User login

Persistent fever investigation saves patient's life

THE CASE

A 47-year-old African American woman was admitted to the hospital with pulmonary edema revealed on a computed tomography (CT) scan. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), hypertension, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The patient had been hospitalized one month earlier for lupus nephritis with a hypertensive emergency that led to a seizure. During this earlier hospitalization, she was given a diagnosis of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Two weeks into her more recent hospitalization, the patient developed a fever that was accompanied by cough and fatigue. By the third week, there was no identified cause of the fever, and the patient met the criteria for fever of unknown origin (FUO).

Her medications included cyclophosphamide, prednisone, nebivolol, clonidine, phenytoin, and epoetin alfa. The patient was also receiving dialysis every other day. Chest x-ray findings suggested pneumonia, and the patient was treated with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. However, her fever persisted after completing the antibiotics. Central line sepsis was high in the differential, as the patient was on dialysis, but blood and catheter tip cultures were negative. Chest and abdominal CT scans showed no new disease process. Urine and sputum cultures were collected and were negative for infection. Drug-induced fever was then suspected, but was ruled out when the fever persisted after the removal of potential offending agents (phenytoin, nebivolol, and cyclophosphamide).

THE DIAGNOSIS

We then followed the American Academy of Family Physicians’ diagnostic protocol for FUO.1

Initial labs included a complete blood count (CBC), 2 blood cultures, a urine culture, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a purified protein derivative skin test, chest and abdominal CT scans, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) levels (since this patient had known SLE). The patient’s hemoglobin level and mean corpuscular volume were consistent with normocytic anemia, which was attributed to the ESRD. The ESR was mildly elevated at 46 mm/hr, but dsDNA was not, ruling out a lupus flare. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 82 K/mcL) and lymphocytopenia (absolute lymphocyte count, 0.2 K/mcL) were assumed to be secondary to cyclophosphamide use.

Because the initial labs were non-diagnostic, we proceeded with a sputum stain and culture, human immunodeficiency virus testing, a hepatitis panel, and a peripheral blood smear.1 All were negative except for the peripheral blood smear, which showed hemophagocytic cells. This was the first finding that brought hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) into the differential.

