation oncology listserv. Descriptive statistics and X2 tests were used for data analysis. The impact of specialty and presence of an on-site department of radiation oncology were reviewed. This project was approved by the VHA National Oncology Program and National Radiation Oncology Program.

Results

The survey was sent to 125 radiation oncologists and 515 medical oncologists and 106 were completed for a 16.6% response rate. There were 59 (55.7%) radiation oncologist responses and 47 (44.3%) medical oncologist responses. Most (96.2%) respondents were board-certified, and 84 (79.2%) were affiliated with an academic center. Not every respondent answered every question (Table).

All respondents (n = 105) indicated there is a potential benefit of high-dose RT for appropriately selected cases. Ninety-four oncologists (88.7%) believed that RT for OMD contributes to cure (88.1% of radiation oncologists, 89.4% of medical oncologists; P = .84) for appropriately selected cases. Some respondents who did not believe RT for OMD contributes to cure added comments about other perceived benefits, such as local disease control for palliation, delaying systemic therapy with its associated toxicities, and prolongation of disease-free survival or OS. A higher percentage of respondents with academic affiliations believed high-dose RT contributes to cure, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1).

Fifty-five respondents (51.9%; 55.2% radiation oncologists vs 50.0% medical oncologists; P = .60) responded that local RT for OMD treatment should not be limited by primary tumor type. Of respondents who responded that OMD treatment should be limited based on the type of primary tumor, many provided comments that argued there was a benefit for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), prostate adenocarcinoma (PCa), and colorectal cancer.

The definition of how many metastatic lesions qualify as OMD varied. A total of 48.6% of respondents defined OMD as ≤ 3 lesions and 42.9% answered ≤ 5 lesions. A majority of radiation oncologists (55.2%) classified ≤ 5 lesions as OMD, whereas a majority of medical oncologists (66.0%) considered ≤ 3 lesions as OMD (P = .006) (Figure 2).

Thirty-six medical oncologists (76.6%) report having an on-site department of radiation oncology (Figure 3). This subgroup was more likely to consider local RT potentially curative compared with their medical oncology peers without on-site radiation oncology (94.4% vs 72.7%; P = .04).

Case Management

The 3 clinical cases demonstrated the heterogeneity of management approaches for OMD. The first described a man aged 65 years with PCa and 2 asymptomatic pelvic bone metastases. Ninety-three respondents (90.3%) recommended RT at the primary site and 74.8% recommended RT to both the primary site and metastatic foci. Sixty-three respondents (67.7%) recommended a STAMPEDE-compatible dose, and 30 (32.3%) recommended a definitive dose.

The second clinical case was a 60-year-old man with a cT1N2M1 NSCLC, with a solitary metastatic focus to the left iliac wing. Fifty-eight respondents (54.7%) recommended upfront systemic chemotherapy and the option of local therapy to the chest and metastatic focus after initial chemotherapy; 28 respondents (26.4%) recommended upfront chemoradiation to the chest and definitive radiation to the left iliac wing metastasis.

The third clinical case described a male aged 70 years with a history of a treated base of tongue squamous cell carcinoma, with a solitary metastatic focus within the right lung. Respondents could pick multiple treatment options and 85 (81.7%) favored upfront definitive local therapy with surgery or stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), rather than upfront chemotherapy, with future consideration for local treatment. About half of respondents (51.8%) recommended SBRT and 41.2% would let the patient decide between surgery or SBRT. Additionally, 39.6% included in their patient counselling that the treatment may be for curative intent.

Discussion