User login

Antireflux surgery in the proton pump inhibitor era

For most patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is the first choice for treatment.1 But some patients have symptoms that persist despite PPI therapy, some desire surgery despite successful PPI therapy, and some have persistent extraesophageal symptoms or other complications of reflux. For these patients, surgery is an option.2

In this article, we review the management of GERD and clarify the indications for antireflux surgery based on evidence of safety and efficacy.

GERD DEFINED: SYMPTOMS OR COMPLICATIONS

Defining the role of antireflux surgery is difficult, given the variety of presentations and the absence of a gold standard for diagnosing GERD. Most adults experience several episodes of physiologic reflux daily without symptoms.3 But a broad array of symptoms have been attributed to GERD, including chest pain, cough, and sore throat, and some conditions caused by acid reflux (eg, Barrett esophagus) can be asymptomatic.4,5

HEARTBURN ISN’T ALWAYS GERD

Typical GERD presents with the classic symptoms of pyrosis (heartburn) or acid regurgitation, or both.

Although these symptoms are often thought to be specific for GERD, other causes of esophageal injury— eg, eosinophilic esophagitis, infection (Candida, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus), pill-induced esophagitis, or radiation therapy—can produce similar symptoms. Other causes, including coronary artery disease, biliary colic, foregut malignancy, or peptic ulcer disease, should also be considered in patients with supposedly typical GERD. Life-threatening mimics of GERD, such as unstable angina, should be excluded if they are likely, before proceeding with evaluating for possible GERD. Therefore, the initial history and examination should focus on appropriate diagnosis, with careful delineation of symptom quality.

Alarm features for advanced pathology6–8 include involuntary weight loss, dysphagia, vomiting, evidence of gastrointestinal blood loss, anemia, chest pain, and an epigastric mass.7 Admittedly, these features are only mediocre for detecting or excluding gastric or esophageal cancer, with a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity 66%.9 Nevertheless, they should prompt an endoscopic examination. In patients who have alarm features but have not yet been treated for GERD, upper endoscopy can identify an abnormality in about 60% of patients.10–12

PPIs HAVE REPLACED ANTACIDS AND HISTAMINE-2 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

When the symptoms suggest GERD and no alarm features are present, an initial trial of the following lifestyle changes is reasonable:

- Avoiding acidic or refluxogenic foods (coffee, alcohol, chocolate, peppermint, fatty foods, citrus foods)

- Avoiding certain medications (anticholinergics, estrogens, calcium-channel blockers, nitroglycerine, benzodiazepines)

- Losing weight

- Quitting smoking

- Raising the head of the bed

- Staying upright for 2 to 3 hours after meals.

For someone with mild symptoms, these changes pose minimal risk. Unfortunately, they are unlikely to provide adequate symptom control for most patients.13–17

Before PPIs were invented, drug therapy for GERD symptoms that did not resolve with lifestyle changes consisted of antacids and, later, histamine-2 receptor antagonists. When maximal therapy failed to control symptoms, fundoplication surgery was considered an appropriate next step.

PPIs substantially changed the management of GERD, suppressing acid secretion much better than histamine-2 receptor antagonists. Taken 30 minutes before breakfast, a single daily dose of a PPI normalizes esophageal acid exposure in 67% of patients.18 Adding a second dose 30 minutes before dinner raises the number to more than 90%.19

PPIs have consistently outperformed histamine-2 blockers in the healing of esophagitis and in improving heartburn symptoms and are now the first-line medical therapy for uncomplicated GERD.6,8,20–25

WHEN PPIs WORK, SURGERY OFFERS NO ADVANTAGE

The LOTUS trial (Long-Term Usage of Esomeprazole vs Surgery for Treatment of Chronic GERD) compared long-term drug therapy with surgery to maintain remission of symptoms in GERD.27 In this trial, 554 patients whose symptoms initially responded to the PPI esomeprazole (Nexium) were randomized to continue to receive esomeprazole (n = 266) or to undergo laparoscopic antireflux surgery (288 were randomly assigned, and 248 had the operation). Dose adjustment of the esomeprazole was allowed (20–40 mg/day). A total of 372 patients completed 5 years of follow-up (192 esomeprazole, 180 surgery).

Symptoms stayed in remission in 92% of the esomeprazole group and 85% of the surgery group (P = .048). However, the difference was no longer statistically significant after modeling the effects of study dropout. The rate of severe adverse events was similar in both groups: 24.1% with esomeprazole and 28.6% with surgery.

These findings indicate that if symptoms fully abate with medical therapy, surgery offers no advantage. In addition, patients who desire surgery in the hope of avoiding lifelong drug therapy should be made aware that drug therapy and reoperation are often necessary after surgery.28 In most cases, antireflux surgery is unnecessary for patients whose GERD fully responds to PPI therapy.

IF PPIs FAIL, FURTHER TESTING NEEDED

But many patients who take PPIs still have symptoms, even though these drugs suppress acid secretion and heal esophagitis. In fact, symptoms completely resolve in only about one-half of patients with erosive disease and one-third of those without erosive disease.21

Reasons for an incomplete symptomatic response to PPIs are various. Acid reflux can persist, but this accounts for only 10% of cases.29 About one-third of patients have persistent reflux that is weakly acidic, with a pH higher than 4.29. However, most patients with persistent typical GERD symptoms do not have significant, persistent reflux, or their symptoms are not related to reflux events. In these cases, an alternative cause of the refractory symptoms should be sought.

Further diagnostic testing is indicated when symptoms persist despite PPI therapy. Upper endoscopy will reveal an abnormality such as persistent erosive esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett esophagus, or esophageal cancer in roughly 10% of patients in whom empiric therapy fails.10

Although patients with persistent symptoms have not been enrolled in many randomized controlled trials, a multivariate analysis showed that failure of medical therapy heralds a poor response to surgery.30 Data such as these have led most experts to discourage fundoplication for such patients now, unlike in the pre-PPI era.

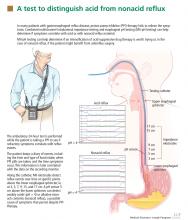

pH and intraluminal impedance testing

However, this recommendation against surgery is not a hard-and-fast rule.

In patients with esophageal regurgitation, most will not achieve adequate relief of symptoms with PPI therapy alone.34 The therapeutic gain of PPI therapy vs placebo averaged just 17% in seven randomized, controlled trials, more than 20% less than the response rate for heartburn.34 This is likely because of structural abnormalities such as reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure, hiatal hernia, or delayed gastric emptying. Antireflux surgery can correct these structural abnormalities or prevent them from causing so much trouble; however, the presence of true regurgitation should first be confirmed by MII testing. If regurgitation is confirmed, antireflux surgery is warranted, particularly in patients with nocturnal symptoms who may be at high risk of aspiration. With careful patient selection, regurgitation symptoms improve in about 90% after surgery.2

In patients with heartburn, if esophageal acid exposure continues to be abnormal on MII-pH testing, then an escalation of therapy may improve symptoms, particularly if symptoms occur during reflux or if they partially responded to PPI therapy. Options in this scenario include alteration or intensification of acid-suppressive therapy, treatment with baclofen (Lioresal), and antireflux surgery.18,35,36 In randomized controlled trials of patients whose symptoms partially responded to PPIs, antireflux surgery has performed similarly to PPIs in terms of improving typical GERD symptoms, particularly regurgitation.27,37–41 Although this scenario is a reasonable indication for antireflux surgery, recommendations should be made with appropriate restraint since it is not easily reversible, some patients experience complications, and up to one-third will have no therapeutic benefit.30

Nonacid reflux. In some cases, MII-pH testing during PPI therapy will reveal reflux of weakly acidic (pH > 4) or alkaline stomach contents, often called “nonacid reflux.”29 Nonacid reflux is often present in patients with esophagitis that persists despite PPI therapy, indicating that even weakly acidic stomach contents can injure the mucosa.42 Since intensifying the acid-suppressive therapy is unlikely to improve these symptoms, antireflux surgery may have a role.

In one study,43 nonacid reflux was well controlled by laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, although 15 (48%) of 31 patients had persistent symptoms of GERD after surgery. No patient had a strong symptom correlation with postoperative reflux events, suggesting an alternative cause of the persistent symptoms. Therefore, antireflux surgery for nonacid reflux should be limited exclusively to patients with strong symptom correlation, and even then it should be considered with restraint, given the limited evidence for benefit and the potential for harm.

If testing is negative. In studies investigating the diagnostic yield of MII-pH testing, more than 50% of patients who had refractory symptoms had a negative MII-pH test.29 In such situations, when the symptoms are strongly correlated with reflux events, the patient is said to have “esophageal hypersensitivity.” A few small studies have suggested that such patients may benefit from surgery, but these data have not been replicated in randomized controlled trials.32

When the testing is negative and there is no correlation between the patient’s symptoms and reflux events, the patient is unlikely to benefit from antireflux surgery. Care of these patients is beyond the scope of this review.

SURGERY RARELY IMPROVES COUGH, ASTHMA, OR LARYNGITIS

GERD has been implicated as a cause of chronic cough, asthma, and laryngitis, although each of these has many potential causes.44–46 Despite these associations, the evidence for therapeutic benefit from antireflux therapy is weak.

PPI therapy shows no benefit over placebo for chronic cough of uncertain etiology, but some benefit if GERD is objectively demonstrated.47 Laryngitis resolved in just 15% of patients on esomeprazole vs 16% of patients on placebo after excluding patients with moderate to severe heartburn.48

In a large randomized controlled trial in patients with asthma, there was no overall improvement in peak flow for the PPI group vs the placebo group, although significant improvement occurred in patients with heartburn and nocturnal respiratory symptoms.46

Potent antisecretory therapy seems to improve extraesophageal symptoms when typical GERD symptoms are also present, but it otherwise has shown little evidence of benefit.

The evidence for a benefit from antireflux surgery in patients with extraesophageal GERD syndromes is even more limited. Although one systematic review49 found that cough and other laryngeal symptoms improved in 60% to 100% of patients with objective evidence of GERD who underwent fundoplication, virtually all of the studies were uncontrolled case series.49

The lone randomized controlled trial in the systematic review compared Nissen fundoplication with ranitidine (Zantac) or antacids only for patients with asthma and GERD, and found no significant difference in peak expiratory flow among the three groups after 2 years. However, asthma symptom scores improved in 75% of the surgical group, 9% of the medical group, and 4% of the control group.50

In a study that was not included in the prior systematic review, patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression who subsequently underwent fundoplication fared no better than those who did not.51

Thus, based on the available data, antireflux surgery is only rarely indicated for extraesophageal symptoms, especially in patients who have no typical GERD symptoms or in patients whose symptoms are refractory to medical therapy.

SURGERY FOR EROSIVE ESOPHAGITIS OR BARRETT ESOPHAGUS IF PPI FAILS

Lifelong antireflux therapy is indicated for patients with severe erosive esophagitis or Barrett esophagus. Erosive esophagitis recurs in more than 80% within 12 months of discontinuing antisecretory therapy.52 Both Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma are strongly associated with GERD, and nearly 10% of patients with chronic reflux have Barrett esophagus.53,54 It is suspected that suppressing reflux reduces the rate of progression of Barrett esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma, but this remains to be proven.

Perhaps the strongest indication for surgery in the PPI era is for patients who have persistent symptoms and severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) despite high-dose PPI therapy. If other causes of persistent esophagitis have been ruled out, fundoplication can induce healing and improve symptoms.55,56 In these cases, surgery is done to induce remission of the disease when maximal medical therapy has been truly unsuccessful.

Randomized controlled trials suggest that medical and surgical therapies are equally effective for preventing the recurrence of erosive esophagitis or the progression of Barrett esophagus. In a study of 225 patients, at 7 years of follow-up, esophagitis had recurred in 10.4% of patients on omeprazole vs 11.8% of those who had undergone antireflux surgery.40 Similarly, open Nissen fundoplication was no different from drug therapy (histamine-2 receptor antagonist or PPI) for progression of Barrett esophagus over a median of 5 years.57 A meta-analysis with nearly 5,000 person-years each in the medical and surgical groups also found no significant difference in rates of cancer progression.58

Notably, symptoms such as dysphagia, flatulence, and the inability to burp occurred significantly more often in the surgical groups in these studies.

In view of these data, antireflux surgery has no significant advantage over medical therapy for maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis or preventing progression of Barrett esophagus. Thus, it should be reserved for patients who do not desire lifelong drug therapy, provided they understand that there is no therapeutic advantage for their esophagitis or for Barrett esophagus.

SPECIFIC INDICATIONS FOR ANTIREFLUX SURGERY

Now that we have PPIs, several situations remain in which surgery for GERD is either indicated or worth considering.

Antireflux surgery is clearly indicated for:

- Patients with erosive esophagitis that does not heal with maximal drug therapy

- Patients with volume regurgitation, particularly if it occurs at night or if there is evidence of aspiration

- Patients who require lifelong treatment for reflux but who have had a serious adverse event related to PPI therapy, such as refractory Clostridium difficile infection.

Antireflux surgery is also worth considering in patients who for personal reasons wish to avoid long-term or lifelong drug therapy.

Patients should be informed, however, that antireflux surgery has not been shown to be better than medical therapy for maintaining remission of symptoms, for preventing progression of Barrett esophagus, or for maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Medical therapy is still the first option for these patients.

Surgery may also be considered in patients with persistent symptoms who have a partial response to medical therapy, who show persistent acidic or weakly acidic reflux on MII-pH testing, and whose symptoms have been correlated with reflux events. Although surgery is not sure to improve their symptoms, benefit is more likely in this patient population compared with those without these characteristics.

Extraesophageal GERD

In patients suspected of having extraesophageal GERD, surgery should be considered if typical GERD symptoms are present and improve with PPI therapy, if the extraesophageal syndrome partially responds to PPI therapy, and if MII-pH testing demonstrates a correlation between symptoms and reflux. Surgery may have a stronger indication in this setting if the patient has nocturnal reflux or extraesophageal symptoms.

When is surgery not an option?

In general, surgery should not be considered in patients who do not have a partial response to PPI therapy or who do not have a strong symptom-reflux correlation on MII-pH testing. In all cases of failed medical therapy without persistent severe erosive disease, the threshold for opting for surgery should be high, given the uncertain response of these patients to surgery.

Peristaltic dysfunction is a relative but not an absolute contraindication to surgery.59

RISKS, BENEFITS OF SURGERY FOR GERD

The patient’s preference for surgery over drug therapy should always be balanced against the risks of surgery, including both short-term and long-term adverse events, to allow the patient to make an adequately informed decision (Table 2).2,26

Adverse events associated with PPI therapy are rare and in many cases the association is debatable.26 Nonetheless, long-term PPI therapy has been most strongly associated with an increased risk of C difficile infection and other enteric infections, although the absolute risk of these events remains low.

Complication rates after antireflux surgery depend on the surgeon’s experience and technique. Death is exceedingly rare. In most high-volume centers, the need to convert from laparoscopic to open fundoplication occurs in fewer than 2.4% of patients.2

Potential perioperative complications include perforation (4%), wound infection (3%), and pneumothorax (2%).2

Antireflux surgery is also associated with a significant risk of dysphagia, bloating, an inability to burp, and excessive flatulence, all of which can markedly impair the quality of life.

