User login

Role of Speech Pathology in a Multidisciplinary Approach to a Patient With Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Speech-language pathologists can fill a unique need in the treatment of patients with several conditions that are seen regularly in primary care.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are integral to the comprehensive treatment of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), yet the evaluation and treatment options they offer may not be known to all primary care providers (PCPs). As the research on the management and treatment of mTBI continues to evolve, the PCPs role in referring patients with mTBI to the appropriate resources becomes imperative.

mTBI is a common injury in both military and civilian settings, but it can be difficult to diagnose and is not always well understood. Long-term debilitating effects have been associated with mTBI, with literature linking it to an increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson disease.1 In addition, mTBI is a strong predictor for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Among returning Iraq and Afghanistan service members, the incidence of mTBI associated mental health conditions have been reported to be as high as 22.8%, affecting > 320,000 veterans.2-5

The US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) health care system offers these returning veterans a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment strategy. The care is often coordinated by the veteran’s patient aligned care team (PACT) that consists of a PCP, nurses, and a medical support associate. The US Department of Defense (DoD) and VA also facilitated the development of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) that can be used by the PACT and other health care providers to support evidence based patient-centered care. This CPG is extensive and has recommendations for evaluation and treatment of mTBI and the symptoms associated such as impaired memory and alterations in executive function.6

The following hypothetical case is based on an actual patient. This case illustrates the role of speech pathology in caring for patients with mTBI.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old male combat veteran presented to his VA PACT team for a new patient visit. As part of the screening of his medical history, mTBI was fully defined for the patient to include “alteration” in consciousness. This reminded the patient of an injury that occurred 1 year prior to presentation during a routine convoy mission. He was riding in the back of a Humvee when it hit a large pothole slamming his head into the side of the vehicle. He reported that he felt “dazed and dizzy” with “ringing” in his ears immediately following the event, without an overt loss of consciousness. He was unable to seek medical attention secondary to the urgency of the convoy mission, so he “shook it off” and kept going. Later that week he noted headache and insomnia. He was seen and evaluated by his health care provider for insomnia, but when questioned he reported no head trauma as he had forgotten the incident. Upon follow-up with his PCP, he reported his headaches were manageable, and his insomnia was somewhat improved with recommended life-style modifications and good sleep hygiene.

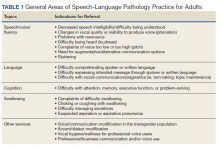

He still had frequent headaches, dizziness, and some insomnia. However, his chief concern was that he was struggling with new schoolwork. He noted that he was a straight-A student prior to his military service. A review of his medical history in his medical chart showed that a previous PCP had treated his associated symptoms of insomnia and headache without improvement. In addition, he had recently been diagnosed with PTSD. As his symptoms had lasted > 90 days, not resolved with initial treatment in primary care, and were causing a significant impact on his activities of daily living, his PCP placed a consult to Speech Pathology for cognitive-linguistic assessment and treatment, if indicated, noting that he may have had a mTBI.6 Although not intended to be comprehensive, Table 1 describes several clinical areas where a speech pathology referral may be appropriate.

The Role of the Speech-Language Pathologist

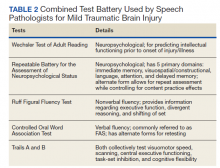

The speech-language pathologist takes an additional history of the patient. This better quantifies specific details of the veteran’s functional concerns pertaining to possible difficulty with attention, memory, executive function, visuospatial awareness, etc. Examples might include difficulty with attention/memory, including not remembering what to get at the store, forgetting to take medications, forgetting appointments, and difficulty in school, among many others. Reports of feeling “stupid” also are common. Assessment varies by clinician, but it is not uncommon for the SLP to administer a battery of evaluations to help identify a range of possible impairments. Choosing testing that is sensitive to even mild impairment is important and should be used in combination with subjective complaints. Mild deficits can sometimes be missed in those with average performance, but whose premorbid intelligence was above average. One combination of test batteries sometimes utilized is the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR), the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), the Ruff Figural Fluency Test (RFFT), the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT), and Trails A and B (Table 2).

The initial testing results are discussed with the veteran. If patient concerns and/or testing reveal impairment that is amenable to treatment and the veteran wishes to proceed, subsequent treatment sessions are scheduled. The first treatment session is spent establishing and prioritizing functional goals specific to that individual and their needs (eg, for daily life, work, school). In a case of subacute or older mTBI, as is often seen in veterans coming to the VA, intervention often targets strategies and techniques that can help the individual compensate for current deficits.

Many patients already own a smartphone, so this device often is used functionally as a cognitive prosthetic as early as the first treatment session. In an effort to immediately start addressing important issues like medication management and attending appointments, the veteran is educated to the benefit of entering important information into the calendar and/or reminder apps on their phone and setting associated alarms that would serve as a reminder for what was entered. Patients are often encouraged by the positive impact of these initial strategies and look forward to future treatment sessions to address compensation for their functional deficits.

If a veteran with TBI has numerous needs, it can be beneficial for the care team to discuss the care plan at an interdisciplinary team meeting. It is not uncommon for veterans like the one discussed above to be referred to neurology (persistent headaches and further neurological evaluation); mental health (PTSD treatment and family support/counseling options); occupational therapy (visuospatial needs); and audiology (vestibular concerns). Social work involvement is often extremely beneficial for coordination of care in more complex cases. If patient is having difficulty making healthy eating choices or with meal preparation, a consult to a dietitian may prove invaluable. Concerns related to trouble with medication adherence (beyond memory-related adherence issues that speech pathology would address) or polypharmacy can be directed to a clinical pharmacy specialist, who could prepare a medication chart, review optimal medication timing, and provide education on adverse effects. A veteran's communication with the team can be facilitated through secure messaging (a method of secure emailing) and encouraging use of the My HealtheVet portal. With this modality, patients could review chart notes and results and share them with non-VA health care providers and/or family members as indicated.

A whole health approach also may appeal to some mTBI patients. This approach focuses on the totality of patient needs for healthy living and on patient-centered goal setting. Services provided may differ at various VA medical centers, but the PACT team can connect the veteran to the services of interest.

Conclusions

A team approach to veterans with mTBI provides a comprehensive way to treat the various problems associated with the condition. Further research into the role of multidisciplinary teams in the management of mTBI was recommended in the 2016 CPG.6 The unique role that the speech-language pathologist plays as part of this team has been highlighted, as it is important that PCP’s be aware of the extent of evaluation and treatment services they offer. Beyond mTBI, speech pathologists evaluate and treat patients with several conditions that are seen regularly in primary care.

