User login

Among the ever increasing number of post-9/11 veterans pursuing higher education are many who carry psychological injuries, which include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of these mental health issues can create acquired learning disabilities involving impairments in memory, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking.1-4 Such learning disabilities can prevent a soldier from successfully transitioning to student-veteran.

Academic reasonable accommodations for veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can strategically enhance student-veteran role integration. Similar to reasonable accommodations for physical diagnoses, academic accommodations for psychiatric conditions enhance qualifying student-veterans’ abilities to successfully pursue higher education by enabling them to compensate for deficits in memory, recall, concentration, and abstract thinking. Such assistance for veterans with disabilities has been advocated in order to promote academic progression and student empowerment.5,6 Although academic accommodations enable veterans to compensate for learning disabilities, such interventions are not routinely requested for a variety of reasons. There are several key factors influencing veterans’ decisions to request such accommodations.

To promote a healthy transition to the student-veteran role, health care providers (HCPs) should initiate conversations about potential acquired learning disabilities with post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses who are or will become students. Unfortunately, the medical literature includes little information on this topic or on how to have these conversations. To date, there is no suggested theoretical framework for guiding such discussions.

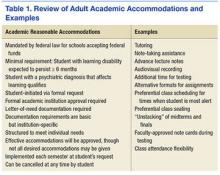

As a foundation for such discussion, Part 1 of this article explained the implications of psychiatric diagnoses and other common factors that can significantly impede adult learning among post-9/11 veterans who are separated from service.7 Part 1 also addressed the fundamentals of academic reasonable accommodations, which are outlined in Table 1.

Through use of a theoretical model, part 2 of this study defines key factors influencing post-9/11 veterans’ decision to request academic reasonable accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses. It also provides practical advice for facilitating clinical conversations at each stage of the model to promote the acceptance of academic reasonable accommodations among eligible post-9/11 veterans.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model (HBM) can be adopted to understand the steps of veterans’ decision-making processes involving reasonable accommodations. The model outlines determinants of human behavior that influence the potential health care decision to deliberately mitigate harm from a perceived health threat.8,9 The 6 primary components are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.8,9 The HBM previously has been applied to a diverse range of health behaviors involving prevention, medical regimen adherence, and utilization of health care services.10 Its application to learning impairment and academic reasonable accommodations is outlined in Table 2.

When the HBM framework is applied to academic accommodations, the perceived health threat is acquired learning disability. The desired health care decision is the act of requesting academic reasonable accommodations. The targeted population at risk is the post-9/11 veteran cohort with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses who are enrolled in, or who are considering, postsecondary education.

The initial perceived susceptibility step determines the degree to which these veterans judge themselves as being at risk for learning impairment because of psychiatric diagnoses. During this step, it is imperative that HCPs educate veterans on how mental health conditions can alter adult learning styles. Clinicians should describe the negative effects of psychiatric symptoms on memory, concentration, focus, attention, and abstract thinking. Insight is developed in this step as veterans recognize that their academic endeavors potentially could be affected by underlying mental health symptoms.

Perceived Severity

Recognition of the perceived severity of impaired learning is the next step in HBM. Veterans will need to self-evaluate their actual or potential academic performance based on their current state of memory, concentration, focus, and attention. Although many veterans might determine that the impact is transient or minimal, a significant number of veterans will observe that their learning abilities are greatly affected. If veterans identify with loss of those skills since the onset of serious mental health issues, there should be further discussion regarding the existence of academic accommodations that address any learning impairment expected to last longer than 6 months.

As discussed in part 1, mental health diagnoses involving mood, though possessing individually distinct diagnostic criteria, create potentially similar global learning impairments in terms of decreased memory, poor concentration, and slowed executive functioning.1-4 Insight into the impact of any acquired learning disability from these mental health conditions and/or associated pharmacologic treatment can be encouraged if the clinician and client jointly review the client’s self-described premorbid learning style and compare it with the client’s current functioning in day-to-day activities requiring memory, concentration, and decision making. A clinician can use a gentle emphasis on the incongruities between premorbid learning ability and present-day impairments as a springboard for discussion about ways to compensate for learning impairments.

