User login

Finally, 2020 is coming to an end, but the agony its viral pandemic inflicted on the entire world population will continue for a long time. And much as we would like to forget its damaging effects, it will surely be etched into our brains for the rest of our lives. The children who suffered the pain of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will endure its emotional scars for the rest of the 21st century.

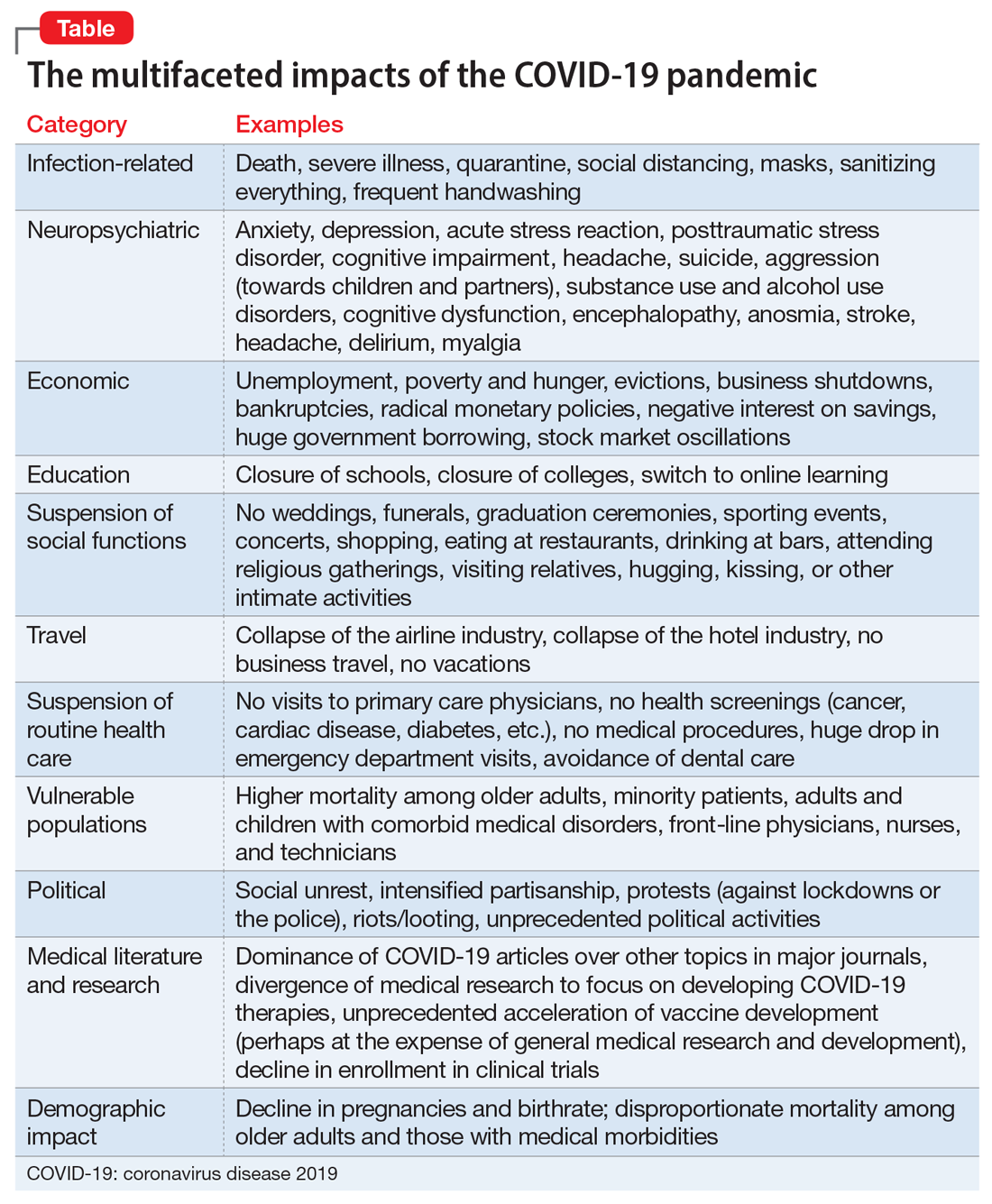

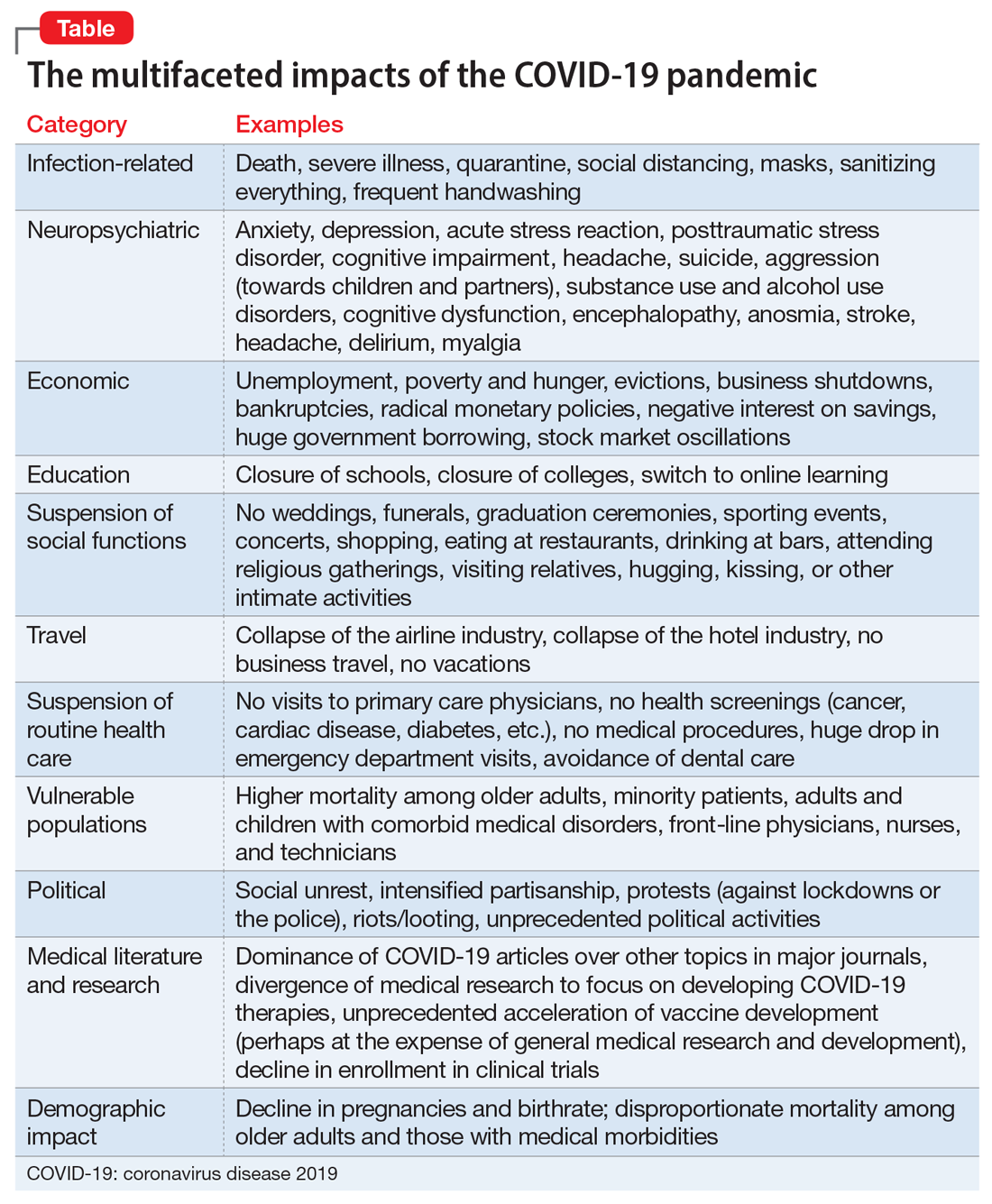

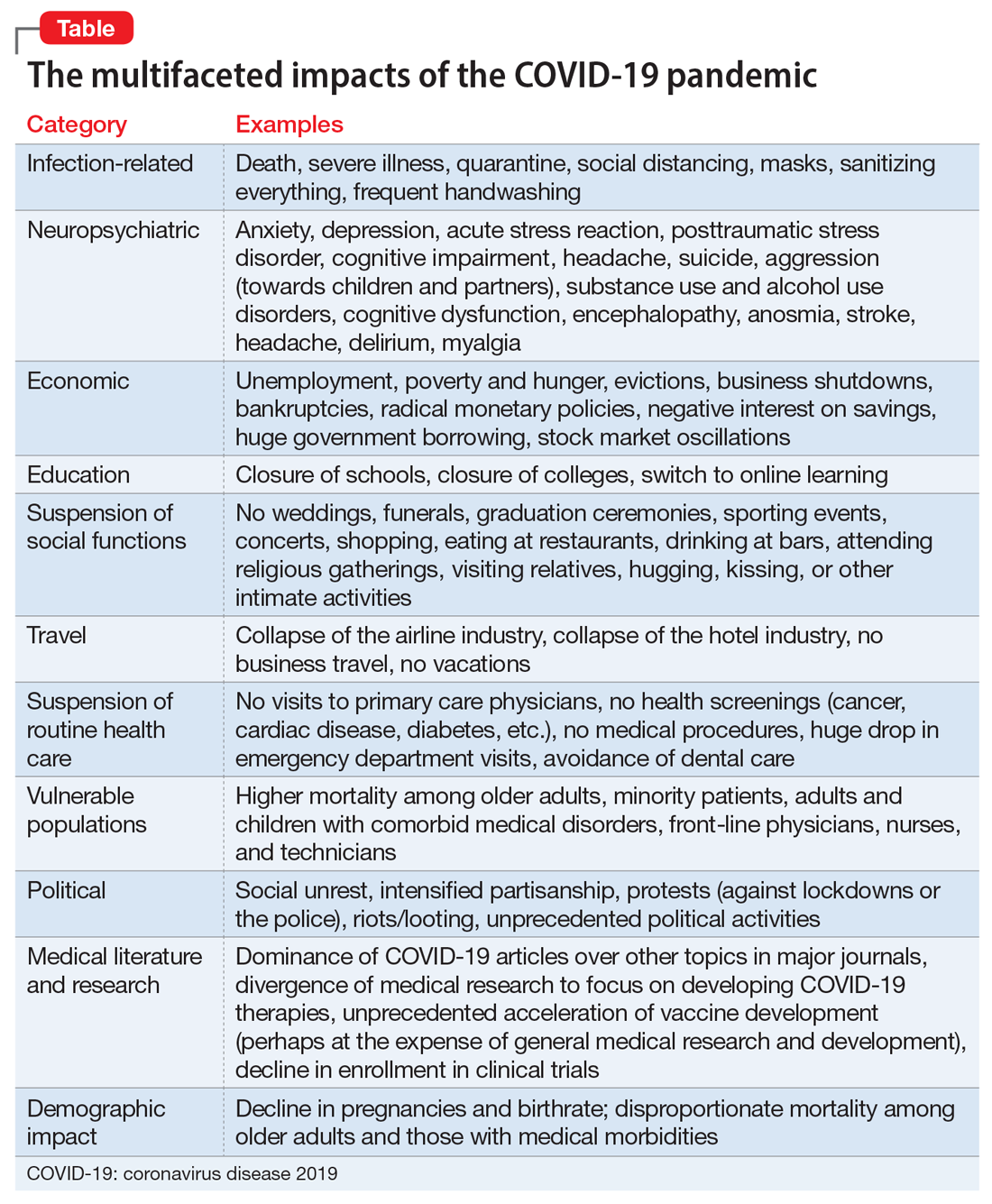

Reading about the plagues of the past doesn’t come close to experiencing it and suffering through it. COVID-19 will continue to have ripple effects on every aspect of life on this planet, on individuals and on societies all over the world, especially on the biopsychosocial well-being of billions of humans around the globe.

Unprecedented disruptions