1. McKee AC, Robinson ME. Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3 suppl):S242-S253. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.003

2. Yurgil KA, Barkauskas DA, Vasterling JJ, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in active-duty Marines. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):149-157. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3080

3. Chin DL, Zeber JE. Mental Health Outcomes Among Military Service Members After Severe Injury in Combat and TBI. Mil Med. 2020;185(5-6):e711-e718. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz440

4. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023-1032. doi:10.1001/jama.295.9.1023

5. Miles SR, Harik JM, Hundt NE, et al. Delivery of mental health treatment to combat veterans with psychiatric diagnoses and TBI histories. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184265. Published 2017 Sep 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184265

6. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs; Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. Version 2.0. Published February 2016. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/mTBICPGFullCPG50821816.pdf

Speech-language pathologists can fill a unique need in the treatment of patients with several conditions that are seen regularly in primary care.

Speech-language pathologists can fill a unique need in the treatment of patients with several conditions that are seen regularly in primary care.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are integral to the comprehensive treatment of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), yet the evaluation and treatment options they offer may not be known to all primary care providers (PCPs). As the research on the management and treatment of mTBI continues to evolve, the PCPs role in referring patients with mTBI to the appropriate resources becomes imperative.

mTBI is a common injury in both military and civilian settings, but it can be difficult to diagnose and is not always well understood. Long-term debilitating effects have been associated with mTBI, with literature linking it to an increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson disease.1 In addition, mTBI is a strong predictor for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Among returning Iraq and Afghanistan service members, the incidence of mTBI associated mental health conditions have been reported to be as high as 22.8%, affecting > 320,000 veterans.2-5

The US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) health care system offers these returning veterans a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment strategy. The care is often coordinated by the veteran’s patient aligned care team (PACT) that consists of a PCP, nurses, and a medical support associate. The US Department of Defense (DoD) and VA also facilitated the development of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) that can be used by the PACT and other health care providers to support evidence based patient-centered care. This CPG is extensive and has recommendations for evaluation and treatment of mTBI and the symptoms associated such as impaired memory and alterations in executive function.6

The following hypothetical case is based on an actual patient. This case illustrates the role of speech pathology in caring for patients with mTBI.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old male combat veteran presented to his VA PACT team for a new patient visit. As part of the screening of his medical history, mTBI was fully defined for the patient to include “alteration” in consciousness. This reminded the patient of an injury that occurred 1 year prior to presentation during a routine convoy mission. He was riding in the back of a Humvee when it hit a large pothole slamming his head into the side of the vehicle. He reported that he felt “dazed and dizzy” with “ringing” in his ears immediately following the event, without an overt loss of consciousness. He was unable to seek medical attention secondary to the urgency of the convoy mission, so he “shook it off” and kept going. Later that week he noted headache and insomnia. He was seen and evaluated by his health care provider for insomnia, but when questioned he reported no head trauma as he had forgotten the incident. Upon follow-up with his PCP, he reported his headaches were manageable, and his insomnia was somewhat improved with recommended life-style modifications and good sleep hygiene.

He still had frequent headaches, dizziness, and some insomnia. However, his chief concern was that he was struggling with new schoolwork. He noted that he was a straight-A student prior to his military service. A review of his medical history in his medical chart showed that a previous PCP had treated his associated symptoms of insomnia and headache without improvement. In addition, he had recently been diagnosed with PTSD. As his symptoms had lasted > 90 days, not resolved with initial treatment in primary care, and were causing a significant impact on his activities of daily living, his PCP placed a consult to Speech Pathology for cognitive-linguistic assessment and treatment, if indicated, noting that he may have had a mTBI.6 Although not intended to be comprehensive, Table 1 describes several clinical areas where a speech pathology referral may be appropriate.

The Role of the Speech-Language Pathologist

The speech-language pathologist takes an additional history of the patient. This better quantifies specific details of the veteran’s functional concerns pertaining to possible difficulty with attention, memory, executive function, visuospatial awareness, etc. Examples might include difficulty with attention/memory, including not remembering what to get at the store, forgetting to take medications, forgetting appointments, and difficulty in school, among many others. Reports of feeling “stupid” also are common. Assessment varies by clinician, but it is not uncommon for the SLP to administer a battery of evaluations to help identify a range of possible impairments. Choosing testing that is sensitive to even mild impairment is important and should be used in combination with subjective complaints. Mild deficits can sometimes be missed in those with average performance, but whose premorbid intelligence was above average. One combination of test batteries sometimes utilized is the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR), the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), the Ruff Figural Fluency Test (RFFT), the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT), and Trails A and B (Table 2).

The initial testing results are discussed with the veteran. If patient concerns and/or testing reveal impairment that is amenable to treatment and the veteran wishes to proceed, subsequent treatment sessions are scheduled. The first treatment session is spent establishing and prioritizing functional goals specific to that individual and their needs (eg, for daily life, work, school). In a case of subacute or older mTBI, as is often seen in veterans coming to the VA, intervention often targets strategies and techniques that can help the individual compensate for current deficits.

Many patients already own a smartphone, so this device often is used functionally as a cognitive prosthetic as early as the first treatment session. In an effort to immediately start addressing important issues like medication management and attending appointments, the veteran is educated to the benefit of entering important information into the calendar and/or reminder apps on their phone and setting associated alarms that would serve as a reminder for what was entered. Patients are often encouraged by the positive impact of these initial strategies and look forward to future treatment sessions to address compensation for their functional deficits.

If a veteran with TBI has numerous needs, it can be beneficial for the care team to discuss the care plan at an interdisciplinary team meeting. It is not uncommon for veterans like the one discussed above to be referred to neurology (persistent headaches and further neurological evaluation); mental health (PTSD treatment and family support/counseling options); occupational therapy (visuospatial needs); and audiology (vestibular concerns). Social work involvement is often extremely beneficial for coordination of care in more complex cases. If patient is having difficulty making healthy eating choices or with meal preparation, a consult to a dietitian may prove invaluable. Concerns related to trouble with medication adherence (beyond memory-related adherence issues that speech pathology would address) or polypharmacy can be directed to a clinical pharmacy specialist, who could prepare a medication chart, review optimal medication timing, and provide education on adverse effects. A veteran's communication with the team can be facilitated through secure messaging (a method of secure emailing) and encouraging use of the My HealtheVet portal. With this modality, patients could review chart notes and results and share them with non-VA health care providers and/or family members as indicated.

A whole health approach also may appeal to some mTBI patients. This approach focuses on the totality of patient needs for healthy living and on patient-centered goal setting. Services provided may differ at various VA medical centers, but the PACT team can connect the veteran to the services of interest.