Additional insight can be elicited by providing practical examples of how other factors can accentuate the learning difficulties caused by serious or persistent psychiatric symptoms. By discussing these issues, clinicians can provide veterans with a more realistic understanding of potential obstacles in the postsecondary setting and the need for a strategic plan to address such challenges. For example, if a veteran takes prescription medications to manage underlying psychiatric conditions, a discussion regarding pertinent pharmacologic adverse effects (AEs) can highlight how academic performance might be affected. As outlined in part 1, fatigue, drowsiness, restlessness, mental grogginess, and insomnia are just a few medication AEs that may impair academic performance by negatively affecting memory, concentration, and executive functioning.

There are multiple circumstances that can increase the degree to which psychiatric symptoms impede recall, memory, insight, judgment, concentration, attention, organization, and abstract thinking. Impaired memory, poor concentration, irritability, and decreased attention can occur in the normal postmilitary transition period or as residual effects from mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Multiple role responsibilities, such as being a spouse and parent, also can present significant mental distractions from academic endeavors. A physical impairment, such as tinnitus, hearing loss, or chronic pain, can impede classroom participation.

At this juncture, HCPs also should identify the academic consequences of impaired learning. Knowing these consequences will help veterans decide whether a course of action is needed to compensate for any learning disability that may be present. Inability to finish timed tests, difficulty taking notes, and inefficient studying are some of the more serious potential sequelae. Feared long-term consequences include a lack of progress through the required course load and, ultimately, failing courses.

A basic explanation of the potential financial effects of poor academic achievement provides another practical method for clinicians to outline negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. The student’s sole income for basic necessities is often the post-9/11 GI Bill, which pays for up to 36 months of education benefits and includes a living allowance and book stipend.

Unfortunately, given their financial dependence on the GI Bill, many veterans who withdraw from classes due to academic difficulties face economic uncertainty. If their withdrawal is not approved by the GI Bill program, these veterans must pay back all the money granted during the semester. Veterans who remain in school despite receiving failing marks cannot recover money spent on failed courses. This potentially results in veterans exceeding their entire GI Bill allotment before completing course requirements for their desired certificate or degree. Many veterans logically conclude that the potential financial devastation is a sufficiently severe consequence of impaired learning ability, and those who believe they have significantly impaired learning ability may become more motivated to reduce any risk of academic failure by pursuing academic accommodations.

In tandem with reviewing the potential severity of the problem, clinicians always should emphasize the availability of academic accommodations to circumvent the negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. Veterans who experience academic difficulties but are unaware of academic interventions may decide to forgo postsecondary education. By understanding basic details about accommodations, veterans can make the informed decision to pursue these interventions as part of a plan for academic success.

Perceived Benefits

Although identifying perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are necessary for veterans to consider academic reasonable accommodation use, eligible veterans still may not understand how these accommodations can apply to their situation. In the next step of HBM, veterans must view formal academic accommodations as a desirable solution to mitigate the effects of impaired learning ability. Veterans must appreciate the perceived benefits of such requests before they elect to pursue them.

At this point, HCPs should provide examples of academic accommodations to illustrate the simplicity and ease of such interventions. Tutoring, note-taking assistance, and providing additional time for testing are examples of a few types of accommodations featuring advantages that should be readily apparent to veterans returning to school. These measures not only lessen the likelihood of struggling academically, but also afford an opportunity to excel. By painting accommodations as a powerful method of self-advocacy, HCPs can inform veterans that accommodations enable a measure of control within the academic setting and assist with planning.

Perceived Barriers

Although identifying perceived benefits may be persuasive, discerning perceived barriers is an important HBM step that influences whether veterans will seek academic accommodations. Fortunately, many of the common barriers to accommodation requests are simply misconceptions that clinicians can address easily. For example, some veterans misconstrue reasonable accommodations as giving them an unfair advantage, which they find offensive to their personal integrity and pride. Clinicians should point out to these veterans that accommodations address deficits in learning abilities and merely level the academic playing field so the student-veteran is on par with those students without such impairments. The core work needed to pass the class remains unchanged by such accommodations.

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

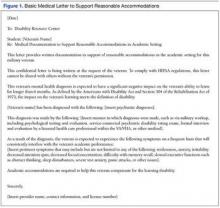

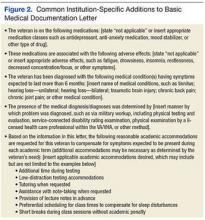

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from [email protected]).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.

