User login

The Right Choice? A New Chapter

As I write this last installment of “The Right Choice?” for ACS Surgery News, a number of different emotions are going through my mind all at the same time. I am surprised at how quickly the time has passed since I wrote my first surgical ethics column for SN in 2011. In the 33 columns that I have written since then, I have tried to focus on aspects of surgical practice that emphasize the ethical dimension. I have tried to write columns that would be of interest to practicing surgeons in any setting and not only to academic surgeons that practice in urban environments such as I practice in. This is the last column and thus the end of a chapter of my life and the beginning of a new one.

Over the last 7 years, I have been flattered by the comments from fellow surgeons who report that they actually read the column. I have always said that I wrote this column with the expectation that no one would actually read them. I have to confess that this is not completely true. As I wrote each column, I did so as though I was writing them for my father to read. My father, S. Peter Angelos, MD, FACS, was a general surgeon who spent his entire career practicing in the town of Plattsburgh, N.Y., where he grew up. My father’s practice was very different from mine. I work at an urban academic medical center where I have a very narrow subspecialty practice in endocrine surgery. My father had a small-town community practice of “bread and butter” general surgery. Yet, when he and I would talk about patients, the commonality of the relationship between a surgeon and a patient transcended these differences. I realize that in many ways, I wrote this column as a way of organizing my own thoughts and then presenting them to my father in the hopes that he would find them of some value.

For several years, I would send drafts of my column to my parents, and both my father and mother would read them and give me suggestions. Many of the earlier columns were changed for the better by their comments. In recent years, my father’s health declined and he was no longer able to give me comments. Nevertheless, I continued to compose them as though writing for him. Approximately 6 weeks ago, my father passed away. It has been sad for my mother and my entire family. We all realized that it was the end of one chapter of our lives and the start of a new one without my father.

I find the concept of “beginning a new chapter” to be an important one for surgeons to reflect upon. There are certain events, such as the death of a parent, that force us to think about the end of one phase of life and the beginning of another phase. However, the division of one’s experience into phases or chapters, is somewhat arbitrary. This past summer I became a patient and had surgery myself for the first time. I cannot help but think of that operation as the start of a new chapter for me. I am convinced that although all patients may not reflect upon surgery in the same way that I did, nevertheless, an operation is a dramatic event that most people remember for a long time. In this context, many people will see their interactions with their surgeon and their operation as the end of one chapter and the beginning of a new one.

In this context, it is critical for surgeons to be fully cognizant of the great impact that we may have on our patient’s internal narratives of their lives. When we operate on someone, we run the risk of that person’s functional status changing forever. We may be the means by which our patient is cured of cancer or suffers a debilitating complication. As surgeons, we therefore, occupy a potentially significant role in the trajectory of our patients’ lives. I believe that the relationship between a surgeon and a patient is distinctive and central in the narrative that so many patients create about their lives. It is essential that surgeons continue to appreciate the value of the quality of that relationship with our patients and the impact—potentially positive or negative—that it can have upon our patients.

Throughout medicine, in general, and in surgery in particular, one cannot go a week without hearing about the problem of burnout. Although there is no single cure for burnout, I do believe that paying attention to the ethical dimension of our interactions with our patients and the impact that surgery can have on their lives will go a long way to reducing the risks of burnout among surgeons.

In an era in which we are often pushed to increase RVUs at the expense of spending time with individual patients, we must not forget how significant our relationships with our patients can be. I believe that attention to this relationship will be beneficial to patients and also to us as we help our patients start new chapters in their lives.

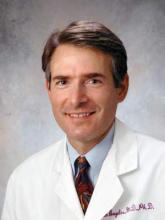

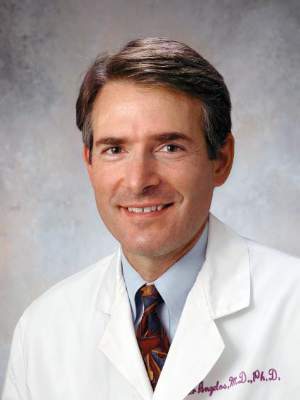

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

As I write this last installment of “The Right Choice?” for ACS Surgery News, a number of different emotions are going through my mind all at the same time. I am surprised at how quickly the time has passed since I wrote my first surgical ethics column for SN in 2011. In the 33 columns that I have written since then, I have tried to focus on aspects of surgical practice that emphasize the ethical dimension. I have tried to write columns that would be of interest to practicing surgeons in any setting and not only to academic surgeons that practice in urban environments such as I practice in. This is the last column and thus the end of a chapter of my life and the beginning of a new one.

Over the last 7 years, I have been flattered by the comments from fellow surgeons who report that they actually read the column. I have always said that I wrote this column with the expectation that no one would actually read them. I have to confess that this is not completely true. As I wrote each column, I did so as though I was writing them for my father to read. My father, S. Peter Angelos, MD, FACS, was a general surgeon who spent his entire career practicing in the town of Plattsburgh, N.Y., where he grew up. My father’s practice was very different from mine. I work at an urban academic medical center where I have a very narrow subspecialty practice in endocrine surgery. My father had a small-town community practice of “bread and butter” general surgery. Yet, when he and I would talk about patients, the commonality of the relationship between a surgeon and a patient transcended these differences. I realize that in many ways, I wrote this column as a way of organizing my own thoughts and then presenting them to my father in the hopes that he would find them of some value.

For several years, I would send drafts of my column to my parents, and both my father and mother would read them and give me suggestions. Many of the earlier columns were changed for the better by their comments. In recent years, my father’s health declined and he was no longer able to give me comments. Nevertheless, I continued to compose them as though writing for him. Approximately 6 weeks ago, my father passed away. It has been sad for my mother and my entire family. We all realized that it was the end of one chapter of our lives and the start of a new one without my father.