Think of the unprecedented disruptions inflicted by the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic on our neural circuits. One of the wonders of the human brain is its continuous remodeling due to experiential neuroplasticity, and the formation of dendritic spines that immediately encode the memories of every experience. The turmoil of 2020 and its virulent pandemic will be forever etched into our collective brains, especially in our hippocampi and amygdalae. The impact on the developing brains of our children and grandchildren could be profound and may induce epigenetic changes that trigger psychopathology in the future.1,2

As with the dinosaurs, the 2020 pandemic is like a “viral asteroid” that left devastation on our social fabric and psychological well-being in its wake. We now have deep empathy with our 1918 ancestors and their tribulations, although so far, in the United States the proportion of people infected with COVID-19 (3% as of mid-November 20203) is dwarfed by the proportion infected with the influenza virus a century ago (30%). As of mid-November 2020, the number of global COVID-19 deaths (1.3 million3) was a tiny fraction of the 1918 influenza pandemic deaths (50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States4). Amazingly, researchers did not even know whether the killer germ was a virus or a bacterium until 1930, and it then took another 75 years to decode the genome of the influenza virus in 2005. In contrast, it took only a few short weeks to decode the genome of the virus that causes COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2), and to begin developing multiple vaccines “at warp speed.” No vaccine or therapies were ever developed for victims of the 1918 pandemic.

An abundance of articles has been published about the pandemic since it ambushed us early in 2020, including many in

Most psychiatrists are familiar with the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale,22 which contains 43 life events that cumulatively can progressively increase the odds of physical illness. It is likely that most of the world’s population will score very high on the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale, which would predict an increased risk of medical illness, even after the pandemic subsides.