A major consideration is that fundoplication is generally irreversible. Reoperation rates have been reported to range from 0% to 15%.2 Furthermore, up to 50% of patients still need medical therapy after surgery.60,61 Of note, only about 25% of patients on medical therapy after surgery will actually have an abnormal pH study.61

MORE STUDY NEEDED

Future studies directly comparing medical and surgical therapy for carefully selected patients with extraesophageal manifestations of GERD and refractory symptoms should help further delineate outcome in this difficult group of patients.

Under development are new drugs that may inhibit transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, as well as minimally invasive procedures, which may alter the indications for surgery in coming years.36

Acknowledgment: The research for this article was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 DK07634).

- Finks JF, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. The rise and fall of antireflux surgery in the United States. Surg Endosc 2006; 20:1698–1701.

- Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Kohn GP, Reardon PR, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD; SAGES Guidelines Committee. Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 2010; 24:2647–2669.

- Richter JE. Typical and atypical presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The role of esophageal testing in diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:75–102.

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:1900–1920.

- Dickman R, Kim JL, Camargo L, et al. Correlation of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms characteristics with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2006; 19:360–365.

- DeVault KR, Castell DO; American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:190–200.

- Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, et al; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology GERD Consensus Group. Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults - update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol 2005; 19:15–35.

- Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:1383–1391.

- Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006; 131:390–401.

- Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, et al. Upper GI tract findings in patients with heartburn in whom proton pump inhibitor treatment failed versus those not receiving antireflux treatment. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71:28–34.

- Dickman R, Mattek N, Holub J, Peters D, Fass R. Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal tract findings in patients with noncardiac chest pain versus those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-related symptoms: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:1173–1179.

- Voutilainen M, Sipponen P, Mecklin JP, Juhola M, Färkkilä M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: prevalence, clinical, endoscopic and histopathological findings in 1,128 consecutive patients referred for endoscopy due to dyspeptic and reflux symptoms. Digestion 2000; 61:6–13.

- Fraser-Moodie CA, Norton B, Gornall C, Magnago S, Weale AR, Holmes GK. Weight loss has an independent beneficial effect on symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients who are overweight. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999; 34:337–340.

- Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA. Bodymass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2340–2348.

- Kjellin A, Ramel S, Rössner S, Thor K. Gastroesophageal reflux in obese patients is not reduced by weight reduction. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31:1047–1051.

- Waring JP, Eastwood TF, Austin JM, Sanowski RA. The immediate effects of cessation of cigarette smoking on gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84:1076–1078.

- Pehl C, Waizenhoefer A, Wendl B, Schmidt T, Schepp W, Pfeiffer A. Effect of low and high fat meals on lower esophageal sphincter motility and gastroesophageal reflux in healthy subjects. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94:1192–1196.

- Bajbouj M, Becker V, Phillip V, Wilhelm D, Schmid RM, Meining A. High-dose esomeprazole for treatment of symptomatic refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease—a prospective pH-metry/impedance-controlled study. Digestion 2009; 80:112–118.

- Charbel S, Khandwala F, Vaezi MF. The role of esophageal pH monitoring in symptomatic patients on PPI therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:283–289.

- Khan M, Santana J, Donnellan C, Preston C, Moayyedi P. Medical treatments in the short term management of reflux oesophagitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;CD003244.

- Dean BB, Gano AD, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2:656–664.

- Sabesin SM, Berlin RG, Humphries TJ, Bradstreet DC, Walton-Bowen KL, Zaidi S. Famotidine relieves symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and heals erosions and ulcerations. Results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. USA Merck Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:2394–2400.

- van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;CD002095.

- Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:1798–1810.

- Venables TL, Newland RD, Patel AC, Hole J, Wilcock C, Turbitt ML. Omeprazole 10 milligrams once daily, omeprazole 20 milligrams once daily, or ranitidine 150 milligrams twice daily, evaluated as initial therapy for the relief of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997; 32:965–973.

- Madanick RD. Proton pump inhibitor side effects and drug interactions: much ado about nothing? Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:39–49.

- Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, et al; LOTUS Trial Collaborators. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305:1969–1977.

- Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: followup of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285:2331–2338.

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut 2006; 55:1398–1402.

- Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3:292–300.

- Becker V, Bajbouj M, Waller K, Schmid RM, Meining A. Clinical trial: persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms despite standard therapy with proton pump inhibitors - a follow-up study of intraluminal-impedance guided therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 26:1355–1360.

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Agrawal A, Adams D, Castell DO. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH monitoring to select patients with persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg 2006; 93:1483–1487.

- del Genio G, Tolone S, del Genio F, et al. Prospective assessment of patient selection for antireflux surgery by combined multichannel intraluminal impedance pH monitoring. J Gastrointest Surg 2008; 12:1491–1496.

- Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N. Response of regurgitation to proton pump inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:1419–1425.

- Koek GH, Sifrim D, Lerut T, Janssens J, Tack J. Effect of the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with symptoms and duodeno-gastro-oesophageal reflux refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Gut 2003; 52:1397–1402.

- Boeckxstaens GE. Reflux inhibitors: a new approach for GERD? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008; 8:685–689.

- Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: One-year follow-up. Surg Innov 2006; 13:238–249.

- Mahon D, Rhodes M, Decadt B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg 2005; 92:695–699.

- Mehta S, Bennett J, Mahon D, Rhodes M. Prospective trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitor therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: Seven-year follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10:1312–1316.

- Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, et al; Nordic GORD Study Group. Seven-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial comparing proton-pump inhibition with surgical therapy for reflux oesophagitis. Br J Surg 2007; 94:198–203.

- Lundell L, Attwood S, Ell C, et al; LOTUS trial collaborators. Comparing laparoscopic antireflux surgery with esomeprazole in the management of patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a 3-year interim analysis of the LOTUS trial. Gut 2008; 57:1207–1213.

- Frazzoni M, Conigliaro R, Melotti G. Weakly acidic refluxes have a major role in the pathogenesis of proton pump inhibitor-resistant reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33:601–606.

- Broeders JA, Bredenoord AJ, Hazebroek EJ, Broeders IA, Gooszen HG, Smout AJ. Effects of anti-reflux surgery on weakly acidic reflux and belching. Gut 2011; 60:435–441.

- American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: guidelines on the use of esophageal pH recording. Gastroenterology 1996; 110:1981.

- el-Serag HB, Sonnenberg A. Comorbid occurrence of laryngeal or pulmonary disease with esophagitis in United States military veterans. Gastroenterology 1997; 113:755–760.

- Kiljander TO, Laitinen JO. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adult asthmatics. Chest 2004; 126:1490–1494.

- Chang AB, Lasserson TJ, Kiljander TO, Connor FL, Gaffney JT, Garske LA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of gastro-oesophageal reflux interventions for chronic cough associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux. BMJ 2006; 332:11–17.

- Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope 2006; 116:254–260.

- Iqbal M, Batch AJ, Spychal RT, Cooper BT. Outcome of surgical fundoplication for extraesophageal (atypical) manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: a systematic review. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2008; 18:789–796.

- Sontag SJ, O’Connell S, Khandelwal S, et al. Asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux: long term results of a randomized trial of medical and surgical antireflux therapies. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:987–999.

- Swoger J, Ponsky J, Hicks DM, et al. Surgical fundoplication in laryngopharyngeal reflux unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression: a controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:433–441.

- Johnson DA, Benjamin SB, Vakil NB, et al. Esomeprazole once daily for 6 months is effective therapy for maintaining healed erosive esophagitis and for controlling gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:27–34.

- Winters C, Spurling TJ, Chobanian SJ, et al. Barrett’s esophagus. A prevalent, occult complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1987; 92:118–124.

- Westhoff B, Brotze S, Weston A, et al. The frequency of Barrett’s esophagus in high-risk patients with chronic GERD. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61:226–231.

- Rosenthal R, Peterli R, Guenin MO, von Flüe M, Ackermann C. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: long-term outcomes and quality of life. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2006; 16:557–561.

- Broeders JA, Draaisma WA, Bredenoord AJ, Smout AJ, Broeders IA, Gooszen HG. Long-term outcome of Nissen fundoplication in non-erosive and erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg 2010; 97:845–352.

- Parrilla P, Martínez de Haro LF, Ortiz A, et al. Long-term results of a randomized prospective study comparing medical and surgical treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. Ann Surg 2003; 237:291–298.

- Corey KE, Schmitz SM, Shaheen NJ. Does a surgical antireflux procedure decrease the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus? A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:2390–2394.

- Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ; American Gastroenterological Association. AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology 2005; 128:209–224.

- Dominitz JA, Dire CA, Billingsley KG, Todd-Stenberg JA. Complications and antireflux medication use after antireflux surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:299–305.

- Lord RV, Kaminski A, Oberg S, et al. Absence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in a majority of patients taking acid suppression medications after Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 2002; 6:3–9.

For most patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is the first choice for treatment.1 But some patients have symptoms that persist despite PPI therapy, some desire surgery despite successful PPI therapy, and some have persistent extraesophageal symptoms or other complications of reflux. For these patients, surgery is an option.2

In this article, we review the management of GERD and clarify the indications for antireflux surgery based on evidence of safety and efficacy.

GERD DEFINED: SYMPTOMS OR COMPLICATIONS

Defining the role of antireflux surgery is difficult, given the variety of presentations and the absence of a gold standard for diagnosing GERD. Most adults experience several episodes of physiologic reflux daily without symptoms.3 But a broad array of symptoms have been attributed to GERD, including chest pain, cough, and sore throat, and some conditions caused by acid reflux (eg, Barrett esophagus) can be asymptomatic.4,5

HEARTBURN ISN’T ALWAYS GERD

Typical GERD presents with the classic symptoms of pyrosis (heartburn) or acid regurgitation, or both.

Although these symptoms are often thought to be specific for GERD, other causes of esophageal injury— eg, eosinophilic esophagitis, infection (Candida, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus), pill-induced esophagitis, or radiation therapy—can produce similar symptoms. Other causes, including coronary artery disease, biliary colic, foregut malignancy, or peptic ulcer disease, should also be considered in patients with supposedly typical GERD. Life-threatening mimics of GERD, such as unstable angina, should be excluded if they are likely, before proceeding with evaluating for possible GERD. Therefore, the initial history and examination should focus on appropriate diagnosis, with careful delineation of symptom quality.

Alarm features for advanced pathology6–8 include involuntary weight loss, dysphagia, vomiting, evidence of gastrointestinal blood loss, anemia, chest pain, and an epigastric mass.7 Admittedly, these features are only mediocre for detecting or excluding gastric or esophageal cancer, with a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity 66%.9 Nevertheless, they should prompt an endoscopic examination. In patients who have alarm features but have not yet been treated for GERD, upper endoscopy can identify an abnormality in about 60% of patients.10–12

PPIs HAVE REPLACED ANTACIDS AND HISTAMINE-2 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

When the symptoms suggest GERD and no alarm features are present, an initial trial of the following lifestyle changes is reasonable:

- Avoiding acidic or refluxogenic foods (coffee, alcohol, chocolate, peppermint, fatty foods, citrus foods)

- Avoiding certain medications (anticholinergics, estrogens, calcium-channel blockers, nitroglycerine, benzodiazepines)

- Losing weight

- Quitting smoking

- Raising the head of the bed

- Staying upright for 2 to 3 hours after meals.

For someone with mild symptoms, these changes pose minimal risk. Unfortunately, they are unlikely to provide adequate symptom control for most patients.13–17

Before PPIs were invented, drug therapy for GERD symptoms that did not resolve with lifestyle changes consisted of antacids and, later, histamine-2 receptor antagonists. When maximal therapy failed to control symptoms, fundoplication surgery was considered an appropriate next step.

PPIs substantially changed the management of GERD, suppressing acid secretion much better than histamine-2 receptor antagonists. Taken 30 minutes before breakfast, a single daily dose of a PPI normalizes esophageal acid exposure in 67% of patients.18 Adding a second dose 30 minutes before dinner raises the number to more than 90%.19

PPIs have consistently outperformed histamine-2 blockers in the healing of esophagitis and in improving heartburn symptoms and are now the first-line medical therapy for uncomplicated GERD.6,8,20–25

WHEN PPIs WORK, SURGERY OFFERS NO ADVANTAGE

The LOTUS trial (Long-Term Usage of Esomeprazole vs Surgery for Treatment of Chronic GERD) compared long-term drug therapy with surgery to maintain remission of symptoms in GERD.27 In this trial, 554 patients whose symptoms initially responded to the PPI esomeprazole (Nexium) were randomized to continue to receive esomeprazole (n = 266) or to undergo laparoscopic antireflux surgery (288 were randomly assigned, and 248 had the operation). Dose adjustment of the esomeprazole was allowed (20–40 mg/day). A total of 372 patients completed 5 years of follow-up (192 esomeprazole, 180 surgery).

Symptoms stayed in remission in 92% of the esomeprazole group and 85% of the surgery group (P = .048). However, the difference was no longer statistically significant after modeling the effects of study dropout. The rate of severe adverse events was similar in both groups: 24.1% with esomeprazole and 28.6% with surgery.

These findings indicate that if symptoms fully abate with medical therapy, surgery offers no advantage. In addition, patients who desire surgery in the hope of avoiding lifelong drug therapy should be made aware that drug therapy and reoperation are often necessary after surgery.28 In most cases, antireflux surgery is unnecessary for patients whose GERD fully responds to PPI therapy.

IF PPIs FAIL, FURTHER TESTING NEEDED

But many patients who take PPIs still have symptoms, even though these drugs suppress acid secretion and heal esophagitis. In fact, symptoms completely resolve in only about one-half of patients with erosive disease and one-third of those without erosive disease.21

Reasons for an incomplete symptomatic response to PPIs are various. Acid reflux can persist, but this accounts for only 10% of cases.29 About one-third of patients have persistent reflux that is weakly acidic, with a pH higher than 4.29. However, most patients with persistent typical GERD symptoms do not have significant, persistent reflux, or their symptoms are not related to reflux events. In these cases, an alternative cause of the refractory symptoms should be sought.

Further diagnostic testing is indicated when symptoms persist despite PPI therapy. Upper endoscopy will reveal an abnormality such as persistent erosive esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett esophagus, or esophageal cancer in roughly 10% of patients in whom empiric therapy fails.10

Although patients with persistent symptoms have not been enrolled in many randomized controlled trials, a multivariate analysis showed that failure of medical therapy heralds a poor response to surgery.30 Data such as these have led most experts to discourage fundoplication for such patients now, unlike in the pre-PPI era.

pH and intraluminal impedance testing

However, this recommendation against surgery is not a hard-and-fast rule.

