User login

Adolescents are an increasingly diverse population reflecting changes in the racial, ethnic, and geopolitical milieus of the United States. The World Health Organization classifies adolescence as ages 10 to 19 years.1 However, given the complexity of adolescent development physically, behaviorally, emotionally, and socially, others propose that adolescence may extend to age 24.2

Recognizing the specific challenges adolescents face is key to providing comprehensive longitudinal health care. Moreover, creating an environment of trust helps to ensure open 2-way communication that can facilitate anticipatory guidance.

Our review focuses on common adolescent issues, including injury from vehicles and firearms, tobacco and substance misuse, obesity, behavioral health, sexual health, and social media use. We discuss current trends and recommend strategies to maximize health and wellness.

Start by framing the visit

Confidentiality

Laws governing confidentiality in adolescent health care vary by state. Be aware of the laws pertaining to your practice setting. In addition, health care facilities may have their own policies regarding consent and confidentiality in adolescent care. Discuss confidentiality with both an adolescent and the parent/guardian at the initial visit. And, to help avoid potential misunderstandings, let them know in advance what will (and will not) be divulged.

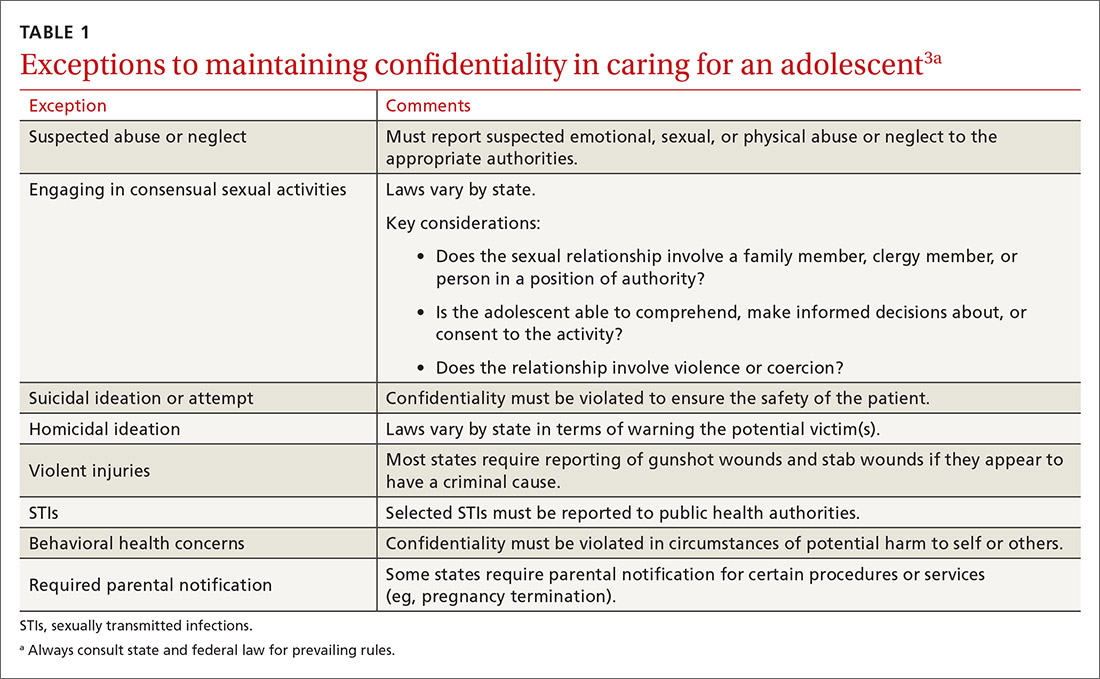

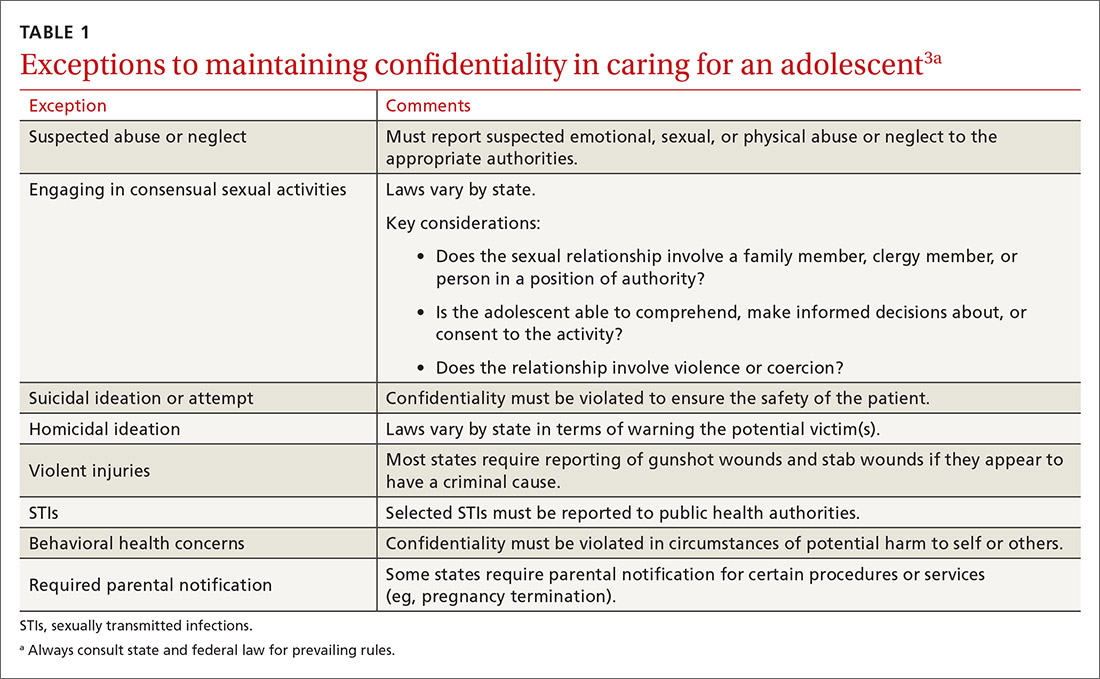

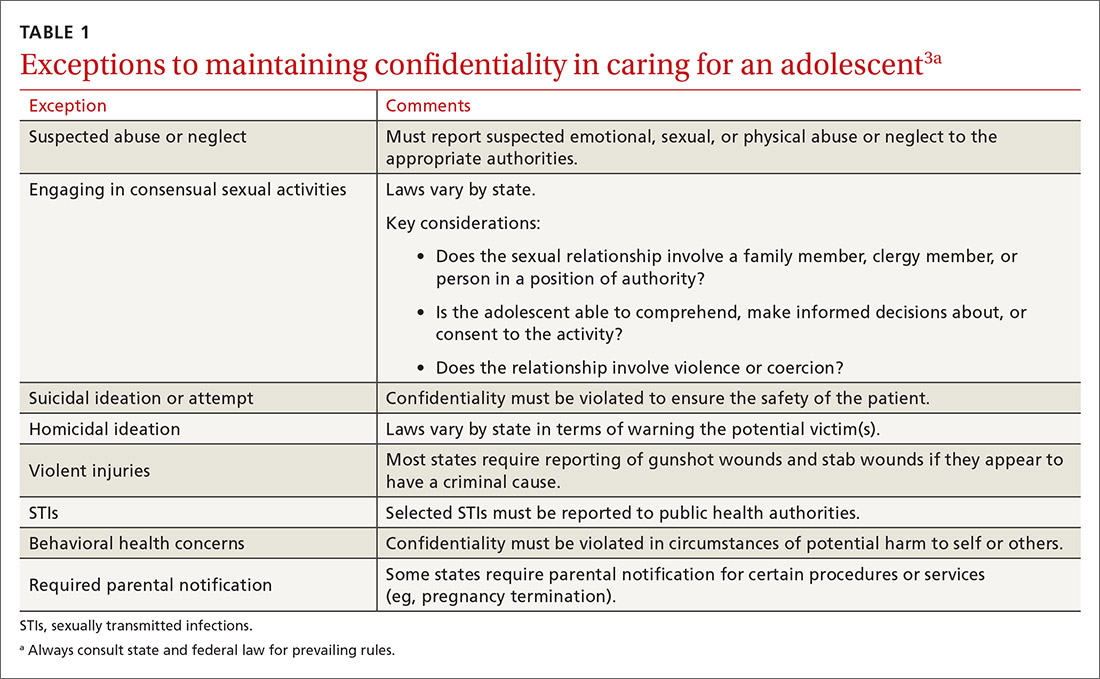

The American Academy of Pediatrics has developed a useful tip sheet regarding confidentiality laws (www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Documents/Confidentiality_Laws.pdf). Examples of required (conditional) disclosure include abuse and suicidal or homicidal ideations. Patients should understand that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are reportable to public health authorities and that potentially injurious behaviors to self or others (eg, excessive drinking prior to driving) may also warrant disclosure(TABLE 13).

Privacy and general visit structure

Create a safe atmosphere where adolescents can discuss personal issues without fear of repercussion or judgment. While parents may prefer to be present during the visit, allowing for time to visit independently with an adolescent offers the opportunity to reinforce issues of privacy and confidentiality. Also discuss your office policies regarding electronic communication, phone communication, and relaying test results.

