User login

SCHOLAR Project

The structure and function of academic hospital medicine programs (AHPs) has evolved significantly with the growth of hospital medicine.[1, 2, 3, 4] Many AHPs formed in response to regulatory and financial changes, which drove demand for increased trainee oversight, improved clinical efficiency, and growth in nonteaching services staffed by hospitalists. Differences in local organizational contexts and needs have contributed to great variability in AHP program design and operations. As AHPs have become more established, the need to engage academic hospitalists in scholarship and activities that support professional development and promotion has been recognized. Defining sustainable and successful positions for academic hospitalists is a priority called for by leaders in the field.[5, 6]

In this rapidly evolving context, AHPs have employed a variety of approaches to organizing clinical and academic faculty roles, without guiding evidence or consensus‐based performance benchmarks. A number of AHPs have achieved success along traditional academic metrics of research, scholarship, and education. Currently, it is not known whether specific approaches to AHP organization, structure, or definition of faculty roles are associated with achievement of more traditional markers of academic success.

The Academic Committee of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), and the Academic Hospitalist Task Force of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) had separately initiated projects to explore characteristics associated with success in AHPs. In 2012, these organizations combined efforts to jointly develop and implement the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in Academics and Research) project. The goals were to identify successful AHPs using objective criteria, and to then study those groups in greater detail to generate insights that would be broadly relevant to the field. Efforts to clarify the factors within AHPs linked to success by traditional academic metrics will benefit hospitalists, their leaders, and key stakeholders striving to achieve optimal balance between clinical and academic roles. We describe the initial work of the SCHOLAR project, our definitions of academic success in AHPs, and the characteristics of a cohort of exemplary AHPs who achieved the highest levels on these metrics.

METHODS

Defining Success

The 11 members of the SCHOLAR project held a variety of clinical and academic roles within a geographically diverse group of AHPs. We sought to create a functional definition of success applicable to AHPs. As no gold standard currently exists, we used a consensus process among task force members to arrive at a definition that was quantifiable, feasible, and meaningful. The first step was brainstorming on conference calls held 1 to 2 times monthly over 4 months. Potential defining characteristics that emerged from these discussions related to research, teaching, and administrative activities. When potential characteristics were proposed, we considered how to operationalize each one. Each characteristic was discussed until there was consensus from the entire group. Those around education and administration were the most complex, as many roles are locally driven and defined, and challenging to quantify. For this reason, we focused on promotion as a more global approach to assessing academic hospitalist success in these areas. Although criteria for academic advancement also vary across institutions, we felt that promotion generally reflected having met some threshold of academic success. We also wanted to recognize that scholarship occurs outside the context of funded research. Ultimately, 3 key domains emerged: research grant funding, faculty promotion, and scholarship.

After these 3 domains were identified, the group sought to define quantitative metrics to assess performance. These discussions occurred on subsequent calls over a 4‐month period. Between calls, group members gathered additional information to facilitate assessment of the feasibility of proposed metrics, reporting on progress via email. Again, group consensus was sought for each metric considered. Data on grant funding and successful promotions were available from a previous survey conducted through the SHM in 2011. Leaders from 170 AHPs were contacted, with 50 providing complete responses to the 21‐item questionnaire (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). Results of the survey, heretofore referred to as the Leaders of Academic Hospitalist Programs survey (LAHP‐50), have been described elsewhere.[7] For the purposes of this study, we used the self‐reported data about grant funding and promotions contained in the survey to reflect the current state of the field. Although the survey response rate was approximately 30%, the survey was not anonymous, and many reputationally prominent academic hospitalist programs were represented. For these reasons, the group members felt that the survey results were relevant for the purposes of assessing academic success.

In the LAHP‐50, funding was defined as principal investigator or coinvestigator roles on federally and nonfederally funded research, clinical trials, internal grants, and any other extramurally funded projects. Mean and median funding for the overall sample was calculated. Through a separate question, each program's total faculty full‐time equivalent (FTE) count was reported, allowing us to adjust for group size by assessing both total funding per group and funding/FTE for each responding AHP.

Promotions were defined by the self‐reported number of faculty at each of the following ranks: instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, full professor, and professor above scale/emeritus. In addition, a category of nonacademic track (eg, adjunct faculty, clinical associate) was included to capture hospitalists that did not fit into the traditional promotions categories. We did not distinguish between tenure‐track and nontenure‐track academic ranks. LAHP‐50 survey respondents reported the number of faculty in their group at each academic rank. Given that the majority of academic hospitalists hold a rank of assistant professor or lower,[6, 8, 9] and that the number of full professors was only 3% in the LAHP‐50 cohort, we combined the faculty at the associate and full professor ranks, defining successfully promoted faculty as the percent of hospitalists above the rank of assistant professor.

We created a new metric to assess scholarly output. We had considerable discussion of ways to assess the numbers of peer‐reviewed manuscripts generated by AHPs. However, the group had concerns about the feasibility of identification and attribution of authors to specific AHPs through literature searches. We considered examining only publications in the Journal of Hospital Medicine and the Journal of General Internal Medicine, but felt that this would exclude significant work published by hospitalists in fields of medical education or health services research that would more likely appear in alternate journals. Instead, we quantified scholarship based on the number of abstracts presented at national meetings. We focused on meetings of the SHM and SGIM as the primary professional societies representing hospital medicine. The group felt that even work published outside of the journals of our professional societies would likely be presented at those meetings. We used the following strategy: We reviewed research abstracts accepted for presentation as posters or oral abstracts at the 2010 and 2011 SHM national meetings, and research abstracts with a primary or secondary category of hospital medicine at the 2010 and 2011 SGIM national meetings. By including submissions at both SGIM and SHM meetings, we accounted for the fact that some programs may gravitate more to one society meeting or another. We did not include abstracts in the clinical vignettes or innovations categories. We tallied the number of abstracts by group affiliation of the authors for each of the 4 meetings above and created a cumulative total per group for the 2‐year period. Abstracts with authors from different AHPs were counted once for each individual group. Members of the study group reviewed abstracts from each of the meetings in pairs. Reviewers worked separately and compared tallies of results to ensure consistent tabulations. Internet searches were conducted to identify or confirm author affiliations if it was not apparent in the abstract author list. Abstract tallies were compiled without regard to whether programs had completed the LAHP‐50 survey; thus, we collected data on programs that did not respond to the LAHP‐50 survey.

Identification of the SCHOLAR Cohort

To identify our cohort of top‐performing AHPs, we combined the funding and promotions data from the LAHP‐50 sample with the abstract data. We limited our sample to adult hospital medicine groups to reduce heterogeneity. We created rank lists of programs in each category (grant funding, successful promotions, and scholarship), using data from the LAHP‐50 survey to rank programs on funding and promotions, and data from our abstract counts to rank on scholarship. We limited the top‐performing list in each category to 10 institutions as a cutoff. Because we set a threshold of at least $1 million in total funding, we identified only 9 top performing AHPs with regard to grant funding. We also calculated mean funding/FTE. We chose to rank programs only by funding/FTE rather than total funding per program to better account for group size. For successful promotions, we ranked programs by the percentage of senior faculty. For abstract counts, we included programs whose faculty presented abstracts at a minimum of 2 separate meetings, and ranked programs based on the total number of abstracts per group.

