User login

Minilaparoscopy is the next step in minimally invasive surgery

Minimally invasive surgeons have been intrigued for more than 2 decades by the clinical aspects and benefits of minilaparoscopy. Miniature instruments (2-3.5 mm) were introduced starting in the late 1980s, and through the 1990s minilaparoscopic procedures were performed across multiple specialties. However, the instrumentation available at the time had limited durability and functionality (for example, a lack of electrosurgical capability), and clinical experience and resulting data were sparse. The minilaparoscopic approach failed to gain momentum and was never widely adopted.

In the past 5-10 years, with new innovations in technology and improved instrumentation, minilaparoscopy is undergoing a renaissance in surgical circles. Medical device companies have developed numerous electrosurgical and other advanced energy options as well as a variety of needle holders, graspers, and other instruments – all with diameters of 3.5 mm or less and with significantly more durability than the earlier generation of mini-instruments. While surgeons oftentimes still use larger telescopes for better visualization, 2- to 3.5-mm telescopes are available in various lengths and angles, and optic quality is continually improving.

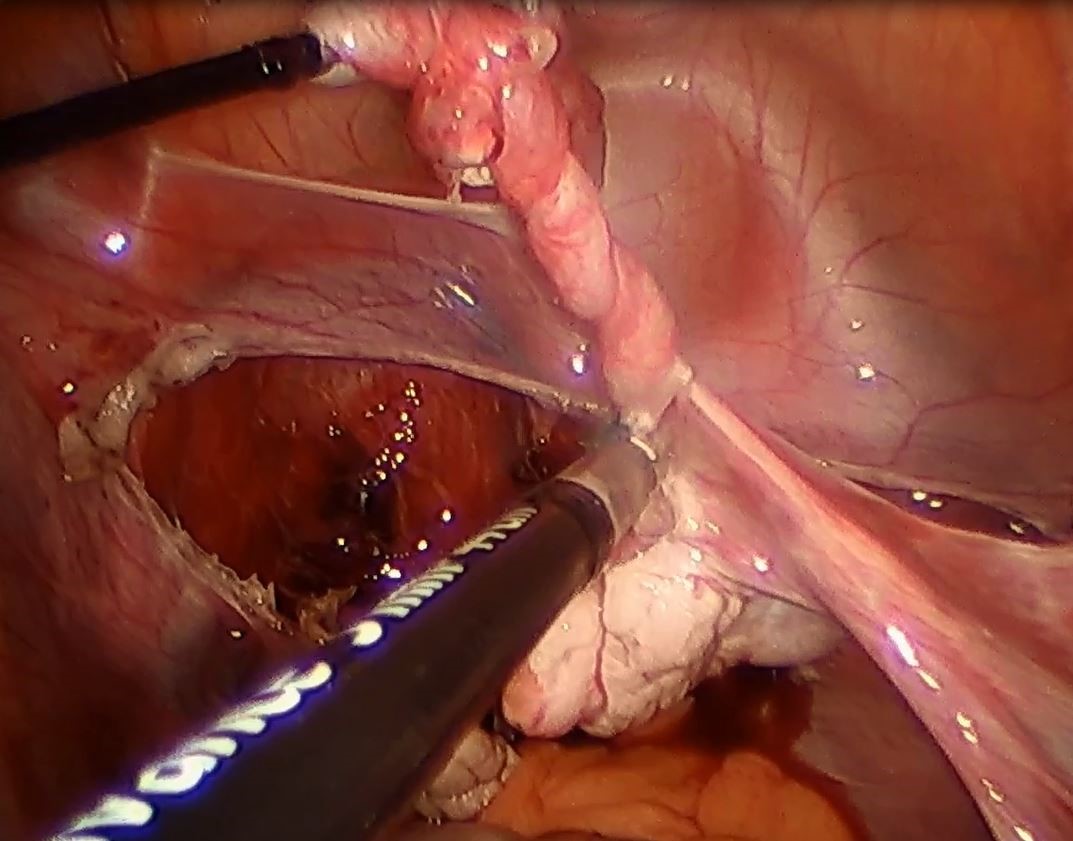

The minilaparoscopic approach is more similar to conventional laparoscopy than laparoendoscopic single-site surgery, which has not met early expectations. It is a more logical next step in the evolution of minimally invasive surgery and its goals of further reducing surgical trauma and improving cosmesis. I am performing hysterectomies in which I place two 5-mm nonbladed trocars through incisions inside the umbilicus and a minilaparoscopic percutaneous cannula below the bikini line; it is a “hybrid” procedure, in essence, that incorporates the use of mini-instrumentation.

In addition to diagnostic laparoscopy, I also use minilaparoscopy for some of my patients who need ovarian cystectomy, oophorectomy, appendectomy, treatment of early-stage endometriosis or adhesiolysis. Throughout the world and across multiple specialties, it is being adopted for a wide range of adult and pediatric procedures, from abdominopelvic adhesions and inguinal hernia repair to cholecystectomy, and even to enhance diagnosis in the ED or ICU.1

The importance of surgical scars

The resurgence of interest in minilaparoscopy has been driven largely by its clinical advantages. From a clinical standpoint, less intrusion through the abdominal wall with the use of smaller instruments and fewer insertion points generally means less surgical trauma, and less analgesic medication and postoperative pain, for instance, as well as fewer vascular injuries and a more minimal risk of adhesions. Scar cosmesis also has been viewed as an advantage, just as it was when the abdominal hysterectomy was being replaced by laparoscopic hysterectomy starting in 1989. Still, for me, the clinical aspects have long been at the forefront.

My interest in providing my patients the very best cosmetic results changed after we surveyed patients who were scheduled for a hysterectomy in my practice over the span of 1 year. All patients seen during that time (from November 2012 to November 2013) were asked to complete a questionnaire on their knowledge of hysterectomy incisional scars, their perceptions, and their desires. Almost all of the 200 women who completed the survey – 93% – indicated that cosmetic issues such as scars are important to them (“slightly,” “moderately,” “quite,” or “extremely” important), and of these, 24% chose “extremely important.”

Asked how they feel about the appearance of their scars from prior abdominal surgery, 58% indicated the appearance bothered them to some extent, and 11% said they were “extremely” bothered. Almost all of the 200 patients – 92% – said they would be interested in a surgery that would leave no scars, and 45% said they were “extremely” interested.2

The findings juxtaposed the clinical benefits of more minimally invasive surgery – what had been foremost on my mind – with patients’ attention to and concern about scars. The study demonstrated that patient preferences are just as compelling, if not more, than what the surgeon wants. It showed, moreover, how important it is to discuss hysterectomy incision options – and patient preferences regarding incision location, size, and number – prior to surgery.

When asked about their familiarity with the locations of skin incisions in different hysterectomy procedures (abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic, robotic, and mini), between 25% and 56% indicated they were not at all familiar with them. Familiarity was greatest with incisions in traditional laparoscopic hysterectomy. Yet patients want to have that knowledge: Almost all of the survey participants – 93% – indicated it is important to discuss the location, number, and size of incisions prior to surgery, and 59% said it is “extremely” important.

Patients also were asked to rank a short list of incision locations (above or below the belly button, and above or below the bikini line) from the least desirable to most desirable, and the results suggest just how different personal preferences can be. The most-desirable incision location was below the bikini line for 68% of patients, followed by above the belly button for 16%. The least-desirable location was above the belly button for 69%, followed by below the bikini line for 15%. Asked whether it is cosmetically superior for one’s incisions to be low (below the bikini line), 86% said they agreed.

Other research has similarly shown that cosmesis is important for women undergoing gynecologic surgery. For instance, women in another single-practice study were more likely to prefer single-site and traditional laparoscopic incisions over robotic ones when they were shown photos of an abdomen marked up with the incision lengths and locations typical for each of these three approaches.3 And notably, there has been research looking at the psychological impact of incisional scars specifically in patients who are morbidly obese.

