User login

Richard Quinn is an award-winning journalist with 15 years’ experience. He has worked at the Asbury Park Press in New Jersey and The Virginian-Pilot in Norfolk, Va., and currently is managing editor for a leading commercial real estate publication. His freelance work has appeared in The Jewish State, The Hospitalist, The Rheumatologist, ACEP Now, and ENT Today. He lives in New Jersey with his wife and three cats.

HM17’s ‘must-see sessions’

LAS VEGAS — Not to sound like a Sin City come on, but pick a course, any course.

No, seriously.

Hospitalists and other attendees at the Hospitalist Medicine 2017 meeting next month will do well to figure out what sessions they want to attend before arriving at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. This 4-day Super Bowl of hospital medicine prides itself on offering more than any attendee can find time for. This year is no exception, as the annual meeting has added five new educational tracks: High-Value Care, Clinical Updates, Health Policy, Diagnostic Reasoning, and Medical Education.

The committee does its job to fill the meeting with best-in-class educational sessions. Here are some of the group’s recommendations for this year’s meeting:

1. “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Opioid Epidemic” – Tuesday, May 2; 1:35 p.m.–2:35 p.m.

2. “Opioids for Acute Pain Management in the Seriously Ill – How to Safely Prescribe” – Wednesday, May 3; 2:50 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

3. “Non-opiate Pain Management for the Hospitalist” – Wednesday, May 3; 4:20 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Elizabeth Cook, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division of Medical Associates of Central Virginia in Lynchburg, said, “The historical emphasis on pain control has helped contributed to the current epidemic of opioid abuse, overdoses, and deaths. Hospitalists have a need to use these medications for care of the hospitalized patient but have an important part to play in leading the way to appropriate use and patient education regarding the dangers of these medications. These sessions will provide hospitalists with some tools to use in beginning to effect a shift in pain management strategies and responsible use of narcotic pain medications.”

Miguel Angel Villagra, MD, FACP, FHM, hospitalist department program medical director at White River Medical Center in Batesville, Ark., said, “As primary front-line providers in the acute care setting, we face the everyday struggles in the management of chronic opioid users. Acquiring some general guidelines can help us tailor our approach within an ethical focus to improve the care of this population.”

Sarah Stella, MD, an academic hospitalist at Denver Health, said, “This is a crucial and timely topic. Hospitalists have had a hand in perpetuating the opioid epidemic and can play an important role in helping to end it. In this regard, there are many opportunities to do good, such as judicious prescribing and tapering medications for acute pain, starting eligible patients on Suboxone [buprenorphine] in-house, and arranging substance abuse treatment follow-up.”

4. “Focus on POCUS - Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Hospitalists” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:35 a.m.

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center/Baystate Children’s Hospital, Springfield, Mass., said, “This is the first pediatric POCUS session offered at SHM ever. And it does not require an additional cost ... the pediatric track is critically important, as a substantial number of athlete attendees are either Peds or MedPeds. I think SHM aims to create a pediatric track that discusses topics that are less covered in other meetings, such as the value equation and issues facing women leaders in HM.”

6. “Foundations of a Hospital Medicine Telemedicine Program” – Wednesday, May 3; 415 p.m.–5:20 p.m.

Dr. Villagra added, “Telemedicine is a new innovative technology with the promise of overcoming geographical barriers to health care providers. A lot of new companies and software development has made this technology more user/patient friendly.”

7. “Hot Topics in Health Policy for Hospitalists” – Thursday, May 4; 7:40 a.m.–8:35 a.m.

8. “The Impact of the New Administration on Health Care Reform” – Thursday, May 4; 8:45 a.m.–9:40 a.m.

9. “Health Care Payment Reform for Hospitalist 2017: Tips for MIPS and Beyond” – Thursday, May 4; 9:50 a.m.–10:45 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “As a safety-net hospitalist in Colorado, a state which largely expanded Medicare under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), I am concerned about the impact repealing the ACA would have on my patients as well as on safety-net hospitals such as my own. I hope that these sessions will increase my understanding of the issues and my ability to advocate for my patients.”

Dr. Cook said, “The U.S. government is functioning in historically unprecedented ways with major shifts in health care policy expected to occur over the next 4 years. It is essential that physician leaders play an active role in shaping the discussion around these important topics ... hospitalists have an opportunity to provide leadership in this arena, and these sessions will help participants to build the knowledge about these complex issues that is crucial to being an active part of the dialogue.”

10. “Workshop: Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput” – Thursday, May 4; 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “Recently, I was appointed to a leadership role on a major initiative to improve hospital patient flow at my institution. We are concentrating on several different areas, including avoidable hospitalizations, preventable excess days, delayed discharges, and variable access to services. I was excited to see a workshop this year dedicated to how hospitalists can successfully lead such initiatives. I will definitely be attending this session as I am interested in what others are doing in their institutions to creatively overcome patient flow challenges.”

11. “Hospitalist Careers: So Many Options” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:15 a.m.

Dr. Villagra said, “Hospital medicine has so many pathways for a full career development and is not a pit stop before fellowship. Early- and mid-career hospitalists can benefit from interactions with senior hospitalists for the understanding of what hospital medicine has to offer for their professional growth.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

LAS VEGAS — Not to sound like a Sin City come on, but pick a course, any course.

No, seriously.

Hospitalists and other attendees at the Hospitalist Medicine 2017 meeting next month will do well to figure out what sessions they want to attend before arriving at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. This 4-day Super Bowl of hospital medicine prides itself on offering more than any attendee can find time for. This year is no exception, as the annual meeting has added five new educational tracks: High-Value Care, Clinical Updates, Health Policy, Diagnostic Reasoning, and Medical Education.

The committee does its job to fill the meeting with best-in-class educational sessions. Here are some of the group’s recommendations for this year’s meeting:

1. “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Opioid Epidemic” – Tuesday, May 2; 1:35 p.m.–2:35 p.m.

2. “Opioids for Acute Pain Management in the Seriously Ill – How to Safely Prescribe” – Wednesday, May 3; 2:50 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

3. “Non-opiate Pain Management for the Hospitalist” – Wednesday, May 3; 4:20 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Elizabeth Cook, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division of Medical Associates of Central Virginia in Lynchburg, said, “The historical emphasis on pain control has helped contributed to the current epidemic of opioid abuse, overdoses, and deaths. Hospitalists have a need to use these medications for care of the hospitalized patient but have an important part to play in leading the way to appropriate use and patient education regarding the dangers of these medications. These sessions will provide hospitalists with some tools to use in beginning to effect a shift in pain management strategies and responsible use of narcotic pain medications.”