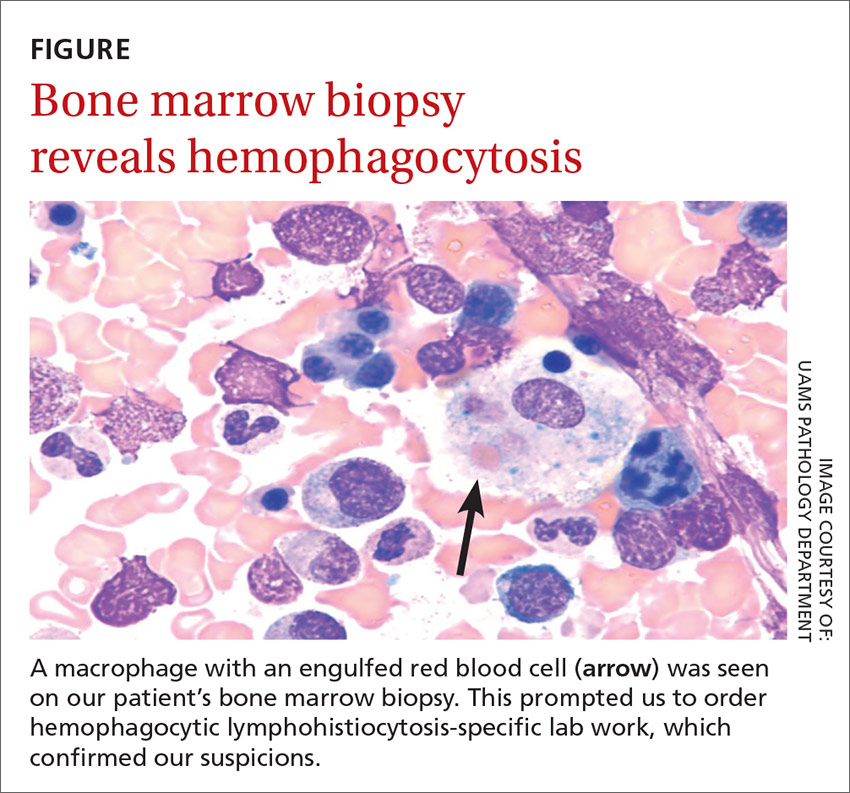

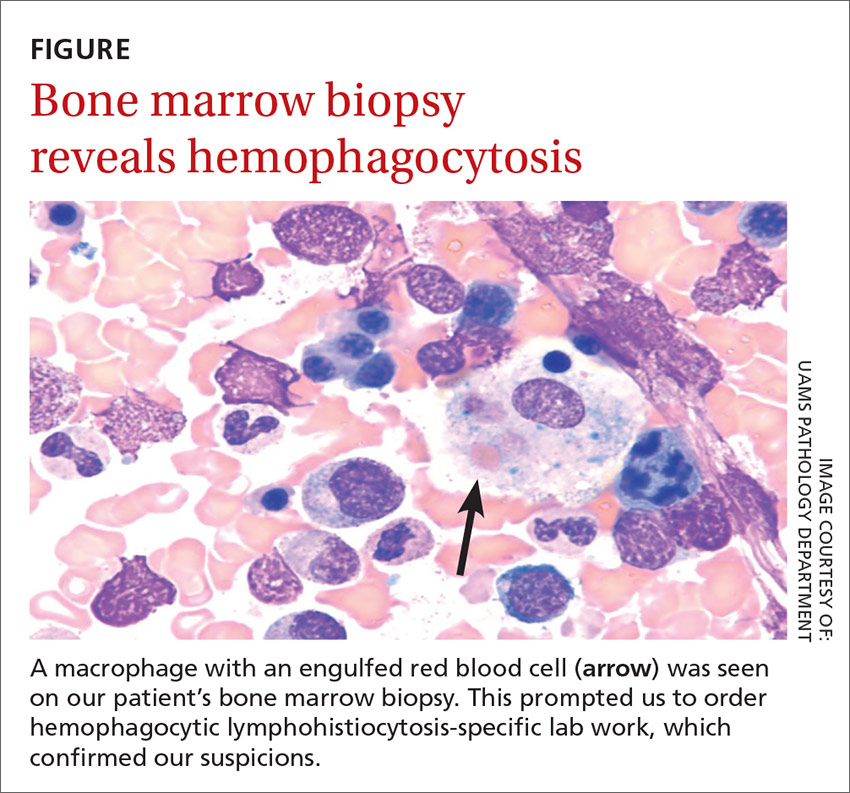

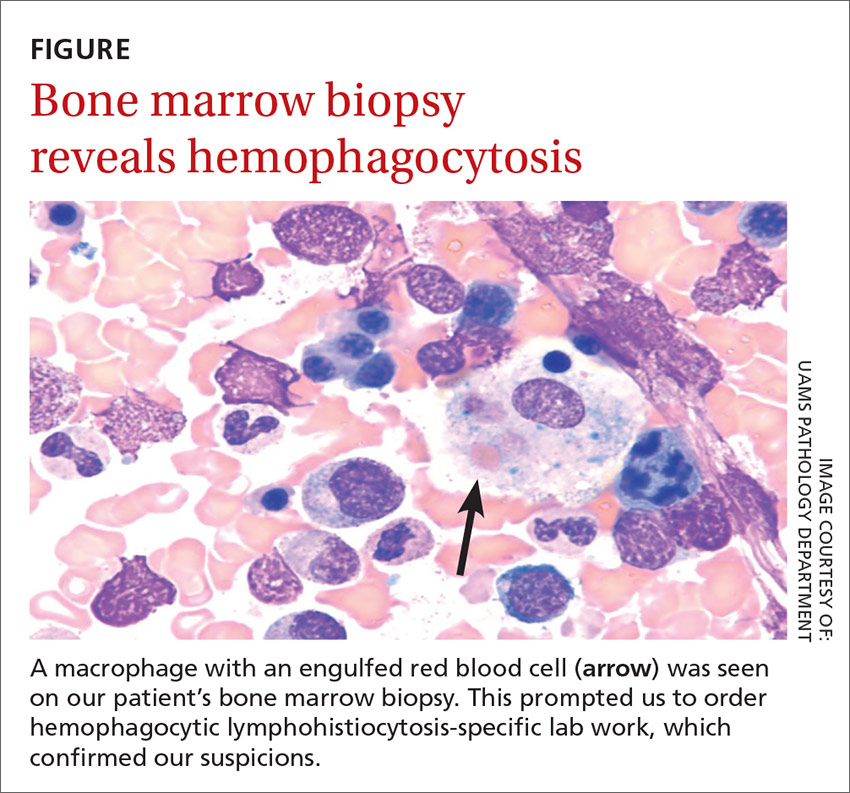

We then performed a bone marrow biopsy (FIGURE), which also revealed hemophagocytic cells, so we ordered HLH-specific labs (more on those in a bit). Liver enzymes were elevated to 3 times their normal value. Triglycerides (414 mg/dL), ferritin (>15,000 ng/mL), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor levels (>20,000 pg/m) were also elevated.

The patient was tested for herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV), since these viruses are associated with HLH. She had 3.1 million copies/mL of CMV, leading to the diagnosis of secondary HLH. This diagnosis might not have been made if not for a persistent fever investigation.

DISCUSSION

HLH is a life-threatening syndrome of excessive immune activation that results in tissue damage.2 There are primary and secondary forms, but they share the same mechanism of impaired regulation of cytotoxic granules and cytokines. Primary HLH results from a congenital gene mutation,3 while secondary HLH is triggered by an autoimmune or inflammatory disease or an infection.4 EBV is the most common viral etiology, followed closely by CMV.5

The diagnosis may be established genetically (based on mutations of the genes loci PRF1, UNC13D, or STX11) or by fulfillment of 5 out of 8 criteria: fever; splenomegaly; cytopenia; hypertriglyceridemia; hypofibrinogenemia; hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes; low or absent natural killer cell activity; and an elevated ferritin level (>500 ng/mL). Elevated soluble CD25 and IL-2 receptor markers are HLH-specific markers.3 This patient had fever, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hemophagocytosis, and elevated ferritin with elevated IL-2, meeting the criteria for secondary HLH.

First treat the underlying condition, then the HLH

Treatment for HLH includes treating the underlying condition (such as EBV or CMV) with antiretroviral medications, and using immunosuppressive agents such as chemotherapy drugs and steroids for the HLH.

Our patient was treated with valganciclovir 900 mg/d for 2 weeks for the CMV and an etoposide/prednisone taper for 3 months for HLH chemotherapy and suppression. Within one month, her CMV viral load decreased to <300 copies/mL and her fever resolved. Ferritin, triglycerides, and liver enzyme levels returned to normal within 3 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

FUO can be frustrating for both the physician and the patient. Not only is the differential large, but testing is extensive. It is important to get a thorough history and to consider medications as the cause. Testing should be patient-specific and systematic. Persistent investigation is critical to saving the patient’s life.

1. Roth AR, Basello GM. Approach to the adult patient with fever of unknown origin. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2223-2228.

2. Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: recentinsights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:S82-S89.

3. Larroche C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: diagnosis and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:356-361.

4. Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:814-822.

5. Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes—an update. Blood Rev. 2014;28:135-142.

THE CASE

A 47-year-old African American woman was admitted to the hospital with pulmonary edema revealed on a computed tomography (CT) scan. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), hypertension, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The patient had been hospitalized one month earlier for lupus nephritis with a hypertensive emergency that led to a seizure. During this earlier hospitalization, she was given a diagnosis of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Two weeks into her more recent hospitalization, the patient developed a fever that was accompanied by cough and fatigue. By the third week, there was no identified cause of the fever, and the patient met the criteria for fever of unknown origin (FUO).

Her medications included cyclophosphamide, prednisone, nebivolol, clonidine, phenytoin, and epoetin alfa. The patient was also receiving dialysis every other day. Chest x-ray findings suggested pneumonia, and the patient was treated with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. However, her fever persisted after completing the antibiotics. Central line sepsis was high in the differential, as the patient was on dialysis, but blood and catheter tip cultures were negative. Chest and abdominal CT scans showed no new disease process. Urine and sputum cultures were collected and were negative for infection. Drug-induced fever was then suspected, but was ruled out when the fever persisted after the removal of potential offending agents (phenytoin, nebivolol, and cyclophosphamide).

THE DIAGNOSIS

We then followed the American Academy of Family Physicians’ diagnostic protocol for FUO.1

Initial labs included a complete blood count (CBC), 2 blood cultures, a urine culture, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a purified protein derivative skin test, chest and abdominal CT scans, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) levels (since this patient had known SLE). The patient’s hemoglobin level and mean corpuscular volume were consistent with normocytic anemia, which was attributed to the ESRD. The ESR was mildly elevated at 46 mm/hr, but dsDNA was not, ruling out a lupus flare. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 82 K/mcL) and lymphocytopenia (absolute lymphocyte count, 0.2 K/mcL) were assumed to be secondary to cyclophosphamide use.

Because the initial labs were non-diagnostic, we proceeded with a sputum stain and culture, human immunodeficiency virus testing, a hepatitis panel, and a peripheral blood smear.1 All were negative except for the peripheral blood smear, which showed hemophagocytic cells. This was the first finding that brought hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) into the differential.

We then performed a bone marrow biopsy (FIGURE), which also revealed hemophagocytic cells, so we ordered HLH-specific labs (more on those in a bit). Liver enzymes were elevated to 3 times their normal value. Triglycerides (414 mg/dL), ferritin (>15,000 ng/mL), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor levels (>20,000 pg/m) were also elevated.

