User login

Metastatic Meningioma of the Scalp

Meningiomas generally present as slow-growing, expanding intracranial lesions and are the most common benign intracranial tumor in adults.1 Rarely, meningioma exhibits malignant potential and presents as an extracranial soft-tissue mass through extension or as a primary extracranial cutaneous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis of scalp neoplasms must be broadened to include uncommon tumors such as meningioma. We present a rare case of a 68-year-old woman with scalp metastasis of meningioma 11 years after initial resection of the primary tumor.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic nodule on the left parietal scalp of 2 years’ duration. She denied any headaches, difficulty with balance, vision changes, or changes in mentation. Her medical history was remarkable for a benign meningioma removed from the right parietal scalp 11 years prior without radiation therapy, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and arthritis. The patient’s son died from a brain tumor, but the exact tumor type and age at the time of death were unknown. Her current medications included metformin, insulin glargine, aspirin, and a daily multivitamin. She denied any allergies or history of smoking.

Physical examination of the scalp revealed 4 fixed, nontender, flesh-colored nodules: 2 on the left parietal scalp measuring 3.0 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively (Figure 1A); a 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp; and a 1.6-cm sausage-shaped nodule on the right temple (Figure 1B). No positive lymph nodes were appreciated, and no additional lesions were noted. No additional atypical lesions were noted on full cutaneous examination.

A diagnostic 6-mm punch biopsy of the largest nodule was performed. Intraoperatively, there was no apparent cyst wall, but coiled, loose, stringlike, pink-yellow tissue was removed from the base of the wound before closing with sutures.