I find the concept of “beginning a new chapter” to be an important one for surgeons to reflect upon. There are certain events, such as the death of a parent, that force us to think about the end of one phase of life and the beginning of another phase. However, the division of one’s experience into phases or chapters, is somewhat arbitrary. This past summer I became a patient and had surgery myself for the first time. I cannot help but think of that operation as the start of a new chapter for me. I am convinced that although all patients may not reflect upon surgery in the same way that I did, nevertheless, an operation is a dramatic event that most people remember for a long time. In this context, many people will see their interactions with their surgeon and their operation as the end of one chapter and the beginning of a new one.

In this context, it is critical for surgeons to be fully cognizant of the great impact that we may have on our patient’s internal narratives of their lives. When we operate on someone, we run the risk of that person’s functional status changing forever. We may be the means by which our patient is cured of cancer or suffers a debilitating complication. As surgeons, we therefore, occupy a potentially significant role in the trajectory of our patients’ lives. I believe that the relationship between a surgeon and a patient is distinctive and central in the narrative that so many patients create about their lives. It is essential that surgeons continue to appreciate the value of the quality of that relationship with our patients and the impact—potentially positive or negative—that it can have upon our patients.

Throughout medicine, in general, and in surgery in particular, one cannot go a week without hearing about the problem of burnout. Although there is no single cure for burnout, I do believe that paying attention to the ethical dimension of our interactions with our patients and the impact that surgery can have on their lives will go a long way to reducing the risks of burnout among surgeons.

In an era in which we are often pushed to increase RVUs at the expense of spending time with individual patients, we must not forget how significant our relationships with our patients can be. I believe that attention to this relationship will be beneficial to patients and also to us as we help our patients start new chapters in their lives.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

As I write this last installment of “The Right Choice?” for ACS Surgery News, a number of different emotions are going through my mind all at the same time. I am surprised at how quickly the time has passed since I wrote my first surgical ethics column for SN in 2011. In the 33 columns that I have written since then, I have tried to focus on aspects of surgical practice that emphasize the ethical dimension. I have tried to write columns that would be of interest to practicing surgeons in any setting and not only to academic surgeons that practice in urban environments such as I practice in. This is the last column and thus the end of a chapter of my life and the beginning of a new one.

Over the last 7 years, I have been flattered by the comments from fellow surgeons who report that they actually read the column. I have always said that I wrote this column with the expectation that no one would actually read them. I have to confess that this is not completely true. As I wrote each column, I did so as though I was writing them for my father to read. My father, S. Peter Angelos, MD, FACS, was a general surgeon who spent his entire career practicing in the town of Plattsburgh, N.Y., where he grew up. My father’s practice was very different from mine. I work at an urban academic medical center where I have a very narrow subspecialty practice in endocrine surgery. My father had a small-town community practice of “bread and butter” general surgery. Yet, when he and I would talk about patients, the commonality of the relationship between a surgeon and a patient transcended these differences. I realize that in many ways, I wrote this column as a way of organizing my own thoughts and then presenting them to my father in the hopes that he would find them of some value.

For several years, I would send drafts of my column to my parents, and both my father and mother would read them and give me suggestions. Many of the earlier columns were changed for the better by their comments. In recent years, my father’s health declined and he was no longer able to give me comments. Nevertheless, I continued to compose them as though writing for him. Approximately 6 weeks ago, my father passed away. It has been sad for my mother and my entire family. We all realized that it was the end of one chapter of our lives and the start of a new one without my father.

I find the concept of “beginning a new chapter” to be an important one for surgeons to reflect upon. There are certain events, such as the death of a parent, that force us to think about the end of one phase of life and the beginning of another phase. However, the division of one’s experience into phases or chapters, is somewhat arbitrary. This past summer I became a patient and had surgery myself for the first time. I cannot help but think of that operation as the start of a new chapter for me. I am convinced that although all patients may not reflect upon surgery in the same way that I did, nevertheless, an operation is a dramatic event that most people remember for a long time. In this context, many people will see their interactions with their surgeon and their operation as the end of one chapter and the beginning of a new one.

In this context, it is critical for surgeons to be fully cognizant of the great impact that we may have on our patient’s internal narratives of their lives. When we operate on someone, we run the risk of that person’s functional status changing forever. We may be the means by which our patient is cured of cancer or suffers a debilitating complication. As surgeons, we therefore, occupy a potentially significant role in the trajectory of our patients’ lives. I believe that the relationship between a surgeon and a patient is distinctive and central in the narrative that so many patients create about their lives. It is essential that surgeons continue to appreciate the value of the quality of that relationship with our patients and the impact—potentially positive or negative—that it can have upon our patients.

Throughout medicine, in general, and in surgery in particular, one cannot go a week without hearing about the problem of burnout. Although there is no single cure for burnout, I do believe that paying attention to the ethical dimension of our interactions with our patients and the impact that surgery can have on their lives will go a long way to reducing the risks of burnout among surgeons.

In an era in which we are often pushed to increase RVUs at the expense of spending time with individual patients, we must not forget how significant our relationships with our patients can be. I believe that attention to this relationship will be beneficial to patients and also to us as we help our patients start new chapters in their lives.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Communication and consent

We knew that the case would be a difficult one. The patient was a man in his mid-40s who had several serious chronic conditions and was on high-dose steroids. He had been operated on 10 days earlier by one of my partners for a bowel obstruction and had required a resection of a small portion of the terminal ileum. Unfortunately, on the day after surgery, it became obvious that the patient needed a reexploration for bleeding. He had developed clear evidence of a significant anastomotic leak and had to be taken emergently back to the operating room.