While we may not be accustomed to discussing incisions and scars, it behooves us as surgeons to consider initiating a conversation about incisions with all our patients – regardless of their body mass index and prior surgical history – during the preoperative evaluation.

My hysterectomy approach

I have utilized one of the most recent developments in minilaparoscopy instrumentation – the MiniLap percutaneous surgical system (Teleflex) – to develop a mini technique for hysterectomy I’ve trademarked as the Cosmetic Hysterectomy. The percutaneous system has an outer diameter of 2.3 mm, integrated needle tips that facilitate insertion without a trocar, and a selection of integrated graspers (e.g., a miniature clutch or alligator) that open up to 12.5 mm and can be advanced and retracted through the cannula. The graspers can be locked onto the tissue, and the system itself can be stabilized extracorporeally so that it can be hands free.

For the hysterectomy, I make two 5-mm vertical incisions within the umbilicus – one for a nonbladed 5-mm trocar at 12 o’clock and the other for a second nonbladed 5-mm trocar at 6 o’clock, penetrating the fascia. The trocars house a 30-degree extra-long laparoscope with camera attached, and an advanced bipolar electrosurgery device.

The minilaparoscopic cannula is inserted in the lower-abdominal area through a single 1-mm stab incision, and one or two instruments can be placed as needed. Tissues can be removed vaginally once dissection is completed, and the vaginal cuff can be closed laparoscopically or vaginally. The edges of the minilaparoscopic cannula are approximated together and held with surgical glue or a sterile skin-closure strip. There is no need to close the fascia.4

The percutaneous system opens new windows for minimally invasive surgery. It can be moved and used in several locations throughout a surgical procedure such that we can achieve more patient-specific “incisional mapping,” as I’m now calling it, rather than uniformly utilizing standard trocar placement sites.

Even without use of this particular innovation, the use of smaller instruments is proving both feasible and advantageous. A study that randomized 75 women scheduled for a hysterectomy to traditional laparoscopy (with a 5- to 10-mm port size) or minilaparoscopy (with a 3-mm port size) found no statistically significant differences in blood loss, hemoglobin drop, pain scores, or analgesic use. The authors concluded that the smaller port sizes did not affect the ability to perform the procedure. Moreover, they noted, the minilaparoscopy group had consistently smaller scars and better cosmesis.5

Another retrospective study of perioperative outcomes with standard laparoscopic, minilaparoscopic, and laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy found that postoperative pain control and the need for analgesic medication was significantly less with minilaparoscopy and laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) hysterectomy, compared with traditional laparoscopy. Pain and medication in patients undergoing minilaparoscopy was reduced by more than 50%, compared with the traditional laparoscopy group, which suggests less operative trauma.6

In my practice, postoperative analgesia is simply intranasal ketorolac tromethamine (Sprix) and/or long-acting tramadol (Conzip); opioids have been eliminated in all minilaparoscopic procedures. We have had no complications, including no trocar-site bleeding, nerve entrapments, trocar-site herniations, or infections. Not every patient is a candidate for consideration of a minilaparoscopic hysterectomy, of course. The patient who has extensive adhesions from multiple previous surgeries or a large uterus with fibroids, for instance, should be treated with traditional laparoscopy regardless of her concerns regarding cosmesis.

No two surgeons are alike; each has his/her own ideas, skill sets, and approaches. Minilaparoscopy may not be for everyone, but given the number of durable miniature instruments now available, it’s an approach to consider integrating into a variety of gynecologic procedures.