Conclusion

Formal academic accommodations are viable tools for cultivating academic success among student-veterans with significant psychiatric conditions. The adoption of such interventions requires understanding post-9/11 veterans’ motivation and concerns about formal academic accommodation requests. Application of the HBM can guide clinicians in their discussions with post-9/11 veterans. By understanding the veterans’ perspectives on the subject, HCPs can directly address the factors influencing the decision to seek academic accommodations.

Ensuring successful transition to the student-veteran role is of prime importance for veterans who bear emotional scars from military service. To this author’s knowledge, no structured educational programs currently exist that inform either post-9/11 veterans or their HCPs about pertinent aspects of academic accommodations for student-veterans with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses that impede learning. Future endeavors need to include development of programs to inform veterans and providers about this important topic. Such programs should not only promote the dissemination of general information, but also explore specific ways to tailor accommodations to the cognitive needs of each veteran.

1. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

2. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

3. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

4. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

5. Branker C. Deserving design: the new generation of student veterans. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):59-66.

6. Burnett SE, Segoria J. Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: it takes a community. J Postsecond Educ and Disabil. 2009;22(1):53-58.

7. Mitchell K. Understanding academic reasonable accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses—part 1, the foundation. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):33-39.

8. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183.

9. Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005.

10. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47.

11. Salzer MS, Wick LC, Rogers JA. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370-375.

12. Shackelford AL. Documenting the needs of student veterans with disabilities: intersection roadblocks, solutions, and legal realities. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):36-42.

13. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522-541.

14. Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142.

15. Palmer C, Roessler RT. Requesting classroom accommodations: self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2000;66(3):38-43.

Among the ever increasing number of post-9/11 veterans pursuing higher education are many who carry psychological injuries, which include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of these mental health issues can create acquired learning disabilities involving impairments in memory, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking.1-4 Such learning disabilities can prevent a soldier from successfully transitioning to student-veteran.

Academic reasonable accommodations for veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can strategically enhance student-veteran role integration. Similar to reasonable accommodations for physical diagnoses, academic accommodations for psychiatric conditions enhance qualifying student-veterans’ abilities to successfully pursue higher education by enabling them to compensate for deficits in memory, recall, concentration, and abstract thinking. Such assistance for veterans with disabilities has been advocated in order to promote academic progression and student empowerment.5,6 Although academic accommodations enable veterans to compensate for learning disabilities, such interventions are not routinely requested for a variety of reasons. There are several key factors influencing veterans’ decisions to request such accommodations.

To promote a healthy transition to the student-veteran role, health care providers (HCPs) should initiate conversations about potential acquired learning disabilities with post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses who are or will become students. Unfortunately, the medical literature includes little information on this topic or on how to have these conversations. To date, there is no suggested theoretical framework for guiding such discussions.

As a foundation for such discussion, Part 1 of this article explained the implications of psychiatric diagnoses and other common factors that can significantly impede adult learning among post-9/11 veterans who are separated from service.7 Part 1 also addressed the fundamentals of academic reasonable accommodations, which are outlined in Table 1.

Through use of a theoretical model, part 2 of this study defines key factors influencing post-9/11 veterans’ decision to request academic reasonable accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses. It also provides practical advice for facilitating clinical conversations at each stage of the model to promote the acceptance of academic reasonable accommodations among eligible post-9/11 veterans.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model (HBM) can be adopted to understand the steps of veterans’ decision-making processes involving reasonable accommodations. The model outlines determinants of human behavior that influence the potential health care decision to deliberately mitigate harm from a perceived health threat.8,9 The 6 primary components are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.8,9 The HBM previously has been applied to a diverse range of health behaviors involving prevention, medical regimen adherence, and utilization of health care services.10 Its application to learning impairment and academic reasonable accommodations is outlined in Table 2.

When the HBM framework is applied to academic accommodations, the perceived health threat is acquired learning disability. The desired health care decision is the act of requesting academic reasonable accommodations. The targeted population at risk is the post-9/11 veteran cohort with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses who are enrolled in, or who are considering, postsecondary education.

