User login

Academic Reasonable Accommodations for Post-9/11 Veterans With Psychiatric Diagnoses, Part 2

Among the ever increasing number of post-9/11 veterans pursuing higher education are many who carry psychological injuries, which include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of these mental health issues can create acquired learning disabilities involving impairments in memory, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking.1-4 Such learning disabilities can prevent a soldier from successfully transitioning to student-veteran.

Academic reasonable accommodations for veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can strategically enhance student-veteran role integration. Similar to reasonable accommodations for physical diagnoses, academic accommodations for psychiatric conditions enhance qualifying student-veterans’ abilities to successfully pursue higher education by enabling them to compensate for deficits in memory, recall, concentration, and abstract thinking. Such assistance for veterans with disabilities has been advocated in order to promote academic progression and student empowerment.5,6 Although academic accommodations enable veterans to compensate for learning disabilities, such interventions are not routinely requested for a variety of reasons. There are several key factors influencing veterans’ decisions to request such accommodations.

To promote a healthy transition to the student-veteran role, health care providers (HCPs) should initiate conversations about potential acquired learning disabilities with post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses who are or will become students. Unfortunately, the medical literature includes little information on this topic or on how to have these conversations. To date, there is no suggested theoretical framework for guiding such discussions.

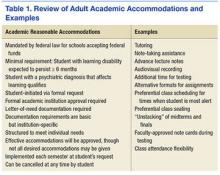

As a foundation for such discussion, Part 1 of this article explained the implications of psychiatric diagnoses and other common factors that can significantly impede adult learning among post-9/11 veterans who are separated from service.7 Part 1 also addressed the fundamentals of academic reasonable accommodations, which are outlined in Table 1.

Through use of a theoretical model, part 2 of this study defines key factors influencing post-9/11 veterans’ decision to request academic reasonable accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses. It also provides practical advice for facilitating clinical conversations at each stage of the model to promote the acceptance of academic reasonable accommodations among eligible post-9/11 veterans.

Health Belief Model

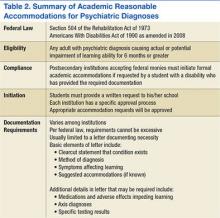

The health belief model (HBM) can be adopted to understand the steps of veterans’ decision-making processes involving reasonable accommodations. The model outlines determinants of human behavior that influence the potential health care decision to deliberately mitigate harm from a perceived health threat.8,9 The 6 primary components are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.8,9 The HBM previously has been applied to a diverse range of health behaviors involving prevention, medical regimen adherence, and utilization of health care services.10 Its application to learning impairment and academic reasonable accommodations is outlined in Table 2.

When the HBM framework is applied to academic accommodations, the perceived health threat is acquired learning disability. The desired health care decision is the act of requesting academic reasonable accommodations. The targeted population at risk is the post-9/11 veteran cohort with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses who are enrolled in, or who are considering, postsecondary education.

The initial perceived susceptibility step determines the degree to which these veterans judge themselves as being at risk for learning impairment because of psychiatric diagnoses. During this step, it is imperative that HCPs educate veterans on how mental health conditions can alter adult learning styles. Clinicians should describe the negative effects of psychiatric symptoms on memory, concentration, focus, attention, and abstract thinking. Insight is developed in this step as veterans recognize that their academic endeavors potentially could be affected by underlying mental health symptoms.

Perceived Severity

Recognition of the perceived severity of impaired learning is the next step in HBM. Veterans will need to self-evaluate their actual or potential academic performance based on their current state of memory, concentration, focus, and attention. Although many veterans might determine that the impact is transient or minimal, a significant number of veterans will observe that their learning abilities are greatly affected. If veterans identify with loss of those skills since the onset of serious mental health issues, there should be further discussion regarding the existence of academic accommodations that address any learning impairment expected to last longer than 6 months.

As discussed in part 1, mental health diagnoses involving mood, though possessing individually distinct diagnostic criteria, create potentially similar global learning impairments in terms of decreased memory, poor concentration, and slowed executive functioning.1-4 Insight into the impact of any acquired learning disability from these mental health conditions and/or associated pharmacologic treatment can be encouraged if the clinician and client jointly review the client’s self-described premorbid learning style and compare it with the client’s current functioning in day-to-day activities requiring memory, concentration, and decision making. A clinician can use a gentle emphasis on the incongruities between premorbid learning ability and present-day impairments as a springboard for discussion about ways to compensate for learning impairments.

Additional insight can be elicited by providing practical examples of how other factors can accentuate the learning difficulties caused by serious or persistent psychiatric symptoms. By discussing these issues, clinicians can provide veterans with a more realistic understanding of potential obstacles in the postsecondary setting and the need for a strategic plan to address such challenges. For example, if a veteran takes prescription medications to manage underlying psychiatric conditions, a discussion regarding pertinent pharmacologic adverse effects (AEs) can highlight how academic performance might be affected. As outlined in part 1, fatigue, drowsiness, restlessness, mental grogginess, and insomnia are just a few medication AEs that may impair academic performance by negatively affecting memory, concentration, and executive functioning.

There are multiple circumstances that can increase the degree to which psychiatric symptoms impede recall, memory, insight, judgment, concentration, attention, organization, and abstract thinking. Impaired memory, poor concentration, irritability, and decreased attention can occur in the normal postmilitary transition period or as residual effects from mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Multiple role responsibilities, such as being a spouse and parent, also can present significant mental distractions from academic endeavors. A physical impairment, such as tinnitus, hearing loss, or chronic pain, can impede classroom participation.

At this juncture, HCPs also should identify the academic consequences of impaired learning. Knowing these consequences will help veterans decide whether a course of action is needed to compensate for any learning disability that may be present. Inability to finish timed tests, difficulty taking notes, and inefficient studying are some of the more serious potential sequelae. Feared long-term consequences include a lack of progress through the required course load and, ultimately, failing courses.

A basic explanation of the potential financial effects of poor academic achievement provides another practical method for clinicians to outline negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. The student’s sole income for basic necessities is often the post-9/11 GI Bill, which pays for up to 36 months of education benefits and includes a living allowance and book stipend.

Unfortunately, given their financial dependence on the GI Bill, many veterans who withdraw from classes due to academic difficulties face economic uncertainty. If their withdrawal is not approved by the GI Bill program, these veterans must pay back all the money granted during the semester. Veterans who remain in school despite receiving failing marks cannot recover money spent on failed courses. This potentially results in veterans exceeding their entire GI Bill allotment before completing course requirements for their desired certificate or degree. Many veterans logically conclude that the potential financial devastation is a sufficiently severe consequence of impaired learning ability, and those who believe they have significantly impaired learning ability may become more motivated to reduce any risk of academic failure by pursuing academic accommodations.

In tandem with reviewing the potential severity of the problem, clinicians always should emphasize the availability of academic accommodations to circumvent the negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. Veterans who experience academic difficulties but are unaware of academic interventions may decide to forgo postsecondary education. By understanding basic details about accommodations, veterans can make the informed decision to pursue these interventions as part of a plan for academic success.

Perceived Benefits

Although identifying perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are necessary for veterans to consider academic reasonable accommodation use, eligible veterans still may not understand how these accommodations can apply to their situation. In the next step of HBM, veterans must view formal academic accommodations as a desirable solution to mitigate the effects of impaired learning ability. Veterans must appreciate the perceived benefits of such requests before they elect to pursue them.

At this point, HCPs should provide examples of academic accommodations to illustrate the simplicity and ease of such interventions. Tutoring, note-taking assistance, and providing additional time for testing are examples of a few types of accommodations featuring advantages that should be readily apparent to veterans returning to school. These measures not only lessen the likelihood of struggling academically, but also afford an opportunity to excel. By painting accommodations as a powerful method of self-advocacy, HCPs can inform veterans that accommodations enable a measure of control within the academic setting and assist with planning.

Perceived Barriers

Although identifying perceived benefits may be persuasive, discerning perceived barriers is an important HBM step that influences whether veterans will seek academic accommodations. Fortunately, many of the common barriers to accommodation requests are simply misconceptions that clinicians can address easily. For example, some veterans misconstrue reasonable accommodations as giving them an unfair advantage, which they find offensive to their personal integrity and pride. Clinicians should point out to these veterans that accommodations address deficits in learning abilities and merely level the academic playing field so the student-veteran is on par with those students without such impairments. The core work needed to pass the class remains unchanged by such accommodations.

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

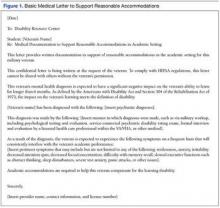

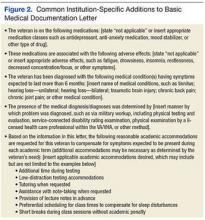

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from [email protected]).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.

Conclusion

Formal academic accommodations are viable tools for cultivating academic success among student-veterans with significant psychiatric conditions. The adoption of such interventions requires understanding post-9/11 veterans’ motivation and concerns about formal academic accommodation requests. Application of the HBM can guide clinicians in their discussions with post-9/11 veterans. By understanding the veterans’ perspectives on the subject, HCPs can directly address the factors influencing the decision to seek academic accommodations.

Ensuring successful transition to the student-veteran role is of prime importance for veterans who bear emotional scars from military service. To this author’s knowledge, no structured educational programs currently exist that inform either post-9/11 veterans or their HCPs about pertinent aspects of academic accommodations for student-veterans with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses that impede learning. Future endeavors need to include development of programs to inform veterans and providers about this important topic. Such programs should not only promote the dissemination of general information, but also explore specific ways to tailor accommodations to the cognitive needs of each veteran.

1. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

2. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

3. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

4. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

5. Branker C. Deserving design: the new generation of student veterans. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):59-66.

6. Burnett SE, Segoria J. Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: it takes a community. J Postsecond Educ and Disabil. 2009;22(1):53-58.

7. Mitchell K. Understanding academic reasonable accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses—part 1, the foundation. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):33-39.

8. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183.

9. Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005.

10. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47.

11. Salzer MS, Wick LC, Rogers JA. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370-375.

12. Shackelford AL. Documenting the needs of student veterans with disabilities: intersection roadblocks, solutions, and legal realities. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):36-42.

13. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522-541.

14. Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142.

15. Palmer C, Roessler RT. Requesting classroom accommodations: self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2000;66(3):38-43.

Among the ever increasing number of post-9/11 veterans pursuing higher education are many who carry psychological injuries, which include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of these mental health issues can create acquired learning disabilities involving impairments in memory, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking.1-4 Such learning disabilities can prevent a soldier from successfully transitioning to student-veteran.

Academic reasonable accommodations for veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can strategically enhance student-veteran role integration. Similar to reasonable accommodations for physical diagnoses, academic accommodations for psychiatric conditions enhance qualifying student-veterans’ abilities to successfully pursue higher education by enabling them to compensate for deficits in memory, recall, concentration, and abstract thinking. Such assistance for veterans with disabilities has been advocated in order to promote academic progression and student empowerment.5,6 Although academic accommodations enable veterans to compensate for learning disabilities, such interventions are not routinely requested for a variety of reasons. There are several key factors influencing veterans’ decisions to request such accommodations.

To promote a healthy transition to the student-veteran role, health care providers (HCPs) should initiate conversations about potential acquired learning disabilities with post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses who are or will become students. Unfortunately, the medical literature includes little information on this topic or on how to have these conversations. To date, there is no suggested theoretical framework for guiding such discussions.

