User login

An Unusual Case of Folliculitis Spinulosa Decalvans

Case Report

A 24-year-old man was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of pustules, atrophic scars, and alopecia on the scalp of 6 years’ duration. Six years prior, erythema, scaling, and follicular keratotic papules had appeared on the superciliary arches, and he started to lose hair from the eyebrows. Three months later, he developed mildly pruritic and painful scaling and pustules on the scalp. These lesions resolved with atrophic scarring accompanied by alopecia. One year later, follicular keratotic papules developed on the cheeks, chest, abdomen, back, lateral upper arms, thighs, and axillae. Two years later, direct microscopy of the lesions on the scalp and fungal culture were negative. After 2 weeks of treatment with roxithromycin (0.15 g twice daily), the scalp pustules dried out and resolved; however, they recurred when the patient stopped taking the medication. Six months later, he was started on isotretinoin treatment (10 mg once daily) for half a year, but no improvement was seen. His parents were nonconsanguineous, and no other family members were affected.

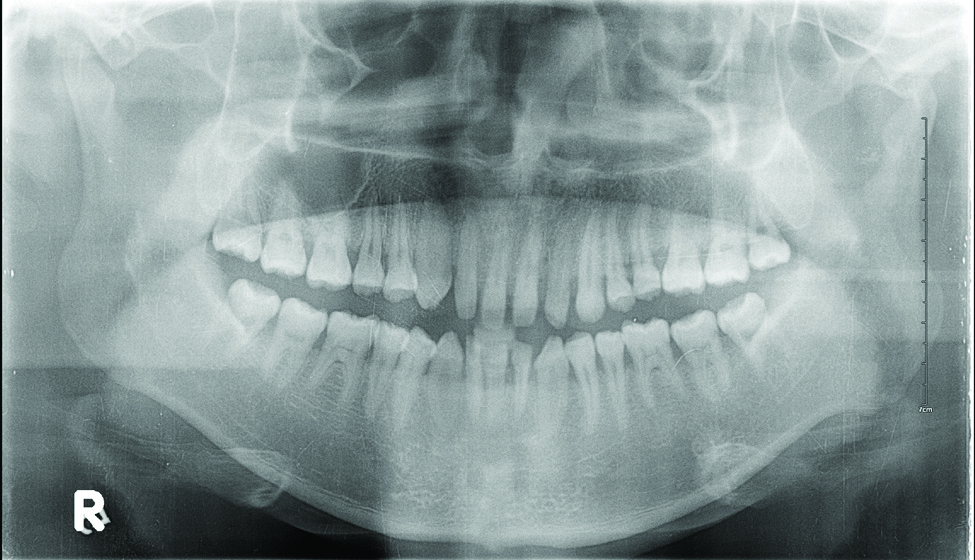

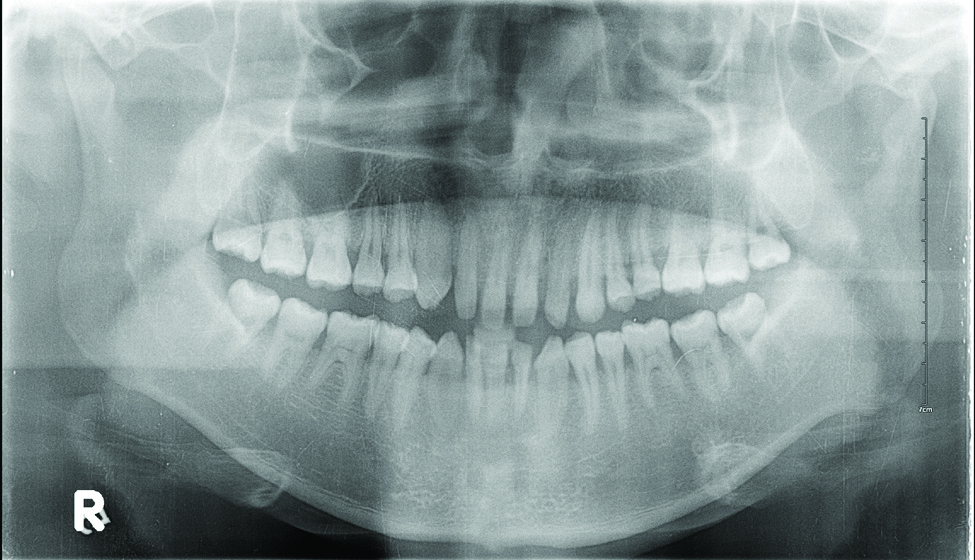

Dermatologic examination revealed large areas of atrophic scarring and alopecia on the scalp. Only a few solitary hairs remained on the top of the head, with the follicles surrounded by keratotic papules, pustules, and black scabs. There was sparse hair on the forehead and temples and scattered hair clusters in the occipital region near the hairline. These follicles also were associated with keratotic papules (Figure 1A). Erythema, scales, and follicular keratotic papules of the superciliary arches with sparse eyebrows and axillary hairs were noted. Follicular keratotic papules also were observed on the cheeks, axillae, chest, abdomen, back, lateral upper arms, and thighs. Dental examination revealed a large space between the upper anterior teeth and the lower anterior teeth. The upper anterior teeth were anteverted, there was congenital absence of right lower central incisors, and the anterior teeth were in deep overbite and overjet (Figure 1B). There was gingival atrophy and calculus dentalis in the upper and lower teeth. He had a fissured tongue with atrophic filiform papillae (Figure 1C).