The initial perceived susceptibility step determines the degree to which these veterans judge themselves as being at risk for learning impairment because of psychiatric diagnoses. During this step, it is imperative that HCPs educate veterans on how mental health conditions can alter adult learning styles. Clinicians should describe the negative effects of psychiatric symptoms on memory, concentration, focus, attention, and abstract thinking. Insight is developed in this step as veterans recognize that their academic endeavors potentially could be affected by underlying mental health symptoms.

Perceived Severity

Recognition of the perceived severity of impaired learning is the next step in HBM. Veterans will need to self-evaluate their actual or potential academic performance based on their current state of memory, concentration, focus, and attention. Although many veterans might determine that the impact is transient or minimal, a significant number of veterans will observe that their learning abilities are greatly affected. If veterans identify with loss of those skills since the onset of serious mental health issues, there should be further discussion regarding the existence of academic accommodations that address any learning impairment expected to last longer than 6 months.

As discussed in part 1, mental health diagnoses involving mood, though possessing individually distinct diagnostic criteria, create potentially similar global learning impairments in terms of decreased memory, poor concentration, and slowed executive functioning.1-4 Insight into the impact of any acquired learning disability from these mental health conditions and/or associated pharmacologic treatment can be encouraged if the clinician and client jointly review the client’s self-described premorbid learning style and compare it with the client’s current functioning in day-to-day activities requiring memory, concentration, and decision making. A clinician can use a gentle emphasis on the incongruities between premorbid learning ability and present-day impairments as a springboard for discussion about ways to compensate for learning impairments.

Additional insight can be elicited by providing practical examples of how other factors can accentuate the learning difficulties caused by serious or persistent psychiatric symptoms. By discussing these issues, clinicians can provide veterans with a more realistic understanding of potential obstacles in the postsecondary setting and the need for a strategic plan to address such challenges. For example, if a veteran takes prescription medications to manage underlying psychiatric conditions, a discussion regarding pertinent pharmacologic adverse effects (AEs) can highlight how academic performance might be affected. As outlined in part 1, fatigue, drowsiness, restlessness, mental grogginess, and insomnia are just a few medication AEs that may impair academic performance by negatively affecting memory, concentration, and executive functioning.

There are multiple circumstances that can increase the degree to which psychiatric symptoms impede recall, memory, insight, judgment, concentration, attention, organization, and abstract thinking. Impaired memory, poor concentration, irritability, and decreased attention can occur in the normal postmilitary transition period or as residual effects from mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Multiple role responsibilities, such as being a spouse and parent, also can present significant mental distractions from academic endeavors. A physical impairment, such as tinnitus, hearing loss, or chronic pain, can impede classroom participation.

At this juncture, HCPs also should identify the academic consequences of impaired learning. Knowing these consequences will help veterans decide whether a course of action is needed to compensate for any learning disability that may be present. Inability to finish timed tests, difficulty taking notes, and inefficient studying are some of the more serious potential sequelae. Feared long-term consequences include a lack of progress through the required course load and, ultimately, failing courses.

A basic explanation of the potential financial effects of poor academic achievement provides another practical method for clinicians to outline negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. The student’s sole income for basic necessities is often the post-9/11 GI Bill, which pays for up to 36 months of education benefits and includes a living allowance and book stipend.

Unfortunately, given their financial dependence on the GI Bill, many veterans who withdraw from classes due to academic difficulties face economic uncertainty. If their withdrawal is not approved by the GI Bill program, these veterans must pay back all the money granted during the semester. Veterans who remain in school despite receiving failing marks cannot recover money spent on failed courses. This potentially results in veterans exceeding their entire GI Bill allotment before completing course requirements for their desired certificate or degree. Many veterans logically conclude that the potential financial devastation is a sufficiently severe consequence of impaired learning ability, and those who believe they have significantly impaired learning ability may become more motivated to reduce any risk of academic failure by pursuing academic accommodations.

In tandem with reviewing the potential severity of the problem, clinicians always should emphasize the availability of academic accommodations to circumvent the negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. Veterans who experience academic difficulties but are unaware of academic interventions may decide to forgo postsecondary education. By understanding basic details about accommodations, veterans can make the informed decision to pursue these interventions as part of a plan for academic success.