His condition had been worsening during the day. We had booked the case in the OR but had been put off by a trauma emergency and a neurosurgical emergency. During the 3 hours of waiting to take him to the OR, the patient’s sister and mother came to the hospital and were now waiting with him in the preop area. I was on my way up to see him when my resident called. Despite the patient having signed an operative consent form a few hours earlier when we booked the case, he was now “declining” an operation. I was surprised. This man had undergone several operations in the last few years and two in the last 2 weeks. I arrived to find the patient stating that he did not want surgery. Lying in bed, he was adamant that he should not have surgery. The surgical resident who had spoken with the patient several times over the last few hours was also surprised. The patient’s family members were yelling that, of course, he wanted surgery and why would he change his mind.

This is a difficult situation since one of the central tenets of the ethical practice of surgery is to allow patients to make decisions about their own care. The right to make autonomous choices even extends to circumstances in which patients make what we might consider “bad” decisions. As long as the patient has the capacity to make an autonomous choice, he or she should have that choice respected.

This patient, who just a few hours ago had agreed to surgery, now seemed to have changed his mind. Although it can be frustrating, we do allow patients to change their minds. On the one hand, this was a straightforward case. The patient was refusing a potentially life-saving operation. Such a situation is never pleasant for a surgeon, but as long as the patient understands the risks, we respect such choices.

However, my resident made an astute observation. She pointed out that, when asked why he now did not want surgery, he replied that “this is all a movie – it’s not really happening.” The patient appeared to be oriented to person and place, but nevertheless, his reasoning seemed to have been altered. It appeared that this patient was no longer making sense because his underlying medical condition had deteriorated. We considered whether he was becoming septic and that this change in medical condition had rendered him unable to make an informed decision. My resident, who had discussed the operation with the patient several times, stated that the patient’s decision making seemed very different than even an hour ago. His family members agreed, stating that, up until a few minutes before, he was in favor of surgery. They pleaded with us to just take him into the operating room.

We considered our options. We could delay surgery and consult psychiatry to ask them to assess his competency. However, on a weekend night, this would likely take several hours. We considered the option of waiting in the preop area for the patient’s medical condition to further worsen. If he became overtly septic and lost consciousness, then we could readily turn to the family members – his surrogate decision makers – and ask them to consent to the procedure. Although this “by the book” approach might take away any worry that we were overriding an autonomous patient’s choice, we knew that it would unnecessarily expose him to greater operative risks. This option was not in his best interest and therefore not much of an option.

Ultimately, the surgical resident, the attending anesthesiologist, the family, and I decided that his decision to not have surgery at this moment was not consistent with his prior decisions, and he could provide no reason for changing his mind. We brought the patient into the operating room and explored him. He did have a large anastomotic leak with a large volume of enteric contents in the peritoneal cavity. He survived the operation and, not unexpectedly, required a long postoperative stay in the hospital. Once he was a few days out, I inquired about whether he was glad that he had surgery. He was quick to state his confidence that it had been the right choice for him. He did not even remember having ever refused the surgery.

Although this case raised many concerns for all of us involved in the patient’s care, one overriding lesson that came through to me. Informed consent should not be viewed as a solitary event, but a conversation. This patient had expressed his desire to have surgery multiple times to my surgical resident and to his family. Even though we should never take the position that patients cannot change their minds, we should carefully question those choices that are inconsistent with the prior discussions that have been undertaken. Good communication skills – including listening to the patient, understanding the patient’s reasoning, and reflecting on the entire conversation – are essential in obtaining informed consent.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

We knew that the case would be a difficult one. The patient was a man in his mid-40s who had several serious chronic conditions and was on high-dose steroids. He had been operated on 10 days earlier by one of my partners for a bowel obstruction and had required a resection of a small portion of the terminal ileum. Unfortunately, on the day after surgery, it became obvious that the patient needed a reexploration for bleeding. He had developed clear evidence of a significant anastomotic leak and had to be taken emergently back to the operating room.

His condition had been worsening during the day. We had booked the case in the OR but had been put off by a trauma emergency and a neurosurgical emergency. During the 3 hours of waiting to take him to the OR, the patient’s sister and mother came to the hospital and were now waiting with him in the preop area. I was on my way up to see him when my resident called. Despite the patient having signed an operative consent form a few hours earlier when we booked the case, he was now “declining” an operation. I was surprised. This man had undergone several operations in the last few years and two in the last 2 weeks. I arrived to find the patient stating that he did not want surgery. Lying in bed, he was adamant that he should not have surgery. The surgical resident who had spoken with the patient several times over the last few hours was also surprised. The patient’s family members were yelling that, of course, he wanted surgery and why would he change his mind.

This is a difficult situation since one of the central tenets of the ethical practice of surgery is to allow patients to make decisions about their own care. The right to make autonomous choices even extends to circumstances in which patients make what we might consider “bad” decisions. As long as the patient has the capacity to make an autonomous choice, he or she should have that choice respected.

This patient, who just a few hours ago had agreed to surgery, now seemed to have changed his mind. Although it can be frustrating, we do allow patients to change their minds. On the one hand, this was a straightforward case. The patient was refusing a potentially life-saving operation. Such a situation is never pleasant for a surgeon, but as long as the patient understands the risks, we respect such choices.

However, my resident made an astute observation. She pointed out that, when asked why he now did not want surgery, he replied that “this is all a movie – it’s not really happening.” The patient appeared to be oriented to person and place, but nevertheless, his reasoning seemed to have been altered. It appeared that this patient was no longer making sense because his underlying medical condition had deteriorated. We considered whether he was becoming septic and that this change in medical condition had rendered him unable to make an informed decision. My resident, who had discussed the operation with the patient several times, stated that the patient’s decision making seemed very different than even an hour ago. His family members agreed, stating that, up until a few minutes before, he was in favor of surgery. They pleaded with us to just take him into the operating room.

