User login

Honor thy parents? Understanding parricide and associated spree killings

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

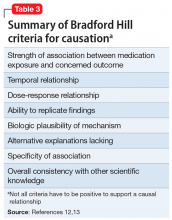

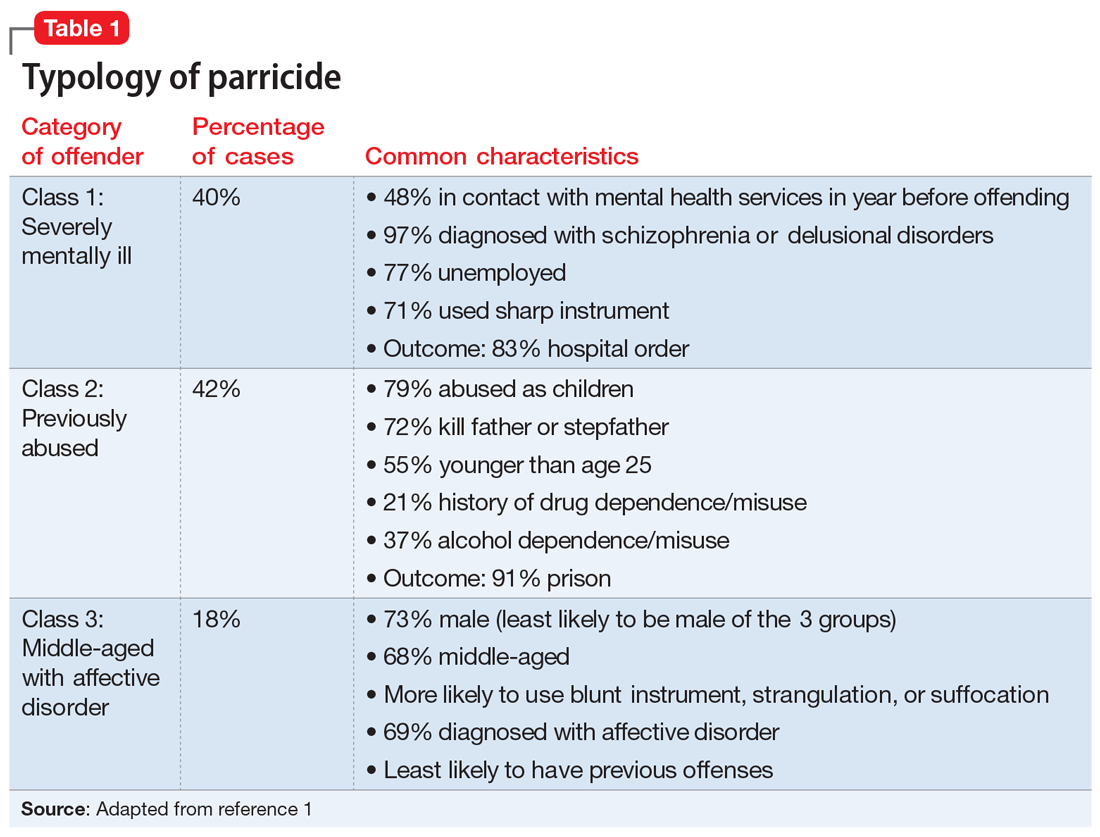

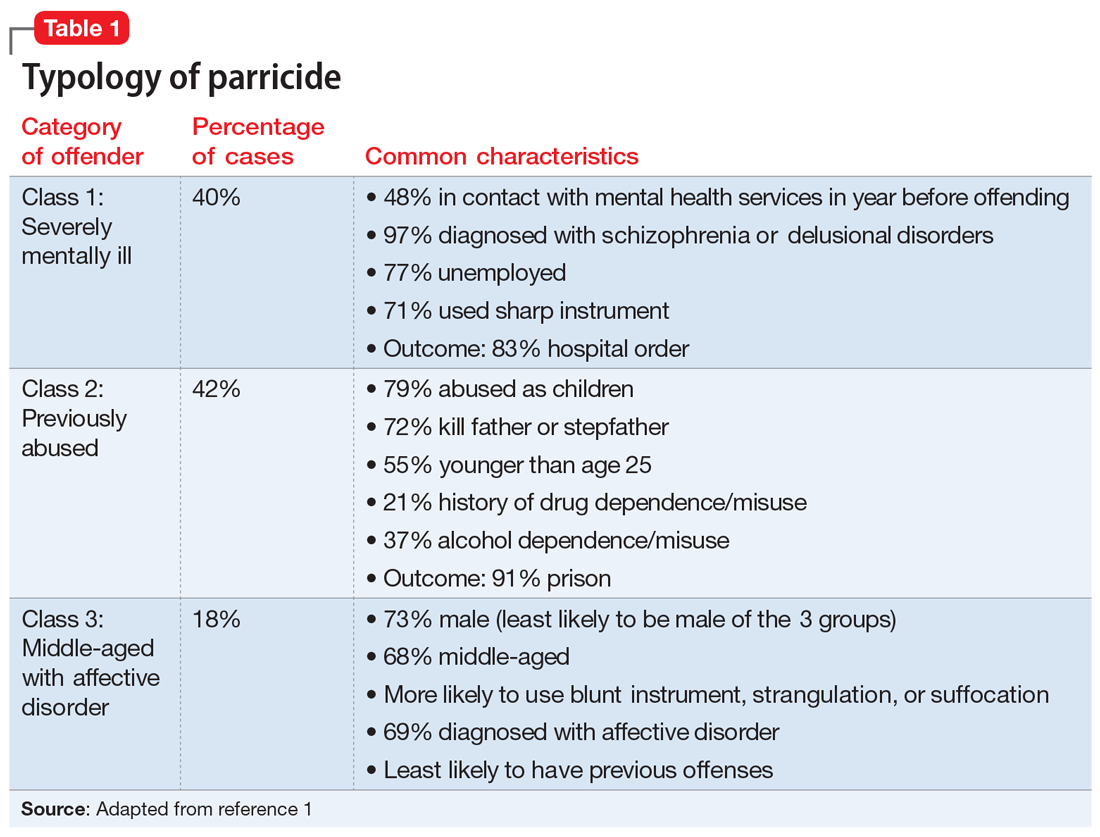

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

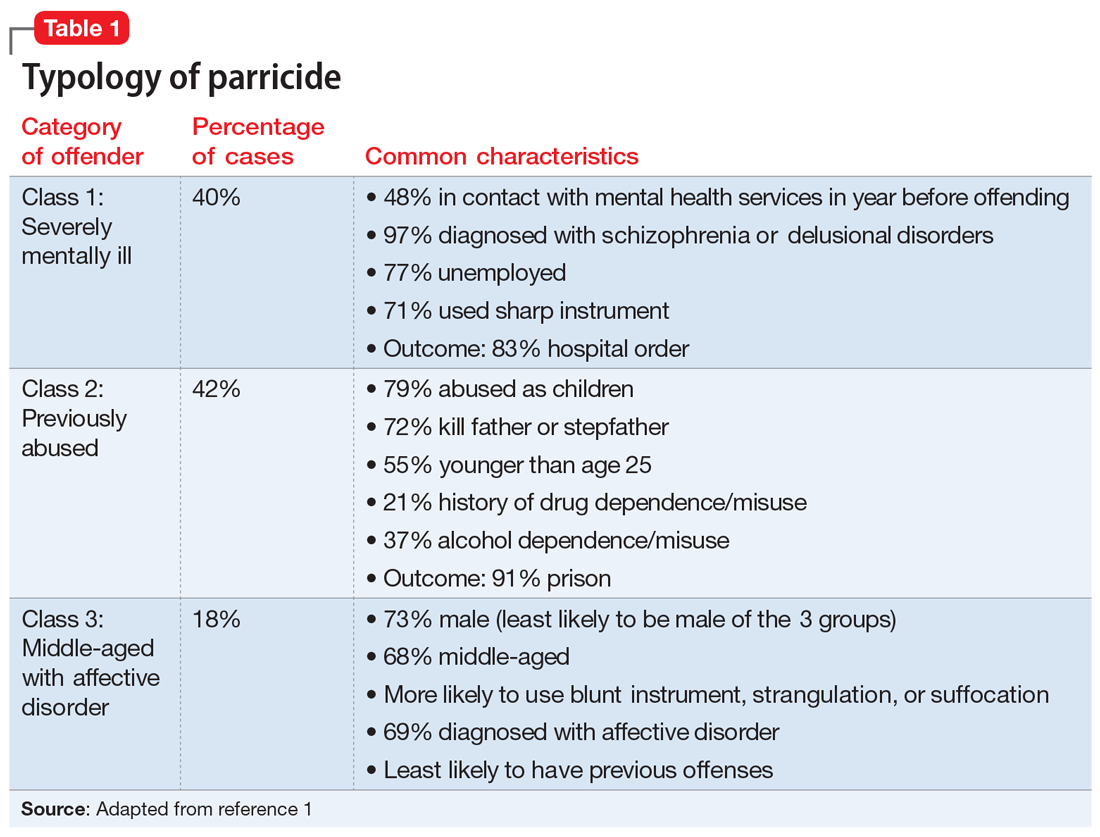

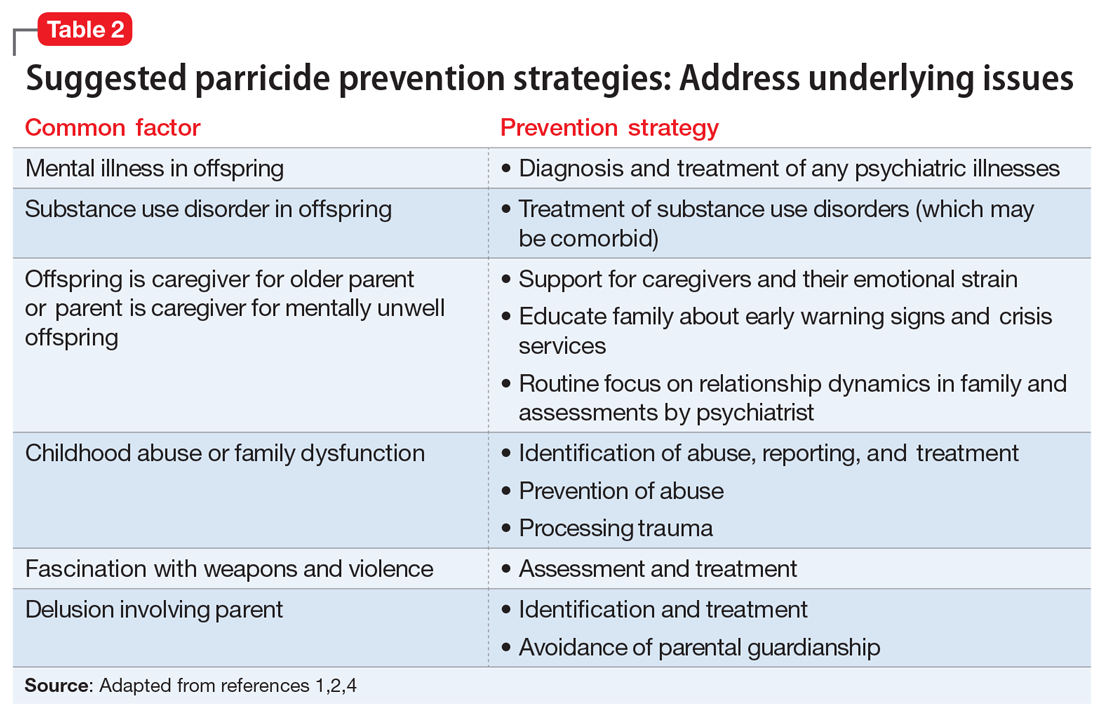

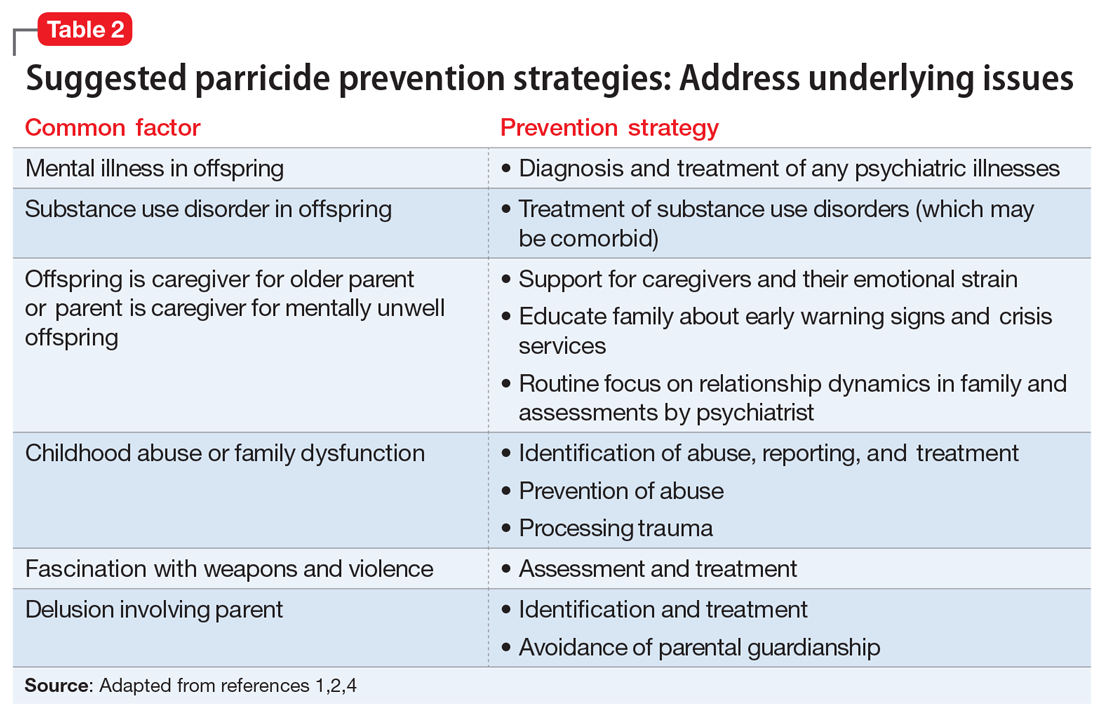

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

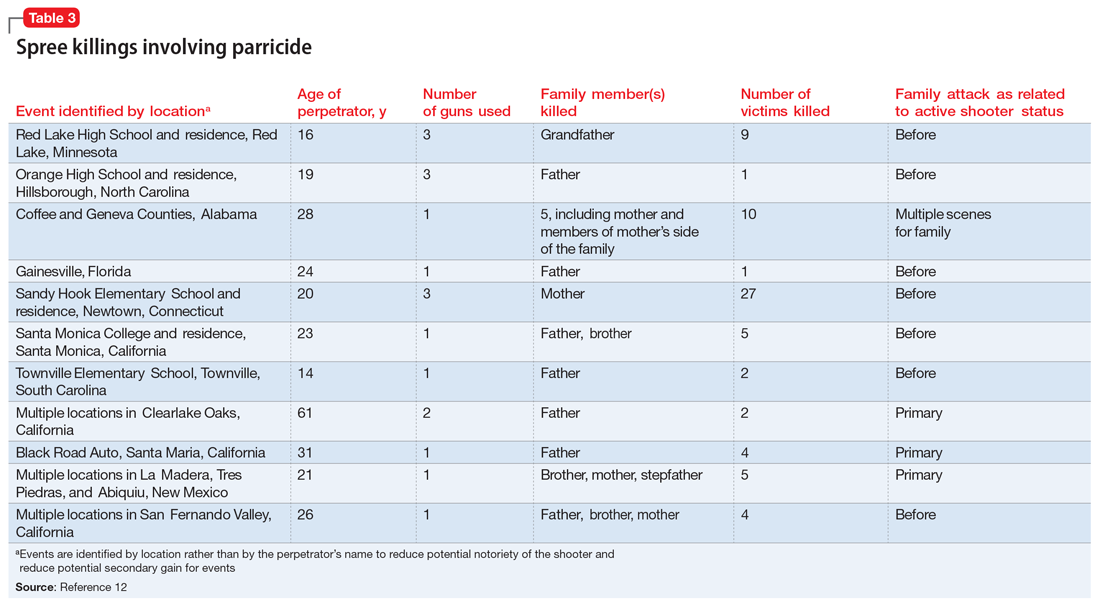

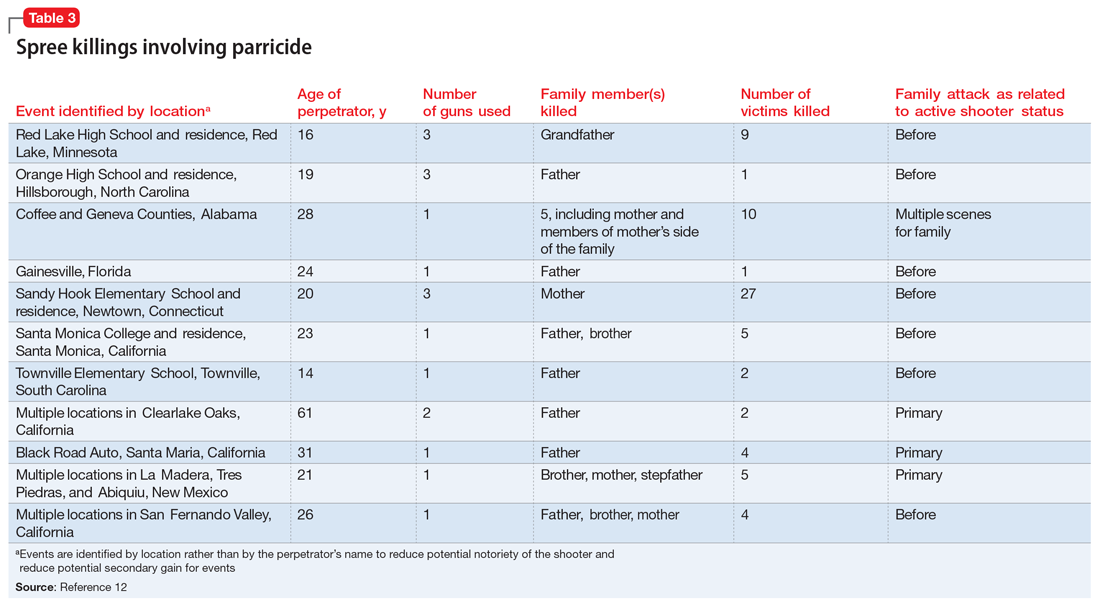

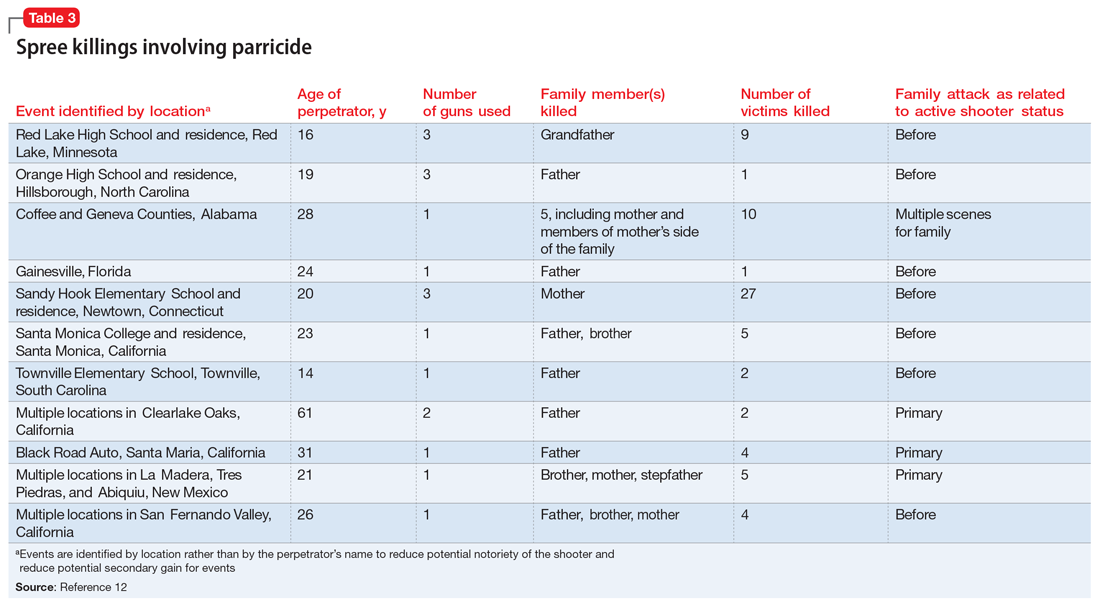

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women

Many physicians have seen advertisements that encourage women who took an antidepressant while they were pregnant and had a negative outcome to contact a law firm. These ads could make patients more reluctant to take prescribed antidepressants, and psychiatrists more hesitant to prescribe necessary medications during pregnancy—which is a disservice to the mother and child.

More recently, several headline-grabbing studies appeared to suggest that there is an increased risk to infants who are exposed to antidepressants prenatally. Unfortunately, many patients do not understand that replication of these studies is often lacking, and methodological and confounding issues abound. All of this makes it difficult for patients and their families to know if they should take an antidepressant during pregnancy, and for psychiatrists to know what to discuss about the risks and benefits of various antidepressants during pregnancy. This article reviews the rationale for treatment of depression in pregnancy; the risks of untreated depression in pregnancy, as well as the potential risks of medication; ethical issues in the treatment of depression in pregnancy; the limitations of available research; and best approaches for practice.