Conclusions

A team approach to veterans with mTBI provides a comprehensive way to treat the various problems associated with the condition. Further research into the role of multidisciplinary teams in the management of mTBI was recommended in the 2016 CPG.6 The unique role that the speech-language pathologist plays as part of this team has been highlighted, as it is important that PCP’s be aware of the extent of evaluation and treatment services they offer. Beyond mTBI, speech pathologists evaluate and treat patients with several conditions that are seen regularly in primary care.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are integral to the comprehensive treatment of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), yet the evaluation and treatment options they offer may not be known to all primary care providers (PCPs). As the research on the management and treatment of mTBI continues to evolve, the PCPs role in referring patients with mTBI to the appropriate resources becomes imperative.

mTBI is a common injury in both military and civilian settings, but it can be difficult to diagnose and is not always well understood. Long-term debilitating effects have been associated with mTBI, with literature linking it to an increased risk of developing Alzheimer disease, motor neuron disease, and Parkinson disease.1 In addition, mTBI is a strong predictor for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Among returning Iraq and Afghanistan service members, the incidence of mTBI associated mental health conditions have been reported to be as high as 22.8%, affecting > 320,000 veterans.2-5

The US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) health care system offers these returning veterans a comprehensive, multidisciplinary treatment strategy. The care is often coordinated by the veteran’s patient aligned care team (PACT) that consists of a PCP, nurses, and a medical support associate. The US Department of Defense (DoD) and VA also facilitated the development of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) that can be used by the PACT and other health care providers to support evidence based patient-centered care. This CPG is extensive and has recommendations for evaluation and treatment of mTBI and the symptoms associated such as impaired memory and alterations in executive function.6

The following hypothetical case is based on an actual patient. This case illustrates the role of speech pathology in caring for patients with mTBI.

Case Presentation

A 25-year-old male combat veteran presented to his VA PACT team for a new patient visit. As part of the screening of his medical history, mTBI was fully defined for the patient to include “alteration” in consciousness. This reminded the patient of an injury that occurred 1 year prior to presentation during a routine convoy mission. He was riding in the back of a Humvee when it hit a large pothole slamming his head into the side of the vehicle. He reported that he felt “dazed and dizzy” with “ringing” in his ears immediately following the event, without an overt loss of consciousness. He was unable to seek medical attention secondary to the urgency of the convoy mission, so he “shook it off” and kept going. Later that week he noted headache and insomnia. He was seen and evaluated by his health care provider for insomnia, but when questioned he reported no head trauma as he had forgotten the incident. Upon follow-up with his PCP, he reported his headaches were manageable, and his insomnia was somewhat improved with recommended life-style modifications and good sleep hygiene.

He still had frequent headaches, dizziness, and some insomnia. However, his chief concern was that he was struggling with new schoolwork. He noted that he was a straight-A student prior to his military service. A review of his medical history in his medical chart showed that a previous PCP had treated his associated symptoms of insomnia and headache without improvement. In addition, he had recently been diagnosed with PTSD. As his symptoms had lasted > 90 days, not resolved with initial treatment in primary care, and were causing a significant impact on his activities of daily living, his PCP placed a consult to Speech Pathology for cognitive-linguistic assessment and treatment, if indicated, noting that he may have had a mTBI.6 Although not intended to be comprehensive, Table 1 describes several clinical areas where a speech pathology referral may be appropriate.

The Role of the Speech-Language Pathologist

The speech-language pathologist takes an additional history of the patient. This better quantifies specific details of the veteran’s functional concerns pertaining to possible difficulty with attention, memory, executive function, visuospatial awareness, etc. Examples might include difficulty with attention/memory, including not remembering what to get at the store, forgetting to take medications, forgetting appointments, and difficulty in school, among many others. Reports of feeling “stupid” also are common. Assessment varies by clinician, but it is not uncommon for the SLP to administer a battery of evaluations to help identify a range of possible impairments. Choosing testing that is sensitive to even mild impairment is important and should be used in combination with subjective complaints. Mild deficits can sometimes be missed in those with average performance, but whose premorbid intelligence was above average. One combination of test batteries sometimes utilized is the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR), the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), the Ruff Figural Fluency Test (RFFT), the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT), and Trails A and B (Table 2).

The initial testing results are discussed with the veteran. If patient concerns and/or testing reveal impairment that is amenable to treatment and the veteran wishes to proceed, subsequent treatment sessions are scheduled. The first treatment session is spent establishing and prioritizing functional goals specific to that individual and their needs (eg, for daily life, work, school). In a case of subacute or older mTBI, as is often seen in veterans coming to the VA, intervention often targets strategies and techniques that can help the individual compensate for current deficits.

Many patients already own a smartphone, so this device often is used functionally as a cognitive prosthetic as early as the first treatment session. In an effort to immediately start addressing important issues like medication management and attending appointments, the veteran is educated to the benefit of entering important information into the calendar and/or reminder apps on their phone and setting associated alarms that would serve as a reminder for what was entered. Patients are often encouraged by the positive impact of these initial strategies and look forward to future treatment sessions to address compensation for their functional deficits.

If a veteran with TBI has numerous needs, it can be beneficial for the care team to discuss the care plan at an interdisciplinary team meeting. It is not uncommon for veterans like the one discussed above to be referred to neurology (persistent headaches and further neurological evaluation); mental health (PTSD treatment and family support/counseling options); occupational therapy (visuospatial needs); and audiology (vestibular concerns). Social work involvement is often extremely beneficial for coordination of care in more complex cases. If patient is having difficulty making healthy eating choices or with meal preparation, a consult to a dietitian may prove invaluable. Concerns related to trouble with medication adherence (beyond memory-related adherence issues that speech pathology would address) or polypharmacy can be directed to a clinical pharmacy specialist, who could prepare a medication chart, review optimal medication timing, and provide education on adverse effects. A veteran's communication with the team can be facilitated through secure messaging (a method of secure emailing) and encouraging use of the My HealtheVet portal. With this modality, patients could review chart notes and results and share them with non-VA health care providers and/or family members as indicated.

A whole health approach also may appeal to some mTBI patients. This approach focuses on the totality of patient needs for healthy living and on patient-centered goal setting. Services provided may differ at various VA medical centers, but the PACT team can connect the veteran to the services of interest.

Conclusions

A team approach to veterans with mTBI provides a comprehensive way to treat the various problems associated with the condition. Further research into the role of multidisciplinary teams in the management of mTBI was recommended in the 2016 CPG.6 The unique role that the speech-language pathologist plays as part of this team has been highlighted, as it is important that PCP’s be aware of the extent of evaluation and treatment services they offer. Beyond mTBI, speech pathologists evaluate and treat patients with several conditions that are seen regularly in primary care.

1. McKee AC, Robinson ME. Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3 suppl):S242-S253. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.003

2. Yurgil KA, Barkauskas DA, Vasterling JJ, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in active-duty Marines. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):149-157. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3080

3. Chin DL, Zeber JE. Mental Health Outcomes Among Military Service Members After Severe Injury in Combat and TBI. Mil Med. 2020;185(5-6):e711-e718. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz440

4. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023-1032. doi:10.1001/jama.295.9.1023

5. Miles SR, Harik JM, Hundt NE, et al. Delivery of mental health treatment to combat veterans with psychiatric diagnoses and TBI histories. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184265. Published 2017 Sep 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184265

6. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs; Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. Version 2.0. Published February 2016. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/mTBICPGFullCPG50821816.pdf

1. McKee AC, Robinson ME. Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3 suppl):S242-S253. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.003

2. Yurgil KA, Barkauskas DA, Vasterling JJ, et al. Association between traumatic brain injury and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder in active-duty Marines. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):149-157. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3080

3. Chin DL, Zeber JE. Mental Health Outcomes Among Military Service Members After Severe Injury in Combat and TBI. Mil Med. 2020;185(5-6):e711-e718. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz440

4. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023-1032. doi:10.1001/jama.295.9.1023

5. Miles SR, Harik JM, Hundt NE, et al. Delivery of mental health treatment to combat veterans with psychiatric diagnoses and TBI histories. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184265. Published 2017 Sep 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0184265

6. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs; Management of Concussion/mTBI Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. Version 2.0. Published February 2016. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/mTBICPGFullCPG50821816.pdf

Why Accept a VA Detail or Short-Term Assignment? Benefits to Employees and the Service

In the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), there are frequent e-mails and requests for employees to accept a detail or short-term assignment across a wide range of positions from administrative to executive leadership. These opportunities afford an employee and the service line valuable benefits and growth opportunities; however, there are reasons why some may be reluctant to pursue these opportunities. In this article, we discuss the barriers to applying for and accepting detail positions and the benefits for the employee and the service lines during periods of standard operations as well as during emergencies requiring alternative staffing strategies.