The patient was tested for herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV), since these viruses are associated with HLH. She had 3.1 million copies/mL of CMV, leading to the diagnosis of secondary HLH. This diagnosis might not have been made if not for a persistent fever investigation.

DISCUSSION

HLH is a life-threatening syndrome of excessive immune activation that results in tissue damage.2 There are primary and secondary forms, but they share the same mechanism of impaired regulation of cytotoxic granules and cytokines. Primary HLH results from a congenital gene mutation,3 while secondary HLH is triggered by an autoimmune or inflammatory disease or an infection.4 EBV is the most common viral etiology, followed closely by CMV.5

The diagnosis may be established genetically (based on mutations of the genes loci PRF1, UNC13D, or STX11) or by fulfillment of 5 out of 8 criteria: fever; splenomegaly; cytopenia; hypertriglyceridemia; hypofibrinogenemia; hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes; low or absent natural killer cell activity; and an elevated ferritin level (>500 ng/mL). Elevated soluble CD25 and IL-2 receptor markers are HLH-specific markers.3 This patient had fever, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hemophagocytosis, and elevated ferritin with elevated IL-2, meeting the criteria for secondary HLH.

First treat the underlying condition, then the HLH

Treatment for HLH includes treating the underlying condition (such as EBV or CMV) with antiretroviral medications, and using immunosuppressive agents such as chemotherapy drugs and steroids for the HLH.

Our patient was treated with valganciclovir 900 mg/d for 2 weeks for the CMV and an etoposide/prednisone taper for 3 months for HLH chemotherapy and suppression. Within one month, her CMV viral load decreased to <300 copies/mL and her fever resolved. Ferritin, triglycerides, and liver enzyme levels returned to normal within 3 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

FUO can be frustrating for both the physician and the patient. Not only is the differential large, but testing is extensive. It is important to get a thorough history and to consider medications as the cause. Testing should be patient-specific and systematic. Persistent investigation is critical to saving the patient’s life.

THE CASE

A 47-year-old African American woman was admitted to the hospital with pulmonary edema revealed on a computed tomography (CT) scan. She had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), hypertension, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). The patient had been hospitalized one month earlier for lupus nephritis with a hypertensive emergency that led to a seizure. During this earlier hospitalization, she was given a diagnosis of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

Two weeks into her more recent hospitalization, the patient developed a fever that was accompanied by cough and fatigue. By the third week, there was no identified cause of the fever, and the patient met the criteria for fever of unknown origin (FUO).

Her medications included cyclophosphamide, prednisone, nebivolol, clonidine, phenytoin, and epoetin alfa. The patient was also receiving dialysis every other day. Chest x-ray findings suggested pneumonia, and the patient was treated with vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam. However, her fever persisted after completing the antibiotics. Central line sepsis was high in the differential, as the patient was on dialysis, but blood and catheter tip cultures were negative. Chest and abdominal CT scans showed no new disease process. Urine and sputum cultures were collected and were negative for infection. Drug-induced fever was then suspected, but was ruled out when the fever persisted after the removal of potential offending agents (phenytoin, nebivolol, and cyclophosphamide).

THE DIAGNOSIS

We then followed the American Academy of Family Physicians’ diagnostic protocol for FUO.1

Initial labs included a complete blood count (CBC), 2 blood cultures, a urine culture, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a purified protein derivative skin test, chest and abdominal CT scans, and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) levels (since this patient had known SLE). The patient’s hemoglobin level and mean corpuscular volume were consistent with normocytic anemia, which was attributed to the ESRD. The ESR was mildly elevated at 46 mm/hr, but dsDNA was not, ruling out a lupus flare. Thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 82 K/mcL) and lymphocytopenia (absolute lymphocyte count, 0.2 K/mcL) were assumed to be secondary to cyclophosphamide use.

Because the initial labs were non-diagnostic, we proceeded with a sputum stain and culture, human immunodeficiency virus testing, a hepatitis panel, and a peripheral blood smear.1 All were negative except for the peripheral blood smear, which showed hemophagocytic cells. This was the first finding that brought hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) into the differential.

We then performed a bone marrow biopsy (FIGURE), which also revealed hemophagocytic cells, so we ordered HLH-specific labs (more on those in a bit). Liver enzymes were elevated to 3 times their normal value. Triglycerides (414 mg/dL), ferritin (>15,000 ng/mL), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor levels (>20,000 pg/m) were also elevated.