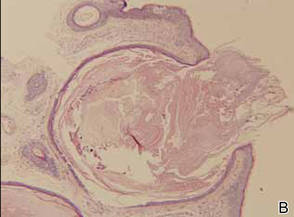

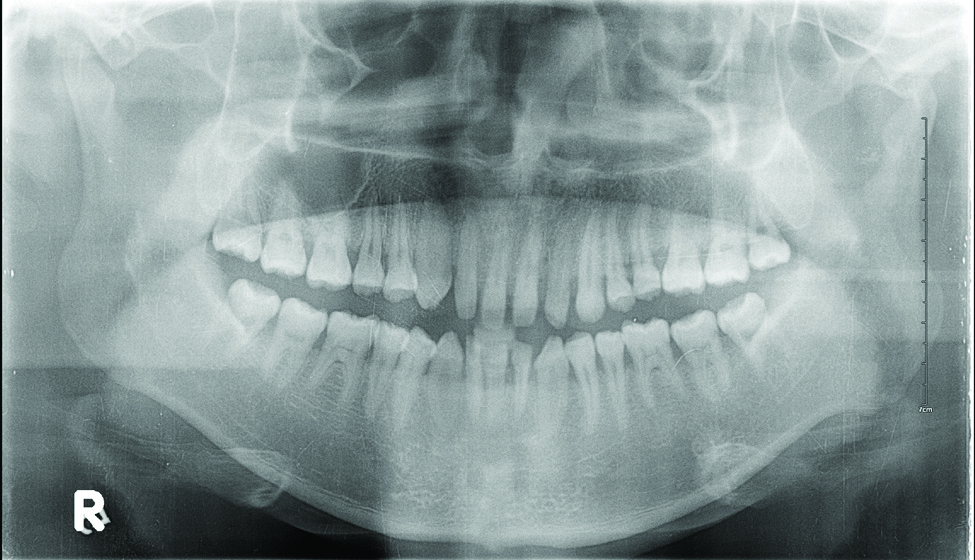

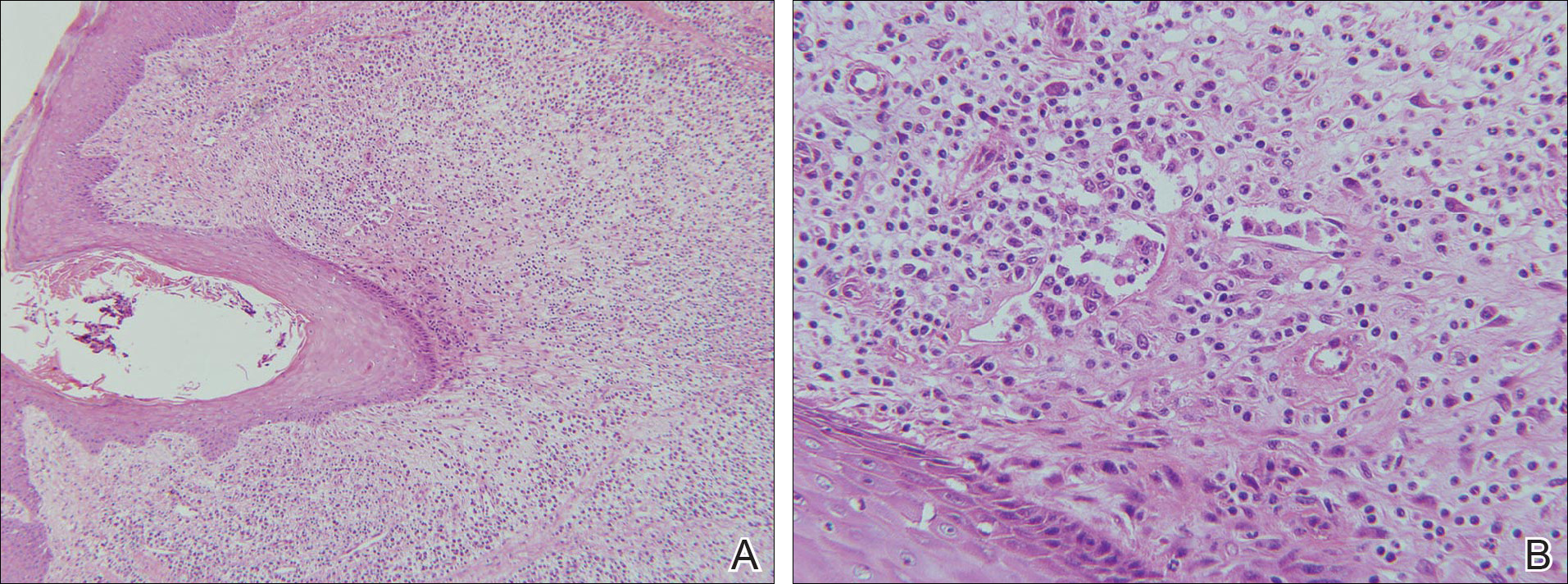

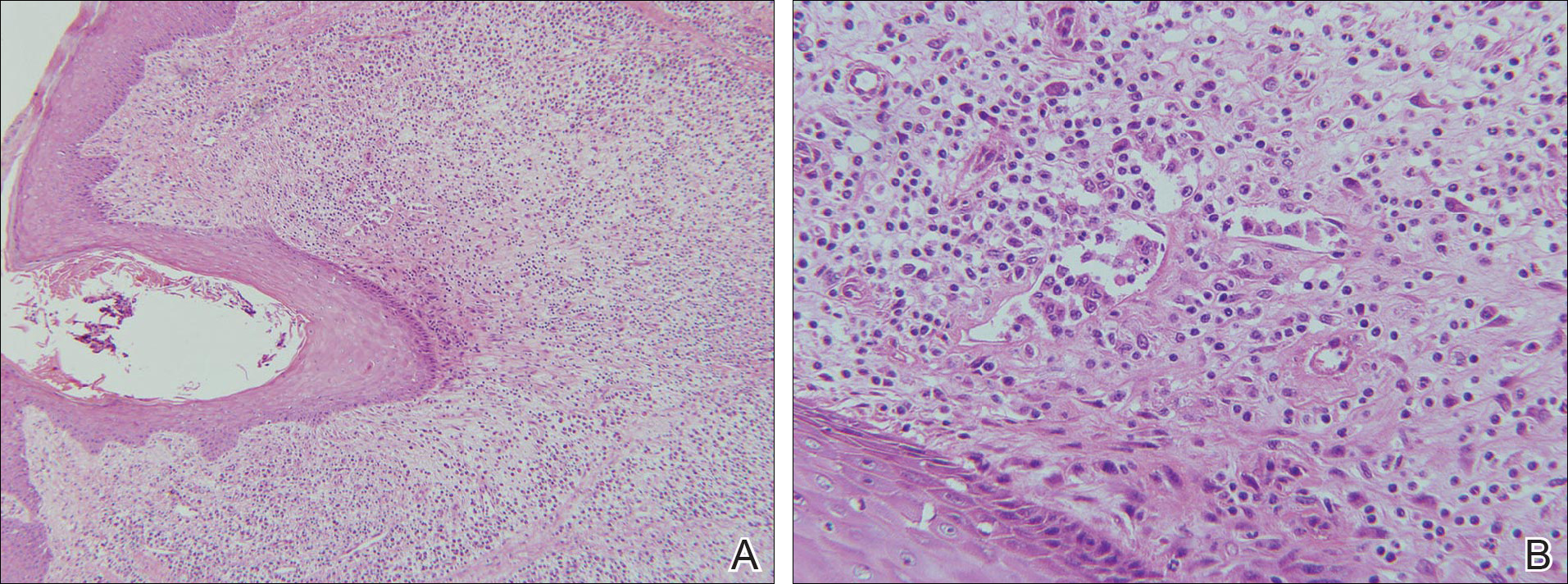

Laboratory testing of the blood, urine, stool, hepatic and renal function, and serum vitamin B2 and B12 levelswere all within reference range. A panoramic radiograph of the occlusal surface showed congenital absence of right lower central incisors (Figure 2), and a lateral projection of a cranial radiograph confirmed that the anterior teeth were in deep overbite and overjet. Direct microscopy and fungal culture of material collected from the dorsal tongue were negative. Direct microscopy and fungal culture of diseased hairs also were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, and human immunodeficiency virus test were negative. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the scalp pustules, and in vitro drug susceptibility testing showed that it was sensitive to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin. Pathological examination of a biopsy of the occipital skin lesions showed a thickened epidermal spinous layer and massive infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and multinucleated giant cells around the hair follicles (Figure 3). Pathological examination of the skin lesions on the superciliary arch also showed infiltration of inflammatory cells in the dermis around the hair follicles.

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of folliculitis spinulosa decalvans (FSD) was made and the patient was started on clarithromycin (0.25 g twice daily), metronidazole (0.2 g 3 times daily), viaminate (50 mg 3 times daily), and fusidic acid cream (coating the affected area twice daily). When he returned for follow-up 1 month later, the pustules had disappeared and the black scabs had fallen off, leaving atrophic scars. The long-term efficacy of this regimen is still under observation.

Comment

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans, along with keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD), keratosis pilaris atrophicans faciei, and atrophoderma vermiculatum, belongs to a group of diseases that includes keratosis pilaris atrophicans. In 1994, Oranje et al1 suggested the term folliculitis spinulosa decalvans, with signs including persistent pustules, characteristic keratotic papules, and scarring alopecia of the scalp, which may be exacerbated at puberty. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the pustules in one study2; however, in another study, repeated cultures were negative.3 Although the main inheritance pattern of KFSD is X-linked, autosomal-dominant inheritance is more common in FSD. Furthermore, there are certain differences in the clinical manifestations of these 2 conditions. Therefore, it remains controversial if FSD is an independent disease or merely a subtype of KFSD.

Our patient’s symptoms manifested after puberty, primarily pustules as well as atrophic and scarring alopecia of the scalp and follicular keratotic papules on the head, face, trunk, lateral upper arms, and thighs. Pathologic examination showed massive infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and multinucleated giant cells around the hair follicles. The clinical and histopathologic findings met the diagnostic criteria for FSD.

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans is a rare clinical condition with few cases reported.3-5 In addition to the aforementioned characteristic clinical manifestations, our patient also had dental anomalies, a fissured tongue, and atrophy of the tongue papillae, which are not known to be associated with FSD. Dental anomalies are characteristic of patients with Down syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, and other conditions.6 Fissured tongue is a normal variant that occurs in 5% to 11% of individuals. It also is a classic but nonspecific feature of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and may occur in psoriasis, Down syndrome, acromegaly, and Sjögren syndrome.7 Atrophy of the tongue papillae is associated with anemia, pellagra, Sjögren syndrome, candidiasis, and other conditions.8 Because there are no known reports of associations between FSD and any of these oral manifestations, it is possible that they were unrelated to FSD in our patient.

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans usually is recurrent and there is no consistently effective treatment for it. Kunte et al4 reported that dapsone (100 mg/d) led to resolution of scalp inflammation and pustules within 1 month. Romine et al2 reported that a 3-week course of dichloroxacillin (250 mg 4 times daily) induced disappearance of pustules around the hair follicles. However, Hallai et al5 reported a patient who was resistant to isotretinoin treatment. In our case, after 1 month of treatment with clarithromycin, metronidazole, viaminate, and fusidic acid cream, the pustules had resolved and the black scabs had fallen off, leaving atrophic scars. The long-term efficacy of this regimen is still under observation.

Conclusion

We report a case of FSD with dental anomalies, a fissured tongue, and atrophy of tongue papillae, none of which have previously been reported in association with FSD. We, therefore, believe that our patient’s oral manifestations are unrelated to FSD.

- Oranje AP, van Osch LD, Oosterwijk JC. Keratosis pilaris atrophicans. one heterogeneous disease or a symptom in different clinical entities? Arch Dermatol. 1994;13:500-502.

- Romine KA, Rothschild JG, Hansen RC. Cicatricial alopecia and keratosis pilaris. keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans. Arch Dermatol. 1997;13:381-384.

- Di Lernia V, Ricci C. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: an uncommon entity within the keratosis pilaris atrophicans spectrum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:255-258.

- Kunte C, Loeser C, Wolff H. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: successful therapy with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5, pt 2):891-892.

- Hallai N, Thompson I, Williams P, et al. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: failure to respond to oral isotretinoin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:223-224.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69.7-69.10.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007:643.

- Mulliken RA, Casner MJ. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:565-575.

Case Report

A 24-year-old man was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of pustules, atrophic scars, and alopecia on the scalp of 6 years’ duration. Six years prior, erythema, scaling, and follicular keratotic papules had appeared on the superciliary arches, and he started to lose hair from the eyebrows. Three months later, he developed mildly pruritic and painful scaling and pustules on the scalp. These lesions resolved with atrophic scarring accompanied by alopecia. One year later, follicular keratotic papules developed on the cheeks, chest, abdomen, back, lateral upper arms, thighs, and axillae. Two years later, direct microscopy of the lesions on the scalp and fungal culture were negative. After 2 weeks of treatment with roxithromycin (0.15 g twice daily), the scalp pustules dried out and resolved; however, they recurred when the patient stopped taking the medication. Six months later, he was started on isotretinoin treatment (10 mg once daily) for half a year, but no improvement was seen. His parents were nonconsanguineous, and no other family members were affected.

Dermatologic examination revealed large areas of atrophic scarring and alopecia on the scalp. Only a few solitary hairs remained on the top of the head, with the follicles surrounded by keratotic papules, pustules, and black scabs. There was sparse hair on the forehead and temples and scattered hair clusters in the occipital region near the hairline. These follicles also were associated with keratotic papules (Figure 1A). Erythema, scales, and follicular keratotic papules of the superciliary arches with sparse eyebrows and axillary hairs were noted. Follicular keratotic papules also were observed on the cheeks, axillae, chest, abdomen, back, lateral upper arms, and thighs. Dental examination revealed a large space between the upper anterior teeth and the lower anterior teeth. The upper anterior teeth were anteverted, there was congenital absence of right lower central incisors, and the anterior teeth were in deep overbite and overjet (Figure 1B). There was gingival atrophy and calculus dentalis in the upper and lower teeth. He had a fissured tongue with atrophic filiform papillae (Figure 1C).

