User login

Hints of altered microRNA expression in women exposed to EDCs

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

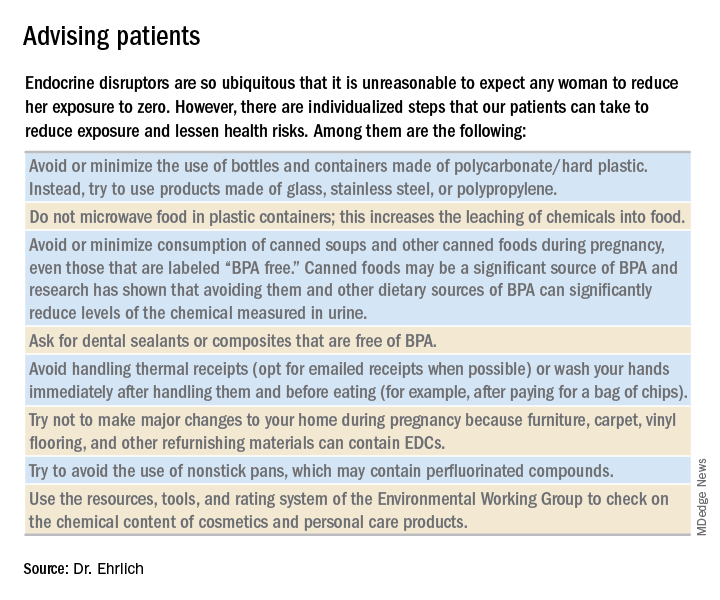

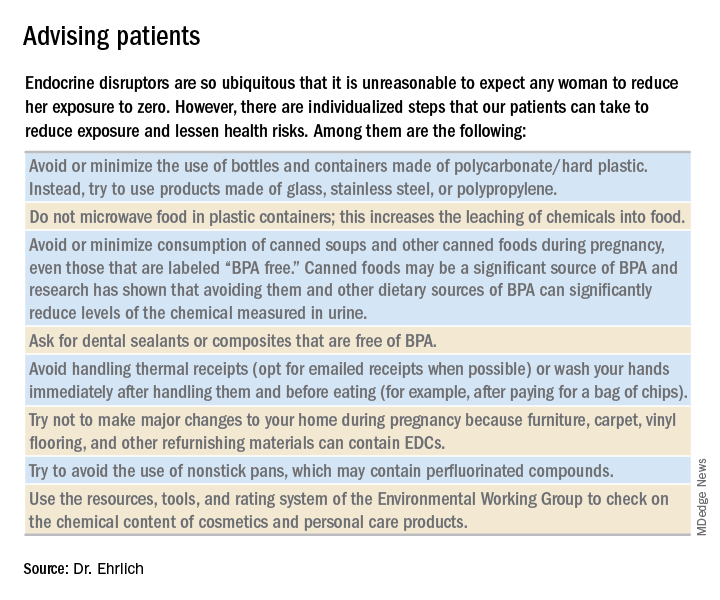

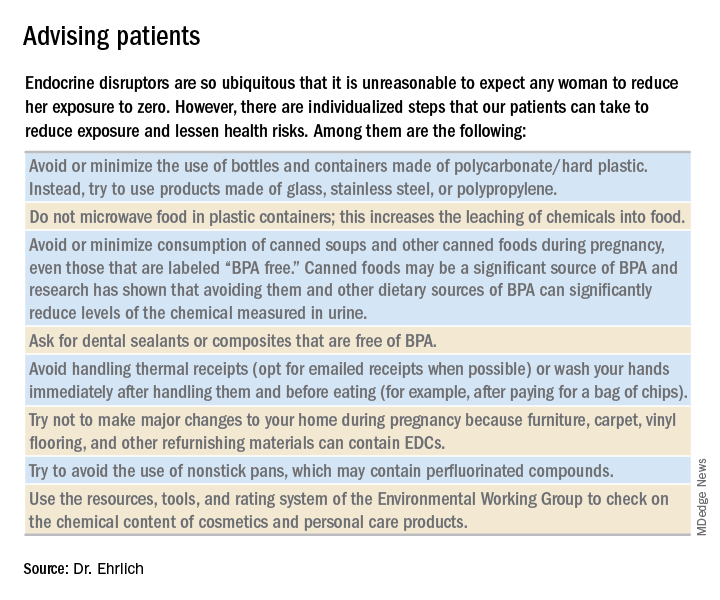

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

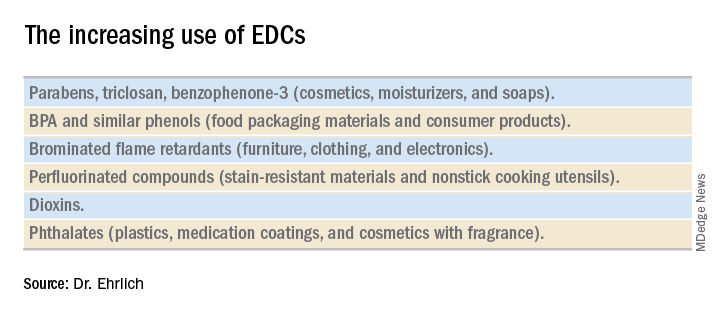

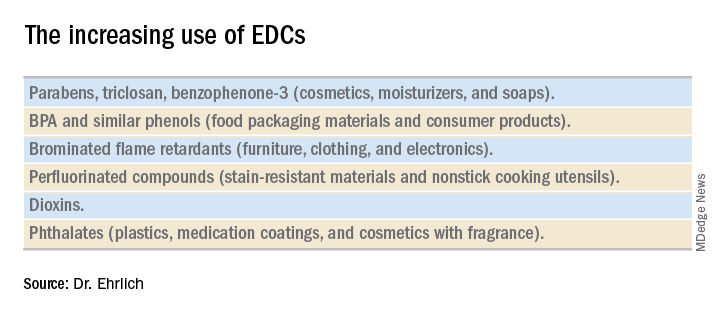

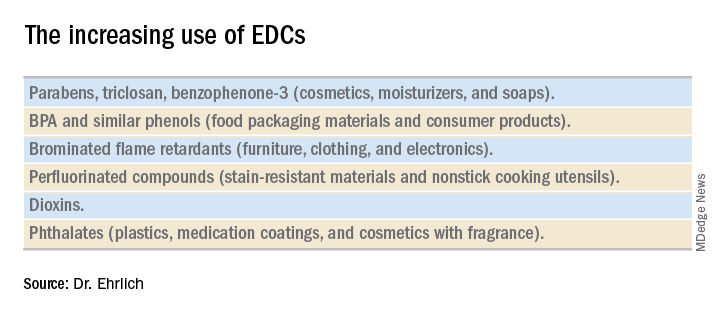

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally similar to endogenous hormones and are therefore capable of mimicking these natural hormones, interfering with their biosynthesis, transport, binding action, and/or elimination. In animal studies and human clinical observational and epidemiologic studies of various EDCs, these chemicals have consistently been associated with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hormone-sensitive cancers, neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed prenatally, and reproductive health.

In 2009, the Endocrine Society published a scientific statement in which it called EDCs a significant concern to human health (Endocr Rev. 2009;30[4]:293-342). Several years later, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine issued a Committee Opinion on Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents, warning that patient exposure to EDCs and other toxic environmental agents can have a “profound and lasting effect” on reproductive health outcomes across the life course and calling the reduction of exposure a “critical area of intervention” for ob.gyns. and other reproductive health care professionals (Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122[4]:931-5).

Despite strong calls by each of these organizations to not overlook EDCs in the clinical arena, as well as emerging evidence that EDCs may be a risk factor for gestational diabetes (GDM), EDC exposure may not be on the practicing ob.gyn.’s radar. Clinicians should know what these chemicals are and how to talk about them in preconception and prenatal visits. We should carefully consider their known – and potential – risks, and encourage our patients to identify and reduce exposure without being alarmist.

Low-dose effects

EDCs are used in the manufacture of pesticides, industrial chemicals, plastics and plasticizers, hand sanitizers, medical equipment, dental sealants, a variety of personal care products, cosmetics, and other common consumer and household products. They’re found, for example, in sunscreens, canned foods and beverages, food-packaging materials, baby bottles, flame-retardant furniture, stain-resistant carpet, and shoes. We are all ingesting and breathing them in to some degree.

Bisphenol A (BPA), one of the most extensively studied EDCs, is found in the thermal receipt paper routinely used by gas stations, supermarkets, and other stores. In a small study we conducted at Harvard, we found that urinary BPA concentrations increased after continual handling of receipts for 2 hours without gloves but did not increase significantly when gloves were used (JAMA. 2014 Feb 26;311[8]:859-60).