As a foundation for such discussion, Part 1 of this article explained the implications of psychiatric diagnoses and other common factors that can significantly impede adult learning among post-9/11 veterans who are separated from service.7 Part 1 also addressed the fundamentals of academic reasonable accommodations, which are outlined in Table 1.

Through use of a theoretical model, part 2 of this study defines key factors influencing post-9/11 veterans’ decision to request academic reasonable accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses. It also provides practical advice for facilitating clinical conversations at each stage of the model to promote the acceptance of academic reasonable accommodations among eligible post-9/11 veterans.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model (HBM) can be adopted to understand the steps of veterans’ decision-making processes involving reasonable accommodations. The model outlines determinants of human behavior that influence the potential health care decision to deliberately mitigate harm from a perceived health threat.8,9 The 6 primary components are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.8,9 The HBM previously has been applied to a diverse range of health behaviors involving prevention, medical regimen adherence, and utilization of health care services.10 Its application to learning impairment and academic reasonable accommodations is outlined in Table 2.

When the HBM framework is applied to academic accommodations, the perceived health threat is acquired learning disability. The desired health care decision is the act of requesting academic reasonable accommodations. The targeted population at risk is the post-9/11 veteran cohort with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses who are enrolled in, or who are considering, postsecondary education.

The initial perceived susceptibility step determines the degree to which these veterans judge themselves as being at risk for learning impairment because of psychiatric diagnoses. During this step, it is imperative that HCPs educate veterans on how mental health conditions can alter adult learning styles. Clinicians should describe the negative effects of psychiatric symptoms on memory, concentration, focus, attention, and abstract thinking. Insight is developed in this step as veterans recognize that their academic endeavors potentially could be affected by underlying mental health symptoms.

Perceived Severity

Recognition of the perceived severity of impaired learning is the next step in HBM. Veterans will need to self-evaluate their actual or potential academic performance based on their current state of memory, concentration, focus, and attention. Although many veterans might determine that the impact is transient or minimal, a significant number of veterans will observe that their learning abilities are greatly affected. If veterans identify with loss of those skills since the onset of serious mental health issues, there should be further discussion regarding the existence of academic accommodations that address any learning impairment expected to last longer than 6 months.

As discussed in part 1, mental health diagnoses involving mood, though possessing individually distinct diagnostic criteria, create potentially similar global learning impairments in terms of decreased memory, poor concentration, and slowed executive functioning.1-4 Insight into the impact of any acquired learning disability from these mental health conditions and/or associated pharmacologic treatment can be encouraged if the clinician and client jointly review the client’s self-described premorbid learning style and compare it with the client’s current functioning in day-to-day activities requiring memory, concentration, and decision making. A clinician can use a gentle emphasis on the incongruities between premorbid learning ability and present-day impairments as a springboard for discussion about ways to compensate for learning impairments.

Additional insight can be elicited by providing practical examples of how other factors can accentuate the learning difficulties caused by serious or persistent psychiatric symptoms. By discussing these issues, clinicians can provide veterans with a more realistic understanding of potential obstacles in the postsecondary setting and the need for a strategic plan to address such challenges. For example, if a veteran takes prescription medications to manage underlying psychiatric conditions, a discussion regarding pertinent pharmacologic adverse effects (AEs) can highlight how academic performance might be affected. As outlined in part 1, fatigue, drowsiness, restlessness, mental grogginess, and insomnia are just a few medication AEs that may impair academic performance by negatively affecting memory, concentration, and executive functioning.

There are multiple circumstances that can increase the degree to which psychiatric symptoms impede recall, memory, insight, judgment, concentration, attention, organization, and abstract thinking. Impaired memory, poor concentration, irritability, and decreased attention can occur in the normal postmilitary transition period or as residual effects from mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Multiple role responsibilities, such as being a spouse and parent, also can present significant mental distractions from academic endeavors. A physical impairment, such as tinnitus, hearing loss, or chronic pain, can impede classroom participation.

At this juncture, HCPs also should identify the academic consequences of impaired learning. Knowing these consequences will help veterans decide whether a course of action is needed to compensate for any learning disability that may be present. Inability to finish timed tests, difficulty taking notes, and inefficient studying are some of the more serious potential sequelae. Feared long-term consequences include a lack of progress through the required course load and, ultimately, failing courses.

A basic explanation of the potential financial effects of poor academic achievement provides another practical method for clinicians to outline negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. The student’s sole income for basic necessities is often the post-9/11 GI Bill, which pays for up to 36 months of education benefits and includes a living allowance and book stipend.

Unfortunately, given their financial dependence on the GI Bill, many veterans who withdraw from classes due to academic difficulties face economic uncertainty. If their withdrawal is not approved by the GI Bill program, these veterans must pay back all the money granted during the semester. Veterans who remain in school despite receiving failing marks cannot recover money spent on failed courses. This potentially results in veterans exceeding their entire GI Bill allotment before completing course requirements for their desired certificate or degree. Many veterans logically conclude that the potential financial devastation is a sufficiently severe consequence of impaired learning ability, and those who believe they have significantly impaired learning ability may become more motivated to reduce any risk of academic failure by pursuing academic accommodations.

In tandem with reviewing the potential severity of the problem, clinicians always should emphasize the availability of academic accommodations to circumvent the negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. Veterans who experience academic difficulties but are unaware of academic interventions may decide to forgo postsecondary education. By understanding basic details about accommodations, veterans can make the informed decision to pursue these interventions as part of a plan for academic success.

Perceived Benefits

Although identifying perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are necessary for veterans to consider academic reasonable accommodation use, eligible veterans still may not understand how these accommodations can apply to their situation. In the next step of HBM, veterans must view formal academic accommodations as a desirable solution to mitigate the effects of impaired learning ability. Veterans must appreciate the perceived benefits of such requests before they elect to pursue them.