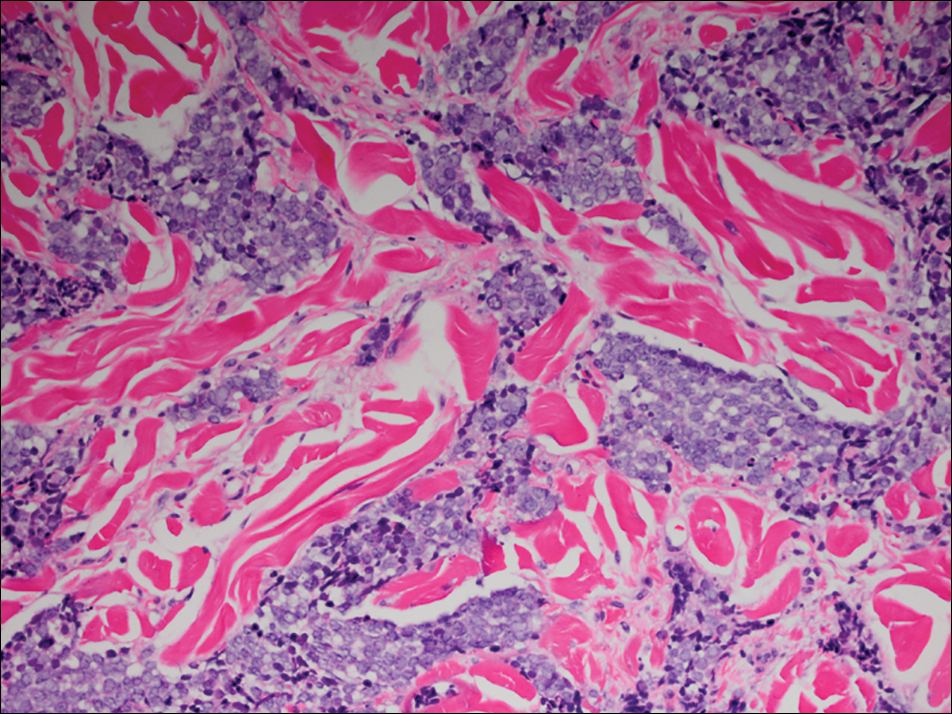

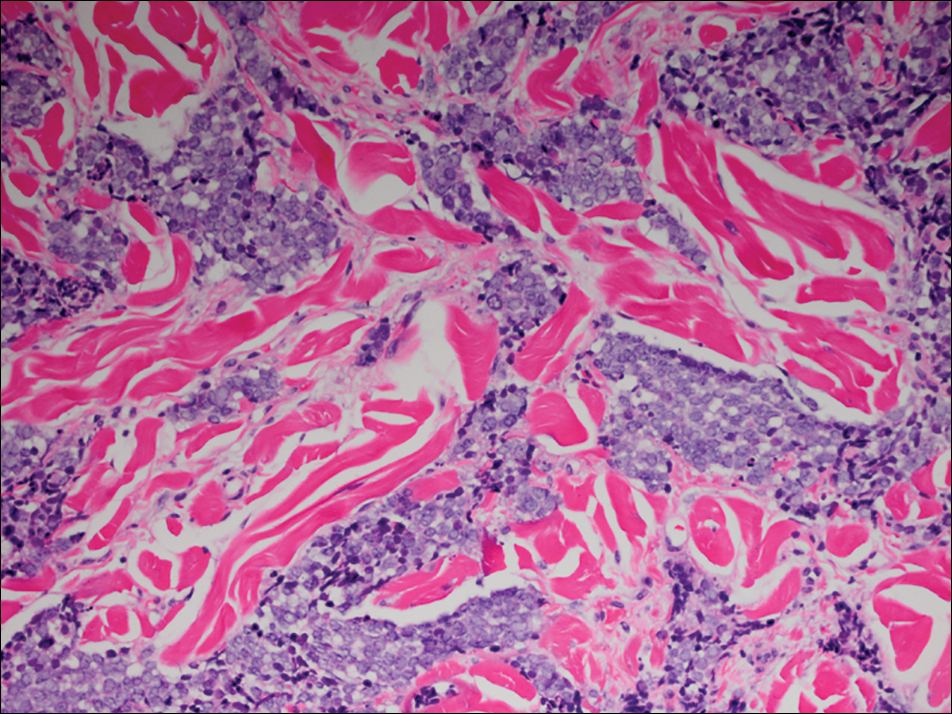

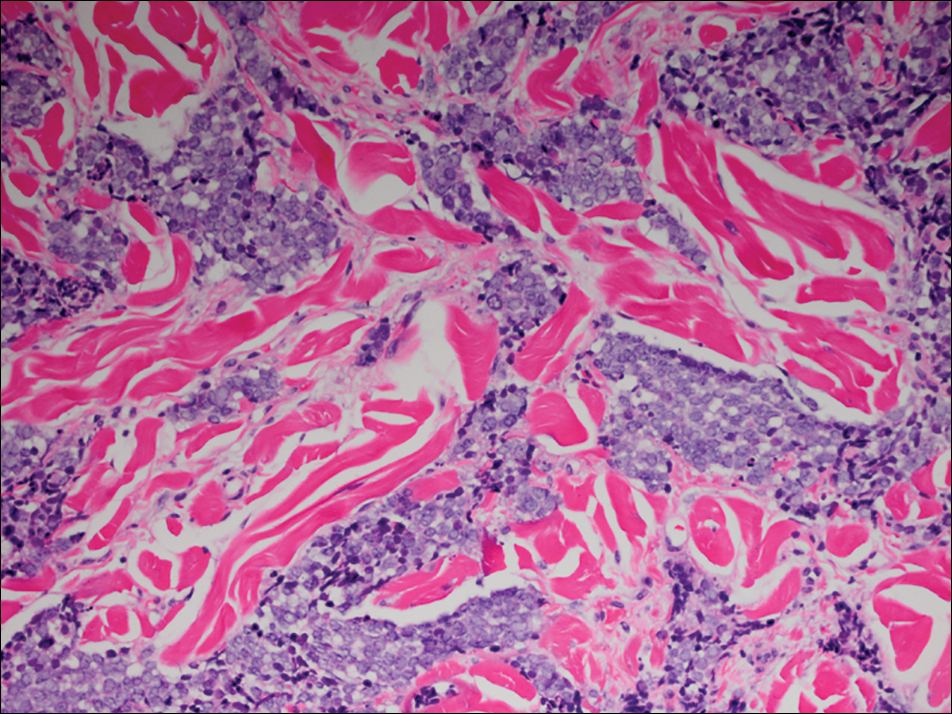

The primary histologic finding was cells within fibrous tissue containing delicate round-oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with an indistinct border (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical studies for S100 protein were focal and limited to the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells (Figure 3). Tumor cells stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and were focally positive for progesterone receptor (Figure 4). Tumor cells were negative for CD31 and CD34. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of metastatic meningioma of the scalp was made.

Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of the head, neck, and chest demonstrated 3 residual subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and an indeterminate subcentimeter nodule in the right lung. The 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp was removed without complication, and no radiation therapy was administered. The rest of the lesions were monitored. She remained under the close observation of a neurosurgeon and underwent repeat imaging of the scalp nodules and lungs, initially at 3 months and then routinely at the patient’s comfort. The patient currently denies any neurologic symptoms.

Comment

Meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells found in the leptomeninges and in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain.2 They are common intracranial neoplasms that generally are associated with a benign course and present during the fourth to sixth decades of life. Meningiomas constitute 13% to 30% of intracranial neoplasms and usually are female predominant (3:1).3,4 Rarely, malignant transformation can lead to local and distant metastasis to the lungs,5,6 liver,7 and skeletal system.8 In cases of metastatic spread, there is an increased incidence in males versus females.9-11

Risk Factors

Although many meningiomas are sporadic, numerous risk factors have been associated with the disease development. One study showed a link between exposure to ionizing radiation and subsequent development of meningioma.12 Another study found a population link between a higher incidence of meningioma and nuclear exposure in Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb blast in 1980.13 There is an increased incidence of meningioma in patients exposed to radiography from frequent dental imaging, particularly when older machines with higher levels of radiation exposure are used.14Another study demonstrated a correlation between meningioma and hormonal factors (eg, estrogen for hormone therapy) and exacerbation of symptoms during pregnancy.15 There also is an increased incidence of meningioma in breast cancer patients.4 Genetic alterations also have been implicated in the development of meningioma. It was found that 50% of patients with a mutation in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (which codes for the merlin protein) had associated meningiomas.16,17 Scalp nodules in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 increases suspicion of a scalp meningioma and necessitates biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous meningiomas typically present as firm, subcutaneous nodules. Scalp nodules ranging from alopecia18,19 to hypertrichosis20 have been reported. These neoplasms can be painless or painful, depending on mass effect and location.

Classification

The primary clinical classification system of metastatic meningioma was first described in 1974.21 Type 1 meningioma refers to congenital lesions that tend to cluster closer to the midline. Type 2 refers to ectopic soft-tissue lesions that extend to the skin from likely remnants of arachnoid cells. These lesions are more likely to be found around the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. Type 3 meningiomas extend from intracranial tumors that secondarily involve the skin through proliferation through bone or anatomic defects. Type 3 is the result of direct extension and the location of the cutaneous presentation depends on the location of the intracranial lesion.4,22,23

Pathology

Meningiomas exhibit a range of morphologic appearances on histopathology. In almost all meningiomas, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls with round-oval nuclei and delicate chromatin, central clearing, and pale pseudonuclear inclusions. Lamellate calcifications known as psammoma bodies are a common finding. Immunohistochemical studies show that most meningiomas are positive for EMA, vimentin, and progesterone receptor. S100 protein expression, if present, usually is focal.

Differential Diagnosis

Asymptomatic nodules on the scalp may present a diagnostic challenge to physicians. Most common scalp lesions tend to be cystic or lipomatous. In children, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered, including dermoid and epidermoid tumors, dermal sinus tumors, hemangiomas, metastasis of another tumor, aplasia cutis congenita, pilomatricoma, and lipoma. In adults, the differential should focus on epidermoid cysts, lipomas, metastasis of other tumors, osteomas, arteriovenous fistulae, and heterotopic brain tissue. Often, microscopic examination is necessary, along with additional immunohistochemical staining (eg, EMA, vimentin).

Treatment

Treatment options for meningioma include observation, surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, as well as a combination of these modalities. The choice of therapy depends on such variables as patient age; performance status; comorbidities; presence or absence of symptoms (including focal neurologic deficits); and tumor location, size, and grade. It is important to note that there is limited knowledge looking at the results of various treatment modalities, and no consensus approach has been established.

