User login

How can we effectively treat stress urinary incontinence without drugs or surgery?

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

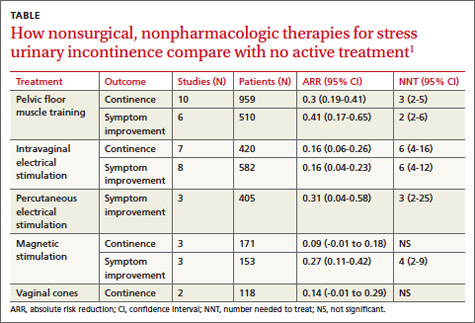

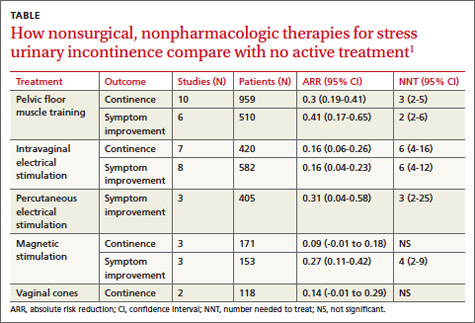

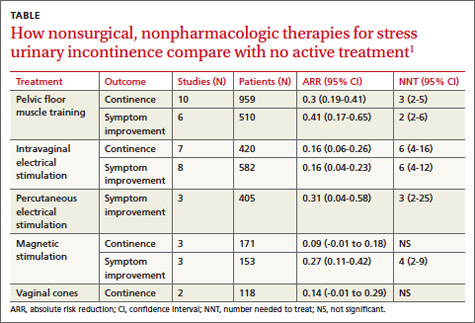

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Which drugs work best for early Parkinson’s disease?

LEVODOPA/CARBIDOPA is the most effective medical therapy for Parkinson’s disease, but it’s associated with dyskinesia (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, Cochrane reviews and randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Treating early Parkinson’s disease with dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine can improve symptoms (SOR: B, Cochrane reviews, RCTs with heterogeneity).

Evidence summary

Levodopa/carbidopa is the most commonly prescribed medication for Parkinson’s disease. Although its efficacy is established, it can cause dyskinesia and dystonia.1 Recent studies (TABLE) have evaluated the use of other medications early in the course of Parkinson’s disease in hopes of delaying the waning effectiveness of levodopa over time.

TABLE

Medications commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease

| Medication class brand (generic)9 | Advantages | Disadvantages | Approximate monthly cost at usual dosage (in US $) for generic (brand name prices cited if no generic available)10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbidopa/levodopa Sinemet (carbidopa/ levodopa) Sinemet CR (carbidopa/levodopa controlled-release) | First-line therapy; most effective at improving motor disability1 | Dyskinesia, dystonia, hallucinations No documented benefit of long-acting form1,8 | $34.99-$101.98 $80.99-$295.97 (Highly variable due to dose range) |

| COMT inhibitor Comtan (entacapone) Stalevo (carbidopa/levodopa/entacapone) | Augments levodopa, may improve activities of daily living6 | Same side effects as above plus possible increased nausea, vomiting, diarrhea6 Possible increased cardiovascular risk and prostate cancer | $310.97-$414.62 $318.00-$1043.97 |

| Dopamine agonist Mirapex (pramipexole) Requip (ropinirole) Parlodel (bromocriptine) | Reduced dyskinesias, dystonia, and motor complications2 | Nausea, dizziness, constipation, somnolence, hallucinations, edema2 | $239.99 $71.99-$143.98 $385.97-$1133.92 |

| MAO-B inhibitor Eldepryl (selegiline) | Mild improved motor symptoms of disease, decreased motor fluctuations of treatment, possible “levosparing effect”5 | Limited efficacy and multiple adverse effects leading to high dropout rate; not recommended by Cochrane review5 | $101.99 |

| Anticholinergic Cogentin (benztropine mesylate) | Improved symptoms, mostly tremor7 | Confusion, memory loss, hallucinations, restlessness; contraindicated in dementia7 | $13.99-$22.99 |

| Other Symmetrel (amantadine) | No good updated studies, unproven long-term benefit, nausea, dizziness, insomnia, can cause psychosis9 | $43.17 | |

| COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase type B. | |||

Dopamine agonists: Dyskinesia reduction, but at a price

A Cochrane review of 29 trials with 5247 patients compared dopamine agonists with levodopa.2 Levodopa controlled symptoms better than dopamine agonists, but inconsistent data reporting prevented quantifying this result.

