User login

With the increasing complexity of health care policy, significant changes in reimbursement and payer sources, and constant push to improve the cost-efficiency of care delivery, there has been a growing focus on the importance of business knowledge and practice management (PM) skills among physicians. Family medicine was the first specialty to require PM training during residency; other specialities have begun implementing business training into their residency curriculum.1 In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) identified 6 core competencies that should be included in resident training. One of these core competencies involves training in health care systems and PM.2,3

Residency program directors have also recognized the need for business training among residents. One study that surveyed general surgery program directors found that more than 87% agreed that residents should be trained in business and PM.4 Although these directors recognized the need for training, they also acknowledged the current deficiency: more than 70% thought their current trainees were inadequately trained in business and PM. Similarly, residents and physicians in multiple specialties have reported significant deficiencies in their training and knowledge of PM and business principles.5-11 For example, in a recent survey of ophthalmologists who had been in practice less than 5 years, 70% reported being not very well or not at all trained in overall PM skills during residency.5 Yet, most respondents thought training in this area was the responsibility of the training program.

The call for more business and PM training during residency has been tempered by increasing demands on medical and surgical skills training and time limitations such as duty-hour restrictions. These limitations reinforce the need to find efficient and effective means of teaching necessary business knowledge and PM skills. Paramount to doing this is recognizing the difference between general knowledge and functional knowledge—essentially, what is specifically needed to function effectively in practice.

We conducted a study not only to determine the general level of knowledge that physicians have in different business and PM topics when they complete their residency, but also to evaluate the level of knowledge that graduating physicians need in different business and PM topics in order to function effectively in a medical practice. Toward this end, we developed a novel model that could help determine the level of the functional knowledge deficiency (FKD) of particular business topics. We thought this model would allow us to quantify how much knowledge physicians needed to acquire in a given topic in order to function effectively in practice. We hypothesized that graduating residents would report overall low levels of business knowledge and high FKDs.

Materials and Methods

To minimize variability in the specific type and amount of business training received, we focused this study on a single institution that had maintained a uniform business management curriculum over an extended period. The business training program provided to residents in the orthopedic surgery residency at this institution included 6 hours of didactic lectures on various business topics annually. This program has been in place for more than 15 years and has not undergone any significant changes during that time.

Using the program’s alumni directory, we emailed a cover letter and an 11-question survey to all 332 residents and fellows who had completed their residency or fellowship training at our institution between 1970 and 2008. Anyone who did not reply to the email was mailed a copy of the cover letter and the survey.

The first 4 survey questions involved the demographics of the surgeon and the surgeon’s practice. Subsequent questions focused on the surgeon’s understanding of 9 different general business and PM topics and their importance in the practice. The topics were marketing, business operations, human resources, contract negotiations, malpractice issues, coding/billing, medical records management, accounting, and economic analytical tools. The surgeon was asked to use a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (“knew nothing at all”) to 10 (“complete understanding”) to rate his or her understanding of each topic at the completion of residency. The surgeon was also asked to rate how important it was to understand that topic in the surgeon’s current practice. Again, a 10-point scale was used: 1 (“not important at all”) to 10 (“absolutely vital”) (Figure).

When the surveys were returned, their data were compiled and analyzed to determine the overall knowledge levels for each topic and the levels based on years in practice, type of practice, and level of involvement in PM. We also wanted to determine the amount of business knowledge that they needed in order to function effectively in practice (and that they lacked at time of graduation). We defined this as the FKD at graduation and calculated it as the difference between the surgeon’s reported importance of a topic in his or her current practice and his or her level of understanding of that topic at graduation. A larger FKD score represented greater deficiency, with a maximal possible FKD score of 9. A score of 0 would reflect an appropriate amount of knowledge to function effectively, and a negative score would reflect a knowledge surplus. Using the demographic information from the survey, we were then able to further analyze the levels of overall knowledge as well as the FKD for each topic with respect to length of time in practice, type of practice, and the surgeon’s involvement in PM.

We evaluated the reported levels of knowledge based on both type of practice (academic, hospital-employed, private practice) and who managed the practice (physician, nonphysician). Academic practices were defined as those associated with an academic medical center; hospital-employed practices were those in which the physician was an employee of a health system not associated with an academic medical center; and private practices were defined as physician-owned orthopedic practices not associated with an academic medical center. Regarding management, practices in which physicians were primarily responsible for the daily operations of the practice were considered physician-managed; conversely, practices in which operations were controlled by either employed or institutionally assigned administration were defined as nonphysician-managed.

Statistical analysis of the results for different practice types and levels of involvement in management was performed for both general knowledge and FKD. Means, medians, and standard deviations were calculated. One-way analysis of variance or t tests were then used to examine mean differences overall and within each business topic. When a difference was found, a post hoc Tukey multiple range test was performed to identify it. Differences at P < .05 were considered significant.

Results

One hundred eighty-two surgeons answered the survey, yielding a response rate of 55%. All had completed their training at our institution. Seven respondents were removed from the study because they had retired from practice (5) or had returned incomplete surveys (2).