Conclusion

Our patient’s medical history was remarkable for an intracranial meningioma 11 years prior to the current presentation, and she was found to have biopsy-proven metastatic meningioma without recurrence of the initial tumor. Patients presenting with a scalp nodule warrant a thorough medical history and consideration beyond common cysts and lipomas.

- Mackay B, Bruner JM, Luna MA. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruc Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

- Bauman G, Fisher B, Schild S, et al. Meningioma, ependymoma, and other adult brain tumors. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2007:539-566.

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088-1095.

- Tworek JA, Mikhail AA, Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

- Shin MS, Holman WL, Herrera GA, et al. Extensive pulmonary metastasis of an intracranial meningioma with repeated recurrence: radiographic and pathologic features. South Med J. 1996;89:313-318.

- Ferguson JM, Flinn J. Intracranial meningioma with hepatic metastases and hypoglycaemia treated by selective hepatic arterial chemo-embolization. Australas Radiol.1995;39:97-99.

- Palmer JD, Cook PL, Ellison DW. Extracranial osseous metastases from intracranial meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:215-218.

- Glasauer FE, Yuan RH. Intracranial tumours with extracranial metastases. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:474-493.

- Shuangshoti S, Hongsaprabhas C, Netsky MG. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

- Ohta M, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, et al. MIB-1 staining index and scoring of histological features in meningioma. Cancer. 1994;74:3176-3189.

- Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, et al. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:278-299.

- Shintani T, Hayakawa N, Hoshi M, et al. High incidence of meningioma among Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors. J Rad Res. 1999;40:49-57.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, et al. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530-4537.

- Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279-282.

- Fontaine B, Rouleau GA, Seizinger BR, et al. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis 2 and related tumors (acoustic neuromas and meningioma). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:338-343.

- Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, et al. Radiation-induced changes of the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics. 1996;16:1055-1072.

- Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, et al. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373.

- Zeikus P, Robinson-Bostom L, Stopa E. Primary cutaneous meningioma in association with a sinus pericranii. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Junaid TA, Nkposong EO, Kolawole TM. Cutaneous meningiomas and an ovarian fibroma in a three-year-old girl. J Pathol. 1972;108:165-167.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningioma—a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Shuangshoti S, Boonjunwetwat D, Kaoroptham S. Association of primary intraspinal meningiomas and subcutaneous meningioma of the cervical region: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:129-134.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol. 2012;136:208-211.

Meningiomas generally present as slow-growing, expanding intracranial lesions and are the most common benign intracranial tumor in adults.1 Rarely, meningioma exhibits malignant potential and presents as an extracranial soft-tissue mass through extension or as a primary extracranial cutaneous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis of scalp neoplasms must be broadened to include uncommon tumors such as meningioma. We present a rare case of a 68-year-old woman with scalp metastasis of meningioma 11 years after initial resection of the primary tumor.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic nodule on the left parietal scalp of 2 years’ duration. She denied any headaches, difficulty with balance, vision changes, or changes in mentation. Her medical history was remarkable for a benign meningioma removed from the right parietal scalp 11 years prior without radiation therapy, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and arthritis. The patient’s son died from a brain tumor, but the exact tumor type and age at the time of death were unknown. Her current medications included metformin, insulin glargine, aspirin, and a daily multivitamin. She denied any allergies or history of smoking.

Physical examination of the scalp revealed 4 fixed, nontender, flesh-colored nodules: 2 on the left parietal scalp measuring 3.0 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively (Figure 1A); a 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp; and a 1.6-cm sausage-shaped nodule on the right temple (Figure 1B). No positive lymph nodes were appreciated, and no additional lesions were noted. No additional atypical lesions were noted on full cutaneous examination.

A diagnostic 6-mm punch biopsy of the largest nodule was performed. Intraoperatively, there was no apparent cyst wall, but coiled, loose, stringlike, pink-yellow tissue was removed from the base of the wound before closing with sutures.

The primary histologic finding was cells within fibrous tissue containing delicate round-oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with an indistinct border (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical studies for S100 protein were focal and limited to the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells (Figure 3). Tumor cells stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and were focally positive for progesterone receptor (Figure 4). Tumor cells were negative for CD31 and CD34. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of metastatic meningioma of the scalp was made.

Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of the head, neck, and chest demonstrated 3 residual subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and an indeterminate subcentimeter nodule in the right lung. The 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp was removed without complication, and no radiation therapy was administered. The rest of the lesions were monitored. She remained under the close observation of a neurosurgeon and underwent repeat imaging of the scalp nodules and lungs, initially at 3 months and then routinely at the patient’s comfort. The patient currently denies any neurologic symptoms.

Comment

Meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells found in the leptomeninges and in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain.2 They are common intracranial neoplasms that generally are associated with a benign course and present during the fourth to sixth decades of life. Meningiomas constitute 13% to 30% of intracranial neoplasms and usually are female predominant (3:1).3,4 Rarely, malignant transformation can lead to local and distant metastasis to the lungs,5,6 liver,7 and skeletal system.8 In cases of metastatic spread, there is an increased incidence in males versus females.9-11

Risk Factors

Although many meningiomas are sporadic, numerous risk factors have been associated with the disease development. One study showed a link between exposure to ionizing radiation and subsequent development of meningioma.12 Another study found a population link between a higher incidence of meningioma and nuclear exposure in Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb blast in 1980.13 There is an increased incidence of meningioma in patients exposed to radiography from frequent dental imaging, particularly when older machines with higher levels of radiation exposure are used.14Another study demonstrated a correlation between meningioma and hormonal factors (eg, estrogen for hormone therapy) and exacerbation of symptoms during pregnancy.15 There also is an increased incidence of meningioma in breast cancer patients.4 Genetic alterations also have been implicated in the development of meningioma. It was found that 50% of patients with a mutation in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (which codes for the merlin protein) had associated meningiomas.16,17 Scalp nodules in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 increases suspicion of a scalp meningioma and necessitates biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous meningiomas typically present as firm, subcutaneous nodules. Scalp nodules ranging from alopecia18,19 to hypertrichosis20 have been reported. These neoplasms can be painless or painful, depending on mass effect and location.