At this point, HCPs should provide examples of academic accommodations to illustrate the simplicity and ease of such interventions. Tutoring, note-taking assistance, and providing additional time for testing are examples of a few types of accommodations featuring advantages that should be readily apparent to veterans returning to school. These measures not only lessen the likelihood of struggling academically, but also afford an opportunity to excel. By painting accommodations as a powerful method of self-advocacy, HCPs can inform veterans that accommodations enable a measure of control within the academic setting and assist with planning.

Perceived Barriers

Although identifying perceived benefits may be persuasive, discerning perceived barriers is an important HBM step that influences whether veterans will seek academic accommodations. Fortunately, many of the common barriers to accommodation requests are simply misconceptions that clinicians can address easily. For example, some veterans misconstrue reasonable accommodations as giving them an unfair advantage, which they find offensive to their personal integrity and pride. Clinicians should point out to these veterans that accommodations address deficits in learning abilities and merely level the academic playing field so the student-veteran is on par with those students without such impairments. The core work needed to pass the class remains unchanged by such accommodations.

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from [email protected]).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.

Conclusion

Formal academic accommodations are viable tools for cultivating academic success among student-veterans with significant psychiatric conditions. The adoption of such interventions requires understanding post-9/11 veterans’ motivation and concerns about formal academic accommodation requests. Application of the HBM can guide clinicians in their discussions with post-9/11 veterans. By understanding the veterans’ perspectives on the subject, HCPs can directly address the factors influencing the decision to seek academic accommodations.

Ensuring successful transition to the student-veteran role is of prime importance for veterans who bear emotional scars from military service. To this author’s knowledge, no structured educational programs currently exist that inform either post-9/11 veterans or their HCPs about pertinent aspects of academic accommodations for student-veterans with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses that impede learning. Future endeavors need to include development of programs to inform veterans and providers about this important topic. Such programs should not only promote the dissemination of general information, but also explore specific ways to tailor accommodations to the cognitive needs of each veteran.

Among the ever increasing number of post-9/11 veterans pursuing higher education are many who carry psychological injuries, which include depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The effects of these mental health issues can create acquired learning disabilities involving impairments in memory, attention, concentration, and abstract thinking.1-4 Such learning disabilities can prevent a soldier from successfully transitioning to student-veteran.

Academic reasonable accommodations for veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can strategically enhance student-veteran role integration. Similar to reasonable accommodations for physical diagnoses, academic accommodations for psychiatric conditions enhance qualifying student-veterans’ abilities to successfully pursue higher education by enabling them to compensate for deficits in memory, recall, concentration, and abstract thinking. Such assistance for veterans with disabilities has been advocated in order to promote academic progression and student empowerment.5,6 Although academic accommodations enable veterans to compensate for learning disabilities, such interventions are not routinely requested for a variety of reasons. There are several key factors influencing veterans’ decisions to request such accommodations.

To promote a healthy transition to the student-veteran role, health care providers (HCPs) should initiate conversations about potential acquired learning disabilities with post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses who are or will become students. Unfortunately, the medical literature includes little information on this topic or on how to have these conversations. To date, there is no suggested theoretical framework for guiding such discussions.

As a foundation for such discussion, Part 1 of this article explained the implications of psychiatric diagnoses and other common factors that can significantly impede adult learning among post-9/11 veterans who are separated from service.7 Part 1 also addressed the fundamentals of academic reasonable accommodations, which are outlined in Table 1.

Through use of a theoretical model, part 2 of this study defines key factors influencing post-9/11 veterans’ decision to request academic reasonable accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses. It also provides practical advice for facilitating clinical conversations at each stage of the model to promote the acceptance of academic reasonable accommodations among eligible post-9/11 veterans.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model (HBM) can be adopted to understand the steps of veterans’ decision-making processes involving reasonable accommodations. The model outlines determinants of human behavior that influence the potential health care decision to deliberately mitigate harm from a perceived health threat.8,9 The 6 primary components are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy.8,9 The HBM previously has been applied to a diverse range of health behaviors involving prevention, medical regimen adherence, and utilization of health care services.10 Its application to learning impairment and academic reasonable accommodations is outlined in Table 2.

When the HBM framework is applied to academic accommodations, the perceived health threat is acquired learning disability. The desired health care decision is the act of requesting academic reasonable accommodations. The targeted population at risk is the post-9/11 veteran cohort with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses who are enrolled in, or who are considering, postsecondary education.

The initial perceived susceptibility step determines the degree to which these veterans judge themselves as being at risk for learning impairment because of psychiatric diagnoses. During this step, it is imperative that HCPs educate veterans on how mental health conditions can alter adult learning styles. Clinicians should describe the negative effects of psychiatric symptoms on memory, concentration, focus, attention, and abstract thinking. Insight is developed in this step as veterans recognize that their academic endeavors potentially could be affected by underlying mental health symptoms.

Perceived Severity

Recognition of the perceived severity of impaired learning is the next step in HBM. Veterans will need to self-evaluate their actual or potential academic performance based on their current state of memory, concentration, focus, and attention. Although many veterans might determine that the impact is transient or minimal, a significant number of veterans will observe that their learning abilities are greatly affected. If veterans identify with loss of those skills since the onset of serious mental health issues, there should be further discussion regarding the existence of academic accommodations that address any learning impairment expected to last longer than 6 months.

As discussed in part 1, mental health diagnoses involving mood, though possessing individually distinct diagnostic criteria, create potentially similar global learning impairments in terms of decreased memory, poor concentration, and slowed executive functioning.1-4 Insight into the impact of any acquired learning disability from these mental health conditions and/or associated pharmacologic treatment can be encouraged if the clinician and client jointly review the client’s self-described premorbid learning style and compare it with the client’s current functioning in day-to-day activities requiring memory, concentration, and decision making. A clinician can use a gentle emphasis on the incongruities between premorbid learning ability and present-day impairments as a springboard for discussion about ways to compensate for learning impairments.

Additional insight can be elicited by providing practical examples of how other factors can accentuate the learning difficulties caused by serious or persistent psychiatric symptoms. By discussing these issues, clinicians can provide veterans with a more realistic understanding of potential obstacles in the postsecondary setting and the need for a strategic plan to address such challenges. For example, if a veteran takes prescription medications to manage underlying psychiatric conditions, a discussion regarding pertinent pharmacologic adverse effects (AEs) can highlight how academic performance might be affected. As outlined in part 1, fatigue, drowsiness, restlessness, mental grogginess, and insomnia are just a few medication AEs that may impair academic performance by negatively affecting memory, concentration, and executive functioning.

There are multiple circumstances that can increase the degree to which psychiatric symptoms impede recall, memory, insight, judgment, concentration, attention, organization, and abstract thinking. Impaired memory, poor concentration, irritability, and decreased attention can occur in the normal postmilitary transition period or as residual effects from mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury. Multiple role responsibilities, such as being a spouse and parent, also can present significant mental distractions from academic endeavors. A physical impairment, such as tinnitus, hearing loss, or chronic pain, can impede classroom participation.

At this juncture, HCPs also should identify the academic consequences of impaired learning. Knowing these consequences will help veterans decide whether a course of action is needed to compensate for any learning disability that may be present. Inability to finish timed tests, difficulty taking notes, and inefficient studying are some of the more serious potential sequelae. Feared long-term consequences include a lack of progress through the required course load and, ultimately, failing courses.

A basic explanation of the potential financial effects of poor academic achievement provides another practical method for clinicians to outline negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. The student’s sole income for basic necessities is often the post-9/11 GI Bill, which pays for up to 36 months of education benefits and includes a living allowance and book stipend.

Unfortunately, given their financial dependence on the GI Bill, many veterans who withdraw from classes due to academic difficulties face economic uncertainty. If their withdrawal is not approved by the GI Bill program, these veterans must pay back all the money granted during the semester. Veterans who remain in school despite receiving failing marks cannot recover money spent on failed courses. This potentially results in veterans exceeding their entire GI Bill allotment before completing course requirements for their desired certificate or degree. Many veterans logically conclude that the potential financial devastation is a sufficiently severe consequence of impaired learning ability, and those who believe they have significantly impaired learning ability may become more motivated to reduce any risk of academic failure by pursuing academic accommodations.

In tandem with reviewing the potential severity of the problem, clinicians always should emphasize the availability of academic accommodations to circumvent the negative consequences of an acquired learning disability. Veterans who experience academic difficulties but are unaware of academic interventions may decide to forgo postsecondary education. By understanding basic details about accommodations, veterans can make the informed decision to pursue these interventions as part of a plan for academic success.

Perceived Benefits

Although identifying perceived susceptibility and perceived severity are necessary for veterans to consider academic reasonable accommodation use, eligible veterans still may not understand how these accommodations can apply to their situation. In the next step of HBM, veterans must view formal academic accommodations as a desirable solution to mitigate the effects of impaired learning ability. Veterans must appreciate the perceived benefits of such requests before they elect to pursue them.

At this point, HCPs should provide examples of academic accommodations to illustrate the simplicity and ease of such interventions. Tutoring, note-taking assistance, and providing additional time for testing are examples of a few types of accommodations featuring advantages that should be readily apparent to veterans returning to school. These measures not only lessen the likelihood of struggling academically, but also afford an opportunity to excel. By painting accommodations as a powerful method of self-advocacy, HCPs can inform veterans that accommodations enable a measure of control within the academic setting and assist with planning.

Perceived Barriers

Although identifying perceived benefits may be persuasive, discerning perceived barriers is an important HBM step that influences whether veterans will seek academic accommodations. Fortunately, many of the common barriers to accommodation requests are simply misconceptions that clinicians can address easily. For example, some veterans misconstrue reasonable accommodations as giving them an unfair advantage, which they find offensive to their personal integrity and pride. Clinicians should point out to these veterans that accommodations address deficits in learning abilities and merely level the academic playing field so the student-veteran is on par with those students without such impairments. The core work needed to pass the class remains unchanged by such accommodations.

Often a barrier is erected when veterans subscribe to the traditional military definition of disability, which is equated with having overwhelming physical injuries or paralyzing psychological states. These veterans are reluctant to request any formal accommodations, because they do not see themselves as having a disability under this restrictive definition. For these veterans, HCPs need to explain that the broad federal definition of disability does not imply veterans must be disabled in any other aspect of his or her life except for learning.

Some veterans do not want to draw attention to themselves either as a veteran or as a student with learning difficulties.11,12 Aware of civilian stereotyping of veterans, they prefer to remain anonymous. In this instance, clinicians should emphasize that psychiatric diagnoses are confidential and that only the reasonable accommodations are shared with the professor—not the underlying medical problem. The clinician also should emphasize that the accommodations are open to all eligible adult students, not just student-veterans. Therefore, use of such accommodations is not a disclosure of veteran status.

In conjunction with addressing client fears about stereotyping of both veterans and students with learning disabilities, HCPs should be mindful that mental health stigma is a significant barrier to seeking mental health services among military personnel, post-9/11 veterans, and college students.13,14 Therefore, clinicians should emphasize that academic accommodations for psychiatric diagnoses are not self-disclosing of psychiatric concerns and are usually the same accommodations used to address learning disabilities caused by other factors.

Veterans may believe that documentation obtained in support of reasonable accommodations is too intimidating or too personal to reveal. Not realizing that federal law prevents institutions from requesting in-depth documentation, veterans mistakenly believe that they must provide all medical documents in order to qualify for academic accommodations. To assuage these fears, clinicians should inform veterans that schools generally require only a documentation letter from a qualified provider and usually do not require other medical records.

To further alleviate veteran fears and promote a measure of client control, providers may find it beneficial to review the proposed medical documentation letter with the veteran and have the veteran approve the content. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a basic medical documentation letter with optional institution-specific criteria. To ensure compliance with any applicable federal privacy regulations or local facility policy, clinicians should obtain an information release form from the veteran. The medical documentation letter can then be released to the veteran for hand delivery to the academic institution.

Veterans might be concerned about the potential lack of confidentiality regarding the diagnosis contributing to their learning disability. They also may worry that accommodations will prevent them from entering the field of their choice when they graduate, especially for law enforcement careers. These veterans can be reassured by informing them that use of academic accommodations is completely confidential during their school years and will not appear on their school graduation records. Recommending that veterans confirm the established confidentiality process with their schools may help allay fears about inadvertent release of private information by the institution.

Self-Efficacy and Cues to Action

Even after perceived benefits and barriers are identified, veterans still may not act unless they believe that they can intervene appropriately to address the problem. The HBM refers to this step as self-efficacy. Student-veterans must feel empowered to effectively make reasonable accommodation requests and negotiate any potential setbacks to the implementation of those accommodations. Health care providers should inform veterans about the availability of a disability resource center or other counseling service at each school that can help the student-veteran through the process of accommodation approval. Ideally, student-veterans also should receive guidance on how to approach professors regarding both the request for and the implementation of the approved reasonable accommodations.15 Counselors at the institution should offer this guidance and help veterans select the appropriate accommodations.

In the HBM, cues to action occur at every step. These cues consist of the influential factors promoting the desired behavior. Providing answers to common veteran questions about academic accommodations is one cue to action. Another is providing a written step-by-step guide explaining academic accommodations to veterans. (The author has created a veteran-centric guide to academic accommodations. The guide, which explains basic concepts and addresses common barriers to requesting such accommodations, is available upon request from [email protected]).

At all times, positive feedback from clinicians is important in motivating veterans to complete the entire process. Discussion may be stalled at any point if veterans overestimate current academic abilities or underestimate their level of impaired learning ability. Motivational interviewing techniques may help resolve this impasse. However, even if eligible veterans are not interested in pursuing academic accommodations, HCPs should leave the option open for consideration. Although interventions are most beneficial when instituted early in the student’s coursework, veterans can formally request academic accommodations at any stage of their academic career.

Conclusion

Formal academic accommodations are viable tools for cultivating academic success among student-veterans with significant psychiatric conditions. The adoption of such interventions requires understanding post-9/11 veterans’ motivation and concerns about formal academic accommodation requests. Application of the HBM can guide clinicians in their discussions with post-9/11 veterans. By understanding the veterans’ perspectives on the subject, HCPs can directly address the factors influencing the decision to seek academic accommodations.

Ensuring successful transition to the student-veteran role is of prime importance for veterans who bear emotional scars from military service. To this author’s knowledge, no structured educational programs currently exist that inform either post-9/11 veterans or their HCPs about pertinent aspects of academic accommodations for student-veterans with symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses that impede learning. Future endeavors need to include development of programs to inform veterans and providers about this important topic. Such programs should not only promote the dissemination of general information, but also explore specific ways to tailor accommodations to the cognitive needs of each veteran.

1. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

2. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

3. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

4. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

5. Branker C. Deserving design: the new generation of student veterans. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):59-66.

6. Burnett SE, Segoria J. Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: it takes a community. J Postsecond Educ and Disabil. 2009;22(1):53-58.

7. Mitchell K. Understanding academic reasonable accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses—part 1, the foundation. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):33-39.

8. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183.

9. Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005.

10. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47.

11. Salzer MS, Wick LC, Rogers JA. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370-375.

12. Shackelford AL. Documenting the needs of student veterans with disabilities: intersection roadblocks, solutions, and legal realities. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):36-42.

13. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522-541.

14. Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142.

15. Palmer C, Roessler RT. Requesting classroom accommodations: self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2000;66(3):38-43.

1. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

2. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

3. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

4. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

5. Branker C. Deserving design: the new generation of student veterans. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):59-66.

6. Burnett SE, Segoria J. Collaboration for military transition students from combat to college: it takes a community. J Postsecond Educ and Disabil. 2009;22(1):53-58.

7. Mitchell K. Understanding academic reasonable accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses—part 1, the foundation. Fed Pract. 2016;33(4):33-39.

8. Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175-183.

9. Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Deptartment of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005.

10. Janz NK, Becker MH. The health belief model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1-47.

11. Salzer MS, Wick LC, Rogers JA. Familiarity with and use of accommodations and supports among postsecondary students with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):370-375.

12. Shackelford AL. Documenting the needs of student veterans with disabilities: intersection roadblocks, solutions, and legal realities. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):36-42.

13. Eisenberg D, Downs MF, Golberstein E, Zivin K. Stigma and help seeking for mental health among college students. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):522-541.

14. Vogt D. Mental health related beliefs as a barrier to service use for military personnel and veterans: a review. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(2):135-142.

15. Palmer C, Roessler RT. Requesting classroom accommodations: self-advocacy and conflict resolution training for college students with disabilities. J Rehabil. 2000;66(3):38-43.