Compared with the group taking levodopa, patients taking dopamine agonists demonstrated a significant reduction in dyskinesia (odds ratio [OR]=0.45; 95% CI, 0.37-0.54), dystonia (OR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.51-0.81), and motor fluctuations (OR= 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.87).

However, patients taking dopamine agonists with or without levodopa experienced significantly more adverse effects than patients taking levodopa alone. Side effects included increased edema (OR=3.68; 95% CI, 2.62-5.18), somnolence (OR=1.49; 95% CI, 1.12-2.00), constipation (OR=1.59; 95% CI, 1.11-2.28), dizziness (OR=1.45; 95% CI, 1.09-1.92), hallucinations (OR=1.69; 95% CI, 1.13-2.52), and nausea (OR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.05-1.66). Patients treated with dopamine agonists were also significantly more likely to discontinue treatment because of adverse events (OR=2.49; 95% CI, 2.08-2.98; P<.00001).

Bromocriptine studies hampered by poor quality

Two Cochrane reviews specifically evaluated the dopamine agonist bromocriptine.3,4 The first focused on 6 head-to-head trials with levodopa that enrolled 850 patients.3 The studies were of poor quality, marred by methodological flaws and clinical heterogeneity. Problems included inadequate power, high variability in study duration (23 weeks to 5 years), differences in reporting, and lack of description of the randomization method in 3 of the 6 trials. Although bromocriptine showed a trend toward lower incidence of motor complications, many patients dropped out of the studies because of increased non-motor adverse effects and inadequate response to treatment.

The second review, of 7 trials with a total of 1100 patients, compared bromocriptine plus levodopa with levodopa alone.4 The studies were of poor quality for reasons similar to the studies in the first review. Researchers found no statistically significant or consistent evidence to determine whether bromocriptine plus levodopa prevents or delays motor complications.

MAO-B inhibitors: Minimally effective with troubling side effects

A Cochrane review of monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors included 10 trials with 2422 participants.5 The review found statistically, but not clinically, significant improvements in scores on 2 sections of the United Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), a standardized assessment tool that facilitates accurate documentation of disease progression and treatment response.

Compared with the control groups (either placebo or levodopa at study onset), the MAO-B group (either alone or with levodopa) showed significant improvement on the motor section (weighted mean difference [WMD]=–3.81 on a 108-point scale; 95% CI, –5.36 to –2.27) and activities of daily living section (WMD=–1.50 on a 52-point scale; 95% CI, –2.53 to –0.48). Fewer motor complications occurred in the MAO-B group (OR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.59-0.94) than the control group. Lower doses and shorter treatment with levodopa were necessary to control symptoms in the MAO-B group.

The clinical impact of MAO-B inhibitors on Parkinson’s symptoms was small, and almost all patients required the addition of levodopa to the treatment regimen after 3 or 4 years. Withdrawals because of medication side effects were significantly higher in the MAO-B inhibitor group than controls (OR=2.36; 95% CI, 1.32-4.20). Side effects included nausea, confusion, hallucinations, and postural hypotension. Concerns about cardiovascular adverse effects raised in previous studies, especially with selegiline, weren’t found to be significant (OR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.92-1.44). Because of their minimal effectiveness and worrisome adverse effects, MAO-B inhibitors aren’t recommended for routine use in early Parkinson’s disease.

COMT inhibitors may boost levodopa/carbidopa’s effects

A randomized double-blinded trial followed 423 patients for 39 weeks to compare the combination of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor entacapone and levodopa/carbidopa (LCE) with levodopa/carbidopa alone (LC).6 The researchers found statistically significant improvements with LCE in UPDRS scores for activities of daily living (mean change from baseline=3.0 for LCE vs 2.3 for LC on a 52-point scale; P=.025) but not mentation or motor symptoms.