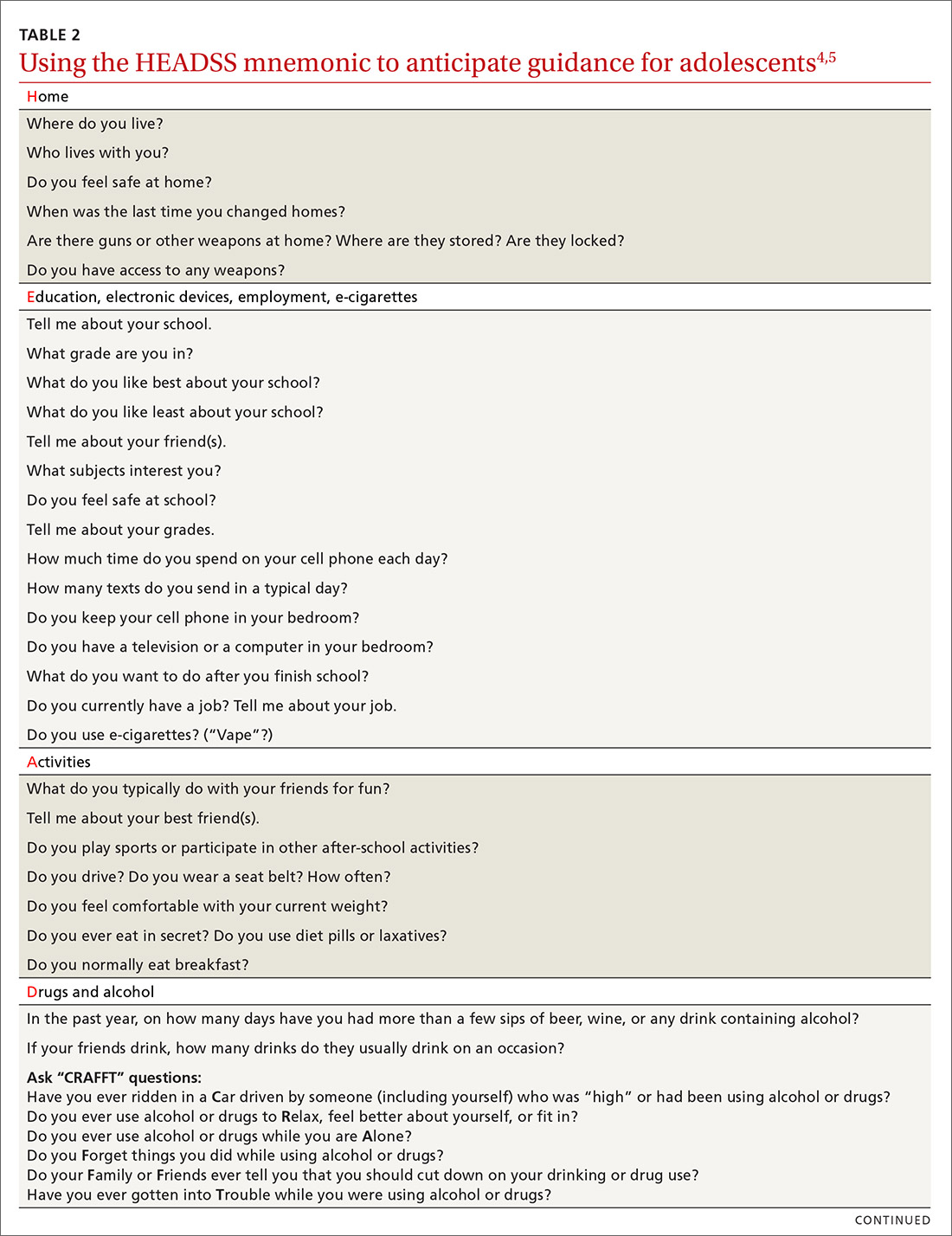

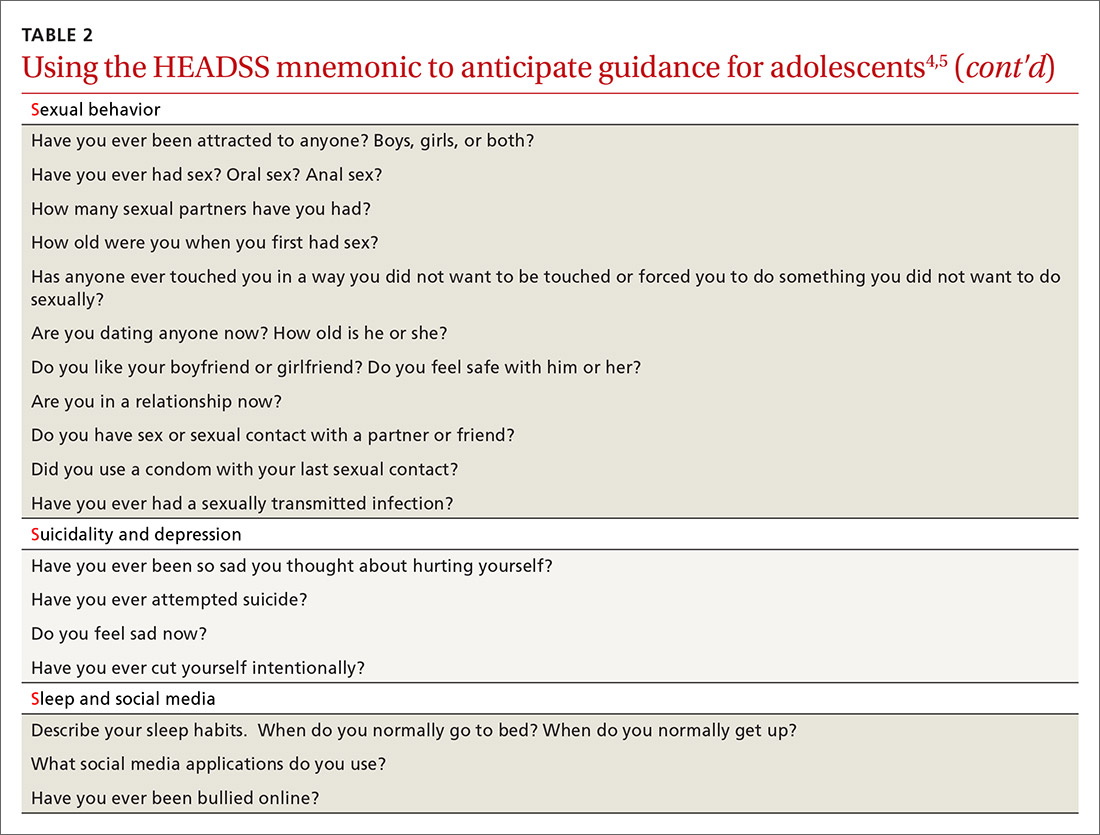

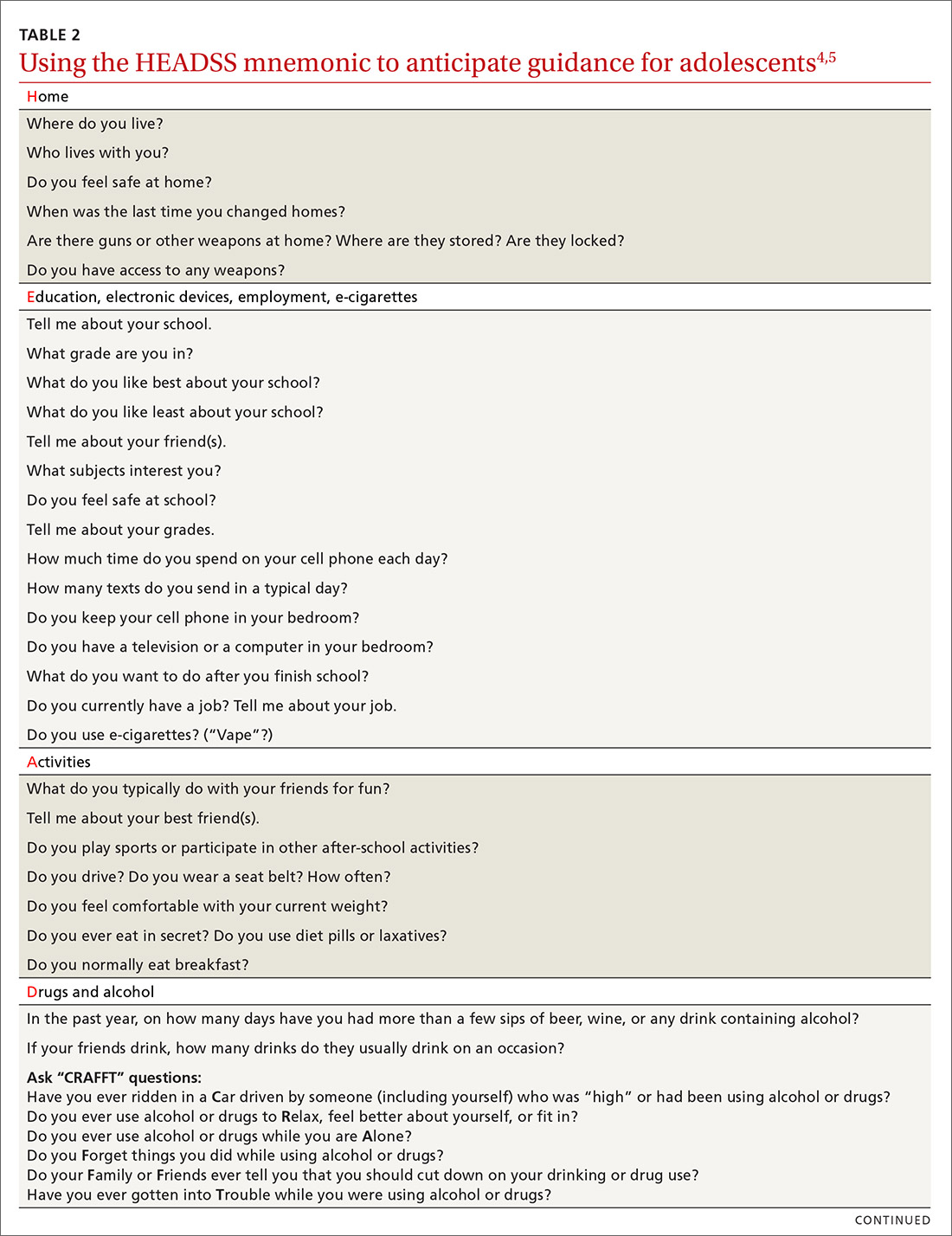

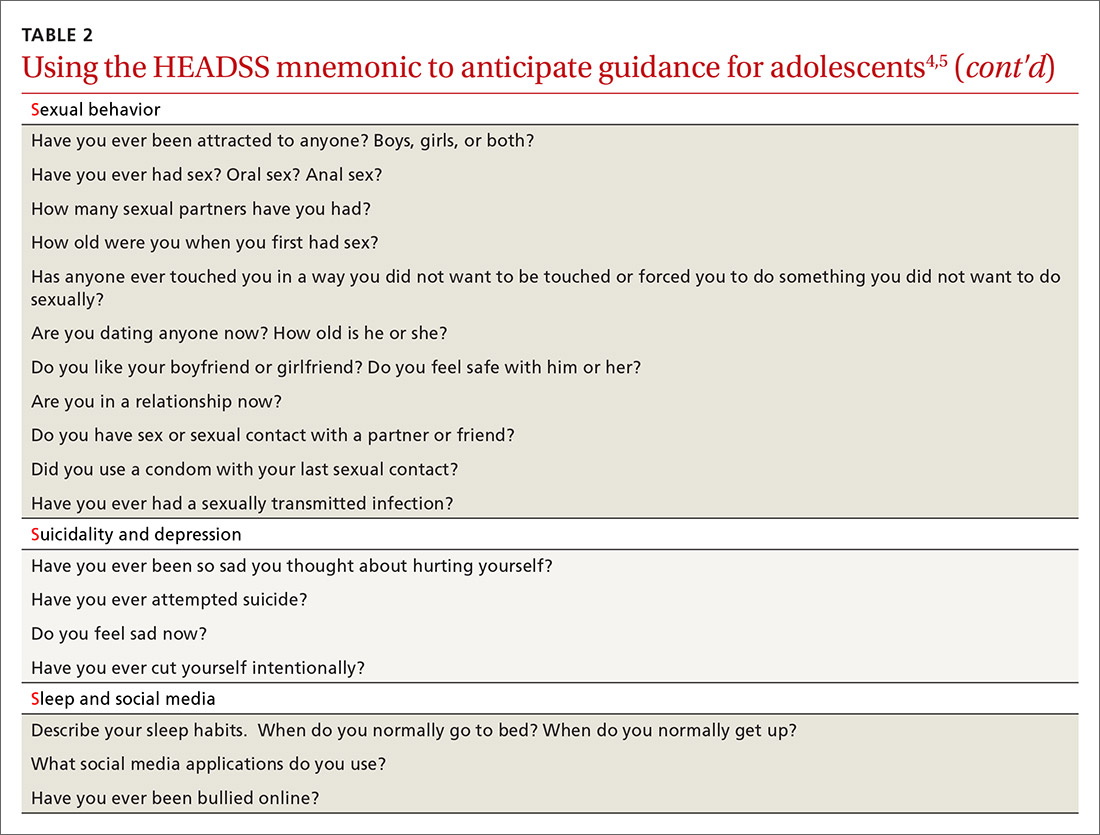

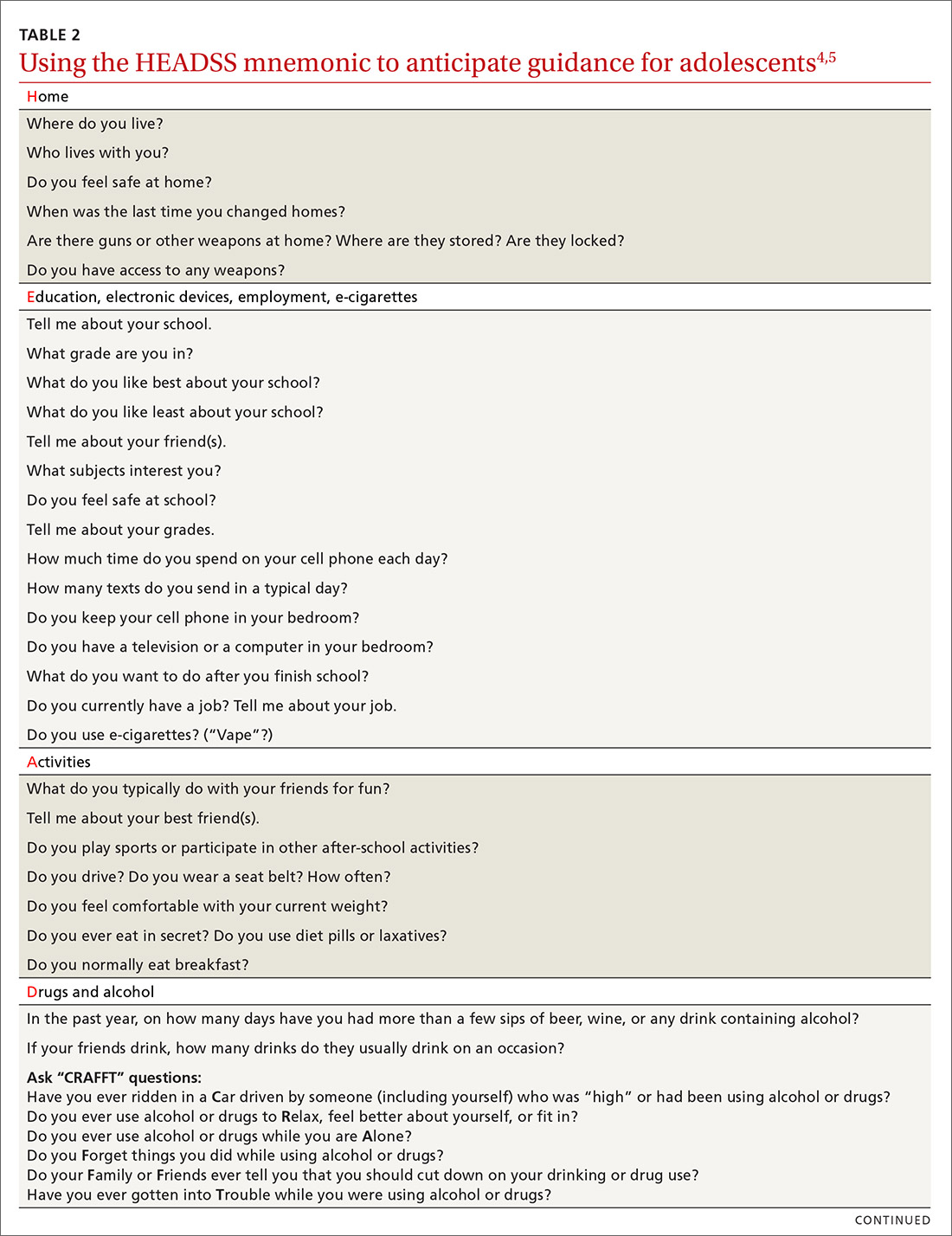

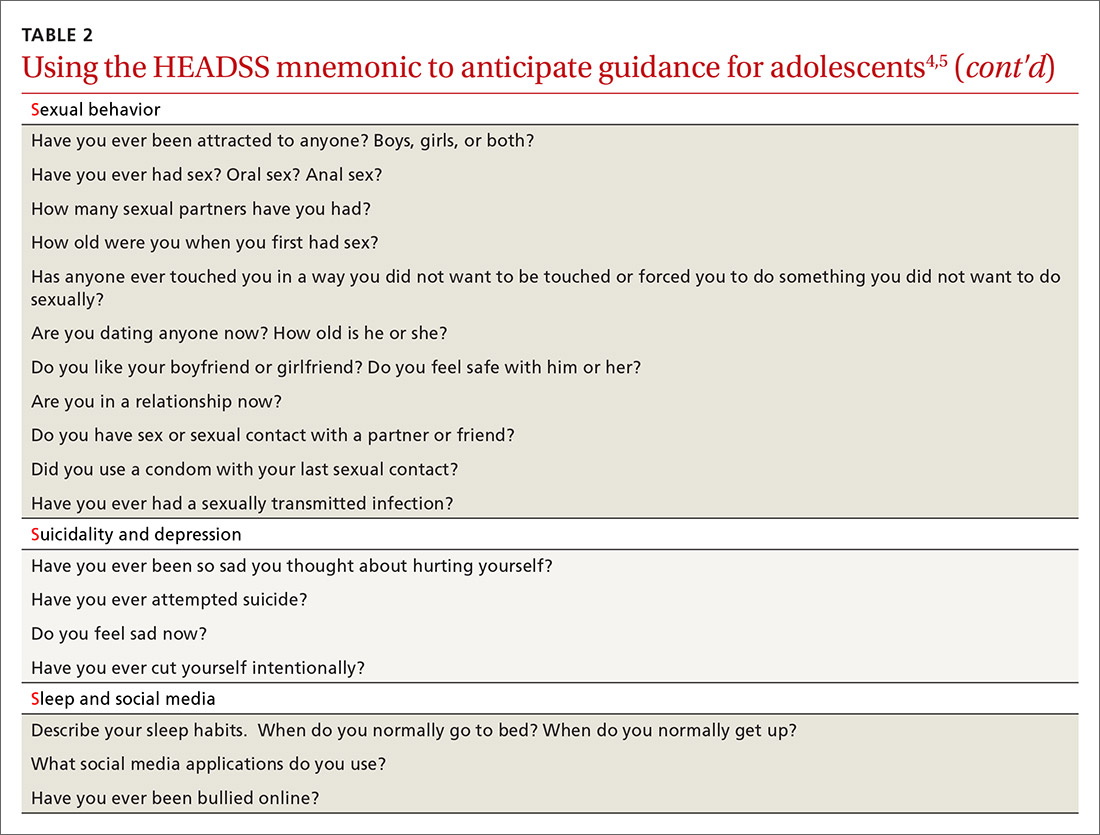

A useful paradigm for organizing a visit for routine adolescent care is to use an expanded version of the HEADSS mnemonic (TABLE 24,5), which includes questions about an adolescent’s Home, Education, Activities, Drug and alcohol use, Sexual behavior, Suicidality and depression, and other topics. Other validated screening tools include RAAPS (Rapid Adolescent Prevention Screening)6 (www.possibilitiesforchange.com/raaps/); the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services7; and the Bright Futures recommendations for preventive care from the American Academy of Pediatrics.8 Below, we consider important topics addressed with the HEADSS approach.

Continue to: Injury from vehicles and firearms

Injury from vehicles and firearms

Motor vehicle accidents and firearm wounds are the 2 leading causes of adolescent injury. In 2016, of the more than 20,000 deaths in children and adolescents (ages 1-19 years), 20% were due to motor vehicle accidents (4074) and 15% were a result of firearm-related injuries (3143). Among firearm-related deaths, 60% were homicides, 35% were suicides, and 4% were due to accidental discharge.9 The rate of firearm-related deaths among American teens is 36 times greater than that of any other developed nation.9 Currently, 1 of every 3 US households with children younger than 18 has a firearm. Data suggest that in 43% of these households, the firearm is loaded and kept in an unlocked location.10

To aid anticipatory guidance, ask adolescents about firearm and seat belt use, drinking and driving, and suicidal thoughts (TABLE 24,5). Advise them to always wear seat belts whether driving or riding as a passenger. They should never drink and drive (or get in a car with someone who has been drinking). Advise parents that if firearms are present in the household, they should be kept in a secure, locked location. Weapons should be separated from ammunition and safety mechanisms should be engaged on all devices.

Tobacco and substance misuse

Tobacco use, the leading preventable cause of death in the United States,11 is responsible for more deaths than alcohol, motor vehicle accidents, suicides, homicides, and HIV disease combined.12 Most tobacco-associated mortality occurs in individuals who began smoking before the age of 18.12 Individuals who start smoking early are also more likely to continue smoking through adulthood.

Encouragingly, tobacco use has declined significantly among adolescents over the past several decades. Roughly 1 in 25 high school seniors reports daily tobacco use.13 Adolescent smoking behaviors are also changing dramatically with the increasing popularity of electronic cigarettes (“vaping”). Currently, more adolescents vape than smoke cigarettes.13 Vaping has additional health risks including toxic lung injury.

Multiple resources can help combat tobacco and nicotine use in adolescents. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians intervene through education or brief counselling to prevent initiation of tobacco use in school-aged children and adolescents.14 Ask teens about tobacco and electronic cigarette use and encourage them to quit when use is acknowledged. Other helpful office-based tools are the “Quit Line” 800-QUIT-NOW and texting “Quit” to 47848. Smokefree teen (https://teen.smokefree.gov/) is a website that reviews the risks of tobacco and nicotine use and provides age-appropriate cessation tools and tips (including a smartphone app and a live-chat feature). Other useful information is available in a report from the Surgeon General on preventing tobacco use among young adults.15

