User login

or dependence, compared with their White or rural/suburban counterparts, according to a study of 3.2 million Medicaid-enrolled children in North Carolina.

Analysis of the almost 138,000 prescription fills also showed that Black and urban children in North Carolina were less likely to fill a opioid prescription, suggesting a need “for future studies to explore racial and geographic opioid-related inequities in children,” Kelby W. Brown, MA, and associates at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said Oct. 5 in Health Affairs.

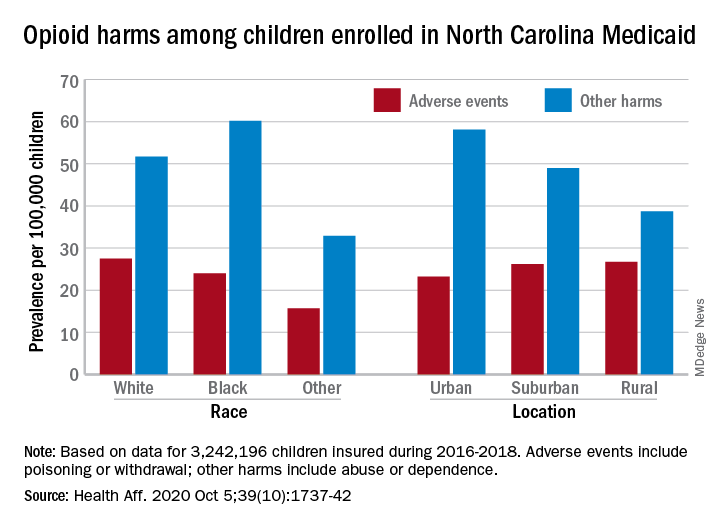

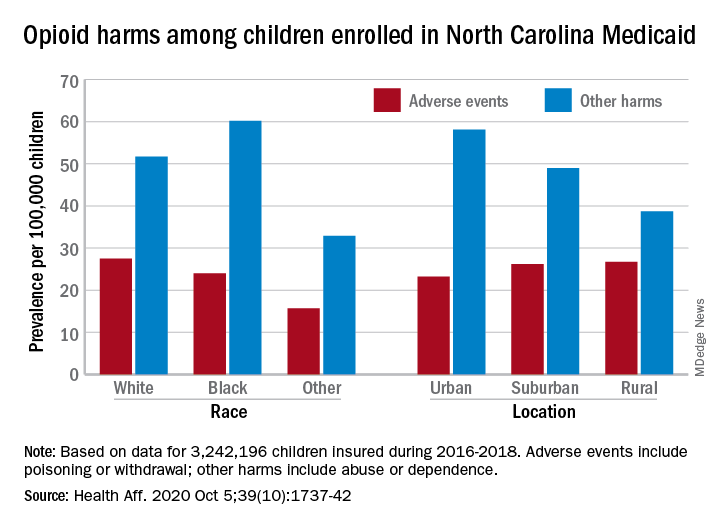

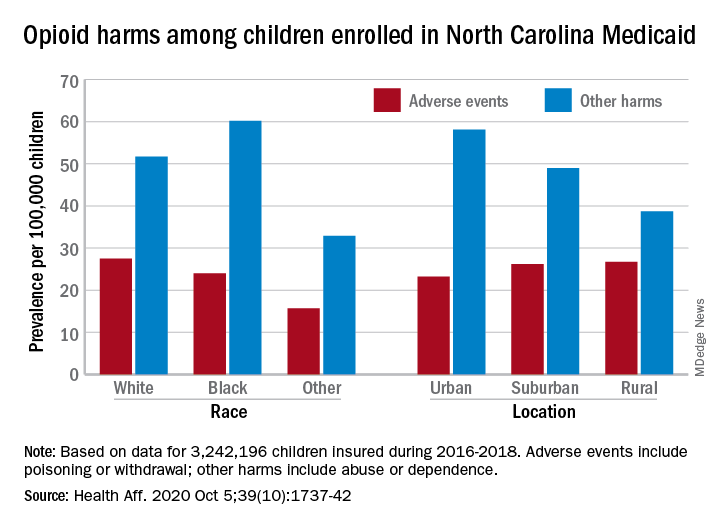

In 2016-2018, the prevalence of opioid-related adverse events, such as poisoning or withdrawal, was 24.0 per 100,000 children among Blacks aged 1-17 years, compared with 27.5 per 100,000 for whites. For other opioid-related harms such as abuse or dependence, the order was reversed: 60.2 for Blacks and 51.7 for Whites, the investigators reported. Children of all other races were lowest in both measures.

Geography also appears to play a part. The children in urban areas had the lowest rate of adverse events – 23.2 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 (suburban) and 26.7 (rural) – and the highest rate of other opioid-related harms – 58.1 vs. 49.0 (suburban) and 38.7 (rural), the Medicaid claims data showed.

Analysis of prescription fills revealed that black children aged 1-17 years had a significantly lower rate (2.7%) than Whites (3.1%) or those of other races (3.0%) and that urban children were significantly less likely to fill a prescription (2.7%) for opioids than the other two groups (suburban, 3.1%; rural, 3.4%), Mr. Brown and associates said.