Miguel Angel Villagra, MD, FACP, FHM, hospitalist department program medical director at White River Medical Center in Batesville, Ark., said, “As primary front-line providers in the acute care setting, we face the everyday struggles in the management of chronic opioid users. Acquiring some general guidelines can help us tailor our approach within an ethical focus to improve the care of this population.”

Sarah Stella, MD, an academic hospitalist at Denver Health, said, “This is a crucial and timely topic. Hospitalists have had a hand in perpetuating the opioid epidemic and can play an important role in helping to end it. In this regard, there are many opportunities to do good, such as judicious prescribing and tapering medications for acute pain, starting eligible patients on Suboxone [buprenorphine] in-house, and arranging substance abuse treatment follow-up.”

4. “Focus on POCUS - Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Hospitalists” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:35 a.m.

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center/Baystate Children’s Hospital, Springfield, Mass., said, “This is the first pediatric POCUS session offered at SHM ever. And it does not require an additional cost ... the pediatric track is critically important, as a substantial number of athlete attendees are either Peds or MedPeds. I think SHM aims to create a pediatric track that discusses topics that are less covered in other meetings, such as the value equation and issues facing women leaders in HM.”

6. “Foundations of a Hospital Medicine Telemedicine Program” – Wednesday, May 3; 415 p.m.–5:20 p.m.

Dr. Villagra added, “Telemedicine is a new innovative technology with the promise of overcoming geographical barriers to health care providers. A lot of new companies and software development has made this technology more user/patient friendly.”

7. “Hot Topics in Health Policy for Hospitalists” – Thursday, May 4; 7:40 a.m.–8:35 a.m.

8. “The Impact of the New Administration on Health Care Reform” – Thursday, May 4; 8:45 a.m.–9:40 a.m.

9. “Health Care Payment Reform for Hospitalist 2017: Tips for MIPS and Beyond” – Thursday, May 4; 9:50 a.m.–10:45 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “As a safety-net hospitalist in Colorado, a state which largely expanded Medicare under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), I am concerned about the impact repealing the ACA would have on my patients as well as on safety-net hospitals such as my own. I hope that these sessions will increase my understanding of the issues and my ability to advocate for my patients.”

Dr. Cook said, “The U.S. government is functioning in historically unprecedented ways with major shifts in health care policy expected to occur over the next 4 years. It is essential that physician leaders play an active role in shaping the discussion around these important topics ... hospitalists have an opportunity to provide leadership in this arena, and these sessions will help participants to build the knowledge about these complex issues that is crucial to being an active part of the dialogue.”

10. “Workshop: Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput” – Thursday, May 4; 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “Recently, I was appointed to a leadership role on a major initiative to improve hospital patient flow at my institution. We are concentrating on several different areas, including avoidable hospitalizations, preventable excess days, delayed discharges, and variable access to services. I was excited to see a workshop this year dedicated to how hospitalists can successfully lead such initiatives. I will definitely be attending this session as I am interested in what others are doing in their institutions to creatively overcome patient flow challenges.”

11. “Hospitalist Careers: So Many Options” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:15 a.m.

Dr. Villagra said, “Hospital medicine has so many pathways for a full career development and is not a pit stop before fellowship. Early- and mid-career hospitalists can benefit from interactions with senior hospitalists for the understanding of what hospital medicine has to offer for their professional growth.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

LAS VEGAS — Not to sound like a Sin City come on, but pick a course, any course.

No, seriously.

Hospitalists and other attendees at the Hospitalist Medicine 2017 meeting next month will do well to figure out what sessions they want to attend before arriving at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. This 4-day Super Bowl of hospital medicine prides itself on offering more than any attendee can find time for. This year is no exception, as the annual meeting has added five new educational tracks: High-Value Care, Clinical Updates, Health Policy, Diagnostic Reasoning, and Medical Education.

The committee does its job to fill the meeting with best-in-class educational sessions. Here are some of the group’s recommendations for this year’s meeting:

1. “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Opioid Epidemic” – Tuesday, May 2; 1:35 p.m.–2:35 p.m.

2. “Opioids for Acute Pain Management in the Seriously Ill – How to Safely Prescribe” – Wednesday, May 3; 2:50 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

3. “Non-opiate Pain Management for the Hospitalist” – Wednesday, May 3; 4:20 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Elizabeth Cook, MD, medical director of the hospitalist division of Medical Associates of Central Virginia in Lynchburg, said, “The historical emphasis on pain control has helped contributed to the current epidemic of opioid abuse, overdoses, and deaths. Hospitalists have a need to use these medications for care of the hospitalized patient but have an important part to play in leading the way to appropriate use and patient education regarding the dangers of these medications. These sessions will provide hospitalists with some tools to use in beginning to effect a shift in pain management strategies and responsible use of narcotic pain medications.”

Miguel Angel Villagra, MD, FACP, FHM, hospitalist department program medical director at White River Medical Center in Batesville, Ark., said, “As primary front-line providers in the acute care setting, we face the everyday struggles in the management of chronic opioid users. Acquiring some general guidelines can help us tailor our approach within an ethical focus to improve the care of this population.”

Sarah Stella, MD, an academic hospitalist at Denver Health, said, “This is a crucial and timely topic. Hospitalists have had a hand in perpetuating the opioid epidemic and can play an important role in helping to end it. In this regard, there are many opportunities to do good, such as judicious prescribing and tapering medications for acute pain, starting eligible patients on Suboxone [buprenorphine] in-house, and arranging substance abuse treatment follow-up.”

4. “Focus on POCUS - Introduction to Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Hospitalists” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:35 a.m.

Weijen Chang, MD, SFHM, FAAP, chief of the division of pediatric hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center/Baystate Children’s Hospital, Springfield, Mass., said, “This is the first pediatric POCUS session offered at SHM ever. And it does not require an additional cost ... the pediatric track is critically important, as a substantial number of athlete attendees are either Peds or MedPeds. I think SHM aims to create a pediatric track that discusses topics that are less covered in other meetings, such as the value equation and issues facing women leaders in HM.”

6. “Foundations of a Hospital Medicine Telemedicine Program” – Wednesday, May 3; 415 p.m.–5:20 p.m.

Dr. Villagra added, “Telemedicine is a new innovative technology with the promise of overcoming geographical barriers to health care providers. A lot of new companies and software development has made this technology more user/patient friendly.”

7. “Hot Topics in Health Policy for Hospitalists” – Thursday, May 4; 7:40 a.m.–8:35 a.m.

8. “The Impact of the New Administration on Health Care Reform” – Thursday, May 4; 8:45 a.m.–9:40 a.m.