Laboratory testing of the blood, urine, stool, hepatic and renal function, and serum vitamin B2 and B12 levelswere all within reference range. A panoramic radiograph of the occlusal surface showed congenital absence of right lower central incisors (Figure 2), and a lateral projection of a cranial radiograph confirmed that the anterior teeth were in deep overbite and overjet. Direct microscopy and fungal culture of material collected from the dorsal tongue were negative. Direct microscopy and fungal culture of diseased hairs also were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, and human immunodeficiency virus test were negative. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the scalp pustules, and in vitro drug susceptibility testing showed that it was sensitive to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin. Pathological examination of a biopsy of the occipital skin lesions showed a thickened epidermal spinous layer and massive infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and multinucleated giant cells around the hair follicles (Figure 3). Pathological examination of the skin lesions on the superciliary arch also showed infiltration of inflammatory cells in the dermis around the hair follicles.

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of folliculitis spinulosa decalvans (FSD) was made and the patient was started on clarithromycin (0.25 g twice daily), metronidazole (0.2 g 3 times daily), viaminate (50 mg 3 times daily), and fusidic acid cream (coating the affected area twice daily). When he returned for follow-up 1 month later, the pustules had disappeared and the black scabs had fallen off, leaving atrophic scars. The long-term efficacy of this regimen is still under observation.

Comment

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans, along with keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD), keratosis pilaris atrophicans faciei, and atrophoderma vermiculatum, belongs to a group of diseases that includes keratosis pilaris atrophicans. In 1994, Oranje et al1 suggested the term folliculitis spinulosa decalvans, with signs including persistent pustules, characteristic keratotic papules, and scarring alopecia of the scalp, which may be exacerbated at puberty. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the pustules in one study2; however, in another study, repeated cultures were negative.3 Although the main inheritance pattern of KFSD is X-linked, autosomal-dominant inheritance is more common in FSD. Furthermore, there are certain differences in the clinical manifestations of these 2 conditions. Therefore, it remains controversial if FSD is an independent disease or merely a subtype of KFSD.

Our patient’s symptoms manifested after puberty, primarily pustules as well as atrophic and scarring alopecia of the scalp and follicular keratotic papules on the head, face, trunk, lateral upper arms, and thighs. Pathologic examination showed massive infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and multinucleated giant cells around the hair follicles. The clinical and histopathologic findings met the diagnostic criteria for FSD.

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans is a rare clinical condition with few cases reported.3-5 In addition to the aforementioned characteristic clinical manifestations, our patient also had dental anomalies, a fissured tongue, and atrophy of the tongue papillae, which are not known to be associated with FSD. Dental anomalies are characteristic of patients with Down syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, and other conditions.6 Fissured tongue is a normal variant that occurs in 5% to 11% of individuals. It also is a classic but nonspecific feature of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and may occur in psoriasis, Down syndrome, acromegaly, and Sjögren syndrome.7 Atrophy of the tongue papillae is associated with anemia, pellagra, Sjögren syndrome, candidiasis, and other conditions.8 Because there are no known reports of associations between FSD and any of these oral manifestations, it is possible that they were unrelated to FSD in our patient.

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans usually is recurrent and there is no consistently effective treatment for it. Kunte et al4 reported that dapsone (100 mg/d) led to resolution of scalp inflammation and pustules within 1 month. Romine et al2 reported that a 3-week course of dichloroxacillin (250 mg 4 times daily) induced disappearance of pustules around the hair follicles. However, Hallai et al5 reported a patient who was resistant to isotretinoin treatment. In our case, after 1 month of treatment with clarithromycin, metronidazole, viaminate, and fusidic acid cream, the pustules had resolved and the black scabs had fallen off, leaving atrophic scars. The long-term efficacy of this regimen is still under observation.

Conclusion

We report a case of FSD with dental anomalies, a fissured tongue, and atrophy of tongue papillae, none of which have previously been reported in association with FSD. We, therefore, believe that our patient’s oral manifestations are unrelated to FSD.

Case Report

A 24-year-old man was referred to the dermatology department for evaluation of pustules, atrophic scars, and alopecia on the scalp of 6 years’ duration. Six years prior, erythema, scaling, and follicular keratotic papules had appeared on the superciliary arches, and he started to lose hair from the eyebrows. Three months later, he developed mildly pruritic and painful scaling and pustules on the scalp. These lesions resolved with atrophic scarring accompanied by alopecia. One year later, follicular keratotic papules developed on the cheeks, chest, abdomen, back, lateral upper arms, thighs, and axillae. Two years later, direct microscopy of the lesions on the scalp and fungal culture were negative. After 2 weeks of treatment with roxithromycin (0.15 g twice daily), the scalp pustules dried out and resolved; however, they recurred when the patient stopped taking the medication. Six months later, he was started on isotretinoin treatment (10 mg once daily) for half a year, but no improvement was seen. His parents were nonconsanguineous, and no other family members were affected.

Dermatologic examination revealed large areas of atrophic scarring and alopecia on the scalp. Only a few solitary hairs remained on the top of the head, with the follicles surrounded by keratotic papules, pustules, and black scabs. There was sparse hair on the forehead and temples and scattered hair clusters in the occipital region near the hairline. These follicles also were associated with keratotic papules (Figure 1A). Erythema, scales, and follicular keratotic papules of the superciliary arches with sparse eyebrows and axillary hairs were noted. Follicular keratotic papules also were observed on the cheeks, axillae, chest, abdomen, back, lateral upper arms, and thighs. Dental examination revealed a large space between the upper anterior teeth and the lower anterior teeth. The upper anterior teeth were anteverted, there was congenital absence of right lower central incisors, and the anterior teeth were in deep overbite and overjet (Figure 1B). There was gingival atrophy and calculus dentalis in the upper and lower teeth. He had a fissured tongue with atrophic filiform papillae (Figure 1C).

Laboratory testing of the blood, urine, stool, hepatic and renal function, and serum vitamin B2 and B12 levelswere all within reference range. A panoramic radiograph of the occlusal surface showed congenital absence of right lower central incisors (Figure 2), and a lateral projection of a cranial radiograph confirmed that the anterior teeth were in deep overbite and overjet. Direct microscopy and fungal culture of material collected from the dorsal tongue were negative. Direct microscopy and fungal culture of diseased hairs also were negative. A rapid plasma reagin test, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, and human immunodeficiency virus test were negative. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the scalp pustules, and in vitro drug susceptibility testing showed that it was sensitive to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin. Pathological examination of a biopsy of the occipital skin lesions showed a thickened epidermal spinous layer and massive infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and multinucleated giant cells around the hair follicles (Figure 3). Pathological examination of the skin lesions on the superciliary arch also showed infiltration of inflammatory cells in the dermis around the hair follicles.

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of folliculitis spinulosa decalvans (FSD) was made and the patient was started on clarithromycin (0.25 g twice daily), metronidazole (0.2 g 3 times daily), viaminate (50 mg 3 times daily), and fusidic acid cream (coating the affected area twice daily). When he returned for follow-up 1 month later, the pustules had disappeared and the black scabs had fallen off, leaving atrophic scars. The long-term efficacy of this regimen is still under observation.