This process resulted in separate lists of top performing programs in each of the 3 domains we associated with academic success, arranged in descending order by grant dollars/FTE, percent of senior faculty, and abstract counts (Table 1). Seventeen different programs were represented across these 3 top 10 lists. One program appeared on all 3 lists, 8 programs appeared on 2 lists, and the remainder appeared on a single list (Table 2). Seven of these programs were identified solely based on abstract presentations, diversifying our top groups beyond only those who completed the LAHP‐50 survey. We considered all of these programs to represent high performance in academic hospital medicine. The group selected this inclusive approach because we recognized that any 1 metric was potentially limited, and we sought to identify diverse pathways to success.

| Funding | Promotions | Scholarship | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grant $/FTE | Total Grant $ | Senior Faculty, No. (%) | Total Abstract Count |

| |||

| $1,409,090 | $15,500,000 | 3 (60%) | 23 |

| $1,000,000 | $9,000,000 | 3 (60%) | 21 |

| $750,000 | $8,000,000 | 4 (57%) | 20 |

| $478,609 | $6,700,535 | 9 (53%) | 15 |

| $347,826 | $3,000,000 | 8 (44%) | 11 |

| $86,956 | $3,000,000 | 14 (41%) | 11 |

| $66,666 | $2,000,000 | 17 (36%) | 10 |

| $46,153 | $1,500,000 | 9 (33%) | 10 |

| $38,461 | $1,000,000 | 2 (33%) | 9 |

| 4 (31%) | 9 | ||

| Selection Criteria for SCHOLAR Cohort | No. of Programs |

|---|---|

| |

| Abstracts, funding, and promotions | 1 |

| Abstracts plus promotions | 4 |

| Abstracts plus funding | 3 |

| Funding plus promotion | 1 |

| Funding only | 1 |

| Abstract only | 7 |

| Total | 17 |

| Top 10 abstract count | |

| 4 meetings | 2 |

| 3 meetings | 2 |

| 2 meetings | 6 |

The 17 unique adult AHPs appearing on at least 1 of the top 10 lists comprised the SCHOLAR cohort of programs that we studied in greater detail. Data reflecting program demographics were solicited directly from leaders of the AHPs identified in the SCHOLAR cohort, including size and age of program, reporting structure, number of faculty at various academic ranks (for programs that did not complete the LAHP‐50 survey), and number of faculty with fellowship training (defined as any postresidency fellowship program).

Subsequently, we performed comparative analyses between the programs in the SCHOLAR cohort to the general population of AHPs reflected by the LAHP‐50 sample. Because abstract presentations were not recorded in the original LAHP‐50 survey instrument, it was not possible to perform a benchmarking comparison for the scholarship domain.

Data Analysis

To measure the success of the SCHOLAR cohort we compared the grant funding and proportion of successfully promoted faculty at the SCHOLAR programs to those in the overall LAHP‐50 sample. Differences in mean and median grant funding were compared using t tests and Mann‐Whitney rank sum tests. Proportion of promoted faculty were compared using 2 tests. A 2‐tailed of 0.05 was used to test significance of differences.

RESULTS

Demographics

Among the AHPs in the SCHOLAR cohort, the mean program age was 13.2 years (range, 618 years), and the mean program size was 36 faculty (range, 1895; median, 28). On average, 15% of faculty members at SCHOLAR programs were fellowship trained (range, 0%37%). Reporting structure among the SCHOLAR programs was as follows: 53% were an independent division or section of the department of medicine; 29% were a section within general internal medicine, and 18% were an independent clinical group.

Grant Funding

Table 3 compares grant funding in the SCHOLAR programs to programs in the overall LAHP‐50 sample. Mean funding per group and mean funding per FTE were significantly higher in the SCHOLAR group than in the overall sample.

| Funding (Millions) | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAHP‐50 Overall Sample | SCHOLAR | |

| ||

| Median grant funding/AHP | 0.060 | 1.500* |

| Mean grant funding/AHP | 1.147 (015) | 3.984* (015) |

| Median grant funding/FTE | 0.004 | 0.038* |

| Mean grant funding/FTE | 0.095 (01.4) | 0.364* (01.4) |

Thirteen of the SCHOLAR programs were represented in the initial LAHP‐50, but 2 did not report a dollar amount for grants and contracts. Therefore, data for total grant funding were available for only 65% (11 of 17) of the programs in the SCHOLAR cohort. Of note, 28% of AHPs in the overall LAHP‐50 sample reported no external funding sources.

Faculty Promotion

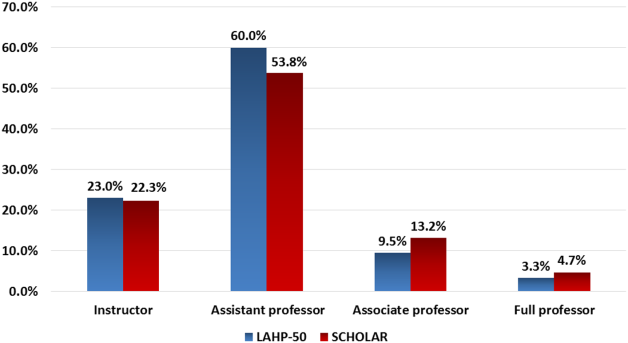

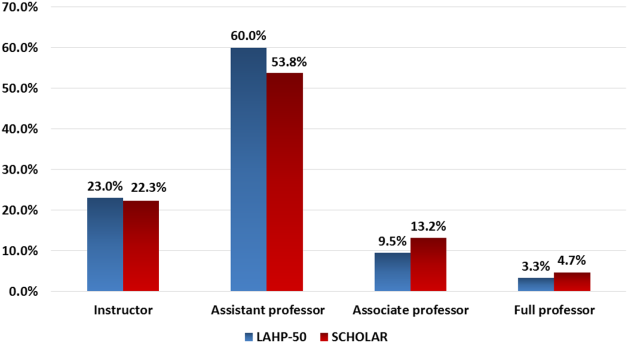

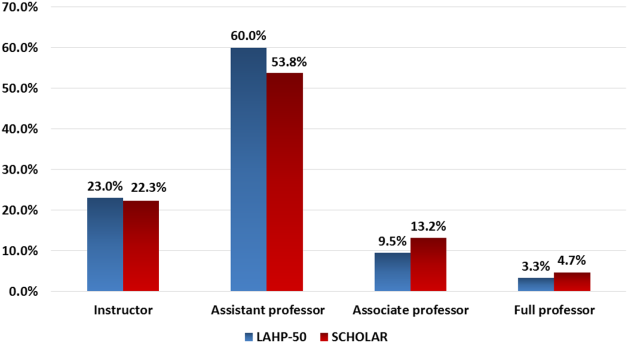

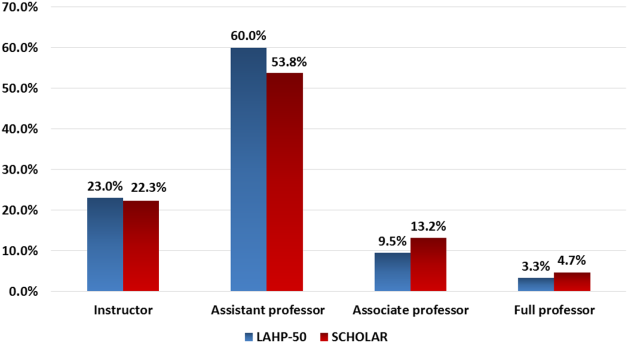

Figure 1 demonstrates the proportion of faculty at various academic ranks. The percent of faculty above the rank of assistant professor in the SCHOLAR programs exceeded those in the overall LAHP‐50 by 5% (17.9% vs 12.8%, P = 0.01). Of note, 6% of the hospitalists at AHPs in the SCHOLAR programs were on nonfaculty tracks.

Scholarship

Mean abstract output over the 2‐year period measured was 10.8 (range, 323) in the SCHOLAR cohort. Because we did not collect these data for the LAHP‐50 group, comparative analyses were not possible.