Dyskinesia and wearing-off symptoms (motor fluctuations) didn’t differ significantly between the 2 groups. LCE was associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects than LC, and involved mostly nausea (26.6% vs 13.5%) and diarrhea (8.7% vs 2.8%).

Anticholinergics may help, but cause adverse mental effects

Another Cochrane review compared anticholinergic agents with placebo or no treatment in 9 studies that included 221 patients.7 Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because of heterogeneity in patient populations, outcomes, and measurements and incomplete reporting. Compared with placebo, anticholinergic agents may improve Parkinson’s-related motor symptoms but have significant mental adverse effects, including confusion, memory problems, restlessness, and hallucinations.

Recommendations

The most recent guidelines (2002) from the American Academy of Neurology recommend levodopa and dopamine agonists as first-line therapies.8 Levodopa is more effective at improving the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but is associated with a higher risk of dyskinesia than dopamine agonists. No compelling evidence suggests a difference in efficacy between long- and short-acting levodopa.

1. Hauser RA. Levodopa: past, present, and future. Eur Neurol. 2009;62:1-8.

2. Stowe RL, Ives NJ, Clarke C, et al. Dopamine agonist therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006564.-

3. van Hilten JJ, Ramaker CC, Stowe R, et al. Bromocriptine versus levodopa in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD002258.-

4. van Hilten JJ, Ramaker CC, Stowe R, et al. Bromocriptine/levodopa combined versus levodopa alone for early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003634.-

5. Macleod AD, Counsell CE, Ives N, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors for early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004898.-

6. Hauser RA, Panisset M, Abbruzzese G, et al. Double-blind trial of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone versus levodopa/ carbidopa in early Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:541-550.

7. Katzenschlager R, Sampaio C, Costa J, et al. Anticholinergics for symptomatic management of Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003735.-

8. Miyasaki JM, Martin W, Suchowersky O, et al. Practice parameter: initiation of treatment for Parkinson’s disease: an evidence-based review: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2002;58:11-17.

9. Drugs for Parkinson’s disease Treat Guidl Med Lett. 2011;9:1-6

10. Drugstore.com Online Pharmacy. Pharmacy drug costs. Available at http://www.drugstore.com. Accessed August 30, 2011.

LEVODOPA/CARBIDOPA is the most effective medical therapy for Parkinson’s disease, but it’s associated with dyskinesia (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, Cochrane reviews and randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Treating early Parkinson’s disease with dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine can improve symptoms (SOR: B, Cochrane reviews, RCTs with heterogeneity).

Evidence summary

Levodopa/carbidopa is the most commonly prescribed medication for Parkinson’s disease. Although its efficacy is established, it can cause dyskinesia and dystonia.1 Recent studies (TABLE) have evaluated the use of other medications early in the course of Parkinson’s disease in hopes of delaying the waning effectiveness of levodopa over time.

TABLE

Medications commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease

| Medication class brand (generic)9 | Advantages | Disadvantages | Approximate monthly cost at usual dosage (in US $) for generic (brand name prices cited if no generic available)10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbidopa/levodopa Sinemet (carbidopa/ levodopa) Sinemet CR (carbidopa/levodopa controlled-release) | First-line therapy; most effective at improving motor disability1 | Dyskinesia, dystonia, hallucinations No documented benefit of long-acting form1,8 | $34.99-$101.98 $80.99-$295.97 (Highly variable due to dose range) |

| COMT inhibitor Comtan (entacapone) Stalevo (carbidopa/levodopa/entacapone) | Augments levodopa, may improve activities of daily living6 | Same side effects as above plus possible increased nausea, vomiting, diarrhea6 Possible increased cardiovascular risk and prostate cancer | $310.97-$414.62 $318.00-$1043.97 |