Comment

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans, along with keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans (KFSD), keratosis pilaris atrophicans faciei, and atrophoderma vermiculatum, belongs to a group of diseases that includes keratosis pilaris atrophicans. In 1994, Oranje et al1 suggested the term folliculitis spinulosa decalvans, with signs including persistent pustules, characteristic keratotic papules, and scarring alopecia of the scalp, which may be exacerbated at puberty. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the pustules in one study2; however, in another study, repeated cultures were negative.3 Although the main inheritance pattern of KFSD is X-linked, autosomal-dominant inheritance is more common in FSD. Furthermore, there are certain differences in the clinical manifestations of these 2 conditions. Therefore, it remains controversial if FSD is an independent disease or merely a subtype of KFSD.

Our patient’s symptoms manifested after puberty, primarily pustules as well as atrophic and scarring alopecia of the scalp and follicular keratotic papules on the head, face, trunk, lateral upper arms, and thighs. Pathologic examination showed massive infiltration of plasma cells, neutrophils, and multinucleated giant cells around the hair follicles. The clinical and histopathologic findings met the diagnostic criteria for FSD.

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans is a rare clinical condition with few cases reported.3-5 In addition to the aforementioned characteristic clinical manifestations, our patient also had dental anomalies, a fissured tongue, and atrophy of the tongue papillae, which are not known to be associated with FSD. Dental anomalies are characteristic of patients with Down syndrome, ectodermal dysplasia, Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, and other conditions.6 Fissured tongue is a normal variant that occurs in 5% to 11% of individuals. It also is a classic but nonspecific feature of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and may occur in psoriasis, Down syndrome, acromegaly, and Sjögren syndrome.7 Atrophy of the tongue papillae is associated with anemia, pellagra, Sjögren syndrome, candidiasis, and other conditions.8 Because there are no known reports of associations between FSD and any of these oral manifestations, it is possible that they were unrelated to FSD in our patient.

Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans usually is recurrent and there is no consistently effective treatment for it. Kunte et al4 reported that dapsone (100 mg/d) led to resolution of scalp inflammation and pustules within 1 month. Romine et al2 reported that a 3-week course of dichloroxacillin (250 mg 4 times daily) induced disappearance of pustules around the hair follicles. However, Hallai et al5 reported a patient who was resistant to isotretinoin treatment. In our case, after 1 month of treatment with clarithromycin, metronidazole, viaminate, and fusidic acid cream, the pustules had resolved and the black scabs had fallen off, leaving atrophic scars. The long-term efficacy of this regimen is still under observation.

Conclusion

We report a case of FSD with dental anomalies, a fissured tongue, and atrophy of tongue papillae, none of which have previously been reported in association with FSD. We, therefore, believe that our patient’s oral manifestations are unrelated to FSD.

- Oranje AP, van Osch LD, Oosterwijk JC. Keratosis pilaris atrophicans. one heterogeneous disease or a symptom in different clinical entities? Arch Dermatol. 1994;13:500-502.

- Romine KA, Rothschild JG, Hansen RC. Cicatricial alopecia and keratosis pilaris. keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans. Arch Dermatol. 1997;13:381-384.

- Di Lernia V, Ricci C. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: an uncommon entity within the keratosis pilaris atrophicans spectrum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:255-258.

- Kunte C, Loeser C, Wolff H. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: successful therapy with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5, pt 2):891-892.

- Hallai N, Thompson I, Williams P, et al. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: failure to respond to oral isotretinoin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:223-224.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69.7-69.10.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007:643.

- Mulliken RA, Casner MJ. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:565-575.

- Oranje AP, van Osch LD, Oosterwijk JC. Keratosis pilaris atrophicans. one heterogeneous disease or a symptom in different clinical entities? Arch Dermatol. 1994;13:500-502.

- Romine KA, Rothschild JG, Hansen RC. Cicatricial alopecia and keratosis pilaris. keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans. Arch Dermatol. 1997;13:381-384.

- Di Lernia V, Ricci C. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: an uncommon entity within the keratosis pilaris atrophicans spectrum. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:255-258.

- Kunte C, Loeser C, Wolff H. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: successful therapy with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(5, pt 2):891-892.

- Hallai N, Thompson I, Williams P, et al. Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans: failure to respond to oral isotretinoin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:223-224.

- Scully C, Hegarty A. The oral cavity and lips. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:69.7-69.10.

- Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007:643.

- Mulliken RA, Casner MJ. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:565-575.

Practice Points

- Folliculitis spinulosa decalvans (FSD) presents with persistent pustules, characteristic keratotic papules, and scarring alopecia of the scalp.

- In the case described here, oral manifestations also were present but are not characteristic of FSD.

Late-Onset Nevus Comedonicus on Both Eyelids With Hypothyroidism

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for papules on both eyelids of 6 months’ duration. She underwent surgery for a thyroid gland adenoma 3 years prior and subsequently experienced hypothyroidism. Levothyroxine sodium was administered daily (100 µg initially; 50 µg over the last 1.5 years). Papules occurred on both eyelids 6 months prior to presentation and gradually increased in number. The center of each papule was filled with a black keratinous plug. The skin lesions became raised after the patient ate fatty foods. The lesions remained entirely asymptomatic and there was no family history of a similar disorder.

Physical examinations showed no systemic abnormalities. Dermatologic examination showed clustered 3- to 4-mm flesh-colored papules on both upper eyelids; the centers of the papules were filled with 1- to 2-mm black keratinous plugs (Figure 1A). Several similar skin lesions existed on the lower eyelids, nasal root, and right side of the nasal dorsum. On laboratory examination, the results of routine blood, urine, and stool tests, as well as renal and hepatic functions, electrolytes, and blood sugar levels, were within reference range. Indicators including triglyceride of 2.50 mmol/L (reference range, 0.40–1.90 mmol/L), total cholesterol of 6.31 mmol/L (reference range, 3.00–5.70 mmol/L), serum total thyroxine (T4) of 5.32 µg/dL (reference range, 6.09–12.23 µg/dL), total triiodothyronine (T3) of 64 ng/dL (reference range, 87–178 ng/dL), serum free thyroxine (FT4) of 0.41 ng/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.12 ng/dL), serum free triiodothyronine (FT3) of 182 pg/dL (reference range, 250–390 pg/dL), and thyrotropin of 33.75 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.34–5.60 µIU/mL) were not within reference range; however, thyroperoxidase antibodies, thyrotropin receptor antibodies, thyroglobulin antibodies, thyroglobulin, and calcitonin were within reference range. Color ultrasonography indicated post–subtotal resection of the bilateral thyroid glands.

