User login

Are there perinatal benefits to pregnant patients after bariatric surgery?

Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Perinatal outcomes after bariatric surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00771-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021 .06.087.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Prepregnancy obesity continues to rise in the United States, with a prevalence of 29% among reproductive-age women in 2019, an 11% increase from 2016.1 Pregnant patients with obesity are at increased risk for multiple adverse perinatal outcomes, including gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Bariatric surgery is effective for weight loss and has been shown to improve comorbidities associated with obesity,2 and it may have potential benefits for pregnancy outcomes, such as reducing rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia.3-5 However, little was known about other outcomes as well as other potential factors before a recent study in which investigators examined perinatal outcomes after bariatric surgery.

Details of the study

Getahun and colleagues conducted a population-based, retrospective study of pregnant patients who were eligible for bariatric surgery (body mass index [BMI] ≥40 kg/m2 with no comorbidities or a BMI between 35 and 40 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities, such as diabetes). They aimed to evaluate the association of bariatric surgery with adverse perinatal outcomes.

Results. In a large sample of pregnant patients eligible for bariatric surgery (N = 20,213), the authors found that patients who had bariatric surgery (n = 1,886) had a reduced risk of macrosomia (aOR, 0.24), preeclampsia (aOR, 0.53), gestational diabetes (aOR, 0.60), and cesarean delivery (aOR, 0.65) compared with those who did not have bariatric surgery (n = 18,327). They also found that patients who had bariatric surgery had an increased risk of small-for-gestational age neonates (aOR, 2.46) and postpartum hemorrhage (aOR, 1.79).

These results remained after adjusting for other potential confounders. The authors evaluated the outcomes based on the timing of surgery and the patients’ pregnancy (<1 year, 1-1.5 years, 1.5-2 years, >2 years). The outcomes were more favorable among the patients who had the bariatric surgery regardless of the time interval of surgery to pregnancy than those who did not have the surgery. In addition, the benefits of bariatric surgery did not differ between the 2 most common types of bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy) performed in this study, and both had better outcomes than those who did not have the surgery. Finally, patients with chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes who had bariatric surgery also had lower risks of adverse outcomes than those without bariatric surgery.

Study strengths and limitations

Given the study’s retrospective design, uncertainties and important confounders could not be addressed, such as why certain eligible patients had the surgery and others did not. However, with its large sample size and an appropriate comparison group, the study findings further support the perinatal benefits of bariatric surgery in obese patients. Of note, this study also had a large sample of Black and Hispanic patients, populations known to have higher rates of obesity1 and pregnancy complications. Subgroup analyses within each racial/ethnic group revealed that those who had the surgery had lower risks of adverse perinatal outcomes than those who did not.

Patients who had the bariatric surgery had an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage; however, there is no physiologic basis or theory to explain this finding, so further studies are needed. Lastly, although patients who had bariatric surgery had an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies and the study was not powered for the risk of stillbirth, the patients who had the surgery had a reduced risk of neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. More data would have been beneficial to assess if these small-for-gestational-age babies were healthy. In general, obese patients tend to have larger and unhealthy babies; thus, healthier babies, even if small for gestational age, would not be an adverse outcome.

Benefits of bariatric surgery extend to perinatal outcomes

This study reinforces current practice that includes eligible patients being counseled about the health-related benefits of bariatric surgery, which now includes more perinatal outcomes. The finding of the increased risk of small-for-gestational-age fetuses supports the practice of a screening growth ultrasound exam in patients who had bariatric surgery. ●

An important, modifiable risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes is the patient’s prepregnancy BMI at the time of pregnancy. Bariatric surgery is an effective procedure for weight loss. There are many perinatal benefits for eligible patients who have bariatric surgery before pregnancy. Clinicians should counsel their obese patients who are considering or planning pregnancy about the benefits of bariatric surgery.

RODNEY A. MCLAREN, JR, MD, AND VINCENZO BERGHELLA, MD

- Driscoll AK, Gregory ECW. Increases in prepregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2020 Nov;(392):1-8.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724- 1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724.

- Maggard MA, Yermilov I, Li Z, et al. Pregnancy and fertility following bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300:2286-2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.641.

- Watanabe A, Seki Y, Haruta H, et al. Maternal impacts and perinatal outcomes after three types of bariatric surgery at a single institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:145-152. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05195-9.

- Balestrin B, Urbanetz AA, Barbieri MM, et al. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: a comparative study of post-bariatric pregnant women versus non-bariatric obese pregnant women. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3142-3148. doi: 10.1007/s11695- 019-03961-x.

Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Perinatal outcomes after bariatric surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00771-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021 .06.087.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Prepregnancy obesity continues to rise in the United States, with a prevalence of 29% among reproductive-age women in 2019, an 11% increase from 2016.1 Pregnant patients with obesity are at increased risk for multiple adverse perinatal outcomes, including gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Bariatric surgery is effective for weight loss and has been shown to improve comorbidities associated with obesity,2 and it may have potential benefits for pregnancy outcomes, such as reducing rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia.3-5 However, little was known about other outcomes as well as other potential factors before a recent study in which investigators examined perinatal outcomes after bariatric surgery.

Details of the study

Getahun and colleagues conducted a population-based, retrospective study of pregnant patients who were eligible for bariatric surgery (body mass index [BMI] ≥40 kg/m2 with no comorbidities or a BMI between 35 and 40 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities, such as diabetes). They aimed to evaluate the association of bariatric surgery with adverse perinatal outcomes.

Results. In a large sample of pregnant patients eligible for bariatric surgery (N = 20,213), the authors found that patients who had bariatric surgery (n = 1,886) had a reduced risk of macrosomia (aOR, 0.24), preeclampsia (aOR, 0.53), gestational diabetes (aOR, 0.60), and cesarean delivery (aOR, 0.65) compared with those who did not have bariatric surgery (n = 18,327). They also found that patients who had bariatric surgery had an increased risk of small-for-gestational age neonates (aOR, 2.46) and postpartum hemorrhage (aOR, 1.79).

These results remained after adjusting for other potential confounders. The authors evaluated the outcomes based on the timing of surgery and the patients’ pregnancy (<1 year, 1-1.5 years, 1.5-2 years, >2 years). The outcomes were more favorable among the patients who had the bariatric surgery regardless of the time interval of surgery to pregnancy than those who did not have the surgery. In addition, the benefits of bariatric surgery did not differ between the 2 most common types of bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy) performed in this study, and both had better outcomes than those who did not have the surgery. Finally, patients with chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes who had bariatric surgery also had lower risks of adverse outcomes than those without bariatric surgery.