| Dopamine agonist Mirapex (pramipexole) Requip (ropinirole) Parlodel (bromocriptine) | Reduced dyskinesias, dystonia, and motor complications2 | Nausea, dizziness, constipation, somnolence, hallucinations, edema2 | $239.99 $71.99-$143.98 $385.97-$1133.92 |

| MAO-B inhibitor Eldepryl (selegiline) | Mild improved motor symptoms of disease, decreased motor fluctuations of treatment, possible “levosparing effect”5 | Limited efficacy and multiple adverse effects leading to high dropout rate; not recommended by Cochrane review5 | $101.99 |

| Anticholinergic Cogentin (benztropine mesylate) | Improved symptoms, mostly tremor7 | Confusion, memory loss, hallucinations, restlessness; contraindicated in dementia7 | $13.99-$22.99 |

| Other Symmetrel (amantadine) | No good updated studies, unproven long-term benefit, nausea, dizziness, insomnia, can cause psychosis9 | $43.17 | |

| COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase type B. | |||

Dopamine agonists: Dyskinesia reduction, but at a price

A Cochrane review of 29 trials with 5247 patients compared dopamine agonists with levodopa.2 Levodopa controlled symptoms better than dopamine agonists, but inconsistent data reporting prevented quantifying this result.

Compared with the group taking levodopa, patients taking dopamine agonists demonstrated a significant reduction in dyskinesia (odds ratio [OR]=0.45; 95% CI, 0.37-0.54), dystonia (OR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.51-0.81), and motor fluctuations (OR= 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.87).

However, patients taking dopamine agonists with or without levodopa experienced significantly more adverse effects than patients taking levodopa alone. Side effects included increased edema (OR=3.68; 95% CI, 2.62-5.18), somnolence (OR=1.49; 95% CI, 1.12-2.00), constipation (OR=1.59; 95% CI, 1.11-2.28), dizziness (OR=1.45; 95% CI, 1.09-1.92), hallucinations (OR=1.69; 95% CI, 1.13-2.52), and nausea (OR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.05-1.66). Patients treated with dopamine agonists were also significantly more likely to discontinue treatment because of adverse events (OR=2.49; 95% CI, 2.08-2.98; P<.00001).

Bromocriptine studies hampered by poor quality

Two Cochrane reviews specifically evaluated the dopamine agonist bromocriptine.3,4 The first focused on 6 head-to-head trials with levodopa that enrolled 850 patients.3 The studies were of poor quality, marred by methodological flaws and clinical heterogeneity. Problems included inadequate power, high variability in study duration (23 weeks to 5 years), differences in reporting, and lack of description of the randomization method in 3 of the 6 trials. Although bromocriptine showed a trend toward lower incidence of motor complications, many patients dropped out of the studies because of increased non-motor adverse effects and inadequate response to treatment.

The second review, of 7 trials with a total of 1100 patients, compared bromocriptine plus levodopa with levodopa alone.4 The studies were of poor quality for reasons similar to the studies in the first review. Researchers found no statistically significant or consistent evidence to determine whether bromocriptine plus levodopa prevents or delays motor complications.

MAO-B inhibitors: Minimally effective with troubling side effects

A Cochrane review of monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors included 10 trials with 2422 participants.5 The review found statistically, but not clinically, significant improvements in scores on 2 sections of the United Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), a standardized assessment tool that facilitates accurate documentation of disease progression and treatment response.

Compared with the control groups (either placebo or levodopa at study onset), the MAO-B group (either alone or with levodopa) showed significant improvement on the motor section (weighted mean difference [WMD]=–3.81 on a 108-point scale; 95% CI, –5.36 to –2.27) and activities of daily living section (WMD=–1.50 on a 52-point scale; 95% CI, –2.53 to –0.48). Fewer motor complications occurred in the MAO-B group (OR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.59-0.94) than the control group. Lower doses and shorter treatment with levodopa were necessary to control symptoms in the MAO-B group.

