User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

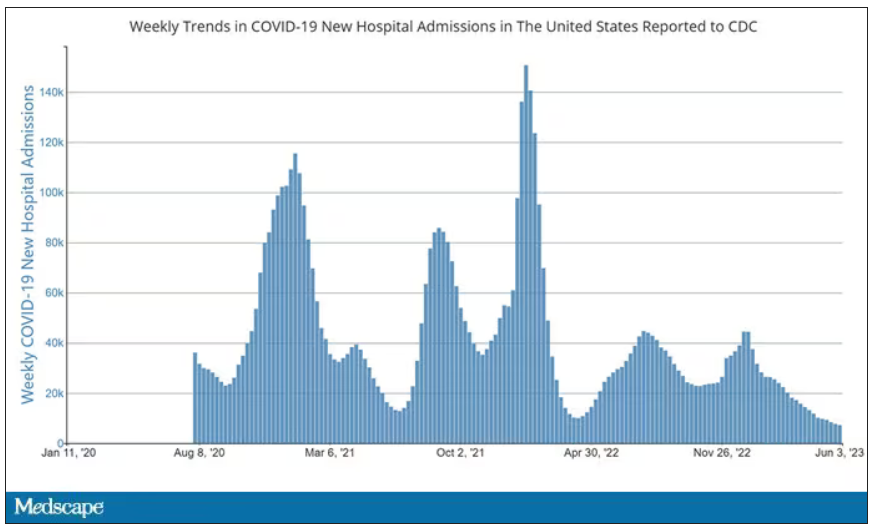

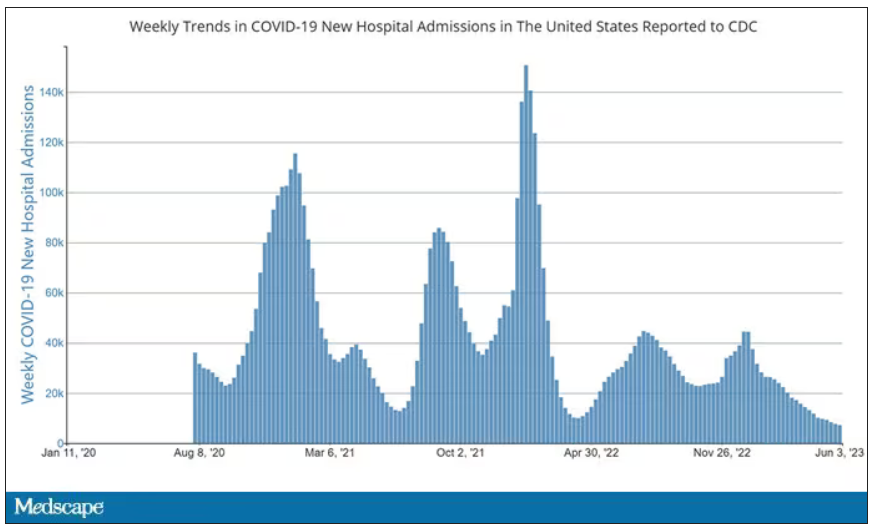

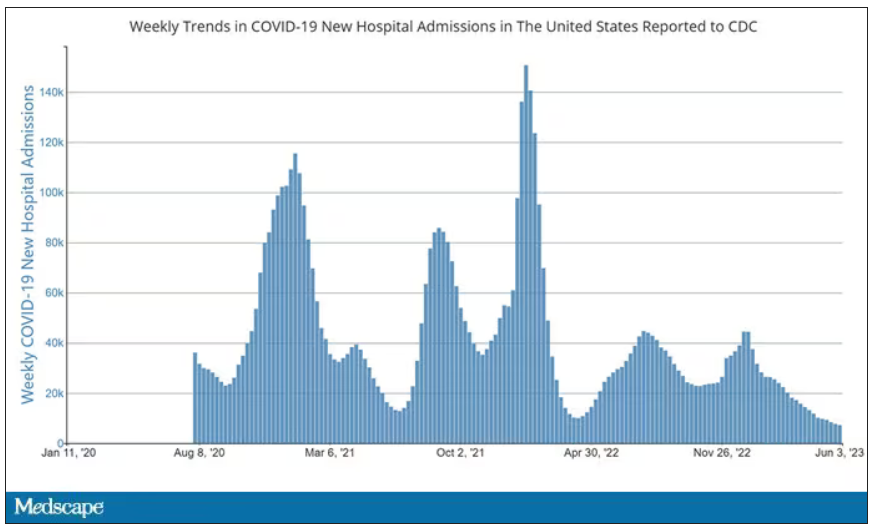