Risks of untreated depression in pregnancy

Pregnant women may have misconceptions about treatment during pregnancy, and psychiatrists often are hesitant to treat pregnant women. However, the risks of untreated depression during pregnancy are even greater than the risks of untreated depression at other points in a woman’s life. In addition to general psychiatric risks seen in depression, pregnant women may experience other issues, such as preeclampsia and liver metabolism changes.1-2 Risks to the fetus related to untreated or partially treated mental health concerns include poor prenatal care related to poor self-care, an increased risk of exposure to illicit substances or alcohol related to “self-medication,” preterm delivery, and low birthweight (Table 13-8). Further risks for an infant of a mother with untreated depression include decreased cognitive performance and poor bonding with poor stress adaptation.5,6 Thus, appropriate treatment of depression is even more important during pregnancy than at other times of life.

Potential risks of treating depression in pregnancy

When prescribing psychotropic medications to a pregnant woman, there are several naturally occurring adverse outcomes to consider. For example, miscarriages, stillbirths, and congenital malformations can occur without explanation in the general population. In addition, also consider the specific health history of the mother and the available research literature regarding the specific psychotropic agent (keeping in mind that there are ethical issues associated with conducting prospective research in pregnant women, such as it being unethical to withhold treatment to pregnant women who are depressed in order to have a control group, and that retrospective research is often confounded by recall bias). Potential risks to be aware of include miscarriage (spontaneous abortion), malformation (teratogenesis, birth defects), preterm delivery, neonatal adaptation syndrome, and behavioral teratogenesis (Table 13-8).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the usual medication treatment of choice for depression, have at times been implicated in adverse pregnancy outcomes, but no strong evidence suggests they increase the miscarriage rate. Overall data are reassuring regarding the risk of malformation associated with SSRI use. Of note, the FDA had switched paroxetine from a Class C drug to a Class D drug after early reports of a potential 1.5% to 2% risk of fetal cardiac malformations compared with a 1% baseline risk in the general population (these FDA pregnancy risk letter categories have since been phased out).9,10 Nevertheless, the absolute risk remains small. Another large study found that there was no substantial increased risk of cardiac malformations attributable to antidepressant use during the first trimester.11

Lessons from a class action suit

Since we last reviewed pregnancy and antidepressants in 2013,8 several class action lawsuits against the manufacturers of psychotropic medications have been heard. Product liability actions brought against manufacturers are different from medical malpractice suits brought against individual physicians, which may result from lack of informed consent, suicide, or homicide.

One of the largest class action suits was against Zoloft (specifically Zoloft and Pfizer, since the brand manufacturer is responsible for the product insert information.)12,13 At the time, sertraline was already commonly prescribed due to the relatively safe reproductive profile.

Continue to: Many of the more than 300...

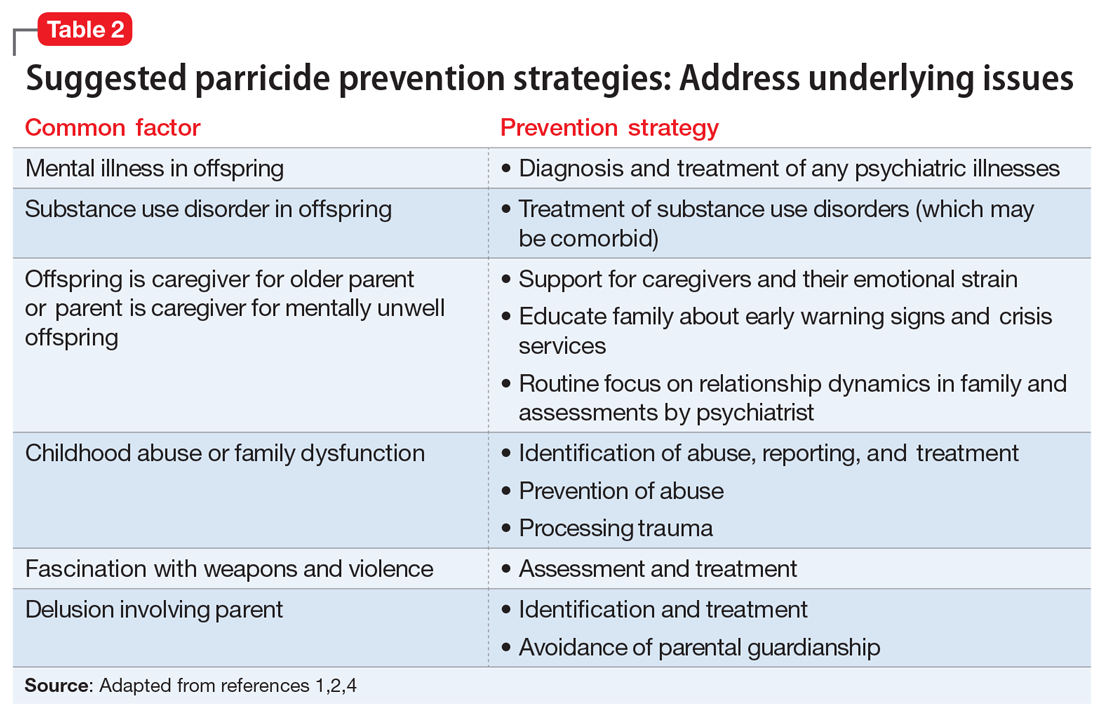

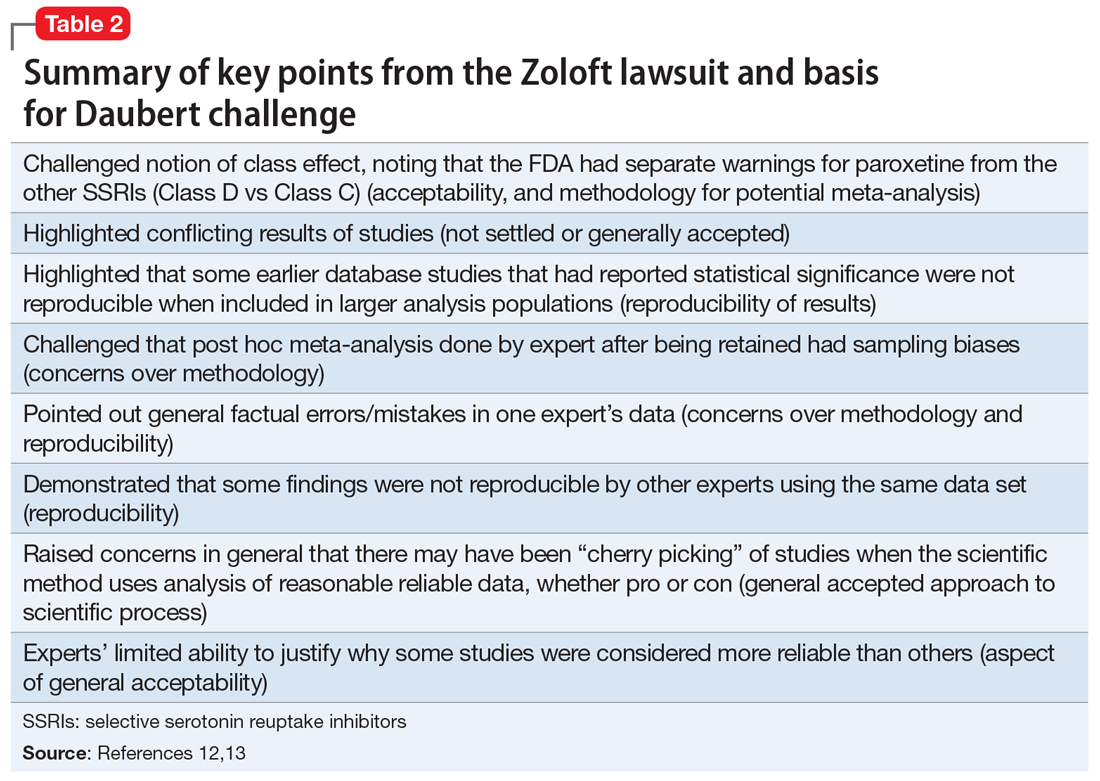

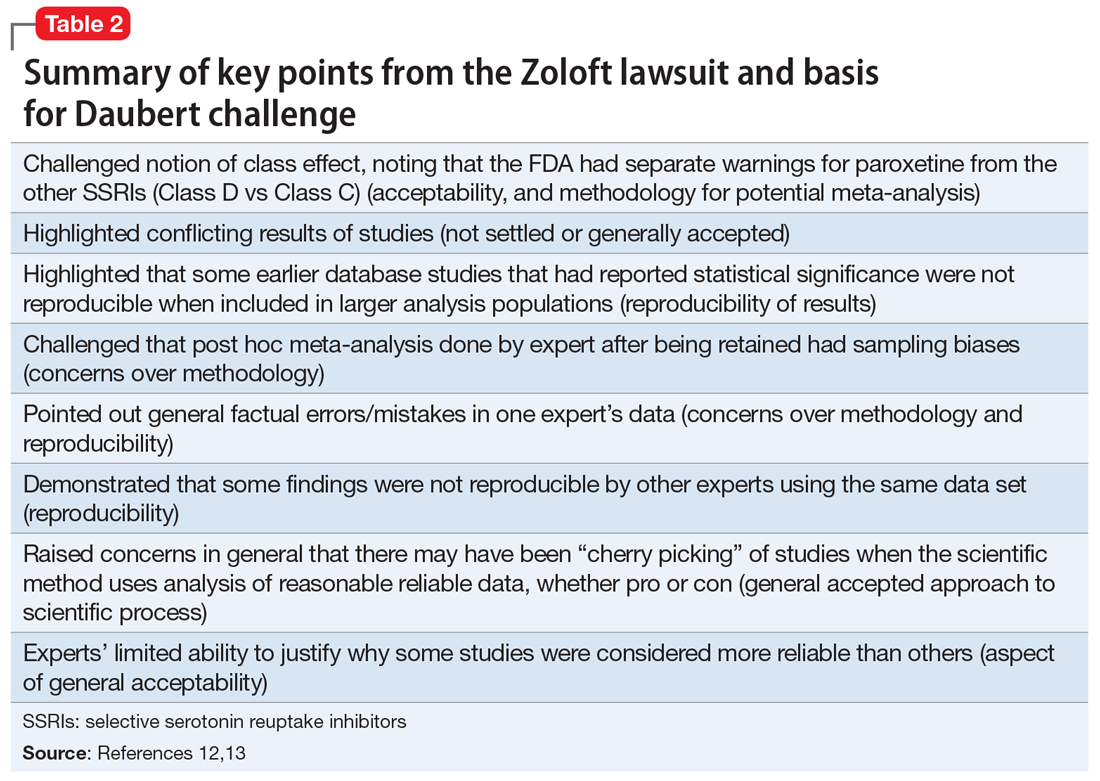

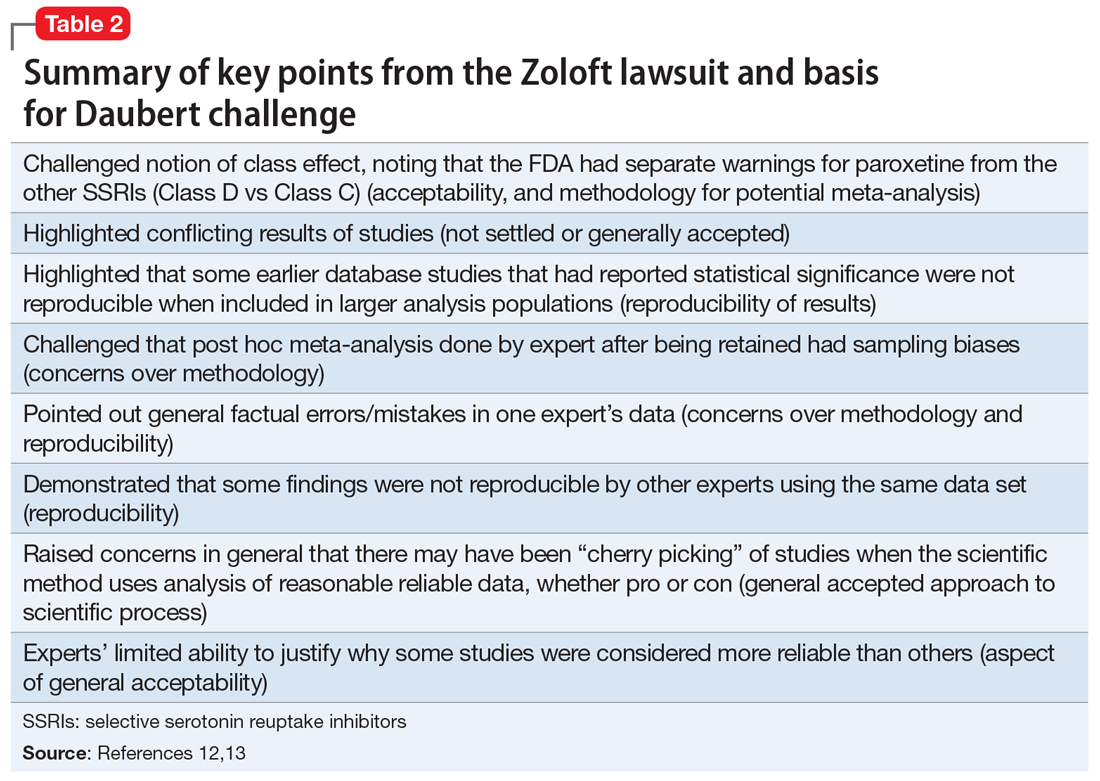

Many of the more than 300 federal claims were united in a multi-district litigation (MDL) suit under the United States District Court of Eastern Pennsylvania (MDL 2342). Pfizer issued Daubert challenges (efforts to exclude the introduction of “junk science” into the courtroom) against the plaintiffs’ experts’ scientific methods and results.12,13 The plaintiffs (those suing Pfizer) had to prove that the medications caused the negative outcome, not that they were merely temporally associated. Subsequently, 2 plaintiff experts—a PharmD and a biostatistician—were removed. Pfizer successfully challenged the methodological soundness of the plaintiffs’ experts’ testimony (Table 212,13), and the case was dismissed. In general, the courts identified the Bradford Hill criteria as often being important (though not definitive) methodology for determining causation (Table 312,13).

A concept raised in prior psychotropic lawsuits was the “learned intermediary doctrine,” in which pharmaceutical companies stated that once a risk is known, it is the responsibility of the prescribing physician to assess risks vs benefits and inform the patient.8 Many aspects of the larger class action lawsuits related to failure of the company to do adequate research to identify risks and appropriately inform the public and the medical community of these risks.14

Challenges in interpreting the literature

Some of the difficulties in interpreting the literature on the association of antidepressants and birth defects can be seen in a 2020 study by Anderson et al.15 This study was published in JAMA Psychiatry, received widespread coverage in the media, and was discussed on the CDC’s website.16 Anderson et al15 compared a large cohort of 30,630 infants with birth defects from the multicenter case-control National Birth Defects Prevention Study with 11,478 randomly selected controls with no defects. Three primary study groups were women whose pregnancies resulted in:

- birth defects with no antidepressant exposure (n = 28,719)

- birth defects with exposure to an antidepressant (n = 1,911)

- no birth defect control group (n = 10,886 no antidepressant exposure, n = 592 antidepressant exposure).

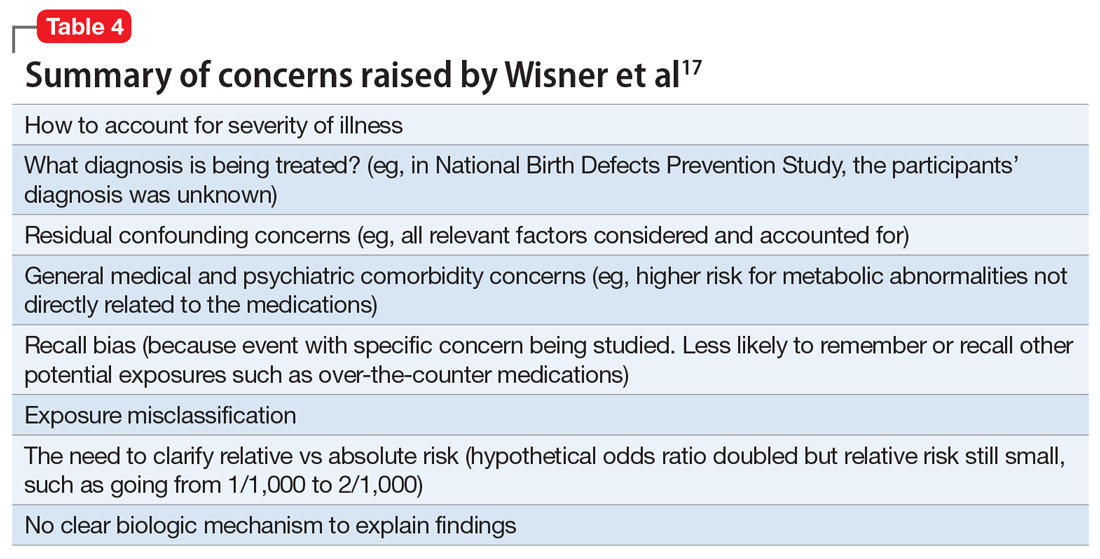

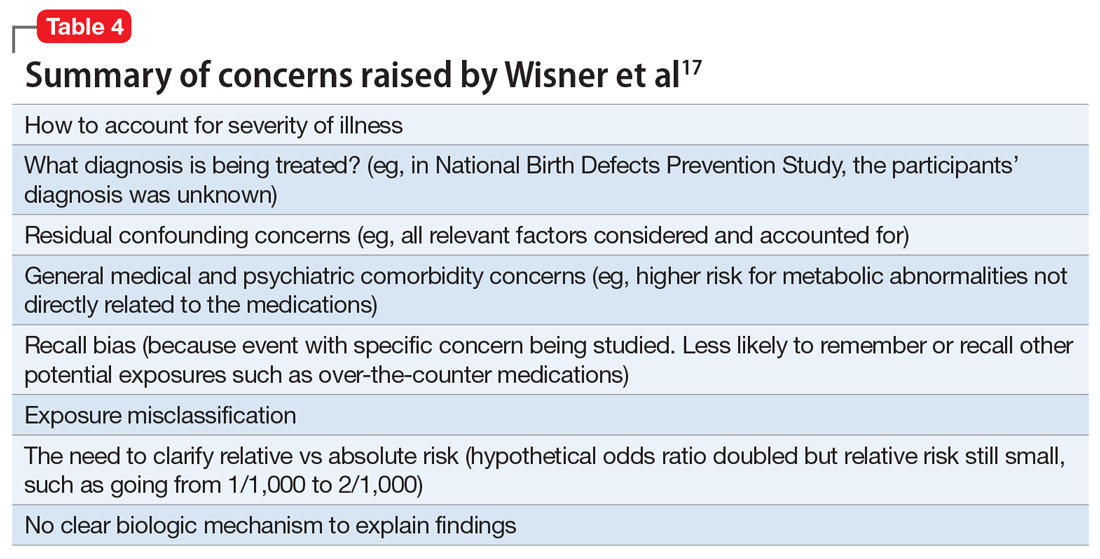

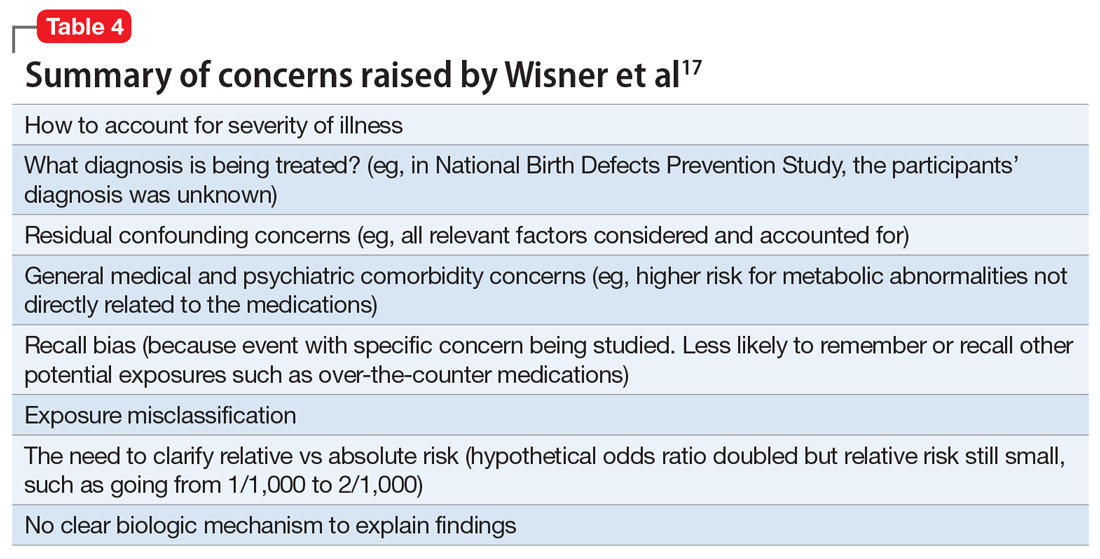

This study reported there were “some associations between maternal antidepressant use and specific birth defects” and “Venlafaxine was associated with more birth defects than other antidepressants, which needs confirmation.”15 However, in an accompanying editorial, Wisner et al17 discussed potential problems and limitations with this study and research of this nature in general (Table 417). In addition, Anderson et al15 used certain “controversial” statistical practices.18 For example, “[T]o align with American Statistical Association guidelines to consider effect sizes when interpreting results instead of statistical significance, we noted associations as meaningfully elevated if [adjusted odds ratios] were 2.0 or greater and lower confidence interval bounds were 0.8 or greater.”15

Those who read only abstracts or news stories may believe this study of >40,000 participants included a large number of women who were receiving venlafaxine. However, the number of pregnant women who were prescribed venlafaxine was actually very small—112 who took venlafaxine experienced a birth defect. In addition, the authors noted “Venlafaxine was associated with many of the same defects across the samples (data not shown).”15 As discussed above, historically one of the areas the courts have considered was whether or not appropriate methodology was applied, and whether the results could be replicated with the data provided.

Continue to: Further, new studies...

Further, new studies need to be considered in context of the literature as a whole and collective clinical experience. A recent systematic review found that among 3,186 infants exposed to venlafaxine during the first trimester, there were 107 major malformations.19 This indicated a relative risk estimate of 1.12, with a 95% CI of 0.92 to 1.35. The authors concluded that venlafaxine exposure in the first trimester was not associated with an increased risk of malformations.

Expectant parents may come across a headline that implies a specific antidepressant causes problems, but have not read the study or know how to interpret it. Often it is best for a physician to find out what the basis of the concern is, and if possible, review the study with the patient to make sure it is in the right context, and if it applies to the individual patient’s situation.

Consider the ethical issues

In addition to preventive ethics, other critical ethical issues in pregnancy include omission bias, beneficence, and autonomy.4,20-24 Omission bias occurs when physicians are more concerned about acts of commission (in which treatment leads to a negative outcome) than they are about acts of omission, which involve not treating the patient’s illness. To address this, it is important to discuss with the patient both the risks of treating and the risks of not treating maternal depression, so that the mother can make the best decision for her own specific set of circumstances.

Regarding beneficence (promoting the patient’s best interest), consider both the mother’s and the infant’s best interest, which usually are quite closely related. Women may feel guilty about taking a medication that they perceive is harmful for the fetus but good for their own mental health. Physicians can help with this by providing education about the benefits of treating depression for the fetus’ benefit as well. The fetus is completely dependent on the environment that the mother places them in, not merely the medication effects (eg, psychologic/physiologic stress effects, poor diet, lack of exercise, risk of “self-medication”).

Regarding autonomy (a woman’s own decision-making), Coverdale et al21 discussed strategies that can enhance a pregnant patient’s autonomy—including discussing treatment options and counselling about the effects of depression itself in pregnancy, as well as considering the effects of depression on the process of decision-making. For example, a woman with depression may see the world through a negative lens or may have difficulty concentrating. Patients may also require education about the concept of relative risk in comparison to absolute risk—especially in light of attention-grabbing headlines.

Continue to: Finally, as part of...

Finally, as part of preventative ethics, anticipate the ethical dilemmas before the common situation of pregnancy. Almost one-half of pregnancies are unplanned.25 Many women thus expose their fetus to medication during the critical early period of organogenesis, before noticing they were pregnant. Therefore, even if a patient of childbearing age insists that she is not sexually active, the prudent psychiatrist should still begin discussions about medications in pregnancy.

An outline of best practices

Best practice includes preventive ethics, and when treating any woman of childbearing age, psychiatrists should consider prescribing medications that are known to be relatively safe in pregnancy rather than risky in pregnancy. Therefore, any psychiatrist whose practice includes women of childbearing age should have a working knowledge of which agents are relatively safe in pregnancy. After a woman is pregnant, careful decision-making about medication should continue. Consult with reproductive psychiatry colleagues where necessary.

A patient with depression would usually merit closer follow-up during the pregnancy. In some cases, psychotherapy alone can be effective in depression. However, approximately 6% to 13% of women are prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy, and this has been increasing.26 Women who discontinue their antidepressant while pregnant are more likely to relapse than those who continue their medication,27 thus exposing their fetus to negative effects of depression as well as medication (prior to discontinuation).