Study strengths and limitations

Given the study’s retrospective design, uncertainties and important confounders could not be addressed, such as why certain eligible patients had the surgery and others did not. However, with its large sample size and an appropriate comparison group, the study findings further support the perinatal benefits of bariatric surgery in obese patients. Of note, this study also had a large sample of Black and Hispanic patients, populations known to have higher rates of obesity1 and pregnancy complications. Subgroup analyses within each racial/ethnic group revealed that those who had the surgery had lower risks of adverse perinatal outcomes than those who did not.

Patients who had the bariatric surgery had an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage; however, there is no physiologic basis or theory to explain this finding, so further studies are needed. Lastly, although patients who had bariatric surgery had an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies and the study was not powered for the risk of stillbirth, the patients who had the surgery had a reduced risk of neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. More data would have been beneficial to assess if these small-for-gestational-age babies were healthy. In general, obese patients tend to have larger and unhealthy babies; thus, healthier babies, even if small for gestational age, would not be an adverse outcome.

Benefits of bariatric surgery extend to perinatal outcomes

This study reinforces current practice that includes eligible patients being counseled about the health-related benefits of bariatric surgery, which now includes more perinatal outcomes. The finding of the increased risk of small-for-gestational-age fetuses supports the practice of a screening growth ultrasound exam in patients who had bariatric surgery. ●

An important, modifiable risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes is the patient’s prepregnancy BMI at the time of pregnancy. Bariatric surgery is an effective procedure for weight loss. There are many perinatal benefits for eligible patients who have bariatric surgery before pregnancy. Clinicians should counsel their obese patients who are considering or planning pregnancy about the benefits of bariatric surgery.

RODNEY A. MCLAREN, JR, MD, AND VINCENZO BERGHELLA, MD

Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Perinatal outcomes after bariatric surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;S0002-9378(21)00771-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021 .06.087.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Prepregnancy obesity continues to rise in the United States, with a prevalence of 29% among reproductive-age women in 2019, an 11% increase from 2016.1 Pregnant patients with obesity are at increased risk for multiple adverse perinatal outcomes, including gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Bariatric surgery is effective for weight loss and has been shown to improve comorbidities associated with obesity,2 and it may have potential benefits for pregnancy outcomes, such as reducing rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia.3-5 However, little was known about other outcomes as well as other potential factors before a recent study in which investigators examined perinatal outcomes after bariatric surgery.

Details of the study

Getahun and colleagues conducted a population-based, retrospective study of pregnant patients who were eligible for bariatric surgery (body mass index [BMI] ≥40 kg/m2 with no comorbidities or a BMI between 35 and 40 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities, such as diabetes). They aimed to evaluate the association of bariatric surgery with adverse perinatal outcomes.

Results. In a large sample of pregnant patients eligible for bariatric surgery (N = 20,213), the authors found that patients who had bariatric surgery (n = 1,886) had a reduced risk of macrosomia (aOR, 0.24), preeclampsia (aOR, 0.53), gestational diabetes (aOR, 0.60), and cesarean delivery (aOR, 0.65) compared with those who did not have bariatric surgery (n = 18,327). They also found that patients who had bariatric surgery had an increased risk of small-for-gestational age neonates (aOR, 2.46) and postpartum hemorrhage (aOR, 1.79).

These results remained after adjusting for other potential confounders. The authors evaluated the outcomes based on the timing of surgery and the patients’ pregnancy (<1 year, 1-1.5 years, 1.5-2 years, >2 years). The outcomes were more favorable among the patients who had the bariatric surgery regardless of the time interval of surgery to pregnancy than those who did not have the surgery. In addition, the benefits of bariatric surgery did not differ between the 2 most common types of bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy) performed in this study, and both had better outcomes than those who did not have the surgery. Finally, patients with chronic hypertension and pregestational diabetes who had bariatric surgery also had lower risks of adverse outcomes than those without bariatric surgery.

Study strengths and limitations

Given the study’s retrospective design, uncertainties and important confounders could not be addressed, such as why certain eligible patients had the surgery and others did not. However, with its large sample size and an appropriate comparison group, the study findings further support the perinatal benefits of bariatric surgery in obese patients. Of note, this study also had a large sample of Black and Hispanic patients, populations known to have higher rates of obesity1 and pregnancy complications. Subgroup analyses within each racial/ethnic group revealed that those who had the surgery had lower risks of adverse perinatal outcomes than those who did not.

Patients who had the bariatric surgery had an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage; however, there is no physiologic basis or theory to explain this finding, so further studies are needed. Lastly, although patients who had bariatric surgery had an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies and the study was not powered for the risk of stillbirth, the patients who had the surgery had a reduced risk of neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. More data would have been beneficial to assess if these small-for-gestational-age babies were healthy. In general, obese patients tend to have larger and unhealthy babies; thus, healthier babies, even if small for gestational age, would not be an adverse outcome.

Benefits of bariatric surgery extend to perinatal outcomes

This study reinforces current practice that includes eligible patients being counseled about the health-related benefits of bariatric surgery, which now includes more perinatal outcomes. The finding of the increased risk of small-for-gestational-age fetuses supports the practice of a screening growth ultrasound exam in patients who had bariatric surgery. ●

An important, modifiable risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes is the patient’s prepregnancy BMI at the time of pregnancy. Bariatric surgery is an effective procedure for weight loss. There are many perinatal benefits for eligible patients who have bariatric surgery before pregnancy. Clinicians should counsel their obese patients who are considering or planning pregnancy about the benefits of bariatric surgery.

RODNEY A. MCLAREN, JR, MD, AND VINCENZO BERGHELLA, MD

- Driscoll AK, Gregory ECW. Increases in prepregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2020 Nov;(392):1-8.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724- 1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724.

- Maggard MA, Yermilov I, Li Z, et al. Pregnancy and fertility following bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300:2286-2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.641.

- Watanabe A, Seki Y, Haruta H, et al. Maternal impacts and perinatal outcomes after three types of bariatric surgery at a single institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:145-152. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05195-9.

- Balestrin B, Urbanetz AA, Barbieri MM, et al. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: a comparative study of post-bariatric pregnant women versus non-bariatric obese pregnant women. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3142-3148. doi: 10.1007/s11695- 019-03961-x.

- Driscoll AK, Gregory ECW. Increases in prepregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2020 Nov;(392):1-8.

- Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724- 1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724.

- Maggard MA, Yermilov I, Li Z, et al. Pregnancy and fertility following bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300:2286-2296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.641.

- Watanabe A, Seki Y, Haruta H, et al. Maternal impacts and perinatal outcomes after three types of bariatric surgery at a single institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;300:145-152. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05195-9.

