User login

Risk Factors Predicting Cellulitis Diagnosis in a Prospective Cohort Undergoing Dermatology Consultation in the Emergency Department

Cellulitis is an infection of the skin and skin-associated structures characterized by redness, warmth, swelling, and pain of the affected area. Cellulitis most commonly occurs in middle-aged and older adults and frequently affects the lower extremities.1 Serious complications of cellulitis such as bacteremia, metastatic infection, and sepsis are rare, and most cases of cellulitis in patients with normal vital signs and mental status can be managed with outpatient treatment.2

Diagnosis of cellulitis can be confounded by a number of similarly presenting conditions collectively known as pseudocellulitis, such as venous stasis dermatitis and deep vein thrombosis.1 Misdiagnosis of cellulitis is common, with rates exceeding 30% among hospitalized patients initially diagnosed with cellulitis.3,4 Dermatology or infectious disease assessment is considered the diagnostic gold standard for cellulitis4,5 but is not always readily available, especially in resource-constrained settings.

Most cases of uncomplicated cellulitis can be managed with outpatient treatment, especially because serious complications are rare. Frequent misdiagnosis leads to repeat or unnecessary hospitalization and antibiosis. Exceptions necessitating hospitalization usually are predicated on signs of systemic infection, severe immunocompromised states, or failure of prior outpatient therapy.6 Such presentations can be distinguished by corresponding notable historical or examination factors, such as vital sign abnormalities suggesting systemic infection or history of malignancy leading to an immunocompromised state.

We sought to evaluate factors leading to the diagnosis of cellulitis in a cohort of patients with uncomplicated presentations receiving dermatology consultation to emphasize findings indicative of cellulitis in the absence of clinical or historical factors suggestive of other conditions necessitating hospitalization, such as systemic infection.