We considered our options. We could delay surgery and consult psychiatry to ask them to assess his competency. However, on a weekend night, this would likely take several hours. We considered the option of waiting in the preop area for the patient’s medical condition to further worsen. If he became overtly septic and lost consciousness, then we could readily turn to the family members – his surrogate decision makers – and ask them to consent to the procedure. Although this “by the book” approach might take away any worry that we were overriding an autonomous patient’s choice, we knew that it would unnecessarily expose him to greater operative risks. This option was not in his best interest and therefore not much of an option.

Ultimately, the surgical resident, the attending anesthesiologist, the family, and I decided that his decision to not have surgery at this moment was not consistent with his prior decisions, and he could provide no reason for changing his mind. We brought the patient into the operating room and explored him. He did have a large anastomotic leak with a large volume of enteric contents in the peritoneal cavity. He survived the operation and, not unexpectedly, required a long postoperative stay in the hospital. Once he was a few days out, I inquired about whether he was glad that he had surgery. He was quick to state his confidence that it had been the right choice for him. He did not even remember having ever refused the surgery.

Although this case raised many concerns for all of us involved in the patient’s care, one overriding lesson that came through to me. Informed consent should not be viewed as a solitary event, but a conversation. This patient had expressed his desire to have surgery multiple times to my surgical resident and to his family. Even though we should never take the position that patients cannot change their minds, we should carefully question those choices that are inconsistent with the prior discussions that have been undertaken. Good communication skills – including listening to the patient, understanding the patient’s reasoning, and reflecting on the entire conversation – are essential in obtaining informed consent.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

We knew that the case would be a difficult one. The patient was a man in his mid-40s who had several serious chronic conditions and was on high-dose steroids. He had been operated on 10 days earlier by one of my partners for a bowel obstruction and had required a resection of a small portion of the terminal ileum. Unfortunately, on the day after surgery, it became obvious that the patient needed a reexploration for bleeding. He had developed clear evidence of a significant anastomotic leak and had to be taken emergently back to the operating room.

His condition had been worsening during the day. We had booked the case in the OR but had been put off by a trauma emergency and a neurosurgical emergency. During the 3 hours of waiting to take him to the OR, the patient’s sister and mother came to the hospital and were now waiting with him in the preop area. I was on my way up to see him when my resident called. Despite the patient having signed an operative consent form a few hours earlier when we booked the case, he was now “declining” an operation. I was surprised. This man had undergone several operations in the last few years and two in the last 2 weeks. I arrived to find the patient stating that he did not want surgery. Lying in bed, he was adamant that he should not have surgery. The surgical resident who had spoken with the patient several times over the last few hours was also surprised. The patient’s family members were yelling that, of course, he wanted surgery and why would he change his mind.

This is a difficult situation since one of the central tenets of the ethical practice of surgery is to allow patients to make decisions about their own care. The right to make autonomous choices even extends to circumstances in which patients make what we might consider “bad” decisions. As long as the patient has the capacity to make an autonomous choice, he or she should have that choice respected.

This patient, who just a few hours ago had agreed to surgery, now seemed to have changed his mind. Although it can be frustrating, we do allow patients to change their minds. On the one hand, this was a straightforward case. The patient was refusing a potentially life-saving operation. Such a situation is never pleasant for a surgeon, but as long as the patient understands the risks, we respect such choices.

However, my resident made an astute observation. She pointed out that, when asked why he now did not want surgery, he replied that “this is all a movie – it’s not really happening.” The patient appeared to be oriented to person and place, but nevertheless, his reasoning seemed to have been altered. It appeared that this patient was no longer making sense because his underlying medical condition had deteriorated. We considered whether he was becoming septic and that this change in medical condition had rendered him unable to make an informed decision. My resident, who had discussed the operation with the patient several times, stated that the patient’s decision making seemed very different than even an hour ago. His family members agreed, stating that, up until a few minutes before, he was in favor of surgery. They pleaded with us to just take him into the operating room.

We considered our options. We could delay surgery and consult psychiatry to ask them to assess his competency. However, on a weekend night, this would likely take several hours. We considered the option of waiting in the preop area for the patient’s medical condition to further worsen. If he became overtly septic and lost consciousness, then we could readily turn to the family members – his surrogate decision makers – and ask them to consent to the procedure. Although this “by the book” approach might take away any worry that we were overriding an autonomous patient’s choice, we knew that it would unnecessarily expose him to greater operative risks. This option was not in his best interest and therefore not much of an option.

Ultimately, the surgical resident, the attending anesthesiologist, the family, and I decided that his decision to not have surgery at this moment was not consistent with his prior decisions, and he could provide no reason for changing his mind. We brought the patient into the operating room and explored him. He did have a large anastomotic leak with a large volume of enteric contents in the peritoneal cavity. He survived the operation and, not unexpectedly, required a long postoperative stay in the hospital. Once he was a few days out, I inquired about whether he was glad that he had surgery. He was quick to state his confidence that it had been the right choice for him. He did not even remember having ever refused the surgery.