- Balestrin B, Urbanetz AA, Barbieri MM, et al. Pregnancy after bariatric surgery: a comparative study of post-bariatric pregnant women versus non-bariatric obese pregnant women. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3142-3148. doi: 10.1007/s11695- 019-03961-x.

The One Step test: The better diagnostic approach for gestational diabetes mellitus

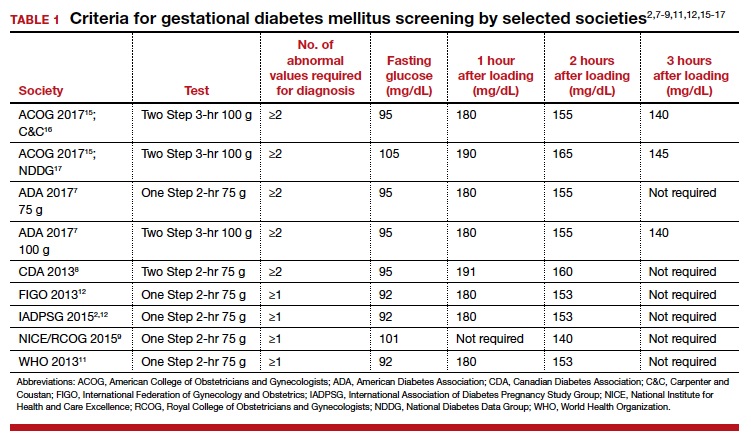

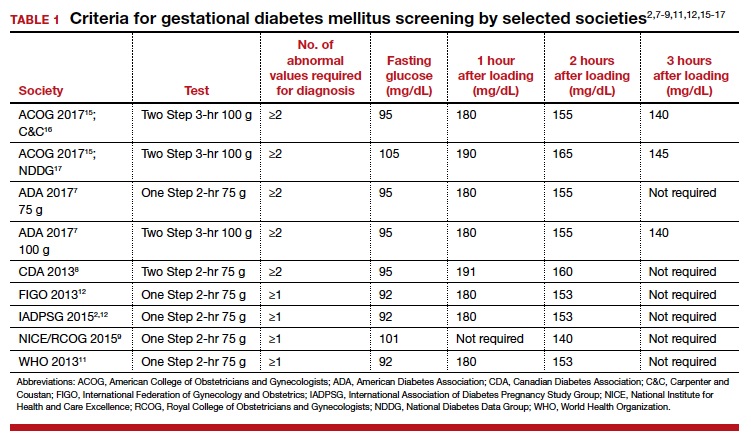

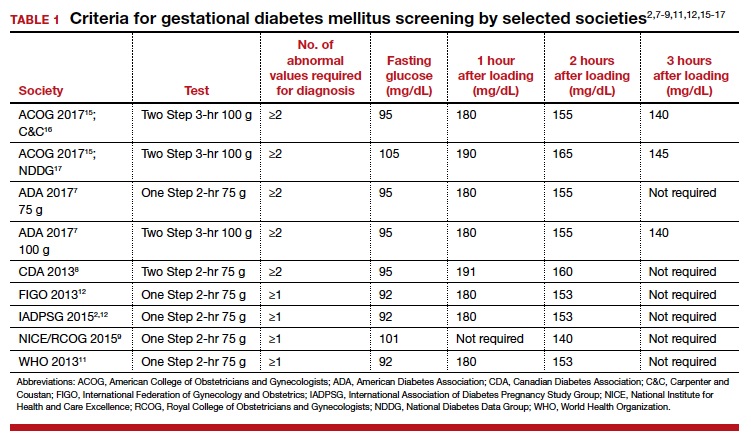

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) generally is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.1-14 The best approach and exact criteria to use for GDM screening and diagnosis are under worldwide debate. In TABLE 1 we present just some of the many differing suggestions by varying organizations.2,7-9,11,12,15-17 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for instance, suggests a Two Step approach to diagnosis.15 We will make the argument in this article, however, that diagnosis should be defined universally as an abnormal result with the One Step 75-g glucose testing, as adopted by the World Health Organization, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, and others. Approximately 8% of all pregnancies are complicated by GDM by the One Step test in the United States.18-22 The prevalence may range from 1% to 14% of all pregnancies, depending on the population studied and the diagnostic tests employed.1,19

Diagnostic options

Different methods for screening and diagnosis of GDM have been proposed by international societies; there is controversy regarding the diagnosis of GDM by either the One Step or the Two Step approach.6

The One Step approach includes an oral glucose tolerance test with a 75-g glucose load with measurement of plasma glucose concentration at fasting state and 1 hour and 2 hours post–glucose administration. A positive result for the One Step approach is defined as at least 1 measurement higher than 92, 180, or 153 mg/dL at fasting, 1 hour, or 2 hours, respectively.

The Two Step approach includes a nonfasting oral 50-g glucose load, with a glucose blood measurement 1 hour later. A positive screening, defined often as a blood glucose value higher than 135 mg/dL (range, 130 to 140 mg/dL), is followed by a diagnostic test with a 100-g glucose load with measurements at fasting and 1, 2, and 3 hours post–glucose administration. A positive diagnostic test is defined as 2 measurements higher than the target value.

Why we support the One Step test

There are several reasons to prefer the One Step approach for the diagnosis of GDM, compared with the Two Step approach.

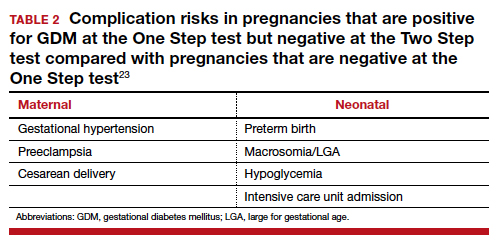

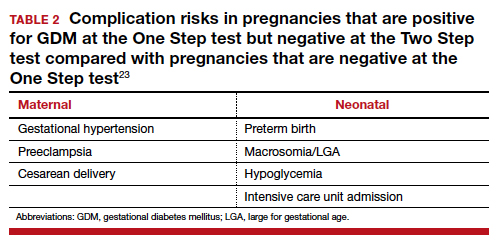

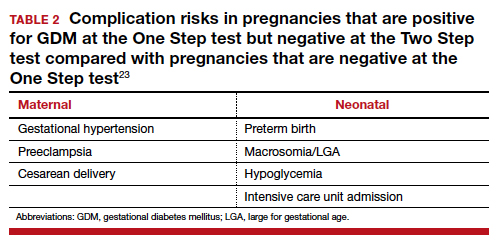

Women testing negative for GDM with Two Step still experience complications pregnancy. Women who test positive for GDM with the One Step test, but negative with the Two Step test, despite having therefore a milder degree of glucose intolerance, do have a higher risk of experiencing several complications.23 For the mother, these complications include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery. The baby also can experience problems at birth (TABLE 2).23 Therefore, women who test positive for GDM with the One Step test deserve to be diagnosed with and treated for the condition, as not only are they at risk for these complications but also treatment of the GDM decreases the incidence of these complications.18,19