Details are short-term assignments used to fill a vacant position while hiring for the permanent position or to fill a short-term need (eg, during a pandemic). Details usually last 30 to 120 days, though they may be extended, depending on the position, the number of people willing to serve in the detailed role, and the time to select a candidate for the permanent position. Details can be created for any skill level or type of position to meet an identified need, but they are most often needed for supervisory or leadership roles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the importance of individuals’ flexibility and adaptability both within and between roles. Many US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities stood up Incident Command structures to support the changes required to adapt to the needs created by the pandemic. Establishing an Incident Command means that people within the organization must take on new responsibilities, and in many cases, they are detailed to new positions that were not needed or prioritized before the pandemic.

Barriers

An employee may be reluctant to apply for or accept a detail because he or she has little to no experience; feels uncomfortable stepping into an unfamiliar role; is concerned about making a leap from a clinical to administrative role; has uncertainty whether the job is a good professional fit; dislikes the lack of a pay increase during the detail period even if the new role has more responsibility; and has concern that serving in the detail may make them ineligible to apply for the permanent position due to a perception of being preselected. Additionally, the employee may recognize the added stress on colleagues because the same amount of work must be completed.

Benefits

Although leaving a position for a period of months can be stressful, serving in a detail position provides significant opportunities for professional growth. An employee can gain knowledge and experience in an unfamiliar role before applying for or committing to a permanent position. Those serving in temporary details are often given more support as colleagues and supervisors understand that the role was accepted on short notice with little time to prepare. Other benefits include expanding professional contacts, gaining perspective on a different part of the VHA, and working on skills, such as flexibility, time management, and perseverance. By succeeding in a detail, employees build professional acumen. After taking on additional challenges they become more competitive for future jobs. The VHA Executive Candidate Development Program requires a 120-day detail, serving as either assistant or associate director, chief of staff, or associate director for patient care services/nurse executive as part of the program.1

Temporarily leaving a service line to detail in a different service line has an impact on the home service because of the restrictions imposed. These restrictions guarantee that the employee can return to the original position at the end of a detail, thus providing a sense of job security; however, the home service line is down an employee.

Given these considerations, the following are key points to establish before undertaking the detail: (1) length of assignment; (2) once started, potential for the assignment to be extended; (3) will the employee be doing any of their prior job or just the new job or a blend of both; (4) possible changes in hours and site of work of the employee; (5) who will supervise the employee; (6) who will write the employee’s review; (7) training or skills needed prior to starting; (8) necessary paperwork; (9) how will the new assignment be communicated to others; (10) what happens if the detail ends sooner than planned; and (11) approval and support of all involved parties.

The employee’s home service may need a temporary plan to cover the employee’s workload, especially if the employee will be detailed to a different service line. The temporary plan may require creativity and flexibility and can be a way to trial the contingency plans for staffing the home service. One benefit to the home service is that the employee will have additional skills on returning that may benefit the home service, and the service will gain a potential leader.

When an employee goes to a different service, that service gains an employee who may bring a new perspective to help solve existing conflicts or problems. This can serve as a time to reset expectations or set new goals prior to the arrival of new leadership. If the detail is a good fit, then there is the chance that the employee may return in the future or refer others to it as a professional opportunity.

Conclusions

A detail can benefit the employee and the home and host services if planned in advance, and all parties support the process. A short-term leadership or administrative assignment can help an employee gain valuable experience for the future.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Improve VA’s employee experience.obamaadministration.archives.performance.gov/node/65741.html. Published 2017. Accessed October 19, 2020.

In the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), there are frequent e-mails and requests for employees to accept a detail or short-term assignment across a wide range of positions from administrative to executive leadership. These opportunities afford an employee and the service line valuable benefits and growth opportunities; however, there are reasons why some may be reluctant to pursue these opportunities. In this article, we discuss the barriers to applying for and accepting detail positions and the benefits for the employee and the service lines during periods of standard operations as well as during emergencies requiring alternative staffing strategies.

Details are short-term assignments used to fill a vacant position while hiring for the permanent position or to fill a short-term need (eg, during a pandemic). Details usually last 30 to 120 days, though they may be extended, depending on the position, the number of people willing to serve in the detailed role, and the time to select a candidate for the permanent position. Details can be created for any skill level or type of position to meet an identified need, but they are most often needed for supervisory or leadership roles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the importance of individuals’ flexibility and adaptability both within and between roles. Many US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities stood up Incident Command structures to support the changes required to adapt to the needs created by the pandemic. Establishing an Incident Command means that people within the organization must take on new responsibilities, and in many cases, they are detailed to new positions that were not needed or prioritized before the pandemic.

Barriers

An employee may be reluctant to apply for or accept a detail because he or she has little to no experience; feels uncomfortable stepping into an unfamiliar role; is concerned about making a leap from a clinical to administrative role; has uncertainty whether the job is a good professional fit; dislikes the lack of a pay increase during the detail period even if the new role has more responsibility; and has concern that serving in the detail may make them ineligible to apply for the permanent position due to a perception of being preselected. Additionally, the employee may recognize the added stress on colleagues because the same amount of work must be completed.

Benefits

Although leaving a position for a period of months can be stressful, serving in a detail position provides significant opportunities for professional growth. An employee can gain knowledge and experience in an unfamiliar role before applying for or committing to a permanent position. Those serving in temporary details are often given more support as colleagues and supervisors understand that the role was accepted on short notice with little time to prepare. Other benefits include expanding professional contacts, gaining perspective on a different part of the VHA, and working on skills, such as flexibility, time management, and perseverance. By succeeding in a detail, employees build professional acumen. After taking on additional challenges they become more competitive for future jobs. The VHA Executive Candidate Development Program requires a 120-day detail, serving as either assistant or associate director, chief of staff, or associate director for patient care services/nurse executive as part of the program.1

Temporarily leaving a service line to detail in a different service line has an impact on the home service because of the restrictions imposed. These restrictions guarantee that the employee can return to the original position at the end of a detail, thus providing a sense of job security; however, the home service line is down an employee.