Continue to: Alcohol use

Alcohol use. Three in 5 high school students report ever having used alcohol.13 As with tobacco, adolescent alcohol use has declined over the past decade. However, binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks on 1 occasion for males; ≥ 4 drinks on 1 occasion for females) remains a common high-risk behavior among adolescents (particularly college students). Based on the Monitoring the Future Survey, 1 in 6 high school seniors reported binge drinking in the past 2 weeks.13 While historically more common among males, rates of binge drinking are now basically similar between male and female adolescents.13

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has a screening and intervention guide specifically for adolescents.16

Illicit drug use. Half of adolescents report using an illicit drug by their senior year in high school.13 Marijuana is the most commonly used substance, and laws governing its use are rapidly changing across the United States. Marijuana is illegal in 10 states and legal in 10 states (and the District of Columbia). The remaining states have varying policies on the medical use of marijuana and the decriminalization of marijuana. In addition, cannabinoid (CBD) products are increasingly available. Frequent cannabis use in adolescence has an adverse impact on general executive function (compared with adult users) and learning.17 Marijuana may serve as a gateway drug in the abuse of other substances,18 and its use should be strongly discouraged in adolescents.

Of note, there has been a sharp rise in the illicit use of prescription drugs, particularly opioids, creating a public health emergency across the United States.19 In 2015, more than 4000 young people, ages 15 to 24, died from a drug-related overdose (> 50% of these attributable to opioids).20 Adolescents with a history of substance abuse and behavioral illness are at particular risk. Many adolescents who misuse opioids and other prescription drugs obtain them from friends and relatives.21

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommends universal screening of adolescents for substance abuse. This screening should be accompanied by a brief intervention to prevent, mitigate, or eliminate substance use, or a referral to appropriate treatment sources. This process of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is recommended as part of routine health care.22

Continue to: Obesity and physical activity

Obesity and physical activity

The percentage of overweight and obese adolescents in the United States has more than tripled over the past 40 years,23 and 1 in 5 US adolescents is obese.23 Obese teens are at higher risk for multiple chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and heart disease.24 They are also more likely to be bullied and to have poor self-esteem.25 Only 1 in 5 American high school students engages in 60 or more minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on 5 or more days per week.26

Regular physical activity is, of course, beneficial for cardiorespiratory fitness, bone health, weight control, and improved indices of behavioral health.26 Adolescents who are physically active consistently demonstrate better school attendance and grades.17 Higher levels of physical fitness are also associated with improved overall cognitive performance.24

General recommendations. The Department of Health and Human Services recommends that adolescents get at least 60 minutes of mostly moderate physical activity every day.26 Encourage adolescents to engage in vigorous physical activity (heavy breathing, sweating) at least 3 days a week. As part of their physical activity patterns, adolescents should also engage in muscle-strengthening and bone-strengthening activities on at least 3 days per week.