Perceived Benefits

Although identifying perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are necessary for veterans to consider academic reasonable accommodation use, eligible veterans still may not understand how these accommodations can apply to their situation. In the next step of HBM, veterans must view formal academic accommodations as a desirable solution to mitigate the effects of impaired learning ability. Veterans must appreciate the perceived benefits of such requests before they elect to pursue them.

At this point, HCPs should provide examples of academic accommodations to illustrate the simplicity and ease of such interventions. Tutoring, note-taking assistance, and providing additional time for testing are examples of a few types of accommodations featuring advantages that should be readily apparent to veterans returning to school. These measures not only lessen the likelihood of struggling academically, but also afford an opportunity to excel. By painting accommodations as a powerful method of self-advocacy, HCPs can inform veterans that accommodations enable a measure of control within the academic setting and assist with planning.

Perceived Barriers

Although identifying perceived benefits may be persuasive, discerning perceived barriers is an important HBM step that influences whether veterans will seek academic accommodations. Fortunately, many of the common barriers to accommodation requests are simply misconceptions that clinicians can address easily. For example, some veterans misconstrue reasonable accommodations as giving them an unfair advantage, which they find offensive to their personal integrity and pride. Clinicians should point out to these veterans that accommodations address deficits in learning abilities and merely level the academic playing field so the student-veteran is on par with those students without such impairments. The core work needed to pass the class remains unchanged by such accommodations.

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from [email protected]).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.

Conclusion

Formal academic accommodations are viable tools for cultivating academic success among student-veterans with significant psychiatric conditions. The adoption of such interventions requires understanding post-9/11 veterans’ motivation and concerns about formal academic accommodation requests. Application of the HBM can guide clinicians in their discussions with post-9/11 veterans. By understanding the veterans’ perspectives on the subject, HCPs can directly address the factors influencing the decision to seek academic accommodations.

Ensuring successful transition to the student-veteran role is of prime importance for veterans who bear emotional scars from military service. To this author’s knowledge, no structured educational programs currently exist that inform either post-9/11 veterans or their HCPs about pertinent aspects of academic accommodations for student-veterans with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses that impede learning. Future endeavors need to include development of programs to inform veterans and providers about this important topic. Such programs should not only promote the dissemination of general information, but also explore specific ways to tailor accommodations to the cognitive needs of each veteran.

Among the ever increasing number of post-9/11 veterans pursuing higher education are many who carry psychological injuries, which include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of these mental health issues can create acquired learning disabilities involving impairments in memory, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking.1-4 Such learning disabilities can prevent a soldier from successfully transitioning to student-veteran.

Academic reasonable accommodations for veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can strategically enhance student-veteran role integration. Similar to reasonable accommodations for physical diagnoses, academic accommodations for psychiatric conditions enhance qualifying student-veterans’ abilities to successfully pursue higher education by enabling them to compensate for deficits in memory, recall, concentration, and abstract thinking. Such assistance for veterans with disabilities has been advocated in order to promote academic progression and student empowerment.5,6 Although academic accommodations enable veterans to compensate for learning disabilities, such interventions are not routinely requested for a variety of reasons. There are several key factors influencing veterans’ decisions to request such accommodations.

To promote a healthy transition to the student-veteran role, health care providers (HCPs) should initiate conversations about potential acquired learning disabilities with post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses who are or will become students. Unfortunately, the medical literature includes little information on this topic or on how to have these conversations. To date, there is no suggested theoretical framework for guiding such discussions.

As a foundation for such discussion, Part 1 of this article explained the implications of psychiatric diagnoses and other common factors that can significantly impede adult learning among post-9/11 veterans who are separated from service.7 Part 1 also addressed the fundamentals of academic reasonable accommodations, which are outlined in Table 1.

Through use of a theoretical model, part 2 of this study defines key factors influencing post-9/11 veterans’ decision to request academic reasonable accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses. It also provides practical advice for facilitating clinical conversations at each stage of the model to promote the acceptance of academic reasonable accommodations among eligible post-9/11 veterans.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model (HBM) can be adopted to understand the steps of veterans’ decision-making processes involving reasonable accommodations. The model outlines determinants of human behavior that influence the potential health care decision to deliberately mitigate harm from a perceived health threat.8,9 The 6 primary components are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.8,9 The HBM previously has been applied to a diverse range of health behaviors involving prevention, medical regimen adherence, and utilization of health care services.10 Its application to learning impairment and academic reasonable accommodations is outlined in Table 2.