For a right salpingo-oophorectomy, for instance, a 3-mm trocar placed at 12 o’clock through the umbilicus can accommodate a 3-mm scope with a high-definition camera, and an 11-mm trocar placed at 6 o’clock can house an energy device. In the right and left lower quadrants, two additional 3-mm trocars can be placed – one to accommodate a grasping instrument and the other to house the scope after the fallopian tube has been transected. A specimen bag can be passed through the 11-mm trocar in the umbilicus for removal of the ovary and tube. With the umbilicus hiding the largest of scars, the procedure is less invasive with better cosmetic results.

Dr. McCarus disclosed that he is a consultant for Ethicon.

References

1. Surg Technol Int. 2015 Nov;27:19-30.

2. Surg Technol Int. 2014 Nov;25:150-6.

3. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Sep-Oct;18(5):640-3.

4. Surg Technol Int 2013 Sep;23:129-32.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Jul-Aug;18(4):455-61.

6. Surg Endosc. 2012 Dec;26(12):3592-6.

Minimally invasive surgeons have been intrigued for more than 2 decades by the clinical aspects and benefits of minilaparoscopy. Miniature instruments (2-3.5 mm) were introduced starting in the late 1980s, and through the 1990s minilaparoscopic procedures were performed across multiple specialties. However, the instrumentation available at the time had limited durability and functionality (for example, a lack of electrosurgical capability), and clinical experience and resulting data were sparse. The minilaparoscopic approach failed to gain momentum and was never widely adopted.

In the past 5-10 years, with new innovations in technology and improved instrumentation, minilaparoscopy is undergoing a renaissance in surgical circles. Medical device companies have developed numerous electrosurgical and other advanced energy options as well as a variety of needle holders, graspers, and other instruments – all with diameters of 3.5 mm or less and with significantly more durability than the earlier generation of mini-instruments. While surgeons oftentimes still use larger telescopes for better visualization, 2- to 3.5-mm telescopes are available in various lengths and angles, and optic quality is continually improving.

The minilaparoscopic approach is more similar to conventional laparoscopy than laparoendoscopic single-site surgery, which has not met early expectations. It is a more logical next step in the evolution of minimally invasive surgery and its goals of further reducing surgical trauma and improving cosmesis. I am performing hysterectomies in which I place two 5-mm nonbladed trocars through incisions inside the umbilicus and a minilaparoscopic percutaneous cannula below the bikini line; it is a “hybrid” procedure, in essence, that incorporates the use of mini-instrumentation.

In addition to diagnostic laparoscopy, I also use minilaparoscopy for some of my patients who need ovarian cystectomy, oophorectomy, appendectomy, treatment of early-stage endometriosis or adhesiolysis. Throughout the world and across multiple specialties, it is being adopted for a wide range of adult and pediatric procedures, from abdominopelvic adhesions and inguinal hernia repair to cholecystectomy, and even to enhance diagnosis in the ED or ICU.1

The importance of surgical scars

The resurgence of interest in minilaparoscopy has been driven largely by its clinical advantages. From a clinical standpoint, less intrusion through the abdominal wall with the use of smaller instruments and fewer insertion points generally means less surgical trauma, and less analgesic medication and postoperative pain, for instance, as well as fewer vascular injuries and a more minimal risk of adhesions. Scar cosmesis also has been viewed as an advantage, just as it was when the abdominal hysterectomy was being replaced by laparoscopic hysterectomy starting in 1989. Still, for me, the clinical aspects have long been at the forefront.

My interest in providing my patients the very best cosmetic results changed after we surveyed patients who were scheduled for a hysterectomy in my practice over the span of 1 year. All patients seen during that time (from November 2012 to November 2013) were asked to complete a questionnaire on their knowledge of hysterectomy incisional scars, their perceptions, and their desires. Almost all of the 200 women who completed the survey – 93% – indicated that cosmetic issues such as scars are important to them (“slightly,” “moderately,” “quite,” or “extremely” important), and of these, 24% chose “extremely important.”