Behavioral health

As young people develop their sense of personal identity, they also strive for independence. It can be difficult, at times, to differentiate normal adolescent rebellion from true mental illness. An estimated 17% to 19% of adolescents meet criteria for mental illness, and about 7% have a severe psychiatric disorder.27 Only one-third of adolescents with mental illness receive any mental health services.28

Depression. The 1-year incidence of major depression in adolescents is 3% to 4%, and the lifetime prevalence of depressive symptoms is 25% in all high school students.27 Risk factors include ethnic minority status, poor self-esteem, poor health, recent personal crisis, insomnia, and alcohol/substance abuse. Depression in adolescent girls is correlated with becoming sexually active at a younger age, failure to use contraception, having an STI, and suicide attempts. Depressed boys are more likely to have unprotected intercourse and participate in physical fights.29 Depressed teens have a 2- to 3-fold greater risk for behavioral disorders, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).30

Continue to: Suicide

Suicide. Among individuals 15 to 29 years of age, suicide is the second leading cause of death globally, with an annual incidence of 11 to 15 per 100,000.31 Suicide attempts are 10 to 20 times more common than completed suicide.31 Males are more likely than females to die by suicide,32 and boys with a history of attempted suicide have a 30-fold increased risk of subsequent successful suicide.31 Hanging, drug poisoning, and firearms (particularly for males) are the most common means of suicide in adolescents. More than half of adolescents dying by suicide have coexisting depression.31

Characteristics associated with suicidal behaviors in adolescents include impulsivity, poor problem-solving skills, and dichotomous thinking.31 There may be a genetic component as well. In 1 of 5 teenage suicides, a precipitating life event such as the break-up of a relationship, cyber-bullying, or peer rejection is felt to contribute.31

ADHD. The prevalence of ADHD is 7% to 9% in US school-aged children.33 Boys more commonly exhibit hyperactive behaviors, while girls have more inattention. Hyperactivity often diminishes in teens, but inattention and impulsivity persist. Sequelae of ADHD include high-risk sexual behaviors, motor vehicle accidents, incarceration, and substance abuse.34 Poor self-esteem, suicidal ideation, smoking, and obesity are also increased.34 ADHD often persists into adulthood, with implications for social relationships and job performance.34

Eating disorders. The distribution of eating disorders is now known to increasingly include more minorities and males, the latter representing 5% to 10% of cases.35 Eating disorders show a strong genetic tendency and appear to be accelerated by puberty. The most common eating disorder (diagnosed in 0.8%-14% of teens) is eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).35 Anorexia nervosa is diagnosed in 0.5% of adolescent girls, and bulimia nervosa in 1% to 2%—particularly among athletes and performers.35 Unanticipated loss of weight, amenorrhea, excessive concern about weight, and deceleration in height/weight curves are potential indicators of an eating disorder. When identified, eating disorders are best managed by a trusted family physician, acting as a coordinator of a multidisciplinary team.

Sexual health

Girls begin to menstruate at an average age of 12, and it takes about 4 years for them to reach reproductive maturity.36 Puberty has been documented to start at younger ages over the past 30 years, likely due to an increase in average body mass index and a decrease in levels of physical activity.37 Girls with early maturation are often insecure and self-conscious, with higher levels of psychological distress.38 In boys, the average age for spermarche (first ejaculation) is 13.39 Boys who mature early tend to be taller, be more confident, and express a good body image.40 Those who have early puberty are more likely to be sexually active or participate in high-risk behaviors.41

Continue to: Pregnancy and contraception

Pregnancy and contraception

Over the past several decades, more US teens have been abstaining from sexual intercourse or have been using effective forms of birth control, particularly condoms and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs).42 Teenage birth rates in girls ages 15 to 19 have declined significantly since the 1980s.42 Despite this, the teenage birth rate in the United States remains higher than in other industrialized nations, and most teen pregnancies are unintended.

There are numerous interventions to reduce teen pregnancy, including sex education, contraceptive counseling, the use of mobile apps that track a user’s monthly fertility cycle or issue reminders to take oral contraceptives,45 and the liberal distribution of contraceptives and condoms. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project shows that providing free (or low-cost) LARCs influences young women to choose these as their preferred contraceptive method.46 Other programs specifically empower girls to convince partners to use condoms and to resist unwanted sexual advances or intimate partner violence.

Adolescents prefer to have their health care providers address the topic of sexual health. Teens are more likely to share information with providers if asked directly about sexual behaviors.47TABLE 24,5 offers tips for anticipatory guidance and potential ways to frame questions with adolescents in this context. State laws vary with regard to the ability of minors to seek contraception, pregnancy testing, or care/screening for STIs without parental consent. Contraceptive counseling combined with effective screening decrease the incidence of STIs and pelvic inflammatory disease for sexually active teens.48

Sexually transmitted infections

Young adolescents often have a limited ability to imagine consequences related to specific actions. In general, there is also an increased desire to engage in experimental behaviors as an expression of developing autonomy, which may expose them to STIs. About half of all STIs contracted in the United States occur in individuals 15 to 24 years of age.49 Girls are at particular risk for the sequelae of these infections, including cervical dysplasia and infertility. Many teens erroneously believe that sexual activities other than intercourse decrease their risk of contracting an STI.50

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common STI in adolescence.51 In most cases, HPV is transient and asymptomatic. Oncogenic strains may cause cervical cancer or cancers of the anogenital or oropharyngeal systems. Due to viral latency, it is not recommended to perform HPV typing in men or in women younger than 30 years of age; however, Pap tests are recommended every 3 years for women ages 21 to 29. Primary care providers are pivotal in the public health struggle to prevent HPV infection.

Continue to: Universal immunization of all children...

Universal immunization of all children older than 11 years of age against HPV is strongly advised as part of routine well-child care. Emphasize the proven role of HPV vaccination in preventing cervical52 and oropharyngeal53 cancers. And be prepared to address concerns raised by parents in the context of vaccine safety and the initiation of sexual behaviors (www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/answering-questions.html).

Chlamydia is the second most common STI in the United States, usually occurring in individuals younger than 24.54 The CDC estimates that more than 3 million new chlamydial infections occur yearly. These infections are often asymptomatic, particularly in females, but may cause urethritis, cervicitis, epididymitis, proctitis, or pelvic inflammatory disease. Indolent chlamydial infection is the leading cause of tubal infertility in women.54 Routine annual screening for chlamydia is recommended for all sexually active females ≤ 25 years (and for older women with specific risks).55 Annual screening is also recommended for men who have sex with men (MSM).55

Chlamydial infection may be diagnosed with first-catch urine sampling (men or women), urethral swab (men), endocervical swab (women), or self-collected vaginal swab. Nucleic acid amplification testing is the most sensitive test that is widely available.56 First-line treatment includes either azithromycin (1 g orally, single dose) or doxycycline (100 mg orally, twice daily for 7 days).56

Gonorrhea. In 2018, there were more than 500,000 annual cases of gonorrhea, with the majority occurring in those between 15 and 24 years of age.57 Gonorrhea may increase rates of HIV infection transmission up to 5-fold.57 As more adolescents practice oral sex, cases of pharyngeal gonorrhea (and oropharyngeal HPV) have increased. Symptoms of urethritis occur more frequently in men. Screening is recommended for all sexually active women younger than 25.56 Importantly, the organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed significant antibiotic resistance over the past decade. The CDC currently recommends dual therapy for the treatment of gonorrhea using 250 mg of intramuscular ceftriaxone and 1 g of oral azithromycin.56

Syphilis. Rates of syphilis are increasing among individuals ages 15 to 24.51 Screening is particularly recommended for MSM and individuals infected with HIV. Benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM, remains the treatment of choice.56

Continue to: HIV

HIV. Globally, HIV impacts young people disproportionately. HIV infection also facilitates infection with other STIs. In the United States, the highest burden of HIV infection is borne by young MSM, with prevalence among those 18 to 24 years old varying between 26% to 30% (black) and 3% to 5.5% (non-Hispanic white).51 The use of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has recently been approved for the prevention of HIV. PrEP reduces risk by up to 92% for MSM and transgender women.58

Sexual identity

One in 10 high school students self-identifies as “nonheterosexual,” and 1 in 15 reports same-sex sexual contact.59 The term LGBTQ+ includes the communities of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, questioning, intersex, and asexual individuals. Developing a safe sense of sexual identity is fundamental to adolescent psychological development, and many adolescents struggle to develop a positive sexual identity. Suicide rates and self-harm behaviors among LGBTQ+ adolescents can be 4 times higher than among their heterosexual peers.60 Rates of mood disorders, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors are also increased in the LGBTQ+ population.61

The LGBTQ+ community often seeks health care advice and affirmation from primary care providers. Resources to enhance this care are available at www.lgbthealtheducation.org.

Social media

Adolescents today have more media exposure than any prior generation, with smartphone and computer use increasing exponentially. Most (95%) teens have access to a smartphone,62 45% describe themselves as constantly connected to the Internet, and 14% feel that social media is “addictive.”62 Most manage their social media portfolio on multiple sites. Patterns of adolescents' online activities show that boys prefer online gaming, while girls tend to spend more time on social networking.62

Whether extensive media use is psychologically beneficial or deleterious has been widely debated. Increased time online correlates with decreased levels of physical activity.63 And sleep disturbances have been associated with excessive screen time and the presence of mobile devices in the bedroom.64 The use of social media prior to bedtime also has an adverse impact on academic performance—particularly for girls. This adverse impact on academics persists after correcting for daytime sleepiness, body mass index, and number of hours spent on homework.64

Continue to: Due to growing concerns...