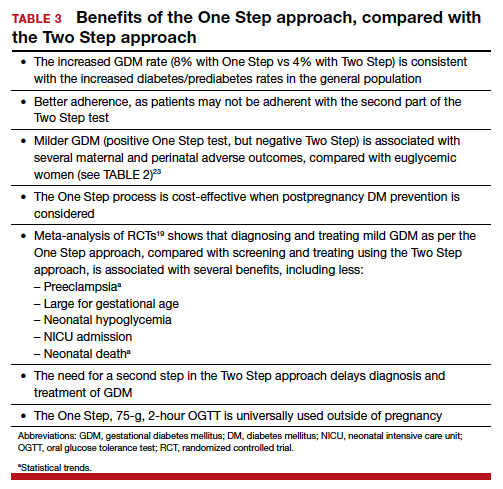

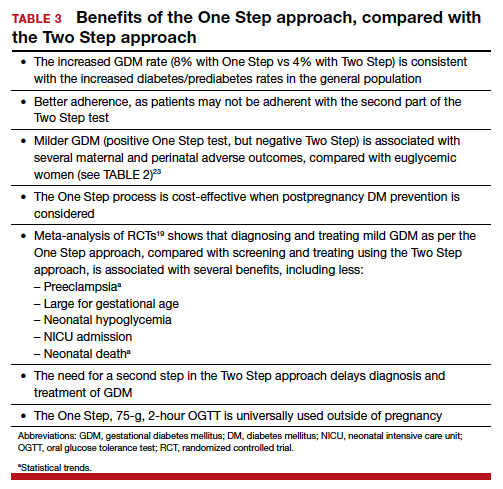

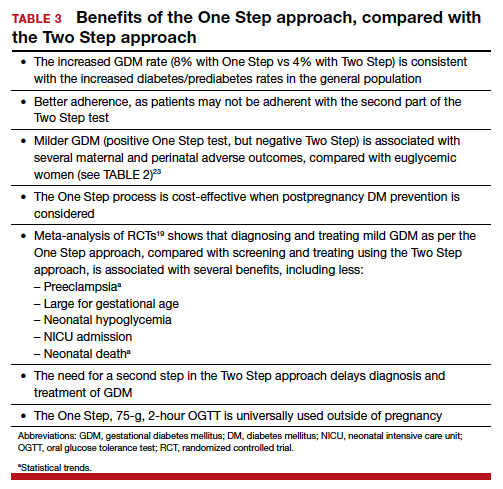

There is indeed an increased GDM diagnosis rate with the One Step (about 8%) compared with the Two Step test (about 4%). Nonetheless, this increase is mild and nonsignificant in the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs),18,19 is less than the 18% difference in diagnosis rate previously hypothesized, is consistent with the increased diabetes/prediabetes rates in the general population, and is linked to the increasing incidence of obesity and insulin resistance.

Overall test adherence is better. Five percent to 15% of patients, depending on the study, are not adherent with taking the second part of the Two Step test. Women indeed prefer the One Step approach; the second step in the Two Step approach may be a burden.

Less costly. The One Step process is cost-effective when postpregnancy diabetes mellitus prevention is considered.

Better maternal and perinatal outcomes. Probably the most important and convincing reason the One Step test should be used is that meta-analysis of the 4 RCTs comparing the approaches (including 2 US trials) shows that diagnosing and treating mild GDM as per the One Step approach, compared with screening and treating using the Two Step approach, is associated with increased incidence of GDM (8% vs 4%) and with better maternal and perinatal outcomes.13,18,19 In fact, the One Step approach is associated with significant reductions in: large for gestational age (56%), admission to neonatal intensive care unit (51%), and neonatal hypoglycemia (48%). Tests of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis and of quality all pointed to better outcomes in the One Step test group.13,19

The need for a second step in the Two Step approach delays diagnosis and treatment. The One Step approach is associated with an increase in GDM test adherence and earlier diagnosis,13 which is another reason for better outcomes with the One Step approach. In the presence of risk factors, such as prior GDM, prior macrosomia, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, and others, the One Step test should be done at the first prenatal visit.

Continue to: US guidelines should be reconsidered...

US guidelines should be reconsidered

The One Step, 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test is universally used to diagnose diabetes mellitus outside of pregnancy. Given our many noted reasons (TABLE 3), we recommend universal screening of GDM by using the One Step approach. It is time, indeed, for the United States to reconsider its guidelines for screening for GDM.

- Kampmann U, Madsen LR, Skajaa GO, et al. Gestational diabetes: a clinical update. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1065-1072.

- HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991-2002.

- Meltzer SJ, Snyder J, Penrod JR, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus screening and diagnosis: a prospective randomised controlled trial comparing costs of one-step and two-step methods. BJOG. 2010;117:407-415.

- Sevket O, Ates S, Uysal O, et al. To evaluate the prevalence and clinical outcomes using a one-step method versus a two-step method to screen gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:36-41.

- Scifres CM, Abebe KZ, Jones KA, et al. Gestational diabetes diagnostic methods (GD2M) pilot randomized trial. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1472-1480.

- Farrar D, Duley L, Medley N, et al. Different strategies for diagnosing gestational diabetes to improve maternal and infant health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD007122.

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S11-S24.

- Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes and Pregnancy. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(suppl 1):S168-S183.

- NICE guideline. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period. February 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3/. Last updated August 2015. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- WHO 1999. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. From http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66040/1/WHO

_NCD_NCS_99.2.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019. - World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85975/1/WHO_

NMH_MND_13.2_eng.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019. - Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(suppl 3):S173-S211.

- Berghella V, Caissutti C, Saccone G, et al. The One Step approach for diagnosing gestational diabetes is associated with better perinatal outcomes than using the Two Step approach: evidence of randomized clinical trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:562-564.

- Berghella V, Caissutti C, Saccone G, et al. One-Step approach to identifying gestational diabetes mellitus: association with perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:383.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 180: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e17-e31.

- Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:768-773.

- National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039-1057.

- Saccone G, Khalifeh A, Al-Kouatly HB, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: one step versus two step approach. A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-9.