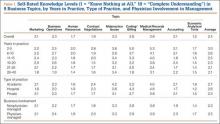

The overall self-rated level of business knowledge of all responding surgeons at the conclusion of their training was 2.4 on the 10-point scale (Table 1). Specifically, physicians reported the lowest levels of business understanding in economic analytical tools (1.5), human resources (1.7), and contract negotiations (1.9), suggesting minimal knowledge of these topics generally. They reported the highest levels of knowledge in medical records management (3.8) and malpractice issues (3.3). Even these topics, however, still reflected overall low levels of knowledge.

There was no statistically significant difference between private practice and academic physicians. In addition, surgeons in physician-managed practices reported significantly (P = .045) higher levels of understanding of economic analytical tools than surgeons in nonphysician-managed practices (Table 1). There were no other statistically significant differences among groups.

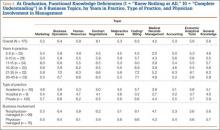

The overall calculated FKD for all surgeons was 5.6. FKDs were calculated for all 9 business topics. The worst FKDs were in business operations (6.4) and coding/billing (6.3). The topic with the least deficiency (lowest FKD) was in medical records management (4.2) (Table 2).

Surgeons’ FKDs based on practice type (academic, hospital-employed, private practice) were compared to identify potentially significant differences. Hospital-employed physicians had the lowest overall FKD (4.0), followed by physicians in academic practices (5.1) and private practices (5.9). Hospital-employed physicians reported statistically significantly better (lower) FKDs in comparison with physicians in private practice in multiple topics, including human resources, contract negotiations, malpractice issues, coding/billing, and accounting (Table 2). Similarly, physicians in academic practices also had statistically significantly better FKDs than physicians in private practice in the topics of business operations, contract negotiations, and billing/coding. Compared with hospital-employed physicians, physicians in academic practices had significantly more knowledge about marketing, business operations, and accounting. Physicians in private practice did not have significantly better FKDs in any topic in comparison with hospital-employed or academic physicians. There was no significant difference in FKDs for medical records management or economic analytical tools based on practice type.

Comparisons based on PM involvement showed that physicians in practices with nonphysician management had only a slightly better FKD (5.6) at graduation than those in practices with physician involvement (5.7). None of the 9 topics was statistically significant different based on physician involvement in PM.

Discussion

Building a successful medical practice has become more difficult for graduating orthopedic surgery residents because of an increasingly complex health care system, shrinking reimbursement rates, and looming regulatory changes. These challenges have reinforced the importance of teaching residents the necessary PM knowledge and skills to function effectively in a medical practice. Multiple studies from different specialties surveying or testing graduating residents and young practicing physicians on their business management knowledge or specific business topics have shown severe deficiencies.5-11 Unfortunately, graduating orthopedic surgery residents also appear inadequately prepared in PM. In a study of resident coding/billing knowledge, Gill and Schutt6 surveyed 2006 graduating orthopedic residents and found that only 13% felt confident in their coding ability. Our study results add to our understanding of multiple PM topics and demonstrate graduating orthopedic residents’ deficiencies throughout these topics.

Increased efforts to develop business management training programs and curricula have helped improve both overall PM and business knowledge in other specialties.12-15 ACGME now requires 100 hours of PM training among family medicine residency programs.16 A curriculum instituted in a general surgery residency focused on improving coding found that accuracy improved from 36% to 88% over 12 months.13 A family practice residency instituted a “simulated practice” model for its residents to improve practical PM learning and found statistically significant improvement over their prior didactic lectures.15 However, there continues to be significant variability in the topics and methods covered in business management curricula as programs struggle to determine how to most effectively use their limited time to prepare graduating residents.

In this study, we introduced the concept of FKD. With limited time available for teaching business knowledge and PM skills in residency, it has become imperative that training be efficient and effective. The FKD model can improve training efficiency by directing training to the topics that will produce the highest yield in preparing physicians for practice. As our results demonstrate, topics with the lowest levels of knowledge among surgeons often are not the same as the topics that are most needed to function effectively in practice (Table 3). The FKD model identifies deficiencies in practical, applicable knowledge rather than focusing on a general knowledge level. We suspect that focusing on topics with a high FKD would provide a higher yield in preparing physicians for practice. As such, our results suggest that training in business operations and coding/billing would likely provide the highest practical value, despite the fact that these were not the areas of least general knowledge.

Another finding of this study was the FKD difference based on type of practice. Compared with private practice physicians, hospital-employed or academic physicians had substantially lower overall FKDs and significantly lower FKDs in several specific topics. However, these FKD differences exist despite minimal differences in overall levels of knowledge. This would suggest that less business knowledge was needed by physicians to enter these types of practices compared with traditional private practice. We speculate that this may be one factor influencing the recent trend by graduating orthopedic residents to take hospital-employed positions, as these positions may appear less demanding in terms of learning the management aspects of the new practice.

Our results also showed slightly higher reported average business knowledge and lower FKD reported by those who had recently completed training (within 2-5 years) versus those in practice much longer. This is particularly interesting, as our institution has maintained the same lecture-based program for many years without significant changes. Although these differences may not be statistically significant, they may reflect an increased interest in and attention to learning PM skills while in training. However, we acknowledge this is only one of many possible explanations for these findings.

