User login

Does niacin decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CVD patients?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

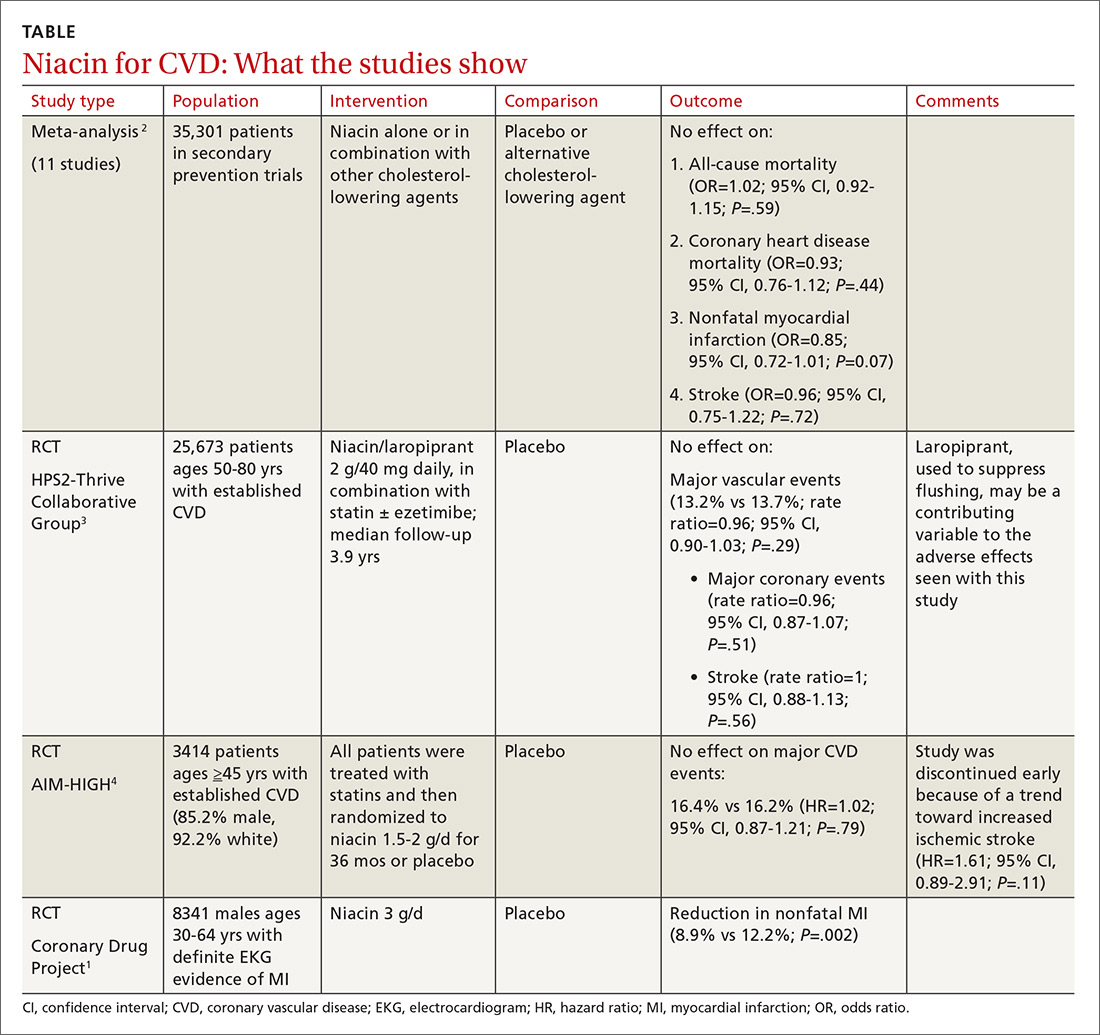

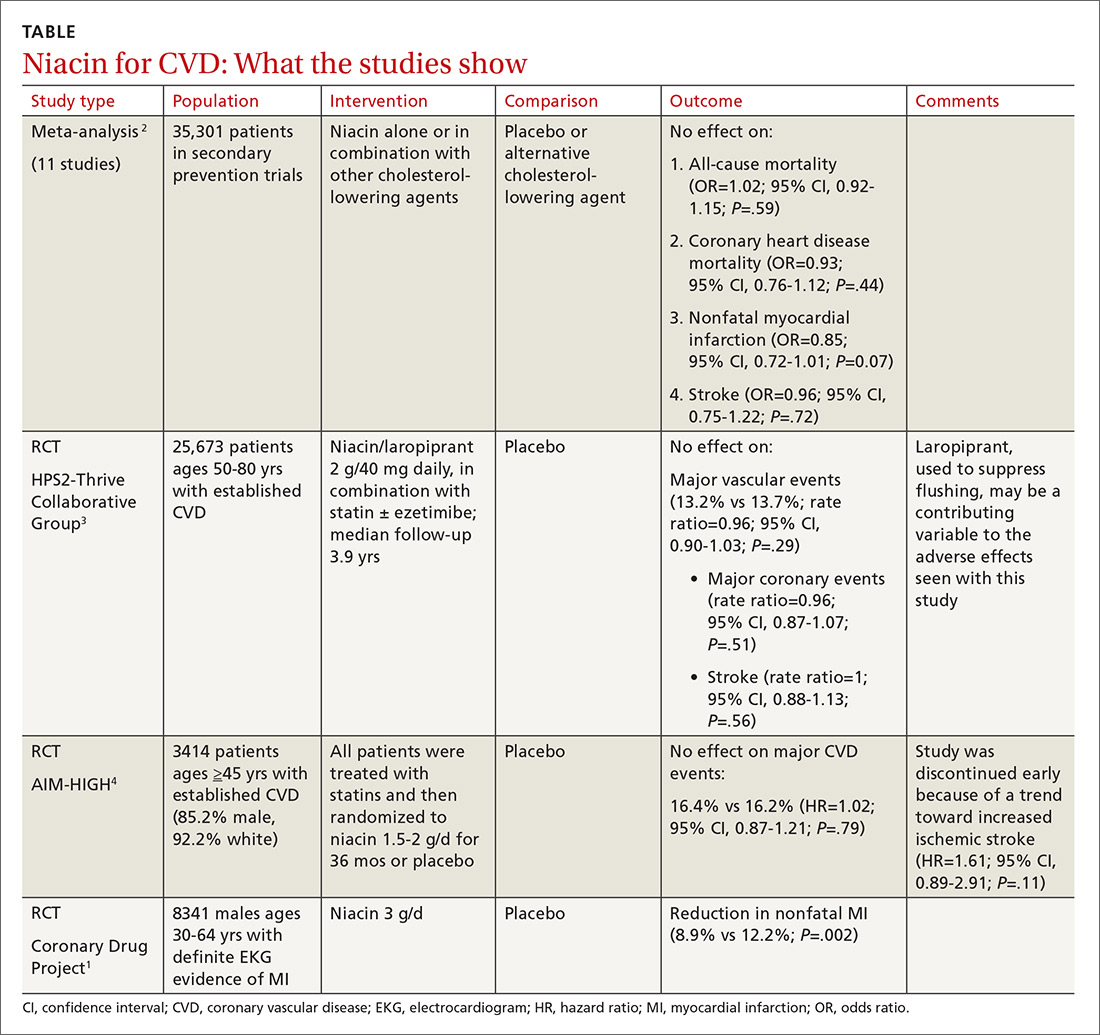

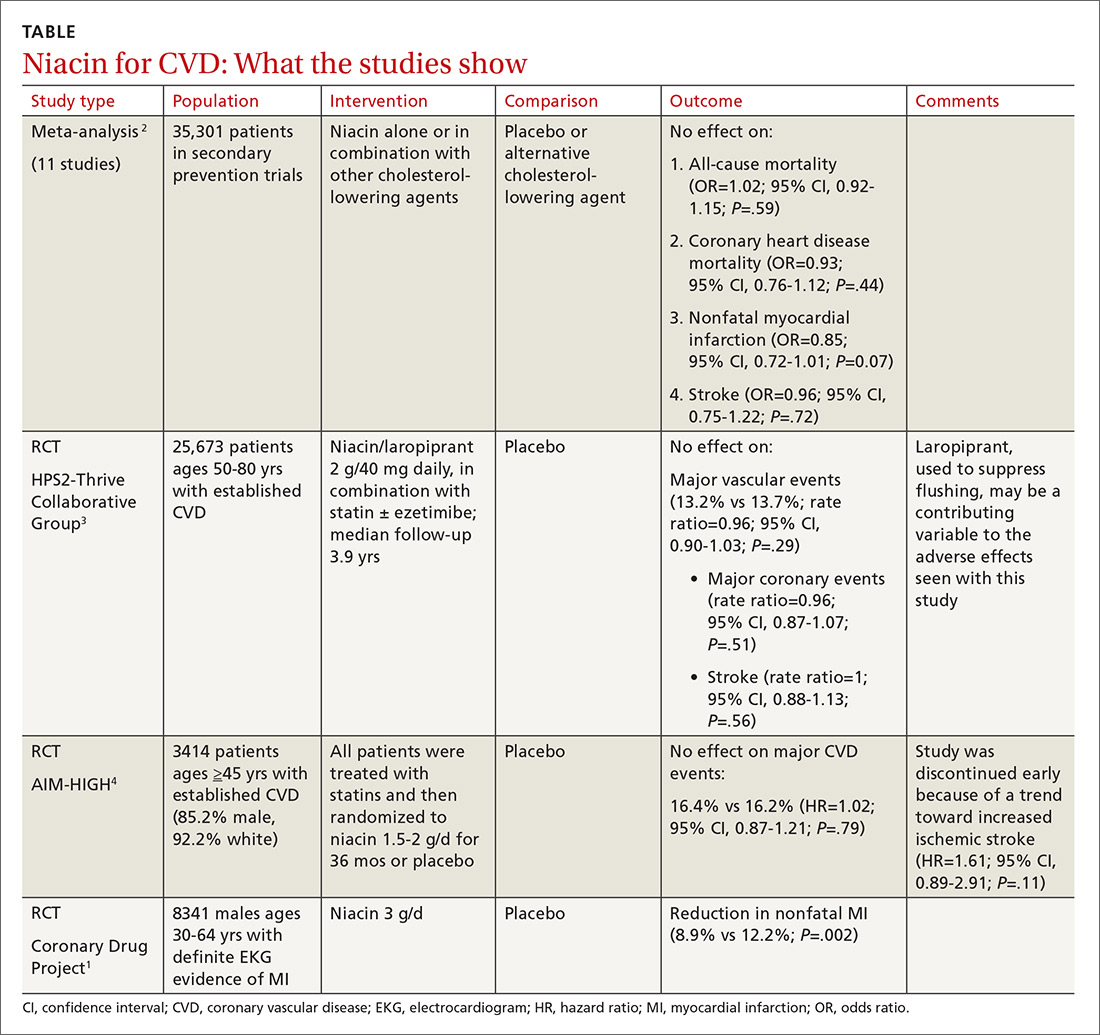

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE BASED ANSWER:

No. Niacin doesn’t reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity or mortality in patients with established disease (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and subsequent large RCTs).

Niacin may be considered as monotherapy for patients intolerant of statins (SOR: B, one well-done RCT).