9. “Health Care Payment Reform for Hospitalist 2017: Tips for MIPS and Beyond” – Thursday, May 4; 9:50 a.m.–10:45 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “As a safety-net hospitalist in Colorado, a state which largely expanded Medicare under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), I am concerned about the impact repealing the ACA would have on my patients as well as on safety-net hospitals such as my own. I hope that these sessions will increase my understanding of the issues and my ability to advocate for my patients.”

Dr. Cook said, “The U.S. government is functioning in historically unprecedented ways with major shifts in health care policy expected to occur over the next 4 years. It is essential that physician leaders play an active role in shaping the discussion around these important topics ... hospitalists have an opportunity to provide leadership in this arena, and these sessions will help participants to build the knowledge about these complex issues that is crucial to being an active part of the dialogue.”

10. “Workshop: Hospitalists as Leaders in Patient Flow and Hospital Throughput” – Thursday, May 4; 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Dr. Stella said, “Recently, I was appointed to a leadership role on a major initiative to improve hospital patient flow at my institution. We are concentrating on several different areas, including avoidable hospitalizations, preventable excess days, delayed discharges, and variable access to services. I was excited to see a workshop this year dedicated to how hospitalists can successfully lead such initiatives. I will definitely be attending this session as I am interested in what others are doing in their institutions to creatively overcome patient flow challenges.”

11. “Hospitalist Careers: So Many Options” – Tuesday, May 2; 10:35 a.m.–11:15 a.m.

Dr. Villagra said, “Hospital medicine has so many pathways for a full career development and is not a pit stop before fellowship. Early- and mid-career hospitalists can benefit from interactions with senior hospitalists for the understanding of what hospital medicine has to offer for their professional growth.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Fellows and Awards of Excellence

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Vineet Arora, MD, understands the unique value of being named one of this year’s three Masters in Hospital Medicine. It’s an honor bestowed for hospitalists, by hospitalists.

“I take a lot of pride in an honor determined by peers,” said Dr. Arora, an academic hospitalist at University of Chicago Medicine. “While peers are often the biggest support you receive in your professional career, because they are in the trenches with you, they can also be your best critics. That is especially true of the type of work that I do, which relies on the buy-in of frontline clinicians – including hospitalists and trainees – to achieve better patient care and education.”

The designation of new Masters in Hospital Medicine is a major moment at SHM’s annual meeting. The 2017 list of awardees is headlined by Dr. Arora and the other MHM designees: former SHM President Burke Kealey, MD, and Richard Slataper, MD, who was heavily involved with the National Association of Inpatient Physicians, a predecessor to SHM. The three new masters bring to 24 the number of MHMs the society has named since unveiling the honor in 2010.

Dr. Arora understands that after 20 years as a specialty, just two dozen practitioners have reached hospital medicine’s highest professional distinction.

“I think of ‘mastery’ as someone who has achieved the highest level of expertise in a field, so an honor like Master in Hospital Medicine definitely means a lot to me,” she said. “Especially given the prior recipients of this honor, and the importance of SHM in my own professional growth and development since I was a trainee.”

In addition to the top honor, HM17 will see the induction of 159 Fellows in Hospital Medicine (FHM) and 58 Senior Fellows in Hospital Medicine (SFHM). This year’s fellows join the thousands of physicians and nonphysician providers (NPPs) that have attained the distinction.

SHM also bestows its annual Awards of Excellence (past winners listed here include Dr. Arora and Dr. Kealey) that recognize practitioners across skill sets. The awards are meant to honor SHM members “whose exemplary contributions to the hospital medicine movement deserve acknowledgment and respect,” according to the society’s website.

The 2017 Award winners include:

• Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement: Johnston Memorial Hospital in Abingdon, Va.

• Excellence in Research: Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, SFHM.

• Excellence in Teaching: Steven Cohn, MD, FACP, SFHM.

• Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians: Michael McFall.

• Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine: Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM.

• Clinical Excellence: Barbara Slawski, MD.

• Excellence in Humanitarian Services: Jonathan Crocker, MD, FHM.

Dr. Arora, who has served on the SHM committee that analyzes all nominees for the annual awards, recognizes the value of honoring these high-achieving clinicians.

“There is great value to having our specialty society recognize members in different ways,” she said “The awards of excellence serve as a wonderful reminder of the incredible impact that hospitalists have in many diverse ways … while having the distinction of a fellow or senior fellow serves as a nice benchmark to which new hospitalists can aspire and gain recognition as they emerge as leaders in the field.”

Networking: A skill worth learning

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Ivan Misner once spent one week on Necker Island – the tony 74-acre island in the British Virgin Islands that is entirely owned by billionaire Sir Richard Branson – because he met a guy at a convention.

And Misner is really good at networking.

“I stayed in touch with the person, and when there was an opportunity, I got invited to this incredible ethics program on Necker where I had a chance to meet Sir Richard. It all comes from building relationships with people,” said Misner, founder and chairman of BNI (Business Network International), a 32-year-old global business networking platform based in Charlotte, N.C., that has led CNN to call him “the father of modern networking.”

The why doesn’t matter most, Misner said. A person’s approach to networking, regardless of the hoped-for outcome, should always remain the same.

“The two key themes that I would address would be the mindset and the skill set,” he said.

The mindset is making sure one’s approach doesn’t “feel artificial,” Misner said.

“A lot of people, when they go to some kind of networking environment, they feel like they need to get a shower afterwards and think, ‘Ick, I don’t like that,’” Misner said. “The best way to become an effective networker is to go to networking events with the idea of being willing to help people and really believe in that and practice that. I’ve been doing this a long time and where I see it done wrong is when people use face-to-face networking as a cold-calling opportunity.”

Instead, Misner suggests, approach networking like it is “more about farming than it is about hunting.” Cultivate relationships with time and tenacity and don’t just expect them to be instant. Once the approach is set, Misner has a process he calls VCP – visibility, credibility, and profitability.

“Credibility is what takes time,” he said. “You really want to build credibility with somebody. It doesn’t happen overnight. People have to get to know, like, and trust you. It is the most time consuming portion of the VCP process... then, and only then, can you get to profitability. Where people know who you are, they know what you do, they know you’re good at it, and they’re willing to refer a business to you. They’re willing to put you in touch with other people.”

But even when a relationship gets struck early on, networking must be more than a few minutes at an SHM conference, a local chapter mixer, or a medical school reunion.

It’s the follow-up that makes all the impact. Misner calls that process 24/7/30.

Within 24 hours, send the person a note. An email, or even the seemingly lost art of a hand-written card. (If your handwriting is sloppy, Misner often recommends services that will send out legible notes on your behalf.)

Within a week, connect on social media. Focus on whatever platform that person has on their business card, or email signature. Connect where they like to connect to show the person you’re willing to make the effort.

Within a month, reach out to the person and set a time to talk, either face-to-face or via a telecommunication service like Skype.