DISCUSSION

Using a definition of academic success that incorporated metrics of grant funding, faculty promotion, and scholarly output, we identified a unique subset of successful AHPsthe SCHOLAR cohort. The programs represented in the SCHOLAR cohort were generally large and relatively mature. Despite this, the cohort consisted of mostly junior faculty, had a paucity of fellowship‐trained hospitalists, and not all reported grant funding.

Prior published work reported complementary findings.[6, 8, 9] A survey of 20 large, well‐established academic hospitalist programs in 2008 found that the majority of hospitalists were junior faculty with a limited publication portfolio. Of the 266 respondents in that study, 86% reported an academic rank at or below assistant professor; funding was not explored.[9] Our similar findings 4 years later add to this work by demonstrating trends over time, and suggest that progress toward creating successful pathways for academic advancement has been slow. In a 2012 survey of the SHM membership, 28% of hospitalists with academic appointments reported no current or future plans to engage in research.[8] These findings suggest that faculty in AHPs may define scholarship through nontraditional pathways, or in some cases choose not to pursue or prioritize scholarship altogether.

Our findings also add to the literature with regard to our assessment of funding, which was variable across the SCHOLAR group. The broad range of funding in the SCHOLAR programs for which we have data (grant dollars $0$15 million per program) suggests that opportunities to improve supported scholarship remain, even among a selected cohort of successful AHPs. The predominance of junior faculty in the SCHOLAR programs may be a reason for this variation. Junior faculty may be engaged in research with funding directed to senior mentors outside their AHP. Alternatively, they may pursue meaningful local hospital quality improvement or educational innovations not supported by external grants, or hold leadership roles in education, quality, or information technology that allow for advancement and promotion without external grant funding. As the scope and impact of these roles increases, senior leaders with alternate sources of support may rely less on research funds; this too may explain some of the differences. Our findings are congruent with results of a study that reviewed original research published by hospitalists, and concluded that the majority of hospitalist research was not externally funded.[8] Our approach for assessing grant funding by adjusting for FTE had the potential to inadvertently favor smaller well‐funded groups over larger ones; however, programs in our sample were similarly represented when ranked by funding/FTE or total grant dollars. As many successful AHPs do concentrate their research funding among a core of focused hospitalist researchers, our definition may not be the ideal metric for some programs.

We chose to define scholarship based on abstract output, rather than peer‐reviewed publications. Although this choice was necessary from a feasibility perspective, it may have excluded programs that prioritize peer‐reviewed publications over abstracts. Although we were unable to incorporate a search strategy to accurately and comprehensively track the publication output attributed specifically to hospitalist researchers and quantify it by program, others have since defined such an approach.[8] However, tracking abstracts theoretically allowed insights into a larger volume of innovative and creative work generated by top AHPs by potentially including work in the earlier stages of development.

We used a consensus‐based definition of success to define our SCHOLAR cohort. There are other ways to measure academic success, which if applied, may have yielded a different sample of programs. For example, over half of the original research articles published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine over a 7‐year span were generated from 5 academic centers.[8] This definition of success may be equally credible, though we note that 4 of these 5 programs were also included in the SCHOLAR cohort. We feel our broader approach was more reflective of the variety of pathways to success available to academic hospitalists. Before our metrics are applied as a benchmarking tool, however, they should ideally be combined with factors not measured in our study to ensure a more comprehensive or balanced reflection of academic success. Factors such as mentorship, level of hospitalist engagement,[10] prevalence of leadership opportunities, operational and fiscal infrastructure, and the impact of local quality, safety, and value efforts should be considered.

Comparison of successfully promoted faculty at AHPs across the country is inherently limited by the wide variation in promotion standards across different institutions; controlling for such differences was not possible with our methodology. For example, it appears that several programs with relatively few senior faculty may have met metrics leading to their inclusion in the SCHOLAR group because of their small program size. Future benchmarking efforts for promotion at AHPs should take scaling into account and consider both total number as well as percentage of senior faculty when evaluating success.

Our methodology has several limitations. Survey data were self‐reported and not independently validated, and as such are subject to recall and reporting biases. Response bias inherently excluded some AHPs that may have met our grant funding or promotions criteria had they participated in the initial LAHP‐50 survey, though we identified and included additional programs through our scholarship metric, increasing the representativeness of the SCHOLAR cohort. Given the dynamic nature of the field, the age of the data we relied upon for analysis limits the generalizability of our specific benchmarks to current practice. However, the development of academic success occurs over the long‐term, and published data on academic hospitalist productivity are consistent with this slower time course.[8] Despite these limitations, our data inform the general topic of gauging performance of AHPs, underscoring the challenges of developing and applying metrics of success, and highlight the variability of performance on selected metrics even among a relatively small group of 17 programs.

In conclusion, we have created a method to quantify academic success that may be useful to academic hospitalists and their group leaders as they set targets for improvement in the field. Even among our SCHOLAR cohort, room for ongoing improvement in development of funded scholarship and a core of senior faculty exists. Further investigation into the unique features of successful groups will offer insight to leaders in academic hospital medicine regarding infrastructure and processes that should be embraced to raise the bar for all AHPs. In addition, efforts to further define and validate nontraditional approaches to scholarship that allow for successful promotion at AHPs would be informative. We view our work less as a singular approach to benchmarking standards for AHPs, and more a call to action to continue efforts to balance scholarly activity and broad professional development of academic hospitalists with increasing clinical demands.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the AHP leaders who participated in the SCHOLAR project. They also thank the Society of Hospital Medicine and Society of General Internal Medicine and the SHM Academic Committee and SGIM Academic Hospitalist Task Force for their support of this work.

Disclosures

The work reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, South Texas Veterans Health Care System. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , . Characteristics of primary care providers who adopted the hospitalist model from 2001 to 2009. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):75–82.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , , , , . Updating threshold‐based identification of hospitalists in 2012 Medicare pay data. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):45–47.

- , , , . Use of hospitalists by Medicare beneficiaries: a national picture. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(2).

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in Academic Hospital Medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):240–246.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5–9.

- , , , , , . The structure of hospital medicine programs at academic medical centers [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(suppl 2):s92.

- , , , , . Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148–154.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , , , et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123–128.

The structure and function of academic hospital medicine programs (AHPs) has evolved significantly with the growth of hospital medicine.[1, 2, 3, 4] Many AHPs formed in response to regulatory and financial changes, which drove demand for increased trainee oversight, improved clinical efficiency, and growth in nonteaching services staffed by hospitalists. Differences in local organizational contexts and needs have contributed to great variability in AHP program design and operations. As AHPs have become more established, the need to engage academic hospitalists in scholarship and activities that support professional development and promotion has been recognized. Defining sustainable and successful positions for academic hospitalists is a priority called for by leaders in the field.[5, 6]

In this rapidly evolving context, AHPs have employed a variety of approaches to organizing clinical and academic faculty roles, without guiding evidence or consensus‐based performance benchmarks. A number of AHPs have achieved success along traditional academic metrics of research, scholarship, and education. Currently, it is not known whether specific approaches to AHP organization, structure, or definition of faculty roles are associated with achievement of more traditional markers of academic success.

The Academic Committee of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), and the Academic Hospitalist Task Force of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) had separately initiated projects to explore characteristics associated with success in AHPs. In 2012, these organizations combined efforts to jointly develop and implement the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in Academics and Research) project. The goals were to identify successful AHPs using objective criteria, and to then study those groups in greater detail to generate insights that would be broadly relevant to the field. Efforts to clarify the factors within AHPs linked to success by traditional academic metrics will benefit hospitalists, their leaders, and key stakeholders striving to achieve optimal balance between clinical and academic roles. We describe the initial work of the SCHOLAR project, our definitions of academic success in AHPs, and the characteristics of a cohort of exemplary AHPs who achieved the highest levels on these metrics.