The patient was tested for herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV), since these viruses are associated with HLH. She had 3.1 million copies/mL of CMV, leading to the diagnosis of secondary HLH. This diagnosis might not have been made if not for a persistent fever investigation.

DISCUSSION

HLH is a life-threatening syndrome of excessive immune activation that results in tissue damage.2 There are primary and secondary forms, but they share the same mechanism of impaired regulation of cytotoxic granules and cytokines. Primary HLH results from a congenital gene mutation,3 while secondary HLH is triggered by an autoimmune or inflammatory disease or an infection.4 EBV is the most common viral etiology, followed closely by CMV.5

The diagnosis may be established genetically (based on mutations of the genes loci PRF1, UNC13D, or STX11) or by fulfillment of 5 out of 8 criteria: fever; splenomegaly; cytopenia; hypertriglyceridemia; hypofibrinogenemia; hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes; low or absent natural killer cell activity; and an elevated ferritin level (>500 ng/mL). Elevated soluble CD25 and IL-2 receptor markers are HLH-specific markers.3 This patient had fever, cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hemophagocytosis, and elevated ferritin with elevated IL-2, meeting the criteria for secondary HLH.

First treat the underlying condition, then the HLH

Treatment for HLH includes treating the underlying condition (such as EBV or CMV) with antiretroviral medications, and using immunosuppressive agents such as chemotherapy drugs and steroids for the HLH.

Our patient was treated with valganciclovir 900 mg/d for 2 weeks for the CMV and an etoposide/prednisone taper for 3 months for HLH chemotherapy and suppression. Within one month, her CMV viral load decreased to <300 copies/mL and her fever resolved. Ferritin, triglycerides, and liver enzyme levels returned to normal within 3 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

FUO can be frustrating for both the physician and the patient. Not only is the differential large, but testing is extensive. It is important to get a thorough history and to consider medications as the cause. Testing should be patient-specific and systematic. Persistent investigation is critical to saving the patient’s life.

1. Roth AR, Basello GM. Approach to the adult patient with fever of unknown origin. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2223-2228.

2. Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: recentinsights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:S82-S89.

3. Larroche C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: diagnosis and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:356-361.

4. Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:814-822.

5. Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes—an update. Blood Rev. 2014;28:135-142.

1. Roth AR, Basello GM. Approach to the adult patient with fever of unknown origin. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2223-2228.

2. Filipovich A, McClain K, Grom A. Histiocytic disorders: recentinsights into pathophysiology and practical guidelines. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:S82-S89.

3. Larroche C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: diagnosis and treatment. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:356-361.

4. Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:814-822.

5. Janka GE, Lehmberg K. Hemophagocytic syndromes—an update. Blood Rev. 2014;28:135-142.

Epistaxis, mass in right nostril • Dx?