Methods

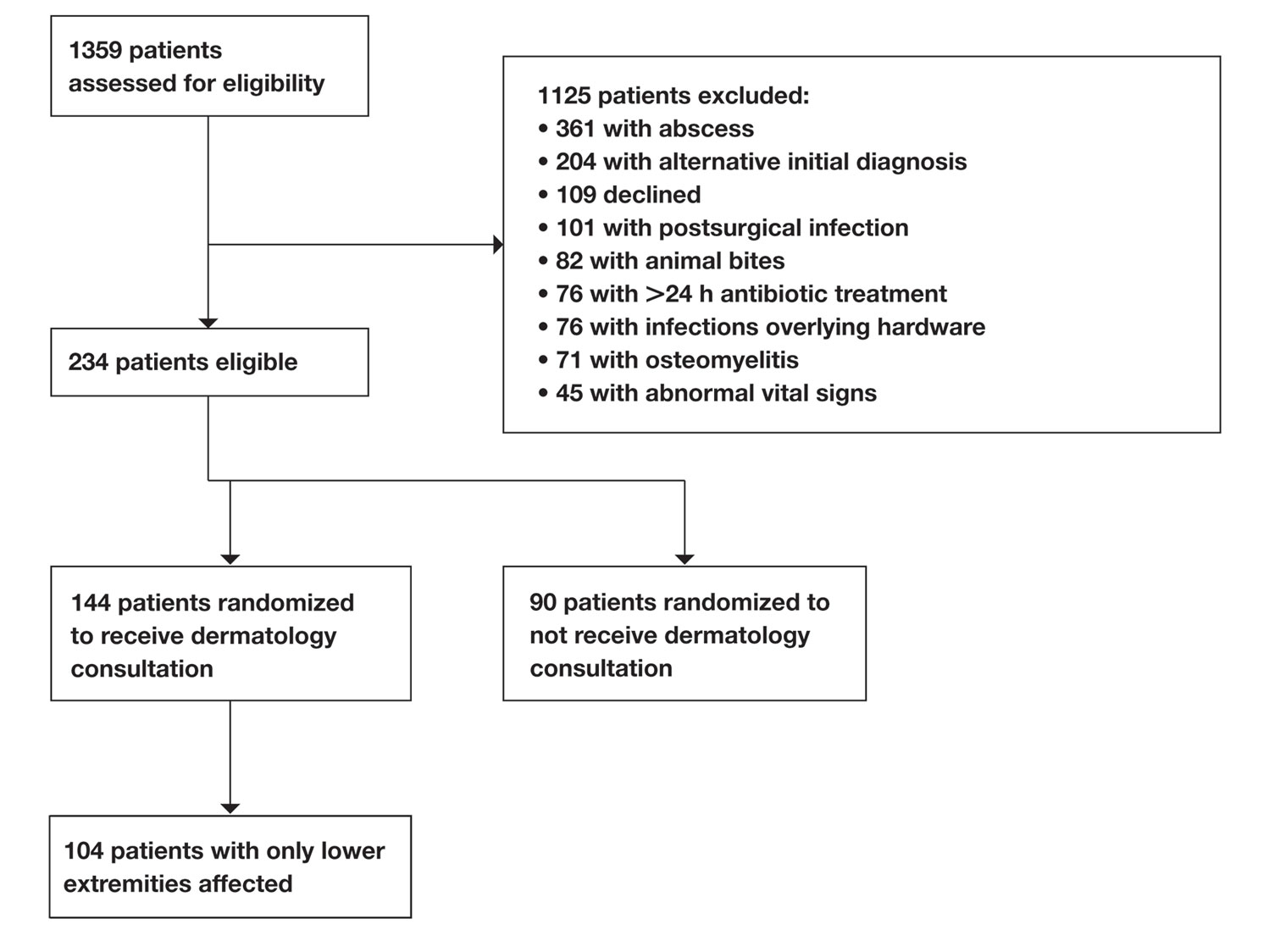

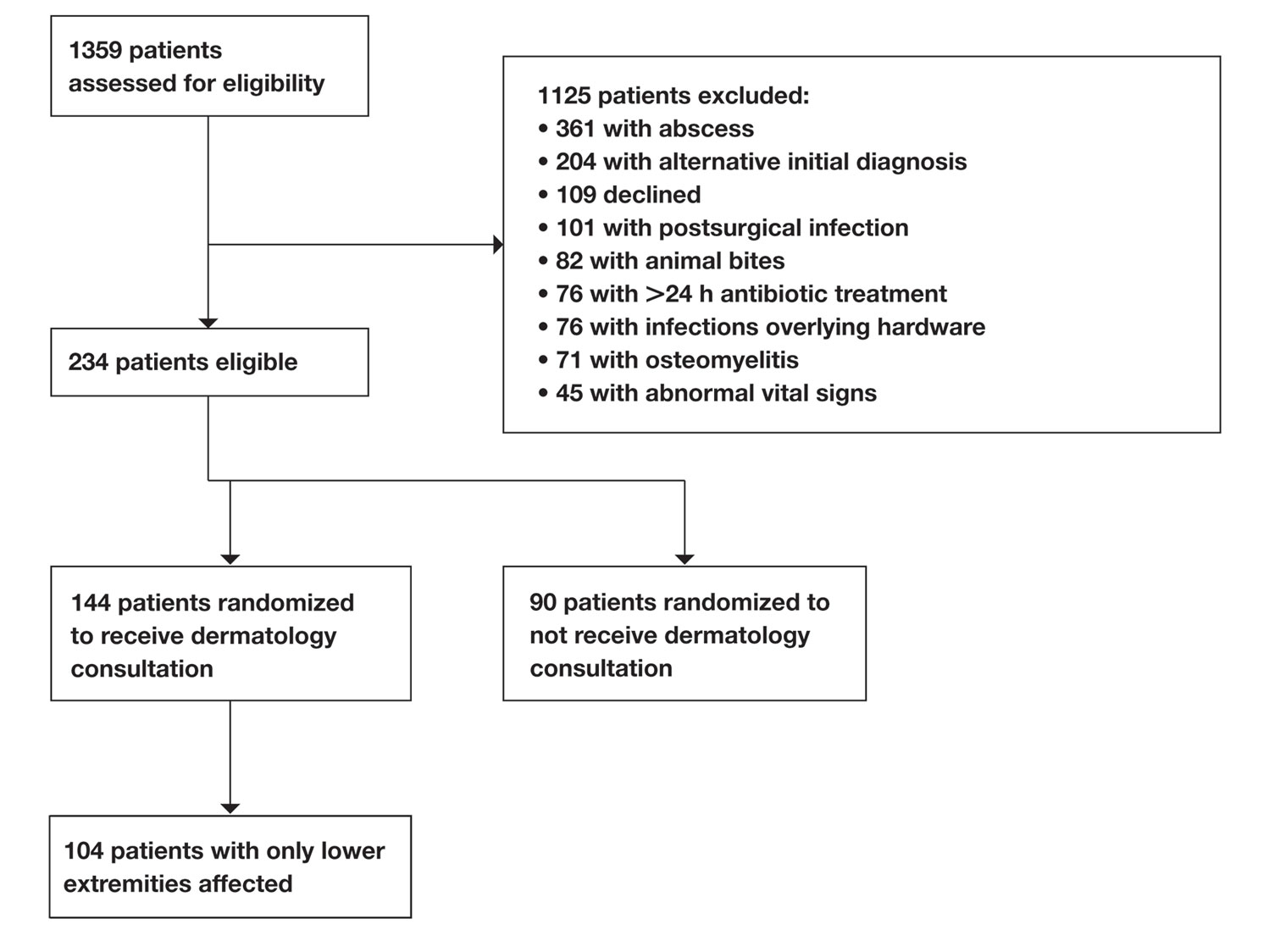

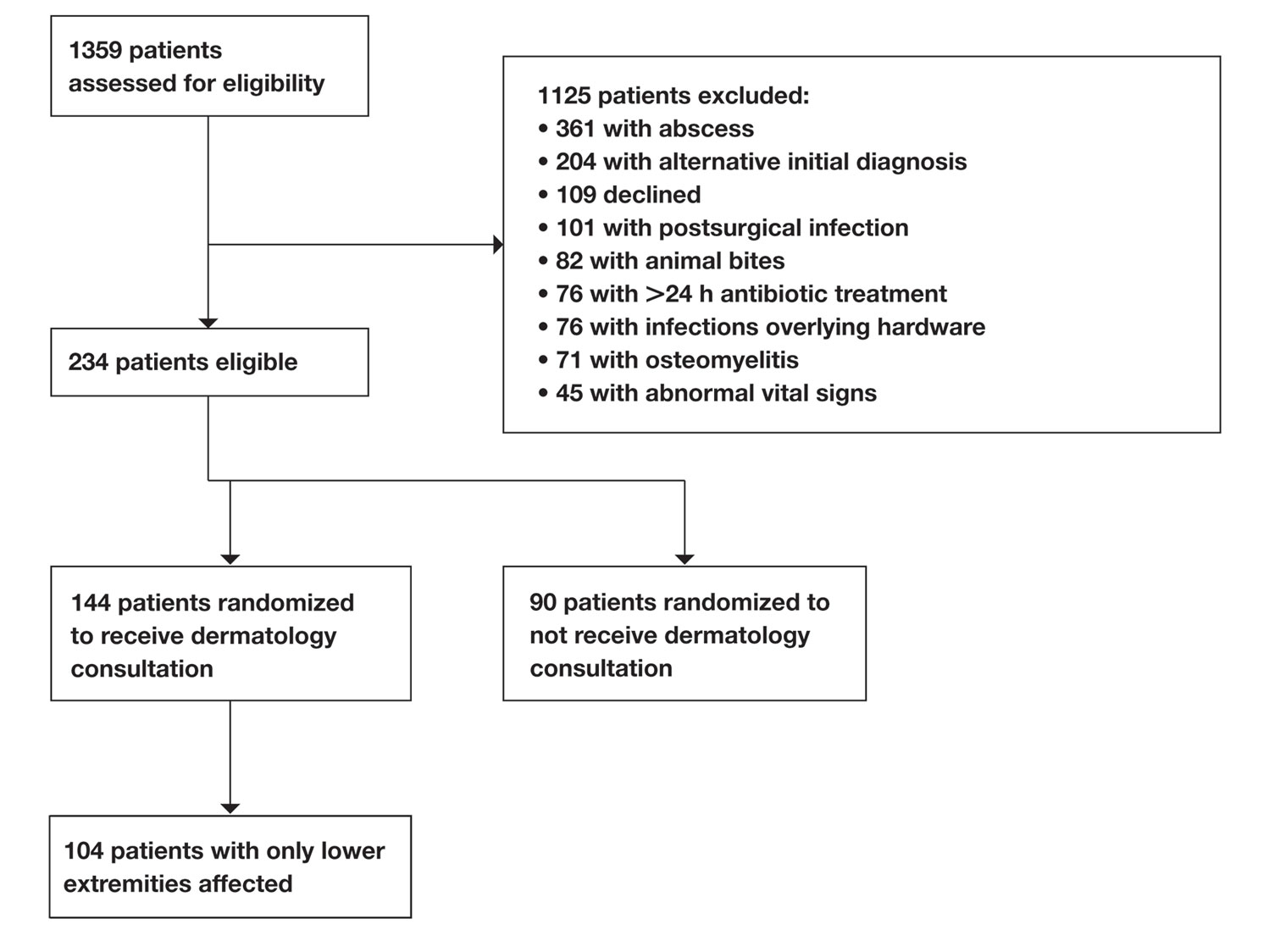

Study Participants—A prospective cohort study of patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) between October 2012 and January 2017 at an urban academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts, was conducted with approval of study design and procedures by the relevant institutional review board. Patients older than 18 years were eligible for inclusion if given an initial diagnosis of cellulitis by an ED physician. Patients were excluded if incarcerated, pregnant, or unable to provide informed consent. Other exclusion criteria includedinfections overlying temporary or permanent indwelling hardware, animal or human bites, or sites of recent surgery (within the prior 4 weeks); preceding antibiotic treatment for more than 24 hours; or clinical or radiographic evidence of complications requiring alternative management such as osteomyelitis or abscess. Patients presenting with an elevated heart rate (>100 beats per minute) or body temperature (>100.5 °F [38.1 °C]) also were excluded. Eligible patients were enrolled upon providing written informed consent, and no remuneration was offered for participation.

Dermatology Consultation Intervention—A random subset of enrolled patients received dermatology consultation within 24 hours of presentation. Consultation consisted of a patient interview and physical examination with care recommendations to relevant ED and inpatient teams. Consultations confirmed the presence or absence of cellulitis as the primary outcome and also noted the presence of any pseudocellulitis diagnoses either occurring concomitantly with or mimicking cellulitis as a secondary outcome.

