User login

Telepsychiatry: What you need to know

The need for mental health services has never been greater. Unfortunately, many patients have limited access to psychiatric treatment, especially those who live in rural areas. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of psychiatric services through telecommunications technology, usually video conferencing—may help address this problem. Even before the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telepsychiatry was becoming increasingly common. A survey of US mental health facilities found that the proportion of facilities offering telepsychiatry nearly doubled from 2010 to 2017, from 15.2% to 29.2%.1

In this article, we describe examples of where and how telepsychiatry is being used successfully, and its potential advantages. We discuss concerns about its use, its impact on the therapeutic alliance, and patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of it. We also discuss the legal, technological, and financial aspects of using telepsychiatry. With an increased understanding of these issues, psychiatric clinicians will be better able to integrate telepsychiatry into their practices.

How and where is telepsychiatry being used

In addition to being used to provide psychotherapy, telepsychiatry is being employed for diagnosis and evaluation; clinical consultations; research; supervision, mentoring, and education of trainees; development of treatment programs; and public health. Telepsychiatry is an excellent mechanism to provide high-level second opinions to primary care physicians and psychiatrists on complex cases for both diagnostic purposes and treatment.

Evidence suggests that telepsychiatry can play a beneficial role in a variety of settings, and for a range of patient populations.

Emergency departments (EDs). Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in EDs could result in a quicker disposition of patients and reduced crowding and wait times. A survey of on-call clinicians in a pediatric ED found that using telepsychiatry for on-site psychiatric consultations decreased patients’ length of stay, improved resident on-call burden, and reduced factors related to physician burnout.2 In this study, telepsychiatry use reduced travel for face-to-face evaluations by 75% and saved more than 2 hours per call day.2

Medical clinics. Using telepsychiatry to deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduced symptoms of depression or anxiety among 203 primary care patients.3 Incorporating telepsychiatry into existing integrated primary care settings is becoming more common. For example, an integrated-care model that includes telepsychiatry is serving the needs of complex patients in a high-volume, urban primary care clinic in Colorado.4

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams. Telepsychiatry is being used by ACT teams for crisis intervention and to reduce inpatient hospitalizations.5

Continue to: Correctional facilities

Correctional facilities. With the downsizing and closure of many state psychiatric hospitals across the United States over the last several decades, jails and prisons have become de facto mental health hospitals. This situation presents many challenges, including access to mental health care and the need to avoid medications with the potential for abuse. Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in correctional facilities can improve access to mental health care.

Geriatric patients.

Children and adolescents. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) program is a telepsychiatry consultation service that has been able to provide cost-effective, timely, remote consultation to primary care clinicians who care for youth and perinatal women.8 New York has a pediatric collaborative care program, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care (CAP PC), that incorporates telepsychiatry consultations for families who live >1 hour away from one of the program’s treatment sites.9

Patients with cancer. A literature review that included 9 studies found no statistically significant differences between standard face-to-face interventions and telepsychiatry for improving quality-of-life scores among patients receiving treatment for cancer.10

Patients with insomnia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is often recommended as a first-line treatment, but is not available for many patients. A recent study showed that CBT-I provided via telepsychiatry for patients with shift work sleep disorder was as effective as face-to-face therapy.11 Increasing the availability of this treatment could decrease reliance on pharmacotherapy for sleep.

Patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Treatment for patients with OUD is limited by access to, and availability of, psychiatric clinicians. Telepsychiatry can help bridge this gap. One example of such use is in Ontario, Canada, where more than 10,000 patients with concurrent opiate abuse and other mental health disorders have received care via telepsychiatry since 2008.12

Continue to: Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

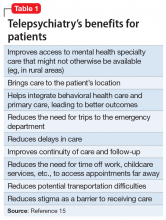

There is a crisis in mental health care in rural areas of the United States. A study assessing delivery of care to US residents who live in rural areas found these patients’ mental health–related quality of life was 2.5 standard deviations below the national mean.13 Additionally, the need for treatment is expected to rise as the number of psychiatrists falls. According to a 2017 National Council for Behavioral Health report,14 by 2025, demand may outstrip supply by 6,090 to 15,600 psychiatrists. While telepsychiatry cannot improve this shortage per se, it can help increase access to psychiatric services. The potential benefits of telepsychiatry for patients are summarized in Table 1.15

Telepsychiatry may be more cost-effective than traditional face-to-face treatment. A cost analysis of an expanding, multistate behavioral telehealth intervention program for rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations found substantial cost savings associated with telepsychiatry.16 In this analysis, the estimated cost efficiencies of telepsychiatry were more evident in rural communities, and having a multistate center was less expensive than each state operating independently.16

Most importantly, evidence suggests that treatment delivered via telepsychiatry is at least as effective as traditional face-to-face care. In a review that included >150 studies, Bashshur et al17 concluded, “Effective approaches to the long-term management of mental illness include monitoring, surveillance, mental health promotion, mental illness prevention, and biopsychosocial treatment programs. The empirical evidence … demonstrates the capability of [telepsychiatry] to perform these functions more efficiently and as well as or more effectively than in-person care

Clinician and patient attitudes toward telepsychiatry

Clinicians have legitimate concerns about the quality of care being delivered when using telepsychiatry. Are patients satisfied with treatment delivered via telepsychiatry? Can a therapeutic alliance be established and maintained? It appears that clinicians may have more concerns than patients do.18

A study of telepsychiatry consultations for patients in rural primary care clinics performed by clinicians at an urban health center found that patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with telepsychiatry.19 Both patients and clinicians believed that telepsychiatry provided patients with better access to care. There was a high degree of agreement between patients and clinician responses.19

Continue to: In a review of...

In a review of 452 telepsychiatry studies, Hubley et al20 focused on satisfaction, reliability, treatment outcomes, implementation outcomes, cost effectiveness, and legal issues. They concluded that patients and clinicians are generally satisfied with telepsychiatry services. Interestingly, clinicians expressed more concerns about the potential adverse effects of telepsychiatry on therapeutic rapport. Hubley et al20 found no published reports of adverse events associated with telepsychiatry use.

In a study of school-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting, Mayworm et al21 found that patients were highly satisfied with both in-person and telepsychiatry services, and there were no significant differences in preference. This study also found that telepsychiatry services were more time-efficient than in-person services.

A study of using telepsychiatry to treat unipolar depression found that patient satisfaction scores improved with increasing number of video-based sessions, and were similar among all age groups.22 An analysis of this study found that total satisfaction scores were higher for patients than for clinicians.23

In a study of satisfaction with telepsychiatry among community-dwelling older veterans, 90% of participants reported liking or even preferring telepsychiatry, even though the experience was novel for most of them.24

As always, patients’ preferences need to be kept in mind when considering what services can and should be provided via telepsychiatry, because not all patients will find it acceptable. For example, in a study of veterans’ attitudes toward treatment via telepsychiatry, Goetter et al25 found that interest was mixed. Twenty-six percent of patients were “not at all comfortable,” while 13% were “extremely comfortable” using telepsychiatry from home. Notably, 33% indicated a clear preference for telepsychiatry compared to in-person mental health visits.