METHODS

Defining Success

The 11 members of the SCHOLAR project held a variety of clinical and academic roles within a geographically diverse group of AHPs. We sought to create a functional definition of success applicable to AHPs. As no gold standard currently exists, we used a consensus process among task force members to arrive at a definition that was quantifiable, feasible, and meaningful. The first step was brainstorming on conference calls held 1 to 2 times monthly over 4 months. Potential defining characteristics that emerged from these discussions related to research, teaching, and administrative activities. When potential characteristics were proposed, we considered how to operationalize each one. Each characteristic was discussed until there was consensus from the entire group. Those around education and administration were the most complex, as many roles are locally driven and defined, and challenging to quantify. For this reason, we focused on promotion as a more global approach to assessing academic hospitalist success in these areas. Although criteria for academic advancement also vary across institutions, we felt that promotion generally reflected having met some threshold of academic success. We also wanted to recognize that scholarship occurs outside the context of funded research. Ultimately, 3 key domains emerged: research grant funding, faculty promotion, and scholarship.

After these 3 domains were identified, the group sought to define quantitative metrics to assess performance. These discussions occurred on subsequent calls over a 4‐month period. Between calls, group members gathered additional information to facilitate assessment of the feasibility of proposed metrics, reporting on progress via email. Again, group consensus was sought for each metric considered. Data on grant funding and successful promotions were available from a previous survey conducted through the SHM in 2011. Leaders from 170 AHPs were contacted, with 50 providing complete responses to the 21‐item questionnaire (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). Results of the survey, heretofore referred to as the Leaders of Academic Hospitalist Programs survey (LAHP‐50), have been described elsewhere.[7] For the purposes of this study, we used the self‐reported data about grant funding and promotions contained in the survey to reflect the current state of the field. Although the survey response rate was approximately 30%, the survey was not anonymous, and many reputationally prominent academic hospitalist programs were represented. For these reasons, the group members felt that the survey results were relevant for the purposes of assessing academic success.

In the LAHP‐50, funding was defined as principal investigator or coinvestigator roles on federally and nonfederally funded research, clinical trials, internal grants, and any other extramurally funded projects. Mean and median funding for the overall sample was calculated. Through a separate question, each program's total faculty full‐time equivalent (FTE) count was reported, allowing us to adjust for group size by assessing both total funding per group and funding/FTE for each responding AHP.

Promotions were defined by the self‐reported number of faculty at each of the following ranks: instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, full professor, and professor above scale/emeritus. In addition, a category of nonacademic track (eg, adjunct faculty, clinical associate) was included to capture hospitalists that did not fit into the traditional promotions categories. We did not distinguish between tenure‐track and nontenure‐track academic ranks. LAHP‐50 survey respondents reported the number of faculty in their group at each academic rank. Given that the majority of academic hospitalists hold a rank of assistant professor or lower,[6, 8, 9] and that the number of full professors was only 3% in the LAHP‐50 cohort, we combined the faculty at the associate and full professor ranks, defining successfully promoted faculty as the percent of hospitalists above the rank of assistant professor.

We created a new metric to assess scholarly output. We had considerable discussion of ways to assess the numbers of peer‐reviewed manuscripts generated by AHPs. However, the group had concerns about the feasibility of identification and attribution of authors to specific AHPs through literature searches. We considered examining only publications in the Journal of Hospital Medicine and the Journal of General Internal Medicine, but felt that this would exclude significant work published by hospitalists in fields of medical education or health services research that would more likely appear in alternate journals. Instead, we quantified scholarship based on the number of abstracts presented at national meetings. We focused on meetings of the SHM and SGIM as the primary professional societies representing hospital medicine. The group felt that even work published outside of the journals of our professional societies would likely be presented at those meetings. We used the following strategy: We reviewed research abstracts accepted for presentation as posters or oral abstracts at the 2010 and 2011 SHM national meetings, and research abstracts with a primary or secondary category of hospital medicine at the 2010 and 2011 SGIM national meetings. By including submissions at both SGIM and SHM meetings, we accounted for the fact that some programs may gravitate more to one society meeting or another. We did not include abstracts in the clinical vignettes or innovations categories. We tallied the number of abstracts by group affiliation of the authors for each of the 4 meetings above and created a cumulative total per group for the 2‐year period. Abstracts with authors from different AHPs were counted once for each individual group. Members of the study group reviewed abstracts from each of the meetings in pairs. Reviewers worked separately and compared tallies of results to ensure consistent tabulations. Internet searches were conducted to identify or confirm author affiliations if it was not apparent in the abstract author list. Abstract tallies were compiled without regard to whether programs had completed the LAHP‐50 survey; thus, we collected data on programs that did not respond to the LAHP‐50 survey.

Identification of the SCHOLAR Cohort

To identify our cohort of top‐performing AHPs, we combined the funding and promotions data from the LAHP‐50 sample with the abstract data. We limited our sample to adult hospital medicine groups to reduce heterogeneity. We created rank lists of programs in each category (grant funding, successful promotions, and scholarship), using data from the LAHP‐50 survey to rank programs on funding and promotions, and data from our abstract counts to rank on scholarship. We limited the top‐performing list in each category to 10 institutions as a cutoff. Because we set a threshold of at least $1 million in total funding, we identified only 9 top performing AHPs with regard to grant funding. We also calculated mean funding/FTE. We chose to rank programs only by funding/FTE rather than total funding per program to better account for group size. For successful promotions, we ranked programs by the percentage of senior faculty. For abstract counts, we included programs whose faculty presented abstracts at a minimum of 2 separate meetings, and ranked programs based on the total number of abstracts per group.

This process resulted in separate lists of top performing programs in each of the 3 domains we associated with academic success, arranged in descending order by grant dollars/FTE, percent of senior faculty, and abstract counts (Table 1). Seventeen different programs were represented across these 3 top 10 lists. One program appeared on all 3 lists, 8 programs appeared on 2 lists, and the remainder appeared on a single list (Table 2). Seven of these programs were identified solely based on abstract presentations, diversifying our top groups beyond only those who completed the LAHP‐50 survey. We considered all of these programs to represent high performance in academic hospital medicine. The group selected this inclusive approach because we recognized that any 1 metric was potentially limited, and we sought to identify diverse pathways to success.

| Funding | Promotions | Scholarship | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grant $/FTE | Total Grant $ | Senior Faculty, No. (%) | Total Abstract Count |

| |||

| $1,409,090 | $15,500,000 | 3 (60%) | 23 |

| $1,000,000 | $9,000,000 | 3 (60%) | 21 |

| $750,000 | $8,000,000 | 4 (57%) | 20 |

| $478,609 | $6,700,535 | 9 (53%) | 15 |

| $347,826 | $3,000,000 | 8 (44%) | 11 |

| $86,956 | $3,000,000 | 14 (41%) | 11 |

| $66,666 | $2,000,000 | 17 (36%) | 10 |

| $46,153 | $1,500,000 | 9 (33%) | 10 |

| $38,461 | $1,000,000 | 2 (33%) | 9 |

| 4 (31%) | 9 | ||

| Selection Criteria for SCHOLAR Cohort | No. of Programs |

|---|---|

| |

| Abstracts, funding, and promotions | 1 |

| Abstracts plus promotions | 4 |

| Abstracts plus funding | 3 |

| Funding plus promotion | 1 |

| Funding only | 1 |

| Abstract only | 7 |

| Total | 17 |

| Top 10 abstract count | |

| 4 meetings | 2 |

| 3 meetings | 2 |

| 2 meetings | 6 |

The 17 unique adult AHPs appearing on at least 1 of the top 10 lists comprised the SCHOLAR cohort of programs that we studied in greater detail. Data reflecting program demographics were solicited directly from leaders of the AHPs identified in the SCHOLAR cohort, including size and age of program, reporting structure, number of faculty at various academic ranks (for programs that did not complete the LAHP‐50 survey), and number of faculty with fellowship training (defined as any postresidency fellowship program).

