User login

Severe pediatric oral mucositis

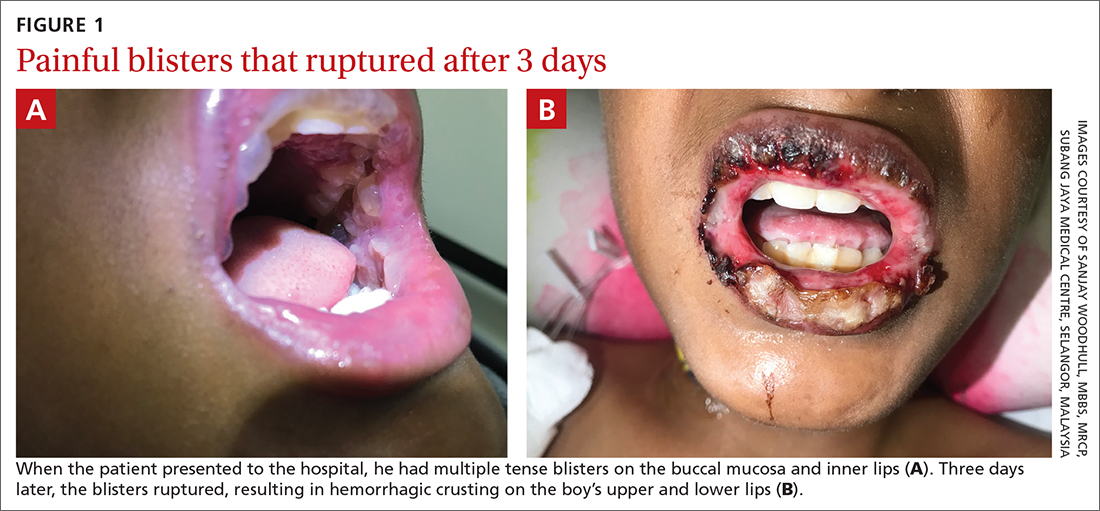

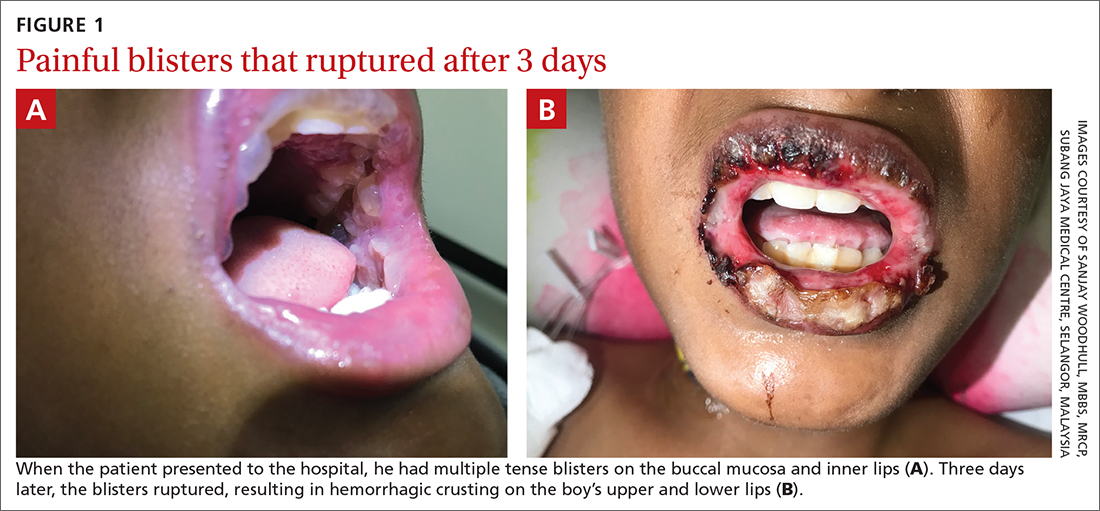

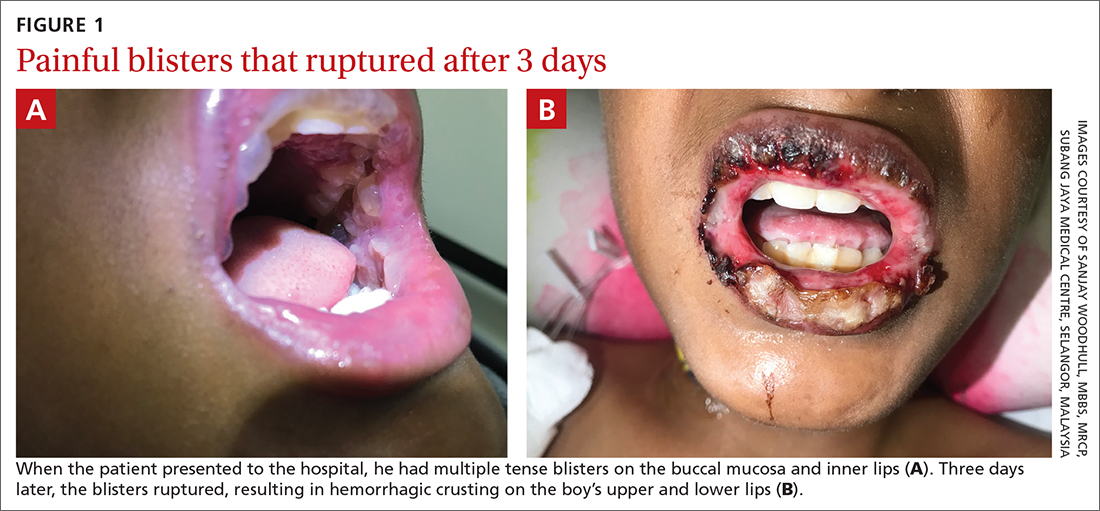

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2 Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2 Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2 Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444