This study had several limitations. First, all respondents were graduates of a single institution. We were trying to limit the variability in business training, but this also limits the scope of the results. Second, self-ratings on surveys provide subjective measures of business knowledge and functional knowledge. Scores may vary based on individuals’ understanding of given topics, or they may inaccurately represent their level of understanding. This is especially true of respondents who graduated from residency, for example, 20 years earlier—their survey responses may reflect erroneous recollection of business training at time of graduation compared with respondents who graduated more recently. Conversely, more recent graduates may not have a fully formed or accurate picture of how much business knowledge is required to function in practice. Nevertheless, we found no significant differences in measured parameters based on graduation date, so we chose not to exclude older respondents, which also may have weakened our data pool. Further, FKDs are relative values used to compare subjective deficiencies rather than absolute scores of specific general knowledge. As such, subjectivity, including recollection of business training, is inherent in the model used in this study.

Conclusion

Graduating orthopedic surgeons currently appear inadequately prepared to effectively manage business issues in their practices, as evidenced by their low overall knowledge levels and high FKDs. The novel FKD model described in this study helps define FKD levels and identify topics that may provide the highest yield in improving effectiveness in practice. Residency curricula focused on improving business and PM knowledge, particularly in the topics with the highest FKDs (eg, business operations, coding/billing), may improve training efficiency in these areas. Further studies with larger numbers of physicians across multiple institutions are needed to confirm these findings and to validate the FKD concept.

1. Rose EA, Neale AV, Rathur WA. Teaching practice management during residency. Fam Med. 1999;31(2):107-113.

2. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Updated June 9, 2013. Accessed August 25, 2015.

3. Itani K. A positive approach to core competencies and benchmarks for graduate medical education. Am J Surg. 2002;184(3):196-203.

4. Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC Jr. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally trained in business and practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13.

5. McDonnell PJ, Kirwan TJ, Brinton GS, et al. Perceptions of recent ophthalmology residency graduates regarding preparation for practice. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):387-391.

6. Gill JB, Schutt RC Jr. Practice management education in orthopaedic surgical residencies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):216-219.

7. Satiani B. Business knowledge in surgeons. Am J Surg. 2004;188(1):13-16.

8. Cantor JC, Baker LC, Hughes RG. Preparedness for practice. Young physicians’ views of their professional education. JAMA. 1993;270(9):1035-1040.

9. Fakhry SM, Robinson L, Hendershot K, Reines HD. Surgical residents’ knowledge of documentation and coding for professional services: an opportunity for a focused educational offering. Am J Surg. 2007;194(2):263-267.

10. Williford LE, Ling FW, Summitt RL Jr, Stovall TG. Practice management in obstetrics and gynecology residency curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(3):476-479.

11. Andreae MC, Dunham K, Freed GL. Inadequate training in billing and coding as perceived by recent pediatric graduates. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48(9):939-944.

12. Kolva DE, Barzee KA, Morley CP. Practice management residency curricula: a systematic literature review. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):411-419.

13. Jones K, Lebron RA, Mangram A, Dunn E. Practice management education during surgical residency. Am J Surg. 2008;196(6):878-881.

14. Kerfoot BP, Conlin PR, Travison T, McMahon GT. Web-based education in systems-based practice: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):361-366.

15. LoPresti L, Ginn P, Treat R. Using a simulated practice to improve practice management learning. Fam Med. 2009;41(9):640-645.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Family medicine program requirements. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/132/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/MedicalSpecialties/FamilyMedicine.aspx. Accessed September 23, 2015.

With the increasing complexity of health care policy, significant changes in reimbursement and payer sources, and constant push to improve the cost-efficiency of care delivery, there has been a growing focus on the importance of business knowledge and practice management (PM) skills among physicians. Family medicine was the first specialty to require PM training during residency; other specialities have begun implementing business training into their residency curriculum.1 In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) identified 6 core competencies that should be included in resident training. One of these core competencies involves training in health care systems and PM.2,3

Residency program directors have also recognized the need for business training among residents. One study that surveyed general surgery program directors found that more than 87% agreed that residents should be trained in business and PM.4 Although these directors recognized the need for training, they also acknowledged the current deficiency: more than 70% thought their current trainees were inadequately trained in business and PM. Similarly, residents and physicians in multiple specialties have reported significant deficiencies in their training and knowledge of PM and business principles.5-11 For example, in a recent survey of ophthalmologists who had been in practice less than 5 years, 70% reported being not very well or not at all trained in overall PM skills during residency.5 Yet, most respondents thought training in this area was the responsibility of the training program.

The call for more business and PM training during residency has been tempered by increasing demands on medical and surgical skills training and time limitations such as duty-hour restrictions. These limitations reinforce the need to find efficient and effective means of teaching necessary business knowledge and PM skills. Paramount to doing this is recognizing the difference between general knowledge and functional knowledge—essentially, what is specifically needed to function effectively in practice.