|

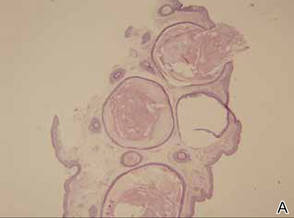

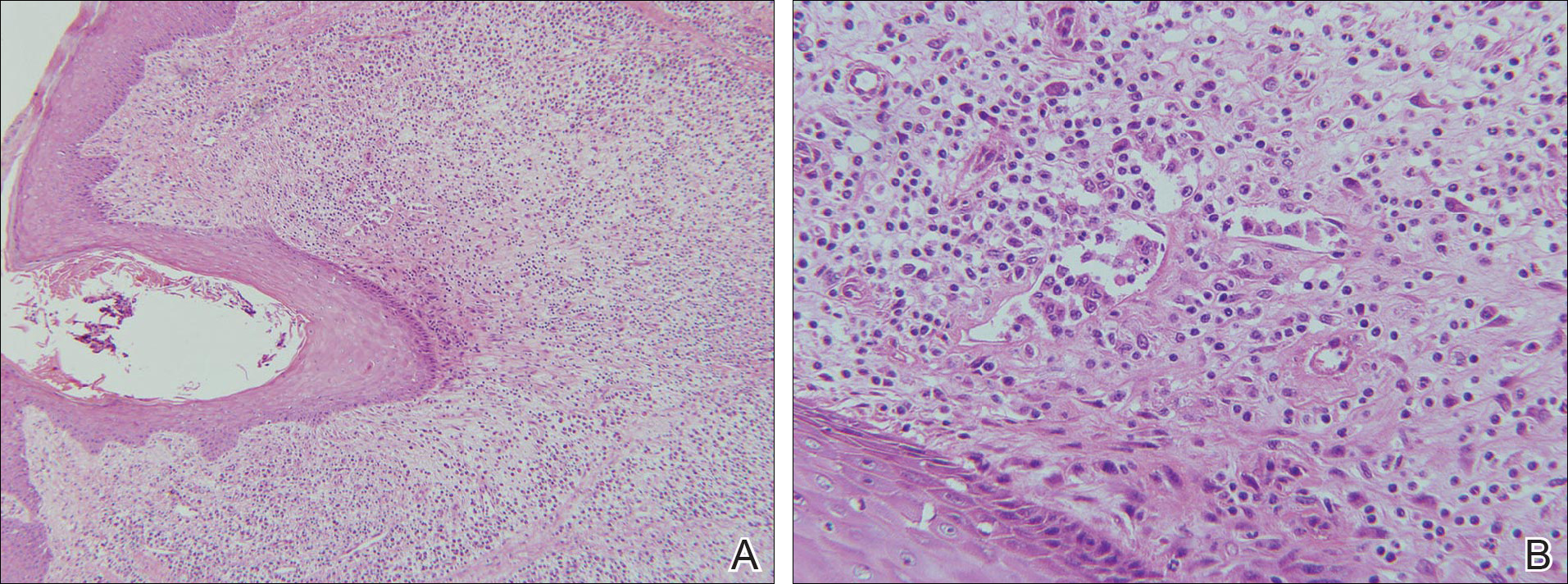

Histopathologic analysis of the skin lesions showed that the epidermis became atrophic and thinner, and several atrophic and cyst-dilated follicular structures existed inside the dermis. Some structures opened through the epidermis; the walls were squamous epithelium and keratin filled the structures (Figure 2). The condition was diagnosed as nevus comedonicus (NC).

The patient was referred to the endocrinology department and treated with levothyroxine sodium (100 µg daily). At 5-month follow-up, the T4, T3, FT4, FT3, and thyrotropin levels were within reference range and most of the skin lesions had resolved (Figure 1B).

Nevus comedonicus is an unusual skin lesion with a predilection for the face, neck, shoulders, upper arms, and trunk. The clinical manifestations include comedonelike papules with centers that are characterized by large, black, solid keratinous plugs. When the plugs are peeled off, volcanic craterlike pits will be left. The skin lesions usually are ribbonlike and clustered on 1 side of the body. Pathologic examination often shows that the epidermis is pitted downward, and the dilated follicular ostia are plugged with keratin.1,2 Paige and Mendelson3 divided NC into 2 types: inflammatory and noninflammatory. Approximately half of NC patients experience cysts, abscesses, fistulae, and scars.4

The exact etiology of NC is unclear. Some researchers believe that it is a congenital hair follicle deformity; more specifically, that it is caused by a developmental defect in the hair follicles in the embryonic stage (ie, abnormal differentiation of epithelial stem cells that differentiate into follicles). Most incidences of NC occur at birth or before growth and development. However, few studies have reported late-onset NC.5

|

The relationship between NC and thyroid disease is unique. Clinical research has shown that hypothyroidism can result in hair loss and cracks.6 In animal experiments, hypothyroidism model mice often experienced degenerative changes of their hair follicles and hair papillae as well as changes in the telogen phase, such as thinning of the outer and inner root sheaths.7 Meanwhile, decreased cell proliferation activity in the hair follicles was observed. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that thyroid hormones have regulatory effects on the growth and development of hair follicles.7

A study on human hair follicles found that thyroid hormone receptor β1 is expressed in human hair follicles.8 Research on in vitro–cultured human hair follicles showed that thyroid hormones T3 and T4 upregulated the proliferation of hair matrix cells and downregulated their apoptosis. Thyroid hormones also prolonged the duration of the hair growth phase (anagen).9 Furthermore, expression of thyrotropin receptor was detected in human hair follicles. Because increased serum thyrotropin levels can lead to clinical hair loss, thyrotropin may inhibit the growth of hair follicles via thyrotropin receptor.10 In our patient, NC occurred on both eyelids when the patient experienced hypothyroidism following thyroid gland adenoma surgery. Following treatment with levothyroxine sodium, the T4, T3, FT4, FT3, and thyrotropin levels were within reference range and most of the skin lesions resolved. Therefore, the occurrence of NC may be related to hypothyroidism in this patient. The low thyroid hormone levels and elevated thyrotropin level possibly induced degenerative changes and injuries to the hair matrix cells, resulting in hair follicle obstruction and accumulation of keratin, which ultimately led to NC. However, the exact relationship between NC and thyroid diseases requires elucidation in future studies.

1. Engber PB. The nevus comedonicus syndrome: a case report with emphasis on associated internal manifestations. Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:745-749.

2. Kirtak N, Inaloz HS, Karakok M, et al. Extensive inflammatory nevus comedonicus involving half of the body. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:434-436.