The clinical impact of MAO-B inhibitors on Parkinson’s symptoms was small, and almost all patients required the addition of levodopa to the treatment regimen after 3 or 4 years. Withdrawals because of medication side effects were significantly higher in the MAO-B inhibitor group than controls (OR=2.36; 95% CI, 1.32-4.20). Side effects included nausea, confusion, hallucinations, and postural hypotension. Concerns about cardiovascular adverse effects raised in previous studies, especially with selegiline, weren’t found to be significant (OR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.92-1.44). Because of their minimal effectiveness and worrisome adverse effects, MAO-B inhibitors aren’t recommended for routine use in early Parkinson’s disease.

COMT inhibitors may boost levodopa/carbidopa’s effects

A randomized double-blinded trial followed 423 patients for 39 weeks to compare the combination of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor entacapone and levodopa/carbidopa (LCE) with levodopa/carbidopa alone (LC).6 The researchers found statistically significant improvements with LCE in UPDRS scores for activities of daily living (mean change from baseline=3.0 for LCE vs 2.3 for LC on a 52-point scale; P=.025) but not mentation or motor symptoms.

Dyskinesia and wearing-off symptoms (motor fluctuations) didn’t differ significantly between the 2 groups. LCE was associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects than LC, and involved mostly nausea (26.6% vs 13.5%) and diarrhea (8.7% vs 2.8%).

Anticholinergics may help, but cause adverse mental effects

Another Cochrane review compared anticholinergic agents with placebo or no treatment in 9 studies that included 221 patients.7 Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because of heterogeneity in patient populations, outcomes, and measurements and incomplete reporting. Compared with placebo, anticholinergic agents may improve Parkinson’s-related motor symptoms but have significant mental adverse effects, including confusion, memory problems, restlessness, and hallucinations.

Recommendations

The most recent guidelines (2002) from the American Academy of Neurology recommend levodopa and dopamine agonists as first-line therapies.8 Levodopa is more effective at improving the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but is associated with a higher risk of dyskinesia than dopamine agonists. No compelling evidence suggests a difference in efficacy between long- and short-acting levodopa.

LEVODOPA/CARBIDOPA is the most effective medical therapy for Parkinson’s disease, but it’s associated with dyskinesia (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, Cochrane reviews and randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Treating early Parkinson’s disease with dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine can improve symptoms (SOR: B, Cochrane reviews, RCTs with heterogeneity).

Evidence summary

Levodopa/carbidopa is the most commonly prescribed medication for Parkinson’s disease. Although its efficacy is established, it can cause dyskinesia and dystonia.1 Recent studies (TABLE) have evaluated the use of other medications early in the course of Parkinson’s disease in hopes of delaying the waning effectiveness of levodopa over time.

TABLE

Medications commonly used to treat Parkinson’s disease

| Medication class brand (generic)9 | Advantages | Disadvantages | Approximate monthly cost at usual dosage (in US $) for generic (brand name prices cited if no generic available)10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbidopa/levodopa Sinemet (carbidopa/ levodopa) Sinemet CR (carbidopa/levodopa controlled-release) | First-line therapy; most effective at improving motor disability1 | Dyskinesia, dystonia, hallucinations No documented benefit of long-acting form1,8 | $34.99-$101.98 $80.99-$295.97 (Highly variable due to dose range) |

| COMT inhibitor Comtan (entacapone) Stalevo (carbidopa/levodopa/entacapone) | Augments levodopa, may improve activities of daily living6 | Same side effects as above plus possible increased nausea, vomiting, diarrhea6 Possible increased cardiovascular risk and prostate cancer | $310.97-$414.62 $318.00-$1043.97 |

| Dopamine agonist Mirapex (pramipexole) Requip (ropinirole) Parlodel (bromocriptine) | Reduced dyskinesias, dystonia, and motor complications2 | Nausea, dizziness, constipation, somnolence, hallucinations, edema2 | $239.99 $71.99-$143.98 $385.97-$1133.92 |

| MAO-B inhibitor Eldepryl (selegiline) | Mild improved motor symptoms of disease, decreased motor fluctuations of treatment, possible “levosparing effect”5 | Limited efficacy and multiple adverse effects leading to high dropout rate; not recommended by Cochrane review5 | $101.99 |