“It’s these touch points that you make with people that build the relationship,” Misner said. “Without building a real relationship, there is almost no value in the networking effort because you basically are just waiting to stumble upon opportunities as opposed to building relationships and opportunities. It has to be more than just bumping into somebody at a meeting... otherwise you’re really wasting your time.”

Misner also notes that the point of networking is collaboration at some point. That partnership could be working on a research paper or a pilot project. Or just even getting a phone call returned to talk about something important to you.

“It’s not what you know or who you know, it’s how well you know each other that really counts,” he added. “And meeting people at events like HM17 is only the start of the process. It’s not the end of the process by any means, if you want to do this well.”

Tips for significant others

Heather Howell has gotten pretty good at making the most out of SHM’s annual meeting. It’s not that she has a system for wending through scores of educational offerings, a knack for interpersonal networking or award-winning research.

It’s that she’s the spouse of former SHM President Eric Howell, MD, MHM, and a long-time annual meeting attendee with her husband.

Welcome to HM17, family style. While thousands of hospitalists, nonphysician practitioners, and other attendees swarm the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino for a four-day crash course on all things hospital medicine, thousands more family members tag along. Husbands and wives, like Mrs. Howell, and, in years past, children like the Howells’ 14-year-old son Mason and 12-year-old daughter Anna. The kids aren’t traveling this year, which is tip No. 1.

“It gets harder as they’re older to drag them to San Diego or Vegas in the middle of a school year, which is when [the annual meeting] is usually held,” said Mrs. Howell, whose day job is as a real estate agent.

Tip No. 2? Make friends the first time around. Maybe it’s with spouses of other physicians from your significant other’s practice. Or maybe it’s with your spouse’s old friends from past jobs. For Mrs. Howell, it’s SHM staff and the families of board members her husband has worked with for years.

“I’ve been doing it for so long that I’ve met a lot of the other [spouses] that do go,” she said. “Usually, if Eric is in meetings all day, I will connect with some of the other spouses and we will go on excursions that are in that town. There is usually so much going on.”

Las Vegas is certainly no exception. In fact, SHM has a dedicated web page recommending family activities. Recommendations include hanging out at the 11-acre Mandalay Beach, which encompasses 2,700 tons of sand, three pools and a lazy river. There’s also the popular Shark Reef Aquarium, a 1.6 million-gallon saltwater habitat with some 2,000 creatures.

Mrs. Howell says excursions further afield could include Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, which lies a 25-minute drive from the convention, or the Grand Canyon, which is about two hours east. But planning too much, especially with children, can become a challenge.

“When I arrive, there always seems to be a group of people that are going to do things,” Mrs. Howell said. “It’s very easy to hook up with the other spouses that aren’t involved in the meeting. We always tend to find each other.”

Heather Howell has gotten pretty good at making the most out of SHM’s annual meeting. It’s not that she has a system for wending through scores of educational offerings, a knack for interpersonal networking or award-winning research.

It’s that she’s the spouse of former SHM President Eric Howell, MD, MHM, and a long-time annual meeting attendee with her husband.

Welcome to HM17, family style. While thousands of hospitalists, nonphysician practitioners, and other attendees swarm the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino for a four-day crash course on all things hospital medicine, thousands more family members tag along. Husbands and wives, like Mrs. Howell, and, in years past, children like the Howells’ 14-year-old son Mason and 12-year-old daughter Anna. The kids aren’t traveling this year, which is tip No. 1.

“It gets harder as they’re older to drag them to San Diego or Vegas in the middle of a school year, which is when [the annual meeting] is usually held,” said Mrs. Howell, whose day job is as a real estate agent.

Tip No. 2? Make friends the first time around. Maybe it’s with spouses of other physicians from your significant other’s practice. Or maybe it’s with your spouse’s old friends from past jobs. For Mrs. Howell, it’s SHM staff and the families of board members her husband has worked with for years.

“I’ve been doing it for so long that I’ve met a lot of the other [spouses] that do go,” she said. “Usually, if Eric is in meetings all day, I will connect with some of the other spouses and we will go on excursions that are in that town. There is usually so much going on.”

Las Vegas is certainly no exception. In fact, SHM has a dedicated web page recommending family activities. Recommendations include hanging out at the 11-acre Mandalay Beach, which encompasses 2,700 tons of sand, three pools and a lazy river. There’s also the popular Shark Reef Aquarium, a 1.6 million-gallon saltwater habitat with some 2,000 creatures.

Mrs. Howell says excursions further afield could include Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, which lies a 25-minute drive from the convention, or the Grand Canyon, which is about two hours east. But planning too much, especially with children, can become a challenge.

“When I arrive, there always seems to be a group of people that are going to do things,” Mrs. Howell said. “It’s very easy to hook up with the other spouses that aren’t involved in the meeting. We always tend to find each other.”

Heather Howell has gotten pretty good at making the most out of SHM’s annual meeting. It’s not that she has a system for wending through scores of educational offerings, a knack for interpersonal networking or award-winning research.

It’s that she’s the spouse of former SHM President Eric Howell, MD, MHM, and a long-time annual meeting attendee with her husband.

Welcome to HM17, family style. While thousands of hospitalists, nonphysician practitioners, and other attendees swarm the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino for a four-day crash course on all things hospital medicine, thousands more family members tag along. Husbands and wives, like Mrs. Howell, and, in years past, children like the Howells’ 14-year-old son Mason and 12-year-old daughter Anna. The kids aren’t traveling this year, which is tip No. 1.

“It gets harder as they’re older to drag them to San Diego or Vegas in the middle of a school year, which is when [the annual meeting] is usually held,” said Mrs. Howell, whose day job is as a real estate agent.

Tip No. 2? Make friends the first time around. Maybe it’s with spouses of other physicians from your significant other’s practice. Or maybe it’s with your spouse’s old friends from past jobs. For Mrs. Howell, it’s SHM staff and the families of board members her husband has worked with for years.

“I’ve been doing it for so long that I’ve met a lot of the other [spouses] that do go,” she said. “Usually, if Eric is in meetings all day, I will connect with some of the other spouses and we will go on excursions that are in that town. There is usually so much going on.”

Las Vegas is certainly no exception. In fact, SHM has a dedicated web page recommending family activities. Recommendations include hanging out at the 11-acre Mandalay Beach, which encompasses 2,700 tons of sand, three pools and a lazy river. There’s also the popular Shark Reef Aquarium, a 1.6 million-gallon saltwater habitat with some 2,000 creatures.

Mrs. Howell says excursions further afield could include Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area, which lies a 25-minute drive from the convention, or the Grand Canyon, which is about two hours east. But planning too much, especially with children, can become a challenge.

“When I arrive, there always seems to be a group of people that are going to do things,” Mrs. Howell said. “It’s very easy to hook up with the other spouses that aren’t involved in the meeting. We always tend to find each other.”

HM17: Plenaries – Conway and DeSalvo

The first two plenary addresses at HM17 are focused on policy at a time when the dynamically evolving U.S. health care delivery system may seem daunting, opaque, and labyrinthine.

Some might view the health care landscape as hopelessly confusing. Yet both of the keynote speakers use the same word for what they hope to leave their listeners with: optimism.

“Though it feels uncertain in the headlines, the reality is that the health care world feels pretty united in that we need to continue the progress we’ve made on moving away from the fee-for-service model and to let people practice medicine the way they want – to work better as teams and focus on patients and outcomes,” said Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc, former acting assistant secretary for health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and former national coordinator for health information technology.

“I would view it as an opportunity as well,” said Dr. Conway, who still moonlights as a pediatric academic hospitalist on weekends in greater Washington, D.C. “I think the pieces are coming together. Everything from data, to new payment models, to the MACRA Medicare Physician payment legislation, really suggests a time of positive change.”

Dr. DeSalvo, a former political appointee, joined HHS as the national coordinator for health information technology in 2014 and soon thereafter assumed the acting assistant secretary role. Dr. Conway has attained one of the country’s highest-ranking public health care jobs since joining CMS in 2011. He retained the top post at CMS while President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the agency, Seema Verma, awaited a confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate. Dr. Conway’s prior title was principal deputy administrator and CMS chief medical officer.

“I don’t want people to lose sight of the fact that there’s this entire care system that everybody’s working and innovating in every day, trying to find more efficient, effective ways to get better outcomes,” she said. “Hospitalists, quite frankly, have been leading that for their entire existence. They really understand in great granular detail what it takes.”

Dr. DeSalvo believes that the progress of the past 5 years has established a path that must be followed. The public sector move away from fee-for-service has combined with emerging technology platforms to create a new age where physicians and insurers can judge, in real time, how well care is working.

“We’re now in a feedback loop where we can say – ‘When we’ve built a care system like this or when we pay this way, we are actually seeing improved outcomes’ – and change doesn’t take as long,” Dr. DeSalvo said.

Dr. Conway, whose working title for his speech is “Health care System Transformation,” said hospitalists should be encouraged by how well the field has already adapted to the proliferation of accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing (VBP), alternative payment models (APM), and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015. He noted that, as innovations lead to better and more coordinated patient care, hospitalists, patients, and hospitals would all benefit.

“I want to leave people with the idea that value-based payment innovation and delivery system reform will continue to be critical aspects of improving our health system,” he said. “I also want hospitalists to continue to stay engaged with these new payment models, help lead them, and provide better patient care as a part of them.”

The first two plenary addresses at HM17 are focused on policy at a time when the dynamically evolving U.S. health care delivery system may seem daunting, opaque, and labyrinthine.

Some might view the health care landscape as hopelessly confusing. Yet both of the keynote speakers use the same word for what they hope to leave their listeners with: optimism.

“Though it feels uncertain in the headlines, the reality is that the health care world feels pretty united in that we need to continue the progress we’ve made on moving away from the fee-for-service model and to let people practice medicine the way they want – to work better as teams and focus on patients and outcomes,” said Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc, former acting assistant secretary for health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and former national coordinator for health information technology.

“I would view it as an opportunity as well,” said Dr. Conway, who still moonlights as a pediatric academic hospitalist on weekends in greater Washington, D.C. “I think the pieces are coming together. Everything from data, to new payment models, to the MACRA Medicare Physician payment legislation, really suggests a time of positive change.”

Dr. DeSalvo, a former political appointee, joined HHS as the national coordinator for health information technology in 2014 and soon thereafter assumed the acting assistant secretary role. Dr. Conway has attained one of the country’s highest-ranking public health care jobs since joining CMS in 2011. He retained the top post at CMS while President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the agency, Seema Verma, awaited a confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate. Dr. Conway’s prior title was principal deputy administrator and CMS chief medical officer.

“I don’t want people to lose sight of the fact that there’s this entire care system that everybody’s working and innovating in every day, trying to find more efficient, effective ways to get better outcomes,” she said. “Hospitalists, quite frankly, have been leading that for their entire existence. They really understand in great granular detail what it takes.”

Dr. DeSalvo believes that the progress of the past 5 years has established a path that must be followed. The public sector move away from fee-for-service has combined with emerging technology platforms to create a new age where physicians and insurers can judge, in real time, how well care is working.

“We’re now in a feedback loop where we can say – ‘When we’ve built a care system like this or when we pay this way, we are actually seeing improved outcomes’ – and change doesn’t take as long,” Dr. DeSalvo said.

Dr. Conway, whose working title for his speech is “Health care System Transformation,” said hospitalists should be encouraged by how well the field has already adapted to the proliferation of accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing (VBP), alternative payment models (APM), and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015. He noted that, as innovations lead to better and more coordinated patient care, hospitalists, patients, and hospitals would all benefit.

“I want to leave people with the idea that value-based payment innovation and delivery system reform will continue to be critical aspects of improving our health system,” he said. “I also want hospitalists to continue to stay engaged with these new payment models, help lead them, and provide better patient care as a part of them.”

The first two plenary addresses at HM17 are focused on policy at a time when the dynamically evolving U.S. health care delivery system may seem daunting, opaque, and labyrinthine.

Some might view the health care landscape as hopelessly confusing. Yet both of the keynote speakers use the same word for what they hope to leave their listeners with: optimism.

“Though it feels uncertain in the headlines, the reality is that the health care world feels pretty united in that we need to continue the progress we’ve made on moving away from the fee-for-service model and to let people practice medicine the way they want – to work better as teams and focus on patients and outcomes,” said Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc, former acting assistant secretary for health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and former national coordinator for health information technology.

“I would view it as an opportunity as well,” said Dr. Conway, who still moonlights as a pediatric academic hospitalist on weekends in greater Washington, D.C. “I think the pieces are coming together. Everything from data, to new payment models, to the MACRA Medicare Physician payment legislation, really suggests a time of positive change.”

Dr. DeSalvo, a former political appointee, joined HHS as the national coordinator for health information technology in 2014 and soon thereafter assumed the acting assistant secretary role. Dr. Conway has attained one of the country’s highest-ranking public health care jobs since joining CMS in 2011. He retained the top post at CMS while President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the agency, Seema Verma, awaited a confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate. Dr. Conway’s prior title was principal deputy administrator and CMS chief medical officer.

“I don’t want people to lose sight of the fact that there’s this entire care system that everybody’s working and innovating in every day, trying to find more efficient, effective ways to get better outcomes,” she said. “Hospitalists, quite frankly, have been leading that for their entire existence. They really understand in great granular detail what it takes.”

Dr. DeSalvo believes that the progress of the past 5 years has established a path that must be followed. The public sector move away from fee-for-service has combined with emerging technology platforms to create a new age where physicians and insurers can judge, in real time, how well care is working.

“We’re now in a feedback loop where we can say – ‘When we’ve built a care system like this or when we pay this way, we are actually seeing improved outcomes’ – and change doesn’t take as long,” Dr. DeSalvo said.

Dr. Conway, whose working title for his speech is “Health care System Transformation,” said hospitalists should be encouraged by how well the field has already adapted to the proliferation of accountable care organizations (ACOs), value-based purchasing (VBP), alternative payment models (APM), and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015. He noted that, as innovations lead to better and more coordinated patient care, hospitalists, patients, and hospitals would all benefit.

“I want to leave people with the idea that value-based payment innovation and delivery system reform will continue to be critical aspects of improving our health system,” he said. “I also want hospitalists to continue to stay engaged with these new payment models, help lead them, and provide better patient care as a part of them.”

Don’t assume work is sole burnout determinant

Physician burnout is almost always linked to issues at work. Blame is placed on added duties piled onto a to-do list that barely makes enough time for prolonged patient interaction in the first place. Fault is laid upon the hours and hours per week – or even per day – wasted on cumbersome data entry into bulky electronic health record (EHR) systems.

But Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician and burnout coach/consultant, says burnout should not be viewed as job specific. “To say that burnout is always about work is absolutely an error,” said Dr. Drummond, whose website is www.thehappymd.com. “You can have people flame out spectacularly at work and nothing has changed about work at all. It’s because something’s going on at home that’s made it impossible to recharge on their time off. And, that list of recharge-blocking issues is huge.”

Money problems, marital problems, family problems: Dr. Drummond says any and all of those issues can eliminate the doctor’s ability to recharge at home.

“The strain of your practice continues, but now without the ability to balance your energy with some recovery when you’re away from the hospital, burnout can come on very rapidly,” he said. “So when you see a colleague flaming out at work, one of the questions you must ask is, “How is it going at home?” You may be the first to learn their spouse left them 2 weeks ago.”

Dr. Drummond’s advice is: Don’t always blame the stresses of work. Build your recharge strategy (rest, hobbies, date nights) and make sure you maintain your recharge capabilities.

“Ideally, with a hospitalist-type schedule, when you’re on you’re on and when you’re off you’re off,” he said. “It should be easier to create that boundary for hospitalists than other specialists who chart from home or are on call.

The “off switch” on your doctor programming is called a boundary ritual. Pick some activity you do on the way home from work, saying to yourself ‘with this action, I am coming all the way home.’ It can be as simple as a deep releasing breath as you step out of your car at home. Make sure you take that breath and let it all go before you walk into the house after each shift.”

Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout, refers to this phenomenon as “work-home interference.” On the bright side for hospitalists, he says, is that aspects of HM work schedules may help mitigate burnout; some work can be left at the hospital when shifts end, rather than following physicians into their home lives.

But Dr. West acknowledged that the rigors of the traditional 7-on/7-off schedule come with their own unique burnout challenges for hospitalists as well.

“A hospitalist can say ‘Well, jeez, I’m on nights for the next week, and that means during the day I’m sleeping and recovering,’” Dr. West explained. “Well, how do you maintain a family life for that period of time when you’re basically off-cycle with your family? There are those kinds of stressors. It’s a mixed bag for hospitalists there.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Physician burnout is almost always linked to issues at work. Blame is placed on added duties piled onto a to-do list that barely makes enough time for prolonged patient interaction in the first place. Fault is laid upon the hours and hours per week – or even per day – wasted on cumbersome data entry into bulky electronic health record (EHR) systems.

But Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician and burnout coach/consultant, says burnout should not be viewed as job specific. “To say that burnout is always about work is absolutely an error,” said Dr. Drummond, whose website is www.thehappymd.com. “You can have people flame out spectacularly at work and nothing has changed about work at all. It’s because something’s going on at home that’s made it impossible to recharge on their time off. And, that list of recharge-blocking issues is huge.”

Money problems, marital problems, family problems: Dr. Drummond says any and all of those issues can eliminate the doctor’s ability to recharge at home.

“The strain of your practice continues, but now without the ability to balance your energy with some recovery when you’re away from the hospital, burnout can come on very rapidly,” he said. “So when you see a colleague flaming out at work, one of the questions you must ask is, “How is it going at home?” You may be the first to learn their spouse left them 2 weeks ago.”

Dr. Drummond’s advice is: Don’t always blame the stresses of work. Build your recharge strategy (rest, hobbies, date nights) and make sure you maintain your recharge capabilities.

“Ideally, with a hospitalist-type schedule, when you’re on you’re on and when you’re off you’re off,” he said. “It should be easier to create that boundary for hospitalists than other specialists who chart from home or are on call.

The “off switch” on your doctor programming is called a boundary ritual. Pick some activity you do on the way home from work, saying to yourself ‘with this action, I am coming all the way home.’ It can be as simple as a deep releasing breath as you step out of your car at home. Make sure you take that breath and let it all go before you walk into the house after each shift.”

Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout, refers to this phenomenon as “work-home interference.” On the bright side for hospitalists, he says, is that aspects of HM work schedules may help mitigate burnout; some work can be left at the hospital when shifts end, rather than following physicians into their home lives.

But Dr. West acknowledged that the rigors of the traditional 7-on/7-off schedule come with their own unique burnout challenges for hospitalists as well.

“A hospitalist can say ‘Well, jeez, I’m on nights for the next week, and that means during the day I’m sleeping and recovering,’” Dr. West explained. “Well, how do you maintain a family life for that period of time when you’re basically off-cycle with your family? There are those kinds of stressors. It’s a mixed bag for hospitalists there.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Physician burnout is almost always linked to issues at work. Blame is placed on added duties piled onto a to-do list that barely makes enough time for prolonged patient interaction in the first place. Fault is laid upon the hours and hours per week – or even per day – wasted on cumbersome data entry into bulky electronic health record (EHR) systems.

But Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician and burnout coach/consultant, says burnout should not be viewed as job specific. “To say that burnout is always about work is absolutely an error,” said Dr. Drummond, whose website is www.thehappymd.com. “You can have people flame out spectacularly at work and nothing has changed about work at all. It’s because something’s going on at home that’s made it impossible to recharge on their time off. And, that list of recharge-blocking issues is huge.”