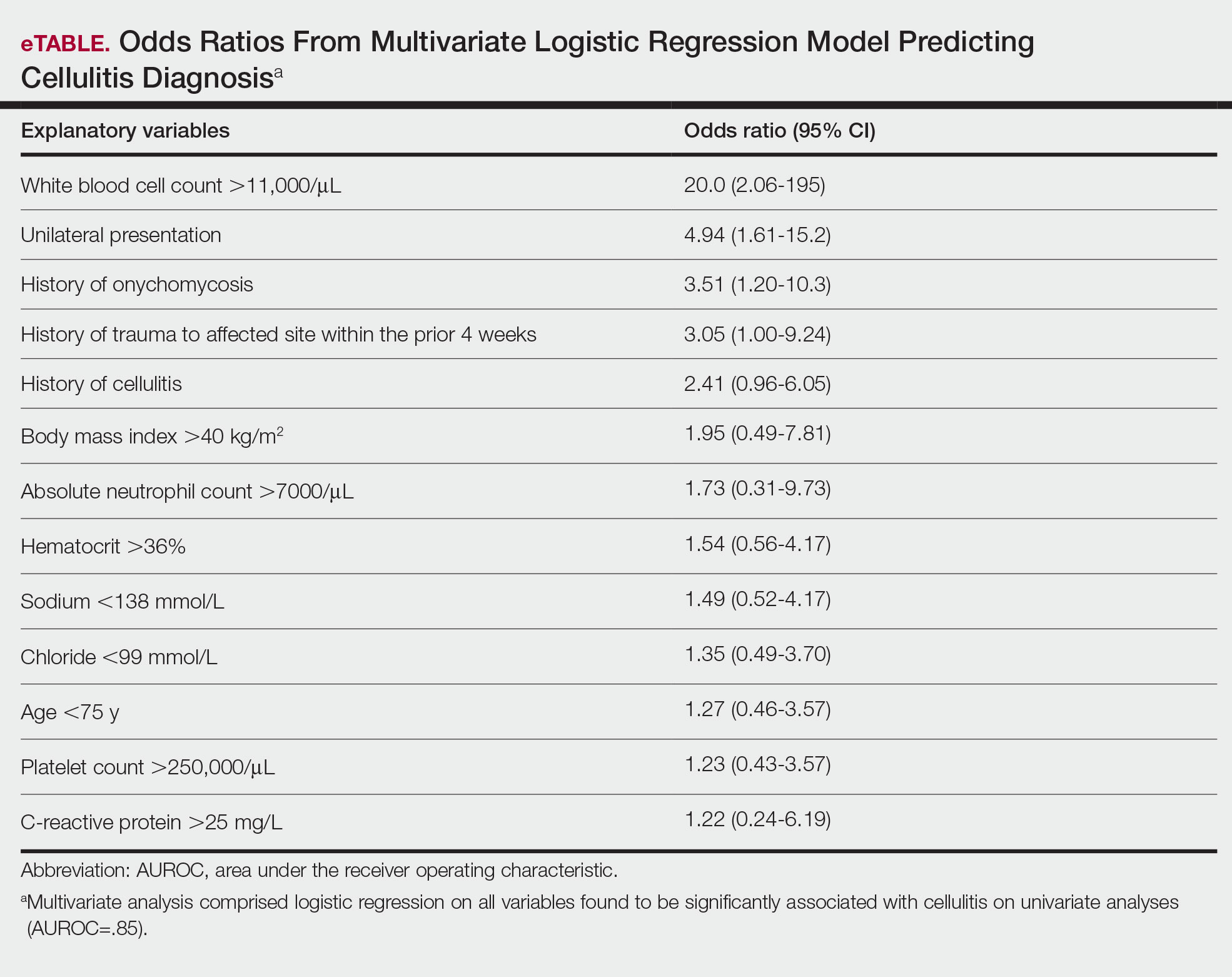

Statistical Analysis—Patient characteristics were analyzed to identify factors independently associated with the diagnosis of cellulitis in cases affecting the lower extremities. Factors were recorded with categorical variables reported as counts and percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Univariate analyses between categorical variables or discretized continuous variables and cellulitis diagnosis were conducted via Fisher exact test to identify a preliminary set of potential risk factors. Continuous variables were discretized at multiple incremental values with the discretization most significantly associated with cellulitis diagnosis selected as a preliminary risk factor. Multivariate analyses involved using any objective preliminary factor meeting a significance threshold of P<.1 in univariate comparisons in a multivariate logistic regression model for prediction of cellulitis diagnosis with corresponding calculation of odds ratios with confidence intervals and receiver operating characteristic. Factors with confidence intervals that excluded 1 were considered significant independent predictors of cellulitis. Analyses were performed using Python version 3.8 (Python Software Foundation).