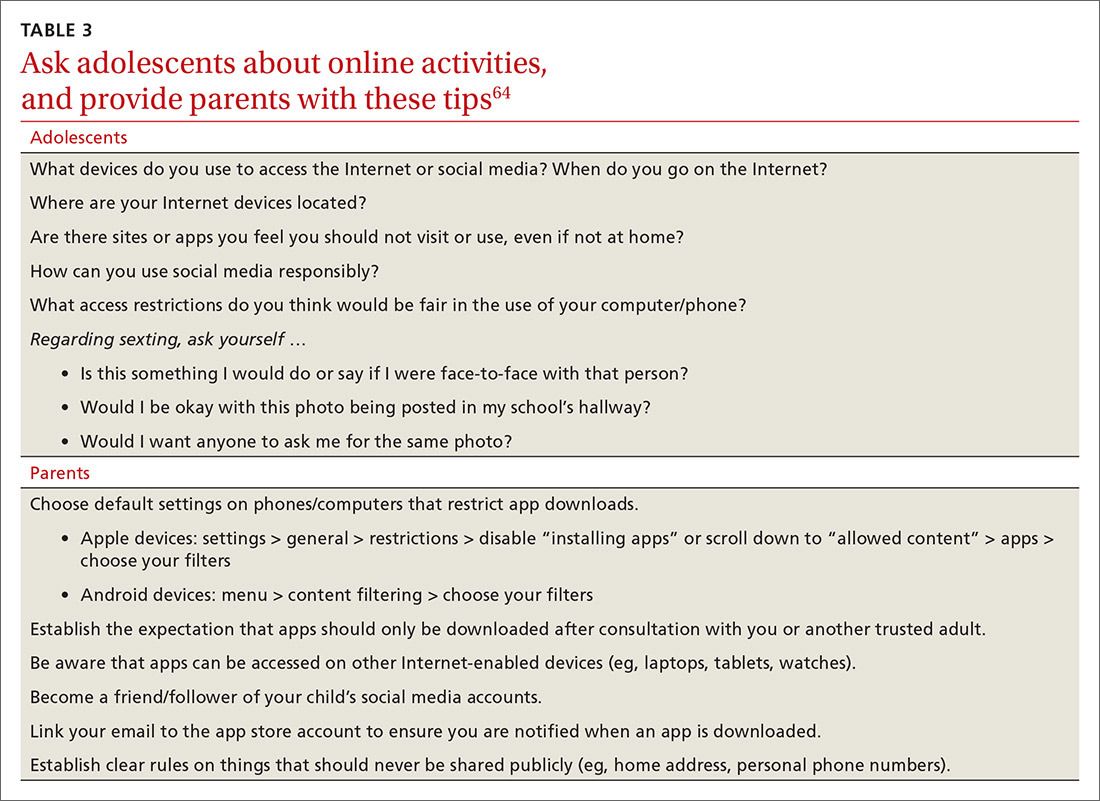

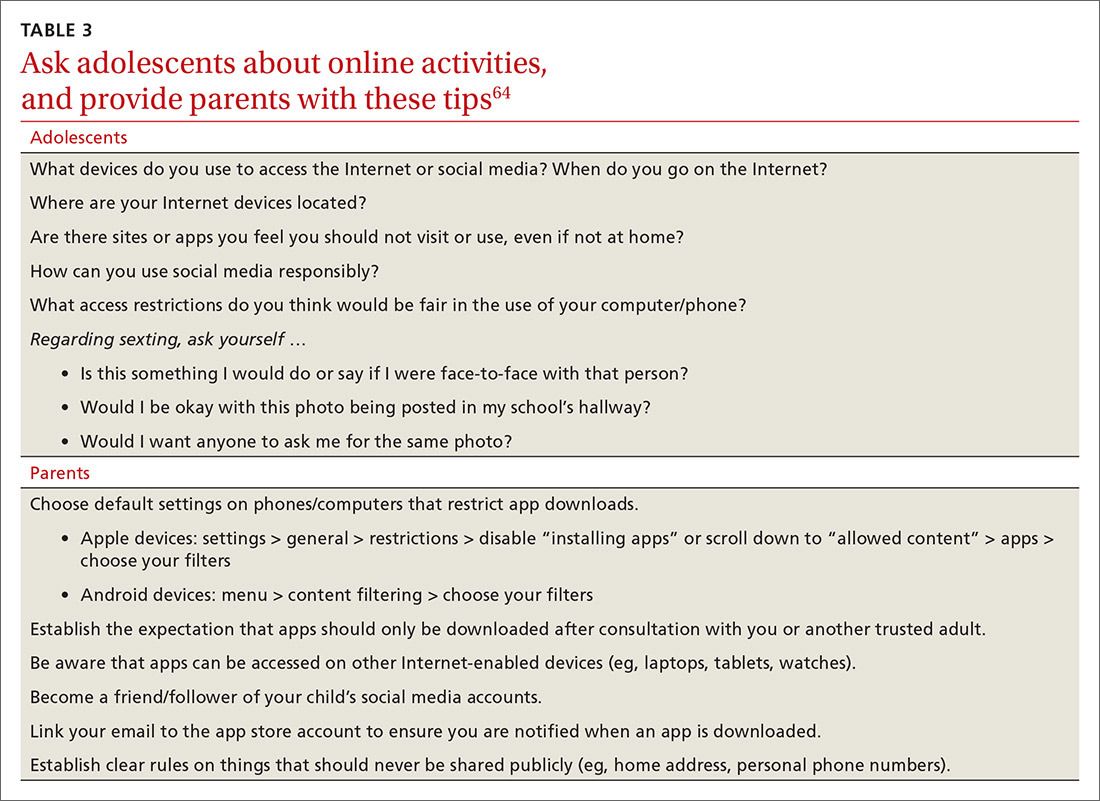

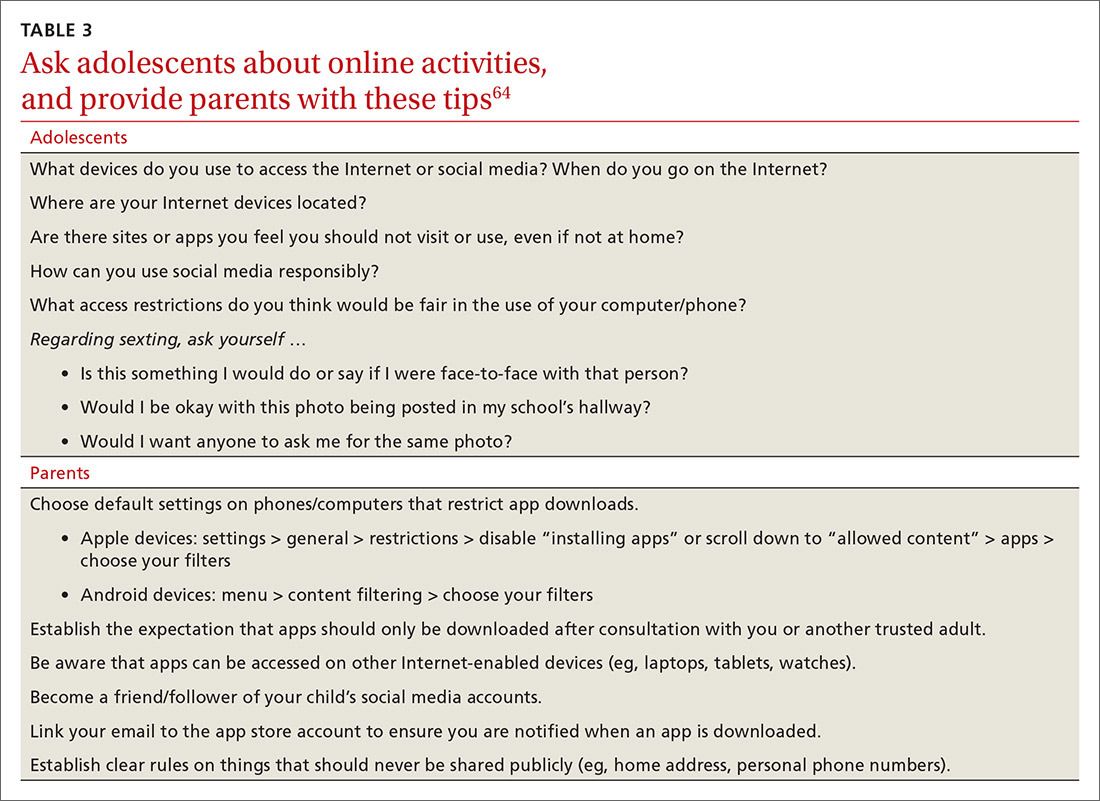

Due to growing concerns about the risks of social media in children and adolescents, the American Academy of Pediatrics has developed the Family Media Plan (www.healthychildren.org/English/media/Pages/default.aspx). Some specific questions that providers may ask are outlined in TABLE 3.64 The Family Media Plan can provide age-specific guidelines to assist parents or caregivers in answering these questions.

Cyber-bullying. One in 3 adolescents (primarily female) has been a victim of cyber-bullying.65 Sadly, 1 in 5 teens has received some form of electronic sexual solicitation.66 The likelihood of unsolicited stranger contact correlates with teens’ online habits and the amount of information disclosed. Predictors include female sex, visiting chat rooms, posting photos, and disclosing personal information. Restricting computer use to an area with parental supervision or installing monitoring programs does not seem to exert any protective influence on cyber-bullying or unsolicited stranger contact.65 While 63% of cyber-bullying victims feel upset, embarrassed, or stressed by these contacts,66 few events are actually reported. To address this, some states have adopted laws adding cyber-bullying to school disciplinary codes.

Negative health impacts associated with cyber-bullying include anxiety, sadness, and greater difficulty in concentrating on school work.65 Victims of bullying are more likely to have school disciplinary actions and depression and to be truant or to carry weapons to school.66 Cyber-bullying is uniquely destructive due to its ubiquitous presence. A sense of relative anonymity online may encourage perpetrators to act more cruelly, with less concern for punishment.

Young people are also more likely to share passwords as a sign of friendship. This may result in others assuming their identity online. Adolescents rarely disclose bullying to parents or other adults, fearing restriction of Internet access, and many of them think that adults may downplay the seriousness of the events.66

CORRESPONDENCE

Mark B. Stephens, MD, Penn State Health Medical Group, 1850 East Park Avenue, State College, PA 16803; [email protected].

1. World Health Organization. Adolescent health. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/adolescence/en/

2. Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, et al. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2:223-228.

3. Pathak PR, Chou A. Confidential care for adoloscents in the U.S. healthcare system. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2019;6:46-50.

4. AMA Journal of Ethics. HEADSS: the “review of systems” for adolescents. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/headss-review-systems-adolescents/2005-03

5. Cohen E, MacKenzie RG, Yates GL. HEADSS, a psychosocial risk assessment instrument: implications for designing effective intervention programs for runaway youth. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12:539-544.

6. Possibilities for Change. Rapid Adolescent Prevention Screening (RAAPS). Accessed February 23, 2021. www.possibilitiesforchange.com/raaps/

7. Elster AB, Kuznets NJ. AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS): Recommendations and Rationale. Williams & Wilkins; 1994.

8. AAP. Engaging patients and families - periodicity schedule. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/practice-support/Pages/PeriodicitySchedule.aspx

9. Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Eng J Med. 2018;379:2468-2475.

10. Schuster MA, Franke TM, Bastian AM, et al. Firearm storage patterns in US homes with children. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:588-594.

11. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1245.

12. HHS. Health consequences of smoking, surgeon general fact sheet. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/tobacco/consequences-smoking-factsheet/index.html

13. Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the future: national survey results on drug use, 1975-2017. The University of Michigan. 2018. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED589762

14. US Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

15. HHS. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: HHS, CDC, NCCDPHP, OSH; 2012. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/

16. NIH. Alcohol screening and brief intervention for youth: a pocket guide. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/YouthGuide/YouthGuidePocket.pdf

17. Gorey C, Kuhns L, Smaragdi E, et al. Age-related differences in the impact of cannabis use on the brain and cognition: a systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:37-58.

18. Secades-Villa R, Garcia-Rodriguez O, Jin CJ, et al. Probability and predictors of the cannabis gateway effect: a national study. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26:135-142.

19. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67:1-114.

20. NIH. Drug overdoses in youth. How do drug overdoses happen?. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://teens.drugabuse.gov/drug-facts/drug-overdoses-youth

21. Branstetter SA, Low S, Furman W. The influence of parents and friends on adolescent substance use: a multidimensional approach. J Subst Use. 2011;162:150-160.

22. AAP. Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161210.

23. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;288:1-8.

24. Halfon N, Larson K, Slusser W. Associations between obesity and comorbid mental health, developmental and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample of US children aged 10 to 17. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:6-13.

25. Griffiths LJ, Parsons TJ, Hill AJ. Self-esteem and quality of life in obese children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:282-304.

26. National Physical Activity Plan Alliance. The 2018 United States report card on physical activity for children and youth. Accessed February 23, 2021. http://physicalactivityplan.org/projects/PA/2018/2018%20US%20Report%20Card%20Full%20Version_WEB.PDF?pdf=page-link

27. HHS. NIMH. Child and adolescent mental health. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/child-and-adolescent-mental-health/index.shtml

28. Yonek JC, Jordan N, Dunlop D, et al. Patient-centered medical home care for adolescents in need of mental health treatment. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:172-180.

29. Brooks TL, Harris SK, Thrall JS, et al. Association of adolescent risk behaviors with mental health symptoms in high school students. |J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:240-246.

30. Weller BE, Blanford KL, Butler AM. Estimated prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities in US adolescents with depression by race/ethnicity, 2011-2012. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62:716-721.

31. Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:540.

32. Shain B, AAP Committee on Adolescence. Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161420.

33. Brahmbhatt K, Hilty DM, Hah M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during adolescence in the primary care setting: review and future directions. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:135-143.

34. Bravender T. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disordered eating. [editorial] J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:125-126.

35. Rosen DS, AAP Committee on Adolescence. Identification and management of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1240-1253.

36. Susman EJ, Houts RM, Steinberg L, et al. Longitudinal development of secondary sexual characteristics in girls and boys between ages 9 ½ and 15 ½ years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:166-173.

37. Kaplowitz PB. Link between body fat and the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121(suppl 3):S208-S217.

38. Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of age too early: pubertal influences on girl’s vulnerability to psychologic distress. Child Dev. 1996;67:3386-3400.

39. Jørgensen M, Keiding N, Skakkebaek NE. Estimation of spermarche from longitudinal spermaturia data. Biometrics. 1991;47:177-193.

40. Kar SK, Choudhury A, Singh AP. Understanding normal development of adolescent sexuality: a bumpy ride. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2015;8:70-74.

41. Susman EJ, Dorn LD, Schiefelbein VL. Puberty, sexuality and health. In: Lerner MA, Easterbrooks MA, Mistry J (eds). Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology. Wiley; 2003.

42. Lindberg LD, Santelli JS, Desai S. Changing patterns of contraceptive use and the decline in rates of pregnancy and birth among U.S. adolescents, 2007-2014. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:253-256.

43. Guttmacher Institute. Teen pregnancy. www.guttmacher.org/united-states/teens/teen-pregnancy. Accessed February 23, 2021.

44. CDC. Social determinants and eliminating disparities in teen pregnancy. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.cdc.gov/teenpregnancy/about/social-determinants-disparities-teen-pregnancy.htm

45. Widman L, Nesi J, Kamke K, et al. Technology-based interventions to reduce sexually transmitted infection and unintended pregnancy among youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62:651-660.

46. Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, et al. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:115.e1-115.e7.

47. Ham P, Allen C. Adolescent health screening and counseling. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:1109-1116.