Exacerbating the situation is that hospitals and clinics had to shut down most of their operations to focus their resources on treating patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. This halted all routine screenings for cancer and heart, kidney, liver, lung, or brain diseases. In addition, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, angiograms, or biopsies abruptly stopped, resulting in a surge of non–COVID-19 medical disorders and mortality as reported in several articles across many specialties.23 Going forward, in addition to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there is a significant likelihood of an increase in myriad medical disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously inflicting both direct and indirect casualties as it stretches into the next year and perhaps longer. The only hope for the community of nations is the rapid arrival of evidence-based treatments and vaccine(s).

Continue to: A progression of relentless stress

A progression of relentless stress

At the core of this pandemic is relentless stress. When it began in early 2020, the pandemic ignited an acute stress reaction due to the fear of death and the oddness of being isolated at home. Aggravating the acute stress was the realization that life as we knew it suddenly disappeared and all business or social activities had come to a screeching halt. It was almost surreal when streets usually bustling with human activity (such as Times Square in New York or Michigan Avenue in Chicago) became completely deserted and eerily silent. In addition, more stress was generated from watching television or scrolling through social media and being inundated with morbid and frightening news and updates about the number of individuals who became infected or died, and the official projections of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fatalities. Further intensifying the stress was hearing that there was a shortage of personal protective equipment (even masks), a lack of ventilators, and the absence of any medications to fight the overwhelming viral infection. Especially stressed were the front-line physicians and nurses, who heroically transcended their fears to save their patients’ lives. The sight of refrigerated trucks serving as temporary morgues outside hospital doors was chilling. The world became a macabre place where people died in hospitals without any relative to hold their hands or comfort them, and then were buried quickly without any formal funerals due to mandatory social distancing. The inability of families to grieve for their loved ones added another poignant layer of sadness and distress to the survivors who were unable to bid their loved ones goodbye. This was a jarring example of adding insult to injury.

With the protraction of the exceptional changes imposed by the pandemic, the acute stress reaction transmuted into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a wide scale. Millions of previously healthy individuals began to succumb to the symptoms of PTSD (irritability, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, and bad dreams). The heaviest burden was inflicted on our patients, across all ages, with preexisting psychiatric conditions, who comprise approximately 25% of the population per the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study.24 These vulnerable patients, whom we see in our clinics and hospitals every day, had a significant exacerbation of their psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, psychosis, binge eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol and substance use disorders, child abuse, and intimate partner violence.25,26 The saving grace was the rapid adoption of telepsychiatry, which our psychiatric patients rapidly accepted. Many of them found it more convenient than dressing and driving and parking at the clinic. It also enabled psychiatrists to obtain useful collateral information from family members or partners.

If something good comes from this catastrophic social stress that emotionally hobbled the entire population, it would be the dilution of the stigma of mental illness because everyone has become more empathic due to their personal experience. Optimistically, this may also help expedite true health care parity for psychiatric brain disorders. And perhaps the government may see the need to train more psychiatrists and fund a higher number of residency stipends to all training programs.

Quo vadis COVID-19?

So, looking through the dense fog of the pandemic fatigue, what will 2021 bring us? Will waves of COVID-19 lead to pandemic exhaustion? Will the frayed public mental health care system be able to handle the surge of frayed nerves? Will social distancing intensify the widespread emotional disquietude? Will the children be able to manifest resilience and avoid disabling psychiatric disorders? Will the survivors of COVID-19 infections suffer from post–COVD-19 neuropsychiatric and other medical sequelae? Will efficacious therapies and vaccines emerge to blunt the spread of the virus? Will we all be able to gather in stadiums and arenas to enjoy sporting events, shows, and concerts? Will eating at our favorite restaurants become routine again? Will engaged couples be able to organize well-attended weddings and receptions? Will airplanes and hotels be fully booked again? Importantly, will all children and college students be able to resume their education in person and socialize ad lib? Will we be able to shed our masks and hug each other hello and goodbye? Will scientific journals and social media cover a wide array of topics again as before? Will the number of deaths dwindle to zero, and will we return to worrying mainly about the usual seasonal flu? Will everyone be able to leave home and go to work again?

I hope that the thick dust of this 2020 viral asteroid will settle in 2021, and that “normalcy” is eventually restored to our lives, allowing us to deal with other ongoing stresses such as social unrest and political hyperpartisanship.

1. Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, et al. Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(5):642-649.

2. Zatti C, Rosa V, Barros A, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide attempt: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from the last decade. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:353-358.

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1918 Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html. Accessed November 4, 2020.

5. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

6. Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-33.

7. Joshi KG. Taking care of ourselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):46-47.

8. Frank B, Peterson T, Gupta S, et al. Telepsychiatry: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):16-23.

9. Chahal K. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):31-33.

10. Arbuck D. Changes in patient behavior during COVID-19: what I’ve observed. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):46-47.

11. Joshi KG. Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: understanding the rules. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e12-e14.

12. Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

13. Brooks V. COVID-19’s effects on emergency psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):33-36,38-39.

14. Desarbo JR, DeSarbo L. Anorexia nervosa and COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(8):23-28.

15. Freudenreich O, Kontos N, Querques J. COVID-19 and patients with serious mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):24-27,33-39.

16. Ryznar E. Evaluating patients’ decision-making capacity during COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):34-40.

17. Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

18. Lodhi S, Marett C. Using seclusion to prevent COVID-19 transmission on inpatient psychiatry units. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):37-41,53.

19. Nasrallah HA. COVID-19 and the precipitous dismantlement of societal norms. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):12-14,16-17.

20. Nasrallah HA. The cataclysmic COVID-19 pandemic: THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):7-8,16.

21. Nasrallah HA. During a viral pandemic, anxiety is endemic: the psychiatric aspects of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):e3-e5.

22. Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213-218.

23. Berkwits M, Flanagin A, Bauchner H, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the JAMA Network. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1159-1160.

24. Robins LN, Regier DA, eds. Psychiatric disorders in America. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1991.

25. Meninger KA. Psychosis associated with influenza. I. General data: statistical analysis. JAMA. 1919;72(4):235-241.

26. Simon NM, Saxe GN, Marmar CR. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1493-1494.

Finally, 2020 is coming to an end, but the agony its viral pandemic inflicted on the entire world population will continue for a long time. And much as we would like to forget its damaging effects, it will surely be etched into our brains for the rest of our lives. The children who suffered the pain of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will endure its emotional scars for the rest of the 21st century.

Reading about the plagues of the past doesn’t come close to experiencing it and suffering through it. COVID-19 will continue to have ripple effects on every aspect of life on this planet, on individuals and on societies all over the world, especially on the biopsychosocial well-being of billions of humans around the globe.

Unprecedented disruptions

Think of the unprecedented disruptions inflicted by the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic on our neural circuits. One of the wonders of the human brain is its continuous remodeling due to experiential neuroplasticity, and the formation of dendritic spines that immediately encode the memories of every experience. The turmoil of 2020 and its virulent pandemic will be forever etched into our collective brains, especially in our hippocampi and amygdalae. The impact on the developing brains of our children and grandchildren could be profound and may induce epigenetic changes that trigger psychopathology in the future.1,2

As with the dinosaurs, the 2020 pandemic is like a “viral asteroid” that left devastation on our social fabric and psychological well-being in its wake. We now have deep empathy with our 1918 ancestors and their tribulations, although so far, in the United States the proportion of people infected with COVID-19 (3% as of mid-November 20203) is dwarfed by the proportion infected with the influenza virus a century ago (30%). As of mid-November 2020, the number of global COVID-19 deaths (1.3 million3) was a tiny fraction of the 1918 influenza pandemic deaths (50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States4). Amazingly, researchers did not even know whether the killer germ was a virus or a bacterium until 1930, and it then took another 75 years to decode the genome of the influenza virus in 2005. In contrast, it took only a few short weeks to decode the genome of the virus that causes COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2), and to begin developing multiple vaccines “at warp speed.” No vaccine or therapies were ever developed for victims of the 1918 pandemic.

An abundance of articles has been published about the pandemic since it ambushed us early in 2020, including many in

Most psychiatrists are familiar with the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale,22 which contains 43 life events that cumulatively can progressively increase the odds of physical illness. It is likely that most of the world’s population will score very high on the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale, which would predict an increased risk of medical illness, even after the pandemic subsides.

Exacerbating the situation is that hospitals and clinics had to shut down most of their operations to focus their resources on treating patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. This halted all routine screenings for cancer and heart, kidney, liver, lung, or brain diseases. In addition, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, angiograms, or biopsies abruptly stopped, resulting in a surge of non–COVID-19 medical disorders and mortality as reported in several articles across many specialties.23 Going forward, in addition to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there is a significant likelihood of an increase in myriad medical disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously inflicting both direct and indirect casualties as it stretches into the next year and perhaps longer. The only hope for the community of nations is the rapid arrival of evidence-based treatments and vaccine(s).