When the HBM framework is applied to academic accommodations, the perceived health threat is acquired learning disability. The desired health care decision is the act of requesting academic reasonable accommodations. The targeted population at risk is the post-9/11 veteran cohort with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses who are enrolled in, or who are considering, postsecondary education.

The initial perceived susceptibility step determines the degree to which these veterans judge themselves as being at risk for learning impairment because of psychiatric diagnoses. During this step, it is imperative that HCPs educate veterans on how mental health conditions can alter adult learning styles. Clinicians should describe the negative effects of psychiatric symptoms on memory, concentration, focus, attention, and abstract thinking. Insight is developed in this step as veterans recognize that their academic endeavors potentially could be affected by underlying mental health symptoms.

Perceived Severity

Recognition of the perceived severity of impaired learning is the next step in HBM. Veterans will need to self-evaluate their actual or potential academic performance based on their current state of memory, concentration, focus, and attention. Although many veterans might determine that the impact is transient or minimal, a significant number of veterans will observe that their learning abilities are greatly affected. If veterans identify with loss of those skills since the onset of serious mental health issues, there should be further discussion regarding the existence of academic accommodations that address any learning impairment expected to last longer than 6 months.

As discussed in part 1, mental health diagnoses involving mood, though possessing individually distinct diagnostic criteria, create potentially similar global learning impairments in terms of decreased memory, poor concentration, and slowed executive functioning.1-4 Insight into the impact of any acquired learning disability from these mental health conditions and/or associated pharmacologic treatment can be encouraged if the clinician and client jointly review the client’s self-described premorbid learning style and compare it with the client’s current functioning in day-to-day activities requiring memory, concentration, and decision making. A clinician can use a gentle emphasis on the incongruities between premorbid learning ability and present-day impairments as a springboard for discussion about ways to compensate for learning impairments.

Additional insight can be elicited by providing practical examples of how other factors can accentuate the learning difficulties caused by serious or persistent psychiatric symptoms. By discussing these issues, clinicians can provide veterans with a more realistic understanding of potential obstacles in the postsecondary setting and the need for a strategic plan to address such challenges. For example, if a veteran takes prescription medications to manage underlying psychiatric conditions, a discussion regarding pertinent pharmacologic adverse effects (AEs) can highlight how academic performance might be affected. As outlined in part 1, fatigue, drowsiness, restlessness, mental grogginess, and insomnia are just a few medication AEs that may impair academic performance by negatively affecting memory, concentration, and executive functioning.

There are multiple circumstances that can increase the degree to which psychiatric symptoms impede recall, memory, insight, judgment, concentration, attention, organization, and abstract thinking. Impaired memory, poor concentration, irritability, and decreased attention can occur in the normal postmilitary transition period or as residual effects from mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Multiple role responsibilities, such as being a spouse and parent, also can present significant mental distractions from academic endeavors. A physical impairment, such as tinnitus, hearing loss, or chronic pain, can impede classroom participation.

At this juncture, HCPs also should identify the academic consequences of impaired learning. Knowing these consequences will help veterans decide whether a course of action is needed to compensate for any learning disability that may be present. Inability to finish timed tests, difficulty taking notes, and inefficient studying are some of the more serious potential sequelae. Feared long-term consequences include a lack of progress through the required course load and, ultimately, failing courses.

A basic explanation of the potential financial effects of poor academic achievement provides another practical method for clinicians to outline negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. The student’s sole income for basic necessities is often the post-9/11 GI Bill, which pays for up to 36 months of education benefits and includes a living allowance and book stipend.

Unfortunately, given their financial dependence on the GI Bill, many veterans who withdraw from classes due to academic difficulties face economic uncertainty. If their withdrawal is not approved by the GI Bill program, these veterans must pay back all the money granted during the semester. Veterans who remain in school despite receiving failing marks cannot recover money spent on failed courses. This potentially results in veterans exceeding their entire GI Bill allotment before completing course requirements for their desired certificate or degree. Many veterans logically conclude that the potential financial devastation is a sufficiently severe consequence of impaired learning ability, and those who believe they have significantly impaired learning ability may become more motivated to reduce any risk of academic failure by pursuing academic accommodations.