We conducted a study not only to determine the general level of knowledge that physicians have in different business and PM topics when they complete their residency, but also to evaluate the level of knowledge that graduating physicians need in different business and PM topics in order to function effectively in a medical practice. Toward this end, we developed a novel model that could help determine the level of the functional knowledge deficiency (FKD) of particular business topics. We thought this model would allow us to quantify how much knowledge physicians needed to acquire in a given topic in order to function effectively in practice. We hypothesized that graduating residents would report overall low levels of business knowledge and high FKDs.

Materials and Methods

To minimize variability in the specific type and amount of business training received, we focused this study on a single institution that had maintained a uniform business management curriculum over an extended period. The business training program provided to residents in the orthopedic surgery residency at this institution included 6 hours of didactic lectures on various business topics annually. This program has been in place for more than 15 years and has not undergone any significant changes during that time.

Using the program’s alumni directory, we emailed a cover letter and an 11-question survey to all 332 residents and fellows who had completed their residency or fellowship training at our institution between 1970 and 2008. Anyone who did not reply to the email was mailed a copy of the cover letter and the survey.

The first 4 survey questions involved the demographics of the surgeon and the surgeon’s practice. Subsequent questions focused on the surgeon’s understanding of 9 different general business and PM topics and their importance in the practice. The topics were marketing, business operations, human resources, contract negotiations, malpractice issues, coding/billing, medical records management, accounting, and economic analytical tools. The surgeon was asked to use a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (“knew nothing at all”) to 10 (“complete understanding”) to rate his or her understanding of each topic at the completion of residency. The surgeon was also asked to rate how important it was to understand that topic in the surgeon’s current practice. Again, a 10-point scale was used: 1 (“not important at all”) to 10 (“absolutely vital”) (Figure).

When the surveys were returned, their data were compiled and analyzed to determine the overall knowledge levels for each topic and the levels based on years in practice, type of practice, and level of involvement in PM. We also wanted to determine the amount of business knowledge that they needed in order to function effectively in practice (and that they lacked at time of graduation). We defined this as the FKD at graduation and calculated it as the difference between the surgeon’s reported importance of a topic in his or her current practice and his or her level of understanding of that topic at graduation. A larger FKD score represented greater deficiency, with a maximal possible FKD score of 9. A score of 0 would reflect an appropriate amount of knowledge to function effectively, and a negative score would reflect a knowledge surplus. Using the demographic information from the survey, we were then able to further analyze the levels of overall knowledge as well as the FKD for each topic with respect to length of time in practice, type of practice, and the surgeon’s involvement in PM.

We evaluated the reported levels of knowledge based on both type of practice (academic, hospital-employed, private practice) and who managed the practice (physician, nonphysician). Academic practices were defined as those associated with an academic medical center; hospital-employed practices were those in which the physician was an employee of a health system not associated with an academic medical center; and private practices were defined as physician-owned orthopedic practices not associated with an academic medical center. Regarding management, practices in which physicians were primarily responsible for the daily operations of the practice were considered physician-managed; conversely, practices in which operations were controlled by either employed or institutionally assigned administration were defined as nonphysician-managed.

Statistical analysis of the results for different practice types and levels of involvement in management was performed for both general knowledge and FKD. Means, medians, and standard deviations were calculated. One-way analysis of variance or t tests were then used to examine mean differences overall and within each business topic. When a difference was found, a post hoc Tukey multiple range test was performed to identify it. Differences at P < .05 were considered significant.

Results

One hundred eighty-two surgeons answered the survey, yielding a response rate of 55%. All had completed their training at our institution. Seven respondents were removed from the study because they had retired from practice (5) or had returned incomplete surveys (2).

The overall self-rated level of business knowledge of all responding surgeons at the conclusion of their training was 2.4 on the 10-point scale (Table 1). Specifically, physicians reported the lowest levels of business understanding in economic analytical tools (1.5), human resources (1.7), and contract negotiations (1.9), suggesting minimal knowledge of these topics generally. They reported the highest levels of knowledge in medical records management (3.8) and malpractice issues (3.3). Even these topics, however, still reflected overall low levels of knowledge.

There was no statistically significant difference between private practice and academic physicians. In addition, surgeons in physician-managed practices reported significantly (P = .045) higher levels of understanding of economic analytical tools than surgeons in nonphysician-managed practices (Table 1). There were no other statistically significant differences among groups.

The overall calculated FKD for all surgeons was 5.6. FKDs were calculated for all 9 business topics. The worst FKDs were in business operations (6.4) and coding/billing (6.3). The topic with the least deficiency (lowest FKD) was in medical records management (4.2) (Table 2).

Surgeons’ FKDs based on practice type (academic, hospital-employed, private practice) were compared to identify potentially significant differences. Hospital-employed physicians had the lowest overall FKD (4.0), followed by physicians in academic practices (5.1) and private practices (5.9). Hospital-employed physicians reported statistically significantly better (lower) FKDs in comparison with physicians in private practice in multiple topics, including human resources, contract negotiations, malpractice issues, coding/billing, and accounting (Table 2). Similarly, physicians in academic practices also had statistically significantly better FKDs than physicians in private practice in the topics of business operations, contract negotiations, and billing/coding. Compared with hospital-employed physicians, physicians in academic practices had significantly more knowledge about marketing, business operations, and accounting. Physicians in private practice did not have significantly better FKDs in any topic in comparison with hospital-employed or academic physicians. There was no significant difference in FKDs for medical records management or economic analytical tools based on practice type.

Comparisons based on PM involvement showed that physicians in practices with nonphysician management had only a slightly better FKD (5.6) at graduation than those in practices with physician involvement (5.7). None of the 9 topics was statistically significant different based on physician involvement in PM.

Discussion

Building a successful medical practice has become more difficult for graduating orthopedic surgery residents because of an increasingly complex health care system, shrinking reimbursement rates, and looming regulatory changes. These challenges have reinforced the importance of teaching residents the necessary PM knowledge and skills to function effectively in a medical practice. Multiple studies from different specialties surveying or testing graduating residents and young practicing physicians on their business management knowledge or specific business topics have shown severe deficiencies.5-11 Unfortunately, graduating orthopedic surgery residents also appear inadequately prepared in PM. In a study of resident coding/billing knowledge, Gill and Schutt6 surveyed 2006 graduating orthopedic residents and found that only 13% felt confident in their coding ability. Our study results add to our understanding of multiple PM topics and demonstrate graduating orthopedic residents’ deficiencies throughout these topics.

Increased efforts to develop business management training programs and curricula have helped improve both overall PM and business knowledge in other specialties.12-15 ACGME now requires 100 hours of PM training among family medicine residency programs.16 A curriculum instituted in a general surgery residency focused on improving coding found that accuracy improved from 36% to 88% over 12 months.13 A family practice residency instituted a “simulated practice” model for its residents to improve practical PM learning and found statistically significant improvement over their prior didactic lectures.15 However, there continues to be significant variability in the topics and methods covered in business management curricula as programs struggle to determine how to most effectively use their limited time to prepare graduating residents.

In this study, we introduced the concept of FKD. With limited time available for teaching business knowledge and PM skills in residency, it has become imperative that training be efficient and effective. The FKD model can improve training efficiency by directing training to the topics that will produce the highest yield in preparing physicians for practice. As our results demonstrate, topics with the lowest levels of knowledge among surgeons often are not the same as the topics that are most needed to function effectively in practice (Table 3). The FKD model identifies deficiencies in practical, applicable knowledge rather than focusing on a general knowledge level. We suspect that focusing on topics with a high FKD would provide a higher yield in preparing physicians for practice. As such, our results suggest that training in business operations and coding/billing would likely provide the highest practical value, despite the fact that these were not the areas of least general knowledge.

Another finding of this study was the FKD difference based on type of practice. Compared with private practice physicians, hospital-employed or academic physicians had substantially lower overall FKDs and significantly lower FKDs in several specific topics. However, these FKD differences exist despite minimal differences in overall levels of knowledge. This would suggest that less business knowledge was needed by physicians to enter these types of practices compared with traditional private practice. We speculate that this may be one factor influencing the recent trend by graduating orthopedic residents to take hospital-employed positions, as these positions may appear less demanding in terms of learning the management aspects of the new practice.

Our results also showed slightly higher reported average business knowledge and lower FKD reported by those who had recently completed training (within 2-5 years) versus those in practice much longer. This is particularly interesting, as our institution has maintained the same lecture-based program for many years without significant changes. Although these differences may not be statistically significant, they may reflect an increased interest in and attention to learning PM skills while in training. However, we acknowledge this is only one of many possible explanations for these findings.

This study had several limitations. First, all respondents were graduates of a single institution. We were trying to limit the variability in business training, but this also limits the scope of the results. Second, self-ratings on surveys provide subjective measures of business knowledge and functional knowledge. Scores may vary based on individuals’ understanding of given topics, or they may inaccurately represent their level of understanding. This is especially true of respondents who graduated from residency, for example, 20 years earlier—their survey responses may reflect erroneous recollection of business training at time of graduation compared with respondents who graduated more recently. Conversely, more recent graduates may not have a fully formed or accurate picture of how much business knowledge is required to function in practice. Nevertheless, we found no significant differences in measured parameters based on graduation date, so we chose not to exclude older respondents, which also may have weakened our data pool. Further, FKDs are relative values used to compare subjective deficiencies rather than absolute scores of specific general knowledge. As such, subjectivity, including recollection of business training, is inherent in the model used in this study.

Conclusion

Graduating orthopedic surgeons currently appear inadequately prepared to effectively manage business issues in their practices, as evidenced by their low overall knowledge levels and high FKDs. The novel FKD model described in this study helps define FKD levels and identify topics that may provide the highest yield in improving effectiveness in practice. Residency curricula focused on improving business and PM knowledge, particularly in the topics with the highest FKDs (eg, business operations, coding/billing), may improve training efficiency in these areas. Further studies with larger numbers of physicians across multiple institutions are needed to confirm these findings and to validate the FKD concept.