48. ACOG. Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Adolescent pregnancy, contraception and sexual activity. 2017. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2017/05/adolescent-pregnancy-contraception-and-sexual-activity

49. Wangu Z, Burstein GR. Adolescent sexuality: updates to the sexually transmitted infection guidelines. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2017;64:389-411.

50. Holway GV, Hernandez SM. Oral sex and condom use in a U.S. national sample of adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62:402-410.

51. CDC. STDs in adults and adolescents. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/adolescents.htm

52. McClung N, Gargano J, Bennett N, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008-2014. Accessed February 23, 2021. https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/28/3/602

53. Timbang MR, Sim MW, Bewley AF, et al. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer: a review on burden of the disease and opportunities for prevention and early detection. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1920-1928.

54. Carey AJ, Beagley KW. Chlamydia trachomatis, a hidden epidemic: effects on female reproduction and options for treatment. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:576-586.

55. USPSTF. Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

56. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1-135.

57. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/gonorrhea.htm

5

59. Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65:1-174.

60. CDC. LGBT youth. Accessed February 23, 2021. www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/youth.htm

61. Johns MM, Lowry R, Rasberry CN, et al. Violence victimization, substance use, and suicide risk among sexual minority high school students – United States, 2015-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1211-1215.

62. Pew Research Center. Teens, social media & technology 2018. . Accessed February 23, 2021. www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

63. Chassiakos YLR, Radesky J, Christakis D, et al. Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20162593.

64. Arora T, Albahri A, Omar OM, et al. The prospective association between electronic device use before bedtime and academic attainment in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:451-458.

65. Mishna F, Saini M, Solomon S. Ongoing and online: children and youth’s perceptions of cyber bullying. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2009;31:1222-1228.

66. Sengupta A, Chaudhuri A. Are social networking sites a source of online harassment for teens? Evidence from survey data. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2011;33:284-290.

Adolescents are an increasingly diverse population reflecting changes in the racial, ethnic, and geopolitical milieus of the United States. The World Health Organization classifies adolescence as ages 10 to 19 years.1 However, given the complexity of adolescent development physically, behaviorally, emotionally, and socially, others propose that adolescence may extend to age 24.2

Recognizing the specific challenges adolescents face is key to providing comprehensive longitudinal health care. Moreover, creating an environment of trust helps to ensure open 2-way communication that can facilitate anticipatory guidance.

Our review focuses on common adolescent issues, including injury from vehicles and firearms, tobacco and substance misuse, obesity, behavioral health, sexual health, and social media use. We discuss current trends and recommend strategies to maximize health and wellness.

Start by framing the visit

Confidentiality

Laws governing confidentiality in adolescent health care vary by state. Be aware of the laws pertaining to your practice setting. In addition, health care facilities may have their own policies regarding consent and confidentiality in adolescent care. Discuss confidentiality with both an adolescent and the parent/guardian at the initial visit. And, to help avoid potential misunderstandings, let them know in advance what will (and will not) be divulged.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has developed a useful tip sheet regarding confidentiality laws (www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Documents/Confidentiality_Laws.pdf). Examples of required (conditional) disclosure include abuse and suicidal or homicidal ideations. Patients should understand that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are reportable to public health authorities and that potentially injurious behaviors to self or others (eg, excessive drinking prior to driving) may also warrant disclosure(TABLE 13).

Privacy and general visit structure

Create a safe atmosphere where adolescents can discuss personal issues without fear of repercussion or judgment. While parents may prefer to be present during the visit, allowing for time to visit independently with an adolescent offers the opportunity to reinforce issues of privacy and confidentiality. Also discuss your office policies regarding electronic communication, phone communication, and relaying test results.

A useful paradigm for organizing a visit for routine adolescent care is to use an expanded version of the HEADSS mnemonic (TABLE 24,5), which includes questions about an adolescent’s Home, Education, Activities, Drug and alcohol use, Sexual behavior, Suicidality and depression, and other topics. Other validated screening tools include RAAPS (Rapid Adolescent Prevention Screening)6 (www.possibilitiesforchange.com/raaps/); the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services7; and the Bright Futures recommendations for preventive care from the American Academy of Pediatrics.8 Below, we consider important topics addressed with the HEADSS approach.

Continue to: Injury from vehicles and firearms

Injury from vehicles and firearms

Motor vehicle accidents and firearm wounds are the 2 leading causes of adolescent injury. In 2016, of the more than 20,000 deaths in children and adolescents (ages 1-19 years), 20% were due to motor vehicle accidents (4074) and 15% were a result of firearm-related injuries (3143). Among firearm-related deaths, 60% were homicides, 35% were suicides, and 4% were due to accidental discharge.9 The rate of firearm-related deaths among American teens is 36 times greater than that of any other developed nation.9 Currently, 1 of every 3 US households with children younger than 18 has a firearm. Data suggest that in 43% of these households, the firearm is loaded and kept in an unlocked location.10

To aid anticipatory guidance, ask adolescents about firearm and seat belt use, drinking and driving, and suicidal thoughts (TABLE 24,5). Advise them to always wear seat belts whether driving or riding as a passenger. They should never drink and drive (or get in a car with someone who has been drinking). Advise parents that if firearms are present in the household, they should be kept in a secure, locked location. Weapons should be separated from ammunition and safety mechanisms should be engaged on all devices.

Tobacco and substance misuse

Tobacco use, the leading preventable cause of death in the United States,11 is responsible for more deaths than alcohol, motor vehicle accidents, suicides, homicides, and HIV disease combined.12 Most tobacco-associated mortality occurs in individuals who began smoking before the age of 18.12 Individuals who start smoking early are also more likely to continue smoking through adulthood.

Encouragingly, tobacco use has declined significantly among adolescents over the past several decades. Roughly 1 in 25 high school seniors reports daily tobacco use.13 Adolescent smoking behaviors are also changing dramatically with the increasing popularity of electronic cigarettes (“vaping”). Currently, more adolescents vape than smoke cigarettes.13 Vaping has additional health risks including toxic lung injury.

Multiple resources can help combat tobacco and nicotine use in adolescents. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians intervene through education or brief counselling to prevent initiation of tobacco use in school-aged children and adolescents.14 Ask teens about tobacco and electronic cigarette use and encourage them to quit when use is acknowledged. Other helpful office-based tools are the “Quit Line” 800-QUIT-NOW and texting “Quit” to 47848. Smokefree teen (https://teen.smokefree.gov/) is a website that reviews the risks of tobacco and nicotine use and provides age-appropriate cessation tools and tips (including a smartphone app and a live-chat feature). Other useful information is available in a report from the Surgeon General on preventing tobacco use among young adults.15

Continue to: Alcohol use

Alcohol use. Three in 5 high school students report ever having used alcohol.13 As with tobacco, adolescent alcohol use has declined over the past decade. However, binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks on 1 occasion for males; ≥ 4 drinks on 1 occasion for females) remains a common high-risk behavior among adolescents (particularly college students). Based on the Monitoring the Future Survey, 1 in 6 high school seniors reported binge drinking in the past 2 weeks.13 While historically more common among males, rates of binge drinking are now basically similar between male and female adolescents.13

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has a screening and intervention guide specifically for adolescents.16

Illicit drug use. Half of adolescents report using an illicit drug by their senior year in high school.13 Marijuana is the most commonly used substance, and laws governing its use are rapidly changing across the United States. Marijuana is illegal in 10 states and legal in 10 states (and the District of Columbia). The remaining states have varying policies on the medical use of marijuana and the decriminalization of marijuana. In addition, cannabinoid (CBD) products are increasingly available. Frequent cannabis use in adolescence has an adverse impact on general executive function (compared with adult users) and learning.17 Marijuana may serve as a gateway drug in the abuse of other substances,18 and its use should be strongly discouraged in adolescents.

Of note, there has been a sharp rise in the illicit use of prescription drugs, particularly opioids, creating a public health emergency across the United States.19 In 2015, more than 4000 young people, ages 15 to 24, died from a drug-related overdose (> 50% of these attributable to opioids).20 Adolescents with a history of substance abuse and behavioral illness are at particular risk. Many adolescents who misuse opioids and other prescription drugs obtain them from friends and relatives.21

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommends universal screening of adolescents for substance abuse. This screening should be accompanied by a brief intervention to prevent, mitigate, or eliminate substance use, or a referral to appropriate treatment sources. This process of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is recommended as part of routine health care.22

Continue to: Obesity and physical activity

Obesity and physical activity

The percentage of overweight and obese adolescents in the United States has more than tripled over the past 40 years,23 and 1 in 5 US adolescents is obese.23 Obese teens are at higher risk for multiple chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and heart disease.24 They are also more likely to be bullied and to have poor self-esteem.25 Only 1 in 5 American high school students engages in 60 or more minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on 5 or more days per week.26

Regular physical activity is, of course, beneficial for cardiorespiratory fitness, bone health, weight control, and improved indices of behavioral health.26 Adolescents who are physically active consistently demonstrate better school attendance and grades.17 Higher levels of physical fitness are also associated with improved overall cognitive performance.24

General recommendations. The Department of Health and Human Services recommends that adolescents get at least 60 minutes of mostly moderate physical activity every day.26 Encourage adolescents to engage in vigorous physical activity (heavy breathing, sweating) at least 3 days a week. As part of their physical activity patterns, adolescents should also engage in muscle-strengthening and bone-strengthening activities on at least 3 days per week.

Behavioral health

As young people develop their sense of personal identity, they also strive for independence. It can be difficult, at times, to differentiate normal adolescent rebellion from true mental illness. An estimated 17% to 19% of adolescents meet criteria for mental illness, and about 7% have a severe psychiatric disorder.27 Only one-third of adolescents with mental illness receive any mental health services.28

Depression. The 1-year incidence of major depression in adolescents is 3% to 4%, and the lifetime prevalence of depressive symptoms is 25% in all high school students.27 Risk factors include ethnic minority status, poor self-esteem, poor health, recent personal crisis, insomnia, and alcohol/substance abuse. Depression in adolescent girls is correlated with becoming sexually active at a younger age, failure to use contraception, having an STI, and suicide attempts. Depressed boys are more likely to have unprotected intercourse and participate in physical fights.29 Depressed teens have a 2- to 3-fold greater risk for behavioral disorders, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).30

Continue to: Suicide

Suicide. Among individuals 15 to 29 years of age, suicide is the second leading cause of death globally, with an annual incidence of 11 to 15 per 100,000.31 Suicide attempts are 10 to 20 times more common than completed suicide.31 Males are more likely than females to die by suicide,32 and boys with a history of attempted suicide have a 30-fold increased risk of subsequent successful suicide.31 Hanging, drug poisoning, and firearms (particularly for males) are the most common means of suicide in adolescents. More than half of adolescents dying by suicide have coexisting depression.31

Characteristics associated with suicidal behaviors in adolescents include impulsivity, poor problem-solving skills, and dichotomous thinking.31 There may be a genetic component as well. In 1 of 5 teenage suicides, a precipitating life event such as the break-up of a relationship, cyber-bullying, or peer rejection is felt to contribute.31

ADHD. The prevalence of ADHD is 7% to 9% in US school-aged children.33 Boys more commonly exhibit hyperactive behaviors, while girls have more inattention. Hyperactivity often diminishes in teens, but inattention and impulsivity persist. Sequelae of ADHD include high-risk sexual behaviors, motor vehicle accidents, incarceration, and substance abuse.34 Poor self-esteem, suicidal ideation, smoking, and obesity are also increased.34 ADHD often persists into adulthood, with implications for social relationships and job performance.34

Eating disorders. The distribution of eating disorders is now known to increasingly include more minorities and males, the latter representing 5% to 10% of cases.35 Eating disorders show a strong genetic tendency and appear to be accelerated by puberty. The most common eating disorder (diagnosed in 0.8%-14% of teens) is eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).35 Anorexia nervosa is diagnosed in 0.5% of adolescent girls, and bulimia nervosa in 1% to 2%—particularly among athletes and performers.35 Unanticipated loss of weight, amenorrhea, excessive concern about weight, and deceleration in height/weight curves are potential indicators of an eating disorder. When identified, eating disorders are best managed by a trusted family physician, acting as a coordinator of a multidisciplinary team.