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

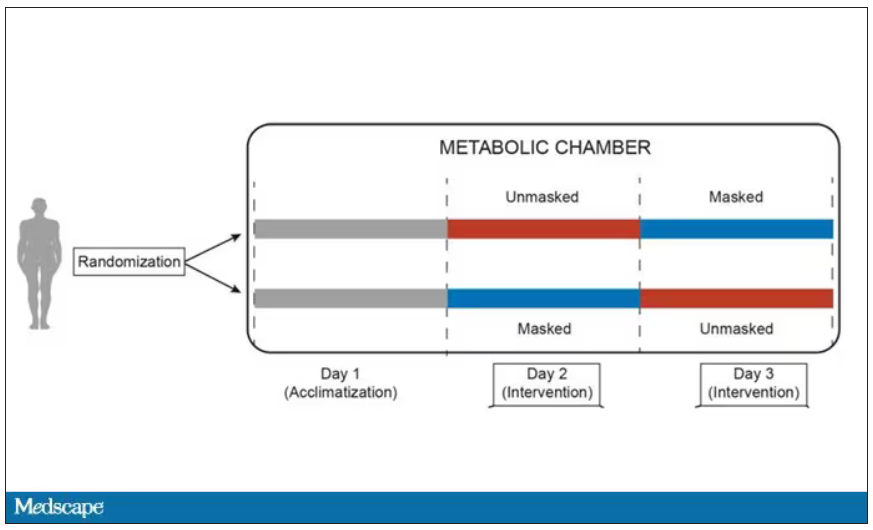

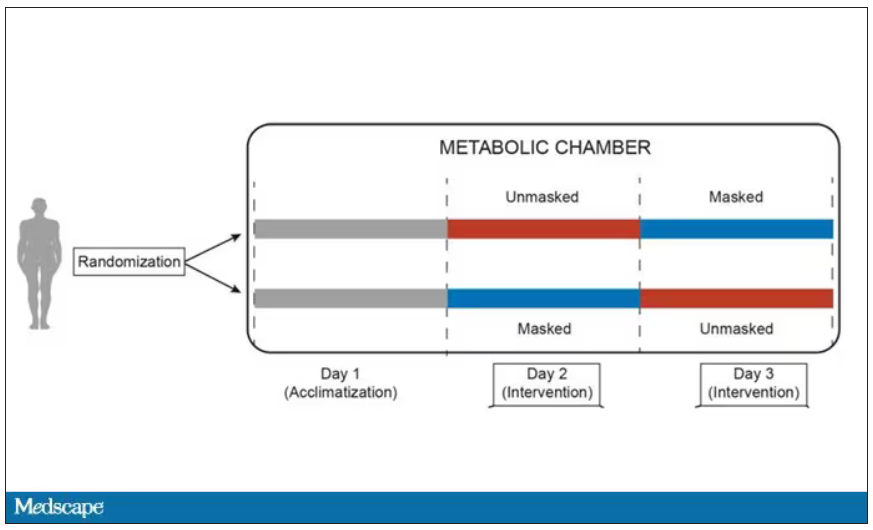

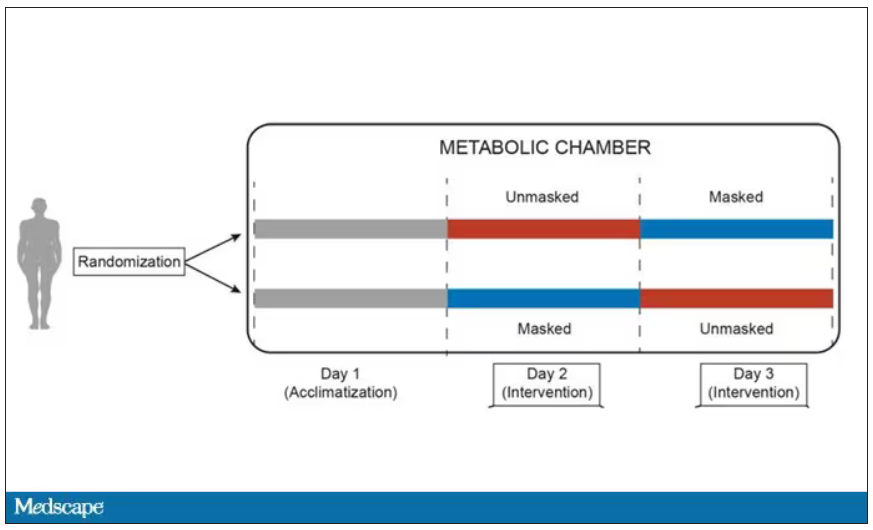

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