In patients with esophageal regurgitation, most will not achieve adequate relief of symptoms with PPI therapy alone.34 The therapeutic gain of PPI therapy vs placebo averaged just 17% in seven randomized, controlled trials, more than 20% less than the response rate for heartburn.34 This is likely because of structural abnormalities such as reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure, hiatal hernia, or delayed gastric emptying. Antireflux surgery can correct these structural abnormalities or prevent them from causing so much trouble; however, the presence of true regurgitation should first be confirmed by MII testing. If regurgitation is confirmed, antireflux surgery is warranted, particularly in patients with nocturnal symptoms who may be at high risk of aspiration. With careful patient selection, regurgitation symptoms improve in about 90% after surgery.2

In patients with heartburn, if esophageal acid exposure continues to be abnormal on MII-pH testing, then an escalation of therapy may improve symptoms, particularly if symptoms occur during reflux or if they partially responded to PPI therapy. Options in this scenario include alteration or intensification of acid-suppressive therapy, treatment with baclofen (Lioresal), and antireflux surgery.18,35,36 In randomized controlled trials of patients whose symptoms partially responded to PPIs, antireflux surgery has performed similarly to PPIs in terms of improving typical GERD symptoms, particularly regurgitation.27,37–41 Although this scenario is a reasonable indication for antireflux surgery, recommendations should be made with appropriate restraint since it is not easily reversible, some patients experience complications, and up to one-third will have no therapeutic benefit.30

Nonacid reflux. In some cases, MII-pH testing during PPI therapy will reveal reflux of weakly acidic (pH > 4) or alkaline stomach contents, often called “nonacid reflux.”29 Nonacid reflux is often present in patients with esophagitis that persists despite PPI therapy, indicating that even weakly acidic stomach contents can injure the mucosa.42 Since intensifying the acid-suppressive therapy is unlikely to improve these symptoms, antireflux surgery may have a role.

In one study,43 nonacid reflux was well controlled by laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, although 15 (48%) of 31 patients had persistent symptoms of GERD after surgery. No patient had a strong symptom correlation with postoperative reflux events, suggesting an alternative cause of the persistent symptoms. Therefore, antireflux surgery for nonacid reflux should be limited exclusively to patients with strong symptom correlation, and even then it should be considered with restraint, given the limited evidence for benefit and the potential for harm.

If testing is negative. In studies investigating the diagnostic yield of MII-pH testing, more than 50% of patients who had refractory symptoms had a negative MII-pH test.29 In such situations, when the symptoms are strongly correlated with reflux events, the patient is said to have “esophageal hypersensitivity.” A few small studies have suggested that such patients may benefit from surgery, but these data have not been replicated in randomized controlled trials.32

When the testing is negative and there is no correlation between the patient’s symptoms and reflux events, the patient is unlikely to benefit from antireflux surgery. Care of these patients is beyond the scope of this review.

SURGERY RARELY IMPROVES COUGH, ASTHMA, OR LARYNGITIS

GERD has been implicated as a cause of chronic cough, asthma, and laryngitis, although each of these has many potential causes.44–46 Despite these associations, the evidence for therapeutic benefit from antireflux therapy is weak.

PPI therapy shows no benefit over placebo for chronic cough of uncertain etiology, but some benefit if GERD is objectively demonstrated.47 Laryngitis resolved in just 15% of patients on esomeprazole vs 16% of patients on placebo after excluding patients with moderate to severe heartburn.48

In a large randomized controlled trial in patients with asthma, there was no overall improvement in peak flow for the PPI group vs the placebo group, although significant improvement occurred in patients with heartburn and nocturnal respiratory symptoms.46

Potent antisecretory therapy seems to improve extraesophageal symptoms when typical GERD symptoms are also present, but it otherwise has shown little evidence of benefit.

The evidence for a benefit from antireflux surgery in patients with extraesophageal GERD syndromes is even more limited. Although one systematic review49 found that cough and other laryngeal symptoms improved in 60% to 100% of patients with objective evidence of GERD who underwent fundoplication, virtually all of the studies were uncontrolled case series.49

The lone randomized controlled trial in the systematic review compared Nissen fundoplication with ranitidine (Zantac) or antacids only for patients with asthma and GERD, and found no significant difference in peak expiratory flow among the three groups after 2 years. However, asthma symptom scores improved in 75% of the surgical group, 9% of the medical group, and 4% of the control group.50

In a study that was not included in the prior systematic review, patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression who subsequently underwent fundoplication fared no better than those who did not.51

Thus, based on the available data, antireflux surgery is only rarely indicated for extraesophageal symptoms, especially in patients who have no typical GERD symptoms or in patients whose symptoms are refractory to medical therapy.

SURGERY FOR EROSIVE ESOPHAGITIS OR BARRETT ESOPHAGUS IF PPI FAILS

Lifelong antireflux therapy is indicated for patients with severe erosive esophagitis or Barrett esophagus. Erosive esophagitis recurs in more than 80% within 12 months of discontinuing antisecretory therapy.52 Both Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma are strongly associated with GERD, and nearly 10% of patients with chronic reflux have Barrett esophagus.53,54 It is suspected that suppressing reflux reduces the rate of progression of Barrett esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma, but this remains to be proven.

Perhaps the strongest indication for surgery in the PPI era is for patients who have persistent symptoms and severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) despite high-dose PPI therapy. If other causes of persistent esophagitis have been ruled out, fundoplication can induce healing and improve symptoms.55,56 In these cases, surgery is done to induce remission of the disease when maximal medical therapy has been truly unsuccessful.

Randomized controlled trials suggest that medical and surgical therapies are equally effective for preventing the recurrence of erosive esophagitis or the progression of Barrett esophagus. In a study of 225 patients, at 7 years of follow-up, esophagitis had recurred in 10.4% of patients on omeprazole vs 11.8% of those who had undergone antireflux surgery.40 Similarly, open Nissen fundoplication was no different from drug therapy (histamine-2 receptor antagonist or PPI) for progression of Barrett esophagus over a median of 5 years.57 A meta-analysis with nearly 5,000 person-years each in the medical and surgical groups also found no significant difference in rates of cancer progression.58

Notably, symptoms such as dysphagia, flatulence, and the inability to burp occurred significantly more often in the surgical groups in these studies.

In view of these data, antireflux surgery has no significant advantage over medical therapy for maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis or preventing progression of Barrett esophagus. Thus, it should be reserved for patients who do not desire lifelong drug therapy, provided they understand that there is no therapeutic advantage for their esophagitis or for Barrett esophagus.

SPECIFIC INDICATIONS FOR ANTIREFLUX SURGERY

Now that we have PPIs, several situations remain in which surgery for GERD is either indicated or worth considering.

Antireflux surgery is clearly indicated for:

- Patients with erosive esophagitis that does not heal with maximal drug therapy

- Patients with volume regurgitation, particularly if it occurs at night or if there is evidence of aspiration

- Patients who require lifelong treatment for reflux but who have had a serious adverse event related to PPI therapy, such as refractory Clostridium difficile infection.

Antireflux surgery is also worth considering in patients who for personal reasons wish to avoid long-term or lifelong drug therapy.

Patients should be informed, however, that antireflux surgery has not been shown to be better than medical therapy for maintaining remission of symptoms, for preventing progression of Barrett esophagus, or for maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Medical therapy is still the first option for these patients.

Surgery may also be considered in patients with persistent symptoms who have a partial response to medical therapy, who show persistent acidic or weakly acidic reflux on MII-pH testing, and whose symptoms have been correlated with reflux events. Although surgery is not sure to improve their symptoms, benefit is more likely in this patient population compared with those without these characteristics.

Extraesophageal GERD

In patients suspected of having extraesophageal GERD, surgery should be considered if typical GERD symptoms are present and improve with PPI therapy, if the extraesophageal syndrome partially responds to PPI therapy, and if MII-pH testing demonstrates a correlation between symptoms and reflux. Surgery may have a stronger indication in this setting if the patient has nocturnal reflux or extraesophageal symptoms.

When is surgery not an option?

In general, surgery should not be considered in patients who do not have a partial response to PPI therapy or who do not have a strong symptom-reflux correlation on MII-pH testing. In all cases of failed medical therapy without persistent severe erosive disease, the threshold for opting for surgery should be high, given the uncertain response of these patients to surgery.

