User login

Coordination of Care Between Primary Care and Oncology for Patients With Prostate Cancer (FULL)

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

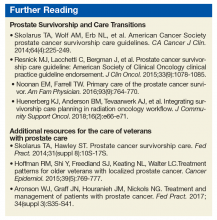

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.