Subsequently, we performed comparative analyses between the programs in the SCHOLAR cohort to the general population of AHPs reflected by the LAHP‐50 sample. Because abstract presentations were not recorded in the original LAHP‐50 survey instrument, it was not possible to perform a benchmarking comparison for the scholarship domain.

Data Analysis

To measure the success of the SCHOLAR cohort we compared the grant funding and proportion of successfully promoted faculty at the SCHOLAR programs to those in the overall LAHP‐50 sample. Differences in mean and median grant funding were compared using t tests and Mann‐Whitney rank sum tests. Proportion of promoted faculty were compared using 2 tests. A 2‐tailed of 0.05 was used to test significance of differences.

RESULTS

Demographics

Among the AHPs in the SCHOLAR cohort, the mean program age was 13.2 years (range, 618 years), and the mean program size was 36 faculty (range, 1895; median, 28). On average, 15% of faculty members at SCHOLAR programs were fellowship trained (range, 0%37%). Reporting structure among the SCHOLAR programs was as follows: 53% were an independent division or section of the department of medicine; 29% were a section within general internal medicine, and 18% were an independent clinical group.

Grant Funding

Table 3 compares grant funding in the SCHOLAR programs to programs in the overall LAHP‐50 sample. Mean funding per group and mean funding per FTE were significantly higher in the SCHOLAR group than in the overall sample.

| Funding (Millions) | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAHP‐50 Overall Sample | SCHOLAR | |

| ||

| Median grant funding/AHP | 0.060 | 1.500* |

| Mean grant funding/AHP | 1.147 (015) | 3.984* (015) |

| Median grant funding/FTE | 0.004 | 0.038* |

| Mean grant funding/FTE | 0.095 (01.4) | 0.364* (01.4) |

Thirteen of the SCHOLAR programs were represented in the initial LAHP‐50, but 2 did not report a dollar amount for grants and contracts. Therefore, data for total grant funding were available for only 65% (11 of 17) of the programs in the SCHOLAR cohort. Of note, 28% of AHPs in the overall LAHP‐50 sample reported no external funding sources.

Faculty Promotion

Figure 1 demonstrates the proportion of faculty at various academic ranks. The percent of faculty above the rank of assistant professor in the SCHOLAR programs exceeded those in the overall LAHP‐50 by 5% (17.9% vs 12.8%, P = 0.01). Of note, 6% of the hospitalists at AHPs in the SCHOLAR programs were on nonfaculty tracks.

Scholarship

Mean abstract output over the 2‐year period measured was 10.8 (range, 323) in the SCHOLAR cohort. Because we did not collect these data for the LAHP‐50 group, comparative analyses were not possible.

DISCUSSION

Using a definition of academic success that incorporated metrics of grant funding, faculty promotion, and scholarly output, we identified a unique subset of successful AHPsthe SCHOLAR cohort. The programs represented in the SCHOLAR cohort were generally large and relatively mature. Despite this, the cohort consisted of mostly junior faculty, had a paucity of fellowship‐trained hospitalists, and not all reported grant funding.

Prior published work reported complementary findings.[6, 8, 9] A survey of 20 large, well‐established academic hospitalist programs in 2008 found that the majority of hospitalists were junior faculty with a limited publication portfolio. Of the 266 respondents in that study, 86% reported an academic rank at or below assistant professor; funding was not explored.[9] Our similar findings 4 years later add to this work by demonstrating trends over time, and suggest that progress toward creating successful pathways for academic advancement has been slow. In a 2012 survey of the SHM membership, 28% of hospitalists with academic appointments reported no current or future plans to engage in research.[8] These findings suggest that faculty in AHPs may define scholarship through nontraditional pathways, or in some cases choose not to pursue or prioritize scholarship altogether.

Our findings also add to the literature with regard to our assessment of funding, which was variable across the SCHOLAR group. The broad range of funding in the SCHOLAR programs for which we have data (grant dollars $0$15 million per program) suggests that opportunities to improve supported scholarship remain, even among a selected cohort of successful AHPs. The predominance of junior faculty in the SCHOLAR programs may be a reason for this variation. Junior faculty may be engaged in research with funding directed to senior mentors outside their AHP. Alternatively, they may pursue meaningful local hospital quality improvement or educational innovations not supported by external grants, or hold leadership roles in education, quality, or information technology that allow for advancement and promotion without external grant funding. As the scope and impact of these roles increases, senior leaders with alternate sources of support may rely less on research funds; this too may explain some of the differences. Our findings are congruent with results of a study that reviewed original research published by hospitalists, and concluded that the majority of hospitalist research was not externally funded.[8] Our approach for assessing grant funding by adjusting for FTE had the potential to inadvertently favor smaller well‐funded groups over larger ones; however, programs in our sample were similarly represented when ranked by funding/FTE or total grant dollars. As many successful AHPs do concentrate their research funding among a core of focused hospitalist researchers, our definition may not be the ideal metric for some programs.

We chose to define scholarship based on abstract output, rather than peer‐reviewed publications. Although this choice was necessary from a feasibility perspective, it may have excluded programs that prioritize peer‐reviewed publications over abstracts. Although we were unable to incorporate a search strategy to accurately and comprehensively track the publication output attributed specifically to hospitalist researchers and quantify it by program, others have since defined such an approach.[8] However, tracking abstracts theoretically allowed insights into a larger volume of innovative and creative work generated by top AHPs by potentially including work in the earlier stages of development.

We used a consensus‐based definition of success to define our SCHOLAR cohort. There are other ways to measure academic success, which if applied, may have yielded a different sample of programs. For example, over half of the original research articles published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine over a 7‐year span were generated from 5 academic centers.[8] This definition of success may be equally credible, though we note that 4 of these 5 programs were also included in the SCHOLAR cohort. We feel our broader approach was more reflective of the variety of pathways to success available to academic hospitalists. Before our metrics are applied as a benchmarking tool, however, they should ideally be combined with factors not measured in our study to ensure a more comprehensive or balanced reflection of academic success. Factors such as mentorship, level of hospitalist engagement,[10] prevalence of leadership opportunities, operational and fiscal infrastructure, and the impact of local quality, safety, and value efforts should be considered.

Comparison of successfully promoted faculty at AHPs across the country is inherently limited by the wide variation in promotion standards across different institutions; controlling for such differences was not possible with our methodology. For example, it appears that several programs with relatively few senior faculty may have met metrics leading to their inclusion in the SCHOLAR group because of their small program size. Future benchmarking efforts for promotion at AHPs should take scaling into account and consider both total number as well as percentage of senior faculty when evaluating success.

Our methodology has several limitations. Survey data were self‐reported and not independently validated, and as such are subject to recall and reporting biases. Response bias inherently excluded some AHPs that may have met our grant funding or promotions criteria had they participated in the initial LAHP‐50 survey, though we identified and included additional programs through our scholarship metric, increasing the representativeness of the SCHOLAR cohort. Given the dynamic nature of the field, the age of the data we relied upon for analysis limits the generalizability of our specific benchmarks to current practice. However, the development of academic success occurs over the long‐term, and published data on academic hospitalist productivity are consistent with this slower time course.[8] Despite these limitations, our data inform the general topic of gauging performance of AHPs, underscoring the challenges of developing and applying metrics of success, and highlight the variability of performance on selected metrics even among a relatively small group of 17 programs.