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

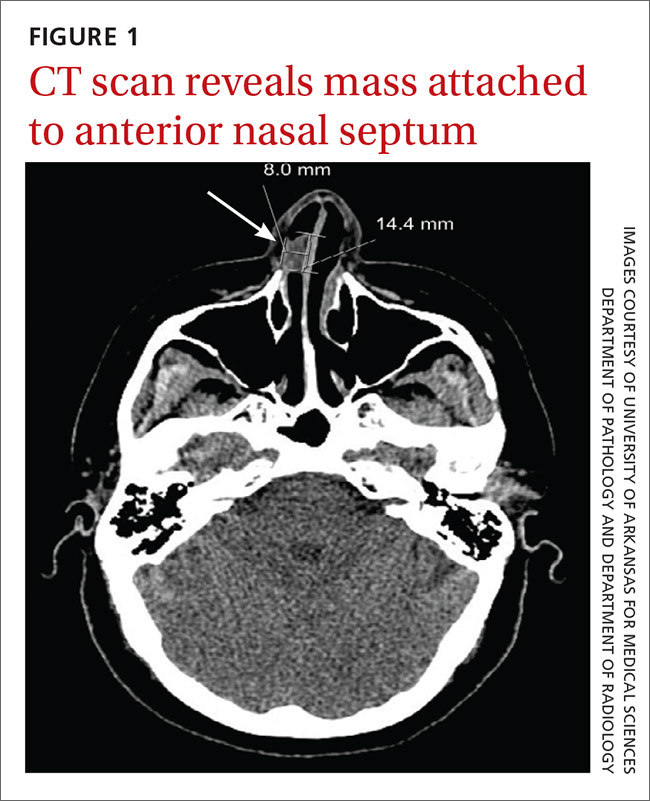

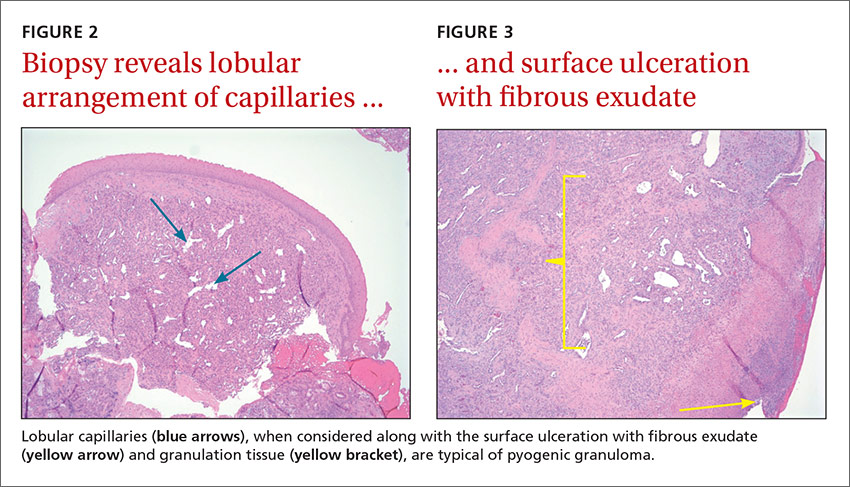

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

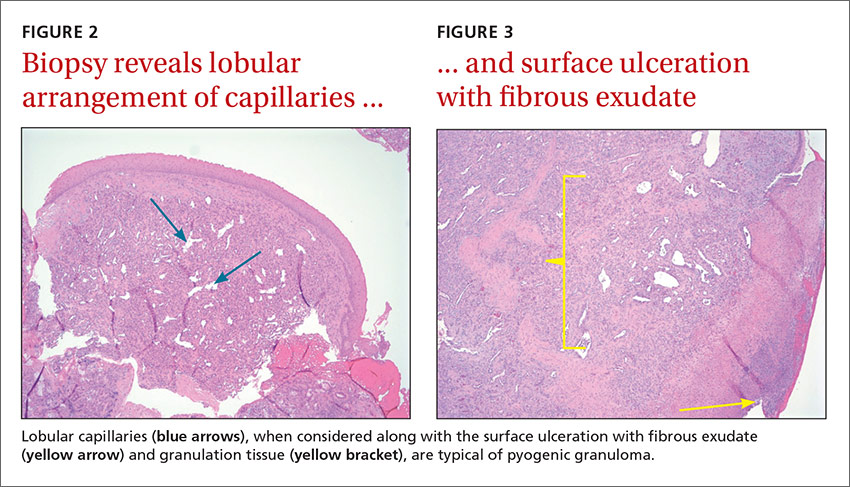

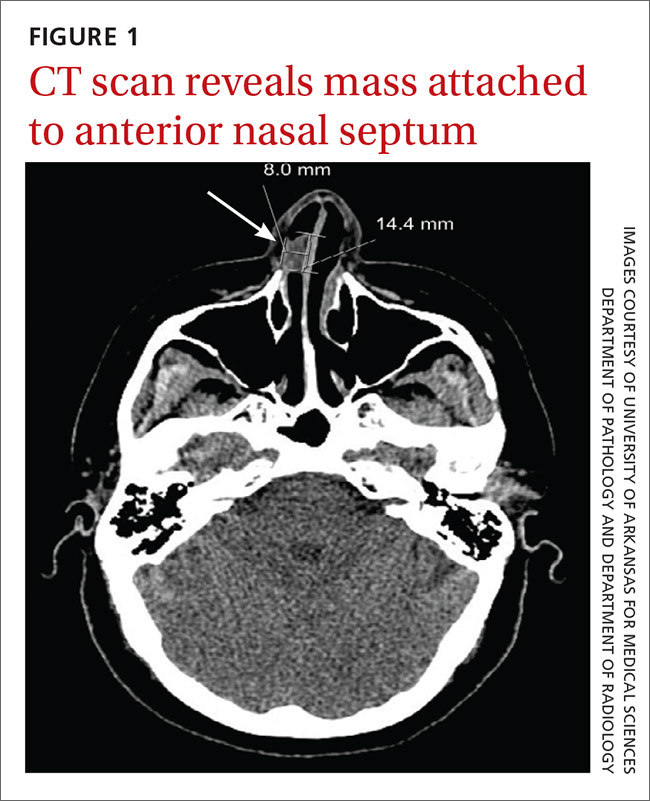

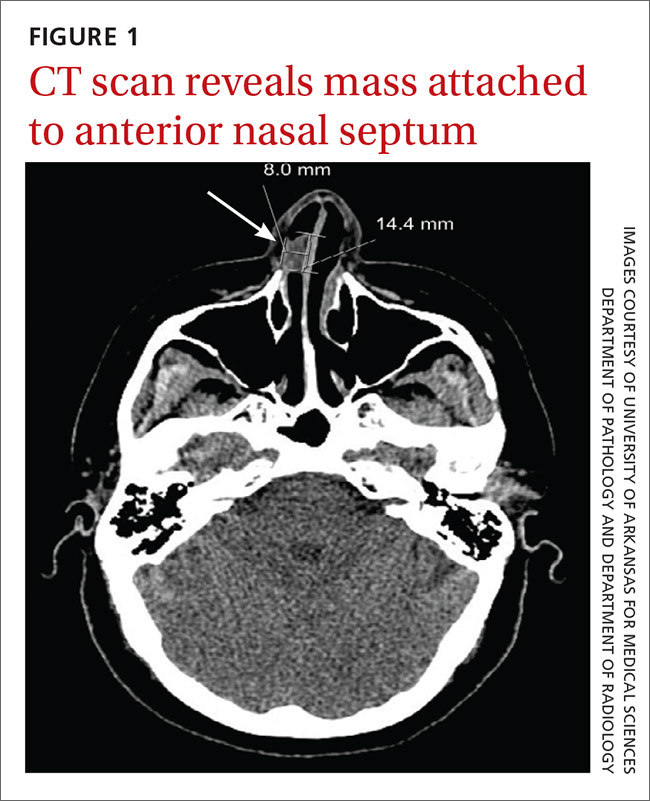

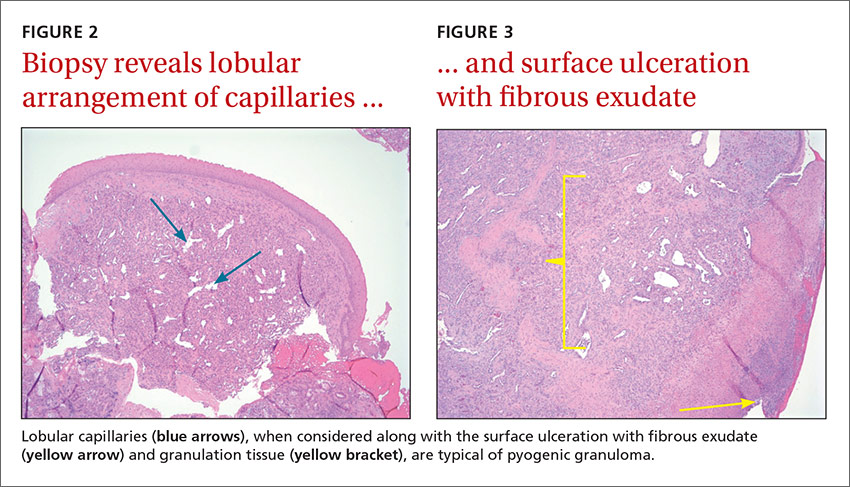

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old woman visited our family medicine clinic because she’d had 3 episodes of epistaxis during the previous month. She’d already visited the emergency department, and the doctor there had treated her symptomatically and referred her to our clinic.

On physical examination, we noted a whitish mass in the patient’s right nostril that was attached to the nasal septum. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. She had a history of hypertension, depression, anxiety, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Her medications included amlodipine-benazepril, atenolol-chlorthalidone, citalopram, clonazepam, prazosin, and omeprazole. The patient lived alone and denied using tobacco or illicit drugs, but she drank one to 2 glasses of brandy every day. She denied any past medical or family history of similar complaints, autoimmune disorders, or skin rashes.

A complete blood count, international normalized ratio, sedimentation rate, anti-nuclear antibody test, and an anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody panel were normal.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We referred the patient to an ear, nose, and throat doctor for a nasal endoscopy and a biopsy, which showed granulation tissue. A maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 1.44 cm x 0.8 cm polypoid soft tissue mass in the right nasal cavity adherent to the nasal septum with no posterior extension (FIGURE 1).

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) is a benign vascular tumor of the skin and mucous membranes that is not associated with an infection. Rather, it is a hyperplastic, neovascular, inflammatory response to an angiogenic stimulus. Several enhancers and inhibitors of angiogenesis have been shown to play a role in PG, including hormones, medications, and local injury. In fact, a local injury or hormonal factor is identified as a stimulus in more than half of PG patients.1

The hormone connection. Estrogen promotes production of nerve growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and transforming growth factor beta 1. Progesterone enhances inflammatory mediators as well. Although there are no direct receptors for estrogen and progesterone in the oral and nasal mucosa, some of these pro-inflammatory effects create an environment conducive to the development of PG. This is supported by several studies documenting an increased incidence of PGs with oral contraceptive use and regression of PGs after childbirth.2-4

Medication may play a role. Drug-induced PG has also been described in several studies.5,6 Offending medications include systemic and topical retinoids, capecitabine, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, cyclosporine, docetaxel, and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors.