Peristaltic dysfunction is a relative but not an absolute contraindication to surgery.59

RISKS, BENEFITS OF SURGERY FOR GERD

The patient’s preference for surgery over drug therapy should always be balanced against the risks of surgery, including both short-term and long-term adverse events, to allow the patient to make an adequately informed decision (Table 2).2,26

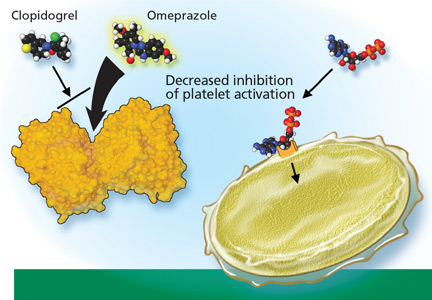

Adverse events associated with PPI therapy are rare and in many cases the association is debatable.26 Nonetheless, long-term PPI therapy has been most strongly associated with an increased risk of C difficile infection and other enteric infections, although the absolute risk of these events remains low.

Complication rates after antireflux surgery depend on the surgeon’s experience and technique. Death is exceedingly rare. In most high-volume centers, the need to convert from laparoscopic to open fundoplication occurs in fewer than 2.4% of patients.2

Potential perioperative complications include perforation (4%), wound infection (3%), and pneumothorax (2%).2

Antireflux surgery is also associated with a significant risk of dysphagia, bloating, an inability to burp, and excessive flatulence, all of which can markedly impair the quality of life.

A major consideration is that fundoplication is generally irreversible. Reoperation rates have been reported to range from 0% to 15%.2 Furthermore, up to 50% of patients still need medical therapy after surgery.60,61 Of note, only about 25% of patients on medical therapy after surgery will actually have an abnormal pH study.61

MORE STUDY NEEDED

Future studies directly comparing medical and surgical therapy for carefully selected patients with extraesophageal manifestations of GERD and refractory symptoms should help further delineate outcome in this difficult group of patients.

Under development are new drugs that may inhibit transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, as well as minimally invasive procedures, which may alter the indications for surgery in coming years.36

Acknowledgment: The research for this article was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 DK07634).

For most patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is the first choice for treatment.1 But some patients have symptoms that persist despite PPI therapy, some desire surgery despite successful PPI therapy, and some have persistent extraesophageal symptoms or other complications of reflux. For these patients, surgery is an option.2

In this article, we review the management of GERD and clarify the indications for antireflux surgery based on evidence of safety and efficacy.

GERD DEFINED: SYMPTOMS OR COMPLICATIONS

Defining the role of antireflux surgery is difficult, given the variety of presentations and the absence of a gold standard for diagnosing GERD. Most adults experience several episodes of physiologic reflux daily without symptoms.3 But a broad array of symptoms have been attributed to GERD, including chest pain, cough, and sore throat, and some conditions caused by acid reflux (eg, Barrett esophagus) can be asymptomatic.4,5

HEARTBURN ISN’T ALWAYS GERD

Typical GERD presents with the classic symptoms of pyrosis (heartburn) or acid regurgitation, or both.

Although these symptoms are often thought to be specific for GERD, other causes of esophageal injury— eg, eosinophilic esophagitis, infection (Candida, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus), pill-induced esophagitis, or radiation therapy—can produce similar symptoms. Other causes, including coronary artery disease, biliary colic, foregut malignancy, or peptic ulcer disease, should also be considered in patients with supposedly typical GERD. Life-threatening mimics of GERD, such as unstable angina, should be excluded if they are likely, before proceeding with evaluating for possible GERD. Therefore, the initial history and examination should focus on appropriate diagnosis, with careful delineation of symptom quality.

Alarm features for advanced pathology6–8 include involuntary weight loss, dysphagia, vomiting, evidence of gastrointestinal blood loss, anemia, chest pain, and an epigastric mass.7 Admittedly, these features are only mediocre for detecting or excluding gastric or esophageal cancer, with a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity 66%.9 Nevertheless, they should prompt an endoscopic examination. In patients who have alarm features but have not yet been treated for GERD, upper endoscopy can identify an abnormality in about 60% of patients.10–12

PPIs HAVE REPLACED ANTACIDS AND HISTAMINE-2 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

When the symptoms suggest GERD and no alarm features are present, an initial trial of the following lifestyle changes is reasonable:

- Avoiding acidic or refluxogenic foods (coffee, alcohol, chocolate, peppermint, fatty foods, citrus foods)

- Avoiding certain medications (anticholinergics, estrogens, calcium-channel blockers, nitroglycerine, benzodiazepines)

- Losing weight

- Quitting smoking

- Raising the head of the bed

- Staying upright for 2 to 3 hours after meals.

For someone with mild symptoms, these changes pose minimal risk. Unfortunately, they are unlikely to provide adequate symptom control for most patients.13–17

Before PPIs were invented, drug therapy for GERD symptoms that did not resolve with lifestyle changes consisted of antacids and, later, histamine-2 receptor antagonists. When maximal therapy failed to control symptoms, fundoplication surgery was considered an appropriate next step.

PPIs substantially changed the management of GERD, suppressing acid secretion much better than histamine-2 receptor antagonists. Taken 30 minutes before breakfast, a single daily dose of a PPI normalizes esophageal acid exposure in 67% of patients.18 Adding a second dose 30 minutes before dinner raises the number to more than 90%.19

PPIs have consistently outperformed histamine-2 blockers in the healing of esophagitis and in improving heartburn symptoms and are now the first-line medical therapy for uncomplicated GERD.6,8,20–25

WHEN PPIs WORK, SURGERY OFFERS NO ADVANTAGE

The LOTUS trial (Long-Term Usage of Esomeprazole vs Surgery for Treatment of Chronic GERD) compared long-term drug therapy with surgery to maintain remission of symptoms in GERD.27 In this trial, 554 patients whose symptoms initially responded to the PPI esomeprazole (Nexium) were randomized to continue to receive esomeprazole (n = 266) or to undergo laparoscopic antireflux surgery (288 were randomly assigned, and 248 had the operation). Dose adjustment of the esomeprazole was allowed (20–40 mg/day). A total of 372 patients completed 5 years of follow-up (192 esomeprazole, 180 surgery).

Symptoms stayed in remission in 92% of the esomeprazole group and 85% of the surgery group (P = .048). However, the difference was no longer statistically significant after modeling the effects of study dropout. The rate of severe adverse events was similar in both groups: 24.1% with esomeprazole and 28.6% with surgery.

These findings indicate that if symptoms fully abate with medical therapy, surgery offers no advantage. In addition, patients who desire surgery in the hope of avoiding lifelong drug therapy should be made aware that drug therapy and reoperation are often necessary after surgery.28 In most cases, antireflux surgery is unnecessary for patients whose GERD fully responds to PPI therapy.

IF PPIs FAIL, FURTHER TESTING NEEDED

But many patients who take PPIs still have symptoms, even though these drugs suppress acid secretion and heal esophagitis. In fact, symptoms completely resolve in only about one-half of patients with erosive disease and one-third of those without erosive disease.21

Reasons for an incomplete symptomatic response to PPIs are various. Acid reflux can persist, but this accounts for only 10% of cases.29 About one-third of patients have persistent reflux that is weakly acidic, with a pH higher than 4.29. However, most patients with persistent typical GERD symptoms do not have significant, persistent reflux, or their symptoms are not related to reflux events. In these cases, an alternative cause of the refractory symptoms should be sought.