With the increasing complexity of health care policy, significant changes in reimbursement and payer sources, and constant push to improve the cost-efficiency of care delivery, there has been a growing focus on the importance of business knowledge and practice management (PM) skills among physicians. Family medicine was the first specialty to require PM training during residency; other specialities have begun implementing business training into their residency curriculum.1 In 1999, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) identified 6 core competencies that should be included in resident training. One of these core competencies involves training in health care systems and PM.2,3

Residency program directors have also recognized the need for business training among residents. One study that surveyed general surgery program directors found that more than 87% agreed that residents should be trained in business and PM.4 Although these directors recognized the need for training, they also acknowledged the current deficiency: more than 70% thought their current trainees were inadequately trained in business and PM. Similarly, residents and physicians in multiple specialties have reported significant deficiencies in their training and knowledge of PM and business principles.5-11 For example, in a recent survey of ophthalmologists who had been in practice less than 5 years, 70% reported being not very well or not at all trained in overall PM skills during residency.5 Yet, most respondents thought training in this area was the responsibility of the training program.

The call for more business and PM training during residency has been tempered by increasing demands on medical and surgical skills training and time limitations such as duty-hour restrictions. These limitations reinforce the need to find efficient and effective means of teaching necessary business knowledge and PM skills. Paramount to doing this is recognizing the difference between general knowledge and functional knowledge—essentially, what is specifically needed to function effectively in practice.

We conducted a study not only to determine the general level of knowledge that physicians have in different business and PM topics when they complete their residency, but also to evaluate the level of knowledge that graduating physicians need in different business and PM topics in order to function effectively in a medical practice. Toward this end, we developed a novel model that could help determine the level of the functional knowledge deficiency (FKD) of particular business topics. We thought this model would allow us to quantify how much knowledge physicians needed to acquire in a given topic in order to function effectively in practice. We hypothesized that graduating residents would report overall low levels of business knowledge and high FKDs.

Materials and Methods

To minimize variability in the specific type and amount of business training received, we focused this study on a single institution that had maintained a uniform business management curriculum over an extended period. The business training program provided to residents in the orthopedic surgery residency at this institution included 6 hours of didactic lectures on various business topics annually. This program has been in place for more than 15 years and has not undergone any significant changes during that time.

Using the program’s alumni directory, we emailed a cover letter and an 11-question survey to all 332 residents and fellows who had completed their residency or fellowship training at our institution between 1970 and 2008. Anyone who did not reply to the email was mailed a copy of the cover letter and the survey.

The first 4 survey questions involved the demographics of the surgeon and the surgeon’s practice. Subsequent questions focused on the surgeon’s understanding of 9 different general business and PM topics and their importance in the practice. The topics were marketing, business operations, human resources, contract negotiations, malpractice issues, coding/billing, medical records management, accounting, and economic analytical tools. The surgeon was asked to use a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (“knew nothing at all”) to 10 (“complete understanding”) to rate his or her understanding of each topic at the completion of residency. The surgeon was also asked to rate how important it was to understand that topic in the surgeon’s current practice. Again, a 10-point scale was used: 1 (“not important at all”) to 10 (“absolutely vital”) (Figure).

When the surveys were returned, their data were compiled and analyzed to determine the overall knowledge levels for each topic and the levels based on years in practice, type of practice, and level of involvement in PM. We also wanted to determine the amount of business knowledge that they needed in order to function effectively in practice (and that they lacked at time of graduation). We defined this as the FKD at graduation and calculated it as the difference between the surgeon’s reported importance of a topic in his or her current practice and his or her level of understanding of that topic at graduation. A larger FKD score represented greater deficiency, with a maximal possible FKD score of 9. A score of 0 would reflect an appropriate amount of knowledge to function effectively, and a negative score would reflect a knowledge surplus. Using the demographic information from the survey, we were then able to further analyze the levels of overall knowledge as well as the FKD for each topic with respect to length of time in practice, type of practice, and the surgeon’s involvement in PM.

We evaluated the reported levels of knowledge based on both type of practice (academic, hospital-employed, private practice) and who managed the practice (physician, nonphysician). Academic practices were defined as those associated with an academic medical center; hospital-employed practices were those in which the physician was an employee of a health system not associated with an academic medical center; and private practices were defined as physician-owned orthopedic practices not associated with an academic medical center. Regarding management, practices in which physicians were primarily responsible for the daily operations of the practice were considered physician-managed; conversely, practices in which operations were controlled by either employed or institutionally assigned administration were defined as nonphysician-managed.

Statistical analysis of the results for different practice types and levels of involvement in management was performed for both general knowledge and FKD. Means, medians, and standard deviations were calculated. One-way analysis of variance or t tests were then used to examine mean differences overall and within each business topic. When a difference was found, a post hoc Tukey multiple range test was performed to identify it. Differences at P < .05 were considered significant.

Results

One hundred eighty-two surgeons answered the survey, yielding a response rate of 55%. All had completed their training at our institution. Seven respondents were removed from the study because they had retired from practice (5) or had returned incomplete surveys (2).

The overall self-rated level of business knowledge of all responding surgeons at the conclusion of their training was 2.4 on the 10-point scale (Table 1). Specifically, physicians reported the lowest levels of business understanding in economic analytical tools (1.5), human resources (1.7), and contract negotiations (1.9), suggesting minimal knowledge of these topics generally. They reported the highest levels of knowledge in medical records management (3.8) and malpractice issues (3.3). Even these topics, however, still reflected overall low levels of knowledge.