Sexual health

Girls begin to menstruate at an average age of 12, and it takes about 4 years for them to reach reproductive maturity.36 Puberty has been documented to start at younger ages over the past 30 years, likely due to an increase in average body mass index and a decrease in levels of physical activity.37 Girls with early maturation are often insecure and self-conscious, with higher levels of psychological distress.38 In boys, the average age for spermarche (first ejaculation) is 13.39 Boys who mature early tend to be taller, be more confident, and express a good body image.40 Those who have early puberty are more likely to be sexually active or participate in high-risk behaviors.41

Continue to: Pregnancy and contraception

Pregnancy and contraception

Over the past several decades, more US teens have been abstaining from sexual intercourse or have been using effective forms of birth control, particularly condoms and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs).42 Teenage birth rates in girls ages 15 to 19 have declined significantly since the 1980s.42 Despite this, the teenage birth rate in the United States remains higher than in other industrialized nations, and most teen pregnancies are unintended.

There are numerous interventions to reduce teen pregnancy, including sex education, contraceptive counseling, the use of mobile apps that track a user’s monthly fertility cycle or issue reminders to take oral contraceptives,45 and the liberal distribution of contraceptives and condoms. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project shows that providing free (or low-cost) LARCs influences young women to choose these as their preferred contraceptive method.46 Other programs specifically empower girls to convince partners to use condoms and to resist unwanted sexual advances or intimate partner violence.

Adolescents prefer to have their health care providers address the topic of sexual health. Teens are more likely to share information with providers if asked directly about sexual behaviors.47TABLE 24,5 offers tips for anticipatory guidance and potential ways to frame questions with adolescents in this context. State laws vary with regard to the ability of minors to seek contraception, pregnancy testing, or care/screening for STIs without parental consent. Contraceptive counseling combined with effective screening decrease the incidence of STIs and pelvic inflammatory disease for sexually active teens.48

Sexually transmitted infections

Young adolescents often have a limited ability to imagine consequences related to specific actions. In general, there is also an increased desire to engage in experimental behaviors as an expression of developing autonomy, which may expose them to STIs. About half of all STIs contracted in the United States occur in individuals 15 to 24 years of age.49 Girls are at particular risk for the sequelae of these infections, including cervical dysplasia and infertility. Many teens erroneously believe that sexual activities other than intercourse decrease their risk of contracting an STI.50

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common STI in adolescence.51 In most cases, HPV is transient and asymptomatic. Oncogenic strains may cause cervical cancer or cancers of the anogenital or oropharyngeal systems. Due to viral latency, it is not recommended to perform HPV typing in men or in women younger than 30 years of age; however, Pap tests are recommended every 3 years for women ages 21 to 29. Primary care providers are pivotal in the public health struggle to prevent HPV infection.

Continue to: Universal immunization of all children...

Universal immunization of all children older than 11 years of age against HPV is strongly advised as part of routine well-child care. Emphasize the proven role of HPV vaccination in preventing cervical52 and oropharyngeal53 cancers. And be prepared to address concerns raised by parents in the context of vaccine safety and the initiation of sexual behaviors (www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/answering-questions.html).

Chlamydia is the second most common STI in the United States, usually occurring in individuals younger than 24.54 The CDC estimates that more than 3 million new chlamydial infections occur yearly. These infections are often asymptomatic, particularly in females, but may cause urethritis, cervicitis, epididymitis, proctitis, or pelvic inflammatory disease. Indolent chlamydial infection is the leading cause of tubal infertility in women.54 Routine annual screening for chlamydia is recommended for all sexually active females ≤ 25 years (and for older women with specific risks).55 Annual screening is also recommended for men who have sex with men (MSM).55

Chlamydial infection may be diagnosed with first-catch urine sampling (men or women), urethral swab (men), endocervical swab (women), or self-collected vaginal swab. Nucleic acid amplification testing is the most sensitive test that is widely available.56 First-line treatment includes either azithromycin (1 g orally, single dose) or doxycycline (100 mg orally, twice daily for 7 days).56

Gonorrhea. In 2018, there were more than 500,000 annual cases of gonorrhea, with the majority occurring in those between 15 and 24 years of age.57 Gonorrhea may increase rates of HIV infection transmission up to 5-fold.57 As more adolescents practice oral sex, cases of pharyngeal gonorrhea (and oropharyngeal HPV) have increased. Symptoms of urethritis occur more frequently in men. Screening is recommended for all sexually active women younger than 25.56 Importantly, the organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed significant antibiotic resistance over the past decade. The CDC currently recommends dual therapy for the treatment of gonorrhea using 250 mg of intramuscular ceftriaxone and 1 g of oral azithromycin.56

Syphilis. Rates of syphilis are increasing among individuals ages 15 to 24.51 Screening is particularly recommended for MSM and individuals infected with HIV. Benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM, remains the treatment of choice.56

Continue to: HIV

HIV. Globally, HIV impacts young people disproportionately. HIV infection also facilitates infection with other STIs. In the United States, the highest burden of HIV infection is borne by young MSM, with prevalence among those 18 to 24 years old varying between 26% to 30% (black) and 3% to 5.5% (non-Hispanic white).51 The use of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has recently been approved for the prevention of HIV. PrEP reduces risk by up to 92% for MSM and transgender women.58

Sexual identity

One in 10 high school students self-identifies as “nonheterosexual,” and 1 in 15 reports same-sex sexual contact.59 The term LGBTQ+ includes the communities of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, questioning, intersex, and asexual individuals. Developing a safe sense of sexual identity is fundamental to adolescent psychological development, and many adolescents struggle to develop a positive sexual identity. Suicide rates and self-harm behaviors among LGBTQ+ adolescents can be 4 times higher than among their heterosexual peers.60 Rates of mood disorders, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors are also increased in the LGBTQ+ population.61

The LGBTQ+ community often seeks health care advice and affirmation from primary care providers. Resources to enhance this care are available at www.lgbthealtheducation.org.

Social media

Adolescents today have more media exposure than any prior generation, with smartphone and computer use increasing exponentially. Most (95%) teens have access to a smartphone,62 45% describe themselves as constantly connected to the Internet, and 14% feel that social media is “addictive.”62 Most manage their social media portfolio on multiple sites. Patterns of adolescents' online activities show that boys prefer online gaming, while girls tend to spend more time on social networking.62

Whether extensive media use is psychologically beneficial or deleterious has been widely debated. Increased time online correlates with decreased levels of physical activity.63 And sleep disturbances have been associated with excessive screen time and the presence of mobile devices in the bedroom.64 The use of social media prior to bedtime also has an adverse impact on academic performance—particularly for girls. This adverse impact on academics persists after correcting for daytime sleepiness, body mass index, and number of hours spent on homework.64

Continue to: Due to growing concerns...

Due to growing concerns about the risks of social media in children and adolescents, the American Academy of Pediatrics has developed the Family Media Plan (www.healthychildren.org/English/media/Pages/default.aspx). Some specific questions that providers may ask are outlined in TABLE 3.64 The Family Media Plan can provide age-specific guidelines to assist parents or caregivers in answering these questions.

Cyber-bullying. One in 3 adolescents (primarily female) has been a victim of cyber-bullying.65 Sadly, 1 in 5 teens has received some form of electronic sexual solicitation.66 The likelihood of unsolicited stranger contact correlates with teens’ online habits and the amount of information disclosed. Predictors include female sex, visiting chat rooms, posting photos, and disclosing personal information. Restricting computer use to an area with parental supervision or installing monitoring programs does not seem to exert any protective influence on cyber-bullying or unsolicited stranger contact.65 While 63% of cyber-bullying victims feel upset, embarrassed, or stressed by these contacts,66 few events are actually reported. To address this, some states have adopted laws adding cyber-bullying to school disciplinary codes.

Negative health impacts associated with cyber-bullying include anxiety, sadness, and greater difficulty in concentrating on school work.65 Victims of bullying are more likely to have school disciplinary actions and depression and to be truant or to carry weapons to school.66 Cyber-bullying is uniquely destructive due to its ubiquitous presence. A sense of relative anonymity online may encourage perpetrators to act more cruelly, with less concern for punishment.

Young people are also more likely to share passwords as a sign of friendship. This may result in others assuming their identity online. Adolescents rarely disclose bullying to parents or other adults, fearing restriction of Internet access, and many of them think that adults may downplay the seriousness of the events.66

CORRESPONDENCE

Mark B. Stephens, MD, Penn State Health Medical Group, 1850 East Park Avenue, State College, PA 16803; [email protected].

Adolescents are an increasingly diverse population reflecting changes in the racial, ethnic, and geopolitical milieus of the United States. The World Health Organization classifies adolescence as ages 10 to 19 years.1 However, given the complexity of adolescent development physically, behaviorally, emotionally, and socially, others propose that adolescence may extend to age 24.2

Recognizing the specific challenges adolescents face is key to providing comprehensive longitudinal health care. Moreover, creating an environment of trust helps to ensure open 2-way communication that can facilitate anticipatory guidance.

Our review focuses on common adolescent issues, including injury from vehicles and firearms, tobacco and substance misuse, obesity, behavioral health, sexual health, and social media use. We discuss current trends and recommend strategies to maximize health and wellness.

Start by framing the visit

Confidentiality

Laws governing confidentiality in adolescent health care vary by state. Be aware of the laws pertaining to your practice setting. In addition, health care facilities may have their own policies regarding consent and confidentiality in adolescent care. Discuss confidentiality with both an adolescent and the parent/guardian at the initial visit. And, to help avoid potential misunderstandings, let them know in advance what will (and will not) be divulged.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has developed a useful tip sheet regarding confidentiality laws (www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Documents/Confidentiality_Laws.pdf). Examples of required (conditional) disclosure include abuse and suicidal or homicidal ideations. Patients should understand that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are reportable to public health authorities and that potentially injurious behaviors to self or others (eg, excessive drinking prior to driving) may also warrant disclosure(TABLE 13).

Privacy and general visit structure

Create a safe atmosphere where adolescents can discuss personal issues without fear of repercussion or judgment. While parents may prefer to be present during the visit, allowing for time to visit independently with an adolescent offers the opportunity to reinforce issues of privacy and confidentiality. Also discuss your office policies regarding electronic communication, phone communication, and relaying test results.

A useful paradigm for organizing a visit for routine adolescent care is to use an expanded version of the HEADSS mnemonic (TABLE 24,5), which includes questions about an adolescent’s Home, Education, Activities, Drug and alcohol use, Sexual behavior, Suicidality and depression, and other topics. Other validated screening tools include RAAPS (Rapid Adolescent Prevention Screening)6 (www.possibilitiesforchange.com/raaps/); the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services7; and the Bright Futures recommendations for preventive care from the American Academy of Pediatrics.8 Below, we consider important topics addressed with the HEADSS approach.

Continue to: Injury from vehicles and firearms

Injury from vehicles and firearms

Motor vehicle accidents and firearm wounds are the 2 leading causes of adolescent injury. In 2016, of the more than 20,000 deaths in children and adolescents (ages 1-19 years), 20% were due to motor vehicle accidents (4074) and 15% were a result of firearm-related injuries (3143). Among firearm-related deaths, 60% were homicides, 35% were suicides, and 4% were due to accidental discharge.9 The rate of firearm-related deaths among American teens is 36 times greater than that of any other developed nation.9 Currently, 1 of every 3 US households with children younger than 18 has a firearm. Data suggest that in 43% of these households, the firearm is loaded and kept in an unlocked location.10

To aid anticipatory guidance, ask adolescents about firearm and seat belt use, drinking and driving, and suicidal thoughts (TABLE 24,5). Advise them to always wear seat belts whether driving or riding as a passenger. They should never drink and drive (or get in a car with someone who has been drinking). Advise parents that if firearms are present in the household, they should be kept in a secure, locked location. Weapons should be separated from ammunition and safety mechanisms should be engaged on all devices.

Tobacco and substance misuse

Tobacco use, the leading preventable cause of death in the United States,11 is responsible for more deaths than alcohol, motor vehicle accidents, suicides, homicides, and HIV disease combined.12 Most tobacco-associated mortality occurs in individuals who began smoking before the age of 18.12 Individuals who start smoking early are also more likely to continue smoking through adulthood.