Results

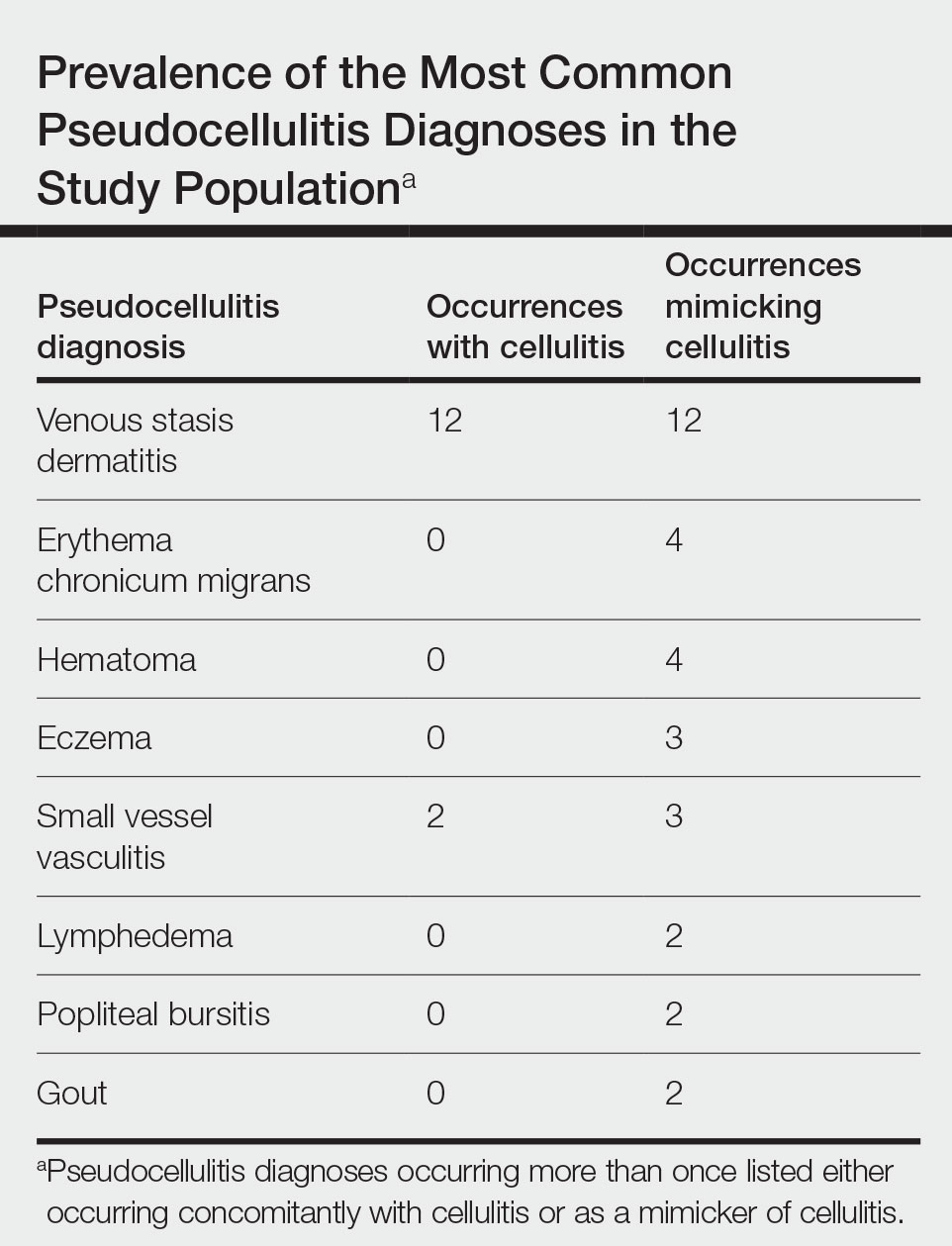

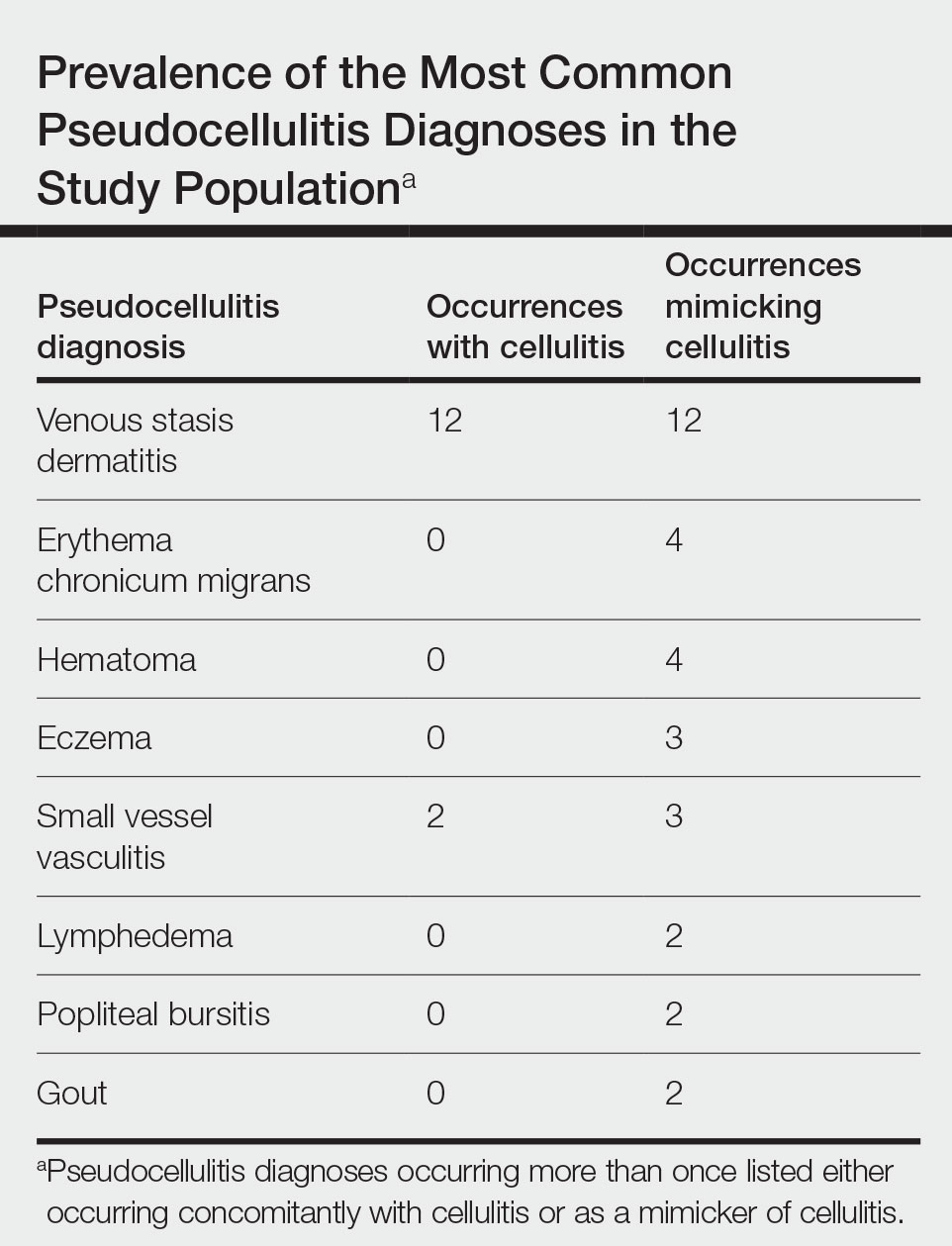

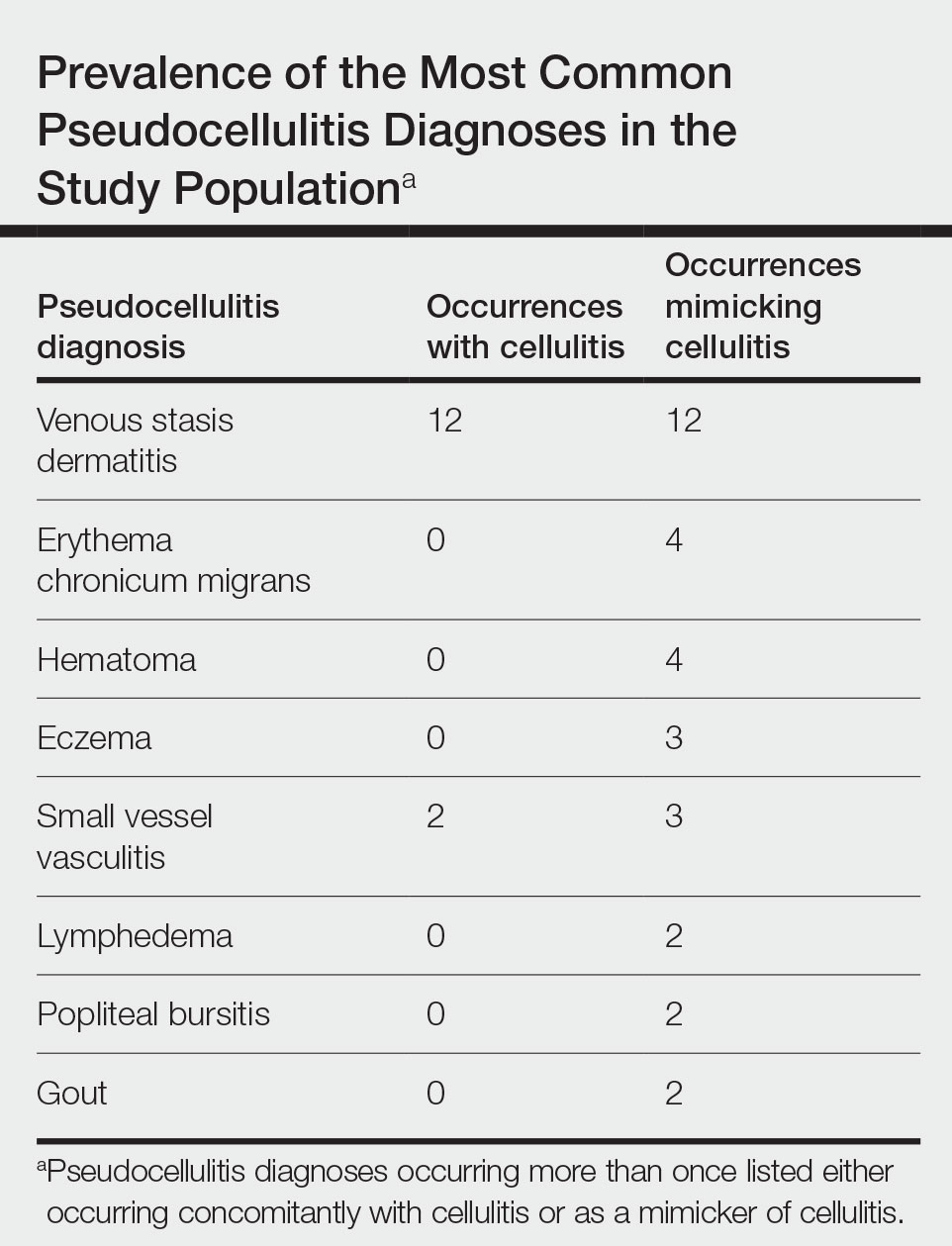

Of 1359 patients screened for eligibility, 104 patients with presumed lower extremity cellulitis undergoing dermatology consultation were included in this study (Figure). The mean patient age (SD) was 60.4 (19.2) years, and 63.5% of patients were male. In the study population, 63 (60.6%) patients received a final diagnosis of cellulitis. The most common pseudocellulitis diagnosis identified was venous stasis dermatitis, which occurred in 12 (11.5%) patients with concomitant cellulitis and in 12 (11.5%) patients mimicking cellulitis (Table).