Classification

The primary clinical classification system of metastatic meningioma was first described in 1974.21 Type 1 meningioma refers to congenital lesions that tend to cluster closer to the midline. Type 2 refers to ectopic soft-tissue lesions that extend to the skin from likely remnants of arachnoid cells. These lesions are more likely to be found around the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. Type 3 meningiomas extend from intracranial tumors that secondarily involve the skin through proliferation through bone or anatomic defects. Type 3 is the result of direct extension and the location of the cutaneous presentation depends on the location of the intracranial lesion.4,22,23

Pathology

Meningiomas exhibit a range of morphologic appearances on histopathology. In almost all meningiomas, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls with round-oval nuclei and delicate chromatin, central clearing, and pale pseudonuclear inclusions. Lamellate calcifications known as psammoma bodies are a common finding. Immunohistochemical studies show that most meningiomas are positive for EMA, vimentin, and progesterone receptor. S100 protein expression, if present, usually is focal.

Differential Diagnosis

Asymptomatic nodules on the scalp may present a diagnostic challenge to physicians. Most common scalp lesions tend to be cystic or lipomatous. In children, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered, including dermoid and epidermoid tumors, dermal sinus tumors, hemangiomas, metastasis of another tumor, aplasia cutis congenita, pilomatricoma, and lipoma. In adults, the differential should focus on epidermoid cysts, lipomas, metastasis of other tumors, osteomas, arteriovenous fistulae, and heterotopic brain tissue. Often, microscopic examination is necessary, along with additional immunohistochemical staining (eg, EMA, vimentin).

Treatment

Treatment options for meningioma include observation, surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, as well as a combination of these modalities. The choice of therapy depends on such variables as patient age; performance status; comorbidities; presence or absence of symptoms (including focal neurologic deficits); and tumor location, size, and grade. It is important to note that there is limited knowledge looking at the results of various treatment modalities, and no consensus approach has been established.

Conclusion

Our patient’s medical history was remarkable for an intracranial meningioma 11 years prior to the current presentation, and she was found to have biopsy-proven metastatic meningioma without recurrence of the initial tumor. Patients presenting with a scalp nodule warrant a thorough medical history and consideration beyond common cysts and lipomas.

Meningiomas generally present as slow-growing, expanding intracranial lesions and are the most common benign intracranial tumor in adults.1 Rarely, meningioma exhibits malignant potential and presents as an extracranial soft-tissue mass through extension or as a primary extracranial cutaneous neoplasm. The differential diagnosis of scalp neoplasms must be broadened to include uncommon tumors such as meningioma. We present a rare case of a 68-year-old woman with scalp metastasis of meningioma 11 years after initial resection of the primary tumor.

Case Report

A 68-year-old woman presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic nodule on the left parietal scalp of 2 years’ duration. She denied any headaches, difficulty with balance, vision changes, or changes in mentation. Her medical history was remarkable for a benign meningioma removed from the right parietal scalp 11 years prior without radiation therapy, as well as type 2 diabetes mellitus and arthritis. The patient’s son died from a brain tumor, but the exact tumor type and age at the time of death were unknown. Her current medications included metformin, insulin glargine, aspirin, and a daily multivitamin. She denied any allergies or history of smoking.

Physical examination of the scalp revealed 4 fixed, nontender, flesh-colored nodules: 2 on the left parietal scalp measuring 3.0 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively (Figure 1A); a 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp; and a 1.6-cm sausage-shaped nodule on the right temple (Figure 1B). No positive lymph nodes were appreciated, and no additional lesions were noted. No additional atypical lesions were noted on full cutaneous examination.

A diagnostic 6-mm punch biopsy of the largest nodule was performed. Intraoperatively, there was no apparent cyst wall, but coiled, loose, stringlike, pink-yellow tissue was removed from the base of the wound before closing with sutures.

The primary histologic finding was cells within fibrous tissue containing delicate round-oval nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm with an indistinct border (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical studies for S100 protein were focal and limited to the cytoplasm of a subset of neoplastic cells (Figure 3). Tumor cells stained positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and were focally positive for progesterone receptor (Figure 4). Tumor cells were negative for CD31 and CD34. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a diagnosis of metastatic meningioma of the scalp was made.

Magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of the head, neck, and chest demonstrated 3 residual subcutaneous nodules on the scalp and an indeterminate subcentimeter nodule in the right lung. The 0.4-cm nodule on the right posterior occipital scalp was removed without complication, and no radiation therapy was administered. The rest of the lesions were monitored. She remained under the close observation of a neurosurgeon and underwent repeat imaging of the scalp nodules and lungs, initially at 3 months and then routinely at the patient’s comfort. The patient currently denies any neurologic symptoms.

Comment

Meningiomas are derived from meningothelial cells found in the leptomeninges and in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain.2 They are common intracranial neoplasms that generally are associated with a benign course and present during the fourth to sixth decades of life. Meningiomas constitute 13% to 30% of intracranial neoplasms and usually are female predominant (3:1).3,4 Rarely, malignant transformation can lead to local and distant metastasis to the lungs,5,6 liver,7 and skeletal system.8 In cases of metastatic spread, there is an increased incidence in males versus females.9-11

Risk Factors

Although many meningiomas are sporadic, numerous risk factors have been associated with the disease development. One study showed a link between exposure to ionizing radiation and subsequent development of meningioma.12 Another study found a population link between a higher incidence of meningioma and nuclear exposure in Hiroshima, Japan, after the atomic bomb blast in 1980.13 There is an increased incidence of meningioma in patients exposed to radiography from frequent dental imaging, particularly when older machines with higher levels of radiation exposure are used.14Another study demonstrated a correlation between meningioma and hormonal factors (eg, estrogen for hormone therapy) and exacerbation of symptoms during pregnancy.15 There also is an increased incidence of meningioma in breast cancer patients.4 Genetic alterations also have been implicated in the development of meningioma. It was found that 50% of patients with a mutation in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (which codes for the merlin protein) had associated meningiomas.16,17 Scalp nodules in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 increases suspicion of a scalp meningioma and necessitates biopsy.

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous meningiomas typically present as firm, subcutaneous nodules. Scalp nodules ranging from alopecia18,19 to hypertrichosis20 have been reported. These neoplasms can be painless or painful, depending on mass effect and location.

Classification

The primary clinical classification system of metastatic meningioma was first described in 1974.21 Type 1 meningioma refers to congenital lesions that tend to cluster closer to the midline. Type 2 refers to ectopic soft-tissue lesions that extend to the skin from likely remnants of arachnoid cells. These lesions are more likely to be found around the eyes, ears, nose, and mouth. Type 3 meningiomas extend from intracranial tumors that secondarily involve the skin through proliferation through bone or anatomic defects. Type 3 is the result of direct extension and the location of the cutaneous presentation depends on the location of the intracranial lesion.4,22,23

Pathology

Meningiomas exhibit a range of morphologic appearances on histopathology. In almost all meningiomas, tumor cells are concentrically wrapped in tight whorls with round-oval nuclei and delicate chromatin, central clearing, and pale pseudonuclear inclusions. Lamellate calcifications known as psammoma bodies are a common finding. Immunohistochemical studies show that most meningiomas are positive for EMA, vimentin, and progesterone receptor. S100 protein expression, if present, usually is focal.

Differential Diagnosis

Asymptomatic nodules on the scalp may present a diagnostic challenge to physicians. Most common scalp lesions tend to be cystic or lipomatous. In children, a broad differential diagnosis should be considered, including dermoid and epidermoid tumors, dermal sinus tumors, hemangiomas, metastasis of another tumor, aplasia cutis congenita, pilomatricoma, and lipoma. In adults, the differential should focus on epidermoid cysts, lipomas, metastasis of other tumors, osteomas, arteriovenous fistulae, and heterotopic brain tissue. Often, microscopic examination is necessary, along with additional immunohistochemical staining (eg, EMA, vimentin).

Treatment

Treatment options for meningioma include observation, surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, as well as a combination of these modalities. The choice of therapy depends on such variables as patient age; performance status; comorbidities; presence or absence of symptoms (including focal neurologic deficits); and tumor location, size, and grade. It is important to note that there is limited knowledge looking at the results of various treatment modalities, and no consensus approach has been established.

Conclusion

Our patient’s medical history was remarkable for an intracranial meningioma 11 years prior to the current presentation, and she was found to have biopsy-proven metastatic meningioma without recurrence of the initial tumor. Patients presenting with a scalp nodule warrant a thorough medical history and consideration beyond common cysts and lipomas.

- Mackay B, Bruner JM, Luna MA. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruc Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

- Bauman G, Fisher B, Schild S, et al. Meningioma, ependymoma, and other adult brain tumors. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2007:539-566.

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088-1095.

- Tworek JA, Mikhail AA, Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

- Shin MS, Holman WL, Herrera GA, et al. Extensive pulmonary metastasis of an intracranial meningioma with repeated recurrence: radiographic and pathologic features. South Med J. 1996;89:313-318.

- Ferguson JM, Flinn J. Intracranial meningioma with hepatic metastases and hypoglycaemia treated by selective hepatic arterial chemo-embolization. Australas Radiol.1995;39:97-99.

- Palmer JD, Cook PL, Ellison DW. Extracranial osseous metastases from intracranial meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:215-218.

- Glasauer FE, Yuan RH. Intracranial tumours with extracranial metastases. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:474-493.

- Shuangshoti S, Hongsaprabhas C, Netsky MG. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

- Ohta M, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, et al. MIB-1 staining index and scoring of histological features in meningioma. Cancer. 1994;74:3176-3189.

- Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, et al. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:278-299.

- Shintani T, Hayakawa N, Hoshi M, et al. High incidence of meningioma among Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors. J Rad Res. 1999;40:49-57.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, et al. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530-4537.

- Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279-282.

- Fontaine B, Rouleau GA, Seizinger BR, et al. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis 2 and related tumors (acoustic neuromas and meningioma). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:338-343.

- Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, et al. Radiation-induced changes of the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics. 1996;16:1055-1072.

- Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, et al. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373.

- Zeikus P, Robinson-Bostom L, Stopa E. Primary cutaneous meningioma in association with a sinus pericranii. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Junaid TA, Nkposong EO, Kolawole TM. Cutaneous meningiomas and an ovarian fibroma in a three-year-old girl. J Pathol. 1972;108:165-167.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningioma—a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Shuangshoti S, Boonjunwetwat D, Kaoroptham S. Association of primary intraspinal meningiomas and subcutaneous meningioma of the cervical region: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:129-134.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol. 2012;136:208-211.

- Mackay B, Bruner JM, Luna MA. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruc Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

- Whittle IR, Smith C, Navoo P, et al. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

- Bauman G, Fisher B, Schild S, et al. Meningioma, ependymoma, and other adult brain tumors. In: Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds. Clinical Radiation Oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2007:539-566.

- Claus EB, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:1088-1095.

- Tworek JA, Mikhail AA, Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

- Shin MS, Holman WL, Herrera GA, et al. Extensive pulmonary metastasis of an intracranial meningioma with repeated recurrence: radiographic and pathologic features. South Med J. 1996;89:313-318.

- Ferguson JM, Flinn J. Intracranial meningioma with hepatic metastases and hypoglycaemia treated by selective hepatic arterial chemo-embolization. Australas Radiol.1995;39:97-99.

- Palmer JD, Cook PL, Ellison DW. Extracranial osseous metastases from intracranial meningioma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:215-218.

- Glasauer FE, Yuan RH. Intracranial tumours with extracranial metastases. case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:474-493.

- Shuangshoti S, Hongsaprabhas C, Netsky MG. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

- Ohta M, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, et al. MIB-1 staining index and scoring of histological features in meningioma. Cancer. 1994;74:3176-3189.

- Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, et al. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4:278-299.

