User login

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

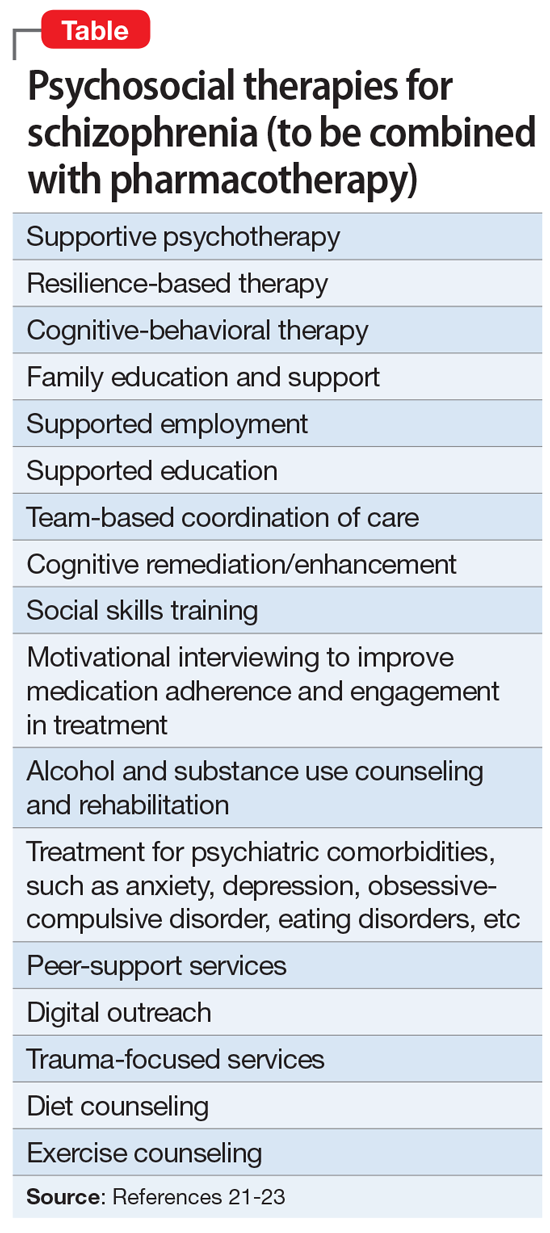

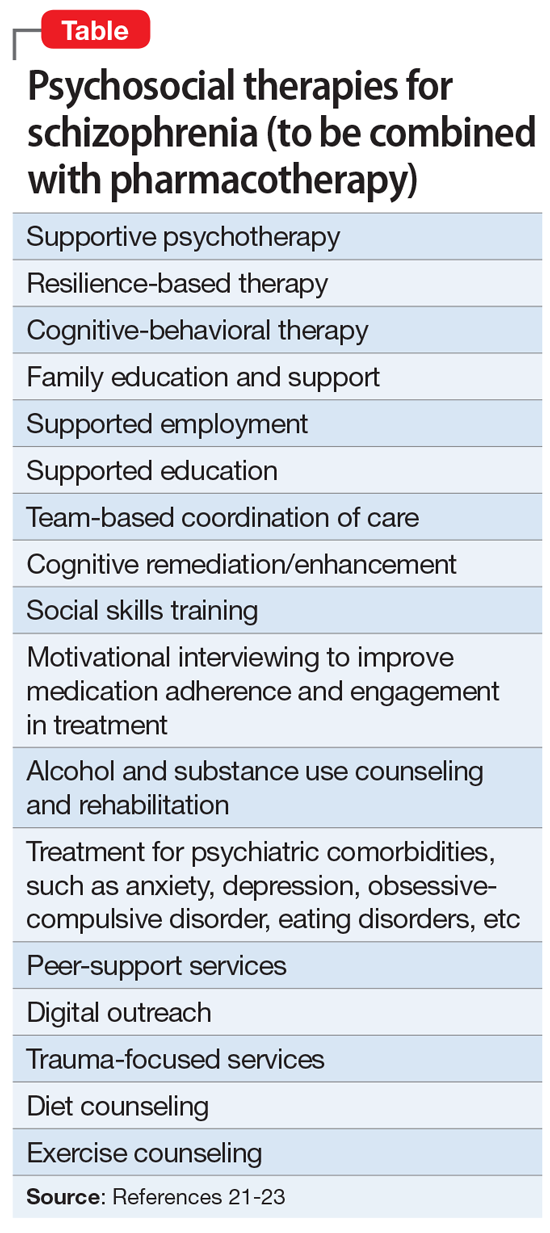

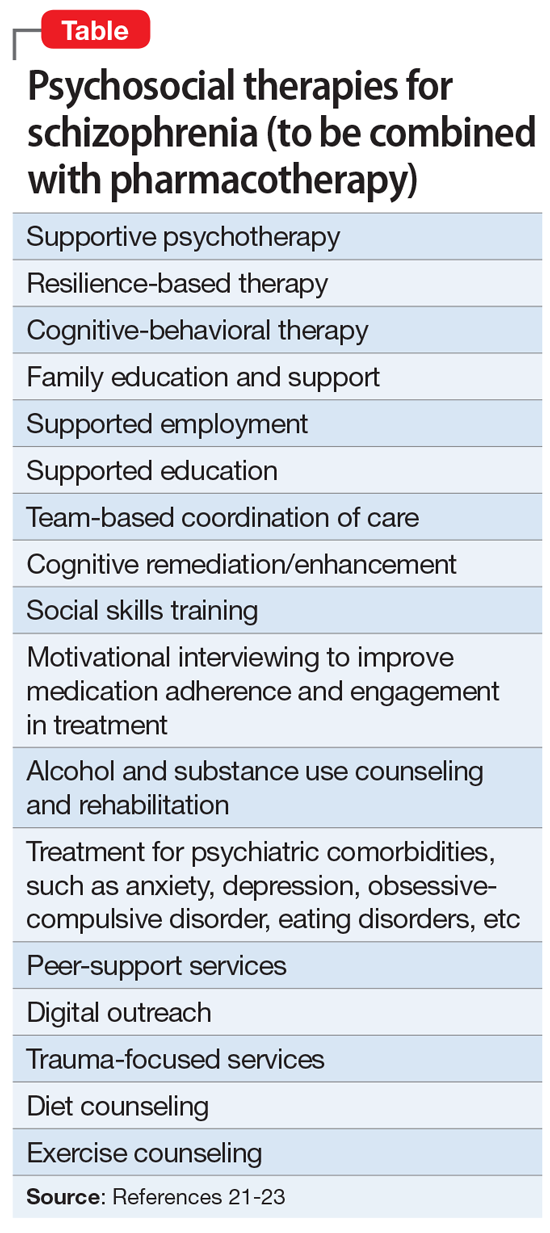

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

1. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

2. Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95.

3. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372.

4. Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057

5. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

6. Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Primary nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):665-663.

7. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

8. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

9. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

10. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic doses for relapse prevention in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in Finland: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):271-279.

11. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):38-45,e3.

12. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

13. Feigenson KA, Kusnecov AW, Silverstein SM. Inflammation and the two-hit hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:72-93.

14. Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):400-409.

15. Lavoie S, Polari AR, Goldstone S, et al. Staging model in psychiatry: review of the evolution of electroencephalography abnormalities in major psychiatric disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(6):1319-1328.

16. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

17. Lin YH, Wu CS, Liu CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in preventing readmission for first-admission schizophrenia patients in national cohorts from 2001 to 2017 in Taiwan. Schizophr Bull. 2022;sbac046. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbac046

18. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

21. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

22. Keshavan MS, Ongur D, Srihari VH. Toward an expanded and personalized approach to coordinated specialty care in early course psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:119-121.

23. Srihari VH, Keshavan MS. Early intervention services for schizophrenia: looking back and looking ahead. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):544-550.

24. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

25. Nasrallah HA. Clozapine is a vastly underutilized, unique agent with multiple applications. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(10):21,24-25.

26. CureSZ Foundation. Clozapine success stories. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://curesz.org/clozapine-success-stories/

27. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

Schizophrenia is arguably the most serious psychiatric brain syndrome. It disables teens and young adults and robs them of their potential and life dreams. It is widely regarded as a hopeless illness.

But it does not have to be. The reason most patients with schizophrenia do not return to their baseline is because obsolete clinical management approaches, a carryover from the last century, continue to be used.

Approximately 20 years ago, psychiatric researchers made a major discovery: psychosis is a neurotoxic state, and each psychotic episode is associated with significant brain damage in both gray and white matter.1 Based on that discovery, a more rational management of schizophrenia has emerged, focused on protecting patients from experiencing psychotic recurrence after the first-episode psychosis (FEP). In the past century, this strategy did not exist because psychiatrists were in a state of scientific ignorance, completely unaware that the malignant component of schizophrenia that leads to disability is psychotic relapses, the primary cause of which is very poor medication adherence after hospital discharge following the FEP.