When possible, monotherapy (one agent) in the lowest effective dose is often the judicious approach to treatment. For a patient prescribed pre-existing polypharmacy at time of pregnancy, a risk-benefit analysis of which medications should remain, which should be stopped, and a plan for taper, if needed, should be discussed and documented. Using too little of an antidepressant dose would expose the fetus to both depression and medication, whereas using a maximum dose when not needed would expose the fetus to more medication than is necessary to treat the mother’s symptoms. This discussion with the mother (and her partner, if available) should be documented in the chart. The mother should understand both the risk of untreated illness and the potential risks of medications, as well as the benefits of medications and alternatives. It is important for the mother to realize that there is no risk-free option, and that malformations can occur in the general population as well as in individuals with untreated depression, separate from any medication exposure. In fact, most malformations do not have a known cause, and overall approximately 3% of pregnancies result in a birth defect.28

If possible, discuss the treatment plan with the patient’s obstetrician, or ask the mother to discuss the plan with her obstetrician, so that everyone is on the same page. This discussion can help attenuate patient anxiety that results from hearing different things from different clinicians. Communication with other treating professionals (eg, OB/GYNs, pediatricians) can be beneficial and reduce liability if multiple physicians have agreed on a treatment plan—even if there is a negative outcome. With malpractice, a clinician is not necessarily at fault for a bad outcome or adverse effect, but is at fault for lack of informed consent or negligence (deviation from standard of care), which is harder for an attorney to demonstrate if there is deliberation, communication, and a plan that multiple doctors agree upon.

Continue to: Be aware that informed consent...

Be aware that informed consent is an ongoing process, and a woman may need to be reminded or informed of potential risks at varying stages of her life (eg, when starting a new relationship, getting married, etc.). Documentation can include that the clinician has discussed the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternatives of various medications, and a description of any patient-specific or medication-specific issues. In addition to verbal discussions, giving patients printed information can be helpful, as can directing them to appropriate websites (see Related Resources). Some physicians require patients to sign a form to indicate that they are aware of known risks.

Similar to being proactive before your patient becomes pregnant, think proactively regarding the postpartum period. Is your patient planning to breastfeed? Is the medication compatible with breastfeeding, or is bottle feeding the best option considering the mother’s specific circumstances? For example, developing severe symptoms, experiencing insomnia, needing to take a contraindicated medication, or having a vulnerable infant might sway a mother towards not breastfeeding. The expectant mother (and her partner, where possible) should be educated about postpartum risks and the importance of sleep in preventing postpartum depression.

Bottom Line

Concerns about being sued should not prevent appropriate care of depression in a woman who is pregnant. Discuss with your patient both the risk of untreated mental illness and the risk of medications to ensure she understands that avoiding antidepressants does not guarantee a safe or healthy pregnancy.

Related Resources

- MotherToBaby. www.mothertobaby.org/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treating for two: medicine and pregnancy. www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/meds/treatingfortwo/index.html

- MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. Reproductive psychiatry resource and information center. www.womensmentalhealth.org/

Drug Brand Names

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Palmsten K, Setoguchi S, Margulis AV, et al. Elevated risk of preeclampsia in pregnant women with depression: depression or antidepressants? Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):988-997.

2. Sit DK, Perel JM, Helsel JC, et al. Changes in antidepressant metabolism and dosing across pregnancy and early postpartum. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):652-658.

3. Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1012-1024.

4. Friedman SH. The ethics of treating depression in pregnancy. J Prim Health Care. 2015;7(1):81-83.

5. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Postpartum depression: an update. Women’s Health. 2009;5(3):287-295.

6. Liu Y, Kaaya S, Chai J, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2017;47(4):680-689.

7. Wisner KL, Sit DK, Hanusa BH, et al. Major depression and antidepressant treatment: impact on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2009; 166(5):557-566.

8. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Antidepressant use during pregnancy: How to avoid clinical and legal pitfalls. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):21-25.

9. Bar-Oz B, Einarson T, Einarson A, et al. Paroxetine and congenital malformations: meta-analysis and consideration of potential confounding factors. Clin Ther. 2007;29(5):918-926.

10. Einarson A, Pistelli A, DeSantis M, et al. Evaluation of the risk of congenital cardiovascular defects associated with use of paroxetine during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):749-752.

11. Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(25):2397-2407.

12. In re: Zoloft (sertraline hydrochloride) products liability litigation. MDL No. 2342. No. 12-md-2342. United States District Court, E.D. Pennsylvania. June 27, 2014.

13. In re: Zoloft (sertraline hydrocloride) products liability litigation. MDL No. 2342. United States District Court, E.D. Pennsylvania. December 2, 2015.

14. Kirsch N, Pacheco LD, Hossain A, et al. Medicolegal review: perinatal Effexor lawsuits and legal strategies adverse to prescribing obstetric providers. AJP Rep. 2019;9(1):e88-e91.

15. Anderson KN, Lind JN, Simeone RM, et al. Maternal use of specific antidepressant medications during early pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1246-1255.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of the antidepressant venlafaxine during early pregnancy may be linked to specific birth defects. Published October 28, 2020. Accessed October 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/features/venlafaxine-during-pregnancy.html

17. Wisner KL, Oberlander TF, Huybrechts KF. The association between antidepressant exposure and birth defects--are we there yet? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(12):1215-1216.

18. Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. American Statistician. 2016;70(2):129-133.

19. Lassen D, Ennis ZN, Damkier P. First-trimester pregnancy exposure to venlafaxine or duloxetine and risk of major congenital malformations: a systematic review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;118(1):32-36.

20. Miller LJ. Ethical issues in perinatal mental health. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(2):259-270.

21. Coverdale JH, McCullough JB, Chervenak FA. Enhancing decision-making by depressed pregnant patients. J Perinat Med. 2002;30(4):349-351.

22. Coverdale JH, McCullough LB, Chervenak FA, et al. Clinical implications of respect for autonomy in the psychiatric treatment of pregnant patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:209-212.

23. Coverdale JH, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, et al. Ethically justified clinically comprehensive guidelines for the management of the depressed pregnant patient. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(1):169-173.

24. Wisner KL, Zarin DA, Holmboe ES, et al. Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):1933-1940.

25. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478-485.

26. Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, et al. Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):544.e1-5.

27. Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295(5):499-507.

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update on overall prevalence of major birth defects--Atlanta, Georgia, 1978-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(1):1-5.

Many physicians have seen advertisements that encourage women who took an antidepressant while they were pregnant and had a negative outcome to contact a law firm. These ads could make patients more reluctant to take prescribed antidepressants, and psychiatrists more hesitant to prescribe necessary medications during pregnancy—which is a disservice to the mother and child.

More recently, several headline-grabbing studies appeared to suggest that there is an increased risk to infants who are exposed to antidepressants prenatally. Unfortunately, many patients do not understand that replication of these studies is often lacking, and methodological and confounding issues abound. All of this makes it difficult for patients and their families to know if they should take an antidepressant during pregnancy, and for psychiatrists to know what to discuss about the risks and benefits of various antidepressants during pregnancy. This article reviews the rationale for treatment of depression in pregnancy; the risks of untreated depression in pregnancy, as well as the potential risks of medication; ethical issues in the treatment of depression in pregnancy; the limitations of available research; and best approaches for practice.

Risks of untreated depression in pregnancy

Pregnant women may have misconceptions about treatment during pregnancy, and psychiatrists often are hesitant to treat pregnant women. However, the risks of untreated depression during pregnancy are even greater than the risks of untreated depression at other points in a woman’s life. In addition to general psychiatric risks seen in depression, pregnant women may experience other issues, such as preeclampsia and liver metabolism changes.1-2 Risks to the fetus related to untreated or partially treated mental health concerns include poor prenatal care related to poor self-care, an increased risk of exposure to illicit substances or alcohol related to “self-medication,” preterm delivery, and low birthweight (Table 13-8). Further risks for an infant of a mother with untreated depression include decreased cognitive performance and poor bonding with poor stress adaptation.5,6 Thus, appropriate treatment of depression is even more important during pregnancy than at other times of life.