In tandem with reviewing the potential severity of the problem, clinicians always should emphasize the availability of academic accommodations to circumvent the negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. Veterans who experience academic difficulties but are unaware of academic interventions may decide to forgo postsecondary education. By understanding basic details about accommodations, veterans can make the informed decision to pursue these interventions as part of a plan for academic success.

Perceived Benefits

Although identifying perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are necessary for veterans to consider academic reasonable accommodation use, eligible veterans still may not understand how these accommodations can apply to their situation. In the next step of HBM, veterans must view formal academic accommodations as a desirable solution to mitigate the effects of impaired learning ability. Veterans must appreciate the perceived benefits of such requests before they elect to pursue them.

At this point, HCPs should provide examples of academic accommodations to illustrate the simplicity and ease of such interventions. Tutoring, note-taking assistance, and providing additional time for testing are examples of a few types of accommodations featuring advantages that should be readily apparent to veterans returning to school. These measures not only lessen the likelihood of struggling academically, but also afford an opportunity to excel. By painting accommodations as a powerful method of self-advocacy, HCPs can inform veterans that accommodations enable a measure of control within the academic setting and assist with planning.

Perceived Barriers

Although identifying perceived benefits may be persuasive, discerning perceived barriers is an important HBM step that influences whether veterans will seek academic accommodations. Fortunately, many of the common barriers to accommodation requests are simply misconceptions that clinicians can address easily. For example, some veterans misconstrue reasonable accommodations as giving them an unfair advantage, which they find offensive to their personal integrity and pride. Clinicians should point out to these veterans that accommodations address deficits in learning abilities and merely level the academic playing field so the student-veteran is on par with those students without such impairments. The core work needed to pass the class remains unchanged by such accommodations.

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from [email protected]).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.

Conclusion

Formal academic accommodations are viable tools for cultivating academic success among student-veterans with significant psychiatric conditions. The adoption of such interventions requires understanding post-9/11 veterans’ motivation and concerns about formal academic accommodation requests. Application of the HBM can guide clinicians in their discussions with post-9/11 veterans. By understanding the veterans’ perspectives on the subject, HCPs can directly address the factors influencing the decision to seek academic accommodations.

Ensuring successful transition to the student-veteran role is of prime importance for veterans who bear emotional scars from military service. To this author’s knowledge, no structured educational programs currently exist that inform either post-9/11 veterans or their HCPs about pertinent aspects of academic accommodations for student-veterans with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses that impede learning. Future endeavors need to include development of programs to inform veterans and providers about this important topic. Such programs should not only promote the dissemination of general information, but also explore specific ways to tailor accommodations to the cognitive needs of each veteran.

1. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

2. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

3. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

4. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

5. Branker C. Deserving design: the new generation of student veterans. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):59-66.

6. Burnett SE, Segoria J. Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: it takes a community. J Postsecond Educ and Disabil. 2009;22(1):53-58.

7. Mitchell K. Understanding academic reasonable accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses—part 1, the foundation. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):33-39.

8. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183.

9. Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005.

10. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47.

11. Salzer MS, Wick LC, Rogers JA. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370-375.

12. Shackelford AL. Documenting the needs of student veterans with disabilities: intersection roadblocks, solutions, and legal realities. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):36-42.

13. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522-541.

14. Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142.

15. Palmer C, Roessler RT. Requesting classroom accommodations: self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2000;66(3):38-43.

1. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

2. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

3. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

4. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

5. Branker C. Deserving design: the new generation of student veterans. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):59-66.

6. Burnett SE, Segoria J. Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: it takes a community. J Postsecond Educ and Disabil. 2009;22(1):53-58.

7. Mitchell K. Understanding academic reasonable accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses—part 1, the foundation. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):33-39.

8. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183.

9. Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005.

10. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47.

11. Salzer MS, Wick LC, Rogers JA. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370-375.

12. Shackelford AL. Documenting the needs of student veterans with disabilities: intersection roadblocks, solutions, and legal realities. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):36-42.

13. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522-541.

14. Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142.

15. Palmer C, Roessler RT. Requesting classroom accommodations: self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2000;66(3):38-43.