Although this case raised many concerns for all of us involved in the patient’s care, one overriding lesson that came through to me. Informed consent should not be viewed as a solitary event, but a conversation. This patient had expressed his desire to have surgery multiple times to my surgical resident and to his family. Even though we should never take the position that patients cannot change their minds, we should carefully question those choices that are inconsistent with the prior discussions that have been undertaken. Good communication skills – including listening to the patient, understanding the patient’s reasoning, and reflecting on the entire conversation – are essential in obtaining informed consent.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The Right Choice? Modifiable risk factors and surgical decision making

In the July 26, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Ira L. Leeds, MD, David T. Efron, MD, FACS, and Lisa S. Lehmann, MD, raise the important issue of how to proceed when a patient has an indication for surgery and wants the surgery, but the patient has modifiable risk factors that make the likelihood of surgical complications high.1 Specifically, the authors describe a 45-year-old woman with morbid obesity and chronic opioid dependency who presented with a large incisional hernia. The patient suffers from debilitating pain and nausea that has been attributed to her hernia. She is homebound and is seeking a third opinion on repair of the hernia. She has smoked for 30 years and continues to do so after prior unsuccessful attempts to quit. She has been turned down previously by two surgeons who reportedly felt she was too high risk. Application of an all-procedure risk calculator has shown a 38% higher than average risk of a complication with an expected length of stay 80% longer than average.

I commend the authors for raising this set of issues for consideration. As surgeons, we routinely make decisions about what operations we recommend to patients based on the risks of the operation. However, we also allow significant latitude for patients to make individual decisions about assuming greater or lesser risks. If the patient’s surgical risks could be reduced by her stopping smoking and losing weight, should the surgeon insist upon those things being done before being willing to operate on the patient? The answer to this question depends on the perspective that one takes in viewing this case. If the surgeon’s relationship with the patient is primary and the potential benefit of surgery is clearly present, then one could view the considerations of lower public ranking and added costs to society as irrelevant. However, if a surgeon views his or her role as not only advocating for their patient, but also being a steward of societal resources, then the added resources necessary to get this patient safely through the operation are critically important to consider.

In order to come to a decision for this individual patient, the authors argue in favor of greater patient education of the surgical risk so the patient can appreciate the importance of modifying the risky behaviors prior to surgery. This concept of shared decision making with patients is certainly important and should be encouraged in any surgeon-patient interaction around a possible surgical intervention. The authors also note the importance of ensuring an alignment of values between the patient and the surgeon in why the operation might be undertaken. These suggestions are excellent and undoubtedly would lead to better relationships between surgeons and patients and also likely better decisions about when to operate.

My primary concern with the authors’ suggestions occurs when the authors encourage surgical professional societies to “develop consistent practice guidelines without partiality to any particular patient.” The authors make the claim that, in a complex case in which it is difficult to decide what is best for the patient, we would benefit from having more guidelines about what modifiable risk factors should preclude surgery.

I worry that the appeal to guidelines is too often an appeal to ignore the individual aspects of a patient’s condition and the impact that the condition has on a patient’s life. Rather than saying, “What we need is more guidelines,” I would much prefer we emphasize the need for more communication between surgeons and patients about the risks of surgery and the implications of recovery on the patient’s quality of life. Although there is nothing detrimental to gathering data about the impact of modifiable risks on surgical outcomes, I am concerned that guidelines may become viewed as parameters of “good” patient care. We all know that no guideline can account for all the individual values and goals a patient may have and, thus, we ought not use guidelines to shield us from the complex individual decision making that as surgeons we should engage in with each of our patients.

Reference

1. Leeds IL et al. Surgical gatekeeping – modifiable risk factors and ethical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1802079.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

In the July 26, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Ira L. Leeds, MD, David T. Efron, MD, FACS, and Lisa S. Lehmann, MD, raise the important issue of how to proceed when a patient has an indication for surgery and wants the surgery, but the patient has modifiable risk factors that make the likelihood of surgical complications high.1 Specifically, the authors describe a 45-year-old woman with morbid obesity and chronic opioid dependency who presented with a large incisional hernia. The patient suffers from debilitating pain and nausea that has been attributed to her hernia. She is homebound and is seeking a third opinion on repair of the hernia. She has smoked for 30 years and continues to do so after prior unsuccessful attempts to quit. She has been turned down previously by two surgeons who reportedly felt she was too high risk. Application of an all-procedure risk calculator has shown a 38% higher than average risk of a complication with an expected length of stay 80% longer than average.

I commend the authors for raising this set of issues for consideration. As surgeons, we routinely make decisions about what operations we recommend to patients based on the risks of the operation. However, we also allow significant latitude for patients to make individual decisions about assuming greater or lesser risks. If the patient’s surgical risks could be reduced by her stopping smoking and losing weight, should the surgeon insist upon those things being done before being willing to operate on the patient? The answer to this question depends on the perspective that one takes in viewing this case. If the surgeon’s relationship with the patient is primary and the potential benefit of surgery is clearly present, then one could view the considerations of lower public ranking and added costs to society as irrelevant. However, if a surgeon views his or her role as not only advocating for their patient, but also being a steward of societal resources, then the added resources necessary to get this patient safely through the operation are critically important to consider.

In order to come to a decision for this individual patient, the authors argue in favor of greater patient education of the surgical risk so the patient can appreciate the importance of modifying the risky behaviors prior to surgery. This concept of shared decision making with patients is certainly important and should be encouraged in any surgeon-patient interaction around a possible surgical intervention. The authors also note the importance of ensuring an alignment of values between the patient and the surgeon in why the operation might be undertaken. These suggestions are excellent and undoubtedly would lead to better relationships between surgeons and patients and also likely better decisions about when to operate.

My primary concern with the authors’ suggestions occurs when the authors encourage surgical professional societies to “develop consistent practice guidelines without partiality to any particular patient.” The authors make the claim that, in a complex case in which it is difficult to decide what is best for the patient, we would benefit from having more guidelines about what modifiable risk factors should preclude surgery.

I worry that the appeal to guidelines is too often an appeal to ignore the individual aspects of a patient’s condition and the impact that the condition has on a patient’s life. Rather than saying, “What we need is more guidelines,” I would much prefer we emphasize the need for more communication between surgeons and patients about the risks of surgery and the implications of recovery on the patient’s quality of life. Although there is nothing detrimental to gathering data about the impact of modifiable risks on surgical outcomes, I am concerned that guidelines may become viewed as parameters of “good” patient care. We all know that no guideline can account for all the individual values and goals a patient may have and, thus, we ought not use guidelines to shield us from the complex individual decision making that as surgeons we should engage in with each of our patients.