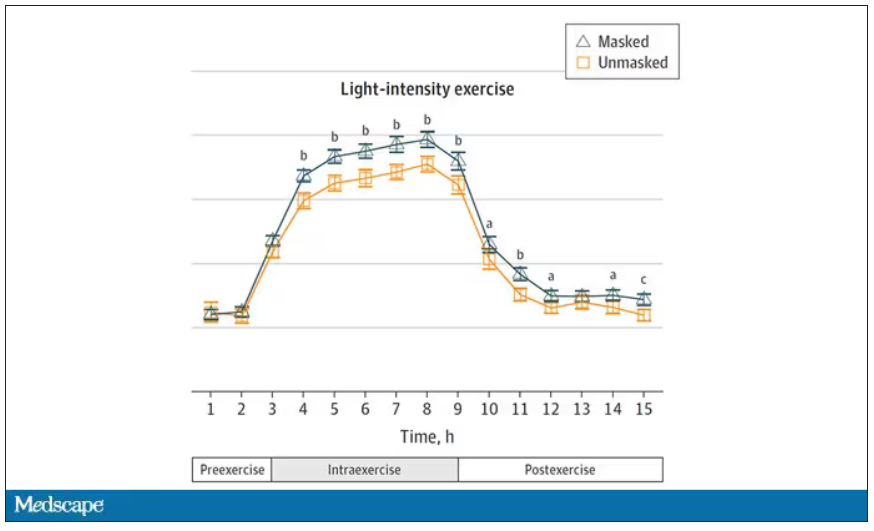

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

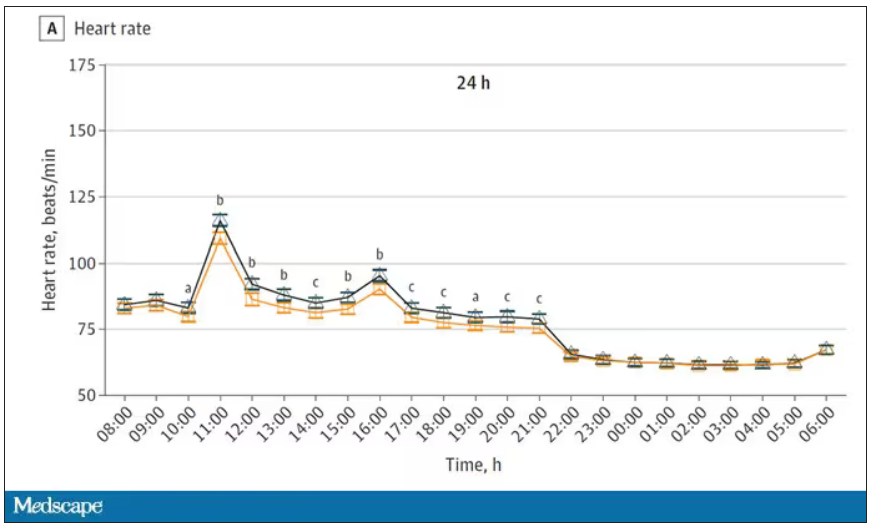

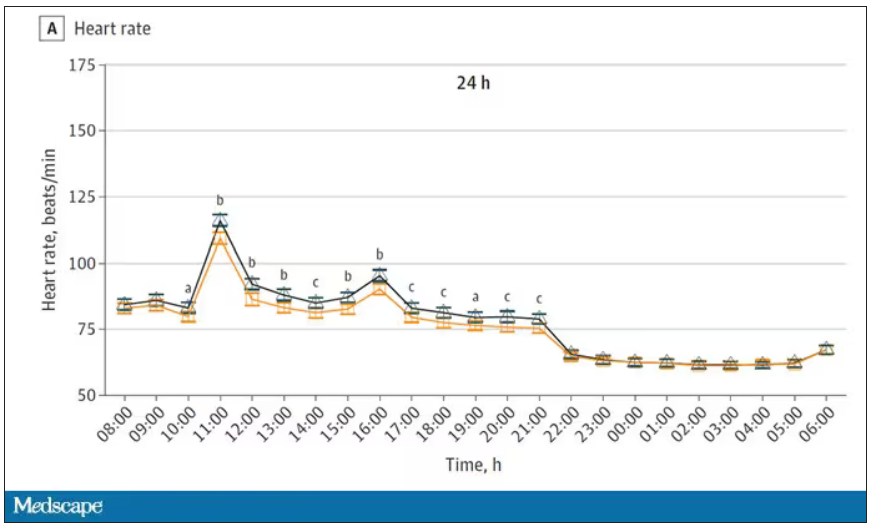

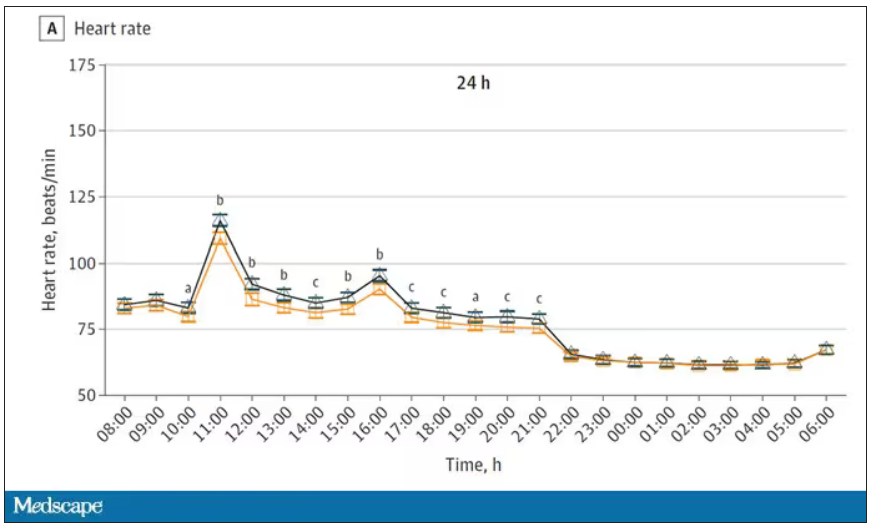