3. Paige TN, Mendelson CG. Bilateral nevus comedonicus. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:172-175.

4. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

5. Ahn SY, Oh Y, Bak H, et al. Co-occurrence of nevus comedonicus with accessory breast tissue. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:530-531.

6. Freinkel RK, Freinkel N. Hair growth and alopecia in hypothyroidism. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:349-352.

7. Tsujio M, Yoshioka K, Satoh M, et al. Skin morphology of thyroidectomized rats. Vet Pathol. 2008;45:505-511.

8. Billoni N, Buan B, Gautier B, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor β1 is expressed in the human hair follicle. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:645-652.

9. van Beek N, Bodó E, Kromminga A, et al. Thyroid hormones directly alter human hair follicle functions: anagen prolongation and stimulation of both hair matrix keratinocyte proliferation and hair pigmentation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4381-4388.

10. Bodó E, Kromminga A, Bíró T, et al. Human female hair follicles are a direct, nonclassical target for thyroid-stimulating hormone. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1126-1139.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for papules on both eyelids of 6 months’ duration. She underwent surgery for a thyroid gland adenoma 3 years prior and subsequently experienced hypothyroidism. Levothyroxine sodium was administered daily (100 µg initially; 50 µg over the last 1.5 years). Papules occurred on both eyelids 6 months prior to presentation and gradually increased in number. The center of each papule was filled with a black keratinous plug. The skin lesions became raised after the patient ate fatty foods. The lesions remained entirely asymptomatic and there was no family history of a similar disorder.

Physical examinations showed no systemic abnormalities. Dermatologic examination showed clustered 3- to 4-mm flesh-colored papules on both upper eyelids; the centers of the papules were filled with 1- to 2-mm black keratinous plugs (Figure 1A). Several similar skin lesions existed on the lower eyelids, nasal root, and right side of the nasal dorsum. On laboratory examination, the results of routine blood, urine, and stool tests, as well as renal and hepatic functions, electrolytes, and blood sugar levels, were within reference range. Indicators including triglyceride of 2.50 mmol/L (reference range, 0.40–1.90 mmol/L), total cholesterol of 6.31 mmol/L (reference range, 3.00–5.70 mmol/L), serum total thyroxine (T4) of 5.32 µg/dL (reference range, 6.09–12.23 µg/dL), total triiodothyronine (T3) of 64 ng/dL (reference range, 87–178 ng/dL), serum free thyroxine (FT4) of 0.41 ng/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.12 ng/dL), serum free triiodothyronine (FT3) of 182 pg/dL (reference range, 250–390 pg/dL), and thyrotropin of 33.75 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.34–5.60 µIU/mL) were not within reference range; however, thyroperoxidase antibodies, thyrotropin receptor antibodies, thyroglobulin antibodies, thyroglobulin, and calcitonin were within reference range. Color ultrasonography indicated post–subtotal resection of the bilateral thyroid glands.

|

Histopathologic analysis of the skin lesions showed that the epidermis became atrophic and thinner, and several atrophic and cyst-dilated follicular structures existed inside the dermis. Some structures opened through the epidermis; the walls were squamous epithelium and keratin filled the structures (Figure 2). The condition was diagnosed as nevus comedonicus (NC).

The patient was referred to the endocrinology department and treated with levothyroxine sodium (100 µg daily). At 5-month follow-up, the T4, T3, FT4, FT3, and thyrotropin levels were within reference range and most of the skin lesions had resolved (Figure 1B).

Nevus comedonicus is an unusual skin lesion with a predilection for the face, neck, shoulders, upper arms, and trunk. The clinical manifestations include comedonelike papules with centers that are characterized by large, black, solid keratinous plugs. When the plugs are peeled off, volcanic craterlike pits will be left. The skin lesions usually are ribbonlike and clustered on 1 side of the body. Pathologic examination often shows that the epidermis is pitted downward, and the dilated follicular ostia are plugged with keratin.1,2 Paige and Mendelson3 divided NC into 2 types: inflammatory and noninflammatory. Approximately half of NC patients experience cysts, abscesses, fistulae, and scars.4

The exact etiology of NC is unclear. Some researchers believe that it is a congenital hair follicle deformity; more specifically, that it is caused by a developmental defect in the hair follicles in the embryonic stage (ie, abnormal differentiation of epithelial stem cells that differentiate into follicles). Most incidences of NC occur at birth or before growth and development. However, few studies have reported late-onset NC.5

|

The relationship between NC and thyroid disease is unique. Clinical research has shown that hypothyroidism can result in hair loss and cracks.6 In animal experiments, hypothyroidism model mice often experienced degenerative changes of their hair follicles and hair papillae as well as changes in the telogen phase, such as thinning of the outer and inner root sheaths.7 Meanwhile, decreased cell proliferation activity in the hair follicles was observed. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that thyroid hormones have regulatory effects on the growth and development of hair follicles.7

A study on human hair follicles found that thyroid hormone receptor β1 is expressed in human hair follicles.8 Research on in vitro–cultured human hair follicles showed that thyroid hormones T3 and T4 upregulated the proliferation of hair matrix cells and downregulated their apoptosis. Thyroid hormones also prolonged the duration of the hair growth phase (anagen).9 Furthermore, expression of thyrotropin receptor was detected in human hair follicles. Because increased serum thyrotropin levels can lead to clinical hair loss, thyrotropin may inhibit the growth of hair follicles via thyrotropin receptor.10 In our patient, NC occurred on both eyelids when the patient experienced hypothyroidism following thyroid gland adenoma surgery. Following treatment with levothyroxine sodium, the T4, T3, FT4, FT3, and thyrotropin levels were within reference range and most of the skin lesions resolved. Therefore, the occurrence of NC may be related to hypothyroidism in this patient. The low thyroid hormone levels and elevated thyrotropin level possibly induced degenerative changes and injuries to the hair matrix cells, resulting in hair follicle obstruction and accumulation of keratin, which ultimately led to NC. However, the exact relationship between NC and thyroid diseases requires elucidation in future studies.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic for papules on both eyelids of 6 months’ duration. She underwent surgery for a thyroid gland adenoma 3 years prior and subsequently experienced hypothyroidism. Levothyroxine sodium was administered daily (100 µg initially; 50 µg over the last 1.5 years). Papules occurred on both eyelids 6 months prior to presentation and gradually increased in number. The center of each papule was filled with a black keratinous plug. The skin lesions became raised after the patient ate fatty foods. The lesions remained entirely asymptomatic and there was no family history of a similar disorder.