Encouragingly, tobacco use has declined significantly among adolescents over the past several decades. Roughly 1 in 25 high school seniors reports daily tobacco use.13 Adolescent smoking behaviors are also changing dramatically with the increasing popularity of electronic cigarettes (“vaping”). Currently, more adolescents vape than smoke cigarettes.13 Vaping has additional health risks including toxic lung injury.

Multiple resources can help combat tobacco and nicotine use in adolescents. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians intervene through education or brief counselling to prevent initiation of tobacco use in school-aged children and adolescents.14 Ask teens about tobacco and electronic cigarette use and encourage them to quit when use is acknowledged. Other helpful office-based tools are the “Quit Line” 800-QUIT-NOW and texting “Quit” to 47848. Smokefree teen (https://teen.smokefree.gov/) is a website that reviews the risks of tobacco and nicotine use and provides age-appropriate cessation tools and tips (including a smartphone app and a live-chat feature). Other useful information is available in a report from the Surgeon General on preventing tobacco use among young adults.15

Continue to: Alcohol use

Alcohol use. Three in 5 high school students report ever having used alcohol.13 As with tobacco, adolescent alcohol use has declined over the past decade. However, binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks on 1 occasion for males; ≥ 4 drinks on 1 occasion for females) remains a common high-risk behavior among adolescents (particularly college students). Based on the Monitoring the Future Survey, 1 in 6 high school seniors reported binge drinking in the past 2 weeks.13 While historically more common among males, rates of binge drinking are now basically similar between male and female adolescents.13

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has a screening and intervention guide specifically for adolescents.16

Illicit drug use. Half of adolescents report using an illicit drug by their senior year in high school.13 Marijuana is the most commonly used substance, and laws governing its use are rapidly changing across the United States. Marijuana is illegal in 10 states and legal in 10 states (and the District of Columbia). The remaining states have varying policies on the medical use of marijuana and the decriminalization of marijuana. In addition, cannabinoid (CBD) products are increasingly available. Frequent cannabis use in adolescence has an adverse impact on general executive function (compared with adult users) and learning.17 Marijuana may serve as a gateway drug in the abuse of other substances,18 and its use should be strongly discouraged in adolescents.

Of note, there has been a sharp rise in the illicit use of prescription drugs, particularly opioids, creating a public health emergency across the United States.19 In 2015, more than 4000 young people, ages 15 to 24, died from a drug-related overdose (> 50% of these attributable to opioids).20 Adolescents with a history of substance abuse and behavioral illness are at particular risk. Many adolescents who misuse opioids and other prescription drugs obtain them from friends and relatives.21

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recommends universal screening of adolescents for substance abuse. This screening should be accompanied by a brief intervention to prevent, mitigate, or eliminate substance use, or a referral to appropriate treatment sources. This process of screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) is recommended as part of routine health care.22

Continue to: Obesity and physical activity

Obesity and physical activity

The percentage of overweight and obese adolescents in the United States has more than tripled over the past 40 years,23 and 1 in 5 US adolescents is obese.23 Obese teens are at higher risk for multiple chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea, and heart disease.24 They are also more likely to be bullied and to have poor self-esteem.25 Only 1 in 5 American high school students engages in 60 or more minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity on 5 or more days per week.26

Regular physical activity is, of course, beneficial for cardiorespiratory fitness, bone health, weight control, and improved indices of behavioral health.26 Adolescents who are physically active consistently demonstrate better school attendance and grades.17 Higher levels of physical fitness are also associated with improved overall cognitive performance.24

General recommendations. The Department of Health and Human Services recommends that adolescents get at least 60 minutes of mostly moderate physical activity every day.26 Encourage adolescents to engage in vigorous physical activity (heavy breathing, sweating) at least 3 days a week. As part of their physical activity patterns, adolescents should also engage in muscle-strengthening and bone-strengthening activities on at least 3 days per week.

Behavioral health

As young people develop their sense of personal identity, they also strive for independence. It can be difficult, at times, to differentiate normal adolescent rebellion from true mental illness. An estimated 17% to 19% of adolescents meet criteria for mental illness, and about 7% have a severe psychiatric disorder.27 Only one-third of adolescents with mental illness receive any mental health services.28

Depression. The 1-year incidence of major depression in adolescents is 3% to 4%, and the lifetime prevalence of depressive symptoms is 25% in all high school students.27 Risk factors include ethnic minority status, poor self-esteem, poor health, recent personal crisis, insomnia, and alcohol/substance abuse. Depression in adolescent girls is correlated with becoming sexually active at a younger age, failure to use contraception, having an STI, and suicide attempts. Depressed boys are more likely to have unprotected intercourse and participate in physical fights.29 Depressed teens have a 2- to 3-fold greater risk for behavioral disorders, anxiety, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).30

Continue to: Suicide

Suicide. Among individuals 15 to 29 years of age, suicide is the second leading cause of death globally, with an annual incidence of 11 to 15 per 100,000.31 Suicide attempts are 10 to 20 times more common than completed suicide.31 Males are more likely than females to die by suicide,32 and boys with a history of attempted suicide have a 30-fold increased risk of subsequent successful suicide.31 Hanging, drug poisoning, and firearms (particularly for males) are the most common means of suicide in adolescents. More than half of adolescents dying by suicide have coexisting depression.31

Characteristics associated with suicidal behaviors in adolescents include impulsivity, poor problem-solving skills, and dichotomous thinking.31 There may be a genetic component as well. In 1 of 5 teenage suicides, a precipitating life event such as the break-up of a relationship, cyber-bullying, or peer rejection is felt to contribute.31

ADHD. The prevalence of ADHD is 7% to 9% in US school-aged children.33 Boys more commonly exhibit hyperactive behaviors, while girls have more inattention. Hyperactivity often diminishes in teens, but inattention and impulsivity persist. Sequelae of ADHD include high-risk sexual behaviors, motor vehicle accidents, incarceration, and substance abuse.34 Poor self-esteem, suicidal ideation, smoking, and obesity are also increased.34 ADHD often persists into adulthood, with implications for social relationships and job performance.34

Eating disorders. The distribution of eating disorders is now known to increasingly include more minorities and males, the latter representing 5% to 10% of cases.35 Eating disorders show a strong genetic tendency and appear to be accelerated by puberty. The most common eating disorder (diagnosed in 0.8%-14% of teens) is eating disorder not otherwise specified (NOS).35 Anorexia nervosa is diagnosed in 0.5% of adolescent girls, and bulimia nervosa in 1% to 2%—particularly among athletes and performers.35 Unanticipated loss of weight, amenorrhea, excessive concern about weight, and deceleration in height/weight curves are potential indicators of an eating disorder. When identified, eating disorders are best managed by a trusted family physician, acting as a coordinator of a multidisciplinary team.

Sexual health

Girls begin to menstruate at an average age of 12, and it takes about 4 years for them to reach reproductive maturity.36 Puberty has been documented to start at younger ages over the past 30 years, likely due to an increase in average body mass index and a decrease in levels of physical activity.37 Girls with early maturation are often insecure and self-conscious, with higher levels of psychological distress.38 In boys, the average age for spermarche (first ejaculation) is 13.39 Boys who mature early tend to be taller, be more confident, and express a good body image.40 Those who have early puberty are more likely to be sexually active or participate in high-risk behaviors.41

Continue to: Pregnancy and contraception

Pregnancy and contraception

Over the past several decades, more US teens have been abstaining from sexual intercourse or have been using effective forms of birth control, particularly condoms and long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs).42 Teenage birth rates in girls ages 15 to 19 have declined significantly since the 1980s.42 Despite this, the teenage birth rate in the United States remains higher than in other industrialized nations, and most teen pregnancies are unintended.

There are numerous interventions to reduce teen pregnancy, including sex education, contraceptive counseling, the use of mobile apps that track a user’s monthly fertility cycle or issue reminders to take oral contraceptives,45 and the liberal distribution of contraceptives and condoms. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project shows that providing free (or low-cost) LARCs influences young women to choose these as their preferred contraceptive method.46 Other programs specifically empower girls to convince partners to use condoms and to resist unwanted sexual advances or intimate partner violence.

Adolescents prefer to have their health care providers address the topic of sexual health. Teens are more likely to share information with providers if asked directly about sexual behaviors.47TABLE 24,5 offers tips for anticipatory guidance and potential ways to frame questions with adolescents in this context. State laws vary with regard to the ability of minors to seek contraception, pregnancy testing, or care/screening for STIs without parental consent. Contraceptive counseling combined with effective screening decrease the incidence of STIs and pelvic inflammatory disease for sexually active teens.48

Sexually transmitted infections

Young adolescents often have a limited ability to imagine consequences related to specific actions. In general, there is also an increased desire to engage in experimental behaviors as an expression of developing autonomy, which may expose them to STIs. About half of all STIs contracted in the United States occur in individuals 15 to 24 years of age.49 Girls are at particular risk for the sequelae of these infections, including cervical dysplasia and infertility. Many teens erroneously believe that sexual activities other than intercourse decrease their risk of contracting an STI.50

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most common STI in adolescence.51 In most cases, HPV is transient and asymptomatic. Oncogenic strains may cause cervical cancer or cancers of the anogenital or oropharyngeal systems. Due to viral latency, it is not recommended to perform HPV typing in men or in women younger than 30 years of age; however, Pap tests are recommended every 3 years for women ages 21 to 29. Primary care providers are pivotal in the public health struggle to prevent HPV infection.

Continue to: Universal immunization of all children...

Universal immunization of all children older than 11 years of age against HPV is strongly advised as part of routine well-child care. Emphasize the proven role of HPV vaccination in preventing cervical52 and oropharyngeal53 cancers. And be prepared to address concerns raised by parents in the context of vaccine safety and the initiation of sexual behaviors (www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/answering-questions.html).

Chlamydia is the second most common STI in the United States, usually occurring in individuals younger than 24.54 The CDC estimates that more than 3 million new chlamydial infections occur yearly. These infections are often asymptomatic, particularly in females, but may cause urethritis, cervicitis, epididymitis, proctitis, or pelvic inflammatory disease. Indolent chlamydial infection is the leading cause of tubal infertility in women.54 Routine annual screening for chlamydia is recommended for all sexually active females ≤ 25 years (and for older women with specific risks).55 Annual screening is also recommended for men who have sex with men (MSM).55

Chlamydial infection may be diagnosed with first-catch urine sampling (men or women), urethral swab (men), endocervical swab (women), or self-collected vaginal swab. Nucleic acid amplification testing is the most sensitive test that is widely available.56 First-line treatment includes either azithromycin (1 g orally, single dose) or doxycycline (100 mg orally, twice daily for 7 days).56

Gonorrhea. In 2018, there were more than 500,000 annual cases of gonorrhea, with the majority occurring in those between 15 and 24 years of age.57 Gonorrhea may increase rates of HIV infection transmission up to 5-fold.57 As more adolescents practice oral sex, cases of pharyngeal gonorrhea (and oropharyngeal HPV) have increased. Symptoms of urethritis occur more frequently in men. Screening is recommended for all sexually active women younger than 25.56 Importantly, the organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae has developed significant antibiotic resistance over the past decade. The CDC currently recommends dual therapy for the treatment of gonorrhea using 250 mg of intramuscular ceftriaxone and 1 g of oral azithromycin.56

Syphilis. Rates of syphilis are increasing among individuals ages 15 to 24.51 Screening is particularly recommended for MSM and individuals infected with HIV. Benzathine penicillin G, 50,000 U/kg IM, remains the treatment of choice.56

Continue to: HIV

HIV. Globally, HIV impacts young people disproportionately. HIV infection also facilitates infection with other STIs. In the United States, the highest burden of HIV infection is borne by young MSM, with prevalence among those 18 to 24 years old varying between 26% to 30% (black) and 3% to 5.5% (non-Hispanic white).51 The use of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) has recently been approved for the prevention of HIV. PrEP reduces risk by up to 92% for MSM and transgender women.58

Sexual identity