Continue to: A progression of relentless stress

A progression of relentless stress

At the core of this pandemic is relentless stress. When it began in early 2020, the pandemic ignited an acute stress reaction due to the fear of death and the oddness of being isolated at home. Aggravating the acute stress was the realization that life as we knew it suddenly disappeared and all business or social activities had come to a screeching halt. It was almost surreal when streets usually bustling with human activity (such as Times Square in New York or Michigan Avenue in Chicago) became completely deserted and eerily silent. In addition, more stress was generated from watching television or scrolling through social media and being inundated with morbid and frightening news and updates about the number of individuals who became infected or died, and the official projections of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fatalities. Further intensifying the stress was hearing that there was a shortage of personal protective equipment (even masks), a lack of ventilators, and the absence of any medications to fight the overwhelming viral infection. Especially stressed were the front-line physicians and nurses, who heroically transcended their fears to save their patients’ lives. The sight of refrigerated trucks serving as temporary morgues outside hospital doors was chilling. The world became a macabre place where people died in hospitals without any relative to hold their hands or comfort them, and then were buried quickly without any formal funerals due to mandatory social distancing. The inability of families to grieve for their loved ones added another poignant layer of sadness and distress to the survivors who were unable to bid their loved ones goodbye. This was a jarring example of adding insult to injury.

With the protraction of the exceptional changes imposed by the pandemic, the acute stress reaction transmuted into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a wide scale. Millions of previously healthy individuals began to succumb to the symptoms of PTSD (irritability, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, and bad dreams). The heaviest burden was inflicted on our patients, across all ages, with preexisting psychiatric conditions, who comprise approximately 25% of the population per the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study.24 These vulnerable patients, whom we see in our clinics and hospitals every day, had a significant exacerbation of their psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, psychosis, binge eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol and substance use disorders, child abuse, and intimate partner violence.25,26 The saving grace was the rapid adoption of telepsychiatry, which our psychiatric patients rapidly accepted. Many of them found it more convenient than dressing and driving and parking at the clinic. It also enabled psychiatrists to obtain useful collateral information from family members or partners.

If something good comes from this catastrophic social stress that emotionally hobbled the entire population, it would be the dilution of the stigma of mental illness because everyone has become more empathic due to their personal experience. Optimistically, this may also help expedite true health care parity for psychiatric brain disorders. And perhaps the government may see the need to train more psychiatrists and fund a higher number of residency stipends to all training programs.

Quo vadis COVID-19?

So, looking through the dense fog of the pandemic fatigue, what will 2021 bring us? Will waves of COVID-19 lead to pandemic exhaustion? Will the frayed public mental health care system be able to handle the surge of frayed nerves? Will social distancing intensify the widespread emotional disquietude? Will the children be able to manifest resilience and avoid disabling psychiatric disorders? Will the survivors of COVID-19 infections suffer from post–COVD-19 neuropsychiatric and other medical sequelae? Will efficacious therapies and vaccines emerge to blunt the spread of the virus? Will we all be able to gather in stadiums and arenas to enjoy sporting events, shows, and concerts? Will eating at our favorite restaurants become routine again? Will engaged couples be able to organize well-attended weddings and receptions? Will airplanes and hotels be fully booked again? Importantly, will all children and college students be able to resume their education in person and socialize ad lib? Will we be able to shed our masks and hug each other hello and goodbye? Will scientific journals and social media cover a wide array of topics again as before? Will the number of deaths dwindle to zero, and will we return to worrying mainly about the usual seasonal flu? Will everyone be able to leave home and go to work again?

I hope that the thick dust of this 2020 viral asteroid will settle in 2021, and that “normalcy” is eventually restored to our lives, allowing us to deal with other ongoing stresses such as social unrest and political hyperpartisanship.

Finally, 2020 is coming to an end, but the agony its viral pandemic inflicted on the entire world population will continue for a long time. And much as we would like to forget its damaging effects, it will surely be etched into our brains for the rest of our lives. The children who suffered the pain of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will endure its emotional scars for the rest of the 21st century.

Reading about the plagues of the past doesn’t come close to experiencing it and suffering through it. COVID-19 will continue to have ripple effects on every aspect of life on this planet, on individuals and on societies all over the world, especially on the biopsychosocial well-being of billions of humans around the globe.

Unprecedented disruptions

Think of the unprecedented disruptions inflicted by the trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic on our neural circuits. One of the wonders of the human brain is its continuous remodeling due to experiential neuroplasticity, and the formation of dendritic spines that immediately encode the memories of every experience. The turmoil of 2020 and its virulent pandemic will be forever etched into our collective brains, especially in our hippocampi and amygdalae. The impact on the developing brains of our children and grandchildren could be profound and may induce epigenetic changes that trigger psychopathology in the future.1,2

As with the dinosaurs, the 2020 pandemic is like a “viral asteroid” that left devastation on our social fabric and psychological well-being in its wake. We now have deep empathy with our 1918 ancestors and their tribulations, although so far, in the United States the proportion of people infected with COVID-19 (3% as of mid-November 20203) is dwarfed by the proportion infected with the influenza virus a century ago (30%). As of mid-November 2020, the number of global COVID-19 deaths (1.3 million3) was a tiny fraction of the 1918 influenza pandemic deaths (50 million worldwide and 675,000 in the United States4). Amazingly, researchers did not even know whether the killer germ was a virus or a bacterium until 1930, and it then took another 75 years to decode the genome of the influenza virus in 2005. In contrast, it took only a few short weeks to decode the genome of the virus that causes COVID-19 (severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2), and to begin developing multiple vaccines “at warp speed.” No vaccine or therapies were ever developed for victims of the 1918 pandemic.