Asked how they feel about the appearance of their scars from prior abdominal surgery, 58% indicated the appearance bothered them to some extent, and 11% said they were “extremely” bothered. Almost all of the 200 patients – 92% – said they would be interested in a surgery that would leave no scars, and 45% said they were “extremely” interested.2

The findings juxtaposed the clinical benefits of more minimally invasive surgery – what had been foremost on my mind – with patients’ attention to and concern about scars. The study demonstrated that patient preferences are just as compelling, if not more, than what the surgeon wants. It showed, moreover, how important it is to discuss hysterectomy incision options – and patient preferences regarding incision location, size, and number – prior to surgery.

When asked about their familiarity with the locations of skin incisions in different hysterectomy procedures (abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic, robotic, and mini), between 25% and 56% indicated they were not at all familiar with them. Familiarity was greatest with incisions in traditional laparoscopic hysterectomy. Yet patients want to have that knowledge: Almost all of the survey participants – 93% – indicated it is important to discuss the location, number, and size of incisions prior to surgery, and 59% said it is “extremely” important.

Patients also were asked to rank a short list of incision locations (above or below the belly button, and above or below the bikini line) from the least desirable to most desirable, and the results suggest just how different personal preferences can be. The most-desirable incision location was below the bikini line for 68% of patients, followed by above the belly button for 16%. The least-desirable location was above the belly button for 69%, followed by below the bikini line for 15%. Asked whether it is cosmetically superior for one’s incisions to be low (below the bikini line), 86% said they agreed.

Other research has similarly shown that cosmesis is important for women undergoing gynecologic surgery. For instance, women in another single-practice study were more likely to prefer single-site and traditional laparoscopic incisions over robotic ones when they were shown photos of an abdomen marked up with the incision lengths and locations typical for each of these three approaches.3 And notably, there has been research looking at the psychological impact of incisional scars specifically in patients who are morbidly obese.

While we may not be accustomed to discussing incisions and scars, it behooves us as surgeons to consider initiating a conversation about incisions with all our patients – regardless of their body mass index and prior surgical history – during the preoperative evaluation.

My hysterectomy approach

I have utilized one of the most recent developments in minilaparoscopy instrumentation – the MiniLap percutaneous surgical system (Teleflex) – to develop a mini technique for hysterectomy I’ve trademarked as the Cosmetic Hysterectomy. The percutaneous system has an outer diameter of 2.3 mm, integrated needle tips that facilitate insertion without a trocar, and a selection of integrated graspers (e.g., a miniature clutch or alligator) that open up to 12.5 mm and can be advanced and retracted through the cannula. The graspers can be locked onto the tissue, and the system itself can be stabilized extracorporeally so that it can be hands free.

For the hysterectomy, I make two 5-mm vertical incisions within the umbilicus – one for a nonbladed 5-mm trocar at 12 o’clock and the other for a second nonbladed 5-mm trocar at 6 o’clock, penetrating the fascia. The trocars house a 30-degree extra-long laparoscope with camera attached, and an advanced bipolar electrosurgery device.

The minilaparoscopic cannula is inserted in the lower-abdominal area through a single 1-mm stab incision, and one or two instruments can be placed as needed. Tissues can be removed vaginally once dissection is completed, and the vaginal cuff can be closed laparoscopically or vaginally. The edges of the minilaparoscopic cannula are approximated together and held with surgical glue or a sterile skin-closure strip. There is no need to close the fascia.4

The percutaneous system opens new windows for minimally invasive surgery. It can be moved and used in several locations throughout a surgical procedure such that we can achieve more patient-specific “incisional mapping,” as I’m now calling it, rather than uniformly utilizing standard trocar placement sites.

Even without use of this particular innovation, the use of smaller instruments is proving both feasible and advantageous. A study that randomized 75 women scheduled for a hysterectomy to traditional laparoscopy (with a 5- to 10-mm port size) or minilaparoscopy (with a 3-mm port size) found no statistically significant differences in blood loss, hemoglobin drop, pain scores, or analgesic use. The authors concluded that the smaller port sizes did not affect the ability to perform the procedure. Moreover, they noted, the minilaparoscopy group had consistently smaller scars and better cosmesis.5

Another retrospective study of perioperative outcomes with standard laparoscopic, minilaparoscopic, and laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy found that postoperative pain control and the need for analgesic medication was significantly less with minilaparoscopy and laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) hysterectomy, compared with traditional laparoscopy. Pain and medication in patients undergoing minilaparoscopy was reduced by more than 50%, compared with the traditional laparoscopy group, which suggests less operative trauma.6

In my practice, postoperative analgesia is simply intranasal ketorolac tromethamine (Sprix) and/or long-acting tramadol (Conzip); opioids have been eliminated in all minilaparoscopic procedures. We have had no complications, including no trocar-site bleeding, nerve entrapments, trocar-site herniations, or infections. Not every patient is a candidate for consideration of a minilaparoscopic hysterectomy, of course. The patient who has extensive adhesions from multiple previous surgeries or a large uterus with fibroids, for instance, should be treated with traditional laparoscopy regardless of her concerns regarding cosmesis.

No two surgeons are alike; each has his/her own ideas, skill sets, and approaches. Minilaparoscopy may not be for everyone, but given the number of durable miniature instruments now available, it’s an approach to consider integrating into a variety of gynecologic procedures.

For a right salpingo-oophorectomy, for instance, a 3-mm trocar placed at 12 o’clock through the umbilicus can accommodate a 3-mm scope with a high-definition camera, and an 11-mm trocar placed at 6 o’clock can house an energy device. In the right and left lower quadrants, two additional 3-mm trocars can be placed – one to accommodate a grasping instrument and the other to house the scope after the fallopian tube has been transected. A specimen bag can be passed through the 11-mm trocar in the umbilicus for removal of the ovary and tube. With the umbilicus hiding the largest of scars, the procedure is less invasive with better cosmetic results.

Dr. McCarus disclosed that he is a consultant for Ethicon.

References

1. Surg Technol Int. 2015 Nov;27:19-30.

2. Surg Technol Int. 2014 Nov;25:150-6.

3. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Sep-Oct;18(5):640-3.

4. Surg Technol Int 2013 Sep;23:129-32.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Jul-Aug;18(4):455-61.

6. Surg Endosc. 2012 Dec;26(12):3592-6.

Minimally invasive surgeons have been intrigued for more than 2 decades by the clinical aspects and benefits of minilaparoscopy. Miniature instruments (2-3.5 mm) were introduced starting in the late 1980s, and through the 1990s minilaparoscopic procedures were performed across multiple specialties. However, the instrumentation available at the time had limited durability and functionality (for example, a lack of electrosurgical capability), and clinical experience and resulting data were sparse. The minilaparoscopic approach failed to gain momentum and was never widely adopted.

In the past 5-10 years, with new innovations in technology and improved instrumentation, minilaparoscopy is undergoing a renaissance in surgical circles. Medical device companies have developed numerous electrosurgical and other advanced energy options as well as a variety of needle holders, graspers, and other instruments – all with diameters of 3.5 mm or less and with significantly more durability than the earlier generation of mini-instruments. While surgeons oftentimes still use larger telescopes for better visualization, 2- to 3.5-mm telescopes are available in various lengths and angles, and optic quality is continually improving.

The minilaparoscopic approach is more similar to conventional laparoscopy than laparoendoscopic single-site surgery, which has not met early expectations. It is a more logical next step in the evolution of minimally invasive surgery and its goals of further reducing surgical trauma and improving cosmesis. I am performing hysterectomies in which I place two 5-mm nonbladed trocars through incisions inside the umbilicus and a minilaparoscopic percutaneous cannula below the bikini line; it is a “hybrid” procedure, in essence, that incorporates the use of mini-instrumentation.