Based on the emerging scientific evidence, here are 3 essential principles to halt the deterioration and bend the curve of outcomes in schizophrenia:

1. Minimize the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP)

Numerous studies have shown that the longer the DUP, the worse the outcome in schizophrenia.2,3 It is therefore vital to shorten the DUP spanning the emergence of psychotic symptoms at home, prior to the first hospital admission.4 The DUP is often prolonged from weeks to months by a combination of anosognosia by the patient, who fails to recognize how pathological their hallucinations and delusions are, plus the stigma of mental illness, which leads parents to delay bringing their son or daughter for psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Another reason for a prolonged DUP is the legal system’s governing of the initiation of antipsychotic medications for an acutely psychotic patient who does not believe he/she is sick, and who adamantly refuses to receive medications. Laws passed decades ago have not kept up with scientific advances about brain damage during the DUP. Instead of delegating the rapid administration of an antipsychotic medication to the psychiatric physician who evaluated and diagnosed a patient with acute psychosis, the legal system further prolongs the DUP by requiring the psychiatrist to go to court and have a judge order the administration of antipsychotic medications. Such a legal requirement that delays urgently needed treatment has never been imposed on neurologists when administering medication to an obtunded stroke patient. Yet psychosis damages brain tissue and must be treated as urgently as stroke.5

Perhaps the most common reason for a long DUP is the recurrent relapses of psychosis, almost always caused by the high nonadherence rate among patients with schizophrenia due to multiple factors related to the illness itself.6 Ensuring uninterrupted delivery of an antipsychotic to a patient’s brain is as important to maintaining remission in schizophrenia as uninterrupted insulin treatment is for an individual with diabetes. The only way to guarantee ongoing daily pharmacotherapy in schizophrenia and avoid a longer DUP and more brain damage is to use long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications, which are infrequently used despite making eminent sense to protect patients from the tragic consequences of psychotic relapse.7

Continue to: Start very early use of LAIs

2. Start very early use of LAIs

There is no doubt that switching from an oral to an LAI antipsychotic immediately after hospital discharge for the FEP is the single most important medical decision psychiatrists can make for patients with schizophrenia.8 This is because disability in schizophrenia begins after the second episode, not the first.9-11 Therefore, psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists,12 who strive to prevent a second destructive myocardial infarction. Regrettably, 99.9% of psychiatric practitioners never start an LAI after the FEP, and usually wait until the patient experiences multiple relapses, after extensive gray matter atrophy and white matter disintegration have occurred due to the neuroinflammation and oxidative stress (free radicals) that occur with every psychotic episode.13,14 This clearly does not make clinical sense, but remains the standard current practice.

In oncology, chemotherapy is far more effective in Stage 1 cancer, immediately after the diagnosis is made, rather than in Stage 4, when the prognosis is very poor. Similarly, LAIs are best used in Stage 1 schizophrenia, which is the first episode (schizophrenia researchers now regard the illness as having stages).15 Unfortunately, it is now rare for patients with schizophrenia to be switched to LAI pharmacotherapy right after recovery from the FEP. Instead, LAIs are more commonly used in Stage 3 or Stage 4, when the brains of patients with chronic schizophrenia have been already structurally damaged, and functional disability had set in. Bending the cure of outcome in schizophrenia is only possible when LAIs are used very early to prevent the second episode.

The prevention of relapse by using LAIs in FEP is truly remarkable. Subotnik et al16 reported that only 5% of FEP patients who received an LAI antipsychotic relapsed, compared to 33% of those who received an oral formulation of the same antipsychotic (a 650% difference). It is frankly inexplicable why psychiatrists do not exploit the relapse-preventing properties of LAIs at the time of discharge after the FEP, and instead continue to perpetuate the use of prescribing oral tablets to patients who are incapable of full adherence and doomed to “self-destruct.” This was the practice model in the previous century, when there was total ignorance about the brain-damaging effects of psychosis, and no sense of urgency about preventing psychotic relapses and DUP. Psychiatrists regarded LAIs as a last resort instead of a life-saving first resort.