Potential risks of treating depression in pregnancy

When prescribing psychotropic medications to a pregnant woman, there are several naturally occurring adverse outcomes to consider. For example, miscarriages, stillbirths, and congenital malformations can occur without explanation in the general population. In addition, also consider the specific health history of the mother and the available research literature regarding the specific psychotropic agent (keeping in mind that there are ethical issues associated with conducting prospective research in pregnant women, such as it being unethical to withhold treatment to pregnant women who are depressed in order to have a control group, and that retrospective research is often confounded by recall bias). Potential risks to be aware of include miscarriage (spontaneous abortion), malformation (teratogenesis, birth defects), preterm delivery, neonatal adaptation syndrome, and behavioral teratogenesis (Table 13-8).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the usual medication treatment of choice for depression, have at times been implicated in adverse pregnancy outcomes, but no strong evidence suggests they increase the miscarriage rate. Overall data are reassuring regarding the risk of malformation associated with SSRI use. Of note, the FDA had switched paroxetine from a Class C drug to a Class D drug after early reports of a potential 1.5% to 2% risk of fetal cardiac malformations compared with a 1% baseline risk in the general population (these FDA pregnancy risk letter categories have since been phased out).9,10 Nevertheless, the absolute risk remains small. Another large study found that there was no substantial increased risk of cardiac malformations attributable to antidepressant use during the first trimester.11

Lessons from a class action suit

Since we last reviewed pregnancy and antidepressants in 2013,8 several class action lawsuits against the manufacturers of psychotropic medications have been heard. Product liability actions brought against manufacturers are different from medical malpractice suits brought against individual physicians, which may result from lack of informed consent, suicide, or homicide.

One of the largest class action suits was against Zoloft (specifically Zoloft and Pfizer, since the brand manufacturer is responsible for the product insert information.)12,13 At the time, sertraline was already commonly prescribed due to the relatively safe reproductive profile.

Continue to: Many of the more than 300...

Many of the more than 300 federal claims were united in a multi-district litigation (MDL) suit under the United States District Court of Eastern Pennsylvania (MDL 2342). Pfizer issued Daubert challenges (efforts to exclude the introduction of “junk science” into the courtroom) against the plaintiffs’ experts’ scientific methods and results.12,13 The plaintiffs (those suing Pfizer) had to prove that the medications caused the negative outcome, not that they were merely temporally associated. Subsequently, 2 plaintiff experts—a PharmD and a biostatistician—were removed. Pfizer successfully challenged the methodological soundness of the plaintiffs’ experts’ testimony (Table 212,13), and the case was dismissed. In general, the courts identified the Bradford Hill criteria as often being important (though not definitive) methodology for determining causation (Table 312,13).

A concept raised in prior psychotropic lawsuits was the “learned intermediary doctrine,” in which pharmaceutical companies stated that once a risk is known, it is the responsibility of the prescribing physician to assess risks vs benefits and inform the patient.8 Many aspects of the larger class action lawsuits related to failure of the company to do adequate research to identify risks and appropriately inform the public and the medical community of these risks.14

Challenges in interpreting the literature

Some of the difficulties in interpreting the literature on the association of antidepressants and birth defects can be seen in a 2020 study by Anderson et al.15 This study was published in JAMA Psychiatry, received widespread coverage in the media, and was discussed on the CDC’s website.16 Anderson et al15 compared a large cohort of 30,630 infants with birth defects from the multicenter case-control National Birth Defects Prevention Study with 11,478 randomly selected controls with no defects. Three primary study groups were women whose pregnancies resulted in:

- birth defects with no antidepressant exposure (n = 28,719)

- birth defects with exposure to an antidepressant (n = 1,911)

- no birth defect control group (n = 10,886 no antidepressant exposure, n = 592 antidepressant exposure).

This study reported there were “some associations between maternal antidepressant use and specific birth defects” and “Venlafaxine was associated with more birth defects than other antidepressants, which needs confirmation.”15 However, in an accompanying editorial, Wisner et al17 discussed potential problems and limitations with this study and research of this nature in general (Table 417). In addition, Anderson et al15 used certain “controversial” statistical practices.18 For example, “[T]o align with American Statistical Association guidelines to consider effect sizes when interpreting results instead of statistical significance, we noted associations as meaningfully elevated if [adjusted odds ratios] were 2.0 or greater and lower confidence interval bounds were 0.8 or greater.”15

Those who read only abstracts or news stories may believe this study of >40,000 participants included a large number of women who were receiving venlafaxine. However, the number of pregnant women who were prescribed venlafaxine was actually very small—112 who took venlafaxine experienced a birth defect. In addition, the authors noted “Venlafaxine was associated with many of the same defects across the samples (data not shown).”15 As discussed above, historically one of the areas the courts have considered was whether or not appropriate methodology was applied, and whether the results could be replicated with the data provided.

Continue to: Further, new studies...

Further, new studies need to be considered in context of the literature as a whole and collective clinical experience. A recent systematic review found that among 3,186 infants exposed to venlafaxine during the first trimester, there were 107 major malformations.19 This indicated a relative risk estimate of 1.12, with a 95% CI of 0.92 to 1.35. The authors concluded that venlafaxine exposure in the first trimester was not associated with an increased risk of malformations.

Expectant parents may come across a headline that implies a specific antidepressant causes problems, but have not read the study or know how to interpret it. Often it is best for a physician to find out what the basis of the concern is, and if possible, review the study with the patient to make sure it is in the right context, and if it applies to the individual patient’s situation.

Consider the ethical issues

In addition to preventive ethics, other critical ethical issues in pregnancy include omission bias, beneficence, and autonomy.4,20-24 Omission bias occurs when physicians are more concerned about acts of commission (in which treatment leads to a negative outcome) than they are about acts of omission, which involve not treating the patient’s illness. To address this, it is important to discuss with the patient both the risks of treating and the risks of not treating maternal depression, so that the mother can make the best decision for her own specific set of circumstances.

Regarding beneficence (promoting the patient’s best interest), consider both the mother’s and the infant’s best interest, which usually are quite closely related. Women may feel guilty about taking a medication that they perceive is harmful for the fetus but good for their own mental health. Physicians can help with this by providing education about the benefits of treating depression for the fetus’ benefit as well. The fetus is completely dependent on the environment that the mother places them in, not merely the medication effects (eg, psychologic/physiologic stress effects, poor diet, lack of exercise, risk of “self-medication”).

Regarding autonomy (a woman’s own decision-making), Coverdale et al21 discussed strategies that can enhance a pregnant patient’s autonomy—including discussing treatment options and counselling about the effects of depression itself in pregnancy, as well as considering the effects of depression on the process of decision-making. For example, a woman with depression may see the world through a negative lens or may have difficulty concentrating. Patients may also require education about the concept of relative risk in comparison to absolute risk—especially in light of attention-grabbing headlines.

Continue to: Finally, as part of...

Finally, as part of preventative ethics, anticipate the ethical dilemmas before the common situation of pregnancy. Almost one-half of pregnancies are unplanned.25 Many women thus expose their fetus to medication during the critical early period of organogenesis, before noticing they were pregnant. Therefore, even if a patient of childbearing age insists that she is not sexually active, the prudent psychiatrist should still begin discussions about medications in pregnancy.

An outline of best practices

Best practice includes preventive ethics, and when treating any woman of childbearing age, psychiatrists should consider prescribing medications that are known to be relatively safe in pregnancy rather than risky in pregnancy. Therefore, any psychiatrist whose practice includes women of childbearing age should have a working knowledge of which agents are relatively safe in pregnancy. After a woman is pregnant, careful decision-making about medication should continue. Consult with reproductive psychiatry colleagues where necessary.

A patient with depression would usually merit closer follow-up during the pregnancy. In some cases, psychotherapy alone can be effective in depression. However, approximately 6% to 13% of women are prescribed antidepressants during pregnancy, and this has been increasing.26 Women who discontinue their antidepressant while pregnant are more likely to relapse than those who continue their medication,27 thus exposing their fetus to negative effects of depression as well as medication (prior to discontinuation).