An abundance of articles has been published about the pandemic since it ambushed us early in 2020, including many in

Most psychiatrists are familiar with the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale,22 which contains 43 life events that cumulatively can progressively increase the odds of physical illness. It is likely that most of the world’s population will score very high on the Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale, which would predict an increased risk of medical illness, even after the pandemic subsides.

Exacerbating the situation is that hospitals and clinics had to shut down most of their operations to focus their resources on treating patients with COVID-19 in ICUs. This halted all routine screenings for cancer and heart, kidney, liver, lung, or brain diseases. In addition, diagnostic or therapeutic procedures such as endoscopies, colonoscopies, angiograms, or biopsies abruptly stopped, resulting in a surge of non–COVID-19 medical disorders and mortality as reported in several articles across many specialties.23 Going forward, in addition to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, there is a significant likelihood of an increase in myriad medical disorders. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously inflicting both direct and indirect casualties as it stretches into the next year and perhaps longer. The only hope for the community of nations is the rapid arrival of evidence-based treatments and vaccine(s).

Continue to: A progression of relentless stress

A progression of relentless stress

At the core of this pandemic is relentless stress. When it began in early 2020, the pandemic ignited an acute stress reaction due to the fear of death and the oddness of being isolated at home. Aggravating the acute stress was the realization that life as we knew it suddenly disappeared and all business or social activities had come to a screeching halt. It was almost surreal when streets usually bustling with human activity (such as Times Square in New York or Michigan Avenue in Chicago) became completely deserted and eerily silent. In addition, more stress was generated from watching television or scrolling through social media and being inundated with morbid and frightening news and updates about the number of individuals who became infected or died, and the official projections of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of fatalities. Further intensifying the stress was hearing that there was a shortage of personal protective equipment (even masks), a lack of ventilators, and the absence of any medications to fight the overwhelming viral infection. Especially stressed were the front-line physicians and nurses, who heroically transcended their fears to save their patients’ lives. The sight of refrigerated trucks serving as temporary morgues outside hospital doors was chilling. The world became a macabre place where people died in hospitals without any relative to hold their hands or comfort them, and then were buried quickly without any formal funerals due to mandatory social distancing. The inability of families to grieve for their loved ones added another poignant layer of sadness and distress to the survivors who were unable to bid their loved ones goodbye. This was a jarring example of adding insult to injury.

With the protraction of the exceptional changes imposed by the pandemic, the acute stress reaction transmuted into posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on a wide scale. Millions of previously healthy individuals began to succumb to the symptoms of PTSD (irritability, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, insomnia, and bad dreams). The heaviest burden was inflicted on our patients, across all ages, with preexisting psychiatric conditions, who comprise approximately 25% of the population per the classic Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) study.24 These vulnerable patients, whom we see in our clinics and hospitals every day, had a significant exacerbation of their psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, psychosis, binge eating disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol and substance use disorders, child abuse, and intimate partner violence.25,26 The saving grace was the rapid adoption of telepsychiatry, which our psychiatric patients rapidly accepted. Many of them found it more convenient than dressing and driving and parking at the clinic. It also enabled psychiatrists to obtain useful collateral information from family members or partners.

If something good comes from this catastrophic social stress that emotionally hobbled the entire population, it would be the dilution of the stigma of mental illness because everyone has become more empathic due to their personal experience. Optimistically, this may also help expedite true health care parity for psychiatric brain disorders. And perhaps the government may see the need to train more psychiatrists and fund a higher number of residency stipends to all training programs.

Quo vadis COVID-19?

So, looking through the dense fog of the pandemic fatigue, what will 2021 bring us? Will waves of COVID-19 lead to pandemic exhaustion? Will the frayed public mental health care system be able to handle the surge of frayed nerves? Will social distancing intensify the widespread emotional disquietude? Will the children be able to manifest resilience and avoid disabling psychiatric disorders? Will the survivors of COVID-19 infections suffer from post–COVD-19 neuropsychiatric and other medical sequelae? Will efficacious therapies and vaccines emerge to blunt the spread of the virus? Will we all be able to gather in stadiums and arenas to enjoy sporting events, shows, and concerts? Will eating at our favorite restaurants become routine again? Will engaged couples be able to organize well-attended weddings and receptions? Will airplanes and hotels be fully booked again? Importantly, will all children and college students be able to resume their education in person and socialize ad lib? Will we be able to shed our masks and hug each other hello and goodbye? Will scientific journals and social media cover a wide array of topics again as before? Will the number of deaths dwindle to zero, and will we return to worrying mainly about the usual seasonal flu? Will everyone be able to leave home and go to work again?