In addition to relapse prevention,17 the benefits of second-generation LAIs include neuroprotection18 and lower all-cause mortality,19 a remarkable triad of benefits for patients with schizophrenia.20

3. Implement comprehensive psychosocial treatment

Most patients with schizophrenia do not have access to the array of psychosocial treatments that have been shown to be vital for rehabilitation following the FEP, just as physical rehabilitation is indispensable after the first stroke. Studies such as RAISE,21 which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, have demonstrated the value of psychosocial therapies (Table21-23). Collaborative care with primary care physicians is also essential due to the high prevalence of metabolic disorders (obesity, diabetics, dyslipidemia, hypertension), which tend to be undertreated in patients with schizophrenia.24

Finally, when patients continue to experience delusions and hallucinations despite full adherence (with LAIs), clozapine must be used. Like LAIs, clozapine is woefully underutilized25 despite having been shown to restore mental health and full recovery to many (but not all) patients written off as hopeless due to persistent and refractory psychotic symptoms.26

If clinicians who treat schizophrenia implement these 3 steps in their FEP patients, they will be gratified to witness a more benign trajectory of schizophrenia, which I have personally seen. The curve can indeed be bent in favor of better outcomes. By using the 3 evidence-based steps described here, clinicians will realize that schizophrenia does not have to carry the label of “the worst disease affecting mankind,” as an editorial in a top-tier journal pessimistically stated over 3 decades ago.27

1. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

2. Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95.

3. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372.

4. Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057

5. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

6. Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Primary nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):665-663.

7. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

8. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

9. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

10. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic doses for relapse prevention in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in Finland: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):271-279.

11. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):38-45,e3.

12. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

13. Feigenson KA, Kusnecov AW, Silverstein SM. Inflammation and the two-hit hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:72-93.

14. Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):400-409.

15. Lavoie S, Polari AR, Goldstone S, et al. Staging model in psychiatry: review of the evolution of electroencephalography abnormalities in major psychiatric disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(6):1319-1328.

16. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

17. Lin YH, Wu CS, Liu CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in preventing readmission for first-admission schizophrenia patients in national cohorts from 2001 to 2017 in Taiwan. Schizophr Bull. 2022;sbac046. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbac046

18. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

21. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

22. Keshavan MS, Ongur D, Srihari VH. Toward an expanded and personalized approach to coordinated specialty care in early course psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:119-121.

23. Srihari VH, Keshavan MS. Early intervention services for schizophrenia: looking back and looking ahead. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):544-550.

24. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

25. Nasrallah HA. Clozapine is a vastly underutilized, unique agent with multiple applications. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(10):21,24-25.

26. CureSZ Foundation. Clozapine success stories. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://curesz.org/clozapine-success-stories/

27. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

1. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

2. Howes OD, Whitehurst T, Shatalina E, et al. The clinical significance of duration of untreated psychosis: an umbrella review and random-effects meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):75-95.

3. Oliver D, Davies C, Crossland G, et al. Can we reduce the duration of untreated psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled interventional studies. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1362-1372.

4. Srihari VH, Ferrara M, Li F, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) in a US community: a quasi-experimental trial. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3(1):sgab057. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgab057

5. Nasrallah HA, Roque A. FAST and RAPID: acronyms to prevent brain damage in stroke and psychosis. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):6-8.

6. Lieslehto J, Tiihonen J, Lähteenvuo M, et al. Primary nonadherence to antipsychotic treatment among persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):665-663.

7. Nasrallah HA. 10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(5):9-12.

8. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

9. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

10. Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Correll CU, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic doses for relapse prevention in patients with first-episode schizophrenia in Finland: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(4):271-279.

11. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):38-45,e3.

12. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

13. Feigenson KA, Kusnecov AW, Silverstein SM. Inflammation and the two-hit hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;38:72-93.

14. Flatow J, Buckley P, Miller BJ. Meta-analysis of oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):400-409.

15. Lavoie S, Polari AR, Goldstone S, et al. Staging model in psychiatry: review of the evolution of electroencephalography abnormalities in major psychiatric disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(6):1319-1328.

16. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

17. Lin YH, Wu CS, Liu CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in preventing readmission for first-admission schizophrenia patients in national cohorts from 2001 to 2017 in Taiwan. Schizophr Bull. 2022;sbac046. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbac046

18. Chen AT, Nasrallah HA. Neuroprotective effects of the second generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:1-7.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Nasrallah HA. Triple advantages of injectable long acting second generation antipsychotics: relapse prevention, neuroprotection, and lower mortality. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:69-70.

21. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

22. Keshavan MS, Ongur D, Srihari VH. Toward an expanded and personalized approach to coordinated specialty care in early course psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2022;241:119-121.

23. Srihari VH, Keshavan MS. Early intervention services for schizophrenia: looking back and looking ahead. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):544-550.

24. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

25. Nasrallah HA. Clozapine is a vastly underutilized, unique agent with multiple applications. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(10):21,24-25.

26. CureSZ Foundation. Clozapine success stories. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://curesz.org/clozapine-success-stories/

27. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.