Further diagnostic testing is indicated when symptoms persist despite PPI therapy. Upper endoscopy will reveal an abnormality such as persistent erosive esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett esophagus, or esophageal cancer in roughly 10% of patients in whom empiric therapy fails.10

Although patients with persistent symptoms have not been enrolled in many randomized controlled trials, a multivariate analysis showed that failure of medical therapy heralds a poor response to surgery.30 Data such as these have led most experts to discourage fundoplication for such patients now, unlike in the pre-PPI era.

pH and intraluminal impedance testing

However, this recommendation against surgery is not a hard-and-fast rule.

In patients with esophageal regurgitation, most will not achieve adequate relief of symptoms with PPI therapy alone.34 The therapeutic gain of PPI therapy vs placebo averaged just 17% in seven randomized, controlled trials, more than 20% less than the response rate for heartburn.34 This is likely because of structural abnormalities such as reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure, hiatal hernia, or delayed gastric emptying. Antireflux surgery can correct these structural abnormalities or prevent them from causing so much trouble; however, the presence of true regurgitation should first be confirmed by MII testing. If regurgitation is confirmed, antireflux surgery is warranted, particularly in patients with nocturnal symptoms who may be at high risk of aspiration. With careful patient selection, regurgitation symptoms improve in about 90% after surgery.2

In patients with heartburn, if esophageal acid exposure continues to be abnormal on MII-pH testing, then an escalation of therapy may improve symptoms, particularly if symptoms occur during reflux or if they partially responded to PPI therapy. Options in this scenario include alteration or intensification of acid-suppressive therapy, treatment with baclofen (Lioresal), and antireflux surgery.18,35,36 In randomized controlled trials of patients whose symptoms partially responded to PPIs, antireflux surgery has performed similarly to PPIs in terms of improving typical GERD symptoms, particularly regurgitation.27,37–41 Although this scenario is a reasonable indication for antireflux surgery, recommendations should be made with appropriate restraint since it is not easily reversible, some patients experience complications, and up to one-third will have no therapeutic benefit.30

Nonacid reflux. In some cases, MII-pH testing during PPI therapy will reveal reflux of weakly acidic (pH > 4) or alkaline stomach contents, often called “nonacid reflux.”29 Nonacid reflux is often present in patients with esophagitis that persists despite PPI therapy, indicating that even weakly acidic stomach contents can injure the mucosa.42 Since intensifying the acid-suppressive therapy is unlikely to improve these symptoms, antireflux surgery may have a role.

In one study,43 nonacid reflux was well controlled by laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, although 15 (48%) of 31 patients had persistent symptoms of GERD after surgery. No patient had a strong symptom correlation with postoperative reflux events, suggesting an alternative cause of the persistent symptoms. Therefore, antireflux surgery for nonacid reflux should be limited exclusively to patients with strong symptom correlation, and even then it should be considered with restraint, given the limited evidence for benefit and the potential for harm.

If testing is negative. In studies investigating the diagnostic yield of MII-pH testing, more than 50% of patients who had refractory symptoms had a negative MII-pH test.29 In such situations, when the symptoms are strongly correlated with reflux events, the patient is said to have “esophageal hypersensitivity.” A few small studies have suggested that such patients may benefit from surgery, but these data have not been replicated in randomized controlled trials.32

When the testing is negative and there is no correlation between the patient’s symptoms and reflux events, the patient is unlikely to benefit from antireflux surgery. Care of these patients is beyond the scope of this review.

SURGERY RARELY IMPROVES COUGH, ASTHMA, OR LARYNGITIS

GERD has been implicated as a cause of chronic cough, asthma, and laryngitis, although each of these has many potential causes.44–46 Despite these associations, the evidence for therapeutic benefit from antireflux therapy is weak.

PPI therapy shows no benefit over placebo for chronic cough of uncertain etiology, but some benefit if GERD is objectively demonstrated.47 Laryngitis resolved in just 15% of patients on esomeprazole vs 16% of patients on placebo after excluding patients with moderate to severe heartburn.48

In a large randomized controlled trial in patients with asthma, there was no overall improvement in peak flow for the PPI group vs the placebo group, although significant improvement occurred in patients with heartburn and nocturnal respiratory symptoms.46

Potent antisecretory therapy seems to improve extraesophageal symptoms when typical GERD symptoms are also present, but it otherwise has shown little evidence of benefit.

The evidence for a benefit from antireflux surgery in patients with extraesophageal GERD syndromes is even more limited. Although one systematic review49 found that cough and other laryngeal symptoms improved in 60% to 100% of patients with objective evidence of GERD who underwent fundoplication, virtually all of the studies were uncontrolled case series.49

The lone randomized controlled trial in the systematic review compared Nissen fundoplication with ranitidine (Zantac) or antacids only for patients with asthma and GERD, and found no significant difference in peak expiratory flow among the three groups after 2 years. However, asthma symptom scores improved in 75% of the surgical group, 9% of the medical group, and 4% of the control group.50

In a study that was not included in the prior systematic review, patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression who subsequently underwent fundoplication fared no better than those who did not.51

Thus, based on the available data, antireflux surgery is only rarely indicated for extraesophageal symptoms, especially in patients who have no typical GERD symptoms or in patients whose symptoms are refractory to medical therapy.

SURGERY FOR EROSIVE ESOPHAGITIS OR BARRETT ESOPHAGUS IF PPI FAILS

Lifelong antireflux therapy is indicated for patients with severe erosive esophagitis or Barrett esophagus. Erosive esophagitis recurs in more than 80% within 12 months of discontinuing antisecretory therapy.52 Both Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma are strongly associated with GERD, and nearly 10% of patients with chronic reflux have Barrett esophagus.53,54 It is suspected that suppressing reflux reduces the rate of progression of Barrett esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma, but this remains to be proven.

Perhaps the strongest indication for surgery in the PPI era is for patients who have persistent symptoms and severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) despite high-dose PPI therapy. If other causes of persistent esophagitis have been ruled out, fundoplication can induce healing and improve symptoms.55,56 In these cases, surgery is done to induce remission of the disease when maximal medical therapy has been truly unsuccessful.

Randomized controlled trials suggest that medical and surgical therapies are equally effective for preventing the recurrence of erosive esophagitis or the progression of Barrett esophagus. In a study of 225 patients, at 7 years of follow-up, esophagitis had recurred in 10.4% of patients on omeprazole vs 11.8% of those who had undergone antireflux surgery.40 Similarly, open Nissen fundoplication was no different from drug therapy (histamine-2 receptor antagonist or PPI) for progression of Barrett esophagus over a median of 5 years.57 A meta-analysis with nearly 5,000 person-years each in the medical and surgical groups also found no significant difference in rates of cancer progression.58

Notably, symptoms such as dysphagia, flatulence, and the inability to burp occurred significantly more often in the surgical groups in these studies.

In view of these data, antireflux surgery has no significant advantage over medical therapy for maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis or preventing progression of Barrett esophagus. Thus, it should be reserved for patients who do not desire lifelong drug therapy, provided they understand that there is no therapeutic advantage for their esophagitis or for Barrett esophagus.

SPECIFIC INDICATIONS FOR ANTIREFLUX SURGERY

Now that we have PPIs, several situations remain in which surgery for GERD is either indicated or worth considering.

Antireflux surgery is clearly indicated for:

- Patients with erosive esophagitis that does not heal with maximal drug therapy

- Patients with volume regurgitation, particularly if it occurs at night or if there is evidence of aspiration

- Patients who require lifelong treatment for reflux but who have had a serious adverse event related to PPI therapy, such as refractory Clostridium difficile infection.

Antireflux surgery is also worth considering in patients who for personal reasons wish to avoid long-term or lifelong drug therapy.

Patients should be informed, however, that antireflux surgery has not been shown to be better than medical therapy for maintaining remission of symptoms, for preventing progression of Barrett esophagus, or for maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Medical therapy is still the first option for these patients.