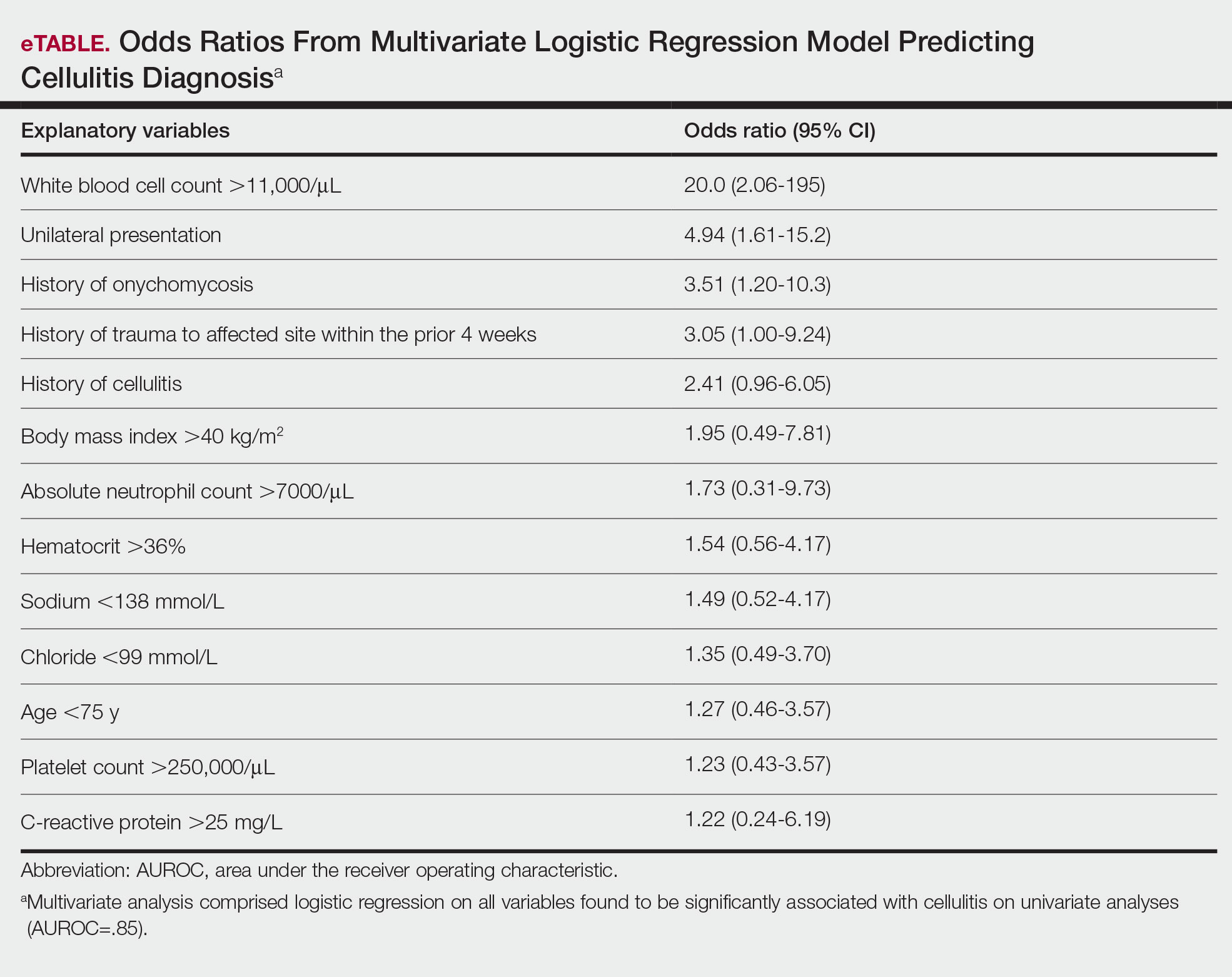

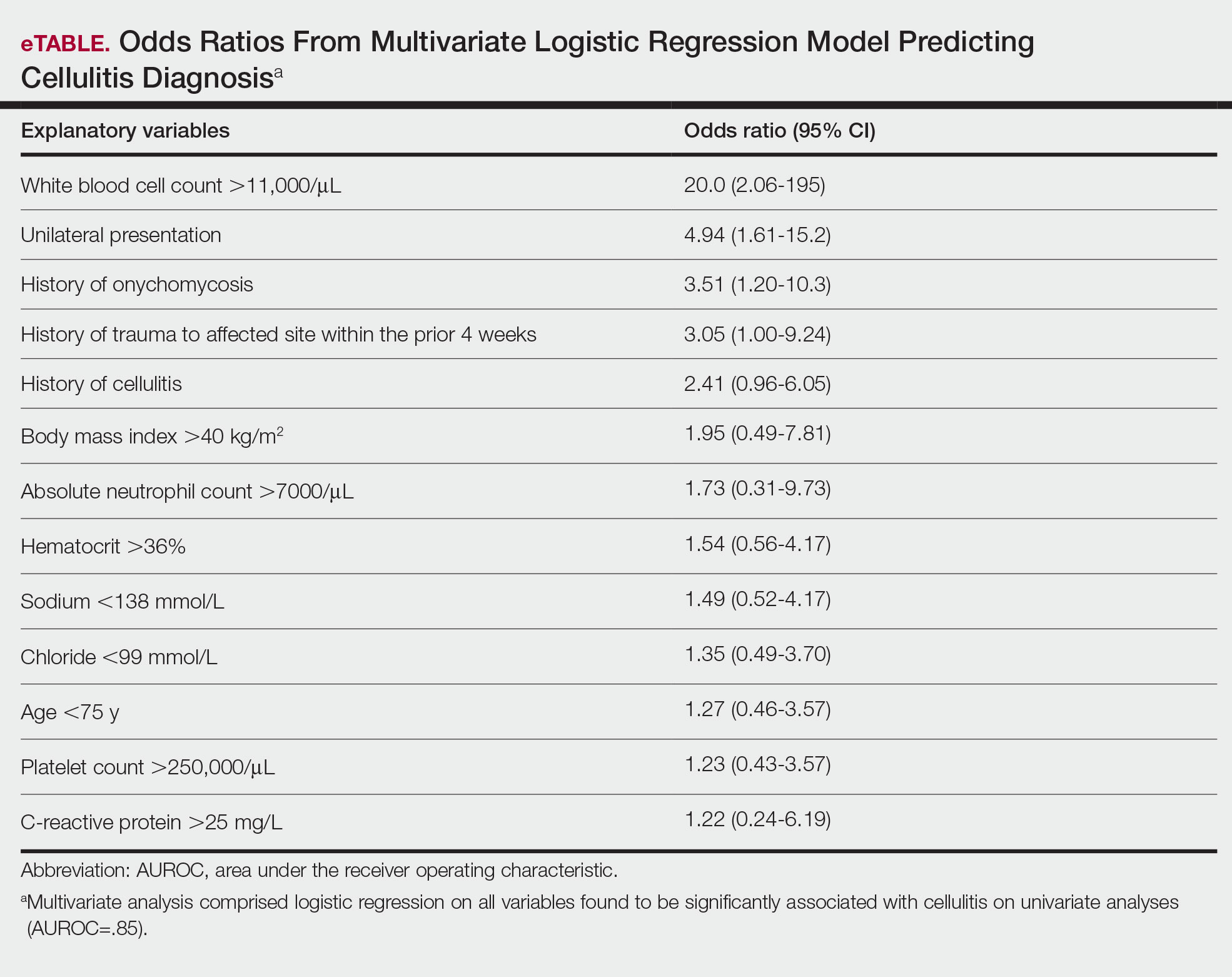

Univariate comparisons revealed a diverse set of historical, examination, and laboratory factors associated with cellulitis diagnosis. Diagnosis of cellulitis was associated with unilateral presentation, recent trauma to the affected site, and history of cellulitis or onychomycosis. Diagnosis of cellulitis also was associated with elevated white blood cell count, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, body mass index, hematocrit, and platelet count; age less than 75 years; and lower serum sodium and serum chloride levels. These were the independent factors included in the multivariate analysis, which consisted of a logistic regression model for prediction of cellulitis (eTable).

Multivariate logistic regression on all preliminary factors significantly associated with cellulitis diagnosis in univariate comparisons demonstrated leukocytosis, which was defined as having a white blood cell count exceeding 11,000/μL, unilateral presentation, history of onychomycosis, and trauma to the affected site as significant independent predictors of cellulitis diagnosis; history of cellulitis approached significance (eTable). Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis were the strongest predictors; having either of these factors had a sensitivity of 93.7% and a negative predictive value of 76.5%.

Comment

Importance of Identifying Pseudocellulitis—Successful diagnosis of cellulitis can be confounded by pseudocellulitis that can present concomitantly with or in lieu of cellulitis itself. Although cellulitis mostly affects the lower extremities in adults, pseudocellulitis also was common in this study population of patients with suspected lower extremity cellulitis, occurring both as a mimicker and concomitantly with cellulitis with substantial frequency. Notably, among patients with both venous stasis dermatitis and cellulitis diagnosed, most patients (n=10/12; 83.3%) had unilateral presentations of cellulitis as evidenced by signs and symptoms more notably affecting one lower extremity than the other. These findings suggest that certain pseudocellulitis diagnoses may predispose patients to cellulitis by disrupting the skin barrier, leading to bacterial infiltration; however, these pseudocellulitis diagnoses typically affect both lower extremities equally,1 and asymmetric involvement suggests the presence of overlying cellulitis. Furthermore, the most common pseudocellulitis entities found, such as venous stasis dermatitis, hematoma, and eczema, do not benefit from antibiotic treatment and require alternative therapy.1 Successful discrimination of these pseudocellulitis entities is critical to bolster proper antibiotic stewardship and discourage unnecessary hospitalization.

Independent Predictors of Cellulitis—Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis each emerged as strong independent predictors of cellulitis diagnosis in this study. Having either of these factors furthermore demonstrated high sensitivity and negative predictive value for cellulitis diagnosis. Other notable risk factors were history of onychomycosis, cellulitis, and trauma to the affected site. Prior studies have identified similar historical factors as predisposing patients to cellulitis.7-9 Interestingly, warmth of the affected area on physical examination emerged as strongly associated with cellulitis but was not included in the final predictive model because of its subjective determination. These factors may be especially important in diagnosing cellulitis in patients without concerning vital signs and with concomitant or prior pseudocellulitis.

Study Limitations—This study was limited to patients with uncomplicated presentations to emphasize discrimination of factors associated with cellulitis in the absence of suggestive signs of infection, such as vital sign abnormalities. Signs such as fever and tachypnea have been previously correlated to outpatient treatment failure and necessity for hospitalization.10-12 This study instead focused on patients without concerning vital signs to reduce confounding by such factors in more severe presentations that heighten suspicion for infection and increase likelihood of additional treatment measures. For such patients, suggestive historical factors, such as those discovered in this study, should be considered instead. Interestingly, increased age did not emerge as a significant predictor in this population in contrast to other predictive models that included patients with vital sign abnormalities. Notably, older patients tend to have more variable vital signs, especially in response to physiologic stressors such as infection.13 As such, age may serve as a proxy for vital sign abnormalities to some degree in such predictive models, leading to heightened suspicion for infection in older patients. This study demonstrated that in the absence of concerning vital signs, historical rather than demographic factors are more predictive of cellulitis.

Conclusion

Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis emerged as strong independent predictors of lower extremity cellulitis in patients with uncomplicated presentations. Having either of these factors had a sensitivity of 93.7% and a negative predictive value of 76.5%. Other factors such as history of cellulitis, onychomycosis, and recent trauma to the affected site emerged as additional predictors. These historical, examination, and laboratory characteristics may be especially useful for successful diagnosis of cellulitis in varied practice settings, including outpatient clinics and EDs.

- Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA. 2016;316:325-337.

- Gunderson CG, Cherry BM, Fisher A. Do patients with cellulitis need to be hospitalized? a systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality rates of inpatients with cellulitis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1553-1560.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St. John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hughey LC. The impact dermatologists can have on misdiagnosis of cellulitis and overuse of antibiotics: closing the gap. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1061-1062.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159.

- Björnsdóttir S, Gottfredsson M, Thórisdóttir AS, et al. Risk factors for acute cellulitis of the lower limb: a prospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1416-1422.

- Roujeau JC, Sigurgeirsson B, Korting HC, et al. Chronic dermatomycoses of the foot as risk factors for acute bacterial cellulitis of the leg: a case-control study. Dermatology. 2004;209:301-307.

- McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, et al. A predictive model of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a population-based cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:709-715.

- Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, et al. Predictors of oral antibiotic treatment failure for nonpurulent skin and soft tissue infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26:51-59.

- Peterson D, McLeod S, Woolfrey K, et al. Predictors of failure of empiric outpatient antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with uncomplicated cellulitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:526-531.

- Volz KA, Canham L, Kaplan E, et al. Identifying patients with cellulitis who are likely to require inpatient admission after a stay in an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:360-364.

- Chester JG, Rudolph JL. Vital signs in older patients: age-related changes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:337-343.

Cellulitis is an infection of the skin and skin-associated structures characterized by redness, warmth, swelling, and pain of the affected area. Cellulitis most commonly occurs in middle-aged and older adults and frequently affects the lower extremities.1 Serious complications of cellulitis such as bacteremia, metastatic infection, and sepsis are rare, and most cases of cellulitis in patients with normal vital signs and mental status can be managed with outpatient treatment.2

Diagnosis of cellulitis can be confounded by a number of similarly presenting conditions collectively known as pseudocellulitis, such as venous stasis dermatitis and deep vein thrombosis.1 Misdiagnosis of cellulitis is common, with rates exceeding 30% among hospitalized patients initially diagnosed with cellulitis.3,4 Dermatology or infectious disease assessment is considered the diagnostic gold standard for cellulitis4,5 but is not always readily available, especially in resource-constrained settings.

Most cases of uncomplicated cellulitis can be managed with outpatient treatment, especially because serious complications are rare. Frequent misdiagnosis leads to repeat or unnecessary hospitalization and antibiosis. Exceptions necessitating hospitalization usually are predicated on signs of systemic infection, severe immunocompromised states, or failure of prior outpatient therapy.6 Such presentations can be distinguished by corresponding notable historical or examination factors, such as vital sign abnormalities suggesting systemic infection or history of malignancy leading to an immunocompromised state.

We sought to evaluate factors leading to the diagnosis of cellulitis in a cohort of patients with uncomplicated presentations receiving dermatology consultation to emphasize findings indicative of cellulitis in the absence of clinical or historical factors suggestive of other conditions necessitating hospitalization, such as systemic infection.

Methods

Study Participants—A prospective cohort study of patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) between October 2012 and January 2017 at an urban academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts, was conducted with approval of study design and procedures by the relevant institutional review board. Patients older than 18 years were eligible for inclusion if given an initial diagnosis of cellulitis by an ED physician. Patients were excluded if incarcerated, pregnant, or unable to provide informed consent. Other exclusion criteria includedinfections overlying temporary or permanent indwelling hardware, animal or human bites, or sites of recent surgery (within the prior 4 weeks); preceding antibiotic treatment for more than 24 hours; or clinical or radiographic evidence of complications requiring alternative management such as osteomyelitis or abscess. Patients presenting with an elevated heart rate (>100 beats per minute) or body temperature (>100.5 °F [38.1 °C]) also were excluded. Eligible patients were enrolled upon providing written informed consent, and no remuneration was offered for participation.

Dermatology Consultation Intervention—A random subset of enrolled patients received dermatology consultation within 24 hours of presentation. Consultation consisted of a patient interview and physical examination with care recommendations to relevant ED and inpatient teams. Consultations confirmed the presence or absence of cellulitis as the primary outcome and also noted the presence of any pseudocellulitis diagnoses either occurring concomitantly with or mimicking cellulitis as a secondary outcome.

Statistical Analysis—Patient characteristics were analyzed to identify factors independently associated with the diagnosis of cellulitis in cases affecting the lower extremities. Factors were recorded with categorical variables reported as counts and percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Univariate analyses between categorical variables or discretized continuous variables and cellulitis diagnosis were conducted via Fisher exact test to identify a preliminary set of potential risk factors. Continuous variables were discretized at multiple incremental values with the discretization most significantly associated with cellulitis diagnosis selected as a preliminary risk factor. Multivariate analyses involved using any objective preliminary factor meeting a significance threshold of P<.1 in univariate comparisons in a multivariate logistic regression model for prediction of cellulitis diagnosis with corresponding calculation of odds ratios with confidence intervals and receiver operating characteristic. Factors with confidence intervals that excluded 1 were considered significant independent predictors of cellulitis. Analyses were performed using Python version 3.8 (Python Software Foundation).