There was no statistically significant difference between private practice and academic physicians. In addition, surgeons in physician-managed practices reported significantly (P = .045) higher levels of understanding of economic analytical tools than surgeons in nonphysician-managed practices (Table 1). There were no other statistically significant differences among groups.

The overall calculated FKD for all surgeons was 5.6. FKDs were calculated for all 9 business topics. The worst FKDs were in business operations (6.4) and coding/billing (6.3). The topic with the least deficiency (lowest FKD) was in medical records management (4.2) (Table 2).

Surgeons’ FKDs based on practice type (academic, hospital-employed, private practice) were compared to identify potentially significant differences. Hospital-employed physicians had the lowest overall FKD (4.0), followed by physicians in academic practices (5.1) and private practices (5.9). Hospital-employed physicians reported statistically significantly better (lower) FKDs in comparison with physicians in private practice in multiple topics, including human resources, contract negotiations, malpractice issues, coding/billing, and accounting (Table 2). Similarly, physicians in academic practices also had statistically significantly better FKDs than physicians in private practice in the topics of business operations, contract negotiations, and billing/coding. Compared with hospital-employed physicians, physicians in academic practices had significantly more knowledge about marketing, business operations, and accounting. Physicians in private practice did not have significantly better FKDs in any topic in comparison with hospital-employed or academic physicians. There was no significant difference in FKDs for medical records management or economic analytical tools based on practice type.

Comparisons based on PM involvement showed that physicians in practices with nonphysician management had only a slightly better FKD (5.6) at graduation than those in practices with physician involvement (5.7). None of the 9 topics was statistically significant different based on physician involvement in PM.

Discussion

Building a successful medical practice has become more difficult for graduating orthopedic surgery residents because of an increasingly complex health care system, shrinking reimbursement rates, and looming regulatory changes. These challenges have reinforced the importance of teaching residents the necessary PM knowledge and skills to function effectively in a medical practice. Multiple studies from different specialties surveying or testing graduating residents and young practicing physicians on their business management knowledge or specific business topics have shown severe deficiencies.5-11 Unfortunately, graduating orthopedic surgery residents also appear inadequately prepared in PM. In a study of resident coding/billing knowledge, Gill and Schutt6 surveyed 2006 graduating orthopedic residents and found that only 13% felt confident in their coding ability. Our study results add to our understanding of multiple PM topics and demonstrate graduating orthopedic residents’ deficiencies throughout these topics.

Increased efforts to develop business management training programs and curricula have helped improve both overall PM and business knowledge in other specialties.12-15 ACGME now requires 100 hours of PM training among family medicine residency programs.16 A curriculum instituted in a general surgery residency focused on improving coding found that accuracy improved from 36% to 88% over 12 months.13 A family practice residency instituted a “simulated practice” model for its residents to improve practical PM learning and found statistically significant improvement over their prior didactic lectures.15 However, there continues to be significant variability in the topics and methods covered in business management curricula as programs struggle to determine how to most effectively use their limited time to prepare graduating residents.

In this study, we introduced the concept of FKD. With limited time available for teaching business knowledge and PM skills in residency, it has become imperative that training be efficient and effective. The FKD model can improve training efficiency by directing training to the topics that will produce the highest yield in preparing physicians for practice. As our results demonstrate, topics with the lowest levels of knowledge among surgeons often are not the same as the topics that are most needed to function effectively in practice (Table 3). The FKD model identifies deficiencies in practical, applicable knowledge rather than focusing on a general knowledge level. We suspect that focusing on topics with a high FKD would provide a higher yield in preparing physicians for practice. As such, our results suggest that training in business operations and coding/billing would likely provide the highest practical value, despite the fact that these were not the areas of least general knowledge.

Another finding of this study was the FKD difference based on type of practice. Compared with private practice physicians, hospital-employed or academic physicians had substantially lower overall FKDs and significantly lower FKDs in several specific topics. However, these FKD differences exist despite minimal differences in overall levels of knowledge. This would suggest that less business knowledge was needed by physicians to enter these types of practices compared with traditional private practice. We speculate that this may be one factor influencing the recent trend by graduating orthopedic residents to take hospital-employed positions, as these positions may appear less demanding in terms of learning the management aspects of the new practice.

Our results also showed slightly higher reported average business knowledge and lower FKD reported by those who had recently completed training (within 2-5 years) versus those in practice much longer. This is particularly interesting, as our institution has maintained the same lecture-based program for many years without significant changes. Although these differences may not be statistically significant, they may reflect an increased interest in and attention to learning PM skills while in training. However, we acknowledge this is only one of many possible explanations for these findings.

This study had several limitations. First, all respondents were graduates of a single institution. We were trying to limit the variability in business training, but this also limits the scope of the results. Second, self-ratings on surveys provide subjective measures of business knowledge and functional knowledge. Scores may vary based on individuals’ understanding of given topics, or they may inaccurately represent their level of understanding. This is especially true of respondents who graduated from residency, for example, 20 years earlier—their survey responses may reflect erroneous recollection of business training at time of graduation compared with respondents who graduated more recently. Conversely, more recent graduates may not have a fully formed or accurate picture of how much business knowledge is required to function in practice. Nevertheless, we found no significant differences in measured parameters based on graduation date, so we chose not to exclude older respondents, which also may have weakened our data pool. Further, FKDs are relative values used to compare subjective deficiencies rather than absolute scores of specific general knowledge. As such, subjectivity, including recollection of business training, is inherent in the model used in this study.