In addition to diagnostic laparoscopy, I also use minilaparoscopy for some of my patients who need ovarian cystectomy, oophorectomy, appendectomy, treatment of early-stage endometriosis or adhesiolysis. Throughout the world and across multiple specialties, it is being adopted for a wide range of adult and pediatric procedures, from abdominopelvic adhesions and inguinal hernia repair to cholecystectomy, and even to enhance diagnosis in the ED or ICU.1

The importance of surgical scars

The resurgence of interest in minilaparoscopy has been driven largely by its clinical advantages. From a clinical standpoint, less intrusion through the abdominal wall with the use of smaller instruments and fewer insertion points generally means less surgical trauma, and less analgesic medication and postoperative pain, for instance, as well as fewer vascular injuries and a more minimal risk of adhesions. Scar cosmesis also has been viewed as an advantage, just as it was when the abdominal hysterectomy was being replaced by laparoscopic hysterectomy starting in 1989. Still, for me, the clinical aspects have long been at the forefront.

My interest in providing my patients the very best cosmetic results changed after we surveyed patients who were scheduled for a hysterectomy in my practice over the span of 1 year. All patients seen during that time (from November 2012 to November 2013) were asked to complete a questionnaire on their knowledge of hysterectomy incisional scars, their perceptions, and their desires. Almost all of the 200 women who completed the survey – 93% – indicated that cosmetic issues such as scars are important to them (“slightly,” “moderately,” “quite,” or “extremely” important), and of these, 24% chose “extremely important.”

Asked how they feel about the appearance of their scars from prior abdominal surgery, 58% indicated the appearance bothered them to some extent, and 11% said they were “extremely” bothered. Almost all of the 200 patients – 92% – said they would be interested in a surgery that would leave no scars, and 45% said they were “extremely” interested.2

The findings juxtaposed the clinical benefits of more minimally invasive surgery – what had been foremost on my mind – with patients’ attention to and concern about scars. The study demonstrated that patient preferences are just as compelling, if not more, than what the surgeon wants. It showed, moreover, how important it is to discuss hysterectomy incision options – and patient preferences regarding incision location, size, and number – prior to surgery.

When asked about their familiarity with the locations of skin incisions in different hysterectomy procedures (abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic, robotic, and mini), between 25% and 56% indicated they were not at all familiar with them. Familiarity was greatest with incisions in traditional laparoscopic hysterectomy. Yet patients want to have that knowledge: Almost all of the survey participants – 93% – indicated it is important to discuss the location, number, and size of incisions prior to surgery, and 59% said it is “extremely” important.

Patients also were asked to rank a short list of incision locations (above or below the belly button, and above or below the bikini line) from the least desirable to most desirable, and the results suggest just how different personal preferences can be. The most-desirable incision location was below the bikini line for 68% of patients, followed by above the belly button for 16%. The least-desirable location was above the belly button for 69%, followed by below the bikini line for 15%. Asked whether it is cosmetically superior for one’s incisions to be low (below the bikini line), 86% said they agreed.

Other research has similarly shown that cosmesis is important for women undergoing gynecologic surgery. For instance, women in another single-practice study were more likely to prefer single-site and traditional laparoscopic incisions over robotic ones when they were shown photos of an abdomen marked up with the incision lengths and locations typical for each of these three approaches.3 And notably, there has been research looking at the psychological impact of incisional scars specifically in patients who are morbidly obese.

While we may not be accustomed to discussing incisions and scars, it behooves us as surgeons to consider initiating a conversation about incisions with all our patients – regardless of their body mass index and prior surgical history – during the preoperative evaluation.

My hysterectomy approach

I have utilized one of the most recent developments in minilaparoscopy instrumentation – the MiniLap percutaneous surgical system (Teleflex) – to develop a mini technique for hysterectomy I’ve trademarked as the Cosmetic Hysterectomy. The percutaneous system has an outer diameter of 2.3 mm, integrated needle tips that facilitate insertion without a trocar, and a selection of integrated graspers (e.g., a miniature clutch or alligator) that open up to 12.5 mm and can be advanced and retracted through the cannula. The graspers can be locked onto the tissue, and the system itself can be stabilized extracorporeally so that it can be hands free.