Academic Reasonable Accommodations for Post-9/11 Veterans With Psychiatric Diagnoses, Part 1

Navigating the postsecondary educational pathway can be an intimidating process for post-9/11 veterans struggling with mental health concerns that may alter learning styles and negatively impact performance.1-4 When significant interference with learning ability is anticipated for more than 6 months, these veterans may qualify for formal academic “reasonable” accommodations under federal disability laws that include the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These accommodations enable students to compensate for learning disabilities and help support the transition to student life. Student veterans often are not aware of the existence of academic reasonable accommodations, because military separation classes, civilian postdeployment orientation, and popular media do not routinely cover information on this subject.

With an overall objective to ease veteran reintegration into the civilian world and promote emotional stability, health care providers (HCPs) are in a unique position to promote the use of formal academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric conditions. However, HCPs must have basic information regarding these interventions before initiating discussions with patients. Current peer-reviewed medical literature has scant information regarding specific aspects of academic reasonable accommodations for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses.

The purpose of this 2-part article (part 2 will be published in May 2016) is to promote a greater understanding of academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses. Part 1 provides a brief background regarding issues pertinent to the post-9/11 student veteran role transition and reviews information regarding various aspects of academic reasonable accommodations, including details on the definition, request process, medical documentation requirements, and common accommodation examples.

Although the focus of the article is on the characteristics of post-9/11 veterans who have separated from military service, it also is relevant for providers involved with service members who have not yet separated. The impact of mental health issues, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and psychosocial stressors on learning ability are potentially applicable to many post-9/11 active-duty soldiers and reservists who are pursuing a secondary education. The academic reasonable accommodations discussed are available to any adult who meets the eligibility criteria—regardless of military status.

Influence of Psychiatric Symptoms on Learning

Although each mental health diagnosis is unique, mental health conditions involving mood share the common symptoms of impaired learning ability.3-8 Problems frequently experienced include decreased concentration, shortened attention span, difficulty in making new memories or storing new information, and the inability to recall information previously learned.6-8 Other reported conditions include difficulty with prioritization of tasks, losing track of time, difficulty focusing on tasks, and taking longer to complete assignments.3,4 Increased irritability accompanies many of these issues. Low tolerance to frustration may occur as evidenced by an outburst of anger or resignation to defeat when minor barriers are encountered, especially when authority figures or bureaucratic rules create those perceived barriers.3,4 Persistent impaired ability to articulate ideas or thoughts and difficulty performing abstract thinking also are often noticed when moderate-to-severe mental health symptoms are present.4,8

Medications commonly used to control psychiatric symptoms and stabilize underlying mental health also can produce adverse effects (AEs) that impact learning ability.9,10 Drug AEs vary but often include significant fatigue, impaired memory, and impaired executive function involving insight, judgment, and/or abstract thinking. Depending on the medication, the individual may experience restlessness or insomnia.

Factors Complicating Successful Integration

The transition period from military service to civilian life presents unique complications for student veterans with symptomatic psychiatric concerns.1,11 Veterans who separate from military service go through a civilian transition period of variable intensity influenced by readjustment difficulties and comorbid conditions.11,12 During this time, veterans are reintegrating into civilian life and assuming new roles that include partner, parent, employee, and family member. This transition can cause many symptoms to appear that potentially influence learning to varying degrees. A summary of impediments to learning in post-9/11 veterans is found in Table 1.

Common transition symptoms include irritability, decreased ability to store and recall information, decreased concentration, decreased attention, and slowed executive functioning.13,14 Sleep disturbances such as altered sleep-wake cycles, nonrestful sleep, inadequate sleep, and nightmares also may occur.13,14 Veterans experiencing these transition period symptoms may face significant difficulties with time management skills, organization, and task execution. If the veteran successfully assimilates into his or her new roles and becomes self-confident within those roles, the symptoms may abate. However, if moderate-to-severe psychiatric symptoms also are present, all transition symptoms likely will have an unpredictable time frame for resolution.3,13,14

Understanding the role responsibilities of student veterans is important in recognizing the added stressors veterans with psychiatric diagnoses have within the academic setting. In general, demographic data indicate that student veterans lead far more complex lives than those of 18- to 22-year-olds who enter postsecondary education without military experience. Student veterans are older, have a broader life experience, and may feel less connected to nonveteran students.15,16 Compared with typical younger college students, undergraduate student veterans are more likely to be married but somewhat less likely to be parents.17 Student veterans who are pursuing graduate degrees are more likely to be married and/or have dependents.17 Those roles imply that student veterans often are juggling multiple responsibilities that are constantly competing for student veterans’ time and attention.

Age differences, multiple roles, and lack of shared life experiences with traditional college students contribute to student veterans’ perceptions of a paucity of campus social support and often lead to a sense of distinct isolation.18,19 These added stressors deplete a veteran’s ability to concentrate on academic studies and may exacerbate the effects of underlying mental health diagnoses, transition issues, and medication use.

Symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses can amplify the difficulties normally experienced when changing from a veteran role to a student veteran role.1 The student veteran’s apprehension about returning to school often is elevated because of the time gap since the veteran was last in a formal, nonmilitary classroom. Acclimated to the structured style of military coursework for many years, student veterans may find adjusting to new teaching styles or different academic expectations awkward.20,21 They may experience heightened anxiety, because expectations of classroom performance may not be as clearcut as it was in the military. Such heightened anxiety can compound learning difficulties caused by underlying emotional states, transition issues, medication AEs, and life stressors.