Reference

1. Leeds IL et al. Surgical gatekeeping – modifiable risk factors and ethical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1802079.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

In the July 26, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Ira L. Leeds, MD, David T. Efron, MD, FACS, and Lisa S. Lehmann, MD, raise the important issue of how to proceed when a patient has an indication for surgery and wants the surgery, but the patient has modifiable risk factors that make the likelihood of surgical complications high.1 Specifically, the authors describe a 45-year-old woman with morbid obesity and chronic opioid dependency who presented with a large incisional hernia. The patient suffers from debilitating pain and nausea that has been attributed to her hernia. She is homebound and is seeking a third opinion on repair of the hernia. She has smoked for 30 years and continues to do so after prior unsuccessful attempts to quit. She has been turned down previously by two surgeons who reportedly felt she was too high risk. Application of an all-procedure risk calculator has shown a 38% higher than average risk of a complication with an expected length of stay 80% longer than average.

I commend the authors for raising this set of issues for consideration. As surgeons, we routinely make decisions about what operations we recommend to patients based on the risks of the operation. However, we also allow significant latitude for patients to make individual decisions about assuming greater or lesser risks. If the patient’s surgical risks could be reduced by her stopping smoking and losing weight, should the surgeon insist upon those things being done before being willing to operate on the patient? The answer to this question depends on the perspective that one takes in viewing this case. If the surgeon’s relationship with the patient is primary and the potential benefit of surgery is clearly present, then one could view the considerations of lower public ranking and added costs to society as irrelevant. However, if a surgeon views his or her role as not only advocating for their patient, but also being a steward of societal resources, then the added resources necessary to get this patient safely through the operation are critically important to consider.

In order to come to a decision for this individual patient, the authors argue in favor of greater patient education of the surgical risk so the patient can appreciate the importance of modifying the risky behaviors prior to surgery. This concept of shared decision making with patients is certainly important and should be encouraged in any surgeon-patient interaction around a possible surgical intervention. The authors also note the importance of ensuring an alignment of values between the patient and the surgeon in why the operation might be undertaken. These suggestions are excellent and undoubtedly would lead to better relationships between surgeons and patients and also likely better decisions about when to operate.

My primary concern with the authors’ suggestions occurs when the authors encourage surgical professional societies to “develop consistent practice guidelines without partiality to any particular patient.” The authors make the claim that, in a complex case in which it is difficult to decide what is best for the patient, we would benefit from having more guidelines about what modifiable risk factors should preclude surgery.

I worry that the appeal to guidelines is too often an appeal to ignore the individual aspects of a patient’s condition and the impact that the condition has on a patient’s life. Rather than saying, “What we need is more guidelines,” I would much prefer we emphasize the need for more communication between surgeons and patients about the risks of surgery and the implications of recovery on the patient’s quality of life. Although there is nothing detrimental to gathering data about the impact of modifiable risks on surgical outcomes, I am concerned that guidelines may become viewed as parameters of “good” patient care. We all know that no guideline can account for all the individual values and goals a patient may have and, thus, we ought not use guidelines to shield us from the complex individual decision making that as surgeons we should engage in with each of our patients.

Reference

1. Leeds IL et al. Surgical gatekeeping – modifiable risk factors and ethical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1802079.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The right choice? Surgery “offered” or “recommended”?

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The right choice? Surgeons, confidence, and humility

It started as an offhand comment. The patient had been on the medicine service for over a week before developing acute appendicitis with an abscess and requiring an emergency open appendectomy. He was a 68-year-old man who had longstanding medical issues that had given him many opportunities to interact with physicians in the prior few years.

On the second morning after surgery, a new team of surgical residents was rounding on him. The chief resident led the group of residents and students into the patient’s room and introduced himself as being part of the surgical team. The patient smiled and stated that he knew this was a group of surgeons. When asked why, the patient reported that he could always tell when surgeons enter the room. “You enter with an air of bravado and arrogance that the medical doctors do not exude.” The surgical residents commented on this fact to me later when I rounded on the patient, and it prompted discussion of the potential positives and negatives of confidence in surgical practice.

There is no doubt in my mind that in order to be willing to put a patient through an operation, surgeons must be confident in their skills. Surgery never achieves its benefit for patients without first causing the patient some harm. Any operation requires that the surgeon impose a violent act on the patient that, in any other context, would be illegal. In order to do such things to patients, surgeons must have a high degree of confidence.

Patients also appreciate a confident surgeon. Over the years, I have known many technically excellent surgeons who have never been as busy as they might have been because they were unable to express confidence to their patients. The opposite, however, is also true. There are surgeons who become so overconfident in their abilities that they become reckless in recommending high-risk operations to patients.

Given that patients expect their surgeons to have confidence and surgeons actually need to be confident in order to be successful, it might be surprising that the important attribute of self-confidence does not more frequently spill over into overbearing arrogance. Perhaps the most important temporizing of surgeon overconfidence is the unfortunate inevitable consequence of surgery that complications happen to even the best surgeons. We all know that the central question of the M & M conference is, “What could you have done differently?” Whether this question is answered publicly or only in the mind of the surgeon, the contemplation of the decisions made, and their consequences, is essential for each surgeon to consider in the face of every complication.

Much as the public should want surgeons to be confident, but not too confident, they should also want their surgeons to take complications seriously, but not too seriously. It is helpful for a surgeon to think about making a different choice in the future. But it would not be helpful if, in the face of a bad outcome, a surgeon decides that he or she can no longer perform surgery.