| Anticholinergic Cogentin (benztropine mesylate) | Improved symptoms, mostly tremor7 | Confusion, memory loss, hallucinations, restlessness; contraindicated in dementia7 | $13.99-$22.99 |

| Other Symmetrel (amantadine) | No good updated studies, unproven long-term benefit, nausea, dizziness, insomnia, can cause psychosis9 | $43.17 | |

| COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase type B. | |||

Dopamine agonists: Dyskinesia reduction, but at a price

A Cochrane review of 29 trials with 5247 patients compared dopamine agonists with levodopa.2 Levodopa controlled symptoms better than dopamine agonists, but inconsistent data reporting prevented quantifying this result.

Compared with the group taking levodopa, patients taking dopamine agonists demonstrated a significant reduction in dyskinesia (odds ratio [OR]=0.45; 95% CI, 0.37-0.54), dystonia (OR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.51-0.81), and motor fluctuations (OR= 0.71; 95% CI, 0.58-0.87).

However, patients taking dopamine agonists with or without levodopa experienced significantly more adverse effects than patients taking levodopa alone. Side effects included increased edema (OR=3.68; 95% CI, 2.62-5.18), somnolence (OR=1.49; 95% CI, 1.12-2.00), constipation (OR=1.59; 95% CI, 1.11-2.28), dizziness (OR=1.45; 95% CI, 1.09-1.92), hallucinations (OR=1.69; 95% CI, 1.13-2.52), and nausea (OR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.05-1.66). Patients treated with dopamine agonists were also significantly more likely to discontinue treatment because of adverse events (OR=2.49; 95% CI, 2.08-2.98; P<.00001).

Bromocriptine studies hampered by poor quality

Two Cochrane reviews specifically evaluated the dopamine agonist bromocriptine.3,4 The first focused on 6 head-to-head trials with levodopa that enrolled 850 patients.3 The studies were of poor quality, marred by methodological flaws and clinical heterogeneity. Problems included inadequate power, high variability in study duration (23 weeks to 5 years), differences in reporting, and lack of description of the randomization method in 3 of the 6 trials. Although bromocriptine showed a trend toward lower incidence of motor complications, many patients dropped out of the studies because of increased non-motor adverse effects and inadequate response to treatment.

The second review, of 7 trials with a total of 1100 patients, compared bromocriptine plus levodopa with levodopa alone.4 The studies were of poor quality for reasons similar to the studies in the first review. Researchers found no statistically significant or consistent evidence to determine whether bromocriptine plus levodopa prevents or delays motor complications.

MAO-B inhibitors: Minimally effective with troubling side effects

A Cochrane review of monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors included 10 trials with 2422 participants.5 The review found statistically, but not clinically, significant improvements in scores on 2 sections of the United Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), a standardized assessment tool that facilitates accurate documentation of disease progression and treatment response.

Compared with the control groups (either placebo or levodopa at study onset), the MAO-B group (either alone or with levodopa) showed significant improvement on the motor section (weighted mean difference [WMD]=–3.81 on a 108-point scale; 95% CI, –5.36 to –2.27) and activities of daily living section (WMD=–1.50 on a 52-point scale; 95% CI, –2.53 to –0.48). Fewer motor complications occurred in the MAO-B group (OR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.59-0.94) than the control group. Lower doses and shorter treatment with levodopa were necessary to control symptoms in the MAO-B group.

The clinical impact of MAO-B inhibitors on Parkinson’s symptoms was small, and almost all patients required the addition of levodopa to the treatment regimen after 3 or 4 years. Withdrawals because of medication side effects were significantly higher in the MAO-B inhibitor group than controls (OR=2.36; 95% CI, 1.32-4.20). Side effects included nausea, confusion, hallucinations, and postural hypotension. Concerns about cardiovascular adverse effects raised in previous studies, especially with selegiline, weren’t found to be significant (OR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.92-1.44). Because of their minimal effectiveness and worrisome adverse effects, MAO-B inhibitors aren’t recommended for routine use in early Parkinson’s disease.