I hope that the thick dust of this 2020 viral asteroid will settle in 2021, and that “normalcy” is eventually restored to our lives, allowing us to deal with other ongoing stresses such as social unrest and political hyperpartisanship.

1. Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, et al. Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(5):642-649.

2. Zatti C, Rosa V, Barros A, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide attempt: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from the last decade. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:353-358.

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1918 Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html. Accessed November 4, 2020.

5. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

6. Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-33.

7. Joshi KG. Taking care of ourselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):46-47.

8. Frank B, Peterson T, Gupta S, et al. Telepsychiatry: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):16-23.

9. Chahal K. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):31-33.

10. Arbuck D. Changes in patient behavior during COVID-19: what I’ve observed. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):46-47.

11. Joshi KG. Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: understanding the rules. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e12-e14.

12. Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

13. Brooks V. COVID-19’s effects on emergency psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):33-36,38-39.

14. Desarbo JR, DeSarbo L. Anorexia nervosa and COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(8):23-28.

15. Freudenreich O, Kontos N, Querques J. COVID-19 and patients with serious mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):24-27,33-39.

16. Ryznar E. Evaluating patients’ decision-making capacity during COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):34-40.

17. Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

18. Lodhi S, Marett C. Using seclusion to prevent COVID-19 transmission on inpatient psychiatry units. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):37-41,53.

19. Nasrallah HA. COVID-19 and the precipitous dismantlement of societal norms. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):12-14,16-17.

20. Nasrallah HA. The cataclysmic COVID-19 pandemic: THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):7-8,16.

21. Nasrallah HA. During a viral pandemic, anxiety is endemic: the psychiatric aspects of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):e3-e5.

22. Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213-218.

23. Berkwits M, Flanagin A, Bauchner H, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the JAMA Network. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1159-1160.

24. Robins LN, Regier DA, eds. Psychiatric disorders in America. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1991.

25. Meninger KA. Psychosis associated with influenza. I. General data: statistical analysis. JAMA. 1919;72(4):235-241.

26. Simon NM, Saxe GN, Marmar CR. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1493-1494.

1. Baumeister D, Akhtar R, Ciufolini S, et al. Childhood trauma and adulthood inflammation: a meta-analysis of peripheral C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(5):642-649.

2. Zatti C, Rosa V, Barros A, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide attempt: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies from the last decade. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:353-358.

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1918 Pandemic. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html. Accessed November 4, 2020.

5. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

6. Sharma RA, Maheshwari S, Bronsther R. COVID-19 in the era of loneliness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):31-33.

7. Joshi KG. Taking care of ourselves during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):46-47.

8. Frank B, Peterson T, Gupta S, et al. Telepsychiatry: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):16-23.

9. Chahal K. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):31-33.

10. Arbuck D. Changes in patient behavior during COVID-19: what I’ve observed. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):46-47.

11. Joshi KG. Telepsychiatry during COVID-19: understanding the rules. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(6):e12-e14.

12. Komrad MS. Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):29-32,46.

13. Brooks V. COVID-19’s effects on emergency psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):33-36,38-39.

14. Desarbo JR, DeSarbo L. Anorexia nervosa and COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(8):23-28.

15. Freudenreich O, Kontos N, Querques J. COVID-19 and patients with serious mental illness. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):24-27,33-39.

16. Ryznar E. Evaluating patients’ decision-making capacity during COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):34-40.

17. Saeed SA, Hebishi K. The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 studies. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):22-24,28-30,32-35.

18. Lodhi S, Marett C. Using seclusion to prevent COVID-19 transmission on inpatient psychiatry units. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(11):37-41,53.

19. Nasrallah HA. COVID-19 and the precipitous dismantlement of societal norms. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(7):12-14,16-17.

20. Nasrallah HA. The cataclysmic COVID-19 pandemic: THIS CHANGES EVERYTHING! Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):7-8,16.

21. Nasrallah HA. During a viral pandemic, anxiety is endemic: the psychiatric aspects of COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(4):e3-e5.

22. Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213-218.

23. Berkwits M, Flanagin A, Bauchner H, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the JAMA Network. JAMA. 2020;324(12):1159-1160.

24. Robins LN, Regier DA, eds. Psychiatric disorders in America. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1991.

25. Meninger KA. Psychosis associated with influenza. I. General data: statistical analysis. JAMA. 1919;72(4):235-241.

26. Simon NM, Saxe GN, Marmar CR. Mental health disorders related to COVID-19-related deaths. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1493-1494.