Money problems, marital problems, family problems: Dr. Drummond says any and all of those issues can eliminate the doctor’s ability to recharge at home.

“The strain of your practice continues, but now without the ability to balance your energy with some recovery when you’re away from the hospital, burnout can come on very rapidly,” he said. “So when you see a colleague flaming out at work, one of the questions you must ask is, “How is it going at home?” You may be the first to learn their spouse left them 2 weeks ago.”

Dr. Drummond’s advice is: Don’t always blame the stresses of work. Build your recharge strategy (rest, hobbies, date nights) and make sure you maintain your recharge capabilities.

“Ideally, with a hospitalist-type schedule, when you’re on you’re on and when you’re off you’re off,” he said. “It should be easier to create that boundary for hospitalists than other specialists who chart from home or are on call.

The “off switch” on your doctor programming is called a boundary ritual. Pick some activity you do on the way home from work, saying to yourself ‘with this action, I am coming all the way home.’ It can be as simple as a deep releasing breath as you step out of your car at home. Make sure you take that breath and let it all go before you walk into the house after each shift.”

Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout, refers to this phenomenon as “work-home interference.” On the bright side for hospitalists, he says, is that aspects of HM work schedules may help mitigate burnout; some work can be left at the hospital when shifts end, rather than following physicians into their home lives.

But Dr. West acknowledged that the rigors of the traditional 7-on/7-off schedule come with their own unique burnout challenges for hospitalists as well.

“A hospitalist can say ‘Well, jeez, I’m on nights for the next week, and that means during the day I’m sleeping and recovering,’” Dr. West explained. “Well, how do you maintain a family life for that period of time when you’re basically off-cycle with your family? There are those kinds of stressors. It’s a mixed bag for hospitalists there.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Hot-button issue: physician burnout