For the hysterectomy, I make two 5-mm vertical incisions within the umbilicus – one for a nonbladed 5-mm trocar at 12 o’clock and the other for a second nonbladed 5-mm trocar at 6 o’clock, penetrating the fascia. The trocars house a 30-degree extra-long laparoscope with camera attached, and an advanced bipolar electrosurgery device.

The minilaparoscopic cannula is inserted in the lower-abdominal area through a single 1-mm stab incision, and one or two instruments can be placed as needed. Tissues can be removed vaginally once dissection is completed, and the vaginal cuff can be closed laparoscopically or vaginally. The edges of the minilaparoscopic cannula are approximated together and held with surgical glue or a sterile skin-closure strip. There is no need to close the fascia.4

The percutaneous system opens new windows for minimally invasive surgery. It can be moved and used in several locations throughout a surgical procedure such that we can achieve more patient-specific “incisional mapping,” as I’m now calling it, rather than uniformly utilizing standard trocar placement sites.

Even without use of this particular innovation, the use of smaller instruments is proving both feasible and advantageous. A study that randomized 75 women scheduled for a hysterectomy to traditional laparoscopy (with a 5- to 10-mm port size) or minilaparoscopy (with a 3-mm port size) found no statistically significant differences in blood loss, hemoglobin drop, pain scores, or analgesic use. The authors concluded that the smaller port sizes did not affect the ability to perform the procedure. Moreover, they noted, the minilaparoscopy group had consistently smaller scars and better cosmesis.5

Another retrospective study of perioperative outcomes with standard laparoscopic, minilaparoscopic, and laparoendoscopic single-site hysterectomy found that postoperative pain control and the need for analgesic medication was significantly less with minilaparoscopy and laparoendoscopic single-site (LESS) hysterectomy, compared with traditional laparoscopy. Pain and medication in patients undergoing minilaparoscopy was reduced by more than 50%, compared with the traditional laparoscopy group, which suggests less operative trauma.6

In my practice, postoperative analgesia is simply intranasal ketorolac tromethamine (Sprix) and/or long-acting tramadol (Conzip); opioids have been eliminated in all minilaparoscopic procedures. We have had no complications, including no trocar-site bleeding, nerve entrapments, trocar-site herniations, or infections. Not every patient is a candidate for consideration of a minilaparoscopic hysterectomy, of course. The patient who has extensive adhesions from multiple previous surgeries or a large uterus with fibroids, for instance, should be treated with traditional laparoscopy regardless of her concerns regarding cosmesis.

No two surgeons are alike; each has his/her own ideas, skill sets, and approaches. Minilaparoscopy may not be for everyone, but given the number of durable miniature instruments now available, it’s an approach to consider integrating into a variety of gynecologic procedures.

For a right salpingo-oophorectomy, for instance, a 3-mm trocar placed at 12 o’clock through the umbilicus can accommodate a 3-mm scope with a high-definition camera, and an 11-mm trocar placed at 6 o’clock can house an energy device. In the right and left lower quadrants, two additional 3-mm trocars can be placed – one to accommodate a grasping instrument and the other to house the scope after the fallopian tube has been transected. A specimen bag can be passed through the 11-mm trocar in the umbilicus for removal of the ovary and tube. With the umbilicus hiding the largest of scars, the procedure is less invasive with better cosmetic results.

Dr. McCarus disclosed that he is a consultant for Ethicon.

References

1. Surg Technol Int. 2015 Nov;27:19-30.

2. Surg Technol Int. 2014 Nov;25:150-6.

3. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Sep-Oct;18(5):640-3.

4. Surg Technol Int 2013 Sep;23:129-32.

5. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Jul-Aug;18(4):455-61.

6. Surg Endosc. 2012 Dec;26(12):3592-6.

Strategies to overcome the loss of port placement triangulation

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by