The prescription data also showed that 48.4% of children aged 6-17 years who had an adverse event had filled a prescription for an opioid in the previous 6 months, compared with just 9.4% of those with other opioid-related harms. The median length of time since the last fill? Three days for children with an adverse event and 67 days for those with other harms, they said.

And those prescriptions, it turns out, were not coming just from the physicians of North Carolina. Physicians, with 35.5% of the prescription load, were the main source, but 33.3% of opioid fills in 2016-2018 came from dentists, and another 17.7% were written by advanced practice providers. Among physicians, the leading opioid-prescribing specialists were surgeons, with 17.3% of the total, the investigators reported.

“The distinct and separate groups of clinicians who prescribe opioids to children suggest the need for pediatric opioid prescribing guidelines, particularly for postprocedural pain,” Mr. Brown and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Brown KW et al. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1737-42.

or dependence, compared with their White or rural/suburban counterparts, according to a study of 3.2 million Medicaid-enrolled children in North Carolina.

Analysis of the almost 138,000 prescription fills also showed that Black and urban children in North Carolina were less likely to fill a opioid prescription, suggesting a need “for future studies to explore racial and geographic opioid-related inequities in children,” Kelby W. Brown, MA, and associates at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said Oct. 5 in Health Affairs.

In 2016-2018, the prevalence of opioid-related adverse events, such as poisoning or withdrawal, was 24.0 per 100,000 children among Blacks aged 1-17 years, compared with 27.5 per 100,000 for whites. For other opioid-related harms such as abuse or dependence, the order was reversed: 60.2 for Blacks and 51.7 for Whites, the investigators reported. Children of all other races were lowest in both measures.

Geography also appears to play a part. The children in urban areas had the lowest rate of adverse events – 23.2 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 (suburban) and 26.7 (rural) – and the highest rate of other opioid-related harms – 58.1 vs. 49.0 (suburban) and 38.7 (rural), the Medicaid claims data showed.

Analysis of prescription fills revealed that black children aged 1-17 years had a significantly lower rate (2.7%) than Whites (3.1%) or those of other races (3.0%) and that urban children were significantly less likely to fill a prescription (2.7%) for opioids than the other two groups (suburban, 3.1%; rural, 3.4%), Mr. Brown and associates said.

The prescription data also showed that 48.4% of children aged 6-17 years who had an adverse event had filled a prescription for an opioid in the previous 6 months, compared with just 9.4% of those with other opioid-related harms. The median length of time since the last fill? Three days for children with an adverse event and 67 days for those with other harms, they said.

And those prescriptions, it turns out, were not coming just from the physicians of North Carolina. Physicians, with 35.5% of the prescription load, were the main source, but 33.3% of opioid fills in 2016-2018 came from dentists, and another 17.7% were written by advanced practice providers. Among physicians, the leading opioid-prescribing specialists were surgeons, with 17.3% of the total, the investigators reported.

“The distinct and separate groups of clinicians who prescribe opioids to children suggest the need for pediatric opioid prescribing guidelines, particularly for postprocedural pain,” Mr. Brown and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Brown KW et al. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1737-42.

or dependence, compared with their White or rural/suburban counterparts, according to a study of 3.2 million Medicaid-enrolled children in North Carolina.

Analysis of the almost 138,000 prescription fills also showed that Black and urban children in North Carolina were less likely to fill a opioid prescription, suggesting a need “for future studies to explore racial and geographic opioid-related inequities in children,” Kelby W. Brown, MA, and associates at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said Oct. 5 in Health Affairs.

In 2016-2018, the prevalence of opioid-related adverse events, such as poisoning or withdrawal, was 24.0 per 100,000 children among Blacks aged 1-17 years, compared with 27.5 per 100,000 for whites. For other opioid-related harms such as abuse or dependence, the order was reversed: 60.2 for Blacks and 51.7 for Whites, the investigators reported. Children of all other races were lowest in both measures.

Geography also appears to play a part. The children in urban areas had the lowest rate of adverse events – 23.2 per 100,000 vs. 26.2 (suburban) and 26.7 (rural) – and the highest rate of other opioid-related harms – 58.1 vs. 49.0 (suburban) and 38.7 (rural), the Medicaid claims data showed.

Analysis of prescription fills revealed that black children aged 1-17 years had a significantly lower rate (2.7%) than Whites (3.1%) or those of other races (3.0%) and that urban children were significantly less likely to fill a prescription (2.7%) for opioids than the other two groups (suburban, 3.1%; rural, 3.4%), Mr. Brown and associates said.

The prescription data also showed that 48.4% of children aged 6-17 years who had an adverse event had filled a prescription for an opioid in the previous 6 months, compared with just 9.4% of those with other opioid-related harms. The median length of time since the last fill? Three days for children with an adverse event and 67 days for those with other harms, they said.

And those prescriptions, it turns out, were not coming just from the physicians of North Carolina. Physicians, with 35.5% of the prescription load, were the main source, but 33.3% of opioid fills in 2016-2018 came from dentists, and another 17.7% were written by advanced practice providers. Among physicians, the leading opioid-prescribing specialists were surgeons, with 17.3% of the total, the investigators reported.

“The distinct and separate groups of clinicians who prescribe opioids to children suggest the need for pediatric opioid prescribing guidelines, particularly for postprocedural pain,” Mr. Brown and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Brown KW et al. Health Aff. 2020;39(10):1737-42.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS