User login

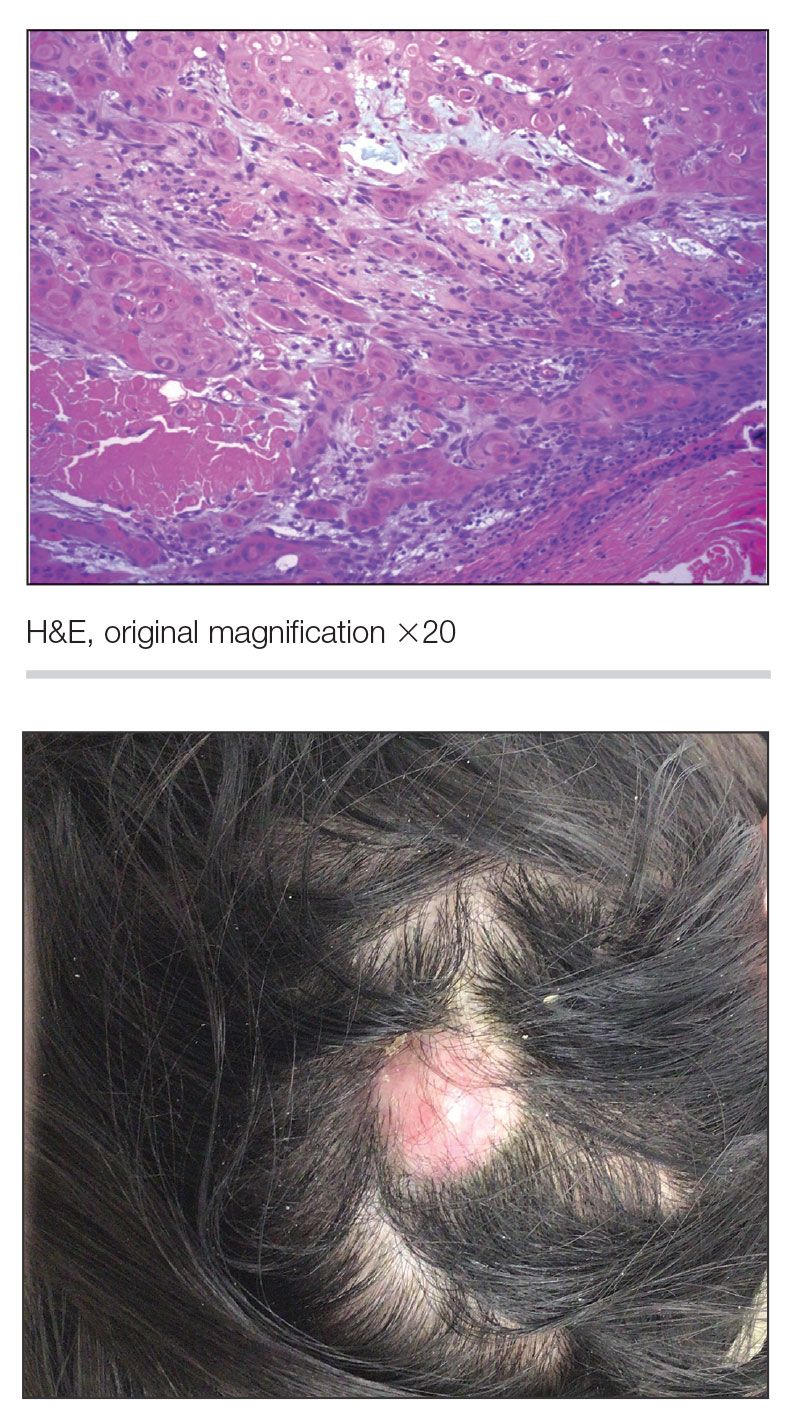

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

THE DIAGNOSIS: Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

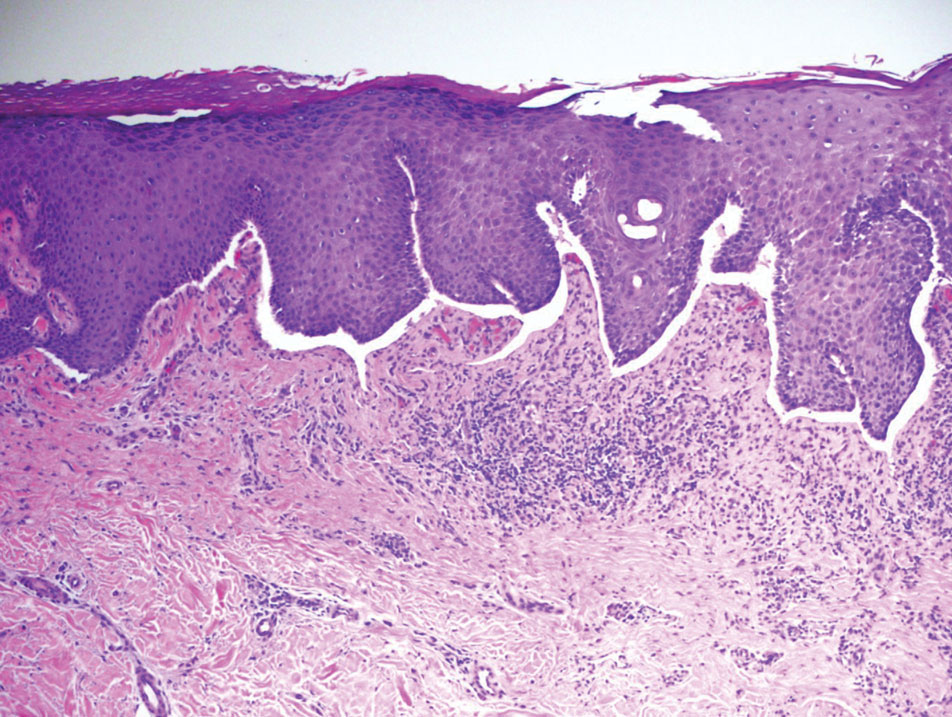

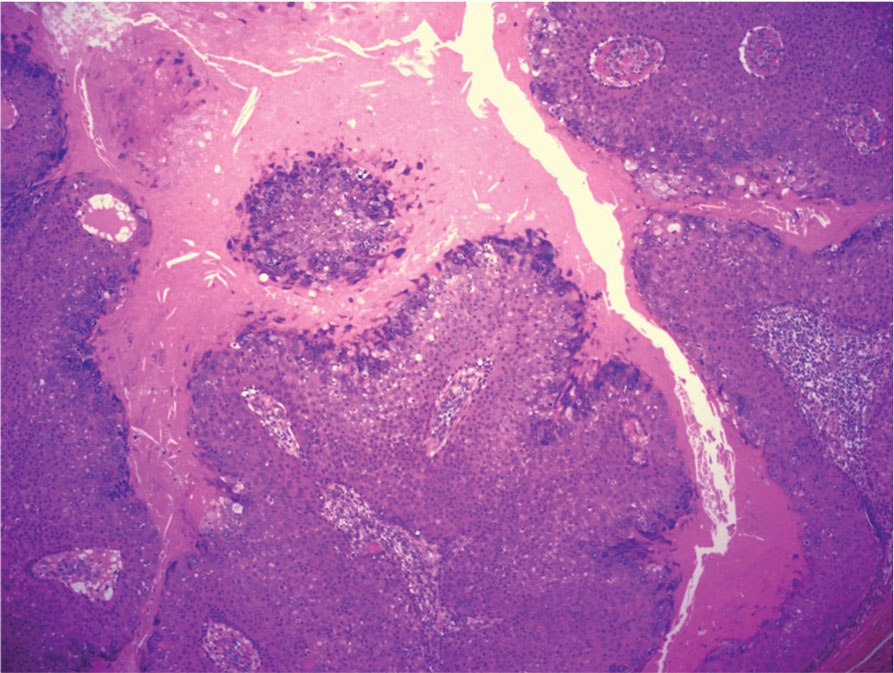

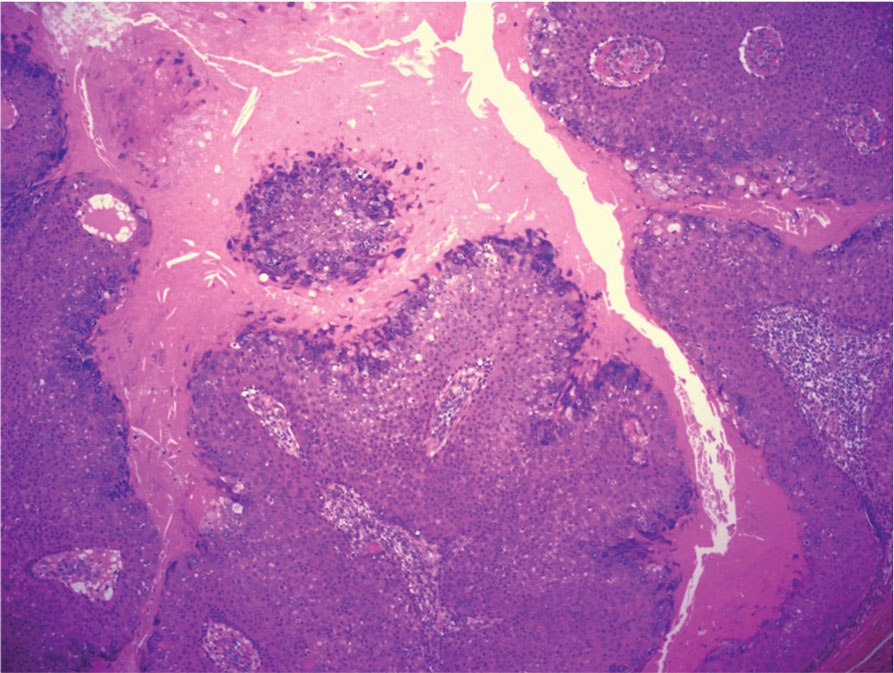

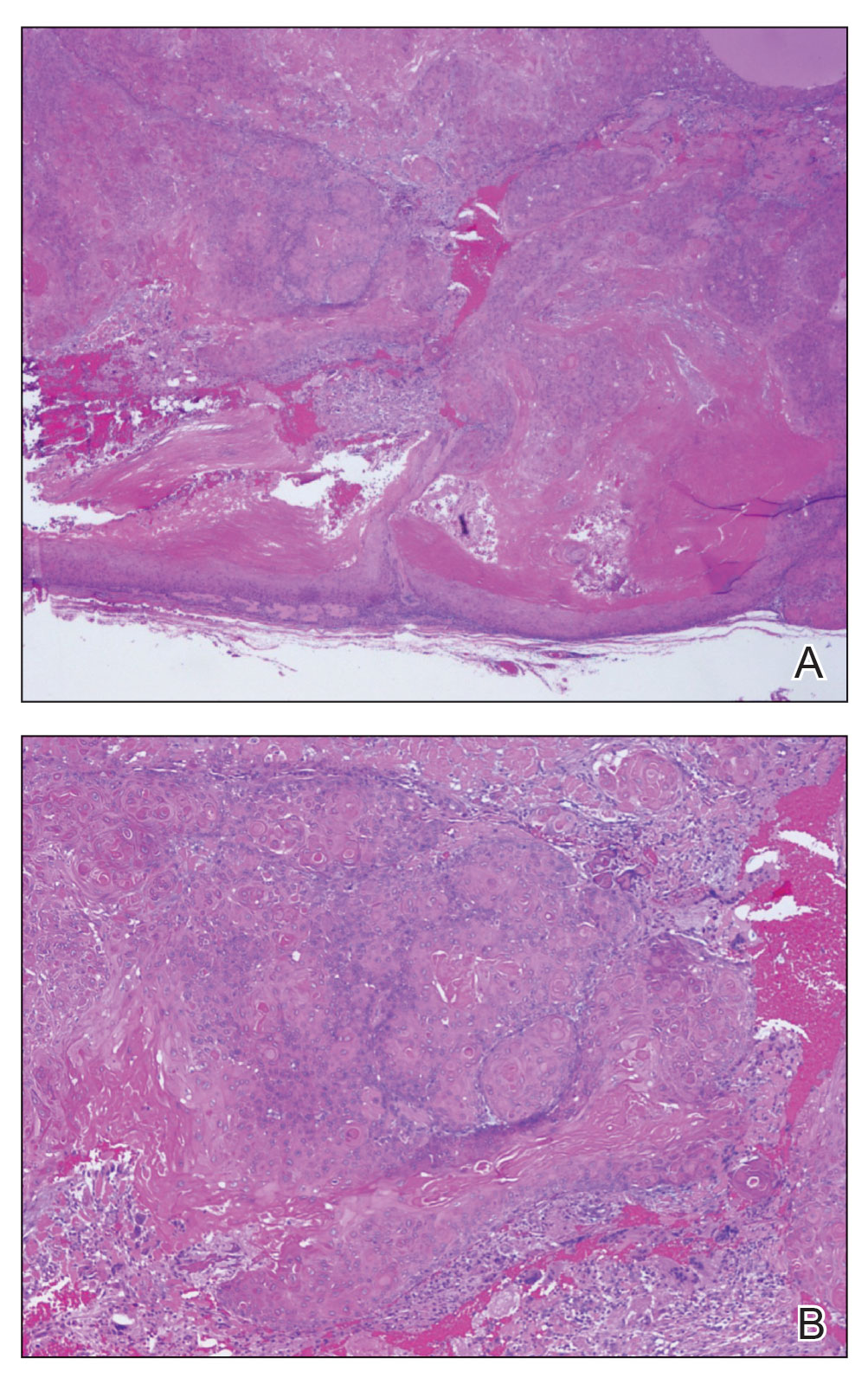

Biopsy revealed a squamous epithelium with cystic changes, trichilemmal differentiation, squamous eddy formation, keratinocyte atypia, focal necrotic changes, and a focus of atypical keratinocytes invading the dermis (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) was made.

Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a rare adnexal tumor that develops from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. It often arises due to malignant transformation of pre-existing trichilemmal cysts, but some cases occur de novo.1 Malignant transformation is thought to start from a trichilemmal cyst in an adenomatous histologic stage, progressing to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (PTC) in an epitheliomatous phase, ultimately becoming carcinomatous with MPTT.2-4 This transformation has been categorized into 3 morphologic groups to predict tumor behavior, including benign PTCs (curable by excision), low-grade malignant PTCs (minor risk for local recurrence), and high-grade malignant PTCs (risk for regional spread and metastasis with cytologic atypical features and potential for aggressive growth).1

More commonly observed in women in the fourth to eighth decades of life, MPTT may manifest as a fast- growing, painless, solitary nodule or as a progressively enlarging nodule at the site of a previously stable, long-standing lesion. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor manifests frequently on the scalp, face, or neck, but there are reports of MPTT manifesting on the trunk and even as multiple concurrent lesions.1-4 The variability in clinical presentation and the potential to be mistaken for benign conditions makes excisional biopsy essential for diagnosis of MPTT. Histopathology classically demonstrates trichilemmal keratinization, a high mitotic index, and cellular atypia with invasion into the dermis.4 Malignant transformation frequently follows a prior history of trauma to the area or local inflammation.

Given the locally aggressive nature of MPTT, our patient was referred to a Mohs micrographic surgeon. While both wide excision with tumor-free margins and Mohs micrographic surgery are accepted surgical procedures for MPTT, there is no consensus in the literature on a standard treatment recommendation. Following surgery, close monitoring is needed for potential recurrence and metastases intracranially to the dura and muscles,5 as well as to the lungs.6 Further imaging using computed tomography or positron emission tomography can be ordered to rule out metastatic disease.4

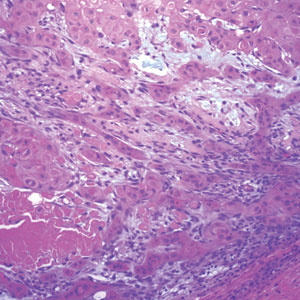

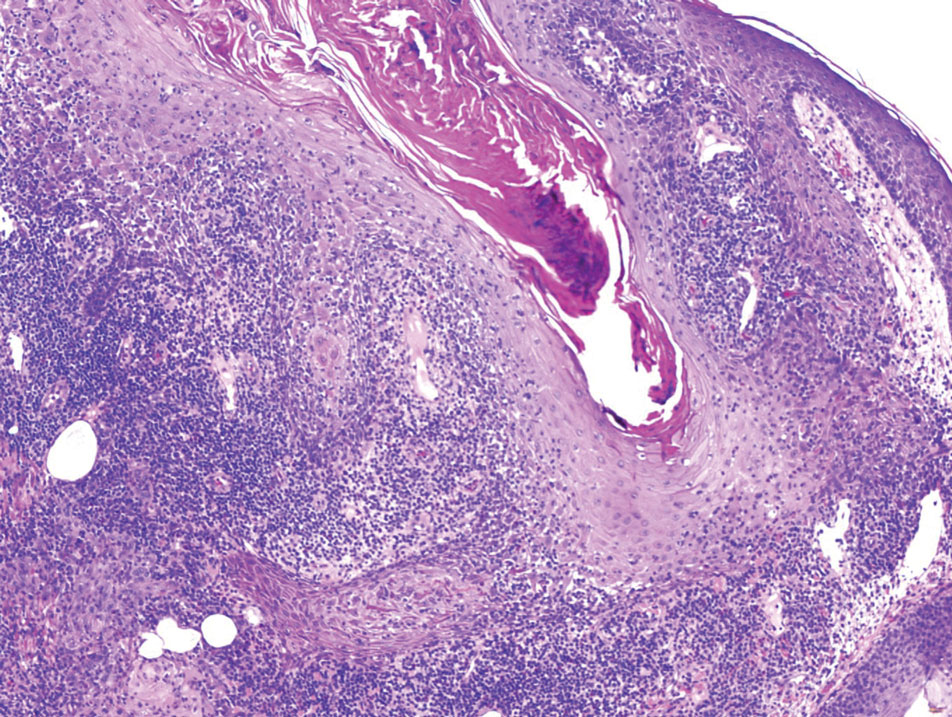

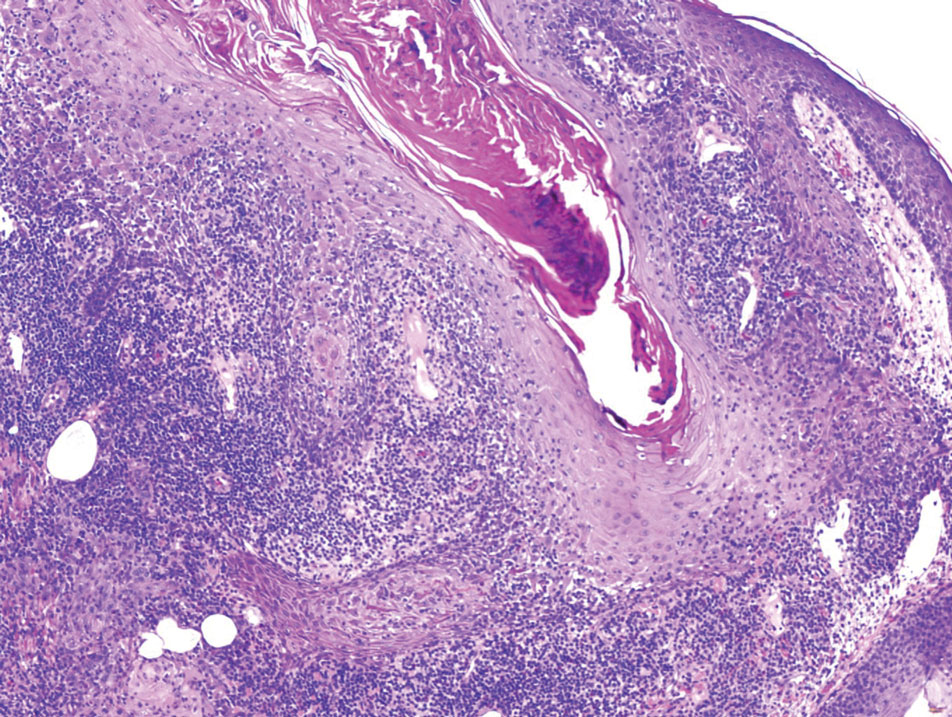

Pilomatrixomas are benign neoplasms that arise from hair matrix cells and have been associated with catenin beta-1 gene mutations, as well as genetic syndromes and trauma.7 Clinically, pilomatrixomas manifest as solitary, firm, painless, slow-growing nodules that commonly are found in the head and neck region. This tumor has a slight predominance in women and occurs frequently in adolescent years. The overlying skin may appear normal or show grey-bluish discoloration.8 Histopathology shows basaloid cells resembling primitive hair matrix cells with an abrupt transition to shadow cells composed of transformed keratinocytes without nuclei and calcification.7-8 This tumor can be differentiated by the presence of basaloid and shadow cells with calcification on histopathology, while MPTT will show atypical, mitotically active squamous cells with trichilemmal keratinization (Figure 2).

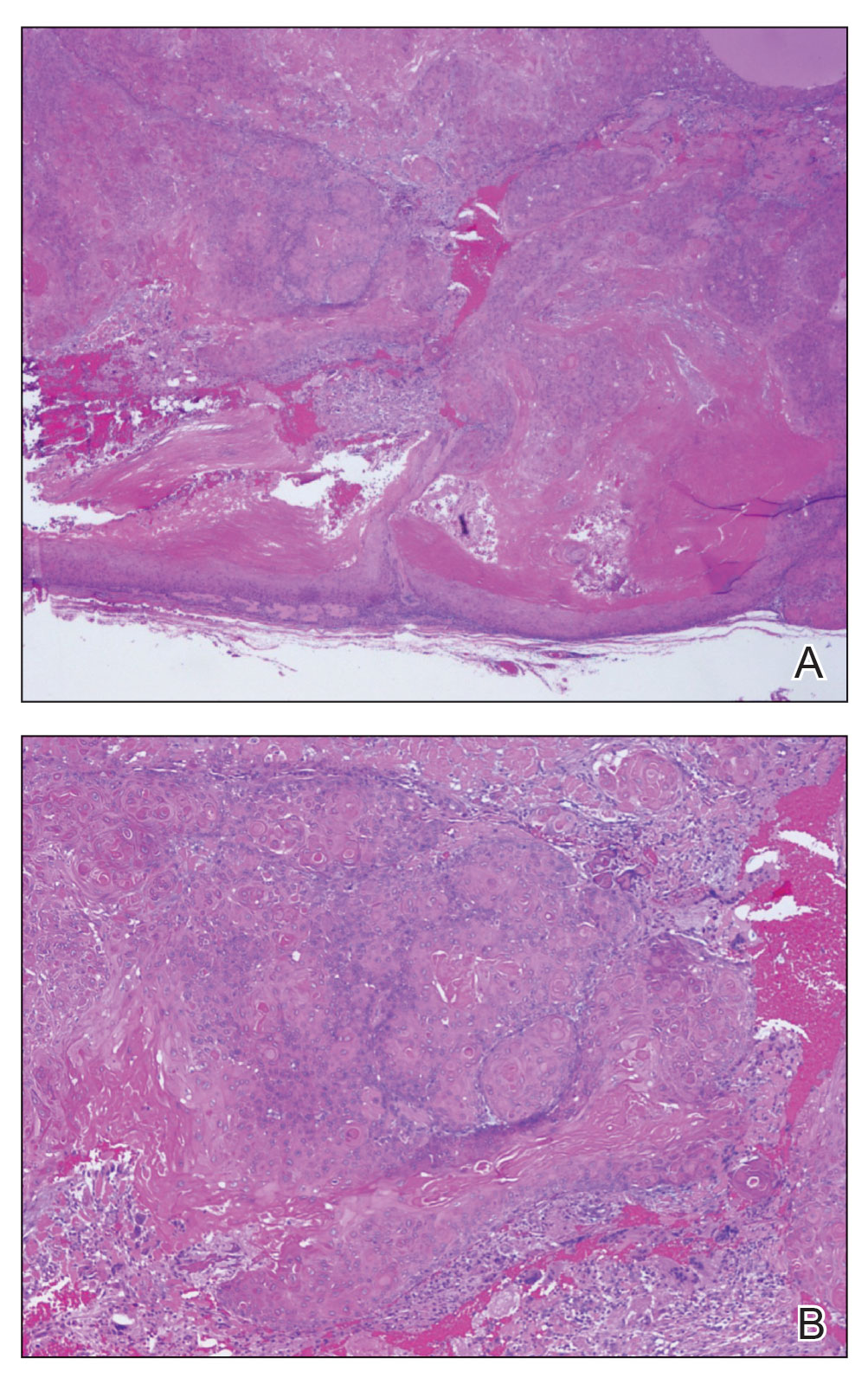

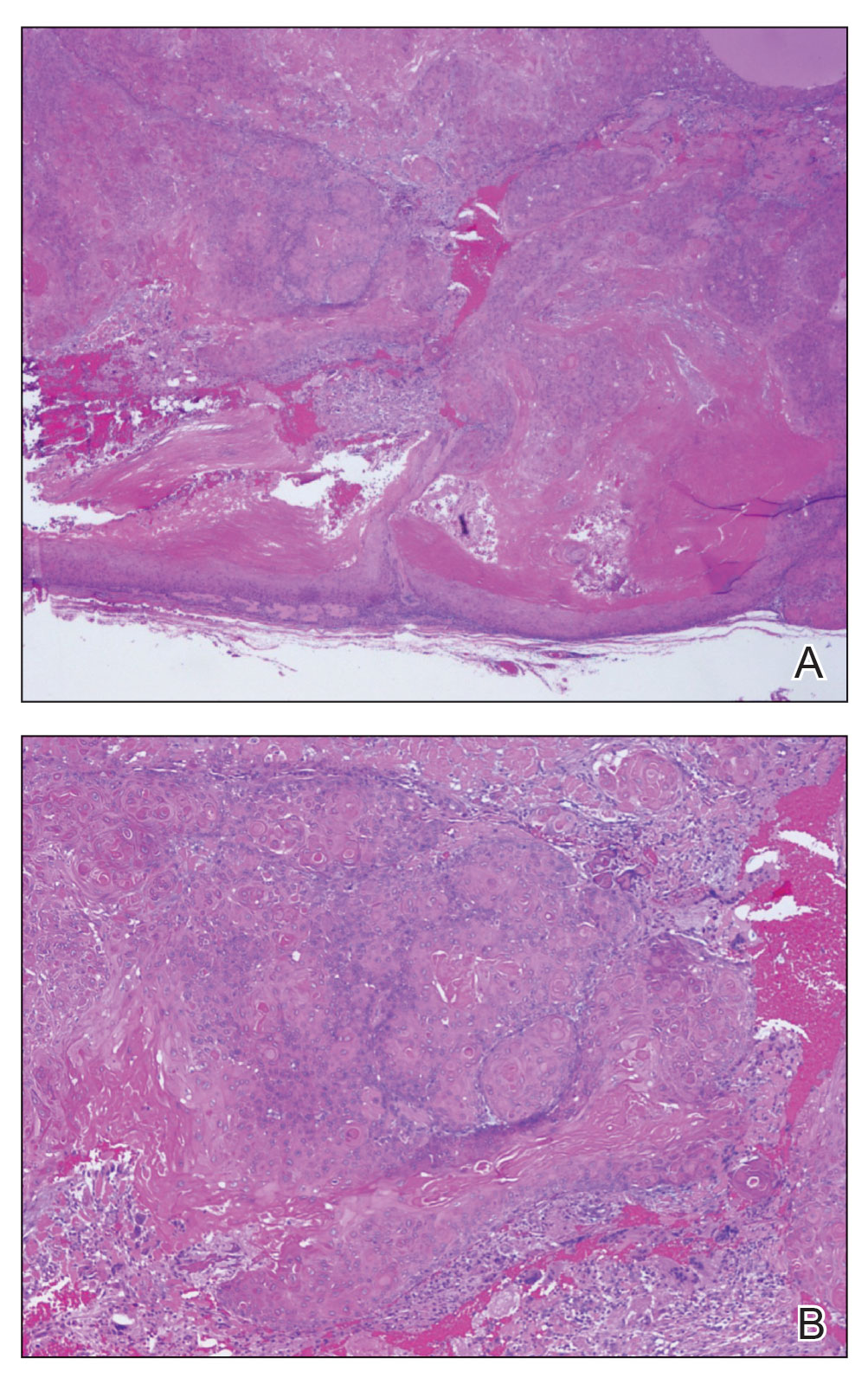

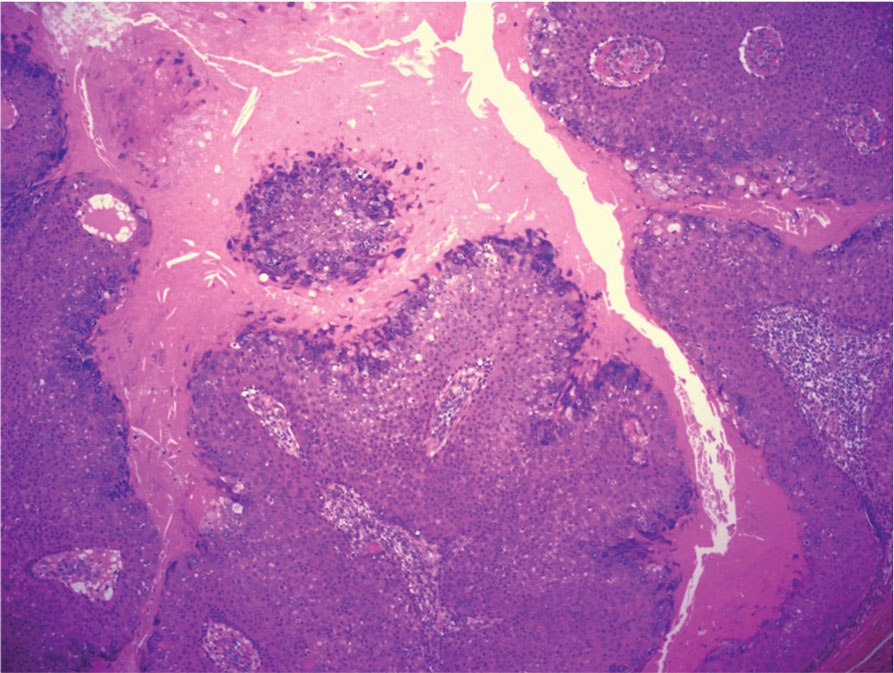

Proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a variant of trichilemmal cyst (TC) arising from the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. While TCs usually are slow growing and benign, the proliferating variant can be more aggressive with malignant potential. Patients often present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, rapidly growing nodule on the scalp. The lesion may be painful, and ulceration can occur, exposing the cystic contents. Histopathologically, PTCs resemble TCs with trichilemmal keratinization but also exhibit notable epithelial proliferation within the cystic space.9 While there can be considerable histopathologic overlap between PTC and MPTT—including extensive trichilemmal keratinization, variable atypia, and mitotic activity—PTC typically should not demonstrate invasion into the surrounding soft tissue or the degree of high-grade atypia, brisk mitoses, or necrosis seen in MPTT (eFigure 1).1 Immunohistochemistry may help distinguish PTC from MPTT and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10-11 The pattern of Ki-67 and p53 expression may be helpful with classification of PTC/MPTT into the 3 groups (benign, low-grade malignant, and high-grade malignant) proposed by Ye et al.1 Other investigators have suggested that Ki-67 expression may correlate potential for recurrence and clinical prognosis.12 Expression of CD34 (a marker that supports outer root sheath origin) might favor PTC/MPTT over SCC; however, cases of CD34- negative MPTT have been reported, particularly those with poorly differentiated histopathology.

Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by cystlike spaces containing malignant squamous epithelial cells.13 Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features can manifest as a firm nodule with ulceration similar to MPTT or PTC but also can mimic a benign cyst.14 The diagnosis of invasive SCC with cystic features typically is straightforward and characterized by cords and nests of atypical keratinocytes extending into the dermis with areas of cystic architecture (eFigure 2). While both SCC with cystic features and MPTT may show cystic histopathologic architecture, MPTT typically shows areas of PTC, whereas SCC with cystic features lacks such areas.

Verrucous cysts refer to infundibular cysts or less commonly pilar cysts or hybrid pilar-epidermoid cysts that exhibit superimposed human papillomavirus (HPV) cytopathic changes. Clinically, a verrucous cyst manifests as a single, asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm lesion most commonly manifesting on the face and back. Histopathologically, the cyst wall may show acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis with coarse keratohyalin granules, and koilocytic changes (eFigure 3). These histopathologic features are believed to be induced by secondary HPV infection. While HPV-related change, characterized by koilocytic alteration, papillomatosis, and verruciform hyperplasia, more commonly affects epidermal cysts, occasionally trichilemmal (pilar) cysts are involved. In these cases, verrucous cysts should be distinguished from MPTT. Verrucous cysts may contain rare normal mitotic figures, but do not contain atypical mitosis, marked cellular pleomorphism, or an infiltrating pattern similar to MPTT.15

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574. doi:10.1309/0XLEGFQ64XYJU4G6

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208. doi:10.1159/000249868

- Rao S, Ramakrishnan R, Kamakshi D, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:51-55. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.79196

- Kearns-Turcotte S, Thériault M, Blouin MM. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors arising in patients with multiple trichilemmal cysts: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:42-46. doi:10.1016

- Karamese M, Akatekin A, Abaci M, et al. Unusual invasion of trichilemmal tumors: two case reports. Modern Plastic Surg. 2012; 2:54-57. doi:10.4236/MPS.2012.23014 /j.jdcr.2022.01.033

- Lobo L, Amonkar AD, Dontamsetty VV. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp with intra-cranial extension and lung metastasis-a case report. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:493-495. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1427-0

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- Sharma D, Agarwal S, Jain LS, et al. Pilomatrixoma masquerading as metastatic adenocarcinoma. A diagnostic pitfall on cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD13-FD14. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9696.5064

- Valerio E, Parro FHS, Macedo MP, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with clinical, radiological, macroscopic, and microscopic orrelation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:452-454. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20198199

- Joshi TP, Marchand S, Tschen J. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor: a subtle presentation in an African American woman and review of immunohistochemical markers for this rare condition. Cureus. 2021;13:E17289. doi:10.7759/cureus.17289

- Gulati HK, Deshmukh SD, Anand M, et al. Low-grade malignant proliferating pilar tumor simulating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an elderly female: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:98-101. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.90818

- Rangel-Gamboa L, Reyes-Castro M, Dominguez-Cherit J, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the value of ki67 immunostaining. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:115-117. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.125599

- Asad U, Alkul S, Shimizu I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with unusual benign-appearing cystic features on histology. Cureus. 2023;15:E33610. doi:10.7759/cureus.33610

- Alkul S, Nguyen CN, Ramani NS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermal inclusion cyst. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2022;35:688-690. doi:10.1080/08998280.2022.207760

- Nanes BA, Laknezhad S, Chamseddin B, et al. Verrucous pilar cysts infected with beta human papillomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:381-386. doi:10.1111/cup.13599

THE DIAGNOSIS: Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

Biopsy revealed a squamous epithelium with cystic changes, trichilemmal differentiation, squamous eddy formation, keratinocyte atypia, focal necrotic changes, and a focus of atypical keratinocytes invading the dermis (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) was made.

Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a rare adnexal tumor that develops from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. It often arises due to malignant transformation of pre-existing trichilemmal cysts, but some cases occur de novo.1 Malignant transformation is thought to start from a trichilemmal cyst in an adenomatous histologic stage, progressing to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (PTC) in an epitheliomatous phase, ultimately becoming carcinomatous with MPTT.2-4 This transformation has been categorized into 3 morphologic groups to predict tumor behavior, including benign PTCs (curable by excision), low-grade malignant PTCs (minor risk for local recurrence), and high-grade malignant PTCs (risk for regional spread and metastasis with cytologic atypical features and potential for aggressive growth).1

More commonly observed in women in the fourth to eighth decades of life, MPTT may manifest as a fast- growing, painless, solitary nodule or as a progressively enlarging nodule at the site of a previously stable, long-standing lesion. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor manifests frequently on the scalp, face, or neck, but there are reports of MPTT manifesting on the trunk and even as multiple concurrent lesions.1-4 The variability in clinical presentation and the potential to be mistaken for benign conditions makes excisional biopsy essential for diagnosis of MPTT. Histopathology classically demonstrates trichilemmal keratinization, a high mitotic index, and cellular atypia with invasion into the dermis.4 Malignant transformation frequently follows a prior history of trauma to the area or local inflammation.

Given the locally aggressive nature of MPTT, our patient was referred to a Mohs micrographic surgeon. While both wide excision with tumor-free margins and Mohs micrographic surgery are accepted surgical procedures for MPTT, there is no consensus in the literature on a standard treatment recommendation. Following surgery, close monitoring is needed for potential recurrence and metastases intracranially to the dura and muscles,5 as well as to the lungs.6 Further imaging using computed tomography or positron emission tomography can be ordered to rule out metastatic disease.4

Pilomatrixomas are benign neoplasms that arise from hair matrix cells and have been associated with catenin beta-1 gene mutations, as well as genetic syndromes and trauma.7 Clinically, pilomatrixomas manifest as solitary, firm, painless, slow-growing nodules that commonly are found in the head and neck region. This tumor has a slight predominance in women and occurs frequently in adolescent years. The overlying skin may appear normal or show grey-bluish discoloration.8 Histopathology shows basaloid cells resembling primitive hair matrix cells with an abrupt transition to shadow cells composed of transformed keratinocytes without nuclei and calcification.7-8 This tumor can be differentiated by the presence of basaloid and shadow cells with calcification on histopathology, while MPTT will show atypical, mitotically active squamous cells with trichilemmal keratinization (Figure 2).

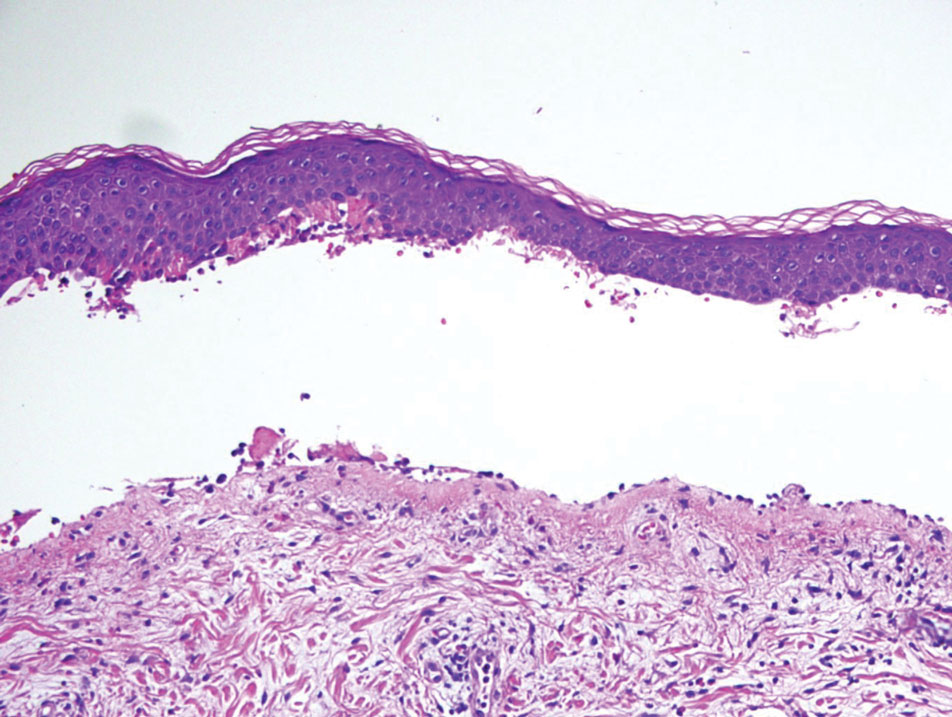

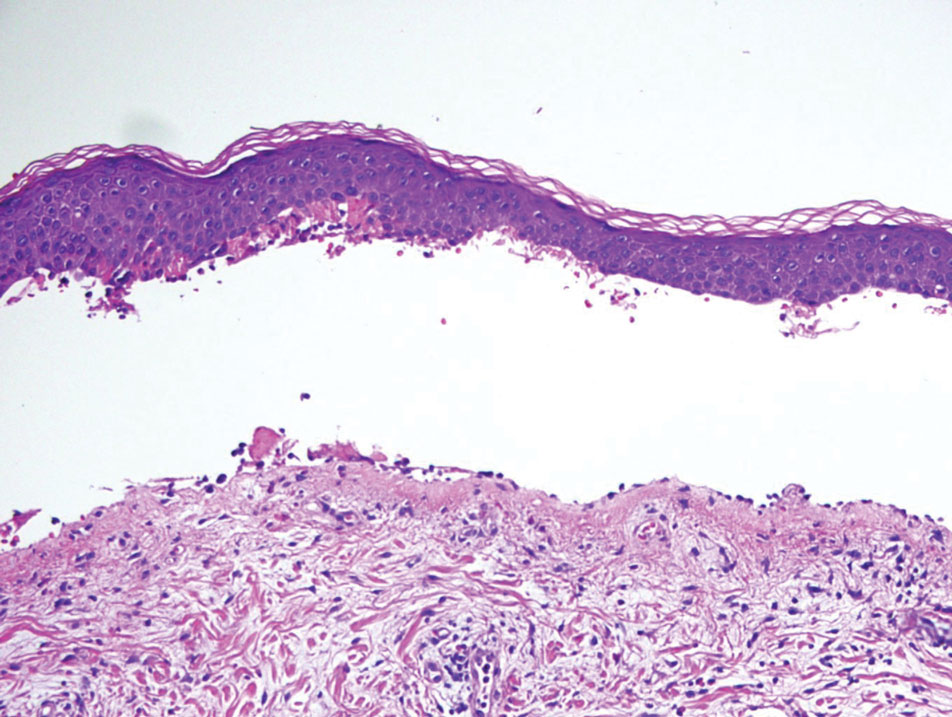

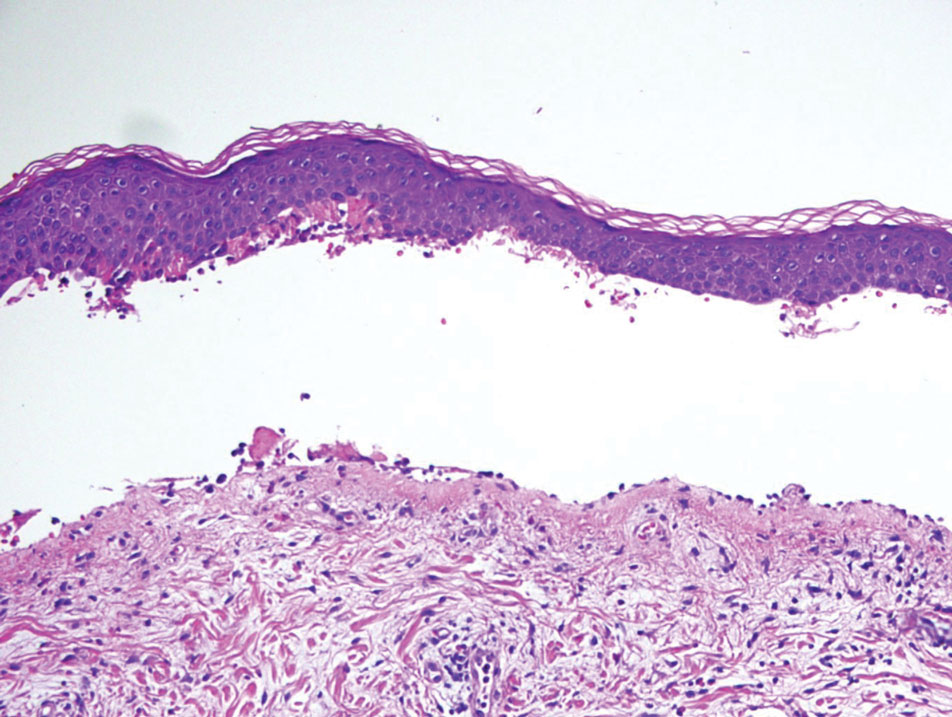

Proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a variant of trichilemmal cyst (TC) arising from the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. While TCs usually are slow growing and benign, the proliferating variant can be more aggressive with malignant potential. Patients often present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, rapidly growing nodule on the scalp. The lesion may be painful, and ulceration can occur, exposing the cystic contents. Histopathologically, PTCs resemble TCs with trichilemmal keratinization but also exhibit notable epithelial proliferation within the cystic space.9 While there can be considerable histopathologic overlap between PTC and MPTT—including extensive trichilemmal keratinization, variable atypia, and mitotic activity—PTC typically should not demonstrate invasion into the surrounding soft tissue or the degree of high-grade atypia, brisk mitoses, or necrosis seen in MPTT (eFigure 1).1 Immunohistochemistry may help distinguish PTC from MPTT and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10-11 The pattern of Ki-67 and p53 expression may be helpful with classification of PTC/MPTT into the 3 groups (benign, low-grade malignant, and high-grade malignant) proposed by Ye et al.1 Other investigators have suggested that Ki-67 expression may correlate potential for recurrence and clinical prognosis.12 Expression of CD34 (a marker that supports outer root sheath origin) might favor PTC/MPTT over SCC; however, cases of CD34- negative MPTT have been reported, particularly those with poorly differentiated histopathology.

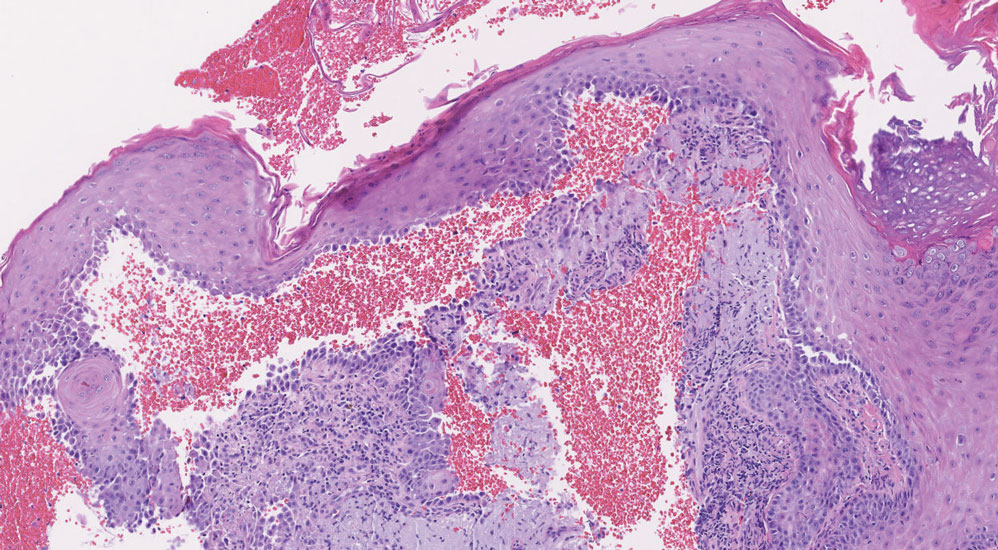

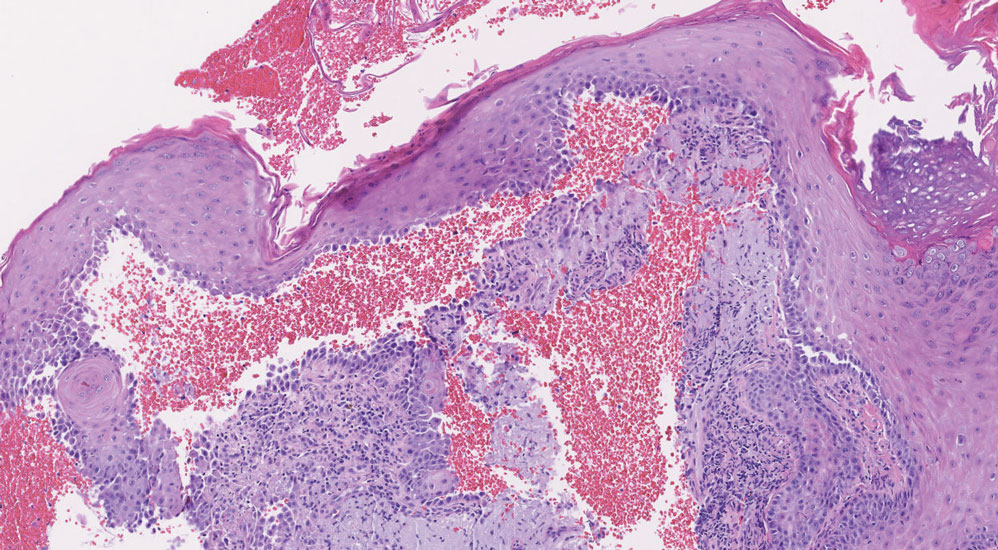

Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by cystlike spaces containing malignant squamous epithelial cells.13 Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features can manifest as a firm nodule with ulceration similar to MPTT or PTC but also can mimic a benign cyst.14 The diagnosis of invasive SCC with cystic features typically is straightforward and characterized by cords and nests of atypical keratinocytes extending into the dermis with areas of cystic architecture (eFigure 2). While both SCC with cystic features and MPTT may show cystic histopathologic architecture, MPTT typically shows areas of PTC, whereas SCC with cystic features lacks such areas.

Verrucous cysts refer to infundibular cysts or less commonly pilar cysts or hybrid pilar-epidermoid cysts that exhibit superimposed human papillomavirus (HPV) cytopathic changes. Clinically, a verrucous cyst manifests as a single, asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm lesion most commonly manifesting on the face and back. Histopathologically, the cyst wall may show acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis with coarse keratohyalin granules, and koilocytic changes (eFigure 3). These histopathologic features are believed to be induced by secondary HPV infection. While HPV-related change, characterized by koilocytic alteration, papillomatosis, and verruciform hyperplasia, more commonly affects epidermal cysts, occasionally trichilemmal (pilar) cysts are involved. In these cases, verrucous cysts should be distinguished from MPTT. Verrucous cysts may contain rare normal mitotic figures, but do not contain atypical mitosis, marked cellular pleomorphism, or an infiltrating pattern similar to MPTT.15

THE DIAGNOSIS: Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

Biopsy revealed a squamous epithelium with cystic changes, trichilemmal differentiation, squamous eddy formation, keratinocyte atypia, focal necrotic changes, and a focus of atypical keratinocytes invading the dermis (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) was made.

Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a rare adnexal tumor that develops from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. It often arises due to malignant transformation of pre-existing trichilemmal cysts, but some cases occur de novo.1 Malignant transformation is thought to start from a trichilemmal cyst in an adenomatous histologic stage, progressing to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (PTC) in an epitheliomatous phase, ultimately becoming carcinomatous with MPTT.2-4 This transformation has been categorized into 3 morphologic groups to predict tumor behavior, including benign PTCs (curable by excision), low-grade malignant PTCs (minor risk for local recurrence), and high-grade malignant PTCs (risk for regional spread and metastasis with cytologic atypical features and potential for aggressive growth).1

More commonly observed in women in the fourth to eighth decades of life, MPTT may manifest as a fast- growing, painless, solitary nodule or as a progressively enlarging nodule at the site of a previously stable, long-standing lesion. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor manifests frequently on the scalp, face, or neck, but there are reports of MPTT manifesting on the trunk and even as multiple concurrent lesions.1-4 The variability in clinical presentation and the potential to be mistaken for benign conditions makes excisional biopsy essential for diagnosis of MPTT. Histopathology classically demonstrates trichilemmal keratinization, a high mitotic index, and cellular atypia with invasion into the dermis.4 Malignant transformation frequently follows a prior history of trauma to the area or local inflammation.

Given the locally aggressive nature of MPTT, our patient was referred to a Mohs micrographic surgeon. While both wide excision with tumor-free margins and Mohs micrographic surgery are accepted surgical procedures for MPTT, there is no consensus in the literature on a standard treatment recommendation. Following surgery, close monitoring is needed for potential recurrence and metastases intracranially to the dura and muscles,5 as well as to the lungs.6 Further imaging using computed tomography or positron emission tomography can be ordered to rule out metastatic disease.4

Pilomatrixomas are benign neoplasms that arise from hair matrix cells and have been associated with catenin beta-1 gene mutations, as well as genetic syndromes and trauma.7 Clinically, pilomatrixomas manifest as solitary, firm, painless, slow-growing nodules that commonly are found in the head and neck region. This tumor has a slight predominance in women and occurs frequently in adolescent years. The overlying skin may appear normal or show grey-bluish discoloration.8 Histopathology shows basaloid cells resembling primitive hair matrix cells with an abrupt transition to shadow cells composed of transformed keratinocytes without nuclei and calcification.7-8 This tumor can be differentiated by the presence of basaloid and shadow cells with calcification on histopathology, while MPTT will show atypical, mitotically active squamous cells with trichilemmal keratinization (Figure 2).

Proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a variant of trichilemmal cyst (TC) arising from the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. While TCs usually are slow growing and benign, the proliferating variant can be more aggressive with malignant potential. Patients often present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, rapidly growing nodule on the scalp. The lesion may be painful, and ulceration can occur, exposing the cystic contents. Histopathologically, PTCs resemble TCs with trichilemmal keratinization but also exhibit notable epithelial proliferation within the cystic space.9 While there can be considerable histopathologic overlap between PTC and MPTT—including extensive trichilemmal keratinization, variable atypia, and mitotic activity—PTC typically should not demonstrate invasion into the surrounding soft tissue or the degree of high-grade atypia, brisk mitoses, or necrosis seen in MPTT (eFigure 1).1 Immunohistochemistry may help distinguish PTC from MPTT and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10-11 The pattern of Ki-67 and p53 expression may be helpful with classification of PTC/MPTT into the 3 groups (benign, low-grade malignant, and high-grade malignant) proposed by Ye et al.1 Other investigators have suggested that Ki-67 expression may correlate potential for recurrence and clinical prognosis.12 Expression of CD34 (a marker that supports outer root sheath origin) might favor PTC/MPTT over SCC; however, cases of CD34- negative MPTT have been reported, particularly those with poorly differentiated histopathology.

Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by cystlike spaces containing malignant squamous epithelial cells.13 Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features can manifest as a firm nodule with ulceration similar to MPTT or PTC but also can mimic a benign cyst.14 The diagnosis of invasive SCC with cystic features typically is straightforward and characterized by cords and nests of atypical keratinocytes extending into the dermis with areas of cystic architecture (eFigure 2). While both SCC with cystic features and MPTT may show cystic histopathologic architecture, MPTT typically shows areas of PTC, whereas SCC with cystic features lacks such areas.

Verrucous cysts refer to infundibular cysts or less commonly pilar cysts or hybrid pilar-epidermoid cysts that exhibit superimposed human papillomavirus (HPV) cytopathic changes. Clinically, a verrucous cyst manifests as a single, asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm lesion most commonly manifesting on the face and back. Histopathologically, the cyst wall may show acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis with coarse keratohyalin granules, and koilocytic changes (eFigure 3). These histopathologic features are believed to be induced by secondary HPV infection. While HPV-related change, characterized by koilocytic alteration, papillomatosis, and verruciform hyperplasia, more commonly affects epidermal cysts, occasionally trichilemmal (pilar) cysts are involved. In these cases, verrucous cysts should be distinguished from MPTT. Verrucous cysts may contain rare normal mitotic figures, but do not contain atypical mitosis, marked cellular pleomorphism, or an infiltrating pattern similar to MPTT.15

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574. doi:10.1309/0XLEGFQ64XYJU4G6

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208. doi:10.1159/000249868

- Rao S, Ramakrishnan R, Kamakshi D, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:51-55. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.79196

- Kearns-Turcotte S, Thériault M, Blouin MM. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors arising in patients with multiple trichilemmal cysts: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:42-46. doi:10.1016

- Karamese M, Akatekin A, Abaci M, et al. Unusual invasion of trichilemmal tumors: two case reports. Modern Plastic Surg. 2012; 2:54-57. doi:10.4236/MPS.2012.23014 /j.jdcr.2022.01.033

- Lobo L, Amonkar AD, Dontamsetty VV. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp with intra-cranial extension and lung metastasis-a case report. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:493-495. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1427-0

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- Sharma D, Agarwal S, Jain LS, et al. Pilomatrixoma masquerading as metastatic adenocarcinoma. A diagnostic pitfall on cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD13-FD14. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9696.5064

- Valerio E, Parro FHS, Macedo MP, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with clinical, radiological, macroscopic, and microscopic orrelation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:452-454. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20198199

- Joshi TP, Marchand S, Tschen J. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor: a subtle presentation in an African American woman and review of immunohistochemical markers for this rare condition. Cureus. 2021;13:E17289. doi:10.7759/cureus.17289

- Gulati HK, Deshmukh SD, Anand M, et al. Low-grade malignant proliferating pilar tumor simulating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an elderly female: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:98-101. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.90818

- Rangel-Gamboa L, Reyes-Castro M, Dominguez-Cherit J, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the value of ki67 immunostaining. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:115-117. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.125599

- Asad U, Alkul S, Shimizu I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with unusual benign-appearing cystic features on histology. Cureus. 2023;15:E33610. doi:10.7759/cureus.33610

- Alkul S, Nguyen CN, Ramani NS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermal inclusion cyst. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2022;35:688-690. doi:10.1080/08998280.2022.207760

- Nanes BA, Laknezhad S, Chamseddin B, et al. Verrucous pilar cysts infected with beta human papillomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:381-386. doi:10.1111/cup.13599

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574. doi:10.1309/0XLEGFQ64XYJU4G6

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208. doi:10.1159/000249868

- Rao S, Ramakrishnan R, Kamakshi D, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:51-55. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.79196

- Kearns-Turcotte S, Thériault M, Blouin MM. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors arising in patients with multiple trichilemmal cysts: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:42-46. doi:10.1016

- Karamese M, Akatekin A, Abaci M, et al. Unusual invasion of trichilemmal tumors: two case reports. Modern Plastic Surg. 2012; 2:54-57. doi:10.4236/MPS.2012.23014 /j.jdcr.2022.01.033

- Lobo L, Amonkar AD, Dontamsetty VV. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp with intra-cranial extension and lung metastasis-a case report. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:493-495. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1427-0

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- Sharma D, Agarwal S, Jain LS, et al. Pilomatrixoma masquerading as metastatic adenocarcinoma. A diagnostic pitfall on cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD13-FD14. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9696.5064

- Valerio E, Parro FHS, Macedo MP, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with clinical, radiological, macroscopic, and microscopic orrelation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:452-454. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20198199

- Joshi TP, Marchand S, Tschen J. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor: a subtle presentation in an African American woman and review of immunohistochemical markers for this rare condition. Cureus. 2021;13:E17289. doi:10.7759/cureus.17289

- Gulati HK, Deshmukh SD, Anand M, et al. Low-grade malignant proliferating pilar tumor simulating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an elderly female: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:98-101. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.90818

- Rangel-Gamboa L, Reyes-Castro M, Dominguez-Cherit J, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the value of ki67 immunostaining. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:115-117. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.125599

- Asad U, Alkul S, Shimizu I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with unusual benign-appearing cystic features on histology. Cureus. 2023;15:E33610. doi:10.7759/cureus.33610

- Alkul S, Nguyen CN, Ramani NS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermal inclusion cyst. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2022;35:688-690. doi:10.1080/08998280.2022.207760

- Nanes BA, Laknezhad S, Chamseddin B, et al. Verrucous pilar cysts infected with beta human papillomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:381-386. doi:10.1111/cup.13599

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

A 38-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology department with a firm enlarging nodule on the scalp of many years’ duration. The patient noted there was no drainage or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a mobile, 2.5-cm, subcutaneous nodule on the right parietal medial scalp. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Recurrent Oral and Gluteal Cleft Erosions

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

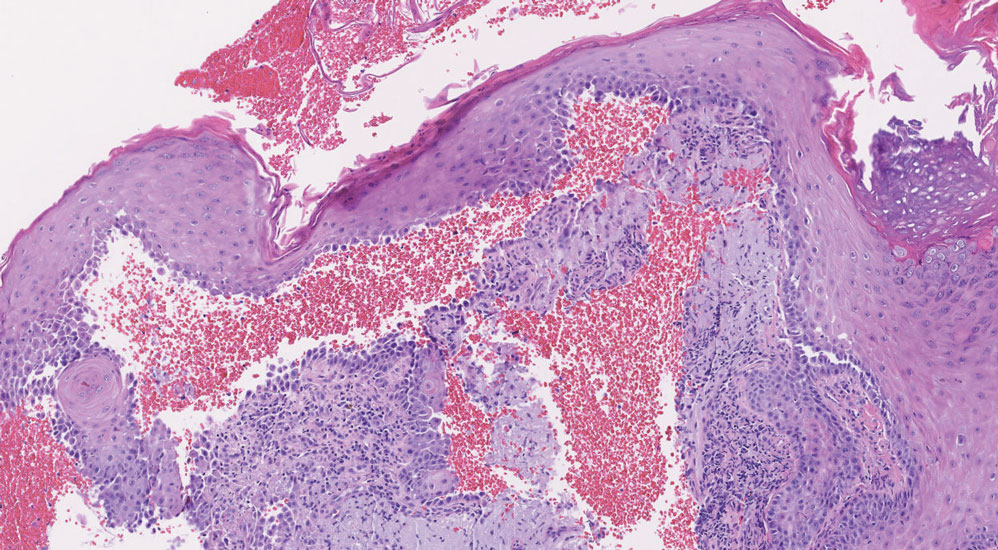

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

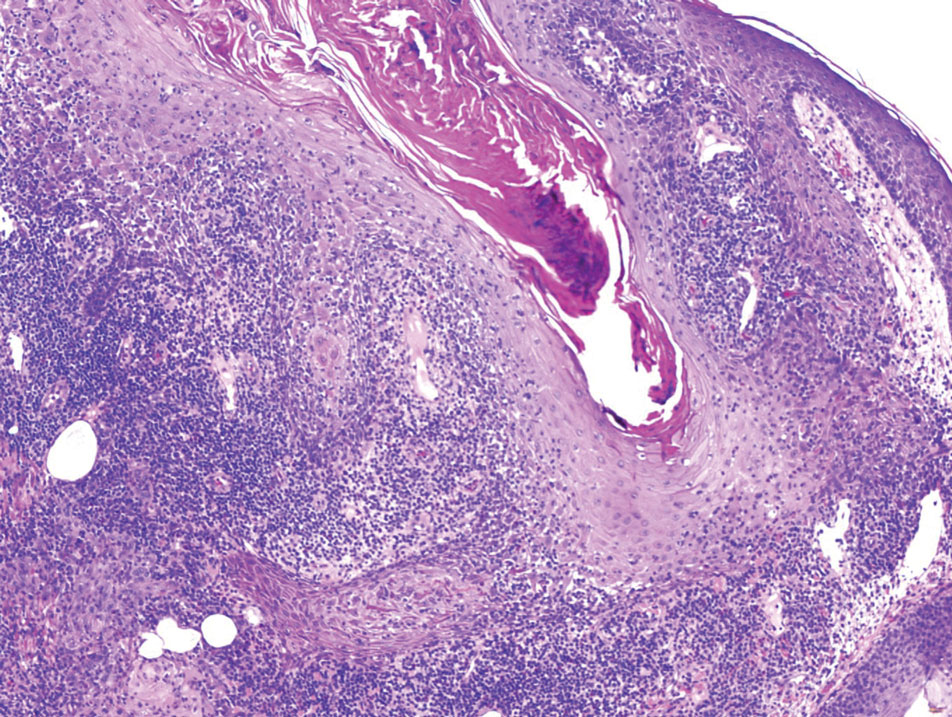

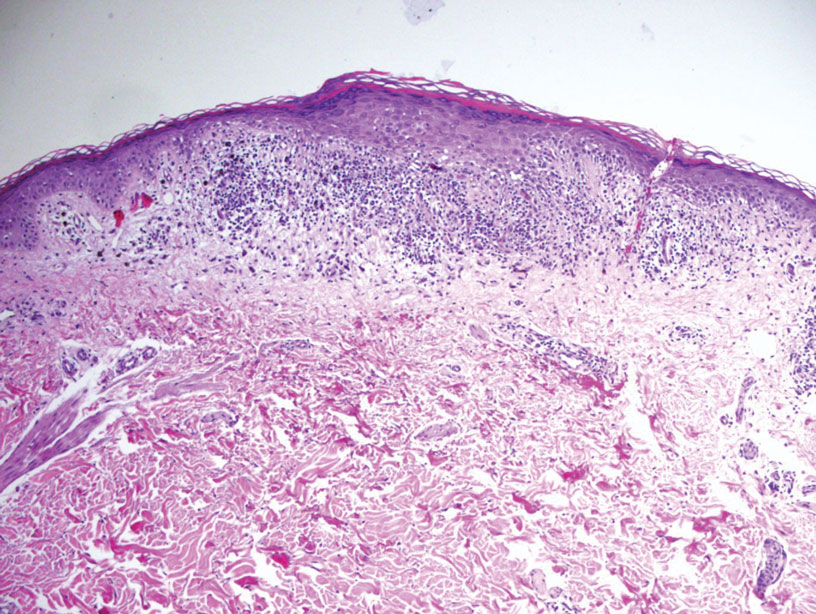

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

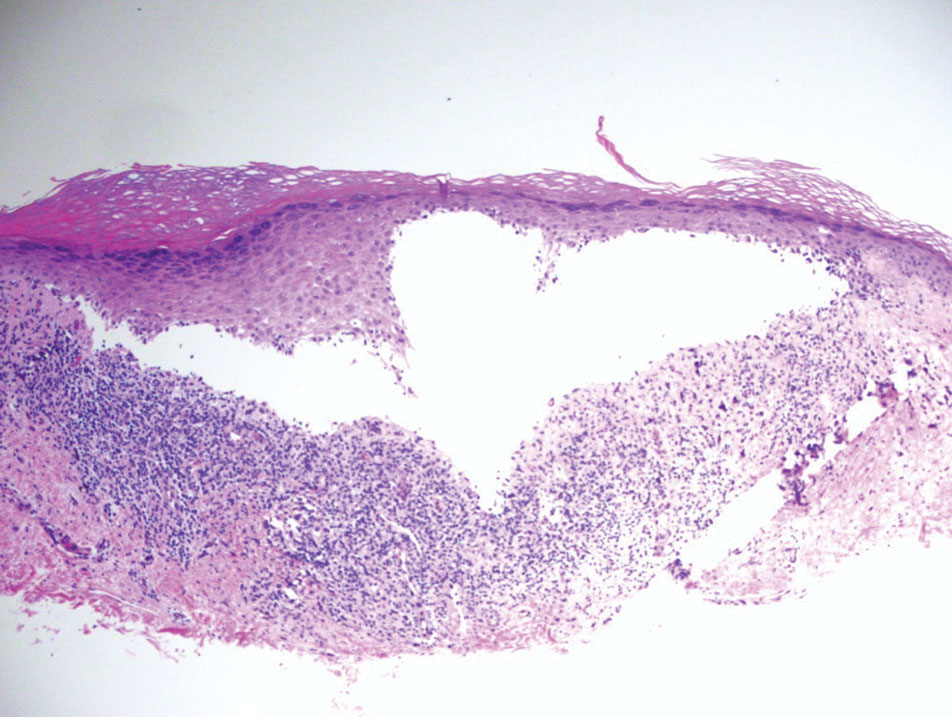

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

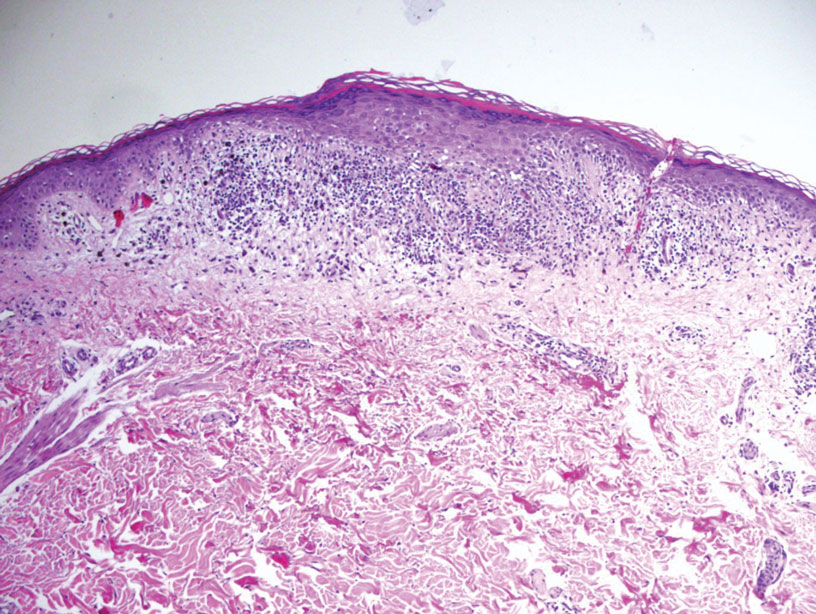

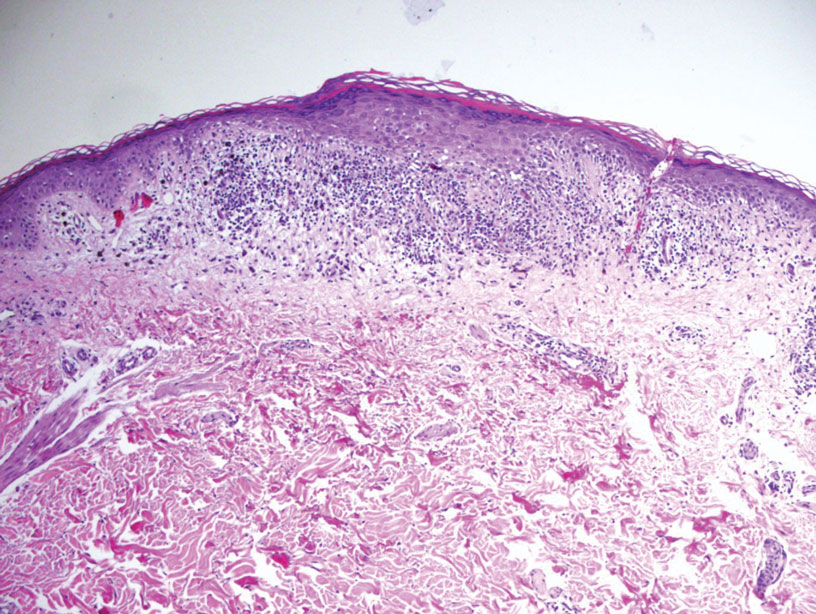

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

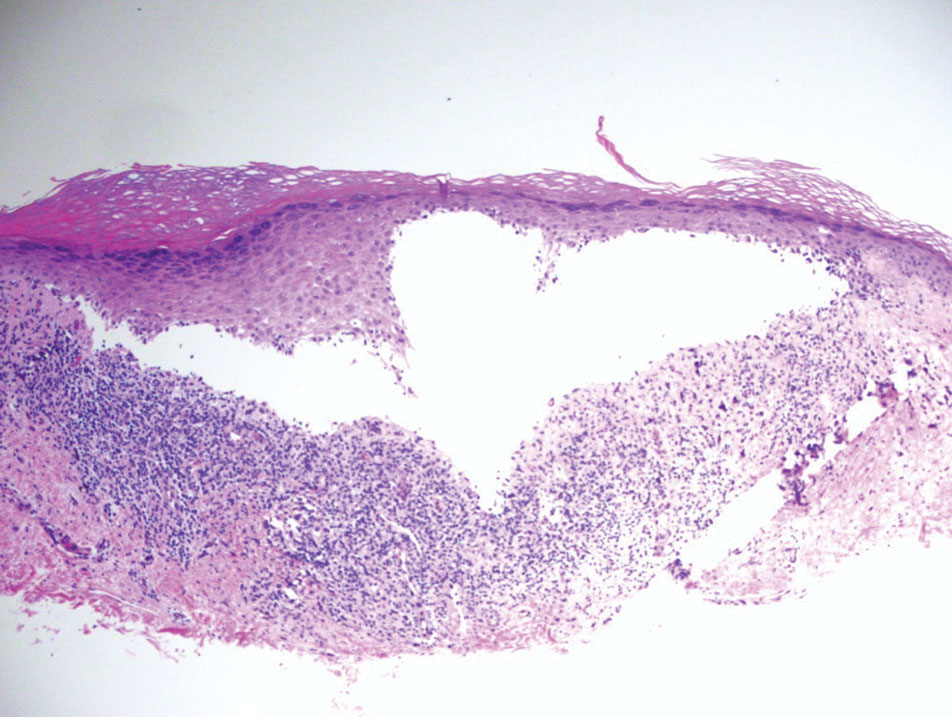

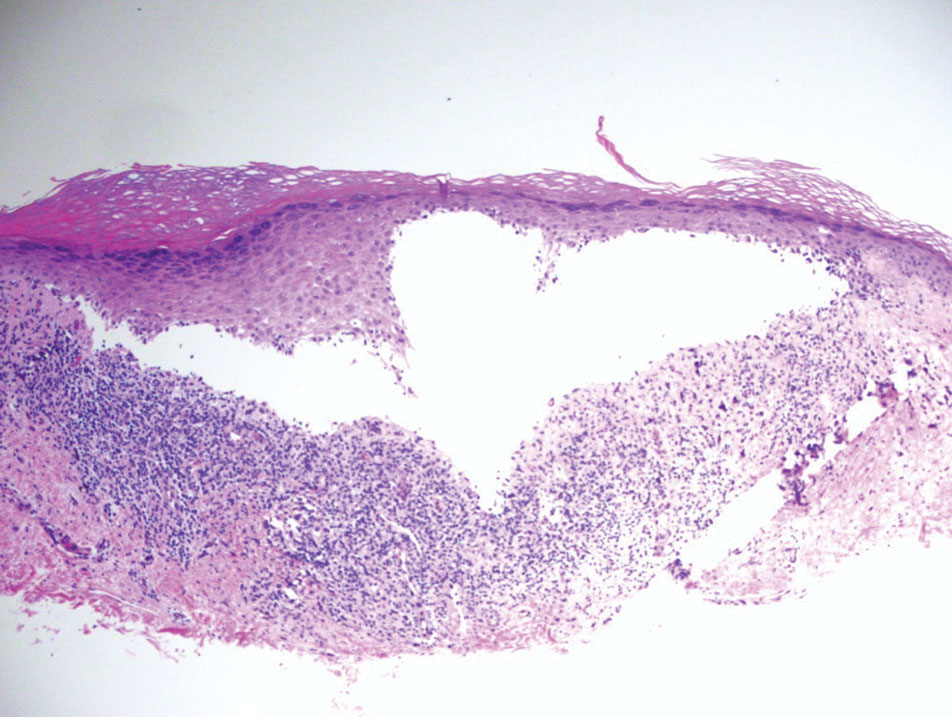

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare acquired autoimmune blistering disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approximately 1 in 1,000,000 individuals.1 It often manifests with overlapping features of both LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP). The condition usually presents in the fifth decade of life and has a slight female predominance.2 Although primarily idiopathic, it has been associated with certain medications and treatments, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 inhibitors, labetalol, narrowband UVB, and psoralen plus UVA.3,4

Patients initially present with lesions of classic lichen planus (LP) with pink-purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques.5 After weeks to months, tense vesicles and bullae usually develop on the sites of LP as well as on uninvolved skin. One study found a mean lag time of about 8.3 months for blistering to present after LP,5 but concurrent presentations of both have been reported.1 In addition, oral mucosal involvement has been seen in 36% of cases. The most commonly affected sites are the extremities; however, involvement can be widespread.2

The pathogenesis of LPP currently is unknown. It has been proposed that in LP, injury of basal keratinocytes exposes hidden basement membrane and hemidesmosome antigens including BP180, a 180 kDa transmembrane protein of the basement membrane zone (BMZ),6 which triggers an immune response where T cells recognize the extracellular portion of BP180 and antibodies are formed against the likely autoantigen.1 One study has suggested that the autoantigen in LPP is the MCW-4 epitope within the C-terminal end of the NC16A domain of BP180.7

Histopathology of LPP reveals characteristics of both LP as well as BP. Typical features of LP on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining include lichenoid lymphocytic interface dermatitis, sawtooth rete ridges, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, and colloid bodies, as demonstrated from the biopsy of our patient’s gluteal cleft lesion (quiz image 1), while the predominant feature of BP on H&E staining includes a subepidermal bulla with eosinophils.2 Typically, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear deposits of IgG and/or C3 along the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) often reveals IgG against the roof of the BMZ in a human split-skin substrate.1 Antibodies against BP180 or uncommonly BP230 often are detected on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). For our patient, IIF and ELISA tests were positive. Given the clinical presentation with recurrent oral and gluteal cleft erosions, histologic findings, and the results of our patient’s immunological testing, the diagnosis of LPP was made.

Topical steroids often are used to treat localized disease of LPP.8 Oral prednisone also may be given for widespread or unresponsive disease.9 Other treatments include azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, hydroxychloroquine, dapsone, tetracycline in combination with nicotinamide, acitretin, ustekinumab, baricitinib, and rituximab with intravenous immunoglobulin.3,8,10-12 Any potential medication culprits should be discontinued.9 Patients with oral involvement may require a soft diet to avoid further mucosal insult.10 Additionally, providers should consider dentistry, ophthalmology, and/or otolaryngology referrals depending on disease severity.

Bullous pemphigoid, the most common autoimmune blistering disease, has an estimated incidence of 10 to 43 per million individuals per year.2 Classically, it presents with tense bullae on the skin of the lower abdomen, thighs, groin, forearms, and axillae. Circulating antibodies against 2 BMZ proteins—BP180 and BP230—are important factors in BP pathogenesis.2 Diagnosis of BP is based on clinical features, histologic findings, and immunological studies including DIF, IIF, and ELISA. An eosinophil-rich subepidermal split typically is seen on H&E staining (Figure 1).

Direct immunofluorescence displays linear IgG and/ or C3 staining at the BMZ. Indirect immunofluorescence on a human salt-split skin substrate commonly shows linear BMZ deposition on the roof of the blister.2 Indirect immunofluorescence for IgG deposition on monkey esophagus substrate shows linear BMZ deposition. Antibodies against the NC16A domain of BP180 (NC16A-BP180) are dominant, but BP230 antibodies against BP230 also are detected with ELISA.2 Further studies have indicated that the NC16A epitopes of BP180 that are targeted in BP are MCW-0-3,2 different from the autoantigen MCW-4 that is targeted in LPP.7

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP) is another diagnosis to consider. Patients with PNP initially present with oral findings—most commonly chronic, erosive, and painful mucositis—followed by cutaneous involvement, which varies from the development of bullae to the formation of plaques similar to those of LP.13 The latter, in combination with oral erosions, may appear clinically similar to LPP. The results of DIF in conjugation with IIF and ELISA may help to further differentiate these disorders. Direct immunofluorescence in PNP typically reveals positive intercellular and/or BMZ IgG and C3, while DIF in LPP reveals depositions along the BMZ alone. Indirect immunofluorescence performed on rat bladder epithelium is particularly useful, as binding of IgG to rat bladder epithelium is characteristic of PNP and not seen in other disorders.14 Lastly, patients with PNP may develop IgG antibodies to various antigens such as desmoplakin I, desmoplakin II, envoplakin, periplakin, BP230, desmoglein 1, and desmoglein 3, which would not be expected in LPP patients.15 Hematoxylin and eosin staining differs from LPP, primarily with the location of the blister being intraepidermal. Acantholysis with hemorrhagic bullae can be seen (Figure 2).