Physical examinations showed no systemic abnormalities. Dermatologic examination showed clustered 3- to 4-mm flesh-colored papules on both upper eyelids; the centers of the papules were filled with 1- to 2-mm black keratinous plugs (Figure 1A). Several similar skin lesions existed on the lower eyelids, nasal root, and right side of the nasal dorsum. On laboratory examination, the results of routine blood, urine, and stool tests, as well as renal and hepatic functions, electrolytes, and blood sugar levels, were within reference range. Indicators including triglyceride of 2.50 mmol/L (reference range, 0.40–1.90 mmol/L), total cholesterol of 6.31 mmol/L (reference range, 3.00–5.70 mmol/L), serum total thyroxine (T4) of 5.32 µg/dL (reference range, 6.09–12.23 µg/dL), total triiodothyronine (T3) of 64 ng/dL (reference range, 87–178 ng/dL), serum free thyroxine (FT4) of 0.41 ng/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.12 ng/dL), serum free triiodothyronine (FT3) of 182 pg/dL (reference range, 250–390 pg/dL), and thyrotropin of 33.75 µIU/mL (reference range, 0.34–5.60 µIU/mL) were not within reference range; however, thyroperoxidase antibodies, thyrotropin receptor antibodies, thyroglobulin antibodies, thyroglobulin, and calcitonin were within reference range. Color ultrasonography indicated post–subtotal resection of the bilateral thyroid glands.

|

Histopathologic analysis of the skin lesions showed that the epidermis became atrophic and thinner, and several atrophic and cyst-dilated follicular structures existed inside the dermis. Some structures opened through the epidermis; the walls were squamous epithelium and keratin filled the structures (Figure 2). The condition was diagnosed as nevus comedonicus (NC).

The patient was referred to the endocrinology department and treated with levothyroxine sodium (100 µg daily). At 5-month follow-up, the T4, T3, FT4, FT3, and thyrotropin levels were within reference range and most of the skin lesions had resolved (Figure 1B).

Nevus comedonicus is an unusual skin lesion with a predilection for the face, neck, shoulders, upper arms, and trunk. The clinical manifestations include comedonelike papules with centers that are characterized by large, black, solid keratinous plugs. When the plugs are peeled off, volcanic craterlike pits will be left. The skin lesions usually are ribbonlike and clustered on 1 side of the body. Pathologic examination often shows that the epidermis is pitted downward, and the dilated follicular ostia are plugged with keratin.1,2 Paige and Mendelson3 divided NC into 2 types: inflammatory and noninflammatory. Approximately half of NC patients experience cysts, abscesses, fistulae, and scars.4

The exact etiology of NC is unclear. Some researchers believe that it is a congenital hair follicle deformity; more specifically, that it is caused by a developmental defect in the hair follicles in the embryonic stage (ie, abnormal differentiation of epithelial stem cells that differentiate into follicles). Most incidences of NC occur at birth or before growth and development. However, few studies have reported late-onset NC.5

|

The relationship between NC and thyroid disease is unique. Clinical research has shown that hypothyroidism can result in hair loss and cracks.6 In animal experiments, hypothyroidism model mice often experienced degenerative changes of their hair follicles and hair papillae as well as changes in the telogen phase, such as thinning of the outer and inner root sheaths.7 Meanwhile, decreased cell proliferation activity in the hair follicles was observed. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that thyroid hormones have regulatory effects on the growth and development of hair follicles.7

A study on human hair follicles found that thyroid hormone receptor β1 is expressed in human hair follicles.8 Research on in vitro–cultured human hair follicles showed that thyroid hormones T3 and T4 upregulated the proliferation of hair matrix cells and downregulated their apoptosis. Thyroid hormones also prolonged the duration of the hair growth phase (anagen).9 Furthermore, expression of thyrotropin receptor was detected in human hair follicles. Because increased serum thyrotropin levels can lead to clinical hair loss, thyrotropin may inhibit the growth of hair follicles via thyrotropin receptor.10 In our patient, NC occurred on both eyelids when the patient experienced hypothyroidism following thyroid gland adenoma surgery. Following treatment with levothyroxine sodium, the T4, T3, FT4, FT3, and thyrotropin levels were within reference range and most of the skin lesions resolved. Therefore, the occurrence of NC may be related to hypothyroidism in this patient. The low thyroid hormone levels and elevated thyrotropin level possibly induced degenerative changes and injuries to the hair matrix cells, resulting in hair follicle obstruction and accumulation of keratin, which ultimately led to NC. However, the exact relationship between NC and thyroid diseases requires elucidation in future studies.

1. Engber PB. The nevus comedonicus syndrome: a case report with emphasis on associated internal manifestations. Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:745-749.

2. Kirtak N, Inaloz HS, Karakok M, et al. Extensive inflammatory nevus comedonicus involving half of the body. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:434-436.

3. Paige TN, Mendelson CG. Bilateral nevus comedonicus. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:172-175.

4. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

5. Ahn SY, Oh Y, Bak H, et al. Co-occurrence of nevus comedonicus with accessory breast tissue. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:530-531.

6. Freinkel RK, Freinkel N. Hair growth and alopecia in hypothyroidism. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:349-352.

7. Tsujio M, Yoshioka K, Satoh M, et al. Skin morphology of thyroidectomized rats. Vet Pathol. 2008;45:505-511.

8. Billoni N, Buan B, Gautier B, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor β1 is expressed in the human hair follicle. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:645-652.

9. van Beek N, Bodó E, Kromminga A, et al. Thyroid hormones directly alter human hair follicle functions: anagen prolongation and stimulation of both hair matrix keratinocyte proliferation and hair pigmentation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4381-4388.

10. Bodó E, Kromminga A, Bíró T, et al. Human female hair follicles are a direct, nonclassical target for thyroid-stimulating hormone. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1126-1139.

1. Engber PB. The nevus comedonicus syndrome: a case report with emphasis on associated internal manifestations. Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:745-749.

2. Kirtak N, Inaloz HS, Karakok M, et al. Extensive inflammatory nevus comedonicus involving half of the body. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:434-436.

3. Paige TN, Mendelson CG. Bilateral nevus comedonicus. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:172-175.

4. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

5. Ahn SY, Oh Y, Bak H, et al. Co-occurrence of nevus comedonicus with accessory breast tissue. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:530-531.

6. Freinkel RK, Freinkel N. Hair growth and alopecia in hypothyroidism. Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:349-352.

7. Tsujio M, Yoshioka K, Satoh M, et al. Skin morphology of thyroidectomized rats. Vet Pathol. 2008;45:505-511.

8. Billoni N, Buan B, Gautier B, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor β1 is expressed in the human hair follicle. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:645-652.

9. van Beek N, Bodó E, Kromminga A, et al. Thyroid hormones directly alter human hair follicle functions: anagen prolongation and stimulation of both hair matrix keratinocyte proliferation and hair pigmentation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4381-4388.

10. Bodó E, Kromminga A, Bíró T, et al. Human female hair follicles are a direct, nonclassical target for thyroid-stimulating hormone. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1126-1139.