- Shintani T, Hayakawa N, Hoshi M, et al. High incidence of meningioma among Hiroshima atomic bomb survivors. J Rad Res. 1999;40:49-57.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, et al. Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma. Cancer. 2012;118:4530-4537.

- Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:279-282.

- Fontaine B, Rouleau GA, Seizinger BR, et al. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis 2 and related tumors (acoustic neuromas and meningioma). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:338-343.

- Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, et al. Radiation-induced changes of the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics. 1996;16:1055-1072.

- Tanaka S, Okazaki M, Egusa G, et al. A case of pheochromocytoma associated with meningioma. J Intern Med. 1991;229:371-373.

- Zeikus P, Robinson-Bostom L, Stopa E. Primary cutaneous meningioma in association with a sinus pericranii. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S49-S50.

- Junaid TA, Nkposong EO, Kolawole TM. Cutaneous meningiomas and an ovarian fibroma in a three-year-old girl. J Pathol. 1972;108:165-167.

- Lopez DA, Silvers DN, Helwig EB. Cutaneous meningioma—a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1974;34:728-744.

- Shuangshoti S, Boonjunwetwat D, Kaoroptham S. Association of primary intraspinal meningiomas and subcutaneous meningioma of the cervical region: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:129-134.

- Miedema JR, Zedek D. Cutaneous meningioma. Arch Pathol. 2012;136:208-211.

Aggressive Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Liver Transplant Recipient

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor derived from the nerve-associated Merkel cell touch receptors.1 It typically presents as a solitary, rapidly growing, red to violaceous, asymptomatic nodule, though ulcerated, acneform, and cystic lesions also have been described.2 Merkel cell carcinoma follows an aggressive clinical course with a tendency for rapid growth, local recurrence (26%–60% of cases), lymph node invasion, and distant metastases (18%–52% of cases).3

Several risk factors contribute to the development of MCC, including chronic immunosuppression, exposure to UV radiation, and infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Immunosuppression has been shown to increase the risk for MCC and is associated with a worse prognosis independent of stage at diagnosis.4 Organ transplant recipients represent a subset of immunosuppressed patients who are at increased risk for the development of MCC. We report a case of metastatic MCC in a 67-year-old woman 6 years after liver transplantation.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman presented to our clinic with 2 masses—1 on the left buttock and 1 on the left hip—of 4 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation 6 years prior as well as hypertension and thyroid disorder. Her posttransplantation course was unremarkable, and she was maintained on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Six years after transplantation, the patient was observed to have a 4-cm, red-violaceous, painless, dome-shaped tumor on the left buttock (Figure 1). She also was noted to have pink-red papulonodules forming a painless 8-cm plaque on the left hip that was present for 2 weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Both lesions were subsequently biopsied.

Microscopic examination of both lesions was consistent with the diagnosis of MCC. On histopathology, both samples exhibited a dense cellular dermis composed of atypical basophilic tumor cells with extension into superficial dilated lymphatic channels indicating lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). Tumor cells were positive for the immunohistochemical markers pankeratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and Merkel cell polyomavirus.

Total-body computed tomography and positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lobular density in the left gluteal region measuring 3.9×1.1 cm. The mass was associated with avid disease involving the left inguinal, bilateral iliac chain, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The patient was determined to have stage IV MCC based on the presence of distant lymph node metastases. The mass on the left hip was identified as an in-transit metastasis from the primary tumor on the left buttock.

The patient was referred to surgical and medical oncology. The decision was made to start palliative chemotherapy without surgical intervention given the extent of metastases not amenable for resection. The patient was subsequently initiated on chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. After one cycle of chemotherapy, both tumors initially decreased in size; however, 4 months later, despite multiple cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was noted to have growth of existing tumors and interval development of a new 7×5-cm erythematous plaque in the left groin (Figure 3A) and a 1.1×1.0-cm smooth nodule on the right upper back (Figure 3B), both also found to be consistent with distant skin metastases of MCC upon microscopic examination after biopsy. Despite chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor continued to spread and the patient died within 8 months of diagnosis.

Comment

Transplant recipients represent a well-described cohort of immunosuppressed patients prone to the development of MCC. Merkel cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients has been most frequently documented to occur after kidney transplantation and less frequently after heart and liver transplantations.5,6 However, the role of organ type and immunosuppressive regimen is not well characterized in the literature. Clarke et al7 investigated the risk for MCC in a large cohort of solid organ transplant recipients based on specific immunosuppression medications. They found a higher risk for MCC in patients who were maintained on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors rather than tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids. In comparison to combination tacrolimus–mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine-azathioprine was associated with an increased incidence of MCC; this risk rose remarkably in patients who resided in geographic locations with a higher average of UV exposure. The authors suggested that UV radiation and immunosuppression-induced DNA damage may be synergistic in the development of MCC.7

Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently occurs on sun-exposed sites, including the face, head, and neck (55%); upper and lower extremities (40%); and truncal regions (5%).8 However, case reports highlight MCC arising in atypical locations such as the buttocks and gluteal region in organ transplant recipients.7,9 In the general population, MCC predominantly arises in elderly patients (ie, >70 years), but it is more likely to present at an earlier age in transplant recipients.6,10 In a retrospective analysis of 41 solid organ transplant recipients, 12 were diagnosed before the age of 50 years.6 Data from the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients showed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, with the highest incidence occurring 10 or more years after transplantation.7

Merkel cell carcinoma behaves aggressively and is the most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.11 Organ transplant recipients with MCC have a worse prognosis than MCC patients who are not transplant recipients. In a retrospective registry analysis of 45 de novo cases, Buell at al5 found a 60% mortality rate in transplant recipients, almost double the 33% mortality rate of the general population. Furthermore, Arron et al10 revealed substantially increased rates of disease progression and decreased rates of disease-specific and overall survival in solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppression compared to immunocompetent controls. The most important factor for poor prognosis is the presence of lymph node invasion, which lowers survival rate.12

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma following liver transplantation is not well described in the literature. We highlight a case of an aggressive MCC arising in a sun-protected site with rapid metastasis 6 years after liver transplantation. This case emphasizes the importance of surveillance for cutaneous malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients.