Given these considerations, the following are key points to establish before undertaking the detail: (1) length of assignment; (2) once started, potential for the assignment to be extended; (3) will the employee be doing any of their prior job or just the new job or a blend of both; (4) possible changes in hours and site of work of the employee; (5) who will supervise the employee; (6) who will write the employee’s review; (7) training or skills needed prior to starting; (8) necessary paperwork; (9) how will the new assignment be communicated to others; (10) what happens if the detail ends sooner than planned; and (11) approval and support of all involved parties.

The employee’s home service may need a temporary plan to cover the employee’s workload, especially if the employee will be detailed to a different service line. The temporary plan may require creativity and flexibility and can be a way to trial the contingency plans for staffing the home service. One benefit to the home service is that the employee will have additional skills on returning that may benefit the home service, and the service will gain a potential leader.

When an employee goes to a different service, that service gains an employee who may bring a new perspective to help solve existing conflicts or problems. This can serve as a time to reset expectations or set new goals prior to the arrival of new leadership. If the detail is a good fit, then there is the chance that the employee may return in the future or refer others to it as a professional opportunity.

Conclusions

A detail can benefit the employee and the home and host services if planned in advance, and all parties support the process. A short-term leadership or administrative assignment can help an employee gain valuable experience for the future.

In the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), there are frequent e-mails and requests for employees to accept a detail or short-term assignment across a wide range of positions from administrative to executive leadership. These opportunities afford an employee and the service line valuable benefits and growth opportunities; however, there are reasons why some may be reluctant to pursue these opportunities. In this article, we discuss the barriers to applying for and accepting detail positions and the benefits for the employee and the service lines during periods of standard operations as well as during emergencies requiring alternative staffing strategies.

Details are short-term assignments used to fill a vacant position while hiring for the permanent position or to fill a short-term need (eg, during a pandemic). Details usually last 30 to 120 days, though they may be extended, depending on the position, the number of people willing to serve in the detailed role, and the time to select a candidate for the permanent position. Details can be created for any skill level or type of position to meet an identified need, but they are most often needed for supervisory or leadership roles.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shed light on the importance of individuals’ flexibility and adaptability both within and between roles. Many US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities stood up Incident Command structures to support the changes required to adapt to the needs created by the pandemic. Establishing an Incident Command means that people within the organization must take on new responsibilities, and in many cases, they are detailed to new positions that were not needed or prioritized before the pandemic.

Barriers

An employee may be reluctant to apply for or accept a detail because he or she has little to no experience; feels uncomfortable stepping into an unfamiliar role; is concerned about making a leap from a clinical to administrative role; has uncertainty whether the job is a good professional fit; dislikes the lack of a pay increase during the detail period even if the new role has more responsibility; and has concern that serving in the detail may make them ineligible to apply for the permanent position due to a perception of being preselected. Additionally, the employee may recognize the added stress on colleagues because the same amount of work must be completed.

Benefits

Although leaving a position for a period of months can be stressful, serving in a detail position provides significant opportunities for professional growth. An employee can gain knowledge and experience in an unfamiliar role before applying for or committing to a permanent position. Those serving in temporary details are often given more support as colleagues and supervisors understand that the role was accepted on short notice with little time to prepare. Other benefits include expanding professional contacts, gaining perspective on a different part of the VHA, and working on skills, such as flexibility, time management, and perseverance. By succeeding in a detail, employees build professional acumen. After taking on additional challenges they become more competitive for future jobs. The VHA Executive Candidate Development Program requires a 120-day detail, serving as either assistant or associate director, chief of staff, or associate director for patient care services/nurse executive as part of the program.1

Temporarily leaving a service line to detail in a different service line has an impact on the home service because of the restrictions imposed. These restrictions guarantee that the employee can return to the original position at the end of a detail, thus providing a sense of job security; however, the home service line is down an employee.

Given these considerations, the following are key points to establish before undertaking the detail: (1) length of assignment; (2) once started, potential for the assignment to be extended; (3) will the employee be doing any of their prior job or just the new job or a blend of both; (4) possible changes in hours and site of work of the employee; (5) who will supervise the employee; (6) who will write the employee’s review; (7) training or skills needed prior to starting; (8) necessary paperwork; (9) how will the new assignment be communicated to others; (10) what happens if the detail ends sooner than planned; and (11) approval and support of all involved parties.

The employee’s home service may need a temporary plan to cover the employee’s workload, especially if the employee will be detailed to a different service line. The temporary plan may require creativity and flexibility and can be a way to trial the contingency plans for staffing the home service. One benefit to the home service is that the employee will have additional skills on returning that may benefit the home service, and the service will gain a potential leader.

When an employee goes to a different service, that service gains an employee who may bring a new perspective to help solve existing conflicts or problems. This can serve as a time to reset expectations or set new goals prior to the arrival of new leadership. If the detail is a good fit, then there is the chance that the employee may return in the future or refer others to it as a professional opportunity.

Conclusions

A detail can benefit the employee and the home and host services if planned in advance, and all parties support the process. A short-term leadership or administrative assignment can help an employee gain valuable experience for the future.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Improve VA’s employee experience.obamaadministration.archives.performance.gov/node/65741.html. Published 2017. Accessed October 19, 2020.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Improve VA’s employee experience.obamaadministration.archives.performance.gov/node/65741.html. Published 2017. Accessed October 19, 2020.

Partners in Oncology Care: Coordinated Follicular Lymphoma Management (FULL)

Four case examples illustrate the important role of multidisciplinary medical care for the optimal long-term care of patients with follicular lymphoma.

Patients benefit from multidisciplinary care that coordinates management of complex medical problems. Traditionally, multidisciplinary cancer care involves oncology specialty providers in fields that include medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary cancer care intends to improve patient outcomes by bringing together different health care providers (HCPs) who are involved in the treatment of patients with cancer. Because new therapies are more effective and allow patients with cancer to live longer, adverse effects (AEs) are more likely to impact patients’ well-being, both while receiving treatment and long after it has completed. Thus, this population may benefit from an expanded approach to multidisciplinary care that includes input from specialty and primary care providers (PCPs), clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS), physical and occupational therapists, and patient navigators and educators.

We present 4 hypothetical cases, based on actual patients, that illustrate opportunities where multidisciplinary care coordination may improve patient experiences. These cases draw on current quality initiatives from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, which has focused on improving the quality of multidisciplinary cancer care at selected community centers, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, which brings together different health professionals to optimize primary care coordination.1,2 In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance has introduced an educational initiative to facilitate implementation of an oncologic medical home.3 This initiative stresses increased multidisciplinary communication, patient-centered care delivery, and reduced fragmentation of care for this population. Despite these guidelines and experiences from other medical specialties, models for integrated cancer care have not been implemented in a prospective fashion within the VHA.