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

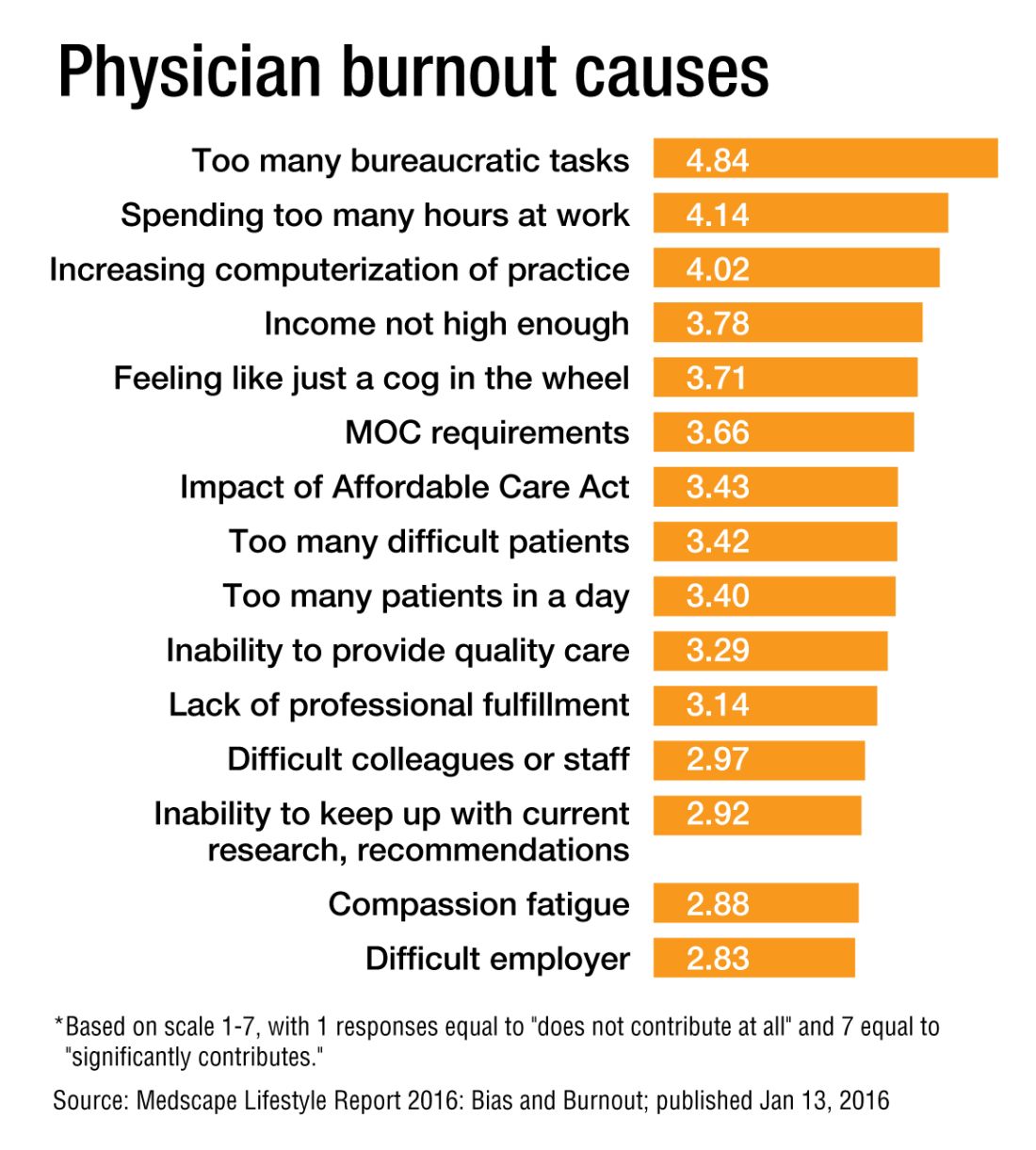

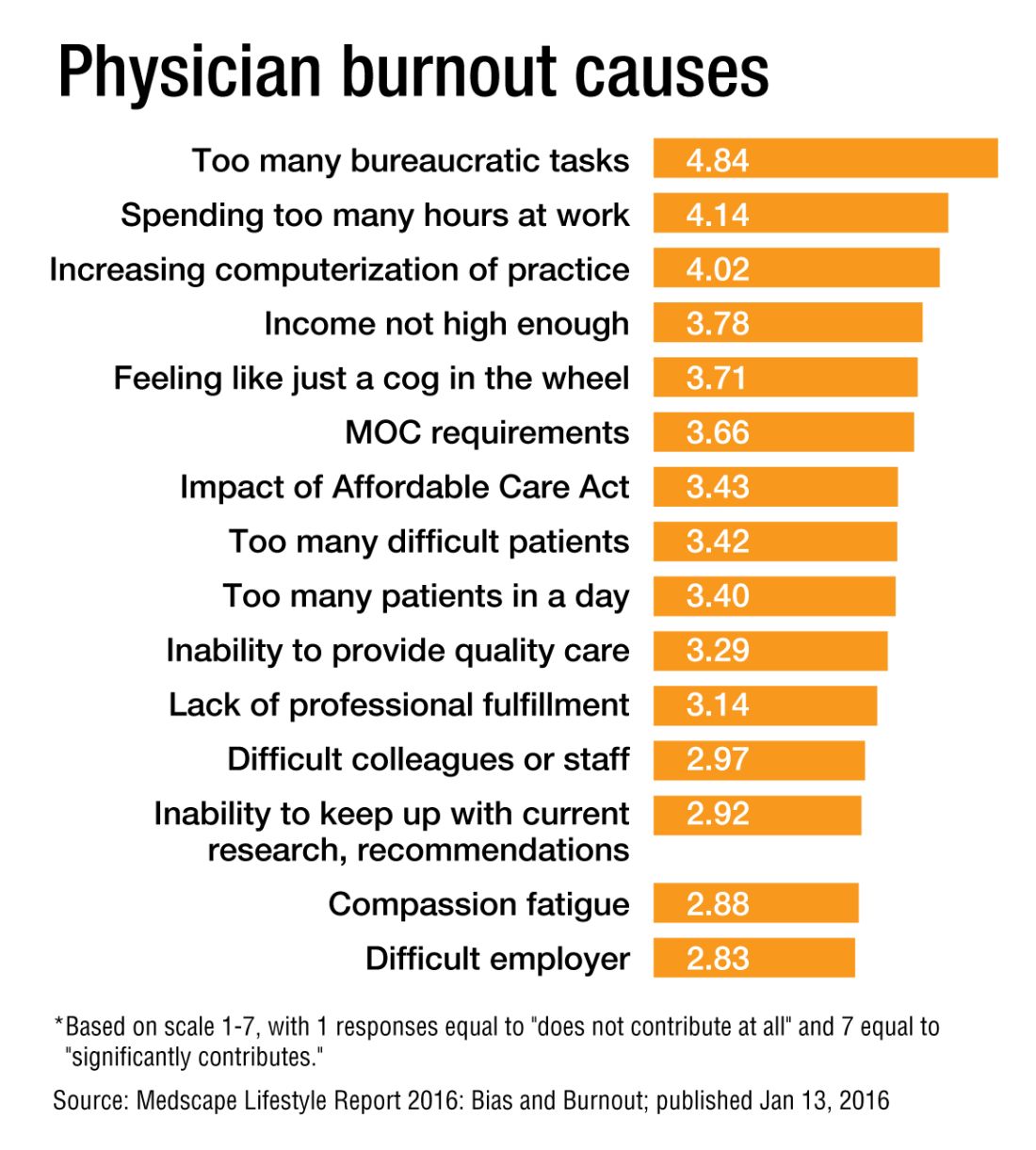

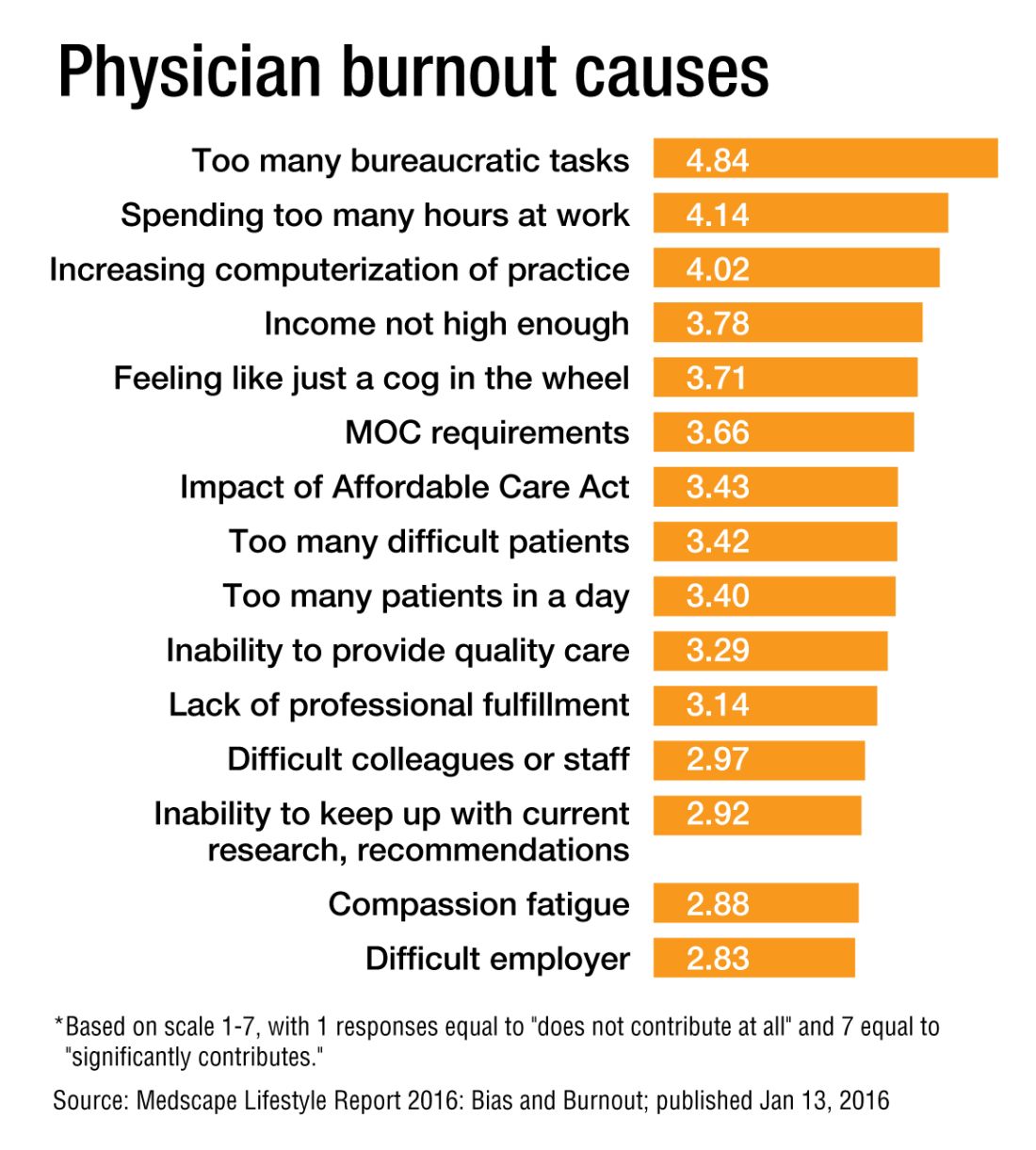

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”