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest. 1985;52:334-353.

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):143-156.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489-1495.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642-646.

- Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1780-1781.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. pii:dju382. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382.

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis and clinical management [published online July 13, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

- Krejčí K, Tichý T, Horák P, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation [published online September 20, 2010]. Onkologie. 2010;33:520-524.

- Arron ST, Canavan T, Yu SS. Organ transplant recipients with Merkel cell carcinoma have reduced progression-free, overall, and disease-specific survival independent of stage at presentation [published online July 1, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:684-690.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population-based study [published online July 23, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. Treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:510-515.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor derived from the nerve-associated Merkel cell touch receptors.1 It typically presents as a solitary, rapidly growing, red to violaceous, asymptomatic nodule, though ulcerated, acneform, and cystic lesions also have been described.2 Merkel cell carcinoma follows an aggressive clinical course with a tendency for rapid growth, local recurrence (26%–60% of cases), lymph node invasion, and distant metastases (18%–52% of cases).3

Several risk factors contribute to the development of MCC, including chronic immunosuppression, exposure to UV radiation, and infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Immunosuppression has been shown to increase the risk for MCC and is associated with a worse prognosis independent of stage at diagnosis.4 Organ transplant recipients represent a subset of immunosuppressed patients who are at increased risk for the development of MCC. We report a case of metastatic MCC in a 67-year-old woman 6 years after liver transplantation.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman presented to our clinic with 2 masses—1 on the left buttock and 1 on the left hip—of 4 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation 6 years prior as well as hypertension and thyroid disorder. Her posttransplantation course was unremarkable, and she was maintained on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Six years after transplantation, the patient was observed to have a 4-cm, red-violaceous, painless, dome-shaped tumor on the left buttock (Figure 1). She also was noted to have pink-red papulonodules forming a painless 8-cm plaque on the left hip that was present for 2 weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Both lesions were subsequently biopsied.

Microscopic examination of both lesions was consistent with the diagnosis of MCC. On histopathology, both samples exhibited a dense cellular dermis composed of atypical basophilic tumor cells with extension into superficial dilated lymphatic channels indicating lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). Tumor cells were positive for the immunohistochemical markers pankeratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and Merkel cell polyomavirus.

Total-body computed tomography and positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lobular density in the left gluteal region measuring 3.9×1.1 cm. The mass was associated with avid disease involving the left inguinal, bilateral iliac chain, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The patient was determined to have stage IV MCC based on the presence of distant lymph node metastases. The mass on the left hip was identified as an in-transit metastasis from the primary tumor on the left buttock.

The patient was referred to surgical and medical oncology. The decision was made to start palliative chemotherapy without surgical intervention given the extent of metastases not amenable for resection. The patient was subsequently initiated on chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. After one cycle of chemotherapy, both tumors initially decreased in size; however, 4 months later, despite multiple cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was noted to have growth of existing tumors and interval development of a new 7×5-cm erythematous plaque in the left groin (Figure 3A) and a 1.1×1.0-cm smooth nodule on the right upper back (Figure 3B), both also found to be consistent with distant skin metastases of MCC upon microscopic examination after biopsy. Despite chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor continued to spread and the patient died within 8 months of diagnosis.

Comment

Transplant recipients represent a well-described cohort of immunosuppressed patients prone to the development of MCC. Merkel cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients has been most frequently documented to occur after kidney transplantation and less frequently after heart and liver transplantations.5,6 However, the role of organ type and immunosuppressive regimen is not well characterized in the literature. Clarke et al7 investigated the risk for MCC in a large cohort of solid organ transplant recipients based on specific immunosuppression medications. They found a higher risk for MCC in patients who were maintained on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors rather than tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids. In comparison to combination tacrolimus–mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine-azathioprine was associated with an increased incidence of MCC; this risk rose remarkably in patients who resided in geographic locations with a higher average of UV exposure. The authors suggested that UV radiation and immunosuppression-induced DNA damage may be synergistic in the development of MCC.7

Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently occurs on sun-exposed sites, including the face, head, and neck (55%); upper and lower extremities (40%); and truncal regions (5%).8 However, case reports highlight MCC arising in atypical locations such as the buttocks and gluteal region in organ transplant recipients.7,9 In the general population, MCC predominantly arises in elderly patients (ie, >70 years), but it is more likely to present at an earlier age in transplant recipients.6,10 In a retrospective analysis of 41 solid organ transplant recipients, 12 were diagnosed before the age of 50 years.6 Data from the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients showed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, with the highest incidence occurring 10 or more years after transplantation.7

Merkel cell carcinoma behaves aggressively and is the most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.11 Organ transplant recipients with MCC have a worse prognosis than MCC patients who are not transplant recipients. In a retrospective registry analysis of 45 de novo cases, Buell at al5 found a 60% mortality rate in transplant recipients, almost double the 33% mortality rate of the general population. Furthermore, Arron et al10 revealed substantially increased rates of disease progression and decreased rates of disease-specific and overall survival in solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppression compared to immunocompetent controls. The most important factor for poor prognosis is the presence of lymph node invasion, which lowers survival rate.12

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma following liver transplantation is not well described in the literature. We highlight a case of an aggressive MCC arising in a sun-protected site with rapid metastasis 6 years after liver transplantation. This case emphasizes the importance of surveillance for cutaneous malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor derived from the nerve-associated Merkel cell touch receptors.1 It typically presents as a solitary, rapidly growing, red to violaceous, asymptomatic nodule, though ulcerated, acneform, and cystic lesions also have been described.2 Merkel cell carcinoma follows an aggressive clinical course with a tendency for rapid growth, local recurrence (26%–60% of cases), lymph node invasion, and distant metastases (18%–52% of cases).3

Several risk factors contribute to the development of MCC, including chronic immunosuppression, exposure to UV radiation, and infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Immunosuppression has been shown to increase the risk for MCC and is associated with a worse prognosis independent of stage at diagnosis.4 Organ transplant recipients represent a subset of immunosuppressed patients who are at increased risk for the development of MCC. We report a case of metastatic MCC in a 67-year-old woman 6 years after liver transplantation.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman presented to our clinic with 2 masses—1 on the left buttock and 1 on the left hip—of 4 months’ duration. The patient’s medical history was remarkable for autoimmune hepatitis requiring liver transplantation 6 years prior as well as hypertension and thyroid disorder. Her posttransplantation course was unremarkable, and she was maintained on chronic immunosuppression with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Six years after transplantation, the patient was observed to have a 4-cm, red-violaceous, painless, dome-shaped tumor on the left buttock (Figure 1). She also was noted to have pink-red papulonodules forming a painless 8-cm plaque on the left hip that was present for 2 weeks prior to presentation (Figure 1). Both lesions were subsequently biopsied.