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

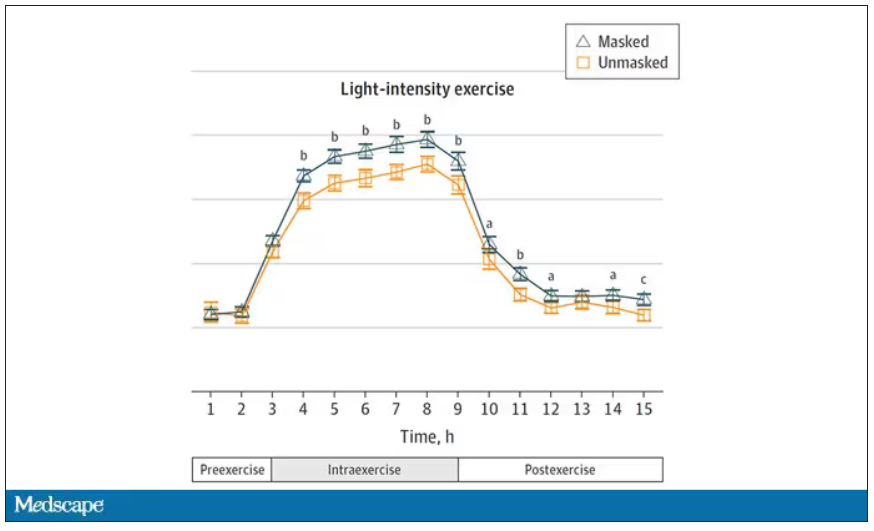

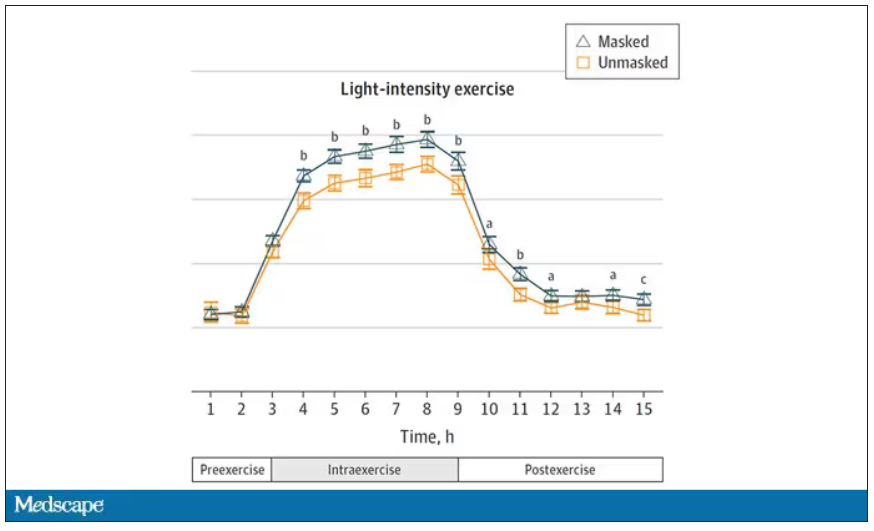

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.