In conclusion, we have created a method to quantify academic success that may be useful to academic hospitalists and their group leaders as they set targets for improvement in the field. Even among our SCHOLAR cohort, room for ongoing improvement in development of funded scholarship and a core of senior faculty exists. Further investigation into the unique features of successful groups will offer insight to leaders in academic hospital medicine regarding infrastructure and processes that should be embraced to raise the bar for all AHPs. In addition, efforts to further define and validate nontraditional approaches to scholarship that allow for successful promotion at AHPs would be informative. We view our work less as a singular approach to benchmarking standards for AHPs, and more a call to action to continue efforts to balance scholarly activity and broad professional development of academic hospitalists with increasing clinical demands.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the AHP leaders who participated in the SCHOLAR project. They also thank the Society of Hospital Medicine and Society of General Internal Medicine and the SHM Academic Committee and SGIM Academic Hospitalist Task Force for their support of this work.

Disclosures

The work reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, South Texas Veterans Health Care System. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The structure and function of academic hospital medicine programs (AHPs) has evolved significantly with the growth of hospital medicine.[1, 2, 3, 4] Many AHPs formed in response to regulatory and financial changes, which drove demand for increased trainee oversight, improved clinical efficiency, and growth in nonteaching services staffed by hospitalists. Differences in local organizational contexts and needs have contributed to great variability in AHP program design and operations. As AHPs have become more established, the need to engage academic hospitalists in scholarship and activities that support professional development and promotion has been recognized. Defining sustainable and successful positions for academic hospitalists is a priority called for by leaders in the field.[5, 6]

In this rapidly evolving context, AHPs have employed a variety of approaches to organizing clinical and academic faculty roles, without guiding evidence or consensus‐based performance benchmarks. A number of AHPs have achieved success along traditional academic metrics of research, scholarship, and education. Currently, it is not known whether specific approaches to AHP organization, structure, or definition of faculty roles are associated with achievement of more traditional markers of academic success.

The Academic Committee of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), and the Academic Hospitalist Task Force of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) had separately initiated projects to explore characteristics associated with success in AHPs. In 2012, these organizations combined efforts to jointly develop and implement the SCHOLAR (SuCcessful HOspitaLists in Academics and Research) project. The goals were to identify successful AHPs using objective criteria, and to then study those groups in greater detail to generate insights that would be broadly relevant to the field. Efforts to clarify the factors within AHPs linked to success by traditional academic metrics will benefit hospitalists, their leaders, and key stakeholders striving to achieve optimal balance between clinical and academic roles. We describe the initial work of the SCHOLAR project, our definitions of academic success in AHPs, and the characteristics of a cohort of exemplary AHPs who achieved the highest levels on these metrics.

METHODS

Defining Success

The 11 members of the SCHOLAR project held a variety of clinical and academic roles within a geographically diverse group of AHPs. We sought to create a functional definition of success applicable to AHPs. As no gold standard currently exists, we used a consensus process among task force members to arrive at a definition that was quantifiable, feasible, and meaningful. The first step was brainstorming on conference calls held 1 to 2 times monthly over 4 months. Potential defining characteristics that emerged from these discussions related to research, teaching, and administrative activities. When potential characteristics were proposed, we considered how to operationalize each one. Each characteristic was discussed until there was consensus from the entire group. Those around education and administration were the most complex, as many roles are locally driven and defined, and challenging to quantify. For this reason, we focused on promotion as a more global approach to assessing academic hospitalist success in these areas. Although criteria for academic advancement also vary across institutions, we felt that promotion generally reflected having met some threshold of academic success. We also wanted to recognize that scholarship occurs outside the context of funded research. Ultimately, 3 key domains emerged: research grant funding, faculty promotion, and scholarship.

After these 3 domains were identified, the group sought to define quantitative metrics to assess performance. These discussions occurred on subsequent calls over a 4‐month period. Between calls, group members gathered additional information to facilitate assessment of the feasibility of proposed metrics, reporting on progress via email. Again, group consensus was sought for each metric considered. Data on grant funding and successful promotions were available from a previous survey conducted through the SHM in 2011. Leaders from 170 AHPs were contacted, with 50 providing complete responses to the 21‐item questionnaire (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). Results of the survey, heretofore referred to as the Leaders of Academic Hospitalist Programs survey (LAHP‐50), have been described elsewhere.[7] For the purposes of this study, we used the self‐reported data about grant funding and promotions contained in the survey to reflect the current state of the field. Although the survey response rate was approximately 30%, the survey was not anonymous, and many reputationally prominent academic hospitalist programs were represented. For these reasons, the group members felt that the survey results were relevant for the purposes of assessing academic success.

In the LAHP‐50, funding was defined as principal investigator or coinvestigator roles on federally and nonfederally funded research, clinical trials, internal grants, and any other extramurally funded projects. Mean and median funding for the overall sample was calculated. Through a separate question, each program's total faculty full‐time equivalent (FTE) count was reported, allowing us to adjust for group size by assessing both total funding per group and funding/FTE for each responding AHP.

Promotions were defined by the self‐reported number of faculty at each of the following ranks: instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, full professor, and professor above scale/emeritus. In addition, a category of nonacademic track (eg, adjunct faculty, clinical associate) was included to capture hospitalists that did not fit into the traditional promotions categories. We did not distinguish between tenure‐track and nontenure‐track academic ranks. LAHP‐50 survey respondents reported the number of faculty in their group at each academic rank. Given that the majority of academic hospitalists hold a rank of assistant professor or lower,[6, 8, 9] and that the number of full professors was only 3% in the LAHP‐50 cohort, we combined the faculty at the associate and full professor ranks, defining successfully promoted faculty as the percent of hospitalists above the rank of assistant professor.

We created a new metric to assess scholarly output. We had considerable discussion of ways to assess the numbers of peer‐reviewed manuscripts generated by AHPs. However, the group had concerns about the feasibility of identification and attribution of authors to specific AHPs through literature searches. We considered examining only publications in the Journal of Hospital Medicine and the Journal of General Internal Medicine, but felt that this would exclude significant work published by hospitalists in fields of medical education or health services research that would more likely appear in alternate journals. Instead, we quantified scholarship based on the number of abstracts presented at national meetings. We focused on meetings of the SHM and SGIM as the primary professional societies representing hospital medicine. The group felt that even work published outside of the journals of our professional societies would likely be presented at those meetings. We used the following strategy: We reviewed research abstracts accepted for presentation as posters or oral abstracts at the 2010 and 2011 SHM national meetings, and research abstracts with a primary or secondary category of hospital medicine at the 2010 and 2011 SGIM national meetings. By including submissions at both SGIM and SHM meetings, we accounted for the fact that some programs may gravitate more to one society meeting or another. We did not include abstracts in the clinical vignettes or innovations categories. We tallied the number of abstracts by group affiliation of the authors for each of the 4 meetings above and created a cumulative total per group for the 2‐year period. Abstracts with authors from different AHPs were counted once for each individual group. Members of the study group reviewed abstracts from each of the meetings in pairs. Reviewers worked separately and compared tallies of results to ensure consistent tabulations. Internet searches were conducted to identify or confirm author affiliations if it was not apparent in the abstract author list. Abstract tallies were compiled without regard to whether programs had completed the LAHP‐50 survey; thus, we collected data on programs that did not respond to the LAHP‐50 survey.

Identification of the SCHOLAR Cohort

To identify our cohort of top‐performing AHPs, we combined the funding and promotions data from the LAHP‐50 sample with the abstract data. We limited our sample to adult hospital medicine groups to reduce heterogeneity. We created rank lists of programs in each category (grant funding, successful promotions, and scholarship), using data from the LAHP‐50 survey to rank programs on funding and promotions, and data from our abstract counts to rank on scholarship. We limited the top‐performing list in each category to 10 institutions as a cutoff. Because we set a threshold of at least $1 million in total funding, we identified only 9 top performing AHPs with regard to grant funding. We also calculated mean funding/FTE. We chose to rank programs only by funding/FTE rather than total funding per program to better account for group size. For successful promotions, we ranked programs by the percentage of senior faculty. For abstract counts, we included programs whose faculty presented abstracts at a minimum of 2 separate meetings, and ranked programs based on the total number of abstracts per group.