Informed consumers can then affect the market through their purchasing choices, but the removal of concerning chemicals from products takes a long time, and it’s not always immediately clear that replacement chemicals are safer. For instance, the BPA in “BPA-free” water bottles and canned foods has been replaced by bisphenol S (BPS), which has a very similar molecular structure to BPA. The potential adverse health effects of these replacement chemicals are now being examined in experimental and epidemiologic studies.

Through its National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported detection rates of between 75% and 99% for different EDCs in urine samples collected from a representative sample of the U.S. population. In other human research, several EDCs have been shown to cross the placenta and have been measured in maternal blood and urine and in cord blood and amniotic fluid, as well as in placental tissue at birth.

It is interesting to note that BPA’s structure is similar to that of diethylstilbestrol (DES). BPA was first shown to have estrogenic activity in 1936 and was originally considered for use in pharmaceuticals to prevent miscarriages, spontaneous abortions, and premature labor but was put aside in favor of DES. (DES was eventually found to be carcinogenic and was taken off the market.) In the 1950s, the use of BPA was resuscitated though not in pharmaceuticals.

A better understanding about the mechanisms of action and dose-response patterns of EDCs has indicated that EDCs can act at low doses, and in many cases a nonmonotonic dose-response association has been demonstrated. This is a paradigm shift for traditional toxicology in which it is “the dose that makes the poison,” and some toxicologists have been critical of the claims of low-dose potency for EDCs.

A team of epidemiologists, toxicologists, and other scientists, including myself, critically analyzed in vitro, animal, and epidemiologic studies as part of a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences working group on BPA to determine the strength of the evidence for low-dose effects (doses lower than those tested in traditional toxicology assessments) of BPA. We found that consistent, reproducible, and often adverse low-dose effects have been demonstrated for BPA in cell lines, primary cells and tissues, laboratory animals, and human populations. We also concluded that EDCs can pose the greatest threats when exposure occurs during early development, organogenesis, and during critical postnatal periods when tissues are differentiating (Endocr Disruptors [Austin, Tex.]. 2013 Sep;1:e25078-1-13).

A potential risk factor for GDM

Quite a lot of research has been done on EDCs and the risk of type 2 diabetes. A recent meta-analysis that included 41 cross-sectional and 8 prospective studies found that serum concentrations of dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and chlorinated pesticides – and urine concentrations of BPA and phthalates – were significantly associated with type 2 diabetes risk. Comparing the highest and lowest concentration categories, the pooled relative risk was 1.45 for BPA and phthalates. EDC concentrations also were associated with indicators of impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance (J Diabetes. 2016 Jul;8[4]:516-32).

Despite the mounting evidence for an association between BPA and type 2 diabetes, and despite the fact that the increased incidence of GDM in the past 20 years has mirrored the increasing use of EDCs, there has been a dearth of research examining the possible relationship between EDCs and GDM. The effects of BPA on GDM were identified as a knowledge gap by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences after a review of the literature from 2007 to 2013 (Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Aug:122[8]:775-86).

To understand the association between EDCs and GDM and the underlying mechanistic pathway of EDCs, we are conducting research that uses a growing body of evidence that suggests that environmental toxins are involved in the control of microRNA (miRNA) expression in trophoblast cells.

MiRNA, a single-stranded, short, noncoding RNA that is involved in posttranslational gene expression, can be packaged along with other signaling molecules inside extracellular vesicles in the placenta called exosomes. These exosomes appear to be shed from the placenta into the maternal circulation as early as 6-7 weeks into pregnancy. Once released into the maternal circulation, research has shown that the exosomes can target and reprogram other cells via the transfer of noncoding miRNAs, thereby changing the gene expression in these cells.

Such an exosome-mediated signaling pathway provides us with the opportunity to isolate exosomes, sequence the miRNAs, and look at whether women who are exposed to higher levels of EDCs (as indicated in urine concentration) have a particular miRNA signature that correlates with GDM. In other words, we’re working to determine whether particular EDCs and exposure levels affect the miRNA placental profiles, and if these profiles are predictive of GDM.

Thus far, in a pilot prospective cohort study of pregnant women, we are seeing hints of altered miRNA expression in relation to GDM. We have selected study participants who are at high risk of developing GDM (for example, prepregnancy body mass index greater than 30, past pregnancy with GDM, or macrosomia) because we suspect that, in many women, EDCs are a tipping point for the development of GDM rather than a sole causative factor. In addition to understanding the impact of EDCs on GDM, it is our hope that miRNAs in maternal circulation will serve as a noninvasive biomarker for early detection of GDM development or susceptibility.

Dr. Ehrlich is an assistant professor of pediatrics and environmental health at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.