COMT inhibitors may boost levodopa/carbidopa’s effects

A randomized double-blinded trial followed 423 patients for 39 weeks to compare the combination of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor entacapone and levodopa/carbidopa (LCE) with levodopa/carbidopa alone (LC).6 The researchers found statistically significant improvements with LCE in UPDRS scores for activities of daily living (mean change from baseline=3.0 for LCE vs 2.3 for LC on a 52-point scale; P=.025) but not mentation or motor symptoms.

Dyskinesia and wearing-off symptoms (motor fluctuations) didn’t differ significantly between the 2 groups. LCE was associated with a higher incidence of adverse effects than LC, and involved mostly nausea (26.6% vs 13.5%) and diarrhea (8.7% vs 2.8%).

Anticholinergics may help, but cause adverse mental effects

Another Cochrane review compared anticholinergic agents with placebo or no treatment in 9 studies that included 221 patients.7 Meta-analysis wasn’t possible because of heterogeneity in patient populations, outcomes, and measurements and incomplete reporting. Compared with placebo, anticholinergic agents may improve Parkinson’s-related motor symptoms but have significant mental adverse effects, including confusion, memory problems, restlessness, and hallucinations.

Recommendations

The most recent guidelines (2002) from the American Academy of Neurology recommend levodopa and dopamine agonists as first-line therapies.8 Levodopa is more effective at improving the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease but is associated with a higher risk of dyskinesia than dopamine agonists. No compelling evidence suggests a difference in efficacy between long- and short-acting levodopa.

1. Hauser RA. Levodopa: past, present, and future. Eur Neurol. 2009;62:1-8.

2. Stowe RL, Ives NJ, Clarke C, et al. Dopamine agonist therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006564.-

3. van Hilten JJ, Ramaker CC, Stowe R, et al. Bromocriptine versus levodopa in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD002258.-

4. van Hilten JJ, Ramaker CC, Stowe R, et al. Bromocriptine/levodopa combined versus levodopa alone for early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003634.-

5. Macleod AD, Counsell CE, Ives N, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors for early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004898.-

6. Hauser RA, Panisset M, Abbruzzese G, et al. Double-blind trial of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone versus levodopa/ carbidopa in early Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:541-550.

7. Katzenschlager R, Sampaio C, Costa J, et al. Anticholinergics for symptomatic management of Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003735.-

8. Miyasaki JM, Martin W, Suchowersky O, et al. Practice parameter: initiation of treatment for Parkinson’s disease: an evidence-based review: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2002;58:11-17.

9. Drugs for Parkinson’s disease Treat Guidl Med Lett. 2011;9:1-6

10. Drugstore.com Online Pharmacy. Pharmacy drug costs. Available at http://www.drugstore.com. Accessed August 30, 2011.

1. Hauser RA. Levodopa: past, present, and future. Eur Neurol. 2009;62:1-8.

2. Stowe RL, Ives NJ, Clarke C, et al. Dopamine agonist therapy in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006564.-

3. van Hilten JJ, Ramaker CC, Stowe R, et al. Bromocriptine versus levodopa in early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD002258.-

4. van Hilten JJ, Ramaker CC, Stowe R, et al. Bromocriptine/levodopa combined versus levodopa alone for early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD003634.-

5. Macleod AD, Counsell CE, Ives N, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitors for early Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004898.-

6. Hauser RA, Panisset M, Abbruzzese G, et al. Double-blind trial of levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone versus levodopa/ carbidopa in early Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:541-550.

7. Katzenschlager R, Sampaio C, Costa J, et al. Anticholinergics for symptomatic management of Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD003735.-

8. Miyasaki JM, Martin W, Suchowersky O, et al. Practice parameter: initiation of treatment for Parkinson’s disease: an evidence-based review: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2002;58:11-17.

9. Drugs for Parkinson’s disease Treat Guidl Med Lett. 2011;9:1-6

10. Drugstore.com Online Pharmacy. Pharmacy drug costs. Available at http://www.drugstore.com. Accessed August 30, 2011.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network