This process resulted in separate lists of top performing programs in each of the 3 domains we associated with academic success, arranged in descending order by grant dollars/FTE, percent of senior faculty, and abstract counts (Table 1). Seventeen different programs were represented across these 3 top 10 lists. One program appeared on all 3 lists, 8 programs appeared on 2 lists, and the remainder appeared on a single list (Table 2). Seven of these programs were identified solely based on abstract presentations, diversifying our top groups beyond only those who completed the LAHP‐50 survey. We considered all of these programs to represent high performance in academic hospital medicine. The group selected this inclusive approach because we recognized that any 1 metric was potentially limited, and we sought to identify diverse pathways to success.

| Funding | Promotions | Scholarship | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grant $/FTE | Total Grant $ | Senior Faculty, No. (%) | Total Abstract Count |

| |||

| $1,409,090 | $15,500,000 | 3 (60%) | 23 |

| $1,000,000 | $9,000,000 | 3 (60%) | 21 |

| $750,000 | $8,000,000 | 4 (57%) | 20 |

| $478,609 | $6,700,535 | 9 (53%) | 15 |

| $347,826 | $3,000,000 | 8 (44%) | 11 |

| $86,956 | $3,000,000 | 14 (41%) | 11 |

| $66,666 | $2,000,000 | 17 (36%) | 10 |

| $46,153 | $1,500,000 | 9 (33%) | 10 |

| $38,461 | $1,000,000 | 2 (33%) | 9 |

| 4 (31%) | 9 | ||

| Selection Criteria for SCHOLAR Cohort | No. of Programs |

|---|---|

| |

| Abstracts, funding, and promotions | 1 |

| Abstracts plus promotions | 4 |

| Abstracts plus funding | 3 |

| Funding plus promotion | 1 |

| Funding only | 1 |

| Abstract only | 7 |

| Total | 17 |

| Top 10 abstract count | |

| 4 meetings | 2 |

| 3 meetings | 2 |

| 2 meetings | 6 |

The 17 unique adult AHPs appearing on at least 1 of the top 10 lists comprised the SCHOLAR cohort of programs that we studied in greater detail. Data reflecting program demographics were solicited directly from leaders of the AHPs identified in the SCHOLAR cohort, including size and age of program, reporting structure, number of faculty at various academic ranks (for programs that did not complete the LAHP‐50 survey), and number of faculty with fellowship training (defined as any postresidency fellowship program).

Subsequently, we performed comparative analyses between the programs in the SCHOLAR cohort to the general population of AHPs reflected by the LAHP‐50 sample. Because abstract presentations were not recorded in the original LAHP‐50 survey instrument, it was not possible to perform a benchmarking comparison for the scholarship domain.

Data Analysis

To measure the success of the SCHOLAR cohort we compared the grant funding and proportion of successfully promoted faculty at the SCHOLAR programs to those in the overall LAHP‐50 sample. Differences in mean and median grant funding were compared using t tests and Mann‐Whitney rank sum tests. Proportion of promoted faculty were compared using 2 tests. A 2‐tailed of 0.05 was used to test significance of differences.

RESULTS

Demographics

Among the AHPs in the SCHOLAR cohort, the mean program age was 13.2 years (range, 618 years), and the mean program size was 36 faculty (range, 1895; median, 28). On average, 15% of faculty members at SCHOLAR programs were fellowship trained (range, 0%37%). Reporting structure among the SCHOLAR programs was as follows: 53% were an independent division or section of the department of medicine; 29% were a section within general internal medicine, and 18% were an independent clinical group.

Grant Funding

Table 3 compares grant funding in the SCHOLAR programs to programs in the overall LAHP‐50 sample. Mean funding per group and mean funding per FTE were significantly higher in the SCHOLAR group than in the overall sample.

| Funding (Millions) | ||

|---|---|---|

| LAHP‐50 Overall Sample | SCHOLAR | |

| ||

| Median grant funding/AHP | 0.060 | 1.500* |

| Mean grant funding/AHP | 1.147 (015) | 3.984* (015) |

| Median grant funding/FTE | 0.004 | 0.038* |

| Mean grant funding/FTE | 0.095 (01.4) | 0.364* (01.4) |

Thirteen of the SCHOLAR programs were represented in the initial LAHP‐50, but 2 did not report a dollar amount for grants and contracts. Therefore, data for total grant funding were available for only 65% (11 of 17) of the programs in the SCHOLAR cohort. Of note, 28% of AHPs in the overall LAHP‐50 sample reported no external funding sources.

Faculty Promotion

Figure 1 demonstrates the proportion of faculty at various academic ranks. The percent of faculty above the rank of assistant professor in the SCHOLAR programs exceeded those in the overall LAHP‐50 by 5% (17.9% vs 12.8%, P = 0.01). Of note, 6% of the hospitalists at AHPs in the SCHOLAR programs were on nonfaculty tracks.

Scholarship

Mean abstract output over the 2‐year period measured was 10.8 (range, 323) in the SCHOLAR cohort. Because we did not collect these data for the LAHP‐50 group, comparative analyses were not possible.

DISCUSSION

Using a definition of academic success that incorporated metrics of grant funding, faculty promotion, and scholarly output, we identified a unique subset of successful AHPsthe SCHOLAR cohort. The programs represented in the SCHOLAR cohort were generally large and relatively mature. Despite this, the cohort consisted of mostly junior faculty, had a paucity of fellowship‐trained hospitalists, and not all reported grant funding.

Prior published work reported complementary findings.[6, 8, 9] A survey of 20 large, well‐established academic hospitalist programs in 2008 found that the majority of hospitalists were junior faculty with a limited publication portfolio. Of the 266 respondents in that study, 86% reported an academic rank at or below assistant professor; funding was not explored.[9] Our similar findings 4 years later add to this work by demonstrating trends over time, and suggest that progress toward creating successful pathways for academic advancement has been slow. In a 2012 survey of the SHM membership, 28% of hospitalists with academic appointments reported no current or future plans to engage in research.[8] These findings suggest that faculty in AHPs may define scholarship through nontraditional pathways, or in some cases choose not to pursue or prioritize scholarship altogether.

Our findings also add to the literature with regard to our assessment of funding, which was variable across the SCHOLAR group. The broad range of funding in the SCHOLAR programs for which we have data (grant dollars $0$15 million per program) suggests that opportunities to improve supported scholarship remain, even among a selected cohort of successful AHPs. The predominance of junior faculty in the SCHOLAR programs may be a reason for this variation. Junior faculty may be engaged in research with funding directed to senior mentors outside their AHP. Alternatively, they may pursue meaningful local hospital quality improvement or educational innovations not supported by external grants, or hold leadership roles in education, quality, or information technology that allow for advancement and promotion without external grant funding. As the scope and impact of these roles increases, senior leaders with alternate sources of support may rely less on research funds; this too may explain some of the differences. Our findings are congruent with results of a study that reviewed original research published by hospitalists, and concluded that the majority of hospitalist research was not externally funded.[8] Our approach for assessing grant funding by adjusting for FTE had the potential to inadvertently favor smaller well‐funded groups over larger ones; however, programs in our sample were similarly represented when ranked by funding/FTE or total grant dollars. As many successful AHPs do concentrate their research funding among a core of focused hospitalist researchers, our definition may not be the ideal metric for some programs.