Local injury may also be a culprit. Nasal PGs are commonly attached to the anterior septum and typically result from nasal packing, habitual picking, or nose boring.7 In this particular case, however, we were unable to identify the irritant.

The classic presentation

PG classically presents as a painless mass that spontaneously develops over days to weeks. The mass can be sessile or pedunculated, and is frequently hemorrhagic. Intranasal PG usually presents with epiphora.7 While the prevalence of intraoral PG was found to be one in 25,000 individuals3, data for nasal lesions is scarce. Most cases of PG are seen in the second and third decades of life.1,3 In children, PG is slightly more predominant in males.1,3 Mucosal lesions, however, have a higher incidence in females.1,3 Granuloma gravidarum, the term used to describe mucosal PG in pregnant females, was found in 0.2% to 5% of pregnancies.2,3,8

Differential Dx includes warts, squamous cell carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of PG includes Spitz nevus, glomus tumors, common warts, amelanotic melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, infantile hemangioma, and angiolymphoid hyperplasia, among others.3,5 Foreign bodies, nasal polyps, angiofibroma, meningocele, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered.

Radiologic evaluation may be beneficial—especially with nasal lesions—when looking for findings suggestive of malignancy. Both CT and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast identify PG as a soft tissue mass with lobulated contours,9,10 but histopathologic analysis is required to confirm the diagnosis. The histopathologic appearance of PG is characterized by a polypoid lesion with circumscribed anastomosing networks of capillaries arranged in one or more lobules at the base in an edematous and fibroblastic stroma.

Treatment is determined by the location and size of the lesion

The most suitable treatment is determined by considering the location of the lesion, the characteristics of the lesion (morphology/size), its amenability to surgery, risk of scar formation, and the presence or absence of a causative irritant. Excision is often preferred because it yields a specimen for pathologic analysis. Alternative treatments include electrocautery, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and intralesional and topical agents,3,6,7 but the recurrence rate is higher (up to 15%) with some of these modalities, when compared with excision (3.6%).3

Our patient underwent excision of the mass and was seen for an annual follow-up appointment. All of her symptoms resolved and no recurrence was noted.

THE TAKEAWAY

Although PG is a common and benign condition, it is rarely seen in the nasal cavity without an obvious history of a possible irritant. PG should be considered as a diagnosis for rapidly growing cutaneous or mucosal hemorrhagic lesions. Appropriate tissue pathology is essential to rule out malignancy and other serious conditions, such as bacillary angiomatosis and Wegener’s granulomatosis.

Treatment is usually required to avoid the frequent complications of ulceration and bleeding. Surgical treatments are preferred. The location of the lesion largely determines whether referral to a specialist is necessary.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.

1. Harris MN, Desai R, Chuang TY, et al. Lobular capillary hemangiomas: An epidemiologic report, with emphasis on cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1012-1016.

2. Yuan K, Jin YT, Lin MT. The detection and comparison of angiogenesis-associated factors in pyogenic granuloma by immunohistochemistry. J Periodontol. 2000;71:701-709.

3. Giblin AV, Clover AJ, Athanassopoulos A, et al. Pyogenic granuloma–the quest for optimum treatment: audit of treatment of 408 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1030-1035.

4. Steelman R, Holmes D. Pregnancy tumor in a 16-year-old: case report and treatment considerations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1992;16:217-218.

5. Jafarzadeh H, Sanatkhani M, Mohtasham N. Oral pyogenic granuloma: a review. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:167-175.

6. Piraccini BM, Bellavista S, Misciali C, et al. Periungual and subungual pyogenic granuloma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:941-953.

7. Ozcan C, Apa DD, Görür K. Pediatric lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:449-451.

8. Henry F, Quatresooz P, Valverde-Lopez JC, et al. Blood vessel changes during pregnancy: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:65-69.

9. Puxeddu R, Berlucchi M, Ledda GP, et al. Lobular capillary hemangioma of the nasal cavity: A retrospective study on 40 patients. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:480-484.

10. Maroldi R, Berlucchi M, Farina D, et al. Benign neoplasms and tumor-like lesions. In: Maroldi R, Nicolai P, eds. Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:107-158.