Conclusion

Graduating orthopedic surgeons currently appear inadequately prepared to effectively manage business issues in their practices, as evidenced by their low overall knowledge levels and high FKDs. The novel FKD model described in this study helps define FKD levels and identify topics that may provide the highest yield in improving effectiveness in practice. Residency curricula focused on improving business and PM knowledge, particularly in the topics with the highest FKDs (eg, business operations, coding/billing), may improve training efficiency in these areas. Further studies with larger numbers of physicians across multiple institutions are needed to confirm these findings and to validate the FKD concept.

1. Rose EA, Neale AV, Rathur WA. Teaching practice management during residency. Fam Med. 1999;31(2):107-113.

2. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Updated June 9, 2013. Accessed August 25, 2015.

3. Itani K. A positive approach to core competencies and benchmarks for graduate medical education. Am J Surg. 2002;184(3):196-203.

4. Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC Jr. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally trained in business and practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13.

5. McDonnell PJ, Kirwan TJ, Brinton GS, et al. Perceptions of recent ophthalmology residency graduates regarding preparation for practice. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):387-391.

6. Gill JB, Schutt RC Jr. Practice management education in orthopaedic surgical residencies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):216-219.

7. Satiani B. Business knowledge in surgeons. Am J Surg. 2004;188(1):13-16.

8. Cantor JC, Baker LC, Hughes RG. Preparedness for practice. Young physicians’ views of their professional education. JAMA. 1993;270(9):1035-1040.

9. Fakhry SM, Robinson L, Hendershot K, Reines HD. Surgical residents’ knowledge of documentation and coding for professional services: an opportunity for a focused educational offering. Am J Surg. 2007;194(2):263-267.

10. Williford LE, Ling FW, Summitt RL Jr, Stovall TG. Practice management in obstetrics and gynecology residency curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(3):476-479.

11. Andreae MC, Dunham K, Freed GL. Inadequate training in billing and coding as perceived by recent pediatric graduates. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48(9):939-944.

12. Kolva DE, Barzee KA, Morley CP. Practice management residency curricula: a systematic literature review. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):411-419.

13. Jones K, Lebron RA, Mangram A, Dunn E. Practice management education during surgical residency. Am J Surg. 2008;196(6):878-881.

14. Kerfoot BP, Conlin PR, Travison T, McMahon GT. Web-based education in systems-based practice: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):361-366.

15. LoPresti L, Ginn P, Treat R. Using a simulated practice to improve practice management learning. Fam Med. 2009;41(9):640-645.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Family medicine program requirements. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/132/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/MedicalSpecialties/FamilyMedicine.aspx. Accessed September 23, 2015.

1. Rose EA, Neale AV, Rathur WA. Teaching practice management during residency. Fam Med. 1999;31(2):107-113.

2. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Updated June 9, 2013. Accessed August 25, 2015.

3. Itani K. A positive approach to core competencies and benchmarks for graduate medical education. Am J Surg. 2002;184(3):196-203.

4. Lusco VC, Martinez SA, Polk HC Jr. Program directors in surgery agree that residents should be formally trained in business and practice management. Am J Surg. 2005;189(1):11-13.

5. McDonnell PJ, Kirwan TJ, Brinton GS, et al. Perceptions of recent ophthalmology residency graduates regarding preparation for practice. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):387-391.

6. Gill JB, Schutt RC Jr. Practice management education in orthopaedic surgical residencies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):216-219.

7. Satiani B. Business knowledge in surgeons. Am J Surg. 2004;188(1):13-16.

8. Cantor JC, Baker LC, Hughes RG. Preparedness for practice. Young physicians’ views of their professional education. JAMA. 1993;270(9):1035-1040.

9. Fakhry SM, Robinson L, Hendershot K, Reines HD. Surgical residents’ knowledge of documentation and coding for professional services: an opportunity for a focused educational offering. Am J Surg. 2007;194(2):263-267.

10. Williford LE, Ling FW, Summitt RL Jr, Stovall TG. Practice management in obstetrics and gynecology residency curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(3):476-479.

11. Andreae MC, Dunham K, Freed GL. Inadequate training in billing and coding as perceived by recent pediatric graduates. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48(9):939-944.

12. Kolva DE, Barzee KA, Morley CP. Practice management residency curricula: a systematic literature review. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):411-419.

13. Jones K, Lebron RA, Mangram A, Dunn E. Practice management education during surgical residency. Am J Surg. 2008;196(6):878-881.

14. Kerfoot BP, Conlin PR, Travison T, McMahon GT. Web-based education in systems-based practice: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(4):361-366.

15. LoPresti L, Ginn P, Treat R. Using a simulated practice to improve practice management learning. Fam Med. 2009;41(9):640-645.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Family medicine program requirements. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/132/ProgramandInstitutionalAccreditation/MedicalSpecialties/FamilyMedicine.aspx. Accessed September 23, 2015.