Continue to: Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Box 1

As part of the efforts to contain the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the use of telemedicine, including telepsychiatry, has increased substantially. Here are a few key facts to keep in mind while practicing telepsychiatry during this pandemic:

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services relaxed requirements for telehealth starting March 6, 2020 and for the duration of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Under this new waiver, Medicare can pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth across the country and including in patient’s places of residence. For details, see www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. This fact sheet reviews relevant information, including billing codes.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements, specifically those for secure communications, will not be enforced when telehealth is used under the new waiver. Because of this, popular but unsecure software applications, such as Apple’s FaceTime, Microsoft’s Teams, or Facebook’s Messenger, WhatsApp, and Messenger Rooms, can be used.

- Informed consent for the use of telepsychiatry in this situation should be obtained from the patient or his/her guardian, and documented in the patient’s medical record. For example: “Informed consent received for providing services via video teleconferencing to the home in order to protect the patient from COVID-19 exposure. Confidentiality issues were discussed.”

Licensure. State licensing and medical regulatory organizations consider the care provided via telepsychiatry to be rendered where the patient is physically located when services are rendered. Because of this, psychiatrists who use telepsychiatry generally need to hold a license in the state where their patients are located, regardless of where the psychiatrist is located.

Some states offer special telemedicine licenses. Typically, these licenses allow clinicians to practice across state lines without having to obtain a full professional license from the state. Be sure to check with the relevant state medical board where you intend to practice.

Because state laws related to telepsychiatry are continuously evolving, we suggest that clinicians continually check these laws and obtain a regulatory response in writing so there is ongoing documentation. For more information on this topic, see “Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: Understanding the rules” at MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Malpractice insurance. Some insurance companies offer coverage that includes the practice of telepsychiatry, whereas other carriers require the purchase of additional coverage for telepsychiatry. There may be additional requirements for practicing across state lines. Be sure to check with your insurer.

Continue to: Technical requirements and costs

Technical requirements and costs

In order to perform telepsychiatry, one needs Internet access, appropriate hardware such as a desktop or laptop computer or tablet, and a video conferencing application. Software must be HIPAA-compliant, although this requirement is not being enforced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several popular video conferencing platforms were designed for or have versions suitable for telemedicine, including Zoom, Doxy.me, Vidyo, and Skype.

The use of different electronic health record (EHR) systems by various health care systems is a barrier to using telepsychiatry.

Box 2

The North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program (NC-STeP) began in 2013 by providing telepsychiatry services in hospital emergency departments (EDs) to individuals experiencing an acute behavioral health crisis. In 2018, the program expanded to include community-based primary care sites using a “hybrid” collaborative-care model. This model benefits patients by improving access to mental health specialty care; reducing the need for trips to the ED and inpatient admissions, thus decompressing EDs; improving compliance with treatment; reducing delays in care; reducing stigma; and improving continuity of care and follow-up. East Carolina University’s Center for Telepsychiatry and E-Behavioral Health is the home for this program, which is connecting hospital EDs and community-based primary care sites across North Carolina.

NC-STeP provides patients with a faceto-face interaction with a clinician through real-time video conferencing that is facilitated using mobile carts and desktop units. A web portal combines scheduling, electronic medical records, health information exchange functions, and data management systems.

NC-STeP has significantly reduced patient length of stay in EDs, provided cost savings to the health care delivery system through overturned involuntary commitments, improved ED throughout, and reduced patient boarding time; and has achieved high rates of patient, staff, and clinician satisfaction. Highlights of the program include:

- 57 hospitals and 8 communitybased sites in the network (as of January 1, 2020)

- 8 clinical hubs are operational, with 53 consultant clinicians

- 40,573 telepsychiatry assessments (as of January 1, 2020)

- 5,631 involuntary commitments overturned, thus preventing unnecessary hospitalizations representing a saving of $30,407,400 to the state

- Since program inception, >40% of ED patients who received telepsychiatry services were discharged to home

- 32% of the patients served had no insurance coverage

- Currently, the average consult elapsed time (in queue to consult complete) is 3 hours 9 minutes.

For more information about this program, see www.ecu.edu/cs-dhs/ncstep.

Our practice has extensive experience with telepsychiatry (Box 3), and for us, the specific costs associated with providing telepsychiatry services include maintenance of infrastructure and the purchase of hardware (eg, computers, smartphones, tablets), a video conferencing application (some free versions are available), EHR systems, and Internet access.

Box 3

Our practice (Rural Psychiatry Associates, Grand Forks, North Dakota) and our close associates have provided telepsychiatry services to >200 mental health clinics, hospitals, Native American villages, prisons, and nursing homes, mostly in rural and underserved areas. To provide these services, in addition to physicians, we also utilize nurse practitioners and physician assistants, for whom we provide extensive education, training, and supervision. We also provide education to the staff at the facilities where we provide services.

For nursing homes, we often use what is referred to as a “blended mode,” where we combine telepsychiatry visits with in-person, on-site visits, alternating monthly. In this model, we also typically alternate one physician with one nonphysician clinician at each facility. For continuity of care, the same clinicians service the same facilities. For very distant facilities with only a few patients, only telepsychiatry is utilized. However, initial services are always provided by a physician to establish a relationship, discuss policies and procedures, and evaluate patients face-to-face.

Telepsychiatry is increasingly used for education and mentoring. We have found telepsychiatry to be especially useful when working with psychiatric residents on a realtime basis as they evaluate and treat patients at a different location.

Reimbursement for telepsychiatry

Private insurance reimbursement for treatment delivered via telepsychiatry obviously depends on the specific insurance company. Some facilities, such as nursing homes, hospitals, medical clinics, and correctional facilities, offer lump-sum fees to clinicians for providing contracted services. Some clinicians are providing telepsychiatry as direct-bill or concierge services, which require direct payment from the patient without any reimbursement from insurance.

Medicare Part B covers some telepsychiatry services, but only under certain conditions.28 Previously, reimbursement was limited to services provided to patients who live in rural areas. However, on November 1, 2019, eligibility for telehealth services for Medicare Advantage (MA) recipients was expanded to include patients in both urban and rural locations. Patients covered by MA also can receive telehealth services from their home, instead of having to drive to a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services–qualified telehealth service center.

Continue to: Medicaid is the single...

Medicaid is the single largest payer for mental health services in the United States,29 and all Medicaid programs reimburse for some telepsychiatry services. As with all Medicaid health care, fees paid for telepsychiatry are state-specific. Since 2013, several state Medicaid programs, including New York,30 have expanded the list of eligible telehealth sites to include schools, thereby giving children virtual access to mental health clinicians.

Getting started

Clinicians who are interested in starting to provide treatment via telepsychiatry can begin by reviewing the American Psychiatric Association’s Telepsychiatry Toolkit at www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit. This toolkit, which is being continually updated, features numerous training videos for clinicians new to telepsychiatry, such as Learning To Do Telemental Health (www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/learning-telemental-health) and The Credentialing Process (www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/credentialing-process). Before starting, also consider reviewing the steps listed in Table 2.

Bottom Line

Evidence suggests telepsychiatry can be beneficial for a wide range of patient populations and settings. Most patients accept its use, and some actually prefer it to face-to-face care. Telepsychiatry may be especially useful for patients who have limited access to psychiatric treatment, such as those who live in rural areas. Factors to consider before incorporating telepsychiatry into your practice include addressing various legal, technological, and financial requirements.

Related Resources

- Von Hafften A. Telepsychiatry practice guidelines. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/practice-guidelines.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Telehealth and telemedicine: a research anthology of law and policy resources. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/anthologies/anthologies-telehealth.html. Reviewed July 31, 2019.

- American Telemedicine Association. https://www.americantelemed.org/.

1. Spivak S, Spivak A, Cullen B, et al. Telepsychiatry use in U.S. mental health facilities, 2010-2017. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;71(2):appips201900261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900261.

2. Reliford A, Adebanjo B. Use of telepsychiatry in pediatric emergency room to decrease length of stay for psychiatric patients, improve resident on-call burden, and reduce factors related to physician burnout. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(9):828-832.

3. Mathiasen K, Riper H, Andersen TE, et al. Guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for adult depression and anxiety in routine secondary care: observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e10927. doi: 10.2196/10927.

4. Waugh M, Calderone J, Brown Levey S, et al. Using telepsychiatry to enrich existing integrated primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(8):762-768.

5. Swanson CL, Trestman RL. Rural assertive community treatment and telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(4):269-273.

6. Gentry MT, Lapid MI, Rummans TA. Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):109-127.

7. Christensen LF, Moller AM, Hansen JP, et al. Patients’ and providers’ experiences with video consultations used in the treatment of older patients with unipolar depression: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020;27(3):258-271.

8. Marcus S, Malas N, Dopp R, et al. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care program: building a telepsychiatry consultation service. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):849-852.

9. Kaye DL, Fornari V, Scharf M, et al. Description of a multi-university education and collaborative care child psychiatry access program: New York State’s CAP PC. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:32-36.

10. Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(6):397-405.

11. Peter L, Reindl R, Zauter S, et al. Effectiveness of an online CBT-I intervention and a face-to-face treatment for shift work sleep disorder: a comparison of sleep diary data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):E3081. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173081.

12. LaBelle B, Franklyn AM, Pkh Nguyen V, et al. Characterizing the use of telepsychiatry for patients with opioid use disorder and cooccurring mental health disorders in Ontario, Canada. Int J Telemed Appl. 2018;2018(3):1-7.

13. Fortney JC, Heagerty PJ, Bauer AM, et al. Study to promote innovation in rural integrated telepsychiatry (SPIRIT): rationale and design of a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of managing complex psychiatric disorders in rural primary care clinics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;90:105873. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105873.

14. Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage. Published February 12, 2018. Accessed May 14, 2020.

15. American Psychiatric Association. What is telepsychiatry? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-telepsychiatry. Published 2017. Accessed May 14, 2020.

16. Yilmaz SK, Horn BP, Fore C, et al. An economic cost analysis of an expanding, multi-state behavioural telehealth intervention. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(6):353-364.

17. Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Bashshur N, et al. The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in mental disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87-113.

18. Lopez A, Schwenk S, Schneck CD, et al. Technology-based mental health treatment and the impact on the therapeutic alliance. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(8):76.

19. Schubert NJ, Backman PJ, Bhatla R, et al. Telepsychiatry and patient-provider concordance. Can J Rural Med. 2019;24(3):75-82.

20. Hubley S, Lynch SB, Schneck C, et al. Review of key telepsychiatry outcomes. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(2):269-282.

21. Mayworm AM, Lever N, Gloff N, et al. School-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting: efficiency and satisfaction with care. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(4):446-454.

22. Christensen LF, Gildberg FA, Sibbersen C, et al. Videoconferences and treatment of depression: satisfaction score correlated with number of sessions attended but not with age [published online October 31, 2019]. Telemed J E Health. 2019. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0129.

23. Christensen LF, Gildberg FA, Sibbersen C, et al. Disagreement in satisfaction between patients and providers in the use of videoconferences by depressed adults. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(5):614-620.

24. Hantke N, Lajoy M, Gould CE, et al. Patient satisfaction with geriatric psychiatry services via video teleconference. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(4):491-494.

25. Goetter EM, Blackburn AM, Bui E, et al. Veterans’ prospective attitudes about mental health treatment using telehealth. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2019;57(9):38-43.

26. Vanderpool D. Top 10 myths about telepsychiatry. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14(9-10):13-15.

27. Butterfield A. Telepsychiatric evaluation and consultation in emergency care settings. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):467-478.

28. Medicare.gov. Telehealth. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/telehealth. Accessed May 14, 2020.

29. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Behavioral Health Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/bhs/index.html. Accessed May 14, 2020.

30. New York Pub Health Law §2999-cc (2017).

The need for mental health services has never been greater. Unfortunately, many patients have limited access to psychiatric treatment, especially those who live in rural areas. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of psychiatric services through telecommunications technology, usually video conferencing—may help address this problem. Even before the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telepsychiatry was becoming increasingly common. A survey of US mental health facilities found that the proportion of facilities offering telepsychiatry nearly doubled from 2010 to 2017, from 15.2% to 29.2%.1

In this article, we describe examples of where and how telepsychiatry is being used successfully, and its potential advantages. We discuss concerns about its use, its impact on the therapeutic alliance, and patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of it. We also discuss the legal, technological, and financial aspects of using telepsychiatry. With an increased understanding of these issues, psychiatric clinicians will be better able to integrate telepsychiatry into their practices.

How and where is telepsychiatry being used

In addition to being used to provide psychotherapy, telepsychiatry is being employed for diagnosis and evaluation; clinical consultations; research; supervision, mentoring, and education of trainees; development of treatment programs; and public health. Telepsychiatry is an excellent mechanism to provide high-level second opinions to primary care physicians and psychiatrists on complex cases for both diagnostic purposes and treatment.

Evidence suggests that telepsychiatry can play a beneficial role in a variety of settings, and for a range of patient populations.

Emergency departments (EDs). Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in EDs could result in a quicker disposition of patients and reduced crowding and wait times. A survey of on-call clinicians in a pediatric ED found that using telepsychiatry for on-site psychiatric consultations decreased patients’ length of stay, improved resident on-call burden, and reduced factors related to physician burnout.2 In this study, telepsychiatry use reduced travel for face-to-face evaluations by 75% and saved more than 2 hours per call day.2

Medical clinics. Using telepsychiatry to deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduced symptoms of depression or anxiety among 203 primary care patients.3 Incorporating telepsychiatry into existing integrated primary care settings is becoming more common. For example, an integrated-care model that includes telepsychiatry is serving the needs of complex patients in a high-volume, urban primary care clinic in Colorado.4

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams. Telepsychiatry is being used by ACT teams for crisis intervention and to reduce inpatient hospitalizations.5

Continue to: Correctional facilities

Correctional facilities. With the downsizing and closure of many state psychiatric hospitals across the United States over the last several decades, jails and prisons have become de facto mental health hospitals. This situation presents many challenges, including access to mental health care and the need to avoid medications with the potential for abuse. Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in correctional facilities can improve access to mental health care.

Geriatric patients.

Children and adolescents. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) program is a telepsychiatry consultation service that has been able to provide cost-effective, timely, remote consultation to primary care clinicians who care for youth and perinatal women.8 New York has a pediatric collaborative care program, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care (CAP PC), that incorporates telepsychiatry consultations for families who live >1 hour away from one of the program’s treatment sites.9

Patients with cancer. A literature review that included 9 studies found no statistically significant differences between standard face-to-face interventions and telepsychiatry for improving quality-of-life scores among patients receiving treatment for cancer.10

Patients with insomnia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is often recommended as a first-line treatment, but is not available for many patients. A recent study showed that CBT-I provided via telepsychiatry for patients with shift work sleep disorder was as effective as face-to-face therapy.11 Increasing the availability of this treatment could decrease reliance on pharmacotherapy for sleep.

Patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Treatment for patients with OUD is limited by access to, and availability of, psychiatric clinicians. Telepsychiatry can help bridge this gap. One example of such use is in Ontario, Canada, where more than 10,000 patients with concurrent opiate abuse and other mental health disorders have received care via telepsychiatry since 2008.12

Continue to: Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

There is a crisis in mental health care in rural areas of the United States. A study assessing delivery of care to US residents who live in rural areas found these patients’ mental health–related quality of life was 2.5 standard deviations below the national mean.13 Additionally, the need for treatment is expected to rise as the number of psychiatrists falls. According to a 2017 National Council for Behavioral Health report,14 by 2025, demand may outstrip supply by 6,090 to 15,600 psychiatrists. While telepsychiatry cannot improve this shortage per se, it can help increase access to psychiatric services. The potential benefits of telepsychiatry for patients are summarized in Table 1.15

Telepsychiatry may be more cost-effective than traditional face-to-face treatment. A cost analysis of an expanding, multistate behavioral telehealth intervention program for rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations found substantial cost savings associated with telepsychiatry.16 In this analysis, the estimated cost efficiencies of telepsychiatry were more evident in rural communities, and having a multistate center was less expensive than each state operating independently.16

Most importantly, evidence suggests that treatment delivered via telepsychiatry is at least as effective as traditional face-to-face care. In a review that included >150 studies, Bashshur et al17 concluded, “Effective approaches to the long-term management of mental illness include monitoring, surveillance, mental health promotion, mental illness prevention, and biopsychosocial treatment programs. The empirical evidence … demonstrates the capability of [telepsychiatry] to perform these functions more efficiently and as well as or more effectively than in-person care

Clinician and patient attitudes toward telepsychiatry

Clinicians have legitimate concerns about the quality of care being delivered when using telepsychiatry. Are patients satisfied with treatment delivered via telepsychiatry? Can a therapeutic alliance be established and maintained? It appears that clinicians may have more concerns than patients do.18

A study of telepsychiatry consultations for patients in rural primary care clinics performed by clinicians at an urban health center found that patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with telepsychiatry.19 Both patients and clinicians believed that telepsychiatry provided patients with better access to care. There was a high degree of agreement between patients and clinician responses.19

Continue to: In a review of...

In a review of 452 telepsychiatry studies, Hubley et al20 focused on satisfaction, reliability, treatment outcomes, implementation outcomes, cost effectiveness, and legal issues. They concluded that patients and clinicians are generally satisfied with telepsychiatry services. Interestingly, clinicians expressed more concerns about the potential adverse effects of telepsychiatry on therapeutic rapport. Hubley et al20 found no published reports of adverse events associated with telepsychiatry use.

In a study of school-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting, Mayworm et al21 found that patients were highly satisfied with both in-person and telepsychiatry services, and there were no significant differences in preference. This study also found that telepsychiatry services were more time-efficient than in-person services.

A study of using telepsychiatry to treat unipolar depression found that patient satisfaction scores improved with increasing number of video-based sessions, and were similar among all age groups.22 An analysis of this study found that total satisfaction scores were higher for patients than for clinicians.23

In a study of satisfaction with telepsychiatry among community-dwelling older veterans, 90% of participants reported liking or even preferring telepsychiatry, even though the experience was novel for most of them.24

As always, patients’ preferences need to be kept in mind when considering what services can and should be provided via telepsychiatry, because not all patients will find it acceptable. For example, in a study of veterans’ attitudes toward treatment via telepsychiatry, Goetter et al25 found that interest was mixed. Twenty-six percent of patients were “not at all comfortable,” while 13% were “extremely comfortable” using telepsychiatry from home. Notably, 33% indicated a clear preference for telepsychiatry compared to in-person mental health visits.

Continue to: Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Box 1

As part of the efforts to contain the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the use of telemedicine, including telepsychiatry, has increased substantially. Here are a few key facts to keep in mind while practicing telepsychiatry during this pandemic:

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services relaxed requirements for telehealth starting March 6, 2020 and for the duration of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Under this new waiver, Medicare can pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth across the country and including in patient’s places of residence. For details, see www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. This fact sheet reviews relevant information, including billing codes.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements, specifically those for secure communications, will not be enforced when telehealth is used under the new waiver. Because of this, popular but unsecure software applications, such as Apple’s FaceTime, Microsoft’s Teams, or Facebook’s Messenger, WhatsApp, and Messenger Rooms, can be used.

- Informed consent for the use of telepsychiatry in this situation should be obtained from the patient or his/her guardian, and documented in the patient’s medical record. For example: “Informed consent received for providing services via video teleconferencing to the home in order to protect the patient from COVID-19 exposure. Confidentiality issues were discussed.”

Licensure. State licensing and medical regulatory organizations consider the care provided via telepsychiatry to be rendered where the patient is physically located when services are rendered. Because of this, psychiatrists who use telepsychiatry generally need to hold a license in the state where their patients are located, regardless of where the psychiatrist is located.

Some states offer special telemedicine licenses. Typically, these licenses allow clinicians to practice across state lines without having to obtain a full professional license from the state. Be sure to check with the relevant state medical board where you intend to practice.

Because state laws related to telepsychiatry are continuously evolving, we suggest that clinicians continually check these laws and obtain a regulatory response in writing so there is ongoing documentation. For more information on this topic, see “Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: Understanding the rules” at MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Malpractice insurance. Some insurance companies offer coverage that includes the practice of telepsychiatry, whereas other carriers require the purchase of additional coverage for telepsychiatry. There may be additional requirements for practicing across state lines. Be sure to check with your insurer.

Continue to: Technical requirements and costs

Technical requirements and costs

In order to perform telepsychiatry, one needs Internet access, appropriate hardware such as a desktop or laptop computer or tablet, and a video conferencing application. Software must be HIPAA-compliant, although this requirement is not being enforced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several popular video conferencing platforms were designed for or have versions suitable for telemedicine, including Zoom, Doxy.me, Vidyo, and Skype.

The use of different electronic health record (EHR) systems by various health care systems is a barrier to using telepsychiatry.

Box 2

The North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program (NC-STeP) began in 2013 by providing telepsychiatry services in hospital emergency departments (EDs) to individuals experiencing an acute behavioral health crisis. In 2018, the program expanded to include community-based primary care sites using a “hybrid” collaborative-care model. This model benefits patients by improving access to mental health specialty care; reducing the need for trips to the ED and inpatient admissions, thus decompressing EDs; improving compliance with treatment; reducing delays in care; reducing stigma; and improving continuity of care and follow-up. East Carolina University’s Center for Telepsychiatry and E-Behavioral Health is the home for this program, which is connecting hospital EDs and community-based primary care sites across North Carolina.

NC-STeP provides patients with a faceto-face interaction with a clinician through real-time video conferencing that is facilitated using mobile carts and desktop units. A web portal combines scheduling, electronic medical records, health information exchange functions, and data management systems.

NC-STeP has significantly reduced patient length of stay in EDs, provided cost savings to the health care delivery system through overturned involuntary commitments, improved ED throughout, and reduced patient boarding time; and has achieved high rates of patient, staff, and clinician satisfaction. Highlights of the program include:

- 57 hospitals and 8 communitybased sites in the network (as of January 1, 2020)

- 8 clinical hubs are operational, with 53 consultant clinicians

- 40,573 telepsychiatry assessments (as of January 1, 2020)

- 5,631 involuntary commitments overturned, thus preventing unnecessary hospitalizations representing a saving of $30,407,400 to the state

- Since program inception, >40% of ED patients who received telepsychiatry services were discharged to home

- 32% of the patients served had no insurance coverage

- Currently, the average consult elapsed time (in queue to consult complete) is 3 hours 9 minutes.

For more information about this program, see www.ecu.edu/cs-dhs/ncstep.

Our practice has extensive experience with telepsychiatry (Box 3), and for us, the specific costs associated with providing telepsychiatry services include maintenance of infrastructure and the purchase of hardware (eg, computers, smartphones, tablets), a video conferencing application (some free versions are available), EHR systems, and Internet access.

Box 3

Our practice (Rural Psychiatry Associates, Grand Forks, North Dakota) and our close associates have provided telepsychiatry services to >200 mental health clinics, hospitals, Native American villages, prisons, and nursing homes, mostly in rural and underserved areas. To provide these services, in addition to physicians, we also utilize nurse practitioners and physician assistants, for whom we provide extensive education, training, and supervision. We also provide education to the staff at the facilities where we provide services.

For nursing homes, we often use what is referred to as a “blended mode,” where we combine telepsychiatry visits with in-person, on-site visits, alternating monthly. In this model, we also typically alternate one physician with one nonphysician clinician at each facility. For continuity of care, the same clinicians service the same facilities. For very distant facilities with only a few patients, only telepsychiatry is utilized. However, initial services are always provided by a physician to establish a relationship, discuss policies and procedures, and evaluate patients face-to-face.

Telepsychiatry is increasingly used for education and mentoring. We have found telepsychiatry to be especially useful when working with psychiatric residents on a realtime basis as they evaluate and treat patients at a different location.

Reimbursement for telepsychiatry

Private insurance reimbursement for treatment delivered via telepsychiatry obviously depends on the specific insurance company. Some facilities, such as nursing homes, hospitals, medical clinics, and correctional facilities, offer lump-sum fees to clinicians for providing contracted services. Some clinicians are providing telepsychiatry as direct-bill or concierge services, which require direct payment from the patient without any reimbursement from insurance.

Medicare Part B covers some telepsychiatry services, but only under certain conditions.28 Previously, reimbursement was limited to services provided to patients who live in rural areas. However, on November 1, 2019, eligibility for telehealth services for Medicare Advantage (MA) recipients was expanded to include patients in both urban and rural locations. Patients covered by MA also can receive telehealth services from their home, instead of having to drive to a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services–qualified telehealth service center.

Continue to: Medicaid is the single...

Medicaid is the single largest payer for mental health services in the United States,29 and all Medicaid programs reimburse for some telepsychiatry services. As with all Medicaid health care, fees paid for telepsychiatry are state-specific. Since 2013, several state Medicaid programs, including New York,30 have expanded the list of eligible telehealth sites to include schools, thereby giving children virtual access to mental health clinicians.

Getting started

Clinicians who are interested in starting to provide treatment via telepsychiatry can begin by reviewing the American Psychiatric Association’s Telepsychiatry Toolkit at www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit. This toolkit, which is being continually updated, features numerous training videos for clinicians new to telepsychiatry, such as Learning To Do Telemental Health (www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/learning-telemental-health) and The Credentialing Process (www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/credentialing-process). Before starting, also consider reviewing the steps listed in Table 2.

Bottom Line

Evidence suggests telepsychiatry can be beneficial for a wide range of patient populations and settings. Most patients accept its use, and some actually prefer it to face-to-face care. Telepsychiatry may be especially useful for patients who have limited access to psychiatric treatment, such as those who live in rural areas. Factors to consider before incorporating telepsychiatry into your practice include addressing various legal, technological, and financial requirements.

Related Resources

- Von Hafften A. Telepsychiatry practice guidelines. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/practice-guidelines.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Telehealth and telemedicine: a research anthology of law and policy resources. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/anthologies/anthologies-telehealth.html. Reviewed July 31, 2019.

- American Telemedicine Association. https://www.americantelemed.org/.

The need for mental health services has never been greater. Unfortunately, many patients have limited access to psychiatric treatment, especially those who live in rural areas. Telepsychiatry—the delivery of psychiatric services through telecommunications technology, usually video conferencing—may help address this problem. Even before the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, telepsychiatry was becoming increasingly common. A survey of US mental health facilities found that the proportion of facilities offering telepsychiatry nearly doubled from 2010 to 2017, from 15.2% to 29.2%.1

In this article, we describe examples of where and how telepsychiatry is being used successfully, and its potential advantages. We discuss concerns about its use, its impact on the therapeutic alliance, and patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of it. We also discuss the legal, technological, and financial aspects of using telepsychiatry. With an increased understanding of these issues, psychiatric clinicians will be better able to integrate telepsychiatry into their practices.

How and where is telepsychiatry being used

In addition to being used to provide psychotherapy, telepsychiatry is being employed for diagnosis and evaluation; clinical consultations; research; supervision, mentoring, and education of trainees; development of treatment programs; and public health. Telepsychiatry is an excellent mechanism to provide high-level second opinions to primary care physicians and psychiatrists on complex cases for both diagnostic purposes and treatment.

Evidence suggests that telepsychiatry can play a beneficial role in a variety of settings, and for a range of patient populations.

Emergency departments (EDs). Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in EDs could result in a quicker disposition of patients and reduced crowding and wait times. A survey of on-call clinicians in a pediatric ED found that using telepsychiatry for on-site psychiatric consultations decreased patients’ length of stay, improved resident on-call burden, and reduced factors related to physician burnout.2 In this study, telepsychiatry use reduced travel for face-to-face evaluations by 75% and saved more than 2 hours per call day.2

Medical clinics. Using telepsychiatry to deliver cognitive-behavioral therapy significantly reduced symptoms of depression or anxiety among 203 primary care patients.3 Incorporating telepsychiatry into existing integrated primary care settings is becoming more common. For example, an integrated-care model that includes telepsychiatry is serving the needs of complex patients in a high-volume, urban primary care clinic in Colorado.4

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams. Telepsychiatry is being used by ACT teams for crisis intervention and to reduce inpatient hospitalizations.5

Continue to: Correctional facilities

Correctional facilities. With the downsizing and closure of many state psychiatric hospitals across the United States over the last several decades, jails and prisons have become de facto mental health hospitals. This situation presents many challenges, including access to mental health care and the need to avoid medications with the potential for abuse. Using telepsychiatry for psychiatric consultations in correctional facilities can improve access to mental health care.

Geriatric patients.

Children and adolescents. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) program is a telepsychiatry consultation service that has been able to provide cost-effective, timely, remote consultation to primary care clinicians who care for youth and perinatal women.8 New York has a pediatric collaborative care program, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for Primary Care (CAP PC), that incorporates telepsychiatry consultations for families who live >1 hour away from one of the program’s treatment sites.9

Patients with cancer. A literature review that included 9 studies found no statistically significant differences between standard face-to-face interventions and telepsychiatry for improving quality-of-life scores among patients receiving treatment for cancer.10

Patients with insomnia. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is often recommended as a first-line treatment, but is not available for many patients. A recent study showed that CBT-I provided via telepsychiatry for patients with shift work sleep disorder was as effective as face-to-face therapy.11 Increasing the availability of this treatment could decrease reliance on pharmacotherapy for sleep.

Patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Treatment for patients with OUD is limited by access to, and availability of, psychiatric clinicians. Telepsychiatry can help bridge this gap. One example of such use is in Ontario, Canada, where more than 10,000 patients with concurrent opiate abuse and other mental health disorders have received care via telepsychiatry since 2008.12

Continue to: Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

Increasing access to cost-effective care where it is needed most

There is a crisis in mental health care in rural areas of the United States. A study assessing delivery of care to US residents who live in rural areas found these patients’ mental health–related quality of life was 2.5 standard deviations below the national mean.13 Additionally, the need for treatment is expected to rise as the number of psychiatrists falls. According to a 2017 National Council for Behavioral Health report,14 by 2025, demand may outstrip supply by 6,090 to 15,600 psychiatrists. While telepsychiatry cannot improve this shortage per se, it can help increase access to psychiatric services. The potential benefits of telepsychiatry for patients are summarized in Table 1.15

Telepsychiatry may be more cost-effective than traditional face-to-face treatment. A cost analysis of an expanding, multistate behavioral telehealth intervention program for rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations found substantial cost savings associated with telepsychiatry.16 In this analysis, the estimated cost efficiencies of telepsychiatry were more evident in rural communities, and having a multistate center was less expensive than each state operating independently.16

Most importantly, evidence suggests that treatment delivered via telepsychiatry is at least as effective as traditional face-to-face care. In a review that included >150 studies, Bashshur et al17 concluded, “Effective approaches to the long-term management of mental illness include monitoring, surveillance, mental health promotion, mental illness prevention, and biopsychosocial treatment programs. The empirical evidence … demonstrates the capability of [telepsychiatry] to perform these functions more efficiently and as well as or more effectively than in-person care

Clinician and patient attitudes toward telepsychiatry

Clinicians have legitimate concerns about the quality of care being delivered when using telepsychiatry. Are patients satisfied with treatment delivered via telepsychiatry? Can a therapeutic alliance be established and maintained? It appears that clinicians may have more concerns than patients do.18

A study of telepsychiatry consultations for patients in rural primary care clinics performed by clinicians at an urban health center found that patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with telepsychiatry.19 Both patients and clinicians believed that telepsychiatry provided patients with better access to care. There was a high degree of agreement between patients and clinician responses.19

Continue to: In a review of...

In a review of 452 telepsychiatry studies, Hubley et al20 focused on satisfaction, reliability, treatment outcomes, implementation outcomes, cost effectiveness, and legal issues. They concluded that patients and clinicians are generally satisfied with telepsychiatry services. Interestingly, clinicians expressed more concerns about the potential adverse effects of telepsychiatry on therapeutic rapport. Hubley et al20 found no published reports of adverse events associated with telepsychiatry use.

In a study of school-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting, Mayworm et al21 found that patients were highly satisfied with both in-person and telepsychiatry services, and there were no significant differences in preference. This study also found that telepsychiatry services were more time-efficient than in-person services.

A study of using telepsychiatry to treat unipolar depression found that patient satisfaction scores improved with increasing number of video-based sessions, and were similar among all age groups.22 An analysis of this study found that total satisfaction scores were higher for patients than for clinicians.23

In a study of satisfaction with telepsychiatry among community-dwelling older veterans, 90% of participants reported liking or even preferring telepsychiatry, even though the experience was novel for most of them.24

As always, patients’ preferences need to be kept in mind when considering what services can and should be provided via telepsychiatry, because not all patients will find it acceptable. For example, in a study of veterans’ attitudes toward treatment via telepsychiatry, Goetter et al25 found that interest was mixed. Twenty-six percent of patients were “not at all comfortable,” while 13% were “extremely comfortable” using telepsychiatry from home. Notably, 33% indicated a clear preference for telepsychiatry compared to in-person mental health visits.

Continue to: Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Legal aspects of telepsychiatry

Box 1

As part of the efforts to contain the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the use of telemedicine, including telepsychiatry, has increased substantially. Here are a few key facts to keep in mind while practicing telepsychiatry during this pandemic:

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services relaxed requirements for telehealth starting March 6, 2020 and for the duration of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Under this new waiver, Medicare can pay for office, hospital, and other visits furnished via telehealth across the country and including in patient’s places of residence. For details, see www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. This fact sheet reviews relevant information, including billing codes.

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirements, specifically those for secure communications, will not be enforced when telehealth is used under the new waiver. Because of this, popular but unsecure software applications, such as Apple’s FaceTime, Microsoft’s Teams, or Facebook’s Messenger, WhatsApp, and Messenger Rooms, can be used.

- Informed consent for the use of telepsychiatry in this situation should be obtained from the patient or his/her guardian, and documented in the patient’s medical record. For example: “Informed consent received for providing services via video teleconferencing to the home in order to protect the patient from COVID-19 exposure. Confidentiality issues were discussed.”

Licensure. State licensing and medical regulatory organizations consider the care provided via telepsychiatry to be rendered where the patient is physically located when services are rendered. Because of this, psychiatrists who use telepsychiatry generally need to hold a license in the state where their patients are located, regardless of where the psychiatrist is located.

Some states offer special telemedicine licenses. Typically, these licenses allow clinicians to practice across state lines without having to obtain a full professional license from the state. Be sure to check with the relevant state medical board where you intend to practice.

Because state laws related to telepsychiatry are continuously evolving, we suggest that clinicians continually check these laws and obtain a regulatory response in writing so there is ongoing documentation. For more information on this topic, see “Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: Understanding the rules” at MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Malpractice insurance. Some insurance companies offer coverage that includes the practice of telepsychiatry, whereas other carriers require the purchase of additional coverage for telepsychiatry. There may be additional requirements for practicing across state lines. Be sure to check with your insurer.

Continue to: Technical requirements and costs

Technical requirements and costs

In order to perform telepsychiatry, one needs Internet access, appropriate hardware such as a desktop or laptop computer or tablet, and a video conferencing application. Software must be HIPAA-compliant, although this requirement is not being enforced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Several popular video conferencing platforms were designed for or have versions suitable for telemedicine, including Zoom, Doxy.me, Vidyo, and Skype.

The use of different electronic health record (EHR) systems by various health care systems is a barrier to using telepsychiatry.

Box 2

The North Carolina Statewide Telepsychiatry Program (NC-STeP) began in 2013 by providing telepsychiatry services in hospital emergency departments (EDs) to individuals experiencing an acute behavioral health crisis. In 2018, the program expanded to include community-based primary care sites using a “hybrid” collaborative-care model. This model benefits patients by improving access to mental health specialty care; reducing the need for trips to the ED and inpatient admissions, thus decompressing EDs; improving compliance with treatment; reducing delays in care; reducing stigma; and improving continuity of care and follow-up. East Carolina University’s Center for Telepsychiatry and E-Behavioral Health is the home for this program, which is connecting hospital EDs and community-based primary care sites across North Carolina.

NC-STeP provides patients with a faceto-face interaction with a clinician through real-time video conferencing that is facilitated using mobile carts and desktop units. A web portal combines scheduling, electronic medical records, health information exchange functions, and data management systems.

NC-STeP has significantly reduced patient length of stay in EDs, provided cost savings to the health care delivery system through overturned involuntary commitments, improved ED throughout, and reduced patient boarding time; and has achieved high rates of patient, staff, and clinician satisfaction. Highlights of the program include:

- 57 hospitals and 8 communitybased sites in the network (as of January 1, 2020)

- 8 clinical hubs are operational, with 53 consultant clinicians

- 40,573 telepsychiatry assessments (as of January 1, 2020)

- 5,631 involuntary commitments overturned, thus preventing unnecessary hospitalizations representing a saving of $30,407,400 to the state

- Since program inception, >40% of ED patients who received telepsychiatry services were discharged to home

- 32% of the patients served had no insurance coverage

- Currently, the average consult elapsed time (in queue to consult complete) is 3 hours 9 minutes.

For more information about this program, see www.ecu.edu/cs-dhs/ncstep.

Our practice has extensive experience with telepsychiatry (Box 3), and for us, the specific costs associated with providing telepsychiatry services include maintenance of infrastructure and the purchase of hardware (eg, computers, smartphones, tablets), a video conferencing application (some free versions are available), EHR systems, and Internet access.

Box 3

Our practice (Rural Psychiatry Associates, Grand Forks, North Dakota) and our close associates have provided telepsychiatry services to >200 mental health clinics, hospitals, Native American villages, prisons, and nursing homes, mostly in rural and underserved areas. To provide these services, in addition to physicians, we also utilize nurse practitioners and physician assistants, for whom we provide extensive education, training, and supervision. We also provide education to the staff at the facilities where we provide services.

For nursing homes, we often use what is referred to as a “blended mode,” where we combine telepsychiatry visits with in-person, on-site visits, alternating monthly. In this model, we also typically alternate one physician with one nonphysician clinician at each facility. For continuity of care, the same clinicians service the same facilities. For very distant facilities with only a few patients, only telepsychiatry is utilized. However, initial services are always provided by a physician to establish a relationship, discuss policies and procedures, and evaluate patients face-to-face.

Telepsychiatry is increasingly used for education and mentoring. We have found telepsychiatry to be especially useful when working with psychiatric residents on a realtime basis as they evaluate and treat patients at a different location.

Reimbursement for telepsychiatry

Private insurance reimbursement for treatment delivered via telepsychiatry obviously depends on the specific insurance company. Some facilities, such as nursing homes, hospitals, medical clinics, and correctional facilities, offer lump-sum fees to clinicians for providing contracted services. Some clinicians are providing telepsychiatry as direct-bill or concierge services, which require direct payment from the patient without any reimbursement from insurance.

Medicare Part B covers some telepsychiatry services, but only under certain conditions.28 Previously, reimbursement was limited to services provided to patients who live in rural areas. However, on November 1, 2019, eligibility for telehealth services for Medicare Advantage (MA) recipients was expanded to include patients in both urban and rural locations. Patients covered by MA also can receive telehealth services from their home, instead of having to drive to a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services–qualified telehealth service center.

Continue to: Medicaid is the single...

Medicaid is the single largest payer for mental health services in the United States,29 and all Medicaid programs reimburse for some telepsychiatry services. As with all Medicaid health care, fees paid for telepsychiatry are state-specific. Since 2013, several state Medicaid programs, including New York,30 have expanded the list of eligible telehealth sites to include schools, thereby giving children virtual access to mental health clinicians.

Getting started

Clinicians who are interested in starting to provide treatment via telepsychiatry can begin by reviewing the American Psychiatric Association’s Telepsychiatry Toolkit at www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit. This toolkit, which is being continually updated, features numerous training videos for clinicians new to telepsychiatry, such as Learning To Do Telemental Health (www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/learning-telemental-health) and The Credentialing Process (www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/credentialing-process). Before starting, also consider reviewing the steps listed in Table 2.

Bottom Line

Evidence suggests telepsychiatry can be beneficial for a wide range of patient populations and settings. Most patients accept its use, and some actually prefer it to face-to-face care. Telepsychiatry may be especially useful for patients who have limited access to psychiatric treatment, such as those who live in rural areas. Factors to consider before incorporating telepsychiatry into your practice include addressing various legal, technological, and financial requirements.

Related Resources

- Von Hafften A. Telepsychiatry practice guidelines. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/telepsychiatry/toolkit/practice-guidelines.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Telehealth and telemedicine: a research anthology of law and policy resources. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/anthologies/anthologies-telehealth.html. Reviewed July 31, 2019.

- American Telemedicine Association. https://www.americantelemed.org/.

1. Spivak S, Spivak A, Cullen B, et al. Telepsychiatry use in U.S. mental health facilities, 2010-2017. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;71(2):appips201900261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900261.

2. Reliford A, Adebanjo B. Use of telepsychiatry in pediatric emergency room to decrease length of stay for psychiatric patients, improve resident on-call burden, and reduce factors related to physician burnout. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(9):828-832.

3. Mathiasen K, Riper H, Andersen TE, et al. Guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for adult depression and anxiety in routine secondary care: observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e10927. doi: 10.2196/10927.

4. Waugh M, Calderone J, Brown Levey S, et al. Using telepsychiatry to enrich existing integrated primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(8):762-768.

5. Swanson CL, Trestman RL. Rural assertive community treatment and telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(4):269-273.

6. Gentry MT, Lapid MI, Rummans TA. Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):109-127.

7. Christensen LF, Moller AM, Hansen JP, et al. Patients’ and providers’ experiences with video consultations used in the treatment of older patients with unipolar depression: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020;27(3):258-271.

8. Marcus S, Malas N, Dopp R, et al. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care program: building a telepsychiatry consultation service. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):849-852.

9. Kaye DL, Fornari V, Scharf M, et al. Description of a multi-university education and collaborative care child psychiatry access program: New York State’s CAP PC. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:32-36.

10. Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(6):397-405.

11. Peter L, Reindl R, Zauter S, et al. Effectiveness of an online CBT-I intervention and a face-to-face treatment for shift work sleep disorder: a comparison of sleep diary data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):E3081. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173081.

12. LaBelle B, Franklyn AM, Pkh Nguyen V, et al. Characterizing the use of telepsychiatry for patients with opioid use disorder and cooccurring mental health disorders in Ontario, Canada. Int J Telemed Appl. 2018;2018(3):1-7.

13. Fortney JC, Heagerty PJ, Bauer AM, et al. Study to promote innovation in rural integrated telepsychiatry (SPIRIT): rationale and design of a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of managing complex psychiatric disorders in rural primary care clinics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;90:105873. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105873.

14. Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage. Published February 12, 2018. Accessed May 14, 2020.

15. American Psychiatric Association. What is telepsychiatry? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-telepsychiatry. Published 2017. Accessed May 14, 2020.

16. Yilmaz SK, Horn BP, Fore C, et al. An economic cost analysis of an expanding, multi-state behavioural telehealth intervention. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(6):353-364.

17. Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Bashshur N, et al. The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in mental disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87-113.

18. Lopez A, Schwenk S, Schneck CD, et al. Technology-based mental health treatment and the impact on the therapeutic alliance. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(8):76.

19. Schubert NJ, Backman PJ, Bhatla R, et al. Telepsychiatry and patient-provider concordance. Can J Rural Med. 2019;24(3):75-82.

20. Hubley S, Lynch SB, Schneck C, et al. Review of key telepsychiatry outcomes. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(2):269-282.

21. Mayworm AM, Lever N, Gloff N, et al. School-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting: efficiency and satisfaction with care. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(4):446-454.

22. Christensen LF, Gildberg FA, Sibbersen C, et al. Videoconferences and treatment of depression: satisfaction score correlated with number of sessions attended but not with age [published online October 31, 2019]. Telemed J E Health. 2019. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0129.

23. Christensen LF, Gildberg FA, Sibbersen C, et al. Disagreement in satisfaction between patients and providers in the use of videoconferences by depressed adults. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(5):614-620.

24. Hantke N, Lajoy M, Gould CE, et al. Patient satisfaction with geriatric psychiatry services via video teleconference. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(4):491-494.

25. Goetter EM, Blackburn AM, Bui E, et al. Veterans’ prospective attitudes about mental health treatment using telehealth. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2019;57(9):38-43.

26. Vanderpool D. Top 10 myths about telepsychiatry. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14(9-10):13-15.

27. Butterfield A. Telepsychiatric evaluation and consultation in emergency care settings. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):467-478.

28. Medicare.gov. Telehealth. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/telehealth. Accessed May 14, 2020.

29. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Behavioral Health Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/bhs/index.html. Accessed May 14, 2020.

30. New York Pub Health Law §2999-cc (2017).

1. Spivak S, Spivak A, Cullen B, et al. Telepsychiatry use in U.S. mental health facilities, 2010-2017. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;71(2):appips201900261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900261.

2. Reliford A, Adebanjo B. Use of telepsychiatry in pediatric emergency room to decrease length of stay for psychiatric patients, improve resident on-call burden, and reduce factors related to physician burnout. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(9):828-832.

3. Mathiasen K, Riper H, Andersen TE, et al. Guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for adult depression and anxiety in routine secondary care: observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e10927. doi: 10.2196/10927.

4. Waugh M, Calderone J, Brown Levey S, et al. Using telepsychiatry to enrich existing integrated primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(8):762-768.

5. Swanson CL, Trestman RL. Rural assertive community treatment and telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(4):269-273.

6. Gentry MT, Lapid MI, Rummans TA. Geriatric telepsychiatry: systematic review and policy considerations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(2):109-127.

7. Christensen LF, Moller AM, Hansen JP, et al. Patients’ and providers’ experiences with video consultations used in the treatment of older patients with unipolar depression: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2020;27(3):258-271.

8. Marcus S, Malas N, Dopp R, et al. The Michigan Child Collaborative Care program: building a telepsychiatry consultation service. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):849-852.

9. Kaye DL, Fornari V, Scharf M, et al. Description of a multi-university education and collaborative care child psychiatry access program: New York State’s CAP PC. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;48:32-36.

10. Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(6):397-405.

11. Peter L, Reindl R, Zauter S, et al. Effectiveness of an online CBT-I intervention and a face-to-face treatment for shift work sleep disorder: a comparison of sleep diary data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(17):E3081. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16173081.

12. LaBelle B, Franklyn AM, Pkh Nguyen V, et al. Characterizing the use of telepsychiatry for patients with opioid use disorder and cooccurring mental health disorders in Ontario, Canada. Int J Telemed Appl. 2018;2018(3):1-7.

13. Fortney JC, Heagerty PJ, Bauer AM, et al. Study to promote innovation in rural integrated telepsychiatry (SPIRIT): rationale and design of a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of managing complex psychiatric disorders in rural primary care clinics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;90:105873. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105873.

14. Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage. Published February 12, 2018. Accessed May 14, 2020.

15. American Psychiatric Association. What is telepsychiatry? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-telepsychiatry. Published 2017. Accessed May 14, 2020.

16. Yilmaz SK, Horn BP, Fore C, et al. An economic cost analysis of an expanding, multi-state behavioural telehealth intervention. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;25(6):353-364.

17. Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Bashshur N, et al. The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in mental disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87-113.

18. Lopez A, Schwenk S, Schneck CD, et al. Technology-based mental health treatment and the impact on the therapeutic alliance. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(8):76.

19. Schubert NJ, Backman PJ, Bhatla R, et al. Telepsychiatry and patient-provider concordance. Can J Rural Med. 2019;24(3):75-82.

20. Hubley S, Lynch SB, Schneck C, et al. Review of key telepsychiatry outcomes. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(2):269-282.

21. Mayworm AM, Lever N, Gloff N, et al. School-based telepsychiatry in an urban setting: efficiency and satisfaction with care. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(4):446-454.

22. Christensen LF, Gildberg FA, Sibbersen C, et al. Videoconferences and treatment of depression: satisfaction score correlated with number of sessions attended but not with age [published online October 31, 2019]. Telemed J E Health. 2019. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0129.

23. Christensen LF, Gildberg FA, Sibbersen C, et al. Disagreement in satisfaction between patients and providers in the use of videoconferences by depressed adults. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(5):614-620.

24. Hantke N, Lajoy M, Gould CE, et al. Patient satisfaction with geriatric psychiatry services via video teleconference. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(4):491-494.

25. Goetter EM, Blackburn AM, Bui E, et al. Veterans’ prospective attitudes about mental health treatment using telehealth. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2019;57(9):38-43.

26. Vanderpool D. Top 10 myths about telepsychiatry. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14(9-10):13-15.

27. Butterfield A. Telepsychiatric evaluation and consultation in emergency care settings. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):467-478.

28. Medicare.gov. Telehealth. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/telehealth. Accessed May 14, 2020.

29. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Behavioral Health Services. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/bhs/index.html. Accessed May 14, 2020.

30. New York Pub Health Law §2999-cc (2017).

Which risk factors and signs and symptoms are associated with coccidioidomycosis?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Risk factors for coccidioidomycosis, or valley fever, include lower respiratory tract symptoms lasting longer than 14 days, chest pain, rash, having lived in endemic areas fewer than 10 years, and diabetes mellitus or immunosuppressive conditions (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, several prospective cohort and case-control studies).

The most common signs and symptoms include cough (74%), fever (56%), night sweats (35%), pleuritic chest pain (33%), chills (28%), dyspnea (27%), weight loss (21%), and rash (14%) (SOR: B, retrospective cohort study).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 surveillance report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that included 111,717 patients in 28 states and the District of Columbia found an 8-fold increase in reported coccidioidomycosis in endemic areas from 1998 to 2011 (age-adjusted incidence rates: 5.3 per 100,000 in 1998 and 42.6 per 100,000 in 2011). Cases in nonendemic states increased 40-fold in the same time period, from 6 cases to 240.1 The disease is endemic in the southwest United States and northwest Mexico.

Risk factors include persistent symptoms, chest pain, diabetes, immunosuppression