In this article, we focus on opportunities to take collaborative care approaches for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL): a common, incurable, and often indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4 FL was selected because these patients may be treated numerous times and long-term sequalae can accumulate throughout their cancer continuum (a series of health events encompassing cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, relapse, and death).5 HCPs in distinct roles can assist patients with cancer in optimizing their health outcomes and overall wellbeing.6

Case Example 1

A 70-year-old male was diagnosed with stage IV FL. Because of his advanced disease, he began therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). Prednisone was administered at 100 mg daily on the first 5 days of each 21-day cycle. On day 4 of the first treatment cycle, the patient notified his oncologist that he had been very thirsty and his random blood sugar values on 2 different days were 283 mg/dL and 312 mg/dL. A laboratory review revealed his hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 7 months prior was 5.6%.

Discussion

The high-dose prednisone component of this and other lymphoma therapy regimens can worsen diabetes mellitus (DM) control and/or worsen prediabetes. Patient characteristics that increase the risk of developing glucocorticoid-induced DM after CHOP chemotherapy include age ≥ 60 years, HbA1c > 6.1%, and body mass index > 30.7 This patient did not have DM prior to the FL therapy initiation, but afterwards he met diagnostic criteria for DM. For completeness, other causes for elevated blood glucose should be ruled out (ie, infection, laboratory error, etc.). An oncologist often will triage acute hyperglycemia, treating immediately with IV fluids and/or insulin. Thereafter, ongoing chronic disease management for DM may be best managed by PCPs, certified DM educators, and registered dieticians.

Several programs involving multidisciplinary DM care, comprised of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, certified DM educators, and/or pharmacists have been shown to improve HbA1c, cardiovascular outcomes, and all-cause mortality, while reducing health care costs.8 In addition, patient navigators can assist patients with coordinating visits to disease-state specialists and identifying further educational needs. For example, in 1 program, nonclinical peer navigators were shown to improve the number of appointments attended and reduce HbA1c in a population of patients with DM who were primarily minority, urban, and of low socioeconomic status.9 Thus, integrating DM care shows potential to improve outcomes for patients with lymphoma who develop glucocorticoid

Case Example 2

A 75-year-old male was diagnosed with FL. He was treated initially with bendamustine and rituximab. He required reinitiation of therapy 20 months later when he developed lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and night sweats and began treatment with oral idelalisib, a second-line therapy. Later, the patient presented to his PCP for a routine visit, and on medication reconciliation review, the patient reported regular use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Discussion

Upon consultation with the CPS and the patient’s oncologist, the PCP confirmed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued during therapy and for about 6 months following completion of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii). While use of prophylactic therapy is not necessary for all patients with FL, idelalisib impairs the function of circulating lymphoid B-cells and thus has been associated with an increased risk of serious infection.10 A CPS can provide insight that maximizes medication adherence and efficacy while minimizing food-drug, drug-drug interactions, and AEs. CPS have been shown to: improve adherence to oral therapies, increase prospective monitoring required for safe therapy dose selection, and document assessment of chemotherapy-related AEs.11,12 Thus, multidisciplinary, integrated care is an important component of providing quality oncology care.

Case Example 3

A 60-year-old female presented to her PCP with a 2-week history of shortness of breath and leg swelling. She was treated for FL 4 years previously with 6 cycles of R-CHOP. She reported no chest pain and did not have a prior history of hypertension, DM, or heart disease. On physical exam, she had elevated jugular venous pressure to jaw at 45°, bilateral pulmonary rales, and 2+ pitting pretibial edema. Laboratory tests that included complete blood count, basic chemistries, and thyroid stimulating hormone were unremarkable, though brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 425 pg/mL.

As this patient’s laboratory results and physical examination suggested new-onset congestive heart failure, the PCP obtained an echocardiogram, which demonstrated an ejection fraction of 35% and global hypokinesis. Because the patient was symptomatic, she was admitted to the hospital to begin guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) including IV diuresis.

Discussion

Given the absence of significant risk factors and prior history of coronary artery disease, the most probable cause for this patient’s cardiomyopathy is doxorubicin. Doxorubicin is an anthracycline chemotherapy that can cause nonischemic, dilated cardiomyopathy, particularly when cumulative doses > 400 mg/m2 are administered, or when combined with chest radiation.13 This patient benefited from GDMT for reduced ejection-fraction heart failure (HFrEF). Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes when HFrEF patients are cared for by a multidisciplinary team who focus of volume management as well as uptitration of therapies to target doses.14

Case Example 4

An 80-year-old female was diagnosed with stage III FL but did not require immediate therapy. After developing discomfort due to enlarging lymphadenopathy, she initiated therapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CVP). She presented to her oncologist for consideration of her fifth cycle of R-CVP and reported a burning sensation on the soles of her feet and numbness in her fingertips and toes. On examination, her pulses were intact and there were no signs of infection, reduced blood flow, or edema. The patient demonstrated decreased sensation on monofilament testing. She had no history of DM and a recent HbA1c test was 4.9% An evaluation for other causes of neuropathy, such as hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency was negative. Thus, vincristine therapy was identified as the most likely etiology for her peripheral neuropathy. The oncologist decided to proceed with cycle 5 of chemotherapy but reduced the dose of vincristine by 50%.

Discussion

Vincristine is a microtubule inhibitor used in many chemotherapy regimens and may cause reversible or permanent neuropathy, including autonomic (constipation), sensory (stocking-glove distribution), or motor (foot-drop).15 A nerve conduction study may be indicated as part of the diagnostic evaluation. Treatment for painful sensory neuropathy may include pharmacologic therapy (such as gabapentin, pregabalin, capsaicin cream).16 Podiatrists can provide foot care and may provide shoes and inserts if appropriate. Physical therapists may assist with safety and mobility evaluations and can provide therapeutic exercises and assistive devices that improve function and quality of life.17

Conclusion

As cancer becomes more curable and more manageable, patients with cancer and survivors no longer rely exclusively on their oncologists for medical care. This is increasingly prevalent for patients with incurable but indolent cancers that may be present for years to decades, as acute and cumulative toxicities may complicate existing comorbidities. Thus, in this era of increasingly complex cancer therapies, multidisciplinary medical care that involves PCPs, specialists, and allied medical professionals, is essential for providing care that optimizes health and fully addresses patients’ needs.

1. Friedman EL, Chawla N, Morris PT, et al. Assessing the development of multidisciplinary care: experience of the National Cancer Institute community cancer centers program. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e36-e43.

2. Peterson K, Helfand M, Humphrey L, Christensen V, Carson S. Evidence brief: effectiveness of intensive primary care programs. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Intensive-Primary-Care-Supplement.pdf. Published February 2013. Accessed April 5, 2019.

3. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Oncology medical home recognition. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers-practices/oncology-medical-home. Accessed April 5, 2019.

4. Kahl BS, Yang DT. Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2016;127(17):2055-2063.

5. Dulaney C, Wallace AS, Everett AS, Dover L, McDonald A, Kropp L. Defining health across the cancer continuum. Cureus. 2017;9(2):e1029.

6. Hopkins J, Mumber MP. Patient navigation through the cancer care continuum: an overview. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(4):150-152.