- Saccone G, Caissutti C, Khalifeh A, et al. One step versus two step approach for gestational diabetes screening: systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1547-1555.

- Khalifeh A, Eckler R, Felder L, et al. One-step versus two-step diagnostic testing for gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-6.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Khalifeh A, et al. Which criteria should be used for starting pharmacologic therapy for management of gestational diabetes in pregnancy? Evidence from randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:2905-2914.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Ciardulli A, et al. Very tight vs. tight control: which should be the criteria for pharmacologic therapy dose adjustment in diabetes in pregnancy? Evidence from randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:235-247.

- Caissutti C, Khalifeh A, Saccone G, et al. Are women positive for the One Step but negative for the Two Step screening tests for gestational diabetes at higher risk for adverse outcomes? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:122-134.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) generally is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.1-14 The best approach and exact criteria to use for GDM screening and diagnosis are under worldwide debate. In TABLE 1 we present just some of the many differing suggestions by varying organizations.2,7-9,11,12,15-17 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for instance, suggests a Two Step approach to diagnosis.15 We will make the argument in this article, however, that diagnosis should be defined universally as an abnormal result with the One Step 75-g glucose testing, as adopted by the World Health Organization, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, and others. Approximately 8% of all pregnancies are complicated by GDM by the One Step test in the United States.18-22 The prevalence may range from 1% to 14% of all pregnancies, depending on the population studied and the diagnostic tests employed.1,19

Diagnostic options

Different methods for screening and diagnosis of GDM have been proposed by international societies; there is controversy regarding the diagnosis of GDM by either the One Step or the Two Step approach.6

The One Step approach includes an oral glucose tolerance test with a 75-g glucose load with measurement of plasma glucose concentration at fasting state and 1 hour and 2 hours post–glucose administration. A positive result for the One Step approach is defined as at least 1 measurement higher than 92, 180, or 153 mg/dL at fasting, 1 hour, or 2 hours, respectively.

The Two Step approach includes a nonfasting oral 50-g glucose load, with a glucose blood measurement 1 hour later. A positive screening, defined often as a blood glucose value higher than 135 mg/dL (range, 130 to 140 mg/dL), is followed by a diagnostic test with a 100-g glucose load with measurements at fasting and 1, 2, and 3 hours post–glucose administration. A positive diagnostic test is defined as 2 measurements higher than the target value.

Why we support the One Step test

There are several reasons to prefer the One Step approach for the diagnosis of GDM, compared with the Two Step approach.

Women testing negative for GDM with Two Step still experience complications pregnancy. Women who test positive for GDM with the One Step test, but negative with the Two Step test, despite having therefore a milder degree of glucose intolerance, do have a higher risk of experiencing several complications.23 For the mother, these complications include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery. The baby also can experience problems at birth (TABLE 2).23 Therefore, women who test positive for GDM with the One Step test deserve to be diagnosed with and treated for the condition, as not only are they at risk for these complications but also treatment of the GDM decreases the incidence of these complications.18,19

There is indeed an increased GDM diagnosis rate with the One Step (about 8%) compared with the Two Step test (about 4%). Nonetheless, this increase is mild and nonsignificant in the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs),18,19 is less than the 18% difference in diagnosis rate previously hypothesized, is consistent with the increased diabetes/prediabetes rates in the general population, and is linked to the increasing incidence of obesity and insulin resistance.

Overall test adherence is better. Five percent to 15% of patients, depending on the study, are not adherent with taking the second part of the Two Step test. Women indeed prefer the One Step approach; the second step in the Two Step approach may be a burden.

Less costly. The One Step process is cost-effective when postpregnancy diabetes mellitus prevention is considered.

Better maternal and perinatal outcomes. Probably the most important and convincing reason the One Step test should be used is that meta-analysis of the 4 RCTs comparing the approaches (including 2 US trials) shows that diagnosing and treating mild GDM as per the One Step approach, compared with screening and treating using the Two Step approach, is associated with increased incidence of GDM (8% vs 4%) and with better maternal and perinatal outcomes.13,18,19 In fact, the One Step approach is associated with significant reductions in: large for gestational age (56%), admission to neonatal intensive care unit (51%), and neonatal hypoglycemia (48%). Tests of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis and of quality all pointed to better outcomes in the One Step test group.13,19

The need for a second step in the Two Step approach delays diagnosis and treatment. The One Step approach is associated with an increase in GDM test adherence and earlier diagnosis,13 which is another reason for better outcomes with the One Step approach. In the presence of risk factors, such as prior GDM, prior macrosomia, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, and others, the One Step test should be done at the first prenatal visit.

Continue to: US guidelines should be reconsidered...

US guidelines should be reconsidered

The One Step, 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test is universally used to diagnose diabetes mellitus outside of pregnancy. Given our many noted reasons (TABLE 3), we recommend universal screening of GDM by using the One Step approach. It is time, indeed, for the United States to reconsider its guidelines for screening for GDM.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) generally is defined as any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy.1-14 The best approach and exact criteria to use for GDM screening and diagnosis are under worldwide debate. In TABLE 1 we present just some of the many differing suggestions by varying organizations.2,7-9,11,12,15-17 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for instance, suggests a Two Step approach to diagnosis.15 We will make the argument in this article, however, that diagnosis should be defined universally as an abnormal result with the One Step 75-g glucose testing, as adopted by the World Health Organization, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, and others. Approximately 8% of all pregnancies are complicated by GDM by the One Step test in the United States.18-22 The prevalence may range from 1% to 14% of all pregnancies, depending on the population studied and the diagnostic tests employed.1,19

Diagnostic options

Different methods for screening and diagnosis of GDM have been proposed by international societies; there is controversy regarding the diagnosis of GDM by either the One Step or the Two Step approach.6

The One Step approach includes an oral glucose tolerance test with a 75-g glucose load with measurement of plasma glucose concentration at fasting state and 1 hour and 2 hours post–glucose administration. A positive result for the One Step approach is defined as at least 1 measurement higher than 92, 180, or 153 mg/dL at fasting, 1 hour, or 2 hours, respectively.

The Two Step approach includes a nonfasting oral 50-g glucose load, with a glucose blood measurement 1 hour later. A positive screening, defined often as a blood glucose value higher than 135 mg/dL (range, 130 to 140 mg/dL), is followed by a diagnostic test with a 100-g glucose load with measurements at fasting and 1, 2, and 3 hours post–glucose administration. A positive diagnostic test is defined as 2 measurements higher than the target value.

Why we support the One Step test

There are several reasons to prefer the One Step approach for the diagnosis of GDM, compared with the Two Step approach.

Women testing negative for GDM with Two Step still experience complications pregnancy. Women who test positive for GDM with the One Step test, but negative with the Two Step test, despite having therefore a milder degree of glucose intolerance, do have a higher risk of experiencing several complications.23 For the mother, these complications include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery. The baby also can experience problems at birth (TABLE 2).23 Therefore, women who test positive for GDM with the One Step test deserve to be diagnosed with and treated for the condition, as not only are they at risk for these complications but also treatment of the GDM decreases the incidence of these complications.18,19

There is indeed an increased GDM diagnosis rate with the One Step (about 8%) compared with the Two Step test (about 4%). Nonetheless, this increase is mild and nonsignificant in the meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs),18,19 is less than the 18% difference in diagnosis rate previously hypothesized, is consistent with the increased diabetes/prediabetes rates in the general population, and is linked to the increasing incidence of obesity and insulin resistance.

Overall test adherence is better. Five percent to 15% of patients, depending on the study, are not adherent with taking the second part of the Two Step test. Women indeed prefer the One Step approach; the second step in the Two Step approach may be a burden.

Less costly. The One Step process is cost-effective when postpregnancy diabetes mellitus prevention is considered.

Better maternal and perinatal outcomes. Probably the most important and convincing reason the One Step test should be used is that meta-analysis of the 4 RCTs comparing the approaches (including 2 US trials) shows that diagnosing and treating mild GDM as per the One Step approach, compared with screening and treating using the Two Step approach, is associated with increased incidence of GDM (8% vs 4%) and with better maternal and perinatal outcomes.13,18,19 In fact, the One Step approach is associated with significant reductions in: large for gestational age (56%), admission to neonatal intensive care unit (51%), and neonatal hypoglycemia (48%). Tests of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis and of quality all pointed to better outcomes in the One Step test group.13,19

The need for a second step in the Two Step approach delays diagnosis and treatment. The One Step approach is associated with an increase in GDM test adherence and earlier diagnosis,13 which is another reason for better outcomes with the One Step approach. In the presence of risk factors, such as prior GDM, prior macrosomia, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, and others, the One Step test should be done at the first prenatal visit.

Continue to: US guidelines should be reconsidered...

US guidelines should be reconsidered

The One Step, 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test is universally used to diagnose diabetes mellitus outside of pregnancy. Given our many noted reasons (TABLE 3), we recommend universal screening of GDM by using the One Step approach. It is time, indeed, for the United States to reconsider its guidelines for screening for GDM.

- Kampmann U, Madsen LR, Skajaa GO, et al. Gestational diabetes: a clinical update. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1065-1072.

- HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991-2002.

- Meltzer SJ, Snyder J, Penrod JR, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus screening and diagnosis: a prospective randomised controlled trial comparing costs of one-step and two-step methods. BJOG. 2010;117:407-415.

- Sevket O, Ates S, Uysal O, et al. To evaluate the prevalence and clinical outcomes using a one-step method versus a two-step method to screen gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:36-41.

- Scifres CM, Abebe KZ, Jones KA, et al. Gestational diabetes diagnostic methods (GD2M) pilot randomized trial. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1472-1480.

- Farrar D, Duley L, Medley N, et al. Different strategies for diagnosing gestational diabetes to improve maternal and infant health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD007122.

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S11-S24.

- Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes and Pregnancy. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(suppl 1):S168-S183.

- NICE guideline. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period. February 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3/. Last updated August 2015. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- WHO 1999. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. From http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66040/1/WHO

_NCD_NCS_99.2.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019. - World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85975/1/WHO_

NMH_MND_13.2_eng.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019. - Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(suppl 3):S173-S211.

- Berghella V, Caissutti C, Saccone G, et al. The One Step approach for diagnosing gestational diabetes is associated with better perinatal outcomes than using the Two Step approach: evidence of randomized clinical trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:562-564.

- Berghella V, Caissutti C, Saccone G, et al. One-Step approach to identifying gestational diabetes mellitus: association with perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:383.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 180: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e17-e31.

- Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:768-773.

- National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039-1057.

- Saccone G, Khalifeh A, Al-Kouatly HB, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: one step versus two step approach. A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-9.

- Saccone G, Caissutti C, Khalifeh A, et al. One step versus two step approach for gestational diabetes screening: systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1547-1555.

- Khalifeh A, Eckler R, Felder L, et al. One-step versus two-step diagnostic testing for gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-6.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Khalifeh A, et al. Which criteria should be used for starting pharmacologic therapy for management of gestational diabetes in pregnancy? Evidence from randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:2905-2914.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Ciardulli A, et al. Very tight vs. tight control: which should be the criteria for pharmacologic therapy dose adjustment in diabetes in pregnancy? Evidence from randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:235-247.

- Caissutti C, Khalifeh A, Saccone G, et al. Are women positive for the One Step but negative for the Two Step screening tests for gestational diabetes at higher risk for adverse outcomes? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:122-134.

- Kampmann U, Madsen LR, Skajaa GO, et al. Gestational diabetes: a clinical update. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:1065-1072.

- HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1991-2002.

- Meltzer SJ, Snyder J, Penrod JR, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus screening and diagnosis: a prospective randomised controlled trial comparing costs of one-step and two-step methods. BJOG. 2010;117:407-415.

- Sevket O, Ates S, Uysal O, et al. To evaluate the prevalence and clinical outcomes using a one-step method versus a two-step method to screen gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:36-41.

- Scifres CM, Abebe KZ, Jones KA, et al. Gestational diabetes diagnostic methods (GD2M) pilot randomized trial. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1472-1480.

- Farrar D, Duley L, Medley N, et al. Different strategies for diagnosing gestational diabetes to improve maternal and infant health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD007122.

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S11-S24.

- Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes and Pregnancy. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(suppl 1):S168-S183.

- NICE guideline. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period. February 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3/. Last updated August 2015. Accessed November 18, 2019.

- WHO 1999. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. From http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66040/1/WHO

_NCD_NCS_99.2.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019. - World Health Organization. Diagnostic criteria and classification of hyperglycaemia first detected in pregnancy. 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85975/1/WHO_

NMH_MND_13.2_eng.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2019. - Hod M, Kapur A, Sacks DA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Initiative on gestational diabetes mellitus: a pragmatic guide for diagnosis, management, and care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;131(suppl 3):S173-S211.

- Berghella V, Caissutti C, Saccone G, et al. The One Step approach for diagnosing gestational diabetes is associated with better perinatal outcomes than using the Two Step approach: evidence of randomized clinical trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:562-564.

- Berghella V, Caissutti C, Saccone G, et al. One-Step approach to identifying gestational diabetes mellitus: association with perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:383.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 180: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e17-e31.

- Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:768-773.

- National Diabetes Data Group. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28:1039-1057.

- Saccone G, Khalifeh A, Al-Kouatly HB, et al. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: one step versus two step approach. A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-9.

- Saccone G, Caissutti C, Khalifeh A, et al. One step versus two step approach for gestational diabetes screening: systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1547-1555.

- Khalifeh A, Eckler R, Felder L, et al. One-step versus two-step diagnostic testing for gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018:1-6.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Khalifeh A, et al. Which criteria should be used for starting pharmacologic therapy for management of gestational diabetes in pregnancy? Evidence from randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:2905-2914.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Ciardulli A, et al. Very tight vs. tight control: which should be the criteria for pharmacologic therapy dose adjustment in diabetes in pregnancy? Evidence from randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:235-247.

- Caissutti C, Khalifeh A, Saccone G, et al. Are women positive for the One Step but negative for the Two Step screening tests for gestational diabetes at higher risk for adverse outcomes? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:122-134.

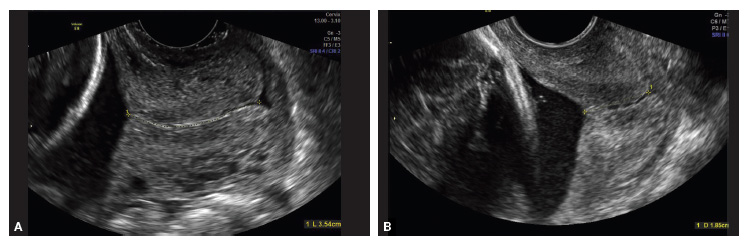

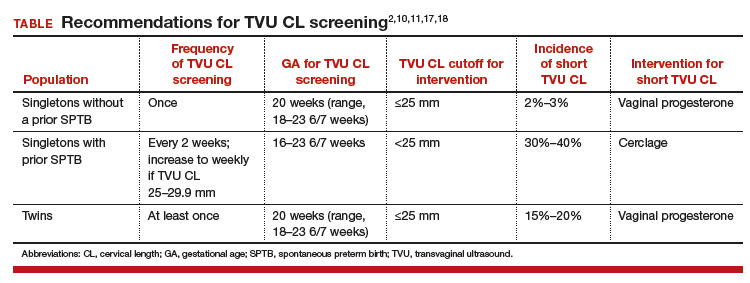

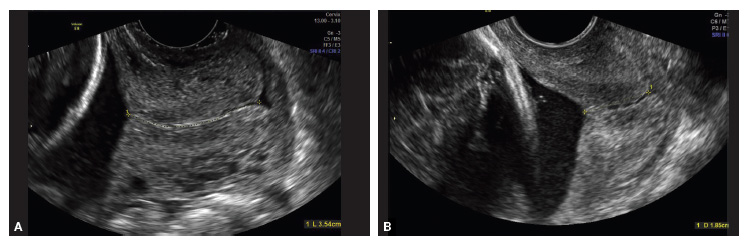

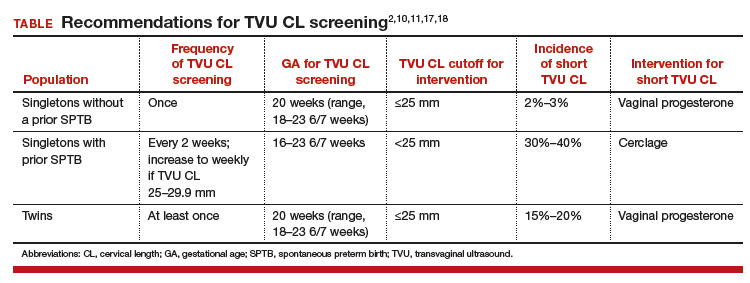

Universal cervical length screening–saving babies lives

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

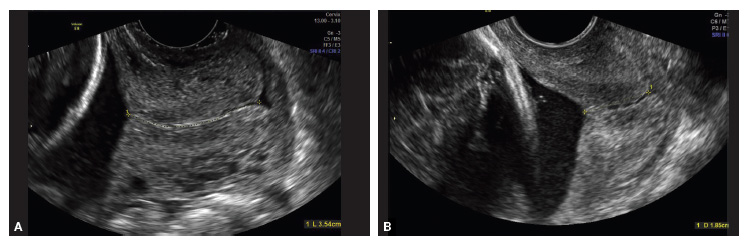

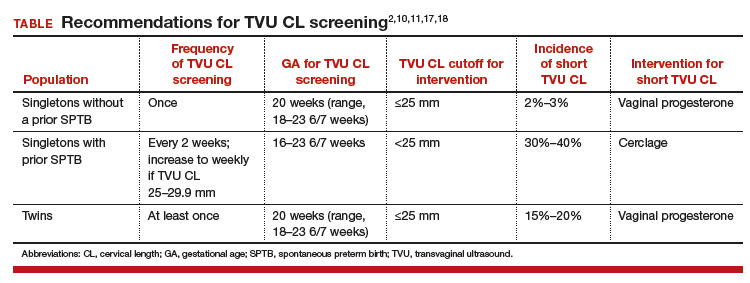

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) cervical length (CL) screening for prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) is among the most transformative clinical changes in obstetrics in the last decades. TVU CL screening should now be offered to all pregnant women: hence the appellative ‘universal CL screening.’

TVU CL screening is an excellent screening test for several reasons. It screens for SPTB, which is a clinically important, well-defined disease whose prevalence and natural history is known, and has an early recognizable asymptomatic phase in CL shortening detected by TVU. TVU CL screening is a well-described technique, safe and acceptable, with a reasonable cutoff (25 mm) now identified for all populations, and results are reproducible and accurate. There are hundreds of studies proving these facts. In the last 10 years, TVU measurement of CL as a screening test has been accepted1,2: it identifies women at risk for SPTB, and an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation) is effective in preventing SPTB. Screening and treatment of short cervix is cost-effective and readily available as an early intervention (progesterone or cerclage depending on the clinical situation), is effective in preventing the outcome (SPTB), treating abnormal results is cost-effective, and facilities for screening are available and treatments are readily available.3–5 It is also important to emphasize that CL screening for prevention of SPTB should be done by TVU, and not by transabdominal ultrasound.6It is best to review TVU CL screening by populations: singletons without prior SPTB, singletons with prior SPTB, and twins (Table).

Related Article:

Can transabdominal ultrasound exclude short cervix?

Singletons without prior SPTB

Women with no previous SPTB who are carrying a singleton pregnancy is the population in which TVU CL could have the greatest impact on decreasing SPTB, for several reasons:

- Up to 60% to 90% of SPTB occur in this population.

- More than 90% of these women have risk factors for SPTB.7,8

- Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant 39% decrease in PTB at <33 weeks of gestation and a significant 38% decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 606 women without prior PTB.9,10

- Cost-effectiveness studies have shown that TVU CL screening in this specific population prevents thousands of preterm births, saves or improves from death or major morbidity 350 babies’ lives annually, and saves approximately $320,000 per year in the US alone.3 These numbers may be even higher now as the TVU CL cutoff for offering vaginal progesterone has moved in many centers from ≤20 mm to ≤25 mm, including more women (from about 0.8% to about 2% to 3%, respectively11) who benefit from screening.

- Real-world implementation studies have indeed shown significant decreases in SPTB when a policy of universal TVU CL screening in this specific population is implemented.12,13

Universal TVU CL screening recently called into question

In a recent article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association,14 TVU CL screening in this population, in particular for nulliparous women, has come under interrogation. The authors found only an 8% sensitivity of TVU CL screening for SPTB using a cutoff of ≤25 mm at 16 0/7 to 22 6/7 weeks of gestation in 9,410 nulliparous women. This result is different compared with other previous cohort studies in this area, however, and is likely related to a number of issues in the methodology.

First, TVU CL screening was done in many women at too early a gestational age. The earlier the CL screening, the lower the sensitivity of the procedure. Data at 16 and 17 weeks of gestation should have been excluded, as almost all RCTs and other studies on universal TVU CL screening in this population recommended doing screening at about 18 0/7 to 23 6/7 weeks.

Second, women with TVU CL <15 mm received vaginal progesterone. This would decrease the incidence of PTB and, therefore, sensitivity.

Third, outcomes data were not available for 469 women and, compared with women analyzed, these women were at higher risk for SPTB as they were more likely to be aged 21 years or younger, black, with less than a high school education, and single, all significant risk factors for SPTB. (Not all risk factors for SPTB were reported in this study.)

Fourth, pregnancy losses before 20 weeks were excluded, and these could have been early SPTB; therefore, the sensitivity could have been decreased if women with this outcome were excluded.

Fifth, prior studies have shown that TVU CL screening in singletons without prior SPTB has a sensitivity of about 30% to 40%.15,16 In nulliparas, the sensitivity of TVU CL ≤20 mm had been reported previously to be 20%.16 Additional data from 2012–2014 at our institution demonstrate that the incidence of CL ≤25 mm is about 2.8% in nulliparous women, with a sensitivity of 19.5% for SPTB <37 weeks. These numbers show again that 8% sensitivity was low in the JAMA study14 due the shortcomings we just highlighted. Furthermore, the reported sensitivity of TVU CL ≤25 mm for PTB <32 weeks was 24% in Esplin and colleagues’ study,14 while 60% in our data. Given that early preterm births are the most significant source of neonatal morbidity and mortality, women with a singleton gestation and no prior SPTB but with a short TVU CL are perhaps the most important subgroup to identify.

Sixth, a low sensitivity in and of itself is not reflective of a poor screening test. We have known for a long time that SPTB has many etiologies. No one screening test, and no one intervention, would independently prevent all SPTBs. In a population that accounts for more than half of PTBs and for whom no other screening test has been found to be effective, much less cost effective, it is important not to cast aside the dramatic potential clinical benefit to TVU CL screening.

Related Article:

A stepwise approach to cervical cerclage

Singletons with a prior SPTB

This is the first population in which TVU CL screening was first proven beneficial for prevention of SPTB. These women all should receive progesterone starting at 16 weeks because of the prior SPTB. In these women, TVU CL screening should be initiated at 16 weeks, and repeated every 2 weeks (weekly if TVU CL is found to be 25 mm to 29 mm) until 23 6/7 weeks. If the TVU CL is identified to be <25 mm before 24 weeks, cerclage should be recommended.1,2,17

Twins

Twins are the most recent population in which an intervention based on TVU CL screening has been shown to be beneficial. Vaginal progesterone has been associated with a significant decrease in SPTB as well as in some neonatal outcomes in twin gestations found to have a TVU CL <25 mm in the midtrimester in a meta-analysis of RCTs.18 Based on these results, we at our institution recently have started offering TVU CL screening at the time of the anatomy scan (about 20 weeks) to twin gestations.

Related Article:

Which perioperative strategies for transvaginal cervical cerclage are backed by data?

Bottom line

In summary, universal second trimester TVU CL screening of both singletons and twin gestations should be considered seriously by obstetric practitioners to successfully decrease the grave burden of SPTB.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins--Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 130: Prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964-973.

- Werner EF, Hamel MS, Orzechowski K, Berghella V, Thung SF. Cost-effectiveness of transvaginal ultrasound cervical length screening in singletons without a prior preterm birth: an update. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4):554.e1-e6.

- Einerson BD, Grobman WA, Miller ES. Cost-effectiveness of risk-based screening for cervical length to prevent preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):100.e1-e7.

- McIntosh J, Feltovich H, Berghella V, Manuck T; Society for Maternal-Fetal medicine. The role of routine cervical length screening in selected high- and low-risk women for preterm birth prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):B2-B7.

- Khalifeh A, Quist-Nelson J. Current implementation of universal cervical length screening for preterm birth prevention in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(suppl 1):7S.

- Mella MT, Mackeen AD, Gache D, Baxter JK, Berghella V. The utility of screening for historical risk factors for preterm birth in women with known second trimester cervical length. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26(7):710-715.

- Saccone G, Perriera L, Berghella V. Prior uterine evacuation of pregnancy as independent risk factor for preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):572-591.

- Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: A systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):124.e1-e19.

- Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):308-317.

- Orzechoski KM, Boelig RC, Baxter JK, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520-525.

- Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):365.e1-e5.

- Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, et al. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(4):523.e1-e8.

- Esplin MS, Elovitz MA, Iams JD, et al; njMoM2b Network. Predictive accuracy of serial ttransvaginal cervical lengths and quantitative vaginal fetal fibronectin levels for spontaneous preterm birth among nulliparous women. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1047-1056.

- Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):567-572.

- Orzechowski KM, Boelig R, Nicholas SS, Baxter J, Berghella V. Is universal cervical length screening indicated in women with prior term birth? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):234.e1-e5.

- Preterm labour and birth. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25?unlid=9291036072016213201257. Published November 2015. Accessed May 18, 2017.

- Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, El-Refaie W, et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth and neonatal morbidity and mortality in women with a twin gestation and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis of individual patient data. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(3):303-314.

- Berghella V. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: Translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376-386.