Results

Of 1359 patients screened for eligibility, 104 patients with presumed lower extremity cellulitis undergoing dermatology consultation were included in this study (Figure). The mean patient age (SD) was 60.4 (19.2) years, and 63.5% of patients were male. In the study population, 63 (60.6%) patients received a final diagnosis of cellulitis. The most common pseudocellulitis diagnosis identified was venous stasis dermatitis, which occurred in 12 (11.5%) patients with concomitant cellulitis and in 12 (11.5%) patients mimicking cellulitis (Table).

Univariate comparisons revealed a diverse set of historical, examination, and laboratory factors associated with cellulitis diagnosis. Diagnosis of cellulitis was associated with unilateral presentation, recent trauma to the affected site, and history of cellulitis or onychomycosis. Diagnosis of cellulitis also was associated with elevated white blood cell count, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, body mass index, hematocrit, and platelet count; age less than 75 years; and lower serum sodium and serum chloride levels. These were the independent factors included in the multivariate analysis, which consisted of a logistic regression model for prediction of cellulitis (eTable).

Multivariate logistic regression on all preliminary factors significantly associated with cellulitis diagnosis in univariate comparisons demonstrated leukocytosis, which was defined as having a white blood cell count exceeding 11,000/μL, unilateral presentation, history of onychomycosis, and trauma to the affected site as significant independent predictors of cellulitis diagnosis; history of cellulitis approached significance (eTable). Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis were the strongest predictors; having either of these factors had a sensitivity of 93.7% and a negative predictive value of 76.5%.

Comment

Importance of Identifying Pseudocellulitis—Successful diagnosis of cellulitis can be confounded by pseudocellulitis that can present concomitantly with or in lieu of cellulitis itself. Although cellulitis mostly affects the lower extremities in adults, pseudocellulitis also was common in this study population of patients with suspected lower extremity cellulitis, occurring both as a mimicker and concomitantly with cellulitis with substantial frequency. Notably, among patients with both venous stasis dermatitis and cellulitis diagnosed, most patients (n=10/12; 83.3%) had unilateral presentations of cellulitis as evidenced by signs and symptoms more notably affecting one lower extremity than the other. These findings suggest that certain pseudocellulitis diagnoses may predispose patients to cellulitis by disrupting the skin barrier, leading to bacterial infiltration; however, these pseudocellulitis diagnoses typically affect both lower extremities equally,1 and asymmetric involvement suggests the presence of overlying cellulitis. Furthermore, the most common pseudocellulitis entities found, such as venous stasis dermatitis, hematoma, and eczema, do not benefit from antibiotic treatment and require alternative therapy.1 Successful discrimination of these pseudocellulitis entities is critical to bolster proper antibiotic stewardship and discourage unnecessary hospitalization.

Independent Predictors of Cellulitis—Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis each emerged as strong independent predictors of cellulitis diagnosis in this study. Having either of these factors furthermore demonstrated high sensitivity and negative predictive value for cellulitis diagnosis. Other notable risk factors were history of onychomycosis, cellulitis, and trauma to the affected site. Prior studies have identified similar historical factors as predisposing patients to cellulitis.7-9 Interestingly, warmth of the affected area on physical examination emerged as strongly associated with cellulitis but was not included in the final predictive model because of its subjective determination. These factors may be especially important in diagnosing cellulitis in patients without concerning vital signs and with concomitant or prior pseudocellulitis.

Study Limitations—This study was limited to patients with uncomplicated presentations to emphasize discrimination of factors associated with cellulitis in the absence of suggestive signs of infection, such as vital sign abnormalities. Signs such as fever and tachypnea have been previously correlated to outpatient treatment failure and necessity for hospitalization.10-12 This study instead focused on patients without concerning vital signs to reduce confounding by such factors in more severe presentations that heighten suspicion for infection and increase likelihood of additional treatment measures. For such patients, suggestive historical factors, such as those discovered in this study, should be considered instead. Interestingly, increased age did not emerge as a significant predictor in this population in contrast to other predictive models that included patients with vital sign abnormalities. Notably, older patients tend to have more variable vital signs, especially in response to physiologic stressors such as infection.13 As such, age may serve as a proxy for vital sign abnormalities to some degree in such predictive models, leading to heightened suspicion for infection in older patients. This study demonstrated that in the absence of concerning vital signs, historical rather than demographic factors are more predictive of cellulitis.

Conclusion

Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis emerged as strong independent predictors of lower extremity cellulitis in patients with uncomplicated presentations. Having either of these factors had a sensitivity of 93.7% and a negative predictive value of 76.5%. Other factors such as history of cellulitis, onychomycosis, and recent trauma to the affected site emerged as additional predictors. These historical, examination, and laboratory characteristics may be especially useful for successful diagnosis of cellulitis in varied practice settings, including outpatient clinics and EDs.

Cellulitis is an infection of the skin and skin-associated structures characterized by redness, warmth, swelling, and pain of the affected area. Cellulitis most commonly occurs in middle-aged and older adults and frequently affects the lower extremities.1 Serious complications of cellulitis such as bacteremia, metastatic infection, and sepsis are rare, and most cases of cellulitis in patients with normal vital signs and mental status can be managed with outpatient treatment.2

Diagnosis of cellulitis can be confounded by a number of similarly presenting conditions collectively known as pseudocellulitis, such as venous stasis dermatitis and deep vein thrombosis.1 Misdiagnosis of cellulitis is common, with rates exceeding 30% among hospitalized patients initially diagnosed with cellulitis.3,4 Dermatology or infectious disease assessment is considered the diagnostic gold standard for cellulitis4,5 but is not always readily available, especially in resource-constrained settings.

Most cases of uncomplicated cellulitis can be managed with outpatient treatment, especially because serious complications are rare. Frequent misdiagnosis leads to repeat or unnecessary hospitalization and antibiosis. Exceptions necessitating hospitalization usually are predicated on signs of systemic infection, severe immunocompromised states, or failure of prior outpatient therapy.6 Such presentations can be distinguished by corresponding notable historical or examination factors, such as vital sign abnormalities suggesting systemic infection or history of malignancy leading to an immunocompromised state.

We sought to evaluate factors leading to the diagnosis of cellulitis in a cohort of patients with uncomplicated presentations receiving dermatology consultation to emphasize findings indicative of cellulitis in the absence of clinical or historical factors suggestive of other conditions necessitating hospitalization, such as systemic infection.

Methods

Study Participants—A prospective cohort study of patients presenting to an emergency department (ED) between October 2012 and January 2017 at an urban academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts, was conducted with approval of study design and procedures by the relevant institutional review board. Patients older than 18 years were eligible for inclusion if given an initial diagnosis of cellulitis by an ED physician. Patients were excluded if incarcerated, pregnant, or unable to provide informed consent. Other exclusion criteria includedinfections overlying temporary or permanent indwelling hardware, animal or human bites, or sites of recent surgery (within the prior 4 weeks); preceding antibiotic treatment for more than 24 hours; or clinical or radiographic evidence of complications requiring alternative management such as osteomyelitis or abscess. Patients presenting with an elevated heart rate (>100 beats per minute) or body temperature (>100.5 °F [38.1 °C]) also were excluded. Eligible patients were enrolled upon providing written informed consent, and no remuneration was offered for participation.

Dermatology Consultation Intervention—A random subset of enrolled patients received dermatology consultation within 24 hours of presentation. Consultation consisted of a patient interview and physical examination with care recommendations to relevant ED and inpatient teams. Consultations confirmed the presence or absence of cellulitis as the primary outcome and also noted the presence of any pseudocellulitis diagnoses either occurring concomitantly with or mimicking cellulitis as a secondary outcome.

Statistical Analysis—Patient characteristics were analyzed to identify factors independently associated with the diagnosis of cellulitis in cases affecting the lower extremities. Factors were recorded with categorical variables reported as counts and percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations. Univariate analyses between categorical variables or discretized continuous variables and cellulitis diagnosis were conducted via Fisher exact test to identify a preliminary set of potential risk factors. Continuous variables were discretized at multiple incremental values with the discretization most significantly associated with cellulitis diagnosis selected as a preliminary risk factor. Multivariate analyses involved using any objective preliminary factor meeting a significance threshold of P<.1 in univariate comparisons in a multivariate logistic regression model for prediction of cellulitis diagnosis with corresponding calculation of odds ratios with confidence intervals and receiver operating characteristic. Factors with confidence intervals that excluded 1 were considered significant independent predictors of cellulitis. Analyses were performed using Python version 3.8 (Python Software Foundation).