This balance between lack of confidence and overconfidence, and between thoughtful introspection and paralyzing fear of future complications, is challenging to teach to surgical residents and fellows. Part of the challenge is that often surgical faculty do not verbalize the challenges that we face in this realm. The perfect combination of confidence and humility is something that few of us have identified in our own lives, let alone are prepared to teach it authoritatively to others. Nevertheless, teaching the next generation of surgeons to recognize the tension between confidence and humility is worthwhile. And like their elders, they may well discover that achieving the right balance is a lifelong pursuit.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

It started as an offhand comment. The patient had been on the medicine service for over a week before developing acute appendicitis with an abscess and requiring an emergency open appendectomy. He was a 68-year-old man who had longstanding medical issues that had given him many opportunities to interact with physicians in the prior few years.

On the second morning after surgery, a new team of surgical residents was rounding on him. The chief resident led the group of residents and students into the patient’s room and introduced himself as being part of the surgical team. The patient smiled and stated that he knew this was a group of surgeons. When asked why, the patient reported that he could always tell when surgeons enter the room. “You enter with an air of bravado and arrogance that the medical doctors do not exude.” The surgical residents commented on this fact to me later when I rounded on the patient, and it prompted discussion of the potential positives and negatives of confidence in surgical practice.

There is no doubt in my mind that in order to be willing to put a patient through an operation, surgeons must be confident in their skills. Surgery never achieves its benefit for patients without first causing the patient some harm. Any operation requires that the surgeon impose a violent act on the patient that, in any other context, would be illegal. In order to do such things to patients, surgeons must have a high degree of confidence.

Patients also appreciate a confident surgeon. Over the years, I have known many technically excellent surgeons who have never been as busy as they might have been because they were unable to express confidence to their patients. The opposite, however, is also true. There are surgeons who become so overconfident in their abilities that they become reckless in recommending high-risk operations to patients.

Given that patients expect their surgeons to have confidence and surgeons actually need to be confident in order to be successful, it might be surprising that the important attribute of self-confidence does not more frequently spill over into overbearing arrogance. Perhaps the most important temporizing of surgeon overconfidence is the unfortunate inevitable consequence of surgery that complications happen to even the best surgeons. We all know that the central question of the M & M conference is, “What could you have done differently?” Whether this question is answered publicly or only in the mind of the surgeon, the contemplation of the decisions made, and their consequences, is essential for each surgeon to consider in the face of every complication.

Much as the public should want surgeons to be confident, but not too confident, they should also want their surgeons to take complications seriously, but not too seriously. It is helpful for a surgeon to think about making a different choice in the future. But it would not be helpful if, in the face of a bad outcome, a surgeon decides that he or she can no longer perform surgery.

This balance between lack of confidence and overconfidence, and between thoughtful introspection and paralyzing fear of future complications, is challenging to teach to surgical residents and fellows. Part of the challenge is that often surgical faculty do not verbalize the challenges that we face in this realm. The perfect combination of confidence and humility is something that few of us have identified in our own lives, let alone are prepared to teach it authoritatively to others. Nevertheless, teaching the next generation of surgeons to recognize the tension between confidence and humility is worthwhile. And like their elders, they may well discover that achieving the right balance is a lifelong pursuit.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

It started as an offhand comment. The patient had been on the medicine service for over a week before developing acute appendicitis with an abscess and requiring an emergency open appendectomy. He was a 68-year-old man who had longstanding medical issues that had given him many opportunities to interact with physicians in the prior few years.

On the second morning after surgery, a new team of surgical residents was rounding on him. The chief resident led the group of residents and students into the patient’s room and introduced himself as being part of the surgical team. The patient smiled and stated that he knew this was a group of surgeons. When asked why, the patient reported that he could always tell when surgeons enter the room. “You enter with an air of bravado and arrogance that the medical doctors do not exude.” The surgical residents commented on this fact to me later when I rounded on the patient, and it prompted discussion of the potential positives and negatives of confidence in surgical practice.

There is no doubt in my mind that in order to be willing to put a patient through an operation, surgeons must be confident in their skills. Surgery never achieves its benefit for patients without first causing the patient some harm. Any operation requires that the surgeon impose a violent act on the patient that, in any other context, would be illegal. In order to do such things to patients, surgeons must have a high degree of confidence.

Patients also appreciate a confident surgeon. Over the years, I have known many technically excellent surgeons who have never been as busy as they might have been because they were unable to express confidence to their patients. The opposite, however, is also true. There are surgeons who become so overconfident in their abilities that they become reckless in recommending high-risk operations to patients.

Given that patients expect their surgeons to have confidence and surgeons actually need to be confident in order to be successful, it might be surprising that the important attribute of self-confidence does not more frequently spill over into overbearing arrogance. Perhaps the most important temporizing of surgeon overconfidence is the unfortunate inevitable consequence of surgery that complications happen to even the best surgeons. We all know that the central question of the M & M conference is, “What could you have done differently?” Whether this question is answered publicly or only in the mind of the surgeon, the contemplation of the decisions made, and their consequences, is essential for each surgeon to consider in the face of every complication.

Much as the public should want surgeons to be confident, but not too confident, they should also want their surgeons to take complications seriously, but not too seriously. It is helpful for a surgeon to think about making a different choice in the future. But it would not be helpful if, in the face of a bad outcome, a surgeon decides that he or she can no longer perform surgery.