We chose to define scholarship based on abstract output, rather than peer‐reviewed publications. Although this choice was necessary from a feasibility perspective, it may have excluded programs that prioritize peer‐reviewed publications over abstracts. Although we were unable to incorporate a search strategy to accurately and comprehensively track the publication output attributed specifically to hospitalist researchers and quantify it by program, others have since defined such an approach.[8] However, tracking abstracts theoretically allowed insights into a larger volume of innovative and creative work generated by top AHPs by potentially including work in the earlier stages of development.

We used a consensus‐based definition of success to define our SCHOLAR cohort. There are other ways to measure academic success, which if applied, may have yielded a different sample of programs. For example, over half of the original research articles published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine over a 7‐year span were generated from 5 academic centers.[8] This definition of success may be equally credible, though we note that 4 of these 5 programs were also included in the SCHOLAR cohort. We feel our broader approach was more reflective of the variety of pathways to success available to academic hospitalists. Before our metrics are applied as a benchmarking tool, however, they should ideally be combined with factors not measured in our study to ensure a more comprehensive or balanced reflection of academic success. Factors such as mentorship, level of hospitalist engagement,[10] prevalence of leadership opportunities, operational and fiscal infrastructure, and the impact of local quality, safety, and value efforts should be considered.

Comparison of successfully promoted faculty at AHPs across the country is inherently limited by the wide variation in promotion standards across different institutions; controlling for such differences was not possible with our methodology. For example, it appears that several programs with relatively few senior faculty may have met metrics leading to their inclusion in the SCHOLAR group because of their small program size. Future benchmarking efforts for promotion at AHPs should take scaling into account and consider both total number as well as percentage of senior faculty when evaluating success.

Our methodology has several limitations. Survey data were self‐reported and not independently validated, and as such are subject to recall and reporting biases. Response bias inherently excluded some AHPs that may have met our grant funding or promotions criteria had they participated in the initial LAHP‐50 survey, though we identified and included additional programs through our scholarship metric, increasing the representativeness of the SCHOLAR cohort. Given the dynamic nature of the field, the age of the data we relied upon for analysis limits the generalizability of our specific benchmarks to current practice. However, the development of academic success occurs over the long‐term, and published data on academic hospitalist productivity are consistent with this slower time course.[8] Despite these limitations, our data inform the general topic of gauging performance of AHPs, underscoring the challenges of developing and applying metrics of success, and highlight the variability of performance on selected metrics even among a relatively small group of 17 programs.

In conclusion, we have created a method to quantify academic success that may be useful to academic hospitalists and their group leaders as they set targets for improvement in the field. Even among our SCHOLAR cohort, room for ongoing improvement in development of funded scholarship and a core of senior faculty exists. Further investigation into the unique features of successful groups will offer insight to leaders in academic hospital medicine regarding infrastructure and processes that should be embraced to raise the bar for all AHPs. In addition, efforts to further define and validate nontraditional approaches to scholarship that allow for successful promotion at AHPs would be informative. We view our work less as a singular approach to benchmarking standards for AHPs, and more a call to action to continue efforts to balance scholarly activity and broad professional development of academic hospitalists with increasing clinical demands.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the AHP leaders who participated in the SCHOLAR project. They also thank the Society of Hospital Medicine and Society of General Internal Medicine and the SHM Academic Committee and SGIM Academic Hospitalist Task Force for their support of this work.

Disclosures

The work reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, South Texas Veterans Health Care System. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , . Characteristics of primary care providers who adopted the hospitalist model from 2001 to 2009. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):75–82.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , , , , . Updating threshold‐based identification of hospitalists in 2012 Medicare pay data. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):45–47.

- , , , . Use of hospitalists by Medicare beneficiaries: a national picture. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(2).

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in Academic Hospital Medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):240–246.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5–9.

- , , , , , . The structure of hospital medicine programs at academic medical centers [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(suppl 2):s92.

- , , , , . Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148–154.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , , , et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123–128.

- , , , , . Characteristics of primary care providers who adopted the hospitalist model from 2001 to 2009. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):75–82.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , , , , . Updating threshold‐based identification of hospitalists in 2012 Medicare pay data. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):45–47.

- , , , . Use of hospitalists by Medicare beneficiaries: a national picture. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(2).

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in Academic Hospital Medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):240–246.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):5–9.

- , , , , , . The structure of hospital medicine programs at academic medical centers [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(suppl 2):s92.

- , , , , . Research and publication trends in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):148–154.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , , , et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123–128.

Survey of Hospitalist Supervision

In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) announced the first in a series of guidelines related to the regulation and oversight of residency training.1 The initial iteration specifically focused on the total and consecutive numbers of duty hours worked by trainees. These limitations began a new era of shift work in internal medicine residency training. With decreases in housestaff admitting capacity, clinical work has frequently been offloaded to non‐teaching or attending‐only services, increasing the demand for hospitalists to fill the void in physician‐staffed care in the hospital.2, 3 Since the implementation of the 2003 ACGME guidelines and a growing focus on patient safety, there has been increased study of, and call for, oversight of trainees in medicine; among these was the 2008 Institute of Medicine report,4 calling for 24/7 attending‐level supervision. The updated ACGME requirements,5 effective July 1, 2011, mandate enhanced on‐site supervision of trainee physicians. These new regulations not only define varying levels of supervision for trainees, including direct supervision with the physical presence of a supervisor and the degree of availability of said supervisor, they also describe ensuring the quality of supervision provided.5 While continuous attending‐level supervision is not yet mandated, many residency programs look to their academic hospitalists to fill the supervisory void, particularly at night. However, what specific roles hospitalists play in the nighttime supervision of trainees or the impact of this supervision remains unclear. To date, no study has examined a broad sample of hospitalist programs in teaching hospitals and the types of resident oversight they provide. We aimed to describe the current state of academic hospitalists in the clinical supervision of housestaff, specifically during the overnight period, and hospitalist perceptions of how the new ACGME requirements would impact traineehospitalist interactions.

METHODS

The Housestaff Oversight Subcommittee, a working group of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) Academic Hospitalist Task Force, surveyed a sample of academic hospitalist program leaders to assess the current status of trainee supervision performed by hospitalists. Programs were considered academic if they were located in the primary hospital of a residency that participates in the National Resident Matching Program for Internal Medicine. To obtain a broad geographic spectrum of academic hospitalist programs, all programs, both university and community‐based, in 4 states and 2 metropolitan regions were sampled: Washington, Oregon, Texas, Maryland, and the Philadelphia and Chicago metropolitan areas. Hospitalist program leaders were identified by members of the Taskforce using individual program websites and by querying departmental leadership at eligible teaching hospitals. Respondents were contacted by e‐mail for participation. None of the authors of the manuscript were participants in the survey.

The survey was developed by consensus of the working group after reviewing the salient literature and included additional questions queried to internal medicine program directors.6 The 19‐item SurveyMonkey instrument included questions about hospitalists' role in trainees' education and evaluation. A Likert‐type scale was used to assess perceptions regarding the impact of on‐site hospitalist supervision on trainee autonomy and hospitalist workload (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Descriptive statistics were performed and, where appropriate, t test and Fisher's exact test were performed to identify associations between program characteristics and perceptions. Stata SE was used (STATA Corp, College Station, TX) for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

The survey was sent to 47 individuals identified as likely hospitalist program leaders and completed by 41 individuals (87%). However, 7 respondents turned out not to be program leaders and were therefore excluded, resulting in a 72% (34/47) survey response rate.

The programs for which we did not obtain responses were similar to respondent programs, and did not include a larger proportion of community‐based programs or overrepresent a specific geographic region. Twenty‐five (73%) of the 34 hospitalist program leaders were male, with an average age of 44.3 years, and an average of 12 years post‐residency training (range, 530 years). They reported leading groups with an average of 18 full‐time equivalent (FTE) faculty (range, 350 persons).

Relationship of Hospitalist Programs With the Residency Program