7. Lee SY, Kurita N, Yokoyama Y, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus in patients with lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(5):1385-1390.

8. McGill M, Blonde L, Juliana CN, et al; Global Partnership for Effective Diabetes Management. The interdisciplinary team in type 2 diabetes management: challenges and best practice solutions from real-world scenarios. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2017;7:21-27.

9. Horný M, Glover W, Gupte G, Saraswat A, Vimalananda V, Rosenzweig J. Patient navigation to improve diabetes outpatient care at a safety-net hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):759.

10. Reinwald M, Silva JT, Mueller NJ, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Intracellular signaling pathways: tyrosine kinase and mTOR inhibitors). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(suppl 2):S53-S70.

11. Holle LM, Boehnke Michaud L. Oncology pharmacists in health care delivery: vital members of the cancer care team. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014;10(3):e142-e145.

12. Morgan KP, Muluneh B, Dean AM, Amerine LB. Impact of an integrated oral chemotherapy program on patient adherence. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24(5):332-336.

13. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869-2879.

14. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784.

15. Mora E, Smith EM, Donohoe C, Hertz DL. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in pediatric cancer patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6(11):2416-2430.

16. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941–1967

17. Duregon F, Vendramin B, Bullo V, et al. Effects of exercise on cancer patients suffering chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;121:90-100.

Four case examples illustrate the important role of multidisciplinary medical care for the optimal long-term care of patients with follicular lymphoma.

Four case examples illustrate the important role of multidisciplinary medical care for the optimal long-term care of patients with follicular lymphoma.

Patients benefit from multidisciplinary care that coordinates management of complex medical problems. Traditionally, multidisciplinary cancer care involves oncology specialty providers in fields that include medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary cancer care intends to improve patient outcomes by bringing together different health care providers (HCPs) who are involved in the treatment of patients with cancer. Because new therapies are more effective and allow patients with cancer to live longer, adverse effects (AEs) are more likely to impact patients’ well-being, both while receiving treatment and long after it has completed. Thus, this population may benefit from an expanded approach to multidisciplinary care that includes input from specialty and primary care providers (PCPs), clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS), physical and occupational therapists, and patient navigators and educators.

We present 4 hypothetical cases, based on actual patients, that illustrate opportunities where multidisciplinary care coordination may improve patient experiences. These cases draw on current quality initiatives from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, which has focused on improving the quality of multidisciplinary cancer care at selected community centers, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, which brings together different health professionals to optimize primary care coordination.1,2 In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance has introduced an educational initiative to facilitate implementation of an oncologic medical home.3 This initiative stresses increased multidisciplinary communication, patient-centered care delivery, and reduced fragmentation of care for this population. Despite these guidelines and experiences from other medical specialties, models for integrated cancer care have not been implemented in a prospective fashion within the VHA.

In this article, we focus on opportunities to take collaborative care approaches for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL): a common, incurable, and often indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4 FL was selected because these patients may be treated numerous times and long-term sequalae can accumulate throughout their cancer continuum (a series of health events encompassing cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, relapse, and death).5 HCPs in distinct roles can assist patients with cancer in optimizing their health outcomes and overall wellbeing.6

Case Example 1

A 70-year-old male was diagnosed with stage IV FL. Because of his advanced disease, he began therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). Prednisone was administered at 100 mg daily on the first 5 days of each 21-day cycle. On day 4 of the first treatment cycle, the patient notified his oncologist that he had been very thirsty and his random blood sugar values on 2 different days were 283 mg/dL and 312 mg/dL. A laboratory review revealed his hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 7 months prior was 5.6%.

Discussion

The high-dose prednisone component of this and other lymphoma therapy regimens can worsen diabetes mellitus (DM) control and/or worsen prediabetes. Patient characteristics that increase the risk of developing glucocorticoid-induced DM after CHOP chemotherapy include age ≥ 60 years, HbA1c > 6.1%, and body mass index > 30.7 This patient did not have DM prior to the FL therapy initiation, but afterwards he met diagnostic criteria for DM. For completeness, other causes for elevated blood glucose should be ruled out (ie, infection, laboratory error, etc.). An oncologist often will triage acute hyperglycemia, treating immediately with IV fluids and/or insulin. Thereafter, ongoing chronic disease management for DM may be best managed by PCPs, certified DM educators, and registered dieticians.

Several programs involving multidisciplinary DM care, comprised of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, certified DM educators, and/or pharmacists have been shown to improve HbA1c, cardiovascular outcomes, and all-cause mortality, while reducing health care costs.8 In addition, patient navigators can assist patients with coordinating visits to disease-state specialists and identifying further educational needs. For example, in 1 program, nonclinical peer navigators were shown to improve the number of appointments attended and reduce HbA1c in a population of patients with DM who were primarily minority, urban, and of low socioeconomic status.9 Thus, integrating DM care shows potential to improve outcomes for patients with lymphoma who develop glucocorticoid

Case Example 2

A 75-year-old male was diagnosed with FL. He was treated initially with bendamustine and rituximab. He required reinitiation of therapy 20 months later when he developed lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and night sweats and began treatment with oral idelalisib, a second-line therapy. Later, the patient presented to his PCP for a routine visit, and on medication reconciliation review, the patient reported regular use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Discussion

Upon consultation with the CPS and the patient’s oncologist, the PCP confirmed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued during therapy and for about 6 months following completion of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii). While use of prophylactic therapy is not necessary for all patients with FL, idelalisib impairs the function of circulating lymphoid B-cells and thus has been associated with an increased risk of serious infection.10 A CPS can provide insight that maximizes medication adherence and efficacy while minimizing food-drug, drug-drug interactions, and AEs. CPS have been shown to: improve adherence to oral therapies, increase prospective monitoring required for safe therapy dose selection, and document assessment of chemotherapy-related AEs.11,12 Thus, multidisciplinary, integrated care is an important component of providing quality oncology care.

Case Example 3

A 60-year-old female presented to her PCP with a 2-week history of shortness of breath and leg swelling. She was treated for FL 4 years previously with 6 cycles of R-CHOP. She reported no chest pain and did not have a prior history of hypertension, DM, or heart disease. On physical exam, she had elevated jugular venous pressure to jaw at 45°, bilateral pulmonary rales, and 2+ pitting pretibial edema. Laboratory tests that included complete blood count, basic chemistries, and thyroid stimulating hormone were unremarkable, though brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 425 pg/mL.

As this patient’s laboratory results and physical examination suggested new-onset congestive heart failure, the PCP obtained an echocardiogram, which demonstrated an ejection fraction of 35% and global hypokinesis. Because the patient was symptomatic, she was admitted to the hospital to begin guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) including IV diuresis.