Surgery may also be considered in patients with persistent symptoms who have a partial response to medical therapy, who show persistent acidic or weakly acidic reflux on MII-pH testing, and whose symptoms have been correlated with reflux events. Although surgery is not sure to improve their symptoms, benefit is more likely in this patient population compared with those without these characteristics.

Extraesophageal GERD

In patients suspected of having extraesophageal GERD, surgery should be considered if typical GERD symptoms are present and improve with PPI therapy, if the extraesophageal syndrome partially responds to PPI therapy, and if MII-pH testing demonstrates a correlation between symptoms and reflux. Surgery may have a stronger indication in this setting if the patient has nocturnal reflux or extraesophageal symptoms.

When is surgery not an option?

In general, surgery should not be considered in patients who do not have a partial response to PPI therapy or who do not have a strong symptom-reflux correlation on MII-pH testing. In all cases of failed medical therapy without persistent severe erosive disease, the threshold for opting for surgery should be high, given the uncertain response of these patients to surgery.

Peristaltic dysfunction is a relative but not an absolute contraindication to surgery.59

RISKS, BENEFITS OF SURGERY FOR GERD

The patient’s preference for surgery over drug therapy should always be balanced against the risks of surgery, including both short-term and long-term adverse events, to allow the patient to make an adequately informed decision (Table 2).2,26

Adverse events associated with PPI therapy are rare and in many cases the association is debatable.26 Nonetheless, long-term PPI therapy has been most strongly associated with an increased risk of C difficile infection and other enteric infections, although the absolute risk of these events remains low.

Complication rates after antireflux surgery depend on the surgeon’s experience and technique. Death is exceedingly rare. In most high-volume centers, the need to convert from laparoscopic to open fundoplication occurs in fewer than 2.4% of patients.2

Potential perioperative complications include perforation (4%), wound infection (3%), and pneumothorax (2%).2

Antireflux surgery is also associated with a significant risk of dysphagia, bloating, an inability to burp, and excessive flatulence, all of which can markedly impair the quality of life.

A major consideration is that fundoplication is generally irreversible. Reoperation rates have been reported to range from 0% to 15%.2 Furthermore, up to 50% of patients still need medical therapy after surgery.60,61 Of note, only about 25% of patients on medical therapy after surgery will actually have an abnormal pH study.61

MORE STUDY NEEDED

Future studies directly comparing medical and surgical therapy for carefully selected patients with extraesophageal manifestations of GERD and refractory symptoms should help further delineate outcome in this difficult group of patients.

Under development are new drugs that may inhibit transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, as well as minimally invasive procedures, which may alter the indications for surgery in coming years.36

Acknowledgment: The research for this article was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 DK07634).

- Finks JF, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. The rise and fall of antireflux surgery in the United States. Surg Endosc 2006; 20:1698–1701.

- Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Kohn GP, Reardon PR, Richardson WS, Fanelli RD; SAGES Guidelines Committee. Guidelines for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Endosc 2010; 24:2647–2669.

- Richter JE. Typical and atypical presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The role of esophageal testing in diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:75–102.

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:1900–1920.

- Dickman R, Kim JL, Camargo L, et al. Correlation of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms characteristics with long-segment Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2006; 19:360–365.

- DeVault KR, Castell DO; American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:190–200.

- Armstrong D, Marshall JK, Chiba N, et al; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology GERD Consensus Group. Canadian Consensus Conference on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults - update 2004. Can J Gastroenterol 2005; 19:15–35.

- Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2008; 135:1383–1391.

- Vakil N, Moayyedi P, Fennerty MB, Talley NJ. Limited value of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2006; 131:390–401.

- Poh CH, Gasiorowska A, Navarro-Rodriguez T, et al. Upper GI tract findings in patients with heartburn in whom proton pump inhibitor treatment failed versus those not receiving antireflux treatment. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71:28–34.

- Dickman R, Mattek N, Holub J, Peters D, Fass R. Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal tract findings in patients with noncardiac chest pain versus those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-related symptoms: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:1173–1179.

- Voutilainen M, Sipponen P, Mecklin JP, Juhola M, Färkkilä M. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: prevalence, clinical, endoscopic and histopathological findings in 1,128 consecutive patients referred for endoscopy due to dyspeptic and reflux symptoms. Digestion 2000; 61:6–13.

- Fraser-Moodie CA, Norton B, Gornall C, Magnago S, Weale AR, Holmes GK. Weight loss has an independent beneficial effect on symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients who are overweight. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999; 34:337–340.

- Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA. Bodymass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2340–2348.

- Kjellin A, Ramel S, Rössner S, Thor K. Gastroesophageal reflux in obese patients is not reduced by weight reduction. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31:1047–1051.

- Waring JP, Eastwood TF, Austin JM, Sanowski RA. The immediate effects of cessation of cigarette smoking on gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84:1076–1078.

- Pehl C, Waizenhoefer A, Wendl B, Schmidt T, Schepp W, Pfeiffer A. Effect of low and high fat meals on lower esophageal sphincter motility and gastroesophageal reflux in healthy subjects. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94:1192–1196.

- Bajbouj M, Becker V, Phillip V, Wilhelm D, Schmid RM, Meining A. High-dose esomeprazole for treatment of symptomatic refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease—a prospective pH-metry/impedance-controlled study. Digestion 2009; 80:112–118.

- Charbel S, Khandwala F, Vaezi MF. The role of esophageal pH monitoring in symptomatic patients on PPI therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:283–289.

- Khan M, Santana J, Donnellan C, Preston C, Moayyedi P. Medical treatments in the short term management of reflux oesophagitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;CD003244.

- Dean BB, Gano AD, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2:656–664.

- Sabesin SM, Berlin RG, Humphries TJ, Bradstreet DC, Walton-Bowen KL, Zaidi S. Famotidine relieves symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease and heals erosions and ulcerations. Results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. USA Merck Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:2394–2400.

- van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;CD002095.

- Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:1798–1810.

- Venables TL, Newland RD, Patel AC, Hole J, Wilcock C, Turbitt ML. Omeprazole 10 milligrams once daily, omeprazole 20 milligrams once daily, or ranitidine 150 milligrams twice daily, evaluated as initial therapy for the relief of symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997; 32:965–973.

- Madanick RD. Proton pump inhibitor side effects and drug interactions: much ado about nothing? Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:39–49.

- Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, et al; LOTUS Trial Collaborators. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305:1969–1977.

- Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: followup of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 285:2331–2338.

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut 2006; 55:1398–1402.

- Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3:292–300.

- Becker V, Bajbouj M, Waller K, Schmid RM, Meining A. Clinical trial: persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms despite standard therapy with proton pump inhibitors - a follow-up study of intraluminal-impedance guided therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 26:1355–1360.

- Mainie I, Tutuian R, Agrawal A, Adams D, Castell DO. Combined multichannel intraluminal impedance-pH monitoring to select patients with persistent gastro-oesophageal reflux for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg 2006; 93:1483–1487.

- del Genio G, Tolone S, del Genio F, et al. Prospective assessment of patient selection for antireflux surgery by combined multichannel intraluminal impedance pH monitoring. J Gastrointest Surg 2008; 12:1491–1496.

- Kahrilas PJ, Howden CW, Hughes N. Response of regurgitation to proton pump inhibitor therapy in clinical trials of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:1419–1425.

- Koek GH, Sifrim D, Lerut T, Janssens J, Tack J. Effect of the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with symptoms and duodeno-gastro-oesophageal reflux refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Gut 2003; 52:1397–1402.

- Boeckxstaens GE. Reflux inhibitors: a new approach for GERD? Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008; 8:685–689.