Related: The VA/DoD Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium: An Overview at Year 1

Many student veterans with impaired learning ability related to psychiatric symptoms also have secondary physical diagnoses that can impede learning. For example, tinnitus and hearing loss are common in combat veterans.22,23 These issues make it hard to participate in a classroom setting because of difficulty in recognizing speech or filtering out background noise. For some, chronic pain may impede concentration, depress mood, worsen irritability, and make prolonged sitting difficult.24,25 Physical disabilities related to amputation or major joint injury may present challenges to participating in certain types of college settings and/or navigating between classes in a timely fashion.26

Although mild-to-moderate TBI sustained in combat often will spontaneously resolve within 3 months, in some individuals, TBI symptoms may persist after months or years.27,28 During this time, learning styles may be altered for veterans exposed to TBI. Similar to the effects caused by other factors impeding learning in post-9/11 veterans, common post-TBI symptoms that reduce academic performance include fatigue, decreased memory, slowed abstract thinking, difficulty articulating thoughts, poor tolerance to frustration, sleep difficulties, chronic pain, and increased irritability.27-29 Veterans with a history of mild TBI often are found to have clinically significant rates of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).27,28,30,31 These findings mirror those found in the general population.32 Mild TBI and PTSD may further complicate the learning process by exacerbating underlying mental health symptoms that already impair academic performance. The degree to which these individuals with TBI and mental health issues will return to premorbid academic functioning is not predictable based on current literature.33

Recognizing the stressors that some combat veterans face in an academic setting is vital to anticipating the added support that is needed by student veterans with concurrent moderate-to-severe psychiatric issues.34 Symptoms usually noted in the transition period may be much more pronounced. Automatic behaviors developed as survival responses during deployment can complicate participation in the educational arena.4,35 Seemingly mundane tasks, such as the daily school commute, can cause significant anxiety and hypervigilance especially when the veterans must navigate crowds and traffic formerly associated with risk of attack in combat-related circumstances.4 Minor roadway debris or roadside construction also can abnormally heighten anxiety because of reflex training to avoid potentially hidden explosive devices during convoy movements.4 Random assignment of a classroom seat can be stress-provoking, because combat veterans’ training compels them to position themselves with the greatest vantage point, usually nearest to exits and with minimal activity behind them.4,35 A need to constantly survey the surroundings for potential cover from hostile events can cause hyper alertness that distracts the student veteran’s full concentration on academic tasks.3,4

Although veterans should be able to adjust learning styles for minor issues or transitory problems, significant psychiatric symptoms have a negative effect on learning and pose a direct threat to academic performance.33,36-38 Moderate-to-severe psychiatric concerns may further heighten transition symptoms, compound psychosocial adjustment, and complicate TBI recovery. In addition, periods of high stress may further provoke symptoms of the underlying psychiatric diagnosis.

Reasonable Accommodations

In postsecondary education, reasonable accommodations are formal modifications or adjustments in the school environment that enable individuals with physical or psychological issues to successfully learn and function within the academic institution. In general, these academic accommodations for student veterans with mental health diagnoses involve modifying the learning environment to compensate for delays in executive functioning, such as memorization, recall, and complex analysis. Coursework is not altered; rather specific actions are used to assist the student to process and recall the material more easily. The reasonable accommodations also may be structured in a way that avoids exacerbating an underlying mental health diagnosis, such as PTSD or anxiety. The purpose of reasonable accommodations is to effectively remove barriers to a student veteran’s ability to learn and succeed academically.

Federal law states that reasonable accommodations must be implemented by all schools that accept federal monies—including GI bill payments.39 Although schools are not required to implement all preferred accommodations requested by veterans, academic institutions are required to implement reasonable, effective strategies for the individual student veteran with a psychological diagnosis that causes learning impairment. However, these institutions are not required to proactively determine who might qualify for such accommodations. A school will not initiate formal academic accommodations unless a veteran makes a specific request and provides qualifying documentation.

Many veterans qualify for reasonable accommodations in the academic setting to compensate for the negative impact that mental health issues can have on academic performance. Specifically, student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses are classified as having a learning disability and are eligible to receive academic accommodations if the psychiatric condition substantially limits, or is expected to limit, learning for more than 6 months.39 Individuals with psychiatric conditions in remission are still classified as having a disability if the disorder would impede learning when symptomatic. A veteran does not need to establish verification of a psychiatric diagnosis connected to military service in order to receive formal academic accommodations. Student veterans who qualify for formal academic accommodations can be fully functional in all other areas of their lives. Examples of qualifying psychiatric diagnoses include PTSD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Although accommodations are individually tailored, there are frequently used accommodations for student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses that have been extremely helpful for those who qualify. Additional time for testing helps the student veteran compensate for the difficulty with abstract thinking, concentration, attention, and recall. Low stimulus testing environments, such as a quiet room, enable a veteran to more easily concentrate. Additional time for completion of assignments without academic penalties is beneficial for a veteran experiencing difficulty with attention, focus, concentration, and organization. Assistance with note-taking or advanced access to lecture notes helps the veteran compensate for decreased focus, attention, and short-term memory impairment. Permitting short breaks without repercussions during a lecture allows the veteran to regain focus and composure if he or she is having difficulties with concentration, attention, restlessness, anxiety, body pain, or emotional flares. Tutoring can help the veteran overcome slowed executive functioning. Faculty-approved notes on an index card may help the veteran compensate for extreme difficulty with memory recall. To prevent visual distraction while reading, use of a blank note card or blank sheet of paper during testing may make it easier for the veteran to focus on each sentence or test question.

On a case-by-case basis, other creative strategies may be used to enable the student veteran to participate more fully in the academic setting. Preferential class scheduling can be arranged to compensate for severely altered sleep patterns. Such changes to the schedule mean a veteran would not have to attend classes during a time frame when his or her body is accustomed to sleeping. Flexibility with class attendance decreases external stressors for the veteran who is having intermittent difficulty with severe sleep disturbances or anxiety in group settings. “Unstacking” midterms or finals allows the student veteran to avoid back-to-back exams and enables him or her to study more effectively for each exam. Virtual classes with self-pacing options may provide more flexibility to complete course requirements while the veteran is dealing with fluctuating emotional symptoms.

Legal Process