Microscopic examination of both lesions was consistent with the diagnosis of MCC. On histopathology, both samples exhibited a dense cellular dermis composed of atypical basophilic tumor cells with extension into superficial dilated lymphatic channels indicating lymphovascular invasion (Figure 2). Tumor cells were positive for the immunohistochemical markers pankeratin AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, cytokeratin 20, synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and Merkel cell polyomavirus.

Total-body computed tomography and positron emission tomography revealed a hypermetabolic lobular density in the left gluteal region measuring 3.9×1.1 cm. The mass was associated with avid disease involving the left inguinal, bilateral iliac chain, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The patient was determined to have stage IV MCC based on the presence of distant lymph node metastases. The mass on the left hip was identified as an in-transit metastasis from the primary tumor on the left buttock.

The patient was referred to surgical and medical oncology. The decision was made to start palliative chemotherapy without surgical intervention given the extent of metastases not amenable for resection. The patient was subsequently initiated on chemotherapy with etoposide and carboplatin. After one cycle of chemotherapy, both tumors initially decreased in size; however, 4 months later, despite multiple cycles of chemotherapy, the patient was noted to have growth of existing tumors and interval development of a new 7×5-cm erythematous plaque in the left groin (Figure 3A) and a 1.1×1.0-cm smooth nodule on the right upper back (Figure 3B), both also found to be consistent with distant skin metastases of MCC upon microscopic examination after biopsy. Despite chemotherapy, the patient’s tumor continued to spread and the patient died within 8 months of diagnosis.

Comment

Transplant recipients represent a well-described cohort of immunosuppressed patients prone to the development of MCC. Merkel cell carcinoma in organ transplant recipients has been most frequently documented to occur after kidney transplantation and less frequently after heart and liver transplantations.5,6 However, the role of organ type and immunosuppressive regimen is not well characterized in the literature. Clarke et al7 investigated the risk for MCC in a large cohort of solid organ transplant recipients based on specific immunosuppression medications. They found a higher risk for MCC in patients who were maintained on cyclosporine, azathioprine, and mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) inhibitors rather than tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids. In comparison to combination tacrolimus–mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine-azathioprine was associated with an increased incidence of MCC; this risk rose remarkably in patients who resided in geographic locations with a higher average of UV exposure. The authors suggested that UV radiation and immunosuppression-induced DNA damage may be synergistic in the development of MCC.7

Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently occurs on sun-exposed sites, including the face, head, and neck (55%); upper and lower extremities (40%); and truncal regions (5%).8 However, case reports highlight MCC arising in atypical locations such as the buttocks and gluteal region in organ transplant recipients.7,9 In the general population, MCC predominantly arises in elderly patients (ie, >70 years), but it is more likely to present at an earlier age in transplant recipients.6,10 In a retrospective analysis of 41 solid organ transplant recipients, 12 were diagnosed before the age of 50 years.6 Data from the US Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients showed a median age at diagnosis of 62 years, with the highest incidence occurring 10 or more years after transplantation.7

Merkel cell carcinoma behaves aggressively and is the most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.11 Organ transplant recipients with MCC have a worse prognosis than MCC patients who are not transplant recipients. In a retrospective registry analysis of 45 de novo cases, Buell at al5 found a 60% mortality rate in transplant recipients, almost double the 33% mortality rate of the general population. Furthermore, Arron et al10 revealed substantially increased rates of disease progression and decreased rates of disease-specific and overall survival in solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppression compared to immunocompetent controls. The most important factor for poor prognosis is the presence of lymph node invasion, which lowers survival rate.12

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma following liver transplantation is not well described in the literature. We highlight a case of an aggressive MCC arising in a sun-protected site with rapid metastasis 6 years after liver transplantation. This case emphasizes the importance of surveillance for cutaneous malignancy in solid organ transplant recipients.

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest. 1985;52:334-353.

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):143-156.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489-1495.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642-646.

- Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1780-1781.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. pii:dju382. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382.

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis and clinical management [published online July 13, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

- Krejčí K, Tichý T, Horák P, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation [published online September 20, 2010]. Onkologie. 2010;33:520-524.

- Arron ST, Canavan T, Yu SS. Organ transplant recipients with Merkel cell carcinoma have reduced progression-free, overall, and disease-specific survival independent of stage at presentation [published online July 1, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:684-690.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population-based study [published online July 23, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. Treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:510-515.

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al. Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest. 1985;52:334-353.

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):143-156.

- Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Economopoulos T. Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1489-1495.

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A, et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma-specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:642-646.

- Buell JF, Trofe J, Hanaway MJ, et al. Immunosuppression and Merkel cell cancer. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:1780-1781.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, et al. Risk of Merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. pii:dju382. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382.

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis and clinical management [published online July 13, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4021-4026.

- Krejčí K, Tichý T, Horák P, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the gluteal region with ipsilateral metastasis into the pancreatic graft of a patient after combined kidney-pancreas transplantation [published online September 20, 2010]. Onkologie. 2010;33:520-524.

- Arron ST, Canavan T, Yu SS. Organ transplant recipients with Merkel cell carcinoma have reduced progression-free, overall, and disease-specific survival independent of stage at presentation [published online July 1, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:684-690.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population-based study [published online July 23, 2009]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. Treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:510-515.

Practice Points

- Organ transplant recipients are at an increased risk for Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

- Early recognition and diagnosis of MCC is important to improve morbidity and mortality.