Classic LP is an inflammatory disorder that mainly affects adults, with an estimated incidence of less than 1%.16 The classic form presents with purple, flat-topped, pruritic, polygonal papules and plaques of varying size that often are characterized by Wickham striae. Lichen planus possesses a broad spectrum of subtypes involving different locations, though skin lesions usually are localized to the extremities. Despite an unknown etiology, activated T cells and T helper type 1 cytokines are considered key in keratinocyte injury. Compact orthokeratosis, wedge-shaped hypergranulosis, focal dyskeratosis, and colloid bodies typically are found on H&E staining, along with a dense bandlike lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ)(Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence typically shows a shaggy band of fibrinogen along the DEJ in addition to colloid bodies that stain with various autoantibodies including IgM, IgG, IgA, and C3.16

Bullous LP is a rare variant of LP that commonly develops on the oral mucosa and the legs, with blisters confined on pre-existing LP lesions.9 The pathogenesis is related to an epidermal inflammatory infiltrate that leads to basal layer destruction followed by dermal-epidermal separations that cause blistering.17 Bullous LP does not have positive DIF, IIF, or ELISA because the pathophysiology does not involve autoantibody production. Histopathology typically displays an extensive inflammatory infiltrate and degeneration of the basal keratinocytes, resulting in large dermal-epidermal separations called Max-Joseph spaces (Figure 4).17 Colloid bodies are prominent in bullous LP but rarely are seen in LPP; eosinophils also are much more prominent in LPP compared to bullous LP.18 Unlike in LPP, DIF usually is negative in bullous LP, though lichenoid lesions may exhibit globular deposition of IgM, IgG, and IgA in the colloid bodies of the lower epidermis and/or papillary dermis. Similar to LP, DIF of the biopsy specimen shows linear or shaggy deposits of fibrinogen at the DEJ.17

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

- Hübner F, Langan EA, Recke A. Lichen planus pemphigoides: from lichenoid inflammation to autoantibody-mediated blistering. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1389.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Hackländer K, Lehmann P, Hofmann SC. Successful treatment of lichen planus pemphigoides using acitretin as monotherapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:818-819.

- Boyle M, Ashi S, Puiu T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides associated with PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44:360-367.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaru JM Jr, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Liakopoulou A, Rallis E. Bullous lichen planus—a review. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2017;11:1-4.

- Weston G, Payette M. Update on lichen planus and its clinical variants. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1:140-149.

- Moussa A, Colla TG, Asfour L, et al. Effective treatment of refractory lichen planus pemphigoides with a Janus kinase-1/2 inhibitor. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:2040-2041.

- Brennan M, Baldissano M, King L, et al. Successful use of rituximab and intravenous gamma globulin to treat checkpoint inhibitor-induced severe lichen planus pemphigoides. Skinmed. 2020;18:246-249.

- Kim JH, Kim SC. Paraneoplastic pemphigus: paraneoplastic autoimmune disease of the skin and mucosa. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1259.

- Stevens SR, Griffiths CE, Anhalt GJ, et al. Paraneoplastic pemphigus presenting as a lichen planus pemphigoides-like eruption. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:866-869.

- Ohzono A, Sogame R, Li X, et al. Clinical and immunological findings in 104 cases of paraneoplastic pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1447-1452.

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Papara C, Danescu S, Sitaru C, et al. Challenges and pitfalls between lichen planus pemphigoides and bullous lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2022;63:165-171.

- Tripathy DM, Vashisht D, Rathore G, et al. Bullous lichen planus vs lichen planus pemphigoides: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:282-284.

A 71-year-old woman with no relevant medical history presented with recurrent painful erosions on the gingivae and gluteal cleft of 1 year’s duration. She previously was diagnosed by her periodontist with erosive lichen planus and was prescribed topical and oral steroids with minimal improvement. She denied fever, chills, weakness, fatigue, vision changes, eye pain, and sore throat. Dermatologic examination revealed edematous and erythematous upper and lower gingivae with mild erosions, as well as thin, eroded, erythematous plaques within the gluteal cleft. Indirect immunofluorescence revealed IgG with epidermal localization in a human split-skin substrate, and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed positive IgG to bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 and negative IgG to BP230. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the gluteal cleft was performed.