Results

Of 1359 patients screened for eligibility, 104 patients with presumed lower extremity cellulitis undergoing dermatology consultation were included in this study (Figure). The mean patient age (SD) was 60.4 (19.2) years, and 63.5% of patients were male. In the study population, 63 (60.6%) patients received a final diagnosis of cellulitis. The most common pseudocellulitis diagnosis identified was venous stasis dermatitis, which occurred in 12 (11.5%) patients with concomitant cellulitis and in 12 (11.5%) patients mimicking cellulitis (Table).

Univariate comparisons revealed a diverse set of historical, examination, and laboratory factors associated with cellulitis diagnosis. Diagnosis of cellulitis was associated with unilateral presentation, recent trauma to the affected site, and history of cellulitis or onychomycosis. Diagnosis of cellulitis also was associated with elevated white blood cell count, absolute neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, body mass index, hematocrit, and platelet count; age less than 75 years; and lower serum sodium and serum chloride levels. These were the independent factors included in the multivariate analysis, which consisted of a logistic regression model for prediction of cellulitis (eTable).

Multivariate logistic regression on all preliminary factors significantly associated with cellulitis diagnosis in univariate comparisons demonstrated leukocytosis, which was defined as having a white blood cell count exceeding 11,000/μL, unilateral presentation, history of onychomycosis, and trauma to the affected site as significant independent predictors of cellulitis diagnosis; history of cellulitis approached significance (eTable). Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis were the strongest predictors; having either of these factors had a sensitivity of 93.7% and a negative predictive value of 76.5%.

Comment

Importance of Identifying Pseudocellulitis—Successful diagnosis of cellulitis can be confounded by pseudocellulitis that can present concomitantly with or in lieu of cellulitis itself. Although cellulitis mostly affects the lower extremities in adults, pseudocellulitis also was common in this study population of patients with suspected lower extremity cellulitis, occurring both as a mimicker and concomitantly with cellulitis with substantial frequency. Notably, among patients with both venous stasis dermatitis and cellulitis diagnosed, most patients (n=10/12; 83.3%) had unilateral presentations of cellulitis as evidenced by signs and symptoms more notably affecting one lower extremity than the other. These findings suggest that certain pseudocellulitis diagnoses may predispose patients to cellulitis by disrupting the skin barrier, leading to bacterial infiltration; however, these pseudocellulitis diagnoses typically affect both lower extremities equally,1 and asymmetric involvement suggests the presence of overlying cellulitis. Furthermore, the most common pseudocellulitis entities found, such as venous stasis dermatitis, hematoma, and eczema, do not benefit from antibiotic treatment and require alternative therapy.1 Successful discrimination of these pseudocellulitis entities is critical to bolster proper antibiotic stewardship and discourage unnecessary hospitalization.

Independent Predictors of Cellulitis—Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis each emerged as strong independent predictors of cellulitis diagnosis in this study. Having either of these factors furthermore demonstrated high sensitivity and negative predictive value for cellulitis diagnosis. Other notable risk factors were history of onychomycosis, cellulitis, and trauma to the affected site. Prior studies have identified similar historical factors as predisposing patients to cellulitis.7-9 Interestingly, warmth of the affected area on physical examination emerged as strongly associated with cellulitis but was not included in the final predictive model because of its subjective determination. These factors may be especially important in diagnosing cellulitis in patients without concerning vital signs and with concomitant or prior pseudocellulitis.

Study Limitations—This study was limited to patients with uncomplicated presentations to emphasize discrimination of factors associated with cellulitis in the absence of suggestive signs of infection, such as vital sign abnormalities. Signs such as fever and tachypnea have been previously correlated to outpatient treatment failure and necessity for hospitalization.10-12 This study instead focused on patients without concerning vital signs to reduce confounding by such factors in more severe presentations that heighten suspicion for infection and increase likelihood of additional treatment measures. For such patients, suggestive historical factors, such as those discovered in this study, should be considered instead. Interestingly, increased age did not emerge as a significant predictor in this population in contrast to other predictive models that included patients with vital sign abnormalities. Notably, older patients tend to have more variable vital signs, especially in response to physiologic stressors such as infection.13 As such, age may serve as a proxy for vital sign abnormalities to some degree in such predictive models, leading to heightened suspicion for infection in older patients. This study demonstrated that in the absence of concerning vital signs, historical rather than demographic factors are more predictive of cellulitis.

Conclusion

Unilateral presentation and leukocytosis emerged as strong independent predictors of lower extremity cellulitis in patients with uncomplicated presentations. Having either of these factors had a sensitivity of 93.7% and a negative predictive value of 76.5%. Other factors such as history of cellulitis, onychomycosis, and recent trauma to the affected site emerged as additional predictors. These historical, examination, and laboratory characteristics may be especially useful for successful diagnosis of cellulitis in varied practice settings, including outpatient clinics and EDs.

- Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA. 2016;316:325-337.

- Gunderson CG, Cherry BM, Fisher A. Do patients with cellulitis need to be hospitalized? a systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality rates of inpatients with cellulitis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1553-1560.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St. John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hughey LC. The impact dermatologists can have on misdiagnosis of cellulitis and overuse of antibiotics: closing the gap. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1061-1062.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159.

- Björnsdóttir S, Gottfredsson M, Thórisdóttir AS, et al. Risk factors for acute cellulitis of the lower limb: a prospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1416-1422.

- Roujeau JC, Sigurgeirsson B, Korting HC, et al. Chronic dermatomycoses of the foot as risk factors for acute bacterial cellulitis of the leg: a case-control study. Dermatology. 2004;209:301-307.

- McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, et al. A predictive model of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a population-based cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:709-715.

- Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, et al. Predictors of oral antibiotic treatment failure for nonpurulent skin and soft tissue infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26:51-59.

- Peterson D, McLeod S, Woolfrey K, et al. Predictors of failure of empiric outpatient antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with uncomplicated cellulitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:526-531.

- Volz KA, Canham L, Kaplan E, et al. Identifying patients with cellulitis who are likely to require inpatient admission after a stay in an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:360-364.

- Chester JG, Rudolph JL. Vital signs in older patients: age-related changes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:337-343.

- Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: a review. JAMA. 2016;316:325-337.

- Gunderson CG, Cherry BM, Fisher A. Do patients with cellulitis need to be hospitalized? a systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality rates of inpatients with cellulitis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1553-1560.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St. John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- David CV, Chira S, Eells SJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy in patients admitted to hospitals with cellulitis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:1.

- Hughey LC. The impact dermatologists can have on misdiagnosis of cellulitis and overuse of antibiotics: closing the gap. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1061-1062.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:147-159.

- Björnsdóttir S, Gottfredsson M, Thórisdóttir AS, et al. Risk factors for acute cellulitis of the lower limb: a prospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1416-1422.

- Roujeau JC, Sigurgeirsson B, Korting HC, et al. Chronic dermatomycoses of the foot as risk factors for acute bacterial cellulitis of the leg: a case-control study. Dermatology. 2004;209:301-307.

- McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, et al. A predictive model of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a population-based cohort. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:709-715.

- Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, et al. Predictors of oral antibiotic treatment failure for nonpurulent skin and soft tissue infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26:51-59.

- Peterson D, McLeod S, Woolfrey K, et al. Predictors of failure of empiric outpatient antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with uncomplicated cellulitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:526-531.

- Volz KA, Canham L, Kaplan E, et al. Identifying patients with cellulitis who are likely to require inpatient admission after a stay in an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:360-364.

- Chester JG, Rudolph JL. Vital signs in older patients: age-related changes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:337-343.

Practice Points

- Unilateral involvement and leukocytosis are both highly predictive of lower extremity cellulitis in uncomplicated presentations.

- Historical factors such as history of onychomycosis and trauma to the affected site are more predictive of lower extremity cellulitis than demographic factors such as age in uncomplicated presentations of cellulitis.