This balance between lack of confidence and overconfidence, and between thoughtful introspection and paralyzing fear of future complications, is challenging to teach to surgical residents and fellows. Part of the challenge is that often surgical faculty do not verbalize the challenges that we face in this realm. The perfect combination of confidence and humility is something that few of us have identified in our own lives, let alone are prepared to teach it authoritatively to others. Nevertheless, teaching the next generation of surgeons to recognize the tension between confidence and humility is worthwhile. And like their elders, they may well discover that achieving the right balance is a lifelong pursuit.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The Right Choice? Surgeons, confidence, and humility

It started as an offhand comment. The patient had been on the medicine service for over a week before developing acute appendicitis with an abscess requiring an emergency open appendectomy. He was a 68-year-old man who had longstanding medical issues that had given him many opportunities to interact with physicians in the prior few years.

On the second morning after surgery, a new team of surgical residents was rounding on him. The chief resident led the group of residents and students into the patient’s room and introduced himself as being part of the surgical team. The patient smiled and stated that he knew this was a group of surgeons. When asked why, the patient reported that he could always tell when surgeons enter the room. “You enter with an air of bravado and arrogance that the medical doctors do not exude.” The surgical residents commented on this fact to me later when I rounded on the patient, and it prompted discussion of the potential positives and negatives of confidence in surgical practice.

Most successful surgeons express a level of confidence in their abilities which often exceeds that of many other physicians. Such observations have led to the joke that “surgeons are often wrong, but never in doubt.” The question is whether the expression of confidence in one’s abilities as a surgeon is a requirement of a surgeon or simply a common characteristic for many people who choose to go into the field of surgery.

There is no doubt in my mind that in order to be willing to put a patient through an operation, surgeons must be confident in their skills. Surgery never achieves its benefit for patients without first causing the patient some harm. Any operation requires that the surgeon impose a violent act on the patient that, in any other context, would be illegal. To do such things to patients, surgeons must have a high degree of confidence.

Patients also appreciate a confident surgeon. Over the years, I have known many technically excellent surgeons who have never been as busy as they might have because of their inability to express confidence to their patients. The opposite, however, is also true. There are surgeons who become so overconfident in their abilities that they become reckless in recommending high-risk operations to patients.

Given that patients expect their surgeons to be confident and surgeons actually need to be confident to be successful, it might be surprising that the important attribute of self-confidence does not more frequently spill over into overbearing arrogance. Perhaps the most important temporizing of surgeon overconfidence is the unfortunate inevitable consequence of surgery that complications happen to even the best surgeons. We all know that the central question of the M & M conference is, “What could you have done differently?” Whether this question is answered publicly or only in the mind of the surgeon, the contemplation of the decisions made, and their consequences, is essential for each surgeon to consider in the face of every complication.

Much as the public should want surgeons to be confident, but not too confident, they should also want their surgeons to take complications seriously, but not too seriously. It is helpful for a surgeon to think about making a different choice in the future. But it would not be helpful if, in the face of a bad outcome, a surgeon decides that he or she can no longer perform surgery.

This balance between lack of confidence and overconfidence, and between thoughtful introspection and paralyzing fear of future complications, is challenging to teach to surgical residents and fellows. Part of the challenge is that often surgical faculty do not verbalize the challenges that we face in this realm. The perfect combination of confidence and humility is something that few of us have identified in our own lives, let alone are prepared to teach authoritatively to others. Nevertheless, teaching the next generation of surgeons to recognize the tension between confidence and humility is worthwhile. And like their elders, they may well discover that achieving the right balance is a lifelong pursuit.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics; chief, endocrine surgery; and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

It started as an offhand comment. The patient had been on the medicine service for over a week before developing acute appendicitis with an abscess requiring an emergency open appendectomy. He was a 68-year-old man who had longstanding medical issues that had given him many opportunities to interact with physicians in the prior few years.

On the second morning after surgery, a new team of surgical residents was rounding on him. The chief resident led the group of residents and students into the patient’s room and introduced himself as being part of the surgical team. The patient smiled and stated that he knew this was a group of surgeons. When asked why, the patient reported that he could always tell when surgeons enter the room. “You enter with an air of bravado and arrogance that the medical doctors do not exude.” The surgical residents commented on this fact to me later when I rounded on the patient, and it prompted discussion of the potential positives and negatives of confidence in surgical practice.

Most successful surgeons express a level of confidence in their abilities which often exceeds that of many other physicians. Such observations have led to the joke that “surgeons are often wrong, but never in doubt.” The question is whether the expression of confidence in one’s abilities as a surgeon is a requirement of a surgeon or simply a common characteristic for many people who choose to go into the field of surgery.

There is no doubt in my mind that in order to be willing to put a patient through an operation, surgeons must be confident in their skills. Surgery never achieves its benefit for patients without first causing the patient some harm. Any operation requires that the surgeon impose a violent act on the patient that, in any other context, would be illegal. To do such things to patients, surgeons must have a high degree of confidence.

Patients also appreciate a confident surgeon. Over the years, I have known many technically excellent surgeons who have never been as busy as they might have because of their inability to express confidence to their patients. The opposite, however, is also true. There are surgeons who become so overconfident in their abilities that they become reckless in recommending high-risk operations to patients.

Given that patients expect their surgeons to be confident and surgeons actually need to be confident to be successful, it might be surprising that the important attribute of self-confidence does not more frequently spill over into overbearing arrogance. Perhaps the most important temporizing of surgeon overconfidence is the unfortunate inevitable consequence of surgery that complications happen to even the best surgeons. We all know that the central question of the M & M conference is, “What could you have done differently?” Whether this question is answered publicly or only in the mind of the surgeon, the contemplation of the decisions made, and their consequences, is essential for each surgeon to consider in the face of every complication.

Much as the public should want surgeons to be confident, but not too confident, they should also want their surgeons to take complications seriously, but not too seriously. It is helpful for a surgeon to think about making a different choice in the future. But it would not be helpful if, in the face of a bad outcome, a surgeon decides that he or she can no longer perform surgery.