Discussion

Given the absence of significant risk factors and prior history of coronary artery disease, the most probable cause for this patient’s cardiomyopathy is doxorubicin. Doxorubicin is an anthracycline chemotherapy that can cause nonischemic, dilated cardiomyopathy, particularly when cumulative doses > 400 mg/m2 are administered, or when combined with chest radiation.13 This patient benefited from GDMT for reduced ejection-fraction heart failure (HFrEF). Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes when HFrEF patients are cared for by a multidisciplinary team who focus of volume management as well as uptitration of therapies to target doses.14

Case Example 4

An 80-year-old female was diagnosed with stage III FL but did not require immediate therapy. After developing discomfort due to enlarging lymphadenopathy, she initiated therapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CVP). She presented to her oncologist for consideration of her fifth cycle of R-CVP and reported a burning sensation on the soles of her feet and numbness in her fingertips and toes. On examination, her pulses were intact and there were no signs of infection, reduced blood flow, or edema. The patient demonstrated decreased sensation on monofilament testing. She had no history of DM and a recent HbA1c test was 4.9% An evaluation for other causes of neuropathy, such as hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency was negative. Thus, vincristine therapy was identified as the most likely etiology for her peripheral neuropathy. The oncologist decided to proceed with cycle 5 of chemotherapy but reduced the dose of vincristine by 50%.

Discussion

Vincristine is a microtubule inhibitor used in many chemotherapy regimens and may cause reversible or permanent neuropathy, including autonomic (constipation), sensory (stocking-glove distribution), or motor (foot-drop).15 A nerve conduction study may be indicated as part of the diagnostic evaluation. Treatment for painful sensory neuropathy may include pharmacologic therapy (such as gabapentin, pregabalin, capsaicin cream).16 Podiatrists can provide foot care and may provide shoes and inserts if appropriate. Physical therapists may assist with safety and mobility evaluations and can provide therapeutic exercises and assistive devices that improve function and quality of life.17

Conclusion

As cancer becomes more curable and more manageable, patients with cancer and survivors no longer rely exclusively on their oncologists for medical care. This is increasingly prevalent for patients with incurable but indolent cancers that may be present for years to decades, as acute and cumulative toxicities may complicate existing comorbidities. Thus, in this era of increasingly complex cancer therapies, multidisciplinary medical care that involves PCPs, specialists, and allied medical professionals, is essential for providing care that optimizes health and fully addresses patients’ needs.

Patients benefit from multidisciplinary care that coordinates management of complex medical problems. Traditionally, multidisciplinary cancer care involves oncology specialty providers in fields that include medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary cancer care intends to improve patient outcomes by bringing together different health care providers (HCPs) who are involved in the treatment of patients with cancer. Because new therapies are more effective and allow patients with cancer to live longer, adverse effects (AEs) are more likely to impact patients’ well-being, both while receiving treatment and long after it has completed. Thus, this population may benefit from an expanded approach to multidisciplinary care that includes input from specialty and primary care providers (PCPs), clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS), physical and occupational therapists, and patient navigators and educators.

We present 4 hypothetical cases, based on actual patients, that illustrate opportunities where multidisciplinary care coordination may improve patient experiences. These cases draw on current quality initiatives from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, which has focused on improving the quality of multidisciplinary cancer care at selected community centers, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, which brings together different health professionals to optimize primary care coordination.1,2 In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance has introduced an educational initiative to facilitate implementation of an oncologic medical home.3 This initiative stresses increased multidisciplinary communication, patient-centered care delivery, and reduced fragmentation of care for this population. Despite these guidelines and experiences from other medical specialties, models for integrated cancer care have not been implemented in a prospective fashion within the VHA.

In this article, we focus on opportunities to take collaborative care approaches for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL): a common, incurable, and often indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4 FL was selected because these patients may be treated numerous times and long-term sequalae can accumulate throughout their cancer continuum (a series of health events encompassing cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, relapse, and death).5 HCPs in distinct roles can assist patients with cancer in optimizing their health outcomes and overall wellbeing.6

Case Example 1

A 70-year-old male was diagnosed with stage IV FL. Because of his advanced disease, he began therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). Prednisone was administered at 100 mg daily on the first 5 days of each 21-day cycle. On day 4 of the first treatment cycle, the patient notified his oncologist that he had been very thirsty and his random blood sugar values on 2 different days were 283 mg/dL and 312 mg/dL. A laboratory review revealed his hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 7 months prior was 5.6%.

Discussion

The high-dose prednisone component of this and other lymphoma therapy regimens can worsen diabetes mellitus (DM) control and/or worsen prediabetes. Patient characteristics that increase the risk of developing glucocorticoid-induced DM after CHOP chemotherapy include age ≥ 60 years, HbA1c > 6.1%, and body mass index > 30.7 This patient did not have DM prior to the FL therapy initiation, but afterwards he met diagnostic criteria for DM. For completeness, other causes for elevated blood glucose should be ruled out (ie, infection, laboratory error, etc.). An oncologist often will triage acute hyperglycemia, treating immediately with IV fluids and/or insulin. Thereafter, ongoing chronic disease management for DM may be best managed by PCPs, certified DM educators, and registered dieticians.

Several programs involving multidisciplinary DM care, comprised of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, certified DM educators, and/or pharmacists have been shown to improve HbA1c, cardiovascular outcomes, and all-cause mortality, while reducing health care costs.8 In addition, patient navigators can assist patients with coordinating visits to disease-state specialists and identifying further educational needs. For example, in 1 program, nonclinical peer navigators were shown to improve the number of appointments attended and reduce HbA1c in a population of patients with DM who were primarily minority, urban, and of low socioeconomic status.9 Thus, integrating DM care shows potential to improve outcomes for patients with lymphoma who develop glucocorticoid

Case Example 2

A 75-year-old male was diagnosed with FL. He was treated initially with bendamustine and rituximab. He required reinitiation of therapy 20 months later when he developed lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and night sweats and began treatment with oral idelalisib, a second-line therapy. Later, the patient presented to his PCP for a routine visit, and on medication reconciliation review, the patient reported regular use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Discussion

Upon consultation with the CPS and the patient’s oncologist, the PCP confirmed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued during therapy and for about 6 months following completion of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii). While use of prophylactic therapy is not necessary for all patients with FL, idelalisib impairs the function of circulating lymphoid B-cells and thus has been associated with an increased risk of serious infection.10 A CPS can provide insight that maximizes medication adherence and efficacy while minimizing food-drug, drug-drug interactions, and AEs. CPS have been shown to: improve adherence to oral therapies, increase prospective monitoring required for safe therapy dose selection, and document assessment of chemotherapy-related AEs.11,12 Thus, multidisciplinary, integrated care is an important component of providing quality oncology care.

Case Example 3

A 60-year-old female presented to her PCP with a 2-week history of shortness of breath and leg swelling. She was treated for FL 4 years previously with 6 cycles of R-CHOP. She reported no chest pain and did not have a prior history of hypertension, DM, or heart disease. On physical exam, she had elevated jugular venous pressure to jaw at 45°, bilateral pulmonary rales, and 2+ pitting pretibial edema. Laboratory tests that included complete blood count, basic chemistries, and thyroid stimulating hormone were unremarkable, though brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 425 pg/mL.